Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 361

December 5, 2015

Ongoing notes: the ottawa small press book fair (part three,

[Stuart Ross digging through recent titles by Invisible Publishing]See part one here and part two here. Oh, I picked up so many amazing things at the most recent ottawa small press book fair (although I seem to have missed a few things, including new publications by In/Words and The Ottawa Arts Review…).

[Stuart Ross digging through recent titles by Invisible Publishing]See part one here and part two here. Oh, I picked up so many amazing things at the most recent ottawa small press book fair (although I seem to have missed a few things, including new publications by In/Words and The Ottawa Arts Review…).Kemptville ON/Iceland: I’m very pleased to have a copy of Chris Turnbull and a rawlings’ remarkable collaboration, The Great Canadian (2015), produced in a limited edition by Low Frequency. As their web page states:

The Great Canadian is a medium-bending collaborative effort between poet a rawlings and photographer Chris Turnbull. With images from their collaboration for Turnbull’s ongoing, site-specific rout/e project and text from rawlings’ forthcoming echolology, as well as a q-code link to a recording of rawlings reading an excerpt of the text, The Great Canadian represents an intersection of multiple trajectories. The work dances one-sided on and beyond the margins of 23 unbound 7”x7” sheets of translucent vellum, packaged in a letter-pressed brown-bag envelope.

The project is basically the point at which their two separate ongoing projects meet [see my write-up earlier this year on Turnbull’s ongoing project at Jacket2, as well as a link to her brand new poetry title], and the results are quite stunning. Both poets utilize text and image in a deep engagement with ecological concerns, as well as directly engaging with nature. As Turnbull writes as part of the publication:

The project is basically the point at which their two separate ongoing projects meet [see my write-up earlier this year on Turnbull’s ongoing project at Jacket2, as well as a link to her brand new poetry title], and the results are quite stunning. Both poets utilize text and image in a deep engagement with ecological concerns, as well as directly engaging with nature. As Turnbull writes as part of the publication:a rawlings’ echolological poem, “The Great Canadian” was planted in snow along the Rideau Trail (Merrickville, ON Map #13) in 2011. For the first two kilometres, the trail hosts piles of 0:05-0:13 garbage—mattresses, old wood, junk, baby materials, clothing, bottles of the unknown. To the east 0:23-0:37, is a pile of construction materials and household items, to its 0:48, piled mattresses with a variety of junk on top. By 2012, a trail-user had moved [ it ] within a window frame that had become base and frame for the collection of tires, containers, bottles, pieces of wood, and “The 1:53-2:49. An archive. During spring melt, 2013, [ it ] floated in a deep, ATV-created large puddle—the plexiglass muddied, the paper undamaged. Spring 2014—[ it ] was floating again, slippery, so I leaned it in a safe place above the waterline. By the time of autumn 1:002014, an unknown trail-user ha re-replaced the poem; the window frame functioning again as base and frame for a collection of tires, containers, bottles, pieces of wood, and “The Great Canadian.”

[ it ] offers a statement subject to its own ruination: “I will not ruin the environment.” The poem degrades over time: in written form, exposed to external conditions, as voiced utterance seeking and losing meaning and context, and as auditory experience, internalized or heard, temporary. a rawlings’ release of “The Great Canadian” for rout/e, the involvement of an unknown caretaker of the poem and trail, and the development and production of a chapbook with Michael Flatt & Low Frequency Press, charts extended, intriguing, and unforeseen collaborations. The chapbook combines an assortment of rawlings’ page-based variants on her initial text (forthcoming in her manuscript-in-progress echolology) with sited visuals of “The Great Canadian.” [ Here ], “The Great Canadian” reforms as a transforming eyed-object predicated upon an unknown series of linguistic relationships and soundings (echolology). The chapbook is archival, the poem is vanishing from the site of the trail, echolology is emergent.

You really need to get a copy of this. In many ways, it has to be seen to be believed.

Ottawa ON: The Sourdough Collaborations: poems and discussion by Roland Prevost and Pearl Pirie (Phafours, 2015) contain exactly what the title describes: a conversation between two Ottawa poets on their collaboration as it is happening, using the poems as examples of what they are working on together. I saw an earlier version not that long ago appear in filling Station magazine and was intrigued, but there is something of the conversation as a whole that is both really interesting, and almost distracting: there is something about the poems that I would like to see on their own, as well, without the conversation about them wrapped around my experience of reading. As they write, “How can we explore recipes for making new?”

2. likewise (Pirie)

this call should be transferred.not counting. not counting. knot.

if someone is chewing loudly,eat them to hide the noise.

almost the same as perfume;how a basket of peaches muffles a room.

watch out for too many keys;also, for old Portuguese proverbs.

lens caps are accepted in the forest.silicon earth is a better terrazzo.

anyhow it’s much worse to live in fear.I know an awe fantasy. one is right here,

training time. mares learning harness are small-eared.flying bats are high fashion designers.

so, what are the differences between a cat’s coats?oh, all that devour our mind’s nimble legs.

The conversation begins around a poem that Pirie composed, and furthers into how she begins by ‘translating’ the poem through various means, to compose a new piece. From that point on, Prevost takes Pirie’s response, and works his own variation on ‘translation,’ which leads Pirie to respond to Roland’s response, and so on (including a collaborative translation), until fourteen poems in total are created. They run the poem through online translations, working small edits as they go. Over the past decade or more, both Ottawa poets Pirie and Prevost have been engaged in conversations and writing-as-study on poetic language, structure and possibility, so to see them in conversation with each other on collaboration seems a logical step in their ongoing processes.

Prevost on the process of making poem 9: After many wild permutations, it seemed appropriate to imitate a less wild poem, while at the same time, keeping to the subversive premises of our play.

Over the longer view of the series, there’s a sound shift across poems. As you’ll see scope becomes scape. It later became nodding onion as we go across slant rhyme and slant meaning. It tantalizes in the attempt to ‘signify’ something grander, but it’s just play on the previous text, with more like the spirit of a telescope haunting the piece like a ghost. If you peg down a single thought and wrap everything around it, an odd kind of focus ensues. For ironic fun, the pegged idea here is the fog of distance.

There was a pause of a few months. How to find the rhythm again? Pirie ran Langues Imaginaires thru Dutch then did a naïve homophonic translation to English. A story was mixed in (of rigidity vs blue ocean, blue ocean) because story is more memorable than randomness.

Part of what intrigues about this publication is in seeing the nuts and bolts of how the two of them worked the collaboration, and seeing how, through the very nature of producing the publication the way that they have, the process of this particular collaboration is more important to either of them than the finished product. I mean, the results of their work is almost pushed aside, not allowed to be experienced on its own terms. It does make me curious to see if this is simply one of what might be a series of collaborations they end up working on together over the next few months or years. As fascinating and engaging as seeing their process is, I want to be able to read the result without having to know everything about how they got there; at least, not until later.

Published on December 05, 2015 05:31

December 4, 2015

Hook & Ladder (1993-8): bibliography, and an interview

this interview was conducted over email in October-November 2015 as part of a project to document Ottawa literary publishing. see my bibliography-in-progress of Ottawa literary publications, past and present here

Victoria Vernell lives; loves; and waits for the Doctor in the suburbs of Ottawa, Ontario. She is a decaffeinated mother of three teenagers and doesn’t go downtown nearly often enough for a cup of Bridgehead. Two cats keep her mindful of her position on the food chain, and two large dogs guarantee that a house is not a home without small piles of randomly shed fur about the place.

A writer from an early age, Victoria has published poetry in small press publications including Quills (2008), and Jones Av.(1996). There’s a poetry manuscript or two that needs completion, but in the meantime you can read her nonfiction work at her two blogs Taking The Mother Road and Whovian On A Budget.

Q: How did

Hook & Ladder

first start? I know there were at least a couple of you that had emerged from a creative writing workshop with Seymour Mayne at the University of Ottawa (the same class, I believe, that prompted b stephen harding and Maria Scala to found graffito:the poetry poster). What was it that prompted the creation of a new journal?

