Jeremy Butterfield's Blog, page 16

September 21, 2018

Is it “one and the same” or “one in the same”?

Lesedauer: 4 min

[image error]

Microsecond summary

“One in the same” will generally be considered wrong. No dictionary recognizes it. You should avoid it and use the standard form of “one and the same.”

Apart from shoring up my prejudices (a function it performs I suspect for so many people) Twitter occasionally lobs a new (to me) eggcorn my way.

One it flung at me recently is “one in the same”.

It should be “one and the same”.

What does “one and the same” mean?

As the Collins Cobuild dictionary helpfully defines it, “When two or more people or things are thought to be separate and you say that they are one and the same, you mean that they are in fact one single person or thing.”

You use it mostly, but not exclusively, as the complement of to be, in the latter’s various forms, as these examples suggest.

Luckily, Nancy’s father and her attorney were one and the same person.

I’m willing to work for the party because its interests and my interests are one and the same.

I grew up equating sex with love, believing them to be one and the same.

As you can see, the phrase can either be used on its own or with a following noun (person, 1st e.g. above.)

The nouns people most often use with it, other than person, are time and thing, but, as the last two examples below show, you can use it with any noun appropriate to your meaning.

They [sc. beaver dams] are at one and the same time parts of beaver societies and parts of beaver nature.

…that is to say, that sexuality and gender are not one and the same thing, and their complex interaction not only varies from one society to the next but also within a given culture.

It is possible that different paradigms introduce different ways of classifying one and the same set of objects.

The imagination must carry me out of myself into the feelings of others by one and the same process by which I am thrown forward as it were into my future being.

Hazlitt, Essay on the Principle of Human Action, i, 1–2.

Who uses it? Why do people get it wrong?

It crops up most frequently in formal or technical prose in the areas of the Arts and Humanities and Religion and Law. That means it is not common in general writing or speech, which helps explain why people convert it to “one in the same”.

And the speech mechanism of that conversion is not far to seek: in speaking, the phrase will be pronounced “one ’n’ the same”, and people who have never come across it in writing will interpret that ‘n’ as ‘in’.

Does “one in the same” make any sense?

Merriam-Webster online suggests that it doesn’t and argues that it would have to refer to a Russian doll-type arrangement.

I’m not so sure.

At the back of my mind, for that use of “in” I hear an echo of religious, specifically Christian, specifically Trinitarian, usage, i.e. God the three in one, but perhaps that’s just me.

(Can someone hear things at the back of their mind? Only asking. Ed.)

On a more mundane level, it must, surely, be influenced by advertising phrases highlighting the benefits of a product, such as being a “2-in-1 laptop and tablet”.

Other than that, I can’t fathom what it means to people who use it. I’d have to ask them.

It has been argued that it makes sense if you think of one thing being inside a clone of itself. In the case of people, though, that explanation could suggest (auto)cannibalism. Eeek!

Surprisingly, though, it is used in the same sort of circles that use the correct form, judging by the examples in the eggcorn database, e.g. Any time you visit our service desks, you will have the agreeable impression that helping the library and staying young are one in the same.

(UC Berkeley, Annual Report of the Libraries, Fall 2001).

The Merriam-Webster usage note also cites examples from publications which one can’t help feeling ought to have editors who know better, e.g.

a politician whose public and private persona seem to be one in the same.

— Newsweek, 8 Sept. 2017

Where does “one and the same” come from?

It is a calque, or translation of the Latin unus et idem, meaning, erm, “one and the same”, recorded as being used by Cicero and Horace.1 Piquantly, its first citation in the OED is from a translation from Latin, possibly by Cranmer, of Edward Fox and others’ treatise about the legitimacy of Henry VIII’s marriage to his brother’s wife (Catherine of Aragon) titled The determinations of the moste famous and mooste excellent vniuersities of Italy and Fraunce, that it is so vnlefull [sic] for a man to marie his brothers wyfe, that the pope hath no power to dispence therewith.

One and the same selfe man may be bothe a preest and a maryed man.

The phrase occurs 451 times in the OED, which gives some indication of its embeddedness in English.

How often do people muck it up?

That depends on where you look. In a corpus of academic journals (as one might hope but not necessarily expect these days) the dunderhead version is vanishingly small, 7 vs. 1994 (i.e. less than 0.5 per cent). In a general corpus (OEC, 2014) the proportions change to 192 vs. 3,183 (i.e. 6 per cent). And in a more recent corpus, 750ish vs. 4,283 (i.e. 17.5 per cent).

A few people are even using it slightly differently, in comparisons to mean “exactly the same as”:

Fructose is the sugar that’s prevalent in fruits, and it’s one in the same as cane sugar, which is simply much more concentrated.

And then there’s the song by Selena Gomez and Demi Lovato (whoever they might be; I only found it by googling). They spell it correctly, but then others misspell it.

As M-W poignantly pleads “Please try to avoid misinterpreting this venerable phrase.”

1 From Horace’s Epistles we have …ego, utrum Nave ferar magna an parva, ferar unus et idem.

I, whether I be carried in a large or a small boat, shall be carried as one and the same man.

Which, as the motto of the Royal Navy’s training establishment HMS Collingwood is sexed up and, at one and the same time, dumbed down to ferar unus et idem, “I shall carry on regardless”. A noble and uplifting sentiment, somewhat undermined by the existence of the film Carry On Regardless.

September 13, 2018

Calling out calling out. It’s time we stopped inciting people to call others out.

Lesedauer: 3.5 mins

I’ve long harboured a nagging doubt about the widespread, and growing, use of the word – beg your pardon, phrasal verb –, call out. Like all bad things (junk food, Trump, overuse of like), it comes from across the sea, like a linguistic bubonic plague.

[You are being “ironic”, aren’t you? Just checking. Ed.]

It has perplexed me for quite a while for several reasons. First, it seemed to be usurping the role of gentler and more nuanced criticisms, such as, ahem, criticize, censure, deplore, and the like.

Second, it seemed to exemplify that remorseless trend to sex up yet literalize (or make more graphic, concrete, depending on your point of view) language, a trend that replaces, for example, available with out there (in one of that phrase’s meanings), while at the same time spraying a layer of beguiling imprecision around the word, like dry ice.

Most importantly, it also struck me as the language of the playground: if I don’t like what you say/who you are/what you do, etc. I will call you out, and Yah, booh, sucks, take that, you nasty person! (Imagine an icon with a childish face and a big tongue sticking out. Or, better still, that uppity brat up at the top of this post.)

The phrasal verb in the sense of, as the OED defines it, “To expose or identify (a person) as acting in a dishonest or otherwise unacceptable manner; to challenge or confront [orig. and chiefly U.S.]” is first recorded from 1981, but now seems to be sweeping all in its path.

In that definition, “to challenge or confront” is the active ingredient. In increasingly confrontational encounters, aided and abetted it has to be said by Twitter, in our increasingly confrontational society, being exhorted to “call someone out” epitomizes the verbal fisticuffs culture in which we now seem to be trapped. If you call someone out, generally you are not “challenging” them to an intellectual duel, far less to a civilized Socratic dialogue. Basically, you are slagging them off.

