Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 364

November 6, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Matt Cahill

Matt Cahill

is a Toronto writer and psychotherapist. His debut novel,

The Society of Experience

, was released in October 2015 with Buckrider Books, an imprint of Wolsak & Wynn, and was listed on the Harper’s Bazaar Top 15 Must-Read Books fall list. His short story, Snowshoe, was published in 2014 with Found Press. He previously worked for 20 years behind the scenes of the Canadian film/TV industry.

Matt Cahill

is a Toronto writer and psychotherapist. His debut novel,

The Society of Experience

, was released in October 2015 with Buckrider Books, an imprint of Wolsak & Wynn, and was listed on the Harper’s Bazaar Top 15 Must-Read Books fall list. His short story, Snowshoe, was published in 2014 with Found Press. He previously worked for 20 years behind the scenes of the Canadian film/TV industry.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Well, technically this is my first published novel, but my second book; my previous book was thrown into a virtual fireplace otherwise it would have taken up too many fruitless years. That said, writing the first book was proof that I could write a book, and thus dispense with the annoying adage “anyone has one book in them.” I have two! The book that’s out now (Oct 1) is more mature, but also more complex. Your first book tends to have A LOT OF EMOTION IN IT, DAMMIT. In this book I learned how you can convey the same thing but without excessive sturm und drang.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

By imitation. My brother wrote a double-sided one page short story when I was around 11. I couldn’t believe someone could just create a whole universe like that. I was hooked. That said, I occasionally write poetry.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

There’s usually a main path that comes out without too much difficulty, however the story which ultimately supports that path tends to come with patience and development, and sometimes accident. Sometimes a piece of narrative rebar from an abandoned short story becomes a central turning point for a novel. I don’t like to leave good ideas laying around unused.

4 - Where does a work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I usually know early on if what I’m doing is novel-worthy. You don’t want to stare down five years with something that doesn’t have the sea legs for that kind of adventure.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I kind of like doing readings, and I’m pretty good at bringing life to the words in front of a microphone. That said, public readings take me away from writing more than anything else. They are necessary for promotion - particularly allowing people ready access to the work without them first purchasing it - but readings have nothing to do with writing.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Nope. I mean, I probably do on a less-than-conscious level, but I don’t think I would want to write from a self-directed agenda. In general, I like to poke at the complexity of life and the ways that we end up becoming more accurate reflections of ourselves - for better or worse.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think one important part we play is to allow anyone in the world to know that they are not alone. We write to share. There are many roles that writers can play. I’m equally happy to entertain, or inform, or challenge.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

In general, an editor is essential because you’re not going to catch everything, especially in a novel where there is more continuity to oversee. A good editor wants what you’ve written to be the best that it can be, knowing that it needs to reflect the strengths and promise of your intent. A bad editor is going to take your pen and go “You should do this [insert something writer wouldn’t write] because I think it works better,” without the opportunity for dialogue.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Paul Vermeersch said to me "Something has to happen in a scene,” which he heard earlier from someone else. It’s easy to write scenes where two people are earnestly talking, but if it’s just dialogue then it just doesn’t read off the page very well - it seems incomplete. It’s easy to forget setting, mood, and story when you’re hyper focused on a shiny bit of character-revealing dialogue. Have someone fixing a clock, or brushing something out of their hair, or thinking about picking up groceries. Something has to happen in a scene.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to the novel to essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

Each serve their purpose. Short stories are a stomping ground of experimentation - I get to play with voice and perspective, sometimes subject matter. Essays allow me to speak personally about something, and back that up with research and reason. Novels are marathons of imagination which require stamina and self-reflection. Writing in these different formats doesn’t automagically make you a “good writer,” but I’ll admit that it certainly contributes to an overall flexibility that I wouldn’t necessarily have if, say, I only wrote novels.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

By any means possible. Typically weekends, but sometimes I just grab my notebook or my laptop and leave without care for day or time. You have to carve out the space because no one is going to hand that to you. You have to claim it as yours and fight for it.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

In no particular order: music, film, dance, visual art, newspapers, doing the dishes, long walks.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I moved a lot when I was a kid, so I don’t really have that. Fragrance is extremely evocative. The other day while I was on a morning run, the doors to a local public school were open while people were loading in equipment, and I immediately picked up smells that I haven’t come across in decades: glue, ink, craft paper, cleaning products, arts supplies. A part of me stayed behind and sat on the floor of that school hallway and didn’t want to leave.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Everything. It sounds trite, but life is my notebook. I’m a tourist/alien. I take interest in everything around me. Why wouldn’t you?

