Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 112

October 4, 2022

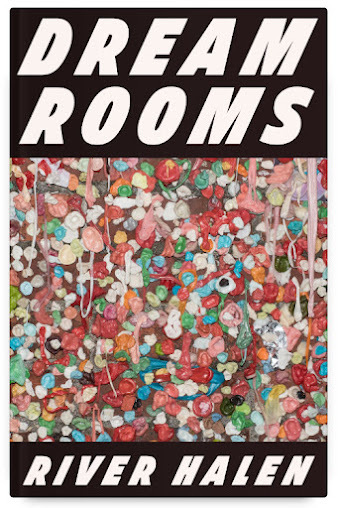

River Halen, Dream Rooms

Dec. 28

My ex had clinical anxiety. This fact does not explain everything. But some parts of our relationship were a tile to him.

Today I take the three towels that are in Soft’s closet and lay the down in the tiled hallway, which connects to the carpeted office and bedroom. The way dreams connect to new landscapes that are really just the same familiar landscapes. Frog begins to race along the towels and into each room and back again, into each room and back again, growing increasingly excited.

Eventually Frog gets to the bathroom. He pauses, craning his neck out over the cool, ocean-blue ceramic floor with my stray hairs scattered over it like drawn-on waves. He twitches there a moment. Then he jumps.

If a man is someone you do things for, then a panicked man is not less of a man but more than one.

Produced as the fifteenth in Book*hug’s “Essais Series” is Montreal poet and editor River Halen’s latest poetry title,

Dream Rooms

(Toronto ON: Book*hug Press, 2022). Dream Rooms is self-described as “part essay, part poem, part fever dream journal entry,” set as a book-length exploration “about personal revolution, about unraveling a worldview to make space for different selves and reality. Set in the years that led up to author River Halen coming out as trans, this collection concerns itself with what sits on the surface of daily life, hidden in plain view, hungry for address […].” The table of contents offer but eleven poems in the collection, although these exist in the larger structure of the collection almost as signposts, or even Greek Chorus, offering dated journal-esque entries in sequence as the tether that runs across and through between these pieces. “There were no women in my childhood,” they write, as part of the opening poem, “SELF LOVE,” “in books or real life / just men and cows— / the women I loved were all men / and the women I didn’t, cows. / No women in this exploration, either / just a man and a cow / and I was both—I did not know / how profoundly—this hurt [.]” Perhaps, at times, certain of these titles might be set as section-openers, simply highlighting where the next stretch of Halen’s explorations begin, grouping each short selection of prose poems underneath a kind of banner. “When I go to the bathroom / to cry about your failures,” Halen writes, to open the poem “REASON,” “I do it just like you / if you were me / watching the mirror / to see if sympathy is possible / then trying my best / to cry more beautifully.”

Produced as the fifteenth in Book*hug’s “Essais Series” is Montreal poet and editor River Halen’s latest poetry title,

Dream Rooms

(Toronto ON: Book*hug Press, 2022). Dream Rooms is self-described as “part essay, part poem, part fever dream journal entry,” set as a book-length exploration “about personal revolution, about unraveling a worldview to make space for different selves and reality. Set in the years that led up to author River Halen coming out as trans, this collection concerns itself with what sits on the surface of daily life, hidden in plain view, hungry for address […].” The table of contents offer but eleven poems in the collection, although these exist in the larger structure of the collection almost as signposts, or even Greek Chorus, offering dated journal-esque entries in sequence as the tether that runs across and through between these pieces. “There were no women in my childhood,” they write, as part of the opening poem, “SELF LOVE,” “in books or real life / just men and cows— / the women I loved were all men / and the women I didn’t, cows. / No women in this exploration, either / just a man and a cow / and I was both—I did not know / how profoundly—this hurt [.]” Perhaps, at times, certain of these titles might be set as section-openers, simply highlighting where the next stretch of Halen’s explorations begin, grouping each short selection of prose poems underneath a kind of banner. “When I go to the bathroom / to cry about your failures,” Halen writes, to open the poem “REASON,” “I do it just like you / if you were me / watching the mirror / to see if sympathy is possible / then trying my best / to cry more beautifully.” Curiously, I hear echoes of tone from Shannon Bramer’s scarf (Toronto ON: Exile Editions, 2001) in Halen’s journal-lyric; although that particular poetry collection was composed as a fiction, both collections are written through first-person journal-entry narration through the lyric around isolation, shifts and an attempt to work through the shifts to a place where the ground has begun to settle. It is interesting how the “essais” series-to-date, curated by Toronto poet Julie Joosten—including Erin Wunker’s articulate, irreverent and thoughtful Notes from a Feminist Killjoy: Essays on everyday life(BookThug, 2016) [see my review of such here], Margaret Christakos’ remarkable lyric essay/memoir Her Paraphernalia: On Motherlines, Sex/Blood/Loss & Selfies (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2016) [see my review of such here] and Chelene Knight’s Dear Current Occupant: A Memoir (Toronto ON: Book*hug, 2018) [see my review of such here]—each exist as book-length personal studies through varying forms of the lyric essay, blending non-fiction with the lyric form to examine, determine and situate, or even re-situate, the particular author’s thoughts on identity, living and thinking. Halen, the author of a handful of poetry collections, works in this collection to situate themselves through and including their coming out as transgender. “So there was never any pure time / if pure time exists for anyone,” they write, to open the extended poem “HONEYMOON,” “I do not know [.]” In Dream Rooms, Halen simultaneously reveals and creates a new kind of space for themselves in the space of their own body, and their own body in space, one occupied by family, friends and current and former partners. Halen’s sentences reveal and invoke, blending the best that their poetry and non-fiction through this multi-faceted examination of form, from gender identity and the prose essay through the poetry day book. This, one might say, is the story of the thinking around that particular experience, and that particular time.

The Spanish Civil War is called the Spanish Civil War because within one country two sides fought and eventually the fascists won and kept power for thirty-nine years. Whereas the Mexican Revolution is called a revolution because when two sides fought, the fascists lost. When Díaz was deposed, dictatorship ended. Frida Kahlo, who was three years old at the time, was born again, a revolutionary and a communist. She often lied about her age to convey this truth—she would say she was born in 1910, the year the revolution started, instead of 1907.

Once I wanted to explain my complicated terrain of stubble and thickets to a lover, and I overshared. I composed an email titled “My body hair: a summary,” which contained a list of numbered points. Writing this email was intoxicating, like suddenly unleashing the story of my life. I am still revising and adding to it, even though I sent it a long time ago and that lover has moved on.

