Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 110

October 24, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ivan Drury

Ivan Drury

published his first book of poetry,

Un

, with Talon Books in the spring of 2022. He has lived his whole life on the unceded territories of Coast Salish and Sto:lo nations; currently, on Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil Waututh lands in East Vancouver, where he teaches history and labour studies at an international college associated with SFU and drives a public transit bus. Ivan is a long time revolutionary socialist organizer, writer, and publisher.

Ivan Drury

published his first book of poetry,

Un

, with Talon Books in the spring of 2022. He has lived his whole life on the unceded territories of Coast Salish and Sto:lo nations; currently, on Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil Waututh lands in East Vancouver, where he teaches history and labour studies at an international college associated with SFU and drives a public transit bus. Ivan is a long time revolutionary socialist organizer, writer, and publisher. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Over the course of more than a decade, this book has been part of my effort to change my life to be consistent with my commitment to remaking a world without capitalism and colonialism. I wrote the first draft of Un during a time of radical personal transformation, just after I resigned from a socialist group with a toxic internal culture. After that initial draft I focused on political activism, often to the detriment of writing. Now, more than 10 years later, Talon’s publishing of Un gave me an opportunity to re-engage the manuscript. For me, from the beginning of writing Un to its publication feels like the bookends of an important period of my life through which I have arrived at a more mature appreciation for the thinking-action of writing poetry.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I find myself uncomfortable with bracketing fiction – and maybe even non-fiction – as distinct from poetry. In high school I wrote and directed two plays. My Master’s degree is in history. For more than 20 years I have been writing and editing community, socialist journalism. A book of non-fiction political essays that I edited, and wrote, is coming out with ARP Books in the spring. For me, poetry is one part of an overall approach to writing and thinking, that which is concerned with problems of political theory that I can’t think through properly in essay form: the ambivalent, and the feeling of subject formation – aspects of social and historical life that are too in-motion to write about as decisively as an essay demands.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I write single poems and poem fragments frequently, as notes. Then, when I come across an idea for a long poem I use those fragments as drafts – I find that I've been developing the long poem in pieces without knowing it, and then it comes together. When I wrote Un, the first draft came out in a burst, all at once, and then I added in fragments through the editing process that took a long time.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Once I start working on a book, or long poem, I have that project clearly in mind, and other writing and thinking is steered towards it. I'm still a young writer, though not a young person, but at this point I have not ever published the short pieces or fragments I write along the way.

5 – Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy doing readings, though I am still quite nervous about them. I have not done a lot of readings at this point, but those I have done since the publication of Unhave changed my reading of the book. I have really enjoyed creating visual landscapes made up of photographs, photo art I made, and videos to pair with the readings. And while I always thought of the book as one long poem, planning readings has helped me think through the fragments and threads that run through that long poem. I look forward to doing readings as part of a process of testing and more completely understanding the poems I’m working on for my next project.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

At this point, the general question that motivates all my poetic writing is about the social construction of hegemonic and subaltern subjectivities through the global processes of capitalist production – to put it maybe too abstractly. What I mean is that I’m interested in the feelings people have about who they are in the world, and the dialectical connection between those feelings and how people act and what they believe. I am also concerned with this problem, the relationship between the subjective and the objective, in my political journalism and theory writing, but I find essays inadequate to dealing with problems of feeling. I think understanding the historical forces of feelings are important to an emancipatory political project because, as Italian communist Antonio Gramsci argues, at a certain intensity, feelings take on the density of material forces and act upon the world like other aspects of capitalist production.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Well – I think the “larger culture” needs to be understood as totally submerged in the depths of the ocean of global capitalist production. My view is that capitalism makes use of all intellectual production within its compass to reform, adapt, and perfect its socially reproductive spheres and processes – including and even especially critical intellectual and creative work. The more a writer plays an active role in that larger culture, the more they play a passive role in the rearticulation of bourgeois power.

In the past in the west, and today in other parts of the world, where capitalist civil society is not so totalizing, it was possible for writers to exercise commitment to counter hegemonic power. But this depends on the existence of counter hegemonies where writers can root themselves. I think writers and other creative producers can contribute a lot to the thinking, understanding, and development of those counter hegemonies. In the context of writing within a rapacious and always expanding imperialist culture, which is currently reaching to include, and thereby neutralize, the insurgent cultures and politics of Black and Indigenous peoples, a writer must be carefully attentive to the question of to which power they are contributing. For a working class white man writer like me, this is a thorny problem; the class character of the theatre I’m working in is not always clear. I want my work to contribute to the building of counter hegemonic power, developing the self-consciousness and critical capacities of subaltern groups, against white supremacist, patriarchal capitalism.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

In preparing the final manuscript of Un with Talon Books, I had the good fortune to work with Catriona Strang. I found working with her really helpful and generative. I don't think I'd be comfortable publishing anything without first collaborating with an outside editor!

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

About writing itself, rather than the time-discipline surrounding the task of writing, I often think of the advice from Billy Crystal in Planes Trains and Automobiles: "writers write." It's a soundbite from pop culture that replays in my head. I like thinking of writing as a verb rather than an identity.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to journalism)? What do you see as the appeal?

When I work in journalism for too long, two things happen. First, I start to use too much heavy metaphor in my journalism and it becomes too pretentious! And second, I find I start to get too mechanical in my thinking. Poetry, for me, is a method of thinking that is necessary to a more complete social investigation and understanding. I don't always find it easy to switch between them because they require a different pace, poetry takes a lower gear in the transmission of my brain, but that shift is necessary.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

These days I'm working two jobs and struggling to maintain a political practice of study and essay writing, as well as writing poetry. So I don't have a typical day. My ideal day would be to wake up, exercise, read for one hour, and then write for 2 hours – two days of writing essays and then one of writing poetry. But now I'm scheduling in writing blocks where I have time, after work before making dinner, and on days off.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

When I feel unable to write, I read and study. My best thinking is sparked by others and I find writing notes as I read theory and poetry to be the most inspiring space.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

It's been three months without rain in Vancouver, and this morning it rained for the first time. I realized that the most "home" smell for me is the scent of the wet cement after it has been dry.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I love art generally. I played in punk bands for years when I was young. I grew up in the theatre and I have developed a real appreciation for film by going to, and recently starting to volunteer at The Cinematheque, an art house movie theatre in Vancouver. I also try to go to art galleries, though I feel like a real rookie with visual art. I find all art forms inspiring and challenging to my thinking about writing; I take a lot of notes and think actively through all art I can access.

And I think I am personally only at home in nature. For the last 6 years I lived in a cabin I built on a friend's property in Deroche, outside Mission. He sold the property this year so I lost the cabin, and thought I could just spend more time climbing mountains – which I also love doing. But I found I just can't live without it, so I'm now building a new cabin on another friend's property on the east side of Stave Lake.

I'd say these are my two critical inspirations. My writing is full of references to the arts and the land.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

The most important writers for me are communist thinkers: Marx, Gramsci, and Lenin. I read and return to their work all the time.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

In terms of writing, I'd like to write and stage a multi-voice performance of a long poem. I did direct and produce two plays when I was in high school, but not since and not in the world outside a high school theatre program!

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

In terms of the arts, I wish I could have made films. But it feels out of reach to me, in terms of time, money, and resources, and I think I'm too old to start now.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I have wanted to "be a writer" for as long as I can remember. When I was in my teens and twenties I thought I'd dedicate myself to writing once I had finished with the pressing work of travelling, playing music, and then, for the longest time, political activism. Eventually I realized that I was writing, and therefore a writer, all along.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

"Great" is an intimidating term! But the last book I read that I found challenging and inspiring was Axel Honneth, Recognition: A Chapter in the History of European Ideas. The most recent book of fiction I read that I really enjoyed was Noor Naga, If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English.

