Saaz Aggarwal's Blog

November 4, 2025

Q&A with Rita Kothari about her new book ITTEHAD, her translation of a 1941 book by Guli Sadarangani

An extraordinary book, translated by one of the very few English writers with admirably strong Sindhi skills as well – Rita Kothari. We had a very enjoyable zoom call together a few weeks ago, and the Q&A appeared in Hindustan Times yesterday. Read on!

Whatdrew you to this book and to translating it into English for a wider audience?

Rita:I’d known of Ittehad for at least 20 years. I’d come across referencesto it and always found it intriguing. I remember wondering, is VimmiSadarangani related to the writer Guli Sadarangani? And why doesn’t she appearanywhere? Not even in the two-volume 1993 anthology Women Writing in India:600 B.C. to the Present edited by Susie Tharu and K. Lalita. That includedPopati Hiranandani, Sundri Uttamchandani, and others – but not GuliSadarangani.

Andevery small entry I came across called the book controversial. To me, thatshould have made her better known, not less. Why was this pioneering woman, whowrote such a courageous book in 1941, missing? I felt this was a historicalimbalance. I wasn’t surprised when I learnt that even her son Kishore hadn’tread her work.

Findinga copy was a challenge, I finally got one from Sahib Bijani, Director of theIndian Institute of Sindhology at Gandhidham. And then finding a publisher – thiswas done through a collaboration between the Ashoka Centre for Translation andZubaan. It’s called Women Translating Women. Zubaan is bringing out manyother books in this series – and there will be other languages. I’m thrilledthat this Sindhi novel is part of a community of women’s voices,

Kannada,Malayalam, Tamil, Bengali, Sindhi and others, not standing alone as an outlier.

Translationcan be a small gesture, but it can have larger ramifications. At the veryleast, it was my way of paying homage to a pioneering and courageous womanwriter, the first woman novelist of our language. Not many people know ofSindhi literature, let alone a woman writer in pre-Partition Sindh. So it’s a minoritizationat several levels – woman, language, region, era.

Saaz: What were the problems that this1941 novel, offering love and equality between religions as a social andpolitical strategy in the years leading up to Partition, face when it waspublished and over the years?

Rita: Ittehad was ignored in its own time, thetheme was distasteful. It wasn’t widely read or discussed, and over the years,it didn’t feature in literary histories in English.

What I found compelling was how Guli Sadarangani managed tobe both conventional and subversive. There’s a clear valuing of romance andrelationships, yes – but also a questioning of institutions like marriage,property, and patriarchy. The protagonist, Asha, isn’t looking for salvationthrough marriage. She’s invested in her friendships, in her own selfhood, inthe idea that love can’t survive without independence.

There’s also a certain tenderness and idealism in howreligion is portrayed – not as dogma, but as a journey. The book feels radicalin its insistence on mutual respect and understanding, both between individualsand between communities.

Perhaps it was too gentle to be taken notice of, or tooidealistic, or perhaps it didn’t fit the more strident narratives that came todominate after Partition.

Saaz:What could it be about GuliSadarangani’s life and background that led to her producing a book with ‘woke’themes?

Rita: Guli Sadarangani was from an Amil family; theAmils are a Sindhi community with several generations of education. They tendto be more liberal, ahead of their time – as is this book, remarkably ahead ofits time.

Her brother, Krishna Kripalani was an English professor atShanti Niketan; in 1941 when Tagore died, he was appointed director. He is wellknown – but no one talks about the sister.

Guli also studied at Shantiniketan, which I believe wasformative for her. That’s where her character Asha also goes to study, in thenovel. Guli translated Gora, and I assume Tagore’s ideas influenced her.Another character, Aruna comes from a Brahmo Samaj background too – that’s theBengal connection which was common among liberal Sindhis before Partition.

Clearly, her family was progressive. Sending a young womanacross the country to study at Shantiniketan – those values must have shapedher deeply. She translated Gora, and wrote other novels too, which Ihaven’t worked with. But Ittehad felt like an important landmark.

Saaz: Russiacomes across a shadowy ideal in this book, could you please tell us what madeit special to Sindhi writers?

Rita: Most people in India see Sindhis as purelymercantile, without a cultural or intellectual life. But the truth is, prior toPartition, Sindh had a thriving intellectual scene. Many educationalinstitutions were run by Hindu Sindhis. After Partition, that cultural identityappears to have drained away.

Today’s stereotype of Sindhis in India as only money-mindedis post-Partition; in Pakistan, people acknowledge the role Hindu Sindhisplayed in creating cultural institutions.

My own father was not from an elite background, but names ofRussian thinkers, communism – meant something to him. In his lifetime, he swungfrom attending communist meetings in Kalyan to eventually admiring the BJP. Butthose multiple ideological influences coexisted, it wasn’t just Russia.

You see those same ideological streams in the novel – Gandhi,Tagore, Brahmo Samaj, communism. At the heart of it is always the question: howdoes one become a good, ethical citizen? The novel doesn’t always make clearwhere its moral compass lies, so it feels utopian at times. Yes, the 1940s werea critical time in Sindh – communal tensions, the Muslim League, HinduMahasabha, RSS, and so much more. To write a novel like this during that time –it meant something.

Saaz: Translatingacross cultures is never easy – which parts of the book did you find difficultto convey in English?

Rita: Most of the language in Ittehad wasurban and familiar to me, so not especially hard. But there were moments thatgave me pause. One passage stands out: when Hamid tells his mother he doesn’twant to marry and she asks if he’s in love. He says he is, and she asks, who isshe? “Khudaji bandi,” he replies, “A devotee of god!”

“Aren’t we all that?” she asks. “Tell me more, what abourher zaat-paat?”

And he says, “So now you want to know her zaat-paat!”

“Yes!” she replies, and when he reveals the girl is Hindu,her reaction is so interesting.

She says, “Really? Those people who consider us to beuntouchable, who won’t even accept food from us, you’re going to marry one ofthose?”

Words that are used for a sect, or a caste, have become ofhuge interest to me in the act of translation. It shows how the vocabulary weassume is about religion is often really about caste. Words like zaat, sampradaya,panth – we use them across different contexts, and they often blurcategories of religion, caste, and sect. This overlap has become a major areaof interest for me, especially in translation.

So there were interesting aspects – but nothing reallychallenging in the act of translation.

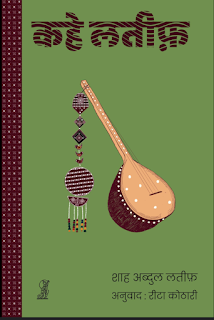

Saaz: Thatcouldn’t have been the case with your translation of Shah Abdul Latif intoHindi?

Rita: No it wasn’t – and I’ll admit that was a projectI care about even more. It’s called Kahé Latif and comes out next month.I selected about 450 of his poems. The translation felt like a lifetime wish – somethingI didn’t have the confidence to take on for a long time. It’s coming out fromVani Prakashan.

As you know, Sindhi is one of India’s important literarylanguages, with a 600–700 year-old tradition. This is almost unknown in India,even amongst Sindhis. If you ask an average person to name a Sindhi writer,they won’t know anyone. Popati Hiranandani may be translated, but how many haveheard of her? And there are so many other fine writers, writing on a range ofthemes.

So my Kahé Latif is another attempt at reclaiming ourliterary tradition. It’s a Hindi translation, done directly from Sindhi – notfrom English, and not as a prose rendering, but in poetic verse. There are manyEnglish translations of Shah Latif, but we don’t have versions that retain thealliteration and rhythm of the original. Hindi allowed me to do that. I hopepeople will read it aloud in Hindi, quote it the way Latif is meant to bequoted.

Saaz: You once told me that you find the Sindhi community verypatriarchal. My experience has been quite different. What could be the reasonsfor this?

Rita: That’s interesting, and I think it points to how diverse andheterogeneous the Sindhi community is. My sense of the community comes fromgrowing up in Kachchh, where I saw strong male dominance – in trusts,institutions, and family decisions. Patriarchy was embedded in everyday life.But in your experience, perhaps among Sindhis in urban centres or in thediaspora, there’s more fluidity and exposure to other ways of being.

It’s a difference worth thinking about. Maybe there aremultiple Sindhi worlds – and they’reshaped by region, class, mobility, and memory in very different ways.

First appeared in HT Premium on 3 November 2025 on https://www.hindustantimes.com/books/...