The reasons for my distaste finally crystallized yesterday when I came across a tweet “protesting” against the killing of grizzly bears. (The background is the recent approval by the Wyoming Wildlife Commission of the first bear hunt in decades.) I can’t find the tweet, but no matter. Let’s pretend this is radio: I’ll describe the scene.

One tweeter (person 1) had posted a picture of himself, possibly self-satisifiedly, above the corpse of a grizzly. Another tweeter (person 2), ostensibly for an enlightened motive, had retweeted that picture and called on people to “call out” the perpetrator, pointing out that it was hardly a fair fight between an unarmed bear and an automatic rifle.

“Yeah, right, let’s get the b*****d” might be everyone’s gut reaction. Surely only a despicable moron would do such a shocking thing as kill one of Nature’s most magnificent creatures (and he deserves to be kicked where it really hurts).

Or perhaps not.

Let’s reconsider. For a start, we don’t know from the tweet all the reasons why person 1 killed the bear, do we?

But even if we did, and it was just for sport, does that justify us in hounding him? For that is what “calling out” someone in this particular case amounts to. Naming and shaming, hounding, harassing are other ways of putting it. It is an implicit incitement to violence, though probably only to verbal, not deadly violence. All the same, it is disingenuous, to say the least, if not downright hypocritical.

Just to make one objection, how can we possibly predict what the consequences of “calling” this person “out” might be?

To take an extreme scenario, an animal rights nutter might track him down and shoot him, or burn his house down, or kidnap his children, or who knows what.

And even if nothing so dire happened, the call-out-ee might still feel belittled, humiliated, ridiculed, and so forth.

Would achieving that be a morally justifiable result? I’m far from convinced.

[image error]

‘Ok…I’ll admit they’re kind of cute, but I still say their herds need to be thinned.’

Meanwhile, person 2 (who as far as I recall was a biologist) has the almost erotic satisfaction of feeling morally superior and of having done the “right thing.” But in my view, all they have done is appeal to a sort of moralistic herd instinct or even mob rule, the sort of virtue-signalling sides-taking encouraged by Twitter that has largely poisoned public discourse in the political sphere and turned debate into a Manichean struggle to the death — mostly figurative, but just very occasionally literal.

Would “calling out” bring the bear back to life?

No.

Would it stop others killing bears?

No.

It might even achieve the opposite and harden the riflemen in their determination to shoot grizzlies.

(In any case, there is a set number of shootings allowed.)

The issue has been discussed, different viewpoints have been presented, and a decision has been taken.

As with any decision, some people dislike it and disagree with it.

The exhortation to “call out” is the online version of the rotten tomato/egg thrown at a politician.

It achieves nothing except to inflame the thrower’s moral narcissism and self-regard while belittling and humiliating the opponent.

Yet, being online, it is ultimately more effective, more horribly pernicious and divisive. Stop it, please. Just stop it.

August 21, 2018

On the spur of the moment. Or in the spur of the moment? An idiom in motion?

Lesedauer: 6 m

I don’t usually do things on the spur of the moment.

Do you?

Life’s generally too complicated and busy to allow for spontaneity. Things have to be planned. (If you go by Myers-Briggs], I’m a tight-arsed ‘J’, not a go-with-the-flow ‘P’. Though some might say I’m half-arsed…)

But, even less do I do them in the spur of the moment.

But, here’s the thing: writing this blog was an almost ‘spur-of-the-moment’ decision. I was only prompted to write it last night, Friday, and here I am writing it on a Saturday (and forward-posting it for a Tuesday). Why I’m writing it at all will soon become clear.

In?!?! the spur of the moment

The idiom is engraved on my brain since who knows when as ‘on the spur of the moment’. So you could have knocked me down with a feather (1853) when an amiable and puppishly enthusiastic BBC music presenter came out with ‘in the spur of the moment’ in a Proms interview. Shurely shome mishtake, I thought.

Well, yes and no. ‘Yes’, because it is not the canonical, dictionary-guaranteed preposition, and prepositions in idioms tend to be ‘set in stone’ at any given point in time. But ‘no’, because it is not a one-off or a tlip of the songue.

For example, if you google “in the spur of the moment” with quotation marks, you get ‘about 20,400’ results.

Among them you discover that there is a 2000 jazz album called ‘In the Spur of the Moment,’ which suggests that that form of the phrase was already well established by the millennium.

You will also find a discussion on the useful WordReference Forums going back to 2005; in discussing a different phrase, several posters take ‘in the spur of the moment’ for granted, while another says he uses ‘at’ ‘…but I don’t think it really matters. In, at, on, the meaning is there with all of them’.

(Clearly a Myers-Briggs ‘P’. One wonders if he is similarly cavalier about spelling.)

In contrast, googling “on the spur of the moment” retrieves about 1,210,000 hits.

If you look at iWEB, the carefully structured 14-billion-word BYU corpus, you find 228 for ‘in the spur of the moment’ but 1662 for ‘on the spur of the moment’, an 88/12 per cent split. The NOW corpus (6 billion words from news sites) shows 122 ‘in’ from all round the anglosphere, and 826 for ‘on’, a spookily similar 87/13 per cent split.

Why the change?

This is purely guesswork. First, at least for me, the metaphor is not entirely dead. Therefore, ‘on’ makes sense, given that in the background there is a physical spur involved, which something can be on, but not in. However, I (possibly rashly) presume for many in the ‘in’ crowd the metaphor is dead and buried. Certainly, for those online who ask what it means, it must be long under ground.

And if the metaphor is dead, then analogy plays its part, the analogy I am thinking of being ‘in the heat of the moment’.

In other words, you get a blidiom (blend idiom) of on the spur of/in the heat of + the moment.

This is then perhaps reinforced by the highly frequent use of ‘in’ in other time-related phrases, e.g. in the nick of time; in five minutes/an hour/a day, etc.; in the morning/afternoon, etc.; in 1885; in the twentieth etc. century; in recent days/weeks/years; in the last/next few days.

I won’t go on; you get the picture.

If my hunch is correct, the frequency of ‘in’ overrides any parallelism with phrases such as ‘on impulse’, ‘on a whim’, in which ‘on’ is used to mean something like, as the OED puts it, ‘Indicating the basis or reason of an action, opinion, etc.; having as a motive’.

What strikes me as unusual is the prepositional shift in an idiom. However, if historical ‘all on a sudden’ can become ‘all of a sudden’, why shouldn’t ‘on the spur…’ become ‘in the spur…’?

For the moment, though, the editors I’ve asked would definitely change ‘in’ to ‘on’.

What follows delves into the history of the phrase, courtesy of the OED.

On the spur of the moment

What does it mean?

As Cobuild neatly defines it, ‘if you do something on the spur of the moment, you do it suddenly, without planning it beforehand’.

That gets the two elements of suddenness and absence of planning.

The example is They admitted they had taken a vehicle on the spur of the moment.

Which sounds about right for the mindset of joyriders.

Why ‘spur’ of the moment’?

These days I suspect lots of people ‘out there’ (note to self: a blog about ‘out there’ is overdue) don’t know what a spur is. (I’m sure you’re not one of them, gentle reader.) Or if they do, they think it’s something to do with football, Spurs being the nickname of the English football team Tottenham Hotspur.

