Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 109

November 3, 2022

Field work

1.

In Goose Bay, Labrador , the salt air

slant. This long approaching chill

of split infinities, October. Pandemic months of inquiry,

as she researched sustainable agriculture,

tending low tunnels and degradable plastic mulch

; logged expanding yield: potato, turnip, green beans. Imagining

what could not be imagined: to extend each growing season.

A philosophy so difficult it could only benefit.

2.

In Goose Bay, Labrador , the salt air

brines on autumn’s shoulder. This unpredictability

of climate, water , the resilience

of a measure, stolen or this fear.

Her sudden death in that distant city; news relays

traditions, held from the Pyrenees to Lincolnshire

, informing bees of their master’s death: a knuckle’s rap

on each hive, offering “Your mistress

is dead , but please don’t leave.”

3.

In Goose Bay, Labrador , the salt air

, thickens: quick intake , of unfamiliar words.

The clouds packed with reflection

; a calligraphy of footpaths striate sandy plateau.

Someone

had to tell the bees. Her stock of textbooks, cellphone

, steel-toed boots. The spare room

in her mother’s house , that Rideau Terrace basement

where she’d hibernate, the twinkle

in her father’s eye. To light her way. This mute measure

of canaries in the coal mine; insect hopes.

4.

In Goose Bay, Labrador , the salt air

bristles. A courtship

of equal prayer. September sun, Albedo heat

, this thread of snow. To caretake such a loss,

a final resting place

at Beechwood Cemetery. Among John Newlove, Tommy Douglas,

Archibald Lampman. This grove of trees. Her ashes, cooled

, contained and accompanied , home

across the longest flight. How she further, provides

the soil, still a comfort.

, for Danica Brockwell (1996-2022)

November 2, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Claire Marie Stancek

Claire Marie Stancek

is the author of

wyrd] bird

(Omnidawn, 2020),

Oil Spell

(Omnidawn, 2018), and

MOUTHS

(Noemi, 2017). With Daniel Benjamin, she co-edited the anthology of Australian poetry,

Active Aesthetics

(Tuumba/Giramondo, 2016). With Lyn Hejinian and Jane Gregory, she co-edits Nion Editions, a chapbook press.

Claire Marie Stancek

is the author of

wyrd] bird

(Omnidawn, 2020),

Oil Spell

(Omnidawn, 2018), and

MOUTHS

(Noemi, 2017). With Daniel Benjamin, she co-edited the anthology of Australian poetry,

Active Aesthetics

(Tuumba/Giramondo, 2016). With Lyn Hejinian and Jane Gregory, she co-edits Nion Editions, a chapbook press.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Before I published my first book, I looked at my friends with books as being fundamentally different from regular people, like angels or supermodels. I would hear someone say casually, “My first book is forthcoming from wherever,” and I would feel an almost physical electrical jolt. When I got a phone call from J. Michael Martinez at Noemi Press, saying that they wanted to publish my book, MOUTHS, I was stunned and had basically an out of body experience. I remember holding the phone and looking out the window, and feeling a sensation of floating but also profound confusion, and I don’t think I said anything coherent to Michael during that call.

And of course, after MOUTHSwas published in 2017, I realized that my life didn’t actually feel different, and I was still looking and dreaming ahead. My second book, Oil Spell, was already on its way to press at Omnidawn Publishing. I was working on choices connected to its design and layout—it’s a complicated text visually, and the designers worked closely with me to make sure it was just right.

But on the subject of having one’s life changed, or yearning to, I’ve often felt that that intense longing is essential to being a poet. That productive, almost pleasurable, envy of the peers you admire most—that fervor to be part of a conversation that’s been unfolding in slow motion from book to book, as books respond to books and spark new thought—feels vital to creative work.

Maybe the feeling is social, and comes from needing to imagine interlocutors for a creative act which, in the case of poetry, can so often take place in solitude. Or maybe the yearning stems more from the act of creativity itself, the supernatural thrill of making something out of nothing, of putting things in relation to one another.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I have an inherent resistance to categories and can’t help but see poetry, fiction, and nonfiction as facets of one another, interconnected and symbiotic. Actually, one of the recurring debates in our home is in what section a book belongs on our shelves. Does Stein’s The World is Round go with children’s literature? Or with her other poetry? Or with philosophy? And then I go looking for The Waves in the poetry section but find it with the novels, or Douglas Kearney’s Mess and Mess and in theory but I find it in poetry.

I think that my category confusion, or my unwillingness to understand writing as only one thing, plays out in a lot of my work, actually. My poetry often wants to be prose and my academic writing edges stubbornly toward lyric. Essay and poetry, especially, seem very closely connected to one another in a tradition that includes Jacques Derrida, Paul de Man, Lyn Hejinian, Fred Moten, Anne Boyer, Bhanu Kapil, Maggie Nelson, CAConrad. Language’s slippage reveals, in a sleight of style, the possibility for flight.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I’m definitely a note-taker, and develop projects gradually out of whatever set of questions is obsessing me. My most recent book, wyrd] bird, retains much of the notebook form it sprang from. It’s a hybrid text about the 12th-century mystic, Hildegard of Bingen, and combines many forms: notebook entry, dream journal, and scrapbook of photographic ephemera.

When I’m not actively working on a specific project, my notebook fluidly moves in and through my thoughts like a radio transmitter, picking up bits of what I’m reading, questions, dreams, the number for the plumber, work reminders, the fact that a ladybug just landed on my page with a hollow clicking sound.

My concerns will usually coalesce and shape themselves out of that notebook, and how quickly that happens depends on the project and what’s going on in my life.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I tend myself not to write poems that function as discrete units, as gemmy surfaces containing distilled meaning, that could be extracted from their context and anthologized or recited. My poems are usually messier than that. They attain meaning cumulatively, through their relationship with other poems in the book, and a line re-sounds in a new context and in a new way, and a rhyme at long distance adds another echo, and an image returns but backwards, familiar but strange.

For this reason, dividing a manuscript into sections that make sense for publication in journals is always challenging for me. So is choosing what to read at a reading.

I write out of questions that I don’t know the answer to. To me, writing feels like asking, and asking again. For that reason, my poems are like an unsettled and impermanent positing that almost immediately must find new shape.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love the social aspects of poetry, whether it’s reading poems aloud, listening to other people read, sharing work in progress, discussing revisions, or talking about favorite lines, ideas, authors. Maybe best of all, I love working with students who are just starting to develop their creative practices because their excitement and discovery are continually reenergizing. As a shy person, I often have to work myself up to these public encounters, but the social anxiety with which they are charged only (usually) makes them more valuable to me.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

All of my books is motivated by a different set of questions. In wyrd] bird, one of the refrains was, What would it mean to write an utterly embodied book? In Oil Spell, my questions were more around how the polyvocal arrangement of texts created surprising relationships on the page. What becomes possible or impossible about resisting violent structures of power when voices meet in new ways? And then when writing MOUTHS, I kept asking, How can one sing at the end of the world?

I also love reading theory, and maybe most obviously my writing is informed by ecocriticism, feminism, and sound studies.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

There are so many different roles for writers. And I think all of them are essential in different ways and at different moments. Writers document. They remember. Writers research and theorize and educate and instruct and demonstrate and illustrate. Writers create worlds, they entertain and delight. Writers warn and prophesy. Writers illuminate new ways of thinking and being, and make those new possibilities possible. Writers identify problems and ask and insist that people be better. Writers share information.

Then again, there are also insidious roles for writers. Like in the way that writers can spread hatred or lies, or excuse violence, or sell harmful products, or sew doubt in order to mislead the public and further enrich powerful corporations. Oil Spelldis-arranges these voices, invoking counterspells.