October 25, 2025

Sindh in books: breaking silence, rebuilding memory

A round-up of recent books about Sindh

Saaz Aggarwal

The story of Sindh has fascinating layers andnuances, but has largely been neglected or trivialised. The forceful scatteringafter Partition created confusion. The internet is clogged with wrong dates,misinterpretations, and one-sided accounts – enormous swathes of informationthat remain two-dimensional, insular, detached from historical reality, oftenshrouded in unappealing clouds of unresolved trauma. Those who work to create acoherent, reliable body of knowledge about Sindh are swimming against the tide.Those who grasp the breadth of Sindhi poetry, philosophy, music, architecture,cuisine – despair at how public perception has narrowed to a single icon, Jhulelal,and an annual festival, Cheti Chand. Yet, as newer generations respond to thecall of their ancestry, a quiet resurgence has begun.

One of the most remarkable new titles is Lionof the Sky by Ritu Hemnani (HarperCollins, 2024). Written in free verse, itplunges the reader into pre-Partition Hyderabad (Sindh) and, through the eyesand heart of a young boy, brings the lost land and a vanished world alive. Eachword creates a vivid image, each pause a moment of recognition.

Ifyou break a kite string it’s bad

If the stitches break, it’s bad

If you can’t calculate, it’s bad

If you block a railroad, it’s bad

I may not know very much

about the line thisBritish man is drawing

but Ido know one thing.

It’sbad.

In less than half a page, we are immersed in thedomestic and political world of that time: a festive activity, the genderedexpectations of a trader family, passionate participation in the freedommovement, and that ominous line which would end an era.

In less than half a page, we are immersed in thedomestic and political world of that time: a festive activity, the genderedexpectations of a trader family, passionate participation in the freedommovement, and that ominous line which would end an era.Anothercompelling title is SIMSIM by Geet Chaturvedi, translated by Anita Gopalan (Penguin, 2023). Theprotagonist – that peculiar old man, trembling and dribbling, half in the pastand half in myth – embodies the haunting loneliness of exile, among the finestcontemporary explorations of Sindhi displacement.

Long before these newer voices, Meira Chand (born1942) brought the Sindhi presence into global literary consciousness. Writingfrom Singapore and Japan, her novels – some adapted for the stage in the 1990s –include well-drawn cameos of Sindhi characters.

For readers seeking an intimate understanding ofPartition in Sindh, The Night Diary and Amil and the After byVeera Hiranandani offer rare insights. Through the eyes of children, theyrecreate what it meant to lose one’s home and to rebuild life amid confusionand resentment. These stories balance tenderness with historical precision:they bring out the complex relationships between communities, the moraldisarray of that moment, and the struggle to make sense of a world suddenlydivided. These are books for younger readers, and deal with themes of death andviolence unflinchingly and with such care that they feel redemptive rather thantraumatic. Friendship, family, and courage become the motifs through whichhistory’s hardest truths are encountered.

For readers seeking an intimate understanding ofPartition in Sindh, The Night Diary and Amil and the After byVeera Hiranandani offer rare insights. Through the eyes of children, theyrecreate what it meant to lose one’s home and to rebuild life amid confusionand resentment. These stories balance tenderness with historical precision:they bring out the complex relationships between communities, the moraldisarray of that moment, and the struggle to make sense of a world suddenlydivided. These are books for younger readers, and deal with themes of death andviolence unflinchingly and with such care that they feel redemptive rather thantraumatic. Friendship, family, and courage become the motifs through whichhistory’s hardest truths are encountered.

Equally evocative is Mukund and Riaz,written and illustrated by Nina Sabnani, as it transforms her father’slate-life memory of friendship and loss during Partition into a thirty-page picturebook and a short film. Using Sindhi appliqué motifs and luminous colour, Sabnanicreates a tender meditation on a memory her father shared with her short yearsbefore he died, something he had never spoken of before: his best friend, andwhat happened to his cap. Using motifs drawn from Sindhi appliqué, every frameglows with colour, underlaid with sadness.

Equally evocative is Mukund and Riaz,written and illustrated by Nina Sabnani, as it transforms her father’slate-life memory of friendship and loss during Partition into a thirty-page picturebook and a short film. Using Sindhi appliqué motifs and luminous colour, Sabnanicreates a tender meditation on a memory her father shared with her short yearsbefore he died, something he had never spoken of before: his best friend, andwhat happened to his cap. Using motifs drawn from Sindhi appliqué, every frameglows with colour, underlaid with sadness.Othernovels which explore Sindh’s landscape of loss and renewal include TRYST WITH KOKI bySubhadra Anand (Authors Upfront 2023), THE TATTOO ON MY BREAST by Ravi Rai (Bloomsbury,2019), THE SWING byIsha Merchant (Notion Press 2023) written when the author was 12.

Other novels which explore Sindh’s landscape ofloss and renewal include Tryst with Koki by Subhadra Anand (AuthorsUpfront 2023) and The Tattoo on my Breast by Ravi Rai (Bloomsbury, 2019.The Swing by Isha Merchant (Notion Press 2023) is notable because it waswritten when the author was just 12 years old. You Have Given Me A Countryby Neela Vaswani (Sarabande Books 2010) retails in India at ₹2514 but MurliMelwani (introduced below) called it “an excellent read,” particularly thechapter about her visit to India to meet her father’s family. The most authentic glimpses into Sindh, though,come through translation. Ittehad by Guli Sadarangani (1928–2017),translated by Rita Kothari (Zubaan, 2025), resurrects a lost literary voice aswell as the intellectual world that thrived in Sindh before its dismemberment.Written in 1941, this extraordinary novel brims with “progressive” ideas – theneed for women’s financial independence, the right to choose one’s partner,religion as a path of spiritual growth rather than division, and the treatmentof labour as partner rather than subordinate.

The most authentic glimpses into Sindh, though,come through translation. Ittehad by Guli Sadarangani (1928–2017),translated by Rita Kothari (Zubaan, 2025), resurrects a lost literary voice aswell as the intellectual world that thrived in Sindh before its dismemberment.Written in 1941, this extraordinary novel brims with “progressive” ideas – theneed for women’s financial independence, the right to choose one’s partner,religion as a path of spiritual growth rather than division, and the treatmentof labour as partner rather than subordinate.Another compelling contribution is The Pagesof My Life, memoir of Popati Hiranandani (1924–2005), translated by JyotiPanjwani (OUP 2010). It recounts her girlhood, education, Partition, andprofessional life as a writer and academic with candour and verve. One of the mostmemorable anecdotes describes a prospective suitor discussing dowry, to whichshe calmly replies that since she earns more than he does, perhaps his familyshould be paying dowry to hers.

GuliSadarangani and Popati Hiranandani belonged to Sindh’s Amil community, which valuededucation, reform, and social consciousness, more about which in THE AMILS OF SINDH [black-and-whitefountain (bwf) 2019].

Guli Sadarangani and Popati Hiranandani belongedto Sindh’s Amil community, which valued education, reform, and socialconsciousness. Their world is explored in my book The Amils of Sindh [black-and-whitefountain (bwf) 2019], which traces the community’s history from itsadministrative roles in Sindh to its post-Partition adaptation in India.

Guli Sadarangani and Popati Hiranandani belongedto Sindh’s Amil community, which valued education, reform, and socialconsciousness. Their world is explored in my book The Amils of Sindh [black-and-whitefountain (bwf) 2019], which traces the community’s history from itsadministrative roles in Sindh to its post-Partition adaptation in India.Talesfrom Yerwada Jail (bwf,2013), by the prolific Rita Shahani (1935-2013), deeply beloved even today inthe lost homeland, is also significant. Through memories from within her family,the book offers a glimpse of the passionate involvement of Sindhis in thefreedom movement – only to face permanent exile when Independence finally came.I cannot speak or read Sindhi, and translated this book in collaboration with theauthor. She read aloud the Sindhi text while I made notes, and we refined successivedrafts together until both were satisfied.

The most exceptional translation yet is RitaKothari’s Unbordered Memories, a curated anthology of post-Partitionshort stories. It presents the Sindhi experience from various vantage points –departure, wrenching farewells, humiliation in refugee camps, and thedesolation of those left behind in Sindh. The stories are filled with pain andnostalgia, emotions almost never expressed in Sindhi families. Freedom andFissures (Sahitya Akademi, 1998), a collection of Partition poetry issimilar, translated by pioneers Anju Makhija and Menka Shivdasani, working withSindhi poet Arjan “Shad” Mirchandani. Like me, neither translator can read orspeak Sindhi. These collaborations reveal the paradox of a language thatsurvives largely through mediation; a poignant commentary on Sindhi’s fracturedafterlife.

