Kim Messier's Blog

August 17, 2019

This Blog Has Moved

As of August 2019 this blog has moved to a new website and no more new content will be posted on this Goodreads blog platform.

Please find all of the blogs you were used to reading here now at Kim & Pat Messier's Blog.

May 27, 2019

He Wants to be Called William Goodluck

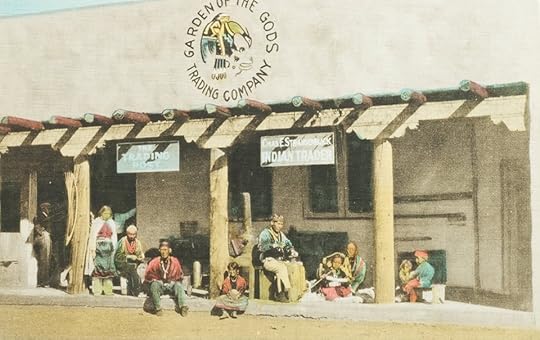

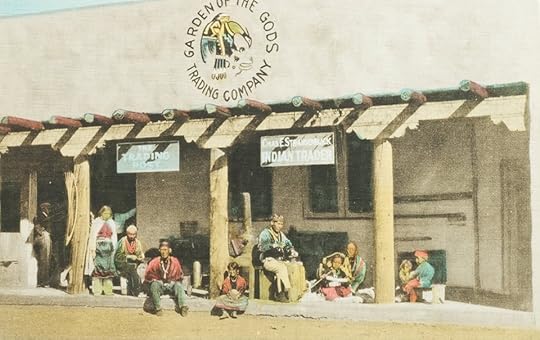

The cover of our newest release, Garden of the Gods Trading Post, shows Navajo silversmith William Goodluck and members of his family sitting on the porch of the Trading Post in 1929.

Left to right, William Goodluck, son Herbert, daughter Charlotte behind a baby in a cradle board, wife Yekanasbah and daughter Elizabeth.

Left to right, William Goodluck, son Herbert, daughter Charlotte behind a baby in a cradle board, wife Yekanasbah and daughter Elizabeth.

These six silver bracelets were made between 1924 and 1929 at “The Indian” trading post by the Native American silversmiths who worked for Charles Strausenback. The bracelets are hallmarked SOLID SILVER HAND MADE AT THE “INDIAN” GARDEN OF THE GODS-COLO. The top bracelet is similar in design to one that William Goodluck wore in the photo above, so it is likely that he made that piece.

These six silver bracelets were made between 1924 and 1929 at “The Indian” trading post by the Native American silversmiths who worked for Charles Strausenback. The bracelets are hallmarked SOLID SILVER HAND MADE AT THE “INDIAN” GARDEN OF THE GODS-COLO. The top bracelet is similar in design to one that William Goodluck wore in the photo above, so it is likely that he made that piece. This photograph was taken inside “The Indian” trading post, where Goodluck is shown working silver while his wife, Yekanasbah, weaves at her loom and their children spin and card the wool.

This photograph was taken inside “The Indian” trading post, where Goodluck is shown working silver while his wife, Yekanasbah, weaves at her loom and their children spin and card the wool.

The porch of Garden of the Gods Trading Post 1929, Porfilia and Severo Tafoya (Santa Clara Pueblo) are far left, Hosteen Goodluck sits on the porch, William Goodluck sits at a stump, with his wife and children near him.

Photo of William Goodluck at the anvil on the porch of Garden of the Gods Trading Post published in the Denver Post June 16, 1935. Courtesy Garden of the Gods Trading Post.

A biography of William’s father Hosteen Goodluck can be found at the bottom of the blog To Be (Hosteen) or Not To Be, That is the Question.

From left to right, Herbert, Elizabeth and Charlotte—the children of William and Yekanasbah Goodluck—stand outside the ramada where their father made silver at “The Indian” trading post. On the ground are spoons and bracelets in progress and the silversmithing tools that William used. This c. 1925 photograph was taken by Charles Strausenback for his series of advertising postcards.

