Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 370

September 6, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Chelsea Rooney

Chelsea Rooney

is the author of

Pedal

, a debut novel published in 2014 with Caitlin Press and a finalist for the 2015 Amazon First Novel Award. CBC Books named Chelsea Rooney a WRITER TO WATCH in2015. In 2014, Canada’s book blog 49th Shelf chose Pedal as a Bookof the Year. Chelsea hosts a monthly episode of The Storytelling Show on Vancouver Co-Op Radio.

Chelsea Rooney

is the author of

Pedal

, a debut novel published in 2014 with Caitlin Press and a finalist for the 2015 Amazon First Novel Award. CBC Books named Chelsea Rooney a WRITER TO WATCH in2015. In 2014, Canada’s book blog 49th Shelf chose Pedal as a Bookof the Year. Chelsea hosts a monthly episode of The Storytelling Show on Vancouver Co-Op Radio.1 - How did your first book change your life? I now have to talk about myself in public a lot more.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?Good question. Artist John Baldessari says, “You have to be possessed, which you cannot will.” I don’t think we choose what possesses us.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?My process begins with one to three years of researching ideas I can’t stop thinking about before a story finally begins to take shape through the fog as I get closer to it.

4 - Where does fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?Everything is a book. The work is chiseling out storylines that will have to wait until the next book. Once an idea obsesses me, I begin to see it (and its cousins) everywhere.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?I very much enjoy the readings themselves. I do not really enjoy the day of the reading.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?I write to answer questions about empathy. I’m one of those people who think empathy is the capital “A” Answer to everything. I write toward: “What is this person/group/decade’s specific barrier to empathy? If we added empathy to this problem, what would change?”

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?The role of the writer is to observe and perhaps respond intellectually to their observations. Whether people read and/or find value in those observations and responses is a separate matter, one which the writer does better not to think about.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?I find the process of working with an outside editor both magical and invaluable.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?“Write like a motherfucker,” said Cheryl Strayed.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?Wake up, drink coffee, stare out the window, write fiction, get on bicycle, make money teaching teenagers how to write essays about novels.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?For inspiration I turn to what other people smarter than me have written about the topics in my current novel (Satanic panic, hip hop, 1980s California, crack cocaine.)

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?Lilacs.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?Yes, all of the above.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?Observing (quietly) communities on Twitter of which I’m not a part of has been hugely important to my work. Sometimes I hear old white men on certain radio and television stations say that no one has ever learned anything of value on Twitter and I just laugh and laugh. It’s like, wake up dudes.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?Visit New York City.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?I’m thinking about going back to school for Counseling Psychology. Since PEDAL came out, I have discovered that writing doesn’t fulfill every need I have in terms of giving what I can to others. The private conversations I’ve had with women over the past nine months have fulfilled me more than any publication credit ever could.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?Good question!!!!!

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?Book: We Oughta Know: How Four Women Ruled the ‘90s and Changed Canadian Music by Andrea Warner. Film: Something from Nothing: the Art of Rap directed by Ice T.

19 - What are you currently working on?I’m writing a novel that takes place during 1986 California and near-future British Columbia. It’s about mass hysteria and social technology. Thanks for asking!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on September 06, 2015 05:31

September 5, 2015

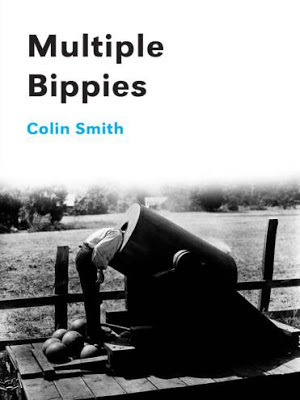

Colin Smith, Multiple Bippies

A national party that slags the native people as stupid puns on welfare, i.e. “they don’t want to work and they don’t want us to work either.”

But neoconservative leaders make extremists of us all.

But seams become dissolving sutures.

We’ll I’ve forgotten who to vote for or against, or why. So, I “did” it.Let me “fill you in.” I’ve put myself in the used-persons column.Put grief on post-dated cheques. Unsure,gave up on those bananas. Went to see the whales at the aquarium. Uncertainif “clamshells” that house the burger are a dangerto the ozone layer. Our lawyers search for language:many get shudders. Guaranteed full insertion? Seems we misspokeour disinformation. Sorry, wrong nerve. Art with a capital “w.”In the nail file of the screenplay of the lunchbox of the sountracakof the gene pool of the bestselling book of the minor votive picture.We tucked our snot behind the headboard till the bed collapsed.We filmed the endgame at Humptulips River. The junk foodis healthier but sunlight is more toxic.

At closure I took a spraybomb,on white side of a tall bank wrote (“Indolent Corollaries”)

Winnipeg poet Colin Smith is the author of 8x8x7 (San Francisco CA: Krupskaya, 2008), as well as the out-of-print Multiple Poses (Vancouver BC: Tsunami Editions, 1997) and Carbonated Bippies!(Vancouver BC: Nomados, 2012), both of which are included as part of the collection Multiple Bippies (Vancouver BC: CUE, 2014), a collection that stretches across the length and breadth of his published work. Poet and critic Donato Mancini has done Smith and his readers a remarkable service through his foreword to the collection, writing that “Smith’s writing is organized around (almost as an excuse for) an obsessive querying of the joke’s efficiacy as a ‘miraculous weapon’ of social incision, ‘cutting the muscles on the blade of silence’ (Césaire 173). Aggravated, Smith is ‘picking at it because it won’t heal’ (37). Each of his meticulously serrated gags locates a point of contradiction – impact site of the punchline or wisecrack. Each locates the type of fissure from where the social body could be pried apart.” As Smith writes in the poem “Multiple Poses”:

Deadly, necessary, do we have consensus yet?

The municipality will transfer an Indian cemeteryto the federal governmentfor $1. We desire belladonnato achieve suppression of white … Heavier earringsthus longer earlobes, a decade of one meal one snack per day.

Lifeas transitional phase, top-heavywith maps, we’ve got our social concerns downpat, suspect that’s part of the heck-like complication, impulsepurchase at the ballot booth.

On whichever scintillating day … Included or not in a fresh poll. Irony is too ironic? Hard work. Off the hook?

