Mark Fuller Dillon's Blog, page 19

September 26, 2019

The Climate Strike

The climate strike has brought out the worst in many old men. If anything, the pettiness and cowardice of current ruling-class and pundit discourse has grown even more toxic, and all because many young people have decided to fight back instead of to sit back and swallow corporate garbage.

For my part, I believe these young people are too late, but I refuse to mock them; I refuse to block their way, because I would rather see us die standing for a human cause, than die staring at the mindless robot flickers of a cell phone.

For my part, I believe these young people are too late, but I refuse to mock them; I refuse to block their way, because I would rather see us die standing for a human cause, than die staring at the mindless robot flickers of a cell phone.

Published on September 26, 2019 09:57

September 19, 2019

I Know

Yes, I know: posting as I do on this website is playing the lyre as Rome burns. I feel the tension of this awareness every moment of the day. It forces me to question why I bother to write, why I bother to get up in the morning, why I bother to do anything.

I have no excuse for acting as if our modern age were somehow normal, but I do have one explanation. In a few years, I'll be dead. When I was younger, I did as much as I could (within legal means) to prevent the sort of world in which we now find ourselves. I protested, I participated in committees, I mailed off books and pamphlets, I was arrested. But I'm not young any more, and nothing that I did back then has made a speck of difference.

Any hope for a different world, any hope for human survival, will have to come from young people with better ideas for protest and activism than I was able to put forward. I failed; they will have to succeed, or die. The task is theirs.

And so, if I talk about symphonies, or films, or poems, or short stories, please understand that these posts are indications of my failure. If I had better things to offer the world, I would share them.

I have no excuse for acting as if our modern age were somehow normal, but I do have one explanation. In a few years, I'll be dead. When I was younger, I did as much as I could (within legal means) to prevent the sort of world in which we now find ourselves. I protested, I participated in committees, I mailed off books and pamphlets, I was arrested. But I'm not young any more, and nothing that I did back then has made a speck of difference.

Any hope for a different world, any hope for human survival, will have to come from young people with better ideas for protest and activism than I was able to put forward. I failed; they will have to succeed, or die. The task is theirs.

And so, if I talk about symphonies, or films, or poems, or short stories, please understand that these posts are indications of my failure. If I had better things to offer the world, I would share them.

Published on September 19, 2019 14:12

August 25, 2019

The Worst of the Dream Tests

Just before I woke up this morning, I dreamt that I would have to face a test. I had no idea what the test would involve, or when it would begin; I only knew that it would present more of a challenge than any test I had ever taken.

As I waited for the test to be announced, I found myself working at the Coles Bookstore (which no longer exists) on Sparks Street. Even though I went through the motions of work, I was afraid of the test. I tried to convince myself that I had nothing to fear; after all, I had taken many tests in university and high school. How tough could a new test possibly be?

Still overcome with dread, I found myself joined at work by my last girlfriend, who left me seven years ago, and who now (in reality) lives on the other side of the continent. I will never see her again, but in the dream, there she was, right beside me.

She was emotionally distant, at first, but the job had tossed us together, and soon we began to talk. It became clear that she still had feelings for me, and as the dream went on, my anxiety over the test was replaced by a rush of excitement over the possibility that she and I would start all over again. For the first time in years, I felt hope; for the first time in a long time, I felt happiness, a sense of inner comfort, a sense of being whole. There was a genuine possibility that she and I would soon be together again, and I felt so good, so alive, so unbroken!

Only when I woke up did I understand how thoroughly I had failed the test.

As I waited for the test to be announced, I found myself working at the Coles Bookstore (which no longer exists) on Sparks Street. Even though I went through the motions of work, I was afraid of the test. I tried to convince myself that I had nothing to fear; after all, I had taken many tests in university and high school. How tough could a new test possibly be?

Still overcome with dread, I found myself joined at work by my last girlfriend, who left me seven years ago, and who now (in reality) lives on the other side of the continent. I will never see her again, but in the dream, there she was, right beside me.

