Mark Fuller Dillon's Blog, page 21

August 3, 2019

You're no worse than anything else when one gets to know you.

Click for a larger view.

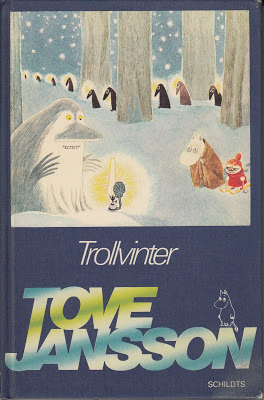

Click for a larger view.Tove Jansson, MOOMINLAND MIDWINTER (1957; translated by Thomas Warburton, 1958).

When I was nine years old, I had already begun to read adult fiction by Wells, Poe, Clarke, Simak, and even (although I failed to understand him at the time) J. G. Ballard. Still, when a friend of the family lent us copies of Tove Jansson's COMET IN MOOMINLAND and FINN FAMILY MOOMINTROLL, I fell in love with the books. In my late 'teens, I read them again, but even though I had bought copies of her later books, I was never able to work up an interest in reading them, because the new characters were unfamiliar to me; they were not the creatures I had loved from the early books.

This quality of seeming foreign, this idea of being separated from people and circumstances loved in the past, is very much a part of the book I read yesterday, MOOMINLAND MIDWINTER. I have no idea what the book might have said to me at the age of nine, but it spoke to me with surprising relevance at the age of fifty-five.

The characters at the heart of the previous books, the Moomins, have always hibernated during winter, but this year Moomintroll, the son (the protagonist of the other stories), wakes up and finds himself unable to sleep in a world utterly alien to his experience. Everything familiar has been altered by cold and by snow; the landscapes, and even his own house, have been infiltrated by secretive creatures ("the lonely and the rum, the wild and the quiet") who have winter purposes of their own. One of these creatures, the angry and elusive Dweller Under The Sink, even has a language of his own that no one else can understand; another, a bizarre "ancestor" of the Moomin species, has no language at all, and is apparently deaf and blind to any of Moomintroll's efforts to bond with him.

As a result of these alien circumstances, Moomintroll spends much of the book in lonely despair. While the one person he knew in summer who is also wide awake in the cold, Little My, thrives in the snow and takes every opportunity to experiment with winter sports, Moomintroll longs for summer light and summer heat, for bathing in the sea and talking to the people he loves. Even when he tries to learn about the new, mysterious creatures around him, he can only catch glimpses of their furtive activities.

Click for a larger view.

Click for a larger view.One of these beings, an adult named Too-ticky, does treat him with kindness, but even her generosity of spirit is touched by winter: she remains a foreigner in Moominland, a friend yet at the same time Other:

Too-ticky looked at him with her calm blue eyes. Still, he wasn't quite sure that she really did see him. She was looking into her own private winter world that had followed its own strange rules year after year, while he had lain sleeping in the warm Moominhouse.She does her best to share this private winter world with the clearly-grieving Moomintroll, but her terms are not his:

"What song is that?" asked Moomintroll.Moomintroll wants the certainty of summer light, but nothing in this nocturnal world makes any sense to him. Everything shifts in the cold, and meanings are hard to determine. When he confesses that he does not understand snow, Too-ticky replies:

"It's a song of myself," someone answered from the pit. "A song of Too-ticky, who built a snow-lantern, but the refrain is about wholly other things."

"I see," Moomintroll said and seated himself in the snow.

"No, you don't," replied Too-ticky genially and rose up enough to show her red-and-white sweater. "Because the refrain is about the things one can't understand. I'm thinking about the aurora borealis. You can't tell if it really does exist or if it just looks like existing. All things are so very uncertain, and that's exactly what makes me feel reassured."

"I don't either.... You believe it's cold, but if you build yourself a snowhouse it's warm. You think it's white, but at times it looks pink, and another time it's blue. It can be softer than anything, and then again harder than stone. Nothing is certain."There is one certainty: the winter can kill. A creature freezes to death. Soon refugees from the cold arrive, to seek food and shelter. Moomintroll allows them to stay in the house of his family. Unlike Little My, who revels on the snow and ice with no concern for people, Moomintroll wants to help the strangers, but at the same time, he wants to protect his helplessly-sleeping family and their home; this conflict adds to the weight of his despair.

