Mark Fuller Dillon's Blog, page 24

May 2, 2019

Ford Madox Ford on Impressionism

"The passage in prose which I always take as a working model... occurs in a story by de Maupassant called 'La Reine Hortense.' I spent, I suppose, a great part of ten years in grubbing up facts about Henry VIII. I worried about his parentage, his diseases, the size of his shoes, the price he gave for kitchen implements, his relation to his wives, his knowledge of music, his proficiency with the bow. I amassed, in short, a great deal of information about Henry VIII... I then wrote three long novels all about that Defender of the Faith. But I really know -- so delusive are reported facts -- nothing whatever. Not one single thing! Should I have found him affable, or terrifying, or seductive, or royal, or courageous? There are so many contradictory facts; there are so many reported interviews, each contradicting the other, so that really all that I know about this king could be reported in the words of Maupassant, which, as I say, I always consider as a working model. Maupassant is introducing one of his characters, who is possibly gross, commercial, overbearing, insolent; who eats, possibly, too much greasy food; who wears commonplace clothes -- a gentleman about whom you might write volumes if you wanted to give the facts of his existence. But all that de Maupassant finds it necessary to say is: 'C'était un monsieur à favoris rouges qui entrait toujours le premier.'

"And that is all that I know about Henry VIII -- that he was a gentleman with red whiskers who always went first through a door."

-- From

"On Impressionism," by Ford Madox Hueffer.

In POETRY AND DRAMA Volume II, edited by Harold Munro. The Poetry Bookshop, London, 1914.

Published on May 02, 2019 05:17

Stifled By The Darkness

Because I think of WILD STRAWBERRIES as one of Bergman's most positive and life-affirming movies, I chose it as a doorway to introduce his work to my last girlfriend. She hated the film, called it "too dark," and could not be persuaded to watch anything else by Bergman.

I have to concede that the film's warm, serene ending comes at the cost of great struggle by the characters. Anxieties, bleak memories, losses, nightmares: all of these are pitfalls on the way to reconciliation and peace, so much so that any viewer coming into the story halfway through could easily mistake this for a horror film.

What is horror: a result, or a process?

Many stories and films deal with a process of horror, but reach a happy ending -- a well-deserved, painfully-gained sense of closure in the daylight. I would never suggest that such films are less fascinating or beautiful than films that result in horror. BLUE VELVET, INLAND EMPIRE, ORPHÉE, VALERIE AND HER WEEK OF WONDERS, VAMPYR, CURSE OF THE CAT PEOPLE, THE SPIRIT OF THE BEEHIVE, THE QUEEN OF SPADES: these end in daylight or in peace, but I still consider them great films that would appeal to horror viewers.

On the other hand, I think of horror as a result, as a mood that remains and overwhelms a story. My favourite horror films leave me in the dark: DAY OF WRATH, DEAD OF NIGHT, SECONDS, LES YEUX SANS VISAGE, PSYCHO, THE BIRDS, THE INNOCENTS, L'ANNÉ DERNIÈRE À MARIENBAD, SOLARIS, IVAN'S CHILDHOOD, THE BODY SNATCHER, LEMORA.

Many of Bergman's films also lead into darkness: WINTER LIGHT, SHAME, HOUR OF THE WOLF, PERSONA, THE SERPENT'S EGG. Other films are equally horrific, but end with a hard-won mood of hope: THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY, WILD STRAWBERRIES, and perhaps even THE SILENCE.

As my last girlfriend made clear to me, for some people, a happy result might not cancel out an unhappy process. For them, a story might end in daylight, but their memories of that experience are stifled by the darkness.

Published on May 02, 2019 04:04

Broken-Back Sentences

How to write badly with broken-back sentences: take a weak verb, add a present participle afterthought. Repeat until the reader pukes.

Examples from "Sandkings," by George R. R. Martin.

- - - - - - - - -

Examples from "Sandkings," by George R. R. Martin.

- - - - - - - - -

The reds were the most creative, using tiny flakes of slate to put the gray in his hair.

The small scarlet mobiles were frozen, watching.

The lines closed around it, covered it, waging desperate battle.

He stopped at her table briefly and told her about the war games, inviting her to join them.

He waved it back and forth, smashing towers and ramparts and walls.

