Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 374

July 27, 2015

my short story, "Swimming lessons," now featured at Hippo Reads

My short story, "Swimming lessons," part of my work-in-progress "On Beauty," is now online at Hippo Reads. Thanks much to editor Brenda Leifso!

My short story, "Swimming lessons," part of my work-in-progress "On Beauty," is now online at Hippo Reads. Thanks much to editor Brenda Leifso!

Published on July 27, 2015 05:31

July 26, 2015

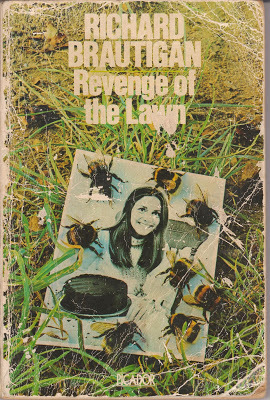

Richard Brautigan, Revenge of the Lawn: Stories 1962-1970

[This short essay originally appeared online a while back; given the entire website seems to have disappeared, I replicate the essay here. An edited version also appears in my second collection of essays, Notes and Dispatches: Essays (Insomniac Press, 2014)]

[This short essay originally appeared online a while back; given the entire website seems to have disappeared, I replicate the essay here. An edited version also appears in my second collection of essays, Notes and Dispatches: Essays (Insomniac Press, 2014)]I must have first read the work of Richard Brautigan when I was eighteen years old. There was a Pocket Book edition of Revenge of the Lawn: Stories 1962-1970 (1972) that my girlfriend at the time was reading, loaned to her by a mutual friend we were just getting to know, Sabrina Mandell. I remember Ann-Marie pulling the book from her locker to show me, a volume she carried around, it seemed, for months. That book became important to me for a number of reasons, not just for the immediate joy and wonder and even sadness the stories brought, but the relationships that the book were a part of: the pixie-joy of Sabrina, and my girlfriend, Ann-Marie, who would, some three years later, give birth to our lovely daughter, Kate. Soon after the stories came The Pill Versus The Springhill Mine Disaster: the selected poems 1957-1968 (1968). If you're Canadian and old enough, you know that Springhill, Nova Scotia is famous for not one but two things: the infamous mine disaster (there were actually three, in 1891, 1956 and 1958) and the hometown of chanteuse Anne Murray (think of the song “Snowbirds”). Brautigan's title and title poem apparently refer to the 1958 disaster, which killed a total of seventy-four miners.

The Pill Versus the Springhill Mine Disaster

When you take your pillit's like a mine disaster.I think of all the people lost inside of you.

Often lumped together with the 'hippie poets' of the late 1960s, many consider Brautigan the last of the Beat poets, and his Bay Area poetics were influenced by Jack Spicer, one of the most influential poets to come out of the area, for poets on both sides of the Canadian-American border. In my late teens and into my twenties, of course, I knew none of this, and, over the next few years, I went through as many of Brautigan's books as I could get my hands on. My initial forays into composing fiction were very much influenced by his work—the small self-contained pearls that accumulated into novels, or even sat by themselves, unbelievably whole for how short they seemed. How could anyone pack so much into such a small space, and with such a sense of wonder? “We know a little about her.” he writes, near the end of the story “Getting to Know Each Other,” “And she knows a lot about us.”

The Scalatti Tilt

'It's very hard to live in a studio apartment in San Jose with a man who's learning to play the violin.' That's what she told the police when she handed them the empty revolver.

In my early twenties, during my daughter's first year, I spent my days schooling and working at a restaurant, scribbling short poems and stories in notebooks, wandering regularly through antiquarian bookseller Richard Fitzpatrick Books on Dalhousie Street for cheap paperbacks, including most of my current Brautigan collection. During my daily travels, there was almost always a Brautigan book of some sort in my sachel. After reading through A Confederate General from Big Sur (1964), I dreamed of my own version, telling my partner that we have to get down to Berkeley, have to get down to California so I can write my “Big Sur novel.” I can't be the only one. I want to find the house where Brautigan lived with the third-storey ghost. The one only he could see. When I found my paperback copy of The Abortion: An Historical Romance 1966 (1971), purchased sometime in 1991, it came with a small drawing slipped between pages. It was the image of a man with squiggles around his head, and an arrow through his neck. A girl beside him, holding flowers, smiles. I'm not sure where the drawing has disappeared, and because of this, the book seems diminished, somehow. My Pocket Book edition like a small archive or library, purchased for three dollars two decades ago, but holding all the important works. It is important to put things back where you found them.

