Mark Fuller Dillon's Blog, page 30

July 3, 2017

The Smell of Yesterday's Blood

When I say that horror is not a genre, but a mood, a suspicion, a perspective, I assert this not to condemn genre, but to recognize that the qualities I love in one type of story can often be found in unexpected form elsewhere.

To give one example: here is a passage from an Isaac Babel story, "Crossing into Poland."

"The commander of the VI division reported: Novograd-Volynsk was taken at dawn today. The Staff had left Krapivno, and our baggage train was spread out in a noisy rearguard over the highroad from Brest to Warsaw built by Nicholas I upon the bones of peasants.

"Fields flowered around us, crimson with poppies; a noon-tide breeze played in the yellowing rye; on the horizon virginal buckwheat rose like the wall of a distant monastery. The Volyn's peaceful stream moved away from us in sinuous curves and was lost in the pearly haze of the birch groves; crawling between flowery slopes, it wound weary arms through a wilderness of hops. The orange sun rolled down the sky like a lopped-off head, and mild light glowed from the cloud gorges. The standards of the sunset flew above our heads. Into the cool of evening dripped the smell of yesterday's blood, of slaughtered horses. The blackened Zbruch roared, twisting itself into foamy knots at the falls. The bridges were down, and we waded across the river. On the waves rested a majestic moon. The horses were in to the cruppers, and the noisy torrent gurgled among hundreds of horses' legs. Somebody sank, loudly defaming the Mother of God. The river was dotted with the square black patches of the wagons, and was full of confused sounds, of whistling and singing, that rose above the gleaming hollows, the serpentine trails of the moon."

[From The Collected Stories, edited and translated by Walter Morison. Meridian Books, 1960.]

Everything I love in horror fiction can be found here: similes that convey unease ("like a lopped-off head"), vividly-evoked settings full of troubling details ("the smell of yesterday's blood, of slaughtered horses"), metaphors that suggest an uncanny threat or process ("the serpentine trails of the moon").

But do these details (and grimmer ones to come) make this a horror story?

One response would be to say, "Horrific matter, horrific moods, make a story horror." I can understand this, and I'm tempted to agree with it. But I'm also tempted to say that what we normally consider horror fiction is just one small group of stories within a larger framework that acknowledges the power and presence of a mood. Horror is an inescapable aspect of life; it is not limited to a genre.

How you feel about this, and whether you agree or disagree, will depend on your own perspective, and I wouldn't have it any other way. But from my point of view, this ambiguity, this uncertainty, implies a freedom to explore the nuances of a mood without limitations of style or content or expectation. Not only is the road wide open, but there are many roads, and they all veer off towards a storm-cloud horizon without fences and without maps.

Published on July 03, 2017 10:20

June 16, 2017

Hoarded Life And Beauty

More thoughts on Walter de la Mare, and on the difficulty of expressing how a story works....

In my slice of the world beyond the internet, I am surrounded by readers, but no one else in my life reads horror fiction. I often wonder if people find it foreign, inaccessible.

Both H. E. Bates and Seán Ó Faoláin have argued that modern short stories are closer in impact and scope to lyric poetry than to plays or novels. I concede their point, and I would call it even more true for horror stories, where causes are often unclear, where effects can be vivid but inexplicable, and where consequences are often left to implication.

Because of their kinship with poems, horror stories can be hard to describe, and their impact can be hard to understand. Why do they often work so powerfully? We might as well ask why a poem works. We can examine a poem's techniques, metaphors, and imagery, but by the time the sun has gone down, we are left in the dark with a piece of writing that cannot be paraphrased. The only way to grasp its effect is to read it from beginning to end.

One of the fascinations of Walter de la Mare's short fiction is that it relies even more than most on these elusive "poetic" qualities. Yes, the plots can be taken apart, the prose can be analyzed, but the lingering effect is more akin to the ripples of a dream. This makes it easy to enjoy, but hard to describe and even harder to recommend.

A case in point: again, "The Tree," from 1922.

I have read the story five times, now, and each reading has made it more disturbing. I believe I understand its meaning, or at least one of its meanings; these are for you to find on your own. But the power of the story goes beyond this rational awareness of what (in part) it seems to imply.

If a story like this cannot be paraphrased, then how can it be reviewed? One solution would be to describe the plot:

"A wealthy fruit merchant pays an angry visit to his half-brother, an artist whom he considers a lazy good-for-nothing parasite. But the merchant is uneasy about seeing, once again, the almost-alien tree that has become an obsession for the artist."

