Kim Messier's Blog, page 2

September 25, 2016

Note to Self

First page of our * First Draft completed today...

* (Insert appropriate expletive, a la Anne Lamott, here)

June 30, 2016

The Metalwork of Awa Tsireh

San Ildefonso artist Awa Tsireh (Alfonso Roybal) is best known as an early master of Pueblo painting; but in his lifetime he also gained renown as a silversmith.

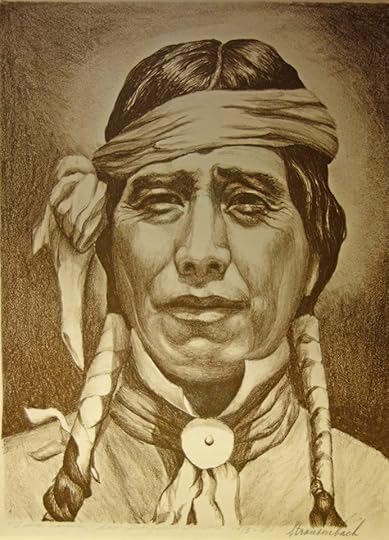

Sepia-toned lithograph of Awa Tsireh made by Charles Strausenback ca 1930s

Awa Tsireh (pronounced Ah-wah Sid-ee or See-day) was born in 1898 to Juan Estevan and Alfonsita Martinez Roybal; he was the eldest of six children. He drew sketches of dances and animals even before attending San Ildefonso Day School where the teacher provided drawing supplies. He did not continue his education after leaving the day school, and his drawing and painting skills were mostly self-taught; though he also learned from watching his uncle Crescencio Martinez who used watercolors to paint dancers on paper in the mid-1910s for Edgar Lee Hewitt. As a young man Awa Tsireh (Cat-tail Bird) painted the decorations on the pottery his mother made.

Modernist painting of Deer Dancer by Awa Tsireh

In the summer of 1917 Santa Fe poet Alice Corbin Henderson was introduced to Awa Tsireh’s paintings and she became his first patron and promoter. Awa Tsireh’s fame grew nationally in the 1920s prompting a successful one-man show in Chicago; he also painted most of the illustrations for the book Tewa Firelight Tales by Ahlee James published in 1927. In 1931 Awa Tsireh joined with other San Ildefonso artists, including Maria Martinez, Tonita Roybal and Abel Sanchez (Oqwa Pi), to exhibit their works at the Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts in New York City.

Awa Tsireh’s paintings of pueblo dancers and mythology, including black-and-white striped clowns (or kossa) and animals like skunks, owls, and turkeys were meticulously and precisely drawn in both realistic and modernistic styles. Animal forms such as skunks, roadrunners, and owls were also favored subjects of his silverwork.

Silver pins made by Awa Tsireh

It is not known when or from whom Awa Tsireh learned silversmithing but by 1931 he was described in a newspaper article as a painter and, “also a mural painter, a silversmith and a dancer.”

Round copper tray by Awa Tsireh

John Adair reported in his 1944 book The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths that Awa Tsireh was only one of three men in San Ildefonso who worked silver, and that he made pieces in his studio for the tourists who visited the pueblo. However, it was at Garden of the Gods Trading Post in Colorado Springs where the majority of his metalwork was made.

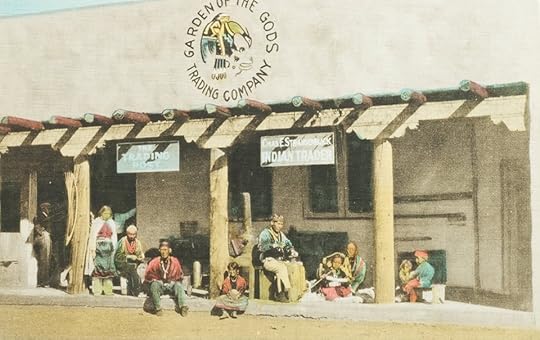

Garden of the Gods Trading Post ca 1930s

Garden of the Gods Trading Post was built in 1929 by Charles E. Strausenback, and is still in operation in the same building on the southern boundary of the Garden of the Gods park in Colorado Springs.

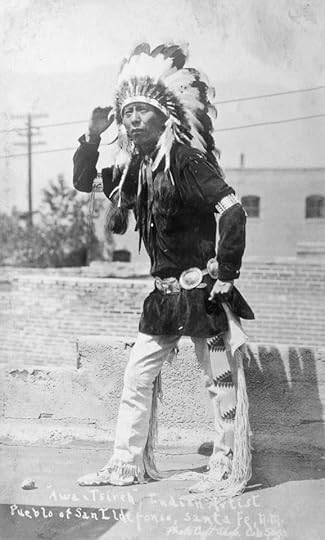

Postcard of Awa Tsireh dressed in Plains attire at Colorado Springs

Awa Tsireh’s association with Garden of the Gods Trading Post had begun by 1930 and continued for at least two decades. His sister Santana Martinez recalled that “during the summer during the thirties and forties he used to go to a shop in Colorado Springs and do his paintings and silverwork there” (Seymour, When the Rainbow Touches Down ). He was the most prominent of the many silversmiths who worked at the trading post over the decades; which included Hosteen Goodluck, Billy Goodluck and David Taliman.

Copper crumb tray in the shape of a cloud made by Awa Tsireh

Awa Tsireh's metalwork did not go without notice, as in 1938, when the Hutchinson, Kansas News-Herald, while reporting on the impending nuptials of a local couple, exclaimed:

Spell it Awa Tsireh—pronounce it A-Wa Si-dy! Whoever he is, he’s the Indian silversmith responsible for that symbolical silver plate which Elizabeth and Joe, to wed today, will give choice place in their household. Of about luncheon size, the plate center is beaten and etched with a god to watch over them, and filled in about and on the rim with emblems of wisdom, constancy, love and happiness. There is no other plate like it and there won’t be for the famous “Awa Sidy” never duplicates. Of New Mexico originally, he’s now collaborating with Charles E. Strausenback in a museum at the Garden of the Gods. The gorgeous silver bracelets which Elizabeth often wears are his work.

Round aluminum tray with Knifewing figure design by Awa Tsireh

He split his efforts between painting and silversmithing during these years and in 1939 was commissioned to paint a mural on the front of the newly erected building to house Maisel’s Indian Trading Post in downtown Albuquerque. The trading post is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places and Awa Tsireh’s mural of a corn dance is still on view on the building's facade.