The most recent film I saw that I thought was great was, Sambizanga, made in 1972 by Sarah Maldoror, a film about women in the Angolan revolution. I took my labour studies class to see it at The Cinematheque last week and thought it was an incredible document of struggle, and an inspiring community production.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I just submitted grant applications for the first time, for a new long poem provisionally titled: "Displacing Soviet Vancouver." I'm planning to compose a book of poetry based on archival research and interviews with my family members about the pan-Slavic diasporic community that was displaced by Vancouver's slum clearance program in the 1960s. I'm excited to work on a poem that is focused on the adjustment of subjectivities outside of but connected to my own, and through a deep historical study.

October 23, 2022

periodicities : a journal of poetry and poetics

Recently on periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics: new poetry by Joseph Kidney, Lannii Layke, russell carisse, Margo LaPierre, Kristjana Gunnars, Gary Barwin, Ori Fienberg, Heather Cadsby, Shelly Harder, Phil Hall, Ben Jahn, Beth Follett, Pearl Pirie, Rob Winger, Ronna Bloom and Gil McElroy; reviews of work by Stuart Ross (by Jay Miller), Joanna Lilley (by Kim Fahner), Charles Leblanc (by Jérôme Melançon), Steph Yates (by Adam Mohamed), Yvonne Blomer (by Kim Fahner), Chris Banks (by Russell Carisse), Kate Hargreaves (by rob mclennan), Rose Després (by Jérôme Melançon), Conyer Clayton (by rob mclennan), Stephen Brockwell (by rob mclennan), Lise Gaboury-Diallo (by Jérôme Melançon), Tanis MacDonald (by Kim Fahner); interviews with Yvonne Blomer (by Kim Fahner), Sarah Mangold (by Joanna Piechura) and a roundtable interview with Stephen Morrissey, Endre Farkas, and Ken Norris about the Vehicule days and beyond (by Carolyn Marie Souaid); translations of work by Charles Leblanc (by Jérôme Melançon), Rose Després (by Jérôme Melançon), Lise Gaboury-Diallo (by Jérôme Melançon) and Emile Verhaeren (by Jacob Siefring); essays by Michael Boughn, Geoffrey Nilson, Mirjana Villeneuve (on Sylvia Plath), Stan Rogal (on David Donnell's Watermelon Kindness), Patrick James Dunagan (on Gregory Corso), Peg Cherrin-Myers (on Ronna Bloom), Ken Norris (on Michael Ondaatje's Rat Jelly), Colin Morton (on George Bowering's Kerrisdale Elegies), Gil McElroy (on Ken Stange), Jed Munson, Terri Witek (on WH Auden), M.L. Martin (on Joseph Ceravolo), Martin Corless-Smith (on Free Poetry), Frances Klein (on Matthew Dickman), Michael Schuffler (on Kid Stigmata), Grant Wilkins, Andrew Burke (on Phil Hall), Chris Banks on Dean Young (1955-2022) and Mark Tardi Craig Watson (1950–2022); Notes on the Field by Ellen Chang-Richardson (on Ottawa) and Annick MacAskill (on Kjipuktuk/Halifax); Residency Report by Marie Marchand; Amanda Earl's Visual Poetry Through the Lens of the Long Poem: A Conversation : folio; virtual reading series #30, with new videos by Michael Fraser, Alexandra Oliver, Alice Burdick, Adrian Lürssen + Leigh Chadwick; and "Process Notes," curated by Maw Shein Win, by Katie Peterson and Young Suh, and Lisa Rosenberg (with more forthcoming, including Rae Diamond, rob mclennan and MK Chavez)

Recently on periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics: new poetry by Joseph Kidney, Lannii Layke, russell carisse, Margo LaPierre, Kristjana Gunnars, Gary Barwin, Ori Fienberg, Heather Cadsby, Shelly Harder, Phil Hall, Ben Jahn, Beth Follett, Pearl Pirie, Rob Winger, Ronna Bloom and Gil McElroy; reviews of work by Stuart Ross (by Jay Miller), Joanna Lilley (by Kim Fahner), Charles Leblanc (by Jérôme Melançon), Steph Yates (by Adam Mohamed), Yvonne Blomer (by Kim Fahner), Chris Banks (by Russell Carisse), Kate Hargreaves (by rob mclennan), Rose Després (by Jérôme Melançon), Conyer Clayton (by rob mclennan), Stephen Brockwell (by rob mclennan), Lise Gaboury-Diallo (by Jérôme Melançon), Tanis MacDonald (by Kim Fahner); interviews with Yvonne Blomer (by Kim Fahner), Sarah Mangold (by Joanna Piechura) and a roundtable interview with Stephen Morrissey, Endre Farkas, and Ken Norris about the Vehicule days and beyond (by Carolyn Marie Souaid); translations of work by Charles Leblanc (by Jérôme Melançon), Rose Després (by Jérôme Melançon), Lise Gaboury-Diallo (by Jérôme Melançon) and Emile Verhaeren (by Jacob Siefring); essays by Michael Boughn, Geoffrey Nilson, Mirjana Villeneuve (on Sylvia Plath), Stan Rogal (on David Donnell's Watermelon Kindness), Patrick James Dunagan (on Gregory Corso), Peg Cherrin-Myers (on Ronna Bloom), Ken Norris (on Michael Ondaatje's Rat Jelly), Colin Morton (on George Bowering's Kerrisdale Elegies), Gil McElroy (on Ken Stange), Jed Munson, Terri Witek (on WH Auden), M.L. Martin (on Joseph Ceravolo), Martin Corless-Smith (on Free Poetry), Frances Klein (on Matthew Dickman), Michael Schuffler (on Kid Stigmata), Grant Wilkins, Andrew Burke (on Phil Hall), Chris Banks on Dean Young (1955-2022) and Mark Tardi Craig Watson (1950–2022); Notes on the Field by Ellen Chang-Richardson (on Ottawa) and Annick MacAskill (on Kjipuktuk/Halifax); Residency Report by Marie Marchand; Amanda Earl's Visual Poetry Through the Lens of the Long Poem: A Conversation : folio; virtual reading series #30, with new videos by Michael Fraser, Alexandra Oliver, Alice Burdick, Adrian Lürssen + Leigh Chadwick; and "Process Notes," curated by Maw Shein Win, by Katie Peterson and Young Suh, and Lisa Rosenberg (with more forthcoming, including Rae Diamond, rob mclennan and MK Chavez)as well as pieces reprinted from various of the Report from the Society festschrift series, including pieces critical and creative, responding to works by Stephen Brockwell, Amanda Earl, Stuart Ross, Kate Siklosi, Elizabeth Robinson, Monty Reid, Cameron Anstee, Phil Hall, Gregory Betts and Sarah Mangold (with further volumes forthcoming!

with forthcoming work by Paul Perry, Lori Anderson Moseman, Kirstin Allio, Divya Victor, Christopher Patton, Jay Stefanik, Leigh Chadwick, Chris Johnson, Yvonne Blomer and plenty of others! What!

and a reminder: periodicities is open to submissions of previously unpublished poetry-related reviews, interviews and essays. We are also seeking pieces (essays/interviews etc) on the Canadian long poem!

Please send submissions as .doc with author biography to periodicityjournal (at) gmail.com

For the time being, submissions of previously unpublished poetry will be by solicitation-only, with the exception of translated works (which you should very much send along).