Q: How did

Hook & Ladder

first start? I know there were at least a couple of you that had emerged from a creative writing workshop with Seymour Mayne at the University of Ottawa (the same class, I believe, that prompted b stephen harding and Maria Scala to found graffito:the poetry poster). What was it that prompted the creation of a new journal?A: Ah, yes. We were young and full of gumption. Looking back, we were aware of Arc and its ties to Carleton University, Ottawa U had Bywords, and your above/ground press had just begun producing broadsheets, etc. For myself, since I can’t speak for my co-editors at the time - Robin Hannah and Alexander Monker, who were also part of Seymour Mayne’s poetry workshop that year - I wanted something that transcended existing literary cliques and made local poets of all levels of experience feel encouraged to submit their work for publication.

Q: What were your models when starting out? Were you basing the journal on anything specific, or working more intuitively?

A: I liked the look of Arc . A mini book you could carry around with you and fit into a purse or backpack.

I guess in its way we were of the “no school like the Old School” mindset as far as design. I had a copy of Aldus (? – later Adobe) PageMaker installed on my parents’ computer and I was a high-level font collector, and taught myself how to do the layout.

As for the selection process, we all tended to favour a similar style of writing. We weren’t looking to reinvent the wheel and were always mindful that people were giving us their money to do this, either through direct sales or subscriptions, so we wanted to give them a quality product on every level, within our collective ability to provide it.

Q: What was the process of putting together those first few issues? Did you have an open call for submissions, or were you soliciting work?

A: When H&Lstarted, we intentionally kept our net cast within Ottawa and Eastern Ontario. We didn’t have the budget or the distribution network to take it much further, as it didn’t receive government arts funding until years later, from the City of Ottawa; and we felt that between the two universities plus the literary reading series (Tree, Sasquatch, BARD, Vanilla/Vogon, to name a few) we would have a strong pool from which to solicit submissions. I was also a full-time undergraduate student studying English Lit at Ottawa U, so I was able to get us a mail slot in the English Department as an address, which may have helped with cachet. That was the extent of the university’s concrete support of the magazine.

I was adamant that my name would only appear in H&L as a byline on book reviews. I sent out letters to small presses across the country requesting review copies. Most were pleased to oblige.

As for the selection process, whoever was on the editorial board at the time would get together as a group and go through the submissions one by one. Eventually we worked up the nerve to send poems back to their originators with comments. Payment was two contributor copies.

Q: Why were you, as you say, adamant your name only appear as a byline?

Q: Why were you, as you say, adamant your name only appear as a byline?A: Good question. I was unable to see the value in my own work. I could not be objective and impartial and make that distinction between myself and my poetry.

It was less demanding to find the merit in others’ work because I had no personal investment in it.

Q: Did this change at all over time? What effect, if any, had Hook & Ladder on the way you saw your own writing?

A: Yes, it did. It bears mentioning that depression and anxiety and every dark corner those two mental illnesses encase all but silenced me for approximately 12 years, during which time I also got married and had three children with complex medical issues; and I eventually got divorced. I didn’t start writing again until 2006, and went to some workshops. The last time I read in public was in 2007.

I was lucky also to meet someone who was very supportive of my writing and keeps poking at me to do more. These days my output is mostly online with two non-literary blogs, but I have never lost a love for books and printed zines and I want to concentrate more on the literary form that ignited H&L’s creation 22 years ago.

Q: What kind of reception did the journal have, whether in Ottawa or beyond?

A: I would say the response was positive, overall. We had our critics of course but our decision to stop publishing after a five year run had nothing to do with that. My children became my focus and I built my life around them, as the song goes. But when H&L was active we all strongly believed in what we were doing and it was a great learning experience on many levels.

Q: What prompted the decision to finally suspend publication? Was it simply a matter of shifting priorities?

A: Babies and bills. And back then due to undiagnosed depression and anxiety I was a lousy juggler, worse still at asking for help, and expert in pushing people away – usually people I cared about. After I came to terms with those things, I was of the mindset that I had to give 100% of everything to motherhood, so I did what I thought was best for the sake of my domestic life at the time. It isn’t coincidence that I began writing again and pursuing publication after my divorce.

Q: You mention Alexander Monker and Robin Hannah as co-founders/co-editors. Was the collaboration between the three of you an equal partnership, and were they both there during the entire run of the journal? How were either of them involved in the decision to suspend publication?

Q: You mention Alexander Monker and Robin Hannah as co-founders/co-editors. Was the collaboration between the three of you an equal partnership, and were they both there during the entire run of the journal? How were either of them involved in the decision to suspend publication?A: Robin, Alexander, and I were the team behind most of the first issue of H&L. Alexander was dropped from the masthead prior to the launch of the first issue, to paraphrase the late Irving Layton, because Robin and I jointly decided that Alexander’s devotion to the project wasn’t perfect. Difficult to pin down for meetings, etc. I remember Robin’s partner at the time, Sean O’Neil, came on board and helped with content selection.

It was Robin and I who put out the second issue. My university classmate Kim McNeill joined us for the third issue, and I believe it was around that time that Robin and I severed ties and she eventually moved back to Toronto.

If we are going to talk about personal or professional regrets, my biggest was losing her. She was (is) an amazing writer and knew her stuff. To the best of my awareness she published her chapbook with above/ground press and a collection with Broken Jaw Press and nothing since.

At the time H&Lceased publication, I was also building a reading series and a chapbook press under the name Electric Garden. Kim had moved on, and my ex-husband briefly joined creative forces with me, which was not without its negative consequences.

As I said previously, it was a valuable learning experience on many levels. The fallout is not something I wish to revisit.

Q: Looking back on the journal now, how successful do you feel you were in your original goals? What do you feel were the biggest accomplishments of Hook & Ladder?

A: At its peak, it was great fun. I still get a great chuckle from the memory of you, Warren Dean Fulton, and I, sandwiched in the back of my parents’ minivan with our boxes of publications, heading down to Toronto at some ungodly early hour to attend CanZine at the Spadina Hotel. Do you still have that coffee cup from the Denny’s in Kingston?

I think H&Lachieved what it set out to do. I tip my hat to the people who are still in the game. For me there will always be something about the printed zine that is timeless and needs to continue.

Hook & Ladder bibliography:

Hook & Ladder bibliography:Volume one, issue one. Spring/Summer 1993. Editors: Robin Hannah, Sean O’Neil, Victoria Vernell. Managing Editor: Victoria Vernell. Poems by Matthew Barlow, Andrew Milne, Sylvia Adams, Kimberly J. McNeill, Barbara Fras, Robin Hannah, Seymour Mayne, J.D. Boyes, rob mclennan and Robert Craig. Review by Victoria Vernell.

Volume one, issue two. Fall/Winter 1993-1994. Editors: Robin Hannah, Victoria Vernell. Managing Editor: Victoria Vernell. Poems by Tony Cosier, B. Stephen Harding, Michael Abraham, Kimberly J. McNeill, E. Russell Smith, Dan Doyle, Colin Morton and Juan O’Neill. Review by Victoria Vernell.

Volume one, issue three. Summer Solstice 1994. Editors: Robin Hannah, Kimberly McNeill, Victoria Vernell. Managing Editor: Victoria Vernell. Poems by Seymour Mayne, Allison O’Shaughnessy, Warren Layberry, Cindy Upton, Juan O’Neill, Rob McLennan, David W. Henderson, Shel Krakofsky, Ciaran O’Driscoll, Joy Hewitt Mann, E. Russell Smith, Brick G. Billing, Yvonne Dionne and Kimberly J. McNeill. Review by Rob McLennan.

Volume one, issue four. Spring Equinox 1995. Editors: Kimberly McNeill, Victoria Martin. Managing Editor: Victoria Martin. Poems by Diana Brebner, Joanne Epp, Maggie Helwig, Michael Abraham, Linda Jeays, John Barton, Gregory McGillis, Wayne K. Spear, Warren Layberry, Catherine Jenkins and Rob McLennan. Reviews by Tamara Fairchild, Gregory McGillis and Colin Morton.