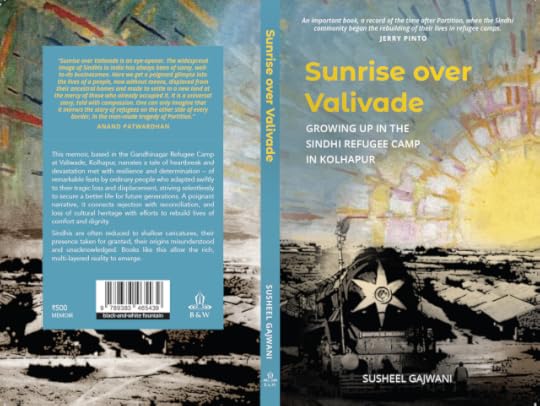

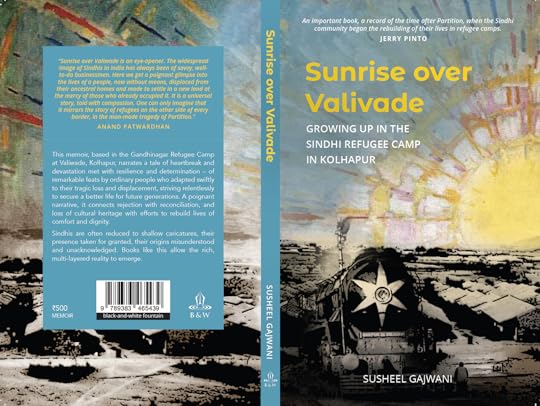

Other books weave family histories, oraltraditions, and lost geographies into personal testimony. My Sindh byShakuntala Bharvani (bwf, 2022) blends essays, family stories, and musings on colonialtexts into a mosaic of nostalgia and scholarship. Refugees In Their Own Countryby Sunayna Pal (bwf, 2022) distils the Sindhi Partition experience intoillustrated verse – graceful, dignified, grief-struck. Sunrise Over Valivadeby Susheel Gajwani (bwf, 2025) sets the Sindhi resettlement story within aKolhapur camp originally built for Polish refugees, linking it to a globalnarrative of displacement.

In Sindhi Tapestry: An Anthology ofReflections on the Sindhi Identity (bwf 2020) I received contributions fromsixty contributors of different ages, backgrounds, and professions, exploring awide range of themes around heritage, displacement, and belonging. Severalrecalled being taunted: “If you see a Sindhi and a snake, whom should you killfirst?”

Many books on this list are self-published, byno means vanity or lack of competence, rather the valiant efforts of survivorsof a catastrophe to keep their culture alive. The most notable exception is TheMaking of Exile by Nandita Bhavnani (Tranquebar Press, 2018). A comprehensiveand nuanced account of the Sindhi experience of Partition, it meticulouslyexamines every dimension – political, social, and psychological. Her narrativeis precise and compassionate, and through its measured prose, the reader feelsthe full emotional weight of dislocation. Among its most affecting sections arethose describing the despair of Sindhi writers who, after Partition, lost notonly their homes but also their readership, their sense of audience, and, inmany cases, their will to write. Many died heartbroken.

Many books on this list are self-published, byno means vanity or lack of competence, rather the valiant efforts of survivorsof a catastrophe to keep their culture alive. The most notable exception is TheMaking of Exile by Nandita Bhavnani (Tranquebar Press, 2018). A comprehensiveand nuanced account of the Sindhi experience of Partition, it meticulouslyexamines every dimension – political, social, and psychological. Her narrativeis precise and compassionate, and through its measured prose, the reader feelsthe full emotional weight of dislocation. Among its most affecting sections arethose describing the despair of Sindhi writers who, after Partition, lost notonly their homes but also their readership, their sense of audience, and, inmany cases, their will to write. Many died heartbroken.Among newer finds is The Son-in-Law fromSindh by Premilla Rajan. The title suggests a humorous cultural study of themuch-pampered Sindhi son-in-law – and the cover, the mugshot surrounded by stampsfrom around the world, heightens that anticipation. What emerges, however, is apatchwork comprising affectionate anecdotes, lists of information some wildlyinaccurate, and a few priceless glimpses into the Sindhworki world.

Who were the Sindhworkis? Soon after the Britishannexation of Sindh in 1843, groups of young men began to board steamshipsladen with “Sindh work” – intricately crafted goods, textiles, and curios – andsailed out to trade across the Empire. Long before Partition, they hadestablished mercantile networks, a remarkable history documented by the Frenchscholar Claude Markovits in The Traders of Sindh: From Bukhara to Panama(2000).

Among the earliest fictional treatments of thisworld is Beyond Diamond Rings (Pustak Mahal, 2009) by Kusum Choppra.Daring and emotionally charged, it portrays the anguish of Sindhworki womenwhose husbands lived in distant lands and who, when Partition erupted, had toflee alone with their children and elderly. The most luminous portrayal of theSindhworki world, however, is Beyond the Rainbow (bwf, 2021) by MurliMelwani, which won the International Impact Book Award in 2025. Its elevenshort stories, set in Chile, Hong Kong, Canada, Thailand and other countries,trace the arc of Sindhi enterprise and endurance. Murli, who grew up inShillong, studied English Literature and became a professor – and later adiaspora businessman – writes with precision and empathy, exploring the deeperthemes of a homeland that no longer exists, the fragility of language, and themoral codes of a people who survived upheaval through work and faith.

Among the earliest fictional treatments of thisworld is Beyond Diamond Rings (Pustak Mahal, 2009) by Kusum Choppra.Daring and emotionally charged, it portrays the anguish of Sindhworki womenwhose husbands lived in distant lands and who, when Partition erupted, had toflee alone with their children and elderly. The most luminous portrayal of theSindhworki world, however, is Beyond the Rainbow (bwf, 2021) by MurliMelwani, which won the International Impact Book Award in 2025. Its elevenshort stories, set in Chile, Hong Kong, Canada, Thailand and other countries,trace the arc of Sindhi enterprise and endurance. Murli, who grew up inShillong, studied English Literature and became a professor – and later adiaspora businessman – writes with precision and empathy, exploring the deeperthemes of a homeland that no longer exists, the fragility of language, and themoral codes of a people who survived upheaval through work and faith.

Sindhworkand Sindhworkis(1919) was written by Tekchand Karamchand Mirchandani after a long career in Sindhwork.It describes the drab lives of the young men who toiled abroad, exploited by thecapitalists comfortably ensconced in Hyderabad. Itdescribes the drab lives of young men who toiled abroad, exploited by capitalistscomfortably ensconced in Hyderabad. Sarla Kripalani (1920-2022) translated it in2001, preserving a rare and invaluable record. The translation is included in Sindh Bani (Rupa, 2025),with two other works also long in the public domain: Short Stories of Sindh – shared digitallyon Sarla’s ninetieth birthday in 2020 – and Aaya Pir, Bhagga Mir and Other Sindhi Proverbs,published in 2008. The beautiful cover, displaying “Kutch” rather than “Kachchh”,inadvertently shows how regional identities can be altered in print. Sarla was apassionate storyteller and it’s unfortunate that public acclaim of her work waswithheld from her.

Sindhworkand Sindhworkis(1919) was written by Tekchand Karamchand Mirchandani after a long career in Sindhwork.It describes the drab lives of the young men who toiled abroad, exploited by thecapitalists comfortably ensconced in Hyderabad. Itdescribes the drab lives of young men who toiled abroad, exploited by capitalistscomfortably ensconced in Hyderabad. Sarla Kripalani (1920-2022) translated it in2001, preserving a rare and invaluable record. The translation is included in Sindh Bani (Rupa, 2025),with two other works also long in the public domain: Short Stories of Sindh – shared digitallyon Sarla’s ninetieth birthday in 2020 – and Aaya Pir, Bhagga Mir and Other Sindhi Proverbs,published in 2008. The beautiful cover, displaying “Kutch” rather than “Kachchh”,inadvertently shows how regional identities can be altered in print. Sarla was apassionate storyteller and it’s unfortunate that public acclaim of her work waswithheld from her.Tracesof colonisation, the blurring of idiom, the subtle drifts of meaning that erodea culture from its own vocabulary appear in many of the books listed here: sethiafor setha, maike for peko, Ramadan for Ramzan, dupatta for ravo; a lost diarynever returned because its pages were needed for cleaning backsides, a claim atodds with lived practice in South Asia.