Mural painted by Awa Tsireh on the front of Maisel's Indian Store in Albuquerque

When it came to metalworking, Awa Tsireh worked in many mediums, not only in silver but also copper, nickel silver and aluminum. What has been written about Awa Tsireh’s paintings is also true of his metalwork, he was precise and meticulous and a master artist. His work shows magnificently designed and stamped elements and elegant repousse work. He helped transform the metalwork made at Garden of the Gods from typical tourist style jewelry—with figural stamps of thunderbirds, arrows and whirling logs popular at the time— into pieces of art, most evident in the trays and pins that he produced.

Spoon, concho pin, matchbook holder, pill box and V for Victory pin all made by Awa Tsireh

Awa Tsireh made a variety of forms during his silversmithing career including bracelets, pins, rings, trays, bowls and concho belts. His work is signed AWA TSIREH and most often with one of the Garden of the Gods shop marks such as SOLID SILVER. Pieces that are only signed with his name, which are rare, were likely made at his studio in San Ildefonso. Items bearing shop marks from the Garden of the Gods Trading Post, but lacking the hallmark for Awa Tsireh, are not of the same quality of work as pieces signed with his name. Consequently, only those pieces bearing his hallmark AWA TSIREH can confidently be credited as his work.

Filed and stamped silver bracelet by Awa Tsireh

His production of paintings and silverwork slowed after World War II, but Awa Tsireh continued to work. In 1954 he was awarded the French government’s Ordre des Palmes Académiques for “distinguished contributions to education or culture” along with eleven other Indian artists including Ambrose Roanhorse, Maria Martinez, Fred Kabotie, Alan Houser and Pablita Velarde.

Though he traveled fairly often, especially in summer, he always made the village of San Ildefonso his main residence. Awa Tsireh died tragically from exposure on the outskirts of San Ildefonso on March 29, 1955. He was memorialized a few months later by the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe with an exhibit of forty-three examples of his paintings.

The foregoing was derived from our book

Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry: Artists, Traders, Guilds, and the Government

Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry: Artists, Traders, Guilds, and the Government

Porch of Garden of the Gods Trading Post ca 1930s

June 21, 2016

The Definitive Hallmark Reference Guide (and why you should own it)

Dear American Indian Jewelry Enthusiast,

Before you think to yourself, “Should I invest in another hallmark book?” consider that all of us—dealers, collectors and researchers alike—have been waiting a long time (actually, forever) for a reliable, accurate and comprehensive identification guide to the hallmarks used by Native American silversmiths (as well as by those who work in similar styles of jewelry). That day has finally arrived with the publication of the Third Edition of Native American and Southwestern Silver Hallmarks, by Bille Hougart, and Pat and I can’t recommend this book highly enough.

This edition not only includes over 500 new entries but also corrects previously published errors and long-held misbeliefs as well as properly identifies the hallmarks of many of the most important silversmiths who ever worked. For instance, the correct hallmarks will now be found under the listings for Ambrose Roanhorse and Ambrose Lincoln, Dan Simplicio and John Silver, Homer Vance, and Fred and Frank Peshlakai. There are also significant corrections to the entries for Austin, Ike and Katherine Wilson. Also note there are now separate entries for Garden of the Gods Trading Post and “The Indian” as Mr. Hougart was kind enough to include our most recent research into these two establishments. And while many of the marks used by Navajo silversmiths who worked for C.G. Wallace remain to be adequately identified their treatment in this volume allows for future research.

But the book is more than an identification guide as there is also considerable information about the IACB silver stamping program, guilds, traders and trader’s organizations; plus information on shop stamps and manufacturers of machine made “Indian style” jewelry.

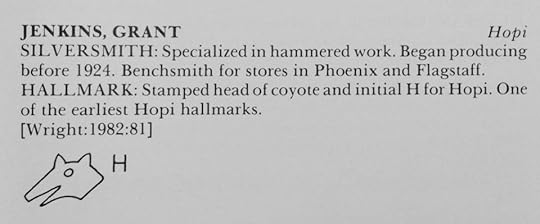

Back in 1972 when Margaret Wright published Hopi Silver: The History and Hallmarks of Hopi Silversmithing it was the first book to depict hallmarks used by any group of Indian silversmiths (in this case by Hopi smiths). At that time there was no other way to depict the hallmarks than by using hand drawn illustrations. When Barton Wright’s Hallmarks of the Southwest was published in 1989 it included hallmarks of all southwest silversmiths regardless of tribal affiliation, and also utilized hand drawn depictions of the hallmarks. And even though the second revised edition (published in 2000) is still used as a primary resource, since it is now over fifteen years old, and much new information has come to light in those fifteen years, it has proven to be sorely out of date.

Advances in digital photography and printing technology have facilitated the use of actual photographs of the hallmarks versus the drawings used in older publications. For instance, when Barton Wright drew this mark for Grant Jenkins he successfully rendered the general idea of a coyote head in profile with two ears, an eye and slightly open mouth:

However the actual hallmark is significantly different, as these images of two versions of Grant Jenkins’ hallmark illustrate.

As these examples confirm, images of the actual hallmarks make for accurate attributions, less confusion and fewer debates. Since Mr. Hougart’s first edition, The Little Book of Marks on Southwestern Silver: Silversmiths, Designers, Guilds and Traders, he has incorporated images of hallmarks in his identification guides, making them valuable references. And this edition, with its upgraded paper choice and use of digital printing, affords the clearest images of the hallmarks yet.

Mr. Hougart continues to research and update the hallmark database, employing all available hallmark resources (see previous blog post Reassessing Native American Hallmark Books), plus a multitude of other references as evidenced by his extensive bibliography. Consequently this third edition is by far the most accurate, reliable and comprehensive hallmark identification guide ever published.

So, yes, dear reader, you really do need to own this book, and use it exclusively, putting all previous hallmark guides away for old time’s sake.

Full disclosure: Pat and I were pleased to contribute our entire hallmark database to Mr. Hougart’s research and honored to be asked to participate in the editing process as well.

May 29, 2016

Hopi Pottery Tiles sold by Fred Harvey Company

Co-Curators Diana Pardue and Kathleen Howard

Pat and I have been thinking again about the Hopi tiles sold by the Fred Harvey Company in the early twentieth century.

