Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 111

October 14, 2022

Tatiana Luboviski-Acosta, La Movida

SAW YOU IN MY NIGHTMARES /

SEE YOU IN MY DREAMS

If you try to cross

a river wearing a veil

of concrete and glass,

how long will it be before

the bomb goes off? If you wan

der the fermented

fields of soap, blindfolded and

with a daisy in the

barrel of your rifle, how

long will it be until you’re

aiming at yourself?

Tell me, how many hands did

you have to hold when

you leaned forward to unlock that

door? My friend, who died a thou

sand deaths. It takes a

true coward to resist re

sisting while dan

cing in the dark.

I am very much enjoying the dark jabs and joyful play of language, revolution and compressed, packaged time of

La Movida

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2022), San Francisco-based “queer anarchist Nicaragüense American artist” Tatiana Luboviski-Acosta’s second full-length collection, following

The Easy Body

(Timeless, Infinite Light, 2017). In poems rife with chaos and insurrection, trauma and passionate resolve, set amid occasional black and white sketches, Luboviski-Acosta’s lyric is grounded in a poetic powered through collective strength, one that runs through threads of Spanish-English bilingualism, language and politics, left wing radicalism and class struggle. Luboviski-Acosta opens the collection with a poem referencing drug addiction and mental illness, including their father, who drove into the ocean and lived. “he survived.” they write, “and then, / he was able / to torture us / with his aristocratic ascetic drama / for years to come.” There is some dark territory covered through these poems, one that moves as much through an uncertainty as a particular kind of resolve, from the triptych “THREE BISEXUAL TALES” to an array of poems named after individuals, including a poem that shares the author’s own name. As that particular piece opens, offering as best an ars poetica across two-plus pages as anything else I’ve seen: “I want the freedom / to make art about nothing / in particular. / Nothing is stopping me— / nothing, except for you.” It is a remarkable poem amid an array of remarkable poems, pinballing a strike across sound and rhythm, divided words and the lingering effects of a divided, fractured history. These are poems forged in fire, able to give as good as it gets. “Alive out of spite, / a general strike,” they write, to open the poem “AMARANTH,” “a knife / to upper lip, a bright laughing clit, and raven / ous walls all throb for the means // of production.” These poems are witty, incredibly smart and playful, and hold incredible weight, stitched together through romantic love, delightful optimism, nightmares and scar tissue. Or, as Luboviski-Acosta’s namesake poem closes: “If you can’t already // tell, my entire last name is / a narrative of aban / donment—it could have / been worse. I could have been that // deep breath, that striking / lingual flirtation before // the objection.”

I am very much enjoying the dark jabs and joyful play of language, revolution and compressed, packaged time of

La Movida

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2022), San Francisco-based “queer anarchist Nicaragüense American artist” Tatiana Luboviski-Acosta’s second full-length collection, following

The Easy Body

(Timeless, Infinite Light, 2017). In poems rife with chaos and insurrection, trauma and passionate resolve, set amid occasional black and white sketches, Luboviski-Acosta’s lyric is grounded in a poetic powered through collective strength, one that runs through threads of Spanish-English bilingualism, language and politics, left wing radicalism and class struggle. Luboviski-Acosta opens the collection with a poem referencing drug addiction and mental illness, including their father, who drove into the ocean and lived. “he survived.” they write, “and then, / he was able / to torture us / with his aristocratic ascetic drama / for years to come.” There is some dark territory covered through these poems, one that moves as much through an uncertainty as a particular kind of resolve, from the triptych “THREE BISEXUAL TALES” to an array of poems named after individuals, including a poem that shares the author’s own name. As that particular piece opens, offering as best an ars poetica across two-plus pages as anything else I’ve seen: “I want the freedom / to make art about nothing / in particular. / Nothing is stopping me— / nothing, except for you.” It is a remarkable poem amid an array of remarkable poems, pinballing a strike across sound and rhythm, divided words and the lingering effects of a divided, fractured history. These are poems forged in fire, able to give as good as it gets. “Alive out of spite, / a general strike,” they write, to open the poem “AMARANTH,” “a knife / to upper lip, a bright laughing clit, and raven / ous walls all throb for the means // of production.” These poems are witty, incredibly smart and playful, and hold incredible weight, stitched together through romantic love, delightful optimism, nightmares and scar tissue. Or, as Luboviski-Acosta’s namesake poem closes: “If you can’t already // tell, my entire last name is / a narrative of aban / donment—it could have / been worse. I could have been that // deep breath, that striking / lingual flirtation before // the objection.”

October 13, 2022

Spotlight series #78 : Jennifer Baker

The seventy-eighth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker.

The seventy-eighth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr and Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown.

The whole series can be found online here.

October 12, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Eve Wood

Eve Woodis the author of five books of poems, Love’s Funeral, and Six, (published by Cherry Grove Collections), Artistic Children Breathe Differently, (Hollyridge Press), a chapbook entitled Paper Frankenstein published by Beyond Baroque Press and Correspondence (Gegensatze Press, Austria) Her newest collection A Cadence For Redemption is new from Del Sol press. Her work has appeared in numerous journals including The Best American Poetry 1997, The New Republic, The Denver Quarterly, Triquarterly, Poetry, Witness, The Wisconsin Review, The Massachusetts Review, The Greensboro Review, Exquisite Corpse, The Florida Review, The Antioch Review, and many others. She has twice been a guest on KPFK’s Poet’s Café hosted by MC Bruce. Wood is the recipient of the Jacob Javits Fellowship and a Brody Grant. Wood writes art criticism for ArtUS, Flash Art, Artillery, Tema Celeste, Artext, Artweek, and Artnet.com, Bridge Magazine, Latinarts.com, and Art Papers etc. Also a visual artist, Wood was represented for six years by Western Project and for three years by Susanne Vielmetter; LA Projects. She is currently represented by Track 16 Gallery. She has exhibited nationally and internationally and her work is included in several collections including Eileen and Peter Norton, The Weatherspoon Museum, and the Laguna Art Museum.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