Volume two, issue one. Autumn Equinox 1995. Editor: Victoria Martin. Managing Editor: Victoria Martin. Poems by Linda Jeays, Andrew Milne, Wayne K. Spear, Diana Brebner, Ruth Latta, Andrew Steeves, Leo Brent Robillard, Kimberly J. McNeill, Paul Politis, Ross Taylor, Michael Abraham, Cyril Dabydeen, LeeAnn Heringer, Alan Corrigan, Julian Millar and E. Russell Smith. Reviews by Corey Coates, Tamara Fairchild, E. Russell Smith and Andrew Steeves.

Volume two, issue two. Summer Solstice 1996. Managing Editor: Victoria Martin. Poetry Editoris: G.T. Fougere, Stephen Martin, Victoria Martin. Book Reviews Editor: Victoria Martin. Visual Art Coordinator: Robin C. Fougere. Poems by Ken Norris, Allison O’Shaughnessy, Judith Anderson Stuart, Karen Hussey, Louise Bak, Noah Leznoff and rob mclennan. An interview with Ray Fraser by Andrew Steeves. Reviews by Andrew Milne, George Elliott Clarke, Juliana Starkman and Tamara Fairchild.

Volume two, issue three. Autumn Equinox 1996. Managing Editor: Victoria Martin. Poetry Editoris: G.T. Fougere, Stephen Martin, Victoria Martin. Book Reviews Editor: Victoria Martin. Visual Art Coordinator: Robin C. Fougere. Poems by Noah Leznoff, Jackie Moran, Marianne Bluger, Caitlin Hewitt-White, p.j. flaming, Tamara Fairchild, Jennifer Footman, Neil Hennessy, Mark Hamstra, LeeAnn Heringer, Ben Ohmart, Ruth Latta, Paul Politis, Janet Somerville, T. Anders Carson, Jay Ames, James Spyker, j.a. LoveGrove and Ray Heinrich. Interview with David Donnell by Neil Hennessy. Reviews by Corey Coates, Mark Hamstra and Andrew Steeves.

Volume two, issue four. Lughnasa (Summer) 1997. Managing Editor: Victoria Martin. Poetry Editoris: G.T. Fougere, Stephen Martin, Victoria Martin. Book Reviews Editor: Victoria Martin. Visual Art Coordinator: Robin C. Fougere. Poems by Susan McCaslin, Lorette C. Thiessen, Virginia K. Marshall, R M Vaughan, Allison Grayhurst, Linda Jeays, Kimberly Fahner, Mike Paterson, Christopher Finlay, David A. Groulx, R.D. Patrick, Rhonda Mack and Kirsten Aidan. Reviews by L. Brent Robillard, E. Russell Smith and G.T. Fougere.

Volume three, issue one. Winter (March) 1998. Editor / Poetry and Book Reviews: Victoria Martin. Poetry Editor: G.T. Fougere. Visual Art Coordinator: Robin C. Fougere. Poems by R.D. Patrick, Alex Boyd, Ernest Magi, Aidan Baker, Linda Frank, Giovanni Malito, Amy Eggleton, Kevin Sampsell, Rob Yedinak, Patrick Belmonte, Tricia Woods, Nicolas Mare Billon, Mark Howell, Debra Anderson, Brian Burke, Coral Hull, William Jacklin and p.j. flaming. Small Press Comix Feature by Leanne Franson. Reviews by Corey Coates and E. Russell Smith. Cover Art by Rev. Hipolito Tschimanga.

Published on December 04, 2015 05:31

December 3, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Joanne Epp

Joanne Epp [photo credit: Anthony Mark Schellenberg] has published poetry in literary journals, including The New Quarterly, The Antigonish Review, and CV2; her work appears in Lemon Hound's New Winnipeg Poets folio. Her chapbook,

Crossings

, was released in 2012.

Eigenheim

, her first full-length poetry collection, was published by Turnstone Press in 2015. Born and raised in Saskatchewan, she spent several years in Ontario and now makes her home in Winnipeg.

Joanne Epp [photo credit: Anthony Mark Schellenberg] has published poetry in literary journals, including The New Quarterly, The Antigonish Review, and CV2; her work appears in Lemon Hound's New Winnipeg Poets folio. Her chapbook,

Crossings

, was released in 2012.

Eigenheim

, her first full-length poetry collection, was published by Turnstone Press in 2015. Born and raised in Saskatchewan, she spent several years in Ontario and now makes her home in Winnipeg.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Having my first book accepted by Turnstone Press felt like a really big validation of my writing. I’d been writing a long time, and had become quite involved in the local writing community, but even though I already knew I was a real writer, having the book published still changed things.

The publishing process confirmed what I’d experienced a few years earlier, when I self-published a chapbook: while writing itself is solitary, putting a book out is a collaborative process. I’ve been grateful that I’m able to work with people who are skilled in things like design and marketing, about which I know little.

My recent work continues along earlier themes, but takes them in different directions. I’m still exploring the idea of home, which forms a prominent thread in Eigenheim, but also taking home as a given, a place or state of mind from which to move outward, and focusing more generally on landscape and place. Time has become a more frequent motif—or maybe I am just more conscious of it now. And I recently got a taste of ekphrastic writing, and found it quite stimulating.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I think I’ve always been attracted to the compactness of poetry, compared to prose. Years ago I made a couple of half-baked attempts at fiction, but ran into dead ends very quickly. Fiction seemed to require so very many words just to get from one thing to the next, and I became overwhelmed and impatient at the prospect.

Poetry was always a familiar thing. We had books of children’s poetry at home, and memorized poems at school. And I still have a book my aunt gave me for my ninth birthday called The Enchanted Land: Canadian Poetry for Young Readers . It contains both formal and free verse, and was probably where I first saw unrhymed poetry. I must have read it thoroughly; so many of its poems feel like I’ve always known them.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

A poem tends to go through several versions before it feels settled, although the general shape of the finished piece may be discernible in the first draft. I usually set a poem aside between revisions and let it sit for several months while I work on other things. The result is that a series of poems can take years to develop. I have several in progress at the moment, most of which started out as single poems and expanded as I kept discovering more angles on the subject.

There are a few poems in Eigenheim that I had to take apart and rebuild a few times before they really worked. Then there are the rare ones that emerged fully formed and required very little revision. But there’s only been two or three of those, ever.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Besides working on series, I also write individual pieces that aren’t deliberately connected to anything else. In any case, a poem begins with something concrete, with an image or incident or sound. I generally can’t start with an idea, unless I’ve got something concrete and particular to anchor it.

Eigenheim wasn’t conceived as a book from the beginning; when I started putting it together it was a collection of most of what I’d written up to that point. Then I had to find where the connecting threads were and determine what did and didn’t fit. The manuscript I’m working on now has a more deliberate structure—although there, too, it began as a discovery that the various series I was working on had some things in common.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I like doing readings. They can be part of my creative process, if I’m reading something fairly new and want to test it, but on the whole I see readings more as communication than as part of the creative process.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Recently I’ve heard a number of poets talk about how they push the boundaries of poetry in different ways. And I realized what I’d probably known for a long time, that while I find what these poets do very interesting, my approach to writing poetry is not like theirs. If I have a theoretical concern it’s probably this: does lyric poetry that is, by some measures, fairly conventional, still have interesting things to say? I’m working on the assumption that the answer is yes. But at the same time I find it helpful to listen to poets who stretch my ideas of how language and poetry work.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think attentiveness is a large part, if not the main part, of a writer’s task. A writer can reflect what’s around her, reflect on what’s around her, entice readers into the unknown, make them believe in fairies—but you don’t accomplish that by thinking about your role in the larger culture; you accomplish it by doing the best writing you can.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Working with an editor is difficult in that it makes me think harder about what I’m doing, but that’s a useful kind of difficulty and one that I might avoid otherwise avoid. I have become better at editing my own work, but there comes a point when I need someone else’s eyes. Eigenheim in particular is more tightly organized and more thematically interesting thanks to my editor.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

When I was in my teens my mother once told me that I should find something I loved and stick to it. (She rarely gives advice, which is probably why I still remember this.) She was thinking, I’m sure, of occupations that would earn me a living, and in that sense I have not followed her advice. But I have stuck with poetry, whatever else I was doing.