What would this tell you? Not much. Would it compel you to read the story? Most likely not, because it fails to give you any sense of how the story might actually feel as you read it.

But if I were to quote from it, at length?

...This old man, shrunken and hideous in his frame of abject poverty, his arms drawn close up to his fallen body, worked sedulously on and on. And behind and around him showed the fruit of his labours. Pinned to the scaling walls, propped on the ramshackle shelf above his fireless hearthstone, and even against the stale remnant of a loaf of bread on the cracked blue dish beside him, was a litter of pictures. And everywhere, lovely and marvellous in all its guises -- the tree. The tree in May’s showering loveliness, in summer’s quiet wonder, in autumn’s decline, in naked slumbering wintry grace. The colours glowed from the fine old rough paper like lamps and gems.

There were drawings of birds too, birds of dazzling plumage, of flowers and butterflies, their crimson and emerald, rose and saffron seemingly shimmering and astir; their every mealy and feathery and pollened boss and petal and plume on fire with hoarded life and beauty. And there a viper with its sinuous molten scales; and there a face and a shape looking out of its nothingness such as would awake even a dreamer in a dream....

And at that moment, as if an angry and helpless thought could make itself audible even above the hungry racketing of mice and the melancholic whistling of a paraffin lamp -- at that moment the corpse-like countenance, almost within finger-touch on the other side of the table, slowly raised itself from the labour of its regard, and appeared to be searching through the shutter’s cranny as if into the Fruit Merchant’s brain. The glance swept through him like an avalanche. No, no. But one instantaneous confrontation, and he had pushed himself back from the impious walls as softly as an immense sack of hay.

These were not eyes -- in that abominable countenance. Speck-pupilled, greenish-grey, unfocused, under their protuberant mat of eyebrow, they remained still as a salt and stagnant sea. And in their uplifted depths, stretching out into endless distances, the Fruit Merchant had seen regions of a country whence neither for love nor money he could ever harvest one fruit, one pip, one cankered bud. And blossoming there beside a glassy stream in the mid-distance of far-mountained sward -- a tree.

We can break a story into pieces, scan it with a microscope, and learn a lot about the craft of writing. What we cannot describe, what we can only experience in privacy, is the effect of a story as a whole, because, again, like a poem, a story can be impossible to paraphrase.

And so, for my part, I would rather avoid many details of plot; I would rather let people see a long and characteristic section of prose, because this, at least, would give people some idea of how reading the story might feel.

If you have any thoughts on this, I would love to hear them!

Published on June 16, 2017 05:20

May 31, 2017

A Limitation of Filming

A counter-argument to my previous post.

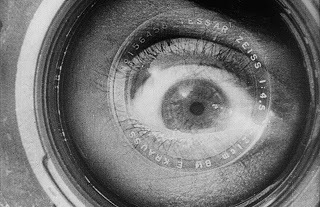

One limitation of imagery in film is that it can be comprehensible at first glance.

Of course, camera trickery like fade-ins or blurring can delay comprehension, as in the flashback sequence from Once Upon a Time in the West, or a deeply subjective viewpoint can be used to present initial confusion, as in the David Lynch adaptation of Dune, when Duke Leto, dying, mistakes another person for the Baron Harkonnen. But I suspect most audiences would recognize these tricks as unusual methods of presentation in a medium otherwise more suited to clarity -- even if that clarity shows unusual perspectives or juxtapositions, as in Vertov's Man With A Movie Camera.

In writing, by contrast, a subjective impression can be built clause by clause, and because narratives often rely on subjective points of view, the readers do not feel any need to reject the method as a contrivance.

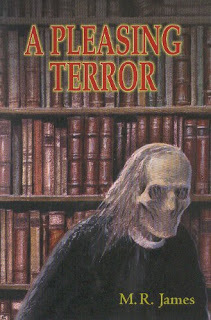

My favourite example of this gradual build-up by subjective impressions can be found in a story by M. R. James, "Mr Humphreys and His Inheritance":

One limitation of imagery in film is that it can be comprehensible at first glance.