For the enlightenment of such, a spur is:

A device for pricking the side of a horse in order to urge it forward, consisting of a small spike or spiked wheel attached to the rider’s heel.

Self-evidently, such a barbaric piece of equipment has no place in our enlightened age, but, in days of old, when knights were bold… (complete ad libitum), great store was set on having rather spectacular ones. And even later, for example, Argentine gauchos wore them.

Here’s a rather fancy set of gaucho spurs.

And further down, there’s a picture showing a rather foppish St George sporting a spectacular pair… of spurs, that is.

The word spur goes back to Old English: the OED’s ‘origin’ rubric describes it as ‘a word inherited from Germanic’, which almost makes it sound as if we should somehow treasure it, like great-grandmama’s locket.

From medieval times it seemed ripe for metaphorical use. First, as the OED puts it, ‘In various prepositional or elliptical phrases denoting speed, haste, eagerness, etc.’

Chaucer used it thus in c1374:

Tristith wele that I Wole be her champioun with spore and yerd.

(Trust well, I will be to her champion with whip and with spur)

Troilus & Criseyde ii. 1427

And the Bard also: You haue made shift to run into’t, bootes and spurres and all.

a1616, All’s Well that ends Well (1623) ii. v. 36

On the spur

The next development was, as defined by the OED, into a semi-fixed phrase:

‘on (also upon) the (†spurs or) spur (also †upon spur), at full speed, in or with the utmost haste, in literal or figurative use.’

First recorded in Berners/Froissart:

Whan we be in the feldes, lette vs ryde on the spurres to Gaunte.

1525, Cronycles II. viii. 18

But used as late as Tennyson:

And there, All wild to found an University For maidens, on the spur she fled.

1847, Princess i. 19

This use is not marked with the funereal obelus (†) to show that it is obsolete, but surely it is (the OED entry dates to 1915).

In addition, spur on its own came to be used from the sixteenth century onwards to mean ‘incentive, stimulus, incitement’:

I professe to be but..a spurre or a whet stone, to sharpe the pennes of some other.

1551, T. Wilson Rule of Reason sig. Aiiijv

Praise and honour are spurres to virtue.

a1593, H. Smith Serm. (1637) 585

[image error]

Pisanello, Apparition of the Virgin to Sts Antony and George, 1445, National Gallery, London. Detail.

On the spur of the moment

It was not until the nineteenth century that on the spur of the moment arose:

Volunteers, with a party of the Surrey cavalry, attended and prevented the populace in general from taking that step, which, perhaps, the best feelings of human nature had, upon the spur of the moment dictated.

1801 Ann. Reg. 1799 (Otridge ed.) ii. Chron. 27/1

But even then it was not ‘set in stone.’ The preposition could be upon (ok, it’s ‘the same as’ on, only more formal), and the second noun could be occasion:

He carried me home on the spur of the occasion.

1809, B. H. Malkin tr. A. R. Le Sage Adventures Gil Blas I. ii. iii. 194

And Carlyle took it even further:

The Church..has been consecrated, by supreme decree, on the spur of this time, into a Pantheon.

1837 T. Carlyle French Revol. II. iii. vii. 199

The first attributive use of the phrase came in the mid-twentieth century:

Toppy is tops at spur-of-the-moment tactics.

1948, C. Day Lewis Otterbury Incident viii. 94

Google Ngrams suggests how the form with occasion has fallen out of fashion; the batch of citations seemingly dated 1883-2000 are from antique works, e.g. Jeremy Bentham.

In all of them, however, the preposition is ‘on’. The Hansard Corpus and the Corpus of Historical American English show the same.

July 18, 2018

Underhand or underhanded methods? Another U.S./Brit divergence.

[image error]

Summary

In the U.S., for the meaning ‘marked by secrecy or dishonesty’ underhanded is by far commoner than underhand.

Underhand is also used in the U.S. with that meaning, but only rarely. Much more often it has a physical meaning.

In the UK, underhand is much more often used to convey that ‘dishonest’ meaning, but underhanded is also an option.

Underhanded or underhand?

I’ve been reviewing someone else’s translation from Spanish of a major Latin American classic. That puts me in the luxuriously smug position of avoiding the donkey work and hard grind yet being able to point out and wag the finger that the translator has, for example, taken an idiom quite literally, word for word, and come up with nonsense.

Having now found so many such schoolboy howlers, I examine every word against the original Spanish with hawk-like severity.

So it was that when I came across the phrase ‘underhanded methods’, I paused.

‘Shurely shome mishtake’, I thought, to use that old Private Eye chestnut. You’ve got carried away again, dear (American) translator. The word is underhand.

Except it’s not…if you’re American, as I was soon to discover.

In fact, if you’re American, underhand will probably sound daft and underhanded normal, and vice versa, if you’re British.

What say the dictionaries?

Go to Merriam-Webster online, look up underhanded as an adjective, and you will find it rather beautifully defined as ‘marked by secrecy, chicanery, and deception: not honest and aboveboard’ (pedants, please note that U.S. spelling of above board as a solid [a term that sounds vaguely lavatorial; I digress]).

Go to underhand (adj.) in the same dictionary, and you will find it given three meanings: 1. = underhanded, 2. done so as to evade notice, and 3. made with the hand brought forward and up from below the shoulder level.

e.g. an underhand serve.

(Quite why underhanded does not share meaning 2., I won’t investigate.)

The above two M-W entries reflect U.S. usage rather accurately. Underhand can be used to mean ‘not honest’, as in underhand methods, but very much more often it is used, as the Oxford English Corpus (OEC) shows, to mean ‘underarm’.

Similarly, if you go to Oxford Online, the U.S. version, and look for underhand, the first meaning given is the ‘(Of a throw or stroke in sports) made with the arm or hand below shoulder level’ one, and the ‘dishonest’ meaning is given only third. The second meaning is ‘With the palm of the hand upward or outward’ as in underhand grip.

Underhanded is defined along the same lines as M-W: ‘Acting or done in a secret or dishonest way’.

If you go to the Oxford Online UK version, it clearly reflects this Atlantic divide: the first meaning for underhand is the ‘dishonest’ one, and the second meaning is a (less frequent) synonym in British English for underarm. If you go to underhanded you get the message ‘another form of underhand.’

‘The science bit’

Dictionaries seem to have got the measure of these differences.

In confirmation of what they say, in the OEC (Feb. 2014) underhand as adjective appears nearly one thousand (977) times, of which 500 are British English and a mere 137 U.S. English. Of those 500 British ones, all but a handful are to do with ‘dishonesty’. Of those 137 U.S. ones, hardly any are to do with ‘dishonesty’, and the most frequent phrase is underhand grip.

Similarly, the Brigham Young University Corpus of Contemporary American shows, for example, underhanded tactics 22 times, but underhand tactics never, whereas underhand grip appears 34 times.

Finally, the Hansard Corpus – of British English, obviously – with data from 1803 to 2006, has underhanded 68 times but underhand 1216 times. So underhanded is a possibility, but not a common one, e.g. from 2002,

the Trade Union side wished to record its dissent over the deceitful and underhanded way in which this issue has been handled.