EWOOD: My first book was called Love’s Funeral, and it didn’t really change my life per se, (as is often the case with books of poems) very few read it, however, it was a crucial experience because Mark Strand wrote the back-jacket blurb and I remember I kept pinching myself in disbelief at his kind words.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

EWOOD: Both my parents were poets and actually met at the MacDowell Colony, so I suppose you could say it runs in the family.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

EWOOD: Usually, and hopefully, lightning strikes, but that is a rare occurrence. I think in terms of “projects,” “concepts” rather than individual poems. Each project has a different trajectory, pulse and rhythm – some, as was the case with my most recent book written in the “fictive” voice of Abraham Lincoln, came all at once with a tremendous urgency, but I credit that to the incredibly difficult times we currently find ourselves living through. It was a visceral experience, at times so palpable, it almost felt like Lincoln was there beside me, shaking his head in astonishment.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

EWOOD: I am usually struck by an idea, or sometimes a line occurs to me and I build from there. For example: the most recent school shooting left me feeling so hopeless that I began thinking about all the rage brewing in today’s young men, and thus a poem entitled “To All the Angry Boys,” came into being. I usually work from a specific concept, an overriding theme, so I suppose, yes, I work on new “books” from the beginning.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

EWOOD: I LOVE doing readings, but sadly, rarely get the opportunity. A century ago, when I was young, I studied acting and I think that experience really helped me understand the importance of being able to read one’s own work in public. Being a good reader of poetry is a cultivated skill that not many poets have mastered. I also had the opportunity of going to see some really stellar and personable poets read their own work – Mark Strand, Galway Kinnell, Brigit Pegeen Kelly and Tom Lux, and this also helped me hone my own reading skills. For me, humor is key – the stories you tell between the poems are as important as the poems themselves.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

EWOOD: I am old fashioned. My poems are my way of explaining my life experience back to myself. It’s a reiteration of joy, grief, sorrow, shame, love, all the qualities that make us human. I do not have any specific theoretical concerns in my work. I believe the best poems are a translation of human experience made accessible through a specificity of language. For me, theoretical poems deliberately distance the reader from the poem, which is antithetical to the purpose of any poem – to reach out and grab you by the throat, or lull you deeper into yourself, or as the great Franz Kafka once said, “A book must be an ice-axe to break the seas frozen inside our soul.”

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

EWOOD: The role of the writer has always been the same as it is a timeless profession, one that is ¼ shaman, ¼ renegade, ¼ sage and ¼ lover – ultimately writers are those among us who are compelled to tell the truth no matter the circumstances. This “truth” is universal and available to us all, but great writers are conduits to the unknown, to mystery, beauty and salvation, and we need them now more than ever.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

EWOOD: I always enjoy the process of working with another set of eyes as it usually helps me to see where the writing could be better, etc.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

EWOOD: The best piece of advice I ever got was from the poet David St. John who told me to be selective when showing my work to others. He told me to find one or two trustworthy readers and to really cultivate those friendships. Those relationships are like gold.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to criticism to visual art)? What do you see as the appeal?

EWOOD: I’ve been engaged in all these various art forms for a long time, and when I was at Cal Arts, I began writing and the practices grew together. I think in some way they feed each other as poetry is a visual language.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

EWOOD: Because we have six dogs, three birds, and one cat, AND I work a full-time teaching job, I am always jockeying my various responsibilities, so I literally carve out time where I can. Sometimes it’s only an hour, but I’ve learned to modulate my creativity, and many times I write the poem in my head as I am doing my daily chores and then sit down at night and set it all down. It’s not the best creative model, but it seems to work.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

EWOOD: I read the work of my favorite writers, and that usually jump starts my creative juices.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

EWOOD: There really isn’t a fragrance I associate with home. Maybe horse poop because I used to ride horses when I was a kid and have many good memories of those days.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

EWOOD: I would say that visual art has had a tremendous effect on my work. Because I am also a visual artist, there is a lot of cross over between these genres for me. I often listen to music when I am writing and more times than once can claim a “happy accident” when I have misunderstood a lyric and it becomes part of a poem!

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

EWOOD: Being an art critic, I read a lot of art criticism – Peter Schjeldahl, Michael Fried, Rosalind Krauss, Jerry Saltz, Clement Greenberg and Susan Sontag to name a few. I also read fiction when I have the time.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

EWOOD: I have not travelled very much in my life and am consciously trying to change that. In 2019 I went to Berlin and Vienna and this year Paris. My goal is travel once a year. Hopefully one day I can got to the Giraffe Manor Hotel in Nairobi.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

EWOOD: Since I’m not good at anything else other than art making and writing, I probably would have been some sort of animal trainer, i.e. working with animals in some capacity, but I could just as easily have wound up a bum. LOL!

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

EWOOD: In my experience, writing is never a choice. It’s a compulsion that cannot be quelled by any other means. I tell my students all the time – “If you can do ANYTHING else, do it because the life of a writer is difficult, painful, poverty stricken, etc. and you must feel in your bones that you NEED to be doing this – that you will practically die if you can’ t set pen to paper.

What made me write was that I could not notwrite.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

EWOOD: George Saunders Lincoln in the Bardo – absolutely brilliant. Last great film was Lamb directed by Valdimar Johannsson.

20 - What are you currently working on?

October 11, 2022

the book of smaller : some reviews, some interviews/podcasts, (oh, and ive some new chapbooks out,

I should have been mentioning, I suppose, some of the reviews coming in for the book of smaller (University of Calgary Press, 2022) (I still have copies for sale, don'chaknow). Kim Fahner, Margo LaPierre, and Jérôme Melançon collaboratively did a really stunning one, over at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. Jami Macarty did a really neat one over at Miramichi Review (although I should point out that my references to Sainte-Adèle were to the village in Quebec, and completely unrelated to Vancouver poet Adèle Barclay). Benjamin Niespodziany provided a short review via Neon Pajamas, which was pretty cool. And there are even some wee reviews over at the book's Goodreads page! What! I mean, even the CBC recommends you read this book, so what are you gonna do?