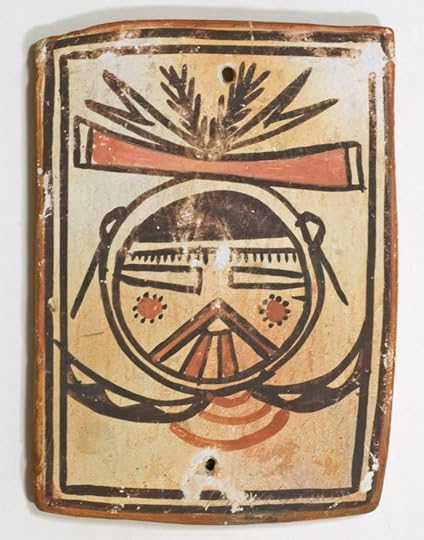

Rectangular Hopi tile, ca 1890-1910, with kachina mask design

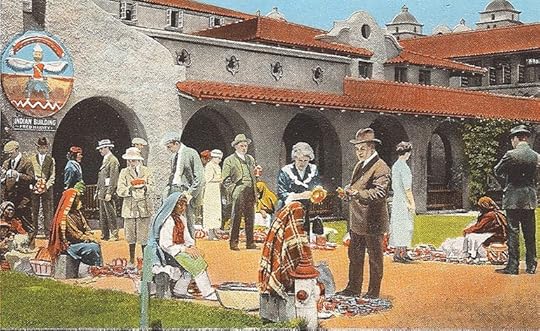

The Fred Harvey Company established the Indian Department in 1902, headquartered in the Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque, as a museum and showroom, with the intent of promoting and selling Indian handmade goods in its chain of lodges, shops, and restaurants at locations throughout the West.

Outside the Indian Building of the Alvarado Hotel, Pueblo potters sold their wares to guests and train passengers

The Indian Department also wholesaled Indian-made crafts to dealers and curio shops in the east. By the first decade of the twentieth century the Fred Harvey Company had become the largest distributor of high-quality Indian arts in the United States.

Rectangular Hopi tile, ca 1890s with full-bodied kachina design. The streaky yellow color is the result of a coat of varnish applied by a previous owner.

From the 1900s to the 1930s the Harvey Company was also the biggest outlet for Hopi tiles. In a 1963 Plateau article titled “The Fred Harvey Collection 1899-1963”, Byron Harvey III, great-grandson of founder Fred Harvey, referred to the Harvey Company's inventory when he wrote, "C.L. Owen obtained Hopi pottery from his residence in Toreva in 1913 and included tiles and flower pots. A letter, written in 1921, estimated that the company still had over 2,700 of these Hopi tiles."

Hexagonal Hopi tiles, ca 1890, may have been made by only a handful of Hopi potters

The tiles sold through the Harvey Company came in only three shapes: square, rectangle and hexagon. They exhibit signs of being nearly mass-produced, many showing hurried manufacture resulting in poor quality, and they were marketed primarily to tourists. Thousands of tiles were made between 1895 and 1930, and nearly every institution with an inventory of Hopi pottery—such as the Heard Museum, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Denver Art Museum and the Brooklyn Museum—has one or more tiles with the ubiquitous Harvey Company sticker, FROM THE HOPI VILLAGES, attached to the back.

Though the Harvey Company sold the majority of these tiles (hence they are commonly termed “Fred Harvey tiles”), it is important to note that the company was not permitted to purchase directly from the Hopi until 1910, when Herman Schweizer, head of the Indian Department, was given permission by the government superintendent of the reservation. Until that time Harvey Company had obtained all Hopi crafts through reservation traders, especially Thomas Keam, although these traders did not sell solely to Fred Harvey.

Square Hopi tiles with kachina mask designs, measuring 3-3/8” square, ca 1890-1910

The most common of these tiles are square in shape with the painted design of kachina masks. These tiles were made continuously for about thirty years, and vary minimally in size-typically 3-3/8” inches in height and width-this uniformity may indicate that molds were used in their production.

The painted designs were formulaic: most often two thin lines outline a single kachina mask. Perhaps ninety percent of Harvey tiles are decorated with kachina masks, as kachinas lent an exotic air while portraying tradition and authenticity to potential buyers, who were mostly tourists from the east unfamiliar with Indian pottery.

Most of the kachina masks are unidentifiable and fall into a category of fanciful depictions that are either conglomerations of various kachinas or otherwise altered masks. When actual masks are portrayed they are most often of Palhik Mana (Butterfly Maiden), Wakas (cow), Kipok (warrior), Koshare (Hano clown) or Qoqoqle (often referred to as the “Santa Claus” kachina). The Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe has eighteen of these tiles in their collection, nine of which were originally shipped by trader Charles L. Owen from Toreva, Arizona to the Fred Harvey Company in 1913.

Hopi tiles were very popular, reaching their heyday in the first years of the twentieth century and peaking in the 1920s.

The Harvey Label

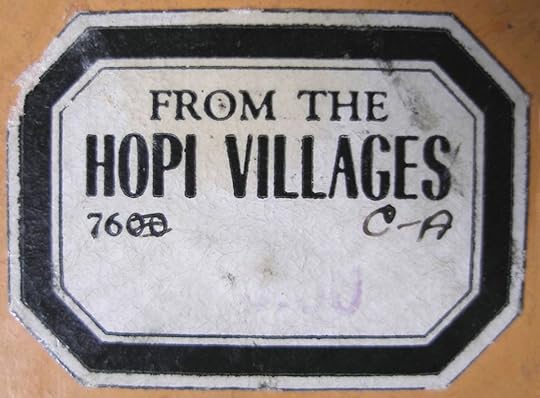

Back of Hopi tile with Fred Harvey label, ca 1890-1900

Byron Harvey III also discussed the “Fred Harvey label,” used by the Harvey Company in his 1963 article for Plateau. He reported that it was still in use at that time, and that the labels were intended as price stickers, as well as identifiers of origin, and cost codes were also recorded on them. The original label was rectangular with clipped edges, had a black border and measured approximately one inch by three-quarters of an inch in size.

Typical label used by Fred Harvey Company on Hopi pottery.

The typeface changed, presumably in the 1920s, to a sleeker Art Deco style, and a white outer border was added at the same time.

Less commonly seen variation of the Harvey label, ca 1920s

The most common label used was FROM THE HOPI VILLAGES, and it appeared on most Hopi pottery plus some kachina dolls sold through company stores. There were labels for other tribal affiliations-for example, “From the Pueblo of Santa Clara”. The stickers were used primarily from the 1900s to the 1930s and are less commonly seen on articles dating from the 1940s to the 1960s, perhaps reflecting the diminishing quantity of Indian crafts sold through the company after the 1930s.

The foregoing was derived from our book

Hopi & Pueblo Tiles: An Illustrated History

Hopi & Pueblo Tiles: An Illustrated History April 3, 2016

Roanhorse and Lincoln: Two Very Different Ambroses

Since the publication of Hallmarks of the Southwest in 1989 Ambrose Lincoln and Ambrose Roanhorse have been unfortunately described as the same person, which has caused their jewelry to be misidentified for decades. In fact, they were two distinctly different individuals. Although both were Navajo silversmiths, Lincoln was more than a decade younger than Roanhorse and worked in a different style.

