Man Martin's Blog, page 213

December 21, 2011

Apophasis December 21, Figures of Speech

Apophasis: When the other figures of speech ask me who I like best, I always say, "I love you all equally in different ways." But the truth is, apophasis has always been my favorite. From Greek apo "deny" and phani "to say," apophasis is when you say something by claiming not to say it. Marc Antony gets off a gorgeous piece of apophasis in Julius Caesar when he tells the mob, "it's good you know not you are Caesar's heirs." Other pieces of apophasis include statements like, "If I've told you once, I've told you a million times, don't exaggerate," or "I'm not talking to you." The titles of the old Underdog cartoon, I believe it was Underdog, it may have been Bullwinkle, were old-fashioned bills pasted onto walls. The last of the bills said, "post no bills."

Apophasis: When the other figures of speech ask me who I like best, I always say, "I love you all equally in different ways." But the truth is, apophasis has always been my favorite. From Greek apo "deny" and phani "to say," apophasis is when you say something by claiming not to say it. Marc Antony gets off a gorgeous piece of apophasis in Julius Caesar when he tells the mob, "it's good you know not you are Caesar's heirs." Other pieces of apophasis include statements like, "If I've told you once, I've told you a million times, don't exaggerate," or "I'm not talking to you." The titles of the old Underdog cartoon, I believe it was Underdog, it may have been Bullwinkle, were old-fashioned bills pasted onto walls. The last of the bills said, "post no bills."

Published on December 21, 2011 02:44

December 20, 2011

Aptonym December 20, Figures of Speech

After a disastrous week as a diner owner,

After a disastrous week as a diner owner,

John Crapper considers going into another line of work Aptonym: From apt "fitting" + nym, "name" is when the name of a person describes his character or occupation. This has long been used as a literary device. Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress has such appallingly obvious names as, Christian, Evangelist, Vanity, and Pliable. Dickens, too, stoops to more than one aptonym: the Cherybul brothers are cheery and Peddle and Pool are solicitors. Poe uses ironic aptonyms in "The Cask of Amontillado," Montressor – literally man+tresser, a man who ties up other men, chains up Fortunato – he is far from fortunate - in the deepest recess of a catacomb. Twentieth Century writers did not eschew aptonyms either. Vonnegut's Billy Pilgrim, who has come unstuck in time, is every bit as much a Pilgrim as Bunyan's; Faulkner's Colonel Sartoris has a sartorial air about him; and there is something small and rodenty in Updike's Rabbit Angstrom. We can't mistake Tyrone Slothrop or Humbert Humbert as anything but aptonyms even though their meaning is unclear; they are as apt onomatopoetically as Ebeneezer Scrooge or Sherlock Holmes.

The most apt of all aptonyms are purely coincidental: Bernie Madoff, William Wordsworth, Lorena Bobbitt, Thomas Crapper, Francine Prose, Gary Player, Anna Smashnova, and Anthony Weiner.

After a disastrous week as a diner owner,

After a disastrous week as a diner owner, John Crapper considers going into another line of work Aptonym: From apt "fitting" + nym, "name" is when the name of a person describes his character or occupation. This has long been used as a literary device. Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress has such appallingly obvious names as, Christian, Evangelist, Vanity, and Pliable. Dickens, too, stoops to more than one aptonym: the Cherybul brothers are cheery and Peddle and Pool are solicitors. Poe uses ironic aptonyms in "The Cask of Amontillado," Montressor – literally man+tresser, a man who ties up other men, chains up Fortunato – he is far from fortunate - in the deepest recess of a catacomb. Twentieth Century writers did not eschew aptonyms either. Vonnegut's Billy Pilgrim, who has come unstuck in time, is every bit as much a Pilgrim as Bunyan's; Faulkner's Colonel Sartoris has a sartorial air about him; and there is something small and rodenty in Updike's Rabbit Angstrom. We can't mistake Tyrone Slothrop or Humbert Humbert as anything but aptonyms even though their meaning is unclear; they are as apt onomatopoetically as Ebeneezer Scrooge or Sherlock Holmes.

