Saaz Aggarwal's Blog, page 4

May 15, 2017

Perhaps Tomorrow by Pooranam Elayathamby with Richard Anderson

A hug for the kaamwali baiA blurb on the back of this book attempts to lure readers seeking greedy shudders at the horrors of domestic servitude in a barbaric country. There is an underlying promise that we might be gratified to find that we treat our own ‘servants’ in a generous and praiseworthy manner.

Despite the titillating invitation, this book is not merely about how badly Pooranam’s employers treated her. Like the best kind of memoir, it presents more than just a few aspects of a person’s life. The authors of this book weave different narrative strands together, skilfully introducing social, historical and political context, and evocative pictures emerge.

Despite the titillating invitation, this book is not merely about how badly Pooranam’s employers treated her. Like the best kind of memoir, it presents more than just a few aspects of a person’s life. The authors of this book weave different narrative strands together, skilfully introducing social, historical and political context, and evocative pictures emerge.

Kommathurai, on the east coast of Sri Lanka, is a Hindu town that follows the social segregation of traditional Hindu casteism. Pooranam herself is of the ‘laundry people’, the middle daughter of five. Life is sweet and beautiful. Then tragedy strikes and her father dies under his bullock-cart, leaving her mother with five little girls and no source of income. A strong and enterprising woman, Kanagamma starts her own business. Part of this is taking eight-year-old Pooranam and seven-year-old Sodi out of school and putting them to work, carrying thirty-kilo sacks of rice from the wholesaler’s village, cooking, drying, re-packing and selling the processed rice from door to door. Neighbours whisper that farm animals get better treatment.

When Pooranam is privileged to capture the attention of the town’s most eligible bachelor and he marries her, the book gives insights into traditional or cultural male entitlement where helping yourself to your wife’s belongings, violence against her, and sexual relationships with other women are considered acceptable. In counterpoint are the quality of dependence and attachment a strong and intelligent woman can experience despite these ignominies.

Set in the jungles of northern Sri Lanka at the height of the LTTE insurgency, this book presents the Tamil side of the story: the marginalization and persecution of a people historically perceived as subordinate. In the jungle camp, we observe how ordinary people suffer in a political battle. Kommathurai is abandoned, then ravaged; Pooranam is left a widow with three children before she turns thirty.

Meanwhile, the housemaid market in the Arabian Gulf, initially restricted to non-idol worshipping monotheists had expanded so much that it was giving ‘religious’ fussing a miss. Pooranam took employment contracts, aiming to convert, as many did, domestic drudgery into cement homes, proper furniture and a future for her children – though this would entail sad years separated from them.

After many adventures, much intense hard work, getting renamed Sandy, learning about different aspects of life in the desert as well as all kinds of new recipes – this beautiful, intelligent, determined, enterprising and hardworking woman has her happily-ever-after. Pooranam marries Dick, an American professor of architecture at Kuwait University. She enters a phase of stability and comfort; he helps her lead her children to a better life, and in time they write this book together. It turns out to be well written and engaging, and Pooranam’s warmth and depth of character shine through. While the contextualisation and odd literary reference appear to be in the voice of the architecture professor, it is surprising that the book is littered with racial stereotyping: Arabs are lazy; Egyptians are stingy; the British are not expected to be arrogant and mean-spirited.

Besides all this, this book could serve as a useful handbook for the Indian Madam. It could inspire us to consider that the wretch who stands between us and the jhadu/pocha/bartan might have left terrible times behind at home her family from starvation. She misses her children terribly. So when she throws the food out because she misunderstood what you said, don’t scream at her in rage. Laugh, give her a hug, and gently explain what you actually meant so that she’s motivated to get it right next time. This is what Pooranam’s Indian employers, the Khans, actually did.

This review was written for Hindustan Times and appeared on Saturday 13 May 2017. It can be viewed online here

Despite the titillating invitation, this book is not merely about how badly Pooranam’s employers treated her. Like the best kind of memoir, it presents more than just a few aspects of a person’s life. The authors of this book weave different narrative strands together, skilfully introducing social, historical and political context, and evocative pictures emerge.

Despite the titillating invitation, this book is not merely about how badly Pooranam’s employers treated her. Like the best kind of memoir, it presents more than just a few aspects of a person’s life. The authors of this book weave different narrative strands together, skilfully introducing social, historical and political context, and evocative pictures emerge.Kommathurai, on the east coast of Sri Lanka, is a Hindu town that follows the social segregation of traditional Hindu casteism. Pooranam herself is of the ‘laundry people’, the middle daughter of five. Life is sweet and beautiful. Then tragedy strikes and her father dies under his bullock-cart, leaving her mother with five little girls and no source of income. A strong and enterprising woman, Kanagamma starts her own business. Part of this is taking eight-year-old Pooranam and seven-year-old Sodi out of school and putting them to work, carrying thirty-kilo sacks of rice from the wholesaler’s village, cooking, drying, re-packing and selling the processed rice from door to door. Neighbours whisper that farm animals get better treatment.

When Pooranam is privileged to capture the attention of the town’s most eligible bachelor and he marries her, the book gives insights into traditional or cultural male entitlement where helping yourself to your wife’s belongings, violence against her, and sexual relationships with other women are considered acceptable. In counterpoint are the quality of dependence and attachment a strong and intelligent woman can experience despite these ignominies.

Set in the jungles of northern Sri Lanka at the height of the LTTE insurgency, this book presents the Tamil side of the story: the marginalization and persecution of a people historically perceived as subordinate. In the jungle camp, we observe how ordinary people suffer in a political battle. Kommathurai is abandoned, then ravaged; Pooranam is left a widow with three children before she turns thirty.

Meanwhile, the housemaid market in the Arabian Gulf, initially restricted to non-idol worshipping monotheists had expanded so much that it was giving ‘religious’ fussing a miss. Pooranam took employment contracts, aiming to convert, as many did, domestic drudgery into cement homes, proper furniture and a future for her children – though this would entail sad years separated from them.

After many adventures, much intense hard work, getting renamed Sandy, learning about different aspects of life in the desert as well as all kinds of new recipes – this beautiful, intelligent, determined, enterprising and hardworking woman has her happily-ever-after. Pooranam marries Dick, an American professor of architecture at Kuwait University. She enters a phase of stability and comfort; he helps her lead her children to a better life, and in time they write this book together. It turns out to be well written and engaging, and Pooranam’s warmth and depth of character shine through. While the contextualisation and odd literary reference appear to be in the voice of the architecture professor, it is surprising that the book is littered with racial stereotyping: Arabs are lazy; Egyptians are stingy; the British are not expected to be arrogant and mean-spirited.

Besides all this, this book could serve as a useful handbook for the Indian Madam. It could inspire us to consider that the wretch who stands between us and the jhadu/pocha/bartan might have left terrible times behind at home her family from starvation. She misses her children terribly. So when she throws the food out because she misunderstood what you said, don’t scream at her in rage. Laugh, give her a hug, and gently explain what you actually meant so that she’s motivated to get it right next time. This is what Pooranam’s Indian employers, the Khans, actually did.