Only near the end of the book does life change for the better, when he witnesses, for the first time, the wonder of actual falling snow:

"Oh, it's like this," thought Moomintroll. "I believed it simply formed on the ground somehow."Caught in a terrible blizzard, he learns to overcome his fear by allowing himself to be taken by the wind and the snow:

"Frighten me if you can," he thought happily. "I'm wise to you now. You're no worse than anything else when one gets to know you. Now you won't be able to pull my leg any more."In the previous books, in his will to adventure and his bravery, Moomintroll was very much the son of his father; here, in his compassion, in his concern for home and family, in his willingess to endure with patience, he becomes the son of his mother. This gives a haunting poignancy to his reunion with her in the spring time:

Moominmamma scooped up a handful of snow and made a snowball. She threw it clumsily, as mothers do, and it plopped to the ground not very far away.

"I'm no good at that," said Moominmamma with a laugh. "Even Sorry-oo would have made a better throw."

"Mother, I love you terribly," said Moomintroll.Despair and loneliness have not crippled him; instead, he now sees possibilities in life that had never occured to him in his younger days:

The Snork Maiden had come across the first brave nose-tip of a crocus. It was pushing through the warm spot under the south window, but wasn't even green yet.

"Let's put a glass over it," said the Snork Maiden. "It'll be better off in the night if there's a frost."

"No, don't do that," said Moomintroll. "Let it fight it out. I believe it's going to do still better if things aren't so easy."

Suddenly he felt so happy that he had to be alone.I wish I had read this book as a child; perhaps, being on the verge of adolescence and wary of the changes in store, I might have understood it. Still, nothing was lost in reading it now: stuck as I am in a mid-life crisis and struggling to find a way through a landscape both empty and threatening, I needed this book, and I can share my gratitude.

Published on August 03, 2019 01:17

July 31, 2019

What he loves is not at all frightening, and what should be frightening seems to bore him.

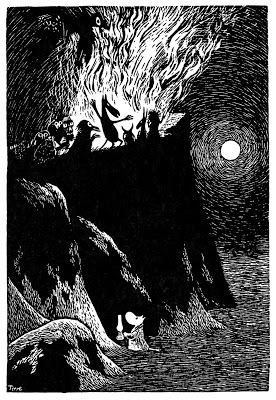

Cover by Douglas Walters, for the Ash-Tree Press edition, 2012."Negotium Perambulans..." features some of E. F. Benson's best writing, a well-described locale, and a slavering monster, yet the story has never worked for me. Why not?

Cover by Douglas Walters, for the Ash-Tree Press edition, 2012."Negotium Perambulans..." features some of E. F. Benson's best writing, a well-described locale, and a slavering monster, yet the story has never worked for me. Why not?1) SETTING SHOULD BE ATMOSPHERE.

Whether an actual place or a creation of Benson's idle moments, the fishing village of Polearn inspires him to write with his full attention. He describes it so thoroughly that "Negotium Perambulans..." could almost be a passage from a traveller's diary:

"The casual tourist in West Cornwall may just possibly have noticed, as he bowled along over the bare high plateau between Penzance and the Land’s End, a dilapidated signpost pointing down a steep lane and bearing on its battered finger the faded inscription 'Polearn 2 miles', but probably very few have had the curiosity to traverse those two miles in order to see a place to which their guide-books award so cursory a notice."

Benson clearly loves the place as if he had lived there, as if he wanted to return there for the rest of his life, to spend his days in peace. The trouble, here, is that his love makes the setting desirable and soothing, but not at all eerie. Any mood of dread that he would like to build up in the story is undermined by the calm and sunlit beauty of sea cliffs and shore.

2) REPETITION BREEDS TEDIUM.

A terrible supernatural event has left its mark on the past. Then it happens again. When it happens for a third time, the reader has every right to wonder if such repetition might not make this event more common than unusual.

Another day, another brutal death. Ho hum. At least the weather is fine and the fishing is good.

3) DRINKING BY YOURSELF IS WICKED, AND SO IS PAINTING.

"A church far more ancient than that in which my uncle terrified us every Sunday had once stood not three hundred yards away, on the shelf of level ground below the quarry from which its stones were hewn. The owner of the land had pulled this down, and erected for himself a house on the same site out of these materials, keeping, in a very ecstasy of wickedness, the altar, and on this he dined and played dice afterwards."

A non-religious reader might feel compelled to ask if the supernatural punishment meted out in the story (three times!) was actually deserved. By the date the story was published, in 1922, the world had already seen several thousand years of wickedness more terrible than the crime on display, here. That one "sinner" also drinks alone, and the other paints eerie pictures, hardly seems to merit an earthly retribution, let alone a supernatural fate.

