Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 367

October 6, 2015

Author questions for rob mclennan : Hayley Malouin

Hayley Malouin

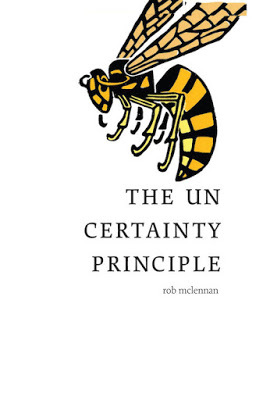

is a graduate student studying Comparative Literature and Arts at Brock University. In her final undergraduate year, she conducted this interview with rob about his recently published collection of stories,

The Uncertainty Principle

, as part of a creative writing class taught by Prof. Natalee Caple. Hayley also works as atheatre critic and editor at DARTcritics, a blog devoted to new and diverse critical voices created by Prof. Karen Fricker.

Hayley Malouin

is a graduate student studying Comparative Literature and Arts at Brock University. In her final undergraduate year, she conducted this interview with rob about his recently published collection of stories,

The Uncertainty Principle

, as part of a creative writing class taught by Prof. Natalee Caple. Hayley also works as atheatre critic and editor at DARTcritics, a blog devoted to new and diverse critical voices created by Prof. Karen Fricker.1. Some of these stories were originally tweets. What do you think the connection between short story writing and social media platforms is? Do you find Twitter to be an inspiring or creative platform?

I had enormous fun composing those stories, and found the constraint of 140 characters both exhilarating and rather tricky. Just what can you pack into a small space? Given that the entire collection works on that very idea, working to boil down even further became an interesting experiment. I wrote quite a number of pieces, composing rather quickly and posting directly to twitter, but only a half dozen or so made the final manuscript.

I actually wrote about the process of composing for twitter on my blog, here: http://robmclennan.blogspot.ca/2012/08/how-to-not-be-on-twitter.html

2. There is a certain brand of Canadian fiction that you call ‘retelling’. How do you feel your work positions itself in relation to this kind of national storytelling?

There is that one story that does deliberately reference a certain kind of Canadian stereotyping when it comes to fiction, which was far more prevalent in the 1960s and 70s. Somehow, some of these ideas still linger here and there, and I simply wanted to reference some of those continuing stereotypes.

‘National storytelling’ – what does that even mean? We tell our stories from the perspectives we understand, but not all stories from all regions are going to be the same. There might be some overlap, certainly, here and there, but the diversity of stories and the ways in which they are told are simply not acknowledged nearly enough.

3. Do you feel that living and working in Ottawa has consciously politicized your work? Phrases like “A parliament, of owls” and “An army, of herrings” lean towards political commentary. How important is this to your fiction and non-fiction work?

Proximity to Parliament Hill, even with my twenty years of living in Centretown, hasn’t changed a speck of my work. Living in Ottawa has never meant anything in regards to the political being any more prominent in my day-to-day.

If I’ve begun to weave the political into any of my writing over the past few years, it has been through my frustration with the seismic shifts that Stephen Harper’s Conservatives have made in policy and action, moving further away from a Canada that I even recognize. His Canada is not mine.

4. The Uncertainty Principle almost reads like a collection of poems. What motivated you to move from writing poetry to writing short stories and novels? Are these connected for you? How are they different?

One could say everything I do is connected, even if only through being written by the same hand. I’m sure there are connections somewhere. This is actually my third work of fiction (not including a third novel completed before this book this was published), and I’m already working on two further collections of short stories. I’ve always been interested in the possibilities of other forms. It might read like poems through the lyric brevity, but I see them very much as fiction: they’re built in full sentences, and tell a series of linear narratives.

Back in the late 1990s, when I started focusing more on fiction (after nearly a decade of focusing on poetry), I noticed that utilizing a new form meant that the ‘storytelling’ aspects began to fall away from my poetry, which I found rather interesting. It allowed my poetry to move in other directions.

5. Is there anything you are afraid or hesitant to write?

There are some elements of the book that speak to the intimate, such as the story about no longer believing my mother. I wasn’t necessarily afraid or hesitant, but using more intimate material pushes me to work far harder to get the story just right.

Precision is important.

6. After having these stories compiled from your Twitter account, blog, etc. do you find that you have received a different type of critical reception? How is online criticism different from traditional print criticism?

To put my work in only one form or place, whatever that might be, automatically reduces my audience: it presumes that anyone can only interact with my work by going to one place. It would be the same if I were to ignore print journals over online, or the other way around. For the same reason, I often review for print and online journals beyond my own blog: I can’t presume that everyone is going to come to me to read whatever it is I’m on about.

Having said that, I don’t think the criticism is any different at all. The form and forum is simply a tool in which to present and disseminate the work. The same argument applies via print books vs. e-publications. It’s all just reading.

I think any writer should always work to publish in a variety of media far wider than they themselves might actually use. One shouldn’t presume that any reader that wants to read your work has exactly the same reading habits that you do.

And the pieces weren’t “compiled from” in any way. I work on book-length projects, and then send pieces out into the world as appropriate, including sending out to journals, selecting chapbook-length manuscripts and even posting the occasional piece on the blog. The book is the main project, and not a matter of accident after the fact.

7. I can’t help but be reminded of bell hooks by the characterization of your name - rob mclennan. Why do you choose to not capitalize your author name? Does it serve as a kind of nom de plume that separates you from your work?

Originally, back in the early 1990s, my logic was two-fold: I wanted to minimize my name in a certain way, to make the focus on the work and not me, and the fact that I think it looks far better than “Rob McLennan” – the lower case looks far more sleek. I wonder, too, if I might have been working to differentiate myself via writing from the rest of my family (a normal element of being in one’s twenties, I’m sure).

8. Why do you choose to self-publish online as well as through traditional publishers? What are the benefits of publishing online?

Self-publish: are you referring to posting occasional poems and short stories to my blog? The benefits of online publishing, generally, mean that the work can go much further than traditional print means, and the effects are immediate. For years now, my blog has been getting upwards of 1,500 daily ‘hits,’ which means that anything I post to my blog is going to get a far wider audience, both in terms of numbers and geography, than most trade literary journals in Canada.

9. Has the rise of the blogosphere and ‘blogger’ as a job title in any way impacted what you write and how you publish it?

Yes and no. After writing reviews for a weekly paper for four-and-a-half-years, I originally began my blog so I could focus more on writing than on chasing venues for errant reviews and essays. The forum has allowed my critical skills to develop considerably (I’ve since published two collections of critical essays, for example). I do like the immediacy of the blog: I can publish a review of a new poetry collection within a week or two of the publication date (sometimes earlier), instead of having two wait for print journals to catch up, sometimes six or even twelve months later. A review posted online can be utilized by both author and publisher, and help push attention towards a brand-new publication. This seems far more useful than a review months later. Although, having said that, there are benefits, also, to a review posted months later: usually the reviewer/critic can go far deeper, allowing for a larger critical study of a particular work. I focus predominantly on the relatively-quick piece, to help push the book as it begins its published life.

Also: I’ve never used such as ‘job title.’ I’m a writer: that encompasses all.

10. Your stories are inundated with pop culture references, both old and new. Are there challenges in weaving pop culture into such short stories?

I don’t see this as a challenge. I exist in the world, so why shouldn’t my writing reflect that?

As Gertrude Stein apparently said: write of the world you live in.

Published on October 06, 2015 05:31

October 5, 2015

On Writing : an occasional series

We're some two and a half years and more than seventy essays into the occasional series of "On Writing" essays I've been curating over at the ottawa poetry newsletter blog. I've included an updated list, below, of those pieces posted so far, and the list is becoming quite substantive. Way (way) back in April, 2012, I discovered (thanks to Sarah Mangold) the website for the NPM Daily, and absolutely loved the short essays presented on a variety of subjects surrounding the nebulous idea of “on writing.”

We're some two and a half years and more than seventy essays into the occasional series of "On Writing" essays I've been curating over at the ottawa poetry newsletter blog. I've included an updated list, below, of those pieces posted so far, and the list is becoming quite substantive. Way (way) back in April, 2012, I discovered (thanks to Sarah Mangold) the website for the NPM Daily, and absolutely loved the short essays presented on a variety of subjects surrounding the nebulous idea of “on writing.”Forthcoming: new essays by Sheryda Warrener, Eileen R. Tabios, Barbara Tomash and Eric Schmaltz.