I should have been mentioning, I suppose, some of the reviews coming in for the book of smaller (University of Calgary Press, 2022) (I still have copies for sale, don'chaknow). Kim Fahner, Margo LaPierre, and Jérôme Melançon collaboratively did a really stunning one, over at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. Jami Macarty did a really neat one over at Miramichi Review (although I should point out that my references to Sainte-Adèle were to the village in Quebec, and completely unrelated to Vancouver poet Adèle Barclay). Benjamin Niespodziany provided a short review via Neon Pajamas, which was pretty cool. And there are even some wee reviews over at the book's Goodreads page! What! I mean, even the CBC recommends you read this book, so what are you gonna do?Susan Johnson interviewed me on the collection on her Friday Special Blend recently, so be sure to listen to the podcast of that. Andrew French also interviewed me for the same via his podcast, Page Fright: A Literary Podcast.

Amanda Earl also interviewed me recently for her podcast, The Small Machine Talks, on the recent 29th anniversary of above/ground press. Pearl Pirie conducted a brief interview with me around the new book, and I answered Colin Dardis' questions via his Fill Your Books! Oh, and I answered Michael Murray's questionnaire recently via his Galaxy Brain (I should probably point out that I post links to all of my interviews here as they appear, in case you ever wonder about those).

Also, did you see that Greg Bem provided a wee review via Goodreads of my chapbook, Autobiography (above/ground press, 2022)? Oh, and I've a new chapbook out now with paper view books, 4 poems on receiving the phizer covid-19 vaccine (second shot, (2022) (my first chapbook published in Portugal!), and another small item out with Kyle Flemmer's The Blasted Tree, Canadian Poem (2022). And I've a chapbook forthcoming with Rose Garden Press as well, sometime next month. There's probably other stuff I'm forgetting about right now, but these are some highlights. I mean, there is just so much going on! What!

October 10, 2022

Kerri Webster, LAPIS

Primrose, Orchid, Datura

To say I lived on honeycomb is not enough. I lived

on milkfat, garnets, whiskey bottles under the bed,

lotion pearlescent on pink skin. I slept half the day,

woke late, ate ridiculous bouquets, milked austerity

for gorgeousness – blossoms collected in jars,

granite thieved from silt. I napped and architected

a decadent inwardness. I did not know that the Christbody

would take up residence in the next room, in a hospice

bed, until the whole house smelled like nightblown

Gethsemane, or that this would go on until the world

ran out of sponges from its acrid seas. Once I was a girl

who wore feathers and ivory, a woman who let

the tap run in the desert past all decency. Forgive me.

The fourth full-length poetry title by Boise, Idaho poet Kerri Webster, following

We Do Not Eat Our Hearts Alone

(2005),

Grand & Arsenal

(2012) and

The Trailhead

(2018) [see my review of such here], is

Lapis

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2022), a collection that “writes into the vast space left by the loss of three women: her mother, a mentor, and a friend. What emerges in the vast space grief makes is a newfound sense of living with the dead, of a matrilineal lineage both familial and poetic.” Moving across structures and syntax, from prose poems to line-breaks, compact bursts and extended narratives, the book is shaped in four numbered poem-sections, opening with a single prose poem, “oh each poet’s a / beautiful human girl who must die,” and ending with a pair of closing elegies, “Elegy” and “Eyelets.” Webster’s book-length Lapis sits as an elegy unto itself, and works less to describe or contain her experiences than allow her grief to overflow, articulated across and through an assemblage of shaped lyrics. The extended sequence “Seer stone,” for example, works through elements of care, through her mother’s dying and death, and the ways through which time shifts, stops and unfolds (elements I myself recall, during my own father’s extended period of similar), as she writes: “Year of: // how long have I been asleep / what has transpired / why [.]” Or, further on:

The fourth full-length poetry title by Boise, Idaho poet Kerri Webster, following

We Do Not Eat Our Hearts Alone

(2005),

Grand & Arsenal

(2012) and

The Trailhead

(2018) [see my review of such here], is

Lapis

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2022), a collection that “writes into the vast space left by the loss of three women: her mother, a mentor, and a friend. What emerges in the vast space grief makes is a newfound sense of living with the dead, of a matrilineal lineage both familial and poetic.” Moving across structures and syntax, from prose poems to line-breaks, compact bursts and extended narratives, the book is shaped in four numbered poem-sections, opening with a single prose poem, “oh each poet’s a / beautiful human girl who must die,” and ending with a pair of closing elegies, “Elegy” and “Eyelets.” Webster’s book-length Lapis sits as an elegy unto itself, and works less to describe or contain her experiences than allow her grief to overflow, articulated across and through an assemblage of shaped lyrics. The extended sequence “Seer stone,” for example, works through elements of care, through her mother’s dying and death, and the ways through which time shifts, stops and unfolds (elements I myself recall, during my own father’s extended period of similar), as she writes: “Year of: // how long have I been asleep / what has transpired / why [.]” Or, further on: In May my mother decided not to get out of bed again, her lungs two oil slicks. What seemed like a sudden decision was, looking back, her waiting for the academic year to end so that I could be there to administer the doses, arranging the pillows, watch her mind go. This took four months, time out of time, time outside of language, time both sides of the veil, and when it was done every cell in my body was transfigured. I will never again be that exhausted. I will never again be that God-struck.

Webster touches upon elements of faith and ritual, including early Mormon history: elements that can’t help but seek the surface when moving through the dying and death of a parent: memories of past events, and even past selves, through the ether. Some reminders are startling for their distance, after all; even further, more startling for how close they sit to the surface. “The Lord bless you before the light.” she writes, in the same sequence. “I spend a fair measure of time these days / talking to the dead. Sometimes all I have to do is roll my eyes.” Webster’s title refers to lapis lazuli, a deep blue coloured stone used for thousands of years to make beads and gemstones, among other things (think: the Ishtar Gate). Her title suggests value found, value shaped and ideas of not only age, but time passed, and passing. “The dead say Are you trying / to save someone again.” she writes, as part of the twenty-nine part fragment-sequence “So Many Worlds, So Much to Do,” a sequence that makes up the whole of the book’s third section, “No. On / the striped body of Christ / I swear I am not.”