April 7, 2019

Coming Soon…Redux

...the marketing has kicked into gear. It’s an exciting time, and Arcadia Publishing has already sent more promotional material than we received from our two previous publishers.

The first package to arrive without warning was full of posters, fliers, bookmarks, and Autographed Copy stickers.

Followed shortly by our first six comp copies and a stack of postcards, received a full two months prior to pub date. The most gratifying time for any author is the day their efforts are rewarded with holding the first copy of their finished book. And so it is for us, we are very pleased with how the book turned out, and especially delighted with the cover as it honors Navajo silversmith William Goodluck and his family.

Equally exciting is our inaugural signing event in June with Garden of the Gods Trading Post to commemorate the trading post’s 90th anniversary; and we have begun coordinating the event with management.

The Images of America series is published in black-and-white so keep an eye out for future blogs focusing on the more colorful aspects of Charles Strausenback’s story including his art work, the murals on the walls of the Trading Post and the jewelry made by the Native American silversmiths who worked there.

We look forward to seeing you at one of the signing events in the works for the coming months.

December 15, 2018

To Be (Hosteen), or Not To Be, That is the Question…

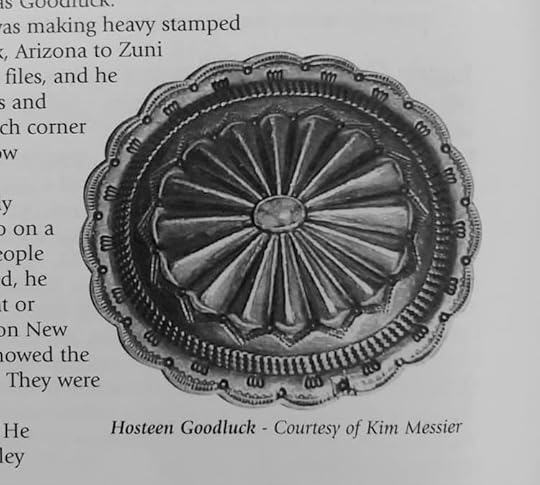

Concho attributed to Hosteen Goodluck as it appears on page 15 of Reassessing Hallmarks.

Concho attributed to Hosteen Goodluck as it appears on page 15 of Reassessing Hallmarks.

Concho belts, numbers 59 and 61, attributed to Hosteen Goodluck by C.G. Wallace in the 1975 auction catalog.

Concho belts, numbers 59 and 61, attributed to Hosteen Goodluck by C.G. Wallace in the 1975 auction catalog. Numbers 387 and 389, attributed to Hosteen Goodluck by C.G. Wallace in the 1975 auction catalog.

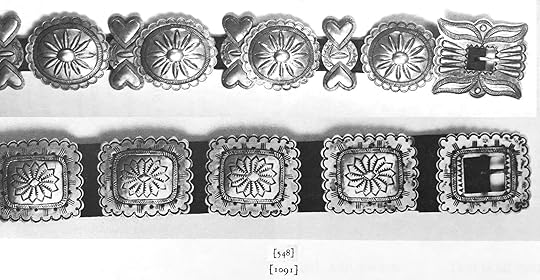

Numbers 387 and 389, attributed to Hosteen Goodluck by C.G. Wallace in the 1975 auction catalog.  Concho belts 548 and 1091 attributed to Hosteen Goodluck by C.G. Wallace in the 1975 auction catalog.

Concho belts 548 and 1091 attributed to Hosteen Goodluck by C.G. Wallace in the 1975 auction catalog.

From the Oakland Tribune June 24, 1937.

From the Oakland Tribune June 24, 1937. Close up of Hosteen Goodluck on the porch of Garden of the Gods Trading Post.

Close up of Hosteen Goodluck on the porch of Garden of the Gods Trading Post. Larry Frank published this 1904 image in Indian Silver Jewelry of the Southwest, 1868-1930 on page 28, but was unaware the subject was silversmith Hosteen Goodluck. The silver squash blossom necklace and concho belt he wears in this image serves as excellent proof of his silversmithing skills.