God knows where our original copy of Revenge of the Lawn: Stories 1962-1970disappeared to. I suspect my ex-wife still might have it somewhere on her bookshelf, or perhaps it was returned to Sabrina when we were still teenagers. My replacement copy is larger than the Pocket Book edition, a Picador paperback with a cover I'm not entirely fond of. It has a version of the original book cover, with print of the photo of Sherry Vetter of Louisville, Kentucky, sitting with her chocolate cake, set out on a lawn, the photograph covered in honeybees. It just isn't the same. Still, Revenge of the Lawn: Stories 1962-1970 is important to me because of how long I lived with it, reading and rereading it; important, possibly, because of where I went next, as a direct or indirect result. Through Brautigan, I got my first sense of just how short a story could be, how boiled down fiction made such a stronger effect than wordier prose. Through Brautigan, realizing novels could be written much the same way, each little section adding together into something larger, which is far less scary at the beginning than trying to write a whole novel. It was the first of his books that I read, before realizing I wanted to learn from them all, long before I wrote the poetry collection The Richard Brautigan Ahhhhhhhhhhh (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 1999), or the work-in-progress “A Short Fake Novel about Richard Brautigan.” Perhaps it's important because it reminds me where I've been, and what I no longer have.

It’s a high building in Singapore that holds the only beauty for this San Francisco day where I am walking down the street, feeling terrible and watching my mind function with the efficiency of a liquid pencil. (“A High Building in Singapore”)

Recently, my partner Christine went on a work-related trip down to Washington, D.C., and she took my paperback copy of Trout Fishing in America (1967) to read on the flight. I haven't asked her yet what she thought of it. Mayonnaise.

Published on July 26, 2015 05:31

July 25, 2015

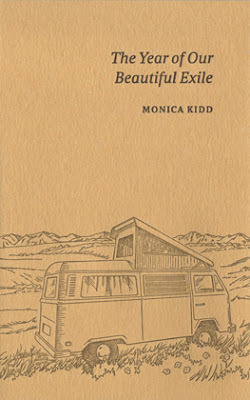

Monica Kidd, The Year of Our Beautiful Exile

A NEW COURSE

Nobody thought about the fish. Stranded in parking lots, ball diamonds, soccer pitches. In basements. Backhoe buckets. A kitchen sink. A toilet bowl, severed from its gasket. An overturned bass drum. A firepit. The trunk of a Toyota Tercel. A little red wagon. A large black boot. A bassinet. A toy box. A suitcase. A child’s wading pool. A tire swing. Concerned officials and willing children picked them up and rinsed them off, launching them down their raw new limnographies.

Calgary writer and family doctor Monica Kidd’s third poetry collection and sixth trade book is

The Year of Our Beautiful Exile

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2015), a collection of short lyric observations composed during, as the title suggests, a year’s worth of travel with her family. The poems in The Year of Our Beautiful Exile are deceptively straightforward, suggesting a straight travel-narrative of sites visited and experiences felt and observed, instead utilizing those same ideas and stories to construct poems that, more often than not, instead focus on cadence, structure and sound. Where I think her poems are the most interesting are when she plays with form and line-lengths, including her forays into the prose-poem, which I’ve long considered some of her strongest writing. Some of the material that falls into her poems in this collection include being displaced by the 2013 Alberta flood, evolution, natural formations of earth, a variety of historical tidbits, and quotes from Walt Whitman, Jan Zwicky, Don McKay and others. Utilized as a form through which to process the world, this is a collection of poems composed as Kidd’s best thinking form, attempting to make sense of the hows and the whys and the whats included over an extended period away, aware of the arbitrariness of what exactly that means. “And what is a year?,” her opening Woody Guthrie quote asks. In the long run, perhaps little; perhaps far more than you’d think, helping reshape all that comes after.

Calgary writer and family doctor Monica Kidd’s third poetry collection and sixth trade book is

The Year of Our Beautiful Exile

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2015), a collection of short lyric observations composed during, as the title suggests, a year’s worth of travel with her family. The poems in The Year of Our Beautiful Exile are deceptively straightforward, suggesting a straight travel-narrative of sites visited and experiences felt and observed, instead utilizing those same ideas and stories to construct poems that, more often than not, instead focus on cadence, structure and sound. Where I think her poems are the most interesting are when she plays with form and line-lengths, including her forays into the prose-poem, which I’ve long considered some of her strongest writing. Some of the material that falls into her poems in this collection include being displaced by the 2013 Alberta flood, evolution, natural formations of earth, a variety of historical tidbits, and quotes from Walt Whitman, Jan Zwicky, Don McKay and others. Utilized as a form through which to process the world, this is a collection of poems composed as Kidd’s best thinking form, attempting to make sense of the hows and the whys and the whats included over an extended period away, aware of the arbitrariness of what exactly that means. “And what is a year?,” her opening Woody Guthrie quote asks. In the long run, perhaps little; perhaps far more than you’d think, helping reshape all that comes after.SHAKESPEARE

Summoning his inner bard, the mayor put out a call for nouns to describe on national television those who would walk the banks of the river in flood. (Later, a clause was enacted allowing the substitution of compelling descriptors.) Diaper licker. Hammer sack. Buzzard briner. Sharp as a heap of sawdust. Quick as a set of square tires. Cousin lover. Lost as a drunken cherry. Jug plucker. Cow tipper. This, of course, was many weeks after His Worship sat beside me at a play about Will being slaughtered by zombies. And that, gentle reader, is as true a story as they come.

