Mark Fuller Dillon's Blog, page 15

October 28, 2020

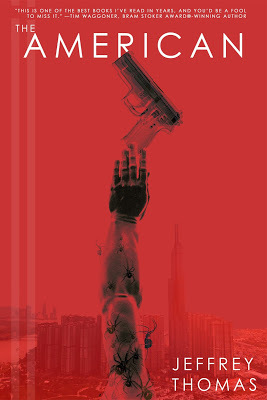

Scars, Bloody Wounds, Aches and Joys: THE AMERICAN

The American

, by Jeffrey Thomas.

The American

, by Jeffrey Thomas. Journalstone, 2020.

An honest review should balance the merits of a book against any weaknesses. Here, the weaknesses are almost buried by the power of the story and the fascination of the characters. Any book that keeps me turning the pages until five o'clock in the morning deserves my full attention; any book that shocks me and moves me in scene after scene deserves all the praise I can bring to it.

Let me start with praise.

At one point in the book, a thoroughly despicable character tries to justify his own evils:

"[He] had read somewhere that 4% of the population (in the US…or was it worldwide?) were sociopaths. That 1% were psychopaths. He wasn’t clear on the difference, but it was food for thought. It wasn’t an anomaly, he thought. It was a trend."In the past, human beings had relied on close groups to ensure their survival against the rigors of nature. Of nature’s harsh elements, of nature’s predatory -- or at least, competitive -- animals. Nature had required that humans bond together, create tribes, societies, cities and nations (and of course, the resultant aberrations of religions and political parties).

"But…wasn’t humanity beyond all that now? Survival was more assured, taken for granted. And hence: the evolution of a superior human. No longer inhibited by the bond to a tribe. A human freed of fearful loyalties, except the loyalty to oneself. To one’s own needs and urges."

In a modern world where the values of the marketplace have stamped out the values of human communities, this philosophy might carry weight, but in The American, Jeffrey Thomas brings out the necessity for bonds of family and friendship. Even in cities where murders are currency, where cold killings become tools of business, people still matter; they hang on, they work together to keep the world in one piece.

This focus on human compassion takes the book in directions that I had not anticipated. Against the temptation of a thriller to keep the plot simple, Thomas has chosen, instead, to emphasize meaning and a personal perspective. The horror of this book is undeniable, but so is the humanity; chapters that show the worst of human actions alternate with scenes of people at their best.

Thomas writes with a keen eye for landscapes -- not physical landscapes, but social. He knows how people interact in bars and offices, theme parks and morgues; he understands the ways in which families and friendships fall apart, and then come together again; he feels, in his gut, how the past can wound, and how -- unexpectedly, without warning -- the present can heal. This might sound abstract, but his approach to the story is relentlessly physical: pain and loss, community and reconcilation, are things that we can touch in this book. Thomas never shies away when a bullet shatters through an eye socket, but he also finds comfort in cold beer and hot soup, in Buddhist temples and christmas lights, in the stop-and-start exhilaration of high-speed motorcycles on jam-packed streets. Scars, bloody wounds, aches and joys, all come to life on the page.

Now for the criticism.

I suspect that most readers will have no trouble with the book's prose. Thomas knows what to say, and often writes with eloquence:

"[He] came to a glass-walled office in which Evelyn was housed behind her desk like a museum specimen representing her species.""Vietnam was full to the brim with beautiful women -- who knew better than Chen, who made his livelihood off that beauty in all its hunger and desperation? -- but this woman’s beauty was transcendent in a way that was hard to put a finger on. She emanated a deep, unarticulated misery that spoke of classical drama, beyond the scope of one person’s paltry life; a misery of the whole of human existence, no doubt beyond her own capacity for understanding. She was a mute and uncomprehending vessel of that suffering, like a small child with terminal cancer."

Elsewhere, just frequently enough to be noticed, the prose trips on itself, but seems not so much badly written as badly proof-read.

For example, in certain passages, when present participles gum up the prose and choke out the simple past tense, results precede actions:

"He slung her off him, grabbing hold of her tank top to do so.""'Indeed,' the American said, his laughter dying away."

"Thanh asked about their father, deciding to change the subject."

"Trenor couldn’t help but chuckle, finding it funny that here they were both amused now over the subject of Quan’s father’s demise."

Subjects and objects fade into obscurity:

"The madam’s laughter died away quickly, her expression darkening, but she knew better than to give in to her anger with this man.""The bloody garment tore away in his hands, leaving her thudding onto her back."