ALSO: periodicities is seeking essays in its #FirstRealPoets series, a series originally prompted by this piece by Canadian poet Zane Koss on Stuart Ross. Who was the first real poet you ever encountered in the flesh? How did that encounter shape your approach to poetry? How does that poet make poetry a possibility for people who might not otherwise see themselves as poets? We hope to read essays about real poets' poets. The poets who might not get the critical recognition they deserve but are nonetheless important community-creating figures who welcome and encourage new voices.

ALSO: periodicities is seeking short essays on a particular older book by another poet, a series originally prompted by Ken Norris, who wrote this piece on Michael Ondaatje's Rat Jelly.

periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics,

founded March 2020

edited and lovingly maintained by rob mclennan

built as a curious extension of above/ground press (b. July 9, 1993

October 22, 2022

Chia-Lun Chang, Prescribee

I need to gain the most profound words

to prove to the speakers:

I’m valuable &

look good in the morning. (“ENGLI-SHHH ISN’T YOURS”)

Born and raised in New Taipei City, Taiwan, New York City-based Chia-Lun Chang’sfull-length poetry debut, and winner of the Nightboat Poetry Prize, is

Prescribee

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2022). Following the chapbooks

One Day We Become Whites

(No, Dear, 2016) and

An Alien Well-Tamed

(Belladonna*, 2022) [see her poem in the “Tuesday poem,” as well, here], Prescribeeexists as an assemblage of lyric fairy tales or fictions, narratives of truths and truisms, offering reportage from an America discovered, yet still at a distance. “I came to the United States for love. When men asked about / my past,” she writes, as part of the poem “PARENTS,” “I replied, Father said we must not talk about // feelings. I practice a man coming to me by holding my breath / under the water. We’re repressed and they’re satisfied.”

Born and raised in New Taipei City, Taiwan, New York City-based Chia-Lun Chang’sfull-length poetry debut, and winner of the Nightboat Poetry Prize, is

Prescribee

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2022). Following the chapbooks

One Day We Become Whites

(No, Dear, 2016) and

An Alien Well-Tamed

(Belladonna*, 2022) [see her poem in the “Tuesday poem,” as well, here], Prescribeeexists as an assemblage of lyric fairy tales or fictions, narratives of truths and truisms, offering reportage from an America discovered, yet still at a distance. “I came to the United States for love. When men asked about / my past,” she writes, as part of the poem “PARENTS,” “I replied, Father said we must not talk about // feelings. I practice a man coming to me by holding my breath / under the water. We’re repressed and they’re satisfied.” Composed as a love song of the immediate, Chang [see the 2016 Belladonna* small press interview I conducted that she was part of] writes of the outsider, one that seeks both entry and distance; writing of memory and history, arriving and departing, and the lonely, lyric architecture of in-betweenness. “After reviewing your personal history / bilingually,” she writes, to open the poem “THE FORM OF POMELO,” “the receptionist of the clinic praised / you on your first language. / In a distant land, what you were / born with became a talent.” She writes of the immigrant; of masculinity, and the false ethics of capitalism. “dip a spoon of honey after ordering a hive online,” she writes, as part of the poem “SIMPATICO,” “feeding bees / in spring, anesthetizing their tongues and poisoning them to / death in the winter // drink a cup of coffee every morning after the bean picker / collects 120 pounds in the rainforest, paces on slippery bare / feet and stumbles home in the heat [.]” In many ways, this is a book of frustration, composed of sharp, observant lyrics offering biting commentary on language, exhaustion, cultural distances, departures and arrivals, attempting connections and the mutability of memory, and responding to a sequence of racist microaggressions. In many ways, the poems that make up Chang’s Prescribee articulate and repeat the same simple rhetorical offering: what is so difficult about wanting everyone to be nicer to each other?

She writes of the past, but refuses nostalgia, offering instead parcels of meaning she might be able to carry through to the present; she writes of consumerism, and how certain advancements only seem to emerge through the slow destruction and devastation of something else. “We have to sing continually so our bodies can generate ecstasy.” she writes, as part of the poem “BEING POOR.” “So sweet it tastes like sugar and a bit like tomorrow.” Chang writes, one might say, to actively resist, whether false memory, labelling or even the false perception of others upon her. These poems are about her resistance; in truth, they document and display simultaneously. “Foreign bodies / Are dangerous.” she writes, to close the poem “UPON DISRESPECTFUL ADVICE,” “Still, I exist without consent.”

October 21, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Tasnuva Hayden

Tasnuva Hayden

is a writer based in Calgary, Alberta, where she works as a consulting engineer and editor for

filling Station

, Canada’s experimental literary magazine. Her work has appeared in Nōd, J’aipur Journal, Anti-Lang, carte blanche, Qwerty, and more. She is also the author of

An Orchid Astronomy

, a book of experimental poetry cataloguing a migrating requiem of memories, mythologies, and science in the face of climate catastrophe and personal collapse, from the University of Calgary Press, July 2022.

Tasnuva Hayden

is a writer based in Calgary, Alberta, where she works as a consulting engineer and editor for

filling Station

, Canada’s experimental literary magazine. Her work has appeared in Nōd, J’aipur Journal, Anti-Lang, carte blanche, Qwerty, and more. She is also the author of

An Orchid Astronomy

, a book of experimental poetry cataloguing a migrating requiem of memories, mythologies, and science in the face of climate catastrophe and personal collapse, from the University of Calgary Press, July 2022. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

An Orchid Astronomy is my first book. Having it published has helped me feel more confident in my potential as a writer. I’ve learned a lot about completing a manuscript and taking it to its full conclusion. My previous works consist primarily of short stories and poetry published in magazines and journals. I have also published scientific papers. Publishing my first book has demystified the work of being a writer. It feels different only in that the veil has been lifted—like any job it can be gruelling and tedious.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

The first thing I ever truly wrote was a sixteen page short story for a school assignment in the third grade. The assignment was to write a påskekrim, which translates to “Easter crime” in Norwegian. The genre encompasses the noir, thriller, crime, and mystery stories that Norwegians enjoy reading during Easter break. I came to poetry in high school, especially after reading The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy. That being said, poetry was the first piece of writing I ever published.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Unfortunately, I have to be quite structured with my writing projects because I also work as a consulting engineer. For this reason, I find that I am only able to focus on one project at a time. In this regard, my process is on the slower side, but that is because I tend to work on book-length projects. My work comes out of stages: planning, research, note taking, content generation, editing, re-writing, proofing, and submissions. I allow myself to think of all these as the tasks of a writer. Thankfully, the stages overlap, so there is always a creative element that keeps things interesting.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I have a tendency to think of creative writing in terms of story—that I’m putting on the life of someone else. I have trouble writing smaller pieces for this reason because, like the reader, I too am writing to find out the ending. My preferred form is probably the novel, which means I am working on a book-length manuscript from the very beginning. My short stories tend to be scenes taken from a larger imagined universe/project. They almost always lead to full-length book ideas.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Being an introvert, I haven’t performed at many public readings to date. I hope to change this as I further my writing career. I want to be someone that enjoys readings and someone who can engage with my readers in a positive way. People are usually so wonderful at these events that I always end up having a good time in the end.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I suppose every age in human history has had its own set of problems—ours is obviously the existential doom that is surely underway by now—we get to watch, in slow motion, the breakdown of the fabric of society and nature as we know it.

