Kim Messier's Blog, page 3

December 20, 2014

Reassessing Native American Hallmark Books

Sometimes it’s important to take a step back and look at the events preceding a particular situation to understand how it came about. For hallmarks used by deceased American Indian silversmiths, it can be a road map to discovering where misattributions began. The following is a complete chronology of books that depict hallmarks used by American Indian silversmiths.

Over forty years ago, in December 1972, Margaret Wright’s groundbreaking book Hopi Silver: The History and Hallmarks of Hopi Silversmithing was published by Northland Press. It included the first visual representations of hallmarks used by Hopi silversmiths, over 150 marks were depicted in the first edition. Margaret Wright’s research started in the archives of the Museum of Northern Arizona and took her to the Hopi mesas where she recorded on sheets of copper the hallmarks used by all of the living silversmiths she could find.

Over forty years ago, in December 1972, Margaret Wright’s groundbreaking book Hopi Silver: The History and Hallmarks of Hopi Silversmithing was published by Northland Press. It included the first visual representations of hallmarks used by Hopi silversmiths, over 150 marks were depicted in the first edition. Margaret Wright’s research started in the archives of the Museum of Northern Arizona and took her to the Hopi mesas where she recorded on sheets of copper the hallmarks used by all of the living silversmiths she could find.

In 1975 Barbara and Ed Bell published volume one of Zuni: The Art and the People with volumes two and three following on its heels. These volumes each profiled approximately fifty silversmithing families then working at Zuni and either discussed or illustrated their hallmarks.

In 1975 Barbara and Ed Bell published volume one of Zuni: The Art and the People with volumes two and three following on its heels. These volumes each profiled approximately fifty silversmithing families then working at Zuni and either discussed or illustrated their hallmarks.

Mark Bahti’s excellent book Collecting Southwestern native American jewelry was released in 1980 and included twenty-two pages of hallmarks used by American Indian silversmiths, for the first time from more than a single tribal group, as well as a page of shop marks.

Also in 1980 Gordon Levy published Who’s Who in Zuni Jewelry profiling sixty-eight silversmiths working at the time.

In 1989 Barton Wright, in association with the Indian Arts and Crafts Association, published Hallmarks of the Southwest with 140 pages of biographical entries and illustrated hallmarks for American Indian artists, mainly silversmiths.

In 1989 Barton Wright, in association with the Indian Arts and Crafts Association, published Hallmarks of the Southwest with 140 pages of biographical entries and illustrated hallmarks for American Indian artists, mainly silversmiths.

These five volumes laid the groundwork for the current understanding of American Indian jewelry hallmarks.

Margaret and Barton Wright’s books have both been revised and expanded over the years as more information became available.

A Second Edition of Hopi Silver was released in October 1973, with a Third Edition published April 1982, which included additional hallmarks; the first three editions of this book featured blue covers.

The Fourth Edition of Hopi Silver came out in 1982, ten years after the original. This expanded edition, with a new burgundy color cover, contained additional pages of hallmarks.

Then in 1998 came the Fifth Revised Edition of Hopi Silver, with a complete design makeover of the contents and a cover featuring Hopi silversmith Pierce Kewanwytewa. It not only included over 100 new hallmarks but an index of hallmarks by type, and new images of never before published jewelry (full disclosure: some of that jewelry was from my personal collection).

After Northland Press folded the Fifth Edition of Hopi Silver: The History and Hallmarks of Hopi Silversmithing was reissued in 2003 by University of New Mexico Press with a new cover.

After Northland Press folded the Fifth Edition of Hopi Silver: The History and Hallmarks of Hopi Silversmithing was reissued in 2003 by University of New Mexico Press with a new cover.

Also notable in 2003 was the publication of Hopi Silver in Japan with a completely different cover but retaining the same information and interior photos as the English language edition.

Also notable in 2003 was the publication of Hopi Silver in Japan with a completely different cover but retaining the same information and interior photos as the English language edition.

Barton Wright’s Hallmarks of the Southwest was significantly expanded for the second edition in 2000, and this has become the industry standard for hallmark identification.

Barton Wright’s Hallmarks of the Southwest was significantly expanded for the second edition in 2000, and this has become the industry standard for hallmark identification.

In 2011 Bille Hougart self-published The Little Book of Marks on Southwestern Silver: Silversmiths, Designers, Guilds & Traders. The inclusion of actual images of hallmarks makes this book stand out from Hallmarks of the Southwest. However, many of the errors that occurred in Wright’s book are carried on in this volume.

In 2011 Bille Hougart self-published The Little Book of Marks on Southwestern Silver: Silversmiths, Designers, Guilds & Traders. The inclusion of actual images of hallmarks makes this book stand out from Hallmarks of the Southwest. However, many of the errors that occurred in Wright’s book are carried on in this volume.

Hougart released a revised edition in 2014 with the publication of Native American and Southwestern Silver Hallmarks. This is currently the most complete and accurate hallmark guide on the market.