I think for my own personal writing practice, what feels most pressing is to question. I believe that writers have a profound capacity to question received meaning, authoritative structures of knowledge-making, and ask what is true and untrue, what must change.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love working with editors. At Omnidawn, my editor is Rusty Morrison, and her insights always feel to me like being met on a profound and intimate way by someone who has thought deeply about my work, and in some ways understands it better than I do. I find the collaborative nature of editing to be both frightening and wildly exciting.

Actually, some of my favorite conversations with friends have been over manuscripts-in-progress, whether theirs or mine. I love sharing wine and just talking for hours about what’s going on in poems. Those conversations are different from teaching, but there are many points of connection in a workshop context. Students are generous and insightful readers of one another’s work, and it’s enlivening to be part of those conversations as creative work comes into being, collaboratively, through thoughtful conversations.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

As an undergraduate I remember learning that every day that Daniil Kharms failed to write, he put in his journal, “Today I wrote nothing.” I have always found that very moving, although I am not the kind of person who writes every day. I would love to write every day, but for me, the demands of life and of those who depend on me—especially as a woman—often feel more immediate.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My writing routines are fluid and usually built around the schedules of other people—of my children, my partner. I move in and out of attention as I am able. I write when my children are sleeping, I jot notes as I walk to the bus.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Books and music inspire my creativity. But, if I’m in a period of not-writing, I allow that fallow time to regenerate my spirit. And then I find that writing is still there for me when I’m ready again.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

For me, the word “home” recalls rural Ontario in the 90s. I smell viburnum, cold sweet mud from the banks of the stream, cat musk, mildew.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I think I’m always in a state of being influenced—by smells, cravings, the voices outside my window, that repetitive pinging sound, the architecture of the room, the ghosts in the space, the honking of the traffic outside.

Speaking of science’s influence, I love the “discovery” (as though poets didn’t always already know this!) that we as humans are not actually discreet beings. In an essay called “Holobiont by Birth” in Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, Scott F. Gilbert describes the profound imbrication of bodies with their environments, and the collaboration between bacteria and mammal bodies—like cows or humans—and insect bodies—like termites. A pregnant person develops two sets of nutrients in their milk: one for the newborn baby, and one for the bacteria that will colonize the baby’s gut. That’s just one example of many in this wonderful essay.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

So many! But for my current manuscript-in-progress, I’m reading a lot of children’s literature, and so on my desk at the moment I see Counting on Community by Innosanto Nagara, Kuma-Kuma Chan’s Travels by Kazue Takahashi, a bunch by Margaret Wise Brown and Ezra Jack Keats, nursery rhymes and songbooks.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d like to be more involved in the physical making of books. My sister-in-law, Anna Benjamin, is a talented artist, printmaker, and paper maker, and I’m inspired by her tactile relationship to the material of paper as a thing that starts, really, as a vat of mush. She describes “pulling pages”—a phrase I always find beautiful and disorienting—and the newly born paper needs to dry for weeks before it’s ready to hold ink.

At Nion Editions, the press I co-edit with Lyn Hejinian and Jane Gregory, we work with Derek Fenner, who is incredible, and he designs and typesets our books with exceptional skill. Then we have the books professionally bound in gorgeous hardback editions. So although I feel close to each book, and have watched each go through all the stages of becoming, the process is not a physical one for me—and then they arrive at my house by mail in a glorious box of color and light.

One day I’d love to make paper, work with a letterpress, and bind books by hand.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Maybe a deejay, connecting song to song and finding the edges of sounds that fit together, remixing, shaping and building a feeling, watching people dance. Or a builder who works with wood or clay, or yarn, or fabric.

But these are all ways of being a poet.

Something totally different I’d like to do is be a beekeeper. I love bees and I think I would find deep joy and peace if I devoted my days to being a custodian of their innumerable murmuring.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I guess I’ve never not been writing. But I don’t see it as a kind of doing that keeps me from other things. The relationships and activities that fill my day with their demands and joys—like being a mother or a partner, preparing food, walking with a friend, organizing an event, participating in a reading—also feel urgent and deeply connected to living a meaningful life.

Writing is the thing I do, like breathing or sleeping, that binds my soul to my body and releases it at the same time. If I were a bird, writing would be the sound I make.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I’m totally blown away by Motherhoodby Sheila Heti. I love movies but haven’t been watching very many recently. But I was so amazed by the Heti book that I watched Teenager Hamlet, directed by Margaux Williamson, and also co-starring Heti, and I loved it, too.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I’m writing a book of essays that combines literary criticism and memoir, tentatively called Moon Room. It’s about rhyme in children’s literature, which becomes a way to think through the experience of a complicated twin pregnancy and disability in the context of species loss and climate change.

November 1, 2022

MODL Press (2000-2009): an interview with ryan fitzpatrick, and a bibliography,

this interview was conducted over email from March to October 2022 as part of a project to document literary publishing. see my list of interviews and bibliographies of literary publications past and present here

ryan fitzpatrick is the publisher of Model Press, a revisioning of MODL Press (the thing you just read about). He is also the author of four books of poetry, including the recent Coast Mountain Foot (Talonbooks 2021) and the forthcoming Sunny Ways (Invisible 2023).

Q: How did MODL Press first start?

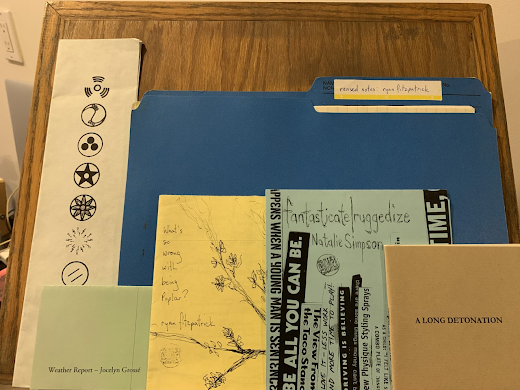

Q: How did MODL Press first start? A: Okay, so, if I were to choose an inaugural moment, I might pick the view onto the stage at the year-end reading of the University of Calgary’s creative writing classes in, what, 1999 maybe? I had just worked with my classmates to put together a class chapbook for Nicole Markotic’s intro poetry workshop, sitting for hours in a computer lab at SAIT where we could use a photocopier for free. I was pretty proud of the book we put together, but when I got to the reading, I was amazed to see an array of very different chapbooks laid out on the top of the piano at the BeatNiq Jazz Club at the bottom of the Grain Exchange building on 1st. Fred Wah had challenged his class to build chapbooks of their own and I was inspired by the way they were self-publishing and organized. I bought copies of chapbooks by Tillie Sanchez and Jill Hartman, who were members of the short lived Phu collective with Natalie Simpson, Trevor Speller, Darren Matthies, and Lindsay Tipping. I later ended picking up Darren’s and Lindsay’s chapbooks at the campus bookstore.

Inspired, I decided to self-publish the project I had written in Nicole’s class – a weirdo narrative long poem titled revised notes. Self-publication allowed me, to put it in the corniest terms, to control the means of production. I imagined revised notes as something scrappy, printed on a messy mix of paper types with handwritten chunks. I sat at the inkjet printer in my parents’ basement and fed pages through individually to get the effect I wanted. It was an immense pain in the ass.

When I needed a name for the press, I riffed on the name of a band I was in – The Mod Factor – and called it mod1press. Later, I realized that this name was incomprehensible, so I changed it to modl press. When I realized that the lowercase made the name inscrutable, I changed it again to MODL Press. My current online press is basically the same, except I’ve corrected it one more time to Model Press.

Q: I feel as though I have a copy of that around somewhere. Is revised notesthe full-sized chapbook? And what kind of print runs and distribution were you doing for such? I would presume you were handing out copies, most of the time. What was the response to these first publications?