In my own writing and art, my main concerns revolve around revealing the emotional resonance of life. It means my focus tends to be on more universal themes and the questions that subsequently arise, such as humanity’s place in the universe, the legacy our species will leave behind, death, obsession, love, and redemption. Ultimately, I see writing as an exploration of form and genre. I am interested in exploring how one breaks the conventions of genre and form, as well as seeing how such conventions can be utilized to one’s advantage. Determining the structure of a project is what takes the longest for me.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

People write for so many reasons. I do not feel equipped to say what the role of a writer should be—not everyone is privileged enough to write for the sake of the craft. If we lived in a perfect world, then ideally the practice of writing should enlighten. At the very least, it should ignite a change or transformation, whether that takes place within the writer or the reader is irrelevant.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

This might come off as biased, being an editor myself, but I do believe editing is 9/10ths of the law, especially if you are planning on publishing. I take editorial feedback extremely seriously. It’s not about if the process is difficult or annoying—it’s just necessary.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Don’t try. Just do.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I generally write first thing in the morning. This is again due to my day job. The ideal day will start at 6AM with some yoga, followed by coffee and breakfast. Writing will begin around 7AM and go until about 9AM. My evening routine consists of either reading or watching a show/movie. Typically, my best ideas come to me during this part of the day, so I make sure to keep my tablet or notebook nearby. On occasion, I will generate content at this time, but I find the mornings are best for execution and revising.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I allow myself to take breaks after prolonged periods of writing. For example, after completing a draft or finishing an editing revision, I will allow myself a few weeks off—a holiday, essentially. On the other hand, since I only have the mental capacity to work on one project at a time, the writing process will naturally stall. However, this is on purpose; I like to extensively plan and ruminate on a project before diving into a non-stop writing schedule. Once started, I rarely get stalled. After all, the best part of creative writing is all the daydreaming I get to do. Music also helps.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

My mom’s home-cooked Bengali food—charred eggplant, roasted spices, fizzy mustard oil, and the offensively pungent smell of dried fish. My mouth waters just thinking about it.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I think all of the forms listed above influence my work. I am trained as a research engineer, so science plays a huge role in my daily life. To me, writing and visual art go hand-in-hand. I especially love Japanese manga and graphic novels. For a while, during my late teens and early twenties, I thought I might go to art school to train as an illustrator. Although I don’t play music, I do love to dance, so to me music is both an auditory and a physical mode of expression. Nature is universal—it influences everything.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

For the most part, I like to read non-fiction, specifically the diaries and letters of famous writers and artists, biographies, philosophy, metaphysics, history, and science.

When it comes to reading creative writing, I tend to gravitate towards more experimental works, whether in form, execution, or subject matter. Some of my favourites include: If On a Winter’s Night a Traveler by Italo Calvino, AVAby Carole Maso, Reader’s Block by David Markson, 2666 by Roberto Bolaño, The Necrophiliac by Gabrielle Wittkop, and, of course, The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to properly travel through the Indian subcontinent, especially Nepal and Bangladesh.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

If I could travel back in time, I would have seriously trained as a classical dancer. In particular, I would have liked to master the Bharatanatyam form.

As for what else I’d be doing, I feel it would be a job related to STEM in some way, as I already have an established professional career in this field.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Writing encompasses so many different aspects of our imagination. It is also very therapeutic. I think that is why journaling is a recommended form of self-care. It is a way to get to know yourself, to make sense of your emotions and thoughts. I am drawn to writing because it is the one form of expression that cannot be avoided—it is language. It is the fundamental way that humans communicate.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book I read was a biography on Edvard Munch called Beyond the Scream by Sue Prideaux. Not sure about the last great film, but my two favourites are Beyond the Black Rainbow and The Colour of Pomegranates.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I am working on a novel exploring Neo-Nazism among Norwegian youth in the early 1990s. During this time, Norway was undergoing a period of Black Metal hooliganism, which resulted in multiple church burnings, hate crimes, and murders.

October 20, 2022

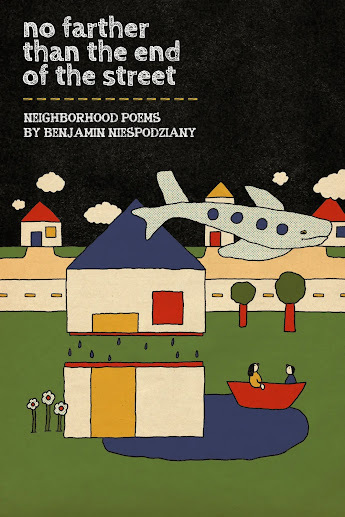

Benjamin Niespodziany, no farther than the end of the street

First Date

You bought a plot of land and you dug a hole. You filled the hole with seasoned meat and cedar and silk. You covered the hole and you waited. It was supposed to take nine months, but I arrived in seven. When I appeared I was grown and vocal. You held me like a science finalist. The floor plan was stamped to my chest.

The full-length debut by Chicago poet Benjamin Niespodziany, following chapbooks through above/ground press and Dark Hour Books, is

no farther than the end of the street

(Los Angeles CA: Okay Donkey Press, 2022), a collection predominantly constructed out of short, single-stanza prose poems that float the realm between lyric, short story and lullaby. “I wrote you a poem,” he writes, to open the poem “Publicity Stunt,” “called ‘Planet Earth.’ / It’s a ghost / poem or maybe a poem // I ghost wrote. It’s an / X-ray I pass around / the neighborhood.” Holding echoes of myth and fable, Niespodziany’s poems offer a selection of prose openings into whole worlds that might even exist between the curved narratives of Lydia Davis and the surrealisms of Stuart Ross. “You can’t / take my call.” he writes, to open the poem “The Silence That Finds Us,” “You’re busy // making volcanoes / out of swamp products // and ketchup packets.”

The full-length debut by Chicago poet Benjamin Niespodziany, following chapbooks through above/ground press and Dark Hour Books, is

no farther than the end of the street

(Los Angeles CA: Okay Donkey Press, 2022), a collection predominantly constructed out of short, single-stanza prose poems that float the realm between lyric, short story and lullaby. “I wrote you a poem,” he writes, to open the poem “Publicity Stunt,” “called ‘Planet Earth.’ / It’s a ghost / poem or maybe a poem // I ghost wrote. It’s an / X-ray I pass around / the neighborhood.” Holding echoes of myth and fable, Niespodziany’s poems offer a selection of prose openings into whole worlds that might even exist between the curved narratives of Lydia Davis and the surrealisms of Stuart Ross. “You can’t / take my call.” he writes, to open the poem “The Silence That Finds Us,” “You’re busy // making volcanoes / out of swamp products // and ketchup packets.” Organized across five numbered sections—“Yardmouth,” “Baffling Scaffolding,” “The Flimsy Chimney,” “Front Lawn Songs” and “Partial Architectures”—there is such a sense of whimsy and narrative play throughout these poems, writing magical elements of hearts lost and ghosts on the tongue, blended in and around direct statements. “With a pitcher of water,” he writes, to open the poem “In Our Backyard Garden,” “I stood next to a neighbor / who had dying flowers for a face.” He writes a lyric minimalism of layering and accumulation, one that understands both pause and pivot, narrative structures and a scaffolding deliberately playing with what to suggest, what to exclude and what to offer directly. He evokes small lyric scenes, crafting realities built out of concrete and smoke. “We could no longer afford our gardener.” he writes, to open the prose poem “The Harmless Gardener.” “I asked / him over to talk. He arrived hanging onto his / cane. I looked and his cane became a sword. I / looked again, his sword was a mailbox. The flag / was raised.”