Smith’s work has long been engaged with a mixture of language play, social anxiety and a political awareness, all of which stresses an opposition occasionally exploding into a righteous and baffled anger articulated with a mad snarl of bad jokes and puns. There is something about Smith and his work that exist both in the centre and at the margins simultaneously, given his deep engagement with writing, ideas and people paired with his scattered and occasional publication credits, a natural reticence, and general mistrust of systems (all of which are evidenced within his work). As his EPC bio reads: “Moved to Vancouver in 1987 and immediately became part of Kootenay School of Writing ‘doings’. Was an active collective member c.1989 through 1996, and again from 2005 to 2007. Proofread many issues of Writing and Raddle Moon magazines. […] He is now living for the second time in the isolation chamber and racial holy war otherwise known as Winnipeg, Manitoba.”

We – (soundscape) Word!, rapmatter, powerdrill running amok in House of Commons, beanballland of the spree, home of our grave, women’sdevalued dollar, rezone my bank account, newshour, style without context, typos in the concordance, the decisionto invade was made in a synaptic and syntactic fury.

Was there ever a the problem?You would go into the lab without a hypothesis? (“A Boy’s Own Last”)

One of the highlights of the collection is the lengthy post-script interview conducted by Mancini in which the author discusses, among other subjects, the shifts in his writing that came from meeting Dorothy Trujillo Lusk and Kevin Davies, and falling headlong deep into Vancouver’s Kootenay School of Writing collectivethroughout the late 1980s, the 90s and beyond. The interview is important for just how much of the movement and activity throughout the decade, existing as an interesting counterpoint to Michael Barnholden’s hefty introduction to

Writing Class: The Kootenay School of Writing Anthology

(eds. Barnholden and Andrew Klobucar; Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 1999) in which he describes some of the work of the 1990s KSW writers (specifically Kevin Davies) as “linguistic opposition to consumer culture [.]” As well, both interview and foreword allow an opening into the work of a poet who writes slowly, and releases work far too occasionally; providing both deep context and insight.

One of the highlights of the collection is the lengthy post-script interview conducted by Mancini in which the author discusses, among other subjects, the shifts in his writing that came from meeting Dorothy Trujillo Lusk and Kevin Davies, and falling headlong deep into Vancouver’s Kootenay School of Writing collectivethroughout the late 1980s, the 90s and beyond. The interview is important for just how much of the movement and activity throughout the decade, existing as an interesting counterpoint to Michael Barnholden’s hefty introduction to

Writing Class: The Kootenay School of Writing Anthology

(eds. Barnholden and Andrew Klobucar; Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 1999) in which he describes some of the work of the 1990s KSW writers (specifically Kevin Davies) as “linguistic opposition to consumer culture [.]” As well, both interview and foreword allow an opening into the work of a poet who writes slowly, and releases work far too occasionally; providing both deep context and insight.DM: So your friendship with Kevin and Dorothy formed around writing from the start. Was Dorothy already producing interesting work?

CS: Yes, but she was reticent about showing it to other people. I didn’t realize until I read that interview you did with her that I might’ve been among the first she shared her work with. She’d shown it to Kevin and to no one else for the longest time. And for me it was hearing it rather than seeing it. After the [Stephen] Rodefer event I spent basically the spring and summer, and to a lesser degree the fall, drunk in their living room, gabbing about writing. We recited our work to each other, and sometimes just read together (that shared quiet among friends). They were fond of pulling these outrageous, hardcore L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E books off their shelves and throwing them at me: “Have a look at this,” or “Why don’t you read some of this out loud to me?”

DM: Right into the pool without water-wings.

CS: Oh yes, but done out of affection rather than malice, I think. They thought I had a good reading voice that I hadn’t quite learned how to use. That busted me up nicely: to open any unknown book and start reciting from it cold, finding the meaning as I went. The idea was: don’t try to force a poetic voice onto the material, just go. Let the words and their meanings tint as they can’t help but do, let the energy you find take over, and the voice will take care of itself. But Kevin and Dot must have been shrieking internally with laughter, because they were throwing me things like David Melnick’s POET Aid to Memory. Really sonically adventurous work – I had no idea what I was getting into. Absolutely key for me, poetically and politically, was Bob Perelman’s The First World. I thought: “This is it. This is how you do it. This is how you get the personal the political and the social refracting off each other – this is ringing the cherries for me!” To say nothing of being graced with the very occasional text from my two new friends. Dorothy reciting “Stumps” – completely baffling. But this is how I first encountered their writing, through the ear.

Published on September 05, 2015 05:31

September 4, 2015

The Death of The Silver Snail (Ottawa) Comics = Comet Comics!

In case you haven't heard, Ottawa's Silver Snail Comics is closing any day now (apparently the parent store in Toronto decided they couldn't carry both), which is terrible to those of us who have been loyal customers for years.

In case you haven't heard, Ottawa's Silver Snail Comics is closing any day now (apparently the parent store in Toronto decided they couldn't carry both), which is terrible to those of us who have been loyal customers for years.Rose, by the by, was not only born on 'new comic day' (Wednesday), but has gone with me into the Snail nearly every Wednesday of her life since. What will we do with our Wednesdays now? Well, the staff of the Snail are opening up their own place. Check out their website! Go to their store (when it opens)! Rose and I will be there. As they write:

A new chapter begins soon at 1167 Bank Street!

COMET COMICS will feature the same great customer service, easy email hold program and simple special orders that you've come to expect. New weekly comics begin on October 7th and we'll have a selection of fine graphic novels and back issues on opening day (TBA)

We hope to see you there!

Published on September 04, 2015 05:31

September 3, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Elaine Woo

Elaine Woo is the author of

Cycling with the Dragon

, published by Nightwood Editions in Fall 2014. She is a contributor to

Shy: An Anthology

, which won a silver medal IPPY (Independent Book Publishers) award in 2014. Her art song collaboration, "Night-time Symphony" with composer Daniel Marshall won a Boston Metro Opera Festival prize in 2013. Elaine contributed to

V6A: Writing from Vancouver's Downtown Eastside

which was a finalist for the City of Vancouver Book Award in 2012. She is a graduate of the University of British Columbia's creative writing program and has been published internationally.

Elaine Woo is the author of

Cycling with the Dragon

, published by Nightwood Editions in Fall 2014. She is a contributor to

Shy: An Anthology

, which won a silver medal IPPY (Independent Book Publishers) award in 2014. Her art song collaboration, "Night-time Symphony" with composer Daniel Marshall won a Boston Metro Opera Festival prize in 2013. Elaine contributed to

V6A: Writing from Vancouver's Downtown Eastside

which was a finalist for the City of Vancouver Book Award in 2012. She is a graduate of the University of British Columbia's creative writing program and has been published internationally.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My debut book opened up a geyser of reading and performance opportunities reaching a far wider range of people. I met many other writers whom I wouldn’t normally have been exposed to. They broadened the scope of my thinking. My book is a culmination of eight years work beginning from when I first returned to writing in my late forties. My most recent work has more humour in it, some more acerbic. I’ve never maintained a veneer of perfection in my work and readers see my true “stained” self and other flawed characters. I peer closely at family, self, and love. More so than before, I look at what it means to be “small” in the face of powerful parents, as Gaia, confronting uncertainty, death, tyrannical employers, depression, cultural norms, aging, racists, and loneliness.

