Mark Fuller Dillon's Blog, page 33

March 22, 2016

Frost in the Moonlight

Yes, that present participle in sentence 4 is grammatically awkward; an infinitive or the simple past would have made more sense. But I like the visual details, the movement, the simile about autumn grasses, the simplicity.

-- Sarah Orne Jewett, "Lady Ferry." From Old Friends and New, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 1907.

She was bent, but very tall and slender, and was walking slowly with a cane. Her head was covered with a great hood or wrapping of some kind, which she pushed back when she saw me. Some faint whitish figures on her dress looked like frost in the moonlight; and the dress itself was made of some strange stiff silk, which rustled softly like dry rushes and grasses in the autumn, -- a rustling noise that carries a chill with it. She came close to me, a sorrowful little figure very dreary at heart, standing still as the flowers themselves; and for several minutes she did not speak, but watched me, until I began to be afraid of her. Then she held out her hand, which trembled as if it were trying to shake off its rings.

-- Sarah Orne Jewett, "Lady Ferry." From Old Friends and New, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 1907.

Published on March 22, 2016 17:53

March 15, 2016

Martian Ambiguity

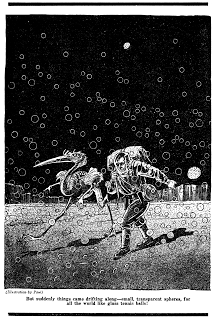

Writers have ways to link the patterns of a story to make it cohesive, but they can also break the patterns and end up with a story that seems fragmented or ill-considered. In "A Martian Odyssey," Stanley G. Weinbaum does both.

Writers have ways to link the patterns of a story to make it cohesive, but they can also break the patterns and end up with a story that seems fragmented or ill-considered. In "A Martian Odyssey," Stanley G. Weinbaum does both.Because I had loved "A Martian Odyssey" when I was nine years old, I hesitated for decades to try it again -- so many things from childhood can disappoint us, and American magazine stories from 1934 can disappoint us absolutely. But my reading it a few days ago showed me a story with many strengths to compensate for a few weaknesses.

For one thing, the style is chatty and excitable in ways that might seem dated. The crew of the first Earth ship on Mars have brought a full cargo of exclamation points -- and these people use them! They lob words at each other as Martians hurl darts! They mock each other with friendly gibes! They roar, exult, snap, shrill, ejaculate, growl, shout! And as I read, I wanted them to stop.

On the other hand, there is energy in the prose, and the story moves rapidly. Compared to many American pulp science fiction tales from the 1930s, "A Martian Odyssey" is light on its feet.

And although its noisy space-crew might hover on the verge of becoming national stereotypes, their separate languages, and their frequent inability to understand each other, represent one of the patterns that makes the story fit together: communication is hard enough between people, but harder still between people and Martians.

Weinbaum uses the ambiguity of language to make his Martians vivid. Nothing on Mars can be defined in human terms with precision. Biopods look like plants but move like animals. The silicon creature is mindless, but can build structures with Egyptian skill. The dream beast is whatever its prey wants it to be. The barrel beings are a technological species, but seem limited in both intellect and behaviour.

Tweel himself, the most human-like Martian encountered, is nothing but ambiguous. He looks like a bird, but only at first glance. He seems adapted to local conditions like a native, but one sequence implies that he, or his ancestors, might have landed on Mars from beyond the solar system. Even the name by which he calls himself seems to vary from one context to another.

Yet of all the characters in the story, Tweel seems most at ease with language, and the most adept at its use. The narrator, Jarvis, fails to pick up a single word of Tweel's vocabulary, but Tweel can use a few English words to convey complex ideas. And so, he can describe the silicon creature ("No one-one-two. No two-two-four."), the dream beast ("You one-one-two, he one-one-two."), and the barrel people ("One-one-two -- yes! Two-two-four -- no!"), in ways that Jarvis can grasp, and that leave him convinced of Tweel's more-than-human intelligence.

Weinbaum links these patterns of communication and ambiguous definition throughout "A Martian Odyssey," and in doing so, implies a stronger sense of story cohesion and subtext than most SF writers of the 1930s could manage. This makes me regret all the more the story's ending, which seems like an O. Henry twist grafted onto a narrative that does not need it. The ending adds nothing to the story's ideas or themes, and seems out of character for Jarvis, who, despite his constant yelling and gibing, is too thoughtful a person to do anything so stupid.

