Mark Fuller Dillon's Blog, page 29

October 23, 2017

The Blind Owl

(The Blind Owl is a difficult book to describe after only one reading, and Sadegh Hedayat's reputation would make such an idea seem foolish, but I've never been noted for wisdom.)

I had long considered J. G. Ballard's Crash the most obsessive book I've read, but The Blind Owl sinks even further down its own spiral. Like a gallery of mirrors in an echo chamber, the story presents the same phrases and fears and tableaux in a loop, yet offers each repetition as if it were an unexpected, unprecedented encounter. By referring back endlessly to the same places, actions, and hand gestures, it conveys the sense of one person stuck in his own head without escape. And this person is very much alone: everyone else in the story could almost be, and might very well be, a reflection or projection of his own diseased mind.

Unlike Crash, a relentlessly physical book, The Blind Owl prefers the metaphysical, with long passages of introspection detached from the wind or the rain or the sunlight:

Every now and then, the book rises from the fog of generalities to point at specific details, and I latched onto these moments with gratitude:

But then the book retreats again to its metaphysical corner:

For me, a story like this one thrives or dies on the quality of its prose. In its original Persian, The Blind Owl might be a masterpiece, but in D. P. Costello's translation, reading the book feels like tracing a finger through dust. Drifting and twisting in sunbeams, dust can fascinate, but here, the dust lies as heavy as the earth on a coffin.

For those who ponder dusty coffins, this book might gleam like a cemetery star. For me, it reveals the power and the weakness of repetition. For you, who knows? You have only one way to find out.

-- Sadegh Hedayat, The Blind Owl, translated by D. P. Costello.

John Calder, London, 1957.

I had long considered J. G. Ballard's Crash the most obsessive book I've read, but The Blind Owl sinks even further down its own spiral. Like a gallery of mirrors in an echo chamber, the story presents the same phrases and fears and tableaux in a loop, yet offers each repetition as if it were an unexpected, unprecedented encounter. By referring back endlessly to the same places, actions, and hand gestures, it conveys the sense of one person stuck in his own head without escape. And this person is very much alone: everyone else in the story could almost be, and might very well be, a reflection or projection of his own diseased mind.

Unlike Crash, a relentlessly physical book, The Blind Owl prefers the metaphysical, with long passages of introspection detached from the wind or the rain or the sunlight:

"Idle thoughts! Perhaps. Yet they torment me more savagely than any reality could do. Do not the rest of mankind who look like me, who appear to have the same needs and the same passions as I, exist only in order to cheat me? Are they not a mere handful of shadows which have come into existence only that they may mock and cheat me? Is not everything that I feel, see and think something entirely imaginary, something utterly different from reality?"

Every now and then, the book rises from the fog of generalities to point at specific details, and I latched onto these moments with gratitude:

"Lying in this damp, sweaty bed, as my eyelids grew heavy and I longed to surrender myself to nonbeing and everlasting night, I felt that my lost memories and forgotten fears were all coming to life again: fear lest the feathers in my pillow should turn into dagger blades or the buttons on my coat expand to the size of millstones; fear lest the bread-crumbs that fell to the floor should shatter into fragments like pieces of glass; apprehension lest the oil in the lamp should spill during my sleep and set fire to the whole city; anxiety lest the paws of the dog outside the butcher’s shop should ring like horses’ hoofs as they struck the ground; dread lest the old odds-and-ends man sitting behind his wares should burst into laughter and be unable to stop; fear lest the worms in the footbath by the tank in our courtyard should turn into Indian serpents; fear lest my bedclothes should turn into a hinged gravestone above me and the marble teeth should lock, preventing me from ever escaping; panic fear lest I should suddenly lose the faculty of speech and, however much I might try to call out, nobody should ever come to my aid...."

But then the book retreats again to its metaphysical corner:

"What life I had I have allowed to slip away -- I permitted it, I even wanted it, to go -- and after I have gone what do I care what happens? It is all the same to me whether anyone reads the scraps of paper I leave behind or whether they remain unread forever and a day. The only thing that makes me write is the need, the overmastering need, at this moment more urgent than ever it was in the past, to create a channel between my thoughts and my unsubstantial self, my shadow, that sinister shadow which at this moment is stretched across the wall in the light of the oil lamp in the attitude of one studying attentively and devouring each word I write. This shadow surely understands better than I do. It is only to him that I can talk properly. It is he who compels me to talk. Only he is capable of knowing me. He surely understands.... It is my wish, when I have poured the juice -- rather, the bitter wine -- of my life down the parched throat of my shadow, to say to him, 'This is my life'."