She was emotionally distant, at first, but the job had tossed us together, and soon we began to talk. It became clear that she still had feelings for me, and as the dream went on, my anxiety over the test was replaced by a rush of excitement over the possibility that she and I would start all over again. For the first time in years, I felt hope; for the first time in a long time, I felt happiness, a sense of inner comfort, a sense of being whole. There was a genuine possibility that she and I would soon be together again, and I felt so good, so alive, so unbroken!

Only when I woke up did I understand how thoroughly I had failed the test.

Published on August 25, 2019 10:43

August 21, 2019

The Dead Valley

Photo by Marceau, 1911.

Photo by Marceau, 1911."The Dead Valley," by Ralph Adams Cram, in BLACK SPIRITS & WHITE. Stone & Kimball, Chicago, 1895.

One of my favourite horror stories, and, in my view, easily the best of Cram's fiction, "The Dead Valley" is unremarkable in its technique. Simply and rapidly, it tells a tale without excursions into side matters, but it also props up its narrative with good physical details and well-visualized scenes. Unlike too many stories that try to convey a mood of strangeness with assertions, Cram shows the reader the sounds, actions, and images that make his tale bizarre.

I put one foot into the ghostly fog. A chill as of death struck through me, stopping my heart, and I threw myself backward on the slope. At that instant came again the shriek, close, close, right in our ears, in ourselves, and far out across that damnable sea I saw the cold fog lift like a water-spout and toss itself high in writhing convolutions towards the sky. The stars began to grow dim as thick vapor swept across them, and in the growing dark I saw a great, watery moon lift itself slowly above the palpitating sea, vast and vague in the gathering mist.

Cram also skirts the trap of explanation, which adds to the force and mystery of his events. There is no reason for any of these things to happen, but they do, and the simple vividness of their presentation is enough to make the story seem real.

To these good qualities, Cram brings a further touch. At the end, he pulls back to show that the terrible night of his narrative is merely one speck on a vast continuum. This unexplained haunting has occurred over and over in the past, and will go on, perhaps forever. Because Cram has given this deadliness no reason to begin, it has no reason to stop; and this, too, adds to the story's power.

Published on August 21, 2019 01:43

August 19, 2019

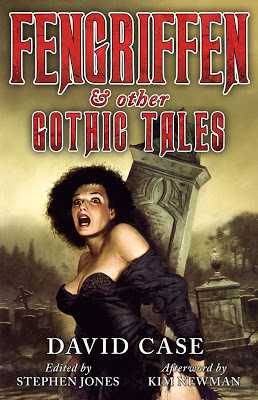

A Skeletal Impression of "Fengriffen."

Valancourt Books

Valancourt BooksBack in the 1980s, I considered "Fengriffen" a good story buried in pastiche. Reading it again today, I feel the same response.

I also have to wonder how many people stared at the first line, winced, and then tossed the book aside:

My first impression of Fengriffen House was skeletal.

Not content to give such a skeletal impression of his writing skill, David Case goes on to mangle another modifier:

I saw it from the carriage, rising against a stormy sundown like the blackened bones of some monstrous beast....

A first paragraph is the gateway into reading; this one is rusted and barely squeaks open, but once that stormy sundown of a narrator has walked into the house, the writing improves:

I looked at the moors and I smoked. When my pipe burned out I filled a second, lighted it, tamped it down carefully, and fired it again until it was burning evenly and the smoke was cool. Tobacco is an ally of contentment, and I told myself I must be content with the cheerful blaze still in the grate and the wind howling ineffectively outside, shaking the trees in a fury but unable to get to me -- indeed, defeating its purpose as in rage it sucked the draught up the chimney and caused my fire to burn more freely. I was able to judge the force of that wind by regarding the shadows beneath the trees. The filigreed moonlight shifted and blurred, laying silver tapestries beneath the limbs. It was hypnotic. I lost awareness of time as I studied the moving shadows. My second pipe went out. I pulled thoughtlessly at the mouthpiece. My eyes grew heavy. Then, gradually, I found myself looking at a different shadow. I must have observed it for some time before I realized it was more than the wind snatching the trees. For this shape had advanced beyond the trees, bringing a shadow of its own; it moved near to the house and then paused. I snapped to alertness. I stared at this dark form and had the grotesque impression that, whatever it was, it was staring back at me. A finger of ice tapped up the articulation of my backbone, leaving me rigid in its wake.

