Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 369

September 16, 2015

fwd: CALL FOR PAPERS: Speaking Her Mind: Canadian Women and Public Presence

CALL FOR PAPERS

Speaking Her Mind: Canadian Women and Public Presence

20-22 October 2016

University of Calgary

http://speakinghermind.ca/

How are women engaging with public discussion and debate in Canada?

Speaking Her Mind: Canadian Women and Public Presence is the follow-up conference to Discourse and Dynamics: Canadian Women as Public Intellectuals, which took place at Mount Allison University in October 2014 (see http://discoursedynamics.ca/). As Discourse and Dynamics made clear, “public intellectual” remains an unsatisfactory term for many women who have contributed to and continue to engage in public discussion and debate in Canada. Speaking Her Mind aims to take that investigation to the next level.

Proposals are invited for presentations that explore Canadian women’s public presence on questions of concern related to social, political, cultural, economic, literary, artistic, linguistic, diplomatic, and environmental issues. A wide range of participation is invited, from individual papers to panels, performances, or other forms of discussion. The following are suggestions but all proposals for individual or collaborative presentations are welcome.

• Women’s right to speak

• Public presences that have made a difference

• When the body speaks

• Speaking about violence, poverty, racism, health

• Politics and its Discontents

• Entering/leaving the public sphere

• Opinions and their backlash

• Forms of speaking: literature, art, music, dance, photography

Proposals should include:

1. title (up to 150 characters)

2. abstract (100-150 words)

3. description (300 words)

& on a separate page a short biographical note and full contact information

Proposals may be submitted electronically by September 28, 2015 to speakinghermind@ucalgary.ca

-----------------

ORGANIZERS:

Aritha van Herk Professor, Department of English

2500 University Dr. N.W.

University of Calgary

Calgary, Alberta

T2N 1N4

Christl VerduynDirector, Centre for Canadian Studies

Professor, Department of English

Mount Allison University

Sackville, New Brunswick

E4L 1G9

Speaking Her Mind: Canadian Women and Public Presence

20-22 October 2016

University of Calgary

http://speakinghermind.ca/

How are women engaging with public discussion and debate in Canada?

Speaking Her Mind: Canadian Women and Public Presence is the follow-up conference to Discourse and Dynamics: Canadian Women as Public Intellectuals, which took place at Mount Allison University in October 2014 (see http://discoursedynamics.ca/). As Discourse and Dynamics made clear, “public intellectual” remains an unsatisfactory term for many women who have contributed to and continue to engage in public discussion and debate in Canada. Speaking Her Mind aims to take that investigation to the next level.

Proposals are invited for presentations that explore Canadian women’s public presence on questions of concern related to social, political, cultural, economic, literary, artistic, linguistic, diplomatic, and environmental issues. A wide range of participation is invited, from individual papers to panels, performances, or other forms of discussion. The following are suggestions but all proposals for individual or collaborative presentations are welcome.

• Women’s right to speak

• Public presences that have made a difference

• When the body speaks

• Speaking about violence, poverty, racism, health

• Politics and its Discontents

• Entering/leaving the public sphere

• Opinions and their backlash

• Forms of speaking: literature, art, music, dance, photography

Proposals should include:

1. title (up to 150 characters)

2. abstract (100-150 words)

3. description (300 words)

& on a separate page a short biographical note and full contact information

Proposals may be submitted electronically by September 28, 2015 to speakinghermind@ucalgary.ca

-----------------

ORGANIZERS:

Aritha van Herk Professor, Department of English

2500 University Dr. N.W.

University of Calgary

Calgary, Alberta

T2N 1N4

Christl VerduynDirector, Centre for Canadian Studies

Professor, Department of English

Mount Allison University

Sackville, New Brunswick

E4L 1G9

Published on September 16, 2015 05:31

September 15, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jehanne Dubrow

Jehanne Dubrow

is the author of four poetry collections, including most recently

Red Army Red

and

Stateside

(Northwestern UP, 2012 and 2010). Her first book,

The Hardship Post

(2009), won the Three Candles Press Open Book Award, and her second collection

From the Fever-World

, won the Washington Writers' Publishing House Poetry Competition (2009). In 2015, University of New Mexico Press will publish her fifth book of poems,

The Arranged Marriage

. She has been a recipient of the Alice Fay Di Castagnola Award from the Poetry Society of America, the Towson University Prize for Literature, an Individual Artist's Award from the Maryland State Arts Council, a Walter E. Dakin Fellowship and Howard Nemerov Poetry Scholarship from the Sewanee Writers' Conference, and a Sosland Foundation Fellowship from the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. Her poetry, creative nonfiction, and book reviews have appeared in The New Republic, Poetry, Ploughshares, The Hudson Review, Prairie Schooner, American Life in Poetry, and on Poetry Daily and Verse Daily. She serves as the Director of the Rose O’Neill Literary House and is an Associate Professor in creative writing at Washington College, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