Hougart released a revised edition in 2014 with the publication of Native American and Southwestern Silver Hallmarks. This is currently the most complete and accurate hallmark guide on the market.

Gregory and Angie Schaaf published the first volume of the American Indian Jewelry series in 2004 with updated volumes 2 and 3 appearing in 2013 and 2014 respectively.

American Indian Jewelry I: 1,200 Artist Biographies

American Indian Jewelry I: 1,200 Artist Biographies

American Indian Jewelry II: A-L: 1,800 Artist Biographies

American Indian Jewelry II: A-L: 1,800 Artist Biographies

American Indian Jewelry III: M-Z

American Indian Jewelry III: M-Z

These are excellent resources for the work and hallmarks of living artists, but are unfortunately replete with errors for many of the deceased silversmiths; errors which, in our opinions, have muddied the waters. For instance, in the first volume they write that Navajo silversmith Mark Chee, “worked as a bench smith for Frank Patania,” at the Thunderbird Shop. However our research found no link between Chee and the Thunderbird Shop, though we could confirm employment in Santa Fe with Julius Gans at Southwest Arts & Crafts before WWII and with Packard’s at Chaparral Trading Post after the war.

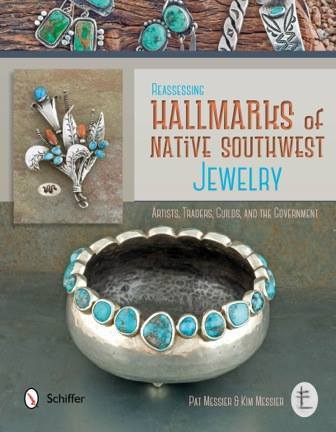

This is not intended as a shameless plug, but omitting Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry: Artists, Traders, Guilds, and the Government might seem like an oversight on my part. This was the biggest project Pat and I have ever undertaken, and are grateful for the opportunity to make crucial corrections, and hope the book opens the door to further research.

This is not intended as a shameless plug, but omitting Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry: Artists, Traders, Guilds, and the Government might seem like an oversight on my part. This was the biggest project Pat and I have ever undertaken, and are grateful for the opportunity to make crucial corrections, and hope the book opens the door to further research.

Before the publication of Hopi Silver in 1972 the individual artists received little attention from the buying public. Therefore it was generally believed that Indian jewelry wasn't hallmarked before the 1970s. This mistaken perception persists to this day, as some collectors and dealers are adamant that if a piece is hallmarked it must have been made after the 1970s because they are convinced artists did not sign their work before that time.

Yet individual silversmiths began to sign their work in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Navajo Fred Peshlakai has often been cited as one of the first silversmiths to hallmark his work. But it has also been documented that Juan De Dios of Zuni Pueblo used a chisel to stamp his initials on the back of some pieces in the late 1920s. Also Grant Jenkins, a Hopi silversmith, signed some of his pieces during his short career from 1924 until his death in 1933. Perhaps prompted by their Anglo employers, many silversmiths who worked in urban areas began signing their work in the 1930s, using symbols or their initials as identifying marks.

Most of these early hallmarks were not documented at the time because jewelry was usually considered as little more than curio items. This is why the research done in the 1970s and 1980s is so valuable today; it would be nearly impossible to reconstruct the information that was gathered three and four decades ago. Not only did it call attention to individual silversmiths for the first time, it also laid a foundation for further research.

Barton Wright was well aware his book contained mistakes, as he stated in the introduction to his first edition of Hallmarks of the Southwest:

Foremost among the points that must be kept in mind is the fact that this is not an exhaustive work but one, it is hoped, to which additional information may be added. Secondly the fact that there are errors in the data is fully recognized. However the impossibility of removing such errata is apparent when it may require a year to check out a single mark. The elimination of these mistakes requires the cooperation of craftsmen and those who work with them.

It’s unfortunate that later publications did not heed Barton’s warning of the mistakes in his book, because as Mark Bahti has observed, “Over time some writers have simply repeated what earlier writers said about artists, and in doing so, they unwittingly, even carelessly, repeated incorrect information. Factual information about some artists that was generally known in the 1940s and 1950s, even the 1960s, began to dissipate in a wave of digital repetition of errors.”

Some of the more pervasive mistakes in Hallmarks of the Southwest were misconstruing Austin Wilson for Ike Wilson (we blame C.G. Wallace for starting that confusion), attributing Ambrose Roanhorse’s stick horse figure hallmark to Fred Peshlakai (with the legs erroneously forming the initials FP), and the unfortunate mash-up of Ambrose Roanhorse and Ambrose Lincoln into one individual. While Mark Bahti in his 1980 book correctly identified the hallmark of a capital A in a keystone figure to Ambrose Lincoln, Wright later misconstrued these two Navajo silversmiths as the same individual who used the A in a keystone mark. Roanhorse actually used a stick figure of a horse whose legs formed the initials AR. This error has caused the work of Ambrose Lincoln, often consisting of cast pieces with Zuni style inlay, to be sold and priced as if the master silversmith Ambrose Roanhorse had made it.