4) THIS HAPPENED TO SOMEONE ELSE, BUT I'M JUST FINE, THANKS.

In my favourite Benson stories ("The Face," "Caterpillars," "The Room in the Tower," "The Horror Horn"), the narrator, or the third-person viewpoint character, is confronted by horror directly, is personally involved; this allows the reader to feel the same dreads and uncertainties. Even in a story like "The Sanctuary," in which the narrator pops up unexpectedly halfway through -- Hi, I'm the narrator! I'll bet you didn't know that I existed, huh? -- this character still takes part in the story and witnesses events on his own.

In contrast, "Negotium Perambulans..." takes a distant view. Terrible things happen to other people, but not to the narrator. He tells us that other people are consumed by fear, but he is not; these events have little to do with him. As a result, there is no build-up of tension, and for that reason, when the narrator does encounter a monster on the final page, this encounter comes and quickly goes without effect.

All of these points undermine a story that could have been one of his better ones. I rarely find, in his work, writing that can match the quiet assurance of this prose:

"Before getting into bed I drew my curtains wide and opened all the windows to the warm tide of the sea air that flowed softly in. Looking out into the garden I could see in the moonlight the roof of the shelter, in which for three years I had lived, gleaming with dew. That, as much as anything, brought back the old days to which I had now returned, and they seemed of one piece with the present, as if no gap of more than twenty years sundered them. The two flowed into one like globules of mercury uniting into a softly shining globe, of mysterious lights and reflections."

This combination of specific, physical detail and abstract implication represents, for me, Benson at his best.

I find a later passage less effective:

"He was justified in his own estimate of his skill: he could paint (and apparently he could paint anything), but never have I seen pictures so inexplicably hellish. There were exquisite studies of trees, and you knew that something lurked in the flickering shadows. There was a drawing of his cat sunning itself in the window, even as I had just now seen it, and yet it was no cat but some beast of awful malignity. There was a boy stretched naked on the sands, not human, but some evil thing which had come out of the sea. Above all there were pictures of his garden overgrown and jungle-like, and you knew that in the bushes were presences ready to spring out on you...."

Here, the adjectives are banal, and do not convey, but assert. With a better choice of words, with more justification by physical detail, the passage could have been interesting, but Benson seems not to have given it much concern.

This is the trouble with "Negotium Perambulans...": in the story, Benson focuses best on what he loves, but what he loves is not at all frightening, and what should be frightening seems to bore him.

Published on July 31, 2019 03:53

July 28, 2019

A Gasp That Blocks Your Throat

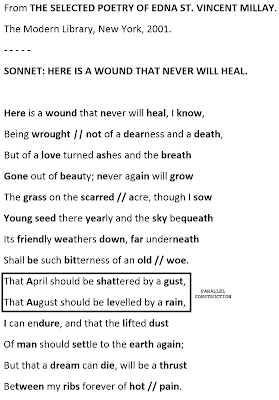

Click on this image for a larger view.One of the many things I love about metrical substitution is that it can guide you to read a poem in a certain way, and when used with harsh, clashing combinations of sound, it can force a poem's impact right down to your bones.

Click on this image for a larger view.One of the many things I love about metrical substitution is that it can guide you to read a poem in a certain way, and when used with harsh, clashing combinations of sound, it can force a poem's impact right down to your bones.In this example, here and there an iamb has been replaced by a spondee, a foot with two-equally stressed syllables, to produce a hammering that forces the reader to pause:

wrought // not

scarred // acre

old // woe

hot // pain

Each time, the result is like a gasp that blocks your throat.

Published on July 28, 2019 19:24

July 18, 2019

"We own the right to be fed up with anything we damn please...."

So. 49TH PARALLEL. A propaganda film created for the sole purpose of convincing the American people to rise up against Hitler. Unsubtle, with a shameless, crowd-pleasing finale, it should have been a disaster.

Instead, it was filmed by Powell and Pressburger, and it's magnificent. Flawed, but still magnificent.

That the film was also scored by Vaughan Williams, that it was photographed by Freddie Young and edited by David Lean, are dabs of frosting on a tasty cake.

Parts of the film do seem contrived: a sequence with Leslie Howard as a decadent, art-loving anthropologist who can't be bothered to fear an armed Nazi; Laurence Olivier as the world's least convincing French Canadian (a shame, because his character has a few of the best lines).