A: revised notes is the larger format one bound in the blue file folder. My overcomplicated first attempt to play with book format.

Print run and distribution were something I was continuously changing as I went, but most of the books settled around 50 copies. That felt like a magic number to me, because it was an amount that allowed me to give a decent amount to the author (usually half of the run), still be able to sell or give away a few, and feel like I wasn’t holding onto books forever. Any time I printed more than 50, I felt like I ended up sitting on a ton of copies. I really wasn’t interested in keeping books in print. For me, one of the strengths of chapbooks was their ephemerality. It was all about circulating work that was new to whoever was around.

I think my approach to distribution was shaped by this, though I wouldn’t claim to be consistent about it. I slowly drifted from charging a little for books, usually enough to recoup some of the costs, until I got a review that called out the price of one of my books that made me fed up with the process of trying to sell things. The books I made over the last couple years of the press were printed super cheap and handed out at readings to whoever I ran into. It was completely haphazard and absolutely the best way to circulate poetry.

Q: The notion of the ephemeral, I would think, would also allow for the immediacy of presenting new work that an author might still be feeling out. Did the possibility of publishing, and self-publishing, shift the ways you saw or even presented your own writing?

Q: The notion of the ephemeral, I would think, would also allow for the immediacy of presenting new work that an author might still be feeling out. Did the possibility of publishing, and self-publishing, shift the ways you saw or even presented your own writing? A: Definitely. The speed and ephemerality of chapbooks and self-publishing gave me this permission to think about poetry as an ongoing process. Work could be scrappy, unfinished, unpolished, and still make meaningful connections. The speed allowed for content that was too timely or obscure for poetry’s slow temporalities - political jabs, pop culture references, community in-jokes. I think that fast publishing is an important part of the poetry ecosystem and I wish more writers would embrace ephemerality in their approach to both publishing and their work, though I get the appeal of working slowly as well. Personally I found the speed of chapbook publishing really freeing. I could write something and quickly circulate that draft to a small group of people.

For me, it’s also been tied to posting work on my blog and later on social media. Sharing work online was central to the boom in poetry blogs that happened in the 2000s and I was absolutely drawn to that because it felt more immediate and, to be honest, it felt more possible than publishing in magazines or books. It definitely shaped my approach to poetry and I’m probably still too in love with sharing my own in-progress work online.

Q: You mention the original impulse and prompts for beginning the press, but what else was happening around you at the time? I suspect what Derek Beaulieu was doing, for example, through his housepress might have influenced some of your publishing structures. What other influences were in play for the press?

A: It was about an upswell of activity that I came into in the early 2000s. A lot of that energy was driven by folks coming out of the creative writing program, but not all of it. My feeling is that Calgary was going through a bit of a transition point in the poetry community. People’s aesthetics and investments shifted over the course of the decade. In the early 2000s, it seemed like everyone was doing something: starting a press, a magazine, a reading series. A lot of it was ad-hoc. Some of it was more professionalized (meaning there was money involved). I was inspired less by the work of any one person than a suite of publications, groups, and happenings: filling Station, Dandelion,Yard, Bemused, Three Blind Mice, Haus and The Ranch, Single Onion, Semi-Precious, (Twat) Team, The Sabbath, Flywheel, In Grave Ink, (orange), Nod, Mutton Busting (I’m forgetting a lot). This in addition to all the writers I was engaging with online, at first through the Buffalo Poetics listserv and afterward through the brief explosion of poetry blogs. I found this rush of activity energizing and inspirational. I wanted in so I joined filling Station after being invited by Tom Muir and started publishing - first, self-publishing in a very scuffed imitation of Jill Hartman, then publishing other folks.

I suspect that some of my feelings come out of a nostalgia for that early-2000s moment, a nostalgia for the improvisational energy of young people who have some faith in culture’s ability to make community, especially in a regional city like Calgary where we had to learn to make our own fun. But it’s not a coincidence that MODL petered out when it did, because it seemed like by the end of the decade the energy of the city and its literary spaces had mutated into something different, something that, to me at least, felt more antagonistic and invested in a cult of celebrity around a handful of figures in the scene. I drifted toward the music and art scenes which at that moment were more invested in diy community strangeness.

Q: What role, if any, did your work with MODL direct the ways in which you engaged with communities beyond Calgary? Were you aware of much of small publishing beyond Calgary’s borders during those early days?

A: My guess is other folks who were around will give you a different answer, but I was pretty strongly connected to the local, at least as a publisher. I don’t think I published anyone who didn’t have a Calgary connection, but I do remember doing a few sales and swaps over the Buffalo Poetics Listserv. I slowly became aware of what was going on outside of town as people from other cities came to give readings, as I talked to other poets in town who had moved from other places, and through the growing network of blogs that were popular in the early to mid 2000s. But in terms of publishing, I was more likely to invite those out-of-town writers to submit to filling Station than to publish them with MODL, maybe because filling Station felt like a professional enterprise with a longer history, even though fS was constantly at threat of shutting down.

Because I did small press in a very local way before jumping into the wider world of it, I find I’m always a little too aware that there is way more activity going on than is apparent in the dominant promotional cycles of poetryworld, where everything is keyed to specific presses and cities. I kind of wish I was more involved with communities outside of Calgary, but also I’m grateful to have focused so much time with the strange particularities of the local. Local spaces are really where poetry bubbles over and gets interesting, if there’s room for them to develop.

Q: How did producing and distributing small chapbooks through MODL affect the ways in which you approached and considered community? Or even your own writing?

Q: How did producing and distributing small chapbooks through MODL affect the ways in which you approached and considered community? Or even your own writing? A: I mean, if I put this in the corniest way possible, doesn’t taking the means of production into your own hands underline the way that publishing should primarily be about circulating material that members of your community (however you define that word) is invested in and excited by? That’s maybe why the local appealed to me as a site for circulation, because I could honour one person’s work by picking it up and passing it down the line. It’s like delivering the news!

If it’s affected my own work, it’s probably made me pretty strident about poetry not having to be so polished all the time, because there can be stages to publication. You should be able to put out in progress versions of your work through the scrappy channels of small press. Because small press is ephemeral and local, it can support writers where they’re at in a particular moment. Writing and publication can be quick as well as slow. I think the recognition of that has made my work too timely sometimes. And if my experience with book publishers and the literary magazine industrial complex has taught me anything, it’s that timeliness is not always a valued quality.

Q: What was behind the decision to end the press? Was it a decision deliberately made, or one through circumstance? Were there any frustrations that drove the decision, or did you simply run out of energy, time or even enthusiasm?

A: It was a lot of things: the shifting of the local writing community, my own move into academia from being a kind of literary townie, years of working multiple jobs. Ultimately, it was an increasing lack of energy paired with the reality that I had to focus what energy I had elsewhere. I still feel bad about a few publications closer to the end of the press that just never got finished because I couldn’t find time or energy to finish them. The press just kind of ended without me being deliberate about it. There was the possibility that I might publish something for years after I had actually stopped. Though much later, I did think about making a big splash out of ending the press by selling the name (plus my long-arm stapler) for $5!

Q: Finally, what prompted you to restart the press under a new name and online? How does the new MODEL relate, at all, to MODL? Apart from the obvious differences in production, what are the differences you are finding to running a press now to running a press then? What has changed, and what remains the same?

A: Well, Model relates to MODL in that it’s still me doing the work. And there’s a continuity in the design. But why bring it back now? Well, I was feeling increasingly disconnected from poetry world between moving to a new city and the general anonymity of publishing (especially magazine publishing). The social distance of the pandemic was kind of the final straw and I felt like I needed something that would reconnect me to the community elements of poetry in a positive way. I juggled a lot of possibilities like an online magazine or some kind of newsletter.

