Saaz Aggarwal's Blog, page 3

June 26, 2019

The Revenge of the Non-vegetarian by Upamanyu Chatterjee

Absurd comedy and grand horrors

I wanted something light and fulfilling to read on a journey, and picked The Revenge of the Non-vegetarian by Upamanyu Chatterjee from a teetering pile (a very patient teetering pile) on my bedside. It turned out to be the perfect choice because I thoroughly enjoyed every one of its well-chosen words. At the end, the jacket blurb included this sentence in the author description: “He spent over thirty calm and undistinguished years in the Indian Administrative Service; during that time, he wrote six novels – when no one was looking.” That was inspiring – I got online looking for the other five. I remembered reading English, August when it was new and enjoying it thoroughly as a work of literature but being revolted by quite a bit of the story.The description of The Assassination of Indira Gandhi said that “In the twelve long stories that comprise this volume, he investigates, as only he can, the absurd comedy and the grand horrors of the human condition.” ‘Absurd comedy’ and ‘grand horrors’ are indeed the fabric of what I’ve read of Upamanyu Chatterjee. Perhaps not entirely of the human condition, but certainly of a westernized IAS officer reigning supreme in rural India.The Revenge of the Non-vegetarian is one of those books that evokes vivid images and transports the reader deep into its plot using tightly-packed and crisp prose. At one level it’s a grotesque story of vicious murder followed by a ludicrous implementation of justice. At another, it holds a mirror up to us as a people who exploit those weaker than ourselves, make the wretched even more wretched, and then accuse and incarcerate them of wretchedness. It is a brilliant parody of the truth that comprises India and its administration.

I wanted something light and fulfilling to read on a journey, and picked The Revenge of the Non-vegetarian by Upamanyu Chatterjee from a teetering pile (a very patient teetering pile) on my bedside. It turned out to be the perfect choice because I thoroughly enjoyed every one of its well-chosen words. At the end, the jacket blurb included this sentence in the author description: “He spent over thirty calm and undistinguished years in the Indian Administrative Service; during that time, he wrote six novels – when no one was looking.” That was inspiring – I got online looking for the other five. I remembered reading English, August when it was new and enjoying it thoroughly as a work of literature but being revolted by quite a bit of the story.The description of The Assassination of Indira Gandhi said that “In the twelve long stories that comprise this volume, he investigates, as only he can, the absurd comedy and the grand horrors of the human condition.” ‘Absurd comedy’ and ‘grand horrors’ are indeed the fabric of what I’ve read of Upamanyu Chatterjee. Perhaps not entirely of the human condition, but certainly of a westernized IAS officer reigning supreme in rural India.The Revenge of the Non-vegetarian is one of those books that evokes vivid images and transports the reader deep into its plot using tightly-packed and crisp prose. At one level it’s a grotesque story of vicious murder followed by a ludicrous implementation of justice. At another, it holds a mirror up to us as a people who exploit those weaker than ourselves, make the wretched even more wretched, and then accuse and incarcerate them of wretchedness. It is a brilliant parody of the truth that comprises India and its administration.

I wanted something light and fulfilling to read on a journey, and picked The Revenge of the Non-vegetarian by Upamanyu Chatterjee from a teetering pile (a very patient teetering pile) on my bedside. It turned out to be the perfect choice because I thoroughly enjoyed every one of its well-chosen words. At the end, the jacket blurb included this sentence in the author description: “He spent over thirty calm and undistinguished years in the Indian Administrative Service; during that time, he wrote six novels – when no one was looking.” That was inspiring – I got online looking for the other five. I remembered reading English, August when it was new and enjoying it thoroughly as a work of literature but being revolted by quite a bit of the story.The description of The Assassination of Indira Gandhi said that “In the twelve long stories that comprise this volume, he investigates, as only he can, the absurd comedy and the grand horrors of the human condition.” ‘Absurd comedy’ and ‘grand horrors’ are indeed the fabric of what I’ve read of Upamanyu Chatterjee. Perhaps not entirely of the human condition, but certainly of a westernized IAS officer reigning supreme in rural India.The Revenge of the Non-vegetarian is one of those books that evokes vivid images and transports the reader deep into its plot using tightly-packed and crisp prose. At one level it’s a grotesque story of vicious murder followed by a ludicrous implementation of justice. At another, it holds a mirror up to us as a people who exploit those weaker than ourselves, make the wretched even more wretched, and then accuse and incarcerate them of wretchedness. It is a brilliant parody of the truth that comprises India and its administration.

I wanted something light and fulfilling to read on a journey, and picked The Revenge of the Non-vegetarian by Upamanyu Chatterjee from a teetering pile (a very patient teetering pile) on my bedside. It turned out to be the perfect choice because I thoroughly enjoyed every one of its well-chosen words. At the end, the jacket blurb included this sentence in the author description: “He spent over thirty calm and undistinguished years in the Indian Administrative Service; during that time, he wrote six novels – when no one was looking.” That was inspiring – I got online looking for the other five. I remembered reading English, August when it was new and enjoying it thoroughly as a work of literature but being revolted by quite a bit of the story.The description of The Assassination of Indira Gandhi said that “In the twelve long stories that comprise this volume, he investigates, as only he can, the absurd comedy and the grand horrors of the human condition.” ‘Absurd comedy’ and ‘grand horrors’ are indeed the fabric of what I’ve read of Upamanyu Chatterjee. Perhaps not entirely of the human condition, but certainly of a westernized IAS officer reigning supreme in rural India.The Revenge of the Non-vegetarian is one of those books that evokes vivid images and transports the reader deep into its plot using tightly-packed and crisp prose. At one level it’s a grotesque story of vicious murder followed by a ludicrous implementation of justice. At another, it holds a mirror up to us as a people who exploit those weaker than ourselves, make the wretched even more wretched, and then accuse and incarcerate them of wretchedness. It is a brilliant parody of the truth that comprises India and its administration.

Published on June 26, 2019 00:15

March 29, 2019

Shillong Times by Nilanjan P Choudhury

Violence in paradise

I read this book because my daughter recommended it. It meant I was assured of a really good read; what I did not expect was that it would be so strewn with unhappiness. After all, the central character, Debu, is just 14.Like most people who lead insular lives preoccupied with their own minutiae, I was unaware of the civil unrest in Shillong at around the same time that I was growing up in the peaceful Nilgiri Hills. When I read Murli Melwani’s book Ladders Against the Sky and interviewed him, he told me that his family had left Shillong at this time and on account of the strife. I did not ask for details, and barely sensed the pain of disruption his and so many other families experienced. Reading this book brought the situation starkly alive. I wasn't surprised to see Murli's name in the author's acknowledgements, and when I emailed this to Murli he replied saying that he had suggested people for Nilanjan P Choudhury to interview. Murli wrote a review too and you can read it on

this link

. He told me that the title of his review is a line from one of Bob Dylan's songs and that Dylan is very popular with the Khasis of Shillong. While this book skillfully presents social problems and human suffering caused by human greed and political vested interests through an interesting story, it is more than just a device to do so. One of the things I enjoyed most was the way it gripped me. It took me back to my younger self, bringing alive that old familiar feeling of resenting anything that came between me and what I was reading. Beyond the story, there are also passages of commentary which give context, sometimes in a thoroughly amusing way. And the excursion to Mawphlang had me admiring the poignant symbolism of violence erupting in paradise, as well as hoping that I would one day be able to visit the ancient sacred grove.