(This is by a Scottish MP, which may or may not have a bearing.)

The history bit

Underhand as an adverb goes back to Old English (c. AD 1000) in a now obsolete meaning.

The adjective came later, 1545, in the physical meaning, in this case, relating to archery, and 1592 in the meaning ‘secret, clandestine, surreptitious’. The meaning of ‘not straightforward’, which is an integral part of its modern meaning, did not appear until 1842, in Cardinal Newman’s letters:

1842 J. H. Newman Lett. & Corr. (1891) II. 393

I am often accused of being underhand and uncandid.

Underhanded as adverb makes its appearance in 1822/23, in two different meanings, but the adjective first appears in Dickens, according to the OED, in the meaning ‘surreptitious’ in Bleak House (1853): xxxvii. 370

Under-handed charges against John Jarndyce.

and in the meaning ‘not straightforward’ in Our Mutual Friend (1865) I. ii. vii. 232

That’s an under-handed mind, sir.

[image error]

Lady Dedlock, Esther Summerson and ‘Charley’ (Charlotte) in the wood. Phiz’s illustration from Bleak House.

June 19, 2018

Twitter never fails to disappoint. Or should that be ‘never disappoints’?

While reading something online the other day I came across the phrase Twitter never fails to disappoint. The context made it clear that the meaning intended was ‘Twitter never disappoints’. This is the exact opposite of the logical reading that ‘Twitter always disappoints.’

That example reminded me of one from years ago. A tourist brochure for a seaside resort promised something along the lines of ‘A visit to X-on-Sea never fails to disappoint.’

And then, slap my thigh, today, when I was checking out restaurants for my partner’s birthday, what did I come across but this glowing recommendation: I’ve been going to X Bistro in Y since it opened, which was not yesterday, and I can safely say that their food has never failed to disappoint?

(Which shows that the phrase is not a completely frozen idiom, because it allows past tense.)

What is going on that makes a structure mean the opposite of what the speaker intended? And how do other speakers manage to extract the correct meaning? The discussion on the English StackExchange site shows that the phrase can certainly cause confusion.

Multiple negations cause problems

It’s all to do with the number of negations, and how the human brain goes into meltdown when trying to process too many. Having two negations might be the limit to easy intelligibility.

Such negations can be explicit (not, no, nobody, never, etc.) or they can be implicit (fail, ignore, avoid, etc.). If we analyse our phrase in terms of negation, we’ll find three:

• to fail to do something is not to do it = negation1 (explicit)

• never adds negation2 (explicit)

• disappoint adds negation3 (implicit)

(Disappoint is implicitly negative since it means ‘not to live up to expectations’.)

Logically, to never fail to do something means ‘to always do’ it. ‘Twitter never fails to disappoint’ therefore means ‘Twitter always disappoints.’

But the example which caught my eye was intended to mean the exact opposite. It reads like a conflation of ‘never fails to please’ or some appropriate positive verb, and ‘never disappoints’.

[image error]

Notice how the reply at the top uses the logical meaning to rebut the positive but mistaken one under the image of the woman eating.

Not a unique case

Twitter never fails to disappoint is hardly a unique case of a phrase meaning the opposite of what the speaker intends. Another well-known and well-embedded example is the ‘It is impossible/difficult/hard to underestimate’ structure, where, logically, overestimate is meant, e.g. ‘It would be impossible to underestimate its [sc. Ulysses’] influence; the novel was never quite the same again.’ The logical meaning is ‘its influence cannot be overestimated’ i.e. exaggerated.

But there we only have two negatives rather than three: one explicit – impossible – and one implicit negative in overestimate, because to overestimate is to produce an incorrect estimate.

But let’s get back to never fail to do.

never + fail + to what?

In theory, in the sense of always doing it, you could never fail to do practically anything, for example, I never fail to eat Marmite at breakfast.

However, our old friend collocation kicks in strongly here. The string never + FAIL [sloped capitals mean ‘in all forms’] + to-infinitive very often goes with events and emotions that can be classified broadly as either positive (entertain, amuse, please, delight, inspire, etc.) or intense (impress, amaze, surprise, etc.), or a mixture of the two.

Even an apparently neutral verb such as make goes with positive verbs, e.g. MAKE + me/us/people, etc. + laugh/smile/giggle/chuckle (though whether that is, in any case, a feature of make, rather than of the entire phrase, is impossible to tell).

‘You’ve got to ac-cent-tchu-ate the positive…’

In fact, the top five collocations by frequency of never + FAIL + to-inf are (in my corpus, OEC Monitor Corpus April 2018) impress, amaze, make, deliver, disappoint.

If, as I have suggested above, the overall ‘profile’ of never fail to is positive, then speakers view never fail to disappoint as positive, despite its meaning the opposite. They take the whole as a ready-made, rather than analysing its meaning.

Moreover, it is possibly one of those phrases where the presence/absence of a negative makes little difference to the meaning. As Language Log pointed out, fail to miss behaves like that: the meaning is the same whether you say miss or fail to miss. Similarly, whether you say never DISAPPOINT or never FAIL to disappoint, the meaning is the same.

The corpus I consulted contains 226 examples of never FAIL to disappoint. In a random sample of 50, 45 showed the illogical meaning (= ‘never DISAPPOINT’)

We were rewarded with our choice of route as the New Zealand scenery never fails to disappoint. (= ‘never disappoints’)

If I’m going to drop $20 on a couple of made-to-order burgers, fries and a soda, there are a few Portillo’s close to here which are similarly priced but never fail to disappoint (= ‘never disappoint’) …The staff here is on point. Honestly, they can’t do enough for you.

A mere five (10%) exemplified the logical surface reading, meaning ‘always succeed in disappointing’.

For example, in this about the chronically inept Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS):

Lord Oakeshott, a leading LibDem peer, said: ‘RBS never fails to disappoint. Taxpayers poured £45 billion but it is a zombie bank, shrinking instead of lending.’

Similarly, this investigator of financial shenanigans:

My investigations often lead me into contact with British law enforcement and regulators and they never fail to disappoint me by their incompetence and lack of professionalism.

All in all, then, it would seem that the apparently negative ‘never FAIL to disappoint’ is well established as meaning the opposite of what it seems to mean, and as positive in intent.

We interpret it as positive, I submit, because a) we are now well used to a range of constructions that mean the opposite of what they are intended to mean and b) multiple negatives cannot be processed and, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, lead to a positive or affirmative interpretation.

It could also be significant that the opposite – always FAIL to – does not collocate with the same verbs as never FAIL to. There is a solitary example of always FAIL to disappoint:

The beauty of Smashing Pumpkins is that every album is drastically different from each other. I’m eager for this release, Billy Corgan has always failed to disappoint me.

This general phenomenon of muddled negation is described by Language Log as ‘misnegation’ or ‘overnegation.’ Here is a link to a very long list of examples.

And here is an utterly mind-boggling example, courtesy of LL:

These contrasts don’t mean that Bush was without blemish: As Meacham notes, there were political misjudgments and calculated concessions to ambition on the long path to power. Nor does it mean that Trump doesn’t lack his own kind of strengths, not the least of which is his loudly declared indifference to elite opinion.