Then there’s something my organ teacher occasionally says when I ask about some detail of musical interpretation. Sometimes there are rules or conventions that apply, but at other times she simply says: “Use your ears.” This seems to me like a generally useful principle.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

Writing non-fiction ends up being a form of study for me; it’s for argument, discussion, for working out ideas. I find it harder to write than poetry, where you have to be convincing but not necessarily logical, and where you can make things up if you want.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I work in fits and starts, and am not nearly as disciplined as I’d like to be. Fortunately, I have a writing partner whom I meet with once a month (at times it’s been a group, but for now it’s just the two of us) to share new or recently-revised work. Those regular deadlines are a lifesaver.

One thing that’s remained consistent about the way I work is that I always write first drafts in longhand, and do a fair bit of editing with different coloured pens before entering anything on the computer. I think better with a pen in my hand.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Going for a walk is good. Sometimes it just clears my head; sometimes being physically in motion gets the words moving, too. At home, my favorite route goes down toward the river. When I go on a retreat (which I haven’t done in a while) I get into an alternating rhythm of writing and walking, which I find very satisfying.

I also read when I don’t know what to write. And sometimes I just keep writing: if I’m stuck for a word or phrase I write out as many possibilities as I can think of, until something works.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Poplar trees—I think it must be balsam poplars—have a scent I associate with the small towns in Saskatchewan where I grew up. You rarely see poplars in the city.

When I think of smells associated with the home where I am now, they’re all food smells. Toast, granola fresh from the oven, or the onion-and-herb aroma of soup.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Nature has become an important one, I think partly because of the way I find it rewards attentiveness. The places I visit over and over become ever more familiar, and yet they keep showing me new things. Music and visual art, too, influence my work. With music it happens organically, it more or less soaks in, while with visual art it’s been more deliberate. I’ve done a little ekphrastic writing recently, mostly through workshops, and have enjoyed the way it brings forth poems I would not have expected to write.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Dorothy Sayers: her novels, for pleasure, and her plays and essays for their solid arguments and their “aha” moments. G.K. Chesterton, for the same reasons. The best of Robertson Davies’ novels, for his incisive observations of character. Louisa May Alcott and L.M. Montgomery, again for their vivid characters, and also for their close attention to the details of women’s lives and work. The sermons I hear every Sunday, which are both passionate and unfailingly literate. I keep coming back to The Enchanted Land, the anthology I mentioned earlier, as well as 20th-Century Poetry and Poetics (ed. Gary Geddes) and the anthology we used in high school, Poetry Of Our Time, in which the work of several Quebec poets stands out for me.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d like to learn to write formal poetry. I’d probably have to take a class or workshop, because I wouldn’t have the discipline to do that on my own.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I once had notions of studying library science, and might still like that, as long as I got to work with actual books. I’ve been involved in music to a greater or lesser degree since I was a child, and in an alternate timeline I might have made it a bigger part of my working life.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I can’t imagine not writing. The amount of time I’ve been able to devote to it has varied quite a bit over the years, but it’s always been there, along with whatever else I was doing, whether studies or paid work or raising children.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South, a novel of social class that seemed like it was going to be firmly anti-industrialist but ended up being much more nuanced. As for films—my family and I watched several by

20 - What are you currently working on?

I have a manuscript in progress—it’s been in progress for several years and I really mean to get back to it soon, but there’s also a series of poems that I want to turn into a chapbook, and I’m preoccupied with that at the moment. I also just took a class in letterpress printing and want to keep doing that.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on December 03, 2015 05:31

December 2, 2015

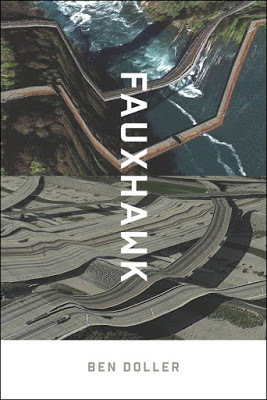

Ben Doller, FAUXHAWK

The word is a verbbut the wordis a noun

I noun youI noun pronounce younow pronoun you I do—

I am my wife’s wife.I wive. I wave the news at a beetlewho must die.

It runs into and out ofthis houseof mine. (“RUN”)

San Diego poet Ben Doller’s latest poetry title is

FAUXHAWK

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2015). The author of the poetry collections Dead Ahead (Louisiana State University Press, 2001), FAQ (Boise ID: Ahsahta Press, 2009) and

Radio, Radio

(Albany NY: Fence Books, 2010), as well as two collaborations, the poems in FAUXHAWK utilize an energized, and nearly manic, sense of play through erasure, repetition, exaltation, the footnote, lyric fragment and collage, as well as some of the most lively and gymnastic turns I’ve seen in a very long time. The collection is constructed with an opening, seemingly self-titled section of shorter poems before moving into shorter poem-sections: “Earing,” “Hello,” “Pain” and “Google Drive.” Part of what appeals about this collection is seeing the ways in which Doller is, with such a lively glee and a fierce intelligence, stretching out the boundaries of his own poetic, from the staccato-accumulations of a poem such as “[BEE]” (“I background my ground. / I backlist my list. // I backtalk my talk. / I backwash my wash.”), the erasure/excisions of the poem-section “PAIN”(“Consider thee carefully / what thou taketh for pain”), to underscoring the overwhelming footnotes of the poem “HELLO,” a short lyric poem awash with forty-six different footnotes, the first of which reads:

San Diego poet Ben Doller’s latest poetry title is

FAUXHAWK

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2015). The author of the poetry collections Dead Ahead (Louisiana State University Press, 2001), FAQ (Boise ID: Ahsahta Press, 2009) and

Radio, Radio

(Albany NY: Fence Books, 2010), as well as two collaborations, the poems in FAUXHAWK utilize an energized, and nearly manic, sense of play through erasure, repetition, exaltation, the footnote, lyric fragment and collage, as well as some of the most lively and gymnastic turns I’ve seen in a very long time. The collection is constructed with an opening, seemingly self-titled section of shorter poems before moving into shorter poem-sections: “Earing,” “Hello,” “Pain” and “Google Drive.” Part of what appeals about this collection is seeing the ways in which Doller is, with such a lively glee and a fierce intelligence, stretching out the boundaries of his own poetic, from the staccato-accumulations of a poem such as “[BEE]” (“I background my ground. / I backlist my list. // I backtalk my talk. / I backwash my wash.”), the erasure/excisions of the poem-section “PAIN”(“Consider thee carefully / what thou taketh for pain”), to underscoring the overwhelming footnotes of the poem “HELLO,” a short lyric poem awash with forty-six different footnotes, the first of which reads: Hello: The poem functions in the book as a phatic and in media res greeting as well as a belated introduction to certain poetic effects and themesthat are mobilized throughout the material. “Hello” is an Americanized compromise selected over the course of millennia from a multiplicity of alternatives: “holla” (stop, cease), “halon,” “holon” (to fetch), andmany more, hunting hollers (“halloo!”) and hailings. Each term conveys more a sense of pulling another into one’s sphere than an act of politesse or acknowledgement, an interruption or imperative as opposed to an introduction. Hail Caesar. Sieg Heil. Hey Girl. Halt your motion and attend to your addresser. Not until Edison successfully lobbied that the word be used as a greeting for telephone calls, a way to acknowledge the scratchy silence about to be breached, ws the term standardized. The telephone was originally envisioned as an open line between two offices, and a bell was originally proposed as a way to initiate a conversation until Edison’s suggestion (“I don’t think we shall need a call bell as Hello! can be heard 10 to 20 feet away. What do you think?). Another Bell, Alexander Graham, who is credited with the invention of the telephone, but who appropriated much of the vital technology (including a liquid transmitter) from one Elisha Gray, argued for “Ahoy!”The poem, “[BEE],” also, becomes a poem that, rhythmically, would be quite wonderful to hear aloud, and the sounds and rhythms that run through the breaks and collisions of Doller’s poems are quite striking. In FAUXHAWK, Doller articulates and explores the difficulties with language, and how language is so often misued and misappropriated, in an exacting and glorious music, and creating a fine and precise tension between drudgery and song. As he writes to open the poem “DUMMY”:

Isn’t it dumbto write a

letterat a time.