There is such a delight to these pieces, and there are moments throughout this collection that I almost see echoes of the short stories of Richard Brautigan, offering insights into daily interactions and simply being and living in and moving through the world, tinged with a wistful surrealism simultaneously playful and dark, moving in, out and through focus, from sentence to sentence. there is such a delight, even across such dark foundations of loss, death and distance, as connections are established, demolished or never quite connect. Across eighty-four poems, Niespodziany writes of first dates, first loves, weddings, streetscapes and neighbours, suggesting a lyric set entirely within the focus of a small geography, even one centred on the domestic, with not one poem set beyond a boundary set just down Niespodziany’s imaginary or actual street. One imagines a cul-de-sac, just down from an urban setting of shops and what-have-you; a small tucked-aside corner of residencial space, not far from everything else in the world. One imagines a set of boundaries established to attempt to keep the narrator and his household safe, from whatever dangers might exist beyond.

Neighbor

You witnessed her death on our street. Your feet were in the street, but your body was in the lawn. I was inside our home, crouched like a cloud. “Now he’s a widow,” you said, pointing to the grieving husband across the street as he sleepily watched his wife being carted away. The next day, we went to the funeral in their backyard. Everyone was there, even the dead wife. She was floating over her coffin like some type of goblin we wanted to trust. An antelope leaned against their fence. After the funeral, authorities ended up taking your mug shot. Now you cough without a bonnet. Now you claw at the attic’s moon. Too soon, the body was gone and we were back to talking about lawn darts and starter homes. I was alone. You were alone. We held hands.

As part of his statement on the prose poem, included in a folio on the contemporary prose poem at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics, Niespodziany wrote: “The prose poem does not demand an ending. It does not demand an explanation. It does not need a resolution. It contains none of these things and all of these things. Anything can happen inside of such a boxed-in paragraph. A pair of wings catches fire and turns into a frog. I fell in love with the prose poem because it felt like a contained commercial break, a parable in interlude form. Enough to chew on while eating lunch, while walking around the neighborhood. A world within a wink.”

October 19, 2022

some sainte-adèle, thanksgiving;

We only managed an overnight, but we did get our regular Thanksgiving Sainte-Adèle trip in, at least, spending time at mother-in-law's cottage with her for a bit. Can you believe I haven't done a post on such since 2017? And do you remember my first post on coming up here with Christine? Geez, that was an awful long time ago. Incidentally, that was the same weekend, landing on the old homestead en route back to Ottawa, that Christine met my mother, for the first and only time.

We only managed an overnight, but we did get our regular Thanksgiving Sainte-Adèle trip in, at least, spending time at mother-in-law's cottage with her for a bit. Can you believe I haven't done a post on such since 2017? And do you remember my first post on coming up here with Christine? Geez, that was an awful long time ago. Incidentally, that was the same weekend, landing on the old homestead en route back to Ottawa, that Christine met my mother, for the first and only time.I'm not sure what our young ladies were doing in this particular photo, but I've since declared it the cover photo for their first album. Something moody, experimental. Something with attitude.

I did manage to get some good reading in, including through a 2014 collection of essays by Garrett Caples, and a variety of other publications I've already completed reviews for (whether already posted or soon-to-appear). Am I working on poems? Am I working on prose? Neither, unfortunately, caught up in reviews and what else, having lost a week to the brain-fog of post-dental surgery (implants!), and another week to the brain-fog of a head-cold. I really need to get the rest of this work out of the way so I can get back to that novel. I mean, honestly.

I did manage to get some good reading in, including through a 2014 collection of essays by Garrett Caples, and a variety of other publications I've already completed reviews for (whether already posted or soon-to-appear). Am I working on poems? Am I working on prose? Neither, unfortunately, caught up in reviews and what else, having lost a week to the brain-fog of post-dental surgery (implants!), and another week to the brain-fog of a head-cold. I really need to get the rest of this work out of the way so I can get back to that novel. I mean, honestly. What else? We spent a day or two taking a breath, in the wilds of the Laurentides. There wasn't time for much more, and our young ladies even managed a walk or two, including one with their Oma, where she took this picture.

What else? We spent a day or two taking a breath, in the wilds of the Laurentides. There wasn't time for much more, and our young ladies even managed a walk or two, including one with their Oma, where she took this picture.October 18, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ted Rees

Ted Rees

is a poet, essayist, and editor who lives and works in Philadelphia. His most recent book of poetry is

Dog Day Economy

, published by Roof Books in February 2022.

Thanksgiving: a Poem

, published by Golias Books in April 2020, was a finalist for a Lambda Literary Award. His first book of poetry, In Brazen Fontanelle Aflame, was published by Timeless, Infinite Light in 2018. Chapbooks include Dear Hole, Big Dearth in Whir, the soft abyss, and Outlaws Drift in Every Vehicle of Thought. Recent essays have been published in The Poetry Project Newsletter, Libertines in the Ante-Room of Love: Poets on Punk, Full Stop Quarterly, and ON Contemporary Practice’s monograph on New Narrative. He is editor-at-large for The Elephants, as well as founder and co-editor of Asterion Projects with Levi Bentley. Since summer of 2020, he has been running Overflowing Poetry Workshops, an extrainstitutional online workshop space.

Ted Rees

is a poet, essayist, and editor who lives and works in Philadelphia. His most recent book of poetry is

Dog Day Economy

, published by Roof Books in February 2022.

Thanksgiving: a Poem

, published by Golias Books in April 2020, was a finalist for a Lambda Literary Award. His first book of poetry, In Brazen Fontanelle Aflame, was published by Timeless, Infinite Light in 2018. Chapbooks include Dear Hole, Big Dearth in Whir, the soft abyss, and Outlaws Drift in Every Vehicle of Thought. Recent essays have been published in The Poetry Project Newsletter, Libertines in the Ante-Room of Love: Poets on Punk, Full Stop Quarterly, and ON Contemporary Practice’s monograph on New Narrative. He is editor-at-large for The Elephants, as well as founder and co-editor of Asterion Projects with Levi Bentley. Since summer of 2020, he has been running Overflowing Poetry Workshops, an extrainstitutional online workshop space.1 - How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My most recent book, Dog Day Economy, is indebted to the prior book, Thanksgiving: a Poem, in that the latter is a book-length poem written entirely in haiku, and probably marks the first time where I really wrestled with "the line," so to speak. Previously, much of my work had relied on the rhythms and sonic textures of the longer line, but the syllabic restraint of the haiku forced me to reckon with the way shorter lines can allow more ambiguity and uncanniness into a poem. Dog Day Economy takes up many of the same issues that my previous work has addressed— nihilism, personhood, autonomy, the third landscape, drugs, violence, queerness— but does so in a way that hopefully feels less didactic and more about being a person within those concerns rather than person describing those concerns. It's also important to note that the book was written over the course of about nine months, six of which were the first six of the pandemic, so that references to surveillance, exposure, and catastrophe are much more present than in previous poems, in which these themes played no small part.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Honestly, these sorts of even broader genre boundaries don't mean much to me, because everything is poetry in one way or another.