Other parts of the film are as good as anything by Powell and Pressburger: a thoughtful sequence in a German Hutterite community, led by Anton Walbrook, where Nazi arguments for German unity are not accepted; Niall MacGinnis as a reluctant soldier (an understated, humane performance); and best of all, a tense and frightening plane crash that is a brilliant showcase for sound effects, editing, acting, photography, and direction: a great sequence.

So yes, 49TH PARALLEL is a propaganda film, but the work and thought applied to it have made it much more lasting than propaganda, much more fun.

Published on July 18, 2019 13:41

It Won't Kill You

Someone posted a manuscript online and asked for opinions. I told him that his first paragraphs included a misplaced modifier, inaccurate nouns, ambiguous pronouns, non-standard usage, a sentence that would have gained from parallel construction, and a misuse of the subjunctive mood. Then I told him that he should study grammar, and offered a link to a useful book.

Someone posted a manuscript online and asked for opinions. I told him that his first paragraphs included a misplaced modifier, inaccurate nouns, ambiguous pronouns, non-standard usage, a sentence that would have gained from parallel construction, and a misuse of the subjunctive mood. Then I told him that he should study grammar, and offered a link to a useful book.He deleted the manuscript.

Several weeks later, he posted the manuscript again, without revision. I pointed out the same flaws, and once again offered a link.

He deleted the manuscript.

I have to wonder what he expected. Did he think the bad writing would heal by itself? "Oh look, it got better!"

Listen: when I tell you that you need to study grammar, I'm not insulting you, I'm not calling you an idiot, I'm not hinting that you're a lousy human being; I'm telling you that you need to study grammar.

Published on July 18, 2019 13:02

July 16, 2019

If You Write

If you write, with clarity, economy, literacy, and force, bizarre short stories, or verses in traditional forms and metres, that are neither pastiches nor "tributes" nor part of a series, that explore personal obsessions and imagery while avoiding the standard clichés (vampires, werewolves, Lovecraftean seafood), and all self-published in ebook form, then please, send me a link to a sample of your work.

I'd like to see what you can do.

I'd like to see what you can do.

Published on July 16, 2019 11:03

July 4, 2019

"Their Use is Not to Inquire for Good Books, But New Books"

The Archers

The ArchersWatching CONTRABAND last night made me wonder why Powell and Pressburger films are not more popular. There is no lack of incentive to try them -- after all, countless hordes of critics, along with directors like Scorsese, Romero, and Coppola, have raved about these films for decades. Nor, thanks to home video, is there any lack of access.

CONTRABAND is not what I would call a great film, but in writing and direction, it shows more creativity, more energy and passion, than all too many acclaimed films I've seen from the past few decades. These "big" films come and go, are deservedly forgotten: who talks about THE ARTIST nowadays, or THE KING'S SPEECH, or (to look further into the dead past) CHARIOTS OF FIRE?

I would argue, too, that in terms of cleverness and drive, CONTRABAND is a better film than most of the stuff I've regretted watching from Marvel or Disney -- and CONTRABAND can't even begin to compare with BLACK NARCISSUS, THE LIFE AND DEATH OF COLONEL BLIMP, THE RED SHOES, A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH, or I KNOW WHERE I'M GOING.

Then again, I could raise the same points about films by Carné and Prévert, by Renoir, Keaton, Lloyd, Lubitsch, von Sternberg, Lean, Sturges, Aldrich, or even (to my astonishment) by Sirk; I could talk about any number of demotic, accessible, delightful, and thrilling movies that repay a viewer's time with qualities impossible to calculate, films readily available and ready to be watched.

In his preface to THE WHITE DEVIL, John Webster compared the theatre-goers of his time to those readers who, "visiting stationer's shops, their use is not to inquire for good books, but new books."

I could ask the same question of movie watchers. With so much gold from the past recovered and readily available, why do people allow themselves to settle for the latest corporate products with a shelf-life of months? Why not look around for films that can last a lifetime?

Published on July 04, 2019 13:12

Unfaded Pleasure

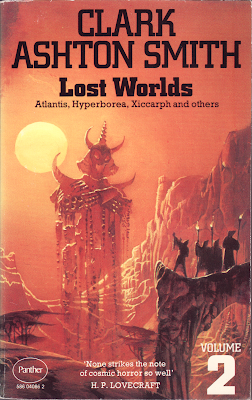

Cover by Bruce Pennington, 1974.