It’s not hard to imagine how these mistakes came about in a time before the Internet. In the 1970s and 1980s the only way to communicate with traders and artists was by writing letters and hoping for a reply, or by traveling to their business or residence. As Barton wrote in his introduction, quoted above, it may have required a year or more for verification of a single hallmark. It was difficult, mind-numbing research, and one incorrect attribution from a trader with a faulty memory could have been the only attribution available at the time.

These are the kinds of inaccuracies that have haunted Indian jewelry for a very long time. During the past few decades new information has been uncovered, in large part due to the availability of historic documents on the Internet, which have contributed to the broadening of the knowledge of hallmarks applied to Indian jewelry. For instance, it is now possible to properly identify the hallmark used by Navajo silversmith Ike Wilson from a 1942 newspaper article about his accidental death at the hands of his wife Katherine; and by an advertisement placed in a 1976 issue of American Indian Art Magazine that shows Katherine was still using a bow-and-arrow hallmark long after her husbands’ death.

However, there are more corrections still to be uncovered and many unknown hallmarks that need to be identified. Pat and I will never cease researching hallmarks, even though our magnum opus has been published, and we hope to continue to contribute to the research in the field.

Postscript: One of the reasons I made a chronology for myself of hallmark books is so I could comprehend how accurate each publication might be. For instance with the Zuni books published in the 1970s by the Bells and Levy's book from 1980, the authors went right to the Zuni artists currently working and asked how they signed. This means they had primary sources and there is no refuting their research. The same for Margaret Wright's Hopi Silver concerning the artists who were alive during her periods of research, she had primary sources. However, it gets tricky for any researcher of hallmarks when the silversmith is deceased by the time they start their research. Then the researcher must rely on the memory of the artists family members or traders/dealers or the database of museum collections to determine accuracy of hallmark attribution.

Post Postscript: The publication, in the summer of 2016, of the Third Edition of Native American and Southwestern Silver Hallmarks, by Bille Hougart has provided by far the most accurate, reliable and comprehensive hallmark identification guide ever published. Please read my explanation in the following blog: The Definitive Hallmark Reference Guide and Why You Should Own It

The publication, in the summer of 2016, of the Third Edition of Native American and Southwestern Silver Hallmarks, by Bille Hougart has provided by far the most accurate, reliable and comprehensive hallmark identification guide ever published. Please read my explanation in the following blog: The Definitive Hallmark Reference Guide and Why You Should Own It

December 10, 2014

Caveat Emptor

Latin for "let the buyer beware." A doctrine that often places on buyers the burden to reasonably examine property before purchase and take responsibility for its condition. Especially applicable to items that are not covered under a strict warranty.

And even more applicable to vintage, pawn or antique American Indian jewelry.

There is a distressing recent trend in the vintage American Indian jewelry market - that of applying faked hallmarks of highly collectible silversmiths to jewelry of dubious quality. This trend started some years ago with the fabrication of jewelry in the style of Charles Loloma to which fraudulent hallmarks were applied. That nearly ruined the market for Loloma’s jewelry as dealers and collectors that had been burned by fakes were (and still are) leery to consider investing again. And with good reason, those fakes will haunt the market for decades to come.

Left: Example of fraudulent Charles Loloma hallmark

Now this practice has extended to the application of fraudulent hallmarks of other important silversmiths, such as Ike Wilson, Fred Peshlakai, Preston Monongye and Frank Patania, to jewelry of poor quality, and often made by Anglo silversmiths.

It should be noted that this isn’t the first time fake Indian jewelry has flooded the market. Starting in the early 1900s and continuing for decades, the mass-production of machine made Indian style jewelry made companies like H.H. Tammen, Arrow Novelty Company, Silver Products, Bell Trading Company and Maisel’s financially successful while the native artists struggled.

Those who remember the “Boom” of the 1970s are also familiar with the reproductions of traditional Navajo silver by hippie silversmiths from the Pagosa Springs, Colorado region and the proliferation of Anglo made Indian style jewelry. Few of these pieces were hallmarked so many have passed, and continue to pass, as "old pawn."

Also memorable was the preponderance of counterfeit Navajo spoons, most often in the style featuring the profile of an Indian in a headdress on the handle or with the word NAVAJO etched in the bowl, after the publication of Navajo Spoons in 2001. While fake Hopi overlay, with contrived hallmarks, and fake Zuni inlay, copied from vintage issues of Arizona Highways magazine have been imported from international (off shore and south of the border) locations, and sold online and in disreputable shops for over a decade.