October 9, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Amanda Larson

Amanda Larson

is a writer from New Jersey. Her first book,

Gut

, was selected by Jericho Brown as the winner of the Omnidawn First/Second Book Prize, and by Mark Bibbins as the winner of the Norma Farber First Book Award from the Poetry Society of America. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in the Michigan Quarterly Review, fugue, Washington Square Review, and other publications. She holds an MFA from New York University, and she lives in Queens, New York.

Amanda Larson

is a writer from New Jersey. Her first book,

Gut

, was selected by Jericho Brown as the winner of the Omnidawn First/Second Book Prize, and by Mark Bibbins as the winner of the Norma Farber First Book Award from the Poetry Society of America. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in the Michigan Quarterly Review, fugue, Washington Square Review, and other publications. She holds an MFA from New York University, and she lives in Queens, New York.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I really felt like it was necessary to write Gut before I wrote any other book; Gut lays out a theory of writing. I feel a bit more freedom, now, with what I am currently working on. That’s not to say it feels any less urgent, but there is less of a need to justify its existence.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I came to poetry through the band The Wonder Years, and their album based on Ginsberg’s “America.” I was very angry and I couldn’t take the pace of fiction or non-fiction, it was too slow, I was a teenager and everything had a kind of immediacy. I found that anger in the Beats and Charles Bukowski, and the immediacy in Richard Siken’s work.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I write every day. I have a huge Pages document that I write in, and I change out the document each year. When I’m working on prose poems, I move to a Word document. I like to write whole books, or projects, not just individual poems. I like something I can look at, that I can see growing, and see laying out a theory of thought. Some poems come all at once and some poems require months of revision. With the books, I want to create a kind of emotional arc.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I like to think of myself as a person who writes books. I am usually working on a book from the very beginning, though I do write individual, lineated poems. I really love how words sound and I love music. I like putting sounds together, and that is where the lineated poems start. With the larger projects I write the books that I want to read, and that I’m frustrated don’t already exist.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I did some readings in college and realized I hated the experience of reading and watching a whole room full of people murmur. That being said, I got more confident with them over the course of my MFA, but I don’t think they contribute to my creative process any more than existing and socializing contribute to my creative process. I love hosting parties and going to them and I would rather do that.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I believe that poetry allows for us to negotiate our relationship to impulse, through its manipulation of the breath. I am very concerned with how quickly we exert our impulses, especially our impulses towards violence and towards punishment, and how physical violence enables a kind of clarity, in that it alters physical reality in a very clear way. Gut was very concerned with the question of learned knowledge versus the knowledge gained through experience, and how trauma impacts our views towards how we are willing to live, and what we are willing to do. It was also very concerned with the extent of our individual control, especially over our desires. I want my reader to question their impulses and their judgments, and to redirect them to a kind of beauty.

My second book thinks about childhood and adolescence. There, I’m concerned with when an adolescent becomes culpable for their actions, and how and when we place blame on individual actors.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think it is very important for writers to believe in what they are saying, and to believe in a clear vision. That doesn’t mean every book has to be overwhelmingly inspirational, or even make narrative sense, but that the writer should be able to lay out a way of thinking about the world that has helped them, and can help others as a result.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I have a select handful of readers who are really essential to me. They are also some of the same people I talk through the guiding principles and questions of my work with, and who I am lucky enough to have as readers. I didn’t revise the manuscript of Gut significantly after its submission, but I am grateful for the editors at Omnidawn who were so attentive to my vision for the book.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

When I was about to go to my MFA I was incredibly nervous, because I didn’t—and still don’t—have a “brand” as a writer, and I didn’t know how to present myself. I was talking to my thesis advisor Warren Liu about this, and he told me: just focus on the writing. It helped me significantly.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I wake up around 8 and I have a coffee and a banana I write until 11 or 12 every day. I nanny so I work in the afternoons.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

It took me awhile to get to the place where I genuinely believed that me writing is ethical, but I do, in that I think I can help people through navigating certain topics, and creating new language surrounding them, and new ways of interpreting time. So I think about my ethical duty! And I think about the books that have helped me. I don’t really get stalled that often.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Fresh-cut grass.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I’m very influenced by music and by movies and by nature and by visual art.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Toni Morrison’s novels are really important to me, and so are James Baldwin’s. Maggie Nelson’s writing and Claudia Rankine’s writing showed me what was possible in terms of form, how form can challenge time. Louise Glück taught me a lot about power and syntax, and so did Matthew Dickman. There are so many other works by other writers whose lines repeat in my head and simplify my life.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to publish another book and teach in-person at the college level (if you read this and want me to teach an Introductory Workshop please know that I would absolutely love to, anytime, anywhere). I would like to read some Russian novels.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I would be a second-grade teacher.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I didn’t really have a choice. I did a couple of other things before I really committed to writing but I kept getting distracted by the language.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book I read was Ada Limón’s The Hurting Kind.

The last great film I saw was Everything Everywhere All At Once . And C’mon, C’mon , earlier this year—Mike Mills’s films have been a huge influence on me and on my books.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I’m currently working on my second poetry book, which is titled Absolute Threshold, the term for the smallest amount of matter that can be perceived by the senses. I’m also working on a novel that is going to take a long time.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

October 8, 2022

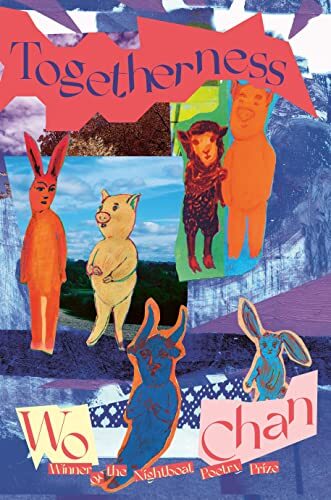

Wo Chan, Togetherness

What makes you possible? In its premiere, you watch Chopped at Gold’s Gym, bouncing on a treadmill toward a flatscreen of competitors. You are the child of a restaurant, steeped in sodium and stir-fry. Something strange now, you burn calories on a conveyor belt powered by the other burning of prehistoric flora. At night, you slip into bed and wait to wake at the banging of your door by your brother’s fist. For the next twelve hours, you stand next to your mother at the Fortune Gourmet. People eat rice. People sip cola. People drop broccoli on the carpet and flee. You were sixteen then. You still had a healthy relationship with television.