Cover by Bruce Pennington, 1974.Elsewhere on the vast filthy Web, someone asked for opinions about THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND, by William Hope Hodgson. I replied:

It was one of the many books that impressed me during my 'teen years, but which I now find clumsy to the point of pain. Was I wrong to admire it, way back when? No. Was I right to move on? Yes. Depending on who we are, on what we need to learn and to do, certain books are best for certain stages of our lives. Any work of prose or verse that can carry us through many stages is one to be loved, but works that only speak to us during one stage are not necessarily bad; they are stepping stones that we use and then pass by.

I will not deny the stories I loved when I was eleven years old; for me, at the time, they were great. That I find them unreadable now says more about me than it does about them.

Yet even after so many decades, I can still read, with unfaded pleasure, stories by H. G. Wells, Ambrose Bierce, and Clark Ashton Smith -- not because I read them now with an eleven-year-old's eyes and heart, not because of any nostalgia, but because the stories have grown as I have grown, in the same directions, and together.

Published on July 04, 2019 13:09

Technicians and Magicians

Can we learn a useful point by contrasting those filmmakers discussed all the time on Youtube with filmmakers rarely mentioned? I think we can.

Certain film creators are candidly technicians: their methods can be separated from their films and analyzed. We need technicians because they can show us how things are done; they can teach us the craft of movies, and inspire, in turn, a new generation of creators. When I think of technicians, I think of directors like Hitchcock, Lean, Welles: directors who allow the scaffolding to remain on their constructions, who leave their works open to be studied.

On the other hand, certain filmmakers are magicians: they rely on technique as thoroughly as technicians, but they conceal their methods behind layers of complexity or implication that cannot easily be separated from their films. The magicians I have in mind are directors like Powell and Pressburger, Renoir, Bergman.

Magicians could be studied. Someone on Youtube with time and ambition could sit down and take apart the methods used in a film like LA RÈGLE DU JEU, and compare them with CITIZEN KANE's. Nobody seems compelled to do this, yet I believe that technically-minded students could learn as much from Renoir as they could from Welles. They could learn as much about technique from BLACK NARCISSUS and PERSONA as they could from LAWRENCE OF ARABIA and PSYCHO, but the work needed to uncover the hidden methods of magicians is more complicated, more time-consuming, than the work needed to study technicians.

There is no value judgement, here: I love films by technicians and by magicians. Yet I can recognize the greater ease and clarity in taking apart the films of technicians than in staring at the chasms and whirlpools of magicians, even as magicians compel me to stare.

Certain film creators are candidly technicians: their methods can be separated from their films and analyzed. We need technicians because they can show us how things are done; they can teach us the craft of movies, and inspire, in turn, a new generation of creators. When I think of technicians, I think of directors like Hitchcock, Lean, Welles: directors who allow the scaffolding to remain on their constructions, who leave their works open to be studied.

On the other hand, certain filmmakers are magicians: they rely on technique as thoroughly as technicians, but they conceal their methods behind layers of complexity or implication that cannot easily be separated from their films. The magicians I have in mind are directors like Powell and Pressburger, Renoir, Bergman.

Magicians could be studied. Someone on Youtube with time and ambition could sit down and take apart the methods used in a film like LA RÈGLE DU JEU, and compare them with CITIZEN KANE's. Nobody seems compelled to do this, yet I believe that technically-minded students could learn as much from Renoir as they could from Welles. They could learn as much about technique from BLACK NARCISSUS and PERSONA as they could from LAWRENCE OF ARABIA and PSYCHO, but the work needed to uncover the hidden methods of magicians is more complicated, more time-consuming, than the work needed to study technicians.

There is no value judgement, here: I love films by technicians and by magicians. Yet I can recognize the greater ease and clarity in taking apart the films of technicians than in staring at the chasms and whirlpools of magicians, even as magicians compel me to stare.

Published on July 04, 2019 13:01

June 26, 2019

Shock or Silence

Humour can add to the force of a horror tale, but only if used with precision.

Ambrose Bierce, able to frighten me in ways that few others can match, offers good advice on this topic. Early in "The Damned Thing," during an inquest, a reporter on the stand says to the coroner:

The key phrase, here, is "in the intervals of battle." I would go further, and say, "before the battle." When faced with a build-up of anxiety, people often joke amongst themselves to break the mood, but when the crisis explodes, it demands their full attention. We see this frequently in Bierce, in L. P. Hartley, and in Elizabeth Bowen's "The Cat Jumps."