Previously buyers could be assured of the authenticity of a piece if it bore the hallmark of a recognized artist, and it didn’t require them to have a great deal of knowledge about the history of Indian jewelry to feel comfortable investing in high quality jewelry. But now it's becoming common to see hallmarked jewelry misrepresented as that of some of the most respected and highly collectible silversmiths. This doesn’t even take into account the misattributions by uninformed, or overly optimistic sellers, a practice which is rampant on eBay and internet auction sites.

eBay is no help in these matters. As much lip service as they give to stopping counterfeiters from selling through their website, they make it inordinately difficult for buyers to report sellers of fakes. One shouldn’t need to jump through hoops, nor spend hours on the phone, to advise eBay that someone is profiting from selling counterfeits on their platform. Even more frustrating is that spurious listings are rarely ended by eBay even after they have been reported.

So how can collectors protect themselves when thousands of dollars can be at risk on a single bracelet? First, caution is the key to online transactions, if it seems too good to be true, then it probably is. But most importantly, buyers should educate themselves and become familiar with the styles and workmanship of the silversmiths they wish to purchase. Faked jewelry will often not resemble the work of the masters in either style or quality. For collectors, working with a trusted dealer is essential in gaining the knowledge necessary to make informed purchases.

The artists whose hallmarks are currently being forged are deceased (convenient for the forgers), and their work commands top dollar. These artists did not become so respected, and their jewelry so highly valued, because they produced inferior work. These artists made jewelry of the highest quality. Contrary to opinions that even great silversmiths had bad days, substandard work is the hallmark of the amateur, inexperienced, or sloppy silversmith. Poor quality silverwork or low grade and treated stones should raise red flags right away that the artist was not a skilled silversmith.

The only way to combat the fakers is through knowledgeable buyers. Once everyone sees their forgeries for what they are, and their market dries up, then they will stop counterfeiting Indian jewelry and move on to something more profitable (and hopefully something you don’t collect).

Examples of recent forged hallmarks

Below: NOT a hallmark used by Bernard Dawahoya

Below: NOT a hallmark used by Preston Monongye #1

Below: NOT a hallmark used by Preston Monongye #2

Below: NOT a hallmark used by Fred Peshlakai

Below: NOT the shop mark used by Frank Patania or the Thunderbird Shop

Updated Dec 27, 2015 = Here's a new one, a poor attempt to fake the hallmark of Morris Robinson.

Updated May, 17, 2016 = This is definitely NOT the hallmark used by Hopi Harold Koruh.

And this is even more inventive, adding the H to make it appear to be a hallmark used by an early Hopi silversmith...again, NOT Harold Koruh's hallmark.

October 17, 2014

Arizona State Museum - Coffee with the Curators

Join us on Wednesday, November 5, for the next installment of Coffee with the Curators! Join us for a cup of coffee and informal conversation with authors Pat Messier and Kim Messier who will discuss their newest book, “Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry.” Enjoy seeing pieces of jewelry from ASM’s collections and selected pieces from the authors' collection that were highlighted in the book. 3:00 p.m., FREE, ASM lobby.

Arizona State Museum is located on the University of Arizona campus, 1013 E. University Blvd., Tucson, AZ. Phone: 520-621-6302

September 25, 2014

I Heart Books

There's a “game” circulating around FaceBook called I Love (Heart) Books. The rules are simple, In your status list 10 books that have stayed with you in some way. Don't take more than a few minutes and don't think too hard. They don't have to be the "right books" or great works of literature, just the ones that have affected you in some way. If you know anything about me you probably know that I love books, and I also like to make lists of things, so this is right up my alley. I recently posted this list on my Facebook wall, these are the first ten books that came to my mind while I was thinking about the task (and also watching television). After posting the list I pondered why these were the first ten books to come to mind, what made them stand out above everything I have ever read? Below are the answers I came up with.

The Native American Curio Trade In New Mexico, Jonathan Batkin. The second half of this groundbreaking volume, the epitome of excellent research, focuses on Indian silversmiths who left the Pueblos and reservations to work in curio shops in Santa Fe and Albuquerque in the early part of the twentieth century. Batkin, director of the Wheelwright Museum in Santa Fe, found with the use of period city directories he could identify, and trace employment, for those individuals. This opened Pat’s and my eyes to other avenues of research and allowed us to tell the in-depth stories of many silversmiths in Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry: Artists, Traders, Guilds, and the Government.

The Hundred Secret Senses, Amy Tan. I read this novel shortly after publication in 1995, and though I don’t recall much specifically, I still have the memory of how much I loved it, and that it was exotic and moving and the prose was rich.

Animal Dreams, Barbara Kingsolver. Why this novel from Kingsolver stays with me, over all the other wonderful southwestern books she wrote, is hard for me to discern. I remember a scene that takes place at Kinishba Ruins—which is somewhere I have visited—and also the push-and-pull of family ties, what they mean to us and the stories we tell ourselves about them.

Navajo Spoons: Indian Artistry and the Souvenir Trade, 1880s-1940s, Cindra Kline. After reading this well-researched volume dedicated to one specific form of silver made by Navajo smiths, and then meeting the author, I realized that if she could publish a book, then so could I. Thus the seed of Hopi & Pueblo Tiles: An Illustrated History was planted.