This review was written for Hindustan Times and appeared on Saturday 13 May 2017. It can be viewed online here

Published on May 15, 2017 18:49

February 20, 2017

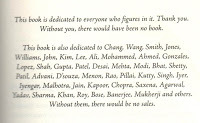

The Silliest Autobiography in the World by PG Bhaskar

The Silliest Review in the World

Finally, a book that really does deserve to go into a time capsule, carefully placed in a steel cylinder and buried deep into the earth to await eager historians from future generations or from outer space. Before this, Bhaskar wrote two books which mysteriously turned out to be both modestly-successful as well as best-selling. Somehow, he remained unknown to billions. Now he has written a silly autobiography but structured it meticulously. Bhaskar, the son of an LIC ‘odditor’ and himself a fully-qualified chartered accountant, opens with a chapter called 1963, by a fascinating coincidence, the very year in which he was born! The next chapter is 1964, then 1965, then 1966, and all the way up to 2015. Through the life experiences of the unknown Bhaskar, the eager historian of the future will learn how people lived between 1963 and 2015, especially those who lived in Madras, Udupi, Delhi, Bombay, Coimbatore and, erm, Dubai. They will also obtain some mildly useful information about movies, cricket, politics and entertainment. From an anthropological perspective, Bhaskar gives an insight into transitions in his world. To begin with, people would hang onto their toothbrushes, discarding them only after the bristles began to resemble a strip of savannah grassland that had been viciously trampled upon by a herd of stampeding elephants. They would stealthily pocket cutlery from aeroplanes. Then, as the socio-economic environment advanced, they began buying whole sets of crockery which sadly did not last as long as the stolen cutlery. They developed quaint professional rites of passage called ‘mini-offsites’ at which overpaid bank officials engaged with ‘escorts’ and later, exposed on Facebook, bought expensive presents to placate their enraged spouses.

Finally, a book that really does deserve to go into a time capsule, carefully placed in a steel cylinder and buried deep into the earth to await eager historians from future generations or from outer space. Before this, Bhaskar wrote two books which mysteriously turned out to be both modestly-successful as well as best-selling. Somehow, he remained unknown to billions. Now he has written a silly autobiography but structured it meticulously. Bhaskar, the son of an LIC ‘odditor’ and himself a fully-qualified chartered accountant, opens with a chapter called 1963, by a fascinating coincidence, the very year in which he was born! The next chapter is 1964, then 1965, then 1966, and all the way up to 2015. Through the life experiences of the unknown Bhaskar, the eager historian of the future will learn how people lived between 1963 and 2015, especially those who lived in Madras, Udupi, Delhi, Bombay, Coimbatore and, erm, Dubai. They will also obtain some mildly useful information about movies, cricket, politics and entertainment. From an anthropological perspective, Bhaskar gives an insight into transitions in his world. To begin with, people would hang onto their toothbrushes, discarding them only after the bristles began to resemble a strip of savannah grassland that had been viciously trampled upon by a herd of stampeding elephants. They would stealthily pocket cutlery from aeroplanes. Then, as the socio-economic environment advanced, they began buying whole sets of crockery which sadly did not last as long as the stolen cutlery. They developed quaint professional rites of passage called ‘mini-offsites’ at which overpaid bank officials engaged with ‘escorts’ and later, exposed on Facebook, bought expensive presents to placate their enraged spouses.

At a personal level, Bhaskar reveals himself as one who, to the great merriment of his friends and classmates, faints. He faints quite often! Let us hope he is not going to faint when he reads this review. Or, perhaps the friends could get together and sell tickets in anticipation.While this book could emerge winner in a time-capsule competition, it could also gain esteem as entertainment to the present-day reader. I was laughing very loudly, and my husband, lying in bed next to me and waiting for his turn, became increasingly agitated, muttering to himself, “Who is this Bhaskar! Wait till I get my hands on him,” etc.

At a personal level, Bhaskar reveals himself as one who, to the great merriment of his friends and classmates, faints. He faints quite often! Let us hope he is not going to faint when he reads this review. Or, perhaps the friends could get together and sell tickets in anticipation.While this book could emerge winner in a time-capsule competition, it could also gain esteem as entertainment to the present-day reader. I was laughing very loudly, and my husband, lying in bed next to me and waiting for his turn, became increasingly agitated, muttering to himself, “Who is this Bhaskar! Wait till I get my hands on him,” etc.

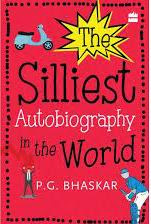

To be honest, I started cackling away right from the dedication which is really very funny. Towards the end of the book, there is an explanation which I was glad to read, because without it the dedication would have remained a mystery to the future historian unless Bhaskar’s publishers had contrived to also squeeze a few c1980s telephone directories into the capsule to provide context. It occurred to me that the enterprising publishers might also want to introduce footnotes for the puzzled historians wondering why the trend of women taking to the study of economics in droves should be called The ‘Rajan’ Effect. And how come, when the family driver in Udupi was Bhavani Shankar, in Delhi too the family had a driver with the same name! And the ‘household help’ in Chennai was also called Bhavani! Could this be coincidence? Or was Bhavani a generic of Bhaskar’s time? So – footnotes, please, dear publishers.

To be honest, I started cackling away right from the dedication which is really very funny. Towards the end of the book, there is an explanation which I was glad to read, because without it the dedication would have remained a mystery to the future historian unless Bhaskar’s publishers had contrived to also squeeze a few c1980s telephone directories into the capsule to provide context. It occurred to me that the enterprising publishers might also want to introduce footnotes for the puzzled historians wondering why the trend of women taking to the study of economics in droves should be called The ‘Rajan’ Effect. And how come, when the family driver in Udupi was Bhavani Shankar, in Delhi too the family had a driver with the same name! And the ‘household help’ in Chennai was also called Bhavani! Could this be coincidence? Or was Bhavani a generic of Bhaskar’s time? So – footnotes, please, dear publishers.

There are also long passages where the humour lags and verses which strike a wrong note. So, to end, a minor stricture for the author from an almost-fan of somewhat similar vintage and demography:

Finally, a book that really does deserve to go into a time capsule, carefully placed in a steel cylinder and buried deep into the earth to await eager historians from future generations or from outer space. Before this, Bhaskar wrote two books which mysteriously turned out to be both modestly-successful as well as best-selling. Somehow, he remained unknown to billions. Now he has written a silly autobiography but structured it meticulously. Bhaskar, the son of an LIC ‘odditor’ and himself a fully-qualified chartered accountant, opens with a chapter called 1963, by a fascinating coincidence, the very year in which he was born! The next chapter is 1964, then 1965, then 1966, and all the way up to 2015. Through the life experiences of the unknown Bhaskar, the eager historian of the future will learn how people lived between 1963 and 2015, especially those who lived in Madras, Udupi, Delhi, Bombay, Coimbatore and, erm, Dubai. They will also obtain some mildly useful information about movies, cricket, politics and entertainment. From an anthropological perspective, Bhaskar gives an insight into transitions in his world. To begin with, people would hang onto their toothbrushes, discarding them only after the bristles began to resemble a strip of savannah grassland that had been viciously trampled upon by a herd of stampeding elephants. They would stealthily pocket cutlery from aeroplanes. Then, as the socio-economic environment advanced, they began buying whole sets of crockery which sadly did not last as long as the stolen cutlery. They developed quaint professional rites of passage called ‘mini-offsites’ at which overpaid bank officials engaged with ‘escorts’ and later, exposed on Facebook, bought expensive presents to placate their enraged spouses.

Finally, a book that really does deserve to go into a time capsule, carefully placed in a steel cylinder and buried deep into the earth to await eager historians from future generations or from outer space. Before this, Bhaskar wrote two books which mysteriously turned out to be both modestly-successful as well as best-selling. Somehow, he remained unknown to billions. Now he has written a silly autobiography but structured it meticulously. Bhaskar, the son of an LIC ‘odditor’ and himself a fully-qualified chartered accountant, opens with a chapter called 1963, by a fascinating coincidence, the very year in which he was born! The next chapter is 1964, then 1965, then 1966, and all the way up to 2015. Through the life experiences of the unknown Bhaskar, the eager historian of the future will learn how people lived between 1963 and 2015, especially those who lived in Madras, Udupi, Delhi, Bombay, Coimbatore and, erm, Dubai. They will also obtain some mildly useful information about movies, cricket, politics and entertainment. From an anthropological perspective, Bhaskar gives an insight into transitions in his world. To begin with, people would hang onto their toothbrushes, discarding them only after the bristles began to resemble a strip of savannah grassland that had been viciously trampled upon by a herd of stampeding elephants. They would stealthily pocket cutlery from aeroplanes. Then, as the socio-economic environment advanced, they began buying whole sets of crockery which sadly did not last as long as the stolen cutlery. They developed quaint professional rites of passage called ‘mini-offsites’ at which overpaid bank officials engaged with ‘escorts’ and later, exposed on Facebook, bought expensive presents to placate their enraged spouses.