“On Google Drive,” he writes, in the sequence/section “Google Drive,” “the eucalyptus trees / sing Philip Levine // behind the Korean / bakesales.” The sequence/section plays off of a form of poetic translation, opening with a quote by American poet Fanny Howe, who is referenced throughout the sequence: “I’m rewriting Fanny’s book probably a gift for a friend / Or from her file I stole it from the faculty lounge.” The sequence reads as a curious blend of possible translation and poetic response to Howe’s poetry, from the cadence to the ghazal-like fragments and connections between them, and his coy references to the strong undercurrent of Catholic faith that runs throughout her poetry. “Unlike myself,” he writes, “you are immune to cliché. / Yours is faith to write what you say // myself, I can’t always tell when I’m joking / and I pop out of bed plotting paths to get loaded.”

In the notes at the end of the collection, Doller informs that “‘Google Drive’ is a word-by-word writing-through of Fanny Howe’s ‘Robeson Street,’ from the book of the same title, published in 1985 by Alice James Books. The line ‘Schizophrenia is hearing voices, not doing them’ belongs to the comedian Maria Bamford.” Still, each referenced link to Howe’s writing throughout the sequence reads as both link and deflection, which could easily be a matter of Dollar utilizing Howe’s language, but not necessarily similar intentions, somehow allowing him opportunities to slip his own poem underneath the structure of what is a variation upon hers:

Blackbird stealth fighters sure make noiseMach 12 over beachvolleyball totally Top GunOfficehours are over, but there’s a Spanish MiltonistInterviewing for an empty chair, holy smokes

The weather so soft I go vegan for the challengeHunger as an element, not hunger,inconvenience as continuous present

You just know the daughtersSkyjacked the text

Paradise Lost, if these wars are my VietnamOh Fanny I’ve barely watchedSo no thanksHold the onions, shouldn’t you be on strikeYou’ve been working since you made me my grassjuice

Three hundred and twenty seven more daysAre due this year and even with that many lives

I’d still be this lazy (“Google Drive”)

Published on December 02, 2015 05:31

December 1, 2015

Judith Fitzgerald (November 11, 1952 - November 25, 2015)

Canadian poet and critic Judith Fitzgerald has died. An obit here reads:

Ms. Fitzgerald died suddenly, but peacefully, at her Northern Ontario home on Wednesday, November 25, 2015 in her 64th year. Cremation has taken place. A Celebration of her Life will be announced at a later date. Judith Fitzgerald was the author of twenty-plus collections of poetry and three best-selling volumes of creative non-fiction. Her work was nominated and short-listed for the Governor General's Award, the Pat Lowther Award, a Writers' Choice Award, and the Trillium Award. Impeccable Regret was launched this year at BookFest Windsor to critical acclaim. Judith also wrote columns for the Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star, among others. "Her work is incredible...entirely inventive, deeply moving, and universally attractive." – Leonard Cohen. For further information, to make a donation, order flowers or leave a message of condolence or tribute please go to www.paulfuneralhome.ca or call Paul Funeral Home, Powassan, ON (705) 724-2024.

As I wrote in my recent review of her Impeccable Regret (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2015): “The author of some two dozen poetry titles going back more than forty years, from Octave (1970) to the most recent “Adagios Quartet” – published through Oberon Press as Iphigenia’s Song, vol. 1 (2003), Orestes’ Lament, vol. 2 (2004), Electra’s Benison, vol. 3 (2006) and O, Clytaemnestra!, vol. 4 (2007) – Fitzgerald, through multiple award nominations and her ongoing critical work, has been a consistent force in Canadian writing for decades. She has also produced some of my favourite poetry overall; her Lacerating Heartwood (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 1977) remains one of my most reread poetry collections.”

As I wrote in my recent review of her Impeccable Regret (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2015): “The author of some two dozen poetry titles going back more than forty years, from Octave (1970) to the most recent “Adagios Quartet” – published through Oberon Press as Iphigenia’s Song, vol. 1 (2003), Orestes’ Lament, vol. 2 (2004), Electra’s Benison, vol. 3 (2006) and O, Clytaemnestra!, vol. 4 (2007) – Fitzgerald, through multiple award nominations and her ongoing critical work, has been a consistent force in Canadian writing for decades. She has also produced some of my favourite poetry overall; her Lacerating Heartwood (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 1977) remains one of my most reread poetry collections.”Judith Fitzgerald was one of my favourite Canadian poets, as well as being one of my earliest and most passionate supporters, and both she and her work were very important to me in my twenties [see the piece I wrote here about a decade ago on one of her poems from Lacerating Heartwood]. We even brought her to town to read at TREE (as she claimed, her “second last public reading”) on April 9, 1996, and produced, through above/ground press, her chapbook 26 WAYS OF THIS WORLD: A Variation of Ghazals. Part of a longer work-in-progress, D’Arc and de Rais, about Joan of Arc and Gilles de Rais, I was always slightly disappointed she abandoned that title for the final publication, appearing as 26 Ways Of This World (Ottawa ON: Oberon Press, 1999). We kept an occasional correspondence that was furiously active between extended silences. She was good enough to even occasionally send poems for some of my schemes, including my Canadian issue of dusie. An email two weeks ago after my review of her Talonbooks was the first I’d heard from her in a few years.

As a poet, critic and person in the world, she was passionate, brilliant, forceful and sometimes difficult. I shall miss her.

Published on December 01, 2015 05:31

November 30, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Mary Hickman

Mary Hickman is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop where she received an Iowa Arts Fellowship. Her poems have been published in Boston Review, Colorado Review, jubilat, the

PEN American Poetry Series

, and elsewhere. She is the author of

This Is the Homeland

(Ahsahta Press, 2015) and teaches creative writing at Nebraska Wesleyan University in Lincoln, Nebraska.

Mary Hickman is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop where she received an Iowa Arts Fellowship. Her poems have been published in Boston Review, Colorado Review, jubilat, the

PEN American Poetry Series

, and elsewhere. She is the author of

This Is the Homeland

(Ahsahta Press, 2015) and teaches creative writing at Nebraska Wesleyan University in Lincoln, Nebraska.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

It has been really wonderful to be able to give the book to the poets I most admire and whose work directly inspired the poems. There is a poem in the book that I wrote in response to a poem by the German poet Anja Utler after I had come across her poem online and been floored by it. A few years later I got to meet Anja, to give a reading with her, and I even managed to convince her to blurb the book! She is also translating a section into German. I’ve been able to participate in these kinds of exchanges much more now that I have the physical object of the book to trade and give.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

My father is a poet. He doesn’t publish but he did once take a class with Bill Knott when he was still St. Jerome. When I was a child, maybe six or seven, he worked nights and I didn’t get to see him much. But he left little poems for me on post-it notes that I found when I woke. And I began to leave him poems in return. Poetry has always been an act of correspondence for me and comes out of a desire for connection.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

So far it seems that I’ll write a lot of material quickly in a burst and then revise it for a decade. It’s a slow process for sure.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I’m never working on a book from the beginning. I’m mostly just writing a lot of terrible stuff and cursing the muses for deserting me. Then something clicks—I’m there, it’s happening. I don’t know how I got there but I’m there, I’m on the vein. Which of course makes it feel like it will never happen again. The idea of having a larger project really appeals to me but it just isn’t how it has happened so far. Poetry continues to feel like magic. Maddening, maddening magic.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I like hearing poems out loud—mine and others—and being in a room of people with a shared investment in the revelatory work of poetry is usually pretty great. Most of the readings I’ve attended in the last decade have been at Prairie Lights Bookstore in Iowa City, Iowa. If you haven’t been, you’ve got to go! Even Obama has been to PL.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I continue to write about injury, loss, and recovery in terms of the relationship between time and material, the endless involutions of representation in art, and what might be said of possession or resurrection in our passing, material world. As the painter Jenny Saville says, “I paint flesh because I’m human.”

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I’ll defer here to a quote that sums up the ethos of the International Writing Program, a place where I have had the good fortune to meet fierce, brilliant writers from all over the world: “Only connect.”

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential! Homeland benefitted immensely from the keen editorial eye of Janet Holmes. And many of the very best edits and even the title came from the generous efforts of Eleni Sikelianos. The book would not be what it is without the work of many amazing “outside editors.”