The poems in this collection suggest that it is a transitional work, between what Kidd has published previously, working through a series of explorations toward what she might end up producing in the future. Despite some weaker moments scattered throughout, this is a strong collection of lyric poems, all of which make me curious about what she might be working on next.

Published on July 25, 2015 05:31

July 24, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) with Mike Steeves

Mike Steeves lives with his wife and child in Montreal, and works as a fundraiser at Concordia University.

Giving Up

is his first novel. Connect with Steeves on Twitter @SteevesMike.

Mike Steeves lives with his wife and child in Montreal, and works as a fundraiser at Concordia University.

Giving Up

is his first novel. Connect with Steeves on Twitter @SteevesMike.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different? Giving Up is my first published book so it’s still unclear whether it will end up being a life-changing experience. As far as the difference between my current and previous work, I hope that the current work is better.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?I guess because fiction is what I read growing up. If that’s what you’re taking in then I imagine that’s how you’re going to respond. But I also know that I loved stories. Some poems are stories, but they don’t have to be. Non-fiction was definitely not even on my radar. So I wanted to emulate and reply to the stuff that I was reading, and what I was reading was fiction.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes? Giving Up took me two years to write. That’s not including the editing process – that took another year. Once I start writing, things come quickly, provided I stick to it and make time every day (or most days) to do an hour or two of work. I write without any idea of structure or plot so I just start and keep going until I think I’m done. The final version of Giving Up is close to the manuscript I submitted to the publisher, which is to say that there were no major changes or additions. Before I start work on a book I may spend many months not writing anything at all. I will read and feel anxious about not writing and occasionally take down notes and then I think what happens is my anxiety builds to a point where I can’t stand it anymore and then only way out is to start working.

4 - Where does fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?I try to think of whatever I’m working on as a story. It’s either a long story or a short one. Most of my stories are longer ones. As I’m writing I start to think about just how long it’s going to be. So far, I’m typically not that far off the mark.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?I like reading because if it goes well then people will come up to you afterwards and say nice things and I love it when people say nice things to me. But it’s not part of the creative process and based on my limited experience it can be disruptive. I get very nervous and want to do a good job so weeks before the reading is going to take place I will find it hard to concentrate and will spend most of my time imagining how the reading is going to go. And then things go fine and I realize that I wasted weeks of my life worrying about it.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?When I’m writing I think I’m more concerned with the details – the ‘will this work’ mindset – but in the buildup or aftermath of writing I will definitely try to understand why I wanted to tell this particular story. In the case of Giving Up, the big concern was over the paradox between devoting oneself to an overarching goal, and how that goes against the demands of our everyday lives.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?I think there are as many writers are there are roles. Some writers will see their role as one of explaining the world to their readers. Others will see themselves as primarily entertainers. Of course, these roles aren’t exclusive to each other. But it’s pretty clear that in North America the role of the writer has been reduced somewhat and they are no longer expected to be authorities on culture or politics. We have experts for that now. And so writers are often seen as paid entertainers providing cultural commodities and should be solely concerned with providing the maximum entertainment possible to the largest group of people possible. This is a perverse understanding of how literature works. Unfortunately this perspective is frequently endorsed by other writers and critics.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?There’s a huge difference between a manuscript that can be shared among friends and a finished book that can be sold over the counter. I can’t see how Giving Upcould have ever made this transition without Malcolm Sutton. This is the great secret that all authors carry around with them – that books are a collaboration.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?In order to write a book, you have to sit down and write it. Seems like this should be obvious, but many of us seem to forget it.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?I have a day job so I write in the evenings. There’s not much of a routine to it. I just try to carve out an hour or two at the end of the night, after all the life-stuff has been tended to, and my goal is to get at least a page or two and to leave off in a place I’ll know I’ll be able to continue from the following night.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?I read constantly. That helps. But for the most part, even if my writing isn’t going well, I will still continue to write. I may not be happy with what I’m doing, but eventually that changes and I start to feel okay again. When I’m not writing at all, as I mentioned above, that makes me anxious. Anxiety is all the inspiration I need.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?Cleaning products.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?I love the music of John Coltrane and he has definitely served as an inspiration. Not so much the music, but simply his career, the ceaseless searching and experimenting in his work. And his integrity and devotion. All of that comes through in his beautiful playing. Also, I have been going to galleries for years. I love looking at paintings, even though I know very little about painting and visual art and can’t really talk about it, it still means a lot to me and I think some images have had an effect on my work. But what’s great is that it doesn’t have to be good in order to be influential. Flaubert was hugely affected by a painting of Saint Antione that I believe is universally considered to be a mediocre picture.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?Dostoevsky is very important to me – both in my life and in my work.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?Everything.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?I’d like to be a detective. Not in real life though, just make-believe.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?I wish I had an edifying response to this question but I believe I started to write because I thought it would make me famous, and I believed that being famous was a way to avoid death. Wrong on both counts.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?There’s so many great books that it’s possible to read them almost exclusively. I just finished a collection of Tolstoy stories – the Pevear/Volokhonsky translation – that was unquestionably great. His story – The Death of Ivan Ilyich – is a harrowing and courageous look at the experience of dying. The Kreutzer Sonata is simply crazy. One of the craziest texts I have ever read, and I read the 9/11 Commission Report. As far as movies go, I watched John Ford’s Young Mr.Lincoln recently and it was a revelation.