Of course, camera trickery like fade-ins or blurring can delay comprehension, as in the flashback sequence from Once Upon a Time in the West, or a deeply subjective viewpoint can be used to present initial confusion, as in the David Lynch adaptation of Dune, when Duke Leto, dying, mistakes another person for the Baron Harkonnen. But I suspect most audiences would recognize these tricks as unusual methods of presentation in a medium otherwise more suited to clarity -- even if that clarity shows unusual perspectives or juxtapositions, as in Vertov's Man With A Movie Camera.

In writing, by contrast, a subjective impression can be built clause by clause, and because narratives often rely on subjective points of view, the readers do not feel any need to reject the method as a contrivance.

My favourite example of this gradual build-up by subjective impressions can be found in a story by M. R. James, "Mr Humphreys and His Inheritance":

"The main occupation of this evening at any rate was settled. The tracing of the plan for Lady Wardrop and the careful collation of it with the original meant a couple of hours’ work at least. Accordingly, soon after nine Humphreys had his materials put out in the library and began. It was a still, stuffy evening; windows had to stand open, and he had more than one grisly encounter with a bat. These unnerving episodes made him keep the tail of his eye on the window. Once or twice it was a question whether there was -- not a bat, but something more considerable -- that had a mind to join him. How unpleasant it would be if someone had slipped noiselessly over the sill and was crouching on the floor!

"The tracing of the plan was done: it remained to compare it with the original, and to see whether any paths had been wrongly closed or left open. With one finger on each paper, he traced out the course that must be followed from the entrance. There were one or two slight mistakes but here, near the centre, was a bad confusion, probably due to the entry of the Second or Third Bat. Before correcting the copy he followed out carefully the last turnings of the path on the original. These, at least, were right; they led without a hitch to the middle space. Here was a feature which need not be repeated on the copy -- an ugly black spot about the size of a shilling. Ink? No. It resembled a hole, but how should a hole be there? He stared at it with tired eyes: the work of tracing had been very laborious, and he was drowsy and oppressed.... But surely this was a very odd hole. It seemed to go not only through the paper, but through the table on which it lay. Yes, and through the floor below that, down, and still down, even into infinite depths. He craned over it, utterly bewildered. Just as, when you were a child, you may have pored over a square inch of counterpane until it became a landscape with wooded hills, and perhaps even churches and houses, and you lost all thought of the true size of yourself and it, so this hole seemed to Humphreys for the moment the only thing in the world. For some reason it was hateful to him from the first, but he had gazed at it for some moments before any feeling of anxiety came upon him; and then it did come, stronger and stronger -- a horror lest something might emerge from it, and a really agonizing conviction that a terror was on its way, from the sight of which he would not be able to escape. Oh yes, far, far down there was a movement, and the movement was upwards -- towards the surface. Nearer and nearer it came, and it was of a blackish-grey colour with more than one dark hole. It took shape as a face -- a human face -- a burnt human face: and with the odious writhings of a wasp creeping out of a rotten apple there clambered forth an appearance of a form, waving black arms prepared to clasp the head that was bending over them."

Published on May 31, 2017 08:42

May 30, 2017

A Limitation of Writing

In the film

Storks

, two characters who have spent the entire movie jousting verbally with each other find themselves in happier circumstances. One begins to joust again; the other says nothing, but merely nods -- a beautiful moment, beautifully subtle. The silent image by itself conveys a new emotion.

In Psycho , Norman Bates leans over to stare at the motel's guest ledger, and the unusual angle on his face, the chewing motions of his jaw, the deep shadows, turn him into something unrecognizably strange.

In Zootopia , Nick Wilde wears a shirt that matches the wallpaper of his childhood home; in his pocket, he carries his Ranger Scout kerchief. No one ever points out these hints of lingering sadness, but they become as obvious as old scars.

In a Tony Mitchell article from 1982, "Tarkovsy in Italy," the

Films can reveal such details without comment, but in a story, they must be spelt out; they must be made obvious, which robs them of any magic we might feel in a chance encounter. An aching limitation.

In Psycho , Norman Bates leans over to stare at the motel's guest ledger, and the unusual angle on his face, the chewing motions of his jaw, the deep shadows, turn him into something unrecognizably strange.

In Zootopia , Nick Wilde wears a shirt that matches the wallpaper of his childhood home; in his pocket, he carries his Ranger Scout kerchief. No one ever points out these hints of lingering sadness, but they become as obvious as old scars.

In a Tony Mitchell article from 1982, "Tarkovsy in Italy," the

Films can reveal such details without comment, but in a story, they must be spelt out; they must be made obvious, which robs them of any magic we might feel in a chance encounter. An aching limitation.

