Mark Fuller Dillon's Blog, page 32

July 15, 2016

Two Levels

Something I've noticed while talking with francophones in my town --

English is unusual: it has two levels of grammar. The first is inconsistent, but relatively easy to learn, and it allows people to speak with ease, confidence, and clarity. The second level is hidden, and pops up when we try to write with a similar ease, confidence, and clarity; we find this harder than we had thought, because the hidden level of grammar now makes demands on us. The subjunctive mood, case forms, complexities of tense: we can talk all night and straight through to dawn without using them, but when we write, we need to understand their functions.

English is unusual: it has two levels of grammar. The first is inconsistent, but relatively easy to learn, and it allows people to speak with ease, confidence, and clarity. The second level is hidden, and pops up when we try to write with a similar ease, confidence, and clarity; we find this harder than we had thought, because the hidden level of grammar now makes demands on us. The subjunctive mood, case forms, complexities of tense: we can talk all night and straight through to dawn without using them, but when we write, we need to understand their functions.

Published on July 15, 2016 01:01

June 21, 2016

Strange in a Good Way

From the latest review of my novelette,

At First, You Hear The Silence

:

"This is a dark fantasy novelette; a strange (in a good way!) mix of sci-fi, horror, fantasy, rural life… it’s a short, tense read that starts off slow and creeps up behind you...

"The horror side of the story is well done. The birds are subtly introduced, and the silence that comes with them is as terrifying as the raptors themselves. I loved that Philippe has to get himself out of a bad situation, and his solution is masterful; I sometimes feel as if horror victims are too passive, and it added a nice air to have Philippe’s rescue of himself go so-nearly-wrong several times -- the suspense was excellent. The actual background to the horrors is nicely vague; we (and Philippe) don’t know what they want, why they’ve come, what they’re going to do next -- and it lends a suitably terrifying edge to the second half of the book that pervades the ending and leaves you feeling unsettled even after you’ve finished...."

Published on June 21, 2016 03:36

June 19, 2016

My Father's Eyes

My father was a good man, and for that reason, opaque to me. We had been close when I was a child, but when I was nine years old, we went our separate ways, emotionally; the fault was mine. And although, in his later years, I did what I could to gain some understanding of his inner life, something within me always blocked the way.

In 2004, he died suddenly and horribly on his living room sofa; my face was the last thing he saw.

After his death, I inherited his computer. One day, by accident, I found a series of digital photographs he had taken just a few months before he died. I recognized their purpose right away: he had formed a partnership with several other people to bring wireless, high-bandwidth internet service to the community, and he had mentioned to me that he needed "line of sight" information on locations where the mountains would not interfere with signals. For that perspective, he had taken these photos from one of the highest hills in the region.

I had climbed this hill many times. Even without snow, the possible ways up were never easy. My father had been a university athlete, but in his old age, he suffered from several ailments and a bone chip under one of his kneecaps. This made walking hard for him, to the point where he avoided the icy, unpaved roads all around us. Yet somehow, despite the ice, the snow, the jagged rocks, and the wind, he had climbed that mountain and taken the photos he needed.

I often think of him standing up there, in pain, with only three months left to live, doing what he had to do for the sake of his project and for the people who relied on him. From that height, he would have seen a landscape that I loved and that still reveals itself in dreams, but what he might have thought, or how he might have felt, are beyond my capacity to know.

Published on June 19, 2016 11:29

June 8, 2016

Oh, That Wretched Book!

From: Mark Dillon

Newsgroups: alt.books.ghost-fiction

Subject: *** The MEDUSA Fun-Time Quiz ***

Date: 13 July 2001 -- 20:00:41 GMT

Ahoy, shipmates! And welcome to me very own

* * * MEDUSA Fun-Time Quiz * * *

You are E. H. Visiak, noted authority on the life and work of John Milton. You intend to write a tale of "mystery, and ecstasy, & strange horror". Very well, then. Do you --

1] Conjure up an atmosphere of mystery through the careful employment of verbal effects?

2] Suggest a mood of ecstasy through elaborately detailed sensual impressions?

3] Induce a strange horror in the reader by eschewing mystery, ecstasy, vivid description, local colour, suspense, spectral atmosphere and characters with character?