Eventually, I landed on the chapbook but decided to make it leaner and quicker to produce. Rather than the adhoc approach of MODL, the “model” of Model became quite deliberate. I’ve been producing the books in batches in such a way that the press acts a little like a magazine where the individual pieces are released over weeks or months. The design of each book is deliberately minimal and the biggest decision I make when building each book is the page size. The online element came out of pandemic necessity, but I like the way it focuses me on circulation rather than aesthetics. The goal is to get pieces in front of as many eyes as I can, which has a limit, but less of a limit than the material one of an analog small press. Admittedly, I pay for this with the loss of the analog thrills of the paper chapbook and every once in a while I think I’ll eventually go back to making print books. But right now, this approach is working for me and I’ll keep it up as long as people are interested and I’m having fun with it.

MODL Press “Bibliography” (spotty bc I didn’t keep good records and didn’t have enough spoons in my 20s to even think to do something like that)

pre-2000

a couple of self-published chapbooks I made that I am too embarrassed to admit to

2000

revised notes– ryan fitzpatrick(Class project for Nicole Markotić’s intro poetry workshop. I spent hours feeding different kinds of paper through my parents’ inkjet printer because I thought it would look cool. This book is the source of confusion about the press’ name because it started as mod1 press—a reference to the band I had been in—and was changed to modl press and then to the more deliberate MODL Press. For the record, it’s meant to be Model not Modal. I always liked the joke that the press wasn’t a model press and then made it clear by misspelling the press’ name.)

2002

PyongTaek – ryan fitzpatrick

2003?

Pamphlet Series (all w/ art by ryan fitzpatrick)

“What’s so wrong with being poplar?” – ryan fitzpatrick

“fantasticate|ruggedize” – Natalie Simpson

“Fylfot” – Jill Hartman

“Weather Report” – Jocelyn Grossé

“vanilla” and “a step in June” – Chris Ewart

“Pass the Doughnuts, Please” - Jason Christie

“Pitt Graphic 4” – derek beaulieu

(I was living with my parents and my dad had bought a shitty old photocopier, so I started experimenting with pamphlets because I could put them together quickly and make them on the cheap. I mostly asked folks who were around, friends and local folks whose work I admired. The accompanying artwork solidified the design aesthetic for the first couple years, which was cut up, photocopier mess, handwritten stuff—anything I could throw together that looked vaguely cool and didn’t give away that I was a shitty artist.)

2004

“Hey Mom, I’ve Been Censored”– filling Station collab for Freedom to Read week ft. Chris Ewart, J Alary, Jason Christie, Carmen Derkson, Jocelyn Grossé, ryan fitzpatrick

A Long Detonation– ryan fitzpatrick

(The last gasp of my failed first manuscript The Ogden Shops. After this I really focused on publishing other folks work rather than my own.)

welcome to asian women in business a one stop site for entrepreneurs – Larissa Lai

Cover Art by ryan fitzpatrick

(Produced in two editions, the second for Yasmin Ladha’s ACAD class, I think? Published because Larissa approached me at a reading and said she was experimenting with Flarf too. This piece is probably too serious to be Flarf, but it’s still great.)

2005

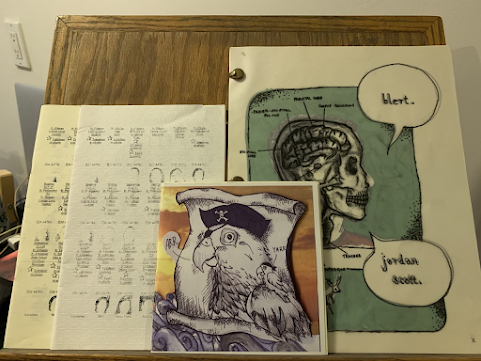

Pirate Lore – Brea Burton, Jill Hartman, and Cara Hedley

Cover Art by Sandy Ewart (credited as Sandy Lam)

(Probably the nicest looking book I produced thanks to Sandy’s artwork. This is one of the only places that Brea, Jill, and Cara had their work published together as a collaboration, even though they were regularly performing as a group at this time.)

Asian History Month chapbook ft. Crystal Mimura, Sandy Lam, Dale Lee Kwong, Weyman Chan

ffllj – derek beaulieu

Cover Art by ryan fitzpatrick

blert – Jordan Scott

Cover Art by Sandy Ewart (credited as Sandy Lam)

(Maybe the second nicest looking book I produced thanks to Sandy’s artwork, but marred by a couple weirdo design decisions on my part.)

2006

Nascent Fashion– Larissa Lai

Cover Art by Travis Murphy

(Published because I was erroneously credited in the anthology Post-Prairie with publishing a book Larissa had self-published. This book took forever to produce because Travis took his time with the cover. I stopped including cover artwork after this book. I received a review in filling Station that belaboured the fact that I was charging $10 for the book. I stopped charging for books after that review. Both of those things were detracting from something that was supposed to be fun and not feel like work, especially in a moment for me where I was working seven days a week at two jobs.)

2007

Pamphlet Series ft/ Helen Hajnoczky, Aaron Giovannone, Emily Carr, Bronwyn Haslam, Weyman Chan, Laurie Fuhr, Ian Kinney

(published for the 2007 Blow Out reading? This is probably my favourite MODL publication. I showed up to the book-selling table at the event with a box of these really plain looking pamphlets and people seemed really annoyed that I was asking them to “dig through the box” and “take some for free.” Between Larissa’s book, which took forever to produce and wasn’t received very well, and my general inability to do the things a professional press would do, I felt freed by the fact that I could show up with this cleanly designed but otherwise messy “book object”—a strange “shuffle anthology”. I doubt anyone other than me has the full set, though maybe I’m wrong.)

2007/2008?

Big Vocabulary– Nicole Markotić

(I don’t have a copy of this anymore, but I remember it took too long to put together, so I hand crumpled a bunch of interoffice mailers to make it look like it had been “floating around the department for a while”)

2008

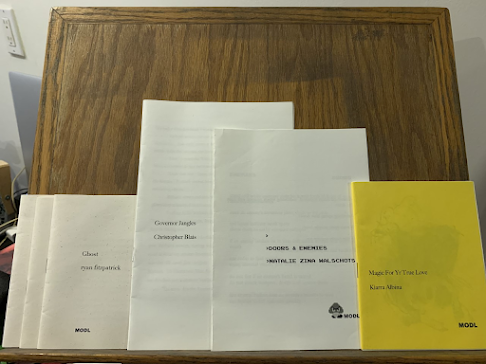

Governor Jangles– Christopher Blais

Doors and Enemies– Natalie Zina Walschots

Magic For Yr True Love(reprint) – Kiarra Albina

Poems – ryan fitzpatrick

(comp + CD produced for “Future Fest” at Springbank Middle School)

2009?

Ghost – ryan fitzpatrick

Stray – ryan fitzpatrick

Faint – ryan fitzpatrick

(produced as a series w/ similar design)

Unpublished/Unfinished (because I couldn’t get my shit together)

a collaborative piece by derek beaulieu and Christopher Blais

Stephen Harper Magazine collab co-edited w/ Natalie Zina Walschots

Palliative Care– Meghan Doraty

October 31, 2022

Nicole McCarthy, A SUMMONING: MEMORY EXPERIMENTS

He takes me on vacations while he’s home, transporting our state of mind from deployment life to post-deployment lets-try-hard-for-normalcy life. ‘Let’s take a picture’ rolls off his tongue with every other breath. Each trip he hopes will produce pictures that will replace every frame/every profile image/every evidence of the life I’ve led without him here.