Endings matter, because they allow writers to give the patterns of a story a final coherence. Weinbaum seems to have understood this need for cohesion; I wish he had applied this understanding at the story's end. But narrative strengths also matter, and "A Martian Odyssey" has more than enough to keep its reputation high.

Illustration by Frank R. Paul, from Wonder Stories, July 1934.

Published on March 15, 2016 10:24

March 13, 2016

Their Thoughts Have Burned Themselves into the Cold Rocks

The challenge in using alliteration and assonance is to make them seem deliberate stylistic choices, and not lapses in revision:

-- Sarah Orne Jewett, "The Gray Man."

From, A White Heron, And Other Stories.

Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 1914.

There is everywhere a token of remembrance, of silence and secrecy. Some stronger nature once ruled these neglected trees and this fallow ground. They will wait the return of their master as long as roots can creep through mould, and the mould make way for them. The stories of strange lives have been whispered to the earth, their thoughts have burned themselves into the cold rocks. As one looks from the lower country toward the long slope of the great hillside, this old abiding-place marks the dark covering of trees like a scar. There is nothing to hide either the sunrise or the sunset. The low lands reach out of sight into the west and the sea fills all the east.

-- Sarah Orne Jewett, "The Gray Man."

From, A White Heron, And Other Stories.

Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 1914.

Published on March 13, 2016 12:44

March 3, 2016

At First, You Hear The Silence

It seems that my recent story has won the "Book of the Month" poll at the

Long And Short Reviews

website.

Published on March 03, 2016 08:54

February 20, 2016

Unearthly Beauty

Brian Aldiss:

-- From

Billion Year Spree, by Brian Aldiss. Corgi Books, 1975.

In Carl Jung's Memories, Dreams, Reflections, he recounts the vivid psychosis of one of his female patients, who believed that she had lived on the Moon. She told Jung a tale about her life there. It appears that the Moon people were threatened with extinction. A vampire lived in the high mountains of the Moon. The vampire kidnapped and killed women and children, who in consequence had taken to living underground. The patient resolved to kill the vampire but, when she and it came face to face, the vampire revealed himself as a man of unearthly beauty.

Jung makes a comment which could stand on the title page of this book: 'Thereafter I regarded the sufferings of the mentally ill in a different light. For I had gained insight into the richness and importance of their inner experience.'

-- From

Billion Year Spree, by Brian Aldiss. Corgi Books, 1975.

Published on February 20, 2016 08:48

February 18, 2016

With Talaquin or Mandragora

Avram Davidson:

From The Phoenix and the Mirror , 1969.

Cyprus was another world.

The city of Paphos might have been designed and built by a Grecian architect dreamy with the drugs called talaquin or mandragora: in marble yellow as unmixed cream, marble pink as sweetmeats, marble the green of pistuquim nuts, veined marble and grained marble, honey-colored and rose-red, the buildings climbed along the hills and frothed among the hollows. Tier after tier of overtall pillars, capitals of a profusion of carvings to make Corinthian seem ascetic, pediments lush with bas-reliefs, four-fold arches at every corner and crossing, statues so huge that they loomed over the housetops, statues so small that whole troops of them flocked and frolicked under every building’s eaves, groves and gardens everywhere, fountains playing, water spouting....

Paphos.

From The Phoenix and the Mirror , 1969.

Published on February 18, 2016 00:06

February 14, 2016

The Longer Task

When a story fails to gain readers, I find it easy to blame the one person responsible for its weakness. What I forget, and what I must remember, is that the same person is responsible for the story's existence. Take away the person, and you take away not only the story, but the pleasure that awaits any reader who might discover it.

I have to keep this in mind, because the task of gaining readers can take as long, or even longer, than the task of learning to write.

I have to keep this in mind, because the task of gaining readers can take as long, or even longer, than the task of learning to write.

Published on February 14, 2016 18:02

Soft Sighing Strains

Sometimes, a story that impressed me when I was nine years old not only survives the passage of decades, but turns out to be stranger than I had realized.

"Noise" was my first exposure to the work of Jack Vance, and I went on to read a lot more by him during my 'teens. My reactions were mixed. Some of the stories I admired for their intensity and clever details -- "The Dragon Masters," for example, or "The Moon Moth." Others felt emotionally hollow; lacking all conviction of detail or mood, they seemed less like stories written than stories typed. The worst example of this would be "The Last Castle."