I read this book because my daughter recommended it. It meant I was assured of a really good read; what I did not expect was that it would be so strewn with unhappiness. After all, the central character, Debu, is just 14.Like most people who lead insular lives preoccupied with their own minutiae, I was unaware of the civil unrest in Shillong at around the same time that I was growing up in the peaceful Nilgiri Hills. When I read Murli Melwani’s book Ladders Against the Sky and interviewed him, he told me that his family had left Shillong at this time and on account of the strife. I did not ask for details, and barely sensed the pain of disruption his and so many other families experienced. Reading this book brought the situation starkly alive. I wasn't surprised to see Murli's name in the author's acknowledgements, and when I emailed this to Murli he replied saying that he had suggested people for Nilanjan P Choudhury to interview. Murli wrote a review too and you can read it on

this link

. He told me that the title of his review is a line from one of Bob Dylan's songs and that Dylan is very popular with the Khasis of Shillong. While this book skillfully presents social problems and human suffering caused by human greed and political vested interests through an interesting story, it is more than just a device to do so. One of the things I enjoyed most was the way it gripped me. It took me back to my younger self, bringing alive that old familiar feeling of resenting anything that came between me and what I was reading. Beyond the story, there are also passages of commentary which give context, sometimes in a thoroughly amusing way. And the excursion to Mawphlang had me admiring the poignant symbolism of violence erupting in paradise, as well as hoping that I would one day be able to visit the ancient sacred grove.

Published on March 29, 2019 01:24

March 24, 2019

The Women's Courtyard by Khadija Mastur

Zooming in on a microcosm

If a women’s courtyard is considered an enclosed inner space, this book is a canvas with streaks and splashes of unexpectedly vibrant colour and design. The women that inhabit the courtyard are strong and lifelike, and the qualities that each one epitomizes is perceived through her actions and speech. So while we never learn the given names of Amma (also known as ‘Mazhar’s Bride’) and Aunty, we experience them very clearly as real people. This is a historical period and a segment of society where poets sing on the streets – but also where arrogance is native to wealth and privilege. Amma has been betrayed by her circumstances, and her constant taunts, bitter appraisals, never-ending self-pity and glorification are received with tolerance and even empathy simply because life has been cruel to someone who expected better. Her sister-in-law Najma, an MA in English and a working woman who in the 1940s arranges her own marriage (and later walks out of it), is vain and consistently demeaning of those she considers beneath her because they have not studied English. She flaunts elitist opinions such as, “Only people who are incapable of getting a job know Arabic and Farsi”. Najma’s sister-in-law, Aunty, on the other hand, is that loving and giving woman – one whose eyes can be seen ‘filled with centuries of grief’ – on whom every large household relies. Even when immersed in disappointment, loss and financial struggle, she labours on, almost always emanating warmth and kindness. Young Chammi – acknowledged as Shamima but once by the author – has the status of one whose mother died and whose father left to live elsewhere, his new life overrun by new wives and their offspring. Beautiful, unwanted Chammi, treated with love by Aunty, somehow became that wild, shrewish girl whose tantrums are feared to such an extent that when her marriage is arranged, no one dares to inform her. Kareeman Bua, who came with her mother in the mistress’s dowry, lives a life of domestic servitude, devoted to the family, oblivious to scars formed by disproportionate rage on her body.This book is not just about women and their cloistered existence; it also shows how global events infiltrate the courtyard and shape their lives. It is set in a period of Indian history of which authentic details have been so obscured by political propaganda and regressive patriotism, that what remains in textbooks and the general mindset is a trite caricature of what once truly was. Khadija Mastur was known for her own underprivileged background and her political views, and the lives and conversations in this book open a window on the actual terrain of the era. Here is a Muslim household, steeped in tradition and piety, and the nationalist reality portrayed is complex. There is an overwhelming love for country, which leads to sacrifice of family life and personal comfort, imprisonment, suffering and death. There is also an irreparable rift between members of the family, some of whom follow the Muslim League while others consider them traitors, believing that party to be an instrument of further divisiveness and a fundamental cause of inciting violence and continuing strife. The most enchanting voice in the book is of Aliya, the heroine, who shares her reality with the reader. Sensitive and thoughtful, Aliya feels the pain of the women – but just as much of the men and their inability to bring happiness to their families. The stories on which Aliya thrives mirror through romantic legend the lives of their characters, fueling their wellsprings of emotion and, more than once, resulting in ghastly tragedy. (Women would commit suicide for love and depart as examples of perfect fidelity, and then, some dark night, men would appear to momentarily light a lamp over the tomb, then leave, and that was that). Intertwined with the tradition of stories originating in Arabia runs a strong and persistent strain with the stories and symbols of Krishna and Rama making numerous appearances.And the most beautiful scenes are as the book ends, in the newly-created Pakistan. The clamour and strife subside and wonderful fictional coincidences transpire, one bringing a tragic finality and another opening out onto a horizon of love and hope.This review was written for

Hindustan Times

and appeared on Saturday 23 March 2018.

If a women’s courtyard is considered an enclosed inner space, this book is a canvas with streaks and splashes of unexpectedly vibrant colour and design. The women that inhabit the courtyard are strong and lifelike, and the qualities that each one epitomizes is perceived through her actions and speech. So while we never learn the given names of Amma (also known as ‘Mazhar’s Bride’) and Aunty, we experience them very clearly as real people. This is a historical period and a segment of society where poets sing on the streets – but also where arrogance is native to wealth and privilege. Amma has been betrayed by her circumstances, and her constant taunts, bitter appraisals, never-ending self-pity and glorification are received with tolerance and even empathy simply because life has been cruel to someone who expected better. Her sister-in-law Najma, an MA in English and a working woman who in the 1940s arranges her own marriage (and later walks out of it), is vain and consistently demeaning of those she considers beneath her because they have not studied English. She flaunts elitist opinions such as, “Only people who are incapable of getting a job know Arabic and Farsi”. Najma’s sister-in-law, Aunty, on the other hand, is that loving and giving woman – one whose eyes can be seen ‘filled with centuries of grief’ – on whom every large household relies. Even when immersed in disappointment, loss and financial struggle, she labours on, almost always emanating warmth and kindness. Young Chammi – acknowledged as Shamima but once by the author – has the status of one whose mother died and whose father left to live elsewhere, his new life overrun by new wives and their offspring. Beautiful, unwanted Chammi, treated with love by Aunty, somehow became that wild, shrewish girl whose tantrums are feared to such an extent that when her marriage is arranged, no one dares to inform her. Kareeman Bua, who came with her mother in the mistress’s dowry, lives a life of domestic servitude, devoted to the family, oblivious to scars formed by disproportionate rage on her body.This book is not just about women and their cloistered existence; it also shows how global events infiltrate the courtyard and shape their lives. It is set in a period of Indian history of which authentic details have been so obscured by political propaganda and regressive patriotism, that what remains in textbooks and the general mindset is a trite caricature of what once truly was. Khadija Mastur was known for her own underprivileged background and her political views, and the lives and conversations in this book open a window on the actual terrain of the era. Here is a Muslim household, steeped in tradition and piety, and the nationalist reality portrayed is complex. There is an overwhelming love for country, which leads to sacrifice of family life and personal comfort, imprisonment, suffering and death. There is also an irreparable rift between members of the family, some of whom follow the Muslim League while others consider them traitors, believing that party to be an instrument of further divisiveness and a fundamental cause of inciting violence and continuing strife. The most enchanting voice in the book is of Aliya, the heroine, who shares her reality with the reader. Sensitive and thoughtful, Aliya feels the pain of the women – but just as much of the men and their inability to bring happiness to their families. The stories on which Aliya thrives mirror through romantic legend the lives of their characters, fueling their wellsprings of emotion and, more than once, resulting in ghastly tragedy. (Women would commit suicide for love and depart as examples of perfect fidelity, and then, some dark night, men would appear to momentarily light a lamp over the tomb, then leave, and that was that). Intertwined with the tradition of stories originating in Arabia runs a strong and persistent strain with the stories and symbols of Krishna and Rama making numerous appearances.And the most beautiful scenes are as the book ends, in the newly-created Pakistan. The clamour and strife subside and wonderful fictional coincidences transpire, one bringing a tragic finality and another opening out onto a horizon of love and hope.This review was written for

Hindustan Times

and appeared on Saturday 23 March 2018.

