Mark Fuller Dillon's Blog, page 26

October 13, 2018

Something Dead That Struggled Into Life

I left early the next morning, walked up the road that climbed the hillside, and followed the winding route below the mountain. The day was milder, but the oblique sunlight, the woodsmoke tang of rotten leaves, brought hints of winter's approach, and the wind stung my healing face.

When I came to the spot where I had found myself the day before, I was tempted to return home. The wind in the pines hissed like a tide retreating on a hidden shore, and the scuttling of the leaves on the dirt road made me think of something dead that struggled into life. A lingering, indefinable dread had seeped through my mind and it darkened everything around me.

The few farmhouses along the route were boarded up and empty. Staghorn sumac and hawthorns had spread across the fields; grey stalks of burdock and milkweed bristled on ragged lawns. I remembered how, as a child, I could see the sparse lights from distant farms at nightfall, or hear the faint barking of a neighbour's dog; these nights, the fields and hills were black, and the silence gave way only to the baying of the wolves.

On the far side of the mountain, the driveway to the Rexdales weaved through a forest of gaunt maples and cedars until it reached the house, a white, one-storey building with a broad bay window that faced a long and narrow clearing. The surrounding woods were bleak: the scarlets and the orange-reds had faded to a dull copper, and the shimmering yellows of the aspen trees were spectral in the slanting light. Yet thanks to my maintenance work, the house felt unabandoned -- an illusion that died as I peered through the bay window at the empty living room.

I studied the house, hoping to spur recollection, but nothing came to me. The western sky, pale blue with a streak of cirrus, brought nothing to mind, even as I waited at the exact spot where I had seen my shadow leap upon the wall the night before. There was nothing here to frighten anyone.

As a child, I had played here many times with the Rexdale children. I remembered hide and seek, with the sheds and the encroaching woods as perfect spots to watch pursuers without being seen. But our favorite hiding place was the cubbyhole below the bay window, with a sliding panel built into the living room wall. If you lay down you could slide right in and close the panel until only your eyes were visible.

And then the shadows on the wall --

What?

As the shadow of a driven cloud darkens the fields and then fades away, something had loomed within my memory and passed me by.

I closed my eyes to the pale sunlight and tried to see the darkness of the night before.

Shadows.

Shadows on a wall.

I felt a sudden chill, the physiological memory of fear. I touched my face and, prompted by a vague impulse, ran my fingers over the irritable skin. They brought to mind the fronds of a plant brushing against me, the sliding touch of wet rope.

Yes... wet rope.

From "Shadows In The Sunrise."

Published on October 13, 2018 16:15

September 18, 2018

But Doctor, It Only Hurts When I Type

WRITING (Not to be mistaken for WRITHING):

The process by which you fork your guts and heart into a tiny box, then hold out this dripping mess for the painfully-needed approval of people you will never meet or know.

See also: HEROIN ADDICTION.

Published on September 18, 2018 10:16

September 12, 2018

From the Distant Iridescence

For N. P.

From the distant iridescence of my memory,

Faces glow, then fade as lives are lost;

Asters with a hue of dusk return to me,

The cedared Wakefield hillsides gleam with frost.

In the distant iridescence of my memory,

Two falling stars burned pathways that we crossed.

Published on September 12, 2018 09:02

September 1, 2018

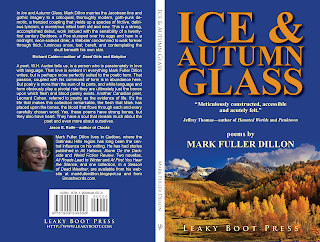

Ice & Autumn Glass

Reviews have been creeping in for my latest book, and I could not have asked for better praise. Thank you, everyone!

Published on September 01, 2018 14:36

August 25, 2018

Not Always Inward, And Not Often Secret

"There was never proud man thought so absurdly well of himself as the lover doth of the person loved; and therefore it was well said, That it is impossible to love and to be wise. Neither doth this weakness appear to others only, and not to the party loved; but to the loved most of all, except the love be reciproque. For it is a true rule, that love is ever rewarded either with the reciproque or with an inward and secret contempt."

-- From "Of Love," in Selected Writings of Francis Bacon. The Modern Library, New York, 1955.