So how did this happen?

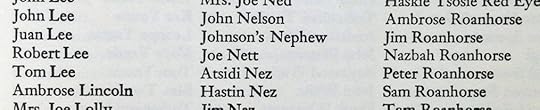

In the beginning Ambrose Lincoln and Ambrose Roanhorse were listed separately, and on the same page, in the appendix of Navajo silversmiths working in 1940 in John Adair’s book The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths:

In 1980 Mark Bahti published Collecting Southwestern Native American Jewelry, and incorporated an appendix of hallmarks for many prominent Native American silversmiths. He included the mark for Ambrose Lincoln:

But something went wrong during Barton Wright's research for Hallmarks of the Southwest and he wasn’t able to discern that Roanhorse and Lincoln were two different people:

Barton Wright made no corrections and continued to confuse the two Ambrose’s in the second edition of Hallmarks of the Southwest.

Wright’s entry of Roanhorse and/or Lincoln was debated among dealers and collectors for years, with the conclusion that they must have been two different silversmiths. Unfortunately once something appears in print it is then considered gospel and nearly impossible to correct.

Jonathan Batkin divulged much biographical information about Ambrose Roanhorse in his 2008 publication The Native American Curio Trade In New Mexico, also observing that John Adair’s field notes of 1940 identified Ambrose Lincoln as working at Zuni, and provided irrefutable evidence Roanhorse and Lincoln were not the same person.

Still the question remained, did Roanhorse sign with the A-in-keystone hallmark? If not, then how did he hallmark his work? The problem was solved when California Academy of Sciences made their collections database available via the Internet. CAS is in possession of the Elkus Collection, one of the most thoroughly documented collections of Indian art from the 1940s/50s era. In the collection are ten pieces of Roanhorse’s jewelry, three of which are hallmarked, here is a link to the items in their collection.

http://researcharchive.calacademy.org...

Once representative pieces of work with both hallmarks could be compared side-by-side it didn’t take much to figure out the rightful owner of each hallmark.

It is now abundantly apparent that Ambrose Roanhorse used a stick figure of a horse with his initials AR forming the legs…  courtesy Karen Sires

courtesy Karen Sires

and that Ambrose Lincoln signed his work with a capital A inside a keystone shaped design.  courtesy Karen Sires

courtesy Karen Sires

To further the argument, below are signed pieces of work by both men and a discussion of their styles and skills.

Ambrose Roanhorse was one of the most influential Navajo silversmiths of his time and became famous for hand wrought, traditional old style Navajo silver. When he used stone settings they usually consisted of one large stone set in the center of the piece. He was considered a master of his craft and won many awards for his hand wrought work; his plain silver concho belt took a first place ribbon at the 1956 Gallup Ceremonial. His work was highly prized and compared favorably alongside the highest quality master silversmiths of the time including Georg Jensen. While many pieces of his work do not bear his hallmark, they are distinctive for his use of bold, simple design and high quality of workmanship.

Here are two typical plain silver pieces made by Ambrose Roanhorse. Silver fabricated bracelet by Ambrose Roanhorse in the style known as “Indian School” for its simplicity and for evoking the early phases of Navajo silverwork. Courtesy Karen Sires

Silver fabricated bracelet by Ambrose Roanhorse in the style known as “Indian School” for its simplicity and for evoking the early phases of Navajo silverwork. Courtesy Karen Sires Silver concho pin by Ambrose Roanhorse. Courtesy Karen Sires

Silver concho pin by Ambrose Roanhorse. Courtesy Karen Sires

Ambrose Lincoln, on the other hand, worked in the Gallup/Zuni area for C.G. Wallace and Charles Kelsey, among others, and most commonly produced cast silver pieces, often with turquoise channel inlay. At the 1956 Gallup Ceremonial, mentioned earlier in connection with Roanhorse, Lincoln won a second place grand prize for a bracelet with channel work inlay that was a collaboration with Zuni lapidarist Lambert Homer; thus establishing that Lincoln was an excellent silversmith in his own right.

Illustrated below are two pieces by Ambrose Lincoln. Necklace by Ambrose Lincoln with sand cast Yei figures and Zuni turquoise channel inlay. Courtesy Karen Sires

Necklace by Ambrose Lincoln with sand cast Yei figures and Zuni turquoise channel inlay. Courtesy Karen Sires Fabricated bracelet by Ambrose Lincoln, with turquoise settings. Courtesy Karen Sires

Fabricated bracelet by Ambrose Lincoln, with turquoise settings. Courtesy Karen Sires

So, as we made clear in Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry, Lincoln’s jewelry, though good, should not be mistaken for Roanhorse’s (who was considered a master silversmith) nor should it command the same value as Roanhorse’s.

Following are short biographies of Roanhorse and Lincoln, more information is available in Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry.

Ambrose Roanhorse

Ambrose Roanhorse was born about 1904 near Ganado, Arizona and started learning silverwork at the age of nine by helping his grandfather, the famed early silversmith Peshlakai. Roanhorse moved to Santa Fe about 1928 where he worked at Southwest Arts and Crafts as a silversmith. He was hired as the first instructor for the silversmithing classes at the Santa Fe Indian School, where he taught hand forging methods from 1931 to 1939.

In 1936 Roanhorse became involved with the Indian Arts and Crafts Board’s program for promoting (and hallmarking) hand made Indian jewelry and in turn became Kenneth Chapman’s assistant, inspecting and stamping the jewelry that was submitted.

In 1939 Roanhorse was selected as director of the Wingate Guild, and left Santa Fe for the headquarters at the Wingate Vocational School. In 1941 the guild expanded to become the Navajo Arts and Crafts Guild, where he served as assistant manager for a few years.

In 1954 Roanhorse was one of twelve American Indian artists honored (additionally Dorothy Dunn Kramer, an Anglo art teacher was honored) by the French government, awarded with the Ordre des Palmes Académiques, the French Republic Award for his distinguished achievements in silver work.

After retirement from the Bureau of Indian Affairs he continued to teach silversmithing at various venues. Roanhorse passed away in 1982 and is buried in St. Michael’s, AZ.

Ambrose Lincoln

Ambrose Lincoln was born in 1917, and graduated from Wingate Vocational High School in 1939, the term before Roanhorse became an instructor there. Ironically, Lincoln worked as the silversmithing instructor at Santa Fe Indian School in 1942, three years after Roanhorse left the position to work with the Navajo Guild.

Lincoln worked primarily in the Zuni and Gallup areas, in the 1940s for C.G. Wallace and Charles Kelsey.

Ambrose Lincoln died in 1989 and is buried in Gallup, NM.