Also honestly, when I was younger, I was told that my poems were more interesting than my fiction, so I focused my attention on poetry. I've always wanted to be a fiction writer, but I'm not sure I have the patience or discipline for it.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I have no idea how to answer this question— poems come how they come, and each has its own demands and constraints that can be broken depending on mood and whim. I do usually conceive of some sort of general idea for some poems in my head, but that's more to keep me on track whilst writing them, as I glide away from that general idea all the time when I'm actually writing.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Like some of my favorite poets, I tend to arrive at a loose subject or constraint as I begin a project— that is, I will often be writing a poem and think to myself, "You could keep writing poems within these sorts of boundaries" and things go from there. That said, I began Thanksgiving with a book-length poem in mind.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

The poet Evan Kennedy described Thanksgiving as a book of "honky ventriloquism"— that is, me utilizing the cadences and gestural utterances of white people as a way of getting at the soul death at the heart of whiteness. Doing public readings for that book allowed me to really push the idea that I never want to sublimate these voices into my own, but rather have them work as spoken gestures that are meant to be read and heard as other than my own. Almost like interruptions, or bad impressions.

I love giving readings, and I love attending them, too.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

The theoretical concerns of my recent writings have much to do with the boredom of suffering, but that's not really what you asked. In one of her essays on closed and open poems, Lyn Hejinian writes about the space between lines, phrases, the leaps in logic of parataxis that marks so much Language writing. I like to think that my writing is concerned with the space of those leaps, the unsaid elements of those spaces in language that are often elided. Instability.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The larger culture is mind detergent and soul rot, so I'm mostly interested in writing that works against it.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I have loved working with every editor I've had, and also love sharing work with others who are not necessarily the publishers of my work, but the readers and supporters of my work. Eric Sneathen has been particularly helpful in this latter regard— perhaps someday we will work together in a more formal capacity!

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

"First thing you learn is that you always gotta wait."

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

I find any prose writing to be torturous, and I agonize when I'm writing essays and reviews.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write every day, though sometimes more actively working toward a goal in mind. I do have a very active reading practice which begins in the morning, when I make sure to wake up early enough to read for about 30 minutes while drinking coffee and eating breakfast. This practice is essential to my mental and emotional well-being, and I become angry when it is interrupted.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Music with lyrics is a big one for me— dumb pop music, Guided by Voices, nasty lines from obscure R'n'B songs. I also listen to a lot of instrumental music, particularly jazz, but have recently been inspired by the band Crazy Doberman, a midwestern group that plays truly out there freeform music.

In terms of writing, I am always inspired by Hejinian, Jean Day, Prynne, Lisa Robertson, Clark Coolidge, Norma Cole, and recently, James Purdy.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

My parents are also book fanatics, so their house has a sort of musty smell of books and old carpets. I like that.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I don't really think I can answer this question in any sort of sufficient way, partly because I don't think of my work as separate from any other forms.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I don't really think of an inside or outside of my work, but the writing of my friends is immensely important to my life, even if that is rarely evidenced in my work.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Impossible question!

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

If I'm being real, I'd probably be a lawyer. I hate the legal system, grounded as it is on a field of pain and death, but I've done legal research and paralegal work, and I have a knack for understanding its machinations.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I love reading more than most activities, so that's a big part of it, probably.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I recently finished Far Out West by Clark Coolidge, which I enjoyed quite a lot. I admit to having a pretty lazy and uninspired film-watching practice at present, but we've been doing horror movies since the month began, and I loved Basket Case — so much of a world that no longer exists contained in a single film, kind of incredible.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I just finished a newish manuscript on cancer and counter-narrative, so at the moment, I'm mostly prepping for a commissioned essay on the cult gay filmmaker Curt McDowell, and searching for my next poems.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

October 17, 2022

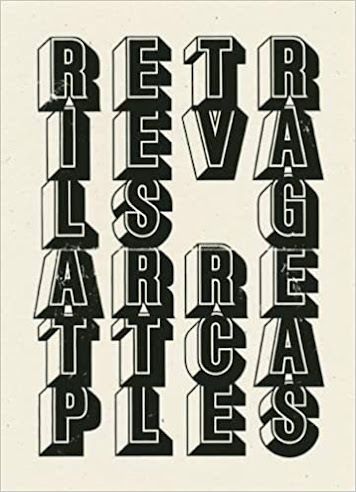

Garrett Caples, Retrievals

Poets tend to enjoy reading, so when [Kenneth] Rexroth points out a deficiency in this department, he refers not to quantity but kind. The very pleasure poets seek in the act of reading renders many of them incapable of pursuing any topic to its necessary depth, because doing so would likely compromise their enjoyment. They might have to read some pretty boring shit in order to get the information they need to take an informed position. Their own emphasis on aesthetics, poetics, the formal aspect of writing leaves them vulnerable to oversimplification and elegance where substance must prevail and prone to purely theoretical articulation where particularity and application are all that matter. For all its theoretical politics, the present Eurocentric avant-garde displays little curiosity about the actual mechanisms of American imperialism that dictate our day-to-day life in the form of the ubiquitous crap we make other peoples make for us next to nothing. Such realities are too ugly and complicated for theory, and theory’s shown itself unable to cope after 9/11. When the twin towers collapsed, a lot of elegant ideas went with them. (“Philip Lamantia and André Breton”)

Lately, I’ve been going through San Francisco poet, editor and critic Garrett Caples’collection of essays, Retrievals (Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2014) [see my review of his most recent poetry collection here], an assemblage of interrogations that circle around a central core of surrealism across the early and middle parts of the 20th century. The twenty-one essays collected here move from André Breton and Philip Lamantia into Barbara Guest, Richard O. Moore, John Hoffman, Richard Tagett, Marie Wilson, Jean Conner, Arthur Jerome Eddy, Sylvia Fein and multiple other writers, artists and critics, many of whom were well known during their individual periods of activity, but overlooked across and through the years that followed. Originally composed as individual pieces for a variety of journals, magazines and other venues, the essays gathered together offer exactly what the title suggests, attempting to retrieve or reclaim individual names of artists across decades’ of work, most of whom touched upon the central core of surrealism. As he offers to open his essay on Jean Conner, “Becoming Visible”: “When I began work on Retrievals, gathering those essays I’d written on various writers, artists, and ideas that, for one reason or another, had dropped off the cultural map or never fully made it on, I could resist the temptation to add a few more.”

Lately, I’ve been going through San Francisco poet, editor and critic Garrett Caples’collection of essays, Retrievals (Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2014) [see my review of his most recent poetry collection here], an assemblage of interrogations that circle around a central core of surrealism across the early and middle parts of the 20th century. The twenty-one essays collected here move from André Breton and Philip Lamantia into Barbara Guest, Richard O. Moore, John Hoffman, Richard Tagett, Marie Wilson, Jean Conner, Arthur Jerome Eddy, Sylvia Fein and multiple other writers, artists and critics, many of whom were well known during their individual periods of activity, but overlooked across and through the years that followed. Originally composed as individual pieces for a variety of journals, magazines and other venues, the essays gathered together offer exactly what the title suggests, attempting to retrieve or reclaim individual names of artists across decades’ of work, most of whom touched upon the central core of surrealism. As he offers to open his essay on Jean Conner, “Becoming Visible”: “When I began work on Retrievals, gathering those essays I’d written on various writers, artists, and ideas that, for one reason or another, had dropped off the cultural map or never fully made it on, I could resist the temptation to add a few more.” There is such wonderful discovery through these pieces, as Caples writes about seeing a particular artwork and working to dig up information on that particular artist, for example, working to follow a particular loose thread as far as it might go. The pieces are simultaneously critical as well as personal, allowing his wealth of inquiry and research into forms both informative and highly readable. His piece on spending time with Barbara Guest’s last work, as well as spending time with her across her final few years, is quite lovely. Other pieces touch upon his association with City Lights, having been poetry editor there for a number of years now: “As 2013 is the 60th anniversary of City Lights Books,” he writes, to open his piece “Apparitions: Of Marie Wilson at City Lights,” “I’ve been reflecting lately on its lost history. When I started working there, for example, I came across a catalogue from sometime in the early ‘60s, advertising City Lights publications to the rest of the trade, and I was immediately struck by the appearance, not just of the press’s own titles but the full list of various Bay Area small presses—Oyez, Auerhahn, and White Rabbit, if I remember correctly—which often enough were only available in the bookstore’s then-downstairs poetry section. In a way, City Lights was Small Press Distribution (SPD) avant la lettre, distributing small poetry presses not because it made money but because it was a cool thing to do.”