Too many present participles, but otherwise, not bad at all.

The story moves quickly, piles on details and complications with skill, holds the attention at all times. As a narrative, "Fengriffen" brings more than enough to make reading worthwhile, if you can accept the anonymity of pastiche. For me, it represents a dead end. I see no value in mimicking the writers of yesterday; I prefer those writers who have learned from the past, who have digested its methods to bring us ideas and obsessions of their own. The past is a guide, but should not be a limiting template.

As templated stories go, "Fengriffen" is one of the best. I can only wish that Case had used the tale to share private fears and personal images, to make the story his own.

Published on August 19, 2019 12:47

William Sansom And One Of His Best

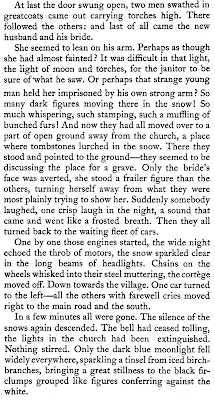

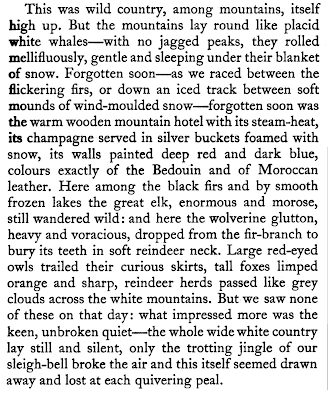

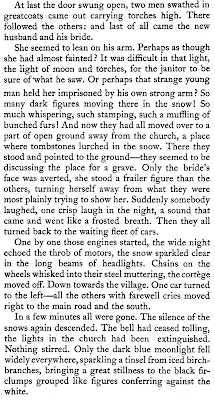

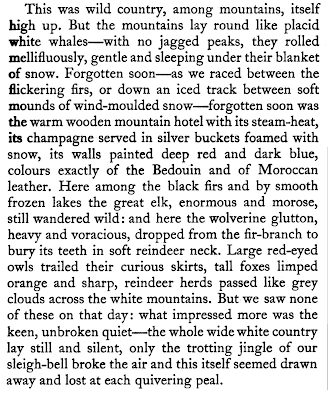

William Sansom, "A Wedding." From THE PASSIONATE NORTH, The Hogarth Press, London, 1950.

This is not only one of my favourite stories; it also reveals how a frame can be used to broaden our perspective on what might seem, at first glance, a small, isolated event, or to show its implications over a time-span greater than the story's. For me, "A Wedding" offers one of the best examples of its kind.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Because a few people have not read this one, I will not spoil the ending. Leave it to say that William Sansom has put all of the weight of his frame on the final sentence, and that this does not represent a twist ending, but a continuation of the plot with additional detail. A twist can be useful in the middle of a story, when space remains to explore the implications of the twist; it can be fatal at the story's end, where it often seems more like a gimmick than a thoughtful resolution. Sansom has taken the wise approach, and allowed the story to lope ahead without hindrance.

One detail that I can mention without spoiling the plot is the emphasis on setting. I love detailed landscapes in fiction, and here, Sansom has focused on strong visual impressions to make his writing live. Given the story's brevity, there is no room for any detailed exploration of character (and none is needed, in this context), but the place is rendered vividly and with economy of means.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Still and silent, the landscape is the perfect setting for a terrible event. William Sansom is a master of terrible events; in a "Wedding," he also becomes a master of the crowning detail.

This is not only one of my favourite stories; it also reveals how a frame can be used to broaden our perspective on what might seem, at first glance, a small, isolated event, or to show its implications over a time-span greater than the story's. For me, "A Wedding" offers one of the best examples of its kind.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.Because a few people have not read this one, I will not spoil the ending. Leave it to say that William Sansom has put all of the weight of his frame on the final sentence, and that this does not represent a twist ending, but a continuation of the plot with additional detail. A twist can be useful in the middle of a story, when space remains to explore the implications of the twist; it can be fatal at the story's end, where it often seems more like a gimmick than a thoughtful resolution. Sansom has taken the wise approach, and allowed the story to lope ahead without hindrance.