The fact is, we are able to interpret these car-crash negatives correctly and extract the meaning the speaker intended.

As humble proof of that, I stared at this oft-cited canonical example for ages before I realised what was wrong: ‘No head injury is too trivial to ignore.’ Like you, gentle reader, I understood what it meant without needing to analyse it, but it should, obviously – D’oh! – on reflection, be rephrased as ‘No matter how trivial your head injury seems, we will not ignore it’ or ‘No head injury is too trivial to be attended to.’ Again, it’s a case of that triple negation; no head injury1; is too trivial to X2 (= ‘is so trivial that it will not be Xed)’; be ignored3 (negative = ‘will not be attended to’).

Watch out for this kind of phrase. There are never too many of them not to fail to ignore.

June 5, 2018

The aardvark. First word in the dictionary? Or urban myth?

3-minute read

As this is my most often-visited blog page, I thought I’d re-issue it. It’s short and it doesn’t need updating. But the fascination this animal exerts on people’s minds seems universal and never-ending.

Everyone knows the word, but how many have ever seen the animal? The definition

medium-sized, nocturnal African mammal, Orycteropus afer, which has sparse hair, long ears, an elongated snout, strong burrowing limbs, and a thick tail, feeding solely on ants and termites

does not make the beast sound immediately prepossessing, yet some people find this Cyrano de Bergerac of the animal kingdom cute. (The wording of that Oxford English Dictionary definition could also suggest, somewhat surreally, that it is the critter’s tail which feeds solely on ants and termites).

The aardvark is not mythical, like the phoenix, since it really exists, but it has its own urban myth. Ask anyone which word comes first in an English dictionary, and they will assuredly answer “aardvark“. But it generally is not the first word in “the dictionary”.

And the first word in an English dictionary is…

That honour usually goes to the letter A, as in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). You might think a simple letter would be child’s play to define. In fact, the OED divides it into no fewer than 33 senses, including everyday meanings such as the musical note, and more technical ones such as A denoting a socio-economic grouping and A for Ångström.

Dozens of abbreviations follow before the next entry, the humble but indispensable indefinite article (aka “general determiner”) a. It is followed by numerous entries for a in different guises, such as in Bob Dylan’s “The times they are a-changin“, as a prefix (asexual), and as a Latin or Greek suffix (idea, data).

Finally, we strike gold with the first truly lexical entry. And it is? (A very muffled drumroll for) aa, meaning a stream or watercourse, last spotted in 1430 and marked as not only obsolete but rare. Several more curiosities, including some that may be useful for Scrabblists, intervene (aal, from Hindi, the Indian mulberry tree, aapa, from Urdu, meaning older sister) before we get back to our ant-eating, ground-digging mammal with its thirty-centimetre-long tongue.

If you’re enjoying this blog and finding it useful, why not get an alert every time I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging about issues of English usage, word histories, writing tips, and, occasionally, other languages. Enjoy!

Why “aardvark”?

South African Dutch, which became Afrikaans, is the language from which English borrowed aardvark, originally written as aardvarken. The aard- part is the Dutch word aarde, which means “earth” and comes from the same Germanic stock as the English word. (The connection between the two is easier to see in the medieval Dutch form of the word, which was ertha.) The -varken part means “pig”. And the animal is also called earth-hog and earth-pig in a loan translation.

Another sign of how English and Afrikaans are ultimately related can be seen in the word Apartheid. It meant literally “apart-ness”, and the -heid element matches the -hood of childhood, priesthood, and other “-hoods“.

Other Afrikaans words in World English

[image error]Afrikaans is an offshoot of Dutch, and is one of the most widely spoken of South Africa’s eleven official languages. Its gifts to World English include trek as a noun and verb, and commandeer. Commandeer is multiply borrowed, a bit like a parent’s car, in that it was borrowed from Afrikaans kommandeer, which borrowed it from Dutch commanderen, which borrowed it from French commander. Phew!

It rose to prominence in British English during the First Boer War of 1880-1881. It was originally used to mean “to force into military service”, as The Times reported on 5 February 1881:

The night previously the Boers had commandeered the natives…and compelled them to fight.

Its more metaphorical meaning of taking arbitrary possession of something came later:

The naïve claims put forward by the Boers to some special Providence—a process which a friendly German critic described as “commandeering the Almighty”.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, 1900.

Rather more colourful is scoff, the informal noun for food. It is from Afrikaans schoff, representing Dutch schoft “quarter of a day”, hence the four meals in a day. The OED’s first quotation comes from the 1846 Swell’s Night Guide; or, a peep through The Great Metropolis, a rather louche guide for the man about town in search of interesting nightlife, including casual sex (plus ça change):

It vas hout-and-hout good scoff, and no flies.

(The spelling is not a mistake. It presumably mimics the speaker’s accent.)

And a word which demands a wider airing is stompie, a cigarette butt, or a partially-smoked cigarette, especially one stubbed out and kept for relighting later, as in South African playwright Athol Fugard’s

The whiteman stopped the bulldozer and smoked a cigarette… He threw me the stompie.

May 24, 2018

Read this! It’s of upmost importance! Utmost, upmost, uppermost and collocation

A three-minute-and-a-second-or-two read

Please read. This is of uppermost importance

The other day I was editing a chapter written by a French/Flemish academic who is a non-mother tongue speaker of English. Apart from a few lurking French-English false friends, it read extremely well, given its (predictably) dry academic style. Then I came across ‘Researching…NOUN bla, bla, bla, rather than simply focusing upon its rhetorical representations is, therefore, of uppermost importance’.

of upmost importance

Tiens! thought I. (Well, I didn’t; I’m just being more than usually pretentious. Reading lots of academic writing in the Humanities can make you like that, you know. Be warned!)

When English speakers diverge from the collocation ‘(of) utmost importance’ they usually replace utmost with upmost. I hadn’t come across uppermost in that slot before.

But, I can easily see how, if none of the three words is part of your language, uppermost makes sense. It certainly seems to as regards meaning: ‘Highest in place, rank, or importance’ as the Online Oxford Dictionary defines it. And if you know the physical meaning (e.g. on the uppermost shelf), it is a mere hop, skip and jump to the metaphor.

It just so happens that uppermost does not generally associate or ‘collocate’ with importance.1

For example, in the Oxford Corpus of Academic English, Journals (June 2015, 1.67 billion words), a search for each of the three adjectives followed by importance retrieves this league table: utmost 1,765, upmost, 27, uppermost 4. Clearly, uppermost is a very distant ‘outrider’.2

The BYU Now Corpus (6 billion words) gives a similar result for the first two: utmost at 6,241 and upmost at 142, but uppermost is even rarer, with a single occurrence.

Could upmost be spreading?

I have long known about ‘upmost importance’; it’s something I must have noted long, long ago. Google Ngrams shows its steady rise since roughly 1930.

But I was a bit surprised to find that upmost limpets itself to other nouns as well.

Looking for example in the Oxford Monitor Corpus (February 2018, about 8 billion words), in addition to the well-ensconced upmost importance, I found upmost respect/integrity/professionalism/dignity:

I can only hope that today’s verdict goes some way to bringing closure to the victim’s family who have behaved with the upmost dignity throughout this very harrowing ordeal.