The work in my first book feels different from my early pieces in various international literary journals in that it’s more sharply honed. I’ve had very positive feedback from family and friends.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I love the options for playing with language, signs, symbols, and formatting that are less used in fiction and non-fiction. I still have the first poem I wrote in Grade 8. My English teacher asked us to make a chapbook of our own work and I went to a leather store to buy a piece of suede for my cover. I wrote a concrete poem about a mouse as the opening poem in this little venture. It seems I’m still writing about “mice” of a different sort.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It doesn’t take long to start most writing projects. An emotional reaction to something may be the first spark. First drafts don’t look at all like the final project. I often go through 25 drafts for any one writing project. For, Cycling with the Dragon, my debut poetry collection, I may have gone through 50 drafts (I’ve actually lost track).

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Emotional upset is a great impetus for a poem and have been my greatest source of inspiration. I begin with a whole hodge podge of shorter pieces. I don’t know from the beginning how they’ll work together but sense they all belong together.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

They are both part of and counter to my creative process. Part of, in the sense that they are a testing ground for whether a poem resonates. I enjoy that sort of live feedback. Counter to, in that public readings take time and energy away from my writing. Writing is my way of processing the world and I’m forced to process in a different outward-leaning way before an audience when I read publicly. This is counter to my nature.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Theoretically, I’m pondering questions of dissonance in my work. Some examples: How do I deal with being at odds with typical women in suburbia? How do I deal with being at odds with my family culture? How does nature cope with uncaring humankind? What do I do when I come across racism? How do I deal with a guilty conscience? How do I deal with growing old in a culture that venerates the young and beautiful?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I see the current role of the writer as being an agent to provoke thought, whether through a tickle or challenge.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I don’t find working with an outside editor hard at all. I have little ego about my work, making the process very simple. I don’t believe I know best. I was very lucky in working with Silas White of Nightwood Editions because he was very respectful in not touching the text of my poems. He had some questions for me but when I gave him my answers he understood why I used certain words over others. He did cut many poems but ultimately, he created a very shapely book. My work stood stronger for having been edited by Silas.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

The best piece of advice I’ve heard about writing is to write in the midst of chaos. I was given this advice by Madeleine Thien when I complained to her that outside noise was preventing me from writing. I harnessed the negative energy of the noise into energy in my poems.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to non-fiction to libretto)? What do you see as the appeal?

I no longer see distinct boundaries between poetry, non-fiction, and libretto. It is easy to move between poetry and libretto. Non-fiction, I see as more akin to formal speech but because it is not so different from everyday speech, I don’t have difficulty transitioning to it. I’ve been thinking about the divide between different genres of literature and for my second manuscript am aiming in some pieces for just a literature that is indistinct as one genre or another.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I do not have a writing routine. When an idea comes to me, then I’ll write it down and perhaps take the initial idea further. I also might leave the idea for a while and come back to it perhaps a week or month later. The only routine I have is to write into the wee night hours.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Lately, I’ve been turning to American Hybrid, ed. Cole Swensen and David St. John. The inventiveness of the poets featured in this Norton Anthology trigger my own creativity. My good friend, poet Carol Shillibeer, introduced me to the book.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The fragrance of cedar reminds me of home. I live surrounded by forest.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of these influence my work. Some of my poems come to me when I’m walking in the woods, or at a concert, or from mathematical concepts, or from a visit to art galleries.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I’ve been reading a lot of Rimbaud lately. I love reading graphic novels and am captivated by the wedding of art and writing which I aim for strictly with words. Madeleine Thien turned me onto the work of Asian exile poets, Bei Dao and Ko Un. I love the work of Brenda Hillman. In my life outside of work, the writings of vegan advocate, Neal Barnard, MD (President of the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine) are very important to me. I credit my good health to being mostly vegan. Good health affects your whole outlook and life.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I have created some graphica, some of which is graphic novel length. I have also written a childrens’ book. Both of these, I would like to see published some day.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

If I were to choose another occupation, I would be a visual artist or film maker. My work is very visual. It would not be a huge leap to move into creating visual media.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I had an absolute compulsion to write. I was driven to express myself. There is creativity and freedom in writing. Before I wrote, I did clerical and secretarial work, which I found very strait jacket.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book I read was At the Sky’s Edge by Bei Dao. The last great film I saw was Chef.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a second poetry manuscript which is looking to be a book about psychological and social mores. The poems in this manuscript are more veiled and “misty” than in my first book.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on September 03, 2015 05:31

September 2, 2015

Anne Boyer, Garments Against Women

It was in September I totally fucked with chronology. I thought memoirs were written by property owners. I was about to fall in love with younger men. When I went back to work at my former employer, offices had been established inside of elevators, and I was asked by my boss “Well do you want to go to the dinner because that would make it 102? Too many, don’t you think?” His daughter was dressed as a witch. I taught her to say Maximus.

In auditoriums, cheerleaders practiced their dances, different squads in different colors with different choreography dancing to the same song. Outside, climate change had caused the environment to become a disaster movie called “Ice Age.” This meant if you stepped off the veranda you would be engulfed by an icy, hard-driving flood, and there would be a soundtrack and voiceover for this. (“Ma Vie en Bling: A Memoir”)

I’ve been struck by Kansas poet and visual artist Anne Boyer’s remarkable collection of prose poems,

Garments Against Women

(Boise ID: Ahsahta Press, 2015). Her second full-length poetry collection,

Garments Against Women

follows

The Romance of Happy Workers

(Coffee House Press, 2008) and numerous chapbooks, including

Anne Boyer’s Good Apocalypse

(Effing Press, 2006),

Selected Dreams with a Note on Phrenology

(dusie, 2007), The 2000s (2009), My Common Heart (2011) and A Form of Sabotage (2013), as well as a book of conceptual work,

Art is War

(Mitzvah, Lawrence, 2008). Organized in four groupings, each containing a small handful of poems, the pieces in