At a personal level, Bhaskar reveals himself as one who, to the great merriment of his friends and classmates, faints. He faints quite often! Let us hope he is not going to faint when he reads this review. Or, perhaps the friends could get together and sell tickets in anticipation.While this book could emerge winner in a time-capsule competition, it could also gain esteem as entertainment to the present-day reader. I was laughing very loudly, and my husband, lying in bed next to me and waiting for his turn, became increasingly agitated, muttering to himself, “Who is this Bhaskar! Wait till I get my hands on him,” etc.

At a personal level, Bhaskar reveals himself as one who, to the great merriment of his friends and classmates, faints. He faints quite often! Let us hope he is not going to faint when he reads this review. Or, perhaps the friends could get together and sell tickets in anticipation.While this book could emerge winner in a time-capsule competition, it could also gain esteem as entertainment to the present-day reader. I was laughing very loudly, and my husband, lying in bed next to me and waiting for his turn, became increasingly agitated, muttering to himself, “Who is this Bhaskar! Wait till I get my hands on him,” etc.

To be honest, I started cackling away right from the dedication which is really very funny. Towards the end of the book, there is an explanation which I was glad to read, because without it the dedication would have remained a mystery to the future historian unless Bhaskar’s publishers had contrived to also squeeze a few c1980s telephone directories into the capsule to provide context. It occurred to me that the enterprising publishers might also want to introduce footnotes for the puzzled historians wondering why the trend of women taking to the study of economics in droves should be called The ‘Rajan’ Effect. And how come, when the family driver in Udupi was Bhavani Shankar, in Delhi too the family had a driver with the same name! And the ‘household help’ in Chennai was also called Bhavani! Could this be coincidence? Or was Bhavani a generic of Bhaskar’s time? So – footnotes, please, dear publishers.

To be honest, I started cackling away right from the dedication which is really very funny. Towards the end of the book, there is an explanation which I was glad to read, because without it the dedication would have remained a mystery to the future historian unless Bhaskar’s publishers had contrived to also squeeze a few c1980s telephone directories into the capsule to provide context. It occurred to me that the enterprising publishers might also want to introduce footnotes for the puzzled historians wondering why the trend of women taking to the study of economics in droves should be called The ‘Rajan’ Effect. And how come, when the family driver in Udupi was Bhavani Shankar, in Delhi too the family had a driver with the same name! And the ‘household help’ in Chennai was also called Bhavani! Could this be coincidence? Or was Bhavani a generic of Bhaskar’s time? So – footnotes, please, dear publishers.There are also long passages where the humour lags and verses which strike a wrong note. So, to end, a minor stricture for the author from an almost-fan of somewhat similar vintage and demography:

Bhaskar: your poems are not short or too longThis review was written for Hindustan Times and appeared on Saturday 18 February 2017. It can be viewed online here.

But they’re neither doggerel nor ditty nor song.

Your ‘limericks’ rhyme

And the jokes are just fine

But the metre, dear chap, is all wrong.

Published on February 20, 2017 02:19

April 26, 2016

With a little help from my friends by Dev Lahiri

Energetic mud-fest

This is the depressing story of a brilliant man who faced many struggles. Though he writes with affection and gratitude of certain people and events, the persecution he describes at different points of his career appears to have dominated his life. His heart condition resulted in numerous dramatic collapses and hospital internments. It is also unfortunate that Dev Lahiri, a Rhodes Scholar and member of the heyday staff of Oxford University Press, has his memoirs strewn with proofreading and design disasters. This book has 222 pages, of which 66 are devoted to the horrors he faced while trying to bring reforms to The Lawrence School, Lovedale, between 1991 and 2000. Later, at Welham Boys’ School, Dehradun, things went bad for him again. Lahiri describes his victimisation in detail, blithely naming perpetrators and valiantly trying to clear his reputation with an energetic mud-fest.This review is not concerned with what actually happened, but cannot help observing that the inaccuracy and exaggeration in the book reduces its credibility. Lahiri sneers at a career in marketing, mocking the enthusiastic selling of soap. However, his book exposes him as a master of the glib half-truth. A few examples follow.He says he gave up his job as a tea planter in a few weeks because: “I just felt uncomfortable dealing with plants. I realized I needed to do something with people.” Hmm! A tea planter’s job requires sound fundamentals of agriculture, but it is in fact through the management of labour in the field and factory that the job gets done and it is actually more about people than plants. He also claims to have been the first headmaster of Lawrence “to have actually allowed” a girl student to lead the Founders Day Parade. Not true. Rohini Gopalan, a girl student, led the parade in May 1977.Lahiri writes, “My daughter was followed into the town, her photos taken and morphed. Matters got worse. Anonymous letters started arriving addressed to the student body, accusing me, among other things, of sleeping with the lady teachers and Indrani of sleeping with the men.” But in the 1990s, morphing photos was still only science fiction! Even if we allow that a headmaster might have inadvertently used an anachronism and his daughter had actually felt disgraced by misuse of her photo, by what standard could anonymous letters, however scurrilous, make matters worse? Lahiri also quotes a report which states that it was he who made Lawrence “one of the most famous schools of the country”. Well: Lawrence School, Lovedale, was founded in 1858. When I joined, in 1971, it had long been recognized as one of the best schools in India. Every institution has its ups and downs, consequent on the people who lead and manage it. Evaluation and improvement may vary in consistency but they are continuous processes, never the work of just one person. This memoir is neither a work of literature nor a source of inspiration to coming generations. When slotted as a ‘tell-all exposé ’, it could provoke a careful reader to question whether the author (even if his intentions were blameless) had the emotional strength and stability required to implement reforms effectively.

This is the depressing story of a brilliant man who faced many struggles. Though he writes with affection and gratitude of certain people and events, the persecution he describes at different points of his career appears to have dominated his life. His heart condition resulted in numerous dramatic collapses and hospital internments. It is also unfortunate that Dev Lahiri, a Rhodes Scholar and member of the heyday staff of Oxford University Press, has his memoirs strewn with proofreading and design disasters. This book has 222 pages, of which 66 are devoted to the horrors he faced while trying to bring reforms to The Lawrence School, Lovedale, between 1991 and 2000. Later, at Welham Boys’ School, Dehradun, things went bad for him again. Lahiri describes his victimisation in detail, blithely naming perpetrators and valiantly trying to clear his reputation with an energetic mud-fest.This review is not concerned with what actually happened, but cannot help observing that the inaccuracy and exaggeration in the book reduces its credibility. Lahiri sneers at a career in marketing, mocking the enthusiastic selling of soap. However, his book exposes him as a master of the glib half-truth. A few examples follow.He says he gave up his job as a tea planter in a few weeks because: “I just felt uncomfortable dealing with plants. I realized I needed to do something with people.” Hmm! A tea planter’s job requires sound fundamentals of agriculture, but it is in fact through the management of labour in the field and factory that the job gets done and it is actually more about people than plants. He also claims to have been the first headmaster of Lawrence “to have actually allowed” a girl student to lead the Founders Day Parade. Not true. Rohini Gopalan, a girl student, led the parade in May 1977.Lahiri writes, “My daughter was followed into the town, her photos taken and morphed. Matters got worse. Anonymous letters started arriving addressed to the student body, accusing me, among other things, of sleeping with the lady teachers and Indrani of sleeping with the men.” But in the 1990s, morphing photos was still only science fiction! Even if we allow that a headmaster might have inadvertently used an anachronism and his daughter had actually felt disgraced by misuse of her photo, by what standard could anonymous letters, however scurrilous, make matters worse? Lahiri also quotes a report which states that it was he who made Lawrence “one of the most famous schools of the country”. Well: Lawrence School, Lovedale, was founded in 1858. When I joined, in 1971, it had long been recognized as one of the best schools in India. Every institution has its ups and downs, consequent on the people who lead and manage it. Evaluation and improvement may vary in consistency but they are continuous processes, never the work of just one person. This memoir is neither a work of literature nor a source of inspiration to coming generations. When slotted as a ‘tell-all exposé ’, it could provoke a careful reader to question whether the author (even if his intentions were blameless) had the emotional strength and stability required to implement reforms effectively.This review was written for Hindustan Times and appeared on Saturday 24 April 2016. It can be viewed online here.

