Mark Fuller Dillon's Blog, page 36

December 12, 2015

Miserable Spectacle

When people send me early drafts to criticize, I always recommend revising aloud. The ear can pick up awkward patterns often concealed from the eye, like the EEs of too many adverbs, or the monotonously-chiming INGs of present participles used in place of the simple past tense.

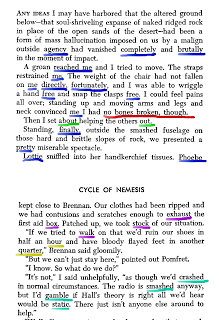

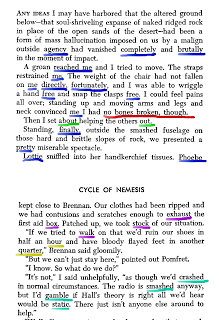

As an example of how badly prose can fall into mindless repetition, here's a passage from Cycle of Nemesis, by Kenneth Bulmer (Ace Books, 1967). This could have been avoided....

As an example of how badly prose can fall into mindless repetition, here's a passage from Cycle of Nemesis, by Kenneth Bulmer (Ace Books, 1967). This could have been avoided....

Published on December 12, 2015 23:47

December 11, 2015

What We Say and How We Say It

I've long believed that how a story is told matters more than what a story tells, that even a story of strong conceptual interest can be ruined by weak prose and poor choices in structure. As proof, I'd offer A. Merritt's "The People of the Pit" (ALL-STORY WEEKLY, January 5, 1918).

Merritt's influence on American science fiction, fantasy, and horror should not be underestimated, but many would agree that the writers he influenced were better craftsmen than he was -- Edmond Hamilton, Jack Williamson, Henry Kuttner, and best of all, C. L. Moore. They responded to his ideas, which again, should not be underestimated, but ideas can only take a story so far, as they understood and reflected in their best work.

"The People of the Pit" does what it can to suggest a mood of alien horror, but it falls prey to Merritt's lack of skill with storytelling and with language.

For one thing, Merritt sets the story in a frame. A frame can be used effectively in a certain kind of retrospective story, in which the suspense of an outcome carries less weight than a narrator's inability to understand what happened. Two of my favourite examples of a frame used well are Walter de la Mare's "The Almond Tree," and William Sansom's "A Wedding;" in both cases, the story would lose its impact without a frame. But in "The People of the Pit," a story about capture and escape, much of the tension and immediacy are weakened, because the tale is told by a dying man who has already managed to get away.

But Merritt does even more to undermine his narrative: he writes badly. He falls back on stylistic tricks that seem ridiculous on their first appearance, and then he repeats them.

I'll spare you -- the rest. Yes! I will! Too much exposure to writing this artless can lead to -- pain. It can lead to -- unearthly pain. A pain that is not -- of this Earth!

None of this would hurt if the story itself were lazy hackwork, something to be tossed aside with a wince, but Merritt has good intentions, here: he wants to convey an experience beyond the human, a challenge for any writer. He fails, not through lack of ambition, but through weakness in craft. C. L. Moore would take up this challenge two decades later, with her "Northwest Smith" and "Jirel of Joiry" stories. I'd like to believe that she learned from his failures and avoided the traps that hindered his work; what saved her was a greater skill with language.

For this one reason, I'd recommend "The People of the Pit" to anyone who writes fantasy or strange or science fiction stories, as an example of good intentions gone wrong. What we say matters, but how we say it matters more.

Merritt's influence on American science fiction, fantasy, and horror should not be underestimated, but many would agree that the writers he influenced were better craftsmen than he was -- Edmond Hamilton, Jack Williamson, Henry Kuttner, and best of all, C. L. Moore. They responded to his ideas, which again, should not be underestimated, but ideas can only take a story so far, as they understood and reflected in their best work.

"The People of the Pit" does what it can to suggest a mood of alien horror, but it falls prey to Merritt's lack of skill with storytelling and with language.

For one thing, Merritt sets the story in a frame. A frame can be used effectively in a certain kind of retrospective story, in which the suspense of an outcome carries less weight than a narrator's inability to understand what happened. Two of my favourite examples of a frame used well are Walter de la Mare's "The Almond Tree," and William Sansom's "A Wedding;" in both cases, the story would lose its impact without a frame. But in "The People of the Pit," a story about capture and escape, much of the tension and immediacy are weakened, because the tale is told by a dying man who has already managed to get away.