Winner of the 2020 Nightboat Poetry Prize is Brooklyn poet and drag artist (under the moniker The Illustrious Pearl) Wo Chan’s full-length debut is

Togetherness

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2022), a collage of prose poems and more traditionally-shaped poems assembled via performance and lyric gestures across first-person narration. In poems simultaneously intimate, gestural, revealing and performative, Chan writes on gender and family, of being an immigrant child of immigrants, and seeking to navigate the ongoing realities of racism and gender discrimination. “I believe that art and violence are the only things that can truly change / another person.” they write, to close the poem “@nature who’s willing,” “It unnerves me that most people cannot // —will not— // appreciate either.” Chan writes of and around drag, androgyny and the very performance of gender while offering poems on possibility, grief, survival and thriving. Chan’s poems swing and sweep, staccato and strut across the space of both page and stage, as the opening poem, “performing miss america at bushwig 2018, then chilling,” offers: “i wanted only to see soft things: your empath / friend, Our Lady of Paradise, gives guided meditations, undoing some violence // in synchrony, she sings under the megawatts of her holographic leotard: / new songs about her gender dysphoria. / my smile pancakes beyond the edges of my cuisinart / face ‘she’s so greeeaaaat’ i say stretching like an accordion. // but, how useful are words now?” In many ways, Togetherness is a book-length stage show, offering how truth and vulnerability can sometimes only be achieved through a combination of craft, skill and artifice, and an honesty as necessary as it is refreshing. As they write as part of the poem “what do i make of my face / except”: “when i was nine / i watched aladdin and thought, after money / i wish for whiteness [.]”

Winner of the 2020 Nightboat Poetry Prize is Brooklyn poet and drag artist (under the moniker The Illustrious Pearl) Wo Chan’s full-length debut is

Togetherness

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2022), a collage of prose poems and more traditionally-shaped poems assembled via performance and lyric gestures across first-person narration. In poems simultaneously intimate, gestural, revealing and performative, Chan writes on gender and family, of being an immigrant child of immigrants, and seeking to navigate the ongoing realities of racism and gender discrimination. “I believe that art and violence are the only things that can truly change / another person.” they write, to close the poem “@nature who’s willing,” “It unnerves me that most people cannot // —will not— // appreciate either.” Chan writes of and around drag, androgyny and the very performance of gender while offering poems on possibility, grief, survival and thriving. Chan’s poems swing and sweep, staccato and strut across the space of both page and stage, as the opening poem, “performing miss america at bushwig 2018, then chilling,” offers: “i wanted only to see soft things: your empath / friend, Our Lady of Paradise, gives guided meditations, undoing some violence // in synchrony, she sings under the megawatts of her holographic leotard: / new songs about her gender dysphoria. / my smile pancakes beyond the edges of my cuisinart / face ‘she’s so greeeaaaat’ i say stretching like an accordion. // but, how useful are words now?” In many ways, Togetherness is a book-length stage show, offering how truth and vulnerability can sometimes only be achieved through a combination of craft, skill and artifice, and an honesty as necessary as it is refreshing. As they write as part of the poem “what do i make of my face / except”: “when i was nine / i watched aladdin and thought, after money / i wish for whiteness [.]” In what is essentially a performance speaking to childhood and family, the collection includes a thread of testimonials composed for American Immigration Officials on the subject of Chan’s parents, who were seemingly well known and well liked in their community of Fredericksburg, Virginia, where they owned and operated a restaurant. As the press release reveals, Togetherness writes “[…] stories of the poet’s immigrant childhood spent in their family’s Chinese restaurant, culminating in a deportation battle against the State. These narrative threads weave together monologue, soaring lyric descants, and documents, taking the positions of apostrophe, biography, and soulful plaint to stage a vibrant anddaring performating in which drag is formalism and formalism is drag—at once campy and sincere, queer, tender, and winking.” The testimonials are complimentary and quite moving, although some include a level of underlying cringe, whether as a subtle racism, or through reducing their value purely to their ability to pay taxes. Writing on and around family, Togetherness writes on the ties that do bind, and the poems hold and carry a great deal of care for their family, one that works through a kind of one-person performance around a very particular series of experiences across Chan’s childhood and adolescence. This is a vibrant, critical and loving collection, one that startles through both the strength and vulnerabilities displayed throughout Chan’s glorious, tender and occasionally wild performance. Consider, for example, the three page poem “Years Flow By Like Water,” that concludes:

I love them. I know that is not a radical statement,

but I love loving them.

I hate how we were raised, though it is done now.

I think it is over. The restaurant sold to our neighbor

who makes very bad food. Our parents:

they are in bed and resting diabetic, sewn in varicose veins.

We lived through these decisions.

The air is heavier than when we first arrived

in San Francisco airport, my mother staring down the wall of terminal

glass that shines a vision of my brothers hauling

duffels, dragging luggage and my babyish hand,

already sweaty and floating through the shift home that wills to move us,

and will remove us from each other.

October 7, 2022

Touch the Donkey supplement: new interviews with Sandals, Best, Austin, Wallace, Mody, McKinnon + Naughton,

Anticipating the release next week of the thirty-fifth of Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal], why not check out the interviews that have appeared over the past few weeks with contributors to the thirty-fourth issue: Leah Sandals, Tamara Best, Nathan Austin, Jade Wallace, Monica Mody, Barry McKinnon and Katie Naughton.