Published on May 30, 2017 08:46

April 23, 2017

There Is No Time, There Is No Time

If

Arrival

were a heist film....

A master criminal, the Boss, wants to crack the safe in the Gorgonzola Bank. The film opens with a planning session.

THE BOSS: All right, you lugs, listen up. As you can see on this diagram, the safe is in a lead-walled room, surrounded by a moat, surrounded by an electric fence, surrounded by a pit of crocodiles, surrounded by laser cannons, surrounded by a troupe of deadly circus mimes.

LUG: Boss, we'll never get in there!

Suddenly, the Boss and his lugs are standing before the safe.

LUG: But Boss, how did we--?

THE BOSS: There is no time, I have to figure out this combination. There is no time, there is no time, there is no time --

LUG: Boss, what are you doing?

THE BOSS: I'm applying the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis to alter my perception. There is no time, there is no time, there is no time --

Suddenly, the Boss finds himself at a fancy party, in the presence of Lon Gorgonzola, the banker.

GORGONZOLA: Even after all these years, I'm still amazed that you could just walk in there, spin the combination, and get it right on your first try. 7-7-7-4, just like that. How did you guess?

The Boss is back with his lugs before the safe.

THE BOSS: 7-7-7-4. And walla! The safe is opened!

LUG: What?!? How?!?

THE BOSS: It's amazing what language can do for you.

LUG: That's ridiculous!

THE BOSS: I don't perceive it as ridiculous. I perceive it as big-budget science fiction.

A master criminal, the Boss, wants to crack the safe in the Gorgonzola Bank. The film opens with a planning session.

THE BOSS: All right, you lugs, listen up. As you can see on this diagram, the safe is in a lead-walled room, surrounded by a moat, surrounded by an electric fence, surrounded by a pit of crocodiles, surrounded by laser cannons, surrounded by a troupe of deadly circus mimes.

LUG: Boss, we'll never get in there!

Suddenly, the Boss and his lugs are standing before the safe.

LUG: But Boss, how did we--?

THE BOSS: There is no time, I have to figure out this combination. There is no time, there is no time, there is no time --

LUG: Boss, what are you doing?

THE BOSS: I'm applying the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis to alter my perception. There is no time, there is no time, there is no time --

Suddenly, the Boss finds himself at a fancy party, in the presence of Lon Gorgonzola, the banker.

GORGONZOLA: Even after all these years, I'm still amazed that you could just walk in there, spin the combination, and get it right on your first try. 7-7-7-4, just like that. How did you guess?

The Boss is back with his lugs before the safe.

THE BOSS: 7-7-7-4. And walla! The safe is opened!

LUG: What?!? How?!?

THE BOSS: It's amazing what language can do for you.

LUG: That's ridiculous!

THE BOSS: I don't perceive it as ridiculous. I perceive it as big-budget science fiction.

Published on April 23, 2017 10:54

April 6, 2017

One Bad Sonnet

Please point out any badly-chosen word,

My lapses of technique, my tortured form.

You say you have a knowledge of the norm,

And yet, your silence is the broadside heard.

Your criticism, welcomed for a third

And most emphatic time, would not deform

The growth of my intention. If a storm

Is what you have to offer, then be stirred.

Clay might froth and slide beneath a spate,

But deeper seeds take root, and they survive.

Rolling warps the structure of the skelp,

But bending brings a needed change of state.

Your promises of old remain alive;

A critic who says nothing is no help.

Let's take this dead thing apart to see how it died.

Although it is, in formal terms, a legitimate Petrarchan sonnet, and although its octave does rely on trochees and enjambment to break up the sing-song patterns of iambic pentameter, the sestet does not; as a result, the language on the whole seems rigid, stillborn.

This dead feeling is reinforced by a lack of concrete verbs. "Froth and slide" is not bad, but none of the other verbs brings imagery or texture to mind. For this reason, the sonnet feels less like a poem than a series of abstract statements.

As you can see, I'm no critic, but even I can spell out the flaws in a chunk of bad verse. As you can also see, I welcome criticism. I thrive on it. The one thing I cannot handle is the silence of those who promised to take my work apart, and then said nothing.

Published on April 06, 2017 23:09

April 5, 2017

Laconicism Cultivated and Applied

The fewest words can take us to the furthest point.