A Match to the Heart: One Woman's Story of Being Struck By Lightning, Gretel Ehrlich. A remarkable recounting of Ehrlich’s experience of being struck, literally out of the blue, by lightning. Her retelling of the after-effects on her body are unforgettable.

Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, Anne Lamott. This book helped free up my writing skills. It made me realize what I write cannot be a masterpiece from the moment it leaves my pen, or makes characters on the computer screen. This is where I learned to just sit my butt in a chair and write, “a shitty first draft”. Amen, sister!

Gone with the Wind, Margaret Mitchell. Maybe because the movie is so memorable the book has stayed with me. But I remember thinking the book was better than the movie when I read it. Still, it's an everlasting piece of work, so evocative of one of the most mournful chapters in this nation's history.

The Man Made of Words: Essays, Stories, Passages, N. Scott Momaday. I gave this a starred review in Publishers Weekly when it was released in 1997 and this blurb from that review ended up on the back cover of the paper edition, "A preeminent voice in Native American literature . . . few authors write as gracefully or majestically as Momaday". I attained a better understanding of American Indian oral tradition and literature through the reading of this wonderful volume.

Yellow Woman and a Beauty of the Spirit, Leslie Marmon Silko. My take-away from this book was the relationship between “federally recognized” Indian tribes and the US government, how these nations were, and still are, regarded as sovereign nations living within the boundaries of the United States. And of how the average American citizen has little idea why they get “special” treatment, nor that what the federal government bestows in no way repays for their horrifying treatment during the years of Manifest Destiny and beyond.

The Death of Bernadette Lefthand, Ron Querry. The author stopped me in the aisle at the American Booksellers Association convention in Miami Beach in 1993 with a hearty, “Hey, there’s someone else from Tucson!” I talked to him about Tucson and his novel–which he signed a copy of to me–for quite a while. Of the many advance reading copies I toted home from that show this was the first book I read. I was impressed with Querry’s ability to write from a woman’s viewpoint and have read the novel more than once. Querry and his lovely wife Elaine became friends and I spent some quality time with her while Ron worked on his next novel.

Of course I could have listed so many other influential books I have read, Cat's Cradle, Cowboys Are My Weakness: Stories, She Who Remembers, or many of the mystery novels by Tony Hillerman. But those listed here really are the first ten that came to mind, so their influence on me must be strong, or at least emotional in some way.

August 4, 2014

Amazon and the Missing Month

Yes, the book is finally an actual thing we can hold in our hands. And it is a thing of beauty, if I have to say so myself. Schiffer must have assigned their A-List designer to the manuscript, because the layout and presentation is all we had hoped it would be, and then some. Pat and I are so delighted and proud of it we could almost burst with enthusiasm.

We received our initial order of books from the publisher on July 10, immediately fulfilling orders from folks who had requested to purchase directly from us. Then came the inevitable, requisite eBay listing. Nothing gets seen faster in the Indian jewelry community than an eBay listing with the proper high profile names such as Kenneth Begay and Fred Peshlakai, both of whom we profiled in the book. So we listed copies along with select pieces of jewelry illustrated in it to generate some excitement and maybe sell a few pieces of silver to kick things off. However, after ten days all 12 copies of the book had sold but only one piece of jewelry. Perhaps we were a bit premature in listing the jewelry since there just wasn’t enough exposure for the book yet.

So many of our friends and colleagues pre-ordered from Amazon that we have been unable to fully discuss it with everyone, though we have received some very nice comments and endorsements from those who have read the book, and that is very gratifying. At least it looks like Amazon will deliver the pre-orders in time for the festivities in Santa Fe later in August. By the way, if you happen to be in the area, our first signing is at Bahti Indian Arts on Palace Ave on Saturday, August 16 from 5pm to 7pm. There will also be select pieces of jewelry from the book for sale that weekend at the gallery. See you there!

June 15, 2014

Coming Soon...

Publishing isn’t an easy journey for authors. Comparing notes with colleagues confirms similar disappointments and difficulties; it is perhaps the singularly most frustrating experience a person could voluntarily take part in. Getting to the end with a finished book in hand is a minor miracle. Not saying it’s impossible, Pat and I have managed to do it twice, just that patience is a virtue with publishing, and it’s really difficult to maintain patience during the long, drawn-out process...the last stage required in a prolonged journey to turn your hard work into something tangible.

After years of researching and writing a manuscript it still takes 18 to 24 months for it to be turned into a finished book. From the first contact with the publisher—submitting a proposal—to signing a contract, completing and submitting the manuscript, pre-production editing and finally the day your first comp copy arrives is a lengthy, anxiety-filled process.

While working with Schiffer Publishing has been a much different, and improved, experience than our first with Rio Nuevo Publishers, there have still been frustrating moments. We sent our manuscript off the first week of June 2013 and spent six months waiting for something to happen, with only a cover design and release date (and listing on Amazon) to show for it. Then just days after the beginning of 2014 the text galleys arrived in our email. Two days later they were corrected and returned, and Pat and I were sure the design proofs weren’t far behind. Silly us.