19 - What are you currently working on?I’m writing a story that takes place during a professional development workshop. It’s extremely violent.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on July 24, 2015 05:31

July 23, 2015

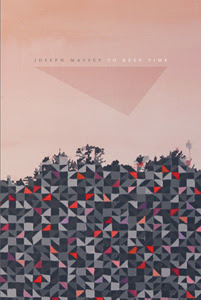

Joseph Massey, To Keep Time

Over a gorge flankedby black oakravens relay calls

that double back inecho. Thickmorning thinned to a

pitch of sun and nohangover.Here you’re either lost

or lost. A wordless-ness writteninto dirt writes

itself around you. (“AN UNDISCLOSED LOCATION IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA”)

As he writes as part of the press release to the collection, American poet Joseph Massey’s To Keep Time (Richmond CA: Omnidawn, 2014) is his “third and final book grounded in the landscape and weather of coastal Humboldt County, California, and contains the last poems I wrote there before moving to the Pioneer Valley of Massachusetts in the winter of 2013. Most of the poems were written with the knowledge that I would be leaving the place that was the backdrop and impetus for just about all of the poetry I wrote since the summer of 2001. I think the gravity of that long goodbye permeates the collection, and the question of place – “the geography of our being,” Charles Olson – became more frantic and fraught than usual.” Following his two previous trade collections –

Areas of Fog

(2009) and

At the Point

(2011) – both published by British publisher Shearsman Books, To Keep Time is a collection of lyric meditations on space, geography and being. Constructed in seven sections, the book includes a longer lyric sequence (“AN UNDISCLOSED LOCATION IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA,”), a variety of lyric suite-sections, and a bookend of short, stand-alone poems—the poem “ANOTHER REHEARSAL FOR MORNING” to open, and the three-line poem “NAMES” to conclude, that reads:

As he writes as part of the press release to the collection, American poet Joseph Massey’s To Keep Time (Richmond CA: Omnidawn, 2014) is his “third and final book grounded in the landscape and weather of coastal Humboldt County, California, and contains the last poems I wrote there before moving to the Pioneer Valley of Massachusetts in the winter of 2013. Most of the poems were written with the knowledge that I would be leaving the place that was the backdrop and impetus for just about all of the poetry I wrote since the summer of 2001. I think the gravity of that long goodbye permeates the collection, and the question of place – “the geography of our being,” Charles Olson – became more frantic and fraught than usual.” Following his two previous trade collections –

Areas of Fog

(2009) and

At the Point

(2011) – both published by British publisher Shearsman Books, To Keep Time is a collection of lyric meditations on space, geography and being. Constructed in seven sections, the book includes a longer lyric sequence (“AN UNDISCLOSED LOCATION IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA,”), a variety of lyric suite-sections, and a bookend of short, stand-alone poems—the poem “ANOTHER REHEARSAL FOR MORNING” to open, and the three-line poem “NAMES” to conclude, that reads:and what remains of them. Night,here, coheres;and the mind unsettles in.

Given its exploration and adherence to geographical space, as well as a cadence of the poetic, meditative lyric, To Keep Time connects in intriguing ways to numerous other titles I’ve seen produced by Omnidawn throughout the past few years, including Karla Kelsey’s A Conjoined Book (2014) [see my review of such here], Robin Clarke’s Lines the Quarry (Omnidawn, 2013) [see my review of such here] and Brian Teare’s Companion Grasses (Omnidawn, 2013) [see my review of such here]. Also, part of what what appeals about the poems in this collection is Massey’s sense of pacing, articulating a sequence of short phrase-lines and line breaks, akin to Robert Creeley or Rae Armantrout, that pause and break and breathe, inching along in one direction while maneuvering outward into multiple others. These are poems that deserve quiet attention, and can move deceptively fast, highlighting turns and curves at breakneck speed. The space and feeling of geography that Massey maps here is intimate, and deep, sketching small moments even as they fracture, diminish and dissolve. Even as he keeps time, he writes with the awareness that it can’t be held, not even within the space of a poem.