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

My philosophy is “read widely” as opposed to being “well-read”. If all we do is read The Classics - when we don’t really play a part in how that mantle is bestowed - then that brings us closer to monoculture, which is terrible. I read what interests me, even if it’s flawed. Also, more and more I ask myself where my blindspots are. For example, am I reading too many books by white men? Am I only getting North American perspectives?

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d like to write about the film/TV industry in a way that is both honest and compassionate. Too often it’s Day Of The Locust and Swimming With Sharks, or The Player. Yes, there is bone-headed self-destructive bullshit in that industry…but that doesn’t make it unique. There is depth, too.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Assuming this isn’t my only book or accomplishment as a writer, it will be my third career. I’m perfectly happy with where I am in my life, work wise. My psychotherapy practice offers relief from the very internal, anti-social nature of writing.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

A clinical supervisor cautioned me early in my psychotherapy practice about over-pathologizing why people chose the vocations they had. “After all,” she said, “we sit and talk to people for a living - what’s with that?"

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Thomas King’s The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America. I’ve seen so many middling films recently, but Force Majeure was very interesting. It’s the sort of movie where you want to have a discussion with whoever is sitting next to you immediately after you see it.

20 - What are you currently working on?

A sequel to The Society of Experience . Also, a novel about someone cursed with magic. I’m not sure which child will get fed first, but there are worse problems to have.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on November 06, 2015 05:31

November 5, 2015

Reviewers on Reviewing: mclennan, Webb-Campbell, Marchand, Zomparelli + Del Bucchia

At Erin Wunker's request, I recently wrote a short blurb on why reviewing matters for the CWILA site, posted this week alongside similar pieces by Shannon Webb-Campbell, Philip Marchand, Jonathan Ball and Daniel Zomparelli and Dina Del Bucchia.

At Erin Wunker's request, I recently wrote a short blurb on why reviewing matters for the CWILA site, posted this week alongside similar pieces by Shannon Webb-Campbell, Philip Marchand, Jonathan Ball and Daniel Zomparelli and Dina Del Bucchia.As Wunker writes over at Facebook:

Reviewing as feral practice, as the strike-out and slow carve. Reviewing as necessary in a world where books seem to matter less and less. Reviewing as joyful dissent and a refusal to be 'boring as fuck.' Check out what Shannon Webb-Campbell, rob mclennan, Jonathan Ball, Daniel Zomparelli & Dina Del Bucchia, and Phillip Marchand have to say about why book reviews matter.

Have thoughts of your own? Send me a message and we can get your views on why you review up at CWILA's Reviewers on Reviewing site!

Published on November 05, 2015 05:31

November 4, 2015

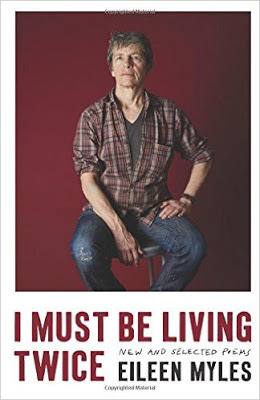

Eileen Myles, I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems

AUTUMN IN NEW YORK

It’s something like returning tosanity but returningto something I havenever known likea passionate leafturning greenAugust almost gone“—that’s my name,don’t wear it out.”As if I doffedmy hat & founda head orhad an ideathat was alwaysminebut just camehome, the balloonsare going by sofast. I lean onbuttons accidentallyjam the workswhen I simplyam thisgreen.

With the publication of

I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems 1975-2014

(Ecco, 2015), as well as the reissue of her 1994 novel, Chelsea Girls (Ecco, 2015), New York poet Eileen Myles is enjoying a bit of a renaissance lately. Not that she’s been silent for any extended stretch, having published “nineteen books of poetry, criticism, and fiction,” but, as she says to headline a recent interview in New Republic: “I’m the Weird Poet the Mainstream Is Starting to Accept.” Basically, Myles is a writer that other writers have known about for decades, finally, as the stories suggest, moving into a larger and broader readership. Much of Myles’ work explores the line between fiction and memoir, utilizing elements of personal detail, in varying degrees of alteration. Often more straightforward, and sometimes deceptively so, her poems engage with elements of narrative, the lyric, performance, meditation, social and political commentary, the confessional and the short story, all of which she presents as “the poem.” When reading through this collection, I can see very much how some of these poems would have fit perfectly being performed at the late lamented CBGBs, where her first readings were held in the 1970s. As the New Republic interview informs us: “Eileen Myles seems to come from a New York that no longer exists. Her first reading took place at CBGBs, she lived four floors below Blondie, and contemporaries with Richard Hell, progenitor of the spiky-haired, torn-suit jacket look.” That might all read as a tad romantic, and even sensational, but hers has been a New York also populated by Ted Berrigan, Alice Notley, Kathy Acker, Chris Kraus, John Ashberyand Charles Bernstein, among so many, many others. A recent interview over at Electric Lit (an interview worth reading in its entirety), explores her frustrations with accessibility and readability, the limitations of form, and the limitations of naming form:

With the publication of

I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems 1975-2014

(Ecco, 2015), as well as the reissue of her 1994 novel, Chelsea Girls (Ecco, 2015), New York poet Eileen Myles is enjoying a bit of a renaissance lately. Not that she’s been silent for any extended stretch, having published “nineteen books of poetry, criticism, and fiction,” but, as she says to headline a recent interview in New Republic: “I’m the Weird Poet the Mainstream Is Starting to Accept.” Basically, Myles is a writer that other writers have known about for decades, finally, as the stories suggest, moving into a larger and broader readership. Much of Myles’ work explores the line between fiction and memoir, utilizing elements of personal detail, in varying degrees of alteration. Often more straightforward, and sometimes deceptively so, her poems engage with elements of narrative, the lyric, performance, meditation, social and political commentary, the confessional and the short story, all of which she presents as “the poem.” When reading through this collection, I can see very much how some of these poems would have fit perfectly being performed at the late lamented CBGBs, where her first readings were held in the 1970s. As the New Republic interview informs us: “Eileen Myles seems to come from a New York that no longer exists. Her first reading took place at CBGBs, she lived four floors below Blondie, and contemporaries with Richard Hell, progenitor of the spiky-haired, torn-suit jacket look.” That might all read as a tad romantic, and even sensational, but hers has been a New York also populated by Ted Berrigan, Alice Notley, Kathy Acker, Chris Kraus, John Ashberyand Charles Bernstein, among so many, many others. A recent interview over at Electric Lit (an interview worth reading in its entirety), explores her frustrations with accessibility and readability, the limitations of form, and the limitations of naming form:Before I was really writing I lived in Cambridge with friends after college. One day I went to Dunkin’ Donuts for a cup of coffee and the guy next to me just turned and started unloading his mind completely. There was no civilized introduction, no nothing. He was completely crazy but what was really astonishing was how seamless it was. I try to kind of do that. The most interesting moment in The Bell Jar is when they take the famous poet out to lunch and he sits there quietly eating the salad with his fingers. The narrator concludes that if you act like it’s perfectly normal you can do almost anything. John Ashbery said he writes as if he’s in the same room as the person who’s reading the poem. For example, if I wanted to describe…well that wainscoting I’d just begin right there: “I’m not sure how i feel but the black next to it is actually really great.” What it creates is a feeling of intimacy, if a reader will go with it. A lot of fiction makes narrators that just happily give it up! They show all the scenery, the whole plodding entrance. I’d call them “obedient narrators”. I don’t ever want to write an obedient narrator. I want you to have an actual relationship with the narrator.

This is only the second title I’ve seen of hers, after the more recent Snowflake: new poems / different streets: newer poems (Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Poetry, 2012) [see my review of such here], but the poems in I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems allow the reader the possibility of seeing across four decades of her published poetry. Bookending the collection with “New Poems” and an “Epilogue,” the collection includes selections from The Irony on the Leash (1978), A Fresh Young Voice from the Plains(1981), Sappho’s Boat (1982), Not Me (1991), Maxfield Parrish (1995), School of Fish (1997), Skies (2001), On My Way (2001), Sorry, Tree (2007) and Snowflake / Different Streets (2012). What is curious is in seeing how the precision and rush of the pieces in the “New Poems” section are comparable to poems throughout her published work; Myles’ work has evolved, and honed over the decades, but the precision, energy and rush of her lyric, and the subtle shifts of tone and tenor of her lines, remains throughout. She knew what she was doing very early; she knew what she was doing, and pushed the boundaries while keeping her writing centred around an essential core of her narrative/meditative lyric.

WOO

out in a bus stopamong themountainsa yawn, boy drive byblue mountainslittle tan mountainhouse, similareach scapeis all its own placeno womanis like anyother

Still: given the heft of such a collection, at nearly four hundred pages, why not include an introduction? (I don’t understand any selected/collected poems that doesn’t include an introduction.) She does, at least, include a short essay-as-epilogue, an essay that works through considerations of narrative, genre and form; an essay that opens with her poem “What Tree Am I Waiting” and poet Dana Ward, who caught sight of it in the online journal Maggy, and offered praise:

His explanation of why my poem was important to him was like balm to my ears. He wrote:

To hear someone arrive with that purpose & then put it right there, getting out of the way of everything else to get it right to the top of the thought & the poem. That’s the best stuff in the world to me, that sound. It seems harder than ever to do, or I’m confused right now somehow, regardless, it just tolled in the room for me.