Published on March 24, 2019 20:10

March 16, 2019

The Sunlight Plane by Damini Kane

Coming of age, in BombayI started reading this book primarily from curiosity to learn what a 22-year-old who grew up in a home full of books, and with parents who are both writers, would produce. Not surprisingly, it turned out to be a mature, well-written, entertaining story with strong characters. The extras that I enjoyed were its solid moral base and quite a few giggles along the way.

Coming of age, in BombayI started reading this book primarily from curiosity to learn what a 22-year-old who grew up in a home full of books, and with parents who are both writers, would produce. Not surprisingly, it turned out to be a mature, well-written, entertaining story with strong characters. The extras that I enjoyed were its solid moral base and quite a few giggles along the way.The Sunlight Plane is a book about a group of children and written in simple, engaging language. I emailed Damini to ask if she’d had a reader in mind while writing it, and she replied, “I imagined the reader to be anywhere above the age of 18.” Actually, while reading it I’d felt I’d recommend it to ‘young adults’, expecting them to enjoy and gain from it the way they would with books like Catcher in the Rye or The God of Small Things– or even Portnoy’s Complaint. This book does not have graphic and potentially controversial scenes as the last named, it does have a central issue which is quite horrific and it clearly outlines the trauma and the dilemmas of the children who encounter it from different angles.Damini told me that she started writing this book when shewas 19, when she was in college. She started with a clear idea of who the characters were, and how their interpersonal conflicts would further the plot. The first draft took six months, and after that it was just rewrites and editing. While this book will not have a sequel, Damini is working on monthly fantasy and science fiction short stories, just for practice. These she uploads on her blog www.everythingkane.wordpress.com.In answer to my question about her advise to aspiring young writers, she replied:

Practice and read, read and practice! There's no short-cut around this. It's especially important to practice the things you're not as good at. Personally, I'm doing these monthly short stories because I'm not half as confident at writing short fiction. Working on what you're weaker at will only make you better.Good advice for anyone doing anything, is what I thought, and it felt good to know that young people today aren’t all low-attention-span, low-hanging-fruit gimme-gimme type people as it quite often fearfully appears to be.

Published on March 16, 2019 20:24

February 22, 2019

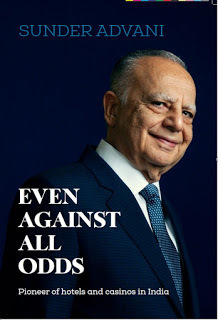

Even Against all Odds by Sunder Advani

Looking backOn Tuesday, I attended a book launch at the US Consulate, an event held to honour an extraordinary person and his commitment to Indo-US relations.

When I first met Sunder Advani a few months ago through my research into pre-Partition Sindh, I had no idea who he was. His family’s story was fascinating, and I felt gratified when he liked the way I had presented it, and commissioned me to work with him on his memoirs. As we proceeded through the story of his life, I felt surprised and impressed to learn the extent of his contribution to the Indian hotel and hospitality industry. I have lived in India all my life, enjoyed the Taj and Oberoi in Bombay when I was young, and later hotels of the many international chains that entered in the 1990s. However, I had absolutely no idea that there was an individual, one sole person, and that too someone without family money or political connections or even a home of his own when he first came to live in Bombay – who had significantly shaped India’s hotel industry through his personal vision and efforts.

Edgard D Cagan, Consul General and Sunder AdvaniSunder had been just too busy working, and struggling to get things done, and his story had never been told until now. For a full fifty years, Sunder had also been committed to developing stronger ties between India and the US – starting long before the time when the two countries were considered natural allies, as they are today. It was a fitting tribute that the US Consulate launched his memoirs a few weeks after they were published on his eightieth birthday.

Edgard D Cagan, Consul General and Sunder AdvaniSunder had been just too busy working, and struggling to get things done, and his story had never been told until now. For a full fifty years, Sunder had also been committed to developing stronger ties between India and the US – starting long before the time when the two countries were considered natural allies, as they are today. It was a fitting tribute that the US Consulate launched his memoirs a few weeks after they were published on his eightieth birthday.

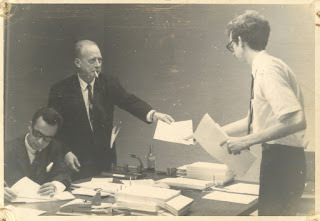

Sunder (seated, left) with his boss, economist Frank Piovia,

Sunder (seated, left) with his boss, economist Frank Piovia,at EBS Consultants, Washington DC, 1968In the 1960s, as a young man living in the USA, Sunder worked in a prestigious and well-paying job where he used his education and analytical abilities to provide information on the basis of which decisions important to that country would be taken. At his father’s urging, he left it behind and came to live in India – then still a developing nation, newly independent, overpopulated, rife with poverty, illiteracy and corruption. Every step of the next fifty years was fraught with peril – and bravely defended. He was badly let down by his partners and suffered a series of business betrayals, hostile takeovers and concept pirates. Through it all, he worked his way through the hardened maze of government bureaucracy with steadfast courtesy and tenacity, endlessly seeking and acquiring one permission after the other to conduct his business and grow it.

With Kemmons Wilson, Founder and Chairman of Holiday Inns Inc.

With Kemmons Wilson, Founder and Chairman of Holiday Inns Inc.in his office in Memphis, Tennessee, 1970.Sunder Advani was the first person to bring international standards to the hospitality industry in India, through the mature systems and processes of Holiday Inns Inc., USA. His visionary public issue in 1972 – preceding those of both Taj (Oriental Hotels) and Oberoi (EIH Limited) – was fully subscribed.In the 1970s, when Bombay was serviced by just one domestic airline and just one airport for domestic and a few international flights, Sunder set up the country’s first sound-proof airport hotel and flight kitchen. In 1978, a time before mobile phones, the hotel had the only discotheque in the Bombay suburbs and a pool with a jacuzzi. Sunder Advani was among the first to see the potential in Goa and work single-mindedly to develop it for tourism and foreign-exchange earnings. In 1988, when Goa only had the infrastructure to attract backpackers, his was one of the earliest luxury hotels. It was viciously maligned and put under litigation, despite his having kept strictly within the limits of the law. To extend tourist spend in Goa over the lean monsoon months, Sunder envisioned indoor entertainment in the form of casinos. His offshore Casino Caravela provided an elegant evening and attracted well-heeled spenders. When competition made the playing field murky, Sunder gracefully withdrew.

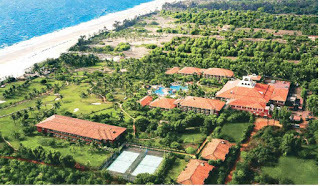

The Five-Star Caravela Resort, luxury living surrounded by

The Five-Star Caravela Resort, luxury living surrounded bysmiling faces and a beach of soft, powder-white sand.One of the most interesting things I observed about Sunder is his commitment to a good life. He works hard, but his family is always at the centre of things. All through the years, he has travelled on work and taken them along with him on enjoyable holidays. Today, at eighty just as much as when he was a young man, he continues to work hard, committed not just to his own Caravela Resort in Goa but also to his continuous campaigns to increase tourism in India. You can get a sense of his achievements in the glowing Foreword Amitabh Kant wrote to his book:

Published on February 22, 2019 06:55

January 12, 2019

Mappillai by Carlo Pizzati

Happily ever after

Carlo Pizzati, who suffers terribly from ‘the most interesting man in the world’ syndrome, came to India as a ‘yoga-person’, and stayed on. He married a woman who proposed to him in the course of their relationship. “I think you should marry me. Hello? I’m a caaatch!” she said, and he agreed. Many locals thought he wouldn’t last but, so far so good, he has. It can’t be easy because even the gated communities named Bella Rive and Calm Waters are ridden with mice and snakes, and when the tsunami comes it will wipe away your foundations.