Jehanne Dubrow

is the author of four poetry collections, including most recently

Red Army Red

and

Stateside

(Northwestern UP, 2012 and 2010). Her first book,

The Hardship Post

(2009), won the Three Candles Press Open Book Award, and her second collection

From the Fever-World

, won the Washington Writers' Publishing House Poetry Competition (2009). In 2015, University of New Mexico Press will publish her fifth book of poems,

The Arranged Marriage

. She has been a recipient of the Alice Fay Di Castagnola Award from the Poetry Society of America, the Towson University Prize for Literature, an Individual Artist's Award from the Maryland State Arts Council, a Walter E. Dakin Fellowship and Howard Nemerov Poetry Scholarship from the Sewanee Writers' Conference, and a Sosland Foundation Fellowship from the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. Her poetry, creative nonfiction, and book reviews have appeared in The New Republic, Poetry, Ploughshares, The Hudson Review, Prairie Schooner, American Life in Poetry, and on Poetry Daily and Verse Daily. She serves as the Director of the Rose O’Neill Literary House and is an Associate Professor in creative writing at Washington College, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I think, like many poets, I found that I was able to turn my attention to new work once that first collection had found a home. I could simply put those early poems behind me and move on.

Each one of my books has a distinct narrative and, as a result, a distinct form (yes, I’m talking about the old saw of form mirroring content). So, for instance, although I’m often described as a poet who works in traditional forms, my next book—The Arranged Marriage—is a linked sequence of prose poems.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I drafted my first poem when I was eleven-years-old and dabbled in poetry from then on. When I was 22, I went through a really sad break-up (with the man who eventually became my husband), and that’s when I began to write poems more seriously. I wrote an Elizabethan sonnet everyday for a year and, when I was 23, I called my parents and told them, “I’m going to be a poet. I’m going to go to graduate school to get something called an ‘MFA.’”

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It really depends on the project and the poem. In general, I find that the early poems in a manuscript come quickly, in part because they access the easiest or most obvious observations about their subject matter. The later poems take longer but are frequently more interesting because they have to move beyond the undemanding metaphors and images toward more nuanced conclusions.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

My poems frequently begin with sound. I’ll hear, in my head, a line that delights me—even if I don’t understand its logic or its narrative impulse—and then follow the music toward meaning.

The poems in my last few collections (Stateside, Red Army Red, The Arranged Marriage) presented themselves to me as books almost immediately. I wrote a few poems and could tell that they belonged to larger narratives, full-length collections whose stories I wanted to tell.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I started out in the theater. So, I’m very comfortable giving readings and enjoy the transition between page and stage. That said, I don’t view readings as a part of my writing process; the poems an audience loves are often not one’s best work, and it’s unwise to use audience response as a way to gauge a poem’s significance or accomplishment.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I’m interested in the ways poems function both as discrete units and as intersecting, overlapping texts in the metanarrative of a book. They’re particles and waves. I believe in mimesis and am always trying to understand more fully the way form mirrors content and content form.

7 - What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I spent a large portion of my childhood in Communist-era Poland, a place where writers and other artists thought very deeply about their role in and duty to the larger culture. Sometimes these kinds of thoughts energized their work but, in the last days of the Cold War, as it became clear that soon the old enemy would be gone or toppled, these kinds of concerns paralyzed many in the intelligentsia.

In general, I try not to reflect to frequently on these sorts of questions, because I find them distracting. My work is most successful when it resides in the specific, the realm of taste and touch and smell and sound and sight. Phrases like “the current role” and “larger culture” are anything but concrete or physical.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love working with editors. I like when editors asked me to explain or justify my choices. When we can articulate our decisions as writers—why we’ve picked this word and not another, why we’ve broken the line here and not here—that’s when we know our work is rigorous, that it’s built both on sound and on good sense.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

It’s not a piece of advice, but I appreciate that so many poets speak about “the craft of writing.” In another life, I would have gone to art school to study textiles and would have become an art quilter. I like the idea that poems are things requiring our hands, our time, our labor. Like a quilt or a well-constructed walnut chair or a thrown clay pot, a poem can be both beautiful and useful. We apprentice ourselves to the craft. We bow our heads, acknowledging that we come from a long line of craftsmen who made many beautiful, useful things before us.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to creative non-fiction to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

There’s a reason so many poets also work in nonfiction; writing a poem has a lot in common with writing a lyrical essay or even a piece of critical prose. All of these texts can think associatively, can make interesting intellectual leaps, can bring together a first-person point of view and the intellect.

Genre-jumping is also a great way to avoid boredom.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write everyday: drafting, revising, editing, researching. I like to joke that I’m a shark; I have to keep swimming, or I’ll die. Sometimes I write in the morning, sometimes in the evening. But I always write.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I don’t believe in writer’s block. When one project isn’t working, I turn my attention to another. I always have several manuscripts in progress, and I have a big list of tricks or games that I use to keep the work moving. I love writing imitations. Ekphrasis also works well for me; just the act of description—describing a work of art—is a great technique for generating words and for turning my attention away from the kinds of anxieties that can so cripple a writer.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I love this question, because I just co-edited an anthology about fragrance, The Book of Scented Things: 100 Contemporary Poems about Perfume .