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

When I was first entering my MFA program, a good friend advised me to try to hypnotize myself into not thinking about status, career, publishing, etc., and instead to hold onto the mysterious thing that makes me write—to pay attention to that. She said that if I did get freaked out and stop writing, not to worry, to just talk poetry and read read read and think and I’d write again. This advice has made a huge difference in my life.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

I’m in the middle of writing my dissertation right now and it is difficult! But there is also some comfort in having an outline and following it. And when I can synthesize a pool of ideas and nail an argument, it’s a little like getting a line just right.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Anyone who knows me knows I am always searching for the perfect routine. The only constant so far has been coffee.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Interviews. Pretty often I’m reading a book of artist’s interviews. David Sylvester’s book of interviews with Francis Bacon is very good. And I just started reading Talking in Tranquility: Interviews with Ted Berrigan (O Books, 1991).

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Pine trees.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Visual art and dance.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I’m very Spicer-focused right now as I’m writing about his fantastic first editions. He’s always a major influence and touchstone for me.

“Going into hell so many times tears it/ Which explains poetry.”

“Tell everyone to have guts/ Do it yourself / Have guts until the guts / Come through the margins / Clear and pure / Like love is.”

I’m also reading Cole Swensen’s beautiful new book Landscapes on a Train. Her ear is flawless!

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Finally become really fluent in Mandarin.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I am tempted to say surfer. But really I do think I would make a decent therapist.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

When I did try something else (medicine), it made me write even more!

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I mentioned her before but I’ll emphasize her amazingness here. engulf--enkindle by Anja Utler, trans. Kurt Beals (Burning Deck).

A sample (from “counter position: an interweavement in nine parts”)

– perceive: furrow –20 - What are you currently working on?

II

just at the opencuts: set free

to stand, sense, to drift now am: pitching to you through the: fissures hear – you speak of

waste heaps, of scree of: implanting, the

windrose, -wheel speak of: rotating, glistening

rotor blade you say – it: pitches, now, pitch, as a veined arm, a wing plows: its back, engraves furrows through earth-smoke through dead nettle fields

and at last: on the shoulder blade dulls down

I’ve been finishing up edits for my second book, which will be out in 2017, and have been working on some more landscape-driven poems. I spent last year driving back and forth between Iowa and Nebraska and all that road and space has begun to enter my work in a prominent way.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on November 30, 2015 05:31

November 29, 2015

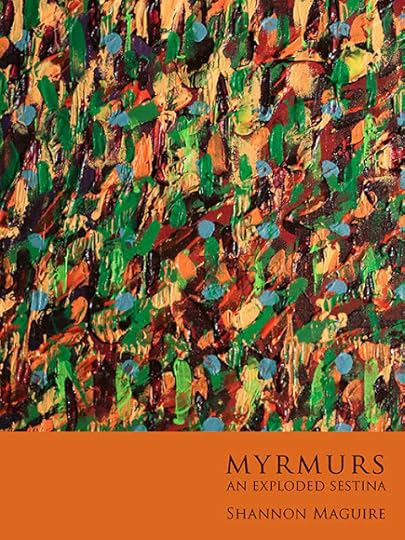

Shannon Maguire, Myrmurs: An Exploded Sestina

CROWD (THWARTED)

the process by which pedestrians on the ground surface enter the story is a measure of the rate at which the city is able to absorb in fall – the season hosts its fair shard of protests

the city itches per hour on the anterior or posterior aspect of the lower capacity of its nouns to decline root action in favour of spikes in vibrational output

omens are sometimes analyzed using runoff & channel flows to predict a downloadable field guide to how ocelli err on a moonless night

begin the discovery elks at any lost historic rail line in the cliffs of query, salmon, beltline & gardens, with leisure spaces in your shortage of drinking water & poker hand

point feet using odometer set two steps past Go Train of drought

enjoy nature through a series of mouth panels where sites of occupation or story happenstance

lift the Vale of Avoca bridge as a substitute for a test pattern or to straighten street; or leverage the bright water’s rust

The second volume in Shannon Maguire’s projected medievalist trilogy is Myrmurs: An Exploded Sestina (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2015), following on the heels of her debut collection, fur(l) parachute (BookThug, 2013) [see my review of such here]. As the press release informs, this new collection “is an innovative variant of the sestina form (a medieval mechanism of desire that spirals around six end words).” As part of an interview-in-progress forthcoming at Touch the Donkey , she opens a conversation on the trilogy as a whole:

I’ve been gradually working on the third book of my “medievalist trilogy”—right now I’m calling it Zip’s File. That’s where the poems that you’re reading here come from, and I’ll say more about them in a moment, but first I feel I should say something about the books that precede it because all three tease out one aspect of a larger question that I’ve been trying to work out, which is something like: How has Western culture influenced the literary, cultural, sexual, and political bodies that we’re living inside now and what role did/does the English language play in transmitting, producing, circulating, and maintaining gender, racial, and sexual difference? And how does change come about, linguistically, socially? Since (dammit Jim) I’m a poet and not a social linguist, my research has to be conducted and reported in poetic form... whatever that is! bpNichol’s statement (borrowed from Ludwig Wittgenstein and modified) “word order equals world order” is tremendous because it emphasizes the practice based/ processual effects of object-relations. So, modern English is a Subject-Verb-Object language, where the subject is grammatically assumed to have agency and the object is grammatically assumed to be passive. We make it “easy” to tell who is doing and who is being acted upon because it’s built into the spacial dimension of our sentences: they start with the actor and end with the...patient. But Anglo Saxon or Old English grammar was less obvious in terms of how it appeared on the page. Like Latin, the dominant Western language of commerce and authority at the time, Old English was a highly inflected language meaning that it had eight possible cases (or forms) that any noun could take, and a noun’s relation to other parts of speech depended on which form it took. This has several consequences, the most fun being that words had flexibility on the page and often the relations between words had to be thought out more carefully (as any student asked to parse a sentence in front of the group can attest). These are endlessly fun features for the contemporary poet!

It’s fascinating to see how Maguire’s particular research has spawned such an expansive poetic project, specifically one that explores how languages such as Latin and Medieval English have impacted the ways in which those living in contemporary Western culture exist, interact and interrelate. Much like poets Erín Moure, Lisa Robertson and Margaret Christakos (and numerous others), hers is a poetry constructed as a field of research, and one that could easily fit into far more than a trilogy of books.

Myrmurs: An Exploded Sestinais constructed in seven sections, the first six of which—“NOISE,” “LETTERS,” “PLEASURE,”CROWD,” “VOLUME” and “INCORRIGIBLE”—spool and spiral throughout the length and breadth of the book, akin to strands of DNA, leaving the final section, “TORNADA,” as a kind of coda. While the book might, at first, appear to be structured as a tapestry as opposed to any linear expression of narrative, each section opens, spreads apart and each progress toward an accumulation that leads to, if not a conclusion, but a logical place at which to close. There is something lovely about the way her poems is scattered with writing on ants that end up taking over her entire narrative. Is this, in the end, simply a poetry collection on ants? Hers is a machine in which every piece is concurrently moving, much like the ants, as, towards the end of the collection, she writes:

Myrmurs: An Exploded Sestinais constructed in seven sections, the first six of which—“NOISE,” “LETTERS,” “PLEASURE,”CROWD,” “VOLUME” and “INCORRIGIBLE”—spool and spiral throughout the length and breadth of the book, akin to strands of DNA, leaving the final section, “TORNADA,” as a kind of coda. While the book might, at first, appear to be structured as a tapestry as opposed to any linear expression of narrative, each section opens, spreads apart and each progress toward an accumulation that leads to, if not a conclusion, but a logical place at which to close. There is something lovely about the way her poems is scattered with writing on ants that end up taking over her entire narrative. Is this, in the end, simply a poetry collection on ants? Hers is a machine in which every piece is concurrently moving, much like the ants, as, towards the end of the collection, she writes:we need a better English word than “colony”to describe a measuring cup full of antsan ant brainis an elastic snap of lines’responsive bodies

It is also curious to note another title of language/form poetry writing around research on ants, from Maguire’s “exploded sestina” to the prose poems that make up American poet Sawako Nakayasu’s remarkable The Ants (Los Angeles CA: Les Figues Press, 2014) [see my review of such here]. Either way, I’m impressed at the ambition Maguire has for her writing so early, given that her first two trade poetry books are part of such an expansive project; even Robert Kroetschwas a few poetry books in before he understood “Field Notes” as a life-long poem, most of which (but for some earlier works, and a few produced at the end that hadn’t yet been included) were reprinted in his Completed Field Notes: The Long Poems of Robert Kroetsch (University of Alberta Press, 2000). What might this mean, as well, for what might follow, once her trilogy is finally complete? In Myrmurs, Maguire’s is a language poetry composed with a lyric lilt and tone, one constructed with precise measure and a musical ear.