WhenSindhis say they “came to India” or “our roots are in Pakistan,” they arereiterating the absurdity that Pakistan existed before their expulsion. Sindhis often described as having escaped the full fury of Partition’s violence. Butthe violence of Sindh’s Partition was insidious – social, linguistic,psychological – and continues to echo through generations.

Appearedin Hindustan Times on 23 October 2025 https://www.hindustantimes.com/books/from-sindh-in-books-breaking-silence-rebuilding-memory-101761212246870.html

August 27, 2025

Interview with Ramya Sarma about her book Asha Bhosle: A Life in Music

Ramya Sarma

Ramya SarmaCourtesy Neeta Kolhatkar

Saaz: You’ve been associated with ‘Bollywood’ for a long timewithout an actual association with it – what’s that been like?

Ramya: I've been part of creating websites on Bollywood and itsassociations. It's been a lot of fun. Incomprehensible at times, annoying attimes, and hilarious very often. It's a world I would normally never step intowearing any mask I might think of, but it's a very colourful, whimsical, crazyyet terribly intense and demanding world which can be daunting if you don't setgood sense, logic and schedules aside and leap in, without thinking too hard ortoo straight. Running websites is notabout knowing that world, but about knowing the audience that wants to knowthat world. And ‘people’ is a far more interesting realm, one that makes mewant to know more. I've never been glamour or star struck, so the desire tomeet stars or even watch films has never been strong. I have always beencurious about the people who make up that starry world - like thedetermination, hard work and charisma that has carried Asha Bhosle, ShahrukhKhan and others of their quality to the places they now hold. As far asinterviewing filmi types, doing film reviews, watching shoots, et al...no, notfor anyone who is a little OCD about time and place!

Saaz: And now you’ve written a book about someone you never metand yet you managed to create a very vivid, lifelike impression of her within afew pages, which keeps growing through right till the end. How?

Ramya: My editor-publisher Bidisha Ganguly and I have worked reallyhard to make this book something special. I aimed for the unexpected, which iswhat makes me want to read a book. It's really very simple: when you knownothing or close to nothing about something, your perspective is unbiased. Youdive in and explore, learn, question, without preconceived notions orpreconditions. It's like eating those filled chocolates...what they're filledwith, you never know until you bite in. And AB is a PERSONALITY, someone whohas done fabulous things with the life she has lived. What I admire is herresilience and that chutzpah to keep going, and going higher. If I conveyed that, great! But a lot of people don'tsee that she's not just a star, she's a human being, with very human reactionsand behavioural quirks. In glorifying her, that aspect rarely comes through.And while she's earned the right to that glory, there's so much more to her.Talking to people who are not obviously connected to filmbiz brought out thatpart of her, I think...I hope.

Saaz: Why Asha Bhosle of all people?

Ramya: It kinda landed in my lap, honestly. And I agreed to do itbecause it was a challenge and I was bored of the same old, same old. And onthe way I found that she's the kind of woman I'd like knowing, someone who hastalent, intelligence, sass, strength and, yes, frailties that have only givenher power. I think that is an embodiment of Shakti, power, a realm that rules.I like the concept of feminine power, ofShakti!

Saaz: What was your most memorable event in the process ofwriting this book?

Ramya: Well there were some very fun and some very memorablestories. Like learning about AB eating crisps with Shujaat Khan in London. Likeher sitting and snacking in the car in Delhi with Parveen Khan. Like herdelight at being recognised at the airport for a non-filmi work. Like her firstmeeting with Boy George, and admiring how he did his eyebrows. But my favouritemoment, apart from the friends I made – by the way, almost every interview Idid was food linked somehow! – was that email I got from Boy George. I openedit as soon as I woke up at 5.30 am one dawn and squeaked! Woke up lots ofpeople – who really didn't care – and chirped excitedly at them...Why was thatso special for me? It's a little silly, but when I was a teenager and trying tofigure out how to be a girlie girl without overdoing it, I got an album of BoyGeorge and Culture Club; BG was on the cover, with glorious eyes made upbeautifully. And that is still my ideal when I do my face!

Saaz: And the most challenging?

Ramya: There were two aspects that were not just challenging, butplain hard on me, playing tricks with my self-worth and my mind. One was thedelay that the project went through (if that's the right way of putting it?) atevery stage, almost every page, with the first publisher. That was frustrating,hurtful, annoying, all those negative emotions that have been, frankly,scarring. The second was to pin down the few film types that I did get to speakto me. One of them made up for it in style, for which I am forever grateful anda fan – Sonu Nigam, who changed his mind about meeting me often, even when Iwas right outside his house. But he made up for it by doing the whole interviewand singing fabulously on WhatsApp voice messaging! The others...that wouldmake one of those really funny personal memories books that so many people arewriting. I've mentioned some of them in the book’s intro.

Saaz: Looking back to the time you started working on this,what has changed in you, what did you learn?

Ramya: That life may throw you stinkers and more will come out ofleft field, but you will eventually do what you set out to do if you reallywant to do it. I guess it's like Asha Bhosle herself, hard work, grit anddetermination gets you to the end line. What changed in me is very little, I'mstill me, albeit with more silver and less hair and a few extra lines thatdon't come from giggling, usually inappropriately!

Saaz: How about sharing a few stories that didn’t make it tothe book?

Ramya: There are many … like the time my sandals broke rightoutside Lesle Lewis' studio and I trudged through the building barefoot. Seeingmy woeful state, he made me put my feet up on his squishy sofa, talked to mefor ages and then sang songs from his new album, then offered me a pair ofoversized rubber chappals to get me back to my car! Then there was Sumit Dutt,who was in a meeting but came out for "ten minutes" and then sat withme for over an hour telling me stories about Ashaji singing under a large yellowumbrella in a waterfall! People surprised me with their generosity, kindnessand plain niceness.

Saaz: Asha Bhosle is writing her autobiography. What do youexpect that to have which your book doesn’t have?

Ramya: Obviously, a great deal, since it's her own life that shewill write about. But the book has been announced many times and shelved manytimes. In fact, when I was with Poonam Dhillon, she called Ashaji to ask if shemay speak with me. The lady agreed, telling her she could say what she wanted,since her own book was almost done and would be out soon. A couple of monthslater, she announced that she had decided that her life was her life and shesaw no reason for other people to know about it, so her book would not bepublished. If it ever is, I'd line up to buy it!

Saaz: Finally, what do you expect from the release of thisbook?

Ramya: Obviously good sales, since that would make my publisherhappy! And, of course, for readers to learn something new about Asha Bhosle,something that they had never seen or heard of before. Because that's what wewere looking to do!

This interview was published in Hindustan Times on 27 Aug 2025.

https://www.hindustantimes.com/books/...

Ramya and Saaz at the launch on 12 June 2025

Ramya and Saaz at the launch on 12 June 2025June 10, 2025

Daneesh Majid: “History has mostly been written by those in power”

What struck me most about Daneesh Majeed’s book about whattranspired during princely Hyderabad’s integration into India in 1948, is itsparallels with the Sindh story. People did not consider their experiences worthdocumenting, eclipsed as it was by the much larger-scale violence elsewhere.Despite the dramatic lifestyle changes, colonization by dominant cultures,being sidelined in the administration and left to fend for themselves, theyfaced their plight with bravery and stoic acceptance. The book also exposescaricatures showcased through pop culture, media, and India’s many filmindustries.

Saaz: Why now, Daneesh? Whatgave you the courage to address this important piece of our history and theunjustifiably long gap in public discourse? And how did you approach writingabout that politically sensitive moment?

Daneesh: It wasn’t necessarily courage. An epiphany back in early 2020propelled me into action. A little before Covid, a video interview I conductedwith Arshad Pirzada crystallized something I had been thinking about whencarrying out some Hyderabad-centric features for The Hindu Business Line’sweekly magazine two years earlier. Pirzada is a former Gulf NRI whose familycame from a priestly lineage and had ties to the bureaucratic Asaf Jahiestablishment. Post-1948, they had to adjust to life as numerical minorities ina democratic landscape unlike the old feudal setup in which the ruling Muslimminority held sway. The hen Siasat.com chief editor, Ayoob AliKhan, chided both of us for not emphasizing this fall and rise aspect ofPirzada’s journey, one which included him becoming an economic migrant to SaudiArabia and paving the way for his family’s economic revival.