Carlo Pizzati, who suffers terribly from ‘the most interesting man in the world’ syndrome, came to India as a ‘yoga-person’, and stayed on. He married a woman who proposed to him in the course of their relationship. “I think you should marry me. Hello? I’m a caaatch!” she said, and he agreed. Many locals thought he wouldn’t last but, so far so good, he has. It can’t be easy because even the gated communities named Bella Rive and Calm Waters are ridden with mice and snakes, and when the tsunami comes it will wipe away your foundations.This book is partly biographical, an account of the author’s life in India in a beach house with the woman he loves and their large family of stray dogs. His love for his wife, respect for her family, and admiration for her very cool chemical-engineer father are refrains so persistent that I wondered what exactly he was trying to sell. But Carlo also claims to grow luscious tomatoes and splendid roses on inhospitable beach sand so perhaps it was only good energy manifesting.Besides a little about his earlier life, and what happens to him in village Paramankeni and environs, this book is also quite a lot about Carlo Pizzati’s conclusions about all kinds of things in an incredibly complex land! While he stoutly claims not to be Wendy Doniger, William Dalrymple, Patrick French, – or even Megasthenes, Xuanzang, Al Biruni (and so on) and therefore this CANNOT be ‘an India book’, he does have his own engaging theories about the way things work here. Arriving in ‘the watershed year of 2008’ he embraced ‘Mamma India’ in a period of exceptional cyclones, of Tata Nano, Premier League, an Indian winning the Booker Prize and 8% economic growth. Through his journey as a ‘yoga-person’, someone who made exceptional choices and landed up as a mapillai (Tamil for ‘son-in-law’) of Gujarati Jain in-laws in Besant Nagar, Chennai, Carlo’s narrative is strewn with interesting data and contextual information. He well understands the importance of the mango and its role in parochialism and identity across India. He has observed women staying married to violent mummy-spoiled brutish husbands, surrounded by friends and family members who may gossip but never intervene. He marvels at how Indian law allows a person named in a suicide note as psychologically responsible for the suicide, to be arrested, tried and at times convicted. When he muses on the auntie-uncle cultural nomenclature, it is to spot the auntie concealed within the hottie, the uncle germinating in the stud; to appreciate the stud nature in an aged uncle with a wild streak and the charming seduction of the hottie quietly inhabiting the auntie. Carlo Pizzati experiences India’s synthesis of religion, politics and commerce, and highlights one of the exceptional icons of this nexus: the best dressed poor people in the globe, with their multifarious saris, striped lungis and wrap-around turbans. In his relatively rare setting for ‘an India book’, he approaches the ‘marvellous human experiment called India’ – from its outskirts, a location of limitless sea and sky where open defecation abounds. And the brave, sporting Carlo attempted open defecation too, but sadly found himself unable to perform.In slow, contemplative sentences and in rapid exclamatory ones, his prose and his theme switch rapidly. Perhaps this is just a modern book, aimed at the sophisticated short-attention-span reader who delights in toying with new formats – but it is rather effervescent at times (like a stereotypical Italian?) Not surprisingly, Carlo has mastered and neatly documented Indian hand gestures. Fingers pointing inwards and then, suddenly swinging out an open hand to say ‘all!’. And the sudden twist with index finger pointing upwards for ‘wtf?’The insight that most impressed me was the truth about why natives consider vellais (Tamil for ‘whiteys’) better than them. It’s not the scars of colonialism but because they are – SPOILER ALERT – mentally freer, with fewer social obligations to succeed, to marry, and behave as required.And the claim that most annoyed me was that “Indian women are like Italian men”, indicating that the entire population of Indian women tends to encircle men, sniffing to select the delicacy they might savour. Was this supposed to be a compliment? An enticement? A joke? I don’t think so.This review was written for Hindustan Times and appeared on Saturday 12 Jan 2018.

Published on January 12, 2019 18:37

July 6, 2018

Ladders in the Sky by Murli Melwani

A gift of his travels

I picked up this book and started reading it as reference material for a research paper on the global Sindhi diaspora. The author is a global Sindhi businessman and I knew, in a patronising sort of way, that I was surely going to learn something interesting. Halfway through the fourth story, when I had to get something else done and it was a wrench to put the book down, I realised that I was in fact reading entranced. These were splendid stories: good plots, lifelike characters, beautifully laid out in clean, distinctive language. What made them even more fascinating was that each one is set in a different, exotic location. Murli Melwani is an inveterate traveller and this collection, as the jacket describes it, is a “gift of his travels”. 15 of the 23 stories are set in different parts of India and in them we encounter separatist movements, landslides, cramped urban spaces, insights into different aspects of religious devotion and various other complex situations in unexpected locales. Murli grew up in Shillong. Between school and college, he travelled a lot and visited different parts of India. Later he worked in the English Department at Sankerdev College, then took up a Coca Cola distributorship and for a while ran a bookstore. In time, he moved to work in Taiwan and his job took him to countries around the world, doing something many Sindhis do.A little more than half the book features this diaspora, families which originated in Sindh and now live and do business in countries around the world. Water on a Hot Plate is set in Toronto. Hari and Rajni are visiting their son and in this story, they meet an Indian Chinese lady who runs a restaurant there. They converse with her in Mandarin – from their several years in Taiwan; of course they speak to her in Hindi and English too. From the Bollywood music playing in the background, Hari can tell that the India she belonged to was not the India he had left. Resh, their lunch guest, is visiting from Curacao. She speaks Dutch and English and even idiomatic Papiamentu – a Portuguese and Spanish-based Creole language – but not Sindhi.Writing a Fairy Tale is a gripping love story in which we somehow journey into the rainforests of eco-versatile Chile – and also, unexpectedly, encounter the Arabic aspects of the country too. The Mexican Girlfriend is also a love story, and though set in a home by a lake where migratory birds flock – a real place – has more sinister than exotic twists. Followed by The Bhorwani Marriage, a high-energy satire of Sindhi weddings, including an expose of the business opportunities offered by matchmaking in the diaspora, it appears that Sindhis don’t really do romance. Family comes overwhelmingly first; business and profits are a priority; living comfort is never going to be sacrificed for a lover. It’s not that everyone in the community is money-minded. This book takes us beyond that stereotype, with businessmen who are polite, mature and love to read. And the skilled portrayals of many different kinds of relationships reveal the author to be an exceptionally subtle and discerning person himself. Even the businessman in Shiva with a Garland, lonely in his marriage, “had grown sensitive and become aware of many things. He had come to understand the right and wrong of things and the meaning and worth of happiness.”Still, Murli is not just an observer of humans and their situation, not just a weaver of tales. He is a skilled businessman too and his stories give us practical never-fail tips on selling, exposure to business cycles, and the understanding that large investments, even the most obvious, could turn out to be ruinous. There are young employers who clone themselves, swiftly learning the trade and soon enough snatching it out from under their employer’s feet to set up as competitors. Some families have members living in other countries: the father ships out goods from a manufacturing location while the sons sell in other parts of the world, creating hugely profitable companies which run around the clock. So while Murli’s Master’s is in English Literature, this book tells all kinds of things he didn’t learn at IIM-A.This review was written for Hindustan Times and appeared on Saturday 9 Jun 2018 and can be read on this link.