Frida Kahlo depicted herself very often in her art. Many of the physical experiences of her life are represented there explicitly. (“THE FULL IMPULSE”)

October 3, 2022

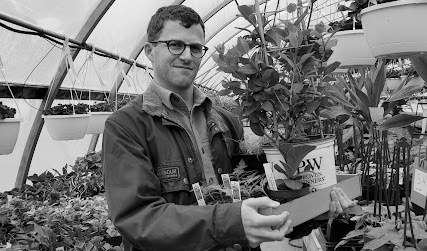

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Michael Goodfellow

Michael Goodfellow is the author of the poetry collection

Naturalism, An Annotated Bibliography

, just published by Gaspereau Press, spring 2022, and of a collection in draft titled Folklore of Lunenburg County, which is supported by a Research & Creation Grant from the Canada Council for the Arts. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in the Literary Review of Canada, The Dalhousie Review, CV2, Reliquiae and elsewhere. He lives in Lunenburg County, Nova Scotia, where he grew up.

Michael Goodfellow is the author of the poetry collection

Naturalism, An Annotated Bibliography

, just published by Gaspereau Press, spring 2022, and of a collection in draft titled Folklore of Lunenburg County, which is supported by a Research & Creation Grant from the Canada Council for the Arts. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in the Literary Review of Canada, The Dalhousie Review, CV2, Reliquiae and elsewhere. He lives in Lunenburg County, Nova Scotia, where he grew up.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book changed my life in that the publisher I most desired agreed to publish it, and my dream came true.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I saw poems doing things that no other form of writing or art could do. They were more eviscerating and life changing than any painting or song. I didn’t want to make anything else.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It’s a slow process with many drafts, revisions, edits and pencil marks.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A poem usually begins for me in the woods behind the house, in a field, along the shore or in the garden.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

They’re neither part of my creative process nor counter. I don’t absorb information well aurally, so I don’t listen to the radio or podcasts or attend poetry readings. I’ll sometimes do readings if asked because I understand other people enjoy them. In terms of promoting poetry collections, I think readings are one of the most inefficient ways of raising awareness about a book; they’re the literary equivalent of burning coal to produce electricity—dimly lit, energy intensive and unsustainable in the longterm of a writer’s daily life.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

My poems are generally situated in the place where I live and grew up—the south shore of Nova Scotia.

My first collection, Naturalism, An Annotated Bibliography (Gaspereau Press, 2022) explores the way humans’ relationship with nature is often mediated through text and guidebooks, engaging with things in the forest that show humans once lived there: wild apple, stone walls, clearing piles. Just as we can’t seem to understand nature without naming the things we see, we’re unable to move through it without leaving markers of the lives we’ve led. In this way, a rain-worn ironstone wall in a clearing of hemlock inadvertently becomes the name we tried to form for what we saw in nature, but failed: a mark or word that even the rain couldn’t wear away.

My second collection, currently in draft, is titled Folklore of Lunenburg County and uses Helen Creighton’s 1950 ethnographic collection of fragmented experiences of the supernatural in this part of Nova Scotia as a departure point on the way to something darker and more hidden, exploring the way that the supernatural has been an analog for loss, disappearance and violence, and the way that early experiences of the supernatural in this area were often mediated by love, community, and neighbours. The collection is supported by a Research & Creation Grant from the Canada Council for the Arts.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think that the role of a poet is to burn what can’t live and cauterize what mustn’t die.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I find that literary magazine editors in Canada rarely suggest or request edits, though magazine editors in the U.S. are more proactive in this regard; magazine edits, when offered, are valuable. In terms of book editors, working with Andrew at Gaspereau when editing the book was more than essential.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

It was what Alice Munro told The Paris Review in 1994 in relation to what place and landscape meant to her and all that she had written: “I’ll never leave.”

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I get up around 5:30 a.m. and sit on my kitchen floor for a while, writing in my notebook, before I make coffee. Just after waking up, my brain is still making analogies and strange connections between things before the rational part of the world has come into focus. I fit in writing and edits into various points throughout the day: parked in my ’98 Rav4, sitting on the porch, waiting for dinner to cook, waiting for appointments and in the bath.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Nature, and the places in nature that show humans were once there.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Garlic, just harvested.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

If that’s what David W. McFadden once said, I think he is dead wrong, and the idea that books come from books is monstrous, framing their growth as a kind of cancer. It’s truly levelling and devaluing of all that is rich in the world.

Your question also frames nature as a form, like music or visual art, which is an interesting concept. Nature is the most important influence on my work, but I don’t see it as a form. If we’re talking about human life, we’re the form of the work, and nature is the ending. In a while, when all of this is gone and there are no longer humans, nature will still be here—the blank page after the book ends, the cover that holds it together, the table on which the book is set, the bedrock under the table.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Alice Munro, Robyn Sarah, Carl Phillips, George Johnston, Jack Gilbert, Jenny George, Gabrielle Bates, Aria Aber, Patrick Modiano, Louise Glück, Mavis Gallant, Thomas Wyatt, Chaucer, W.S. Merwin, Linda Gregg, Richard Siken, Anne Sexton, Denise Jarrott, Jose Hernandez Diaz, Despy Boutris, Catherine Pond, Taneum Bambrick, Hailey Leithauser, A. E. Stallings, Alice Oswald, Kevin Young, George Oppen, Ashley Anna McHugh.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d like to buy a woodstove.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

If I couldn’t write, I’d rather be dead.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It was the smallest and most fatal knife in the drawer.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The Summer Book by Tove Jansson. Near Dark by Kathryn Bigelow.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on my next collection of poems, Folklore of Lunenburg County.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

October 2, 2022

Melissa Ginsburg, Doll Apollo

Craft Day

Scissors cut

through the snowflaked

morning. Dolly

sharpens her edges.

Trims herself, gives herself

fringe. Makes more like her.

Sisters, clones. She scissors

their slick

magazines, girlskins

sleek as blades.

She hones her scissors

On sandpaper. She will marry

that abrasion. Make it

scrape her. She’ll

feel it. She’ll unfold

garlands.

Mississippi writer and editor Melissa Ginsburg’s second full-length poetry title, following her debut,

Dear Weather Ghost

(Four Way Books, 2013), as well as the novels

Sunset City

(Ecco, 2016) and

The House Uptown

(Flatiron Books, 2021), is

Doll Apollo

(Baton Rouge LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2022), a collection described thusly on the publisher’s website: “With lush imagery and surprising syntactical turns, the poems in Doll Apollo merge mythology with close attention to the patterns, colors, and contours of the material world. Through the figure of the paper doll, the hoax conspiracy surrounding the Apollo moon landing, and lyrics embedded with violence and beauty, Melissa Ginsburg’s feminist ecopoetics weaves the domestic and celestial into considerations of female identity, desire, spiritual yearning, and doubt.” Ginsburg is a poet I first discovered through an issue of FENCE magazine back in 2015 [see my review of such here], and her Doll Apollo(which doesn’t include the work from that issue of FENCE) is a book-length lyric framed in a reference to the Ancient Greek myth of Daphne and Apollo; of the nymph pursued, and finally, transformed for the sake of protection. “halted mid stride / un-nymphed as mayflies,” the opening poem, “Daphne,” offers, “laureled & wreathed [.]”