At the same time, this question is one I can’t answer. I’m the daughter of American diplomats and moved every three to four years, throughout my childhood and adolescence. I was born in Italy, and grew up in Yugoslavia, Zaire, Poland, Belgium, Austria, and the United States. Even though I’ve now lived on the Eastern Shore of Maryland for seven years, I wouldn’t call it home.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

One of the poetry collections I’m currently drafting is called Stories of the Great Operas, which centers on my father’s passion for opera. I’m learning that it’s really hard to write poems about music. In the past, I’ve frequently written about paintings and photography and food, lots of food (come to think of it, the kitchen table is probably the closest place I know to home).

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

American Jewish writers: Philip Roth, Emma Lazarus, Cynthia Ozick, Jonathan Safran Foer, Marilyn Hacker, Nathan Englander, Tillie Olsen, Anthony Hecht, Grace Paley, Howard Nemerov….

Also Holocaust studies: Paul Celan, Saul Friedlander, Marian Hirsch, Ida Fink, Christopher Browning, W.G. Sebald, Charlotte Delbo, Primo Levi, Art Spiegelman, Jean Améry, Felman & Laub, Susan Gubar, Lawrence Langer…

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I want to write a how-to book on the use of imagery in poems. I hope to write a collection of children’s poetry. I would like to write a novel or a book of linked short stories. I want to collaborate with a composer on a traditional, American musical.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I was always torn between becoming a writer, an actor, and an artist. I’m grateful that I decided against a life in the theater. But I still love the visual arts and would have loved to have studied graphic design, which I still dabble in, as part of my work directing the Rose O’Neill Literary House and overseeing the Literary House Press.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I don’t know. Maybe it all goes back to the year I turned 22 and that sad break-up. Maybe, at the time, poems were a more accessible outlet for my hurt than was the stage or the artist’s studio.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I recently reread Maggie Nelson’s Bluets and thought it was every bit as wonderful as I remembered it to be. The other night, I found myself watching The Lives of Others , for the third or fourth time, and felt grateful again for the fact that not every movie is Transformers or The Fast and the Furious.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on two books of poems, Stories of the Great Operas and Dots and Dashes. I’m also drafting a series of essays—I call them “meditative close readings”—about Philip Larkin. And I’m co-editing a new anthology, Still Life with Poem: 100 Natures Mortes in Verse.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on September 15, 2015 05:31

September 14, 2015

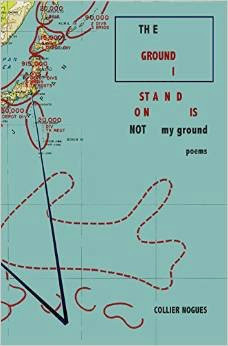

Collier Nogues, The Ground I Stand On Is Not My Ground

The road at early dawn is still here—

I am in the future.

I move my hand to raise its flag in the yard. The quietness

on the surface is breaking

bringing about the form of a person

the nation in

his ear. (“A Book of Patriotic Movements”)

American poet Collier Nogues’ second poetry collection, The Ground I Stand On Is Not My Ground (Chester CT: Drunken Boat, 2015), winner of the 2014 Drunken Boat Poetry Book Contest as judged by Forrest Gander, is a curious reclamation project in a series of recent reclamation projects. One could point to Vancouver poets Jordan Abel, Reneé Sarojini Saklikarand Cecily Nicholson as comparable examples of poets utilizing varying degrees of erasure and documentary to re-claim a series of lost histories, disasters and cultural spaces, for works such as The Place of Scraps (2013) [see my review of such here], Un/inhabited (2014) [see my review of such here], children of air india (2013) [see myreview of such here] and From the Poplars (2014) [see my review of such here]. Nogues, a creative writing teacher in Hong Kong and poetry co-editor for Juked , utilizes erasure and a deft hand to step lightly from phrase to phrase, poem to poem, exploring the nature of and the direct result of a specific armed conflict. As she writes as part of her too-brief opening note: “This book is a hybrid of poetry and digital art. The poems erase historical documents related to the development and aftermath of the Pacific War, especially on the island of Okinawa.”

Towards the worst. In that battle-fielda hundred women.

Women, again.

We dreamed of going to wash theirwhole bodies

their modesty crowded in and out ofbed

uncovering skin.

The illusion was typical, base.

Luxurious to be thieves of virtuesbound to submit to the knife

with open arms,welcoming all unfortunates. (“Across the Plains”)

In one of the blurbs on the back cover, Craig Santos Perez presents us with information that might be seen as important for the context of the collection: “Collier Nogues, who grew up on a U.S. military base in Okinawa, explores how war has shaped the island of her childhood. Taken together, these poems not only express a desire to erase violence, but they also attempt to map the topography of islands and nations, caves and embrasures, weapons and flags, grace and dread.” As the notes at the back of the collection inform, she extracts her poems from works such as Gladys Zabilka’s Customs and Cultures of Okinawa (Revised Edition) (1959), Robert Tomes’ The Americans in Japan (1857), Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1904), Aikoku Undo Nenkan (Yearbook of Patriotic Movements) (1936), Edgar Rice Burrough’s Tarzan of the Apes (1916), A Japanese Interior (1893) and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Across the Plains(1902), attempting to explore “the discourses of empire” to reclaim a space, using, quite often, the words of the oppressor directly in opposition to their original purpose. “I / will explode any day now.” she writes, in the poem “Dear Grace.” There is such a lovely lightly touch across Nogues’ lines and phrases, skipping across the surface of reclaimed text while retaining and repurposing an incredible depth.