Coarsely toothed meadowskerning silver-gray airs on inked high bed

Collation of sepals, obovate corsetsknuckle & lever rubbed with resin

Forms a stain in the woundgrasses swung back, attaching to covers

Excess twine to protect leavesglandular long-hairy perennial

Margins bristly, folded or unfoldedvolvere (“LETTERS”)

As well, Maguire isn’t the only contemporary poet utilizing medieval research for the sake of book-length poetry projects—Philadelphia poet Pattie McCarthy, for example, has long been working with and around medieval research—but Maguire’s research goes deeper than playing with historical information and the structures of medieval culture, pushing down into the bare bones of the language itself.

Epiphyte. Because she cannot, carry across

Shikimic & cinnamate. Hawk-moth unimpaired by warmer upperlayers is this red flapping of sound. Wetlands in first & thirdcourts of the moon

Krill & boundaries of mouths. Most dry ripple. More aridsentiments. She laid down by. Its own food this method producesTongue that exceeds. A word or certain land

Abiota, your new endearment. By which you are present in thisabsolute humidity. When they brutalized, they translated. Me intoher hands. I rainband there

Red snow. Calligraphy of algae. As once the red tide bloomedEskarne. Mouth muscles clam. Upwelling light. Tint in negotiatedwater. Neap

Narrow needle-shaped bodies are navigable words which trade ortravel along the spine

Eolian. Said of soils. Of fish flows. Syllables. Myrmecography ondesert varnish. Ghost myrmekite.

Published on November 29, 2015 05:31

November 28, 2015

Backwater Review (1997-1999): bibliography, and an interview

this interview was conducted over email in November 2015 as part of a project to document Ottawa literary publishing. see my bibliography-in-progress of Ottawa literary publications, past and present here

Leo Brent Robillard is an award-winning author and educator. His novels include Leaving Wyoming , which was listed in Bartley’s Top Five in the Globe and Mail for Best First Fiction; Houdini’s Shadow , which was translated into Spanish; and, Drift , which was long-listed for the Relit Award. The Road To Atlantis is his most recent novel – tracing a family’s dissolution and healing following a tragic accident. He lives in Eastern Ontario with his wife and two children.

Q: How did Backwater Review first start?

Q: How did Backwater Review first start? A: While attending Carleton University, I had the opportunity to edit the small literary journal Box 77. It was produced by the English Literature Society. I began there as a proofreader and member of the editorial board, then took over as editor of the magazine for three issues. I graduated from Carleton University in 1996, and this put an end to my involvement with that publication. But I guess you could say that I had been bitten by the bug.

I come from a small town in Eastern Ontario. Prior to my time at Carleton, and my move to Ottawa as a young man, I had no inclination about the existence of a Canadian literary scene. That there were other people like me – writers and poets – was a revelation. I couldn’t let it go.

I had made many friends who were involved in writing and publishing during my Ottawa years – people from the Ottawa scene, and others who had passed through the city’s various Reading Series like TREE, Sasquatch, or The Dusty Owl. I suppose my way of staying in touch was the creation of Backwater Review.

I’m sure that my initial vision was much grander. I was young and fired up about writing. I wrote in my first editorial: “Here you will discover the future conscience of a nation, of a time, of a place. This is a spawning ground for words.”

My goal was to have it distributed nationally. And it was. You could find it in magazine shops and bookstores from St. John’s to Victoria. We ran annual writing contests and gathered a few advertisers to help finance it.

And, you know, we did publish some very good writing. Especially poetry.

Q: I didn’t know you were part of Box 77! I remember Warren Layberry and Steve Zytveld, and even had work in there… Did you base Backwater Review on any journals in particular? What were your models? What other journals or presses existed around at the time?

A: I was reading stuff from all corners back then. I had a great deal of respect – and still do – for the long-running established journals like Grain , The Fiddlehead , Prairie Fire and The Malahat Review . If anything, I was modelling Backwateron their successful formats and appearances. I wouldn’t ever have called Backwater “edgy.” It was always about the writing. We weren’t trying to “be” anything. It was really more like, “If you build it, they will come.”

There were a number of journals cropping up all over the place back then. In Ottawa alone I remember your above/ground press offerings like Missing Jacket and Stanzas; there was Bywords and Hostbox and Hook & Ladder and Box 77. There was a funky little number called Graffitifish. The Carleton Arts Review was something back then, too. But one of my favourites was Richard Carter’s short-lived Yield. He really had a particular aesthetic in mind.

When you mention literary scenes, people default to Toronto or Vancouver. But there was a lot going on in Ottawa.

Q: I agree completely. During the mid-1990s (a couple of years before Backwateremerged) there were a dozen self-described literary journals in Ottawa, and yet, we keep being overlooked as a literary centre. Have you any thoughts on why that might be?

A: It certainly isn’t for a shortage of good writers – Andre Alexis, Elizabeth Hay, Alan Cumyn, Mark Frutkin, Charlotte Gray, Brian Doyle... All these people live or have lived in Ottawa. And they are only the ones who jump immediately to mind. But beyond established writers, what a healthy literary journal scene suggests is dynamism, vibrancy and promise for the future. This is where writers cut their teeth. The discussions that take place in these small literary collectives help shape and foment the country's eventual aesthetic.

It has been said that all great writers got their start in a small magazine. It is certainly true that Backwater published some eventual heavy hitters. For instance, Tim Bowling went on to win the CAA Award for Poetry and was several times short-listed for the Governor General’s Award, and even The Writer’s Trust for The Tinsmith . Stephanie Bolster won the Governor General’s Award for White Stone – which contained poems originally published in Backwater. Claire Mulligan’s The Reckoning of Boston Jim was short-listed for the Giller in 2007. And Russell Thornton is short-listed for this year’s Griffin Prize. This is but a partial list. You, yourself appeared in the magazine, and have gone on to win the CAA/Air Canada Award, as well as the John Newlove Award. Susan Elmslie won the A.M. Klein Prize. All of these writers graced the pages of Backwater in its brief three-year existence.

And many of them – if not actually from Ottawa – passed through one of its myriad Reading Series. That’s how they learned about Backwater. I remember personally soliciting Tim Bowling and Stephanie Bolster after sets they read in downtown Ottawa pubs.

So as for being over-looked, your guess is as good as mine. But it probably has something to do with book publishing and money. Chaudiere Books must find it pretty lonely, for instance, as a book publisher in Ottawa.

Q: What are you most proud of the journal accomplishing? What are your frustrations? What had you been hoping to achieve?

A: I am most proud that good writers considered submitting to it. I never felt that Backwaterhad to settle. George Murray, John B. Lee, D.C. Reid – we had an embarrassment of riches from which to choose.

In some respects, this ties in to what we hoped to achieve. We gave good writing another venue. There can never be enough opportunity to promote Canadian writers and writing.

And of course, this is also linked to the greatest frustration. At its height, Backwaterhad a little over 200 subscribers – but most of these people were writers themselves. I suspect even those who picked it up in a bookstore were writers, more often than not, looking for another potential market.

I see small press journals as literature’s best kept secret. I suppose that I had hoped without strategy or success to change that. But poetry, and good literature in general, are a hard sell. People like to digest their entertainment passively, and these things require engagement, reflection and time.

The same awards I’ve been mentioning here – while equally vital to writing and publishing – can sometimes be a limiting force as well. Readers, too often, use them as to do lists. If you aren’t on those lists, you don’t get “done.”

But I don’t want to sound bitter or melancholic. Because I’m not. Journals remain relevant for a different reason. I can see that now. They are valuable for their sense of peer review and writer development. They validate writers and their writing at an important stage in their growth. The beginning.