Mississippi writer and editor Melissa Ginsburg’s second full-length poetry title, following her debut,

Dear Weather Ghost

(Four Way Books, 2013), as well as the novels

Sunset City

(Ecco, 2016) and

The House Uptown

(Flatiron Books, 2021), is

Doll Apollo

(Baton Rouge LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2022), a collection described thusly on the publisher’s website: “With lush imagery and surprising syntactical turns, the poems in Doll Apollo merge mythology with close attention to the patterns, colors, and contours of the material world. Through the figure of the paper doll, the hoax conspiracy surrounding the Apollo moon landing, and lyrics embedded with violence and beauty, Melissa Ginsburg’s feminist ecopoetics weaves the domestic and celestial into considerations of female identity, desire, spiritual yearning, and doubt.” Ginsburg is a poet I first discovered through an issue of FENCE magazine back in 2015 [see my review of such here], and her Doll Apollo(which doesn’t include the work from that issue of FENCE) is a book-length lyric framed in a reference to the Ancient Greek myth of Daphne and Apollo; of the nymph pursued, and finally, transformed for the sake of protection. “halted mid stride / un-nymphed as mayflies,” the opening poem, “Daphne,” offers, “laureled & wreathed [.]” While the examination of working and reworking updates of mythologies through the book-length lyric certainly isn’t something new—there is something here reminiscent of Gale Marie Thompson’s own second full-length poetry title, Helen Or My Hunger (Portland OR: YesYes Books, 2020) [see my review of such here], offering her own lyric study of language and beauty, but on the mythical and multiple retellings of Helen of Troy—Ginsberg, on her part, utilizes less a retelling or reworking than allowing that particular myth a kind of loose framing to the collection, able to open up poems riffing off further directions, whether of paper dolls or stories of how the moon landing, via Apollo 11 in 1969, was actually faked. “doubt has been married so long to the altar,” the poem “When Doubt Comes to Apollo” ends, “each star a tribute doubt hunted and placed // on a plate [.]” As the collection opens with the singular poem “Daphne” and into a triptych of lyric sections: “Doll,” “Apollo” and “Toile,” Ginsburg swirls her references and narratives around that central core of Greek myth, writing out beauty and female agency, the stories we tell (including those we tell ourselves) that get altered, shifted and even twisted, and of space travel. As much as anything, this is a lyric of perception and doubt, and how perception shifts, shimmys and twists, even to the point of disconnect. As the second half of the poem “The Bench” reads: “We were figures // in a sketch of a cold deer path. // I did not expect to survive // such flattening. Then you said look // for a perfectly straight horizontal line // and under a mound of blue snow // such a line appeared.”

I find it curious, also, how she utilizes poem-titles in her work, as Ginsberg’s lyric distillations each unfurl from each singular point, utilizing titles almost as subject headers before launching into her examinations, often offering a closing line or two to satisfy a particular kind of closure to that singular moment. “I waited,” as she writes, to close the poem “One Cannot Read Oneself without Great Difficulty,” “quaking under ink // wanting the fingers and the eraser the eyes / of the circulars variously glossed [.]”

October 1, 2022

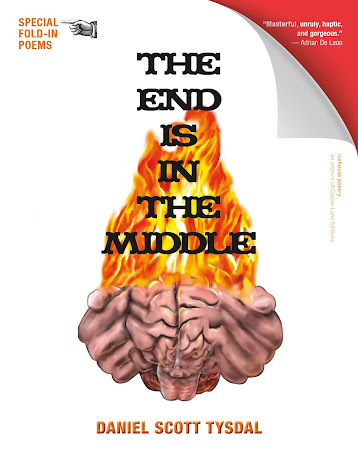

Daniel Scott Tysdal, The End Is in the Middle

Ballad of the Mad Bomber

A bomb is not a story, though

Metesky claims to soothe

with rumour-spurring, blast-fed tales,

throning the search for truth.

Through telephone and movie seat

and subway coined with bombs,

George liens the wrongs and dastard debit

yet owes each flame-scorched palm.

Sedate a dream with waking then

rebrand each corpse a calf.

Explore “Mad Bomber”-planted visions,

just slice your eyes in half.

Though George elates he never killed,

designed his bombs to goad,

if terror’s free of fuse and charge

Toronto poet Daniel Scott Tysdal’s work has long been engaged with an irreverent and conceptual structural inventiveness and play on and through poetic form, offering a particular flavour unique in writing and publishing generally, but very much unique through Canadian writing. Anytime I’m moving through a new collection of his, I wonder: exactly where did this guy come from? The author of the poetry titles

Predicting the Next Big Advertising Breakthrough Using a Potentially Dangerous Method

(Regina SK: Coteau Books, 2006),

The Mourner’s Book of Albums

(Toronto ON: Tightrope Books, 2010) [see my review of such here] and

Fauxccasional Poems

(Fredericton NB: Goose Lane Editions/icehouse poetry, 2015) [see my review of such here], as well as the short story collection

Wave Forms and Doom Scrolls

(Hamilton ON: Wolsak & Wynn, 2021) and the poetry textbook

The Writing Moment: A Practical Guide to Creating Poems

(Oxford University Press, 2013), his latest title is the poetry volume

The End Is in the Middle

(Goose Lane Editions/icehouse poetry, 2022). His work exists as a curious outlier, coming at form and pop culture from the seemingly-oddest angle, and his outlier status seems moreso through his publishing books with presses not known for producing experimental work (it isn’t lost on me that one of the blurbs on the back cover is by Saskatchewan poet Sylvia Legris [see my review of her latest here], arguably another Canadian poet outlier). Tysdal’s latest,

The End Is in the Middle

, works through the structure of the infamous Mad Magazine fold-in, something just about everyone of at least two or three generations would be entirely familiar with, as he writes to introduce the collection:

Toronto poet Daniel Scott Tysdal’s work has long been engaged with an irreverent and conceptual structural inventiveness and play on and through poetic form, offering a particular flavour unique in writing and publishing generally, but very much unique through Canadian writing. Anytime I’m moving through a new collection of his, I wonder: exactly where did this guy come from? The author of the poetry titles

Predicting the Next Big Advertising Breakthrough Using a Potentially Dangerous Method

(Regina SK: Coteau Books, 2006),

The Mourner’s Book of Albums

(Toronto ON: Tightrope Books, 2010) [see my review of such here] and

Fauxccasional Poems

(Fredericton NB: Goose Lane Editions/icehouse poetry, 2015) [see my review of such here], as well as the short story collection

Wave Forms and Doom Scrolls

(Hamilton ON: Wolsak & Wynn, 2021) and the poetry textbook

The Writing Moment: A Practical Guide to Creating Poems

(Oxford University Press, 2013), his latest title is the poetry volume

The End Is in the Middle

(Goose Lane Editions/icehouse poetry, 2022). His work exists as a curious outlier, coming at form and pop culture from the seemingly-oddest angle, and his outlier status seems moreso through his publishing books with presses not known for producing experimental work (it isn’t lost on me that one of the blurbs on the back cover is by Saskatchewan poet Sylvia Legris [see my review of her latest here], arguably another Canadian poet outlier). Tysdal’s latest,