"He didn’t return the eye patch to his head, stuffing it into the pocket of his jacket."

"He nodded at Quan’s wallet, which he was just returning to a pocket in his fatigues."

When sentences break into fragments, they lose immediate clarity:

"Closer now, entering into another thrown pool of light."

Tacked-on qualifications intrude:

"Her eyes remained staring from her mask of blood, however."

Sometimes, the viewpoint characters alternate within a scene; this feels like having a door slammed on your face while a secret panel drops open at your feet.

A fast reader might skip over these flaws, a captivated reader might glance at them in passing, but I read slowly, for pleasure; I could feel these potholes jar the bones of my feet. In a book so compelling and so clear with its intentions, written by someone so obviously thoughtful, these flaws represent a failure to revise.

They might have crippled a lesser book, but this one kept me reading beyond every speedbump of language and technique. Its characters made me fear and hope for them; its narrative made me think about my own losses and my own moments of community. I can ask many things of a book, but above all, I want the book to seem alive. The American lives.

October 16, 2020

The Thing From Another World

Click on this image for a better jpeg.

Click on this image for a better jpeg.For all of its impact, and for all of the praise the film has won since it debuted, The Thing From Another World has been dogged by two persistent criticisms.

The first, I have to concede: in terms of concept, the film's "intellectual carrot" is a big step downwards from the shape-shifting alien of John W. Campbell's original story, and in visual terms, it brings to mind not so much a being from another planet as a variation on the Jack Pierce / Boris Karloff Frankenstein's monster. The makers of the film concealed this limitation as well as they could with stark shadows and camera set-ups; perhaps no one at the time could have filmed Campbell's monster convincingly. (Except for Willis O'Brien? I wish he had tried!)

The second criticism I find hard to accept. Many have argued that this film sets military "practicality" and force above scientific curiosity. For example, in the words of John Baxter:

"Typically for [producer Howard] Hawks the characters quickly separate themselves into professionals and dreamers. The airman, the reporter he takes with him and some of his crew are professionals; the scientists, and especially their leader, are dreamers. Hawks's contempt for the former comes out clearly in the various exchanges at the base, science and scientists generally shown as being incapable of adjusting to the real world."

-- Science Fiction in the Cinema, A. S. Barnes & Co, New York, 1970.

I have never seen this in the film. What I find, instead, is a nuanced opposition between a community of reason and flexible thought (a community of soldiers and scientists), and one authoritarian scientist who prefers to work alone within his own assumptions, who considers knowledge more important than communities or individual human beings.

This authoritarian scientist, Dr Carrington, begins with an argument that most of us would find reasonable, and which, in the context of the film, is undeniably true:

"When you find what you're looking for, remember it's a stranger in a strange land. The only crimes involved were those committed against it. It awoke from a block of ice, was attacked by dogs, shot by a frightened man. All I want is a chance to communicate with it."

Later in the film, however, when the Thing is revealed to be a possible biological threat to the world, Carrington goes beyond this argument to stress that human beings are expendable:

"We've only one excuse for existence: to think, to find out, to learn. It doesn't matter what happens to us. Nothing matters except our thinking. We've fought our way into Nature, we've split the atom... We owe it to the brain of our species to stay here and die, without destroying a source of wisdom. Civilization has given us orders."

Carrington has learned about the Thing by conducting experiments in secret. The other scientists, equally curious, have kept in mind reasonable precautions against too quick an investigation without proper safeguards. When Carrington proposes an immediate examination of the frozen Thing, Dr Chapman mentions the risk of contamination by germs from another planet, and the possible risk of damage to these alien remains by the atmosphere of Earth. Even the scientists eager to learn about the Thing right away come to disagree with Carrington when they realize the implications of the creature's biology; they join the soldiers and contribute to the fight. Carrington's assistant comes up with a method to destroy the Thing, and Dr Redding offers a refinement of this plan.

When the scientists warn Carrington that mental and physical exhaustion have clouded his judgement, he ignores them. Still, he does have a point: no effort has been made to find a means of communication. In the end, he puts his own life at risk to find such a means, but without endangering anyone else. For this, he earns the respect of the soldiers, even if they disagree with him. Carrington's flaw is not scientific curiosity, not "dreaming," as Baxter would say, but a refusal to see his own limitations, and a disregard for the community of his fellows.