Laconicism, cultivated and applied,

Can lubricate creative will that pain has dried,

Bring purpose to the drifting dust, make yawns aroint.

Many would prefer to let the dull injoint

A lack of passion to a standard calcified,

But reader, let your energy be magnified:

Drag out the lords of tedium to disanoint.

Laconicism, cultivated and applied,

Can lubricate creative will that pain has dried,

Bring purpose to the drifting dust, make yawns aroint.

Many would prefer to let the dull injoint

A lack of passion to a standard calcified,

But reader, let your energy be magnified:

Drag out the lords of tedium to disanoint.

Published on April 05, 2017 14:03

April 4, 2017

Without You

Without you, I bring only half a voice:

The weaker half that dreams, or spins a tale;

The half that speaks in text and rhyme; the pale

And charmless remnant stuck without a choice

Of harmonies for singing, to rejoice

In double meaning or in shared wassail;

The broken sound of someone who must flail

Through metaphors of charcoal and turquoise.

Without your public half, I am adrift

When faced by numbers in a happy crowd,

While greeting strangers on the road of night.

Mute before the many, with no gift

For pleasantries or pleasing talk, aloud

I lack your sociability and light.

The weaker half that dreams, or spins a tale;

The half that speaks in text and rhyme; the pale

And charmless remnant stuck without a choice

Of harmonies for singing, to rejoice

In double meaning or in shared wassail;

The broken sound of someone who must flail

Through metaphors of charcoal and turquoise.

Without your public half, I am adrift

When faced by numbers in a happy crowd,

While greeting strangers on the road of night.

Mute before the many, with no gift

For pleasantries or pleasing talk, aloud

I lack your sociability and light.

Published on April 04, 2017 10:43

March 23, 2017

Glider Panic

I would rather do anything else than write this, and so, of course, I'll write.

Early on Wednesday, I felt isolated, insecure, and this prompted me to glance at the Facebook page of my last girlfriend. Because we are no longer friends, most of her page is hidden to me, but I did notice a new collection of photographs devoted to a March blizzard, one severe enough to stop all travelers, except for her "champion," the man she loves.

Then I felt as I once did when I was in a glider, caught in a wild thermal, carried higher and higher as the pilot beside me struggled to bring us back to the ground. Far below us, a plowed field was losing its topsoil to the wind, and the column of its loss rose like a volcanic plume, gone forever into the sky.

I had always known that she would find someone else, because a woman like her had so much to offer to any man with eyes and emotions. I also knew that her happiness mattered to me, that I would never want for her to be alone. I knew these things, but I still felt that glider panic, I still saw that loss to the sky.

Then I realized that Facebook had not brought me to her page, but to a choice of pages from women who shared her name. This woman and her champion of the blizzard live in Québec, while my last girlfriend lives on the other side of the continent.

But for the rest of the day, and for the night that followed, I still felt as if I were caught in that unforgiving sky. Even if she has nobody now, the odds are good that she will again, someday.

And if that is what she wants, then that is what I want for her. The whole point of her leaving was to follow her needs of the heart, and to find what she could never find with me. She gave me the happiest years of my life, and I would never deny her a chance to find similar years of her own.

I only wish the ground were not so far away.

Early on Wednesday, I felt isolated, insecure, and this prompted me to glance at the Facebook page of my last girlfriend. Because we are no longer friends, most of her page is hidden to me, but I did notice a new collection of photographs devoted to a March blizzard, one severe enough to stop all travelers, except for her "champion," the man she loves.

Then I felt as I once did when I was in a glider, caught in a wild thermal, carried higher and higher as the pilot beside me struggled to bring us back to the ground. Far below us, a plowed field was losing its topsoil to the wind, and the column of its loss rose like a volcanic plume, gone forever into the sky.

I had always known that she would find someone else, because a woman like her had so much to offer to any man with eyes and emotions. I also knew that her happiness mattered to me, that I would never want for her to be alone. I knew these things, but I still felt that glider panic, I still saw that loss to the sky.

Then I realized that Facebook had not brought me to her page, but to a choice of pages from women who shared her name. This woman and her champion of the blizzard live in Québec, while my last girlfriend lives on the other side of the continent.

But for the rest of the day, and for the night that followed, I still felt as if I were caught in that unforgiving sky. Even if she has nobody now, the odds are good that she will again, someday.

And if that is what she wants, then that is what I want for her. The whole point of her leaving was to follow her needs of the heart, and to find what she could never find with me. She gave me the happiest years of my life, and I would never deny her a chance to find similar years of her own.