On Writing #73 : Pam Brown : Writing : On Writing #72 : Renee Rodin : The Nub : On Writing #71 : Rebecca Rosenblum : Ways to Help a Fellow Writer with His/Her Work : On Writing #70 : Susannah M. Smith : On Writing : On Writing #69 : Natalie Simpson : On Writing : On Writing #68 : Jennifer Kronovet : Fighting and Writing : On Writing #67 : George Stanley : Writing Old Age : On Writing #66 : George Fetherling : On Writing : On Writing #65 : Gail Scott : THE ATTACK OF DIFFICULT PROSE : On Writing #64 : Laisha Rosnau : The Long Game ; On Writing #63 : Arjun Basu : Write ; On Writing #62 : Angie Abdou : The Writer & The Bottle ; On Writing #61 : Carolyn Marie Souaid : Lawyers, Liars & Writers ; On Writing #60 : Priscila Uppal : On Creative Health ; On Writing #59 : Sky Gilbert : Yes, They Live ; On Writing #58 : Peter Richardson : Cellar Posting ; On Writing #57 : Catherine Owen : "Bright realms of promise": ON THE POETIC ; On Writing #56 : Sarah Burgoyne : a series of permissions-givings ; On Writing #55 : Anne Fleming : Funny ; On Writing #54 : Julie Joosten : On Haptic Pleasures: an Avalanche, the Internet, and Handwriting ; On Writing #53 : David Dowker : Micropoetics, or the Decoherence of Connectionism ; On Writing #52 : Renée Sarojini Saklikar : No language exists on the outside. Finders must venture inside. ; On Writing #51 : Ian Roy : On Writing, Slowly ; On Writing #50 : Rob Budde : On Writing ; On Writing #49 : Monica Kidd : On writing and saving lives ; On Writing #48 : Robert Swereda : Why Bother? ; On Writing #47 : Missy Marston : Children vs Writing: CAGE MATCH! ; On Writing #46 : Carla Barkman : Tastes Like Chicken ; On Writing #45 : Asher Ghaffar : The Pen: ; On Writing #44 : Emily Ursuliak : Writing on Transit ; On Writing #43 : Adam Sol : How I Became a Writer ; On Writing #42 : Jason Christie : To Paraphrase ; On Writing #41 : Gary Barwin : ON WRITING ; On Writing #40 : j/j hastain : Infinite Chakras: a Trans-Temporal Mini-Memoir ; On Writing #39 : Peter Norman : Red Pen of Fury! ; On Writing #38 : Rupert Loydell : Intricately Entangled ; On Writing #37 : M.A.C. Farrant : Eternity Delayed ; On Writing #36 : Gil McElroy : Building a Background ; On Writing #35 : Charmaine Cadeau : Stupid funny. ; On Writing #34 : Beth Follett : Born of That Nothing ; On Writing #33 : Marthe Reed : Drawing Louisiana ; On Writing #32 : Chris Turnbull : Half flings, stridence and visual timber ; On Writing #31 : Kate Schapira : On Writing (Sentences) ; On Writing #30 : Michael Bryson : On Writing ; On Writing #29 : Sara Heinonen : On Writing ; On Writing #28 : Stan Rogal : Writers' Anonymous ; On Writing #27 : Lola Lemire Tostevin : What's in a name? ; On Writing #26 : Kevin Spenst : On Writing ; On Writing #25 : Kate Cayley : An Effort of Attention ; On Writing #24 : Gregory Betts : On Writing ; On Writing #23 : Hailey Higdon : Hiding Places ; On Writing #22 : Matthew Firth : How I write ; On Writing #21 : Nichole McGill : Daring to write again ; On Writing #20 : Rob Thomas : Hey, Short Stuff!: On Writing Kids ; On Writing #19 : Anik See : On Writing ; On Writing #18 : Eric Folsom : On Writing ; On Writing #17 : Edward Smallfield : poetics as space ; On Writing #16 : Sonia Saikaley : Writing Before Dawn to Answer a Curious Calling ; On Writing #15 : Roland Prevost : Ink / Here ; On Writing #14 : Aaron Tucker : On Writing ; On Writing #13 : Sean Johnston : On Writing ; On Writing #12 : Ken Sparling : From some notes for a writing workshop ; On Writing #11 : Abby Paige : On the Invention of Language ; On Writing #10 : Adam Thomlison : On writing less ; On Writing #9 : Christian McPherson : On Writing ; On Writing #8 : Colin Morton : On Writing ; On Writing #7 : Pearl Pirie : Use of Writing ; On Writing #6 : Faizel Deen : Summer, Ottawa. 2013. ; On Writing #5 : Michael Dennis : Who knew? ; On Writing #4 : Michael Blouin : On Process ; On Writing #3 : rob mclennan : On writing (and not writing) ; On Writing #2 : Amanda Earl : Community ; On Writing #1 : Anita Dolman : A little less inspiration, please (Or, What ever happened to patrons, anyway?)

Published on October 05, 2015 05:31

October 4, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Lisa Marie Basile

Lisa Marie Basile

is the author of

APOCRYPHAL

, along with two chapbooks, Andalucia (Poetry Society of NY) and War/lock (Hyacinth Girl Press, February, 2015). She is the editor-in-chief of

Luna Luna Magazine

and her poetry and other work can be seen in PANK, the Tin House blog, Coldfront, The Nervous Breakdown, The Huffington Post, Best American Poetry, PEN American Center, Dusie, and the Ampersand Review, among others. She’s been profiled in The New York Daily News, Amy Poehler’s Smart Girls, Poets & Artists Magazine, Relapse Magazine and others. Lisa Marie Basile was the visiting poet at Westfield High School and New York University, and she was a visiting writer at Boston’s Emerson College. She was selected by Pulitzer Prize winner Robert Olen Butler for inclusion in the Best Small Fiction 2015 anthology and was nominated for inclusion in the Best American Experimental Writing 2015 anthology. She will be included Stay Thirsty Media's Best Emerging Poets 2014. She holds an MFA from The New School.

Lisa Marie Basile

is the author of

APOCRYPHAL

, along with two chapbooks, Andalucia (Poetry Society of NY) and War/lock (Hyacinth Girl Press, February, 2015). She is the editor-in-chief of

Luna Luna Magazine

and her poetry and other work can be seen in PANK, the Tin House blog, Coldfront, The Nervous Breakdown, The Huffington Post, Best American Poetry, PEN American Center, Dusie, and the Ampersand Review, among others. She’s been profiled in The New York Daily News, Amy Poehler’s Smart Girls, Poets & Artists Magazine, Relapse Magazine and others. Lisa Marie Basile was the visiting poet at Westfield High School and New York University, and she was a visiting writer at Boston’s Emerson College. She was selected by Pulitzer Prize winner Robert Olen Butler for inclusion in the Best Small Fiction 2015 anthology and was nominated for inclusion in the Best American Experimental Writing 2015 anthology. She will be included Stay Thirsty Media's Best Emerging Poets 2014. She holds an MFA from The New School. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?My first book, Andalucia (The Poetry Society of NY), was released in 2011 and is a chapbook of vignettes and poems. My first full/length, Apocryphal, came out last year (Noctuary Press). The two deal heavily in the interior-they are both working through loss. Both felt like they simply appeared in the world. My first chapbook made me confident that I could write, that it mattered, that beauty still mattered.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?I came to fiction first! I won 1st place fiction in my university's writing prize and I felt very odd about it. So I naturally came to poetry because my prose had an element of the nonlinear (non)space that I wanted to capture. 3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?It usually comes out very quickly (I don't write often). Then I edit quickly and it's done. I am not a lingering type. I let it go, for better or for worse.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?All of my work is part of a larger conceptual project. I don't write very many one-off poems. I am usually obsessed by one thing and it works itself into a larger project.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?I do give a lot of readings, but this is a very, very complicated question for me to try and answer. I took part in a production for many years in which we "performed" our poetry. The act element to it was alluring. Of course.

However, I am usually very bored at the typical brightly lit, too-long, podium readings. Or the crammed bars where people show up to be seen and not to listen. Not to mention poet voice. There is a lack of authenticity in both situations. But I get it. It's scary to be vulnerable. I suppose that is what troubles me.