After a while, the doubts appeared. Vance had been praised for the sensual details of his work, but I found that other writers had better eyes for setting. I preferred Clark Ashton Smith, J. G. Ballard, Avram Davidson, M. John Harrison, Gardner Dozois, C. L. Moore: writers who presented their worlds with a vivid sensory conviction that went far beyond anything I had found in Vance. And although he had been praised as a stylist, I found more precision and flavour in the best prose of Damon Knight, James Blish, Brian Aldiss.

For me, his greatest limitation was a focus on surfaces, rarely on depths. His detached, ironic approach to narrative could only take him so far, and it often kept him away from those fundamental things that make fiction worth reading. A typical example: at one point in The Languages of Pao, the protagonist was left alone with a woman who took an interest in him. Most writers would use this moment to uncover a character's inner life, to suggest the emotions and motivations that he would normally keep hidden; but given this opportunity, Vance drew the curtain and slipped away. "The Last Castle" went even further in avoiding depths, and I could never understand its appeal.

And so, by the time I was twenty, I had stopped reading Jack Vance. Curiosity brought me back to his work a few years ago, and my reactions have been much the same: he will never be a favourite of mine, and much of his work is not for me, but some of the stories I loved in my 'teens I would still call wonderful.

"Noise," for example.

The story begins with a clumsy prologue:

The notebook, however, in a quiet and more confident style, tells an enigmatic story in stark yet colourful detail:

When I was nine years old, I loved the simple magic of the story. It offered no explanations, no background. It only conveyed the baffled response of one man to a strange yet welcoming place, and it did this one thing with clarity and confidence.

As I read this again last week, what struck me was the absence of those ingredients often considered fundamental to fiction. Is there any hint of characterization? No. Of conflict? Not really. Of rising tension? Hardly at all. Curiosity about the next page? This might work on a first reading, but not on the next.

Instead, what drives the story, what kept me reading, is a quality hard to describe yet undeniable: the allure of wonder. With stark imagery, with simple use of colour, "Noise" tugged me towards a mysterious, beautiful place, and made me want to stay.

People who read and write must decide for themselves what works in a short story. For me, quite often, this can be hard to specify; I can only point, and quote, and say, Magical. That was my response to "Noise" when I was nine years old, and this is how I feel about it now.

"Noise" was my first exposure to the work of Jack Vance, and I went on to read a lot more by him during my 'teens. My reactions were mixed. Some of the stories I admired for their intensity and clever details -- "The Dragon Masters," for example, or "The Moon Moth." Others felt emotionally hollow; lacking all conviction of detail or mood, they seemed less like stories written than stories typed. The worst example of this would be "The Last Castle."

After a while, the doubts appeared. Vance had been praised for the sensual details of his work, but I found that other writers had better eyes for setting. I preferred Clark Ashton Smith, J. G. Ballard, Avram Davidson, M. John Harrison, Gardner Dozois, C. L. Moore: writers who presented their worlds with a vivid sensory conviction that went far beyond anything I had found in Vance. And although he had been praised as a stylist, I found more precision and flavour in the best prose of Damon Knight, James Blish, Brian Aldiss.

For me, his greatest limitation was a focus on surfaces, rarely on depths. His detached, ironic approach to narrative could only take him so far, and it often kept him away from those fundamental things that make fiction worth reading. A typical example: at one point in The Languages of Pao, the protagonist was left alone with a woman who took an interest in him. Most writers would use this moment to uncover a character's inner life, to suggest the emotions and motivations that he would normally keep hidden; but given this opportunity, Vance drew the curtain and slipped away. "The Last Castle" went even further in avoiding depths, and I could never understand its appeal.

And so, by the time I was twenty, I had stopped reading Jack Vance. Curiosity brought me back to his work a few years ago, and my reactions have been much the same: he will never be a favourite of mine, and much of his work is not for me, but some of the stories I loved in my 'teens I would still call wonderful.

"Noise," for example.

The story begins with a clumsy prologue:

Captain Hess placed a notebook on the desk and hauled a chair up under his sturdy buttocks. Pointing to the notebook, he said, “That’s the property of your man Evans. He left it aboard the ship.”