SThere are plenty of such stories in Hyderabad that have remainedundocumented (not only because many elders are no longer with us) and dilutedthrough generations. A lot of these accounts have not been brought to the forethrough crisp, timely and accessible narratives in the vein of works by authorslike Urvashi Butalia, Anam Zakaria, Aanchal Malhotra and yourself.

As for my approach, I could not solely rely on oral accounts.Besides my own enormous bookshelf, I scoured various bookstores, accessedpersonal libraries and found some academic articles to recreate the eras andbuild worlds that that the 11 different families lived in. My editor VikramShah’s nudges in the right direction were key to this.

Saaz: Hyderabad is a city ofsyncretism, but also of stark divides – linguistic, religious, and class-based.How did you navigate these complexities while telling its story?

Daneesh: Some of these divides existed pre-1948.

For instance, many people believe that the Mulki agitation whichbegan surfacing in the early 1950s was the earliest harbinger of theTelangana-Andhra divide. One story an acquaintance told me was about his father,a participant in the anti-Nizam and eventually anti-Indian government struggle.When his father was hiding out among Andhra Telugu cadres and interacting withordinary citizens during the late 40s in Bapatla, Madras Presidency, some ofthem either wondered how he was able to articulately communicate in Teluguwhile many poked fun at his Telangana dialect outright. That too, despite thefact that the Andhra Jana Sangham which helped foment revolt in Telanganabrought the Telugu populations from Madras Presidency and Telangana together onthe basis of language. He also spoke of how Andhraites monopolizeddecision-making out of a sense of organizational superiority.

So rather than only looking at these divisions throughpost-colonial, contemporary lenses, finding and citing primary/secondarysources that mention previous iterations of these divisions helped innavigating those present-day discords.

Saaz: Could you tell us about your mostimportant sources, and share any stories that surprised you or changed yourthinking?

Daneesh: Two important ones which altered specific notions come to mind—bothmy own and commonly held ones.

Dr. Rafiuddin Farouqui’s compilation of the Aurangabad (then apart of the Nizam state)-born Maulana Maududi’s letters, in which he beseechesQasim Razvi to negotiate the best terms of accession with the Indiangovernment. It showed a more farsighted, accommodating side to someone thatmany, including my own great-grandfather who served as a Director in theReligious Affairs Department of Princely Hyderabad, saw as a hardliner.

Chukka Ramaiah, the now 98-year-old activist who participated inthe early days of the Telangana Revolt not only abhorred the ruled Hindu vs.ruler Muslim angle of looking at the anti-Nizam struggle, but a cruder versionof the Andhra versus Telangana binary too. He was all praise for a class ofAndhraites who arrived in Hyderabad state during the early 50s, not asmonopolisers of the commercial and ruling dispensations. This group ofegalitarian-minded teachers from Andhra uplifted Telangana Telugus who previouslydidn’t have access to education, especially in their mother tongue.

Saaz: Our respective works (mine on theSindhis) trace the afterlives of two distinct but parallel communities deeplyaffected by the reshaping of India after Partition. What does this say abouthow we remember the ‘unwritten histories’ of India – the ones lived not bygovernments, but by people?

Daneesh: History has mostly been written by those in power. Today,various political figures have been rewriting history especially through theirelection rhetoric. Since 2018, state, municipal and national polls saw certainopposition factions referring to then Chief Minister KCR as the “New Nizam.” Theyrecasted national figures as reincarnations of the Iron Man who humbled OsmanAli Khan. The “Nizam culture” was blamed entirely for the city’s so-calledinability to become a global IT hub.

All this amounts to a constant rewriting of the past by thepowers that be as they evoke the powers that were! But it is the ordinary citizenryof today, the majority of which doesn’t have the time nor resources to (re)evaluatebygone eras, who gets polarized as a result. Cinema, social media reels andWhatsApp forwards, backed by a robust ecosystem don’t help either.

Yes, the Nizam possessed his shortcomings, and princelyHyderabad had a dark side to it. But this us-versus-them prism, with the Nizamand the Razakars being equated as the sole aggressors, has gained too muchcurrency.

I was told first and second-hand stories from Kayasthas andTelangana Hindus about Osman Ali Khan’s personal generosity and his patronageof temples. A lot of Telugu and Urdu literature chronicles how religiousMuslims took to the onset of leftism against a feudal set up spearheaded bytheir “own.”

Micro-histories that ask the “big” questions about historical occurrences, inthe “small” places are the need of the hour.

Saaz: Food, tehzeeb, language, architecture– Hyderabad’s cultural distinctiveness is legendary. Which elements do youthink are still thriving, and which are slipping away?

Daneesh: Shervanis as well as Rumi topis are still worn at weddings andvarious functions. The food for the most part is still around. The feudal mentalitythat makes things more hierarchical while also inducing inertia amongHyderabadis won’t disappear anytime soon. That being said, to varying extents,these elements certainly haven’t been immune to the onset of McDonaldization.

The Dakhani dialect, which isn’t in danger of being fullycannibalized by shuddh Hindi or khaalis Urdu yet,can still be heard widely. But the nastaleeq script in which one can readDakhani and standard Urdu literary gems, is rapidly fading away.

Signboards on streets as well as government offices and Urdu“jashns/anjumans” that often take place are in no way indicative of anysubstantive revival.

Unless the prose is translated, which to some is code for“diluted,” so much literature risks becoming obscure or an exotic relic of thepast. In the past three years, some of my favourite Old City bookstores haveclosed or aren’t selling non-religious content.

Saaz: Did you find yourself having to leavecertain things out – whether due to space, sensitivity, or complexity? Arethere stories you wish you’d been able to tell more fully?

Daneesh: Yes. Throughout my research and fieldwork, I learned of someinteresting reasons regarding why some Hyderabadis did or didn’t undertakelife-altering migrations to the West, the Gulf, other Indian cities, certainparts of Telangana/AP, or even Pakistan.

There are some intriguing anecdotes about why some Muslimsdecided to either stay in India or make the move to Pakistan. After 1948, eventhe apolitical, professional class of Hyderabad’s Muslims, regardless ofwhether they had ties to the nobility, considered settling in Pakistan. Despitethe 1965 War, which put spokes in the wheel of Indo-Pak travel, many left forPakistan in the 1970s out of personal grievances.

Including such sagas would have provided a more personal,interior context as to why people decided to leave their families and nativesoil. However, if an interviewee requests for the omission of any detail oranecdote, out of respect and sensitivity, I have to oblige.

Saaz: Who did you imagine asyour ideal reader while writing this book – and what do you hope they will takeaway from it?

Daneesh: My ideal reader was always someone who wants to lookat how people remember tragic episodes alongside common, sometimes militantlymainstreamed interpretations. Irrespective of whether the reader approaches myfirst book as such, at the very least, I hope that they get to experience theflavour of Hyderabad through its 11 diverse families. After all, a city’scultural distinctiveness isn’t only defined by its monuments, cuisine andlanguages, but also by those who call(ed) it home.

This interview was published in Hindustan Times on 10 Jun 2025.

https://www.hindustantimes.com/books/...

April 29, 2025

Interview with Kishore Mahbubani for Hindustan Times

Saaz: Your childhood wasmarked by hardship, malnutrition, and poverty. You’ve spoken of the strengthand skills this gave you – how did you develop them? As a diplomat, whatsolutions would you suggest for helping children in similar situations?

Kishore: Since Singaporeis now one of the most affluent countries in the world, many Indians areunaware that at independence, Singapore was one of the poorest countries in theworld. In 1965, its per capita income was the same as Ghana in Africa: $500. Iexperienced this poverty personally. I was put on a special feeding programmewhen I went to school at the age of 6 as I was technically undernourished. Ourhome had no flush toilet. Debt collectors would come to our house regularly. Myfather went to jail. Yet, I was able to overcome many of these adversitiesbecause I had an unusually strong mother who never broke down under all thesepressures. The resilience I developed in my life was a gift from her to me.

One reason why I wrote mymemoirs is that I wanted to give hope to young people who may be suffering thesame kind of difficult childhood I had experienced. It’s good for young peopleto understand that people like them have overcome difficult circumstances.