Garments Against Women

are incredibly compact, and move through a series and sequence of thoughtfully compact and restless meditations on boredom, philosophy, sewing, reading and innocence (real and otherwise): “What is the difference between happiness and pornography? I mean what is the difference between literature and photography?” she writes, as part of the extended sequence “The Innocent Question.” There are repeated references within the collection of a writer who isn’t writing, whether through choice or circumstance: “Having given up literature, it was easy to become fixed on the idea of a single shirt, one with two pieces, no facings, not even set in sleeves.” (“Sewing”). When I originally read her “Not Writing,” I had presumed I was reading the work of an older, and far more established writer; suggesting a wisdom gained through hard-won experience, resulting even in a bit of wear. As the poem opens:

I’ve been struck by Kansas poet and visual artist Anne Boyer’s remarkable collection of prose poems,

Garments Against Women

(Boise ID: Ahsahta Press, 2015). Her second full-length poetry collection,

Garments Against Women

follows

The Romance of Happy Workers

(Coffee House Press, 2008) and numerous chapbooks, including

Anne Boyer’s Good Apocalypse

(Effing Press, 2006),

Selected Dreams with a Note on Phrenology

(dusie, 2007), The 2000s (2009), My Common Heart (2011) and A Form of Sabotage (2013), as well as a book of conceptual work,

Art is War

(Mitzvah, Lawrence, 2008). Organized in four groupings, each containing a small handful of poems, the pieces in

Garments Against Women

are incredibly compact, and move through a series and sequence of thoughtfully compact and restless meditations on boredom, philosophy, sewing, reading and innocence (real and otherwise): “What is the difference between happiness and pornography? I mean what is the difference between literature and photography?” she writes, as part of the extended sequence “The Innocent Question.” There are repeated references within the collection of a writer who isn’t writing, whether through choice or circumstance: “Having given up literature, it was easy to become fixed on the idea of a single shirt, one with two pieces, no facings, not even set in sleeves.” (“Sewing”). When I originally read her “Not Writing,” I had presumed I was reading the work of an older, and far more established writer; suggesting a wisdom gained through hard-won experience, resulting even in a bit of wear. As the poem opens:When I am not writing I am not writing a novel called 1994about a young woman in an office park in a provincial town who has a job cutting and pasting time. I am not writing a novel called Nero about the world’s richest art star in space. I am not writing a book called Kansas City Spleen. I am not writing a sequel to Kansas City Spleen called Bitch’s Maldoror. I am not writing a book of political philosophy called Questions for Poets. I am not writing a scandalous memoir. I am not writing a pathetic memoir. I am not writing a memoir about poetry or love. I am not writing a memoir about poverty, debt collection, or bankruptcy. I am not writing about family court. I am not writing a memoir because memoirs are for property owners and not writing a memoir about prohibition of memoirs.

When I am not writing a memoir I am also not writing any kind of poetry, not prose poems contemporary or otherwise, not poems made of fragments, not tightened and compressed poems, not loosened and conversational poems, not conceptual poems, not virtuosic poems employing many different types of euphonious devices, not poems with epiphanies and not poems without, not documentary poems about recent political moments, not poems heavy with allusions to critical theory and popular song.

Some of this wear can even be seen in her 2006 interview with Kate Greenstreet: “I stopped writing poetry for years. / I expected nothing from poetry. / I wrote expecting nothing. / I tried for nothing. I wrote a book. / I still expected nothing.” What is it that wears her down, and what is it that continually brings her back around?

Published on September 02, 2015 05:31

September 1, 2015

above/ground press bundles! 5 chapbooks for $18

Until October 1st, 2015, above/ground press is offering five titles of your choice (while supplies last) for eighteen dollars (plus postage). What a deal!

You can scroll through the backlist here (check for availability of older titles). Available titles include:

Now You Have Many Legs To Stand On, Ashley-Elizabeth Best

Now You Have Many Legs To Stand On, Ashley-Elizabeth Best

Six Swedish Poets, Hugh Thomas

A BOOK OF SAINTS, an excerpt from Saint Ursula’s Commonplace Book, Amanda Earl

ins & outs, Nicole Markotić

Simplified Holy Passage, Elizabeth Robinson

BRCA: Birth of a Patient, Katie L. Price

The Destructions, Amish Trivedi [pictured]

yasser arafat is dead, damian lopes

Happens Is The Sun, Jamie Bradley

Forty Five, produced for rob mclennan's forty-fifth birthday, with new poems by: derek beaulieu, Jason Christie, Amanda Earl, Helen Hajnoczky, Chris Johnson, Gil McElroy, rob mclennan, Christine McNair, Pearl Pirie and Stan Rogal.

CASE STUDY: WITH, Jennifer Kronovet

Texture: Louisiana, rob mclennan

The Doxologies, Gil McElroy

transcend transcribe transfigure transform transgress, an essay by derek beaulieu

Strange Fits of Beauty & Light, Karen Massey

THE BLACKBURN FILES, Kemeny Babineau

Cursed Objects, Jason Christie

today’s woods, Pearl Pirie

Who Let the Mice in Brion Gysin, Gregory Betts

Abject Lessons, Jennifer Baker

Images from Declassified Nuclear Test Films, Stephen Brockwell

THE MOTIONS, Kate Schapira

How the alphabet was made, [an instructional], rob mclennan

Wintering Prairie, Megan Kaminski

Concatenations, Andy Weaver

Source, Susanne Dyckman

Braking and Blather, Emily Ursuliak

THE RAIN OF THE ICE, Eric Baus

Fifteen Problems, Noah Eli Gordon, Images by Sommer Browning

vertigoheel for the dilly, Pearl Pirie

LIME KILN QUAY ROAD, Ben Ladouceur

Estelle Meaning Star, Sarah Rosenthal

and many, many others...

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

To order, send cheques (add $2 for postage; outside Canada, add $4) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9 or paypal at rob_mclennan@hotmail.com

Coming soon: 2016 subscriptions! Including chapbooks, broadsides and Touch the Donkey.

You can scroll through the backlist here (check for availability of older titles). Available titles include:

Now You Have Many Legs To Stand On, Ashley-Elizabeth Best

Now You Have Many Legs To Stand On, Ashley-Elizabeth BestSix Swedish Poets, Hugh Thomas

A BOOK OF SAINTS, an excerpt from Saint Ursula’s Commonplace Book, Amanda Earl

ins & outs, Nicole Markotić

Simplified Holy Passage, Elizabeth Robinson

BRCA: Birth of a Patient, Katie L. Price

The Destructions, Amish Trivedi [pictured]

yasser arafat is dead, damian lopes

Happens Is The Sun, Jamie Bradley

Forty Five, produced for rob mclennan's forty-fifth birthday, with new poems by: derek beaulieu, Jason Christie, Amanda Earl, Helen Hajnoczky, Chris Johnson, Gil McElroy, rob mclennan, Christine McNair, Pearl Pirie and Stan Rogal.