That is from the BBC News website, repeating, presumably, what someone said, so it might be a transcription glitch. Or it might not.

Those collocations do not appear in the Corpus of Academic English, Journals, which probably reflects the edited nature of the journals, compared to the content of the Monitor Corpus.

Is upmost wrong?

I’d say, rather, that it is, according to current collocational preferences, somewhat anomalous.

However, many people would consider it wrong tout court, that is, with no qualifications, and therefore an editor should probably change it, or, at the least raise the issue with the writer. I would.

Confusing upmost with utmost is hardly surprising given their sound and meaning similarity. It just so happens that the meaning, as the OED defines it, ‘That is of the greatest or highest degree; of the largest amount, number, etc.’ became, it seems, largely confined to utmost, rather than upmost or uppermost, from the early eighteenth century onwards.

However, the eggcorns database labels it as practically ‘mainstream’, while explaining its occurrence: ‘[The constituent “ut”] is liable to reanalysis to something that more transparently expresses superlative meaning, such as up+most (‘uppermost’), which fits with the MORE IS UP-type metaphor. This may also involve anticipatory assimilation to the nasal in “most”.’

Conclusion

Collocation is such a tricky part of language; it is what invariably distinguishes the ‘native’ speaker from second-language speakers (like our professor at the start) no matter how proficient they might be.

It is also often unpredictable. Why do you make a mistake rather than do one?

For example, if you repay a debt, it seems kind of obvious and logical that the words ‘go together’, that repay is the right word to go with debt, given the meaning of each.

But if you honour a debt, or a cheque, that is, to my mind a rather different order of language combination (though, admittedly, one that is shared by French, Italian, and German, but not Spanish). And you cannot dishonour a cheque.

Moreover, like everything in language, collocational conventions change over time.

Which gives me a pretext for one of my favourite quotes, from that granddaddy of linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure:

‘Le temps change toute chose : il n’y aucune raison pour que la langue échappe à cette loi universelle.’

Time changes all things; there is no reason why language should escape this universal law.

1 What it does, of course, often collocate with is mind and related words (e.g. As Europe seeks to increase pressure on Moscow over its seizure of the Crimea region from Ukraine, making Moscow pay an economic price is uppermost in leaders’ minds).

In its original, literal, physical meaning, uppermost often goes with layers, reaches, tiers, floors, and the like: Ms. Langley’s ascent represents a slight evolution in how women have navigated moviedom’s uppermost ranks.

2 Outrider – not to be confused with the popular series Outlander – is a modish cliché I’ve discovered is popular in Academe. It means something like an exception, a solitary or unorthodox case.

May 4, 2018

Well, I’ll be dashed. A blog about en dashes, en rules and POTUS.

(4-minute read, unless you happen to be Oscar Wilde, in which case, 10-second read.)

Events in U.S. politics seem to move so quickly now that the occurrence I’m going to mention already seems like ancient history.

But you may recall that on 9 April the FBI raided the offices and hotel room of President Trump’s personal attorney, Michael Cohen, to investigate the alleged links between Russia and el Trumpo’s campaign. Those were extremely Stormy days.

Outraged, the world’s most powerful comb-over tweeted that ‘Attorney–client privilege is dead.’

While some people were concerned with the constitutional-legal issues thereby raised [note the hyphen], we (editors) who ignore such trivia and concentrate on higher things were thrust into the eye of a Twitterstorm over POTUS’s use of what looked like an en rule or en dash.

Beg pardon?

That’s right. An en dash (or en rule as it is more often called in Britain) is distinct from your common or garden hyphen; it is longer than it, as you will be able to see in the examples below.

Where you are most likely to have seen en dashes bigly, probably without even noticing, is in ‘ranges’ of different kinds:

in the period 1939–45; We are open Monday–Saturday; Opening times 9.30–5.30

If you read bibliographies, you will also probably have seen en rules in page ranges, e.g. pp. 120–27.

In some publishing styles it is used for ‘parenthetical asides’, which is editor-speak for what normal humans might call ‘subsidiary comments set off from the surrounding text’.

Serendipitously, today I chanced upon this elegant sentence containing en dashes used exactly that way: ‘He belonged to that class of men – vaguely unprepossessing, often short, fat, bald, clever – who were unaccountably attractive to certain beautiful women’. (Ian McEwan, Solar, p.3)

If you want a definition, New Hart’s Rules defines an en rule somewhat circularly as follows: ‘The en rule (–) is longer than the hyphen and half the length of an em rule.’

Help!

The names are not just plucked out of thin air; they have a(n) historical printing basis. An en rule is so called because it would once have been the width of a letter n in traditional lead-type typography. Similarly, an em rule would be the width of a letter… (you fill it in, gentle reader, just to prove you have been paying attention).

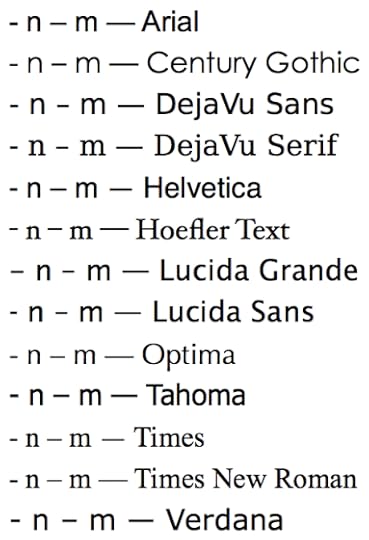

But please examine the chart below, going from left to right. For several common typefaces it shows first a hyphen, then a letter n, then an en rule, then an m, and then an m rule; it is glaringly obvious that the link between character width and length of rule has been broken.

Woteva. The fact is that if you want to produce an en or em rule in Word, you can get them effortlessly using the Alt-key. And there are other ways too.

(See at end for instructions.)

Yes, but what about attorney–client privilege?

The question mark hanging unmenacingly over the Twittersphere was whether that presidential en dash should have been a non-presidential hyphen.

Moreover, few could credit that the coiner of the deathless vocable covfefe and the global no. 1 abuser of majuscule (capital letters) could be so subtle as to use an en dash. Not to mention, that it can be hard to judge from Twitter what length an hyphen or dash is in any case.

IMHO, it was correctly an en rule.

New Hart’s Rules, for example saith:

‘The en rule is used closed up to express connection or relation between words; it means roughly to or and:

Dover–Calais crossing; Ali–Foreman match; editor–author relationship; Permian–Carboniferous boundary.’

The pertinent example for us is editor–author relationship. That en rule/dash linking the words perfectly encapsulates the connection between client and attorney as expressed by the Big Ginger.

In an endless thread reflecting on preposPOTUS’s original tweet, one wit opined that:

The en-dash can be used to establish range, such as in a range of pages in a book. Thus, Mr. Trump is making a metaphysical/moral claim here: The ties that bond “attorneys” to “clients” is a spectrum of intimacy, not a simplistic hyphenated ontological proximity.

Another quoted: ‘”The en dash connects things that are related to each other by distance,” Attorney and *distant* client?’