I only wish the ground were not so far away.

Published on March 23, 2017 00:59

March 14, 2017

A Cause for Cerebration

Late on Sunday night, to celebrate my birthday, I watched "The Inheritors" again, which is my favourite episode from the second season of

The Outer Limits

. And yes, I did cry at the end.

I finished watching at 4:30 AM, then stepped from my darkened bedroom to the bathroom, where the fluorescent light seem unusually brilliant. When I returned to my computer to write notes on the episode, I found the monitor partially blocked by a dazzling white retinal afterimage. I tried to work around it, but its intensity increased: an effect I had never seen before.

Within a few minutes the afterimage became a white starburst pattern with a violet fringe, and it began to flicker like a strobe lamp. I closed one eye, then the other, and found a similar strobing in each. The flickering intensified.

At this point, I began to worry. In the bathroom, I peered at my eyes in the mirror, raised my arms above my head, stuck out my tongue, spoke aloud. In the hallway, I balanced on one leg, and then on the other: no problem. Then I recalled descriptions my father had told me about migraine auras; they had plagued him, now and then. I had never had migraines in my life, and had no interest in starting. Worry swelled into fear.

I called the Québec emergency health hotline. As I described my symptoms, the starburst drifted leftward until it was nothing more than a flickering rim at the edge of sight. Within less than a minute, the effect was gone. "I've never experienced anything like this."

The man on the other line went to consult with staff; when he came back, he said, "Get to an emergency room, right now."

And so, at five o'clock in the morning, unshaven and frozen, I waited outside in the cold white moonlight for a taxi.

The driver was a friendly bald man with an opaquely slavic accent; he had been driving taxis for 22 years. "I am not rich," he said, "But I am there for my children. One must always be there for one's children."

At the Gatineau hospital, where I go to have my blood tested for its coagulation levels, I arrived at 6:30, still in darkness. I had no idea how to say "afterimage" in French, and so the nurses found my descriptions baffling.

After two hours in the waiting room (where an old man snored like a faulty jet engine), I spoke with a Dr. Bonneville. He took me through the standard procedure to find any symptoms of stroke, but I was able to follow his moving finger, see his moving hands with peripheral vision, touch my nose with both hands at the same time, and so on. No indication of stroke.

When I told him that I was on Coumadin for my blood clot, he gave me a grim look and said, "There's a problem with Coumadin: it makes you bleed." He spoke about one patient who, like me, had never experienced these visual phenomena before. The cause? Bleeding in the brain.

I must have turned pale. "Was he... all right?"

"Yes, he was fine; the bleeding was minor. And the chances of your having this condition are small. But all the same...."

When he left the room to call a neurologist, I stared at the probes and the tubes on the walls and did what I could to assure myself that my bleeding, too, was minor. By now it was 9:00 in the morning, I had not eaten since midnight, and I was also worried about hypoglycaemia.

The doctor came back, and told me that I was going to be transferred to another hospital for a CAT scan and a meeting with the neurologist at 2:00; the only drawback was that I would have to fast until the procedure was completed. I looked at the clock on the wall: four hours to wait without food, but what the hell. "I can handle that."

After blood tests and a long wait to see if the scan could be scheduled, a nurse put a shunt in my arm, and the staff paid a taxi driver to take me to the Hull Hospital, which happens to be less than a half-hour walk from my apartment building.

The driver was friendly, Muslim, and certain that he would no longer visit the United States. "Trump didn't win," he said, "Hillary lost. And I'm glad she lost." We went on to discuss her foreign policy record, and Trump's political pandering. By the time we arrived at the Hull hospital, we were both happy to be Canadians.

I was able to complete the scan half an hour before my appointment with the neurologist. The scan technician was helpful: she took me through each new step of the procedure before she acted. "Now I'm going to cross over to the other side, and inject the iodine." This made my head feel as if I were trapped under a sun lamp. The deep droning whir of the scanner made me think of a magnetic maelstrom.

Afterwards, when I took off the hospital robe to put my shirt back on, the gruff (but not unlikeably gruff), white-haired woman who ran the department said to me, "The changing booth is over there. This is not a changing room, this is my personal workspace."

I smiled and apologized. The old man waiting beside me for a scan said, "Don't worry about me, I'm not offended!"