I picked up this book and started reading it as reference material for a research paper on the global Sindhi diaspora. The author is a global Sindhi businessman and I knew, in a patronising sort of way, that I was surely going to learn something interesting. Halfway through the fourth story, when I had to get something else done and it was a wrench to put the book down, I realised that I was in fact reading entranced. These were splendid stories: good plots, lifelike characters, beautifully laid out in clean, distinctive language. What made them even more fascinating was that each one is set in a different, exotic location. Murli Melwani is an inveterate traveller and this collection, as the jacket describes it, is a “gift of his travels”. 15 of the 23 stories are set in different parts of India and in them we encounter separatist movements, landslides, cramped urban spaces, insights into different aspects of religious devotion and various other complex situations in unexpected locales. Murli grew up in Shillong. Between school and college, he travelled a lot and visited different parts of India. Later he worked in the English Department at Sankerdev College, then took up a Coca Cola distributorship and for a while ran a bookstore. In time, he moved to work in Taiwan and his job took him to countries around the world, doing something many Sindhis do.A little more than half the book features this diaspora, families which originated in Sindh and now live and do business in countries around the world. Water on a Hot Plate is set in Toronto. Hari and Rajni are visiting their son and in this story, they meet an Indian Chinese lady who runs a restaurant there. They converse with her in Mandarin – from their several years in Taiwan; of course they speak to her in Hindi and English too. From the Bollywood music playing in the background, Hari can tell that the India she belonged to was not the India he had left. Resh, their lunch guest, is visiting from Curacao. She speaks Dutch and English and even idiomatic Papiamentu – a Portuguese and Spanish-based Creole language – but not Sindhi.Writing a Fairy Tale is a gripping love story in which we somehow journey into the rainforests of eco-versatile Chile – and also, unexpectedly, encounter the Arabic aspects of the country too. The Mexican Girlfriend is also a love story, and though set in a home by a lake where migratory birds flock – a real place – has more sinister than exotic twists. Followed by The Bhorwani Marriage, a high-energy satire of Sindhi weddings, including an expose of the business opportunities offered by matchmaking in the diaspora, it appears that Sindhis don’t really do romance. Family comes overwhelmingly first; business and profits are a priority; living comfort is never going to be sacrificed for a lover. It’s not that everyone in the community is money-minded. This book takes us beyond that stereotype, with businessmen who are polite, mature and love to read. And the skilled portrayals of many different kinds of relationships reveal the author to be an exceptionally subtle and discerning person himself. Even the businessman in Shiva with a Garland, lonely in his marriage, “had grown sensitive and become aware of many things. He had come to understand the right and wrong of things and the meaning and worth of happiness.”Still, Murli is not just an observer of humans and their situation, not just a weaver of tales. He is a skilled businessman too and his stories give us practical never-fail tips on selling, exposure to business cycles, and the understanding that large investments, even the most obvious, could turn out to be ruinous. There are young employers who clone themselves, swiftly learning the trade and soon enough snatching it out from under their employer’s feet to set up as competitors. Some families have members living in other countries: the father ships out goods from a manufacturing location while the sons sell in other parts of the world, creating hugely profitable companies which run around the clock. So while Murli’s Master’s is in English Literature, this book tells all kinds of things he didn’t learn at IIM-A.This review was written for Hindustan Times and appeared on Saturday 9 Jun 2018 and can be read on this link.

I picked up this book and started reading it as reference material for a research paper on the global Sindhi diaspora. The author is a global Sindhi businessman and I knew, in a patronising sort of way, that I was surely going to learn something interesting. Halfway through the fourth story, when I had to get something else done and it was a wrench to put the book down, I realised that I was in fact reading entranced. These were splendid stories: good plots, lifelike characters, beautifully laid out in clean, distinctive language. What made them even more fascinating was that each one is set in a different, exotic location. Murli Melwani is an inveterate traveller and this collection, as the jacket describes it, is a “gift of his travels”. 15 of the 23 stories are set in different parts of India and in them we encounter separatist movements, landslides, cramped urban spaces, insights into different aspects of religious devotion and various other complex situations in unexpected locales. Murli grew up in Shillong. Between school and college, he travelled a lot and visited different parts of India. Later he worked in the English Department at Sankerdev College, then took up a Coca Cola distributorship and for a while ran a bookstore. In time, he moved to work in Taiwan and his job took him to countries around the world, doing something many Sindhis do.A little more than half the book features this diaspora, families which originated in Sindh and now live and do business in countries around the world. Water on a Hot Plate is set in Toronto. Hari and Rajni are visiting their son and in this story, they meet an Indian Chinese lady who runs a restaurant there. They converse with her in Mandarin – from their several years in Taiwan; of course they speak to her in Hindi and English too. From the Bollywood music playing in the background, Hari can tell that the India she belonged to was not the India he had left. Resh, their lunch guest, is visiting from Curacao. She speaks Dutch and English and even idiomatic Papiamentu – a Portuguese and Spanish-based Creole language – but not Sindhi.Writing a Fairy Tale is a gripping love story in which we somehow journey into the rainforests of eco-versatile Chile – and also, unexpectedly, encounter the Arabic aspects of the country too. The Mexican Girlfriend is also a love story, and though set in a home by a lake where migratory birds flock – a real place – has more sinister than exotic twists. Followed by The Bhorwani Marriage, a high-energy satire of Sindhi weddings, including an expose of the business opportunities offered by matchmaking in the diaspora, it appears that Sindhis don’t really do romance. Family comes overwhelmingly first; business and profits are a priority; living comfort is never going to be sacrificed for a lover. It’s not that everyone in the community is money-minded. This book takes us beyond that stereotype, with businessmen who are polite, mature and love to read. And the skilled portrayals of many different kinds of relationships reveal the author to be an exceptionally subtle and discerning person himself. Even the businessman in Shiva with a Garland, lonely in his marriage, “had grown sensitive and become aware of many things. He had come to understand the right and wrong of things and the meaning and worth of happiness.”Still, Murli is not just an observer of humans and their situation, not just a weaver of tales. He is a skilled businessman too and his stories give us practical never-fail tips on selling, exposure to business cycles, and the understanding that large investments, even the most obvious, could turn out to be ruinous. There are young employers who clone themselves, swiftly learning the trade and soon enough snatching it out from under their employer’s feet to set up as competitors. Some families have members living in other countries: the father ships out goods from a manufacturing location while the sons sell in other parts of the world, creating hugely profitable companies which run around the clock. So while Murli’s Master’s is in English Literature, this book tells all kinds of things he didn’t learn at IIM-A.This review was written for Hindustan Times and appeared on Saturday 9 Jun 2018 and can be read on this link.