In support of the ‘relationship’ hypothesis, I submit Hart’s example of ‘a Greek-American family’ versus ‘Greek–American negotiations’. The first means a family of mixed heritage, the second negotiations between.

Can you use the en dash for anything else?

The Chicago Manual of Style, at least in its current edition, does not mention the ‘relationship’ angle that New Hart’s Rules does.

It does, however, suggest some extreme subtleties which I feel sure must be ‘more honoured in the breach than the observance’. It prefaces those with the slightly starchy: ‘Though the differences can sometimes be subtle—especially in the case of an en dash versus a hyphen—correct use of the different types [sc. of hyphen] is a sign of editorial precision and care.’

To indicate an unfinished range, e.g. Theresa May, British Prime Minister 2016–; Brexit negotiations 2017–

‘The en dash can be used in place of a hyphen in a compound adjective when one of its elements consists of an open compound…’ e.g. the post–World War II years; Chuck Berry–style lyrics.

(I’m not sure how Chuck Berry might feel about being an ‘open compound’.) But, as the Manual realistically acknowledges, ‘this editorial nicety will almost certainly go unnoticed by the majority of readers.’

As Hart’s points out, the en rule is also used for botanical, anatomical, etc. phenomena named after two people, e.g. Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (‘mad cow disease’), and for other non-scientific pairings, e.g. Marxism–Leninism.

Incidentally, AP and Chicago differ in styles, as shown in this chart.

OK, I am raring to use an en dash asap. How do I create one?

There is an exhaustive list here.

To keep things simple, and you on this page, here are three options.

a) Much the simplest, probably, is to use the Alt-key and the numeric keypad, if you have one:

Alt 45 –

Alt 0150 –

Alt 0151 —

But we all have different ways of working, so…

b) In Word, under ‘File’ go to ‘Options’ then ‘Proofing’. Under ‘Autocorrect options’ click on ‘Autoformat’ and make sure you tick the box under ‘Replace’ to replace two hyphens with a dash.

But beware. If you insert two hyphens between words and leave no space, Word will convert them into an em dash

But if you want a word to be followed by an en dash, type the word, then a space, then two hyphens, and – you should get an en dash.

This is the system I have always used, but it is, admittedly, cumbersome.

c) Unicode

hyphen = U2010

en dash = U2013

em dash = U2014

That’s it for now. Sorry, must dash.

April 24, 2018

Getting off scot-free or scotch-free? Nothing to do with Scotland, anyway

(4-minute read)

Here’s a wheels-within-wheels eggcorn, or even an eggcorns-within- eggcorns eggcorn.

The standard form of the phrase is ‘to get off scot-free’:

Stone believes the two rig supervisors should be prosecuted, but he also thinks BP’s senior leaders have got away scot-free.

And here’s an example with the eggcorned version:

Every school child, and 99.999999999999% of the rest of us know the name of the ONLY country to commit nuclear genocide on innocent civilians and get away scotch-free.

Q: Is it scot free, scotfree or scot-free?

Dictionaries hyphenate it (Oxford Online, Collins, Cambridge, Merriam-Webster).

At the end of this post there are figures showing the relative frequency of this eggcorn. Meanwhile, let’s delve into scot-free’s backstory.

Q: Scot-free has got something to do with Scotland, Scots, Scottish, hasn’t it?

Nope, absolutely nothing, zilch, diddly squat, nada. It has nothing to do with the nationality, the language or the drink.

(Nor does it have anything to do with the American slave Dred Scott.)

Q: Oh, really!?! So, what is that scot bit, then?

It’s an archaic word for a form of tax. So being ‘scot-free’ meant not having to pay scot, that tax, and then, more generally, not having to pay anything for whatever it might be.

(More specifically, the OED defines scot as ‘A tax or tribute paid by a feudal tenant to his or her lord or ruler in proportion to ability to pay’.)

Q: OK. But what has that got to do with the modern meaning of ‘without punishment or harm’?

As so often happens, people have extended the literal meaning to something more metaphorical and less specific (known by language geeks like me as ‘semantic broadening’).

As just mentioned, scot was a tax, and scot-free also once meant not liable for tax, and then later, more generally, ‘not liable to pay anything’. In parallel, it came to mean ‘escaping punishment, harm, or injury’. Here’s the earliest example in the OED entry (3rd edn., June 2011) of that extended meaning.

Is there eny grett differynge Bitwene theft and tythe gaderynge..? Uery litell,..Savynge that theves are corrected, And tythe gaderers go scott fre.

1528 Rede me & be nott Wrothe sig. H1 (a tract by reformers condemning the abuses of the Catholic Church)

[Is there any great difference between theft and tithe gathering? Very little,..except that thieves are punished, and tithe gatherers go scot-free.]

And here’s a much later example with the financial meaning still very much alive and kicking.

It was therefore thought very unjust by the Legislature, that all others be oblig’d to pay, and those Towns go Scot-free.

1734, London Daily Post, 27 Nov.

Q: Is scotch-free a recent eggcorn?

Well, from the eggcorn database, which records it from as recently as 2007, you might be forgiven for supposing so.

However, the Corpus of Historical American has an example from 1960; and while the earliest OED citation is the 1528 one shown above, the second citation has scotchfree, suggesting that the association with Scotland was made very early on. In other words, the eggcorn goes back at least to the mid-16th century. Perhaps it should be spelled eggkorne in honour.

Daniell scaped scotchfree by Gods prouidence.

1567, J. Maplet Greene Forest f. 93

(Note that scaped for escaped, as in scapegoat.)

If you’re enjoying this blog, and finding it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I blog regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

Q: Is it true that scot-free was once shot-free?

Correct. That’s how Shakespeare put it into Falstaff’s mouth in Henry IV, Pt. 1 v. iii. 30.

Q: Now I’m totally confuseddotcom. What’s the link between scot-free and shot-free, then?

Well, here’s the next wheel or twist. That scot itself is probably a variant of shot, with the same meaning, influenced by Scandinavian skot. However, that shot doesn’t appear in the OED’s records in its own right until 1475:

On cast down her schott and went her wey. Gossip, quod Elenore, what dyd she paye? Not but a peny.

c1475 Songs & Carols (Percy Soc.) 94

Here shot means ‘The charge, reckoning, amount due or to be paid, esp. at a tavern or for entertainment; a or one’s share in such payment. Now only colloq. to stand shot’ (according to the unrevised OED entry).

Scott used it with that meaning:

Are you to stand shot to all this good liquor?

1821, Scott, Kenilworth II. vii. 184

Q: Does anyone still use scot-free in its original meaning?

You mean, ‘not having to pay (tax)’? The OED marks it as ‘rare’, and presents as its most recent citation one from 1921:

The common laborer does not know that that act [on taxation] was passed. He is scot free at 40 cents an hour.

Internal-revenue Hearings before Comm. on Finance (U.S. Senate, 67th Congr., 1st Sess.) 384

But a 1992 citation from Ngrams seems also to refer to this meaning:

Everything will be scotch free, as they say, and McFillen assures me there will be a good fiddle in the expenses if I work my loaf.

Celebrated Letters, John B. Keane.