This was huge praise from someone whose work I currently adore. I was pee-shy too about my own poem in particular because it was too emotional. How will it be received. Dana did refer to his own piece in Maggy as “a poem” which intrigued me cause it looked like prose. It’s prose in a world in which I’ve never really noticed whether people describe Bernadette Mayer’sinfluential early works “Moving” and “Memory” as poetry or prose. Didn’t she call it writing. I mean I think even for Lydia Davis genre is like gender in the poetry world. I’m remembering Amber Hollibaugh explaining gender this way once. It’s not what you’re doing, it’s who you think you are when you’re doing what you’re doing. So prose writers in the poetry world always felt less like prose writers to us, more like fellow travellers and someone like Bernadette was probably writing poems that looked like prose, or like Lydia, prose in the poetry world which for a while at least adds up to the same thing. She was a fellow traveller for a time, and still is, truly, though she’s also everyone’s now. John Ashbery’s greatest book I think is Three Poems which certainly looks like prose. So if Dana Ward wants to call his prosey looking stuff a poem it probably has more to do with how he feels about the work. Or whose he thinks it is. When I read it, it’s mine for sure.

Published on November 04, 2015 05:31

November 3, 2015

new from above/ground press: Price, Christie + Touch the Donkey,

The Charm

The CharmJason Christie

$4

See link here for more information

Sickly

Katie L. Price

$4

See link here for more information

Touch the Donkey #7with new poems by Stan Rogal, Helen Hajnoczky, Kathryn MacLeod, Shannon Maguire, Sarah Mangold, Amish Trivedi and Suzanne Zelazo.

[keep an eye on the Touch the Donkey blog for upcoming interviews with a variety of contributors!]

$7

See link here for more information

and watch the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material;

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

October 2015

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

and don’t forget about the 2016 above/ground press subscriptions; still available!

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; outside Canada, add $2) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9 or paypal (above). Check the sidebar of the above/ground press blog to see various backlist titles (many, many things are still in print).

Review copies of any title (while supplies last) also available, upon request.

Published on November 03, 2015 05:31

November 2, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Anne Gorrick

Anne Gorrick [photo credit: Peter Genovese] is a poet and visual artist. She is the author of:

A’s Visuality

(BlazeVOX Books, Buffalo, NY, 2015),

I-Formation (Book 2)

(Shearsman Books, Bristol, UK, 2012),

I-Formation (Book 1)

(Shearsman, 2010), and

Kyotologic

(Shearsman, 2008). She has co-edited (with Sam Truitt) In|Filtration: An Anthology of Innovative Poetry from the Hudson River Valley (Station Hill Press, Barrytown, NY, 2015).

Anne Gorrick [photo credit: Peter Genovese] is a poet and visual artist. She is the author of:

A’s Visuality

(BlazeVOX Books, Buffalo, NY, 2015),

I-Formation (Book 2)

(Shearsman Books, Bristol, UK, 2012),

I-Formation (Book 1)

(Shearsman, 2010), and

Kyotologic

(Shearsman, 2008). She has co-edited (with Sam Truitt) In|Filtration: An Anthology of Innovative Poetry from the Hudson River Valley (Station Hill Press, Barrytown, NY, 2015). She has collaborated with artist Cynthia Winika to produce a limited edition artists’ book called “Swans, the ice,” she said with grants through the Women’s Studio Workshop in Rosendale, NY, and the New York Foundation for the Arts. She has also collaborated on large textual and/or visual projects with John Bloomberg-Rissman and Scott Helmes.

She curated the reading series, Cadmium Text ( www.cadmiumtextseries.blogspot.com ) and co-curated (with Lynn Behrendt), the electronic journal Peep/Show at www.peepshowpoetry.blogspot.com

Her visual art can be seen at: www.theropedanceraccompaniesherself.blogspot.com

Anne Gorrick lives in West Park, New York.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book taught me think in books. After Kyotologic came together with Shearsman in the UK, it got easier to think of my work as clustering, hivelike pieces. The real estate of a book, that possible space makes one less sensitive to limits. It also brought me out of almost total writing isolation.

The consecutive books so far aren’t exactly consecutively written. My second book has some of my earliest work in it, work that embraced a complex long form I keep playing with: to break numerous pieces apart and reattach them. It’s like Isis looking for parts of Osiris. That’s my poem-making.