Update June 2016: These hallmarks have been properly identified in the third edition of Bille Hougart's  Native American and Southwestern Silver Hallmarks.

Native American and Southwestern Silver Hallmarks.

March 15, 2016

Considering the Hallmark for Hopi silversmith Homer Vance

Reference guides devoted solely to hallmark identification, with a paragraph or less of biographical information, and no illustrations of typical jewelry made by the artist, are just that—guides to identification. Experience, perspective and logic are also required to make accurate attributions.

For instance, let's consider the hallmark for Hopi silversmith Homer Vance.

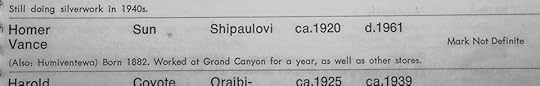

Little was known of Homer Vance when Margaret Wright conducted her research prior to 1972 for Hopi Silver: The History and Hallmarks of Hopi Silversmithing since Vance had died in 1961. Her sources of information for Vance's hallmark entry were limited and included a survey of Hopi silversmiths conducted in 1941 by Alfred Whiting for the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, John Adair’s 1944 book The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths, and the Hopi Silver Project conducted by the Museum of Northern Arizona in 1938/1939. Wright listed Vance's mark as "Not Definite," indicating she knew he had a hallmark, but was unable to corroborate it. Here is the entry from the Third Edition of Hopi Silver:

By the time Barton Wright published Hallmarks of the Southwest in 1989 his research had revealed that Vance's hallmark consisted of "Stamped initials in Gothic print," suggesting a typeface that includes serifs, such as Times New Roman. However, the publisher chose to illustrate the mark with a sans-serif style, here is the actual entry from the book:

This unfortunate choice of fonts by Schiffer Publishing has caused considerable confusion ever since.

The Wrights discovered that Homer Vance was born into the Sun Clan in 1882 at Shipaulovi, started working silver around 1920, worked at various stores, including at the Grand Canyon for a year, and passed away in 1961.

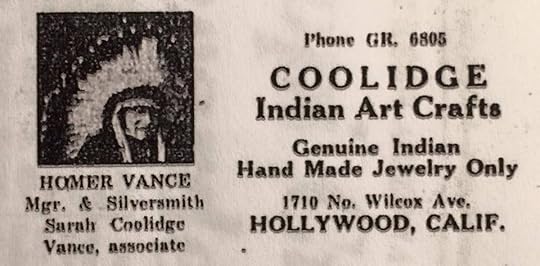

Additionally, during our research we found Vance worked as an actor in western films, was employed as a silversmith in 1927 at R.M. Bruchman’s in Winslow, ran the shop Coolidge Indian Arts in Hollywood with his wife Sarah Coolidge until 1938 and demonstrated silver at the Golden Gate Exposition in 1939. Here is a 1936 advertisement for Coolidge Indian Arts:

So, from the foregoing information what kind of jewelry could one logically speculate Vance created during his career? First, think about the style of jewelry prevalent in the 1930s, especially in locations catering to tourists, such as the Grand Canyon and Hollywood; consider the jewelry made in the 1930s by Hopi silversmiths working in urban areas, such as Morris Robinson and Ralph Tawangyawma. It would most likely be typical tourist-style jewelry, with stamp work filling the empty silver spaces; perhaps a delicate bracelet for a woman’s wrist, with a turquoise setting on top of a split shank band. Something that looked Navajo and appealed to tourists.

Something like this:

Which happens to be hallmarked like this:

Hallmark used by Homer Vance

Hallmark used by Homer Vance

Considering this hallmark consists of the correct initials for Homer Vance, and the font is consistent with the time period (reference the H most often used by Ralph Tawangyawma), as well as the crescent mark above the initials that could easily represent the sun (for his clan), then this is the hallmark used by Homer Vance.

Yet a search of the Internet for “homer vance hopi” results in images of pins, pendants and belt buckles made in this style:

These pieces are typically 1970s in materials and construction, the large cluster work and wide sawtooth bezels are indicative of Navajo work, though it could also be Zuni. And they are hallmarked like this: Hallmark used by an unknown Navajo or Zuni silversmith in the 1970s

Hallmark used by an unknown Navajo or Zuni silversmith in the 1970s

It's not difficult to see how the entry for Homer Vance in Hallmarks of the Southwest has caused this erroneous identification, nor why dealers adhere to this attribution; except that Homer Vance was dead by the time these pieces were made.

Is it realistic to believe that a Hopi silversmith who worked during the height of the tourist era, and died in 1961, would have made Zuni style cluster work prevalent in the 1970s? No, it is not. And it is time to set the record straight. This hallmark was used by a Navajo or Zuni silversmith working in the 1970s, who has yet to be identified. It's understandable how this hallmark could be credited to Homer Vance if the hallmark alone is used for identification, but much more difficult to justify the attribution once the style of jewelry is considered.

Just because pieces are signed HV does not mean they were made by Homer Vance. Just as not everything marked FP was made by Fred Peshlakai or Frank Patania. The lack of the identification of another silversmith who may have used these initials does not mean Homer Vance was the only Indian silversmith who ever used the initials HV as a hallmark.

A hallmark with no other information about the jewelry it is applied to is only a mark within a blank canvas, especially something as vague as initials, and there is nothing to guide in determining the maker without knowing the technical achievements of the artist. Though it may appear some hallmarks are self-explanatory, consider that they may be fakes, or they may have been used by someone else (perhaps even a relative) after the death of the silversmith.

For these reasons it should be cautioned that accurate attributions can only be made when the style and quality of the jewelry is considered along with the hallmark.

Update June 2016 - The third edition of Bille Hougart's Native American and Southwestern Silver Hallmarks has corrected the hallmark for Homer Vance.

December 27, 2015

In Defense of Barton Wright

Foremost among the points that must be kept in mind is the fact that this is not an exhaustive work but one, it is hoped, to which additional information may be added. Secondly the fact that there are errors in the data is fully recognized. However the impossibility of removing such errata is apparent when it may require a year to check out a single mark. The elimination of these mistakes requires the cooperation of craftsmen and those who work with them.

He not only understood, but recognized, that the research he conducted in the 1970s and 1980s would be built upon and corrected in the future. Yet, he continues to be criticized for those very errors.

The limitations in the scope and methodology of study available to Barton at the time of his research should be taken into consideration when judging the accuracy of his publications. Barton, and Margaret Wright in her own jewelry book Hopi Silver: The History and Hallmarks of Hopi Silversmithing, did their research the hard way, before computers, the Internet or digital cameras. The work was long and painstaking back then.