Published on April 26, 2016 00:01

April 15, 2016

Forgotten Stories from my Village, Harwai by Hari Govind Narayan Dubey

A precious but forgotten world

One evening a few days ago, sitting on the warm parapet to enjoy the unique charms of Marine Drive, Mumbai, we noticed two buildings across the road: Firdaus and Ganga Vihar.

One evening a few days ago, sitting on the warm parapet to enjoy the unique charms of Marine Drive, Mumbai, we noticed two buildings across the road: Firdaus and Ganga Vihar.

Why would anyone name a Marine Drive art deco building facing the Arabian Sea “Ganga Vihar”? As soon as the thought entered my mind, I realised with a pleasant jolt of surprise that I did know who must have done so. It had to have been Lal Singh and Man Singh, the Rajput brothers who had come to Bombay from Mainpuri District in the erstwhile United Provinces in 1910 or thereabouts, to earn their living.

I heard about Lal Singh and Man Singh from Hari Govind Narayan Dubey in the course of working with him to produce his book Forgotten Stories from my Village, Harwai .

The book tells the story of his father’s life and work in and around the Mainpuri District in the decades leading up to Independence. Dubey is a skilled storyteller and his book is more than just the life of Pandit Ram Narayan Azad. It is a tribute to the many brave men and women who sacrificed everything they had to their vision of an India where every citizen would lead a life of dignity and choice. Their stories have long faded away, and replaced by simplistic icons such as ‘Mahatma Gandhi’ and ‘Chacha Nehru’. They give charming personal views into life in an Indian village and involvement in various aspects of India’s freedom struggle.

Lal Singh and Man Singh found employment with a wealthy Parsi gentleman who owned one of the prominent jewellery stores in Bombay. Dubey told me that the Parsi gentleman lived in a building of his own, Firdaus, on Marine Drive. However, he hesitated in mentioning the name in the book since he, ninety-two years old, felt it was a risk to put into print any information which he could not verify. What was relevant to the story was that it was through them that Pandit Ram Narayan Azad got the opportunity to meet Jinnah. How this was possible forms one of the many charming stories in the book.

Lal Singh and Man Singh found employment with a wealthy Parsi gentleman who owned one of the prominent jewellery stores in Bombay. Dubey told me that the Parsi gentleman lived in a building of his own, Firdaus, on Marine Drive. However, he hesitated in mentioning the name in the book since he, ninety-two years old, felt it was a risk to put into print any information which he could not verify. What was relevant to the story was that it was through them that Pandit Ram Narayan Azad got the opportunity to meet Jinnah. How this was possible forms one of the many charming stories in the book.

Lal Singh and Man Singh had arrived in Bombay and in course of time, one of them became the cook of the Parsi gentleman and the other his security guard. The gentleman was old and had no heir. He fell ill and came to the end of his days. The registrar was sent for, to ascertain his wishes regarding the disposition of his assets. When the registrar entered his bedroom, the gentleman stared at him intently, raised his arm and pointed at the ceiling. He then collapsed and was found to be dead.

The registrar sent the subordinates who had accompanied him to the higher floor. There, Lal Singh was in the kitchen. They called him down and informed him that his employee was no more – and that he had inherited his entire estate.

When Lal Singh and Man Singh next came to visit their village, they came as wealthy men. Over the years, they contributed considerably to the development of Mainpuri, starting a training school for trade skills as well as separate intermediate colleges for boys and girls. They also constructed a ten-mile road connecting their village, Bhawant, to Mainpuri town – something that the Government of India had neglected to do. These facts are known to Hari Govind Narayan Dubey. However, was it really Lal Singh and Man Singh who named their home Ganga Vihar?

One evening a few days ago, sitting on the warm parapet to enjoy the unique charms of Marine Drive, Mumbai, we noticed two buildings across the road: Firdaus and Ganga Vihar.

One evening a few days ago, sitting on the warm parapet to enjoy the unique charms of Marine Drive, Mumbai, we noticed two buildings across the road: Firdaus and Ganga Vihar. Why would anyone name a Marine Drive art deco building facing the Arabian Sea “Ganga Vihar”? As soon as the thought entered my mind, I realised with a pleasant jolt of surprise that I did know who must have done so. It had to have been Lal Singh and Man Singh, the Rajput brothers who had come to Bombay from Mainpuri District in the erstwhile United Provinces in 1910 or thereabouts, to earn their living.

I heard about Lal Singh and Man Singh from Hari Govind Narayan Dubey in the course of working with him to produce his book Forgotten Stories from my Village, Harwai .

The book tells the story of his father’s life and work in and around the Mainpuri District in the decades leading up to Independence. Dubey is a skilled storyteller and his book is more than just the life of Pandit Ram Narayan Azad. It is a tribute to the many brave men and women who sacrificed everything they had to their vision of an India where every citizen would lead a life of dignity and choice. Their stories have long faded away, and replaced by simplistic icons such as ‘Mahatma Gandhi’ and ‘Chacha Nehru’. They give charming personal views into life in an Indian village and involvement in various aspects of India’s freedom struggle.

Lal Singh and Man Singh found employment with a wealthy Parsi gentleman who owned one of the prominent jewellery stores in Bombay. Dubey told me that the Parsi gentleman lived in a building of his own, Firdaus, on Marine Drive. However, he hesitated in mentioning the name in the book since he, ninety-two years old, felt it was a risk to put into print any information which he could not verify. What was relevant to the story was that it was through them that Pandit Ram Narayan Azad got the opportunity to meet Jinnah. How this was possible forms one of the many charming stories in the book.

Lal Singh and Man Singh found employment with a wealthy Parsi gentleman who owned one of the prominent jewellery stores in Bombay. Dubey told me that the Parsi gentleman lived in a building of his own, Firdaus, on Marine Drive. However, he hesitated in mentioning the name in the book since he, ninety-two years old, felt it was a risk to put into print any information which he could not verify. What was relevant to the story was that it was through them that Pandit Ram Narayan Azad got the opportunity to meet Jinnah. How this was possible forms one of the many charming stories in the book. Lal Singh and Man Singh had arrived in Bombay and in course of time, one of them became the cook of the Parsi gentleman and the other his security guard. The gentleman was old and had no heir. He fell ill and came to the end of his days. The registrar was sent for, to ascertain his wishes regarding the disposition of his assets. When the registrar entered his bedroom, the gentleman stared at him intently, raised his arm and pointed at the ceiling. He then collapsed and was found to be dead.

The registrar sent the subordinates who had accompanied him to the higher floor. There, Lal Singh was in the kitchen. They called him down and informed him that his employee was no more – and that he had inherited his entire estate.

When Lal Singh and Man Singh next came to visit their village, they came as wealthy men. Over the years, they contributed considerably to the development of Mainpuri, starting a training school for trade skills as well as separate intermediate colleges for boys and girls. They also constructed a ten-mile road connecting their village, Bhawant, to Mainpuri town – something that the Government of India had neglected to do. These facts are known to Hari Govind Narayan Dubey. However, was it really Lal Singh and Man Singh who named their home Ganga Vihar?