An hour later, while I waited in the neurologist's office, I noticed a pair of threatening machines that looked like grinding or sharpening tools from a metal shop. I went up for a closer look; as far as I could tell, they were dental equipment.

The neurologist, Dr. Gagnon, came into the room at a rapid pace. A short, round-faced man with a comical moustache, he greeted me in French and began to talk about my symptoms.

"Pardonnez-moi," I said, "mais je manque un vocabulaire quotidien...."

He laughed, rolled his chair up to a computer monitor, and spoke in perfectly fine English with an accent I could not place -- German? Swiss?

"You've had your scan? Let's take a look at it." As he opened images on the monitor, I feared the worst.

"What we have here is -- oh, pardon me, that's my call." He answered the cell phone, stood up, left the room, and left me seated there. I began to fear the worse than worst.

When he came back after several minutes of worst, I said, in my horrible French, "I was here on the edge of panic, and then your phone rang...."

He laughed loudly and happily: "I love that!"

Then he displayed the scanned images in sequence, which made them look like a cartoon trip through a skull. I felt the strangeness that hits you when you peer at your own brain.

"Ah," he said. "I'm not worried for you. Everything here is the way it should be."

"Can this really show if something's wrong?"

"Oh, yes. It would show us tumours, blood clots --"

"And bleeding?"

"Oh, yes, bleeding too. But there's no sign of anything like that. And see this? Your vertebrae, aorta, they all seem fine. I'm not worried for you."

He explained that what I had seen had been a surge through the visual cortex, an aura without migraine. When people who have never experienced one before suddenly see an aura, doctors need to know the cause. And given my father's migraines, I had been wise to have this checked.

"If you go through this again, don't worry. Just let it pass. You should only be concerned if it leads to headaches or any other violent symptoms, or if it lasts for more than sixty minutes."

And so, nine-and-a-half hours after I had been dropped off at the first hospital, feeling weak, now, but not horrendously hypoglycaemic, I walked home on a bright and very cold afternoon. I thought about brains, about what can harm them, and I noticed all the cars around me, all the dangerous intersections, all the spots of ice on the sidewalk. I had been looking forward to biking season, and of course I always wore a helmet, but would a helmet really save me, if...?

Then I breathed in cold air, looked at the clear, cold sky, and reminded myself that Dr. Gagnon had shown me a healthy brain. This had to count for something. This had to be a cause not only for cerebration, but for celebration, too.

I finished watching at 4:30 AM, then stepped from my darkened bedroom to the bathroom, where the fluorescent light seem unusually brilliant. When I returned to my computer to write notes on the episode, I found the monitor partially blocked by a dazzling white retinal afterimage. I tried to work around it, but its intensity increased: an effect I had never seen before.

Within a few minutes the afterimage became a white starburst pattern with a violet fringe, and it began to flicker like a strobe lamp. I closed one eye, then the other, and found a similar strobing in each. The flickering intensified.

At this point, I began to worry. In the bathroom, I peered at my eyes in the mirror, raised my arms above my head, stuck out my tongue, spoke aloud. In the hallway, I balanced on one leg, and then on the other: no problem. Then I recalled descriptions my father had told me about migraine auras; they had plagued him, now and then. I had never had migraines in my life, and had no interest in starting. Worry swelled into fear.

I called the Québec emergency health hotline. As I described my symptoms, the starburst drifted leftward until it was nothing more than a flickering rim at the edge of sight. Within less than a minute, the effect was gone. "I've never experienced anything like this."

The man on the other line went to consult with staff; when he came back, he said, "Get to an emergency room, right now."

And so, at five o'clock in the morning, unshaven and frozen, I waited outside in the cold white moonlight for a taxi.

The driver was a friendly bald man with an opaquely slavic accent; he had been driving taxis for 22 years. "I am not rich," he said, "But I am there for my children. One must always be there for one's children."

At the Gatineau hospital, where I go to have my blood tested for its coagulation levels, I arrived at 6:30, still in darkness. I had no idea how to say "afterimage" in French, and so the nurses found my descriptions baffling.

After two hours in the waiting room (where an old man snored like a faulty jet engine), I spoke with a Dr. Bonneville. He took me through the standard procedure to find any symptoms of stroke, but I was able to follow his moving finger, see his moving hands with peripheral vision, touch my nose with both hands at the same time, and so on. No indication of stroke.