We can live and linger forever inside a frame.

“When was this photo taken?”

“Who were you with here?”

“I wonder what country I was in then.”

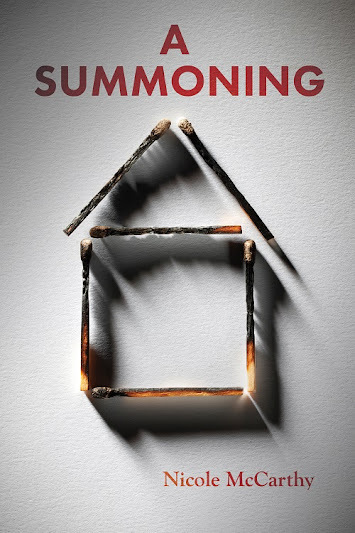

Seattle poet Nicole McCarthy’s full-length debut is

A SUMMONING: MEMORY EXPERIMENTS

(Manhattan KS: Heavy Feather Review, 2022), a layering of memory, trauma and erasure, working to salvage what should be salvaged and leaving all else behind. As she writes, early on: “Our memory palace is disintegrating before our eyes and by our hands. By selling, we are evicting memories, leaving them to fade and be overridden by others.” Through accumulating and even overlapping and obscured fragments of image, scraps and lyric prose, McCarthy explores how experience changes both the body and memory itself; living as a military spouse, she writes of deployments that shift geography and of long absences marked across a calendar path, while existing across the silence of an unfamiliar house. “Am I a memory romantic?” she writes, early on. She writes a layering, overlapping series of prose-blocks, layered to the point of illegibility, as one memory begins to obscure another, and simultaneously; memories enough that there is nothing left but an obscured text that folds into a textual mush. She writes an obscured text, an overlapping text, and sections crossed-out, offering both the archive and the erasure, attempting to both document and set herself correct, even as she repeatedly and routinely articulates an indeterminate foundation. If she can’t trust her own memory, how does anything else get built?

Seattle poet Nicole McCarthy’s full-length debut is

A SUMMONING: MEMORY EXPERIMENTS

(Manhattan KS: Heavy Feather Review, 2022), a layering of memory, trauma and erasure, working to salvage what should be salvaged and leaving all else behind. As she writes, early on: “Our memory palace is disintegrating before our eyes and by our hands. By selling, we are evicting memories, leaving them to fade and be overridden by others.” Through accumulating and even overlapping and obscured fragments of image, scraps and lyric prose, McCarthy explores how experience changes both the body and memory itself; living as a military spouse, she writes of deployments that shift geography and of long absences marked across a calendar path, while existing across the silence of an unfamiliar house. “Am I a memory romantic?” she writes, early on. She writes a layering, overlapping series of prose-blocks, layered to the point of illegibility, as one memory begins to obscure another, and simultaneously; memories enough that there is nothing left but an obscured text that folds into a textual mush. She writes an obscured text, an overlapping text, and sections crossed-out, offering both the archive and the erasure, attempting to both document and set herself correct, even as she repeatedly and routinely articulates an indeterminate foundation. If she can’t trust her own memory, how does anything else get built? I’m a ghost unwilling to leave these shared spaces after everyone else has vacated. My husband left toward his new residence without a second glance back at the house we shared for six years. I sit in front of the fireplace, in our hollow home, crying over all that’s bound to be lost.

October 30, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Teo Eve

Teo Eve

is a poet, writer and workshop facilitator based between Nottingham and London. Teo's debut poetry collection

The Ox House

is now available from Penteract Press. The image of Teo provided was drawn by publisher and artist Alban Low.

Teo Eve

is a poet, writer and workshop facilitator based between Nottingham and London. Teo's debut poetry collection

The Ox House

is now available from Penteract Press. The image of Teo provided was drawn by publisher and artist Alban Low.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I'm answering this a month before my debut (The Ox House, Penteract Press, 2022)'s official release date, so I'm not sure yet! But the hype online has been phenomenal and since its release was announced I've been invited onto reading teams for magazines, asked to deliver workshops and have been approached by editors and agents for other not-so-secret projects. Quite honestly sometimes I feel like I can't really keep up with all the things happening right now, but I hope this trajectory continues. Of course, there's always a chance that when the book's actually out people will think I'm a hack and lose interest...

Before The Ox House was accepted by Penteract, I had a few collections and pamphlets long- and short-listed for publication by other presses. These collections had some great poems in them but were marred by inconsistency. I think the biggest difference between The Ox House and anything I'd created before is its singular vision: The Ox House is all about the alphabet, celebrating its history, graphology and phonology. The more I write the more I'm becoming a concept-oriented, as a reader as well as a writer. A collection can have some phenomenal poems, but if it doesn't work as a whole then it won't excite me. It's like the difference between an 'album artist' and a 'singles artist', to me. A handful of catchy pop songs does not a good album make.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I didn't! I started writing fiction when I was in Primary School. I came to poetry much later, in Sixth Form - and even then, it wasn't something I took seriously for years. I wouldn't say I have a preference of which form to write, but I find it much easier to fit writing poems around my job compared to the intensely sustained concentration span you need for a novel.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I've always been a quick writer of poems. I've had a few I've been churning over and chipping away at for months/years, but a lot of the time I write a poem, edit it there and then, and re-write it again until I'm happy. I handwrite first drafts more often than not so when I type them up they go through another round of edits, but I don't really plan my poems. It's more that I get a line or an image in my head and hammer it into shape. In terms of large-scale projects, I feel I wait frustratingly long periods of times between ideas but as soon as I'm set on one, the poems themselves come relatively easily.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I find it difficult to think in terms of individual poems. Between projects, I might write stand-alone pieces (usually a line pops into my head and I'm fascinated by the rhythm or image of it, so I churn it over in my mind and write it out to see where it goes...) until I finally settle on one piece I really like the form or theme of. Writing a poem I particularly love is an uncorking: afterwards, the ideas just flow. After finishing The Ox House I was pretty frustrated because I didn't know what my next project was going to be, but then I created two visual poems in one sitting. That two-page document quickly spiraled/blossomed into I Imagine an Image, my seeking-a-home visual poetry collection. I have tried combining already-existing short pieces into a larger project before, but all attempts at publishing them so far have been unsuccessful.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I don't believe in the separation of 'page' and 'stage' poetry because I think a good poem is a good poem and a good poem should work on the page as well as the stage. Poems that are flat and lifeless on the page but come to life in performances due to affectations and emphasis are still flat and lifeless on the page. Having said that, as I lean more and more into visual poetry, just how I can perform my work is becoming increasingly challenging!

I get really nervous during readings, which is strange given that I'm a teacher by profession so I'm essentially performing all of the time. I suppose it's something about the immediacy of reaction you're experiencing your audience experience: I think I'd be nervous watching someone read my books, too. Having said that, nerves are really something I need to practise out of: I'm always aware that I should be doing more readings.

On that note, I'm performing a collaboration alongside Anthony Etherin of Penteract Press as part of the European Poetry Festival, at 7:30pm Saturday the 25th of June [2022] in Rich Mix in Bethnal Green, London. It's completely free and we'd love people to come along.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I'm aware of how post-modernist and metatextual this will sound, but I really do feel like my poems are all about the possibility of language. I'm not much interested in poetry that feels like someone's diary, and language seems to be a universal topic almost all readers of poetry have an interest in. Even if I start writing a poem about a distinct theme, it often ends up becoming a poem about how the poem is writing 'about' that theme. I Imagine an Image is ostensibly a collection of love poetry - so many of its pieces are about togetherness and separation, romantically and politically - but really it's a collection exploring how we can express emotions, conflict and the rupturing of society in language. Would it be more striking to respond to these questions and themes with images alone? Is there a universal language, or a universal image, for love and thought, or are these bound by and can only be channeled through semantics?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think it's such an exciting time to be a writer! Language change has always been constant, but I do wonder if we are witnessing an acceleration of this in the internet age, both thanks to an increased exposure to global languages and the way that digital forms allow for a speedy and cheap dissemination of innovative texts that would have been near-impossible to distribute using traditional printing technologies. Moreover, we are seeing a greater social awareness, including in terms of how language is used to describe and prescribe gender.