Larry Frank published this 1904 image in Indian Silver Jewelry of the Southwest, 1868-1930 on page 28, but was unaware the subject was silversmith Hosteen Goodluck. The silver squash blossom necklace and concho belt he wears in this image serves as excellent proof of his silversmithing skills.

Porch of Garden of the Gods Trading Post ca. 1929, Porfilia and Severo Tafoya (Santa Clara Pueblo) are far left, Hosteen Goodluck sits on the porch, William Goodluck sits at a stump, with his wife and children around him.

July 20, 2018

Navajo Overlay Artist Willie Yazzie

After the success of the overlay designs made at the Hopi Guild many other silversmiths and shops incorporated overlay in their designs (see Overlay is Not Always Hopi Made). Navajo trader Dean Kirk opened his own trading post at Manuelito, New Mexico (between Gallup and the Arizona border) before January 1941. The silver work made in Dean’s shop was typically Navajo tourist type designs and hallmarked UITA22 (under the auspices of the United Indian Traders Association) until about 1951. That’s when Kirk designed a series of overlay pins to be made by Navajo smiths in his employ incorporating Hohokam and Mimbres designs. These designs proved to be very popular, as a 1958 newspaper advertisement for Enchanted Mesa in Albuquerque promoted “Dean Kirk’s Navajo Overlay Silver”. The overlay pieces made at Kirk’s shop were rarely hallmarked.

Overlay pin featuring Hohokam pottery design made by Navajo silversmiths for trader Dean Kirk, 1950s.

However, one of the Navajo silversmiths who worked for Dean Kirk was Willie Yazzie, he made his own hallmark and used it on pieces he made in Kirk’s shop.

Willie Yazzie’s gourd dipper hallmark.

Much of the following information was relayed to Alan Ferg (archivist and archaeologist at Arizona State Museum) by William P. (Willie) Yazzie, Jr, in February 2018. Ferg’s investigation of an overlay belt buckle in his possession, lacking a hallmark, has led to previously unrecorded information about Willie Yazzie, as well as the identification of an additional hallmark used by the artist.

Willie Yazzie made the overlay bolo at Dean Kirk’s shop, it includes a deer and stylized Hopi designs; a small piece of turquoise is inlaid flush in the deer’s body. His Navajo wedding basket pin incorporates a small piece of copper to symbolize the red band in traditional wedding baskets.

Hallmarked belt buckle by Willie Yazzie, 1950s, with appliquéd Pueblo bird design utilizes more background, or negative space, than design.

Back of the Pueblo bird belt buckle above showing Willie Yazzie’s hallmark.

According to Social Security records, Willie A. Yazzie was born at Chinle, Arizona in 1928. His son says he learned silverwork at Dean Kirk’s trading post in Manuelito in the early 1950s, and created his touchmark (or hallmark) no later than 1960, and after that time his pieces made at Dean Kirk’s would have included his gourd dipper hallmark. His designs often incorporated animal figures such as roadrunners or Navajo designs including Yeis and Father Sky. He never added “tamp work,” or a textured pattern to the background designs.

Bracelet with appliqué swirl design made by Navajo silversmith Willie Yazzie for trader Dean Kirk.

In 1960 Ansel Hall, concessionaire at Mesa Verde National Park, was looking for a silversmith to demonstrate at the park during the summers months, Dean Kirk recommended Willie Yazzie and he was hired by Hall. Willie worked at Mesa Verde in the summers from 1960 to 1983, except for 1965 when he was sick. Yazzie created a special hallmark to denote pieces he made at Mesa Verde. The mark depicts Square Tower House, a ruin within the park, and was included with his gourd dipper mark during the summers of 1960-1964 and 1966-1983.

This salt spoon was made by Willie Yazzie while he worked at Mesa Verde National Park during the summers of 1960-1983, as indicated by the hallmarks on the back. Courtesy Bille Hougart.

Hallmarks on the back of the salt spoon above by Willie Yazzie includes his medicine dipper touchmark and the Square Tower House mark for work made at Mesa Verde National Park. Courtesy Bille Hougart.