The End Is in the Middle

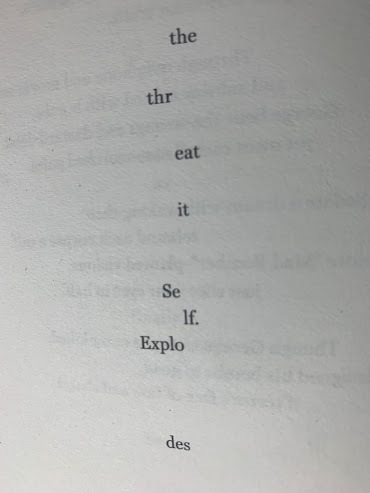

, works through the structure of the infamous Mad Magazine fold-in, something just about everyone of at least two or three generations would be entirely familiar with, as he writes to introduce the collection: The fold-in poetry form was inspired by one of my childhood heroes: Al Jaffee. For fifty-six years, his illustrated fold-ins comprised the back inside cover of every issue of MAD magazine (Jaffee retired in 2020, when he turned 100). A page-filling image, with a brief caption at the bottom, would be transformed by folding the page to reveal a visual and textual punchline. Borrowing Jaffee’s fold-in technique, the fold-in poem is characterized by three features: 1) the poem does not end at the bottom of the page, 2) the reader completes the poem by folding the page in so that the A guide meets the B guide, and 3) these folds reveal the final line of the poem nested within the original lines. For accessibility reasons, the final, post-fold line also appears after each poem.

the final line of "Ballad of the Mad Bomber"

the final line of "Ballad of the Mad Bomber"

Arguably, most if not all poetry exists with a requirement for the reader to make connections not overtly in the body of the poem, however directed their reading might be by the author, rarely is the requirement of the reader so physical. I’m reminded of bpNichol’s unreleased and burnable mimeo poem Cold Mountain(no date, but circa 1960s), a visual poem built to be curled, stood up and set with a match; although, in comparison to Tysdal’s folding structure, nothing new is specifically revealed in or through Nichol’s text by the reader doing such a thing. For Tysdal, the requirements for such a piece are immense, offering a narrative echo of the Jaffee’s jumbling visual collage that offered a final reveal that provided a gag as well as new insight into that original, sprawling page. That original A to B is hardly as uncomplicated as it sounds, and to even be a single line, a single letter, off would mean the entire piece might fall apart. And for the benefit of those who don’t wish to mangle their copies, as well as for accessible reasons, the final revealed text is also offered on each following page. It would be curious to know, down the road, how many readers actually did attempt to fold the pages together to reveal the final, hidden line of each poem as it is meant to be experienced. Even jwcurry, bpNichol bibliographer, has said that Cold Mountain was best experienced as a pair: one copy to burn, and one copy to keep pristine.

There’s almost something of the rhyme and joyful metre in certain of these pieces that echo Toronto poet Dennis Lee’s classic poetry titles for children, whether Alligator Pie (1974) or Jelly Belly (1983), as Tysdal bounces and riffs in rhythm in a poem such as “Ballad of the Mad Bomber,” although most pieces exist as extended, singular, stretches. “Why bother writing a poem?” he begins, in the poem “Make,” “The future, / breaking away, doesn’t want it. Even if / your lines are a monument to their moment, / tomorrow’s fools will legislate new rules and / blast your statue, or extinct themselves into / stillness, the levelling left to sand and time.” Set in five sections of poems, each with single-page poems, including the occasional visual poem, and verso final line reveal—“MAD ME,” “MAD MEN,” “MAD MAKING,” “MAD COMPANIONS” and “MORE MAD ME”—the poems are composed with wit and vigor, attention to small moments and grand gestures alike. They are expressive, hopeful and compassionate, even in poems such as “Suicide,” suggesting “A pact signed with such force / it breaks.” Or, as the poem “Snowflake” offers: “it’s because we will melt / that we don’t fear the light.”

September 30, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Thomas Kendall

Thomas Kendall

is the author of The Autodidacts released May 2022. Dennis Cooper called The Autodidacts ‘a brilliant novel — inviting like a secret passage, infallible in its somehow orderly but whirligig construction, spine-tingling to unpack, and as haunted as any fiction in recent memory.’ His work has appeared in the anthologies

Abyss

(Orchards Lantern) and

Userlands

(Akashic Books) and online at Entropy.

Thomas Kendall

is the author of The Autodidacts released May 2022. Dennis Cooper called The Autodidacts ‘a brilliant novel — inviting like a secret passage, infallible in its somehow orderly but whirligig construction, spine-tingling to unpack, and as haunted as any fiction in recent memory.’ His work has appeared in the anthologies

Abyss

(Orchards Lantern) and

Userlands

(Akashic Books) and online at Entropy. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first novel has only just come out. I don’t know how people are going to feel about it and I don’t know how their reactions to it (presuming there are any reactions at all, that anyone reads it) will make me feel. Positive or negative. Either way I don’t imagine it’ll do me any favours but it would be nice to know if it succeeded in being, for anyone, something interesting and possibly beautiful. What I can say is that I had to learn how to write the novel and I think that the act of producing something, developing an intuition towards its conclusion, could qualify as transformative.

The novel I’m finishing now is in many ways a reaction to The Autodidacts. It’s very singularly focused and the structure of it isn’t part of the narrative. I wanted to see if I could work with plot in an interesting way and I thought the only plot driven style of work that I’ve ever really enjoyed is noir. But it’s not really noir. It is also about biological machines and posthumanism etc. Anyway, I’m terrible at describing my work and I want to pretend that’s a virtue?

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I can’t write non-fiction because I don’t want to be near anything interesting when I write. I want to disappear when I write.

I’m not very good at poetry. I can only do it sincerely. That sounds bad but I hope you understand what I mean.

A novel gives you a lot of space to cut away at.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I have a quite infuriating process. I usually have an image or an idea of the affect I’m interested in and then I write to think about what it is composed of and then I continue to write outwards from that. I usually know how I want it to end. I think about structure a lot but the events tied to that structure have to be intuitive so it’s often a complete car crash. I rewrite continually but the rhythms of the work seem to be there at the beginning. I’ve written complete, or almost complete versions, of both novels and then had to completely trash them several times over. Like trash them. The kind of complete toilet flushing waste that makes you question if you can actually do anything interesting or understandable. And I write S-L-O-W. Writer’s have an insane capacity for belief, that sense of faith is the main virtue of the practice. Self belief through excoriation. I don’t know how long I’ve spent trying to get something right in a sentence. It doesn’t help that my grammar is appalling. Still, I want my sentences to be under an amount of pressure that borders upon the unbearable.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Always a book. The rest as above.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I’ve never really been part of any community or published enough to be invited to do many readings. I think I quite like them but at the same time it seems like it should be a special occasion. I can’t be giving readings on the regular. Too social.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I think every writer I like has their themes. I think I know what mine are. What links my work is a kind of obsession with trying to detail the experience of thought or the relation between language and what it restrains.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I don’t know that any position I take on this is satisfactory enough to express because I think it's impossible to think about this in the singular. That the impulse to individualise is so prominent in our language is something that I’ve been thinking about a lot at the moment. How do we define a multiple? And of course the answer is you don’t have to, you only have to open yourself up to connection to it.