Published on April 15, 2016 02:49

April 11, 2016

The Living by Anjali Joseph

Illuminating the beauty of all our lives One can usually tell that a book is bad in just a few pages but to tell that a book is good, you do have to read right through to the end. I held my breath as I read this one. Its first few pages held the kind of promise that an eager reader prays will last. I enjoyed the book very much, and enjoyed interviewing Anjali Joseph for Hindustan Times. In the course of the interview, which I’ve pasted below, I realised, with growing horror, that I was the longsuffering mother of the person with whom Ms Joseph was accosting young men outside a bakery in the evening, to find out more about ‘haathbhatti’. A coincidence, I promise, but in the interest of full disclosure and all.

Why footwear, why these particular cities?For me, the impetus to write a novel comes in two forms. The primary one is an image; the secondary is an idea or a question. For Saraswati Park I had an image of a man at a secondhand book stall in Flora Fountain in Mumbai, looking for books with marginal notations just before evening rush hour. And I knew I wanted to write about the daydreaming, book-reading, middle-class Bombay where I’d spent my early years and where my parents and grandparents had lived. For this book I had the image of a man making a pair of chappals. I’ve been wearing Kolhapuris since I was a child. The first pair I had was brought for me by my grandfather from a work trip to Kolhapur when I was three or four. I still wear Kolhapuris all the time, and find them both beautiful and practical, and I knew I wanted to write about the idea of daily work, of craft, and of some of the parts of life with which fiction deals less frequently: routine, habit, and ruptures in both. I also had an image of a woman in Norwich, originally in a place called Lion Wood, which appears in the novel. I realized she worked in a shoe factory, a profession that’s now anachronistic but which used to be one of the main trades in Norwich, where I was living when I started writing this novel.

Could you describe the reader you were writing for?I don’t really know, but I did want to write a book that plausibly might carry the voices of these two people – the kind of working class people who don’t consider themselves especially interesting and wouldn’t see their lives as the stuff of fiction. I am more interested in those lives than in the apparently exceptional or heroic, and I suppose my larger project is to illuminate the beauty of all of our lives, even (especially?) in their humdrum moments: everyday magic.

Then you’re not writing for a particular reader as some writers say they do?I don't think about anything other than the writing while I am writing. The reader-writer connection does matter to me – as a reader to begin with, and also as a writer. It's a small miraculous thing, the possibility of connecting with someone you may never meet. It's a real connection.

I enjoyed your poetic translation of Akashvani, any examples I may have missed because I didn’t have the context?I did use a few bits of Norwich speech, though Claire, the first narrator doesn’t talk in full Norfolk dialect, since she’s grown up in the city. ‘There was weather’, for example, means ‘The weather was bad’. I was also inspired by some of the things I’d seen when growing up in England in the mid and late 1980s: canned Alphabetti Spaghetti, for example, or corner shops. Those things are part of the furniture of the novel.

Did you find your characters changing as you wrote, or did they stay true to your early conception of them?Arun was initially more sarcastic, less tender, less nagging; Claire’s relationship with her son is something that became much warmer than I’d initially predicated. The process of writing a novel involves getting to know characters: their facades and what’s inside.

Any interesting stories about the research you did to get all this together?I spent a week in a shoe factory in Norwich, in January a few years ago. The people who worked there were generous with their time and attention and let me watch them work, and chat to them as they did; I found out the things I would rather not make up, like what it feels like when the bells go for breaks, or how the light falls at different times of day; how the shop floor, as it’s called, smells when the roughing machines come on in the morning. I also visited Kolhapur and nearby Miraj twice. Once I met chappal makers, thanks to the kindness of Vinayak Kadam of Adarsh Charmodyog Centre in Kolhapur. Most of the chappal makers work at home so I went around their houses with him and watched them work a little, and talked to them. The second time I visited, I wanted particularly to do two things. One was visit a country liquor bar in the area where the chappal makers live and work, because I knew Arun, the second narrator, had been an alcoholic for many years. The other was to find a small temple in a field that I’d dreamt of his visiting as a child. It was good that I went to Kolhapur because I realized that unlike Bombay it doesn’t have that many country liquor bars; government authorized country liquor is sold by certain people in certain areas, and then illegal, much cheaper and stronger ‘haathbhatti’ is sold as homebrew. A kind young man, a non-drinker himself, helped me find some haathbhatti when I accosted him outside a bakery one evening and asked where the country liquor bars were. He was worried my friend and I would get into trouble so he chivalrously escorted us to buy haathbhatti, then pleaded with me not to make a regular habit of drinking it. And the next day, while we were aimlessly driving around in the morning, we found the temple in the fields, basically as a gift.

I was going to say, ‘hmm why so much sexual activity!’ but also wanted to note my appreciation of your female interpretations of the sexual act.Sex is a big part of life, isn’t it? For Claire I think it represents a new opening out of her life after a long period of essentially mourning the teenage relationship that resulted in and ended with the birth of her son. For Arun I think it represents one of the few unregimented parts of his life. Everything else – work, marriage, eating, sleeping – is somehow inevitable. He loves his wife; he loves his family. But the randomness of unplanned extra-marital sex creates a rupture in that, and brings both a sense of freedom and sadness and guilt. I’m not sure what to say about a female experience of sex in general. I think for Claire there’s an experimental quality to the relationships she has. In her youth love was simple, but it ended. In her thirties, it’s not so simple for a while, but she also has a few transgresive encounters with a much younger man, her son’s friend, and there are no repercussions from that. That idea, which somehow seems normal for a male character, is something I found interesting. Part of the matter of factness of these characters and the lives they lead, in which time is parceled out in units that they make, is expressed in this experience that at times sex is just sex. At other times, of course, it brings emotions: wonder, surprise, grief.

Sexual acts in the public domain invariably describe men as experiencing mindless enjoyment whereas Claire does seem capable of thought during the process, could that be a feminine statement?I don't know. Now that you say it I seem to remember Molly Bloom doesn't stop chatting to herself during sex either. Perhaps it is a type of mind, not a gender-based difference?

Amit Chaudhuri gave The Living a rave review in The Guardian and a disgruntled reader wrote in to say that, as your former teacher and mentor, he must be biased?I was glad and grateful to read the review – it was written by one of my favourite writers. I hadn't asked for it to be written, or tried to influence what it said. Huffington Post wrote about the incident and asked for my response, but I didn't see why I should engage with accusations levied in anonymous emails. In any case, it’s for a reader to flip through the book and decide if it seems to speak to him, or her.

A few years ago, I wrote about Anjali Joseph’s debut novel Saraswati Park in this blog after reading it aloud to my friend Gladys, once a librarian but no longer able to read. We both admired its literary skill, and did not feel the need for more action than it has. This is relevant because critical reviews at the time complained that the reviewer had read on, waiting, but nothing exciting had happened and therefore concluded that this was not a good book. We wondered what these people would have had to say about Jane Austen if they were reading her for the first time, before all the hype, and congratulated ourselves smugly when Saraswati Park went on to win the Betty Trask Prize, the Desmond Eliot Prize – and in time the Vodafone Crossword Prize too. With The Living, Anjali Joseph has surpassed her skill of saying so very much with so very few words. I look forward to reading it to Gladys – and to hearing about the prizes that come its way!

Published on April 11, 2016 10:53

November 24, 2015

Mafia queens of Mumbai by S. Hussain Zaidi

Women leaders of a different kind

This book is a fascinating collection of true-life stories of women gangsters who lived and worked in Bombay. The author, S. Hussain Zaidi, was a crime reporter for decades and some of his books have been made into movies.

This book is a fascinating collection of true-life stories of women gangsters who lived and worked in Bombay. The author, S. Hussain Zaidi, was a crime reporter for decades and some of his books have been made into movies.