Sand and stone collapsed, burying the scrambling mobiles.

He watched for a moment, wondering whether he’d killed the maw.

“Easy,” he said, holding his head.

The shambler came peering round a corner to see what the noise was.

Kress went through the house room by room, turning on lights everywhere he went until he was surrounded by a blaze of artificial illumination.

He paused to clean up in the living room, shoveling sand and plastic fragments back into the broken tank.

The body shifted once again, moving a few centimeters toward the castle.

He retreated upstairs, returning shortly with a cleaver.

The screen began to clear, indicating that someone had answered at the other end.

He listened for several uneasy moments, wondering if Idi Noreddian could possibly have survived, and was now scratching to get out.

The black castle was glittering with volcanic glass, and sandkings were all over it, repairing and improving.

He stood his ground, sweeping his misty sword before him in great looping strokes.

One landed on his faceplate, its mandibles scraping at his eyes for a terrible second before he plucked it away.

The mist settled back on him, making him cough.

They were all around him, on him, dozens of them scurrying over his body, hundreds of others hurrying to join them.

Kress heard a loud hiss, and the deadly fog rose in a great cloud from between his shoulders, cloaking him, choking him, making his eyes burn and blur.

He stumbled and screamed, and began to run back to the house, pulling sandkings from his body as he went.

Inside, he sealed the door and collapsed on the carpet, rolling back and forth until he was sure he had crushed them all.

The canister was empty by then, hissing feebly.

His hand shook as he poured, slopping liquor on the carpet.

He sat at the console, frowning.

Their skimmer passed low overhead first, checking out the situation.

The black army burned and disintegrated, the mobiles fleeing in a thousand different directions, some back toward the castle, others toward the enemy.

Kress pounded wildly on the window, shouting for attention.

He brought it down sharply, hacking at the sand and stone parapets.

The laser bit into the ground, searching round and about.

Then he used the lasercannon, crisscrossing methodically until it was certain that nothing living could remain intact beneath those small patches of ground.

“Is that safe in here?” he found himself muttering, pointing at the flamethrower.

She stepped into the door, shifted the laser to her left hand, and reached up with her right, fumbling inside for the light panel.

He closed his eyes and waited, expecting to feel their terrible touch, afraid to move lest he brush against one.

His shambler followed him down the stairs, staring at him from its baleful glowing eyes.

Kress slipped outside, carrying his bags awkwardly, and shut the door behind him.

For a moment he stood pressed against the house, his heart thudding in his chest.

Kress smiled, and walked slowly across the battleground, listening to the sounds, the sounds of safety.

A white sandking watched him from atop the dresser in his bedroom, its antennae moving faintly.

They were making modifications in his house, burrowing into or out of his walls, carving things.

He went outside to get the bodies that had been rotting in the yard, hoping to appease the white maw’s hunger.

They avoided the frozen food, leaving it to thaw in a great puddle, but they carried off everything else.

He closed the door behind his latest guest, ignoring the startled exclamations that soon turned into shrill gibbering, and sprinted for the skimmer the man had arrived in.

Kress rose, holding his breath, not daring to hope.

He ran down the stairs, jumping over sandkings.

Finally he got out and checked, expecting the worst.

Kress went to his communicator again, stepping on a sandking in his haste, and prayed fervently that the device still worked.

The fear was on him again, filling him, and with it a great thirst and a terrible hunger.

He ran down the hill toward the house, waving his arms and shouting to the inhabitants.

Published on May 02, 2019 03:44

May 1, 2019

The Moment Of Avoidance

Faber and Faber, 1970.

Faber and Faber, 1970."Beautiful women with corrupt natures -- they have always been my life's target. There must be bleakness as well as loveliness in their gaze: only then can I expect the mingled moment."

-- Brian W. Aldiss, "The Moment of Eclipse." (1969)

Aldiss: the frustrator of expectations. Some of his work I respect, but some of it makes me want to bash my head against the kitchen sink. This mingled moment comes through most clearly in the story at hand.

Here we have a marvelous control of tone, melody and rhythm, imagery and symbol, but a narrative that collapses with a ffffffffffwuffffffff like a neglected balloon.