We had estimated backwards from the announced release month of June 2014 to determine at what point the publisher needed to finalize pre-production and send everything to the printer in China to be able to meet that date. Allowing for the manuscript to progress to the design phase, we expected the proofs to deliver sometime in February or March. By the end of March when we hadn’t heard anything we knew time was running out.

We waited, to use Pat’s apt metaphor, like we were standing on a trap door with a noose around our necks anticipating when someone would pull the lever. Finally on May 7 Schiffer pulled the lever and sent the proofs. It's a good thing they arrived when they did, Pat and I were on edge, taking our frustrations out on each other since we couldn't take them out on Schiffer.

Still the total lack of communication while the manuscript moves through the painstakingly slow production phases is mind-numbing. Sometimes it feels as if your project no longer belongs to you, as if your child has been abducted and you are anxiously awaiting the next phone call from the kidnappers. But on the contrary – you willingly sent your baby to these people hoping they would provide polish and style to transform your unschooled and graceless offspring into something shining and beautiful. Because authors believe in the transformative powers of bound signets, dust jackets and the smell of fresh printers ink.

The greatest advantage Schiffer offers is more creative control than most publishers, but with that freedom also comes the responsibility of more work. We received a 48 page booklet detailing exactly how they wanted the manuscript and images formatted for their process. We found that the booklet answered a lot of questions and by following the directives our manuscript moved through the editing phases as efficiently as possible with only minor changes to our vision.

The biggest change made to our project was the title: “Marked By Design: Hallmarked Southwestern Indian Jewelry” became the even clunkier, Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry: Artists, Traders, Guilds, and the Government. We understand the reasoning, and it does perhaps describe the contents better than our title, but nine months after it was assigned I still have trouble remembering it. However, we were comforted by Barton Wright’s wise words during the editing of the tile book, “fight the big fights, let the little stuff go.” So the title is just fine, thank you very much.

So, back to the proofs… While reviewing them for errors and finalizing the index, the line "Never index your own book" from Kurt Vonnegut's novel Cat's Cradle kept going through my head. One character, a professional indexer, says it's self-indulgent and amateurish for an author to index his own work. As it turns out, Vonnegut was both wrong and right. Indexing one’s own book isn’t unprofessional or self-serving—many publishers now require authors to make their own index—but it is so tedious and fraught with pitfalls, that after two full days of combing the text and captions for references, then checking and cross-checking, you pray that anyone would take the task out of your hands.

Now that the final pre-publication processes are done, and the book has been sent off to the printer the anticipation ramps up. Marketing and booksignings need to be arranged, and print ads and promotional opportunities explored. We need to hit the ground running though since we lost five weeks of transit time between the printer and publisher since Schiffer sent our book to an American printer instead of to China. This is good news, and allows them to meet the original June 28 pub date, however we are left with only a few weeks to make arrangements.

In the end, I suspect authors are so happy to realize their vision in print that all the frustrations and anxiety leading up to publication date are washed away when they clutch the first finished copy of their very own book. It’s the culmination of so much hard work and vindication of the sacrifice and anxiety; it’s akin to redemption. And consider this last fact: to fulfill the mandatory deposit requirement of the copyright law two copies of the finished book will be sent to the Copyright Office for permanent repository in the Library of Congress. Hopi & Pueblo Tiles: An Illustrated History can be requested in the Jefferson or Adams Building Reading Rooms. How could any American author not be gratified of that accomplishment?

April 29, 2014

Write What You Know

From the time my love affair with books began I have contemplated books, authors and the business of publishing. At age twenty I landed my first bookselling job at a Waldenbooks in the Glendale Galleria (in a suburb of Los Angeles). There I worked with a woman I greatly admired, a graduate student who is now head of the Comparative Literature Department at Cornell University, and tried to absorb everything she offered. She was exotic, studying abroad in Egypt, and I wanted to be just like her. But I wasn’t like her, and never could be. She had fully grasped her passion; mine was still waiting to find me.

Some months later I found myself in another Waldenbooks in another city, this time in Sacramento. And a year later I was preparing to move back to Tucson when one of my co-workers, an art student at the university, bestowed me with a life-changing gift. Since I was returning to the southwest, she thought one of her unfinished paintings of a kachina doll would be a fitting going-away gift.

Now only a black-and-white photo memory preserved in a scrapbook, back then I was so enthralled by the gift of original art that I went to the time and expense to have it framed and hung it proudly in my room. Yet a single piece of art looks lonely without companions, so I started buying inexpensive Southwest Indian pottery items for decorative purposes. This led to a curiosity of the people that made those items and a desire to collect something from every pottery-making tribe in the southwest. Which led to studies of those cultures and American Indian history… where I discovered prehistoric southwest cultures…which led to…well, my passion had snuck up on me.