I’d been a few weeks attempting to find my way into the collection, but found the prologue, “Wittgenstein, A Memoir,” had such an intimidating weight, that I could only find my way in, and way through, by starting to read from the centre of the collection (his piece on Barbara Guest, actually). In certain ways, this collection reminds me of Douglas Crase’s more recent collection of essays (collected across decades of his own critical work on poets and poetry, although covering much of the same period of American poetry) [see my review of such here], in that both collections have allowed me and my own reading new spotlights on a variety of writers that may have fallen into the long shadows of others, especially across the decades since. Some interesting elements through his collection I hadn’t previously considered including Caples’ assertion that surrealism, at least André Breton’s assertion of it, was far more multicultural a movement than anything else occurring during that period across American/French art, writing and thinking, or even the fact that the CIA was deliberately and quietly promoting Abstract Expressionism over surrealism, concerned, in part, over any possibility of revolution or revolt that surrealism might prompt. What is interesting, as well, is Caples’ work around assessing and reassessing the work and life of Philip Lamantia (Caples was also the co-editor of the 2013 collection, The Collected Poems of Philip Lamantia), a poet I had little to no prior knowledge of. As the essay “Philip Lamantia and André Breton” begins:

That the standard biography of André Breton by Mark Polizzotti, which has all the appearance of being exhaustive, nonetheless excludes Philip Lamantia is a disservice not only to both poets but to the reader as well. For surely the reader would be interested to learn that, during his Second World War exile in the United States, Breton admitted but one American poet into the ranks of surrealism—let us not count Charles Duits, who wrote in French and receives ample coverage—that this poet was only 15 at the time, that he went on to become one of the major poets of a generation that includes Creeley and Duncan, O’Hara and Ashbery, and that he was still alive and living in San Francisco at the time of the bio’s original publication.

October 16, 2022

Cameron Anstee, Sheets: Typewriter Works

All books are full of errors—be they of diction, grammar, technique, fact, bibliography. The typewriter makes visible particular types of error—material errors, machine errors, operator errors. Those errors contrast the dream of precision on which typewriters were advertised; they are a return to the human error from which the typewriter was supposed to offer freedom. They also offer a visual counterpoint to the concision and (presumed) precision of minimalist works.

In the twenty-first century, a book of typewriter works is also necessarily a book of decay, and the works in this book are saturated with it. This book documents fragments of keys chipping away over time and type bars becoming warped (the uppercase ‘E’ and the lower case ‘d’ in particular caused me problems), components giving out, the scarcity of replacement parts, the loss of knowledge. I have embraced that decay, and while I strove to create clean works, I also “allowed” such imperfections to remain. They register that I typed each sheet on Bill’s typewriter. (“SOME AFTERWORDS”)

It is wonderful to see Ottawa poet, editor and publisher Cameron Anstee’s second full-length poetry title, following

Book of Annotations

(Picton ON: Invisible Publishing, 2018) [see my review of such here], his

Sheets: Typewriter Works

(Halifax NS/Toronto ON: Invisible Publishing, 2022). “This book began,” as he begins his “SOME AFTERWORDS” that end the collection, “following the death of my friend, the poet William Hawkins, on July 4, 2016, when I was gifted his Olivetti Lettera 30 typewriter.” Composed entirely, it would seem, upon the legendary late Ottawa poet and musician William Hawkins’ [see my obituary for Hawkins here] typewriter (and produced to replicate that particular typeface), Anstee’s Sheets: Typewriter Works furthers Anstee’s poetic explorations into and through the minimal, but through gestures that extend both the act and result of writing—both composition and erasure—into the deeply physical. The effect is striking and immediate, as one catches the imperfect image of the text on the page, and the occasional letter slightly askew. The process is reminiscent of how, years ago, Ottawa poet, publisher and bibliographer jwcurryspoke of curating his 1cent series of publications—each of which are poems produced through individually hand-stamping from a child’s set, one phrase or line at a time—as being curated, in part, through that measure of physicality: completely refusing a production aesthetic of publishing ease. It was one thing to love a poem enough to hand-print the one time, but fifty, or even one hundred times? How much might one have to love a poem to hand print it, line upon line, one hundred and fifty times? One might think that very few poems might survive such a requirement. And so, too, to Anstee’s minimalisms: potentially condensed even further through the physical act of composing upon a fifty year old typewriter.

It is wonderful to see Ottawa poet, editor and publisher Cameron Anstee’s second full-length poetry title, following

Book of Annotations

(Picton ON: Invisible Publishing, 2018) [see my review of such here], his

Sheets: Typewriter Works

(Halifax NS/Toronto ON: Invisible Publishing, 2022). “This book began,” as he begins his “SOME AFTERWORDS” that end the collection, “following the death of my friend, the poet William Hawkins, on July 4, 2016, when I was gifted his Olivetti Lettera 30 typewriter.” Composed entirely, it would seem, upon the legendary late Ottawa poet and musician William Hawkins’ [see my obituary for Hawkins here] typewriter (and produced to replicate that particular typeface), Anstee’s Sheets: Typewriter Works furthers Anstee’s poetic explorations into and through the minimal, but through gestures that extend both the act and result of writing—both composition and erasure—into the deeply physical. The effect is striking and immediate, as one catches the imperfect image of the text on the page, and the occasional letter slightly askew. The process is reminiscent of how, years ago, Ottawa poet, publisher and bibliographer jwcurryspoke of curating his 1cent series of publications—each of which are poems produced through individually hand-stamping from a child’s set, one phrase or line at a time—as being curated, in part, through that measure of physicality: completely refusing a production aesthetic of publishing ease. It was one thing to love a poem enough to hand-print the one time, but fifty, or even one hundred times? How much might one have to love a poem to hand print it, line upon line, one hundred and fifty times? One might think that very few poems might survive such a requirement. And so, too, to Anstee’s minimalisms: potentially condensed even further through the physical act of composing upon a fifty year old typewriter.

Anstee works his collection across a sequence of project-sections: “Rehearsal,” “Afterworks I,” “St. Andrew Voices,” “Ottawa Poems,” “Baseline Variations,” “Afterworks II” and “Milostná Báseň.” “Ottawa Poems,” for example, exists as an erasure of Hawkins’ classic 1966 poem-sequence Ottawa Poems, examining and reworking the twenty-seven sections of Hawkins’ lines with his own typeface-as-erasure, and seeking through his words to discover an entirely different kind of thread. There really is something intriguing about watching Anstee rework Hawkins’ work with his own machine, knowing that first Anstee would have had to type out the entirety of Ottawa Poems(and perhaps, even multiple times) for the sake of attempting erasures; it would suggest, as well, that Anstee might just know those particular William Hawkins poems better than anyone else [Anstee was also editor of The Collected Poems of William Hawkins, which is also available through Invisible Publishing].