You are a young lad on a sea voyage into the Unknown. En route, which is your most remarkable adventurous experience?

1] You glimpse a volcano, briefly, through the distant haze.

2] You buy a parrot.

3] You study Latin.

You are the owner of a ship at sea, and your crew has sighted a monster on board! Do you --

1] Search the ship to find the monster?

2] Question the pirate passenger who was seen many times, on land, accompanied by a monster?

3] Do *nothing* -- and tell the crew to trust in God?

You, the author, have just revealed the monster. How will you sabotage the dramatic effect of this "savage strange hideous creature"?

1] Have the monster knock on the door and... walk away.

2] Have the boatswain remark, "I see not why we should be in much dread of him...."

3] Make a joke about less-than-pretty mermaids.

4] Name the monster Jerry.

5] All of the above, dammit.

With only three chapters left before your epic anti-climax, do you, the author --

1] Hasten the action to build suspense?

2] Heighten the mood of spectral dread?

3] Halt the story to discuss the spiritual symbolism of "Psyche and Eros"?

Your protagonist is threatened by a mutant octopus! How will you, the author, suck all the fear and wonder from this anti-climactic moment?

1] Make sure that nothing much happens.

2] Hint vaguely of a spiritual threat without bothering to convey its effects or implications.

3] Have your protagonist escape with ease after eight dull pages of twilit fumbling with a tentacle.

4] All of the above, while refusing to explore the imaginative possibilities of your half-assed novel.

Which passage quoted below best conveys the flavour of this tedious book?

1] "...One of the most truly original fantastic novels in the English language. The prose is a joy to read, the vocabulary of Milton [sic] couched in the grammar of Stevenson [sic], while the plot is a heady amalgam of a boy's pirate adventure and metaphysical romance. A voyage to the South Seas culminates in a rendezvous with the sunken demesne of the monstrous octopoid Medusa, last [sic] of a prehistoric race that achieved inter-dimensional travel [?]. It seems vaguely reminiscent, in this, of Lovecraft's "The Call of Cthulhu," but is utterly unlike in spirit. Visiak achieved [sic] the terror and wonder, the sense of awe, that Lovecraft could only grasp at."

-- R. S. Hadji, TWILIGHT ZONE MAGAZINE, August 1983

2] "I believe that I once described MEDUSA as the probable outcome of Herman Melville having written TREASURE ISLAND while tripping on LSD. I can't add much to that, except to suggest that John Milton may have popped round on his way home from a week in an opium den to help him revise the final draft. We're talking heavy surreal here."

-- Karl Edward Wagner, HORROR: 100 BEST BOOKS, 1988

3] "He told me that he saw no light, but that, on a sudden, the sea was changed into a delectable land; a country of enchantment, having great tall trees, whereof the branches, with their massy broad leaves, did cast a cool delicious shade as green as emerald; and all about them, amongst bushes, bearing huge crimson blossoms, there appeared feminine and ravishing forms, all softness and delight, lifting up their alluring arms with a powerful strong enticement to come down to them.

"He said that he was exceeding fain to yield, though an old man, and though he had confidently supposed and hoped he had long ago overcome the lusts of the flesh and the seduction of the eyes, and was, indeed, in the very action of clambering over the bulwarks to cast himself incontinently down, as the rest did, into those blissful and delusory bowers, when (as he vehemently affirmed) he beheld the arm of the Almighty stretched out before him harder than granite.

"The awful spectacle took his soul with such a mighty rapture, and sense of abounding, adoring gratitude as to dispel that inordinate fleshly desire in a moment; whereupon, the airy charm dissolved and vanished away.

"These, to the best of my recollection, are his very words; and, indeed, they were lively imprinted in my mind. I am only careful to set them down; not to comment upon them -- nor on their substance either. Let them explicate this mystery who can; I leave it to the philosopher."

-- E. H. Visiak, MEDUSA (final chapter), 1929

And there ye have it, mateys: a few short paragraphs that show, with a greater force beyond me, the pointless waste of time that luckless readers call MEDUSA.