Any story makes a promise, and a good one keeps it. Aldiss implies a tale of perversion and danger, but as the story goes on, he avoids both. The narrator's "corrupt woman" is neither especially corrupt nor threatening, and he somehow manages to veer away from her at every possible encounter:

"It may appear as anti-climax if I admit that I now forgot about Christiania, the whole reason for my being in that place and on that continent. Nevertheless, I did forget her; our desires, particularly the desires of creative artists, are peripatetic: they submerge themselves sometimes unexpectedly and we never know where they may appear again. My imp of the perverse descended. For me the demolished bridge was never rebuilt."

Okay. Sure.

Instead of the story promised, Aldiss has another tale in mind. He supports it with recurring symbols (eyes and eclipses), then brings it to a crisis well-described and eerie. But once that mood has been established, the ending goes fffffffwuffffffff.

In effect, he does this:

"I'm crushed by a terrible spiritual burden!"

"Here, let me solve it for you."

"Okay. Sure."

The End.

What we have, then, is "The Moment of Avoidance," and this refusal to confront its own initial set-up is the most perverse thing about it. None of its fine prose, none of its otherwise firm technique, can salvage the story that Aldiss failed to write.

Published on May 01, 2019 12:37

April 20, 2019

None of This Matters to Anyone, But What the Hell....

Click to Enlarge

Click to EnlargeI have never understood those people who love to read, yet never seem to read verse. After all, the same qualities and techniques that we find in good prose, we find in verse: a studied use of alliteration and assonance, parallel construction, rhetoric, imagery, metaphor. Even if the concentration of a poem goes beyond much of what we find in prose at its most prosaic, I doubt that many readers would be tripped up by this intensity.

Readers unfamiliar with poetic techniques of metrical regularity and substitution can still hear what a poem is doing. For example, this poem by Edna St. Vincent Millay uses iambic pentameter as the basis for its rhythm, but plays against the rhythm by replacing iambs with trochees, pyrrhics, and spondees. Must readers understand these methods to appreciate the result? No, not as long as they can read aloud, attentively, with a normal pronunciation of words.

SONNET: HERE IS A WOUND THAT NEVER WILL HEAL,

by Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Here is a wound that never will heal, I know,

Being wrought not of a dearness and a death,

But of a love turned ashes and the breath

Gone out of beauty; never again will grow

The grass on the scarred acre, though I sow

Young seed there yearly and the sky bequeath

Its friendly weathers down, far underneath

Shall be such bitterness of an old woe.

That April should be shattered by a gust,

That August should be levelled by a rain,

I can endure, and that the lifted dust

Of man should settle to the earth again;

But that a dream can die, will be a thrust

Between my ribs forever of hot pain.

- - - - - - - -

From

The Selected Poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay.

The Modern Library, New York, 2001.

Published on April 20, 2019 11:52

April 1, 2019

"Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote...."

Some exciting new books are on the way!

Cover attributed to George Wilson.

Cover attributed to George Wilson.

Cover by Jesse Santos.

Cover by Jesse Santos.

Cover by George Wilson.

Cover by George Wilson.

Cover attributed to George Wilson.

Cover attributed to George Wilson.

Cover attributed to George Wilson.

Cover attributed to George Wilson.

Cover by Jesse Santos.

Cover by Jesse Santos.

Cover by George Wilson.

Cover by George Wilson.

Cover attributed to George Wilson.

Cover attributed to George Wilson.

Published on April 01, 2019 18:38

March 26, 2019

Beyond the Ken of Sublunar Spirits

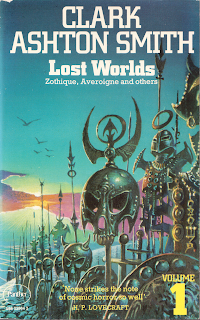

Cover by Bruce Pennington. Panther Books, 1974.

Cover by Bruce Pennington. Panther Books, 1974."The Beast of Averoigne," by Clark Ashton Smith.

After time spent reading stories in Weird Tales that took too many pages to begin and too many words to say what a single noun or verb could have managed, I went back to this old favourite, first read in 1974, and found it as effective now as it was back then.

Smith's training in verse had taught him the value of compression. Not even C. L. Moore, Smith's Weird Tales rival in concepts and imagery, could match the density of his prose.