I admit it's difficult for contemporary readers to comprehend the enormous task of constructing the original hallmark database in a pre-digital age. It's also hard to think back to the time before the publication of any book containing hallmarks of Indian jewelry—as more than forty years have passed since the first printing of Hopi Silver—and how it would be nearly impossible today to reconstruct that data if it had not been recorded when it was. Where would the knowledge of southwestern Indian jewelry be now if it weren't for the record of hallmarks that Barton compiled and published more than twenty-five years ago in Hallmarks of the Southwest? His work laid a foundation for further research and started dialogs that we all—collectors, dealers and academics—continue to this day.

It's easy for people to criticize publications when they haven't been through the rigors and sacrifices required to publish a book. I often think of a note that Barton wrote to Pat and I, shortly before the publication of the tile book, where he stated, "I'm so pleased you are nearing your goal of a published book. I still think people who write books are masochists! And I suspect you will agree." I am only now gaining a full appreciation for his use of the term masochist as we feel the occasional jab of criticism and controversy over our own hallmark book.

And it's just not in the jewelry groups that I see people disrespecting Barton, it's in the kachina groups as well. I am not aware why kachina collectors feel the need to criticize his books; he only spent a lifetime studying, writing about and befriending the Hopi people. Some Hopis, such as Ross Josyesva, Jimmy Kewanwytewa's stepson, believe that, "Barton knew more about Kachinas than most Hopis.” Barton's Hopi Kachinas: The Complete Guide to Collecting Kachina Dolls, published in 1977, was the first book to focus on identifying and collecting kachina carvings. What reference would collectors and dealers use if it weren’t for this book and the others that Barton published in his lifetime?

I find it not merely disrespectful, but arrogant and rude to refer to a scholar who was considered the foremost authority on Hopi culture and kachinas in his lifetime as “Barton Wrong,” especially now that he isn’t here to defend his work.

A Tribute

Barton Wright 2002

Barton Wright 2002 Barton Allen Wright was born in Bisbee, Arizona in 1920 to Roy and Anna Wright; Roy was a miner and the family moved often while Barton was young. They eventually settled in Mohave County where he graduated from Kingman High School. Barton acquired a vast knowledge of northwestern Arizona, and held a pilot's license for the Colorado River; from 1940 to 1942 he and a friend ran the ferry at the site that would become Davis Dam.

During World War II Barton served in the Army, seeing combat on New Guinea and in the Philippines. After returning home he married Margaret Nickelson and they raised two children. Also after the war, he graduated from the University of Arizona, trained in archaeology and anthropology. His Masters Thesis was on Catclaw Cave on the Colorado River, a site he dug in 1949 with his new wife Margaret and two friends. He then began his career as an artist for Arizona State Museum.

In the early 1950s Barton worked as the archaeologist at Town Creek Indian Mound State Park in Mt. Gilead, North Carolina, and later for the Amerind Foundation at an excavation near Tumacacori. The Wrights moved to Flagstaff in 1955 when Barton became curator of the Museum of Northern Arizona. In 1977 the Museum of Man, in San Diego’s Balboa Park, recruited him as the Director of Scientific Research. Retirement beckoned and six years later Barton and Margaret moved to Phoenix where he continued to research and write about the southwest.

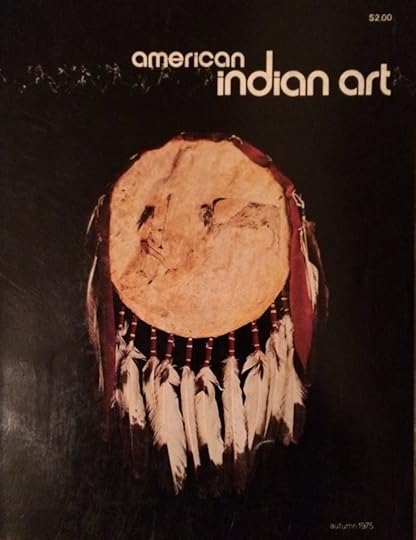

Among his many accomplishments was a body of published work of over twenty books and numerous articles that he wrote or contributed to, as well as serving on the Editorial Advisory Board of American Indian Art magazine from it's inception in 1974 until his death in 2011.

Barton was a long time student of southwestern Indian history, especially interested in the Hopi people and their religion. He was a talented painter and graphic artist who illustrated many of his own publications as well as those of other authors. He was a patient and kind mentor, never once doubting that Pat and I would contribute to the field of American Indian art, lack of academic degrees notwithstanding.

*Thanks to Alan Ferg for much of the biographical info above, some of which was published in Catclaw Cave.

See previous blog post for a listing of published works by Barton Wright.

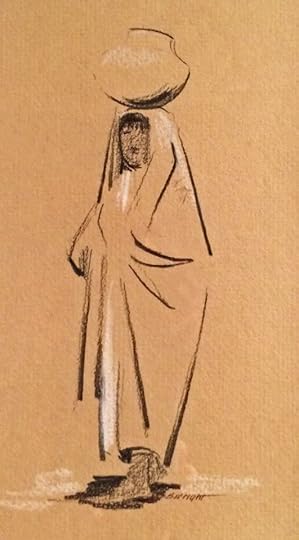

Charcoal sketch of pueblo water carrier by Barton Wright

Oil painting, "The Quiet Plaza" by Barton Wright

Drawing of Patusunqola, one of the four chiefs of direction, by Barton Wright (signed "Tizme" as a private joke)

Scratchboard by Barton Wright

Published Works of Barton Wright

Books

1962 - This is a Hopi Kachina, with Evelyn Roat. Flagstaff: Museum of Northern Arizona

1973 - Kachinas: A Hopi Artist's Documentary, illustrated by Cliff Bahnimptewa. Flagstaff: Northland Press, and Phoenix: Heard Museum

1974 - Nampeyo, Hopi Potter: Her Artistry and Her Legacy, exhibition catalog. Fullerton: Muckenthaler Cultural Center

1975 - Kachinas: The Barry Goldwater Collection at the Heard Museum, with Barry Goldwater and photographs by Jerry Jacka. Phoenix: W. A. Krueger Company and Heard Museum

1975 - The Unchanging Hopi: An Artist's Interpretation In Scratchboard Drawings And Text. Flagstaff: Northland Press

1976 - Pueblo Shields from the Fred Harvey Fine Arts Collection. Flagstaff: Northland Press

1977 -

Hopi Kachinas: The Complete Guide to Collecting Kachina Dolls. Flagstaff: Northland Publishing

Hopi Kachinas: The Complete Guide to Collecting Kachina Dolls. Flagstaff: Northland Publishing1979 - Hopi Material Culture: Artifacts Gathered by H. R. Voth in the Fred Harvey Collection. Flagstaff: Northland Press and Phoenix: Heard Museum

1982 - Year of the Hopi: Paintings and Photographs By Joseph Mora, 1904-1906, with Tyrone Stewart, Frederick Dockstader. New York: Rizzoli International Publications.