But, when I walk into a room and I am able to be intimate and honest with the listeners without a mask, I feel good. When the listeners are invested in the poem, and there is a naturalness and not a forced show, it makes poetry a beautiful thing.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?I try to answer the question of honesty. It's hard to balance craft and sincerity. Or maybe it's the same thing. The current question, I think, is how to create a safe space in poetry. But I don't believe in poetry being the house for that safe space. I just don't. I think the safe space is created in the self when one's writing frees them, not necessarily when it creates safety for others.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?Absolutely. The writer creates other worlds. No human can live only in this world. We have imaginations, the ability to experience pleasure, we are haunted. Writing simply expedites all of it and gives it to you sooner.

I am not sure what our responsibilities are beyond that, but I like to think we are aiming to get people to think, feel and explore what it means to be alive now and always.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?I think there's a lot of benefit there, and the people who've helped me have really given me so much, but you have to trust your own voice first. Let people in if it feels right, but don't take all of their words to heart.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?To give the reader a path in and out, especially when you've created a world that has no footing.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?It has come very natural for me. I work in copy writing by day. I love to write. Form isn't, to me, a binding thing.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?I don't live a glamorous life that sees me writing in my gown all day. I have a day job. It is sad and horrific, but it's the truth, so I let the creativity in when I can. And when I do, it takes over me. And it doesn't matter how dull my days can be; I have a sort of divinity with me then.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?Anais Nin's diaries? Light. Space to work. Sex.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?I am actually a part-time fragrance writer, so this question is wonderful! I would say Yves Saint Laurent's Opium, as my mother loves it. It's dark, like black drapes, and very heavy, and intoxicating. Absolutely this.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?Definitely cinema! Uncomfortable, quiet films. I love to watch people who can really present authenticity in art.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?Anais Nin, Marguerite Duras, Violette Leduc. Recently I have read Lisa Ciccarello and I love her work so much. Lee Ann Roripaugh's Dandarians is killing me. I also adore Richard Siken and Molly Gaudry and J. Michael Martinez.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?Make short films based on poems or incorporating poetry.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?I would be a lawyer. I love arguing.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?Honestly, when I learned to write it seemed obvious to me to always do it. I don't think this world is enough for me.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?I am reading some cult book about poets called Lucinella by Lore Segal. It's amazing at depicting the shittiness and beauty of literary circles.

Film would be Interview with the Vampire. Watched it last night.

20 - What are you currently working on?A prose poetry novella with Alyssa Morhart-Goldstein. It is all I think about. It is going to really be murderous. 12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on October 04, 2015 05:31

October 3, 2015

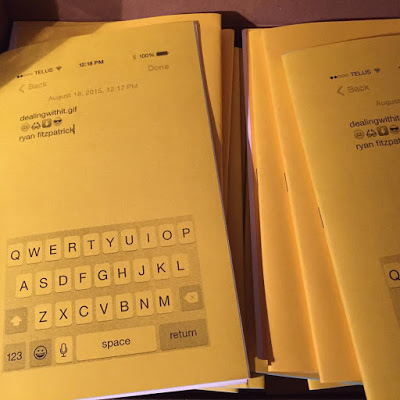

new from above/ground press: fitzpatrick, Prevost + Anstee,

culls

cullsRoland Prevost

$4

See link here for more information

dealingwithit.gif

ryan fitzpatrick

$4

See link here for more information

plus a "poem" broadside by Cameron Anstee! (to also appear soon on the above/ground press blog)

keep an eye on the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material;

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

September 2015

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

and don’t forget about the 2016 above/ground press subscriptions; now available!

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; outside Canada, add $2) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9 or paypal (above). Scroll down here to see various backlist titles (many, many things are still in print).

Review copies of any title (while supplies last) also available, upon request. See recent author backlist on the sidebar of the above/ground press blog.

Published on October 03, 2015 05:31

October 2, 2015

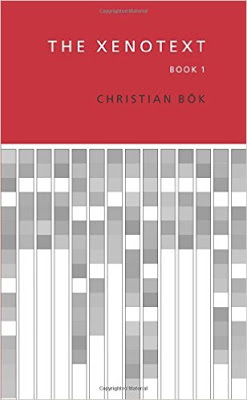

Christian Bök, The Xenotext Book 1

The Xenotextis an experiment that explores the æsthetic potential of genetics, making literal the renowned aphorism of William S. Burroughs, who claims that ‘the word is now a virus.’ Such an experiment strives to create a beautiful, anomalous poem, whose ‘alien words’ might subsist, like a harmless parasite, inside the cell of another life form. Many scientists have already encoded textual information into genetic nucleotides, thereby creating ‘messages’ made from DNA – messages implanted, like genes, inside cells, where such data might persist, undamaged and unaltered, through myriad cycles of mitosis, all the while saved for recovery and decoding. The study of genetics has thus granted these geneticists the power to become poets in the medium of life.

The Xenotextconsists of a single sonnet (called ‘Orpheus’), which, when translated into a gene and then integrated into a cell, causes the cell to ‘read’ this poem, interpreting it as an instruction for building a viable, benign protein – one whose sequence of amino acids encodes yet another sonnet (called ‘Eurydice’). The cell becomes not only an archive for storing a poem, but also a machine for writing a poem. The gene has, to date, worked properly in E. coli, but the intended symbiote is D. radiodurans (a germ able to survive, unchanged, in even the deadliest of environments).

A poem stored in the genome of such a resilient bacterium might outlive every civilization, persisting on the planet until the very last dawn, when our star finally explodes.

Book 1 of The Xenotext is an ‘infernal grimoire,’ introducing readers to the concepts for this experiment. Book 1 is the ‘orphic’ volume in a diptych about both biogenesis and extinction. The book revisits the pastoral heritage of poetry, admiring the lovely idylls that rival Nature in both beauty and terror. The work offers a primer on genetics while retelling fables about the futile desire of poets to rescue love and life from the ravages of Hell. All poets pay due homage to the immortality of poetry, but few imagine that we might write poetry capable of outlasting the existence of our species, testifying to our presence on the planet long after every library has burned in the bonfires of perdition. (“VITA EXPLICATA”)

Calgary poet and critic Christian Bök’s third poetry title—after

Crystallograpy

(Toronto ON: Coach House Press, 1994) and the Griffin Poetry Prize-winning

Eunoia

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2001)—is The Xenotext Book 1 (Coach House Books, 2015), the first volume of his long-awaited work of ‘living poetry.’ As the back cover informs: “Internationally renowned poet Christian Bök has encoded a poem (called ‘Orpheus’) into the genome of a germ so that, in reply, the cell builds a protein that encodes yet another poem (called ‘Eurydice’). After having illustrated this idea in E. coli, Bök is planning to insert his poem into a deathless bacterium (D. radiodurans), thereby writing a text able to outlive every apocalypse, enduring till the Sun itself expires.” It becomes fascinating how Bök has managed to construct poetry, let alone a multiple-volume project, around such an experiment, extending, exploring and capturing the connections between science and poetry dozens of times beyond what anyone has achieved up to this point, proving yet again just how far ahead he is of his peers. And of course, the notes at the end of the collection detail just how intricate some of the conceptual frameworks for some of the individual pieces were, including:

Calgary poet and critic Christian Bök’s third poetry title—after

Crystallograpy

(Toronto ON: Coach House Press, 1994) and the Griffin Poetry Prize-winning

Eunoia

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2001)—is The Xenotext Book 1 (Coach House Books, 2015), the first volume of his long-awaited work of ‘living poetry.’ As the back cover informs: “Internationally renowned poet Christian Bök has encoded a poem (called ‘Orpheus’) into the genome of a germ so that, in reply, the cell builds a protein that encodes yet another poem (called ‘Eurydice’). After having illustrated this idea in E. coli, Bök is planning to insert his poem into a deathless bacterium (D. radiodurans), thereby writing a text able to outlive every apocalypse, enduring till the Sun itself expires.” It becomes fascinating how Bök has managed to construct poetry, let alone a multiple-volume project, around such an experiment, extending, exploring and capturing the connections between science and poetry dozens of times beyond what anyone has achieved up to this point, proving yet again just how far ahead he is of his peers. And of course, the notes at the end of the collection detail just how intricate some of the conceptual frameworks for some of the individual pieces were, including:‘The Nocturne of Orpheus’ is a love poem – an alexandrine sonnet in blank verse. Each line contains thirty-three letters, and together the lines form a double acrostic of the dedication; moreover, the text is a perfect anagram of the sonnet ‘When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be’ by John Keats (transforming his meditation about the mortality of life into a mournful farewell by the poet before he enters Hell).