I don't believe writers have roles as such, but we do have a responsibility to be attentive to language change and use language with sensitivity. Writers can write whatever they want, sure, but we must be aware to the fact that our writing will impact the world, in however a minor way. Writers should consider what type of world they want to live in, and how their writing can reinforce this.

Lately we've witnessed a bastardisation of language in mass media and politics, with simplistic and reductionist sloganeering fanning the flames of division. I very much believe in the Geoffrey Hill school of making language 'difficult' to resist against such tyrannical simplication. Part of the motivation behind The Ox House was considering what letters can do, rather than what they do do and have done. Looking around at a world marked or marred by increasing nationalism and far-right movements, I feel like it is my duty to interrogate the language that has allowed this.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I'm lucky I suppose to never have had a difficult experience with an editor. I like to think I'm open enough that if an editor suggests vast changes to my work, I'd respect their impartiality, professionalism and vision and take these into account. One of the benefits of studying Creative Writing at uni is you learn to let you guard down - you need to be receptive to constructive feedback, however critical.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

When I was studying my MA in English Studies at the University of Nottingham, I enrolled on several Creative Writing modules. One of the set texts for our Fiction Writing Workshop was Ron Carlson's Ron Carlson Writes a Story, which essentially revolves around two pieces of advice: (1) when you're stuck, revert to physicality; and (2) don't. stop. writing. until. you've. finished. the. thing.

I remember some of my peers being frustrated with the book ('don't stop until you've finished writing? that's awful advice! tell me how to actually write!'), but I've found it incredibly useful. I love writing, yes, but it is discipline and it is work. Sit down, turn off your phone, and when the going gets tough carry on. It doesn't matter how messy or how skeletal the first draft is; as long as you've erected scaffolding, you've got something to work on or off afterwards.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

I feel like I alternate between having a 'fiction brain' on and a 'poetry brain' on, and I rarely pursue a prose and poetry project at the same time. I think it's because I like being immersed in a project: I always have one dominant work-in-progress at a time and I might occasionally start sketches for future ideas but I've historically struggled juggling ideas. Every time I switch back from poetry to prose or vice-versa the first few weeks tend to be a process of re-learning, getting back into the swing of the genre. Having said that, I do feel like there's quite a lot of overlap between my poetry and prose, even if they're quite obviously different on the surface. My novel, currently titled What Will We Build From The Ruins? (for which I'm seeking an agent or publisher) contains some of the best 'poetry' I've ever written! I think sometimes I need to cleanse myself in one genre before I can re-approach another: I write more poetry than prose, but cleansing myself in fiction can help me approach my poetry with a refreshed pair of eyes.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I wish I had a routine! I work 9-5 so my life pretty much revolves around that. When I've got a big writing project on during the winter I usually find it easy to dedicate a couple of hours in the evening to it, but when it's summer and I just want to be outside after work, my writing admittedly takes a back seat. I steal snatches of time here and there and do what I can, but at the minute I'm enjoying putting life and pleasure over pen and paper. Having said that, these aren't mutually exclusive, and as soon as I properly start on my second novel I'm going to do my best to do a Ron Carlson and just sit at the desk til the thing is done.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I'm pretty vampiric so whenever I get stuck I pick up a book, flick through it and usually find myself inspired to write something. Much of my poetry is a response to something I've seen or read so I've never found myself bereft of inspiration. The bigger challenge is finding the time to write...

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Burning wood! My mother is from rural Italy and we tend to spend summers on the farm. Occasionally the early morning breeze will bring with it the scent of wood on a fire. Everytime I smell a bonfire or am at a fireworks show, I'm transported to that small village in Italy.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

After graduating from my BA in English, I was sick of books. I was sick of reading and I was sick of writing. I got really into visiting art museums and took up painting, but never developed the technical skills to match my vision.

I was a bad poet at university and hardly any of the poems I wrote between my BA and MA had any value, but when I took up writing again during my MA I was keen to integrate the aesthetic sensibilities I had started to learn from painting into my poetry. Around the same time I was getting into Imagism and pursued a portrayal of the concrete, but discovering visual poetry really was a game changer. After turning in a concrete poem I'd made as part of my MA Creative Writing course, a peer told me that she could 'see it in a gallery'. That became a new ideal for me: poems that had a visual, as well as a literary, sensibility. After all, is there anything uglier than a poorly-lineated poem!?

I think this is the reason why my debut poetry collection The Ox House (Penteract Press, 2022) became a book of two halves. It's a poetry book, yes, but each poem is titled after a large capital letter form that act as both homage to Medieval manuscripts' illuminated letters and as visual art works in and of themselves; and the lineation, graphology and typesetting of the individual poems became as or more important as/than any 'meaning' they conveyed.

I stretched my visual experimentation even further when creating I Imagine an Image. Assembling this collection, I set a test pieces would have to pass to be included. Each poem had to work as both a poem and a piece of visual art, or they wouldn't get a spot in the collection. Their forms and content often communicate, but even the more text-heavy pieces had to look pretty. Almost all of the poems in this collection are contained within a black ink border, designed to replicate the frames around paintings you get on gallery walls.

I really want my poetry to break out the boundaries of books and be everywhere. I want my poetry on mugs, on walls, on t-shirts, in galleries, on album covers and in magazines. To achieve that, it has to look nice. Visual immediacy of the form increasingly takes centre stage for me: if a poem looks like a mess and is uninviting to the eye, why should I bother reading it?

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Oh, so many! I'll always be indebted to Nikki Dudley - she's a brilliant poet and a huge inspiration for my work, and as editor of streetcake magazine has always been a champion of my poetry.

Ali Smith is probably my favourite fiction writer, but the word play and sharp attention to the playful fluidity of language has really informed my poetry in particular.

It was the honour of my life to have The Ox House accepted by Penteract Press - not only has Penteract put out some incredible books, but Anthony Etherin has achieved, I think, the closest thing to formal perfection we'll see in 21st century poetry. Penteract have really attracted a whole host of interesting and innovative writers: listening to The Penteract Podcast while working a pretty monotonous admin job, and learning all about the practices of fantastic poets such as Christian Bök really expanded my idea of what poetry could be.

I've had some great exchanges with Sascha Engel (Breaking the Alphabet, Little Black Cart 2022) about the alphabet, Ancient Egypt and experimental writing, and I'm lucky enough to have made so many poetry people through Twitter and my MA who provide invaluable feedback on my work and are great friends besides.