CASE STUDY: WITH, Jennifer Kronovet

Texture: Louisiana, rob mclennan

The Doxologies, Gil McElroy

transcend transcribe transfigure transform transgress, an essay by derek beaulieu

Strange Fits of Beauty & Light, Karen Massey

THE BLACKBURN FILES, Kemeny Babineau

Cursed Objects, Jason Christie

today’s woods, Pearl Pirie

Who Let the Mice in Brion Gysin, Gregory Betts

Abject Lessons, Jennifer Baker

Images from Declassified Nuclear Test Films, Stephen Brockwell

THE MOTIONS, Kate Schapira

How the alphabet was made, [an instructional], rob mclennan

Wintering Prairie, Megan Kaminski

Concatenations, Andy Weaver

Source, Susanne Dyckman

Braking and Blather, Emily Ursuliak

THE RAIN OF THE ICE, Eric Baus

Fifteen Problems, Noah Eli Gordon, Images by Sommer Browning

vertigoheel for the dilly, Pearl Pirie

LIME KILN QUAY ROAD, Ben Ladouceur

Estelle Meaning Star, Sarah Rosenthal

and many, many others...

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

To order, send cheques (add $2 for postage; outside Canada, add $4) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9 or paypal at rob_mclennan@hotmail.com

Coming soon: 2016 subscriptions! Including chapbooks, broadsides and Touch the Donkey.

Published on September 01, 2015 05:31

August 31, 2015

Roy Kiyooka, a web folio : The Capilano Review

My essay on Roy Kiyooka's Pacific Windows has been reprinted as part of a spring 2015 web folio on Kiyooka over at The Capilano Review, alongside a piece by Pierre Coupey, all produced as companion to TCR's Pacific poetries print issue (3.26). Thanks much to Brook Houglum and Todd Nickel,

My essay on Roy Kiyooka's Pacific Windows has been reprinted as part of a spring 2015 web folio on Kiyooka over at The Capilano Review, alongside a piece by Pierre Coupey, all produced as companion to TCR's Pacific poetries print issue (3.26). Thanks much to Brook Houglum and Todd Nickel,

Published on August 31, 2015 05:31

August 30, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Buck Downs

A native of Jones County, Miss.,

Buck Downs

lives and works in Washington DC. His latest book is

TACHYCARDIA: Poems 2010-12

, out now from Edge.

A native of Jones County, Miss.,

Buck Downs

lives and works in Washington DC. His latest book is

TACHYCARDIA: Poems 2010-12

, out now from Edge.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I've had something like four or five first books, it seems like -- the first of many self-published chapbooks/books, the first livre d'artist hand set in real lead type, the first full-length book, the first full-length book where I did not have to chip in on the printer's bill.

I think they were each supposed to change my life, and they did so, mostly by letting me shelf the old work and focus on the next thing.

I always think of my work as a dynamically-evolving enterprise, fearlessly moving forward, but I suspect that it actually has not changed much in the last 20 years, other than a measurable reduction in the frequency of swear words.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Too lazy to be a novelist, too scared of people to be a playwright. And a genuine lack of curiosity about other people ruled out journalism.

So poetry slipped in more or less just when I needed it, and provided traction for a creative impulse that was spinning its wheels.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Starting is not really an issue. I can start (in my head) ten writing projects a day. How long does it take to get one finished?

The work that I am finishing at any given time is based on notes that I took 2-3 years previously. I am always working, and failing, to resolve a backlog, to catch up.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I pretty much always group my poems into fascicles and folders and books. Since the postcard is the central instance of my ongoing writing practice, individual poems are fairly short, i.e., postcard-sized. But they are each incremental additions to the dialectic of the codex.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

At the same time that I am or was the person I described in #2 above, I am also a ham and a pig for attention. So reading my poems is an activity that I still get excited to do.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

For example, how the poems look on the page is itself a statement about the nature of reality. I think anyone could hold a book of mine at arm's length, flip through the pages without reading, and understand the statement they see in the page design.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

So very cool to live in a polyvalent and democratic world, where there is no one role for anybody, but roles, stages, phases, too many for one life to hold.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I work as a freelance writer/editor, and I hear that I am helping out my clients. But my experience is that most poetry editors are too harried to give good feedback; yes and no are are about 9/13ths of all the editorial feedback I have gotten.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Print it out -- the trees will appreciate being included in your creative process. David Allen said that in a talk at the Free Library of Philadelphia.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

A pocket notebook is my daily companion. The workflow that metabolizes those notebooks is fairly labor-intensive, and much of it happens on subway trains/buses.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I cannot be bothered to worry about it. If the biggest problem you have today is you didn't write a poem, then things are going pretty good.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I have found to my comical if pretentious chagrin that the bathroom in my house smells like the one in my grandmother's old house in Ellisville, Miss., where she and my uncle W.A. lived some 60-70 years.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Really just living a life, yall. As I try to explain to myself the conceptual framework of the work, phrases from the business of recorded song, e.g., "demo tape", typically come up.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

The DCPoetry.com crew has been keeping me entertained and busy for 20 years now; by extension the DC Arts Center has been an ongoing source of support.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Get done.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Is poetry my occupation here? I feel like that's a little sad. I've had several jobs of different kinds, but I think I'm a little old to say, for example "I always wanted to be a chemist".

I never wanted to have any kind of job or occupation at all. Maybe that's why poetry, after all.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I was fairly consistently encouraged by every kind of authority figure, parent, older person or peer to abandon poetry and/or writing throughout my school years. Probably defiance has been more of a motivating force than anything.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I am an annoying intellectual fake who delights in telling his peers that the cinema is the intellectual equivalent of paying a millionaire for the privilege of sucking his cock, no exceptions.

So yeah, no last great film for me, thanks.

Heather Fuller has a great new book out Dick Cheney's Heart, I can recommend that without reservation.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Promoting the latest book, Tachycardia; tinkering with the pages of a new book file called "open container"; and drafting some pages for a new book, "cashless transactions".

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on August 30, 2015 05:31

August 29, 2015

Ouroboros (1982-1989): bibliography, and an interview

this interview was conducted over email from April to August 2015 as part of a project to document Ottawa literary publishing. see my bibiliography-in-progress of Ottawa literary publications, past and present here

Ottawa writer and editor

Colin Morton

is the author of numerous poetry books and chapbooks, including In Transit (Thistledown Press, 1981), This Won’t Last Forever (Longspoon Press, 1985), The Merzbook: Kurt Schwitters Poems (Quarry Press, 1987), How to Be Born Again (Quarry Press, 1991), Coastlines of the Archipelago (BuschekBooks, 2000), Dance, Misery (Seraphim Editions, 2003), The Cabbage of Paradise (Seraphim Editions, 2007), The Local Cluster (Pecan Grove Press, 2008), The Hundred Cuts (BuschekBooks, 2009), and Winds and Strings (BuschekBooks, 2013)—as well as the novel Oceans Apart (Quarry Press, 1995).