My latest book, A’s Visuality, out from BlazeVOX, continues a formal and spacial poetic inquiry, and language might occasionally turn into paint. This book really attempts to sew together the textual and visual, and includes color plates of two of my artist’s books that ended up generating the first half of the book.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I’ve been writing poetry since I was a kid, not even really knowing what poetry was yet, but the scratch of the pen on paper was everything I ever wanted. Now it feels like poetry is my personal Hadron collider - I think up these extravagant ways to collect text, smash the particles together, and hope for some new thing I never knew before. There’s the sense that when I do this, that language is coming to tell me something, what it knows. Lately, my work is getting more sentence-y, so who’s to say it doesn’t at some point morph into fiction. Diana Vreeland, when asked if her stories were fact or fiction, said they were “faction.” Not sure where the line is between poetry and fiction. Now I’m thinking hard about the word “depiction.”

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I’ve always had to work pretty fast, because I don’t have a huge luxury of time. Think: working full-time in educational administration; serving as President of Century House Historical Society and its Widow Jane Mine; being married to a lovely being; that on top of my art/writing life. Usually a writing project becomes apparent pretty quickly - an inquiry will turn vast. I’ll find a way of searching, noticing, manipulating text in such a way that I don’t want to stop until I’ve used it up. I’ll often have elaborate worksheets of source text that I create at the beginning, but then the poem jumps out of it pretty quickly to me. I liked frayed edges, deckles, so I don’t overwork things. It bugs me when things are too smooth.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I can see a book now pretty early on (i.e. some technique I want to explore until I’m done). I’ve completed a manuscript of poems about perfumes that combine various poetic manipulations into one work, instead of keeping processes separate. This seems like a huge leap in my own poetic, generative process, due partly to a collaboration and friendship with poet John Bloomberg-Rissman. Anything goes with John, so this was a great teaching for me. “Scorn nothing,” John would say and attribute this to poet Robert Kelly.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I had to learn how to give readings, and now I enjoy them. I curated a reading series called Cadmium Text for seven years. I like readings as a forum to test drive new work, hear what my friends are doing, hopefully hear something that blows me away. I’m half-introvert, so I have to push myself sometimes out the door to engage.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

The cartoon idea of quantum physics, that particles can be many things at once, in many places at once, strikes me as something to strive for: a quantum poetics. That language can mean and dart multiply. The internet has primed us to be more associative, more able to make thought leaps easily. We live in a time more complex than our language is capable of holding. Can language be made more pliable, more plastic to better suit our world? It’s almost a moral quest: to mean in many directions, and to mean complexly.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

My practice is almost one of finding sites of ruin porn - to play with the shambles left to us, a parking garage made out of a theatrical palace. A reviewer in the UK said that my first book was more like graffiti on palace walls. I took this as such a compliment. I wrote a poem once that said “This is a poem for a small and skeptical audience / It’s about vajazzling AND Paul Celan“ I want the high and low world in my work. All of it. Vajazzling AND Paul Celan. To put the world in. Poetry is our Hadron collider - we can find the tiny particles that compose our culture, find new ways to mean multiply at once.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It’s always been interesting. I don’t find that people want to change my work too often, but I’m usually curious and interested to see other ways forward. I might not adopt that direction, but it’s fascinating, and I appreciate being read deeply.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I’ve always cherished a letter that Ted Hughes sent to Anne Sexton in regard to listening to critics and reviews: “They tend to confirm one in one’s own conceit—unless they praise what you yourself don’t like. Also, they make you self-conscious about your virtues. Also, they create an underground opposition: applause is the beginning of abuse. Also, they deprive you of your own anarchic liberties—by electing you into the government. Also, they separate you from your devil, which hates being observed, and only works happily incognito.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to visual art)? What do you see as the appeal?

I’m lucky to have a pretty broad creative continuum, mostly shuttling between writing, visual art, gardening and now perfume and its making. If I get sick of one thing, I can always go do something else. Even if it’s tedious. Digging holes for 20 Rose of Sharon bushes is pretty boring, but also an investment in future beauty. Or digging holes for 150 peonies.

Many years ago, I threw poetry out of the house like a bad boyfriend, yelling at it from upstairs windows and chucking its clothes on the lawn. I was tired of poetry’s limit to a 8 ½” x 11” page. So damn tired of it. I broke up with poetry and I started to learn traditional Japanese papermaking, printmaking, indigo dyeing and encaustic painting. It helped break through the ice dam of the traditional page and let me range over larger spaces. Of course poetry came crawling back, apologizing. And I took it back into my house.