Another image of Willie Yazzie’s gourd dipper hallmark with the Square Tower House mark for work made at Mesa Verde National Park. Courtesy Bille Hougart.

Willie A. Yazzie died in 1999, but his family, including his widow, daughter and Willie Jr continue the tradition of Willie’s overlay work. Willie Jr said that his sister has most of their father’s tools and stamps, and that she still uses the gourd dipper mark. Willie uses mostly his initials as his hallmark, but doesn’t do much silverwork anymore, he is retired from the National Park Service where he was a ranger at Canyon de Chelly. Willie, who lives in Chinle, said his sons do a little silversmithing, but that they are busy and don’t have much time for it.

Overlay pin by Willie Yazzie. Courtesy Karen Leblanc.

May 28, 2018

John Silver Never Worked at Vaughn’s

To be clear, Navajo silversmith John Silver, the owner of the star hallmark found on many silver and copper butterflies (and other exceptional jewelry) never worked for Reese Vaughn at any of his locations. Our research has found no connection between John Silver and Vaughn’s Indian Store. That is not to imply that further research, or as yet undiscovered resources, may one day indicate otherwise.

The assumption that John Silver worked at Vaughn's Indian Store seems to have originated in a design decision in Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry: Artists, Traders, Guilds, and the Government that we never imagined would result in any confusion.

In March 2008, after attending the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Pat and I unexpectedly ended the debate about whether to have the jewelry in our next project professionally photographed, or take the photos ourselves, when we stopped at a Phoenix camera shop to obtain a static-free lint brush and instead walked out with a Nikon digital camera and a home studio set-up.

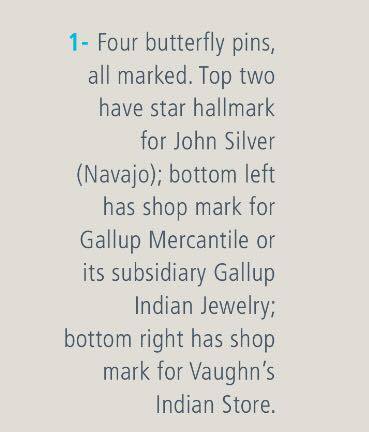

During our initial efforts to photograph our own collection, with only a hazy vision of the final publication, we grouped four hallmarked butterfly pins into a single photograph. It turned out to be a visually appealing image, but the hallmarks on the pieces were diverse; two were signed with the same star hallmark, one marked with a knifewing figure, and another signed VAUGHN’S. At the time of the photograph only the Vaughn’s shop mark had a clear attribution, we still needed to research the other two marks.

The star mark on the silver and copper butterflies, a five-pointed star with a raised circle in the center, had given us grief from the first time we saw it.

We had trouble accepting the general consensus that the mark belonged to Harold Koruh (Hopi) or to Dan Simplicio (Zuni). Neither attribution felt right as the work was nothing like we would expect from Koruh, a Hopi who learned in the GI Bill classes under Paul Saufkie; nor Simplicio who most often worked with stone settings. The Koruh attribution sprang from the star hallmark illustrated in Margaret Wright’s Hopi Silver.

And the Simplicio attribution from Barton Wright’s Hallmarks of the Southwest.

Though neither drawing was a match to the star hallmark in question, there wasn’t any evidence that it belonged to any other silversmith.

After some time, and discussions with Russell Hartman—then Collections Manager for the Anthropology Department at California Academy of Sciences—we discovered the star hallmark on those butterflies had been documented in the Elkus Collection as that of John Silver (Navajo), found at this link Collections Database listing for CAS 0370-1646. The Elkus Collection, as discussed in previous blogs, is one of the most thoroughly documented collections of Indian art ever assembled.

Supporting our attribution of John Silver for the star mark on butterflies were actual examples of Dan Simplicio’s hallmark, only available after the proliferation of digital cameras, which confirmed his mark to be very similar, yet different from the one we had.

Finally, the last hallmark in our grouping of four butterflies, the knifewing with GALLUP in the center, was identified as that of Gallup Mercantile with the help of Jay Evetts.