In one of the blurbs on the back cover, Craig Santos Perez presents us with information that might be seen as important for the context of the collection: “Collier Nogues, who grew up on a U.S. military base in Okinawa, explores how war has shaped the island of her childhood. Taken together, these poems not only express a desire to erase violence, but they also attempt to map the topography of islands and nations, caves and embrasures, weapons and flags, grace and dread.” As the notes at the back of the collection inform, she extracts her poems from works such as Gladys Zabilka’s Customs and Cultures of Okinawa (Revised Edition) (1959), Robert Tomes’ The Americans in Japan (1857), Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1904), Aikoku Undo Nenkan (Yearbook of Patriotic Movements) (1936), Edgar Rice Burrough’s Tarzan of the Apes (1916), A Japanese Interior (1893) and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Across the Plains(1902), attempting to explore “the discourses of empire” to reclaim a space, using, quite often, the words of the oppressor directly in opposition to their original purpose. “I / will explode any day now.” she writes, in the poem “Dear Grace.” There is such a lovely lightly touch across Nogues’ lines and phrases, skipping across the surface of reclaimed text while retaining and repurposing an incredible depth.

Published on September 14, 2015 05:31

September 13, 2015

On the Art of the Literary Interview : rob mclennan,

I was interviewed recently by Julienne Isaacs for The Town Crier, the blog of The Puritan Magazine, "On the Art of the Literary Interview." Thanks much, Julienne!

I was interviewed recently by Julienne Isaacs for The Town Crier, the blog of The Puritan Magazine, "On the Art of the Literary Interview." Thanks much, Julienne!

Published on September 13, 2015 05:31

September 12, 2015

(another) weekend in sainte-adele,

We spent the bulk of the long weekend, again, at Christine's mother's wee cottage, nestled in the hills and the wood an hour or so north of Montreal. Christine worked on preparing our fall Chaudiere titles for the printer, I worked on an interview or three, and Rose toddled about, including a bout we went off into Sainte-Adele proper for ice cream and wandering. Lemonade, of course, slept. How different these trips are from, seemingly, not that long ago (here; here) when Christine would work days on the main floor, and I would work days in the basement, meeting up for evening dinner and drinks and conversation. Will those days ever come round again? Perhaps a small version of such, as Rose grows; perhaps in another five or six years.

We spent the bulk of the long weekend, again, at Christine's mother's wee cottage, nestled in the hills and the wood an hour or so north of Montreal. Christine worked on preparing our fall Chaudiere titles for the printer, I worked on an interview or three, and Rose toddled about, including a bout we went off into Sainte-Adele proper for ice cream and wandering. Lemonade, of course, slept. How different these trips are from, seemingly, not that long ago (here; here) when Christine would work days on the main floor, and I would work days in the basement, meeting up for evening dinner and drinks and conversation. Will those days ever come round again? Perhaps a small version of such, as Rose grows; perhaps in another five or six years. We might have been up a few weeks ago, but Christine worries this might be our last for the year (despite being only our second time up), given the tenants take over on November 1st. Between her mother and brother caught up in the election, and some of our October, we are most likely skipping Thanksgiving. Might there be another chance? We just don't (yet) know.

We might have been up a few weeks ago, but Christine worries this might be our last for the year (despite being only our second time up), given the tenants take over on November 1st. Between her mother and brother caught up in the election, and some of our October, we are most likely skipping Thanksgiving. Might there be another chance? We just don't (yet) know. And then there was the thunderstorm on Sunday night, that flicked at the electricity and satellite, interrupting our evening stories and internet. The whole building in black, as the rain pounded down on the rooftop and deck. The occasional flash of the whole world, lit sudden and blue.

But I managed no photos of that.

Published on September 12, 2015 05:31

September 11, 2015

The Al Purdy A-Frame Association Call for applications, and "Al Purdy Was Here"

The Al Purdy Association has just announced Call for Applications for 2017 residencies. Applications are due October 16th. For details see www.alpurdy.ca

The Al Purdy Association has just announced Call for Applications for 2017 residencies. Applications are due October 16th. For details see www.alpurdy.caWe are also pleased to announce that the documentary, Al Purdy Was Here will premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. Check out the trailer.

The doc will be showing in other cities; check local listings for updated details.

Here’s the schedule for TIFF’s 2 public screenings:

World premiere

Tuesday, September 15

7pm

TIFF Bell Lightbox Cinema 2

2nd screening

Thursday, September 17

4:45pm

Isabel Bader Theatre

So far, the film is scheduled to show in three other Canadian cities:

Halifax - Atlantic Film Festival: Monday, September.21, 4:15 pm Park Lane Cinemas

Sudbury Cinefest: Saturday, September 26, 1:00 p.m, location TBA.