ANCHORIC

Listening to winddislodge objectsin the dark aroundmy room, I wantto think thinkingis enough to locatea world, but it isn’t.it isn’t this one.It isn’t this world,weather.

Given that his first three poetry collections are constructed as a trilogy (although I’m uncertain at what point during the compositional process this trio of works became a single unit, whether mid-point, or from the very beginning), it will be interesting to see how his next poetry collection, Illocality (forthcoming this fall from Wave Books), will differ. As he describes his first few publications in his recent “12 or 20 questions” interview:

My first book, Areas of Fog, was more or less a collection of all of my chapbooks up to that point, with the exception of one (Eureka Slough). Once the book came out I felt like a space was cleared — I felt free to get to work on other things — so it changed my life in that respect. With all of those out of print and often very delicate chapbooks reprinted in a single volume, I was able to really look at what I had done. The book provided a beginning.

What’s unfolded since then revolves around the same concerns — attention to immediate details of the daily surroundings, the actual backyard and the universal backyard, the seams and fractures between natural worlds and human intrusion, and perception itself — but lately there’s a gradual drift inward, something (I almost hate to say it) personal coming into the work.

I think that can be heard in the book that’s coming out in the fall, To Keep Time, from Omnidawn.

After having composed a single project for so long, does the idea of what comes next become complicated, or as a relief?

Published on July 23, 2015 05:31

July 22, 2015

rob mclennan's poetry workshops: August-October, in our wee house,

After a successful spring-summer session, I return once again to offering poetry workshops. Originally held at Collected Works Bookstore and Coffeebar, this session will be held at our wee house on Alta Vista Drive (just south of Randall Avenue). Address and directions to be provided.

After a successful spring-summer session, I return once again to offering poetry workshops. Originally held at Collected Works Bookstore and Coffeebar, this session will be held at our wee house on Alta Vista Drive (just south of Randall Avenue). Address and directions to be provided.The workshops are scheduled for Wednesday nights: August 26, September 2, 9, 16, 23 and 30, and October 7 and 21.

$200 for 8 sessions.

for information, contact rob mclennan at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com or 613 239 0337;

An eight week poetry workshop, the course will focus on workshopping writing of the participants, as well as reading various works by contemporary writers, both Canadian and American. Participants should be prepared to have a handful of work completed before the beginning of the first class, to be workshopped (roughly ten pages).

Previous participants over the past few years have included: Amanda Earl, Frances Boyle, Chris Johnson, Roland Prevost, Christine McNair, Pearl Pirie, Sandra Ridley, Marilyn Irwin, Rachel Zavitz, Janice Tokar, Dean Steadman, Nicholas Lea, David Blaikie, James Irwin and Marcus McCann.

For those unable to participate, I still offer my ongoing editorial service of poetry manuscript reading, editing and evaluation. http://www.robmclennan.blogspot.ca/2014/07/robs-ongoing-editing-service-poetry.html

Published on July 22, 2015 05:31

July 21, 2015

Stacy Szymaszek, JOURNAL STARTED IN AUGUST

back to the Projectmis problemas son sus problemas

my love of the word“project” echoes Sontag’s

as do initials

other SS attributesdark circlesgrey streak

*

my new answer tohow long“forever”

*

another argument with Kabout my tone

*

how can it flyso full ofmy blood?

There is very much a quality I can see in New York City poet Stacy Szymaszek’s JOURNAL STARTED IN AUGUST (Projective Industries, 2015) reminiscent of work done by a variety of writers, from the late Vancouver poet Gerry Gilbert, to various “day book” works produced by Robert Creeley, Gil McElroy and many others. JOURNAL STARTED IN AUGUST is a long sequence of short lyrics composed as stand-alone notes, suggesting the journal or notebook, including quick thoughts, overheard conversation, observations and complaints, and the occasional list, all set up as an accumulation of collage-pieces. The author of some half dozen or more books and chapbooks, her at the back of the collection mentions a title, Journal of Ugly Sites and Other Journals, forthcoming this fall with Fence Books. I’m curious to see if this title includes the poems here, or if the book extends and furthers some of which she’s played with in this short collection. The title suggests the possibility of a separate project utilizing some similar approaches to the poetic journal, and then one catches this on the second page, suggesting that this is, in fact, the continuation:

There is very much a quality I can see in New York City poet Stacy Szymaszek’s JOURNAL STARTED IN AUGUST (Projective Industries, 2015) reminiscent of work done by a variety of writers, from the late Vancouver poet Gerry Gilbert, to various “day book” works produced by Robert Creeley, Gil McElroy and many others. JOURNAL STARTED IN AUGUST is a long sequence of short lyrics composed as stand-alone notes, suggesting the journal or notebook, including quick thoughts, overheard conversation, observations and complaints, and the occasional list, all set up as an accumulation of collage-pieces. The author of some half dozen or more books and chapbooks, her at the back of the collection mentions a title, Journal of Ugly Sites and Other Journals, forthcoming this fall with Fence Books. I’m curious to see if this title includes the poems here, or if the book extends and furthers some of which she’s played with in this short collection. The title suggests the possibility of a separate project utilizing some similar approaches to the poetic journal, and then one catches this on the second page, suggesting that this is, in fact, the continuation:memorial portraitof Cass as transitionobject grief reemergesupon finishing “Journalof Ugly Sites” howwill I feel whenI pay off her bills?

This is also something she discussed in her “12 or 20 questions” interview, twoyears ago:

My recent work has dispensed with persona. The longer I live in NYC, the more autobiographical it gets. One idea I have about this is that I had always wanted to live here but I was convinced that I didn’t have what it took, so in my mind this was a city of especially savvy people, a city of heroes—so being here I’ve become heroic, or the persona is now the hero named Stacy. The book I just completed is called Journal of Ugly Sites & Other Journalsand takes up the idea of poetic journalism in different forms. The centerpiece is “Journal of Ugly Sites” which is a year-long journal I kept which documents, among other things, the life, illness and death of a Beagle that my partner and I rescued.

Szymaszek’ssmall text plays off the mundane and even arbitrariness of its own format. Does the suggestion of a daily journal make much of a difference if begun in August or any other month? Gil McElroy’s ongoing lyric sequence “Julian Days” manages to bury specific dates by utilizing an unfamiliar calendar, the Julian Day Calendar, as poem-titles; he presents the dates, but they are unknown to the general poetry reader, and therefore, read as arbitrary numbers (one could look them up if one wishes, but I suspect only a rare few might). The temporal aspect of Szymaszek’s JOURNAL STARTED IN AUGUST is a curious one, with very little in the text to offer any kind of specific placement: if the journal really was begun in August, how long did it last—weeks or months or years—and does that even matter?

hoping the highpotassium is anothermystery my bodyhas authoredwhere no-body dies

*

I guess she thoughtthe alternative

was to bombmy inbox

*

it’s trueno oneshould readafter AnneBoyer

*

grassrootsautocracy

*

Final balance pd.euthanasia bill

and I think it’s going torain today

Published on July 21, 2015 05:31

July 20, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Elena Johnson

Elena Johnson’s poetry has been nominated for the CBC Literary Awards and shortlisted for the Alfred G. Bailey Prize. Her work is featured in Lemon Hound’s New Vancouver Poets folioand has appeared in literary journals across Canada, as well as in four anthologies. Her first book of poetry,

Field Notes for the Alpine Tundra

, was published by Gaspereau Press in 2015. Field Notes for the Alpine Tundra was written and researched during her time as writer-in-residence at a remote ecology research station in the Yukon’s Ruby Range mountains. Originally from New Brunswick, she has lived in many places and currently resides in Vancouver. [photo credit: Ayelet Tsabari]

Elena Johnson’s poetry has been nominated for the CBC Literary Awards and shortlisted for the Alfred G. Bailey Prize. Her work is featured in Lemon Hound’s New Vancouver Poets folioand has appeared in literary journals across Canada, as well as in four anthologies. Her first book of poetry,

Field Notes for the Alpine Tundra

, was published by Gaspereau Press in 2015. Field Notes for the Alpine Tundra was written and researched during her time as writer-in-residence at a remote ecology research station in the Yukon’s Ruby Range mountains. Originally from New Brunswick, she has lived in many places and currently resides in Vancouver. [photo credit: Ayelet Tsabari]1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?My first book has been a long time coming – the first drafts of the poems in Field Notes for the Alpine Tundrawere written in 2008. So I’m pretty happy, and it feels like a great relief, to see them in book form, as a collected whole. What I love, at this point, is that people have taken the book home, and are reading it – not just a few poems here and there, but the whole book, as a collection. And a few of those people are writing to me to tell me how much they enjoyed it, and why. I hadn’t expected these reports on the book from all corners of the country, and they are buoying my spirits as I come down from the excitement of the book launches.

I’ve been lucky, for my first book, to work with a publisher whose work I really respect and admire. When I received the news that Gaspereau had accepted this book for publication, I didn’t stop grinning for days. During the editing and publication process, I felt the book was in good hands – the hands of people who understood what was at the heart of this particular series of poems.