For me, a story like this one thrives or dies on the quality of its prose. In its original Persian, The Blind Owl might be a masterpiece, but in D. P. Costello's translation, reading the book feels like tracing a finger through dust. Drifting and twisting in sunbeams, dust can fascinate, but here, the dust lies as heavy as the earth on a coffin.

For those who ponder dusty coffins, this book might gleam like a cemetery star. For me, it reveals the power and the weakness of repetition. For you, who knows? You have only one way to find out.

-- Sadegh Hedayat, The Blind Owl, translated by D. P. Costello.

John Calder, London, 1957.

Published on October 23, 2017 08:33

October 16, 2017

Podolo....

"Transparent darkness covered the lagoon save for one shadow that stained the horizon black. Podolo...."

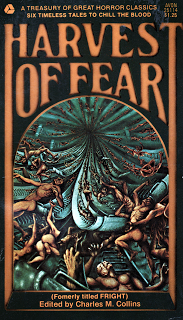

In 1981, thanks to a Charles M. Collins anthology, Harvest of Fear, "Podolo" was my introduction to L. P. Hartley.

This introduction had no impact, at first. I read the story in late autumn, wondered if I had missed the point, shrugged, and then moved on. Yet for some reason, "Podolo" nagged at me.

Just after sunset a few days later, as I stepped around the frozen puddles beside a long-abandoned, blackened farm house, and stared at the Gatineau Hills that loomed above me like black thunderheads, I thought about "Podolo" once again, and suddenly, for the first time, I felt the chill of that story. I suddenly realized just how frightening it was.

Reading it again tonight, thanks to the Valancourt ebook of The Travelling Grave , I was fascinated by how much foreshadowing appears in the first four paragraphs. Hartley gives away more than most writers would dare to -- certainly more than I would -- but this only testifies to his confidence. He knows that he has a great story, here, one that will nag at readers for decades to come, and catch them off guard when they poke through their own forsaken landscapes.

[Cover art by Helmut Wenske, 1975.]

Published on October 16, 2017 01:04

October 15, 2017

The Past Is A Foreign Country

Many writers understand that horror is not a genre, but a mood, a perspective, a state of mind. L. P. Hartley is one example, and his novel, The Go-Between, shows what this understanding can achieve.

What begins as an understated, everyday story of one man's attempt to recapture his memories becomes, almost imperceptibly, a sinister tale of people with concealed motives, of implications half-glimpsed and completely underestimated. As the plot develops, Hartley brings to this matter-of-fact account those elements that give his Travelling Grave stories their mood of unease: conversations that seem innocent or beside the point at first hearing, ordinary settings that begin to glow with dreamlike textures and shadows, a swelling intensity of awareness about some event looming just out of sight. The result is a story that twists and coils around itself until it reveals unexpected claws.

Like the Count in Walter de la Mare's "The Almond Tree," Leo Colston of The Go-Between immerses himself in childhood memories to the point where he perceives them as a child might, without understanding the adult context behind them, but unlike de la Mare, who uses that perspective to keep his readers in the dark, Hartley relies on the discrepancy between what Leo fails to understand, and what the readers understand all too well, for both dramatic irony and for sudden shocks of revelation. These build up to a climax that remains, for me, one of the more nightmarish I've read in a "down to earth" story, followed by an epilogue that combines bitter irony and moving sorrow in one beautifully dissonant final chord.

A mood, a perspective, a state of mind: Hartley knows the region, he knows where the swamps and pitfalls lie, he knows how to lead us quietly to the edge -- and how to push us over.

What begins as an understated, everyday story of one man's attempt to recapture his memories becomes, almost imperceptibly, a sinister tale of people with concealed motives, of implications half-glimpsed and completely underestimated. As the plot develops, Hartley brings to this matter-of-fact account those elements that give his Travelling Grave stories their mood of unease: conversations that seem innocent or beside the point at first hearing, ordinary settings that begin to glow with dreamlike textures and shadows, a swelling intensity of awareness about some event looming just out of sight. The result is a story that twists and coils around itself until it reveals unexpected claws.

Like the Count in Walter de la Mare's "The Almond Tree," Leo Colston of The Go-Between immerses himself in childhood memories to the point where he perceives them as a child might, without understanding the adult context behind them, but unlike de la Mare, who uses that perspective to keep his readers in the dark, Hartley relies on the discrepancy between what Leo fails to understand, and what the readers understand all too well, for both dramatic irony and for sudden shocks of revelation. These build up to a climax that remains, for me, one of the more nightmarish I've read in a "down to earth" story, followed by an epilogue that combines bitter irony and moving sorrow in one beautifully dissonant final chord.