After lengthy research it finally came time to write the manuscript. We had enough information on Vaughn’s Indian Store to not only include the shop mark, but also a couple of paragraphs about the owner Reese Vaughn and a few of the silversmiths who worked there. We had two photographs that each contained different versions of the Vaughn’s shop mark, so it felt natural to place them with the text. Unfortunately, this didn’t allow the two marks not associated with Vaughn’s to speak for themselves.

Here's the actual page from the book as the publisher designed it:

With the caption:

As you can see, we never actually wrote anywhere that John Silver worked at Vaughn's. But we now see that having his hallmark on the same page devoted to the history of Vaughn’s Indian Store implied that he did. We regret the unfortunate misperception that this has caused.

As for John Silver, he has been challenging to pin down. It is possible that he could have also gone by the names John Etcitty, or John/Johnny Silversmith, who worked at Zion National Park and Garden of the Gods Trading Post. However, listed in the appendix of Navajo silversmiths working in 1938 in John Adair’s Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths, are two John Silversmiths and one John Silver. Unfortunately it may be impossible to ever know exactly which of these may have used the star hallmark.

February 4, 2018

Endnotes – Like Rearranging Deck Chairs on the Titanic

Chicago Manual of Style 16th edition

The mind-boggling contents of the chapter, not for the faint of heart, are listed here 14: Notes and Bibliography.

We have been aware for some time that there was an oversight in Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry, which was the exclusion of footnotes or endnotes. One particularly muddled Amazon review emphasized the necessity of citing sources and directing readers to our research. Most often we made the path of our logical conclusions clear in the text, but admittedly, there were a few instances where our logic did not shine through as we had expected. In these instances, notes would have resolved the reader’s confusion, and it might not have looked so much like we pulled one or two attributions from thin air.

However, a very conscious decision was made from the beginning of the hallmark book that we would not annotate. Our philosophy, even before we chose a publisher, was that we were writing a popular book, not a scholarly or academic tome. Mindful of the readers who could have been discouraged or distracted by notes we tried instead to make our sources clear in the text. In at least two instances we failed. But perhaps it was also the particular subject matter of the hallmark book that caused controversy among a handful of readers, as we have never experienced any criticism for failing to annotate Hopi & Pueblo Tiles: An Illustrated History.

Our oversight, though, was crystalized years later, after speaking with other published authors. One historian friend explained, “But notes are where your credibility lies.” Thus, the decision was made, from the start, to annotate our current project. The subject matter is more about history and anthropology and less about Indian art, and it is the most challenging project we have ever undertaken. Consequently we are hypersensitive to get it right.

So, from one nonfiction writer to another, may I suggest you take the time to properly format your endnotes at the time of creation. Invest in the latest edition of The Chicago Manual of Style and get the notes written properly the first time. Really, there’s little more mind-numbing than having to go back and chase down a source for the page number or URL. And I can guarantee that you will hate, with every fiber of your being, having to double-check and re-write or re-format the notes in your entire manuscript.

October 19, 2017

Navajo Arts and Crafts Guild

The foundation for an arts and crafts guild for the Navajo tribe was laid in 1939 when a crafts program was established at Fort Wingate, New Mexico with assistance from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Ambrose Roanhorse was selected as director of the project, the purpose of which was to provide employment for those who had learned silversmithing at federal Indian schools as well as for established silversmiths in the vicinity. Roanhorse distributed supplies on the reservation and collected finished work to be sold through the guild. By 1940, with the help of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board (IACB), the program was established as the Navajo Arts and Crafts Guild (NACG), though it was not formally chartered by the tribal council until 1941, at which time it moved to Window Rock.

Bolo, buckle and cast pins made for the Navajo Guild 1940s-1950s

Silver was produced either at the guild shop, in the homes of the craftsmen, or at community workshops established on the reservation. Materials and supplies were issued only to craftsmen who could meet the standards and requirements for quality established by the guild. These standards were similar to the stringent standards set in 1938 by the Indian Arts and Crafts Board silver stamping program (which meant no power-driven machinery nor sheet silver could be used in the production)*—though craftsmen having their own materials, supplies, and workshops could offer their products for sale to the guild. Full-time managers were hired, and one of the first was Anglo anthropologist John Adair.