Shortly after I was hired in 1987 by The Haunted Bookshop in Tucson I was well enough versed in western history and American Indian literature to be put in charge of the southwest section of the store. I read voraciously during my tenure, eventually becoming brave enough to write the occasional book review for a local periodical The Desert Leaf. Before Haunted closed in 1997 I had been accepted by Publishers Weekly as a reviewer of books on American Indian and western history topics. What a cool, and challenging, gig!

Gradually I realized anyone could publish a book—that it didn’t take an advanced degree and superhuman powers—a seed was planted of one day joining the community of authors. The old adage goes, “write what you know,” and the one thing I did know well was American Indian art. Yet my first contacts with publishers were fraught with disappointment and failure, but those are other stories for other times.

The book Navajo Spoons: Indian Artistry and the Souvenir Trade, 1880s-1940s published in 2001 boosted my resolve. The author wasn’t an academic, an anthropologist, nor (discovered during a happenstance meeting) particularly knowledgeable about American Indian art. Yet she published an informative, professional book put out by the Museum of New Mexico Press, one of the most respected southwestern publishing houses. With the success of a book so focused on one small aspect of Indian art—spoons made by Navajo silversmiths—I was sure we could accomplish something that would interest a publisher. But on which topic?

By the late 1990s Pat and I had gone through many phases in our collecting careers, from novices with small budgets, to more knowledgeable and selective buyers building collections that told stories. Pat focused on Hopi and Pueblo made pottery tiles, while I was fascinated with anything Hopi, particularly the silver jewelry made by early silversmiths who left the mesas to work in curio shops in the cities.

Long story short – in the summer of 2007 Pat and I joined the ranks of published authors as Rio Nuevo Publishers released  Hopi & Pueblo Tiles: An Illustrated History. We promoted the heck out of it and managed to sell nearly 1700 copies in the first six months of release. As of February 2014 Rio Nuevo counted only 172 copies remaining in their inventory and our royalty statements showed 2690 copies sold by the end of 2013.

Hopi & Pueblo Tiles: An Illustrated History. We promoted the heck out of it and managed to sell nearly 1700 copies in the first six months of release. As of February 2014 Rio Nuevo counted only 172 copies remaining in their inventory and our royalty statements showed 2690 copies sold by the end of 2013.

But the end result was not easily accomplished and we devoted many hours, and called in a few favors, to make it happen. It’s not an easy journey and publishing is perhaps the singularly most frustrating experience a person could voluntarily take part in. Getting to the end with a finished book in hand is a minor miracle.

One thing we learned along the way is that our books have a determined and precise audience, and that our best promotional opportunities are at Indian art shows and galleries in Santa Fe in the summer and during the winter months in Southern Arizona. And more and more social media is where we find the best promotional opportunities.

March 13, 2014

Southwest Indian Art Fair at Arizona State Museum

It should be noted that the 2014 Southwest Indian Art Fair described below was the second-to-last fair ever held. Arizona State Museum director Patrick Lyons made the sad announcement in September 2015 that ASM will no longer produce the fair; not that they would be taking a breather from hosting the fair, but canceling their involvement in it altogether.

It should be noted that the 2014 Southwest Indian Art Fair described below was the second-to-last fair ever held. Arizona State Museum director Patrick Lyons made the sad announcement in September 2015 that ASM will no longer produce the fair; not that they would be taking a breather from hosting the fair, but canceling their involvement in it altogether.The original blog post follows...

As the Arizona State Museum website states:

The Southwest Indian Art Fair began in 1993 as a small pottery fair. Since then, it has grown to be the highlight of Arizona State Museum's annual educational and cultural celebrations, as well as a highly anticipated feature of Tucson’s winter festival calendar.It’s possible I was there for the inaugural event as I remember attending a small show and sale of pottery at the museum in the early 1990s, but I am not certain which year. Nevertheless SWIAF, held annually on the campus of the University of Arizona in Tucson, has become a highlight of our Indian art season here in Southern Arizona.

For the past three or four years Pat and I have sponsored a jewelry award for the fair. One of the rewards of being a sponsor is attending the Awards Reception the night before the fair opens to see all the entries, the winners, meet some of the artists and say hello to friends who are fellow ASM members and also those on the museum staff. The grounds are lovely at night, the tents are set up on the grass, and it’s the quiet before the storm, so to speak.

We’re always excited to see the magnificent creations that are entered, and to admire the masterwork that receives our sponsored award. This year’s went to Jake Livingston, a master jeweler of Navajo/Zuni heritage for his stunning silver and coral buckle.

Early Saturday morning we arrive with tickets in hand, an hour before the gates officially open, for members-only early bird shopping, eagerly plotting which booths to hit first.

We also spend time in the morning viewing the offerings at the benefit sale/silent auction tent for the Friends of Arizona State Museum and often find a vintage treasure or two that was donated to the Friends organization. The air is usually crisp and the crowds are sparse so the morning is one of my favorite times at the fair.