But Merritt does even more to undermine his narrative: he writes badly. He falls back on stylistic tricks that seem ridiculous on their first appearance, and then he repeats them.

"Then -- I ran across the road!"

"The road!" cried Anderson incredulously.

"The road," said the crawling man. "A fine smooth stone road."

- - - - -

"A stairway led down into the pit!"

"A stairway!" we cried.

"A stairway," repeated the crawling man as patiently as before.

- - - - -

"But who could build such a stairway as that?" I said. "A stairway built into the wall of a precipice and leading down into a bottomless pit!"

"Not bottomless," said the crawling man quietly. "There was a bottom. I reached it!"

"Reached it?" we repeated.

"Yes, by the stairway," answered the crawling man. "You see -- I went down it!

"Yes," he said. "I went down the stairway."

- - - - -

"They hurried, they sauntered, they bowed, they stopped and whispered -- and there was nothing under them!"

"Nothing under them!" breathed Anderson.

"No," he went on, "that was the terrible part of it -- there was nothing under them."

I'll spare you -- the rest. Yes! I will! Too much exposure to writing this artless can lead to -- pain. It can lead to -- unearthly pain. A pain that is not -- of this Earth!

None of this would hurt if the story itself were lazy hackwork, something to be tossed aside with a wince, but Merritt has good intentions, here: he wants to convey an experience beyond the human, a challenge for any writer. He fails, not through lack of ambition, but through weakness in craft. C. L. Moore would take up this challenge two decades later, with her "Northwest Smith" and "Jirel of Joiry" stories. I'd like to believe that she learned from his failures and avoided the traps that hindered his work; what saved her was a greater skill with language.

For this one reason, I'd recommend "The People of the Pit" to anyone who writes fantasy or strange or science fiction stories, as an example of good intentions gone wrong. What we say matters, but how we say it matters more.

Published on December 11, 2015 06:20

December 9, 2015

Nine Of Them Lived

Leigh Brackett:

-- From From "The Citadel of Lost Ages," by Leigh Brackett, in The Halfling, Ace Books, 1973.

Cover by Earle Bergey; December, 1950.

One of the horses died. They flayed him and dried the meat.

"They will all die," said Lannar grimly. "They will give us hides and food for the rest of our journey." He was a desert man and did not like to watch the death of horses.

The Sun became a red ember on the horizon behind them. They went down into a valley filled with snow and darkness and when they reached the other side the Sun was gone beyond the higher hills. Arika whispered, "This is what men call the Shadow."

There was still light in the sky. The land began to slope gradually downward, flattening out. Here there were no trees, nor even the stunted scrub that had grown to the edge of the Shadow. The wind-swept rocks were covered with wrinkled lichens and the frozen earth was always white.

One by one the horses died. The frozen meat was hidden by the way so that there should be food for the return march -- if there was to be one. The men suffered from the cold. They were used to the dry heat of the desert. Three of them sickened and died and one was killed by a fall.

The Shadow deepened imperceptibly into night. The rolling rusty clouds of the dayside had become the greyer clouds of storm and fog. The men toiled through dimming mist and falling snow that turned at last to utter darkness.

Lannar turned a lined and haggard face to Fenn. "Madmen!" he muttered. And that was all.

They passed through the belt of storm. There came a time when the lower air was clear and a shifting wind began to tear away the clouds from the sky.

The pace of the men slowed, then halted altogether. They watched, caught in a stasis of awe and fear too deep for utterance. Fenn saw that there was a pallid eerie radiance somewhere behind the driving clouds. Arika's hand crept into his and clung there. But Malech stood apart, his head lifted, his shining eyes fixed upon the sky.

A rift, a great ragged valley sown with stars. It widened, and the clouds were swept away, and the sky crashed down upon the waiting men, children of eternal day who had never seen the night.

They stared into the black depths of space, burning with a million points of icy fire. And the demoniac face of the Moon stared back at them, pocked with great shadows, immense and leering, with a look of death upon it.

Someone voiced a thin, wavering scream. A man turned and began to run along the backtrail, floundering, falling, clawing his way back toward the light he had left forever.