One detail that I can mention without spoiling the plot is the emphasis on setting. I love detailed landscapes in fiction, and here, Sansom has focused on strong visual impressions to make his writing live. Given the story's brevity, there is no room for any detailed exploration of character (and none is needed, in this context), but the place is rendered vividly and with economy of means.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.Still and silent, the landscape is the perfect setting for a terrible event. William Sansom is a master of terrible events; in a "Wedding," he also becomes a master of the crowning detail.

Published on August 19, 2019 08:04

Give Up, Give In, Or Get The Hell Away If You Can

Sometimes I wonder if the most divisive and jagged trench in the horror field might be Edgar Allan Poe.

How do writers respond to Poe? M. P. Shiel cries out in glee, and works hard to Poe-verize himself until he limps from the burden. Walter de la Mare grows beyond Poe quickly, to develop his own obsessions and his own voice. Clark Ashton Smith combines Poe with other people (William Beckford, George Sterling, Charles Baudelaire) to reduce Poe's toxicity. Ambrose Bierce and M. R. James follow their own pathways as if Poe had never existed, and all the better for themselves. Baudelaire... well, it's complicated.

But it seems clear to me that certain writers grab other writers by the throat, and shake them until the others give up, give in, or get the hell away if they can. Edgar Allan Poe, E. T. A. Hoffmann, and Sheridan Le Fanu seem to have been the most ferocious of the shakers in the field, but others have always lurked in the shadows. (John Webster?)

Poe seems to have been the deadliest of all of the shakers. If you managed to get away from him, count yourself lucky.

How do writers respond to Poe? M. P. Shiel cries out in glee, and works hard to Poe-verize himself until he limps from the burden. Walter de la Mare grows beyond Poe quickly, to develop his own obsessions and his own voice. Clark Ashton Smith combines Poe with other people (William Beckford, George Sterling, Charles Baudelaire) to reduce Poe's toxicity. Ambrose Bierce and M. R. James follow their own pathways as if Poe had never existed, and all the better for themselves. Baudelaire... well, it's complicated.

But it seems clear to me that certain writers grab other writers by the throat, and shake them until the others give up, give in, or get the hell away if they can. Edgar Allan Poe, E. T. A. Hoffmann, and Sheridan Le Fanu seem to have been the most ferocious of the shakers in the field, but others have always lurked in the shadows. (John Webster?)

Poe seems to have been the deadliest of all of the shakers. If you managed to get away from him, count yourself lucky.

Published on August 19, 2019 00:57

August 18, 2019

Really, Who Gives A Damn?

If the years have taught me anything at all, it's that genre is not only useless, but often pernicious: genre can distort perception, and give us false impressions of writers and their work.

Consider this false impression: I used to believe that I loved science fiction, horror, ghost stories, and certain types of fantasy. The truth is, I have never loved these things; instead, I have always loved the work of certain writers categorized, comfortably or kicking, into these illusory straitjackets.

One side-effect of my false belief was the nagging compulsion to "keep up" with various fields. This became a chore, then a burden, then a series of shooting pains, until I realized that only certain writers were able to speak to me; only certain writers were able to strike nerves that I had not known existed.

In contrast, one side-effect of losing this false belief was the liberating discovery that certain writers unconnected with genres were able to give me the same pleasures, the same frissons and shocks, that I had hoped to find within the genres. Labels were no longer useful to me, and the absence of labels was no longer a hindrance.

The result? If people were to ask me, now (and no one ever will, thank goodness, because really, who gives a damn about what I read?) "Do you like science fiction? Horror? Fantasy?" I would have to be honest, and say, No, I often hate them.

But if anyone were foolish enough to ask me about certain writers, I could talk for days on end, without end. No one would be fool enough to try, and my silence in the world beyond the Blind Side Web will remain untroubled.