A mood, a perspective, a state of mind: Hartley knows the region, he knows where the swamps and pitfalls lie, he knows how to lead us quietly to the edge -- and how to push us over.

Published on October 15, 2017 13:22

October 8, 2017

Packing Kernels

I've never been paid enough to do his editing for him....

In his books that I've read, he buried every passage that seemed evocative or funny within a crate of styrofoam packing kernels, and had I been given post office wages to sort through all of that squeaking and sliding, I might have considered the chore worthwhile. Selection is half the task of writing, and I leave that job to the writers.

-- My comments, elsewhere, on William S. Burroughs.

J. G. Ballard praised his work, and I respect Ballard's opinion. But as much as I love to read Ballard, I've never been able to work up anything more than a partial interest in Burroughs.

Published on October 08, 2017 19:47

October 6, 2017

Ordet

Ordet . What to make of this film?

Despite what I had read before I saw it, I never found Ordet slow -- certainly not when compared with late Tarkovsky, or even with Dreyer's earlier film, Day of Wrath .

Nor did I find the film especially "strange" in its technique. Theatrical, yes; much of it seemed like a filmed stage play, but not to the detriment of the story.

Instead, I found the film easily watchable, compelling, often funny. As the story went on, I began to care about the people, and by the midpoint, I found myself concerned for them.

But that ending, as beautifully directed as it was, felt unreal to me. While I had been moved earlier in the film, I suddenly found myself detached. While I had been drawn in before, I suddenly felt myself pushed away.

By any standards I can apply, from the experience of my own life to the methods used by other dramas, the final moments of Ordet are a lie, a deliberate lie, and a lie with cruel implications.

I can accept a film in which a sympathetic person dooms herself with a confession of witchcraft, because people in totalitarian societies often have internalized the accusations made against them. I can also accept a film that wants me to believe, while the story moves along, in vampires, because I have neither hope nor emotional investment in the reality of vampires.

But having watched my father die, having lost people I love, having known exactly how it feels to confront the reality and finality of death despite all of my hopes, I have to reject the final sequence of Ordet.

Or should I say, perhaps, that it rejected me?

Published on October 06, 2017 09:16

October 4, 2017

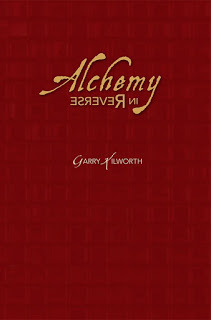

Alchemy In Reverse

Garry Kilworth loves nouns and names. He can show you fifteen terms for wind, various words for ships and boats, the songlike titles for the peals of church-bells, and yet, like the Spanish in his poem, "Cerro Gordo," he remains at heart a plain speaker:

"They call it like it is.

Not for them those fancy names:

Home-of-the-Gods or

Mountain-of-Greatness.

A fat hill is called Fat Hill."

He also loves the world. Animals and peoples, deserts and seas, the bustling smells of towns, the sweetness and acidities of foods, the cometary gleams of the Oort Cloud: these are all, for him, variations of home, and he writes as if he belonged in all such places and with all such people.

His memories call for attention, as in "Aden, 1953":

"Steamer Point with its liners

like sleek racehorses, waiting for the off,

and Khormaksar's black volcanic sands

with its dromedaries, simply waiting."

Or in "Singapore," during its days of rainforests and kampongs on stilts:

"I passed girls with oranges on their breath.

Girls in cheongsams with twilight eyes.

Girls with midnight hair and morning smiles.

Girls who looked back

at a young man."

Yet he also knows that places and people change with time, often in ways that defy understanding. He accepts all of this with clear eyes and wry humour, as in "Bathsheba":

"If you were caught bathing,

seen from a rooftop

in this century, in this decade,

soaping your breasts

in the moonlight

(though innocent of eyes)

there would be dozens, nay

thousands of Davids --

and Johns and Toms and Seans --

you'd be on YouTube

before the morning sun

dried your dripping towel...."

Objects and materials fascinate him, and so do living forms. He can show you the difference between a bolt-action 0.303 Lee-Enfield No. 4 Mk 2 rifle, and an AK47. He sees the "feral" beauty in Suffolk flint, the "willow-sprung" energy of hares, the "bladed shape" of a windhover that "shaves the sky." He can stand in the middle of the Southwold Sailor's Reading Room, "scarred and shabby... one part stillness, two parts time," and not only pick up the details around him, but perceive beyond them to a way of life:

"Days of fire and freezing rain,

nights when winds drove sharp and deep.