Too many stories are written as if the primary unit of information were the paragraph, but traditional poetic forms require a tighter focus, not only on the sentence, not only on the clause, but on the word. Smith understood this, and was willing to let a bare statement do all the work of implication that he needed:

"So, on the forenoon of that same day, Theophile, together with Gerome and six others chosen for their hardihood, sallied forth and made search of the forest for miles around. They entered with torches and lifted crosses the deep caves to which they came, but found no fiercer thing than wolf or badger. Also, they searched the crumbling vaults of the deserted castle of Faussesflammes, which was said to be haunted by vampires. But nowhere could they trace the monster or find any sign of its lairing."

This method allowed him to put the reader into a scene without needless elaboration:

"On the night following the desecration of the graves, two charcoal-burners who plied their trade in the forest not far from Perigon, were slain in their hut. Other charcoal-burners, dwelling near by, heard the shrill screams that fell to sudden silence; and peering fearfully through the chinks of their bolted doors, they saw anon in the starlight the departure of a black, obscenely glowing shape that issued from the hut."

"Peering fearfully through the chinks of their bolted doors" is just enough physical detail to give the scene a sense of place. Smith provides the detail, and then moves on.

His trust in the magic of words allowed him to state briefly what others might feel compelled to spell out in detail:

"Vainly I consulted the stars and made use of geomancy and necromancy; and the familiars whom I interrogated professed themselves ignorant, saying that the Beast was altogether alien and beyond the ken of sublunar spirits."

Always, the descriptions are brief, and conveyed in motion:

"Passing among the ancient trees that towered thickly behind Perigon, he thought that he discerned a light from the windows, and was much cheered thereby. But, going on, he saw that the light was near at hand, beneath a lowering bough. It moved as with the flitting of a fen-fire, and was of changeable color, being pale as a corposant, or ruddy as new-spilled blood, or green as the poisonous distillation that surrounds the moon."

As a result, the story moves rapidly at a steady pace.

This version published in Weird Tales is leaner and swifter than the original, and for that reason I prefer it. (It also has an effective use of a Chekhov's Gun in its gem-imprisoned demon, which adds to its appeal for me.)

I can understand that many readers might find compressed writing difficult to process, that they might prefer a slower pace and less density of information. But I have my own tastes, and the aesthetic qualities that drew me to Clark Ashton Smith decades ago still hold me in their spell.

Published on March 26, 2019 05:46

March 22, 2019

"Vive la différence!"

Given all of the recent discussion about toxic masculinity, I've tried to think of positive traits that men contribute to the world, only to suspect that every good masculine trait is echoed by a feminine trait.

Think of courage: physical courage in the face of danger, moral courage in the face of social conflict. These are excellent traits, but women have them, too.

Protectiveness? Women can be just as protective as men.

Intelligence, compassion, endurance, drive? Again, women also have these traits.

What can men contribute, that women cannot? Beyond semen, which I consider important and which I'm always glad to share, I can't think of anything specifically masculine that could not also be contributed by women.

A neurologist might argue that distinctions do exist between male and female brains, but even if this might be true, normal human plasticity can do a lot to smooth over these differences, in the same way that technology can minimize differences of size and physical strength.

With all of this in mind, is there any value in talking about masculine traits and feminine traits outside of the bedroom, outside of the maternity ward? Is it possible, otherwise, that we're all just... human?

I would never deny the differences between people, but I would also wonder if it might make more sense to consider these differences, not in the light of masculine or feminine traits, but in the light of different personalities. Both men and women can be introverts or extroverts, artistic or analytic, romantic or classical, caring or callous, and so on. None of these distinctions is inherently masculine or feminine.

"Vive la différence!" I love that difference, I cherish it, but I have to wonder if it's really a big difference.

Published on March 22, 2019 11:06

March 10, 2019

The Curse of the Boa Constrictor Paragraph

Line engraving by P. Vanderbank, 1683.

Line engraving by P. Vanderbank, 1683.I read more poetry than a human being should, and have been changed for the worse in result. I have no more patience for bloated prose, no more of what used to be called charity for the implied intentions of a writer. I want the prose to move.

What do I mean by bloated? This would depend on context, and on how much energy a writer can bring to words.