Not all the mafia queens in this book have blood on their hands. Jenabai, the elderly Muslim woman who somehow acquired the same name as a thirteenth century (Hindu) Marathi poet, made her biggest and most damaging impact because she was able to influence another powerful gangster with her strategic thinking. Then there was Gangubai, who was lured into prostitution by a young man with whom she eloped and who, instead of marrying her, sold her to a brothel. Gangubai rebelled by first developing a reputation for the highest skills of her trade, and later by rescuing other women from the trap she had fallen into, if she felt they were not cut out for life in the cages of Falkland Road. She became a public figure, and campaigned for the need for a prostitution belt in all cities. Some of these female gangsters were drawn to their profession by dire economic circumstances and some enticed into it by exploitative males. Some are symbols of glamour; some admirable for their courage and nimble thinking.I was lent this book to read by a friend who is a police officer more than a year ago. That turned into a year in which I did not read many books at all. Eventually, I read it aloud to Gladys. It turned out to be a quick read and, though a teeny bit raunchy at times, we both enjoyed it. One problem with reading a book aloud, though, is that the proofing and editing flaws stand out. I may not have noticed the many colloquial expressions and common clichés of Indian newspaper crime-reporting that this book is strewn with if I had just been reading it to myself. Another thing I wondered about was the extent of detail in the book: was it fictionalised or was every setting recreated from what was told to the author in an interview? I tried to contact S. Hussani Zaidi to find out, but was unable to.

This book is a fascinating collection of true-life stories of women gangsters who lived and worked in Bombay. The author, S. Hussain Zaidi, was a crime reporter for decades and some of his books have been made into movies.

This book is a fascinating collection of true-life stories of women gangsters who lived and worked in Bombay. The author, S. Hussain Zaidi, was a crime reporter for decades and some of his books have been made into movies.Not all the mafia queens in this book have blood on their hands. Jenabai, the elderly Muslim woman who somehow acquired the same name as a thirteenth century (Hindu) Marathi poet, made her biggest and most damaging impact because she was able to influence another powerful gangster with her strategic thinking. Then there was Gangubai, who was lured into prostitution by a young man with whom she eloped and who, instead of marrying her, sold her to a brothel. Gangubai rebelled by first developing a reputation for the highest skills of her trade, and later by rescuing other women from the trap she had fallen into, if she felt they were not cut out for life in the cages of Falkland Road. She became a public figure, and campaigned for the need for a prostitution belt in all cities. Some of these female gangsters were drawn to their profession by dire economic circumstances and some enticed into it by exploitative males. Some are symbols of glamour; some admirable for their courage and nimble thinking.I was lent this book to read by a friend who is a police officer more than a year ago. That turned into a year in which I did not read many books at all. Eventually, I read it aloud to Gladys. It turned out to be a quick read and, though a teeny bit raunchy at times, we both enjoyed it. One problem with reading a book aloud, though, is that the proofing and editing flaws stand out. I may not have noticed the many colloquial expressions and common clichés of Indian newspaper crime-reporting that this book is strewn with if I had just been reading it to myself. Another thing I wondered about was the extent of detail in the book: was it fictionalised or was every setting recreated from what was told to the author in an interview? I tried to contact S. Hussani Zaidi to find out, but was unable to.

Published on November 24, 2015 23:20

October 11, 2015

Kharemaster by Vibhavari Shirurkar

A daughter’s view

I’m lucky to have history professors for friends, and one of them sent me this book as an example of what a biography could be. When I started reading, I was compelled by the simple, emotional narrative of an elderly woman writing her memories of her father’s life, an excellent translation from Marathi. By the end of the book, however, I realised that it was the content and the way it was presented that had most impressed me.Kharemaster was an unusual person for his time because he made sure that all his children got educated. At a time when Hindu girls were ‘married off’ at the age of eight or even younger; a time when for even a boy to complete high school and be ‘matriculate’ was the privilege of very few, he was determined that his daughters would get a university education. When they were little, he worked with them himself, developing their awareness and giving them knowledge about the world. As they grew older, he went to great extents to find ways for them to get the best possible education. Still, the book is not a hagiography. Kharemaster’s faults and weaknesses, and in one case a rather shocking incident, are presented with the same warmth and confidence as every other aspect the book covers. Vibhavari Shirurkar was in her eighties when she wrote this book. All her life, she had written books about the women around her, and these naturally revealed the ways in which they were exploited and dehumanised by the norms of society. The books were admired but they were very controversial. Right from the first one, they were written under a pseudonym. Though she did reveal herself early on, perhaps retaining the pseudonym as her brand, this book goes further. It is not just the biography of Kharemaster but also a complete exposition of the identity of the well-known Marathi litterateur Vibhavari Shirurkar: Balutai, one of the daughters of Kharemaster, and the circumstances in which she grew up and became the person she became.The story starts with Kharemaster’s own writing, notes from his diary given to Balutai by her mother after her father dies. Then, influenced by an old friend of her father, Balutai takes a decision to write the book by projecting her imagination into the events she remembers and trying to interpret them in her own way. This is a device that works very well, except (to my mind) in one place. Towards the end of his life, Balutai depicts her father as lonely and depressed, preoccupied with feelings of rejection. I did feel that this particular projection might have resulted from feelings of guilt and regret this sensitive woman felt for her parents and their needs, and the conflicting pressures of her own life which prevented her from giving them the attention and care they may have craved. Maybe Kharemaster wasn't all that lonely and depressed after all, maybe he spent his last years in the glow of silent achievement, knowing that all his children were well-off and well settled because he had made sure they got well educated.One of the things I enjoyed most about this book is the skilled depiction of life in those days, and I learnt a lot: a deeper understanding of the way women were perceived and their own perceptions of themselves; the relevance of caste in society; the human angle of religious conversion, and much more. It was interesting to know that, during the First World War, young Indian men were kidnapped and sent by force to join the British army. It was also interesting to see how the emergence of women as individuals made marriage more difficult because it took an unusual man to accept that perception. Modern and educated young Indian men and women today are rejecting marriage, refusing to enter into a contract that forces them into traditional roles that they cannot and will not fulfil. It was a movement that began with the dedicated actions and sacrifices made by rare people like Kharemaster.

I’m lucky to have history professors for friends, and one of them sent me this book as an example of what a biography could be. When I started reading, I was compelled by the simple, emotional narrative of an elderly woman writing her memories of her father’s life, an excellent translation from Marathi. By the end of the book, however, I realised that it was the content and the way it was presented that had most impressed me.Kharemaster was an unusual person for his time because he made sure that all his children got educated. At a time when Hindu girls were ‘married off’ at the age of eight or even younger; a time when for even a boy to complete high school and be ‘matriculate’ was the privilege of very few, he was determined that his daughters would get a university education. When they were little, he worked with them himself, developing their awareness and giving them knowledge about the world. As they grew older, he went to great extents to find ways for them to get the best possible education. Still, the book is not a hagiography. Kharemaster’s faults and weaknesses, and in one case a rather shocking incident, are presented with the same warmth and confidence as every other aspect the book covers. Vibhavari Shirurkar was in her eighties when she wrote this book. All her life, she had written books about the women around her, and these naturally revealed the ways in which they were exploited and dehumanised by the norms of society. The books were admired but they were very controversial. Right from the first one, they were written under a pseudonym. Though she did reveal herself early on, perhaps retaining the pseudonym as her brand, this book goes further. It is not just the biography of Kharemaster but also a complete exposition of the identity of the well-known Marathi litterateur Vibhavari Shirurkar: Balutai, one of the daughters of Kharemaster, and the circumstances in which she grew up and became the person she became.The story starts with Kharemaster’s own writing, notes from his diary given to Balutai by her mother after her father dies. Then, influenced by an old friend of her father, Balutai takes a decision to write the book by projecting her imagination into the events she remembers and trying to interpret them in her own way. This is a device that works very well, except (to my mind) in one place. Towards the end of his life, Balutai depicts her father as lonely and depressed, preoccupied with feelings of rejection. I did feel that this particular projection might have resulted from feelings of guilt and regret this sensitive woman felt for her parents and their needs, and the conflicting pressures of her own life which prevented her from giving them the attention and care they may have craved. Maybe Kharemaster wasn't all that lonely and depressed after all, maybe he spent his last years in the glow of silent achievement, knowing that all his children were well-off and well settled because he had made sure they got well educated.One of the things I enjoyed most about this book is the skilled depiction of life in those days, and I learnt a lot: a deeper understanding of the way women were perceived and their own perceptions of themselves; the relevance of caste in society; the human angle of religious conversion, and much more. It was interesting to know that, during the First World War, young Indian men were kidnapped and sent by force to join the British army. It was also interesting to see how the emergence of women as individuals made marriage more difficult because it took an unusual man to accept that perception. Modern and educated young Indian men and women today are rejecting marriage, refusing to enter into a contract that forces them into traditional roles that they cannot and will not fulfil. It was a movement that began with the dedicated actions and sacrifices made by rare people like Kharemaster.