They brawled with squalls and screaming gales,

battled with unyielding seas,

drowned."

What he offers, then, is a quiet, accepting book from a man at war neither with himself nor with life; a gentle book of observations and memories from someone lost in the world yet happy to be lost:

"Do not look for me:

I do not want to be found."

Published on October 04, 2017 15:09

September 29, 2017

Borrowed Light

Foaming gall. High disdain. Borrowed light.

When handled with imagination or precision or a touch of the unexpected, adjectives can lose their sting.

-- Marlowe, Tamburlaine the Great, Part the First.

When handled with imagination or precision or a touch of the unexpected, adjectives can lose their sting.

MYCETES:

Then hear thy charge, valiant Theridamas,

The chiefest captain of Mycetes' host,

The hope of Persia, and the very legs

Whereon our state doth lean as on a staff,

That holds us up and foils our neighbour foes:

Thou shalt be leader of this thousand horse,

Whose foaming gall with rage and high disdain

Have sworn the death of wicked Tamburlaine.

Go frowning forth; but come thou smiling home,

As did Sir Paris with the Grecian dame:

Return with speed; time passeth swift away;

Our life is frail, and we may die to-day.

THERIDAMAS:

Before the moon renew her borrow'd light,

Doubt not, my lord and gracious sovereign,

But Tamburlaine and that Tartarian rout

Shall either perish by our warlike hands,

Or plead for mercy at your highness' feet.

MYCETES:

Go, stout Theridamas; thy words are swords,

And with thy looks thou conquerest all thy foes.

I long to see thee back return from thence,

That I may view these milk-white steeds of mine

All loaden with the heads of killèd men,

And from their knees e'en to their hoofs below,

Besmear'd with blood that makes a dainty show.

-- Marlowe, Tamburlaine the Great, Part the First.

Published on September 29, 2017 16:40

August 11, 2017

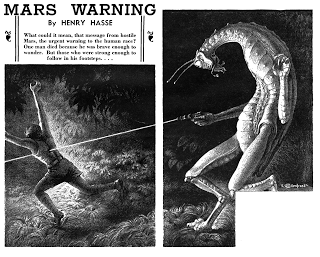

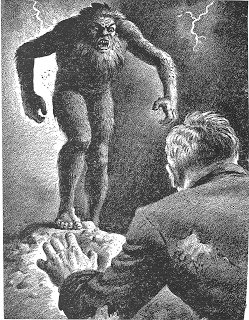

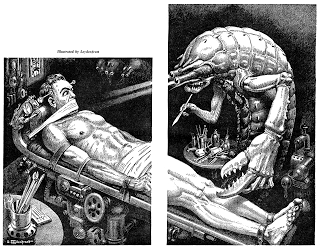

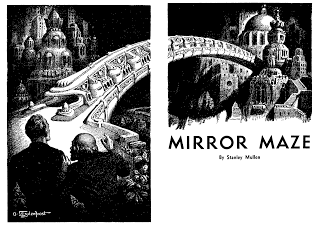

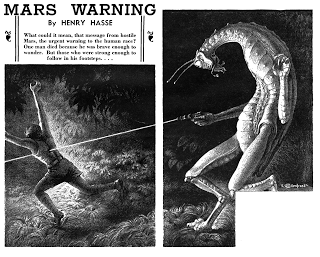

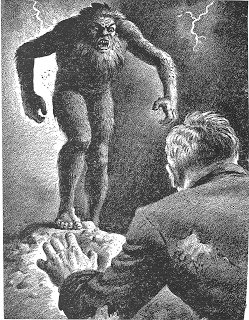

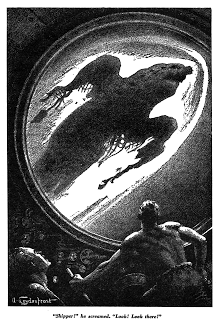

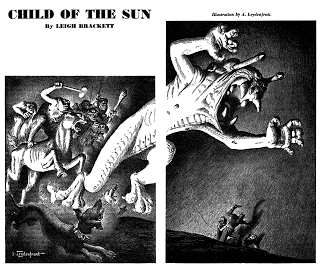

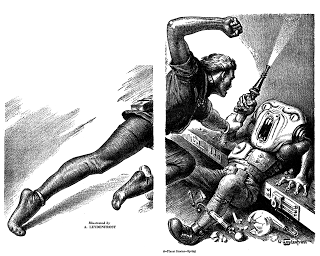

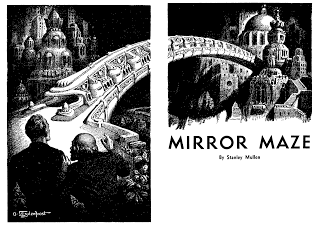

Illustrations by Alexander Leydenfrost

[To download these images in their original size, please go

here

.]