This isn’t a cop out, I think all creative acts have a duty. The role of the writer, as I see it, is to show a fidelity to whatever is driving creation.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I think you have to get your writing up to scratch. Take it as far as you can go and then submit it. But having someone question what you’ve done and spot your errors and tells is important.

(BTW It took me a long time to learn how to redraft. You have to redraft.)

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I remember on Dennis Cooper’s blog there was a day on writing tips and the one that stood out to me was to consider writing as a drug. What kind of experience, and what variable for experience, is your work creating is how I interpreted it. It helped me with being able to think of a reader, because I sincerely struggle/d with that.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I wake up at 6. If our toddler wakes up before 7 I make him breakfast as I drink coffee. At 7 I walk forty five minutes to the school I work in. It’s a good walk. I usually have work until 4 and then I walk home again. I feed our toddler and, depending on what day of the week it is, I wash him and put him to bed. Then we eat and have a chance to catch up. On Tuesdays my wife usually visits a friend and I write. Then I usually have one other two-three hour session somewhere in the week.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I just stare at the computer and rewrite sentences until something or nothing happens. Then I tell myself it’s a case of creating the opportunity, just being there, that will lend itself to an answer.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I have a very poor sense of smell.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Film evokes the inexplicable and is able to situate the reader in an ambiguous state much more effectively than a lot of literature does.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I have two lists here. One is something I want to keep private and the other I don’t feel like organising. But if pressed: Agota Kristof, Dennis Cooper, Alain Robbe Grillet, Yukio Mishima, Djuna Barnes, Kathy Acker, DH Lawrence, Cormac Mccarthy, Faulkner, Ballard, Gaddis.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I don’t know, finish the next book and then know what to do with it.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I think writer, as an identity, is best kept secret. You have to earn enough money to live and then you have to sacrifice something else to write. Unless you’re lucky. If you’re not lucky you have to be careful what you choose to sacrifice or you may just become unbearable. You risk that any time you talk or think about your writing. Being a writer is just choosing to spend time creating something that may only have value to you but which you have to believe communicates something or has any effect on the world.

I think its unhealthy but true that I can’t imagine not writing.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

At a practical level, it’s the cheapest artform. It’d be amazing to work in film, sculpture, conceptual art but it’s the difference between football/soccer and tennis in terms of the equipment and space needed. Language is available and all you have to do is find a way to make it interesting. And writing is the closest thing to telepathy we have so how can it not be interesting?

Writing is also independent in a way that doesn’t rely on having a personality. People don’t really talk about personality any more. Which is a shame because maybe it offers a more charming way out of identity? Anyway, i digress. I want to be invisible to myself. That’s what The Autodidacts is doing.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Three books to cheat and in no specific order: The Employees, Olga Ravn. I wished, Dennis Cooper and Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor.

Last great film. I don’t know. I’m out of touch.

19 - What are you currently working on?

The final, I think, draft of my second novel ‘How I Killed The Universal Man’ and playing around with the beginnings of a third.

September 29, 2022

Canthius #10 : guest edited by Sanna Wani

I was going to rest my hands this afternoon

but they wanted to make something for you I was going to rest in the full sun fold myself into a neat nap shape always I asked for you ran ahead of you asking when if I held you again would I need anything that takes up more space than I could possibly live every time somehow I still ended up with more before I moved you could I wait for you to return to me I am not very patient (Emily Lu)

I’ve always enjoyed going through issues of

Canthius: feminism & literary arts

[although admittedly I haven’t offered a review of an issue of some time; see my review of issue two here and issue three here and issue seven here and even the interview I did with founding co-editor/publisher Claire Farley after the first issue landed here], and this new issue, guest edited by Sanna Waniwith artwork by Eryn Lougheed, offers up an array of stunning new work by a mound of writers both new and familiar: Emily Lu, Sennah Yee, Chimwemwe Undi, M.A. Blanchard, Joanna Cleary, Terrence Abrahams, Jaeyun Yoo, nanya jhingran, Hua Xi, Elizabeth Mudenyo, Dessa Bayrock, Cecil Choi, Devon Rae, Akshi Chadha, Sarah Ghazal Ali, Lina Wu, Hadiyyah Kuma, I.S. Jones, Malvika Jolly, Cassandra Myers, emilie kneifel, Samantha Martin-Bird, Hajjar Baban, Sara Elkamel, Ryanne Kap, Victoria Mbabazi, Yi Wei, ava hofmann, Natalie Lim, Alyza Taguilaso, Conyer Clayton and Hajera Khaja. With a focus on emerging writers (it would seem), it is always interesting to see different writers expand their roles, so I’m appreciating Wani taking on such a project (although admittedly I’m surprised the issue doesn’t include a biography for her as well, to give a reader unfamiliar with her work the opportunity for context; it seems a bit of a disservice to her work as guest editor. I offer, instead, our recent ’12 or 20 questions’ interview). As she writes to open her ”Editor’s Note”:

I’ve always enjoyed going through issues of

Canthius: feminism & literary arts

[although admittedly I haven’t offered a review of an issue of some time; see my review of issue two here and issue three here and issue seven here and even the interview I did with founding co-editor/publisher Claire Farley after the first issue landed here], and this new issue, guest edited by Sanna Waniwith artwork by Eryn Lougheed, offers up an array of stunning new work by a mound of writers both new and familiar: Emily Lu, Sennah Yee, Chimwemwe Undi, M.A. Blanchard, Joanna Cleary, Terrence Abrahams, Jaeyun Yoo, nanya jhingran, Hua Xi, Elizabeth Mudenyo, Dessa Bayrock, Cecil Choi, Devon Rae, Akshi Chadha, Sarah Ghazal Ali, Lina Wu, Hadiyyah Kuma, I.S. Jones, Malvika Jolly, Cassandra Myers, emilie kneifel, Samantha Martin-Bird, Hajjar Baban, Sara Elkamel, Ryanne Kap, Victoria Mbabazi, Yi Wei, ava hofmann, Natalie Lim, Alyza Taguilaso, Conyer Clayton and Hajera Khaja. With a focus on emerging writers (it would seem), it is always interesting to see different writers expand their roles, so I’m appreciating Wani taking on such a project (although admittedly I’m surprised the issue doesn’t include a biography for her as well, to give a reader unfamiliar with her work the opportunity for context; it seems a bit of a disservice to her work as guest editor. I offer, instead, our recent ’12 or 20 questions’ interview). As she writes to open her ”Editor’s Note”: When we began thinking about this issue, Leah, Ashley, and I agreed that we would forego a theme. We agreed that we wanted to see what came in—and what we loved—to find a theme by chance rather than call. To see what emerged, rather than to coax anything in particular out of the world. The chance to edit this issue was an enormous gift. You know that saying, how you read is how you write? I feel gifted with a new awareness of how to love poetry, which is in all writing, the particular quality of my love, of poetry’s music, and so the world’s, through these writers.