Mark Dillon

Quebec, Canada

Newsgroups: alt.books.ghost-fiction

Subject: *** The MEDUSA Fun-Time Quiz ***

Date: 13 July 2001 -- 20:00:41 GMT

Ahoy, shipmates! And welcome to me very own

* * * MEDUSA Fun-Time Quiz * * *

You are E. H. Visiak, noted authority on the life and work of John Milton. You intend to write a tale of "mystery, and ecstasy, & strange horror". Very well, then. Do you --

1] Conjure up an atmosphere of mystery through the careful employment of verbal effects?

2] Suggest a mood of ecstasy through elaborately detailed sensual impressions?

3] Induce a strange horror in the reader by eschewing mystery, ecstasy, vivid description, local colour, suspense, spectral atmosphere and characters with character?

You are a young lad on a sea voyage into the Unknown. En route, which is your most remarkable adventurous experience?

1] You glimpse a volcano, briefly, through the distant haze.

2] You buy a parrot.

3] You study Latin.

You are the owner of a ship at sea, and your crew has sighted a monster on board! Do you --

1] Search the ship to find the monster?

2] Question the pirate passenger who was seen many times, on land, accompanied by a monster?

3] Do *nothing* -- and tell the crew to trust in God?

You, the author, have just revealed the monster. How will you sabotage the dramatic effect of this "savage strange hideous creature"?

1] Have the monster knock on the door and... walk away.

2] Have the boatswain remark, "I see not why we should be in much dread of him...."

3] Make a joke about less-than-pretty mermaids.

4] Name the monster Jerry.

5] All of the above, dammit.

With only three chapters left before your epic anti-climax, do you, the author --

1] Hasten the action to build suspense?

2] Heighten the mood of spectral dread?

3] Halt the story to discuss the spiritual symbolism of "Psyche and Eros"?

Your protagonist is threatened by a mutant octopus! How will you, the author, suck all the fear and wonder from this anti-climactic moment?

1] Make sure that nothing much happens.

2] Hint vaguely of a spiritual threat without bothering to convey its effects or implications.

3] Have your protagonist escape with ease after eight dull pages of twilit fumbling with a tentacle.

4] All of the above, while refusing to explore the imaginative possibilities of your half-assed novel.

Which passage quoted below best conveys the flavour of this tedious book?

1] "...One of the most truly original fantastic novels in the English language. The prose is a joy to read, the vocabulary of Milton [sic] couched in the grammar of Stevenson [sic], while the plot is a heady amalgam of a boy's pirate adventure and metaphysical romance. A voyage to the South Seas culminates in a rendezvous with the sunken demesne of the monstrous octopoid Medusa, last [sic] of a prehistoric race that achieved inter-dimensional travel [?]. It seems vaguely reminiscent, in this, of Lovecraft's "The Call of Cthulhu," but is utterly unlike in spirit. Visiak achieved [sic] the terror and wonder, the sense of awe, that Lovecraft could only grasp at."

-- R. S. Hadji, TWILIGHT ZONE MAGAZINE, August 1983

2] "I believe that I once described MEDUSA as the probable outcome of Herman Melville having written TREASURE ISLAND while tripping on LSD. I can't add much to that, except to suggest that John Milton may have popped round on his way home from a week in an opium den to help him revise the final draft. We're talking heavy surreal here."

-- Karl Edward Wagner, HORROR: 100 BEST BOOKS, 1988

3] "He told me that he saw no light, but that, on a sudden, the sea was changed into a delectable land; a country of enchantment, having great tall trees, whereof the branches, with their massy broad leaves, did cast a cool delicious shade as green as emerald; and all about them, amongst bushes, bearing huge crimson blossoms, there appeared feminine and ravishing forms, all softness and delight, lifting up their alluring arms with a powerful strong enticement to come down to them.

"He said that he was exceeding fain to yield, though an old man, and though he had confidently supposed and hoped he had long ago overcome the lusts of the flesh and the seduction of the eyes, and was, indeed, in the very action of clambering over the bulwarks to cast himself incontinently down, as the rest did, into those blissful and delusory bowers, when (as he vehemently affirmed) he beheld the arm of the Almighty stretched out before him harder than granite.

"The awful spectacle took his soul with such a mighty rapture, and sense of abounding, adoring gratitude as to dispel that inordinate fleshly desire in a moment; whereupon, the airy charm dissolved and vanished away.