1986 - The Hopi Photographs: Kate Cory, 1905-1912, with Marnie Gaede & Marc Gaede. La Canada: Chaco Press

1986 - Kachinas of the Zuni. Flagstaff: Northland Press

1988 - Patterns and Sources of Zuni Kachinas, with Bill Harmsen and Clara Lee Tanner, illustrated by Reese Koontz. Denver: The Harmsen Publishing Company

1988 -  The Mythic World Of The Zuni, Frank Hamilton Cushing, edited and illustrated by Barton Wright. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press

The Mythic World Of The Zuni, Frank Hamilton Cushing, edited and illustrated by Barton Wright. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press

1989 -  Hallmarks of the Southwest, in cooperation with the Indian Arts and Crafts Association. Atglen: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd

Hallmarks of the Southwest, in cooperation with the Indian Arts and Crafts Association. Atglen: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd

1991 -  Kachinas: A Hopi Artist's Documentary, illustrated by Cliff Bahnimptewa. Flagstaff, Northland Publishing, reprint of first published in 1973.

Kachinas: A Hopi Artist's Documentary, illustrated by Cliff Bahnimptewa. Flagstaff, Northland Publishing, reprint of first published in 1973.

1994 - Kachina: poupees rituelles des Indiens Hopi et Zuni, exhibition catalog, 30 juin-2 octobre 1994, with Marie-Elizabeth Laniel-Le François, and others. Marseille: Musées de Marseille

1994 -  Clowns of the Hopi: Tradition Keepers and Delight Makers, photographs by Jerry Jacka. Flagstaff: Northland Publishing

Clowns of the Hopi: Tradition Keepers and Delight Makers, photographs by Jerry Jacka. Flagstaff: Northland Publishing

1994 -  Enduring Traditions: Art of the Navajo, with Lois Essary Jacka and illustrated by Jerry Jacka. Flagstaff: Northland Publishing

Enduring Traditions: Art of the Navajo, with Lois Essary Jacka and illustrated by Jerry Jacka. Flagstaff: Northland Publishing

1997 - Pueblo Cultures, Iconography of Religions. Leiden: Brill Academic Pub

2000 –  Hallmarks of the Southwest, Revised & Expanded 2nd Edition. Atglen: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd

Hallmarks of the Southwest, Revised & Expanded 2nd Edition. Atglen: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd

2003 - Esprit Kachina: Poupees, Mythes et Ceremonies Chez les Indiens Hope et Zuni. (Kachina Spirit: Dolls, Myths and Ceremonies of the Hopi and Zuni Indians). with Pierre Amrouche, Nathalie Rheims, Francine Ndiaye, Paris: Galerie Flak.

2006 -  Classic Hopi and Zuni Kachina Figures, photographs by Andrea Portago, includes “Pueblo Cultures, An Essay” by the author. Albuquerque: Museum of New Mexico Press

Classic Hopi and Zuni Kachina Figures, photographs by Andrea Portago, includes “Pueblo Cultures, An Essay” by the author. Albuquerque: Museum of New Mexico Press

2007 -

Hopi & Pueblo Tiles: An Illustrated History, Kim Messier and Pat Messier, Foreword by Barton Wright. Tucson: Rio Nuevo Publishers.

2008 - Catclaw Cave, Lower Colorado River, Arizona, edited by Alan Ferg. Tucson: Arizona Archaeological Society; The Arizona Archaeologist No 37.

2014 -

Kachinas: A Hopi Artist's Documentary, paintings by Clifford Bahnimptewa, foreword by Ann Marshall. Albuquerque: Museum of New Mexico Press, reprint of first published in 1973.

Articles

1950 – “The Zanardelli Site, Arizona BB:13:12”, in The Kiva Vol 16, No 3, with Rex E. Gerald, The Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society

1956 – “A New Pleistocene Bighorn Sheep From Arizona”, with Claude W. Hibbard, in Journal of Mammalogy, Vol 37, No 1

1975 – “Hopi Kachina – Feather Controversy” in Ray Manley’s Southwestern Indian Arts and Crafts, Tucson: Ray Manley Photography

1976 - "Anasazi Murals", American Indian Art, Vol 1, No 2

1976 – “Kachinas” in Arizona Highways Indian Arts and Crafts, Clara Lee Tanner, ed. Phoenix: Arizona Highways

1976 - "Tabletas, A Pueblo Art", American Indian Art, Vol 1, No 3

1977 – “Hopi Tiles”, American Indian Art, Vol 2, No 4

1979 - Book review of Hopi Painting: The World of the Hopis by Patricia Janis Broder, American Indian Art, Vol 4, no 4

1980 - “Museum Collection: San Diego Museum of Man”, American Indian Art, Vol 5, No 4

1982 - Book review of Southwestern Indian Ritual Drama, edited by Charlotte J. Frisbie, American Indian Art, Vol 7, No 2

1984 – “Kachina Carvings”, American Indian Art, Vol 9, No 2

1991 – “Initials, Symbols and Secret Codes”, Inter-Tribal America, Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial

1992 – “Pueblo Shields”, American Indian Art, Vol 17, No 2

1995 - "Clifford Bahnimptewa", American Indian Art, Vol 21, No 1

1995 – “Muriel Navasie,” American Indian Art, Vol 21, No 1

2008 - "Hopi Kachinas: A Life Force" in Hopi Nation: Essays on Indigenous Art, Culture, History and Law, edited by Edna Glenn, John R. Wunder, Willard Hughes Rollings, and C. L. Martin. Lincoln: UNL Digital Commons.

As Illustrator

1959 - Master of the Moving Sea: The Life of Captain Peter John Riber Mathieson, from his Anecdotes, Manuscripts, Notes, Stories and Detailed Records, Gladys M. O. Gowlland. Flagstaff: J. F. Colton & Co.

1960 - Throw Stone, The First American Boy 25,000 Years Ago, E.B. Sayles and Mary Ellen Stevens. Chicago: Reilly & Lee Co.

1960 - Column South: With the 15th Pennsylvania Cavalry, Suzanne Colton Wilson. Flagstaff: J.F. Colton & Co.