Part of what is interesting, as I move through this issue, is the number of short and uniquely sharp prose poems that appear here, including pieces by Emily Lu, Sennah Yee, Terrence Abrahams and Devon Rae, through her two poems “Conversation with My Lips” and “Conversation with My Tail.” As the latter reads in full: “you are stunted, cut short, hard nub. But sometimes, I sense a quiver, a kind of stirring. The unfurling of your shadow. I long to drape you over me, feather boa, to use tip to text the air. I long to speak through you, old tongue, ripped out.” I’m enjoying the thread that sits through the issue, of a handful of different poets offering short, lyric bursts of prose poems, and curious at how these particular submissions found themselves into and across this particular issue. Another highlight, in an issue of highlights, is Pakistan-born Afghan Kurdish poet Hajjar Baban, a 2021 PD Soros Fellow and MFA in Poetry candidate at the University of Virginia.

What I’ve Since Learned of Mountains

The language a sun unspoken. Hanging in the air,

my father’s brother’s death. The sword, a missed

prayer. Rocks and my instinct

against reason. Why a Kurdish joke

exists, a fire in the celebration. Those gowns

you’ll never wear. Lavender grown there. The distance,

the name of no country found.

Also, Eryn Lougheed’s artwork throughout the issue provides a fascinating counterpoint to the writing, setting lyric aside lyric, thematically linking to the conversations that guest editor Wani invites through her particular curation. As Wani asks near the end of her opening note: “What would you name the theme of this issue, dear reader? You are the you I am always chasing after all, inviting into these pages. I’ll let you have the last word. I’m interested to know what you choose.” So, basically: this is a journal you should be paying attention to. And you know they’ve a bunch of extra content online as well, yes?

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)

Forge, forget, lovely, lonely. I need my mind pure and my body expired. I want to devour this meal whole and not feel empty. I need to be better than real. I want you to look at me all the time. (Sennah Yee)

September 28, 2022

Danni Quintos, Two Brown Dots

Something from Nothing

It feels like we’re doing everything

in preparation for instead of

to distract ourselves from

pregnancy. Yes, I wish I was

nauseous & constipated, I wish my ankles

would swell, my feet wide as skis.

Zach is planting & cultivating

all the space we have outside:

greens, fruit trees, root vegetables,

climbing peas & herbs whose leaves

take lacy doily shape. I am turning

long lines of wool into cloth: knots

knitting with bamboo needles while I watch

everything my TV suggests. This is self

-reliance. Reproduction & production,

something growing where there didn’t

before seem to be space.

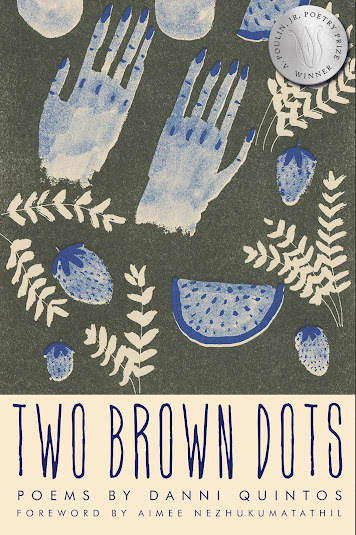

Selected by Aimee Nezhukumatathil as the winner of the A. Poulin, Jr. Poetry Prize is the full-length poetry debut

Two Brown Dots: Poems

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2022) by “Kentuckian, a mom, a knitter, and an Affrilachian Poet” Danni Quintos. Her first-person explorations and recollections write around and through a self-determination and self-creation, seeking answers to a space she requires to singularly establish; illuminating lyrics around memory and being, offering answers as best as she is able, in due course, due time. Set in three sections—“Girlhood,” “Motherhood” and “Folklore”—Quintos writes across the length and breadth of lived experience, from watching her father from a distance, summers and childhood crushes and living as an awkward youth, to the experiences of pregnancy and eventual motherhood. She offers stories of her connections to the Philippines, writing of a familial background she simultaneously holds and can’t help but carry, offering, as part of the poem “Possible Reasons My Dad Won’t Return to the Philippines,” “What if he remembers everything [.]” A few lines further, as the poem ends: “[…] the little boy in him left / here with all the cousins, no one / to call nanay or tatay, alone, / the shape of him on a mattress / the version of him that stayed.” She writes of differences, from the ways in which most (if not all) teenagers feel as outsiders, to the consequences of racism, reacting to boundary-making micro-aggressions offered for no reason other than the colour of her skin. “I didn’t yet / understand. And every summer after,” the poem “Brown Girls” ends, “a whirring // reminder that I didn’t belong here, a little song / sung at me by the bodies that slept for years // underground. How we couldn’t see what he saw: / two brown girls under a white couple’s roof.” In certain ways, Two Brown Dots is a collection of poems entirely centred around the body, and how those bodies are experienced, both from outside and within, offering physical responses through the lyric, from adolescence to the fact of living in a predominantly Caucasian space. Her poems are sly and smart, curious and rife with detailed narrative. In the poem “Boobs,” from the opening section, she reveals the phrase from whence the collection finds its title, writing: “In fifth-grade gym class I ran into the padded walls / and felt like marbles bruised me under my shirt. That night // I dreamt they were big & flouncy and I looked at myself / in a mirror, laughing. In a field at recess I did a cartwheel // and Elliott Fess saw my shirt fly up to my chin. I’d forgotten / we were different now. When I asked, did you see anything? // he said, just two brown dots.” Through Two Brown Dots, Quinto manages optimistic poems on awkwardness, uncertainty and a feeling of displacement, packed with story, family and connection, offering observations, recollections and revelations, as one step immediately following another, building a home out of what might otherwise have seemed impossible. “We are two sisters in the middle / of the world where the sun paints us // bronze.” she writes, close to the end of the poem “Pond’s White Beauty.” Or, as Nezhukumatathil’s “Foreword” opens:

Selected by Aimee Nezhukumatathil as the winner of the A. Poulin, Jr. Poetry Prize is the full-length poetry debut