"These, to the best of my recollection, are his very words; and, indeed, they were lively imprinted in my mind. I am only careful to set them down; not to comment upon them -- nor on their substance either. Let them explicate this mystery who can; I leave it to the philosopher."

-- E. H. Visiak, MEDUSA (final chapter), 1929

And there ye have it, mateys: a few short paragraphs that show, with a greater force beyond me, the pointless waste of time that luckless readers call MEDUSA.

Mark Dillon

Quebec, Canada

Published on June 08, 2016 22:52

May 26, 2016

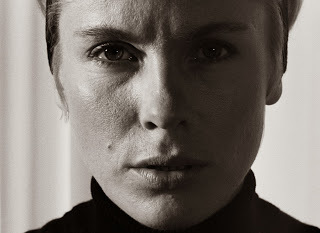

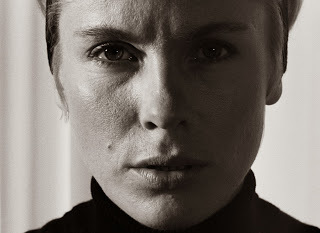

Ingmar Bergman's PERSONA

One of the great strengths of horror is that it's not a genre, but a mood, a perspective, a suspicion, and so it can use any approach, any type of plot, image, or character, to achieve its ends.

Bergman understood this, and reaped the benefits.

He also understood that few things are more disturbing, more alien, than a human face.

Bergman understood this, and reaped the benefits.

He also understood that few things are more disturbing, more alien, than a human face.

Published on May 26, 2016 11:45

April 24, 2016

Rebellion

I'll go anywhere I can to learn about writing, and tonight I was drawn to a play by someone I'd not read before: Henry Arthur Jones.

I was prompted by a statement of William Archer's, in his book, Play-Making, A Manual of Craftsmanship (1912):

Out of curiosity, I read the play, and it was indeed well-handled. It held my attention from the first page to the last, which is more than I can say for too much of what I read these days, or try to read.

Beyond the craftsmanship, though, what struck me was the writer's attitude towards the conventional sexual morality of his day (1905). This play about a "fallen woman" does not lack compassion, but it does lack rebellion, or even perspective on the social and political nature of morality:

I can just imagine Oscar Wilde, H. G. Wells, Anton Chekhov, Guy de Maupassant, or Henrik Ibsen raising their eyebrows at this idea of "the hard law from above." But it does make me realize that almost every writer I've taken to heart over the decades has been oppositional, individualistic, skeptical, or humane enough to pick a fight with conventional ideas from his or her own time, to the point where I expect this opposition automatically.

I'm glad that I read Mrs. Dane's Defence, but not only because it's a well-crafted play; it also reminded me that rebellion, in art as in life, is exceptional, never the norm.

I was prompted by a statement of William Archer's, in his book, Play-Making, A Manual of Craftsmanship (1912):

"The first three acts of [Mrs Dane's Defence] may be cited as an excellent example of dexterous preparation and development. Our interest in the sequence of events is aroused, sustained, and worked up to a high tension with consummate skill. There is no feverish overcrowding of incident.... The action moves onwards, unhasting, unresting, and the finger-posts [the foreshadowing details] are placed just where they are wanted."

Out of curiosity, I read the play, and it was indeed well-handled. It held my attention from the first page to the last, which is more than I can say for too much of what I read these days, or try to read.

Beyond the craftsmanship, though, what struck me was the writer's attitude towards the conventional sexual morality of his day (1905). This play about a "fallen woman" does not lack compassion, but it does lack rebellion, or even perspective on the social and political nature of morality:

MRS. DANE: Good-bye, Sir Daniel. Don't you think the world is very hard on a woman?

SIR DANIEL: It isn't the world that's hard. It isn't men and women. Am I hard ? Call on me at any time, and you shall find me the truest friend to you and yours. Is Lady Eastney hard? She has been fighting all the week to save you.

MRS. DANE: Then who is it, what is it, drives me out?

SIR DANIEL: The law, the hard law that we didn't make, that we would break if we could, for we are all sinners at heart -- the law that is above us all, made for us all, that we can't escape from, that we must keep or perish.