Compared to my older work, the poems in Field Notes feel clearer, sharper and more concise. I’ve been writing haiku and tanka for many years, as well as free verse, and I think perhaps some of that practice in form (and attention) came through in these tundra poems. And it seems to me that I’m paying more attention to sound and diction over time, as well as to form.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?I write in all three genres, but poetry has always come most easily and naturally to me. I find poems satisfying to work on, partly because I always write a first draft of a poem in one sitting (and I can’t do that with fiction or non-fiction). I enjoy the compact nature of poems; so much can be compressed into a few stanzas. And I appreciate the absolute freedom of possibility and experimentation in this genre.

I’ve dabbled in other arts, as well, and I can attest that an advantage to writing, as opposed to, say, painting or photography, is that the tools are easy to carry around. I keep a notebook and pen or pencil in my pocket or bag most of the time; I wouldn’t do the same with paint or a camera.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?For my current book, the poems started out as drafts written in pencil in a notebook during the several weeks I spent in the mountains of the Yukon’s Ruby Range. Poems come fairly quickly for me, interspersed with pages of things that aren’t poems – notes, or sketches, or writing that isn’t poetry. The poems do change over time – my editing process often involves reshaping the poems and removing lines/words/passages. But the basic elements of each poem remain the same.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?While I wish I could work on a “book” from the beginning, I find that approach too restrictive. I write poems as they come to me, and then hope there will be threads running through them that will link them into a book-like collection. I was lucky with Field Notes for the Alpine Tundra: because I was writing about the landscape I was living in, and the experience of being at the research station, I ended up with a long series of poems on the same topic. When I submitted my manuscript to publishers, I hadn’t realized I had enough alpine tundra poems for a book. I was submitting a collection twice this long, with two other sections. Those sections were fairly random collections in themselves. It was my editor at Gaspereau who suggested giving the alpine tundra poems their own book, and I’ve been pleased with that decision. I’m working on two other series right now that focus on one theme or geographic location; I’m challenging myself to try to stick to a theme and work toward a book. But as I think about and push myself to consider these themes, I’ve been writing a very random assortment of other poems. I hope I’ll find some kind of thread that will tie them to one of these themes; if not, I could be working on three separate books right now.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?I love to do readings, but I don’t consider them part of the creative process of writing.

Deciding whether a poem can be presented out loud to a crowd is a sort of test for poems in progress, though.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?What are the limits of language – any language? Especially when faced with seemingly indescribable things, like the deep silence felt/heard/experienced in the Ruby Range? That’s an ongoing concern for me, and something I do try to answer /work around. I can see that coming through a bit in Field Notes, but moreso in one of my newer projects.

My other theoretical concerns are social and environmental, and they are often at the base of whatever I’m working on, even if I don’t realize it at the time. As I put collections of poems together, the thread that runs through them often has to do with these concerns.

I also think a lot about the overlap between art and science. I’m interested in the places where scientific inquiry and poetic/artistic inquiry overlap.

What I see as the current questions in poetry have a lot to do with how to use language differently, and the power of language as a catalyst for change. I’m interested in these questions, and their possible outcomes/answers, but these are not questions/themes I attempt to address in my own work. I’ve also seen a focus on ecopoetry emerging over the last ten years or so, and I’m excited about this. I’m hoping/assuming that my own work falls within this vein of observation and questioning.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?The role of the writer is to listen deeply. I think this would be true in any era/culture.

I also think about the role of the artist in general, and that we need to remember, as a society, that art is essential – to cities, cultures, rural areas, to each human life. Sometimes I find myself in the position of asking someone if they can imagine the world without art – no paintings, photography, films, performances, literature.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?I love it and find it challenging. While doing my MFA in creative writing at UBC, I was enrolled in four workshops with four different groups of writers. Giving and receiving editorial feedback in this context sharpened my own editorial skills, and also helped me get used to receiving editorial comments on my work. I also learned fairly quickly that not everyone’s comments are useful or helpful; it’s important to work with an editor who is on side, who can see what you’re aiming for. Again, I was lucky, with my first book, to have an editor who was such a good match.

I find it takes time to think about suggestions and make sure that I’m putting my ego aside and doing what’s best for the book/poems. I was glad to have quite a bit of time to think about the edits for Field Notes.

I also work as a freelance editor, and enjoy being on either side of the editing process.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?An established fiction writer visited an undergrad English class I was taking at the University of Waterloo many years ago. He told us that an older writer had once advised him to make sure to take care of his teeth, and that he had followed this advice. He advised those of us who were writers to make sure not to neglect our physical health over time. I thought this was very practical and sound advice from one writer to another.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?I wish I could maintain my ideal routine – writing first thing in the morning, with no interruptions – on a regular basis. But life and other work and noisy environments interfere with this routine quite often. I’m going to try to be more strict about this in the coming months. In the past, I’ve also found it helpful to block off an entire day, once a week, that is just for writing. That sounds luxurious right now, but I know it’s possible.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?If I find I’m stalled, I take a break and think about something totally different. And sometimes I remember to ask myself what I’ve been doing with my time: Have I been reading, and what sorts of things? Have I been spending time in nature? Have I taken in any other kinds of art lately? These are all things that rejuvenate me, and if I’ve neglected them or haven’t had time for them, I start to feel poorly and run out of steam for writing.