And:

‘The Nucleobases’ is a suite of poems derived from atomic models for the basic units of both DNA and RNA. Each text is a modular acrostic, in which the structure of a molecule defines the arrangement of a restricted vocabulary – only words of nine letters, beginning with one of the following: C (for carbon), H (for hydrogen), N (for nitrogen), or O (for oxygen). Each poem conveys a pastoral sentence about the honeybees (doing so in honour of Virgil – the first poet to have a line of poetry encoded into the genome of a flower)

There is something quite compelling in the way that Bök manages to compose his works with such attention to detail that the conceptual framework becomes simply an element of the appreciation of the finished piece. One doesn’t simply marvel at the conceptual frame; one doesn’t simply admire the work for work’s sake. And yet, the piece created utilizing such an intricate and detailed structure, especially when one begins to understand how detailed and precise his knowledge of scientific detail has been researched and questioned (there is nothing worse than a poem utilizing science when, as some have pointed out, the science behind the poem is actually incorrect).

We have seen it in the rope that hangs the felons, and we have seen it in the whip that goads the slaves. It has knit itself into a sylvan laurel, not unlike the diadem of dazzling moonlets that encompass the carousel of Saturn. It can circumnavigate a shooting star, en route to Alpha Lyræ. It can generate a gigantic field of magnetism so intense that, over time, its torsions interlace ephemeral filaments of stardust. It must crumple up the spiderweb of space-time, hauling it, like a trawl net, down into the mælstrom of a quasar. It must test itself, proving its intelligence by eternally replaying the same game of Glasperlenspiel upon an atomic abacus. It must calculate the odds of life delaying the doomsday of the universe. It is but a tightrope that crosses all abysses. It is but a tether that lets us undertake this spacewalk. Do not be afraid when we unbraid it.

We were never intended to be tied to whatever made us. (“Alpha Helix”)

In the pushing of boundaries of what constitutes a ‘poem’ or ‘poetry,’ there have been arguments against the idea of even referring to Bök’s work as ‘poetry,’ and yet, this is a language poetry deeply meshed with science as well as the lyric, even down to the deliberately Romantic framework of naming “Orpheus” and “Eurydice.” His engagement in this work with the lyric and pastoral certainly isn’t new – Eunoia does translate into “beautiful thinking” – but there feels a further element included in The Xenotext: creating a poem from a genome that is constructed to compose a further poem, and exploring the Romantic mode, as well as Romantic ideas of the poet itself, from Orpheus to Virgil, sonnets, the pastoral and the lyric, and the dedication at the offset: “for/ the maiden /in her / dark, pale meadow[.]” Somehow, through the workings of hard scientific study, Bök has managed to craft his most lyric work to date. Through exploring and engaging such classical ideas and ideals for poetry, Bök works in two directions simultaneously (akin to the work of Anne Carson): moving forward while engaging with some fairly basic ideas (and even presumptions) of poetic forms, somehow managing to point both elements into the same forward direction. Really, by engaging with some of the earliest works of poetry and science, one couldn’t do better than to refer to the Greeks (again, the word “eunoia,” which originates from a Greek word). Through the text and visuals of The Xenotext, Bök manages to not simply compose poems utilizing the language and information of science, but to make the two interchangeable: the science itself is the poem, and so on. Bök quite literally writes poems on the stars themselves, from and to whom the first stories were composed.

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is a chain of two extended, parallel polymers, aligned in opposite directions to each other but coupled at recurrent intervals so as to form a ladder, twisted around its long axis into a doubled, helical coil. Both polymers consist of repeating, molecular units called nucleotides. Each unit has a backbone made from a phosphate group, bonded to a molecule of 2-deoxyribose – a pentose sugar, to which is attached one of four nucleobases, donated by a single letter: A (for adenine), C (for cytosine), G (for guanine), or T (for thymine). Each constituent base in the sequence of one polymer conjoins with its codependent base in the sequence of the other polymer: adenine always links to thymine (A with T), and cytosine always links to guanine (C with G). Such linkages form the rungs in the helix. The information enciphered by the series of bases in a strand of DNA is read from the 5’-end to the 3’-end (from the fifth carbon atom to the third carbon atom) of each sugar. A set of three consecutive bases in a strand make a codon– a ‘word’ that can instruct a cell to create one of twenty amino acids found in all proteins.

DNA is an actual casino of signs, preserving, within a random series of letters, the haphazard alignment of acids and ideas. (“CENTRAL DOGMA”)

Published on October 02, 2015 05:31

October 1, 2015

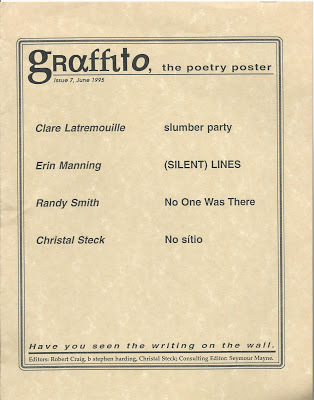

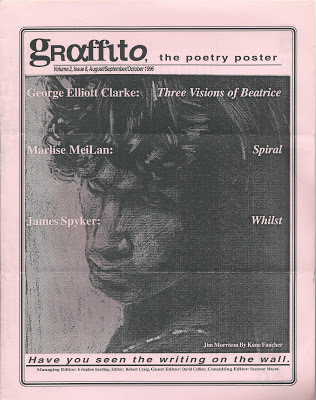

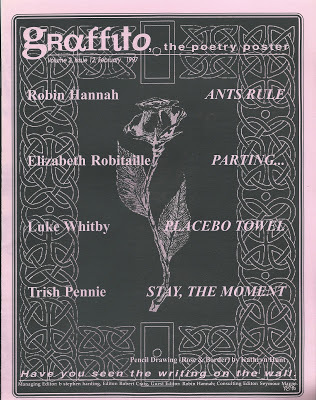

graffito: the poetry poster (1994-2000): bibliography, and an interview

this interview was conducted over email from August to September 2015 as part of a project to document Ottawa literary publishing. see my bibliography-in-progress of Ottawa literary publications,past and present here

A graduate of Seymour Mayne’s and the University of Ottawa’s Creative Writing Program, b stephen harding has published poetry in Bywords, Chasing Sundogs, Hook & Ladder, Ottawa Poets ‘95, Volume 1(audiocassette), Paperplates, and Remembered Earth, Volume 1 (Bywords), and is the author of the chapbook surcharges sometimes apply (Ottawa ON: Friday Circle, 1996). A former co-director of The TREE Reading Series, he was the founder, co-editor and managing editor of the monthly poetry broadside graffito: the poetry poster , a free poetry journal that existed in poster format, distributed monthly via bulletin boards across Ottawa (and worldwide, via Canada Post), as well as through electronic graffito , most of which is archived at the National Archives of Canada. Guest-editors for the series included Stephanie Bolster, Robin Hannah, rob mclennan, David Collins and Tamara Fairchild, with Robert Craig and Christal Steck serving as part of an informal editorial board, and Seymour Mayne serving as editorial advisor.

Q: How did graffitofirst start? I know there were at least a couple of you that had emerged from a creative writing workshop with Seymour Mayne at the University of Ottawa. What was it that prompted the creation of a monthly poetry publication?

Q: How did graffitofirst start? I know there were at least a couple of you that had emerged from a creative writing workshop with Seymour Mayne at the University of Ottawa. What was it that prompted the creation of a monthly poetry publication?A: graffito is your fault. Maria Scala and I were walking down Dalhousie St. and we saw one of your poetry posters. We both agreed that we could do something better. Not sure what happened next, but I’m guessing that we went to Seymour Mayne at some point and suggested graffito to him. Seymour was our Prof. of Creative Writing at the time. He liked the idea and got us the necessary resources i.e. access to free paper, and a place to do free photocopying at the University. It became a group project with Maria Scala, Robert Craig and Crystal Steck as joint editors.