Q: Did your time producing Backwater Review have any effect on how you approached your own writing?

Q: Did your time producing Backwater Review have any effect on how you approached your own writing?A: When I completed my first novel in 2003, I knew exactly where I was going to submit it. I think I might even have known as I embarked upon writing it. Backwater didn’t just receive good manuscripts; as a review outlet, we received a lot of great books as well. I became very attuned to the market for fiction and poetry in the Canadian literary press. Much more than I am now. Turnstone published fantastic books, and I knew that my style of writing would appeal to them. I knew the moment that I finished reading Margaret Sweatman’s Sam & Angie, which I reviewed for Backwater, that Turnstone was the place for my work. By complete coincidence, Sharon Caseburg was their Acquisitions Editor at that time (and still is). We had published her poetry years earlier in Backwater. I don’t think that had any bearing on my eventual publication contract – and I certainly wasn’t aware of this particular connection when I sent my work off – but I’m sure that name recognition and familiarity may have gotten the manuscript out of the dreaded slush pile. A decade and four novels later, I am still publishing with them.

So I am not sure if editing made me approach writing differently in a stylistic sense. But I am sure that it made me take my work more seriously. More professionally. I began to understand that good writing took on many different forms, and that there were venues for each of those forms. In a way, my growing knowledge of the literary landscape legitimized what I was already doing. I knew I had a place and a potential audience.

Of course, it never hurts to read, and to read good writing in all of its forms, either. As an editor, I had no better opportunity to do just that. Did I learn anything from that apprenticeship – even at a subconscious level? Maybe. Probably.

Q: What was behind the decision to suspend the journal?

A: Time. And maybe money. But mostly time. My daughter was born in December of 1999. So I was a new father, a new teacher. I had moved away from Ottawa, and didn’t have the same network of writers and reviewers around me. Unless you’ve ever produced a small press journal with a skeletal workforce of volunteers, you can’t imagine the amount of work. Throw in diaper changing, sleepless nights, and 75 essays waiting to marked, and well…

We actually had a Volume IV planned. The submissions were in. We had the artwork. But we were just exhausted. My wife, a translator and teacher, was the assistant editor, so she was living everything that I was living. And basically, life just got in the way.

I resurrected Backwater briefly back in 2007, as an online review outlet for Canadian books. But was forced to take another hiatus. This past summer, I revamped the blog entirely ( backwaterreview.blogspot.ca ). I post to it at least once a week on Sundays. I still review Canadian literary press books. Sometimes I post essays, or travel pieces, or snippets of something else. But the focus is reviews. It’s work. But a lot less. And it’s fun. Always was. Always will be.

Backwater Review bibliography:

Volume I, Number 1. Spring/Summer 1997. Editor: L. Brent Robillard. Assistant Editor: Leslie G. Holt. Copy Editor: Caroline Bergeron. Poems by Stephanie Bolster, Ian Whistle, Lisl Swinehart, jason cobb, Behrouz Fallahi, rob mclennan, Richard Carter, Christl Verduyn and Caitlin Hewitt-White. Fiction by Dan Doyle, Matt Holland and Claire Mulligan. Interview with rob mclennan by L. Brent Robillard. Reviews by Naomi Watson-Laird, Donna Sorfleet, Richard Carter, Leslie G. Holt, rob mclennan and L. Brent Robillard.

Volume I, Number 2. Fall/Winter 1997. Editor: L. Brent Robillard. Assistant Editor: Caroline Bergeron. Copy Editor: Steve McKibbin. Poems by John B. Lee, Craig Carpenter, Brian Riggs, Susan Elmslie, Tim Bowling, Richard Carter, Stephanie Bolster, Jennifer Gavin. Fiction by Claudia Graf and Larry Rowdan. Interview with Susan Elmslie by L. Brent Robillard. Reviews by Paul Sorfleey, Carl Mills, rob mclennen, Richard Carter, Donna Sorfleet, and L. Brent Robillard.

Volume II, Number 1. Spring/Summer 1998. Editor: L. Brent Robillard. Assistant Editors: Caroline Bergeron and Richard Carter. Poetry by Alison Watt, Jason Rama, Paul Benza, Merilyn Lerch, Joe Blades, Claire Latremouille, Russell Thornton, Edith Van Berkley, and Errol Miller. Fiction by Tsigane Bristol, Rita Donovan, and Cliff Burns. Interview with Rita Donovan by L. Brent Robillard. Reviews by Carl Mills, Richard Carter, Nancy Leech, and L. Brent Robillard.

Volume II, Number 2. Fall/Winter 1998. Editor: L. Brent Robillard. Assistant Editor: Caroline Bergeron. Poems by George Murray, Susan McCaslin, Jason G. Santerre, Stephanie Bolster, Matt Santateresa and Russell Thornton. Fiction by Richard Scarsbrook, Stan Rogal and Marguerite Carrière. Interview with Stephanie Bolster by L. Brent Robillard. Reviews by Mausumi Banerjee, Nancy Keech and L. Brent Robillard.

Volume III, Number 1. Spring/Summer 1999. Editor: L. Brent Robillard. Assistant Editor: Caroline Bergeron. Poems by Keith Ebsary, Tony Cosier, rob mclennan, D.C. Reid, Antonia Banyard, Betsy Symons, Brian Burke, Jason Rama, Ronnie R. Brown and Margaret Malloch Zielinski. Fiction by Suki Lee and Michael Bryson. Interview with D.C. Reid by L. Brent Robillard. Reviews by Mausumi Banerjee, Nancy Keech and L. Brent Robillard.

Volume III, Number 2. Fall/Winter 1999. Editor: L. Brent Robillard. Assistant Editor: Caroline Bergeron. Poetry by Flanagan Wolff, Damien Potter, Astrid van der Pol, Michael Trussler, Sharon Caseburg, and Lyle Weiss. Fiction by Aliki Tryphonopoulos, Randy Schroeder, and Anne Burke. Interview with John Buschek by L. Brent Robillard. Reviews by Jesse Craig Bellringer, monna mcdiarmid, and L. Brent Robillard.

Published on November 28, 2015 05:31

November 27, 2015

Ongoing notes: Meet the Presses (part two,

[the room, preparing: including Karl Jirgens, Denis De Klerk and Noelle Allen] See the first part here.

[the room, preparing: including Karl Jirgens, Denis De Klerk and Noelle Allen] See the first part here.Toronto ON: If you aren’t already aware, Catriona Wright (poet and former Ottawa resident) has co-founded a new publishing venture, Desert Pets Press, with Emma Dolan, and some of their first publications include the anthology 300 Hours A Minute (2015) and E. Martin Nolan’s Poems From Still (2015). As their website informs: “Desert Pets Press was founded in 2015 by illustrator Emma Dolan and author Catriona Wright. Based out of Toronto, Ontario, the press publishes limited edition poetry and prose chapbooks and strives to combine exciting contemporary writing with innovative design.” Subtitled “Poems About YouTube Videos,” the chapbook anthology 300 Hours A Minute includes a series of playful poems (being exactly what the chapbook title suggests) composed by a variety of predominantly-emerging Toronto poets and fiction writers including Michelle Brown, Kathryn Mockler, Vincent Colistro (he has a first poetry collection due in spring with Signal Editions), Andy Verboom, Daniel Scott Tysdal [see my review of his most recent poetry collection here], Laura Clarke, Jess Taylor, Suzannah Showler [see my review of her first poetry collection here], Matthew R. Loney and Spencer Gordon.

Ted Talks

then TED foams at the mouthforgetting to stop. TED co-opts cud as a fertilizer

two point oh. Won’t hold a microphone so oneis fastened to TED’s head. TED says hands are keyboards,

keyboards are dead phonemes. TED walksatop a ramp atop the universities, whose popinjays cock

their heads up and balk. Cued to a power point,TED points to its hegemony, Gemini, Jesus, Fancy Pants,

the real regressives. TED shocks she who opensherself to touching it. Insteads are part of the prix fixe

of TED, such is its kindness, to offer hope. TED knockson my wall, in the voice of a friend, who shared this article,