Often in the pulps, the skill and imagination of the illustrators far outclassed the abilities of the writers, and this was particularly true for Alexander Leydenfrost.

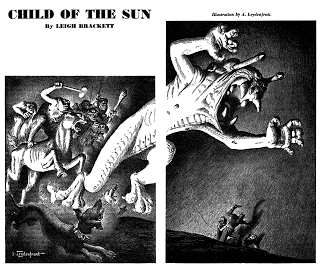

(But not in the case of Leigh Brackett. Her skills, and his, were more evenly matched.)

Super Science Stories, August 1942.

Super Science Stories, August 1942.

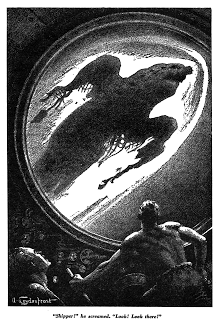

"No Man's Land, by John Buchan. Famous Fantastic Mysteries, December 1949.

"No Man's Land, by John Buchan. Famous Fantastic Mysteries, December 1949.

Planet Stories, Winter 1942.

Planet Stories, Winter 1942.

Planet Stories, Summer 1942.

Planet Stories, Summer 1942.

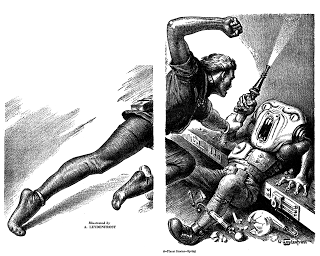

Planet Stories, Spring 1942.

Planet Stories, Spring 1942.

Planet Stories, Spring 1942.

Planet Stories, Spring 1942.

Famous Fantastic Mysteries, June 1949: a story with nothing to offer, but that would never stop Leydenfrost.

Famous Fantastic Mysteries, June 1949: a story with nothing to offer, but that would never stop Leydenfrost.

Often in the pulps, the skill and imagination of the illustrators far outclassed the abilities of the writers, and this was particularly true for Alexander Leydenfrost.

(But not in the case of Leigh Brackett. Her skills, and his, were more evenly matched.)

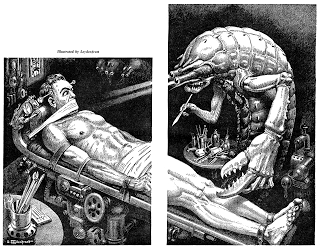

Leydenfrost studied at the Royal Academy of Fine and Applied Arts of Budapest. In 1919, he was appointed as a professor of perspective and applied art at the Royal Technological University, also in Budapest. The term 'applied arts' is now known as 'industrial design'. As a professor with his summers free, the Baron traveled throughout Europe. According to family, he considered it quite a challenge to see the most of Europe on the least amount of money. His plan involved traveling from monastery to monastery as a guest of the monks. An added benefit of his stays with the monks was his having great works of art and literature at his disposal. These visits were no doubt quite influential on his artistic style.

In 1923, Middle European financial and ethical collapse forced Sandor and three close friends, Peter Lorre, Bela Lugosi, and Paul Lucas, to immigrate to America. Reportedly known as the 4 "Ls", the friends found themselves in New York City. Leydenfrost's exodus, however, was further complicated by circumstance. Like any young male of noble European birth, Leydenfrost was trained in the art of fencing. In Europe at the time it was commonplace to defend a woman's honor in a duel. Just before the time of his immigration Leydenfrost suffered from numerous wounds received from such practice. Upon arriving in New York, these wounds forced him to remain in bed.

Still able to draw and paint while bed-ridden, he had his three friends who took his portfolio around town to secure work. The four of them were able to live comfortably off of the Baron's commissions until his wounds healed. [From Tina Saint-Paul, granddaughter of the artist.]

Super Science Stories, August 1942.

Super Science Stories, August 1942. "No Man's Land, by John Buchan. Famous Fantastic Mysteries, December 1949.