Consider this false impression: I used to believe that I loved science fiction, horror, ghost stories, and certain types of fantasy. The truth is, I have never loved these things; instead, I have always loved the work of certain writers categorized, comfortably or kicking, into these illusory straitjackets.

One side-effect of my false belief was the nagging compulsion to "keep up" with various fields. This became a chore, then a burden, then a series of shooting pains, until I realized that only certain writers were able to speak to me; only certain writers were able to strike nerves that I had not known existed.

In contrast, one side-effect of losing this false belief was the liberating discovery that certain writers unconnected with genres were able to give me the same pleasures, the same frissons and shocks, that I had hoped to find within the genres. Labels were no longer useful to me, and the absence of labels was no longer a hindrance.

The result? If people were to ask me, now (and no one ever will, thank goodness, because really, who gives a damn about what I read?) "Do you like science fiction? Horror? Fantasy?" I would have to be honest, and say, No, I often hate them.

But if anyone were foolish enough to ask me about certain writers, I could talk for days on end, without end. No one would be fool enough to try, and my silence in the world beyond the Blind Side Web will remain untroubled.

Published on August 18, 2019 23:51

Details Accumulate

Ash-Tree Press, 2013.

Ash-Tree Press, 2013.A favourite of mine since I first read it in the 1970s, Edward Lucas White's "The Snout" is a good story burdened by a frame.

Frames can be effective when they bracket a story that the narrator has failed to understand, or when they add further implications to a story that might seem small at first glance. My favourite example of the latter case would be "A Wedding," by William Sansom, which could not work as a story without its frame, and which becomes all the more haunting with it.

In contrast, the frame of "The Snout" offers nothing that is not conveyed by the story itself. It also withholds information from the readers in a way that feels like cheating:

'Do you see anything in that cage?' he demanded in reply.

'Certainly,' I told him.

'Then for God's sake,' he pleaded. 'What do you see?'

I told him briefly.

'Good Lord,' he ejaculated. 'Are we both crazy?'

Ejaculations aside, the story, once it begins, is told with swift economy:

As if it had been broad day Thwaite drove the car at a terrific pace for nearly an hour. Then he stopped it while Rivvin put out every lamp. We had not met or overtaken anything, but when we started again through the moist, starless blackness it was too much for my nerves.

No time is wasted as a group of thieves break into the house of a mysterious hermit wealthy beyond imagination:

'Here's the place,' he said at the wall, and guided my hand to feel the ring-bolt in the grass at its foot. Rivvin made a back for him and I scrambled up on the two. Tip-toe on Thwaite's shoulders I could just finger the coping.

'Stand on my head, you fool!' he whispered.

I clutched the coping. Once astraddle of it I let down one end of the silk ladder.

'Fast!' breathed Thwaite from below.

I drew it taut and went down. The first sweep of my fingers in the grass found the other ring-bolt. I made the ladder fast and gave it the signal twitches. Rivvin came over first, then Thwaite. Through the park he led evenly. When he halted he caught me by the elbow and asked:

'Can you see any lights?'

The rapid pace and the tension continue, even while much of the story is devoted to wanderings through a mansion that, as the details accumulate, begins to seem less like a home and more like the prison of a being that might not be human.

The methods of "The Snout" can be hard to analyze, because nothing stands out in terms of technique beyond its rapid pace. Yet as the details of this house accumulate, the effect becomes dreamlike: nothing on its own might seem unusual, but as the pages go by, the odd little touches here and there begin to add up:

Close to me when the lights blazed out was a sea picture, blurred grayish foggy weather and a heavy ground-swell; a strange other-world open boat with fish heaped in the bottom of it and standing among them four human figures in shining boots like rubber boots and wet, shiny, loose coats like oilskins, only the boots and skins were red as claret, and the four figures had hyenas' heads. One was steering and the others were hauling at a net. Caught in the net was a sort of merman, but different from the pictures of mermaids. His shape was all human except the head and hands and feet; every bit of him was covered with fish-scales all rainbowy. He had flat broad fins in place of hands and feet and his head was the head of a fat hog. He was thrashing about in the net in an agony of impotent effort. Queer as the picture was it had a compelling impression of reality, as if the scene were actually happening before our eyes....