Saaz: Your book praisesLee Kuan Yew (who often gave you a tough time) extensively. What measures fromhis leadership could India adopt for better development?

Kishore: Singapore’sexceptional success as a country was due in large part to three of itsexceptional founding fathers: Lee Kuan Yew, Dr Goh Keng Swee, and S.Rajaratnam. One of the great privileges of my life was getting to know allthree of them well. From them, I learnt a lot about how countries could succeedin development. I distilled many of the lessons I learned from them into theacronym “MPH”. In this case, it doesn't stand for “miles per hour” but for“Meritocracy, Pragmatism and Honesty”, which is the secret formula forSingapore's success.

Meritocracy is about choosingthe best people to run your organisation, society or country. Lee Kuan Yew wasinsistent that only the best should be selected to serve in the government.

Pragmatism is about beingwilling to learn best practices from any source anywhere in the world. Dr GohKeng Swee once said to me that no matter what problems Singapore encounters,somebody somewhere must already have encountered it. Hence, Singapore shouldproactively learn lessons from other countries. Dr Goh also pointed out thatsince Japan was the first Asian country to succeed, Singapore should studyJapan carefully if it wanted to succeed as well. India could also learn lessonsfrom Japan's development.

Honesty is about eliminatingcorruption. This is crucial as trust and stability are essential for an economyto thrive. Unfortunately, this is also the hardest principle to implement.

I believe that any society inthe world, including India, would succeed and do well if it implemented thesecret Singapore MPH formula.

Saaz: Could you tell ussomething about the different diplomatic communities you encountered?

Kishore: Walking into theUN headquarters and experiencing a real global village of representatives from159 countries was always a thrill for me. Though we all came from strikinglydifferent cultures and traditions, we were able to forge many close friendshipswith each other based on our common humanity.

When I joined the UN in 1984,some of my Arabian colleagues declared that I belonged to their tribe becausemy surname, Mahbubani, comes from an Arabic/Persian word, “mahbub,” which means“beloved.” Most Sindhis are Muslims. Due to my Sindhi roots, I felt some degreeof cultural affinity with both the Arab countries and Iran. And since I sporteda beard then, I was occasionally mistaken for an Iranian diplomat when I wasseen without a tie.

The ambassadors from the fivefounding member states of ASEAN—Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines,Singapore, and Thailand—came together like comrades in arms to defend ourcommon interests. I also became very close to the African ambassadors, whom Ifound to be incredibly reliable and trustworthy. If you became friends withthem, they would remain steadfast and stick with you through thick and thin.

I also worked with USambassadors who were polar opposites: Ambassador Vernon Walters was incrediblywarm and generous and won many friends for the US, while Ambassador JeanKirkpatrick was harsh and condescending towards the UN community in a bid towin favour with right-wing politicians at home. While American diplomats couldbe very direct and candid, they could also mingle easily with allnationalities. By contrast, European diplomats seemed to have an irrepressibledesire to preach to other countries about human rights issues. I was thereforeshocked to witness the incredible evasive skills of the Western diplomats whenI chaired the oversight committee of the UN Programme of Action for AfricanEconomic Recovery and Development (UNPAAERD). They expertly avoided making anyconcrete and binding commitments to help the African countries despite thepassionate speeches they had given in the UNGA about wanting to do so.

Saaz: Please tell us aboutyour visit to Sindh.

Kishore: When ShaukatAziz, whom I had met in New York and Singapore when he was the Vice Presidentof Citibank, became Prime Minister of Pakistan (2004 to 2007), he invited me tovisit Pakistan. I went to Karachi, Hyderabad, Islamabad and Lahore. It was afascinating visit. Then Pakistani High Commissioner to Singapore AmbassadorSajjad Ashraf also arranged a special visit to Hyderabad, where my mother hadgrown up. While my mother was sadly no longer with us, her brother, MrJhamatmal Kripalani, was able to draw me a map to their childhood home.Fortunately, we were able to find it.

Since I had grown up listeningto stories of how Muslims and Hindus had killed each other during Partition, Iexpected to encounter hostility in Hyderabad when I went to search for mymother's home. Instead, every Muslim person I met in Pakistan received me verywarmly and was delighted to see me. The reception could not have been warmer. Iwas glad to learn that a lot of the hostility from the Partition days haddissipated.

Saaz: As someone who hasmade Sindhis proud with your exceptional success, please suggest measures bywhich members of your community could enhance the way they are perceived.

Kishore: Sindhis are aremarkable people. There are very few ethnic groups in the world who havemanaged to succeed in all corners of the world. The Sindhis are one of them.Having visited most of the major cities in the world, I'm always pleasantlysurprised to see members of the Sindhi community thriving and succeeding in allcorners of the world. Indeed, I have first cousins in all corners of the world:in Suriname and Guyana in South America, in Texas and Florida in North America,in Ghana and Nigeria in Africa, in Japan and Hong Kong in East Asia, and ofcourse in Mumbai and Kolkata in India. I also have relatives in Europe. Theentrepreneurship of the Sindhi community is truly admirable.

In the next chapter of itsdevelopment, India will have to engage the rest of the world more. Its tradeand investment links with other countries will also increase. One of its majorassets as it plunges ever more deeply into globalisation will be the strong andsuccessful ethnic Indian communities overseas. Undoubtedly, the Sindhis willrank among some of the most successful Indians overseas. Their contributionsshould receive greater recognition within India.

Saaz: Your advice foryoung people who wish to follow a career in diplomacy?

Kishore: Diplomacy is oneof the best professions in the world to join. Since we live in a small andshrinking world, all countries must now make a major effort to understand othercountries and cultures all over the world. And the people who are best placedto do so are diplomats.

As I explain in my memoirs, Ihad no intentions of staying on in diplomacy, as I wanted to return to academiaafter graduating. However, I discovered diplomacy to be a more fulfillingprofession than academia. I realised that in trying to defend the interests ofa small country like Singapore in the international community, I was defendingan underdog. Ambassadors from smaller countries have to work harder thanambassadors from larger countries. Fortunately, with the help of reason, logicand charm (as I describe in my memoirs) I managed to succeed in furtheringSingapore’s interests in the United Nations and in the ASEAN community.

Golf proved to be very useful.Indeed, one reason why Southeast Asia, the most diverse corner on planet Earth,has had no wars in 50 years is that many of the Southeast Asian diplomats andleaders play golf with each other. This is also a lesson that South Asiancountries can learn from Southeast Asian countries: it’s important to investtime in developing personal connections with each other. Trust building andcooperation at the national level is incredibly difficult when there is nowarmth or trust on the interpersonal level.

aThis interview was published in Hindustan Times on 30 April 2025.

https://www.hindustantimes.com/books/kishore-mahbubani-india-will-have-to-engage-the-rest-of-the-world-more-101746012772995.html

https://www.hindustantimes.com/books/kishore-mahbubani-india-will-have-to-engage-the-rest-of-the-world-more-101746012772995.htmlApril 6, 2025

The launch of Susheel Gajwani's memoir Sunrise Over Valivade

When Susheel Gajwani sent me a manuscript with stories of his childhood in the Sindhi refugee camp at Valivade, Kolhapur, I knew that this was an important piece of Sindhi history and decided to work on it with him and publish it. Here is what I said when we launched the book at NCPA, Mumbai, on 5 April 2025.

You can read what Sindh studies scholar Nandita Bhavnani said about what makes SUNRISE OVER VALIVADE an important book at the launch on this link There's a reading by Menka Shivdasani, Susheel Gajwani and Nandita Bhavnani hereAnd here is a performance by Susheel Gajwani himself at the event.

February 5, 2025

Publisher Saaz Aggarwal’s first-person account of Susheel Gajwani’s book, ‘Sunrise Over Valivade’ in scroll.in

Saaz and Susheel on one of their many

Saaz and Susheel on one of their many zoom discussions during the course of

preparing the book for publication

in Jan 2025

SusheelGajwani’s book, Sunrise Over Valiwade, opens with the milk queue in arefugee camp. Mothers and grandmothers have brought their little ones – a ragged,squalling lot, some naked – and are waiting in line as milk is doled out from alarge, dirty, aluminium vessel. A man in a khaki uniform is pouring milk into dentedand tarnished tumblers with mechanical precision, filling each glass swiftlyand purposefully. The children grab their glasses and empty them hungrily.Another man stands beside them, snatching the empty glasses back and rinsingthem in a bucket of water. Hundreds of glasses are ‘washed’ in the same bucket.Susheel is waiting his turn.