Anticipating the release next week of the thirty-fifth of Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal], why not check out the interviews that have appeared over the past few weeks with contributors to the thirty-fourth issue: Leah Sandals, Tamara Best, Nathan Austin, Jade Wallace, Monica Mody, Barry McKinnon and Katie Naughton.Interviews with contributors to the first thirty-three issues (more than two hundred interviews to date) remain online, including: Cecilia Stuart, Benjamin Niespodziany, Jérôme Melançon, Margo LaPierre, Sarah Pinder, Genevieve Kaplan, Maw Shein Win, Carrie Hunter, Lillian Nećakov, Nate Logan, Hugh Thomas, Emily Brandt, David Buuck, Jessi MacEachern, Sue Bracken, Melissa Eleftherion, Valerie Witte, Brandon Brown, Yoyo Comay, Stephen Brockwell, Jack Jung, Amanda Auerbach, IAN MARTIN, Paige Carabello, Emma Tilley, Dana Teen Lomax, Cat Tyc, Michael Turner, Sarah Alcaide-Escue, Colby Clair Stolson, Tom Prime, Bill Carty, Christina Vega-Westhoff, Robert Hogg, Simina Banu, MLA Chernoff, Geoffrey Olsen, Douglas Barbour, Hamish Ballantyne, JoAnna Novak, Allyson Paty, Lisa Fishman, Kate Feld, Isabel Sobral Campos, Jay MillAr, Lisa Samuels, Prathna Lor, George Bowering, natalie hanna, Jill Magi, Amelia Does, Orchid Tierney, katie o’brien, Lily Brown, Tessa Bolsover, émilie kneifel, Hasan Namir, Khashayar Mohammadi, Naomi Cohn, Tom Snarsky, Guy Birchard, Mark Cunningham, Lydia Unsworth, Zane Koss, Nicole Raziya Fong, Ben Robinson, Asher Ghaffar, Clara Daneri, Ava Hofmann, Robert R. Thurman, Alyse Knorr, Denise Newman, Shelly Harder, Franco Cortese, Dale Tracy, Biswamit Dwibedy, Emily Izsak, Aja Couchois Duncan, José Felipe Alvergue, Conyer Clayton, Roxanna Bennett, Julia Drescher, Michael Cavuto, Michael Sikkema, Bronwen Tate, Emilia Nielsen, Hailey Higdon, Trish Salah, Adam Strauss, Katy Lederer, Taryn Hubbard, Michael Boughn, David Dowker, Marie Larson, Lauren Haldeman, Kate Siklosi, robert majzels, Michael Robins, Rae Armantrout, Stephanie Strickland, Ken Hunt, Rob Manery, Ryan Eckes, Stephen Cain, Dani Spinosa, Samuel Ace, Howie Good, Rusty Morrison, Allison Cardon, Jon Boisvert, Laura Theobald, Suzanne Wise, Sean Braune, Dale Smith, Valerie Coulton, Phil Hall, Sarah MacDonell, Janet Kaplan, Kyle Flemmer, Julia Polyck-O’Neill, A.M. O’Malley, Catriona Strang, Anthony Etherin, Claire Lacey ,Sacha Archer, Michael e. Casteels, Harold Abramowitz, Cindy Savett, Tessy Ward, Christine Stewart, David James Miller, Jonathan Ball, Cody-Rose Clevidence, mwpm, Andrew McEwan, Brynne Rebele-Henry, Joseph Mosconi, Douglas Barbour and Sheila Murphy, Oliver Cusimano, Sue Landers, Marthe Reed, Colin Smith, Nathaniel G. Moore, David Buuck, Kate Greenstreet, Kate Hargreaves, Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Erín Moure, Sarah Swan, Buck Downs, Kemeny Babineau, Ryan Murphy, Norma Cole, Lea Graham, kevin mcpherson eckhoff, Oana Avasilichioaei, Meredith Quartermain, Amanda Earl, Luke Kennard, Shane Rhodes, Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Sarah Cook, François Turcot, Gregory Betts, Eric Schmaltz, Paul Zits, Laura Sims, Stephen Collis, Mary Kasimor, Billy Mavreas, damian lopes, Pete Smith, Sonnet L’Abbé, Katie L. Price, a rawlings, Suzanne Zelazo, Helen Hajnoczky, Kathryn MacLeod, Shannon Maguire, Sarah Mangold, Amish Trivedi, Lola Lemire Tostevin, Aaron Tucker, Kayla Czaga, Jason Christie, Jennifer Kronovet, Jordan Abel, Deborah Poe, Edward Smallfield, ryan fitzpatrick, Elizabeth Robinson, nathan dueck, Paige Taggart, Christine McNair, Stan Rogal, Jessica Smith, Nikki Sheppy, Kirsten Kaschock, Lise Downe, Lisa Jarnot, Chris Turnbull, Gary Barwin, Susan Briante, derek beaulieu, Megan Kaminski, Roland Prevost, Emily Ursuliak, j/j hastain, Catherine Wagner, Susanne Dyckman, Susan Holbrook, Julie Carr, David Peter Clark, Pearl Pirie, Eric Baus, Pattie McCarthy, Camille Martin and Gil McElroy.

The forthcoming thirty-fifth issue features new writing by: Garrett Caples, Sheila Murphy, Stuart Ross and Brenda Coultas, and a collaboration between Chris Turnbull and Elee Kraljii Gardiner.

And of course, copies of the first thirty-four issues are still very much available. Why not subscribe? Included, as well, as part of the above/ground press subscriptions! We even have our own Facebook group. It’s remarkably easy.