Two Brown Dots: Poems

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2022) by “Kentuckian, a mom, a knitter, and an Affrilachian Poet” Danni Quintos. Her first-person explorations and recollections write around and through a self-determination and self-creation, seeking answers to a space she requires to singularly establish; illuminating lyrics around memory and being, offering answers as best as she is able, in due course, due time. Set in three sections—“Girlhood,” “Motherhood” and “Folklore”—Quintos writes across the length and breadth of lived experience, from watching her father from a distance, summers and childhood crushes and living as an awkward youth, to the experiences of pregnancy and eventual motherhood. She offers stories of her connections to the Philippines, writing of a familial background she simultaneously holds and can’t help but carry, offering, as part of the poem “Possible Reasons My Dad Won’t Return to the Philippines,” “What if he remembers everything [.]” A few lines further, as the poem ends: “[…] the little boy in him left / here with all the cousins, no one / to call nanay or tatay, alone, / the shape of him on a mattress / the version of him that stayed.” She writes of differences, from the ways in which most (if not all) teenagers feel as outsiders, to the consequences of racism, reacting to boundary-making micro-aggressions offered for no reason other than the colour of her skin. “I didn’t yet / understand. And every summer after,” the poem “Brown Girls” ends, “a whirring // reminder that I didn’t belong here, a little song / sung at me by the bodies that slept for years // underground. How we couldn’t see what he saw: / two brown girls under a white couple’s roof.” In certain ways, Two Brown Dots is a collection of poems entirely centred around the body, and how those bodies are experienced, both from outside and within, offering physical responses through the lyric, from adolescence to the fact of living in a predominantly Caucasian space. Her poems are sly and smart, curious and rife with detailed narrative. In the poem “Boobs,” from the opening section, she reveals the phrase from whence the collection finds its title, writing: “In fifth-grade gym class I ran into the padded walls / and felt like marbles bruised me under my shirt. That night // I dreamt they were big & flouncy and I looked at myself / in a mirror, laughing. In a field at recess I did a cartwheel // and Elliott Fess saw my shirt fly up to my chin. I’d forgotten / we were different now. When I asked, did you see anything? // he said, just two brown dots.” Through Two Brown Dots, Quinto manages optimistic poems on awkwardness, uncertainty and a feeling of displacement, packed with story, family and connection, offering observations, recollections and revelations, as one step immediately following another, building a home out of what might otherwise have seemed impossible. “We are two sisters in the middle / of the world where the sun paints us // bronze.” she writes, close to the end of the poem “Pond’s White Beauty.” Or, as Nezhukumatathil’s “Foreword” opens: Danni Quintos knows how to create light. After so much darkness brought about by climate change, political strife, and, most recently, a global pandemic among other devastations. I’m so glad for this spark. I’m reminded of that old Rumi missive: “If light is in your heart, you will find your way home.” Quintos is a lighthouse when it comes to revealing essential truths about finding your way when you feel alone or misunderstood—our ability to feel lonesome can be just as equaled by our ability to find love, even in the most unexpected ways. This debut thrillingly gives us a triumphant vocabulary with which to make sense, celebrate, and ponder the wild and ecstatic bafflements of coming-of-age, and what it means to insist and cultivate a home for yourself (and others) with courage and grace.

September 27, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Lee Suksi

Lee Suksi’s first book,

The Nerves

(Metatron), won a 2021 Lambda Literary Award. They've written for art magazines and exhibitions, conducted interviews, crisis counselling, drawing classes, bookselling, astrological consultation. They are at work on several projects, including daily address at https://psychiclectures.substack.com.

Lee Suksi’s first book,

The Nerves

(Metatron), won a 2021 Lambda Literary Award. They've written for art magazines and exhibitions, conducted interviews, crisis counselling, drawing classes, bookselling, astrological consultation. They are at work on several projects, including daily address at https://psychiclectures.substack.com.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Probably the question I most frequently ask editors and other people is “does that make sense?” My central doubt. Hearing how people read The Nerves convinced me that I do.

Everything else will be a deepening of that reassurance. I’d like to let people know I understand what they mean too.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

No, I came to poetry first. I love what meaning is generated through beauty, silence, and contradiction. I love language at the level of the voice, then the sound, the pause, the word, the line. The scaffolds of genre at this point seem onerous, but I use them, for now, to convey sense. I don’t really think about storytelling unless I absolutely have to, which is less than you might think.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

My notes are non-stop and I try to sort them but they aren’t usually towards a particular project when they come down off my head. But everything comes from there. I guess writing is sorting them and making them make sense.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A sound becomes a sentence when there’s a collision, and so on. I admit to being kind of precious about books (The Nerves was gorgeously designed by Sultana Bambino) but when writing becomes commodity the writing part of that project is over.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love readings. The reading and listening parts. I love reading and being read to. I record myself while writing. I love the extra information conveyed by posture, dress, voice, atmosphere. And the audience’s stillness or noise. Reading is lovely and writing is simply not. Writing is bad posture and staring at the wall. It’s quarantine.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Is Voice theoretical? It’s nice when my theoretical concerns feel cosmic, like the social and the personality are gone and the Voice is a chorus. I wrangle those socials and individuals with genre but it’s exciting when they recede. It would be amazing to write without power or grief but they are always major.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Well they have lots of different roles. Medium, teacher, adjudicator, observer, entertainer are a few. I find it hard to relate normally when compulsively writing. Ironically, I don’t think I’m alone in that. Maybe I can put some pressure on that.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I have to be ready, but at their best the editor is the first sense-maker! Amazing. I’m in awe of people who share their work at all stages.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I took a workshop with Leah Sophia Dworkin where she shared a technique for envisioning where you store your memories, and how to tuck them away when you’re done with them. Until that point I’d been going through a period where writing felt really overwhelming and even distressing, a boundless and vulnerable endeavour. That was great. The container doesn’t have to be a strict form.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

No, I’m not regular but I do it every day. If I do it well it usually happens when I have a free afternoon and the light is right. I write in bed with my cats if I feel evil. Or I go to the Hart House Library (hot tip). I’m newly obsessed with how unhealthy writing tends to be, how much ruminating, drinking coffee and alcohol, scrunching the body. No wonder it can get a bit morose and tortured. I want my writing to be embodied so I try to get into the body with meditation, stretching, music. Sex if I’m feeling committed. The only thing I don’t like about the library is I can’t do Wheel Pose without inhibition. My best advice to writers is to take care of your body. It moves your head. So, note to self, get out of bed.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

The world is too much with me and I’m chronically over- rather than understimulated, but I guess if I feel confused I read, let the notes come out of my head, return.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Boys. All my past and current homes. Even when I lived with my best girlfriend, but then it smelt like patchouli too.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I love to draw and I find ease there, probably because it’s more in conversation with myself and less others so I have less responsibility. The freedom of association in that kind of mark making, the immediacy of emotion in a line, taught me a lot about what’s important to me in writing and in general. In art school I only wrote ekphrastically and I think the care of conveying the world while surrendering to its mystery (artists hate having their work explained but need it to be described) comes from there.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I’m reading very distractedly since I started working in a bookstore, but writers I carry around with me (quite materially) are Eileen Myles, Joshua Whitehead, Liz Howard, Dionne Brand, David Wojnarowicz, John Wieners, Renee Gladman, Tamara Faith Berger, Hannah Black, Aisha Sasha John, Prathna Lor, Lucy Ives, Lucy Ellmann, Shiv Kotecha. Kafka, Berlant, Sedgwick, Davis, Carson, Dickinson, Woolf, Weil. Notley, Mayer, Niedecker. Woof.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Reflecting on that list, read more work in translation, read more work from the ancient world.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

A helping profession for sure. I used to have a lot of guilt about the arts, now I feel like they’re one side of a call and response. I still feel like my most instructive experiences are listening to or caring for people. Reading is like the desultory, or preparatory way of doing that. Writing at its best distills something from all different kinds of experiences, alchemizes, offers something weird and ripe. I’m not sure about that mirror-to-the-world metaphor, if it offers a clear picture. It’s more like cultural production is a twisted, distinctive little farm grown in the soil of experience, the compost of living. I believe in it a bit more now, I believe that my connected experiences came from reading as much as anything else.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I love to draw but I’m in my thirties now and I think I’ll have a lifelong struggle with the substance of the world, with caring about lasting materiality, with the value of objects and the realities of bureaucracy and money. That eliminates a lot of professions and visual artist is one of them. Writing has cheap overhead and needs no storefront. And it can be joyful.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Darryl by Jackie Ess. I’m loving the new season of Couples Therapy . That show is nuts.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Mothers and daughters, fathers and sons, poetry about everything, and my daily Psychic Lectures: https://psychiclectures.substack.com

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

September 26, 2022

new from above/ground press: twenty-two new/recent (April-September 2022) titles,

Happy September! What! How did we get here? And we'll see you at the ottawa small press book fair on Novmeber 12th, yes?