For example, I would never call bloated this passage by Thomas Browne:

"If we more nearly consider the condition of Vipers and noxious Animals, we shall discover another higher provision of Nature: how, although in their paucity she hath not abridged their malignity, yet hath she notoriously effected it by their secession or latitancy. For not only offensive insects, as Hornets, Wasps, and the like, but sanguineous corticated Animals, as Serpents, Toads, and Lizards, do lie hid and betake themselves to coverts in the Winter. Whereby most Countries enjoying the immunity of Ireland and Candie, there ariseth a temporal security from their venoms; and an intermission of their mischiefs, mercifully requiting the time of their activities."

[From "Of the Viper," in Pseudodoxia Epidemica (Third Book), 1646-1672.]

His writing works the tongue and ear while remaining dense with detail, but for all of its thickness of texture, it moves rapidly.

In contrast, here are two paragraphs from a story I tried to read this afternoon:

"Whatever particle of a doubt there may have been in Mrs. Owens’s own mind, there was considerable more of doubt and apprehension in Mr. Evening’s as he weighed, in his rooming house, the rash decision he had made to visit formidable Mrs. Owens in -- one could not say her business establishment, since she had none -- but her background of accumulation of heirlooms, which vague world was, he could only admit, also his own. Because he had never known or understood people well, and he was the most insignificant of 'collectors,' he was at a loss as to why Mrs. Owens should feel he had anything to give her, and since her 'legend' was too well known to him, he knew she, likewise, had nothing at all to give him, except, and this was why he was going, the 'look-in' which his visit would give him. Whatever risk there was in going to see her, and there appeared to be some, he felt, from 'warnings' of a queer kind from those who had dealt with her, it was worth something just to get inside, even though again he had been informed by those in the business it would be doubtful if he would be allowed to mention 'purchase' and in the end it was also doubtful he would be allowed even a close peek.

"On the other hand, if Mrs. Owens wanted him to tell her something -- this crossed his mind as he went toward her huge pillared house, though he could not imagine even vaguely what he could have to tell her, and if she was mad enough to think him capable of entertaining her, for after all she was a lonely ancient lady on the threshold of death, he would disabuse her of all such expectations almost as soon as they had met. He was uneasy with old women, he supposed, though in his work he spent more time with them than with other people, and he wanted, he finally said out loud to himself, that hand-painted china cup, 1910, no matter what it might cost him. He fancied she might yield it to him at some atrocious illegal price. It was no more improbable, after all, than that she had invited him in the first place. Mrs. Owens never invited anybody, that is, from the outside, and the inside people in her life had all died or were incapacitated from paying calls. Yes, he had been summoned, and he could hope at least therefore that what everybody else told him was at least thinkable -- purchase, and if that was not in store for him, then the other improbable thing, 'viewing.'"

[From "Mr. Evening," in The Complete Short Stories of James Purdy.]

Crammed with needless qualifications (he supposed, he fancied, after all, he felt, even though again, he could only admit), these boa constrictor paragraphs coil around and swallow meaning without offering any counter virtues of surprise or fire. In a novel they would seem ponderous; in a short story, incongruous.

And in a poem, of course, impossible.

Published on March 10, 2019 09:17

March 2, 2019

Algolagnia in Carrion

You pour the words upon the page

And let them turn;

You bore the student and the sage.

Dry up, Swinburne!

Your gushing stanzas blot the land

And tread the fern;

They crush the readers into sand.

Enough, Swinburne!

I have waded through words like a heron,

Without even a frog to consume,

As your pages extend, flat and barren,

To fill every niche in the room,

And I ask, Why the pain? Why the wind burn

That buffets my eyes to their cores?

I've read more than I need of you, Swinburne,

Our Baron of Bores.

And let them turn;

You bore the student and the sage.

Dry up, Swinburne!

Your gushing stanzas blot the land

And tread the fern;

They crush the readers into sand.

Enough, Swinburne!

I have waded through words like a heron,

Without even a frog to consume,

As your pages extend, flat and barren,

To fill every niche in the room,

And I ask, Why the pain? Why the wind burn

That buffets my eyes to their cores?

I've read more than I need of you, Swinburne,

Our Baron of Bores.

Published on March 02, 2019 17:42