Then next to that was a fight of two compound creatures shaped like centaurs, only they had bulls' bodies, with human torsos growing out of them, where the necks ought to be, the arms scaly snakes with open-mouthed, biting heads in place of hands; and instead of human heads roosters' heads, bills open and pecking. Under the creatures in place of bulls' hoofs were yellow roosters' legs, stouter than chickens' legs and with short thick toes, and long sharp spurs like game roosters'. Yet these fantastic chimeras appeared altogether alive and their movements looked natural, yes that's the word, natural....

'Mr Hengist Eversleigh is a lunatic, that's certain,' Thwaite commented, 'but he unquestionably knows how to paint.'

A story, then, worth reading and revisiting. Too bad about the frame.

Published on August 18, 2019 00:24

August 16, 2019

A Glitter of Purple Water

Every time I read Marjorie Bowen's "The Sign-Painter And The Crystal Fishes," I begin with doubts, but end with praise.

The doubts are justified. Bowen writes with an intensely visual style, but her descriptions are often static:

The house was built beside a river. In the evening the sun would lie reflected in the dark water, a stain of red in between the thick shadows cast by the buildings. It was twilight now, and there was the long ripple of dull crimson, shifting as the water rippled sullenly between the high houses.

Beneath this house was an old stake, hung at the bottom with stagnant green, white and dry at the top. A rotting boat that fluttered the tattered remains of faded crimson cushions was affixed to the stake by a fraying rope. Sometimes the boat was thrown against the post by the strong evil ripples, and there was a dismal creaking noise.

While undeniably vivid, these images are better suited to the script of a stage play than to a narrative meant to involve the reader.

When the characters appear, they, too, are described as if they were actors on a stage:

There was no glass in the window, and the shutters swung loose on broken hinges. Now and again they creaked against the flat brick front of the house, and then Lucius Cranfield winced.

He held a round, clear mirror in his hand, and sometimes he looked away from the solitary tree to glance into it. When he did so he beheld a pallid face surrounded with straight brown hair, lips that had once been beautiful, and blurred eyes veined with red like some curious stone.

As the red sunlight began to grow fainter in the water a step sounded on the rotting stairway, the useless splitting door was pushed open, and Lord James Fontaine entered.

Slowly, and with a mincing step, he came across the dusty floor. He wore a dress of bright violet watered silk, his hair was rolled fantastically, and powdered such a pure white that his face looked sallow by contrast. To remedy this he had painted his cheeks and his lips, and powdered his forehead and chin. But the impression made was not of a pink and fresh complexion, but of a yellow countenance rouged. There were long pearls in his ears and under his left eye an enormous patch. His eyes slanted towards his nose, his nostrils curved upwards, and his thin lips were smiling.

Bowen has a good eye, but not always a good ear. She often falls back on adverbs to compensate for weak verbs:

"You have a very splendid painting swinging outside your own door," said Lord James suavely. "Never did I see fairer drawing nor brighter hues. It is your work?" he questioned.

"Mine, yes," assented the sign-painter drearily.

As the story develops, the few lapses in her style fade into the background, while the visual sense remains up front:

The bright dark eyes of the visitor flickered from right to left. He moved a little nearer the window, where, despite the thickening twilight, his violet silk coat gleamed like the light on a sheet of water....

She cast off her long earrings, her bracelets, her rings, the necklace Lord James had given her. This slipped, like a glitter of purple water, through her fingers, and shone in a little heap of stars on the gleaming waxed floor.

From beginning to end, Bowen maintains a tone of detached omniscience. This makes it impossible to read the story as a particpant, only as a spectator, but the compensations of visual detail make the spectacle worth seeing.

I also think she was right to keep the readers at a distance. The surprises of the plot depend on a detached perspective; allowing us into the heads of her characters would have undermined her best moments.

To say anything else would ruin the impact of a story that not only surprises, but develops a mood of quiet eeriness that creeped under my skin years ago when I first read it, and one that comes back to me with each new reading.

Published on August 16, 2019 07:27