Sheets: Typewriter Works includes poems-in-homage, specifically through the two “Afterworks” sections, to creators such as Barbara Caruso, Jiří Valoch, Kate Siklosi and Dani Spinosa, Alex Porco, PSW, Mary Ellen Solt, Phyllis Webb, Nelson Ball, bill bissett and Nicky Drumbolis. But in the larger sense, Sheets: Typewriter Works holds an echo of Kingston writer Michael e. Casteels’ The Last White House at the End of the Row of White Houses (Invisible Publishing, 2016) [see my review of such here], or, more specifically, Toronto poet Dani Spinosa’s OO: Typewriter Poems (Invisible Publishing, 2020) [see my review of such here], in how he appears to approach this work as a kind of poetic study, one centred around the possibilities of the physical poetics of this generation of typewriter, as well as a variety of generations of typewriter poets. As his “NOTES TO THE POEMS” offers: “This book exists in conversation, directly and indirectly, with past and contemporary typewriter poets, and while I will not hazard to offer an inevitably incomplete list of the works and writers that are in the DNA of this book, the pieces in Afterworks I and Afterworks II, and their respective notes below, offer a partial glimpse of some of the reading and looking and thinking I was doing while working.”

There is a meditative kind of breathlessness to these understated gems, one that allows each poem to sit, not as a complete thought, but as individual gestures as both moments in space and as part of a lengthy, open-ended and even life-long sequence. While poets such as Mark Truscottmight compose short poems set in the moment, the poems included in Anstee’s Sheet: Typewriter Works offer a structure far larger, and more complex; as though his short sketches sit as stardust, a potentially life-long study of and through minimalism, gesture and utterances both visual and verbal, simply set as book-length units of sections, which are themselves built out of individual poems, lines and words. “We are stardust,” Joni Mitchell sang, “we are golden.” And in certain ways, perhaps everything that makes up a poem by Cameron Anstee is what everything everywhere else is made up of as well.

October 15, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Kelly Krumrie

Kelly Krumrie's first book, Math Class, was published by Calamari Archive in June 2022. Other creative and critical writing appears in journals such as Annulet, DIAGRAM, La Vague, Black Warrior Review, Full Stop, and The Explicator. She also writes a column for Tarpaulin Sky Magazine called figuring on math and science in art and literature. She holds a PhD in Creative Writing from the University of Denver. https://kellykrumrie.net/

Kelly Krumrie's first book, Math Class, was published by Calamari Archive in June 2022. Other creative and critical writing appears in journals such as Annulet, DIAGRAM, La Vague, Black Warrior Review, Full Stop, and The Explicator. She also writes a column for Tarpaulin Sky Magazine called figuring on math and science in art and literature. She holds a PhD in Creative Writing from the University of Denver. https://kellykrumrie.net/1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Well, Math Class (Calamari Archive, 2022) is my first book, so it’s probably too soon to tell, except, perhaps, I think I could say that I feel a little like I’ve taken a breath, or I feel a little stiller, something like that. In order to write the book, however, I quit my job and started a creative writing PhD program—nine years after my MFA—and this did change my life. I had fallen away from writing almost completely, and I was hardly reading at all. I was teaching middle school and was so tired all the time; I couldn’t think straight. But teaching allowed me to learn a bunch of new things—like math—without which I wouldn’t have been able to figure out how to get back into writing and what to do once I got there. I started this book about two months before beginning my PhD. So maybe the book did change my life.

My recent work feels very different from this. I wrote a book-length series of prose poems/fragments called No Measure (that I’m currently submitting to publishers) right after Math Class, and it’s different in form and content though thematically still touches on scientific language, particularly measurement, scale, and documentation. It’s a kind of love story rendered in the most technical language… I let myself let go of narrative, scene, and fictional conventions and puzzled together bits of language and landscape. Longing pushed back by objectivity.

Lately I’ve turned toward fiction again, and I’ve been writing about infrastructure, sidewalks, radio, sound. Something novel-like is taking shape. I recently described my current projects as Anne Carson’s Eros meets Thomas S. Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. This work is much looser than Math Class or No Measure: freer, not quite as constrained.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Oh, I don’t know what’s first. I always oscillated back and forth between poetry and fiction, settling more into fiction. In school, I focused on fiction. My mom likes to tell people about how quickly I read, how I memorized stories and poems and recited them, and at not much older than two, I begged her to teach me to write, and I would cry. I wanted to write my own stories. So, fiction first, I suppose. But even as a teenager I was most curious about language-driven fiction, messy stuff: I was gaga for Faulkner, Joyce, carried Ulysses around in my tennis bag in high school. That’s why the genre line is difficult for me. I’m more interested in language than narrative or character, more interested in how I can make the thing than what the thing is. But—Renee Gladman said something to this effect in a talk recently—fiction provides a fun frame to splash around in. Nonfiction doesn’t speak to me usually, except for criticism.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

All of these examples describe my process! I research a lot, a lot. Too much. And I take lots of notes: quotations, phrases, little bits of language, and I make word banks, kind of like a dare to myself to use as many words from the pile as I can. I’d say I’m slow, but most of my writing is pretty short and fragmented, so it doesn’t take too long to get to the end. First drafts appear close to their final shape. I’m careful, and I don’t like revising very much (that doesn’t mean I shouldn’t do it, though).

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Oh, interesting question. It usually begins from something I’ve read, or something someone has shown me: theoretical writing or some kind of fact or work of art. I’m definitely someone who writes short pieces that then combine. I know now that this is probably what will happen. I keep writing the same thing; I get really hung up on stuff. Math Class was first one short story, then another, then… here it is. I’ve written a few prose pieces over the last year about sidewalks and infrastructure. I’m not sure if they’ll accumulate into a book (a pretty strange book that’d be), but I can’t stop.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I like attending readings, and I’m happy to do them, but I don’t think they have any real role in my creative process. (Except that it is nice to be around other people.)

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Oh, gosh, yeah, this is pretty much all I think about. Math Class includes a list of sources at the end of the book—quotations that helped me shape the individual segments or that I found later and thought were applicable; they add a layer. I often begin with some kind of theoretical idea… For example, in Technics and Civilization, Lewis Mumford says something about there’s nothing perfectly circular in nature, and I don’t know if that’s true, but I liked thinking about it, and that launched me into the major plot point of Math Class (as well as its form).

What questions am I trying to answer? The question I’ve wondered about the longest is… well, maybe not a question, but a concern: I’ve always, always been super interested in grammar and syntax (I studied linguistics as an undergraduate), so as I’m writing, I’m navigating and playing around with words, phrases, and sentences through that lens. I’m most curious about “syntactic” words (function words, little words) that don’t really mean anything. What if I threw a bunch of them together? Can I make a sentence that way? A story? The past few years, I’ve been wondering most about math (hence this book) and what mathematical language means. With a number, there’s the idea, the sound for the word, the word written, the numeral, the number in an operation or equation, the number representing objects in the world… It’s a weird little thing.

I’m not sure I can answer this question. The question I’m trying to answer is something like: How can I use language in a particular way to manifest this thing that’s kind of outside language? (Which could be said for any writing? Or most of it?)

Currently I’m wondering about how to render sounds and radio waves.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Yikes! I don’t know. Like any other artist: a mirror, a storyteller, a questioner. I think the role should be to be as curious as possible. To learn and share out. To not be siloed.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Neither! I like it, and it’s often very helpful for me. I’ve been lucky to have some really lovely editors who give useful feedback and help me make the work better. Derek White and Garielle Lutz at Calamari gave such close attention to Math Class—really unbelievable attention and generous feedback. And to get sentence-level edits (and explanations!) from Garielle was a dream. But I’ve also published work with no editorial comment or modifications, and that’s fine too. Rarely has it been difficult.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?