In contrast, the military leader, Captain Hendry, shows concern for his men and for the scientists around him. When the men want his ear, he listens; when scientists object to his actions, he apologizes, explains that he must have military authority to act on their terms, and then he requests that authority by radio. He does the same with Ned Scott, the news reporter: he imposes a news blackout, but also requests permission for the news to be spread. Hendry never assumes that he knows best, but he keeps eyes and ears open to events as they develop; in that sense, he is more scientific than Carrington.

Carrington is willing to conduct experiments in secret; he leaps to conclusions, and then sticks to them ("Its development was not handicapped by emotional or sexual factors.... No pleasure, no pain, no emotion, no heart. Our superior in every way"), but Hendry is an open leader, dedicated to a task yet willing to accept new information and to improvise. Carrington sets knowledge above life and community; Hendry is determined to keep his community, military and scientific, alive.

This focus on community permeates the film, and might explain, in part, why critics rushed to pan the John Carpenter remake. The camaraderie and cooperation of the first film was tossed out in the second, for legitimate reasons: Carpenter wanted to convey the breakdown of a small group, not the cohesion. I believe the critics, very much like Dr Carrington, brought assumptions to their viewing of Carpenter's film that distorted their perspective. The Thing was not The Thing From Another World, and it should have been reviewed on its own terms, just as the original film should be considered by what it reveals on the screen, and not by the reductive implications that critics have imposed on it.

October 13, 2020

Flight From Complexity, Flight From Humanity

Even a fence might be fine if an endless variety of people could lean on it, to share some of the world's complexity, but instead I have noticed a relentless desire for simplification.

Whether people apply the structure of abstracted and schematized wolf packs to the complexities of human character, to end up writing about simplified "alpha males" or "beta females" as if these artificial categories could explain anything about our lives, or whether people reduce the mystery and fascination of a woman down to a mere number -- "She's an eight!" -- so much interaction on the Web has become a flight from complexity, a refusal to laugh and cry at just how beautifully messed-up we are as communities, countries, human beings.

Beyond the Web, we can find antidotes to simplification, cures that have long existed but are often disregarded in Web discussions. Personal experience is one cure, science is another, but I can think of something equally powerful.

Art is created for many reasons, often reasons hard to define, but one of its many benefits is a recognition and celebration of human complexity. Art reveals to us that human beings are bigger on the inside, more convoluted on the outside, than the Web often admits. Art can make demands on us, not through difficulty or lack of accessibility, but because art can steer us away from reduction.

In our complicated lives, art's reminders of just how much more complicated we are can be disturbing, perhaps even terrifying, but that is one of art's greatest beauties. We are not simplified diagrams; we are people, and people need art.

September 28, 2020

That Is All

There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book.

Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.

I would call Evelyn Waugh's The Loved One (1948) very well written --

The complete stillness was more startling than any violent action. The body looked altogether smaller than life-size now that it was, as it were, stripped of the thick pelt of mobility and intelligence. And the face which inclined its blind eyes towards him -- the face was entirely horrible; as ageless as a tortoise and as inhuman; a painted and smirking obscene travesty by comparison with which the devil-mask Dennis had found in the noose was a festive adornment, a thing an uncle might don at a Christmas party.

-- Well written, but almost sociopathically cruel. This cruelty has been yoked with humour so closely that every laugh (and the book incites constant laughter) makes me feel as if I were an accomplice to some crime against an innocent fictional character: Aimée Thanatogenos, whose only failing is that she is American and therefore much less bright than the British expatriate poet who lies to her, and then drives her to misery.

With Wilde's comment in mind, I feel that Waugh's book is more than justified by its prose, and since my teenage years, I have thought of it as one of the funniest books I know:

When as a newcomer to the Megalopolitan Studios he first toured the lots, it had strained his imagination to realize that those solid-seeming streets and squares of every period and climate were in fact plaster façades whose backs revealed the structure of bill-boardings. Here the illusion was quite otherwise. Only with an effort could Dennis believe that the building before him was three-dimensional and permanent; but here, as everywhere in Whispering Glades, failing credulity was fortified by the painted word.This perfect replica of an old English Manor, a notice said, like all the buildings of Whispering Glades, is constructed throughout of Grade A steel and concrete with foundations extending into solid rock. It is certified proof against fire, earthquake and Their name liveth for evermore who record it in Whispering Glades.

At the blank patch a signwriter was even then at work and Dennis, pausing to study it, discerned the ghost of the words "high explosive" freshly obliterated and the outlines of "nuclear fission" about to be filled in as substitute.