Panic took hold of the men. Some of them fell down and covered their heads. Some stood still, their hands plucking at sword and axe, all sense gone out of them. And Malech laughed. He leaped up on a hummock of ice, standing tall above them in the cold night so that his head seemed crowned with blazing stars. "What are you afraid of? You fools! It's the moon and stars. Your fathers knew them and they were not afraid!"

The scorn and the strength that were in him roused the anger of the men, giving their fear an outlet. They rushed toward him and Malech would have died there in the midst of his laughter if Fenn and Lannar together had not turned them back.

"It's true!" Fenn cried. "I have seen them. I have seen the night as it was before the Destruction. There is nothing to fear."

But he was as terrified as they.

Fenn and Lannar and the bearded Malech who had shed every trace of humanity, beat the men into line again and got them moving, fifteen of the twenty who had started, alone in the Great Dark. Tiny motes of life, creeping painfully across the dead white desolation under the savage stars. The cold Moon watched them and something of its light of madness came into their eyes and did not go away.

Fifteen -- twelve of these lived to see the riven ice of the ocean, a glittering chaos flung out across the world. Malech looked toward the east, where the Moon was rising.

Fenn heard him say, "From beyond the ocean, from the heartland of the Great Dark -- that is where we came from, the New Men who conquered the earth!"

Following the tattered map they turned northward along the coast. They were scarecrows now, half starved, half frozen, forgetting that they had ever lived another life under a warm Sun -- almost forgetting why they had left that life behind them.

Nine of them lived to see an island between two frozen rivers near the frozen sea and on that island the skeletal towers of a city buried in the ice.

Nine of them lived to see New York.

-- From From "The Citadel of Lost Ages," by Leigh Brackett, in The Halfling, Ace Books, 1973.

Cover by Earle Bergey; December, 1950.

Published on December 09, 2015 15:34

December 1, 2015

Grammar and Autonomy

In his book,

The War Against Grammar

, David Mulroy argues that grammar instruction early in school can give students autonomy. By instilling a sense of what can be effective and clear in writing, it frees them from a teacher's opinions, and helps to build self-confidence. This, in turn, can encourage them to experiment independently, both in school and at home. (He offers many examples of lively writing from even the younger students who were taught grammar rigorously.)

As I went through his argument, I realized that the benefits of learning grammar might not only help writers to express themselves with clarity, economy, and force (an axiom for me). It might also help them to face the inevitable mud-storm of rejection. All too often, rejection slips arrive without context, and writers can only guess what might have gone wrong. A deep awareness of grammar can eliminate one concern.

At the same time, it can prepare unconventional or uncommercial writers for the day when they might have to publish their own work. When they revise, all writers become editors; but when they publish, they have to become pitiless vultures with an eye for limping clauses. The more training in grammar they receive, the more skilfull they can be at scenting the reek of illness on a page.

The craft of writing can be hard enough to learn on its own. Without a firm awareness of the parts of speech, and of how they function together as grammar, writers take on a punishing task. That's not a fate I'd wish for anyone.

As I went through his argument, I realized that the benefits of learning grammar might not only help writers to express themselves with clarity, economy, and force (an axiom for me). It might also help them to face the inevitable mud-storm of rejection. All too often, rejection slips arrive without context, and writers can only guess what might have gone wrong. A deep awareness of grammar can eliminate one concern.

At the same time, it can prepare unconventional or uncommercial writers for the day when they might have to publish their own work. When they revise, all writers become editors; but when they publish, they have to become pitiless vultures with an eye for limping clauses. The more training in grammar they receive, the more skilfull they can be at scenting the reek of illness on a page.

The craft of writing can be hard enough to learn on its own. Without a firm awareness of the parts of speech, and of how they function together as grammar, writers take on a punishing task. That's not a fate I'd wish for anyone.

Published on December 01, 2015 22:33

November 17, 2015

That'd Be'd Unreadable

From

"Shall We Join The Hades?"

Horror in the Modern Style by Ran Screaming.

"Shall We Join The Hades?"

Horror in the Modern Style by Ran Screaming.