My last visual art project was a series of 30+ encaustic monotypes, worked over in pastel based on deceptively simple photographs of Luis Barragán’s architecture. His work is so spare and lush at the same time. I’m a maximalist, so it’s fun to lay in the sun of his opposite light.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

From 2008 until 2014, I got a lot of work done. I could spend up to three days a week at my writing/visual practice, from a few hours to much more if I felt like it. It was good to write in the morning. My life is different now. Less time, new job, a recently herniated disc in my neck that makes sitting for long periods difficult. Finishing my latest book used up some bandwidth, as well as completing the editing with poet Sam Truitt for our new book In|Filtration: An Anthology of Innovative Poetry from the Hudson River Valley, due out this summer from Station Hill Press.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Since 2010, I’ve kept a notebook of poem ideas, fun things to search and make poems, notes, diagrams. Anytime I’m stuck, I can turn to it because the book grows faster than I can write. I also have some long term projects that I can turn to and pick up the thread when I’m stalled.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Great question because I’m crazy for perfumes! The smell of the ocean reminds me of lost home (At the Beach 1966 by CB I Hate Perfume). My house smells like the grassy paws of a dog (Grass by CB I Hate Perfume), woodstove smoke (Burning Barbershop by D.S. & Durga), flowers I drag in (Carnal Flower by Frederic Malle), wet dirt (Black March by CB I Hate Perfume), firewood (Cambodian oudh), snow that gets stuck in boots (yes, snow has a smell). My husband builds and restores old race cars, so he’s got this terrific motor oil, exhaust thing I love. That’s true home.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes, everything we pour into ourselves becomes food for the work. That’s why I’m sort of careful about what I pour in. Not a lot of junk food anymore. I hike. I read a ton of non-fiction. I make visual art.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

To write, I need to move. Until recently I studied tennis and played it seriously, this beautiful physical chess. Now I hike and bike. Writing is very physical to me, and I need to be able to do it.

Sooooooo many writers have filled my head. A very partial list might include Nabokov early on. The Situationists. Dada (Tristan Tzara was my first poetic love). The Pillow Book of Sei Shonogon . Susan Howe. Robert Kelly. Carole Maso. Anchee Min. Leslie Scalapino. Laura Moriarty (both - the painter and the poet). Work by friends over the years like: Maryrose Larkin, Elizabeth Bryant, Geof Huth, Nancy Frye Huth, Lynn Behrendt, Teresa Genovese, Cynthia Winika, Scott Helmes, John Bloomberg-Rissman, Reb Livingston, Michael Ruby, Sam Truitt, Lori Anderson Moseman…

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

It’s fun to dream aloud, if aloud is a lit screen.

I’m undertraveled. I’d like to walk the Camino de Santiago. I’d like to visit Grasse. The burial mounds of Ohio. India!

Writing-wise, I’ve got several long projects that are somewhere on the continuum of complete: a long work on the American desert, a project working with an essay by John Burroughs (my dead neighbor), a project writing into an unpublished manuscript by Eileen Tabios.

There are some encaustic teachers I’d like to study with.

I’d like to make a film. It might have snow and people wrapped in saran wrap.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Poetry isn’t an occupation for me. As far as I can tell, it isn’t really an occupation for anyone. Although I’d love to live in a world where I could afford to do it all the time.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It was inevitable. I never got to choose.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus by Charles C. Mann and La Grande Bellezza.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I spent the summer finishing edits on a few of manuscripts that were 90% done. I will co-curate with poet Melanie Klein a new reading series in 2015-2016 called Process to Text, which will bring adventurous writing to beginning poets at the local college where I work. There’s a long manuscript I pick up and put down where I’m writing into work by Eileen Tabios. Trying to heal up my back issues, but I see now this will take a long time. Started studying qigong, which seems to be helping. There are some ashes right now. I’m injured and curious to see what happens next.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on November 02, 2015 05:31

November 1, 2015

Cole Swensen, LANDSCAPES ON A TRAIN

Green. Cut. And I count: the green of the lake the green of the sky and the field

Which is green and breaking. Waking out of an opening, a sudden field opens

Out with a suddenness that instantly places us miles away across a field of wheat.

The publicity for American poet, editor and translator Cole Swensen’s LANDSCAPES ON A TRAIN (New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2015) reads:

Influenced by the history of landscape painting, Cole Swensen’s new book is an experiment in seriality, in the different approach and scope that language must take to record the way that fluctuations of minutiae transform a whole. These poems meditate on what it is simply to look at the world, without judgment, without intervention, without appropriation. Swensen’s lyric observations, lilting and delicate, distill the act of seeing.