Q: Were all four of you from the creative writing workshop? Was each issue edited as a group? How did you decide on the format of four or five poems per monthly issue, and how were they distributed?

A: All four of us where product of the Creative Writing program having taken both the beginner and advanced classes in poetry. In the beginning we edited the poster as a group. This would change over time. The size: well, I remember I wanted something bigger than 8x10 inches as I wanted it to have more than one poem, and wanting the visibility of a larger format to catch attention. Using tabloid size paper also folded well into 8x10 for mailing proposes. I’m not sure how we decided on 4 or 5 poems per issue, but we wanted to give as much exposure to poets as the size would allow. Distribution for all the run of graffito was me and my feet or via mail. I walked around the university into the market and up Bank St. as far as Billings Bridge Mall stapling posters on poles and in any shop, store or bar that would let me.

Q: What else was happening in Ottawa during the time you were producing graffito? What kind of reception did the journal have, whether in Ottawa or beyond?

Q: What else was happening in Ottawa during the time you were producing graffito? What kind of reception did the journal have, whether in Ottawa or beyond?A: I’m foggy on what was happening back then. There was a number of poetry readings including one I regularly attend at the Royal Oak on Laurier, TREE Reading Series, Dusty Owl; Bywords was being published as well. There was a lot more than this; the art scene was hopping back then. Robert Craig was hosting salon poetry readings in his apartment. I remember great poetry there and awesome Turkish coffees.

My general impression of the time was that Ottawa was the place to be if you were writing or an artist. As to what kind of reception graffito got, I’m not sure. I remember a couple of good reviews of it, but I think the kinds of poets that submitted to it say it was well received. graffitowas very limited in the beginning with only 50 copies to start and at its peak was 350 copies. It did get some international distribution over time. This was done by trading with other poets/writes or mags.

Bywordswas the poetry mag/events calendar and it was a definite influence on what graffito would be and become.

Q: At what point did you decide to turn graffito over to guest-editors and why?

A: That was more or less the result of editor fatigue. Also, the editors where moving on to other things at the time. Guest editors made sense to me as it was a way of including local poets. Getting other poetic views for the poster seemed a way to also keep the poster fresh and moving forward. For me it allowed more time for layout design and distribution, and networking with fellow poets, writers and editors.

Q: How involved were the guest-editors in soliciting work? What was the process of inviting and receiving submissions?

A: The guest editors had a free hand when it came to soliciting work. graffito got most of its submission based on word of mouth. It was also reviewed in a number of publications with helped get the word out.

Q: After four years of publishing, what do you feel graffito best accomplished? What were your frustrations?

A: My aim with graffito was to produce a vehicle that would give poetry a wider and diverse audience. I think we achieved that. The reality of a poster placed in public places is there is not a lot of feedback.

A: My aim with graffito was to produce a vehicle that would give poetry a wider and diverse audience. I think we achieved that. The reality of a poster placed in public places is there is not a lot of feedback.There were only a few frustrations... meeting deadlines, having enough quality poetry submissions to choose from, and all the walking required to get the poster out to its target audience. Oh, and then there was the funding, especially in the last 2 years.

Q: What happened to the funding? Is that the reason the publication finally wound down?

A: It wasn’t so much the funding as it was me winding down on the project. I was finding it harder and harder to meet my own deadline. I’d like to say it was more complicated than this, but in truth it wasn’t. From the point of view of the project it was fine, it had a constant stream of good to great submissions. There were some issues with attempting work by locals, and good poets to act as guest editor, but even that was not big enough to keep the project moving. In the end my shoulder was not strong enough to carry the project forward.

Q: What effect, if any, had graffito on the way you saw your own writing?

A: I would say that graffito had no effect on my writing. Well, that is not completely true. I would say it helped refine what I wanted my poetry to become.

graffito: the poetry poster bibliography:

Volume one, issue one. November 1994. Poems by Robert Craig, b stephen harding, Cherry Heard, Rocco Paoletti and Christal Steck.

Volume one, issue two. December 1994/January 1995. Poems by Claire Chippindale, Leila S. Goldberger, Seymour Mayne and Ros Ivan Salvador.

Volume one, issue three. February 1995. Poems by Adam Perry, Catherine Jenkins, Maria Scala and rob mclennan.

Volume one, issue four. March 1995. Poems by Micheal Abraham, Richard Carter, Tyson Dahlem, Joelle Kovach and Arturo Lazo.

Volume one, issue five. April 1995. Poems by Joe Blades, P.C. Chynn, Leonard Gasparini, Arthur Kill and Matthew Stanach.

Volume one, issue six. May 1995. Poems by Jill Battson, Richard Carter, Robynn Farrah Collins and Tamara Fairchild.

Volume one, issue seven. June 1995. Poems by Clare Latremouille, Erin Manning, Randy Smith and Christal Steck.

Volume one, issue eight. July 1995. Poems by Sylvia Adams, Scott Broderson, b stephen harding, Jim Larwill and Heather Tisdale-Nisbet

Volume one, issue nine. August 1995. Poems by Edward Jamieson, Jr., Christine Leger-White, Phil Mader, Sharon Ann Maguire and Patrick White.

Volume one, issue ten. September 1995. Special Edition: Haiku from the North American Haiku Convention. Poems by Winona Baker, Frances Mary Bishop, Marianne Bluger, Robert Craig, Garry Gay, LeRoy Gorman, Muriel Ford, Dorothy Howard, Marshall Hryciuk and Hans Jongman.

Volume one, issue eleven. October 1995. Poems by John Degen, Alan Cohol, Lea Harper and Stan Rogal.

Volume one, issue twelve. November 1995. Poems by Agatha Bedynski, Erin Gill, Susan L. Helwig, Daniel Nadezhdin and Ted Plantos.

Volume two, issue one. December 1995. Poems by Catherine Jenkins, John B. Lee, Daniela McDougall, Susan McMaster, Brian Pastoor and Louise O'Donnell.

Volume two, issue two. January 1996. Poems by P. Bainbridge, George Elliot Clarke, LeRoy Gorman and Robin Hannah.

Volume two, issue three. February 1996. Guest editor: Tamara Fairchild. Poems by Lynn Atkins, Eric Hill, rob mclennan and B. Z. Niditch.

Volume two, issue four. March 1996. Guest editor: Tamara Fairchild. Poems by Ronnie Brown, Joseph Dunn, S. Geddes, Janice Lore, John Rupert and Grimm Krowder.

Volume two, issue five. April 1996. Guest editor: Tamara Fairchild. Poems by Tamara Fairchild, Peter Layton, j. a. LoveGrove and P. A. Webb.

Volume two, issue six. May 1996. Guest editor: Tamara Fairchild. Poems by Seymour Mayne, Rocco Paoletti, John Rupert, James Spyker and b stephen harding.

Volume two, issue seven. June/July 1996. Guest editor: David Collins. Poems by Alan John Barrett, Cynthia Clarke, Adam Dickinson, Maggie Helwig and Stan Rogal.

Volume two, issue eight. August/September/October 1996. Guest editor: David Collins. Poems by George Elliot Clarke, Marlise MeiLan, James Spyker and Kane Faucher. Volume two, issue nine. November 1996. Guest editor: David Collins. Poems by p. j. flaming, Karen Hussey, Catherine Jenkins and Micheal Dennis.

Volume two, issue ten. December 1996. Guest editor: Robin Hannah. Poems by Kim Fahner, David Sutherland, Nevets Dier, R. M. Vaughan, Luke Whitby and Kathryn Hunt.

Volume two, issue eleven. January 1997. Guest editor: Robin Hannah. Poems by Charles Ardinger, jwcurry/gio.sampogona, Magie Dominic, Maria Scala and Kane Faucher.

Volume two, issue twelve. February 1997. Guest editor: Robin Hannah. Poems by Robin Hannah, Elizabeth Robitaille, Luke Whitby and Trish Pennie.

Volume three, issue one. March 1997. Guest editor: Stephanie Bolster. Poems by Errol Miller, Giovanni Malito, Emma Lew and Michelle Desbarats Fels.

Volume three, issue two. April 1997. Guest editor: Stephanie Bolster. Poems by Rebecca Comeau, Joanne Epp , Tamara Fairchild, Jim Larwill.