October 6, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Alisha Kaplan

Alisha Kaplan is a Canadian poet and narrative medicine practitioner. She has an MFA in Poetry from New York University and is currently pursuing a Master’s in Narrative Medicine at Columbia University. Kaplan is on the Narrative-Based Medicine Team at the University of Toronto and is a workshop facilitator with the Writers Collective of Canada. Her writing has appeared in Fence, DIAGRAM, PRISM International, Carousel, The New Quarterly, and elsewhere. Honours she has received include the Hippocrates Prize in Poetry and Medicine, a Rona Jaffe Fellowship, and winning the Eden Mills Writers Festival Literary Contest. Her debut collection of poems,

Qorbanot: Offerings

, a collaboration with artist Tobi Kahn, is the winner of the Gerald Lampert Memorial Prize from the League of Canadian Poets. Kaplan splits her time between Toronto, New York, and Bela Farm where she grows garlic, harvests honey and wild plant medicine, and hosts barn dances.

Alisha Kaplan is a Canadian poet and narrative medicine practitioner. She has an MFA in Poetry from New York University and is currently pursuing a Master’s in Narrative Medicine at Columbia University. Kaplan is on the Narrative-Based Medicine Team at the University of Toronto and is a workshop facilitator with the Writers Collective of Canada. Her writing has appeared in Fence, DIAGRAM, PRISM International, Carousel, The New Quarterly, and elsewhere. Honours she has received include the Hippocrates Prize in Poetry and Medicine, a Rona Jaffe Fellowship, and winning the Eden Mills Writers Festival Literary Contest. Her debut collection of poems,

Qorbanot: Offerings

, a collaboration with artist Tobi Kahn, is the winner of the Gerald Lampert Memorial Prize from the League of Canadian Poets. Kaplan splits her time between Toronto, New York, and Bela Farm where she grows garlic, harvests honey and wild plant medicine, and hosts barn dances. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I may need a few more years to properly answer that question. From my current position in time, I can see that writing my book helped me to process much of the guilt, shame, and anger I had held onto from my religious upbringing and generational trauma from the Holocaust. It was a real journey that took me to a place where I realized I could create my own rituals and write my own prayers (which poems can be, and often are).

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I wrote a lot of (terrible) poetry as a kid and angsty teen. In undergrad, when I began to consider a writing career, I actually wrote more prose poetry and short stories than poetry. But from the beginning, I was a poet first.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It’s a snail-paced process. Draft after draft after draft. Sometimes a writing project takes shape in my mind before it touches down on paper. Sometimes the paper gives it shape. Then I need to live with the lines, turn them over on my tongue, leave them be and return to them.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I like having projects. Though, I might have a notion of what a project is going to be, and it ends up roving in an unexpected direction or revealing itself as something else. My writing process is a bit unusual; I can best describe it as “foraging.” I like to gather from different sources—sometimes my own, sometimes others’—and collage it all into a poem or longer work. I rarely have a poem in my mind that I then linearly write. I move around the lines or the pieces like a puzzle.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Despite being shy, I do enjoy doing readings—if I’m in the right emotional state. For instance, when my book came out, I was feeling very vulnerable about it and found myself wanting to retreat into the darkest corner rather than get up on a stage. Now, a year later, I feel the pull to share my work face to face, in real time and space. I also love collaborating with musicians, dancers, and artists in performance.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Prevailing concerns I have are: What do we hear in the silence? And how do the words live off the page?

Some of the questions I worked to answer in Qorbanot were: What does it mean to “offer”? How do I translate the ancient practice of sacrificial offering into my life in the 21st century? How can a poem be an offering, or a book an altar upon which I place what I have to give? What does it mean to write one’s own sacred texts? What is it about giving up something that makes it a meaningful act of worship? Why the obsession with purity laws in Judaism, and how has this affected the way we relate to animal bodies and our own bodies? How do we reconcile these ancient, fleshly, violent rituals with Judaism and, more broadly, Western religion today? Do humans have an inherent tendency toward violence? Can we find parallels to sacrifice in recent history, such as war, politics or environmental issues?

The main question currently occupying my writer’s mind is: How can we find more language around suicide to better express its nuances, complexities, and diverse motivations? I’ve also been contemplating the relationship between depression and anger. And I’ve been grappling with how to share my story in a way that serves as a resource for others and, at the same time, protects my own vulnerability.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I don’t think the writer has one role. There are so many different kinds of writers with different roles they can take on. A writer can serve as a lighthouse illuminating the moment in which we are living. The writer can be a dreamer, a prophet. The writer can be a court jester. The writer can offer medicine. And some writers have a role for themselves alone, to which the rest of the world is not privy.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential. A good editor can see what I can’t, from over there.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I try to keep in mind this line from the poem “How to Be Perfect” by Ron Padgett: “Hope for everything. Expect nothing.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to short stories)? What do you see as the appeal?

These days I’m moving more between poetry and non-fiction, and I find that the writing takes on the form that it needs to be in.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

These days there is no typical day. When I am in more of a routine, which I like to be, I usually begin with a workout or yoga and meditation. Then, before I turn on my phone, look at my email, and let the demands of the day flood in, I sit with a cup of tea in my favourite cafe and write until my brain hurts.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I find that conversations or workshops with friends and fellow poets best helps to unstick my writing. And movement—going for a walk does wonders, especially somewhere full of trees and plants. Or total stillness—I like lying on the floor. It grounds all that cerebral work and offers a new perspective. A solution tends to arrive in one of those situations.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Depends on the season. Depends on the home. At the moment, it’s beeswax.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Most definitely nature, which includes all of the above. I get a lot of inspiration from weeds, bees, trees, and soil. I spend as much time as I can on my farm, Bela Farm, which is now bursting with colour, song, scents, and creativity. The other day I was picking tiny wild strawberries that grow all over the farm, and fragments of a poem grew in my head as I crawled on my knees through the grass, searching for berries.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Today, they include: Anne Carson. Rosemary Tonks. Louise Glück. Sylvia Plath. Kavanaghand Heaney. Ada Limón. Basho and Buson. Sappho. Blake. H.D. The list is, of course, much longer. And the truth is, probably more than those giants, the writers who are most important for my work and my life are my poet friends, who constantly inspire.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d like to write a book-length poem. I want to create a support system for women with mysterious chronic illnesses and to build the field of Environmental Narrative Medicine. I want to be a mother. And I’d like to be the bassist in a moderately famous rock band.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

If I hadn’t become a writer, I might have ended up being a psychiatrist or a midwife. Or a farmer.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It was what I was drawn to, again and again.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The best book I have read this year—maybe in years—is When We Cease to Understand the World by Chilean writer Benjamín Labatut.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a lyric essay about suicide—a search for better language for suicide. It’s a hybrid of prose, poetry, and image that intertwines Kurt Cobain’s story with mine.