Happy September! What! How did we get here? And we'll see you at the ottawa small press book fair on Novmeber 12th, yes?TWENTY-TWO NEW TITLES: Light Makes a Ruin, by Geoffrey Nilson $5 ; Felines, which sounds like feelings, by Genevieve Kaplan $5 ; Motion & Force, by Melissa Spohr Weiss $5 ; too many words, by Lori Anderson Moseman $5 ; GLITCH APPLE, by Christopher Patton $5 ; Dating Pete Davidson, by Leigh Chadwick $5 ; Report from the (Sarah) Mangold Society, Vol. 1 No. 1 $7 ; Report from the (Gregory) Betts Society, Vol. 1 No. 1 $7 ; Report from the (Phil) Hall Society, Vol. 1 No. 1 $7 ; FALSE NARRATIVES, by Ken Norris $5 ; Report from the (Cameron) Anstee Society, Vol. 1 No. 1 $7 ; Reading The Great Classics Of Canlit through Book 5 of bpNichol’s The Martyrology, by Grant Wilkins $5 ; Natural Man, by N.W. Lea $5 ; Silts, by Jed Munson $5 ; AN ENVELOPE OF SILENCE, Some Short Fiction 1977-1989, by David Miller $5 ; looping climate, by Matthew Gwathmey $5 ; Report from the (Monty) Reid Society, Vol. 1 No. 1 $7 ; in the shadows, by Michael Boughn $5 ; west coast shorts, by Laura Kelsey $5 ; English Garden Bondage, by Russell Carisse $5 ; In-Between, by Saba Pakdel $5 ; Tomorrow's Going to be Bright, by Jérôme Melançon $5 ; (see the prior list of 2022 titles here

keep an eye on the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material; and 2023 subscriptions (THE PRESS' THIRTIETH YEAR) announce at the end of the week! (although at the same rates as last year, if you want to get in on the action early,

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

April - September 2022

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; in US, add $2; outside North America, add $5) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9. E-transfer or PayPal at at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com or the PayPal button (above). Scroll down the extensive list of names on the sidebar (many, many things are still in print).

Review copies of any title (while supplies last) also available, upon request.

Forthcoming chapbooks by: George Bowering, Joseph Donato, Chris Johnson, Ben Jahn, Leesa Dean, Lindsey Webb, Jason Heroux, Nick Chhoeun, Grant Wilkins, Isabel Sobral Campos, Mark Scroggins, Laura Walker, Adrienne Adams, Jordan Davis, Jason Christie, Andrew Gorin, Marita Dachsel, Stuart Ross, Angela Caporaso and Isabella Wang, an issue of G U E S T [a journal of guest editors] edited by Sara Lefsyk and issue thirty-five of Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal]! (and probably a bunch of other things, honestly).

and can you believe the press turns THIRTY YEARS OLD next year? gadzooks!

stay healthy! be safe! be nice to each other,

September 25, 2022

Sophie Crocker, Brat

self-portrait in aries

i have been so alive.

in an open shirt i set mint sprigs on fire.

we brush each other’s teeth in the speckled mirror.

my limbs made yours in watercolor.

you can bow a cherry stem with your tongue;

i can keep a chick alive in the slickness of my cheek.

yes, i am a pet for care.

little body all skeletal with rain.

it’s so easy not to break me once you know that i am breakable.

you were hungry.

i was hungry.

& the thing to eat was me.

The full-length poetry debut by Sophie Crocker, “a writer and performance artist based on stolen Songhees, Esquimalt and WSANEC land,” is

Brat

(Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2022), a scattering of poems that work to explore and feel out a variety of self-definitions and self-determinations, through which to see which one or ones best fit. “i don’t want to miss anything before i have to.” they write, as part of the opening poem, “venus in cancer.” “i / can’t even finish a podcast, can’t even keep a middle name.” There is such delightful and open uncertainty infused in Crocker’s narratives, and their expositions flick at a moment’s notice between meditation and flailing, wild exuberance and cool wisdoms, so many of which seem hard-won. The same poem, after weaving and bobbing a meandering pace, ends with the clarity of such a wonderfully-paced and slightly-open conclusion: “actually, my last meal will be breakfast. / after breakfast i will take a long, / long walk.”

The full-length poetry debut by Sophie Crocker, “a writer and performance artist based on stolen Songhees, Esquimalt and WSANEC land,” is

Brat

(Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2022), a scattering of poems that work to explore and feel out a variety of self-definitions and self-determinations, through which to see which one or ones best fit. “i don’t want to miss anything before i have to.” they write, as part of the opening poem, “venus in cancer.” “i / can’t even finish a podcast, can’t even keep a middle name.” There is such delightful and open uncertainty infused in Crocker’s narratives, and their expositions flick at a moment’s notice between meditation and flailing, wild exuberance and cool wisdoms, so many of which seem hard-won. The same poem, after weaving and bobbing a meandering pace, ends with the clarity of such a wonderfully-paced and slightly-open conclusion: “actually, my last meal will be breakfast. / after breakfast i will take a long, / long walk.” Crocker engages with numerous poems around situating, composing multiple portraits-within-moments across an immediate self, including “self-portrait as angel baby,” “self-portrait in leo,” “self-portrait in virgo,” “neptune in capricorn,” “self-portrait in aquarius” and “the best thing about me.” They offer moments and morsels of and around perspective, and portraits around all twelve astrological signs. “i should like to be dismantled.” they write, to open “self-portrait of the obsessive compulsive / in isolation,” “a white onion. / my skull still soft. the apartment half-moved-out.” The ways through which Crocker constructs a book-length in-process portrait, working line by line, poem by poem, is fascinating; and Crocker’s staccato-accumulations are, at times, combative, meditative, lyric, self-depreciating, self-aware, sly, hilarious and deeply curious, seeking answers to impossible questions that are still, in themselves, to find their final form. “there were too many corners / in too many rooms.” they write, near the end of “that summer i thought i was gautama buddha,” “my rage monsooned / into every flesh i had.”