I still find a laugh on every page, but I now have greater admiration and respect for Ronald Firbank's The Flower Beneath The Foot, which is not only more funny, but which has the courage to recognize, in its haunting final words, the pain of despair.

September 26, 2020

Think Of The Reader, Dammit!

This might explain why so many authors write badly.

It also makes me wonder if the study of Latin and Greek was the secret advantage of yesterday's writers. When you force yourself to learn the grammar of another language, you find yourself drawn inevitably to think about the grammar of your own. For my part, I learned more about English when I studied German and French than I ever learned in English class; Greek and Latin could offer the same advantage, not only to writers, but to the reader who now stumbles along through the prickly vacant lots of too many stories.

Not Even Worth A Yawn

Then again, I can think of so many books and films and pieces of music that have made me want to crow from rooftops, jump around like a kid on christmas morning, rave at luckless girlfriends until their eyes roll up in their sockets, but to the world at large, these things I love are not even worth a yawn.

I have never understood this, and my failure gnaws at me.

One-Track Spine

September 18, 2020

Vast And Cool, Yet Sympathetic

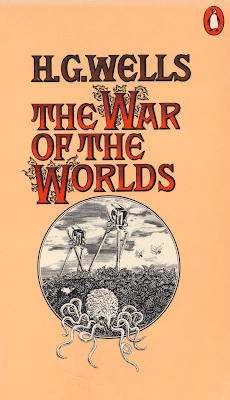

Cover by Harry Willock, 1971. Click for a better jpeg.

Cover by Harry Willock, 1971. Click for a better jpeg.When I revisit favourite stories of the past, nostalgia never molds me. I assess everything now by whatever standards I have learned to use, and for this reason, many old favourites no longer speak to me. Still, many do, and some of them expand when revisited, to show more facets and more nuance than I had seen before.

I first read The War of the Worlds when I was nine years old; reading it now, I feel the same pleasure of discovery. I could write about its layers of theme: about its unsettling idea that natural selection will continue within a technological society, when our machines become the environments to which we adapt; about ecological succession, and the changing of the biosphere by invasive, opportunistic species; about the parallels between Martian colonists and British imperialism, conveyed not by satire, but by analogy; about the failure of a bourgeois society to anticipate the shocks and upheavals of the future that plunges toward them.

These concepts are presented in the book not merely in subtext, but by explication; they add a troubling richness that goes beyond mere story-telling. For my purposes, however, I want to look at the story, because here, in his narrative techniques, Wells has achieved remarkable things.

The War of the Worlds is not presented as a novel, but as a romance. This liberates the story from the baggage of a novel's emphasis on characterization, and gives the book a drive, a momentum, that most novels could never match. All we know of the protagonist's life before the story begins is that he writes philosophical essays, and this is all we need to know; what matters more than background, here, is what the character thinks, feels, and does.

Instead of giving details about the narrator's past, Wells puts us inside the narrator's mind. We experience what he sees and fears; the result is an immersion into the storm-lit clarity of nightmare:

Flashes of actual flame, a bright glare leaping from one to another, sprang from the scattered group of men. It was as if some invisible jet impinged upon them and flashed into white flame. It was as if each man were suddenly and momentarily turned to fire.

Then, by the light of their own destruction, I saw them staggering and falling, and their supporters turning to run.

I stood staring, not as yet realising that this was death leaping from man to man in that little distant crowd. All I felt was that it was something very strange. An almost noiseless and blinding flash of light, and a man fell headlong and lay still; and as the unseen shaft of heat passed over them, pine trees burst into fire, and every dry furze bush became with one dull thud a mass of flames. And far away towards Knaphill I saw the flashes of trees and hedges and wooden buildings suddenly set alight.

It was sweeping round swiftly and steadily, this flaming death, this invisible, inevitable sword of heat. I perceived it coming towards me by the flashing bushes it touched, and was too astounded and stupefied to stir. I heard the crackle of fire in the sand pits and the sudden squeal of a horse that was as suddenly stilled. Then it was as if an invisible yet intensely heated finger were drawn through the heather between me and the Martians, and all along a curving line beyond the sand pits the dark ground smoked and crackled.

Wells maintains this dreamlike mood even during the speculations about Martian biology, and he makes the lectures as compelling as the dangers. These lectures never stop the story, because they retain the vividness and foreboding of the story itself.