Published on August 25, 2018 06:14

August 14, 2018

By A Dark Light

"It hath been an opinion, that the French are wiser than they seem, and the Spaniards seem wiser than they are. But howsoever it be between nations, certainly it is so between man and man. For as the Apostle saith of godliness, Having a shew of godliness, but denying the power thereof; so certainly there are in point of wisdom and sufficiency, that do nothing or little very solemnly: magno conatu nugas [trifles achieved by great effort]. It is a ridiculous thing and fit for a satire to persons of judgment, to see what shifts these formalists have, and what prospectives to make superficies to seem body that hath depth and bulk. Some are so close and reserved, as they will not shew their wares but by a dark light; and seem always to keep back somewhat; and when they know within themselves they speak of that they do not well know, would nevertheless seem to others to know of that which they may not well speak. Some help themselves with countenance and gesture, and are wise by signs; as Cicero saith of Piso, that when he answered him, he fetched one of his brows up to his forehead, and bent the other down to his chin; Respondes, altero ad frontem sublato, altero ad mentum depresso supercilio, crudelitatem tibi non placere [You answer, with one brow raised to your forehead and the other dropped to your chin, that cruelty does not please you]. Some think to bear it by speaking a great word, and being peremptory; and go on, and take by admittance that which they cannot make good. Some, whatsoever is beyond their reach, will seem to despise or make light of it as impertinent or curious; and so would have their ignorance seem judgment."

-- From "Of Seeming Wise," in Selected Writings Of Francis Bacon. The Modern Library, New York, 1955.

Published on August 14, 2018 16:16

July 31, 2018

A Torch Borne in the Wind

George Chapman reveals, once again, that magnificent speeches alone cannot make a magnificent play.

After my second reading of his most famous work, The Tragedy of Bussy d'Ambois, I would never deny that he could write brilliantly:

Yet Chapman, for all of his verbal energy, seemed unable to bring his people to life.

In Specimens Of English Dramatic Poets Who Lived About the Time Of Shakespeare, Charles Lamb wrote of Chapman, "Dramatic imitation was not his talent. He could not go out of himself, as Shakespeare could shift at pleasure, to inform and animate other existences."

I can see this at work in the play, where every character sounds exactly the same, where people step onstage to speak one line in one scene, and are then killed offstage in the next, and where the motivations that become clear in the characters of Shakespeare, Webster, and Ford, can be difficult to find in the disembodied voices here. These characters are not even the colourful puppets of The Revenger's Tragedy; they are words on a page that burst off in unison like one authorial storm.

The storm can be lively and vivid:

These passages of lightning are often followed by a rain of mud, in lines uttered by characters whose shifts in personality and purpose make no sense to me. As a result, I wobble between staring-eyed respect and baffled frustration. I want to enjoy this play, but the mud is thick.

[The lines of the play are from Bussy d'Ambois, A Mermaid Dramabook, Hill and Wang, New York, 1966.]

After my second reading of his most famous work, The Tragedy of Bussy d'Ambois, I would never deny that he could write brilliantly:

Man is a torch borne in the wind; a dream

But of a shadow, summed with all his substance;

And as great seamen, using all their powers

And skills in Neptune's deep invisible paths,

In tall ships richly built and ribbed with brass,

To put a girdle round about the world;

When they have done it, coming near their haven,

Are glad to give a warning-piece, and call

A poor staid fisherman, that never passed

His country's sight, to waft and guide them in;

So when we wander furthest through the waves

Of glassy Glory and the gulfs of State,

Topt with all titles, spreading all our reaches,

As if each private arm would sphere the world,

We must to Virtue for her guide resort,

Or we shall shipwrack in our safest port.

Yet Chapman, for all of his verbal energy, seemed unable to bring his people to life.

In Specimens Of English Dramatic Poets Who Lived About the Time Of Shakespeare, Charles Lamb wrote of Chapman, "Dramatic imitation was not his talent. He could not go out of himself, as Shakespeare could shift at pleasure, to inform and animate other existences."

I can see this at work in the play, where every character sounds exactly the same, where people step onstage to speak one line in one scene, and are then killed offstage in the next, and where the motivations that become clear in the characters of Shakespeare, Webster, and Ford, can be difficult to find in the disembodied voices here. These characters are not even the colourful puppets of The Revenger's Tragedy; they are words on a page that burst off in unison like one authorial storm.

The storm can be lively and vivid:

HENRY:

This desperate quarrel sprung out of their envies

To D'Ambois' sudden bravery, and great spirit.

GUISE:

Neither is worth their envy.

HENRY:

Less than either

Will make the gall of Envy overflow;

She feeds on outcast entrails like a kite;

In which foul heap, if any ill lies hid,

She sticks her beak into it, shakes it up,

And hurls it all abroad, that all may view it.

Corruption is her nutriment; but touch her

With any precious ointment, and you kill her:

When she finds any filth in men, she feasts,

And with her black throat bruits it through the world

Being sound and healthful; but if she but taste

The slenderest pittance of commended virtue,

She surfeits of it, and is like a fly

That passes all the body’s soundest parts,

And dwells upon the sores; or if her squint eye

Have power to find none there, she forges some.

She makes that crooked ever which is strait;

Calls valour giddiness, justice tyranny;

A wise man may shun her, she not herself:

Whithersoever she flies from her harms,

She bears her foe still clasped in her own arms;

And therefore, Cousin Guise, let us avoid her.