I picked up this book and started reading it as reference material for a research paper on the global Sindhi diaspora. The author is a global Sindhi businessman and I knew, in a patronising sort of way, that I was surely going to learn something interesting. Halfway through the fourth story, when I had to get something else done and it was a wrench to put the book down, I realised that I was in fact reading entranced. These were splendid stories: good plots, lifelike characters, beautifully laid out in clean, distinctive language. What made them even more fascinating was that each one is set in a different, exotic location. Murli Melwani is an inveterate traveller and this collection, as the jacket describes it, is a “gift of his travels”. 15 of the 23 stories are set in different parts of India and in them we encounter separatist movements, landslides, cramped urban spaces, insights into different aspects of religious devotion and various other complex situations in unexpected locales. Murli grew up in Shillong. Between school and college, he travelled a lot and visited different parts of India. Later he worked in the English Department at Sankerdev College, then took up a Coca Cola distributorship and for a while ran a bookstore. In time, he moved to work in Taiwan and his job took him to countries around the world, doing something many Sindhis do.A little more than half the book features this diaspora, families which originated in Sindh and now live and do business in countries around the world. Water on a Hot Plate is set in Toronto. Hari and Rajni are visiting their son and in this story, they meet an Indian Chinese lady who runs a restaurant there. They converse with her in Mandarin – from their several years in Taiwan; of course they speak to her in Hindi and English too. From the Bollywood music playing in the background, Hari can tell that the India she belonged to was not the India he had left. Resh, their lunch guest, is visiting from Curacao. She speaks Dutch and English and even idiomatic Papiamentu – a Portuguese and Spanish-based Creole language – but not Sindhi.Writing a Fairy Tale is a gripping love story in which we somehow journey into the rainforests of eco-versatile Chile – and also, unexpectedly, encounter the Arabic aspects of the country too. The Mexican Girlfriend is also a love story, and though set in a home by a lake where migratory birds flock – a real place – has more sinister than exotic twists. Followed by The Bhorwani Marriage, a high-energy satire of Sindhi weddings, including an expose of the business opportunities offered by matchmaking in the diaspora, it appears that Sindhis don’t really do romance. Family comes overwhelmingly first; business and profits are a priority; living comfort is never going to be sacrificed for a lover. It’s not that everyone in the community is money-minded. This book takes us beyond that stereotype, with businessmen who are polite, mature and love to read. And the skilled portrayals of many different kinds of relationships reveal the author to be an exceptionally subtle and discerning person himself. Even the businessman in Shiva with a Garland, lonely in his marriage, “had grown sensitive and become aware of many things. He had come to understand the right and wrong of things and the meaning and worth of happiness.”Still, Murli is not just an observer of humans and their situation, not just a weaver of tales. He is a skilled businessman too and his stories give us practical never-fail tips on selling, exposure to business cycles, and the understanding that large investments, even the most obvious, could turn out to be ruinous. There are young employers who clone themselves, swiftly learning the trade and soon enough snatching it out from under their employer’s feet to set up as competitors. Some families have members living in other countries: the father ships out goods from a manufacturing location while the sons sell in other parts of the world, creating hugely profitable companies which run around the clock. So while Murli’s Master’s is in English Literature, this book tells all kinds of things he didn’t learn at IIM-A.This review was written for Hindustan Times and appeared on Saturday 9 Jun 2018 and can be read on this link.

Published on July 06, 2018 11:37

February 23, 2018

Paiso by Maya Bathija

Well told, but only a small part of the picture

This book is well-structured and engaging, and provides an insight into five Sindhi family businesses. The Harilelas set out in retail and built their fortune in custom tailoring for American soldiers on R&R, turning Hong Kong into a popular global destination for mail-order suits. Merrimac Ventures, real estate giants and urban developers in the US, came about through the sheer bravery and brilliance of the indomitable Romila Motwani. Jet-setting Harish Fabiani grew to extraordinary wealth and fame using his native brilliance, and hobnobs with the likes of Donald Trump. The Lakhi Group is a diamond empire so professionally run and a family life so admirably simple and equal-opportunity that it shines forth in this narrative like a dazzling solitaire. And Jitendra ‘Jitu’ Virwani built his real-estate dominion brick by brick, racing ahead with giant leaps and battling all the way.Each of these extraordinary stories has elements of some of the characteristic Sindhi ways of doing business: difficult times bravely faced; fearless risk-taking and the ability to move with great swiftness when opportunity is sighted; intensely close and devoted family relationships; the role of women defined by family background (Sindhis are remarkably heterogeneous in this and a range of other important matters); the talent for shoring up against business cycles with real estate; and an impressively large commitment to philanthropy, sometimes vulgarly demanding attention, but often (in fact in more cases than can ever be known) completely anonymous. However, the book also has disturbingly anachronistic statements like “the Fabiani family has its roots in Pakistan.” (Roots, really? But Pakistan only came into existence in 1947 and that was when the Sindhis were rudely evicted!) Sindh has an ancient tradition of trade and mobility and its own range of rich products. Marco Polo wrote of the curiosities of Chin and Machin, and ‘the beautiful products of Hind and Sindh, laden on large ships which sail like mountains with the wings of the wind on the surface of the water.’ In the 1860s, a group of young men set out on the British steamship routes and ventured into trade in ports around the world. The retail chains of these early capitalists, M Dialdas, JT Chanrai, KAJ Chotirmal and others, formed the first Sindhi multinational companies. Inland, the money lenders of Shikarpur had extended their services into a phenomenally secure and sophisticated banking system with bases in South India and a network of agents on the trade routes extending from Central Asia into Russia, China and Japan. After Partition, many of the Sindhis forced out of their ancestral homeland with nothing, took to trading as a dignified means of earning an honest living in the places where they settled. Working on low margins, selling the packaging for an extra buck, they interfered with the profits of long-established trade cartels, for which they were resented and bitterly derided as ‘cheats’. Most of them had not been to Harvard Business School but they understood that the key to business success is to directly address the customers’ need, and they rebuilt their fortunes by doing precisely that: in garments, construction, education, and in time in every other industry. Partition also swelled the global outposts into communities and there are Sindhi shopkeepers in ports around the world. Many of the 'shopkeepers' grew their businesses with enterprise (and real estate) and are billionaires just as much as the five profiled in Paiso. Many of them retain links with each other, the remarkable phenomenon of a community which lost its roots when evicted from its homeland by Partition – but retains its connection in strong links which encircle the globe. There are Sindhi shops across the length and breadth of India too: Coonoor market, so remote in geography and culture, had a Quetta Stores when I was a child. So the phenomenon of Sindhi business is by no means restricted to glamorous billionaires.Similarly, it is true that traditional Sindhi business families considered education “a waste of time” and that this is by no means the case today. What is less known is that a huge population of Sindhis did hold education to be extremely important. These include the entrepreneurs coming from three and four generations of education who established the Indian multinational companies Onida (Mirchandanis) and Blue Star (Advanis); the global retail giant Landmark Group (Jagtianis); and in the case of Inlaks (Shivdasanis), three generations of Oxbridge education. The Ador Group, another multinational conglomerate, continues with the third and fourth generation of university educated partners who started their business in Sindh 110 years ago. As for Dr NP Tolani of the highly reputed Tolani Shipping, he earned his PhD in 22 months – still a record at Cornell – and returned to Bombay in 1964, intent on taking up a business in which there was as little corruption as possible in India.There are many more and most, despite strong bonds to their community and their families, and linked by the complex unspoken trauma of Partition, prefer to remain low profile and never flaunt their Sindhiness, perhaps to avoid being tarred with that ‘loud and vulgar’ brush that haunts the Sindhis, doomed as they seem to be to be represented by their flamboyant, attention-seeking brethren. Perhaps this book will help bring them out of the closet.I wrote the above review for Hindustan Times and it was carried today. You can read it in the newspaper online here but without the line highlighted above which I have just added. It is interesting to see that HT illustrated this review with a photo of Harish Fabiani, one of the billionaires featured in this book, and his wife – who, according to Paiso, he doesn't 'allow' to call him by his name.