Volume three, issue three. May/June 1997. Guest editor: Stephanie Bolster. Poems by Sylvia Arnold, Richard Carter, Ken Cather and Myrna Garanis

Volume three, issue four. July/August 1997. Guest editor: allison comeau. Poems by Alan Cohol, Peter Bakowski, Pauline Gauthier and Emma Lew.

Volume three, issue five. September 1997. Guest editor: allison comeau. Jeff Bien issue.

Volume three, issue six. October/November/December 1997. Guest editor: allison comeau. Poems by Eirik, David Morris, Paula deArmas Looper and Greg Evason.

Volume three, issue seven. January 1998. Guest editor: Laurie Fuhr. Poems by Ben Ohmart, Jill Battson, Ken Norris, James Nordlund and Joan Pond.

Volume three, issue eight. February/March 1998. Guest editor: Laurie Fuhr. Poems by David Collins, Craig Carpenter, Bernadette Higgins, Timothy Hodor and Larissa.

Volume three, issue nine. April/May/June 1998. Guest editor: Laurie Fuhr. Poems by Stephanie Bolster, E. Shaun Russell, Gerald England, Laurie Fuhr and Zita Maria Evensen

Volume three, issue ten. 1999. Guest editor: rob mclennan. Poems by George Bowering, rob mclennan, Irene Parent, Dahlia Riback and Ian Whistle.

Volume three, issue eleven. 1999. Guest editor: rob mclennan. Poems by Robin Hannah, Natalee Caple, Jen Gavin and David W. McFadden.

Volume three, issue twelve. 1999. Guest editor: rob mclennan. Poems by Derek Beaulieu, Susan Elmslie, Ellen Field and George Elliott Clarke.

Volume four, issue one. 1999. Guest editor: jwcurry. Poems by jwcurry (uncredited).

Volume four, issue two. 2000. Guest editor: Gwendolyn Guth. Poems by Agustin Eastwood De Mello, Amber Hayward and Kenneth Tanemura.

Published on October 01, 2015 05:31

September 30, 2015

Rebecca Wolff, One Morning—.

One thing I’m not doing in my poems: reportingon anything that really happened.

When I say I’m from New York, Glaswegians say, “Oh, I love Woody Allen.” They cannot construe how large a state can be. I just happen to actually be from Manhattan. (“The Ungovernable”)

Albany, New York poet, editor and publisher Rebecca Wolff’s fourth poetry collection is

One Morning—.

(Wave Books, 2015), following her collections

Manderley

(University of Illinois Press, 2001),

Figment

(W.W. Norton, 2004) and

The King

(W.W. Norton, 2009). There seems something more open, and less constrained, in the poems of this collection—something to do with the breath—compared to the poems in her prior collection, a collection of poems on becoming and being a mother. Perhaps “constrained” isn’t the right word—but there is certainly something about the poems in this collection that is more open somehow, in the movement of line and breath. There is something less formal and more conversational, yet no less meticulously formed. As the poem “Palisades” opens: “Interred in region // nothing super global in this locale // where I live, where I / bought – // what would I tell you about it if I could?”

Albany, New York poet, editor and publisher Rebecca Wolff’s fourth poetry collection is

One Morning—.

(Wave Books, 2015), following her collections

Manderley

(University of Illinois Press, 2001),

Figment

(W.W. Norton, 2004) and

The King

(W.W. Norton, 2009). There seems something more open, and less constrained, in the poems of this collection—something to do with the breath—compared to the poems in her prior collection, a collection of poems on becoming and being a mother. Perhaps “constrained” isn’t the right word—but there is certainly something about the poems in this collection that is more open somehow, in the movement of line and breath. There is something less formal and more conversational, yet no less meticulously formed. As the poem “Palisades” opens: “Interred in region // nothing super global in this locale // where I live, where I / bought – // what would I tell you about it if I could?” Structured in six untitled sections, the poems in One Morning—. are engaged with structures and politics, and governing bodies and power (both real and perceived), delighting in odd flashes of wry humour combined with a lack of patience for nonsense. Her poems sever and subvert, shift and carve through the lyric without missing a beat or a step, composed without a wasted word or gesture. As she writes in the poem “Fronting”: “And I trust people // to make good choices / so I don’t have to impale them // on the tines of my pitchfork.”

Irony is the salt of life(I’d trade it in for gold)

Portaging takes a lot of timeand that’s how we are made

A morning’s worth of contretempsJapan has bigger tides

In sharing one finds extra peaceand this is what I’ll say:

“Oh, boil the cabbage down, girls”I’m on my way to work

At work I’ll find my head’s in useMore mountainsides en route

In view the smallest leaf, you knowmeasured by a glyph

your daughter’s facemy daughter’s face

I really mean my daughter’s face.

At one hundred and forty pages, One Morning—. has considerable weight, and the poems are incredibly sharp. There is something curious about the way Wolff utilizes “confession,” such as the poem/section “The Curious Life / and Mysterious Death / of Peter J. Perry.” She utilizes personal information to explore a series of interrogations, and even acknowledgments, to incredible degree, even as the fact of the information being factual as hers, or anyone elses (there is the suggestion that the narrator is related to Peter J. Perry, for example), becoming entirely beside the point. Her poems confess, and yet, remain private; what she gives away is far more valuable and far less tangible to track than whether or not a particular morsel of information really happened, and in the ways in which she informs. She is pointedly skilled at knowing exactly how and what to impart, and the reasons why, allowing her poems an intimacy that is deeply felt, without the distraction of the extraneous.

feeling it at the gas pumpfumes unchained

– I will report you –

squad car drove up my tailpipe

called my friendin

to see what he could do for us. (“Mad as Hell/Not Going to Take It”)

Published on September 30, 2015 05:31

September 29, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sasha Steensen

Sasha Steensen is the author of four books of poetry, most recently

House of Deer

(Fence Books), and Gatherest, forthcoming from Ahsahta Press. She lives in Fort Collins, Colorado, where she tends chickens, goats, bees, and children. Steensen serves as a poetry editor for

Colorado Review

and teaches Creative Writing and Literature at Colorado State University.

Sasha Steensen is the author of four books of poetry, most recently

House of Deer

(Fence Books), and Gatherest, forthcoming from Ahsahta Press. She lives in Fort Collins, Colorado, where she tends chickens, goats, bees, and children. Steensen serves as a poetry editor for

Colorado Review

and teaches Creative Writing and Literature at Colorado State University. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?At the time my first book (A Magic Book, Fence Books) was published, I was finishing up a PhD in the Poetics Program and I wasn’t sure what I would do or where I would go next. My husband and I thought we might travel for a few years or move to New York City or become gardeners and yoga teachers. But, with the book in hand, I ended up with a job at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. This is a town that welcomes a bit of amateur homesteading, and while I moved here with just my husband and a dog, I now have two daughters, three goats, 12 chickens, and the occasional hive of bees. In some ways, I think it is safe to say that the book made a path for me that I had not anticipated.

I wrote A Magic Book while preparing for my oral exams, and it was really a way for me to process the material I was reading. My first two books are probably more heavily researched, more concerned with a particular moment (A Magic Book—19th century American magicians and the second Iraq war) or movement ( The Method —the migrations of a manuscript written by Archimedes). Newer work (including House of Deer, also from Fence and Gatherest, which is forthcoming from Ahsahta Press) tends to find its way into more personal topics, more domestic spaces.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction? I actually wrote in all three genres when I was young, but the playfulness of poetry always appealed to me, and again, perhaps luck has a bit to do with it. While I was finishing up my BA in History, I took a poetry workshop with the poet Claudia Keelan. I had planned to go on to do an MA in American Studies, but Claudia insisted I could study history and write poems. She introduced me to Susan Howe’s work, and the following fall, I was one of two poets who enrolled in the newly formed MFA program at UNLV.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?It depends on the writing project, of course. I have noticed that I seem to average a book of poems every two to three years or so. With poems, I usually write about twice as many pages as I keep, and then there would also be a good deal of notes. I just wrote a long essay (“Openings: Into Our Vertical Cosmos,” forthcoming from Essay Press) that took me about three months, and again, the notes are much longer than the finished piece.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning? Rebecca Wolff once asked me if I ever just write a poem, and that’s when I realized that, in most cases, I start by working on a book and not on a discrete poem. But that has begun to shift a bit. While I am still working on serial poems, I don’t always have such a clear sense of what the larger book will look like until I have written several series. Series merge and books emerge.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?I love giving readings, especially when I get the chance to read with other writers whose work I admire. This has something to do with the fact that I don’t live in an urban setting, so if I am giving a reading, I am often traveling and talking to poets, something that tends to be very generative for me. And, sometimes I sing poems, sometimes I chant. I can’t do these things on the page in the same way. Performing poems feels a bit like re-embodying them.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?In some ways, the current questions are the same questions I’ve always asked, though the particulars are constantly shifting. I have always wondered what it means to be intimate with another human, to be in communion. Questions about the role language plays in our interpersonal relationships are endlessly fascinating to me. When I consider the ways in which this country suffers from deep-seated racism and violence, I think perhaps our failure to truly commune is at the heart of so many of our problems. Without the ability to connect, we bankrupt ourselves in so many ways—spiritually, ecologically, culturally and personally. What role does language play in creating or overcoming this bankruptcy? That is a question that keeps surfacing for me, though in different contexts.