Ottawa writer and editor

Colin Morton

is the author of numerous poetry books and chapbooks, including In Transit (Thistledown Press, 1981), This Won’t Last Forever (Longspoon Press, 1985), The Merzbook: Kurt Schwitters Poems (Quarry Press, 1987), How to Be Born Again (Quarry Press, 1991), Coastlines of the Archipelago (BuschekBooks, 2000), Dance, Misery (Seraphim Editions, 2003), The Cabbage of Paradise (Seraphim Editions, 2007), The Local Cluster (Pecan Grove Press, 2008), The Hundred Cuts (BuschekBooks, 2009), and Winds and Strings (BuschekBooks, 2013)—as well as the novel Oceans Apart (Quarry Press, 1995). Morton grew up in Alberta, and moved to Ottawa soon after completing an MA in English at the University of Alberta in 1979. He has performed and recorded his poetry with First Draft and other music poetry groups, and his collaboration with Ed Ackerman, the animated film Primiti Too Taa (1988), based on Kurt Schwitters’ Ursonate (Sonata in primitive sounds), led to a Genie nomination, a Bronze Apple, and other international film awards. He has been writer-in-residence at Concordia College (Moorhead, MN, 1995-6) and Connecticut College (New London, CT, 1997).

From 1982 to 1989, he was editor and publisher of Ouroboros, an Ottawa-based publishing house that produced books, chapbooks and ephemera, producing works by himself, as well as a number of poets around him at the time, including Susan McMaster, Chris Wind, Robert Eady, Margaret Dyment and John Bell, and culminated in the anthology Capital Poets, which included work by Nadine McInnis, John Barton, Christopher Levenson and John Newlove. He is currently one of the organizers of The TREE Reading Series.

Q: What was the original impulse for starting the press?

Q: What was the original impulse for starting the press?A: In the summer of 1982, the Tree Reading Series organized Word Fest, a 2-day poetry festival at SAW Gallery in ByWard Market, Ottawa. I edited a chapbook of the featured readers’ poems and worked with artist Carol English to produce the booklets. At the end of the two days of readings I came home hyper-excited and wrote my “Poem Without Shame” in one night-long beat-inspired cry. I thought a lot of the poem and wanted it out there. The prospect of sending it away to magazine editors and waiting a year maybe two before seeing my poem printed almost secretly in some little journal did not appeal to me. I liked the fold-old broadsheets that the League of Canadian Poets had produced for some of its members, and I thought that would be a way to get my poem shamelessly out into public. I chose a rigid cover stock and asked Carol English to adorn my poem with some cover art – something suitably surrealist – and the broadsheet was ready to hand out at readings.

From the start, I liked the idea of being able to control how the printed product looked. I naturally looked around for other projects.

Q: Were you part of the Tree Reading Series at that time? What other activity, whether readings or publishing, were around you at that time in Ottawa?

A: I had some production experience out west with NeWest ReView, Literary Storefront Newsletter and others, so Tree recruited me to create the WordFest catalogues. Ouroboros authors Susan McMaster and Margaret Dyment I met at Tree readings, and others, like Marty Flomen’s Orion series and Juan O’Neill’s Sasquatch. Christopher Levenson edited Arc magazine, then only a few years old, and hosted Arc readings as well. Ouroboros published several of the Arc poets – John Bell, Robert Eady and, later in the Capital Poets anthology (1989), Levenson, Nadine McInnis, Sandra Nicholls, John Barton, Blaine Marchand ... all these poets later published in solo editions by Quarry Press out of Kingston, Ontario. So it was a fairly busy time for poetry in Ottawa.

In addition to all that, I had weekly meetings over coffee and beer with First Draft, a collective of writers, musicians and artists who closed out Theatre 2000 near Byward Market in 1983 with a multimedia performance that including my recital of “Poem Without Shame,” “wordmusic” collaborations and others. The following year, 1984, saw First Draft’s third annual group show appear in the form of a book from Ouroboros – an artist’s book designed by Claude Dupuis of Ottawa. Dupuis filled every corner of every page with visual information, leaving the printer literally no margin for error. The result is The Scream, by far the most ambitious piece of book-making Ouroboros attempted. Smaller projects did use the visual resources of Ottawa’s print shops, and my own desktop publishing efforts. Visual poetry predominated in postcards, posters and chapbooks.

Q: What do you feel your activity through Ouroboros accomplished, and what prompted the press to finally fold?

A: About the time I was rounding up operations at Ouroboros, I had a phone call from John Buschek, who was thinking of starting up his own literary press and asked if I had any advice. I told him it would be a good idea to keep it small. Keep it small so that every project you undertake receives your full attention and love. (By this time I had decided to give my full creative attention to writing novels, one of which was eventually published by Quarry in 1995.) The second piece of advice I gave Buschek was to produce exactly what he wanted. We go into the arts, after all, to create something of ourselves, we don’t write books, or print and distribute them, to fulfill someone else’s dream. I’m glad to see BuschekBooks continuing to grow, a little at a time and, reflecting on the Ouroboros years, I’m glad I could bring those writers to wider public exposure, and to draw attention to Ottawa as a place to make art and literature, to talk and argue about art and literature, because these things matter.

Q: I’m curious about the activity you were involved with out west, before you moved to Ottawa. What prompted the move, and what differences did you see between the communities?

A: This is reaching back into the 70s, into the real arts-and-crafts era of little magazine production. I was involved in little magazines from high school, on though university and after. In 1973, I co-edited Harbinger, an anthology of southern Alberta writing that included Erin Mouré, Andy Suknaski and others. Later, at the NeWest ReView office, we received long strips of copy that we had to glue into straight columns by eye. Layout really was a matter of cut and paste. It could get messy. At Vancouver’s Literary Storefront there would be collating parties, a collective effort to get the monthly publication out on the streets before the events they announced. That was social media in those days.

Like a lot of people, I moved to Ottawa for the work – my wife Mary Lee’s work first and eventually my place in the publication division of a federal department. After supply teaching in Vancouver, I’d have gone anywhere at the first hint of an opportunity. After Vancouver, which had an established literary culture with factions and rivalries, Ottawa was more like Calgary and Edmonton – smaller, just getting active, open to newcomers and new ideas.