This book is well-structured and engaging, and provides an insight into five Sindhi family businesses. The Harilelas set out in retail and built their fortune in custom tailoring for American soldiers on R&R, turning Hong Kong into a popular global destination for mail-order suits. Merrimac Ventures, real estate giants and urban developers in the US, came about through the sheer bravery and brilliance of the indomitable Romila Motwani. Jet-setting Harish Fabiani grew to extraordinary wealth and fame using his native brilliance, and hobnobs with the likes of Donald Trump. The Lakhi Group is a diamond empire so professionally run and a family life so admirably simple and equal-opportunity that it shines forth in this narrative like a dazzling solitaire. And Jitendra ‘Jitu’ Virwani built his real-estate dominion brick by brick, racing ahead with giant leaps and battling all the way.Each of these extraordinary stories has elements of some of the characteristic Sindhi ways of doing business: difficult times bravely faced; fearless risk-taking and the ability to move with great swiftness when opportunity is sighted; intensely close and devoted family relationships; the role of women defined by family background (Sindhis are remarkably heterogeneous in this and a range of other important matters); the talent for shoring up against business cycles with real estate; and an impressively large commitment to philanthropy, sometimes vulgarly demanding attention, but often (in fact in more cases than can ever be known) completely anonymous. However, the book also has disturbingly anachronistic statements like “the Fabiani family has its roots in Pakistan.” (Roots, really? But Pakistan only came into existence in 1947 and that was when the Sindhis were rudely evicted!) Sindh has an ancient tradition of trade and mobility and its own range of rich products. Marco Polo wrote of the curiosities of Chin and Machin, and ‘the beautiful products of Hind and Sindh, laden on large ships which sail like mountains with the wings of the wind on the surface of the water.’ In the 1860s, a group of young men set out on the British steamship routes and ventured into trade in ports around the world. The retail chains of these early capitalists, M Dialdas, JT Chanrai, KAJ Chotirmal and others, formed the first Sindhi multinational companies. Inland, the money lenders of Shikarpur had extended their services into a phenomenally secure and sophisticated banking system with bases in South India and a network of agents on the trade routes extending from Central Asia into Russia, China and Japan. After Partition, many of the Sindhis forced out of their ancestral homeland with nothing, took to trading as a dignified means of earning an honest living in the places where they settled. Working on low margins, selling the packaging for an extra buck, they interfered with the profits of long-established trade cartels, for which they were resented and bitterly derided as ‘cheats’. Most of them had not been to Harvard Business School but they understood that the key to business success is to directly address the customers’ need, and they rebuilt their fortunes by doing precisely that: in garments, construction, education, and in time in every other industry. Partition also swelled the global outposts into communities and there are Sindhi shopkeepers in ports around the world. Many of the 'shopkeepers' grew their businesses with enterprise (and real estate) and are billionaires just as much as the five profiled in Paiso. Many of them retain links with each other, the remarkable phenomenon of a community which lost its roots when evicted from its homeland by Partition – but retains its connection in strong links which encircle the globe. There are Sindhi shops across the length and breadth of India too: Coonoor market, so remote in geography and culture, had a Quetta Stores when I was a child. So the phenomenon of Sindhi business is by no means restricted to glamorous billionaires.Similarly, it is true that traditional Sindhi business families considered education “a waste of time” and that this is by no means the case today. What is less known is that a huge population of Sindhis did hold education to be extremely important. These include the entrepreneurs coming from three and four generations of education who established the Indian multinational companies Onida (Mirchandanis) and Blue Star (Advanis); the global retail giant Landmark Group (Jagtianis); and in the case of Inlaks (Shivdasanis), three generations of Oxbridge education. The Ador Group, another multinational conglomerate, continues with the third and fourth generation of university educated partners who started their business in Sindh 110 years ago. As for Dr NP Tolani of the highly reputed Tolani Shipping, he earned his PhD in 22 months – still a record at Cornell – and returned to Bombay in 1964, intent on taking up a business in which there was as little corruption as possible in India.There are many more and most, despite strong bonds to their community and their families, and linked by the complex unspoken trauma of Partition, prefer to remain low profile and never flaunt their Sindhiness, perhaps to avoid being tarred with that ‘loud and vulgar’ brush that haunts the Sindhis, doomed as they seem to be to be represented by their flamboyant, attention-seeking brethren. Perhaps this book will help bring them out of the closet.I wrote the above review for Hindustan Times and it was carried today. You can read it in the newspaper online here but without the line highlighted above which I have just added. It is interesting to see that HT illustrated this review with a photo of Harish Fabiani, one of the billionaires featured in this book, and his wife – who, according to Paiso, he doesn't 'allow' to call him by his name.

This review was written for Hindustan Times and appeared on Saturday 24 Feb 2018.

This book is well-structured and engaging, and provides an insight into five Sindhi family businesses. The Harilelas set out in retail and built their fortune in custom tailoring for American soldiers on R&R, turning Hong Kong into a popular global destination for mail-order suits. Merrimac Ventures, real estate giants and urban developers in the US, came about through the sheer bravery and brilliance of the indomitable Romila Motwani. Jet-setting Harish Fabiani grew to extraordinary wealth and fame using his native brilliance, and hobnobs with the likes of Donald Trump. The Lakhi Group is a diamond empire so professionally run and a family life so admirably simple and equal-opportunity that it shines forth in this narrative like a dazzling solitaire. And Jitendra ‘Jitu’ Virwani built his real-estate dominion brick by brick, racing ahead with giant leaps and battling all the way.Each of these extraordinary stories has elements of some of the characteristic Sindhi ways of doing business: difficult times bravely faced; fearless risk-taking and the ability to move with great swiftness when opportunity is sighted; intensely close and devoted family relationships; the role of women defined by family background (Sindhis are remarkably heterogeneous in this and a range of other important matters); the talent for shoring up against business cycles with real estate; and an impressively large commitment to philanthropy, sometimes vulgarly demanding attention, but often (in fact in more cases than can ever be known) completely anonymous. However, the book also has disturbingly anachronistic statements like “the Fabiani family has its roots in Pakistan.” (Roots, really? But Pakistan only came into existence in 1947 and that was when the Sindhis were rudely evicted!) Sindh has an ancient tradition of trade and mobility and its own range of rich products. Marco Polo wrote of the curiosities of Chin and Machin, and ‘the beautiful products of Hind and Sindh, laden on large ships which sail like mountains with the wings of the wind on the surface of the water.’ In the 1860s, a group of young men set out on the British steamship routes and ventured into trade in ports around the world. The retail chains of these early capitalists, M Dialdas, JT Chanrai, KAJ Chotirmal and others, formed the first Sindhi multinational companies. Inland, the money lenders of Shikarpur had extended their services into a phenomenally secure and sophisticated banking system with bases in South India and a network of agents on the trade routes extending from Central Asia into Russia, China and Japan. After Partition, many of the Sindhis forced out of their ancestral homeland with nothing, took to trading as a dignified means of earning an honest living in the places where they settled. Working on low margins, selling the packaging for an extra buck, they interfered with the profits of long-established trade cartels, for which they were resented and bitterly derided as ‘cheats’. Most of them had not been to Harvard Business School but they understood that the key to business success is to directly address the customers’ need, and they rebuilt their fortunes by doing precisely that: in garments, construction, education, and in time in every other industry. Partition also swelled the global outposts into communities and there are Sindhi shopkeepers in ports around the world. Many of the 'shopkeepers' grew their businesses with enterprise (and real estate) and are billionaires just as much as the five profiled in Paiso. Many of them retain links with each other, the remarkable phenomenon of a community which lost its roots when evicted from its homeland by Partition – but retains its connection in strong links which encircle the globe. There are Sindhi shops across the length and breadth of India too: Coonoor market, so remote in geography and culture, had a Quetta Stores when I was a child. So the phenomenon of Sindhi business is by no means restricted to glamorous billionaires.Similarly, it is true that traditional Sindhi business families considered education “a waste of time” and that this is by no means the case today. What is less known is that a huge population of Sindhis did hold education to be extremely important. These include the entrepreneurs coming from three and four generations of education who established the Indian multinational companies Onida (Mirchandanis) and Blue Star (Advanis); the global retail giant Landmark Group (Jagtianis); and in the case of Inlaks (Shivdasanis), three generations of Oxbridge education. The Ador Group, another multinational conglomerate, continues with the third and fourth generation of university educated partners who started their business in Sindh 110 years ago. As for Dr NP Tolani of the highly reputed Tolani Shipping, he earned his PhD in 22 months – still a record at Cornell – and returned to Bombay in 1964, intent on taking up a business in which there was as little corruption as possible in India.There are many more and most, despite strong bonds to their community and their families, and linked by the complex unspoken trauma of Partition, prefer to remain low profile and never flaunt their Sindhiness, perhaps to avoid being tarred with that ‘loud and vulgar’ brush that haunts the Sindhis, doomed as they seem to be to be represented by their flamboyant, attention-seeking brethren. Perhaps this book will help bring them out of the closet.I wrote the above review for Hindustan Times and it was carried today. You can read it in the newspaper online here but without the line highlighted above which I have just added. It is interesting to see that HT illustrated this review with a photo of Harish Fabiani, one of the billionaires featured in this book, and his wife – who, according to Paiso, he doesn't 'allow' to call him by his name.