I’ve written a good deal about addiction (especially in House of Deer) because I come from a family that has suffered from various kinds of addiction, and again, this question of communion is related. I recently read about a study in which rats were offered two kinds of water—untreated water and water laced with cocaine. The rats that had both cage mates and meaningful work (which, for rats, means play) rejected the cocaine-laced water in favor of the untreated water. When I read the article, I realized that despite all the thinking and writing I had done about addiction, I didn’t fully explore the ways in which a simple connection with another creature might serve as the most powerful antidote to drug addiction.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?I don’t think the writer serves one roll, and in fact, I’d probably be more inclined to say that each poem, as opposed to each poet, serves a function in the larger culture that we cannot do without. Some poems renew words by using them in unexpected or disarming ways, while other poems reproduce language, often to expose the ways language can be used to manipulate or placate us. Sometimes poems do both at the same time, and there are countless other functions a poem can serve. And then there are poems whose beauty moves me, and this is just as important, in my mind, as, say, the overtly political poem.

8- Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

So far, I’d say working with editors has been fruitful and pleasant. I have nothing but good experiences with editors. Hopefully that will continue!

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?In terms of the writing life, read more than you write.

In terms of the larger life (which includes the writing life, of course), I hesitate to admit that the best piece of advice comes in the form of a cliché, and it isn’t so much advice as prophecy. He who worries before it is necessary worries more than necessary. Whenever I find I am fearful or reluctant to do something because of some potentially disastrous outcome, this phrase comes to mind and I immediately remember a dozen or so instances in which I worried for no good reason. Then, the worry dissipates.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

I gave up writing prose (with the exception of a few short essays here and there) after I had my first daughter, and I have only just returned to writing longer essays now that my second daughter is in kindergarten. I didn’t have the mental space I needed to write essays until my children were in school full time. At the moment, I am at work on essays and poems, more or less equally, and I tend to go back and forth without much effort.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin? The first thing I do every day is milk a goat. I don’t write until my children are out of the house, and many days, I have to teach or I have meetings until they are out of school. So, writing happens once or twice a week, on the days I don’t teach. I do take notes off and on throughout the week, and occasionally, in the evening, I will sit down and work on something already in process. But for the most part, I need a few hours ahead of me, preferably earlier in the day as opposed to later, to get a good amount of writing done.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?The first and best answer is reading. But usually re-reading. When I am stuck, I tend to return to books that I admire. I’ve read Woolf’s The Waves over a dozen times because I adore it. I have always found that, in addition to writing, I need tactile work as well, so if I can’t write, I will often sew, knit, embroider, work in the garden, preserve food, cook, etc.

If I am in the middle of a project, or if I am in the process of trying to put a book together, I lean heavily on my husband. He studied poetry very seriously, but then he made a career change and went to law school. Talking to him is always very helpful for me because while he understands what I am working on, he has a completely different perspective on the questions I am asking. He often shows me new ways into the problems I want to address, and new ways out as well.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?My childhood home: bread.

My current home: Creek water. In the entryway of my house, there’s always a collection of buckets that serve as temporary homes for the crawdads, tadpoles and minnows my daughter catches in the canal that runs through our property.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?Visual art has always been hugely important to me. But now that I live out a ways, I turn more to the natural world and the domestic spaces where I spend most of my time. Animals, children, meditation and prayer are places I tend to find material.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work? I like the idea of answering this question in terms of writers I know—actual people. Of course, I could offer a long list of writers, living and dead, that I read and re-read, but it is wonderful to realize that some of those individuals on that list are people I see or correspond with regularly. I have amazing colleagues who are also friends—Dan Beachy-Quick and Matthew Cooperman. I am in regular contact with them not just because we work at the same institution, but because we read each other’s work, and take care of each other’s kids, and have dinner at each other’s houses. Other poets (some of who also live nearby) whose work and whose person are crucial for me: Julie Carr, Laynie Browne, Martin Corless-Smith, Aby Kaupang, Cathy Wagner, Claudia Keelan, and so many more.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?Walk or ride my bike some great distance—across the US, through South America, around Southeast Asia. Or even just complete a century (100 miles on the bike). I have ridden as far as 83 miles, so adding another 17 doesn’t seem too out of reach.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?Growing up, I wanted to be a pilot, but now I sometimes wish I had become a visual artist. I think I am guilty of romanticizing the artist studio. My husband and I use to fantasize about becoming travel writers for one of the budget travel guide companies. I’d still seriously consider leaving my academic job to write for Lonely Planet’s traveling with children series.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?My mother says I always wrote. Even before I could actually write words, I would dictate stories or poems and she would write them down. But, I think encouragement had a lot to do with it. Over the years, teachers took an interest in my writing, and gave me a sense that the writing life was a real possibility.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts just arrived in the mail yesterday and I stayed up way too late reading that last night. Even though I haven’t yet finished it, I am very moved by the ways in which she talks about transformation—of the body, of the family unit, of language, etc. I have also been devouring Karl OveKnausgaard’s Min Kamp books. My feelings about those books are so conflicted, and not for the reasons that some have cited (the title, the exposure of his loved ones). I am completely enamored with the ways in which the domestic landscape and the landscape of the mind meet and overlap. The conflict comes, I guess, when I think about all the women writers who have been doing similar work, in very different ways of course, but who have not yet received anywhere near the same kind of recognition. Take, for example, Bernadette Mayer who wrote her stunning Midwinter Day with her children present. American poets know and admire her, but I don’t think her work has had the audience it deserves. It could simply be the genre, but I do wonder if it has something to do with the interest we take in a man writing about the domestic.

Tangerines : A film about two men who stay behind to tend their land during the war in Abkhazia. Interestingly, this film features an absent woman too—the only woman in the film—who appears in a photograph and in conversation at a few crucial moments.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Speaking of the domestic life interfering with the writing life, for the first time since my first child was born (9 years ago!!!), I have many projects in the works. When my children were still very young and not in school, I seemed only able to work on one thing at a time.

I have just finished a few essays that are both personal essays and philosophical / etymological / historical meanderings on various topics. Going back to my earlier discussion about communion, the essays seem to be trying to figure out the ways in which affect determines our interactions with one another. For example, one of these essays deals with the experience of familiarity—how we know one another, how we recognize ourselves and each other as distinct creatures who are also defined in relationship. I have just started a third essay, on embarrassment.

I recently finished a book of poems entitled Gatherest that will be published by Ahsahta Press in 2017, and now I am at work on two additional poetry projects that may or may not merge. The first I am calling Hendes because the poems take their inspiration from Catullus’s Hendecasyllabic poems. Catullus’s form really can’t be translated into English because his meter depends on a series of long, short, and variable syllables. My adaption is a series of 11 line poems, each line consisting of approximately 11 syllables. Just as Catullus’s Hendecasyllabic poems start with a “sparrow, my girl’s pleasure,” my series begin with birds (chickens) and girls (my daughters) and pleasures (sex and food and affection). There are other contextual connections throughout, and my poems tend to meander toward and away from Catullus again and again as the series proceeds.