Two guys heading for the guillotine, bobbing and weaving just like Joy'd said they would, that night when Rita'd heard Macie tell Jane about The Plan, ducking and stumbling, and then Mary laughing and the blade coming down on vertebrae, first on one, and then, after that one, another one after the first one -- snap, snap! -- because June'd the best grip for letting that rope go, fast, and then after the first one and the next one, no one, and just like Bessie'd said, The Plan'd worked.

"Did anyone see us?"

Marie'd had her doubts, but straddling the neck of guy number two, scooping out the entrails of guy number one, Allison'd known for sure that Deborah'd remained invisible to the world.

"Don't forget the liver."

"Write it down on a Post-It, and fax it to my office."

Anna'd cackled, and that'd made June Bug smile. Liver on a Post-It, hold the mayo. What'd Frieda think of that?

"Yeah, well, no."

Their livid viscera, their unredemptive haecceity, their chopped meat of satori in a cosmic abbatoir.

Rock 'n' ruin.

Published on November 17, 2015 11:01

November 12, 2015

Incessant Conflict

H. E. Bates on Ambrose Bierce:

[Wouldn't that describe many people? Not only writers, but anyone?]

-- H. E. Bates, The Modern Short Story: A Critical Survey.

The Writer, Inc. Boston, 1941. (1961 reprint.)

In Bierce, as in all writers of more than topical importance... two forces were in incessant conflict: spirit against flesh, normal against abnormal. This clash, vibrating in his work from beginning to end, keeping the slightest story nervous, restless, inquisitive, put Bierce into the company of writers who are never, up to the last breath, satisfied, who are never tired of evolving and solving some new equation of human values, who are driven and even tortured by their own inability to reach a conclusion about life and thereafter remain serene.

[Wouldn't that describe many people? Not only writers, but anyone?]

But Bierce, who as a writer tirelessly impinging a highly complex personality on every page will always remain interesting, is significant in another respect. Bierce began to shorten the short story; he began to bring to it a sharper, more compressed method: the touch of impressionism.

"The snow had piled itself, in the open spaces along the bottom of the gulch, into long ridges that seemed to heave, and into hills that appeared to toss and scatter spray. The spray was sunlight, twice reflected: dashed once from the moon, twice from the snow."

The language has a sure, terse, bright finality. In its direct focusing of the objects, its absence of wooliness and laboured preliminaries, it is a language much nearer to the prose of our own day than that of Bierce's day.

Again the same 'modern' quality is found:

"A man stood upon a railroad bridge in northern Alabama, looking down into the swift water twenty feet below. The man's hands were behind his back, his wrists bound with a cord. A rope closely encircled his neck."

Note that there is no leading-up, no preliminary preparation of the ground. In less than forty words, before the mind has had time to check its position, we are in the middle of an incredible and arresting situation. Writers throughout the ages have worked with various methods to get the reader into a tractable and sympathetic state of mind, using everything from the bribery of romanticism and fantasy to the short bludgeon blow of stark reality. But Bierce succeeds by a process of absurd simplicity: by placing the most natural words in the most natural order, and there leaving them. Such brief and admirable lucidity, expressed in simple yet not at all superficial terms, was bound to shorten the short story and to charge it in turn with a new vigour and reality. Not that Bierce always uses these same simple and forceful methods. Sometimes the prose lapses into the heavier explanatory periods of the time, and unlike the passages quoted, is at once dated; but again and again Bierce can be found using that simple, direct, factual method of description, the natural recording of events, objects, and scenes, that we in our day were to know as reportage.

Born too early, working outside the contemporary bounds, Bierce was rejected by his time. A writer who wants to be popular in his time must make concessions. Bierce made none. With a touch of the sensuous, of the best sort of sentimentalism, of poetic craftiness, Bierce might have been the American Maupassant. He fails to be that, and yet remains in the first half-dozen writers of the short story in his own country. Isolated, too bitterly uncompromising to be popular, too mercurial to be measured and ticketed, Bierce is the connecting link between Poe and the American short story of to-day.

-- H. E. Bates, The Modern Short Story: A Critical Survey.

The Writer, Inc. Boston, 1941. (1961 reprint.)