This book is well-structured and engaging, and provides an insight into five Sindhi family businesses. The Harilelas set out in retail and built their fortune in custom tailoring for American soldiers on R&R, turning Hong Kong into a popular global destination for mail-order suits. Merrimac Ventures, real estate giants and urban developers in the US, came about through the sheer bravery and brilliance of the indomitable Romila Motwani. Jet-setting Harish Fabiani grew to extraordinary wealth and fame using his native brilliance, and hobnobs with the likes of Donald Trump. The Lakhi Group is a diamond empire so professionally run and a family life so admirably simple and equal-opportunity that it shines forth in this narrative like a dazzling solitaire. And Jitendra ‘Jitu’ Virwani built his real-estate dominion brick by brick, racing ahead with giant leaps and battling all the way.Each of these extraordinary stories has elements of some of the characteristic Sindhi ways of doing business: difficult times bravely faced; fearless risk-taking and the ability to move with great swiftness when opportunity is sighted; intensely close and devoted family relationships; the role of women defined by family background (Sindhis are remarkably heterogeneous in this and a range of other important matters); the talent for shoring up against business cycles with real estate; and an impressively large commitment to philanthropy, sometimes vulgarly demanding attention, but often (in fact in more cases than can ever be known) completely anonymous. However, the book also has disturbingly anachronistic statements like “the Fabiani family has its roots in Pakistan.” (Roots, really? But Pakistan only came into existence in 1947 and that was when the Sindhis were rudely evicted!) Sindh has an ancient tradition of trade and mobility and its own range of rich products. Marco Polo wrote of the curiosities of Chin and Machin, and ‘the beautiful products of Hind and Sindh, laden on large ships which sail like mountains with the wings of the wind on the surface of the water.’ In the 1860s, a group of young men set out on the British steamship routes and ventured into trade in ports around the world. The retail chains of these early capitalists, M Dialdas, JT Chanrai, KAJ Chotirmal and others, formed the first Sindhi multinational companies. Inland, the money lenders of Shikarpur had extended their services into a phenomenally secure and sophisticated banking system with bases in South India and a network of agents on the trade routes extending from Central Asia into Russia, China and Japan. After Partition, many of the Sindhis forced out of their ancestral homeland with nothing, took to trading as a dignified means of earning an honest living in the places where they settled. Working on low margins, selling the packaging for an extra buck, they interfered with the profits of long-established trade cartels, for which they were resented and bitterly derided as ‘cheats’. Most of them had not been to Harvard Business School but they understood that the key to business success is to directly address the customers’ need, and they rebuilt their fortunes by doing precisely that: in garments, construction, education, and in time in every other industry. Partition also swelled the global outposts into communities and there are Sindhi shopkeepers in ports around the world. Many of the 'shopkeepers' grew their businesses with enterprise (and real estate) and are billionaires just as much as the five profiled in Paiso. Many of them retain links with each other, the remarkable phenomenon of a community which lost its roots when evicted from its homeland by Partition – but retains its connection in strong links which encircle the globe. There are Sindhi shops across the length and breadth of India too: Coonoor market, so remote in geography and culture, had a Quetta Stores when I was a child. So the phenomenon of Sindhi business is by no means restricted to glamorous billionaires.Similarly, it is true that traditional Sindhi business families considered education “a waste of time” and that this is by no means the case today. What is less known is that a huge population of Sindhis did hold education to be extremely important. These include the entrepreneurs coming from three and four generations of education who established the Indian multinational companies Onida (Mirchandanis) and Blue Star (Advanis); the global retail giant Landmark Group (Jagtianis); and in the case of Inlaks (Shivdasanis), three generations of Oxbridge education. The Ador Group, another multinational conglomerate, continues with the third and fourth generation of university educated partners who started their business in Sindh 110 years ago. As for Dr NP Tolani of the highly reputed Tolani Shipping, he earned his PhD in 22 months – still a record at Cornell – and returned to Bombay in 1964, intent on taking up a business in which there was as little corruption as possible in India.There are many more and most, despite strong bonds to their community and their families, and linked by the complex unspoken trauma of Partition, prefer to remain low profile and never flaunt their Sindhiness, perhaps to avoid being tarred with that ‘loud and vulgar’ brush that haunts the Sindhis, doomed as they seem to be to be represented by their flamboyant, attention-seeking brethren. Perhaps this book will help bring them out of the closet.I wrote the above review for Hindustan Times and it was carried today. You can read it in the newspaper online here but without the line highlighted above which I have just added. It is interesting to see that HT illustrated this review with a photo of Harish Fabiani, one of the billionaires featured in this book, and his wife – who, according to Paiso, he doesn't 'allow' to call him by his name.This review was written for Hindustan Times and appeared on Saturday 24 Feb 2018.

Published on February 23, 2018 20:12

February 9, 2018

Reaching for the Sky by Urvashi Sahni

The best book I read in 2017The most important thing I learnt from this book is that women’s education is essential not so much to make India a great country, but to empower a girl to live a fulfilling life, experiencing herself as an autonomous person deserving respect and equal rights.

Reaching for the Sky is the documented history of Prerna, a school in Lucknow, written by its founder. Established in 2003, Prerna’s students are underprivileged girls and part of the book is their story, with their photos and in their voices, and it shows how a school can change a girl’s life. These six girls were among the first to join Prerna, and have articulated their experiences objectively. They are girls who come from homes so poor that some were cleaning others’ homes along with their mothers at age seven. One had a brother who drowned in a pond at the construction site where their mother was working. Some had been forced into sexual intercourse by their own fathers. These and other Prerna girls belong to that enormous population of Indian women whose fathers and husbands exercise almost absolute control over their minds and bodies. So Prerna’s educational goals, Urvashi Sahni writes, in addition to imparting the government-mandated syllabus, include guiding a girl to recognize herself as an equal person and emerge with a sense of control over her life and aspirations for her future, with the confidence and skills to realize them.

One of the instruments described is critical dialogue, a conversation in which a girl describes her life situations and begins the process of understanding the social and political structures that restrict her, empowering herself to deal with them. Another is the use of drama through which a girl may immerse herself in role-model characters learning, for example, to speak loudly, walk tall and hold a steady gaze – things her real-life contexts have taught her not to do.

It turns out that Dr Sahni is an entrepreneur like her father, SP Malhotra of Weikfield, with a group of entities, one funding the other. Her first school, Study Hall Educational Foundation (1986), supported Prerna for its first four years. In 2008 she established DiDi’s, a social enterprise to provide livelihood to mothers, its profits diverted to support the education of their daughters in Prerna.

The part of the book that moved me most was Urvashi’s own story: a brave and gracious exposé of her own gradual liberation from strongly patriarchal, if privileged, situations. A family tragedy propelled her into social work, and her higher education at Berkeley University imbibed in her the value that the teacher-student relationship must be one of mutual respect, response, acceptance, empathetic understanding and care.

This review was written for Hindustan Times and appeared on Saturday 13 May 2017. It can be viewed online here

Published on February 09, 2018 23:24

November 30, 2017

Behind Bars by Sunetra Choudhury

Criminal justice in India: perversion, sleaze and corruption