Q: The press ended on a high note, with the publication of the anthology Capital Poets. In many ways, the anthology represents just as much the aesthetic of the press as the poets active around you at the time. What was the selection process for the anthology?

Q: The press ended on a high note, with the publication of the anthology Capital Poets. In many ways, the anthology represents just as much the aesthetic of the press as the poets active around you at the time. What was the selection process for the anthology?A: Here’s one of the difficulties in reconstructing literary history. Capital Poets has a finished look to it, and you might see it as a landmark – the eighties generation in Ottawa. But it isn’t that and it didn’t set out to be. My original idea was to put out a monthly leaflet featuring a single writer each month – poetry or fiction or whatever – an author spotlight that could be distributed at readings or given away in bookstores or through the mail. A continuing series.

Two moments’ thought about the economics of the enterprise, though, reveals the problem. We are deluged by a flood of paper; we throw it away, often unread, whether it’s this week’s ads or poetry for the ages. No, the practical way to highlight Ottawa’s writers was through an anthology, up to ten pages from each of ten writers, printed and bound to be kept and remembered a generation later.

Capital Poetsrepresents the poets I spent time with in the eighties, many of whom had connections to Arc and Tree and other literary groups. In a way, the collection was just as important for the writers who weren’t included in the anthology. It mobilized some to create their own anthologies, like Seymour Mayne’s Six Ottawa Poets and Luciano Diaz’s broader Symbiosiscollections. In retrospect, I guess Capital Poets is a kind of landmark; it’s from then that Ottawa writers really start looking at ourselves as a community of interests. When I see Ottawa’s varied literary communities cooperating in our annual VerseFest, WritersFest and so on, I appreciate how much the city has matured, culturally, and how much it continues to change.

Q: Well, and I know, too, of a whole slew of Ottawa poets who didn’t respond to your anthology by putting out one of their own, such as the loosely-grouped poets around Gallery 101: Dennis Tourbin, Michael Dennis, Riley Tench, Ward Maxwell, etcetera. What was the response to the anthology when it appeared?

A: Not to mention Diana Brebner and Marianne Bluger, both emerging nationally about that time. The response to the anthology was vigorous, back pre-Internet when the letters to the editor page gave one a loud blowhorn. Again, the outsiders came across as more scandalized than the insiders were pleased. They took their own inclusion for granted, I guess. I could have gone ahead and published a second volume in the series. There were obviously the poets to fill one out, but the anthology field seemed well ploughed by that time, and I imagined writing would be a more satisfying use of my time, which it was.

Q: Was it as simple as that, then, choosing your writing over the publishing? You add Brebner and Bluger to my shortlist; who or what else emerged during the period you were producing Ouroboros?

Q: Was it as simple as that, then, choosing your writing over the publishing? You add Brebner and Bluger to my shortlist; who or what else emerged during the period you were producing Ouroboros? A: A number of things were wrapping up around that time.

After theatrical productions of Susan McMaster’s Dark Galaxies and my Kurt Schwitters piece, The Cabbage of Paradise (with 3 actors and a 12-voice sound poetry choir), First Draft disbanded and members Andrew McClure and David Parsons moved to Toronto.

My writing was going more and more into prose and narrative, so the cross-media emphasis of Ouroboros was less top-of-mind.

The response to Capital Poets was disappointingly parochial (the opposite of what I’d hoped the anthology would show).

At the day job, the big public service strike started me thinking of going freelance instead. My son was going off to university, and soon I would be offered writer-in-residence gigs in the U.S.

Things end for lots of reasons; more mysterious is why some continue on despite the changes.

Memories tend to be short, and some exciting developments can be forgotten until someone like you, rob, comes along to preserve the memory somehow.

Ottawa in the 80s saw the emergence of valuable venues like Gallery 101, where Dennis Tourbin animated literary events. There, and at SAW Gallery, performance artists like Paul Couillard and Louis Cabri were exploring language in the visual arts context.

The National Library was a regular venue for national, international and local writers, thanks to Randall Ware’s direction.

Ottawa was a centre for the Chilean diaspora writers like Jorge Etcheverry and others though Split Quotation Press.

Patrick White’s Anthos magazine ran as a quarterly tabloid. There were regular reading series like Tree, Orion and Sasquatch.

Young writers were maturing and first books were coming out. Blaine Marchand, though Ottawa Independent Writers (another new organization then), introduced the Archibald Lampman Award.

Young writers were maturing and first books were coming out. Blaine Marchand, though Ottawa Independent Writers (another new organization then), introduced the Archibald Lampman Award.Bywordsemerged from Ottawa U. as a monthly newsletter preceded, I believe, by another monthly newsletter edited by James Cassidy.

Then as now, poets migrated to Ottawa from across the country – John Barton and Stephen Brockwell, for instance – and international poets were attached to embassies – like Shaheen who wrote ghazals in Urdu.

The trouble with such lists, like anthologies, is that something will be left out. But maybe this is enough to suggest that the Ottawa literary scene wasn’t a blank slate before the present generation arrived.

Q: In hindsight, what do you consider the biggest accomplishment of the press?

A: I'm inclined to let others decide what Ouroboros achieved. It might be the publication of the first book by Susan McMaster, Dark Galaxies; or the last long-poem by John Newlove, “In Progress” in Capital Poets; or a performing book like no other, The Scream.

But there’s something else, more personal.

I’m reminded of the Kafka parable about the man who waits his whole life at the door of the castle to be admitted. No one ever comes to invite him inside, and when it’s too late he realizes all he needed to do was to walk through that door. By publishing Ouroboros, I learned that Literature is not some great edifice or institution that we writers have to approach with our begging bowls. It is the sum of everything writers, publishers, critics do. As you know, rob, we just have to be bold enough to walk on past the gate-keepers.

Ouroboros Bibliography

Broadsides1982 – Colin Morton, “Poem Without Shame” (8.5 x 14, 3-fold); art by Carol English1983 – Susan McMaster, “Seven Poems” (8.5 x 14, 3-fold); art by Claude Dupuis1983 – John Bell, “The Third Side” (11 x 17, 4-fold); art by Suanne Rogers1986 – Chris Wind, “The House that Jack Built” (11 x 17 poster)1989 – Richard Kostelanetz, “Openings” (8.5 x 11, 3-fold)

Chapbooks1983 – Margaret (Slavin) Dyment, “I Didn’t Get Used To It” (24 pp.); art by Claude Dupuis1987 – Colin Morton, “Two Decades: from A Century of Inventions” (28 pp.)1989 – Nancy Corson Carter, “Patchword Quilt” (16 pp.)