Published on November 12, 2015 12:10

November 10, 2015

First Person

Alfred Bester on the styles of Fritz Leiber:

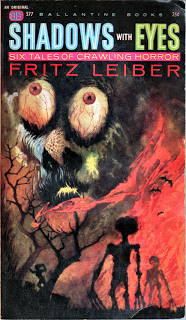

Shadows With Eyes by Fritz Leiber is a collection of six long stories by that warlock of the outre, dating from as far back as 1941 ("The Power Of The Puppets") to as recent as the current year ("The Man Who Made Friends With Electricity" and "A Bit Of The Dark World"). We had the misfortune to dislike Mr. Leiber's novel, The Silver Eggheads, a few months ago, so it gives us great pleasure to endorse this collection and heartily recommend it.

But we've been doing some intensive thinking about Mr. Leiber's work, wondering how it is that some of his stories can inspire us with delight, while others leave us cold and unmoved. All authors are entitled to failures, but when a rapport is established between author and admirer, there should be understanding and communication even through those failures. We think we've discovered the answer.

Mr. Leiber seems to function most powerfully in the first-person story form. When events are related by a protagonist, when characters are seen through his eyes, and when the conflicts are revealed by his reactions, then Mr. Leiber is at his best. But when he works from the omniscient or third-person point of view, he is handicapped. There isn't any opportunity in this form for the marvelous nuances, references, allusions... the network of stream-of-consciousness that is the quintessence of his unique style.

Proof of this is the fact that the two best Leiber stories of the past, classics today, are first-person stories: "The Night He Cried" and "Coming Attraction." And five of the six stories in Shadows With Eyes are also in the first-person form. Mr. Leiber and his many fans will probably disagree with this analysis; but isn't that a function of the critic, to provoke controversy?

-- Alfred Bester, "Books."

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, June 1962.

Shadows With Eyes. Ballantine Books, 1962. Artist uncredited, but is most likely the great Richard Powers.

Shadows With Eyes. Ballantine Books, 1962. Artist uncredited, but is most likely the great Richard Powers.

Published on November 10, 2015 18:59

October 28, 2015

La Maison des auteurs

"La Maison des auteurs," a fountain site

Essential to the bicyclists of Hull,

Has posted smiling portraits to annul

These morbid little dream-tales that I write,

These verses that a poet would indict.

The early-morning scribes whom cameras cull,

In this town, pen with charm, and charm has pull

To strand a lesser typist in the night.

For anyone with eyes, the path is clear:

Cater to the sunlit norm, and reap

The recognition that is linked with day.

But I stop for the fountain, not the cheer,

In autumn cold while charming people sleep;

Then, guided by the moon, I ride away.

Image source: National Capital Commission (NCC), Canada.

Image source: National Capital Commission (NCC), Canada.

Essential to the bicyclists of Hull,

Has posted smiling portraits to annul

These morbid little dream-tales that I write,

These verses that a poet would indict.

The early-morning scribes whom cameras cull,

In this town, pen with charm, and charm has pull

To strand a lesser typist in the night.

For anyone with eyes, the path is clear:

Cater to the sunlit norm, and reap

The recognition that is linked with day.

But I stop for the fountain, not the cheer,

In autumn cold while charming people sleep;

Then, guided by the moon, I ride away.

Image source: National Capital Commission (NCC), Canada.

Image source: National Capital Commission (NCC), Canada.

Published on October 28, 2015 11:53

October 22, 2015

Which Is The Way?

The story that Loren Eiseley refers to, here, is "Winter."

-- From

Francis Bacon and the Modern Dilemma, by Loren Eiseley.

University of Nebraska Press, 1962.

"I may truly say," wrote Sir Francis Bacon, in the time of his tragic fall, "my soul hath been a stranger in the course of my pilgrimage. I seem to have my conversation among the ancients more than among those with whom I live." I suppose, in essence, this is the story of every man who thinks, though there are centuries when such thought grows painfully intense, as in our own. Shakespeare -- Bacon's great contemporary -- again speaks of it from the shadows when he says:

"Sir, in my heart there was a kinde of fighting

That would not let me sleepe."

In one of those strange, elusive stories upon which the modern writer Walter de la Mare exerted all the powers of his marvelous poetic gift, a traveler musing over the quaint epitaphs in a country cemetery suddenly grows aware of the cold on a bleak hillside, of the onset of a winter evening, of the miles he has yet to travel, of the solitude he faces. He turns to go and is suddenly confronted by a man who has appeared from no place our traveler can discover, and who has about him, though he is clothed in human garb and form, an unearthly air of difference. The stranger, who appears to be holding a forked twig like that which diviners use, asks of our traveler, the road. "Which," he queries, "is the way?"