Q: But to qualify as an eggcorn, doesn’t there have to be a plausible explanation meaningwise of why people use the phrase in the eggcorned version?

That’s right. And the eggcorn database records an ingenious (post)-rationalization of the modern eggcorn, which I’ll quote in full here:

I was watching Big Brother 8 when a ditzy girl said she got off “scotch free.” Well if you think of the powers of the product Scotchguard that protects fabrics from staining thus allowing crap to easily flow off and not stick. Same idea as the current usage of the phrase getting off “scot free,” no?

That’s a similar image to the one that leads to Teflon man, for someone to whom no ‘dirt’ ever sticks.

Q: How common is the eggcorn?

Not very, actually.

Trawling Ngrams, doesn’t help much, because, for example, what look like nineteenth-century references turn out to be references to the Scotch Free Church, generally known as the Scottish Free Church (the use of ‘Scotch’ reflecting an earlier use). The earliest genuine one I’ve tracked down on Ngrams is from a 1992 novel: “The two young men, Dindial and Mascal, had gotten away scotch free.” (But see the earlier discussion.)

The figures below are from the November 2017 release of the Oxford English Corpus, the Corpus of Web-based English and the Corpus of Contemporary American English. As can be seen at a glance, the eggcorn is very much a minority tendency.

Totals

3,012/39

1,130/12

140/0

4,182/51

Form

Corpus

Combined:

OEC

GloWbE

COCA

scot-free

1,974

487

113

2,574

scot free

999

525

24

1,548

scotfree

39

18

3

60

scotch-free

5

2

0

7

scotch free

17

10

0

27

scotchfree

17

0

0

17

April 7, 2018

Objections to ‘to be done with something.’ Uniquely American? I’m done with the topic, anyway.

(four-minute read)

Here’s a language issue that’s new to me.

The other day on Twitter @The_GrammarGeek asked:

‘There’s an opinion out there that it’s wrong to use “done” to mean “finished,” as in, “I’m done with my homework.” But this use of “done” has been widely used since the 15th century. Any idea/when where the false rule originated?’

Another tweep, Karen Conlin (thanks, Karen!) then tweeted that this issue is not mentioned in my edition of Fowler (4th edn., 2015), and asked if I could shed any light on it. Here goes, then…

If you’re in a hurry…

That highly specific use (= ‘to have finished, completed + NOUN’) seems to be mainly U.S.

So, strictures against it have no reason to appear in Br.E. manuals.

That specific use is 18th century onwards, rather than 15th.

According to M-W’s Concise Dict. of English Usage, objections to it were first raised in 1917, with no obvious justification.

If you’ve got longer…

Here’s my two pennies’ worth.

First, to use ‘done’ in exactly that construction, namely, HAVE + done + with + NOUN and with that precise meaning (= ‘to have completed’), is not something I personally would say (is not part of my ‘idiolect’), and – I’m speculating here – is not something most Br.E. speakers would say either. (Looking for evidence in do, one of the most common verbs in the language, could be a Herculean, not to say Sisyphean, enterprise!)

However, I might say ‘I’m done with blogging’, using the pattern to be done with + –ing form (verbal noun), but I think that is a slightly different meaning (‘I will never do it again’ = ‘I’m through with blogging’).

And I would also write, though probably not say, the standard phrase ‘let’s tell him and be done with it’.

If the above claim is true, then there is no reason why a fatwa against the use should exist in Br.E. usage manuals. I’ve checked in all three previous editions of Fowler, and the issue has not been treated. My additions and amendments were based on notes kept over several years about issues that had struck me, and this was not one of them.

Second, what exactly is this use, and where does it come from?

What can the OED can tell us?

Previous edition

The previous edition (1989) makes it a second sub-sense under the more general, somewhat undifferentiated rubric of

‘8. (In pa. pple. and perf. tenses.) To accomplish, complete, finish, bring to a conclusion. to be done, to be at an end.’

The sub-sense is headed

‘b. to be done is used of the agent instead of ‘to have done’, in expressing state rather than action. (Chiefly Irish, Sc., U.S., and dial.)

That geographical information in brackets is important.

The first example given dates to 1766, from T. Amory’s Life of John Buncle II. x. 365

I was done with love for ever.

(Amory, btw, grew up in Ireland.)

The second citation, however, is from Thomas Jefferson: 1771 T. Jefferson Let. T. Adams in Harper’s Mag. No. 482. 206

One farther favor and I am done.

Current edition

The current edition (3rd edn., March 2014) is more nuanced. It puts that Life of John Buncle quotation (I was done with love for ever) at the head of a category (10. a. (b)) captioned thus:

‘Of a person: to be at the end of one’s dealings with, to have no further truck with; = sense10b(b).’

In other words, it makes it equivalent to ‘to have done with something/someone’ as in Shakespeare’s Do what thou wilt for I haue done with thee, and as the earlier edition also did.

On that analysis, the Buncle quote could have been I had done with love forever.

The meaning that is truly the one at issue, I think, is now lexicographed as follows (underlining mine):

‘10. a. (c) Of a person or other agent of action: to be at the end of what one is doing, to be finished. Also with complement expressing the action being finished. Now chiefly U.S.’

That note ‘chiefly U.S.’ chimes with Karen’s hunch that the use is more U.S. than British and is substantiated by the citations the OED chose:

The Jefferson quote heads that category, and the other examples are, with one exception, U.S.:

1876 H. B. Smith in Life (1881) 404 After this is done I am done.

1879 Literary World 6 Dec. 400/1 The mills of the gods are not yet done grinding.

1883 Cent. Mag. 25 767/1 ‘Going..at twenty-four thousand dollars! Are you all done?’ He scanned the crowd.

1971 M. B. Powell & G. Higman Finite Simple Groups i. 5 Since g is arbitrary, we are done [i.e. we have completed the proof].

1981 J. Blume Tiger Eyes (1982) xxi. 87 ‘Davey..are you almost done?’ Jane calls, knocking on the bathroom door.

2000 A. Hagy Keeneland 242 You are full of total dog shit. I’m done putting up with you.

Note the examples with the –ing form, which I noted earlier that I would use. I might also say, similarly to the 1981 example above, ‘Are you quite done!’ as a retort to someone, for example, who was being rude or offensive at length.

Quick statistical note

A trawl in the Feb. 2018 ‘Monitor Corpus’ of the Oxford English Corpus for the string BE + done + with + –ing form retrieves 1,029 examples. Almost half are of unknown source, but of those whose source is known 265 are U.S., 65 British, e.g.

DANIEL Craig is said to be done with playing Bond, but producers are willing to do the impossible to keep the superstar happy.

[image error]

As he’s mentioned in the example above, I couldn’t resist the temptation to add a variant of the almost legendary image from Casino Royale to add pep to a potentially dry topic.

An earlier version of the corpus (2014) shows a not dissimilar ratio.

Yes, but what about the prohibition against?

As I mentioned at the beginning, the M-W dict.’s earliest note is from 1917. The M-W entry also notes the Heritage Usage Panel in 1969 47 percent disapproved of it, suggesting that it was a rule that had been forced on many of them.

Is it still being trotted out/bandied about? If so, please let me know where.