Two bracelets made for the Navajo Guild 1940s-1950s

In his 1944 book The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths, Adair wrote,

The purpose of the guild is to increase the tribal income from the sale of arts and crafts by promotion of fine handicrafts which will sell in quality stores in the East, Middle West, and Southwest. The tourist market is purposely avoided, as it does not yield as high a return per man hour as the more exclusive stores and shops.

The type of silverware that the guild promotes is similar to that which has been at the Santa Fe, Albuquerque, and Fort Wingate Indian schools; a revival of the old simple types of jewelry, without sets for the most part. Emphasis is placed on cast work. The guild also handles vegetable-dyed rugs and some aniline-dyed rugs of similar pattern and excellent workmanship. (pg 209)

Two of the "quality stores" who purchased from the Navajo Guild in 1947 were Marshall Field's and Tiffany's.

In 1943 the United Indian Traders Association (UITA) complained that the guild was in direct competition with the traders. The controversy continued in 1946 during the Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial when Arthur Woodward, one of the judges of the silversmithing division, was shocked to learn that the craftsmen who worked with the NACG were not permitted to submit their work for competition. The Ceremonial board contended the Navajo Guild was government subsidized and should be disqualified; Woodward refuted their claim in an open letter published in the Gallup Independent newspaper, saying that guild craftsmen were in business for themselves and questioned whether the Gallup traders feared their silver would fare poorly in competition with the silver made by guild craftsmen.

Despite complaints from the reservation traders, the guild continued to succeed and grow; Ned Hatathli was named the first Navajo manager in 1951. In 1964 the guild opened its first branch at Cameron, Arizona, under the management of Kenneth Begay. By the late 1960s the NACG had added branches at Betatakin (Navajo National Monument), Kayenta, Teec Nos Pos, and Chinle.

In 1971 the guild became the Navajo Arts and Crafts Enterprise (NACE) and continues to be the only Navajo Nation–owned business engaged in the purchase and sale of Navajo-made arts and crafts, http://www.gonavajo.com/.

The title “Navajo Arts and Crafts Guild” and its Horned Moon logo were registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in 1943. Items made through the NACG were hallmarked with the Horned Moon logo and often included the word NAVAJO. Sometimes individual silversmiths’ hallmarks are also found on these pieces.

* For discussions of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board silver stamping program that ran from 1938-1943 see Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry by Pat & Kim Messier, Native American and Southwestern Silver Hallmarks, Third Edition by Bille Hougart, and The Native American Curio Trade In New Mexico by Jonathan Batkin. IACB numbers were assigned April 1938, but the Navajo Guild at Fort Wingate was assigned US NAVAJO 70 in March 1940.

July 16, 2017

The Rediscovery of a “Lost” Hallmark

Every once in a while a hallmark from decades ago surfaces that has no recorded identification or attribution. When confronted with the task of identifying these challenges my co-author Pat Messier and I delve into our research and memories to try to find the proper identification. The task can often be mind-numbing and impossible to solve, but sometimes it’s a relatively easy assignment.

For example, on Facebook recently American Indian art dealer Karen Leblanc posted images of this old hand hammered Navajo silver tray.

Along with an image of the hallmark on the back.

Even though the hallmark was not stamped cleanly and is a little vague on one side, it set off bells in my head. I am intimately familiar with this Navajo Yei figure as it also appears as a design element on a 1930s Navajo ashtray we own.

We purchased the ashtray because of those Yei designs which formed the basis of a hunch we had about its origin, but didn’t know if we would find the corroborating evidence to confirm it.

During our research on the United Indian Traders Association for Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry we encountered the document below online at Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester.

This was our first indication that Berton I. Staples, trader at Coolidge, New Mexico in the 1930s, may have used a hallmark on the silver made by his Navajo employees. It was very common that traders who employed Indian silversmiths would have their business logo made into shop marks for identifying the silver made in their shops. But we had not seen this figure used as an actual hallmark, only as a design element.