After the gates open to the public at 10am the aisles grow crowded with shoppers and the tents sometimes become a challenge to navigate.

But the performances start shortly afterwards and many attendees move to the stage area to witness the music and dancers from various southwest tribes.

As the fair has grown in size over the years so has it grown in prominence; for a number of years it has attracted some of the finest American Indian artists working today. For example, below is another fabulous jar from Susan Folwell, the multi-talented potter from Santa Clara Pueblo. Susan is a creative and innovative potter, constantly reinventing herself and I never cease to admire her work. Her mother Jody Folwell, an award-winning master potter, was the featured artist at the 2014 fair. But does the couple depicted on this jar look familiar?

For the first time ever at an Indian art exhibit I purchased an award-winning piece this year. At the awards reception I couldn’t take my eyes away from this remarkable photo taken at White Sands National Park by Priscilla Tacheney, Navajo, which took a First Place ribbon in the 2D Art category. I couldn’t believe this piece hadn’t sold before I found her booth on Saturday morning. Now it hangs in a prominent place over my bed.

Arizona State Museum doesn’t simply view the fair as an opportunity for art collectors to buy direct from the artists. They also see it as a cultural exchange between the American Indian artists, musicians and dancers and the attendees who may not otherwise have an opportunity to interact with cultures that many Americans still mistakenly believe “vanished” over a century ago. Though the fair has traditionally been held every February, this year it was on February 22 and 23, 2014, next year it is scheduled for March 28 and 29, 2015. So mark your calendars for an entertaining and rewarding experience. We'll be there!

February 9, 2014

High Noon Western Auction and Antique Show

This is the 24th year for one of the nation’s premier antique western shows which features over 150 exhibitors of vintage and antique western art, movie memorabilia, western kitsch, boots and clothing, cowboy and horse trappings as well as American Indian art, crafts and jewelry.

Pat and I were latecomers to joining the fun since we weren’t able to attend – mainly due to Pat’s work schedule – until 2010. Now we always look forward to visiting with dealers and friends from across the southwest that we don’t often see. And we are typically delighted by unique Indian art and jewelry treasures that we are compelled to bring back home. This show is a nice change of pace from the Indian art antique shows we attend in August in Santa Fe in that the atmosphere is more laid back and the prices are generally more modest.

Though the dealers we spoke with this year reported good sales on Friday and Saturday, with many buyers purchasing early entry during dealer set up on Friday, attendance appeared to us lower than normal. We didn’t find much to buy this time around, only a Hopi wicker basket and a curious pill box ring by Hopi silversmith Ralph Tawangyouma. Was our lack of discoveries because we were severely burned out on jewelry after all the time required to complete our forthcoming magnum opus? Or was it because the offerings just seemed tired? Perhaps it was a combination of both. Still we thoroughly enjoyed talking with everyone and it was our first opportunity to spread the word about our impending publication.

On Saturday we always take a break from enjoying the show to peruse the preview of the auction, which typically offers some truly unique and valuable lots as evidenced in 2012 by Pancho Villa’s last saddle which achieved over $700,000. Normally we don’t find anything up for bid that interests us enough to make the effort to attend the auction on Saturday night. This year was no exception, though the High Noon post-auction press release announced that a Colt .45 pistol used by James Arness in the television series Gunsmoke sold for $59,000 and a pair of spurs from an important California maker commanded an astonishing $153,400! Native American art was also among the lots presented and a Plains pipe tomahawk fetched $26,050 while a Navajo sand painting rug sold for $22,420.

The Marriott Mesa Hotel and Convention Center hosts the show each year, and for us one of the highlights is not only staying in the hotel where the rooms are clean, comfortable and the service indulgent but also the convenience that the entrance to the show is just a few steps from the hotel lobby.

January 16, 2014

New year, new venture

I’ve been thinking a new year warrants a new venture. And I’ve been thinking of blogging this year about the experience of having a new book released from a different publisher than Pat’s and my previous book Hopi & Pueblo Tiles: An Illustrated History. I signed on to Goodreads in an attempt to get myself back into the book world, after having been cloistered in the research-and-write world for far too long. I soon discovered they have an Author Program, and after mulling my time constraints – and the necessity to promote a new book this year – I signed up for it. As part of my membership (either on Goodreads, or as part of the Author Program, I do not know which) I am able to post blogs. So, I’m going to give it a try. I’m hoping to somehow integrate this into my FaceBook account for those folks who follow Indian Jewelry but aren’t necessarily book lovers.

I’m planning on posting randomly, as my time allows, and as something of interest strikes me. Possible topics include the realities of promoting a new book, books and authors, American Indian jewelry and arts, and who knows what else. Don’t be surprised if my fabulous co-author (who is also my mother) Pat Messier makes some surprise appearances. My main goals are not to be boring, pompous, or offensive. Wish me luck.

Please feel free to post comments or send me an email with your thoughts.