The author of more than a dozen poetry collections, Swensen has long favoured constructing poetry collections around a central theme or thesis, from hands to gardens to ghosts. What might have been explored through a more expansive detail in previous works, Swensen’s touch across the poems of LANDSCAPES ON A TRAIN display a lighter touch. One might suggest that this is less a book about capturing the shifting views of landscapes than about describing the interplay of light across a screen, canvas or window. Through her lines, light shifts, shimmers and alters, refusing to remain static.

An extended meditation constructed out of fifty-eight untitled, unnumbered prose-poems, each accumulated section of

LANDSCAPES ON A TRAIN

suggest a series of quick notes composed during travel, capturing the details of landscape in the smallest brushstrokes, and held together to build into an essay on landscape and light around landscape painting during the Romantic (and even late Medieval) period.

An extended meditation constructed out of fifty-eight untitled, unnumbered prose-poems, each accumulated section of

LANDSCAPES ON A TRAIN

suggest a series of quick notes composed during travel, capturing the details of landscape in the smallest brushstrokes, and held together to build into an essay on landscape and light around landscape painting during the Romantic (and even late Medieval) period.Light slices across the tops of trees. White light cuts the presence back. The lack

Thereof. Light replaced. Light that is an approach. That we can’t see the light enter

The cells of the trees, not what leads, the path down to the cells below the trees.

This collection is slightly reminiscent of another of her ekphrastic works, her Such Rich Hour (University of Iowa, 2001), which wrote around a fifteenth-century book of hours, the Trés Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. As she wrote in her “Introduction” to that collection:

The poems that follow begin as a response to this manuscript, and specifically to the calendar section that opens this and all traditional books of hours. The calendar lists the principal saints’ days and other important religious holidays of the medieval year in a given region. In keeping with the cyclical rhythm of a calendar, the poems follow the sequence of days and months and not necessarily that of years.

Poems titled the first of a given month bear a relation to the Trés Riches Heures calendar illustration for that month, though they are not dependent upon it. Rather, they – like all the pieces here – soon diverge from their source and simply wander the century. And finally, they are simply collections of words, each of which begins and ends on the page itself.

Swensen seems very drawn to exploring human responses to the world, whether the Victorian-era development of the garden, medieval sketches of the human hand, ghost stories around an English village or, in this current work, the Romantic period of landscape portraits: each consideration depicting a response to and removal from the original subject. It is not the subject she is attracted to, but how those particular subjects are seen, understood and described. As she writes further on in the collection, “The unfurled sight of empty paths.” She discusses her approach to subject with Andy Fitch in a recent interview:

Andy Fitch: Could we first contextualize Gravesend amid a sequence of your research-based collections? Ours , for example, comes to mind. What draws you to book-length projects, and do you consider them serialized installments of some broader, intertextual inquiry? Does the significance of each text change when placed beside the others? Or do they seem discrete and self-contained?

Cole Swensen: They revolve around separate topics, yet address the same social questions: How do we constitute our view of the world (which, of course, in turn constitutes that world), and how does the world thus constituted impinge upon others? Ours examines an era in which science put pressure on definitions of nature. We cannot pinpoint when such pressures started, but 17th-century Baroque gardens give us a chance to focus on this pressure and question the accuracy and efficacy of making a distinction between science and nature in the first place.

[Skype glitch]

In short, both books question how we see, and how this shapes the world we perceive. Ours examines 16th– and 17th-century notions of perspective in relation to conceptions of scientific precision, knowledge, beauty and possibility in Western Europe. Gravesend poses quite different questions, foregrounding that which we do not, or cannot, or will not see. Certain passages address this directly, such as “Ghosts appear in place of whatever a given people will not face.” Communal guilt and communal grief remain difficult to acknowledge because our own lines of complicity often get obscured. Perhaps our inability to deal directly with such guilt and grief causes them to manifest in indirect forms. The English town of Gravesend offered a site through which to examine this because it can be read as emblematic of European imperialist expansion—a single port through which thousands of people emigrated, scattering across the world, creating ghosts by killing cultural practices, individuals, and in some cases, whole peoples. But the word “Gravesend” also hints at an after-life, a life that exceeds itself. The town of Gravesend stands at the mouth of the Thames. When people sailed out of it, they cut off one life and began another. So the concept of a grave as a swinging door seemed crystallized by the history and name of this town. And ironically, the first Native American to visit Europe, i.e., to have gone willingly (even before Columbus, many had been kidnapped and brought back to Europe, but), the first who seems to have regarded it as a “visit,” died in Gravesend, as she waited for a ship to take her back to Virginia. The New World, the Western hemisphere, finally capitulates to Europe, and dies of it.