Sometimes a solution to a problem (i.e. a problematic line or passage) will come to me just as I’m falling asleep or waking up; even if I think I’ve put the problem aside, my subconscious continues to work on it.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?A meadow in the Maritimes in summer – I think it’s the sweet-clover, or apple blossoms, in the breeze. Also a forest in eastern Canada, especially Boreal or Acadian forest – the fir and pine needles, and the smell of the soil… Something about these forests smell like blueberries to me, even when there are no blueberry patches in sight.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?There’s a significant science and ecology influence in my first book, as I have a background in environmental studies and ecology, and wrote the poems at a remote research station. And I’ve written a suite of poems about dance. I’m interested in all the arts, and science… it’s hard to say what influences me most. But I enjoy looking at paintings and photographs or taking in a performance – I find these things revivifying, if not directly influential.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?Charles Simic, Tomas Tranströmer, Roo Borson, Han Shan, Wisława Szymborska, Jen Currin, Erín Moure, John Glenday, Issa, Basho, Niels Hav and Federico García Lorca, for starters.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?I’d like to head further north, up into the Arctic.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?I have many interests, and have been lucky to find interesting employment – or create my own – while slowly writing poems in between and during these jobs. I think if I wasn’t a writer, I would have focussed more seriously on one of these other interests; probably, I would have done more academic work in ecology, or branched out into community arts or human rights/environmental advocacy. If I could start life over with a whole new body, I’d think about becoming a trapeze artist. Currently, I’m freelancing as an editor, which allows me, on a good week, to make time for my own writing.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?I’ve always enjoyed writing, and have often felt compelled to do it – the answer may be as simple as that. My parents are both good editors, so I learned a lot from them as I was growing up. And our house was overflowing with books. My whole family was pretty quiet – there were many nights or afternoons I can recall each of us being in a different room, quietly reading.

I have done several other kinds of work, and have a degree in environmental studies. But I’ve been writing while I did all of these other things, and eventually I decided to take the writing more seriously and spend more of my time doing it. It’s been a really good choice.

Also, if I don’t write, or do some kind of creative work, I become really grouchy. It’s better for everyone around me if I keep at it.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?The book of poetry that’s affected and impressed me the most recently is Iraqi poet Duniya Mikhail’s The War Works Hard, translated by Elizabeth Winslow. The best novel I’ve read within the last year is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah. Right now I’m partway into Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook, as well as Thomas King’s The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America, both of which I’m finding really well written and highly interesting. I loved an NFB documentary I watched a while ago called Carts of Darkness , about the lives of binners in North Vancouver. Oh, and I just sped through Elena Ferrante’s novel My Brilliant Friend, which a lot of Vancouver writers have been raving about, and for good reason.

19 - What are you currently working on?I’m taking a look at the poems that I thought would be the second half of my first book – the non-alpine-tundra poems. And I’ve got two new series of poems underway, one of which I’m thinking more intensively about at the moment. I’m curious to see if these three disparate projects are going to fit into one book, or if each can be a book-length project of its own.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on July 20, 2015 05:31

July 19, 2015

The Sawdust Reading Series (Ottawa) Presents: rob mclennan and TBA

I'm featuring at The Sawdust Reading Series in August (and haven't yet decided if I'm producing a new publication for such). You should totally come by. Here are the details:

I'm featuring at The Sawdust Reading Series in August (and haven't yet decided if I'm producing a new publication for such). You should totally come by. Here are the details:Wednesday, August 19, 2015 at 7pm ; featured readers and short open set ; Pour Boy: 495 Somerset Street West, Ottawa

See their facebook group here, and facebook event here; I even wrote a short profile on the series a while back, over at Open Book: Ontario. I'm curious to see the space, and even recall, a couple of iterations ago, this was the same location for some of the early reading/launches held by In/Words (a decade ago, at least). As they write:

The Sawdust Reading Series is proud to present rob mclennan and our latest contest winner, TBA. Come for the open mic, too!

Pour Boy features on-street parking, direct #2 bus service, and an affordable menu. We will be upstairs!

Published on July 19, 2015 05:31

July 18, 2015

(another) very short story;

Two weeks later, we discovered the box labelled “kitchen, sharp knives” in the baby’s room, exactly where the movers had placed it.

Two weeks later, we discovered the box labelled “kitchen, sharp knives” in the baby’s room, exactly where the movers had placed it.See also: The Uncertainty Principle: stories, (2014)

Published on July 18, 2015 05:31