I'll always be thankful to Vicky Sparrow, Lila Matsumoto, Matthew Welton, Spencer Jordan, and Thomas Legendre, my Creative Writing lecturers at the University of Nottingham for all of their guidance and support.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I'd love to write a children's book! I've already got a poetry book out, a non-fiction book coming out and a novel waiting for a home, but really I'd like to write at least one of each literary form. I guess I should probably have a go at a play, too, but there's something about writing solely dialogue that's so intimidating to me.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I'm fascinated by urban design and when I was younger I vaguely dreamt of becoming an architect, but I never had the mathematical skills to pursue that as a career. But how different is urban design and architecture from creating poetry, anyway? I imagine there's a similar attentiveness to form and structure. Some poems I've written that are more traditionally-lineated than my visual work explicitly reference or are influenced by architecture in their form and content, and I had great fun trying to evoke Nottingham's urban landscape in the poems I contributed to Writing Notts 2021: An Anthology of Nottinghamshire Poetry.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I think I'm a frustrated would-be rock'n'roll star. I love doing karaoke and the over-the-top performance of singing and acting theatrically larger-than-life on a stage. Ironically I'm quite timid during poetry readings, but I think the compulsory pre-karaoke beers help with the nerves! Unfortunately I don't have the rhythm or voice for it. I actually started off by writing lyrics, which gradually morphed into poetry when I realised no-one would want to hear me sing them!

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I recently (reluctantly) re-read The Great Gatsby, which was my favourite novel(la) as a 17-18 year old and which I hadn't revisited in years. I was afraid to read it in case the magic had worn off for me, but I was pleasantly surprised to find that I appreciated it arguably more this time around than when I was a kid. There's just something about its leanness, how nothing is extraneous and every word has been placed with the precision of a poet. It's amazing, too, how much emotion the whole thing has while not coming across as cliched or sickly-sweet. I maintain that The Great Gatsby is an ideal of the novel (novella?) form, and I'd love to aspire to its focus. I'm admittedly not very film literate, but Her (2013, Spike Jonze) broke me.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I just finished(!?) writing my visual poetry collection, I Imagine an Image, and I've recently been asked to write a book on the history of visual poetry so I'm slowly building myself up to researching and planning that. However ideas for my second novel have been brewing in the back of my mind lately and I'm very keen to make a proper start on that (really, a restart) while continuing looking for a home for my first novel, What Will We Build From The Ruins? At the minute I'm enjoying a much-needed pause between projects - I really did just finish I Imagine an Image less than a week before writing this - but I'm sure I'm going to feel the itch to write again soon. Besides from this, I'm currently in the stage of making final edits to my debut work of autofiction, On Shaving, which is set to be released by Beir Bua Press in March 2023...

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

October 29, 2022

Chus Pato, The Face of the Quartzes, trans. Erín Moure

Galicia is a promontory of stone sitting on the Iberian peninsula above Portugal. Its language, Galician, derived from Latin, is the root language of modern Portuguese and stubbornly survives to the north of Portugal. Through long parts of Spain, Galicia, with its Celtic substrate and different history and language, has never become simply Spanish. The Face of the Quartzes is rooted in Ourense, the Galician interior city bisected by the Miño River, where the poet was born and raised during the long 20th-century Spanish dictatorship of Francisco Franco. Ourense was long ago the Roman city of gold (ouro) and of dawn’s golden light (aurora); Galicia may have been at the fringe of the Roman Empire but it was a country of philosophy, and of international travel and influence. Its mountainous rocky interior was mined for gold and iron, metals key to ornament and armament. Its ports were cosmopolitan. Its fishermen were known from the Baltic to Africa to the shores of Newfoundland and Maine. It was a place peripheral and central at the same time. Though today Galicia is even more peripheral in world politics, Chus Pato’s poetry recenters it. (“Passages and the Unrequitable Gift: The Face of the Quartzes by Chus Pato, A translator’s introduction”)

Sorting books in a corner of my office, I realized I hadn’t yet gone through Galician poet Chus Pato’s latest work translated into English,

The Face of the Quartzes

, translated by Montreal poet, translator and critic Erín Moure (El Paso TX: Veliz Books, 2019). A prolific translator, above and beyond her own extensive catalogue of writing (working through French, English, Spanish and Galician), Moure has been translating the work of Chus Pato for a number of years now, through five prior collections in English translation produced through BuschekBooks, Shearsman Books and Book*hug. Set with the English translation on the right and original Galician on the left, Pato’s The Face of the Quartzes offers a lyric suite of observational thought that scrape against the boundaries of perception, offering a light touch across a sequence of gestures, deep and dark and considered. “We redden the rose / using blood,” they (I say such, given the collaborative nature of translation) write, to close one particular lyric. One could describe each poem as untitled, at least in the more traditional manner, with either the opening word or opening phrase set in bold type, offered as title directly incorporated into the body of the text; reminiscent, slightly, of the late Vancouver poet Gerry Gilbert, who would offer, most notably through his infamous

Moby Jane

(Toronto ON: Coach House Press, 1987; Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2004) [see my note on the reissue here], the beginning of the book-length poem on the front cover, ending finally on the back. The body of the book was too big to contain him, after all; the titling and outside still existing within the body of the text. “Winter gave way to rain,” they write, mid-way through the collection, “and the rain gave in to itself / we await a truth of language / I was born to hear the bark of dogs [.]” There aren’t too many poets working their titling in such a manner, opening the poem immediately, and the structure is curious, offering more of an ongoingness and interconnectedness to the larger, book-length structure of this particular suite. In certain ways, one could see The Face of the Quartzes as a singular poem, simply portioned into a sequence of moments, one thought directly set against and furthering another; one that moves through concerns around language, culture, ecology, and how we both move through and interact with the world, both immediate and further beyond. There is something very large about the way Pato encompasses the minutae of her world, something captured, fortunately, for those of us who exist only in English.

Sorting books in a corner of my office, I realized I hadn’t yet gone through Galician poet Chus Pato’s latest work translated into English,

The Face of the Quartzes

, translated by Montreal poet, translator and critic Erín Moure (El Paso TX: Veliz Books, 2019). A prolific translator, above and beyond her own extensive catalogue of writing (working through French, English, Spanish and Galician), Moure has been translating the work of Chus Pato for a number of years now, through five prior collections in English translation produced through BuschekBooks, Shearsman Books and Book*hug. Set with the English translation on the right and original Galician on the left, Pato’s The Face of the Quartzes offers a lyric suite of observational thought that scrape against the boundaries of perception, offering a light touch across a sequence of gestures, deep and dark and considered. “We redden the rose / using blood,” they (I say such, given the collaborative nature of translation) write, to close one particular lyric. One could describe each poem as untitled, at least in the more traditional manner, with either the opening word or opening phrase set in bold type, offered as title directly incorporated into the body of the text; reminiscent, slightly, of the late Vancouver poet Gerry Gilbert, who would offer, most notably through his infamous

Moby Jane

(Toronto ON: Coach House Press, 1987; Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2004) [see my note on the reissue here], the beginning of the book-length poem on the front cover, ending finally on the back. The body of the book was too big to contain him, after all; the titling and outside still existing within the body of the text. “Winter gave way to rain,” they write, mid-way through the collection, “and the rain gave in to itself / we await a truth of language / I was born to hear the bark of dogs [.]” There aren’t too many poets working their titling in such a manner, opening the poem immediately, and the structure is curious, offering more of an ongoingness and interconnectedness to the larger, book-length structure of this particular suite. In certain ways, one could see The Face of the Quartzes as a singular poem, simply portioned into a sequence of moments, one thought directly set against and furthering another; one that moves through concerns around language, culture, ecology, and how we both move through and interact with the world, both immediate and further beyond. There is something very large about the way Pato encompasses the minutae of her world, something captured, fortunately, for those of us who exist only in English. The hand assembles words