Books1984 – The Scream: First Draft; the third annual group show (96 pp.); writing by Colin Morton, Susan McMaster, Nan Cormier; music by Andrew McClure, Andrew Parsons; art by Claude Dupuis, Carol English; design by Claude Dupuis1985 – Robert Eady, The Blame Business (50 pp.); cover art by Darien Watson1986 – Susan McMaster, Dark Galaxies (50 pp.); cover art by Roberta Huebener1989 – Capital Poets (96 pp.); poetry by John Barton, Margaret Dyment, Holly Kritsch, Christopher Levenson, Blaine Marchand, Nadine McInnis, Susan McMaster, Colin Morton, John Newlove, Sandra Nicholls

Postcards1983 – Colin Morton, “Dialogue 1” “Dialogue 2” “Dialogue 3” “Dialogue 4”1984 – Penn Kemp, “Incremental”1984 – Colin Morton, “Twins”1984 – LeRoy Gorman, “moon”1985 – Noah Zacharin, “Blues”1985 – Colin Morton, “I read a shadow on the stream”1985 – Robert Eady, “Amnesty” “The Lie” “Concise History of a Room” “How to Lube a Car”1987 – Maureen Korp, “Melting Ice” (with art by Mitsu Ikemura)

Published on August 29, 2015 05:31

August 28, 2015

Colin Browne, The Hatch: poems and conversations

the lava field

or withoutin the lava fiexld

sicxk of himselfon the nigxht boat

this smallpox takesthe piss out of proxfits

wisdom teeth, then cervixthen the armisxtice

when I lisxten it’swe’re safer, not safe

leaves bore legswind adores

across the on thein the dowxn the

bring your shoveland a strong knixfe

takes a biteout of

wires, wirxed cornerswho’s counting

it’s Rudolph thatgoes down in history

de Montaigne on cannibalsa sweextness

tunnel leggersnot craxftsmen

but specixalistsall the same

For his newest collection, The Hatch: poems and conversations (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2015), Vancouver poet and filmmaker Colin Browne continues his incredibly-dense exploration into the serial/book-length poem, composing a collection that, as the book jacket informs, “discovers its true nature as collage.” It is as though Browne doesn’t approach his poetry collections as straightforward serial poems or collections, but structuring a singular work of poetry from the perspective of a documentary filmmaker (entirely different than the “documentary poem” named and championed by Dorothy Livesay), allowing a different kind of narrative flow to emerge, and refreshing a book-length form that desperately requires a new way of seeing. In his recent review over at The Bull Calf, Phil Hall writes:

In The Hatch, Browne is attempting the impossible, and hooray for that: starting from where he is, and who he is (reaching back to Scotland)—he is trying to pan the connections between Surrealism (André Breton, Francis Picabia, etc.) and the West Coast and its Native arts and traditions. You will perhaps remember a photo of André Breton’s desk and study, where art, totems, and masks from BC are on display. One result is that Browne’s book is populated by not only historical figures but by Wolf and Raven and Fungus Man, etc.

How could we not love and be intrigued by a book of poems that celebrates the old-fashioned political savvy of many of our waning heroes? These include (hold your hat) Norman Bethune, Emily Carr, Hank Snow, Aimé Césaire, Charles Olson, Blaise Cendrars, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Antonin Artaud, D H Lawrence, and Sorley MacLean… all in evidence here.

Hall might be the perfect reader for Browne’s work, as both have been, for some time, constructing a series of ever-expanding poetry books-as-units-of-composition utilizing history, personal information, mythology, narrative fragments and collage, and a respect for and repeated homages towards forebears, whether personal or literary, as well as a deep awareness of their natural environment. As Browne writes: “now when i dial the stars / our grande ourse – / Desnos’s bear – / is at the switchboard / good hands you’re in[.]” The Hatch builds upon and furthers the work of his three prior collections, all of which appeared through Talonbooks—

Ground Water

(2002),

The Shovel

(2007) and

The Properties

(2012)—in their exploration of expansive and densely-packed collage-works that stride across a wide canvas, from lyric narrative to meditative fragment to impassioned argument to conversational script, exploring the philosophies of origins across politics, geographic space and an array of traditions. Still, there is as much heart as documentary here. This book contains multitudes, to be sure, as well as an array of feathers. As he writes towards the end of “granny soot”: “i was an open mouth / without feathers or fins / a nestling at the sign / of the celestial bear / i got a hook in the head / of the weir i wove / in the trickle of a shallow / ditch[.]” And of course, as he explores in the poem “rideau,” there are even some moments that explore the capital city, where he spent part of his youth:

Hall might be the perfect reader for Browne’s work, as both have been, for some time, constructing a series of ever-expanding poetry books-as-units-of-composition utilizing history, personal information, mythology, narrative fragments and collage, and a respect for and repeated homages towards forebears, whether personal or literary, as well as a deep awareness of their natural environment. As Browne writes: “now when i dial the stars / our grande ourse – / Desnos’s bear – / is at the switchboard / good hands you’re in[.]” The Hatch builds upon and furthers the work of his three prior collections, all of which appeared through Talonbooks—

Ground Water

(2002),

The Shovel

(2007) and

The Properties

(2012)—in their exploration of expansive and densely-packed collage-works that stride across a wide canvas, from lyric narrative to meditative fragment to impassioned argument to conversational script, exploring the philosophies of origins across politics, geographic space and an array of traditions. Still, there is as much heart as documentary here. This book contains multitudes, to be sure, as well as an array of feathers. As he writes towards the end of “granny soot”: “i was an open mouth / without feathers or fins / a nestling at the sign / of the celestial bear / i got a hook in the head / of the weir i wove / in the trickle of a shallow / ditch[.]” And of course, as he explores in the poem “rideau,” there are even some moments that explore the capital city, where he spent part of his youth:i’ve boned the old syntaxthe ox sprouts two hornsand mistakes submissionfor forgiveness. my colleagues

have been subjects for so longthey’ve come to believe thatcollusion with authoritywhile railing against authority

will imbue them with the authorityto deny having acquired authority.i’m listening to the Peggy Lee Band’s“Floating Island” and hear

a better model for being human.i promise i won’t lie to youwithout knowing thati am lying to you (“rideau”)

The stretch and continuation of his lines and phrases are seemingly endless, helping make The Hatch quite a hefty collection, and one not just of size (nearly one hundred and fifty pages), but in scope and scale, making so much else seem entirely too thin.

Published on August 28, 2015 05:31