Edmonton International Film Festival: Sunday Oct. 4 and Monday Oct 5, times TBA

Published on September 11, 2015 05:31

September 10, 2015

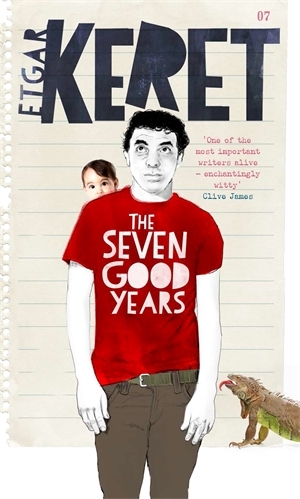

Etgar Keret, The Seven Good Years

When I was a kid, my parents took me to Europe. The high point of the trip wasn’t Big Ben or the Eiffel Tower but the flight from Israel to London—specifically, the meal. There on the tray were a tiny can of Coca-Cola and, next to it, a box of cornflakes not much bigger than a pack of cigarettes. My surprise at the miniature packages didn’t turn into genuine excitement until I opened them and discovered that the Coke tasted like Coke in regular-size cans and the cornflakes were real, too. It’s hard to explain where that excitement actually came from. All we’re talking about is a soft drink and a breakfast cereal in much smaller packages, but when I was seven, I was sure I was witnessing a miracle. Today, thirty years later, sitting in my living room in Tel Aviv and looking at my two-week-old son, I have exactly the same feeling. Here’s a man who weighs no more than ten pounds—but inside he’s angry, bored, frightened, and serene, just like any other man on the planet. Put a three-piece suit and a Rolex on him, stick a tiny attaché case in his hand, and send him out into the world, and he’ll negotiate, do battle, and close deals without even blinking. He doesn’t talk, that’s true. And he soils himself as if there were no tomorrow. I’m the first to admit he has a thing or two to learn before he can be shot into space or allowed to fly an F-16. But in principle, he’s a complete person wrapped in a nineteen-inch package, and not just any person, but one who’s very extreme, an eccentric, a character. The kind you respect but may not completely understand. Because, like all complex people, regardless of their height or weight, he has many sides. (“Big Baby”)

Given that Etgar Keret is one of the most remarkable fiction writers I’ve read, I felt I had no choice but to pick up a copy of his new memoir,

The Seven Good Years

(2015).

The Seven Good Years

is a collection of short non-fiction pieces composed and collected over a seven year period, set in seven sections: “Year One,” “Year Two,” etcetera. The seven year stretch of the pieces run from the birth of his son to the death of his father, in which he observes and comments upon his immediate circle of self, family and identity. He moves through a series of observations on culture and cultural differences, the ongoing shelling around him in Tel Aviv, book tours and the nature of, and the complications, joys and confusions inherent to being father, husband and son. Words that describe his ongoing work often include “wry,” “poignant,” “witty,” “frank,” “enchanting” and “hilarious,” and there is such a buoyancy and optimism to even his darkest writing, one that discussing his parents’ survival of the Holocaust, or another attack in Tel Aviv on the day his son was born, or even the slow death of his father simply can’t diminish. This is (in my opinion), quite simply, an incredibly intimate and understated book by one of the finest of contemporary prose writers.

Given that Etgar Keret is one of the most remarkable fiction writers I’ve read, I felt I had no choice but to pick up a copy of his new memoir,

The Seven Good Years

(2015).

The Seven Good Years

is a collection of short non-fiction pieces composed and collected over a seven year period, set in seven sections: “Year One,” “Year Two,” etcetera. The seven year stretch of the pieces run from the birth of his son to the death of his father, in which he observes and comments upon his immediate circle of self, family and identity. He moves through a series of observations on culture and cultural differences, the ongoing shelling around him in Tel Aviv, book tours and the nature of, and the complications, joys and confusions inherent to being father, husband and son. Words that describe his ongoing work often include “wry,” “poignant,” “witty,” “frank,” “enchanting” and “hilarious,” and there is such a buoyancy and optimism to even his darkest writing, one that discussing his parents’ survival of the Holocaust, or another attack in Tel Aviv on the day his son was born, or even the slow death of his father simply can’t diminish. This is (in my opinion), quite simply, an incredibly intimate and understated book by one of the finest of contemporary prose writers.There is something tricky about attempting to excerpt from Keret’s prose, making me realize the extent to which his short pieces exist as entirely self-contained units. It is impossible to understand the depth and breadth of each essay without presenting entire three-page pieces (which I will not do here, for a variety of reasons). In thirty-six pieces, Keret presents self-contained portraits of an individual, a situation or an idea, sometimes wrapping the three simultaneously, from his sister’s conversion to ultra-orthodoxy, admiring his elder brother, or even the optimism of his parents, who might be forgiven had they slid into pessimism. “When I was a kid,” he writes, in “Long View,” “my parents used to tell me bedtime stories. During World War II, the stories their parents told them were never read from books because there were no books to be had, so they made up their own. As parents themselves, they continued that tradition, and from a very young age, I felt a special pride, because the bedtime stories I heard every night couldn’t be bought in any store; they were mine alone. My mother’s stories were always about dwarves and fairies, while my father’s stories were about the time he lived in southern Italy, from 1946 to 1948.” Further in the same piece, he writes:

When I try to reconstruct those bedtime stories my father told me years ago, I realize that beyond their fascinating plots, they were meant to teach me something. Something about the almost desperate human need to find good in the least likely places. Something about the desire not to beautify reality but to persist in searching for an angle that would put ugliness in a better light and create affection and empathy for every wart and wrinkle on its scarred face.

Published on September 10, 2015 05:31

September 9, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Soraya Peerbaye

Soraya Peerbaye's first collection,

Poems for the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names

(Goose Lane, 2009) was nominated for the Gerald Lampert Award. Her work has also appeared in

Red Silk: An Anthology of South Asian Women Poets

(Mansfield Press, 2004), edited by Priscila Uppal and Rishma Dunlop, Other Voices, Prairie Fire and The New Quarterly. She has contributed to the upcoming chapbook anthology Translating Horses (Baseline Press). Her second collection, Tell: Poems for a Girlhood, is forthcoming with Pedlar Press in fall 2015.

Soraya Peerbaye's first collection,

Poems for the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names

(Goose Lane, 2009) was nominated for the Gerald Lampert Award. Her work has also appeared in

Red Silk: An Anthology of South Asian Women Poets

(Mansfield Press, 2004), edited by Priscila Uppal and Rishma Dunlop, Other Voices, Prairie Fire and The New Quarterly. She has contributed to the upcoming chapbook anthology Translating Horses (Baseline Press). Her second collection, Tell: Poems for a Girlhood, is forthcoming with Pedlar Press in fall 2015.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book was a way of asking myself if I was serious. I had studied theatre, direction, collaborative creation, and translation, and was tip-toeing towards writing, but was utterly intimidated by the act of solo creation. The book was far from what I wanted it to be – some poems, and relationships between poems, I didn’t know how to resolve; still, sending it out into the world was an acceptance of authorship.

My most recent work is the first I’ve created in any context that I can say is done. I was more restless in writing it, was less satisfied; “failed better” in Beckett’s beautiful terms; I sought out the relationships that would help me complete it; I had more stamina.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Poetry felt like a more open space for not knowing.

I remember reading poetry when I was young and being in awe of the poet’s ability to say “I” as though a single voice mattered. I came to poetry late because I didn’t think I could do that. I didn’t go to fiction because I didn’t know if I had a story to tell. In some ways that’s still true; in both my collections I worked through someone else’s story.

Non-fiction would have been a more natural fit, but I wanted to argue my own literalism, my own need for research, reason. Though again – in both my collections, research has been integral. I suppose I made assumptions about the intent of different forms, which I wouldn’t now that I’ve read more. Non-fiction seemed to have a riptide that could carry me towards some kind of righteousness – I mean that without prejudice, I’m only trying to acknowledge my own desire for a stance – and I had an instinct to work against that. I wanted to stay close to that place that felt troubled and uncertain.

Suzanne Robertson ( Paramita, Little Black , Guernica Editions) once said to me that fiction is like a river; poetry is like a well. I like the well. I need time for a moment to drop.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It comes slowly. I write, and overwrite. And then I unwrite. It’s like concentrating a solution: boiling away water so that the found elements become more pronounced.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A book from the very beginning, or at least, a long poem. I’ve rarely written the kind of “one-off” poem that arises from an incidence, a passing state, etc. A series of poems allows me to look at the matter from different perspectives, with different relationships of time.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I’ve never really thought of readings as related to my creative process; I might now that you’ve asked. I am nervous, but I like voicing poems. I don’t know what it will be like to read from Tell, but I think it will be different for me – the poems are based on transcripts. Because there are other speakers in the poems, my feelings for the words are more complicated, less predictable; when I read them out loud in my living room they sometimes catch me off guard.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I think I am always trying to answer the question, how did I come to be here – through what circumstance, chance, choice, systems. That was true of the poems about my dad, or about travelling with my brother to Antarctica. How did three brown people from an island in the Indian Ocean, at the edge of the former British empire, come to be standing at different times on an uninhabited continent, to have their photograph taken next to the very same whalebone? Tell asks a more urgent variant of the question. How did I come to be safe?

I’m trying to name that space between the clear, political articulation of something, and what feels impossible to articulate and raw. When I’m writing about racism, or my own privilege, I’m trying not to name it, because for so many years of my life it was a feeling without a name. The inarticulacy of it makes it a different experience than when you have a name for it. It is bewildering, in the pure, etymological sense.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think our encounter with writers has the same potential as our encounter with any other human being. It’s the potential to see how someone other than us sees. How things matter to them, how things relate.