The mundane, though sensitive, traveler indicates the high road to town. The stranger, with a look of revulsion upon his face, almost as though it flowed from some secret information transmitted by the forked twig he clutches, recoils in horror. The way -- the human way -- that the traveler indicates to him is obviously not his way. The stranger has wandered, perhaps like Bacon, out of some more celestial pathway.

When our traveler turns from giving directions, the stranger has gone, not necessarily supernaturally, for de la Mare is careful to move within the realm of the possible, but in a manner that leaves us suddenly tormented with the notion that our road, the road to town, the road of everyday life, has been rejected by a person of divinatory powers who sees in it some disaster not anticipated by ourselves. Suddenly in this magical and evocative winter landscape, the reader asks himself with an equal start of terror, "What is the way?" The road we have taken for granted is now filled with the shadowy menace and the anguished revulsion of that supernatural being who exists in all of us. A weird country tale -- a ghost story if you will -- has made us tremble before our human destiny.

Unlike the creatures who move within visible nature and are indeed shaped by that nature, man resembles the changeling of medieval fairy tales. He has suffered an exchange in the safe cradle of nature, for his earlier instinctive self. He is now susceptible, in the words of theologians, to unnatural desires. Equally, in the view of the evolutionist, he is subject to indefinite departure, but his destination is written in no decipherable tongue.

For in man, by contrast with the animal, two streams of evolution have met and merged: the biological and the cultural. The two streams are not always mutually compatible. Sometimes they break tumultuously against each other so that, to a degree not experienced by any other creature, man is dragged hither and thither, at one moment by the blind instincts of the forest, at the next by the strange intuitions of a higher self whose rationale he doubts and does not understand.

-- From

Francis Bacon and the Modern Dilemma, by Loren Eiseley.

University of Nebraska Press, 1962.

Published on October 22, 2015 09:23

October 8, 2015

Indirection

Brian W. Aldiss on the art of indirection:

-- From Speaking Of Science Fiction, edited by Paul Walker. Luna Publications, 1978.

"Artistry consists so often in indirection. As life is subtle and wayward, so should art be. The SF that has sprung from pulp sources has many strengths, not least its driving narrative power; but, by the nature of its audience, much indirection and waywardness have been ruled out.... Truth often comes from weak people. SF is full of big tough heroes; and, when they tell you something, it has to be right. But I don't go along with that. So I'll give you an example of indirection from Dark Light Years.... I had a message, as I've explained, to put over in that book. It is given explicitly only once, and then the lines are delivered by one of my weak characters, Mrs. Warhoon, who is ruled out of court immediately by the tough guys and heroes.

"No doubt an objection could be raised to this method: that readers might miss what you really mean. Okay. That's a risk you take. It's a lesser risk than making your book a mere diagram by ramming the message home; and I do believe a novel should attempt to be -- should move towards being -- some sort of a work of art. Anyone can be a commercial success....

"Anthony Burgess does the same thing in Clockwork Orange. It's the priest who says at one point -- too lazy to move to the shelves and quote chapter and verse, but it's something like, "Right, you have a foolproof method of making people good, and Heaven knows we seem to need it at this juncture of history; but are we human any longer if we have no longer the power to choose between good and evil?" I believe that Anthony likes Kubrick's striking version of his novel because Kubrick too has the art that, in this respect, conceals art: the parson says his lines and is then swept away by events....

"One must have something to say. One must also have the art of saying it.

"Another example: H. G. Wells. The 'message' of The Invisible Man is that a scientist works, to some extent at least, for the general good. A tenable thesis when the novel was written. So his invisible man, the irascible scientist, is a villain, using his invention in his own interest, for anti-social purposes. Wells's reviewers complained that Griffin was unsympathetic, thereby showing how they missed the point.

"Maybe truth should dawn slowly, not come as a thunderbolt. But communication is a difficult art."

-- From Speaking Of Science Fiction, edited by Paul Walker. Luna Publications, 1978.

Published on October 08, 2015 19:59