Back when we bought our ashtray we ran through our references and found mention in the Elkus Collection catalog, published by the California Academy of Sciences, of this Yei design used on flatware made by two of Staples' Navajo silversmiths, and commissioned by the Elkus’s.

An image of a place setting of the flatware is included.

Below is a close-up of the design.

Having been used as a design element and business logo does not guarantee that this figure was used as a hallmark. That is, not until Ms. Leblanc posted the images of her silver tray.

Pat and I set forth on a mission to prove our hunch. Since the construction techniques and stamped designs of Karen's tray confirmed a creation date in the 1930s (as did our ashtray with the Yei figure design), we knew we were on the right track. We reviewed our research again and double checked our references, to try to prove, or to disprove, our theory while also considering who else during that time could have used this Yei figure other than Staples. We determined it was unlikely that Charlie and Madge Newcomb, who purchased Staples’ trading post after his death in 1938, would have continued to use someone else’s business logo in their own business. So we finally concluded that the hallmark did, in fact, belong to Berton I. Staples. This was one of our easiest attributions to date!

It could have been even easier if we had just gone to the California Academy of Sciences online database for the Elkus Collection first. Between 1922 and 1965 Ruth and Charles deYoung Elkus of San Francisco assembled an important collection of nearly 1700 examples of historic and contemporary Native American art, and they documented it thoroughly at the time of acquisition. California Academy of Sciences has made the collection available in an online database for decades, we used it to research Hopi & Pueblo Tiles: An Illustrated History. Anyway, there we would have found this entry, Navajo Match Box Holder which includes in its description this phrase "Image of Navajo horned moon (hallmark of Bert I. Staples' Crafts del Navajo Shop, Coolidge, NM and symbol used on Elkus family silverware.)" The proof of the ownership of this hallmark doesn't get any better than this (even though the depiction is actually that of a Yei, and not the Horned Moon).

So, attribution in hand we informed Ms. Leblanc that in our opinion her tray was made by silversmiths who worked for Berton Staples at his Crafts del Navajo trading post in the 1930s. It was requested that she send an image of the mark to Bille Hougart, author of Native American and Southwestern Silver Hallmarks, for his consideration of including it in his hallmark database, and to be added to the next revision of his identification guide. In the meantime we sent our supporting evidence backing up our attribution to him. And our excitement at having rediscovered this hallmark was doubled by Mr. Hougart's agreement of the attribution.

It should be noted that Barton Wright attributed the United Indian Traders Association hallmark UITA 3 to Berton Staples in his Second Edition of Hallmarks of the Southwest. Even though Barton's listing in the Shop Mark section is labeled as No Records: Preliminary Listing it has been taken as gospel and perpetuated across the Internet. But it is impossible that any UITA mark belonged to Staples since he passed away in 1938, and the UITA silver stamping program was initiated in 1946. We think Barton assumed that the number assigned to Staples for the Indian Arts and Craft Board (IACB) silver stamping program in 1938, US NAVAJO 3, would have been carried over to the UITA program. But Barton must have been unaware at the time that Staples had passed before the UITA program was originated.

We agree with Bille Hougart's attribution of UITA 3 to either Toadlena Trading Post or Two Grey Hills Trading Post.

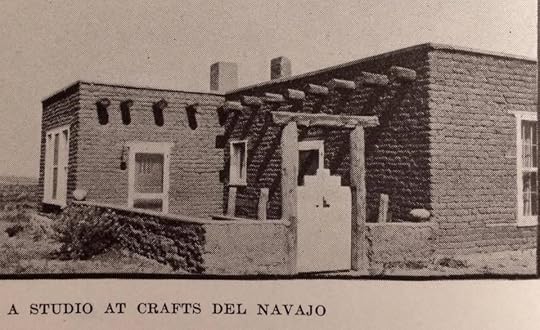

Berton I. Staples

Berton Isaac Staples was born 1873 in Vermont and moved to New Mexico in 1916. After working for various merchants in the area around Thoreau he went into business for himself and in 1925 opened Crafts del Navajo, a trading post at Coolidge, New Mexico on Route 66 east of Gallup. The rambling structure he built there served as a trading post, museum, guest lodge and post office.