What happensnext you must read for yourself in the book, all I can reveal for now is thatthe words and the descriptions bring alive much more than the wretched, forlornexistence, the grime, the pushing and shoving, the language barrier, theunfamiliar geography, the helpless dependence on others’ goodwill and charity. Susheel’sdismay, his attachment to his grandmother, the way she responds – especiallythe way she responds, an iconic manifestation of the Sindhi identity – made mewant to cry and ended up making me laugh. The first story in the manuscriptSusheel sent me some months ago, it filled me with delight, and energized me toput everything aside and start preparing it for publication.

Kolhapur’s Gandhinagar Camp forSindhi Partition refugees is largely unknown except to those associated with it.The most commonly referred list of Sindhi refugee camps in India at the end of1948 is from Dr. UT Thakur’s 1959 book Sindhi Culture (Sindhi Academy,New Delhi):

1. Ajmer Merwara at Deoli 10,200

2. Bombay 2,16,500

3. Baroda 10,700

4. Bikaner State 8,900

5. Jaipur State 33,200

6. Jodhpur State 11,800

7. Madhya Bharat 3,400

8. Former Rajasthan 15,800

9. Saurashtra Union 45,500

10. Vindhya Pradesh 15,400

11. Madhya Pradesh 81,400

Total 4,52,800

The Gandhinagar Camp is absentin this and other research about Sindhi refugees, as are many other locationsof the scattered population. In time, it would grow – as did the other camps –into a community of solid citizens who contributed substantially to the economyof the region. And this is where Susheel Gajwani was born, in the barrack hisfamily had been allotted, delivered by a daee from another refugeefamily.

Growing up in the camp, hearingthe sounds of his mother tongue – and even the melodies of Master Chandur andother Sindhi singers – spoken around him was one thing; integrating into thewider world outside was another. This book covers interesting aspects of both.

Susheel’s family came fromShahdadkot in Sindh and, growing up, he heard the elders reminisce withnostalgia of the places they had left behind. I peered into maps of Sindh tolocate the towns and villages Susheel named and found them all – except Korayoon.I asked around with no success and, finally, requested Nasir Aijaz. The award-winningPakistan media personality and founder and director of the redoubtable SindhCourier https://sindhcourier.com/ couldfind no trace of it.

“Seriously, Susheel? Korayoon?”I asked.

“Yes, Korayoon,” he repliedfirmly.

“Qambrani?”

“No.”

“Karira?”

“No!”

“Chakiyani?”

“Of course not, Saaz! Korayoon –that’s the name they spoke about. Often. Korayoon.”

Nasir reported back that villageKorayoon was not even on the survey list of the Revenue Department. Perhaps, hesaid, the name had been changed. Yes – perhaps it had. Because, when thenon-Muslims left Sindh, much changed. A new population arrived, making things difficultfor those left behind, regardless of their religion. Sindhi culture was mocked,Sindhi people were colonized, their efforts derided. Across the border,Hassomal had turned into Haresh; Sati into Sita. Kripps was emerging fromKripalani. How could we know what names were being changed in Sindh?

As adults, Susheel and hisbrother Shashi became professionally associated with different formats of massmedia. Discussing their childhood in a refugee community, the trauma of their people,and the courageous way in which it had been faced, they began asking round andreading up, and something they had always known came into focus. Their childhoodhome had in fact been built for Polish refugees of the Second World War, onland given by the Maharaja of Kolhapur, one of the Indian princes who followedthe lead of the Maharaja of Nawanagar, in arranging for shelter to the Polishwomen and children who had lost their families to the war.

Susheel’s family had arrived inValivade completely devastated. Wrenched from lives of comfort, they werethrown into wretched living conditions, and forced to live on charity. But thePolish refugees had arrived in Valivade a decade before them, after even moreintense ordeals in slave gulags.

In the 1990s, Susheel and Shashimade an effort to find local people from nearby villages who had beenassociated with Valivade camp, and came across Dadoba Lokhande, who introducedthem to Maruti Dashrath Bhosale, Shiva Gawli, Bandu Hari Awale and others whohad worked with the Polish refugees. They shared their memories, and these forma charming adjunct to this Sindhi story. Barbara Charuba kindly gave permissionto use her photos; more can be seen on https://www.polishexilesofww2.org/valivade-camp-india-part-4

Occasionally, dates came intoquestion. When exactly did the Gajwani family leave Sindh, when did they arrivein the Bombay docks, when were they herded into trains that took them toValivade?

Clarifying dates is always achallenge while tracing the history of families from a beleaguered communitywhose focus was on surviving and moving on. Over hundreds of interviews, I’vemet people who did not want actual years to be known, sometimes for legalreasons, sometimes social appearances. Fudging years was an easy way out. Mostcommonly, as with Susheel’s family, overwhelmed by the demands of survival anddaily existence, people simply did not kept track. We turned to archival accounts.

After the 6 January 1948 pogromin Karachi, the Bombay docks became overrun with refugees who had fled theirancestral homeland and wished to live close to Bombay where they could earn forthemselves rather than in faraway Ulhasnagar on government doles. According toa news report on 28 February 1948, more than 5000 were squatting on thequaysides of No 18 and No 19, Alexandra Dock. Crime was escalating, and the sanitationsituation put the entire city’s health at risk. On 4 March 1948, theDirectorate of Evacuation was preparing to receive 5000 refugees per day. Therewere 12,000 awaiting dispersal, and on an average about 2000 were being removeddaily. Do the figures quoted really add up? Either way, oral history interviewsconfirm that mass accommodation was being identified in other parts of India,and the railways were arranging refugee-special trains to Aswali (Deolali), Avadi(Chennai) and other places. It was a news report which indicated the month andyear in which Susheel’s family – his parents, grandparents, great-grandparents andthe extended families – arrived at Valivade.

Very soon after Sunrise overValivade went online a few days ago, I received an email forward, stronglyopinionated and responding with authority to the excerpt on https://blackandwhitefountain.com/sunrise-over-valivade/#.It lamented the incident as questionable and reflecting the writer’s urge forself-aggrandisement. The Sindhis, the email went on, were greatly appreciatedby other communities, and India as a whole! Not only that, but Sindhstands at the very centre of the Indian national anthem and even forms the stemof the word India and Hindu! The writer of the email himself, an importantperson, specified that, as a Sindhi, he had received nothing but affection andrespect across the state even though he is not fluent in Marathi.

I will admit that I rolled myeyes a bit but phoned Susheel at once to check, “Was that the only time anyonehit you?”

He replied indignantly, “It wasnot. I was beaten up many times when I was in college!”

“Ok – were you the only Sindhiwho faced that treatment, Susheel?”

“No, no, no, there were otherswho did.”

“Ok – did all the Sindhiyoungsters get beaten up?”

“Of course not, Saaz! Most ofthem tried to stay out of trouble. But there were some of us who stood up forourselves.”

This episode made me ponder (yetagain) how very little I know about this fascinating community despite all theyears of listening, thinking and trying to understand. Yes – by and large theywanted to be low key and just get on with the job – but does that mean we shouldpretend that people who are poised to bite back when provoked do not exist?That we can’t make space for that mantra of our times, ‘diversity’?

It took me back to the time whenSusheel, 5 or so years old, stood clutching his beloved Amma’s loose-flowingpajama as they waited in line. The spectre of this hungry child, craving formilk, the ultimate luxury, haunted me right through the process of working withhim on the book. How had he survived? What traces of those years remainedwithin?

First appeared in https://scroll.in/article/1078447/a-p... on 4 February 2025

February 1, 2025

Review of Sunrise Over Valivade in Hindustan Times Jan 2025

‘Sunrise Over Valivade’: a historical record and an intimate family account

After Partition, the Gajwanifamily left their business and lands near Shahdadkot in the north of Sindh,travelling through a tormented, blood-stained terrain to Karachi, where they boardeda ship to Bombay along with crowds of others like them. In Bombay, theyremained for several days on the Alexandra Docks, where the ship had dischargedthem, somehow eking together a living, unsure of what to do next. One day, theywere removed, along with the large group of others who had also made atemporary home on the docks, herded into a train, and deposited in Valivade. Itwas in the Sindhi refugee camp at Valivade that Susheel Gajwani was born andraised. His memoir, Sunrise Over Valivade, is a historical record and anintimate family account.