The second project is a rewriting of the history of the region where I live, and here I am trying to be as local as possible. I live on a little street off of a road called Overland Trail. The road gets its name from the fact that it was once the trail many of the pioneers took west during the 1800s. These prose poems utilize borrowed language from narratives and letters, particularly by women and girls, who were either on the wagons passing by the land where I now live or who stayed to settle it. But the poems are also concerned with contemporary daily and domestic life. I am interested in the convergence of notions of the land as something to settle, to cross over, to steal (from Native Americans), to take ownership of, and the land as a place we now inhabit without much thought. In these poems, the sense of the land as a stage upon which daily life is performed becomes subject to this older version of the land as something much more dynamic and volatile.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on September 29, 2015 05:31

September 28, 2015

12 or 20 (small press) questions with Maureen Scott Harris on Fieldnotes/MSH

I think of Fieldnotes/MSH as an imprint rather than a press, and myself as an amateur (in the root sense of that word) working on the margins of the small press world. Under this imprint I publish (erratically) occasional broadsides and chapbooks. The broadsides (so far) are my own poems and I circulate them to friends and colleagues to celebrate National Poetry Month. The chapbooks are prose, texts I’ve come across one way or another that I feel deserve an audience. Fieldnotes operates pretty much within the gift economy—chapbook authors get 10% of the print run. I try to recoup design and printing costs. If I do better than that the money goes towards the next publication.

Canadian poet and essayist Maureen Scott Harris was born in Prince Rupert (BC), grew up in Winnipeg (MB) and lives in Toronto (ON). She has published three collections of poetry: A Possible Landscape (Brick Books, 1993), Drowning Lessons(Pedlar Press, 2004) awarded the 2005 Trillium Book Award for Poetry, and Slow Curve Out (Pedlar Press, 2012), shortlisted for the League of Canadian Poets’ Pat Lowther Award. Harris’s essays have won the Prairie Fire Creative Nonfiction Prize, and the WildCare Tasmania Nature Writing Prize, which included a residency in Tasmania at Lake St. Clair. In 2012-2013 she was Artist-in-Residence at the Koffler Scientific Reserve at Jokers Hill, north of Toronto. With other poets and environmentalists she is currently plotting poetry walks that follow the (sometimes buried) rivers and streams of Toronto. Fieldnotes/MSH is her own enterprise.

1 – When did Fieldnotes/MSH first start? How have your original goals as a publisher shifted since you started, if at all? And what have you learned through the process?Fieldnotes began in January 2002 when I decided I wanted to publish a broadside of my poem “The Drowned Boy.” For some time I’d wanted to do something to mark National Poetry Month. I bought a big rubber stamp that says ‘National Poetry Month,’ stamped envelopes with it, and sent the broadside out to friends and colleagues. My initial intention was to publish a broadside every year for poetry month, but I only managed to keep it going for another year.

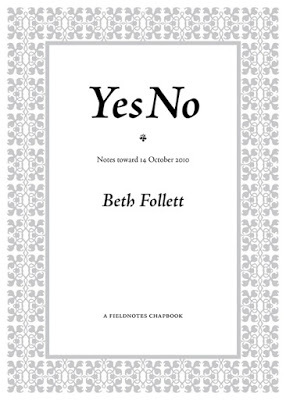

1 – When did Fieldnotes/MSH first start? How have your original goals as a publisher shifted since you started, if at all? And what have you learned through the process?Fieldnotes began in January 2002 when I decided I wanted to publish a broadside of my poem “The Drowned Boy.” For some time I’d wanted to do something to mark National Poetry Month. I bought a big rubber stamp that says ‘National Poetry Month,’ stamped envelopes with it, and sent the broadside out to friends and colleagues. My initial intention was to publish a broadside every year for poetry month, but I only managed to keep it going for another year. Then in 2010 I heard Pedlar Presspublisher Beth Follett speak in the Hart House Library (University of Toronto) about the future of the printed book and its readers. Beth is always eloquent. The audience was excited and inspired by what she had to say, but it wasn’t large. It seemed to me—and several others—that her talk should be published. I thought about it for a few days, and decided I could publish it as a Fieldnotes Chapbook.

I had no immediate intention of publishing anything more. But when Beth’s YesNoappeared and was launched people began to ask me what I’d publish next. I didn’t want to invest a lot of time in publishing and I don’t have a lot of money for it either, but I decided I would consider occasional publications, guided by my own responses to what I happened upon. I’m interested in talks and lectures, things that might disappear beyond their occasion. I’m also mainly interested in prose.

That said, the second Fieldnotes Chapbook was in fact a collection of poems written in response to a sculpture exhibition by Susan Low-Beer. It appeared in 2013. Fieldnotes came into that late in the game. With several other poets I’d been invited to view a series of Low-Beer’s sculptured heads and write something in response to them. The poems were assembled, edited, and the book designed when the group went looking for an ISBN. I was asked if it could appear as a Fieldnotes chapbook and said yes.

Late in 2014 I read an unpublished essay by Kelley Aitken about the Penone sculpture that once graced the Galeria Italia at the AGO. I’ve mourned that work’s disappearance, so I decided to publish the essay. It launched in January 2015. I’m now working on the next chapbook, Stan Dragland’s Page Lecture (delivered at Queen’s University about a year ago) on the poetry and prose of Joanne Page.

Last April I revived my poetry month broadside and I expect to publish another one in 2016. I’ve learned that it takes time and energy to publish, but it’s also satisfying. I expect Fieldnotes will publish erratically in the future as it has in the past. And it will continue, if it does, as I come across material that I think deserves an audience.

2 – What first brought you to publishing?I’ve been interested in small press publishing since the late 1960s when I was in what we then called library school. My favourite course, taught by Douglas Lochhead, was the history of books and printing. During it we pulled some prints on the Massey College presses. I also did a project on little magazines and literary ephemera for my humanities materials course. From a library standpoint such publications are hard to learn about and to collect; there was a growing interest in them that paralleled the growing interest in Canadian writing.

Much later, and for about 10 years, I worked at Robarts Library as the CIP librarian, doing the catalogue copy for forthcoming books; through that job I met many people in publishing. Then I worked for Brick Books as production manager for several years. Working for them I learned how small publishing unfolds and, given computers, it seemed pretty easy to make a broadside.

3 – What do you consider the role and responsibilities, if any, of small publishing?I think each small press must determine its own role and responsibilities. That said, I think the responsibilities fall in two directions: to the writer and to the reader. I want to produce chapbooks that embody or hold their texts appropriately and as beautifully as possible, in tribute to the work that goes into writing them—and I also want to extend the life of what might otherwise not be seen or heard.

4 – What do you see your press doing that no one else is?Hmmm—perhaps rejoicing solely in the serendipitous.

5 – What do you see as the most effective way to get new chapbooks out into the world?In my experience the launch of a chapbook is the most effective form of distribution. I believe attendance at small press fairs is also good, but as an introvert I find an afternoon of crowds completely exhausting and so don’t participate regularly. Word of mouth. I don’t use social media because I don’t know how to use it effectively, and I don’t want to spend time on it.

6 – How involved an editor are you? Do you dig deep into line edits, or do you prefer more of a light touch?It depends on how much editing the work requires. I’ve done both light and more involved editing.

6 – How involved an editor are you? Do you dig deep into line edits, or do you prefer more of a light touch?It depends on how much editing the work requires. I’ve done both light and more involved editing. 7 – How do your books get distributed? What are your usual print runs?Mostly by the launch, some by mail. My chapbook print runs have been 100 copies—though the Page Lecture will be 200.

8 – How many other people are involved with editing or production? Do you work with other editors, and if so, how effective do you find it? What are the benefits, drawbacks?So far I’ve worked directly only with authors and designers. I do the editing and copy-editing myself, though I sometimes consult with friends who have those skills. And of course I work with the printer.

9 – How has being an editor/publisher changed the way you think about your own writing?It’s shown me that I don’t necessarily have to wait on anyone else to publish something that I want to see published.

10– How do you approach the idea of publishing your own writing? Some, such as Gary Geddes when he still ran Cormorant, refused such, yet various Coach House Press’ editors had titles during their tenures as editors for the press, including Victor Coleman and bpNichol. What do you think of the arguments for or against, or do you see the whole question as irrelevant?Fieldnotes began as a vehicle to publish my own poems—though the poems I used for them had already appeared in journals. So I’m clearly not opposed to self-publishing. That said, I would in general prefer not to publish a chapbook of my own work, unless it was work that had been published elsewhere and so had the benefit of editing.

11– How do you see Fieldnotes evolving?I don’t see it evolving beyond what it is.