The most apt of all aptonyms are purely coincidental: Bernie Madoff, William Wordsworth, Lorena Bobbitt, Thomas Crapper, Francine Prose, Gary Player, Anna Smashnova, and Anthony Weiner.

Published on December 20, 2011 02:54

December 19, 2011

Circumlocution December 19, Figures of Speech

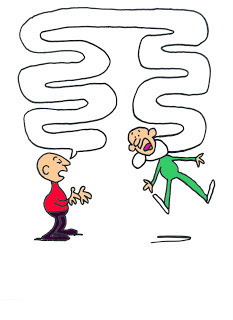

Circumlocution: From the Latin circum- "around" and -loquy "speech," literally to talk in circles. Circumlocution is something to be sedulously avoided except by professional humorists, politicians, and husbands who have forgotten anniversaries. It's hard to find good examples of circumlocution because so often what passes is just plain old wordiness. True circumlocution creates a dizzy sensation as if you were following a toy boat in a whirlpool. Schultz' Linus gets off a masterful piece of circumlocution when he tells Charlie Brown, "That's a terrible feeling to have the need of having the feeling of having..."

Circumlocution: From the Latin circum- "around" and -loquy "speech," literally to talk in circles. Circumlocution is something to be sedulously avoided except by professional humorists, politicians, and husbands who have forgotten anniversaries. It's hard to find good examples of circumlocution because so often what passes is just plain old wordiness. True circumlocution creates a dizzy sensation as if you were following a toy boat in a whirlpool. Schultz' Linus gets off a masterful piece of circumlocution when he tells Charlie Brown, "That's a terrible feeling to have the need of having the feeling of having..."

Published on December 19, 2011 02:18

December 18, 2011

Tautology December 18, Figures of Speech

A panel of experts convened to explain

A panel of experts convened to explain

why "UP" is higher than "DOWN" Tautology: If paradox had a precise antonym, it might be tautology. From the Greek tautos + logos, "to say the same thing." In The Wizard of Oz, when the Scarecrow sings he'd like to know "why the ocean is near the shore," he's uttered a tautology. When Calvin Coolidge opined that unemployment results when large numbers of people are out of work, it was a tautology. This is somewhat different than a redundancy in that instead of mere repetition, a tautology professes to be a kind of logical proof.

A panel of experts convened to explain

A panel of experts convened to explain why "UP" is higher than "DOWN" Tautology: If paradox had a precise antonym, it might be tautology. From the Greek tautos + logos, "to say the same thing." In The Wizard of Oz, when the Scarecrow sings he'd like to know "why the ocean is near the shore," he's uttered a tautology. When Calvin Coolidge opined that unemployment results when large numbers of people are out of work, it was a tautology. This is somewhat different than a redundancy in that instead of mere repetition, a tautology professes to be a kind of logical proof.

Published on December 18, 2011 02:29

December 17, 2011

Hyperbole December 17, Figures of Speech

Hyperbole: from the Greek, huperbole, "excess," oddly unrelated to hyperbola, which also from Greek, huperballein, "to throw beyond." A wild exaggeration such as that hoary old chestnut, "I'm so hungry, I could eat a horse." Jack Benny would say that, and after a Benny-esque pause for consideration, admit, "well, a small horse." The lesson with hyperbole is that it's not very effective all by itself but can be if it's combined with another figure of speech, for example, a pun, "Your mother is so big that when she sits around the house, she really sits around the house," or a paradox, "That river was so wide, it only had one bank," or go to excruciatingly accurate detail as Snoopy does, writing, "His love for her was deeper than the Mariana Trench, which is the deepest spot on earth, over 36 thousand feet."

Hyperbole: from the Greek, huperbole, "excess," oddly unrelated to hyperbola, which also from Greek, huperballein, "to throw beyond." A wild exaggeration such as that hoary old chestnut, "I'm so hungry, I could eat a horse." Jack Benny would say that, and after a Benny-esque pause for consideration, admit, "well, a small horse." The lesson with hyperbole is that it's not very effective all by itself but can be if it's combined with another figure of speech, for example, a pun, "Your mother is so big that when she sits around the house, she really sits around the house," or a paradox, "That river was so wide, it only had one bank," or go to excruciatingly accurate detail as Snoopy does, writing, "His love for her was deeper than the Mariana Trench, which is the deepest spot on earth, over 36 thousand feet."