October 5, 2022

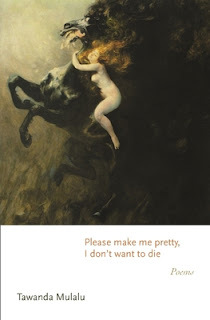

Tawanda Mulalu, Please make me pretty, I don’t want to die: Poems

AFTER HISTORY

Has anyone managed to make a world.

after race we turn to genetics, return

after to the archives for new history. Who

then determines when we’re from. Roots,

we learn to speak of them. The baobabs do

not speak of themselves. We hear wind flee

through their leaves. We see our minds feast

through bark as ants warring with termites.

Has anyone managed to make themselves.

We wonder our excitement when we see

only our wide teeth speak, only our large lips,

anything so small as proof that we could not

hold one another. We do maybe. We did not.

I was startled by the poems in New York City-based poet Tawanda Mulalu’s full-length debut, his Please make me pretty, I don’t want to die: Poems (Princeton University Press, 2022). There is such a smart and vibrant energy and confidence to this collection, composed through a thick, complicated series of wisdoms, descriptions and lyric offerings. “So,” he writes, as part of the poem “STILL LIFE,” “I’m part of this thing where fish learned to walk. / Your first baby pictures look like seahorses. / We stop now to consider our lungs. / Look at all that we have made / and behold it is very good.” Referencing his debut, then still in-progress, as part of a short write-up on the Tin Housewebsite, he offers that:

The poems within it seem (to me) to be about the failure of intimacy and frequently ask what it means to be (or not be) seen by others and by oneself. They are written from, for and against: America, blackness, Sylvia Plath, prettiness, song, poetry, and mind.

In many ways, Mulalu offers his collection as one structured two-fold: an engagement with form, and an articulation and examination of placement and positioning, each thread an essential way through which an engagement with the other is achieved. Mulalu writes through the form of the elegy and the sonnet, for example, offering a lyric as much music as it might be a kind of dream; as much sadness and grief as he includes a kind of dreamy optimism. Across a wide scope of attention, Mulalu writes of the difficulty of families, traditional poetic forms and ecological concerns; he writes of racism and America; he writes of difference and division, citing aggressions and encounters that exhaust, but offered in a way that enlightens as much as documents. As he writes to close the poem “SECOND SONNET”: “There is too much potential in this dying / planet not to believe you are at the end of this. yes even I / hear you long enough to hear another person: and think she / was as clever as you said you were at the start of this: who / is not the point. I meant this Earth.” One can’t help but admire the seemingly straight lines, lyric ease and accumulations of Mulalu’s poems, composing lines that bend in the light, or perhaps even with gravity, given their incredible density and strength. These are highly structured poems that read with such a lightness of line that one might get lost. There’s so much happening in these poems, so much spoken and hinted, such as the poem “MY SISTER LIKES GIRLS AND DOES NOT / RETURN FOR MY MOTHER’S FIFTIETH,” a poem that begins: “Months after I hadn’t had my first oyster / before I came to America. My sister in Canada now // where it starts snowing soon. Things I haven’t seen / keep cropping up. Movies are colonialism // and I’m such a dutiful director, swerving cameras / around oceans I hadn’t had before.” Mulalu’s poems point to song, but a song that carries the enormous weight and heft of love and loss and being, articulating clever turns of narrative and turns of phrase, showcasing some of the best the lyric form might offer across a canvas as wide as it is precise. “My open window / a synecdoche of country.” he writes, as part of the poem “MISCEGENATION ELEGY,” “No matter how much smoke a pig / roasts won’t erupt into song.”

In many ways, Mulalu offers his collection as one structured two-fold: an engagement with form, and an articulation and examination of placement and positioning, each thread an essential way through which an engagement with the other is achieved. Mulalu writes through the form of the elegy and the sonnet, for example, offering a lyric as much music as it might be a kind of dream; as much sadness and grief as he includes a kind of dreamy optimism. Across a wide scope of attention, Mulalu writes of the difficulty of families, traditional poetic forms and ecological concerns; he writes of racism and America; he writes of difference and division, citing aggressions and encounters that exhaust, but offered in a way that enlightens as much as documents. As he writes to close the poem “SECOND SONNET”: “There is too much potential in this dying / planet not to believe you are at the end of this. yes even I / hear you long enough to hear another person: and think she / was as clever as you said you were at the start of this: who / is not the point. I meant this Earth.” One can’t help but admire the seemingly straight lines, lyric ease and accumulations of Mulalu’s poems, composing lines that bend in the light, or perhaps even with gravity, given their incredible density and strength. These are highly structured poems that read with such a lightness of line that one might get lost. There’s so much happening in these poems, so much spoken and hinted, such as the poem “MY SISTER LIKES GIRLS AND DOES NOT / RETURN FOR MY MOTHER’S FIFTIETH,” a poem that begins: “Months after I hadn’t had my first oyster / before I came to America. My sister in Canada now // where it starts snowing soon. Things I haven’t seen / keep cropping up. Movies are colonialism // and I’m such a dutiful director, swerving cameras / around oceans I hadn’t had before.” Mulalu’s poems point to song, but a song that carries the enormous weight and heft of love and loss and being, articulating clever turns of narrative and turns of phrase, showcasing some of the best the lyric form might offer across a canvas as wide as it is precise. “My open window / a synecdoche of country.” he writes, as part of the poem “MISCEGENATION ELEGY,” “No matter how much smoke a pig / roasts won’t erupt into song.”