"No Man's Land, by John Buchan. Famous Fantastic Mysteries, December 1949. Planet Stories, Winter 1942.

Planet Stories, Winter 1942. Planet Stories, Summer 1942.

Planet Stories, Summer 1942. Planet Stories, Spring 1942.

Planet Stories, Spring 1942. Planet Stories, Spring 1942.

Planet Stories, Spring 1942. Famous Fantastic Mysteries, June 1949: a story with nothing to offer, but that would never stop Leydenfrost.

Famous Fantastic Mysteries, June 1949: a story with nothing to offer, but that would never stop Leydenfrost.

Published on August 11, 2017 01:23

July 16, 2017

Papillons noirs

How to translate badly, lesson one: Make the translation rhyme.

I've begun to think that any real aesthetic appreciation of a translated poem would have to be found by reading the original, and that all I can do is to give a rough, incomplete idea of what the poem says -- necessarily incomplete, because poems depend more on the skilled use of language than on meaning as we think of it when we talk about other forms of communication. If I were to impose a rhyme scheme, I would cloud this already vague idea.

With all of this in mind, here is my rough translation of another poem by Albert Giraud, from Pierrot Lunaire: Rondels Bergamasques (Alphonse Lemerre, Éditeur. Paris, 1884).

How could this go wrong? Easily!

Perhaps, like a physician, a translator should first do no harm....

I've begun to think that any real aesthetic appreciation of a translated poem would have to be found by reading the original, and that all I can do is to give a rough, incomplete idea of what the poem says -- necessarily incomplete, because poems depend more on the skilled use of language than on meaning as we think of it when we talk about other forms of communication. If I were to impose a rhyme scheme, I would cloud this already vague idea.

With all of this in mind, here is my rough translation of another poem by Albert Giraud, from Pierrot Lunaire: Rondels Bergamasques (Alphonse Lemerre, Éditeur. Paris, 1884).

PAPILLONS NOIRS.

De sinistres papillons noirs

Du soleil ont éteint la gloire,

Et l'horizon semble un grimoire

Barbouillé d'encre tous les soirs.

Il sort d'occultes encensoirs

Un parfum troublant la mémoire:

De sinistres papillons noirs

Du soleil ont éteint la gloire.

Des monstres aux gluants suçoirs

Recherchent du sang pour le boire,

Et du ciel, en poussière noire,

Descendent sur nos désespoirs

De sinistres papillons noirs.

- - - - - - - - - -

Sinister black butterflies

Have extinguished the glory of the sun,

And the horizon resembles a grimoire

Smeared with ink every night.

There issues from occult censers

A perfume troubling to the memory:

Sinister black butterflies

Have extinguished the glory of the sun.

Monsters with sticky proboscides

Hunt for blood to drink,

And from the sky, in black dust,

Upon our despairs descend

Sinister black butterflies.

How could this go wrong? Easily!

Sinister black butterflies

Have snuffed out glory from the skies;

Like some grimoire, the horizon lies

Daubed with ink at midnight's rise.

From censers used for auguries,

Fumes coil to pierce forgotten sighs:

Sinister black butterflies

Have snuffed out glory from the skies.

Slimey beast proboscides

Hunt for blood-atrocities,

While from the clouds like blackened sties

Descend on every dream that dies

Sinister black butterflies.

Perhaps, like a physician, a translator should first do no harm....

Published on July 16, 2017 15:21

July 9, 2017

A Reviewer's Duty to Damn

John Ciardi, on principles for reviewers at The Saturday Review.

-- From

"A Reviewer's Duty to Damn."

The Saturday Review, February 16, 1957.

1. The reader deserves an honest opinion. If he doesn't deserve it give it to him anyhow.

2. No one who offers a book for sale is sacrosanct. By the act of publication and promotion, the citizen-human being forfeits his privileges as a non-competitor. Having willingly subjected himself to judgment he must accept either blame or praise as it follows. If in doubt, assume that the book is signed by Anonymous.

3. Evaluation must be by stated principle. The reviewer's opinion is only as good as his methods.

4. A review without reference to the text is worthless.

5. Quotation without analysis of the material quoted is suspect.

6. If you cannot document a charge, pro or con, do not make it.

7. Poetry is more important than any one poet. Serve poetry.

8. Limitations of space often make it difficult and sometimes impossible to apply these principles as carefully as one would wish. No space limitation, however, is reason enough for forgetting that these principles exist.

-- From

"A Reviewer's Duty to Damn."

The Saturday Review, February 16, 1957.

Published on July 09, 2017 17:16