I love these words from Steinbeck’s The Log from the Sea of Cortez: “None of it is important or all of it is.” I think a writer tells us what none or all is for her.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential, when you find the right editor. I worked with Suzanne and Gerry Shikatani preparing the manuscript of Tell for submission, and relied on them to help me stay true even while I experimented with form. Working with Beth Follett of Pedlar Press was extraordinary. Her response and curiosity went beyond editing the text; she created a rich context for our conversations, writing long responses full of observations beyond a word, a line, a poem; prompting new poems to solidify what she called “the sub-terrain”; all while we exchanged essays by Adrienne Rich and Cathy Park Hong. Like creating an echo chamber around the work.

It isn’t about approval, and in fact I can see where my resistance to certain editorial suggestions focused my own instinct.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Any line from Veda Hille’s song “Instructions”. “17: Remember to surface. 18: Endeavour to dive.” Or “1. Pick it up and put it in your pocket.”

10 – [I make a living working in the dance field, as a producer, manager, consultant etc.] How easy has it been for you to work between disciplines (poetry, dance)? What do you see as the appeal?

I’m neither a choreographer nor a dancer, but I read dance and poetry in similar ways. I think it’s the appeal to an irrational, sensual way of receiving narrative. I find that a choreography ends in ways akin to the ways that poems end. I often have a similar sense of physical suspension.

Or maybe it’s lighting I’m thinking of. Shadow.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I need a sequence of days to write; I can’t do it for a couple of hours here or there. Every now and then I will carve out three or four days between contracts to write; more when grants allow it.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Friends. Reading. Re-reading. Not writing. Often I return to the first collections of poets I love (this was also wisdom from Suzanne). Or I turn to certain poets whose style is unadorned: without technical display of virtuosity, but with whole-hearted and -minded presence, the most direct naming of experience. Which of course is its own virtuosity. But I mean, a style which does not value virtuosity more or less than plainspoken-ness and presence.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Home – childhood, ancestral country, the present in east end Toronto? Fried tomatoes and thyme. Gasoline and hot tar on airport fields. Pears original soap.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

On a formal basis, not that I know. But branches of natural science have often influenced content; I find the technicality, specificity and mystery of the language opens wide fields of association. It also connects me back to my geeky high-school self, and that state of mind where concentration becomes obsession, fascination.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I never know where to stop with this question. Touchstones include Marilyn Dumont, Souvankham Thammavongsa, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha; Ronna Bloom; Lorraine Niedecker and Inger Christensen; Mahmoud Darwish and translator Fady Joudah; more recently Roxane Gay, not only for her writing but her vocal critique of North American literature.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Sing flamenco.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be?

An ASL interpreter. That video that went viral a few months ago, of an ASL interpreter singing Eminem, really turned me on.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It gave me time to say what I meant. Or simply to know what I meant.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Last great book: I am caught between Moby Dick and A Tale for the Time Being, by Ruth Ozeki. Oddly, maybe, for the same reasons: the intimacy between colossal beings, or events, and ordinary human life. The radical relationship between autobiography and catalogue. Cetology, corvology (?) or the flotsam of a tsunami. Ecological collapse. The limits of spiritual practice. The insistence of myth…They even begin the same way. “Call me Ishmael.” “Hi! My name is Nao.”

Last great film: Mad Max.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’ll be working with dance artists in the next year, mostly as a producer, but occasionally as a collaborator.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on September 09, 2015 05:31

September 8, 2015

the ottawa small press fair, fall 2015 edition: November 7

span-o (the small press action network - ottawa) presents:

span-o (the small press action network - ottawa) presents:the ottawa small press book fair

fall 2015 edition will be held on Saturday, November 7, 2015 in room 203 of the Jack Purcell Community Centre (on Elgin, at 320 Jack Purcell Lane).

“once upon a time, way way back in October 1994, rob mclennan and James Spyker invented a two-day event called the ottawa small press book fair, and held the first one at the National Archives of Canada...” Spyker moved to Toronto soon after our original event, but the fair continues, thanks in part to the help of generous volunteers, various writers and publishers, and the public for coming out to participate with alla their love and their dollars.

General info:the ottawa small press book fairnoon to 5pm (opens at 11:00 for exhibitors)

admission free to the public.

$20 for exhibitors, full tables$10 for half-tables(payable to rob mclennan, c/o 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9; paypal options also available

Note: for the sake of increased demand, we are now offering half tables. To be included in the exhibitor catalog: please include name of press, address, email, web address, contact person, type of publications, list of publications (with price), if submissions are being considered and any other pertinent info, including upcoming ottawa-area events (if any). Be sure to send by October 31st if you would like to appear in the exhibitor catalogue.

And don’t forget the pre-fair reading usually held the night before, at The Carleton Tavern! (readers tba)

BE AWARE: given that the spring 2013 was the first to reach capacity (forcing me to say no to at least half a dozen exhibitors), the fair can’t (unfortunately) fit everyone who wishes to participate. The fair is roughly first-come, first-served, altough preference will be given to small publishers over self-published authors (being a “small press fair,” after all).