I can just imagine Oscar Wilde, H. G. Wells, Anton Chekhov, Guy de Maupassant, or Henrik Ibsen raising their eyebrows at this idea of "the hard law from above." But it does make me realize that almost every writer I've taken to heart over the decades has been oppositional, individualistic, skeptical, or humane enough to pick a fight with conventional ideas from his or her own time, to the point where I expect this opposition automatically.

I'm glad that I read Mrs. Dane's Defence, but not only because it's a well-crafted play; it also reminded me that rebellion, in art as in life, is exceptional, never the norm.

Published on April 24, 2016 22:23

April 16, 2016

I completed this translation last year, in September, but...

I completed this translation last year, in September, but was never happy with it. This morning, I changed a few nouns, then decided that enough was enough -- here it is.

(I'm still unhappy, because I re-arranged the emphasis in the final stanza. I do what I can to preserve the poet's choice of structure, but in this case, I ended with a pronoun that he had placed much earlier. I was wrong to do this, but my way seemed to work slightly better... at least, in English. That's no excuse, I know!)

- - - - -

LA CONQUE.

Par quels froids Océans, depuis combien d'hivers,

-- Qui le saura jamais, Conque frêle et nacrée! --

La houle, les courants et les raz de marée

T'ont-ils roulée au creux de leurs abîmes verts?

Aujourd'hui, sous le ciel, loin des reflux amers,

Tu t'es fait un doux lit de l'arène dorée.

Mais ton espoir est vain. Longue et désespérée,

En toi gémit toujours la grande voix des mers.

Mon âme est devenue une prison sonore:

Et comme en tes replis pleure et soupire encore

La plainte du refrain de l'ancienne clameur;

Ainsi du plus profond de ce cœur trop plein d'Elle,

Sourde, lente, insensible et pourtant éternelle,

Gronde en moi l'orageuse et lointaine rumeur.

-- From

LES TROPHÉES, by José-Maria de Heredia.

Alphonse Lemerre, Éditeur. Paris, 1893.

(I'm still unhappy, because I re-arranged the emphasis in the final stanza. I do what I can to preserve the poet's choice of structure, but in this case, I ended with a pronoun that he had placed much earlier. I was wrong to do this, but my way seemed to work slightly better... at least, in English. That's no excuse, I know!)

THE CONCH,

by José-Maria de Heredia.

In what chill oceans, for how many winters -- who will ever know, frail and nacreous conch? -- have the currents, the swells, and the tides rolled you in the hollows of their green abyss?

Today, under the sky, far from the tide's bitter ebb, you have made for yourself a soft bed in the golden arena, but you hope in vain. Drawn-out and despairing and always within you moans the great voice of the seas.

My soul has become a sounding prison: and just as the moaned refrain of that ancient clamour still weeps and sighs within your folds,

In the same way, dull, slow, numb yet somehow eternal, growls the distant, stormy din from the deeps of this heart too full of Her.

- - - - -

LA CONQUE.

Par quels froids Océans, depuis combien d'hivers,

-- Qui le saura jamais, Conque frêle et nacrée! --

La houle, les courants et les raz de marée

T'ont-ils roulée au creux de leurs abîmes verts?

Aujourd'hui, sous le ciel, loin des reflux amers,

Tu t'es fait un doux lit de l'arène dorée.

Mais ton espoir est vain. Longue et désespérée,

En toi gémit toujours la grande voix des mers.

Mon âme est devenue une prison sonore:

Et comme en tes replis pleure et soupire encore

La plainte du refrain de l'ancienne clameur;

Ainsi du plus profond de ce cœur trop plein d'Elle,

Sourde, lente, insensible et pourtant éternelle,

Gronde en moi l'orageuse et lointaine rumeur.

-- From

LES TROPHÉES, by José-Maria de Heredia.

Alphonse Lemerre, Éditeur. Paris, 1893.

Published on April 16, 2016 03:57

April 14, 2016

Coal-Cored Comments

Communities have torn themselves apart,

Blackened lives for principle, denounced

The stranger at the door for being strange.

Sometimes, knocking at the door at all

Is flint enough to spark a scorching fight.