Published on November 01, 2015 05:31

October 31, 2015

A short profile on The Peter F. Yacht Club

My short profile on

The Peter F. Yacht Club

(an irregular publication through above/ground press) is now online at Open Book: Ontario, with input from Laurie Anne Fuhr, Anita Dolman, Vivian Vavassis, Peter Norman, Amanda Earl, Peter Richardson, Wes Smiderle, Janice Tokar, Pearl Pirie, Cameron Anstee, Ben Edgar Ladouceur and Marilyn Irwin.

My short profile on

The Peter F. Yacht Club

(an irregular publication through above/ground press) is now online at Open Book: Ontario, with input from Laurie Anne Fuhr, Anita Dolman, Vivian Vavassis, Peter Norman, Amanda Earl, Peter Richardson, Wes Smiderle, Janice Tokar, Pearl Pirie, Cameron Anstee, Ben Edgar Ladouceur and Marilyn Irwin.

Published on October 31, 2015 05:31

October 30, 2015

a new poem up at our teeth

Published on October 30, 2015 05:31

October 29, 2015

Chaudiere Books Fall Poetry Launch! Weaver, Londry, Turnbull + Hawkins; November 28, 2015 at The Manx

The Writers Festival is pleased to be hosting a special Fall launch for Ottawa’s own Chaudiere Books!

The Writers Festival is pleased to be hosting a special Fall launch for Ottawa’s own Chaudiere Books!

Co-publishers rob mclennan and Christine McNair, have another great slate of books coming your way! Join us for readings and launches by Andy Weaver ( this ), Chris Turnbull ( continua ), Jennifer Londry ( Tatterdemalion ) and William Hawkins ( The Collected Poems of William Hawkins ).

Published on October 29, 2015 05:31

October 28, 2015

Joseph Massey, Illocality

POLAR LOW

Half-sheathed in icea yellow double-wide trailer

mirrors the inarticulate morning.The amnesiac sun.

And nothing elseto contrast these variations of white

and thicketchoked by thicket

in thin piles that dim the perimeter.

Every other nounfreezes over.

On the heels of his California trilogy comes American poet Joseph Massey’s fourth poetry title, Illocality (Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2015). His previous collection, To Keep Time (Richmond CA: Omnidawn, 2014) [see my review of such here], was the “third and final book grounded in the landscape and weather of coastal Humboldt County, California, and contains the last poems I wrote there before moving to the Pioneer Valley of Massachusetts in the winter of 2013.” As the press release for this new title informs: “Joseph Massey composed Illocality in his first year in Western Massachusetts. Massey’s austere landscapes channel the quiet shock, euphoria, and introspection that come with reorientation to place.” Illocality is a sequence of exploratory moments composed in short bursts, as Massey attempts to locate himself in the physical and philosophical spaces that make up his new geography, although one that seems devoid of human interaction.

The world is realin its absence of a world. (“TAKE PLACE”)

His short, precise lines echo William Carlos Williams and Robert Creeley, but place themselves in entirely different ways: the physical shapes of his immediate physical environment. And Pioneer Valley (especially during the winter) is very different than Humboldt County, California. As he writes in the poem “PARSE”: “This rift valley // A volley of / seasonal beacons // Window / where mind // finds orbit [.]” Where Williams and Creeley included the domestic and other other human interactions in their precise explorations (that included geography and the physical landscape), Massey’s poems allow for the suggestion of human presence without any kind of direct interaction. Where are all the people in Pioneer Valley?

His short, precise lines echo William Carlos Williams and Robert Creeley, but place themselves in entirely different ways: the physical shapes of his immediate physical environment. And Pioneer Valley (especially during the winter) is very different than Humboldt County, California. As he writes in the poem “PARSE”: “This rift valley // A volley of / seasonal beacons // Window / where mind // finds orbit [.]” Where Williams and Creeley included the domestic and other other human interactions in their precise explorations (that included geography and the physical landscape), Massey’s poems allow for the suggestion of human presence without any kind of direct interaction. Where are all the people in Pioneer Valley?ROUTE 31

Yellow centerlinesplit with roadkill.

First day of summer—I’ve got my omen—

the clouds are hollow, rovingabove a parking lot.

Each strip-mall pennant blurred.

So much metalshoving sun

the sun shoves back.

Massey’s invocations of the natural world are often in parallel, or even in conflict, with the human world: “the sun shoves back.” His is an uneasy balance between the two. Logics of the natural and human elements of the geography collide, and become illogical, creating their own set of standards, logics and rules, all of which he attempts to track, question and even disentangle. As he writes in the extended sequence “TAKE PLACE”:

As if a field guidecould preventthe present

from disintegratingaround us.

Published on October 28, 2015 05:31