I’m lucky to have history professors for friends, and one of them sent me this book as an example of what a biography could be. When I started reading, I was compelled by the simple, emotional narrative of an elderly woman writing her memories of her father’s life, an excellent translation from Marathi. By the end of the book, however, I realised that it was the content and the way it was presented that had most impressed me.Kharemaster was an unusual person for his time because he made sure that all his children got educated. At a time when Hindu girls were ‘married off’ at the age of eight or even younger; a time when for even a boy to complete high school and be ‘matriculate’ was the privilege of very few, he was determined that his daughters would get a university education. When they were little, he worked with them himself, developing their awareness and giving them knowledge about the world. As they grew older, he went to great extents to find ways for them to get the best possible education. Still, the book is not a hagiography. Kharemaster’s faults and weaknesses, and in one case a rather shocking incident, are presented with the same warmth and confidence as every other aspect the book covers. Vibhavari Shirurkar was in her eighties when she wrote this book. All her life, she had written books about the women around her, and these naturally revealed the ways in which they were exploited and dehumanised by the norms of society. The books were admired but they were very controversial. Right from the first one, they were written under a pseudonym. Though she did reveal herself early on, perhaps retaining the pseudonym as her brand, this book goes further. It is not just the biography of Kharemaster but also a complete exposition of the identity of the well-known Marathi litterateur Vibhavari Shirurkar: Balutai, one of the daughters of Kharemaster, and the circumstances in which she grew up and became the person she became.The story starts with Kharemaster’s own writing, notes from his diary given to Balutai by her mother after her father dies. Then, influenced by an old friend of her father, Balutai takes a decision to write the book by projecting her imagination into the events she remembers and trying to interpret them in her own way. This is a device that works very well, except (to my mind) in one place. Towards the end of his life, Balutai depicts her father as lonely and depressed, preoccupied with feelings of rejection. I did feel that this particular projection might have resulted from feelings of guilt and regret this sensitive woman felt for her parents and their needs, and the conflicting pressures of her own life which prevented her from giving them the attention and care they may have craved. Maybe Kharemaster wasn't all that lonely and depressed after all, maybe he spent his last years in the glow of silent achievement, knowing that all his children were well-off and well settled because he had made sure they got well educated.One of the things I enjoyed most about this book is the skilled depiction of life in those days, and I learnt a lot: a deeper understanding of the way women were perceived and their own perceptions of themselves; the relevance of caste in society; the human angle of religious conversion, and much more. It was interesting to know that, during the First World War, young Indian men were kidnapped and sent by force to join the British army. It was also interesting to see how the emergence of women as individuals made marriage more difficult because it took an unusual man to accept that perception. Modern and educated young Indian men and women today are rejecting marriage, refusing to enter into a contract that forces them into traditional roles that they cannot and will not fulfil. It was a movement that began with the dedicated actions and sacrifices made by rare people like Kharemaster.

I’m lucky to have history professors for friends, and one of them sent me this book as an example of what a biography could be. When I started reading, I was compelled by the simple, emotional narrative of an elderly woman writing her memories of her father’s life, an excellent translation from Marathi. By the end of the book, however, I realised that it was the content and the way it was presented that had most impressed me.Kharemaster was an unusual person for his time because he made sure that all his children got educated. At a time when Hindu girls were ‘married off’ at the age of eight or even younger; a time when for even a boy to complete high school and be ‘matriculate’ was the privilege of very few, he was determined that his daughters would get a university education. When they were little, he worked with them himself, developing their awareness and giving them knowledge about the world. As they grew older, he went to great extents to find ways for them to get the best possible education. Still, the book is not a hagiography. Kharemaster’s faults and weaknesses, and in one case a rather shocking incident, are presented with the same warmth and confidence as every other aspect the book covers. Vibhavari Shirurkar was in her eighties when she wrote this book. All her life, she had written books about the women around her, and these naturally revealed the ways in which they were exploited and dehumanised by the norms of society. The books were admired but they were very controversial. Right from the first one, they were written under a pseudonym. Though she did reveal herself early on, perhaps retaining the pseudonym as her brand, this book goes further. It is not just the biography of Kharemaster but also a complete exposition of the identity of the well-known Marathi litterateur Vibhavari Shirurkar: Balutai, one of the daughters of Kharemaster, and the circumstances in which she grew up and became the person she became.The story starts with Kharemaster’s own writing, notes from his diary given to Balutai by her mother after her father dies. Then, influenced by an old friend of her father, Balutai takes a decision to write the book by projecting her imagination into the events she remembers and trying to interpret them in her own way. This is a device that works very well, except (to my mind) in one place. Towards the end of his life, Balutai depicts her father as lonely and depressed, preoccupied with feelings of rejection. I did feel that this particular projection might have resulted from feelings of guilt and regret this sensitive woman felt for her parents and their needs, and the conflicting pressures of her own life which prevented her from giving them the attention and care they may have craved. Maybe Kharemaster wasn't all that lonely and depressed after all, maybe he spent his last years in the glow of silent achievement, knowing that all his children were well-off and well settled because he had made sure they got well educated.One of the things I enjoyed most about this book is the skilled depiction of life in those days, and I learnt a lot: a deeper understanding of the way women were perceived and their own perceptions of themselves; the relevance of caste in society; the human angle of religious conversion, and much more. It was interesting to know that, during the First World War, young Indian men were kidnapped and sent by force to join the British army. It was also interesting to see how the emergence of women as individuals made marriage more difficult because it took an unusual man to accept that perception. Modern and educated young Indian men and women today are rejecting marriage, refusing to enter into a contract that forces them into traditional roles that they cannot and will not fulfil. It was a movement that began with the dedicated actions and sacrifices made by rare people like Kharemaster.

Published on October 11, 2015 05:49

May 17, 2015

Hadal by CP Surendran

Underwater exploration

As a piece of contemporary literature, there are many aspects to Hadal. First and most basic, it may be admired for its unwavering plot and its lifelike characters, presented in a manner which keeps the reader engaged. As such, it could easily find its feet in a burgeoning marketplace of newcomer readers whose tastes may be ready to move on from Ravinder Singh and Chetan Bhagat.

As a piece of contemporary literature, there are many aspects to Hadal. First and most basic, it may be admired for its unwavering plot and its lifelike characters, presented in a manner which keeps the reader engaged. As such, it could easily find its feet in a burgeoning marketplace of newcomer readers whose tastes may be ready to move on from Ravinder Singh and Chetan Bhagat.

Second, as its author, CP Surendran, acknowledges, the book is not pleasingly exotic or prettily clever and correct. It is inspired by a true story: the story of an Indian rocket scientist falsely accused of selling secrets of the Indian space research programme. Also, one of its main characters is a confused, wishy-washy, inappropriate role-model, victim of a woman. For a publishing industry grappling with self-esteem issues since historic times (and one whose decision-makers today are mostly women), it marks a kind of coming-of-age to have let through an important book without a ‘wow!’ theme and with such a character.