These passages of lightning are often followed by a rain of mud, in lines uttered by characters whose shifts in personality and purpose make no sense to me. As a result, I wobble between staring-eyed respect and baffled frustration. I want to enjoy this play, but the mud is thick.

[The lines of the play are from Bussy d'Ambois, A Mermaid Dramabook, Hill and Wang, New York, 1966.]

Published on July 31, 2018 12:48

July 22, 2018

Jason E. Rolfe Clocks In

From 2014, Jason E. Rolfe's

An Inconvenient Corpse

was the funniest book I had read in years. Now, in

Clocks

, it has a rival.

Sometimes, a good book that I recommend thoroughly can be hard to review; this one, for example. In the same way that a joke or a poem cannot be summarized, the stories in Clocks can only be experienced. As tempted as I might be to post entire stories in this review, I can only quote from sections.

Jason E. Rolfe has a passion for absurdist fiction, an encyclopedic knowledge of its writers. Without such a compass, I can only compare his work to John Sladek's, to R. A. Lafferty's, to the fables of Ambrose Bierce or Robert Louis Stevenson. If Stevenson's "The Sinking Ship" makes you laugh, then Clocks will do the same.

Among the many joys of the book are the tributes paid to Rolfe's favourite people, from Buster Keaton and Samuel Beckett to Daniil Kharms and Kurt Russell in The Thing. They show up and perform along with condescending couches, blue whales, Flat Earthers and Hollow Earthers (who cannot get along), Russian writers lost in America, Canadian writers lost in Canada, Mexican pinatas and kidney stones that seriously get in the way of things.

There are moments of melancholy, observations of life's regrets, hopes eroded, but looming over the entire book is the humour that made An Inconvenient Corpse a constant pleasure.

The corpse is gone; the clocks are here. Grab this book, and uncover one of Canada's best kept secrets: the bleakly joyous, laughing world of Jason E. Rolfe.

I passed a younger version of myself on the way to work this morning. I was eleven years old.

"Wow," I said.

"I wish I was more self-confident back then," I replied.

"I wish I turned out differently."

"I had such low self-esteem."

"And I had such high hopes."

I went to work feeling absolutely miserable, but I went to school feeling even worse.

Sometimes, a good book that I recommend thoroughly can be hard to review; this one, for example. In the same way that a joke or a poem cannot be summarized, the stories in Clocks can only be experienced. As tempted as I might be to post entire stories in this review, I can only quote from sections.

I wouldn’t say I was a nihilist; it’s just that I thought the world was meaningless and our lives were utterly pointless.

Jason E. Rolfe has a passion for absurdist fiction, an encyclopedic knowledge of its writers. Without such a compass, I can only compare his work to John Sladek's, to R. A. Lafferty's, to the fables of Ambrose Bierce or Robert Louis Stevenson. If Stevenson's "The Sinking Ship" makes you laugh, then Clocks will do the same.

"Who the hell are you?" Jules Verne demanded.

We all turned toward the Frenchman, who’d somehow appeared in the tunnel beside us.

"Zhang Heng," Zhang Heng said.

"Edmund Halley," Edmund Halley said.

"Jason Rolfe," I said.

"Two of you are famous enough to be familiar to me," Jules Verne said. "But you sir," he said to Edmund Halley. "I’ve never heard of you before in all my life."

Among the many joys of the book are the tributes paid to Rolfe's favourite people, from Buster Keaton and Samuel Beckett to Daniil Kharms and Kurt Russell in The Thing. They show up and perform along with condescending couches, blue whales, Flat Earthers and Hollow Earthers (who cannot get along), Russian writers lost in America, Canadian writers lost in Canada, Mexican pinatas and kidney stones that seriously get in the way of things.

I lost my mind this morning. I’m frustrated because I always leave it in the old wooden bowl by the door. The second I step in the house I drop my wallet, my car keys, my watch and my mind in that bowl. I always do, because if I don’t I’m bound to lose them. It’s become such a habit that on those rare occasions when I do forget, I assume that’s where they are, which makes it even harder to remember where I’ve actually left them. Once, for example, I found my car keys in the freezer, my watch in the clothes hamper, my wallet in the lint trap on our dryer and my mind beneath the cushions of our comfy basement couch. It should go without saying that I haven’t searched any of those places today. Having lost my mind I’m not exactly thinking straight.

There are moments of melancholy, observations of life's regrets, hopes eroded, but looming over the entire book is the humour that made An Inconvenient Corpse a constant pleasure.

The corpse is gone; the clocks are here. Grab this book, and uncover one of Canada's best kept secrets: the bleakly joyous, laughing world of Jason E. Rolfe.

Published on July 22, 2018 18:12

July 20, 2018

My Repellent Book

"A repellent book."