The fair usually contains exhibitors with poetry books, novels, cookbooks, posters, t-shirts, graphic novels, comic books, magazines, scraps of paper, gum-ball machines with poems, 2x4s with text, etc, including regular appearances by publishers including above/ground press, AngelHousePress, Bywords.ca, Chaudiere Books, Room 302 Books, Arc Poetry Magazine, The Ottawa Arts Review, Buschek Books, The Grunge Papers, Apt. 9, In/Words magazine & press, Ottawa Press Gang, 40-Watt Spotlight, Puddles of Sky Press, room 302 books, Touch the Donkey, Phafours Press and others.

The ottawa small press fair is held twice a year, and was founded in 1994 by rob mclennan and James Spyker. Organized/hosted since by rob mclennan thru span-o.

Come on by and see some of the best of the small press from Ottawa and beyond!

Free things can be mailed for fair distribution to the same address. We are unable to sell things for publishers who aren’t able to make the event.

Also: please let me know if you are able/willing to poster, move tables or distribute fliers for the event. The more people we all tell, the better the fair!

Contact: rob mclennan at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com for questions, or to sign up for a table

Published on September 08, 2015 05:31

September 7, 2015

Sarah Blake, Mr. West

A Day at the Mall Reminds Me of America

Recently, my 14-year-old sister was approached at the mall to see if she’d be interested in working at Hollister, or Abercrombie and Fitch, or American Eagle. I can’t remember.

She’s that beautiful. And with the mall’s lights all around her—I can only imagine.

Yet on Facebook, one of her friends calls her a loser. More write, “I hate you.”

I wonder if Kanye knows that these girls are experimenting. As with rum. As with skin, all the ways to touch it.

My day at the mall begins with a Wild Cherry ICEE and an Auntie Anne’ Original Pretzel. A craving.

I pass women who you can tell are pregnant, and I know we all might be carrying daughters.

The mall is so quiet. The outside of the Hollister looks like a tropical hut, like the teenage girls should be sweating inside.

No one’s holding doors for me yet, but they will as I take the shape of my child.

And if my child has a vicious tongue, it will take shape lapping at my breast.

American poet Sarah Blake’s first collection is

Mr. West

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2015), a collection that “covers the main events in superstar Kanye West’s life while also following the poet during her pregnancy, a time she spent researching and writing these poems. This book explores how we are drawn to celebrities—to their portrayal in the media—and how we sometimes find great private meaning in another person’s public story, even across lines of gender and race.” In Blake’s collection of lyric meditations, the blend of her own personal threads against Kanye’s public self are intriguing, and her pop culture commentaries allow the distraction against her being able to dig further into what, at times, becomes a deeply personal and revealing work. The book opens with the poem “‘Runaway’ Premiers in Los Angeles on October 18, 2010,” that includes: “I am two months pregnant. // Monday this premiere, Tuesday this article, Wednesday / my first ultrasound, with my child’s boneless arms in motion.” The piece ends with the declaration: “The two of you, tied to this week in my life.”

American poet Sarah Blake’s first collection is

Mr. West

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2015), a collection that “covers the main events in superstar Kanye West’s life while also following the poet during her pregnancy, a time she spent researching and writing these poems. This book explores how we are drawn to celebrities—to their portrayal in the media—and how we sometimes find great private meaning in another person’s public story, even across lines of gender and race.” In Blake’s collection of lyric meditations, the blend of her own personal threads against Kanye’s public self are intriguing, and her pop culture commentaries allow the distraction against her being able to dig further into what, at times, becomes a deeply personal and revealing work. The book opens with the poem “‘Runaway’ Premiers in Los Angeles on October 18, 2010,” that includes: “I am two months pregnant. // Monday this premiere, Tuesday this article, Wednesday / my first ultrasound, with my child’s boneless arms in motion.” The piece ends with the declaration: “The two of you, tied to this week in my life.”The bulk of Mr. West explores the public details of Kanye West’s life and his career. Blake writes of Kanye’s public declarations, his mother, Taylor Swift, his automobile accident, specific performances, Hurricane Katrina and his infamous ego, even as she weaves in details of her pregnancy alongside quantum physics, philosophy and notions of fame. Writing seriously on pop culture, Blake’s poems attempt to enter into the information of his life, writing: “Kanye, if only I could write a poem for you and not about you.” One could easily make a comparison between Sarah Blake’s first collection Mr. West and Philadelphia poet and editor Julia Bloch’s first collection, Letters to Kelly Clarkson (Sidebrow Books, 2012) [see my review of such here] (as well as works by Montreal poet David McGimpsey) for obvious reasons, as much as for the fact of both books attempting to speak directly to their subject through poetry, and through using literature to explore seriously a genre not often taken as seriously as perhaps it should. As she writes in the poem “The Fallible Face”:

Kanye, you must have a relationship with your reflection I can’t understand.To structure, to surgery, to form.

in the access to the face there is certainly also an access to the idea of God

How did they put you together again?How did you feel when someone saw you who didn’t know

you had ever looked like someone otherthan yourself?

Published on September 07, 2015 05:31