Your thoughts, and mine, have blistered at the touch

Of coal-cored comments. How the ashes fly

On currents that affection cannot ride

When we speak at our best, and for the best.

Anger is the torch that fires a town

When friendship's glow could hardly warm a speck.

Blackened lives for principle, denounced

The stranger at the door for being strange.

Sometimes, knocking at the door at all

Is flint enough to spark a scorching fight.

Your thoughts, and mine, have blistered at the touch

Of coal-cored comments. How the ashes fly

On currents that affection cannot ride

When we speak at our best, and for the best.

Anger is the torch that fires a town

When friendship's glow could hardly warm a speck.

Published on April 14, 2016 11:54

April 8, 2016

Veins and Stars

Elizabeth Bowen:

-- "Mysterious Kôr," from Ivy Gripped the Steps. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1946.

Callie reached out and put off her bedside lamp.

At once she knew that something was happening -- outdoors, in the street, the whole of London, the world. An advance, an extraordinary movement was silently taking place; blue-white beams overflowed from it, silting, dropping round the edges of the muffled black-out curtains. When, starting up, she knocked a fold of the curtain, a beam like a mouse ran across her bed. A searchlight, the most powerful of all time, might have been turned full and steady upon her defended window; finding flaws in the black-out stuff, it made veins and stars. Once gained by this idea of pressure she could not lie down again; she sat tautly, drawn-up knees touching her breasts, and asked herself if there were anything she should do. She parted the curtains, opened them slowly wider, looked out -- and was face to face with the moon.

-- "Mysterious Kôr," from Ivy Gripped the Steps. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1946.

Published on April 08, 2016 01:09

March 29, 2016

De grands chantiers d'affolement

Translating Verhaeren is beyond my skill, and so I forced myself to do it. I've never been wise.

La Morte,

Émile Verhaeren.

En sa robe, couleur de fiel et de poison,

Le cadavre de ma raison

Traîne sur la Tamise.

Des ponts de bronze, où les wagons

Entrechoquent d'interminables bruits de gonds

Et des voiles de bateaux sombres

Laissent sur elle, choir leurs ombres,

Sans qu'une aiguille, à son cadran, ne bouge,

Un grand beffroi masqué de rouge

La regarde, comme quelqu'un

Immensément de triste et de défunt.

Elle est morte de trop savoir,

De trop vouloir sculpter la cause,

Dans le socle de granit noir,

De chaque être et de chaque chose,

Elle est morte, atrocement,

D'un savant empoisonnement,

Elle est morte aussi d'un délire

Vers un absurde et rouge empire

Ses nerfs ont éclaté,

Tel soir illuminé de fête,

Qu'elle sentait déjà le triomphe flotter

Comme des aigles, sur sa tête.

Elle est morte n'en pouvant plus,

L'ardeur et les vouloirs moulus,

Et c'est elle qui s'est tuée,

Infiniment exténuée.

Au long des funèbres murailles,

Au long des usines de fer

Dont les marteaux tonnent l'éclair,

Elle se traîne aux funérailles.

Ce sont des quais et des casernes,

Des quais toujours et leurs lanternes,

Immobiles et lentes filandières

Des ors obscurs de leurs lumières

Ce sont des tristesses de pierres,

Maison de briques, donjon en noir

Dont les vitres, mornes paupières,

S'ouvrent dans le brouillard du soir;

Ce sont de grands chantiers d'affolement,

Pleins de barques démantelées

Et de vergues écartelées

Sur un ciel de crucifiement.

En sa robe de joyaux morts, que solennise

L'heure de pourpre à l'horizon,

Le cadavre de ma raison

Traîne sur la Tamise.

Elle s'en va vers les hasards

Au fond de l'ombre et des brouillards,

Au long bruit sourd des tocsins lourds,

Cassant leur aile, au coin des tours.

Derrière elle, laissant inassouvie

La ville immense de la vie;

Elle s'en va vers l'inconnu noir

Dormir en des tombeaux de soir.

Là-bas, où les vagues lentes et fortes,

Ouvrant leurs trous illimités,

Engloutissent à toute éternité

Les mortes.

- - - - -

From

POÈMES, by Émile Verhaeren.