Image from March 1931 issue of School Arts Magazine.

Staples was passionate about Navajo art. He, "became devoted to the Navajo and started his own collection of their handicrafts which in time became generally recognized as the finest private collection of Navajo handicrafts in the United States." He served as president of the United Indian Traders Association from its inception in 1931 until his death. He was appointed to the committee that helped organize the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, and he served on the board for the Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial. Staples died October 9, 1938 in a car crash between Thoreau and Crownpoint, New Mexico.*

Navajo silver jewelry made at Crafts del Navajo, and a silversmith with his family. Image from March 1931 issue of School Arts Magazine.

*The biographical information about Staples was taken from the article, "Berton I. Staples Killed in Car Wreck; Rated Authority on Indian Arts and Crafts," published in Southwest Tourist News, October 13, 1938.

February 15, 2017

The Use of the Swastika Symbol in American Indian Art

Copper bookends by Morris Robinson (Hopi). The swastika design indicates they were made before 1940.

One of the most popular designs incorporated into American Indian art during the tourist era— approximately 1890 to 1940—was the swastika symbol, common to most indigenous peoples the world over and used throughout time. There is historical precedence of the use of swastika-like designs by North American native peoples, who usually viewed the symbol as a representation of the four directions; for instance the Navajo use a design often referred to as “whirling logs” in sandpaintings,

and the Hopi paint a four-armed pinwheel design on rattles symbolizing the migrations of the clans across the continent.

Hopi rattle with four-armed migration symbol

A great deal of interest was generated in the swastika symbol around the turn of the twentieth century and was fueled in part by an 1894 report of the U.S. National Museum written by Thomas Wilson entitled The Swastika: The Earliest Known Symbol, and Its Migrations. The symbol became a very popular design element representing good luck and was prevalent in period architecture, advertising, jewelry, and on good luck tokens. The Arizona Highway Department even used it as part of their emblem. Because of its popularity, traders encouraged Indian artists to use it on their crafts made for sale to the tourist trade. The design often appeared on silverwork, textiles, pottery, and basketry.

Zia pottery tile ca. 1930s with painted swastika design.

Beginning in 1934 East Coast dealers of Indian goods urged reservation traders to discourage native craftspeople from using the swastika as a design element because of its adoption by the German Nazi Party. When the Fred Harvey Company, a major dealer in Indian arts, issued a mail order catalog in 1938 the symbol had been discontinued from their products.

Fred Harvey mail order catalog published 1938

Popularity of the design waned, eventually resulting in a proclamation signed on February 28, 1940, in Tucson by representatives from the Hopi, Navajo, Apache, and Tohono O’odham (formerly Papago) tribes, renouncing and banning the use of the swastika on their artwork. The text of this parchment document read:

Because the above ornament which has been a symbol of friendship among our forefathers for many centuries has been desecrated recently by another nation of peoples,

Therefore it is resolved that henceforth from this date on and forever more our tribes renounce the use of the emblem commonly known today as the swastika or fylfot on our blankets, baskets, art objects, sandpaintings and clothing.

Postcard showing Indians from various southwest tribes signing a declaration that they would not use the swastika symbol on their artwork after February 28, 1940.

It is likely that the signing of the document by members of southwest tribes was a form of public relations arranged by area traders to distance Indian handicrafts from the atrocities occurring overseas. Nevertheless, the inclusion of this symbol on Indian artwork was discontinued at that time.

There was a small resurgence of the use of the symbol in the 1970s, especially by some Anglo silversmiths who made jewelry to look like historic, or pawn, Navajo jewelry. Presently, Native artists occasionally attempt to reintroduce the symbol into their artwork, but it has been met with resistance.

Six bracelets, c. 1925, marked SOLID SILVER HAND MADE AT THE “INDIAN” GARDEN OF THE GODS–COLO, most include a form of the swastika design.

The foregoing was adapted from our books Hopi & Pueblo Tiles: An Illustrated History and Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry: Artists, Traders, Guilds, and the Government.