This dramatic device goes beyond horror stories. As a teenager, I noticed its power in 1981, when I saw the Peter Weir film GALLIPOLI several times in a cinema, and watched the audience respond to its humour.

Early in the film, when the characters laughed at their circumstances, the audience joined in the laughter. During the middle sequences, the characters, unaware of what lay in store for them, continued to joke and laugh, but the audience had stopped laughing: they could see all too clearly what was going to happen. During the final half hour, nobody laughed; there was nothing to laugh about.

In a horror story, mood and tone count for everything. As the tension builds, we can expect people to behave like people, to laugh at their own intimidating sense of unease, but there comes a point when both readers and characters must feel the weight of dread. When the worst has come to pass, the shock wave of that event should remain ringing in the air for a long while afterwards, or else the fear will be too quickly dissipated.

For an example of dissipation that kills the mood, I always think of the lousy script for ALIEN RESURRECTION. At one point in the film, Ripley stumbles onto her fellow clones, all of them so hideously deformed, so clearly in pain, that out of self-loathing and compassion, she burns them all. An idiot side-kick then stares in disbelief at the bodies, and mumbles, "What's the big deal, man? Must be a chick thing." And so the film dies.

Sometimes, in a story like "Wailing Well," by M. R. James, or "The Travelling Grave," by L. P. Hartley, the initial humour seems to acknowledge the absurdity of a concept, but even here, when things fall apart for the characters, the writers treat their fates with appropriate sobriety. "It's okay to laugh," they seem to tell us, "but stick around, and watch how we develop these ridiculous ideas into something creepy."

So yes, humour does add to horror, but only until the horror strikes. Afterwards, the best response is either shock or silence.

Ambrose Bierce, able to frighten me in ways that few others can match, offers good advice on this topic. Early in "The Damned Thing," during an inquest, a reporter on the stand says to the coroner:

"He seemed a good model for a character in fiction. I sometimes write stories."

"I sometimes read them."

"Thank you."

"Stories in general -- not yours."

"Some of the jurors laughed. Against a sombre background humor shows high lights. Soldiers in the intervals of battle laugh easily, and a jest in the death chamber conquers by surprise."

[THE COLLECTED WORKS OF AMBROSE BIERCE, VOLUME III -- CAN SUCH THINGS BE? The Neale Publishing Company, New York, 1909.]

The key phrase, here, is "in the intervals of battle." I would go further, and say, "before the battle." When faced with a build-up of anxiety, people often joke amongst themselves to break the mood, but when the crisis explodes, it demands their full attention. We see this frequently in Bierce, in L. P. Hartley, and in Elizabeth Bowen's "The Cat Jumps."

This dramatic device goes beyond horror stories. As a teenager, I noticed its power in 1981, when I saw the Peter Weir film GALLIPOLI several times in a cinema, and watched the audience respond to its humour.

Early in the film, when the characters laughed at their circumstances, the audience joined in the laughter. During the middle sequences, the characters, unaware of what lay in store for them, continued to joke and laugh, but the audience had stopped laughing: they could see all too clearly what was going to happen. During the final half hour, nobody laughed; there was nothing to laugh about.

In a horror story, mood and tone count for everything. As the tension builds, we can expect people to behave like people, to laugh at their own intimidating sense of unease, but there comes a point when both readers and characters must feel the weight of dread. When the worst has come to pass, the shock wave of that event should remain ringing in the air for a long while afterwards, or else the fear will be too quickly dissipated.

For an example of dissipation that kills the mood, I always think of the lousy script for ALIEN RESURRECTION. At one point in the film, Ripley stumbles onto her fellow clones, all of them so hideously deformed, so clearly in pain, that out of self-loathing and compassion, she burns them all. An idiot side-kick then stares in disbelief at the bodies, and mumbles, "What's the big deal, man? Must be a chick thing." And so the film dies.

Sometimes, in a story like "Wailing Well," by M. R. James, or "The Travelling Grave," by L. P. Hartley, the initial humour seems to acknowledge the absurdity of a concept, but even here, when things fall apart for the characters, the writers treat their fates with appropriate sobriety. "It's okay to laugh," they seem to tell us, "but stick around, and watch how we develop these ridiculous ideas into something creepy."

So yes, humour does add to horror, but only until the horror strikes. Afterwards, the best response is either shock or silence.

Published on June 26, 2019 19:06