Mercure de France, Paris, 1917.

The Corpse,

by Émile Verhaeren.

In her dress the colour of bile and poison, the corpse of my reason is dragged along the Thames.

The bridges of bronze, where the carriages bang together with an interminable sound of hinges, and the sails of dark boats, let their shadows fall upon her. Without a moving handle on its clock face, a tall belfry masked in red stares at her like someone immensely [preoccupied?] with death and sorrow.

She died from having known too much, from having wanted too much to sculpt the motive, on the pedestal of black stone, of every being and of every thing; she died, atrociously, from an expert empoisoning; she died, as well, from a delirium for [towards] an absurd and red empire. Her nerves had burst, on some bright evening of celebration, when she felt its triumph drift, like eagles, over its head. She died not being able to take any more, with her ardours and desires crushed; infinitely exhausted, she killed herself.

Along the funereal walls, along the iron foundries where the hammers beat out sparks, she is dragged to the funeral.- - - - -

These are wharves and barracks, always wharves and their lanterns, unmoving and slow spinners of dim gold from their lights; these are sadnesses of stone, a brick house, a castle keep of black where the windows, glum eyelids, open to the fog of night; these are vast marinas of insanity, full of dismantled boats and of sail yards docked against a sky of crucifixion.

In her dress of dead jewels that solemnizes the horizon's hour of purple, the corpse of my reason is dragged along the Thames.

She moves toward the perils in the depths of shadows and fog, to the long, dull noise of heavy bells breaking their wings at steeple corners. Unfulfilled, leaving behind her the great city of life, she heads for the black unknown, to sleep in the tombs of the night, down there, where the slow, strong waves, opening their limitless pits, swallow, for all eternity, the dead.

La Morte,

Émile Verhaeren.

En sa robe, couleur de fiel et de poison,

Le cadavre de ma raison

Traîne sur la Tamise.

Des ponts de bronze, où les wagons

Entrechoquent d'interminables bruits de gonds

Et des voiles de bateaux sombres

Laissent sur elle, choir leurs ombres,

Sans qu'une aiguille, à son cadran, ne bouge,

Un grand beffroi masqué de rouge

La regarde, comme quelqu'un

Immensément de triste et de défunt.

Elle est morte de trop savoir,

De trop vouloir sculpter la cause,

Dans le socle de granit noir,

De chaque être et de chaque chose,

Elle est morte, atrocement,

D'un savant empoisonnement,

Elle est morte aussi d'un délire

Vers un absurde et rouge empire

Ses nerfs ont éclaté,

Tel soir illuminé de fête,

Qu'elle sentait déjà le triomphe flotter

Comme des aigles, sur sa tête.

Elle est morte n'en pouvant plus,

L'ardeur et les vouloirs moulus,

Et c'est elle qui s'est tuée,

Infiniment exténuée.

Au long des funèbres murailles,

Au long des usines de fer

Dont les marteaux tonnent l'éclair,

Elle se traîne aux funérailles.

Ce sont des quais et des casernes,

Des quais toujours et leurs lanternes,

Immobiles et lentes filandières

Des ors obscurs de leurs lumières

Ce sont des tristesses de pierres,

Maison de briques, donjon en noir

Dont les vitres, mornes paupières,

S'ouvrent dans le brouillard du soir;

Ce sont de grands chantiers d'affolement,

Pleins de barques démantelées

Et de vergues écartelées

Sur un ciel de crucifiement.

En sa robe de joyaux morts, que solennise

L'heure de pourpre à l'horizon,

Le cadavre de ma raison

Traîne sur la Tamise.

Elle s'en va vers les hasards

Au fond de l'ombre et des brouillards,

Au long bruit sourd des tocsins lourds,

Cassant leur aile, au coin des tours.

Derrière elle, laissant inassouvie

La ville immense de la vie;

Elle s'en va vers l'inconnu noir

Dormir en des tombeaux de soir.

Là-bas, où les vagues lentes et fortes,

Ouvrant leurs trous illimités,

Engloutissent à toute éternité

Les mortes.

- - - - -

From

POÈMES, by Émile Verhaeren.

Mercure de France, Paris, 1917.

Published on March 29, 2016 00:01