That was the assessment of kindly Dr. Joynt, the dentist of my childhood, who appeared at a crowded party in one of last night's dreams to let me know, with a reluctant sneer, exactly what he thought of Ice & Autumn Glass . His opinion is echoed in the silence of other people, as you can see from the reviews on this Goodreads page.

But dream-dentists and silent people offer less feedback than living readers; their opinions are the ones that count for me. Does the book repel dentists only, and only in dreams? I have one way to find out. Let me know!

Now spit, please.

That was the assessment of kindly Dr. Joynt, the dentist of my childhood, who appeared at a crowded party in one of last night's dreams to let me know, with a reluctant sneer, exactly what he thought of Ice & Autumn Glass . His opinion is echoed in the silence of other people, as you can see from the reviews on this Goodreads page.

But dream-dentists and silent people offer less feedback than living readers; their opinions are the ones that count for me. Does the book repel dentists only, and only in dreams? I have one way to find out. Let me know!

Now spit, please.

Published on July 20, 2018 09:35

July 15, 2018

The Outer Limits of Joseph Stefano

One of the many fascinations of

The Outer Limits

is the writing of Joseph Stefano, which coiled and twisted into darker forms as the series progressed.

"A Feasibility Study," an early script, celebrates the power of human solidarity and self-sacrifice in a way that never fails to make me cry, yet it remains, at heart, conventional science fiction, in which people with clear motives confront aliens with motives equally clear, in a universe that can be understood. For all of its emotional power, it could (with a bit of squinting) be taken for one of the murkier episodes of The Twilight Zone, where it would have fit in badly, but still might have been able to pass for normal.

As he continued to write for The Outer Limits, Joseph Stefano began to shift beyond conventional science fiction into something more troubled and troubling.

In "The Zanti Misfits," "Fun and Games," "The Bellero Shield," "The Invisibles," and "Nightmare," the universe, no matter how bizarre, remains knowable: it can be studied and its aliens can be understood. The difference now is that human beings themselves are mysterious. Paralyzed by existential doubts, crippled by psychological deformations, unable to meet the challenges of life and growth, of love and solidarity, many of the characters here seem a universe unto themselves. They try their best to explain their mental twists and turns, but their explanations are often as opaque as their motives.

Finally, we have episodes that seem to be less about troubled people than about a troubled writer.

"Don't Open Till Doomsday," "It Crawled Out of the Woodwork," and "The Forms of Things Unknown" are no longer conventional science fiction; I would go further, and say that these are no longer conventional drama. In a universe that now cannot be understood, peopled with aliens and humans whose motives are obscured by psychological shadows, the stories themselves make very little sense; they seem, instead, like fever dreams, like undeciphered signals from the subconscious mind.

This is not a complaint. I respect these episodes even as they baffle me, in the way that I respect the films of Lynch and Bergman, and I can only marvel that dreams as bizarre and as personal as Joseph Stefano's could squeeze their way onto American TV sets, even at the risk of network interference -- an interference that came to pass, that killed the show as it had been up to that point, and that removed any further risk of undeciphered signals.

"A Feasibility Study," an early script, celebrates the power of human solidarity and self-sacrifice in a way that never fails to make me cry, yet it remains, at heart, conventional science fiction, in which people with clear motives confront aliens with motives equally clear, in a universe that can be understood. For all of its emotional power, it could (with a bit of squinting) be taken for one of the murkier episodes of The Twilight Zone, where it would have fit in badly, but still might have been able to pass for normal.

As he continued to write for The Outer Limits, Joseph Stefano began to shift beyond conventional science fiction into something more troubled and troubling.

In "The Zanti Misfits," "Fun and Games," "The Bellero Shield," "The Invisibles," and "Nightmare," the universe, no matter how bizarre, remains knowable: it can be studied and its aliens can be understood. The difference now is that human beings themselves are mysterious. Paralyzed by existential doubts, crippled by psychological deformations, unable to meet the challenges of life and growth, of love and solidarity, many of the characters here seem a universe unto themselves. They try their best to explain their mental twists and turns, but their explanations are often as opaque as their motives.

Finally, we have episodes that seem to be less about troubled people than about a troubled writer.

"Don't Open Till Doomsday," "It Crawled Out of the Woodwork," and "The Forms of Things Unknown" are no longer conventional science fiction; I would go further, and say that these are no longer conventional drama. In a universe that now cannot be understood, peopled with aliens and humans whose motives are obscured by psychological shadows, the stories themselves make very little sense; they seem, instead, like fever dreams, like undeciphered signals from the subconscious mind.

This is not a complaint. I respect these episodes even as they baffle me, in the way that I respect the films of Lynch and Bergman, and I can only marvel that dreams as bizarre and as personal as Joseph Stefano's could squeeze their way onto American TV sets, even at the risk of network interference -- an interference that came to pass, that killed the show as it had been up to that point, and that removed any further risk of undeciphered signals.

Published on July 15, 2018 09:09