my hand

that misjudges the size of the letters and width of the wall

Up above

a bullet cuts through the cry

separates the letters

the syllables

bodies tumble from the peak

The hand returns beside the others

they’re archaic

red black ochre

they agitate

like a handkerchief waving goodbye

They sleep underfoot

upside down

like bats

October 28, 2022

Kyra Simone, Palace of Rubble

COUNTY FAIR

He hopes to fly a giant helium balloon a record twenty-five miles into the earth’s atmosphere and parachute down. This is a moment worthy of fanfare. Six teenagers stand with their heads spinning. A farmer throws down his pillow. A quarry worker lets his shoulders go weak. A communist boss kneels down in the street and begs the man in the balloon to stop. The crowd calls out to him with weary arms. ‘Fly off to new realms,’ they cry. This is what life has been like. Mothers make kites out of junk-mail leaflets searching for missing people. They fly them over houses that have fallen off the market. A lemon drops from the sky into the hands of the assistant who counts new shapes. she works for the chief. She is busy in his saddle. As he thrusts her the usual afternoon earthquake, tops spin, lakes threaten to flood, postmen ring doorbells with overwhelming force. Hunters drop their shotguns and explode with dreams of mounting their wives on walls. ‘This is no Sunday in the park,’ thinks the assistant. She spent her school years studying maps of the chief’s insides, and how, as he approaches nuclear disarmament, she finds herself quietly lost, unequipped for the weapons of Europe. After twenty-five years of extraordinary bad news about childhood obesity, the balloon inflates and floats away, leaving the gondola with the man inside on the ground. In Moscow, when this sort of thing happens, it is not unusual for a man to throw his face in a barrel. Today, a bit breezy. Tonight, clear, light winds. Tomorrow, plentiful sunshine.

I’m enjoying the assembled forty-nine self-contained short fictions of Brooklyn, New York-based writer and editor Kyra Simone’s full-length debut,

Palace of Rubble

(UK: Tenement Press, 2022). Cited as a collection of short stories, each comprised of a single, occasionally extended paragraph, the description almost seems an oversimplification: these assembled bursts of prose, layering and collaging phrase upon phrase, sentence upon sentence, towards something far deeper. As the back cover offers: “Initially inspired by a photograph of one of Suddam Hussein’s demolished palaces printed on the cover of a newspaper Simone found discarded on a café table during the fall of Baghdad in 2003, Palace of Rubble has since evolved into an accumulation of texts invoked by a historical moment spanning the eras of Bush, Obama, Trump, and into the present day.” Composed of exacting lines, she writes of a sequence of destructions, consequences and disconnections, even through the book’s design, that provides an impression of installation: a tangibility that text isn’t always allowed. She writes of losses and destruction, including those that have become cyclical, even ongoing. As the story “OBITUARY FOR MRS. H.” reads, towards the end: “Remembering her youth is like standing before a crowd of G.I.s, of which there will be no survivors. The screen is blank. The bed is empty. The planet turns. It moves invisibly, fuelled by the cries of women slipping into obscurity.”

I’m enjoying the assembled forty-nine self-contained short fictions of Brooklyn, New York-based writer and editor Kyra Simone’s full-length debut,

Palace of Rubble

(UK: Tenement Press, 2022). Cited as a collection of short stories, each comprised of a single, occasionally extended paragraph, the description almost seems an oversimplification: these assembled bursts of prose, layering and collaging phrase upon phrase, sentence upon sentence, towards something far deeper. As the back cover offers: “Initially inspired by a photograph of one of Suddam Hussein’s demolished palaces printed on the cover of a newspaper Simone found discarded on a café table during the fall of Baghdad in 2003, Palace of Rubble has since evolved into an accumulation of texts invoked by a historical moment spanning the eras of Bush, Obama, Trump, and into the present day.” Composed of exacting lines, she writes of a sequence of destructions, consequences and disconnections, even through the book’s design, that provides an impression of installation: a tangibility that text isn’t always allowed. She writes of losses and destruction, including those that have become cyclical, even ongoing. As the story “OBITUARY FOR MRS. H.” reads, towards the end: “Remembering her youth is like standing before a crowd of G.I.s, of which there will be no survivors. The screen is blank. The bed is empty. The planet turns. It moves invisibly, fuelled by the cries of women slipping into obscurity.” Simultaneously dark and light, Simone’s incredibly agile fictions (interspersed with photographs by John Divola that add resonance to the book’s tone) are constructed via a concrete assortment of words, thoughts and ideas that flow, pivot and connect into each other, somehow managing to create a kind of occasional ethereality through direct means; she offers sentences that remain both separate and weave together to form an entirely new and different shape. “His death is announced Tuesday,” she writes, to open the story “STILL LIFE WITH PARROT,” “the same day he is buried in the village, the day of the great race. A day for bicycles to speed past maps of the universe sagging on walls, held up by women still trapped in Romanticism, searching other planets for signs of a second bloom. Dogs have long proved useful in detecting explosives, or to find bodies left by crime or disaster, but rarely do they find the men that are the most missed.”

October 27, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Luke Hathaway

Luke Hathaway

is a trans poet who teaches English and Creative Writing at Saint Mary’s University in Kjipuktuk/Halifax. He has been before now at some time boy and girl, bush, bird, and a mute fish in the sea. His book The Affirmations is published by Biblioasis. Both book and audio book (full of music; a co-creation with his friend the scholar/singer Daniel Cabena) are available here: http://biblioasis.com/shop/new-release/the-affirmations/

Luke Hathaway

is a trans poet who teaches English and Creative Writing at Saint Mary’s University in Kjipuktuk/Halifax. He has been before now at some time boy and girl, bush, bird, and a mute fish in the sea. His book The Affirmations is published by Biblioasis. Both book and audio book (full of music; a co-creation with his friend the scholar/singer Daniel Cabena) are available here: http://biblioasis.com/shop/new-release/the-affirmations/ 1 - How did your first book change your life?

One calls and calls and calls, & eventually ... somebody comes (or, somebodies come).

How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

It’s the work of a different poet. death/rebirth: no idle metaphor.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Poetry is my first love: breath, the heartbeat …

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I don’t know any more. Everything I’ve written in the past few years has taken me by surprise.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

There have been books that are projects, but The Affirmations was a miscellany — until it wasn’t.

Some of its poems — many of them, actually — began in music, in the desire to find new words for an old tune (the older words for which often become a point of departure — and sometimes a point of return — for the new ones).

Many, many of them (the poems) began in conversation — with a desire to say something that couldn’t be said in any other way.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love to read or speak poetry aloud, my own, or other people’s: any work I love, that is written for the ear. Increasingly I sing, too — see melody as another element of poetry, which one may prescribe or score in various ways, if one sees fit. (Though I am also deeply beguiled by the unstudied, incremental variations in pitch/rhythm/emphasis that inhere in the speaking voice, and that are also part of any reader’s/speaker’s interpretation, as they speak the words in a particular moment, with particular momentums, all reflecting/embodying the contingencies of a particular time and place, a particular audience ….)

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

No theoretical concerns. The only real question I’m trying to answer, in any given moment, is, how is this poem supposed to sound? As for “the current questions”: yikes. I think there’s no one answer.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I do think writers have a role in trying to keep the bullshit out of language; or, in trying to purge the language of the bullshit, once the bullshit has gotten in.

Beyond that ... writers are listeners, or should be; instruments through which the motion of meaning in the universe can register itself in the particular medium which is language. It has to all keep moving, though; if meaning stays written down, it gets dead. We have to read it, re-speak it, if it’s going to keep on living in the world.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Every editorial experience I’ve had has been vastly different. I can’t generalize.

I am an editor myself, and have great respect for what editors can do, the amount of time and care they can lavish on the personal expression of another: it’s really humbling.

But writers need to know how to stand their ground.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Resign yourself to the road; there’s no arriving. (That’s Steven Heighton, from a letter to me when I was about sixteen and he was an avuncular 32.)

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to libretto)? What do you see as the appeal?

Oh I love crossing boundaries! You know, with consent. It’s marvellous. Stepping across a threshold. Everything looks different on the other side. (And over here, in the libretto-world — there’s company!)