While capturing the resilience,struggles, and identity of Sindhi Hindus displaced from their homeland, thisbook is also the first recorded instance of the presence of a Sindhi refugeecamp near Kolhapur, reflecting the sad absence of comprehensive informationabout the Sindh Partition experience and the glaring gaps of accurate knowledgeabout it.

Another fascinating aspect ofthe book is that the camp was originally built for Polish refugees during WorldWar II. The context of this from online sources, appended with Susheel’s interviewsof local people who had served in the camp during that time, provide theopportunity to muse on the two sets of refugees rendered homeless in the sameera of history. While the Poles experienced more atrocities during the war thanthe Sindhis did during Partition, the Poles were given a chance to rebuild withdignity, while the Sindhis had to fight for even basic recognition and maketheir own way.

Susheel was born in the Valivaderefugee camp, a world where Sindhi culture and traditions were kept alive, butwhere the reality of having lost their homeland was inescapable. His family andother refugees had fled escaping violence and uncertainty. Many had left behindtheir land, homes, businesses, and even close relationships. He recalls growingup in a purely Sindhi environment within the camp – where everyone spokeSindhi, ate Sindhi food, and celebrated Sindhi festivals – and experiencing thefeeling of stark alienation outside the camp. This paradox of being in theirown country yet clearly not accepted, is a recurring theme. Sindhi refugeeswere not given a province of their own, unlike other displaced communitiesafter Partition. The Indian government saw them as temporary settlers, refusingto grant them official recognition as a linguistic group with rights.

Despite these challenges,Sindhis rebuilt their lives. Susheel’s family, like many others, started smallbusinesses, with his father and uncles selling onions, potatoes, and ginger inKolhapur's markets. They worked hard to earn respect, but ingrained prejudicepersisted.

By grounding his narrative insmall, intimate moments, Susheel makes history personal, allowing readers tofeel the heartbreak, humiliation, and resilience of the displaced community. Througha series of vignettes, he captures the sounds, smells, and emotions of refugeelife. In A Glass of Milk a child’s anxiety over whether there will beenough milk for him in the government ration line serves as a metaphor foruncertainty and scarcity. Other vignettes, such as Laundry and ThePhotograph, bring out the small yet significant aspects of life in therefugee community, showing how people tried to preserve their dignity andtraditions despite their circumstances. Eyyy Nirvashya! highlights thesocial stigma that followed Sindhi refugees long after they had left the camps.Susheel’s graphic description of verbal abuse by a policeman, followed by a physicalassault when he answered back, reveals another untold aspect of the Sindhistory.

Susheel also details theadaptation to Maharashtrian customs, as Sindhi women began wearing saris andcooking local dishes. Over time, the displaced Sindhis integrated into thelocal society, but never stopped longing for their lost homeland. A crucialmoment in the book is the realization that Sindh had changed too. The land leftbehind had been transformed, with migrants from other regions replacing SindhiHindus. This severed the last ties to their roots, making return impossible.

While thisbook contributes to the neglected history of Sindhi refugees, it alsohighlights larger themes of displacement, cultural erosion, and resilience, makingit a valuable contribution to Partition literature and diaspora studies.

If I hadto look for inadequacies – well, it lacks women’s perspective and women’sstories. It overlooks the internal class and caste divisions within the Sindhicommunity. Many wealthier Sindhi Hindus were able to migrate to Mumbai, Pune,or settle in other countries where Sindhi traders have had a presence since the1850s, while poorer refugees were left in camps for years. Sindhi Hindu societyis not homogeneous, and social hierarchies existed even in exile. However,these are gaps that must be filled by other books.

It was a pleasure for me to workwith Susheel on his stories, weaving historical research into the personal vignettes and oral histories, ignitingan awareness in him that could be passed on to his readers, of the evolving identityof a community for which multi-faith worship was once the only way of life they knew.

It also brought me a strong reminderof the realities of the day, impossible to deny, yet waved away as inconsequentialby many in this materially successful community:

- Why did the Indian government refuse to grantSindhis a state?

- Why were Sindhis not included in the linguisticreorganization of India?

- How did early government policies contribute tothe decline of Sindhi language and identity in India, and can the sincereefforts being made today ever compensate?

- Will the shallow stereotypes with which Sindhisare perceived in India – and as a consequence many other countries where thediaspora is settled too – ever be replaced with the nuanced realities, whichbooks such as these provide?

First appeared in Hindustan Times on 29 January 2025

Sindhi showcased as a regional language at Hyderabad Literary Festival January 2025

In January 2025, the Hyderabad Literary Festival(HLF) featured Sindhi as its regional language — a gesture thatmeant a great deal to us, as there is no region in India today that Sindhi is nativeto. At noon on the festival’s opening day, scholars RitaKothari , NanditaBhavnani , and moderator SoniWadhwa led a deeply engaging discussion titled Fragmented Selves: SindhiLanguage, Literature and History.

Their conversationtraced the journeys of Sindhi identity, displacement, and memory. Ritareflected on her students’ growing interest in Sindh Studies; Nandita sharedinsights from her research, including her 2003 visit to Sindh, where sherealised how many pre-Partition trends were already shaping the changes thatPartition later intensified. The audience — both Sindhi and non-Sindhi — joinedin with thoughtful questions and perspectives.

Later that afternoon, AnjuMakhija and MenkaShivdasani spoke ina session on Story, Voice, and Verse, reading from their Englishtranslations of Sindhi poetry. Moderator Soni Wadhwa closed by reading a Sindhipoem herself, to the audience’s delight.

That evening,delegates gathered for a dinner hosted by the Lithuanian Embassy — a warmopportunity for exchange among participants including Nandita Bhavnani, RitaKothari, Menka Shivdasani, Anju Makhija, Subhadra Anand,and Saaz Aggarwal, with festival directors Vijay Kumar Tadakamallaand Amita Desai, and Lithuanian Ambassador Her Excellency DianaMickevičienė.

A Shared Heritage —in Hyderabad, India

What moved me most washow the Sindh Courier covered the event. Its editor, Nasir Aijaz,wrote that the festival took place in “Indian Hyderabad” — because of course,there is another Hyderabad, in Sindh, where many of our ancestors came from. Mymother was born and grew up there, and experienced firsthand the loss thatPartition brought. How poignant, then, that the first Indian literary festivalto celebrate Sindhi should be in a city of that same name.

Even so, the ironyremained: the HLF banner had Sindhi written in Devanagari script,because few on this side of the border can now read the original Sindhi script.

Our Session:Rediscovering a Scattered Identity

On 26 January, SubhadraAnand and I (Saaz Aggarwal)spoke on Little-Known Aspects of Sindhi Culture — touching on:

The prejudice and stereotypes Sindhis still face. The Partition experience, and how little of Sindh finds mention in mainstream Partition narratives. The irony of this neglect, given Sindh’s multi-faith culture, its early global trade networks, and its scattering a century before Partition. The loss of history and language, alongside the poetry, philosophy, and visual and performing arts that shaped Sindh.The Sindhi community’s enduring qualities: adaptability, resilience, hard work, hospitality, and philanthropy.And the ongoing efforts to restore cultural identity, including Dr. Anand’s ambitious Jhulelal Tirthdham project in Kachchh.

The prejudice and stereotypes Sindhis still face. The Partition experience, and how little of Sindh finds mention in mainstream Partition narratives. The irony of this neglect, given Sindh’s multi-faith culture, its early global trade networks, and its scattering a century before Partition. The loss of history and language, alongside the poetry, philosophy, and visual and performing arts that shaped Sindh.The Sindhi community’s enduring qualities: adaptability, resilience, hard work, hospitality, and philanthropy.And the ongoing efforts to restore cultural identity, including Dr. Anand’s ambitious Jhulelal Tirthdham project in Kachchh.

It was a privilege toshare the stage with friends and colleagues who have long worked to preserveand reinterpret Sindhi culture — and to witness the growing recognition ofSindh’s place in India’s and the world’s story.

Read more: Sindh Courier coverage of the Hyderabad Literary Festival

Launch of Sunrise Over Valivade at Hyderabad Literature Festival 2025

Event organizer, audience member, Saaz Aggarwal, Susheel Gajwani, Menka Shivdasani, Barkha Khushalani, Subhadra Anand, audience member

Event organizer, audience member, Saaz Aggarwal, Susheel Gajwani, Menka Shivdasani, Barkha Khushalani, Subhadra Anand, audience member