Galispell asked in faint surprise, “There was nothing else? No letter?”

“No, sir, not a thing. That notebook was all he had when we picked him up.”

Galispell rubbed his fingers along the scarred fibers of the cover. “Understandable, I suppose.” He flipped back the cover. “Hmmmm.”

The notebook, however, in a quiet and more confident style, tells an enigmatic story in stark yet colourful detail:

The blue day goes. The sapphire sun wanders into the western forest, the sky glooms to blue-black, the stars show like unfamiliar home-places.

For some time now I have heard no music; perhaps it has been so all-present that I neglect it.

The blue star is gone, the air chills. I think that deep night is on me indeed…I hear a throb of sound, plangent, plaintive; I turn my head. The east glows pale pearl. A silver globe floats up into the night like a lotus drifting on a lake: a great ball like six of Earth’s full moons. Is this a sun, a satellite, a burnt-out star? What a freak of cosmology I have chanced upon!

The silver sun -- I must call it a sun, although it casts a cool satin light -- moves in an aureole like oyster-shell. Once again the color of the planet changes. The lake glistens like quicksilver, the trees are hammered metal… The silver star passes over a high wrack of clouds, and the music seems to burst forth as if somewhere someone flung wide curtains: the music of moonlight, medieval marble, piazzas with slim fluted colonnades, soft sighing strains….

When I was nine years old, I loved the simple magic of the story. It offered no explanations, no background. It only conveyed the baffled response of one man to a strange yet welcoming place, and it did this one thing with clarity and confidence.

The star falls; the forest receives it. The sky dulls, and night has come.

I face the east, my back pressed to the pragmatic hull of my lifeboat. Nothing.

I have no conception of the passage of time. Darkness, timelessness. Somewhere clocks turn minute hands, second hands, hour hands -- I stand staring into the night, perhaps as slow as a sandstone statue, perhaps as feverish as a salamander.

In the darkness there is a peculiar cessation of sound. The music has dwindled; down through a series of wistful chords, a forlorn last cry….

A glow in the east, a green glow, spreading. Up rises a magnificent green sphere, the essence of all green, the tincture of emeralds, glowing as grass, fresh as mint, deep as the sea.

A throb of sound: rhythmical strong music, swinging and veering.

The green light floods the planet, and I prepare for the green day.

As I read this again last week, what struck me was the absence of those ingredients often considered fundamental to fiction. Is there any hint of characterization? No. Of conflict? Not really. Of rising tension? Hardly at all. Curiosity about the next page? This might work on a first reading, but not on the next.

Instead, what drives the story, what kept me reading, is a quality hard to describe yet undeniable: the allure of wonder. With stark imagery, with simple use of colour, "Noise" tugged me towards a mysterious, beautiful place, and made me want to stay.

People who read and write must decide for themselves what works in a short story. For me, quite often, this can be hard to specify; I can only point, and quote, and say, Magical. That was my response to "Noise" when I was nine years old, and this is how I feel about it now.

Published on February 14, 2016 12:28

February 6, 2016

A Spot of Bad Luck for the Meioses

[This one defeated me, but I'll post it anyways. Meiosis is not the same as litotes; I wish I had known before I started!]

Have some wine. The Meioses?Remember them? On rocket skis?They hit a wall at 90 Gs(Hardly guaranteed to please).The impact rocked them like a sneeze.Although it burst their arteries(A little bit) and scraped their knees,And hardly helped their allergies,They made it all seem like a breezeWhen they poured themselves upon the treesLike tinsel, or like strawberriesIn a jam too red for comfort. Cheese?

Have some wine. The Meioses?Remember them? On rocket skis?They hit a wall at 90 Gs(Hardly guaranteed to please).The impact rocked them like a sneeze.Although it burst their arteries(A little bit) and scraped their knees,And hardly helped their allergies,They made it all seem like a breezeWhen they poured themselves upon the treesLike tinsel, or like strawberriesIn a jam too red for comfort. Cheese?

Published on February 06, 2016 09:38

February 5, 2016

Aposiopesis Would Have Said --

Aposiopesis tries our peace

By leaving us with nothing to rely on:

"I begin a sentence, then I cease,

And just as I have walked away in bygone --"

By leaving us with nothing to rely on:

"I begin a sentence, then I cease,

And just as I have walked away in bygone --"

Published on February 05, 2016 14:34