One secret of this clarity is the reliance on physical details and visual impressions, even during the lectures. Wells could have mired himself in abstraction, but his love for the tactile, his passion for the everyday world around him, brings to life his creatures from another world.

We men, with our bicycles and road-skates, our Lilienthal soaring-machines,our guns and sticks and so forth, are just in the beginning of the evolution that the Martians have worked out. They have become practically mere brains, wearing different bodies according to their needs just as men wear suits of clothes and take a bicycle in a hurry or an umbrella in the wet. And of their appliances, perhaps nothing is more wonderful to a man than the curious fact that what is the dominant feature of almost all human devices in mechanism is absent -- the wheel is absent; among all the things they brought to earth there is no trace or suggestion of their use of wheels.... Almost all the joints of the machinery present a complicated system of sliding parts moving over small but beautifully curved friction bearings. And while upon this matter of detail, it is remarkable that the long leverages of their machines are in most cases actuated by a sort of sham musculature of the disks in an elastic sheath; these disks become polarised and drawn closely and powerfully together when traversed by a current of electricity. In this way the curious parallelism to animal motions, which was so striking and disturbing to the human beholder, was attained. Such quasi-muscles abounded in the crablike handling-machine which, on my first peeping out of the slit, I watched unpacking the cylinder. It seemed infinitely more alive than the actual Martians lying beyond it in the sunset light, panting, stirring ineffectual tentacles, and moving feebly after their vast journey across space.

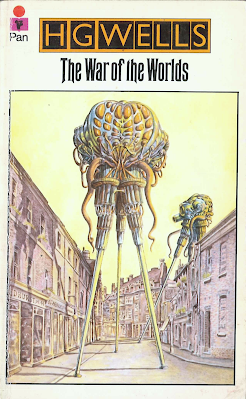

Cover by George Underwood, 1975. Click for a better jpeg.

Cover by George Underwood, 1975. Click for a better jpeg.

Wells presents his concepts, makes analogies, links the strangeness of his war to scenes and habits of everyday life, to things that we can touch and see. His concepts drive the plot, from the effect of Martian weapons on terrified human beings, to the ecological rise and fall of the Red Weed -- a cycle of robust growth followed by infection and ruin, with hints of what lies in store for the Martians. At the same time, his intense focus on the psychological storms of the narrator anticipates the methods of William Sansom and J. G. Ballard, who would also emphasize a stripped-down, clinically physical approach to their characters.

In its power and economy of means, The War of the Worlds can remind readers that other methods are available for science fiction, and that, in abandoning the streamlined forms of romance for the bloated realism of the novel, science fiction lost a compelling way to tell stories. Less is often more, and a sharp focus often reveals finer details than are seen by a panoramic view. For this argument, Wells provides a living set of reasons.

September 7, 2020

"Halt!" she squaloured spasmosidlingly.

Then again, at certain moments, a character might shout or whisper, and this information can be useful in the text.

In very few cases will "to say" need an adverb. The context of a scene, and the wording of the dialogue, tend to make adverbs pointless at best and noisy at worst. Never waste time by having a character say anything queryingly, querulously, quaveringly, callously, carelessly, combatively, or contumaciously, when attention might be better spent on making the character say something worth a font.

August 21, 2020

Monsters on Asphalt

Yesterday, after sunset, I walked through a local neighbourhood of well-maintained split-level houses on a hill above dense forest. The night was warm and slightly humid, the streets were quiet, and rabbits were out in full hordes.

On one street, I came across a line of cartoon figures drawn across the asphalt, barely visible in the gleam of a street lamp. They stood under a heading reinforced by emphatically multiple strokes of yellow chalk: 1738.

Many of the figures (Pat, for one) were childishly vague, but Will, at the centre, stood out because of his elaborate ski toque.

On the far left of the line was Coco, whose boneless, wavey arms extended far beyond the length of his body. One arm rippled like a banner above his head, the other sagged like a dead tentacle at his feet. What impressed me was that Coco had managed to find a long-sleeved shirt to fit him.

If Coco had long arms, then Lila had four arms. Not even her lobster-claw hands could reduce the impact of her severely-squinting eyes.

On the right end of the line stood a pair of much smaller beings with what looked like pointed ears, or perhaps pointed haircuts. A curved line ran below them to connect all the figures, and below that was the question, Which is your favourite?

Hard to say. All I could think was that I used to spend Saturday nights with my loving and sensual girlfriend, but now I was more likely to spend my time staring at monsters on asphalt.