When I told him that I was on Coumadin for my blood clot, he gave me a grim look and said, "There's a problem with Coumadin: it makes you bleed." He spoke about one patient who, like me, had never experienced these visual phenomena before. The cause? Bleeding in the brain.

I must have turned pale. "Was he... all right?"

"Yes, he was fine; the bleeding was minor. And the chances of your having this condition are small. But all the same...."

When he left the room to call a neurologist, I stared at the probes and the tubes on the walls and did what I could to assure myself that my bleeding, too, was minor. By now it was 9:00 in the morning, I had not eaten since midnight, and I was also worried about hypoglycaemia.

The doctor came back, and told me that I was going to be transferred to another hospital for a CAT scan and a meeting with the neurologist at 2:00; the only drawback was that I would have to fast until the procedure was completed. I looked at the clock on the wall: four hours to wait without food, but what the hell. "I can handle that."

After blood tests and a long wait to see if the scan could be scheduled, a nurse put a shunt in my arm, and the staff paid a taxi driver to take me to the Hull Hospital, which happens to be less than a half-hour walk from my apartment building.

The driver was friendly, Muslim, and certain that he would no longer visit the United States. "Trump didn't win," he said, "Hillary lost. And I'm glad she lost." We went on to discuss her foreign policy record, and Trump's political pandering. By the time we arrived at the Hull hospital, we were both happy to be Canadians.

I was able to complete the scan half an hour before my appointment with the neurologist. The scan technician was helpful: she took me through each new step of the procedure before she acted. "Now I'm going to cross over to the other side, and inject the iodine." This made my head feel as if I were trapped under a sun lamp. The deep droning whir of the scanner made me think of a magnetic maelstrom.

Afterwards, when I took off the hospital robe to put my shirt back on, the gruff (but not unlikeably gruff), white-haired woman who ran the department said to me, "The changing booth is over there. This is not a changing room, this is my personal workspace."

I smiled and apologized. The old man waiting beside me for a scan said, "Don't worry about me, I'm not offended!"

An hour later, while I waited in the neurologist's office, I noticed a pair of threatening machines that looked like grinding or sharpening tools from a metal shop. I went up for a closer look; as far as I could tell, they were dental equipment.

The neurologist, Dr. Gagnon, came into the room at a rapid pace. A short, round-faced man with a comical moustache, he greeted me in French and began to talk about my symptoms.

"Pardonnez-moi," I said, "mais je manque un vocabulaire quotidien...."

He laughed, rolled his chair up to a computer monitor, and spoke in perfectly fine English with an accent I could not place -- German? Swiss?

"You've had your scan? Let's take a look at it." As he opened images on the monitor, I feared the worst.

"What we have here is -- oh, pardon me, that's my call." He answered the cell phone, stood up, left the room, and left me seated there. I began to fear the worse than worst.

When he came back after several minutes of worst, I said, in my horrible French, "I was here on the edge of panic, and then your phone rang...."

He laughed loudly and happily: "I love that!"

Then he displayed the scanned images in sequence, which made them look like a cartoon trip through a skull. I felt the strangeness that hits you when you peer at your own brain.

"Ah," he said. "I'm not worried for you. Everything here is the way it should be."

"Can this really show if something's wrong?"

"Oh, yes. It would show us tumours, blood clots --"

"And bleeding?"

"Oh, yes, bleeding too. But there's no sign of anything like that. And see this? Your vertebrae, aorta, they all seem fine. I'm not worried for you."

He explained that what I had seen had been a surge through the visual cortex, an aura without migraine. When people who have never experienced one before suddenly see an aura, doctors need to know the cause. And given my father's migraines, I had been wise to have this checked.

"If you go through this again, don't worry. Just let it pass. You should only be concerned if it leads to headaches or any other violent symptoms, or if it lasts for more than sixty minutes."

And so, nine-and-a-half hours after I had been dropped off at the first hospital, feeling weak, now, but not horrendously hypoglycaemic, I walked home on a bright and very cold afternoon. I thought about brains, about what can harm them, and I noticed all the cars around me, all the dangerous intersections, all the spots of ice on the sidewalk. I had been looking forward to biking season, and of course I always wore a helmet, but would a helmet really save me, if...?

Then I breathed in cold air, looked at the clear, cold sky, and reminded myself that Dr. Gagnon had shown me a healthy brain. This had to count for something. This had to be a cause not only for cerebration, but for celebration, too.

Published on March 14, 2017 13:36