Published on December 17, 2011 03:09

December 16, 2011

Paradox December 16, Figures of Speech

One pair of docs examines anotherParadox from the Greek para "beyond" and dox "opinion. A seemingly contradictory or impossible statement. The best paradoxes are not nonsense, but just a twisted presentation of the truth. "It is so late," Lord Capulet tells a party-goer, "that we may call it early by and by." Sometimes paradox is used to highlight a transcendent truth, as in Jesus' claim that we must lose our lives in order to gain them.

One pair of docs examines anotherParadox from the Greek para "beyond" and dox "opinion. A seemingly contradictory or impossible statement. The best paradoxes are not nonsense, but just a twisted presentation of the truth. "It is so late," Lord Capulet tells a party-goer, "that we may call it early by and by." Sometimes paradox is used to highlight a transcendent truth, as in Jesus' claim that we must lose our lives in order to gain them.One last paradox is this seemingly logical series of statements:

1. Crackers are better than nothing.

2. Ice cream is better than crackers.

3. Nothing is better than ice cream.

Published on December 16, 2011 03:03

December 15, 2011

Chiasmus December 15, Figures of Speech

You can take the boy

You can take the boyout of the country,

but you can't take the

country out of the boy.Chiasmus: Literally a "crossing," is one of those words that's easier to give an example of than to define. An example would be Mae West's, "It's not the men in your life that count, it's the life in your men." The definition is something like a figure of speech in which the order of two terms in the first part is reversed in the second part." See what I mean?

Chiasmus is so fun because it can be put to so many rhetorical uses. It can be stirring as in Kennedy's "ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country," or Frederick Douglass' "you have seen how a man became a slave, now you will see how a slave became a man." It can be defiant and curmudgeonly like Robert Frost's, "Keep off each other and keep each other off." Or plain silly like "I'd rather have a bottle in front of me than a frontal lobotomy."

The last is not only chiasmus, but metathesis, because specific sounds are transposed instead of whole words. Another example of combining chiasmus and metathesis is the answer to this riddle:

Q: "What's the difference between a rooster and a lawyer?"

A: "Well, a rooster clucks defiance, and a lawyer..."

Published on December 15, 2011 03:12

December 14, 2011

Oxymoron December 14, Figures of Speech

Organized

OrganizedReligionOxymoron: A paradoxical or self-contradictory phrase, such as "Biggie Smalls," "pretty ugly," "Icy Hot," or "organized religion." Some words are oxymoronic in themselves: preposterous, coming from the roots pre and post, means "before after." Piano forte, the original name for piano, means "soft, strong." Sophomore means "wise-fool' (if you taught them, you'd see why) and oxymoron itself: oxy-, meaning "sharp" or "biting" and moron, meaning "dull."

Published on December 14, 2011 02:34

December 13, 2011

Ellipsis December 13, Figure of Speech

Ellipsis from a Greek word meaning "omission" or "falling short" is leaving something out, this is noted in punctuation by three consecutive periods (...) whereas the dash signifies an interruption. But an ellipsis can also be accomplished without the marks. "Nice day," is ellipsis for "Have a nice day," and "Can do," is ellipsis for... Well, you get the idea.

I have more to say on the topic, but in the spirit of ellipsis, I won't.

...

I have more to say on the topic, but in the spirit of ellipsis, I won't.

...

Published on December 13, 2011 02:35

December 12, 2011

Malapropism December 12, Figures of Speech

Malapropism, the mistaken substitution of a word for one with a similar sound but different meaning. Mrs. Malaprop (Latin for "not appropriate") was a character in Sheridan's play, The Rivals, who was fond of saying such things as "He's the very pineapple of kindness." Most malapropisms are unintentional, the result of faulty understanding. I once worked under a principal who got on the intercom to warn students against "conjugating in the halls." Norman Lear's Archie Bunker was the Twentieth Century master of malapropism, extolling Shriner's Conventions as a way to "break up the monogamy," and quoting scripture that "thou shalt not bear falsies to thy neighbor."

Published on December 12, 2011 02:28