Another aspect of Hadal is a fabric of fundamental common-sense backed by a weft of satire. Located in Kerala, it has coconuts, street and pet dogs and a wannabe tourist industry. There is an evil nuclear power plant with a foreign do-gooding activist, who tries but is unable to convince young people that basket-weaving and the idyllic village life is the way forward. Another of Hadal’s main characters is a rocket scientist – what could be sexier than someone who understands everything – and he turns out to be someone with a deep, fundamental instinct for what women want. Ironically, he will only learn, too late, that there are things fathers should never do so that their sons could be happy.

This book shows us that dreams are real – why else does your heart continue to pound at the mere hologram of a few mis-matched memories? Shadowy women characters determinedly express their individuality. Villainous men (men addicted to cough syrup) come undone by their deep love for and dependence on their mothers. A teenager feels complete, and with his well-lived life behind him, is all set to welcome death. An elephant recognizes his mistress eight years after she, having fallen on lean days, had sold him to a temple. While having a gentle dig at the self-righteous mental health professionals of a certain Nordic country where Indian parenting has been considered lacking, Hadal exposes how we, as a people, have yet to come to terms with adoption.

This vigorous and colourful context comes to the reader in short, powerful sentences that conjure up striking portraits and landscapes. Then, all of a sudden, unexpectedly, the territory transforms. Abyss, whirlpool, torrent … dramatic, self-indulgent, exquisitely beautiful … a dancing panorama of sentences unfolds. It turns out that the author of this novel is a poet. He is not just a poet, but an activist too. It turns out that the innermost thrust of this book is not just self-expression. The innermost thrust of this book is to hold Indian democracy – not just Indian democracy but Indian civilization itself – under a spotlight.

What is the fundamental problem we face as a people? With sixty percent of us defecating in the open, could it be, maybe, toilets? Or is it just that old thing we always knew, that the people in charge are irresponsible and crazed, career fascists? Is it that we ourselves are nothing but liars and cheats? Is it just our helplessness against our biology, and sometimes our geography, that makes us all so laughably weak and ridiculous? Are we as different from Pakistan and Nigeria as we would like to believe?

Every writer, as CP Surendran observes in this book, is at the mercy of others’ tastes, beholden to how a million others were brought up, the books they read, the schools they went to, the kind of parents they had. How many in that burgeoning marketplace of newcomer readers, browsing bookshelves or surfing top-ten lists, would connect Hadal with the Greek word Hades, the abode of the dead? How many would know, without consulting google, that Hadal also refers to the deepest trenches under the sea? In these trenches, pressure and density and opacity are extreme. Reading this book, it appears that CP Surendran chose this title with the intention of conveying that, though we tend to delude ourselves that we are a great, open people, maybe we are actually hadal.

first appeared in Outlook magazine issue of 18 May 2015

As a piece of contemporary literature, there are many aspects to Hadal. First and most basic, it may be admired for its unwavering plot and its lifelike characters, presented in a manner which keeps the reader engaged. As such, it could easily find its feet in a burgeoning marketplace of newcomer readers whose tastes may be ready to move on from Ravinder Singh and Chetan Bhagat.

As a piece of contemporary literature, there are many aspects to Hadal. First and most basic, it may be admired for its unwavering plot and its lifelike characters, presented in a manner which keeps the reader engaged. As such, it could easily find its feet in a burgeoning marketplace of newcomer readers whose tastes may be ready to move on from Ravinder Singh and Chetan Bhagat.Second, as its author, CP Surendran, acknowledges, the book is not pleasingly exotic or prettily clever and correct. It is inspired by a true story: the story of an Indian rocket scientist falsely accused of selling secrets of the Indian space research programme. Also, one of its main characters is a confused, wishy-washy, inappropriate role-model, victim of a woman. For a publishing industry grappling with self-esteem issues since historic times (and one whose decision-makers today are mostly women), it marks a kind of coming-of-age to have let through an important book without a ‘wow!’ theme and with such a character.

Another aspect of Hadal is a fabric of fundamental common-sense backed by a weft of satire. Located in Kerala, it has coconuts, street and pet dogs and a wannabe tourist industry. There is an evil nuclear power plant with a foreign do-gooding activist, who tries but is unable to convince young people that basket-weaving and the idyllic village life is the way forward. Another of Hadal’s main characters is a rocket scientist – what could be sexier than someone who understands everything – and he turns out to be someone with a deep, fundamental instinct for what women want. Ironically, he will only learn, too late, that there are things fathers should never do so that their sons could be happy.

This book shows us that dreams are real – why else does your heart continue to pound at the mere hologram of a few mis-matched memories? Shadowy women characters determinedly express their individuality. Villainous men (men addicted to cough syrup) come undone by their deep love for and dependence on their mothers. A teenager feels complete, and with his well-lived life behind him, is all set to welcome death. An elephant recognizes his mistress eight years after she, having fallen on lean days, had sold him to a temple. While having a gentle dig at the self-righteous mental health professionals of a certain Nordic country where Indian parenting has been considered lacking, Hadal exposes how we, as a people, have yet to come to terms with adoption.

This vigorous and colourful context comes to the reader in short, powerful sentences that conjure up striking portraits and landscapes. Then, all of a sudden, unexpectedly, the territory transforms. Abyss, whirlpool, torrent … dramatic, self-indulgent, exquisitely beautiful … a dancing panorama of sentences unfolds. It turns out that the author of this novel is a poet. He is not just a poet, but an activist too. It turns out that the innermost thrust of this book is not just self-expression. The innermost thrust of this book is to hold Indian democracy – not just Indian democracy but Indian civilization itself – under a spotlight.

What is the fundamental problem we face as a people? With sixty percent of us defecating in the open, could it be, maybe, toilets? Or is it just that old thing we always knew, that the people in charge are irresponsible and crazed, career fascists? Is it that we ourselves are nothing but liars and cheats? Is it just our helplessness against our biology, and sometimes our geography, that makes us all so laughably weak and ridiculous? Are we as different from Pakistan and Nigeria as we would like to believe?

Every writer, as CP Surendran observes in this book, is at the mercy of others’ tastes, beholden to how a million others were brought up, the books they read, the schools they went to, the kind of parents they had. How many in that burgeoning marketplace of newcomer readers, browsing bookshelves or surfing top-ten lists, would connect Hadal with the Greek word Hades, the abode of the dead? How many would know, without consulting google, that Hadal also refers to the deepest trenches under the sea? In these trenches, pressure and density and opacity are extreme. Reading this book, it appears that CP Surendran chose this title with the intention of conveying that, though we tend to delude ourselves that we are a great, open people, maybe we are actually hadal.

first appeared in Outlook magazine issue of 18 May 2015

Published on May 17, 2015 23:25

December 6, 2014

Atisa and his time machine (Adventures with Hieun Tsang) by Anu Kumar

History as fun-filled adventure

I read about this book on facebook and immediately ordered a copy. I very much liked the idea of encountering Hieun Tsang as a real person, even if only an imaginary version. Reading and revelling in the author’s imagery and racy plot, marvelling at Priya Kurian’s very stylish illustrations, wishing I’d had books like this to read as a child, I realised that this was one of a series and it did not tell me how old Atisa was, how and when his time machine was created and a few other things I wanted to know. I sent Anu Kumar a set of questions. I have left her replies just as she wrote them, so that anyone who reads this will get a sense of her writing style. Meanwhile, as I eagerly await the next Atisa book, I've been reading the previous ones and bought copies for younger readers too.

I read about this book on facebook and immediately ordered a copy. I very much liked the idea of encountering Hieun Tsang as a real person, even if only an imaginary version. Reading and revelling in the author’s imagery and racy plot, marvelling at Priya Kurian’s very stylish illustrations, wishing I’d had books like this to read as a child, I realised that this was one of a series and it did not tell me how old Atisa was, how and when his time machine was created and a few other things I wanted to know. I sent Anu Kumar a set of questions. I have left her replies just as she wrote them, so that anyone who reads this will get a sense of her writing style. Meanwhile, as I eagerly await the next Atisa book, I've been reading the previous ones and bought copies for younger readers too.