1962 - Little Cloud and the Great Plains Hunters 15,000 Years Ago, Mary Ellen Stevens and E.B. Sayles. Chicago: Reilly & Lee Books

1962 - Seed Plants of Wupatki and Sunset Crater National Monuments with Keys for the Identification of Species, W. B. McDougall, Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin No 37. Flagstaff: Northern Arizona Society of Science and Art

1964 - Grand Canyon Wild Flowers, W.B. McDougall., Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin No 43. Flagstaff: Northern Arizona Society of Science and Art

1968 - The Age Of Dinosaurs In Northern Arizona, William J. Breed. Flagstaff: Museum of Northern Arizona

1974 -  Hopi Silver: The History and Hallmarks of Hopi Silversmithing,

Hopi Silver: The History and Hallmarks of Hopi Silversmithing,

Margaret Wright. Flagstaff: Northland Press.

1980 - Rivers of Remembrance, Diego Pérez de Luxán, Marilyn Francis. Quality Publications.

Discussed in

1995 -

Town Creek Indian Mound: A Native American Legacy, Joffre Lanning Coe. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press

July 10, 2015

The End of an Era

Nine years later I made my first serious purchase of antique Indian art, a Hopi wedding basket from the 1920s, at an antique fair in Glendale, California (for $50, a bargain even back then, and a basket which is still in the collection, by the way). As Indian art grew from an interest, into a full-blown obsession, I became aware of the magazine. It was full of ads from prominent dealers and fascinating articles on things I could only dream of owning; I was enthralled well before I came to realize the significance of the articles and their authors. Pat and I subscribed and then searched for the back issues we did not have. I looked forward to every issue, it became an accomplice of my addiction, like the spoon that held the heroin.

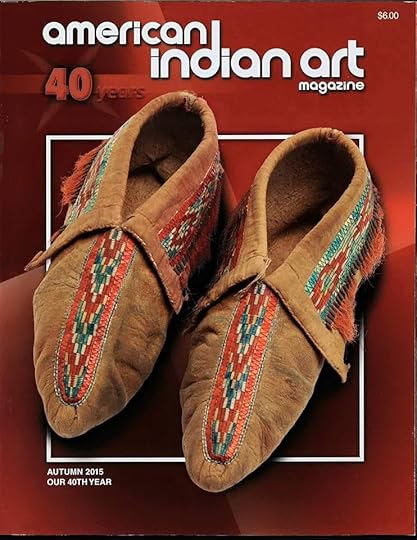

Now American Indian Art magazine has announced it's final issue will be published in August, after 40 years of quarterly publications, 160 issues in all. I will miss it with every fiber of my being.

For me, whose particular passion is historic southwestern art and the tourist era 1880-1940, there was always something to read and discuss in each issue, whether it was legal (NAGPRA) updates, book reviews or even the dealer’s ads. I also liked how professional it was, how it artfully walked the line between academia and popular writing; how, like no other periodical, it focused on antique Indian art (but not exclusively).

It could be said that American Indian Art introduced us to Barton and Margaret Wright, literally. If we had not devoured Barton's article "Hopi Tiles", especially the bibliography, in the Autumn 1977 issue then Pat would not have contacted Barton to ask where we could obtain Suzanne Love's master's thesis "Hopi Tiles". In his gracious manner, Barton invited us to their home and allowed us to have a copy made of his personal copy of the thesis; this was the beginning of perhaps the most influential friendship in our lives, and one that would lead us to our own publishing adventures.

We never did figure out why a Zia tile was the leading image of the article…

It was one of my great desires to be published in American Indian Art. We actually had a brilliant idea, one that likely would have passed the prestigious editorial advisory board, but the timing was bad so we declined to move forward for professional and personal reasons. Now that dream has come to an end.

After August 1, 2015 there will be no more articles about historic Pueblo pottery, or Navajo weavings, katsina dolls, southwestern jewelry, Navajo horse trappings, Apache playing cards, Plains beadwork, California basketry, or hundreds of other aspects of American Indian art. Will these articles find a new venue or be relegated to obscure anthropology journals?

Publisher Mary Hamilton and staff (shout out to editor Tobi Lopez Taylor), should be congratulated for forty years of publishing success. But I’m too heartbroken to extend any other accolades. I have never known a time during my collecting/researching/publishing avocation that did not include American Indian Art magazine. Will there ever be another periodical to fill the very large void being left behind?

April 13, 2015

Overlay is Not Always Hopi Made

Overlay is a technique where two pieces of silver are soldered together after a design has been cut from the top layer. In the final phase of construction the bottom layer is blackened with a chemical agent allowing the top design to stand out. Though not exclusive to the Hopi, they have become so proficient utilizing overlay in their unique style of jewelry that it is commonly thought they are the only ones who practice this technique.

However, since the 1950s silversmiths from other southwest tribal groups have produced overlay jewelry of their own style that is sometimes mistaken for the work of the Hopi.

Overlay as a technique for conveying traditional Hopi designs in silver originated in 1938 from drawings produced at the Museum of Northern Arizona and continued in Fred Kabotie’s silver designs for the World War II veterans classes held from 1947-1951; though overlay was only one of many techniques taught in the classes by instructor Paul Saufkie. In 1949 the Hopi Silvercraft Guild was formed and by the mid-1950s overlay was the only technique used by Guild silversmiths as the use of sheet silver became commonplace.

Overlay bracelets by (l-r) Paul Saufkie & Arthur Yowytewa, Wallie Sekayumptewa, and Douglas Holmes circa early 1950s.

After the success of the Hopi Guild jewelry, in the 1950s many other silversmiths and shops incorporated overlay in their designs. About 1951 trader Dean Kirk of Manuelito, New Mexico, designed a series of overlay pins to be made by Navajo smiths in his employ that incorporated Hohokam and Mimbres designs. A 1958 newspaper advertisement for the shop Enchanted Mesa of Albuquerque promoted “Dean Kirk’s Navajo Overlay Silver”.

Overlay pin featuring Hohokam pottery design made by Navajo silversmiths for trader Dean Kirk, 1950s.

Overlay pin featuring Hohokam pottery design made by Navajo silversmiths for trader Dean Kirk, 1950s.Also in the 1950s Woodard’s of Gallup adapted overlay designs used at the Hopi Guild and had them made into pins and earrings by Navajo silversmiths. One of their templates featured a Hopi water wave design and an area where one triangular turquoise stone would be set flush into one quadrant.

Right pin possibly made by a Pueblo silversmith. Left pin, unmarked, using Hopi Guild design, made by Navajo smith working at Woodard’s. All pieces circa 1950s.

Right pin possibly made by a Pueblo silversmith. Left pin, unmarked, using Hopi Guild design, made by Navajo smith working at Woodard’s. All pieces circa 1950s.One of the most recognizable designs to come out of the White Hogan shop in Scottsdale was a round overlay swirl design made into necklaces, bracelets, rings, and especially earrings. This swirl motif, originally adapted by Kenneth Begay from a design painted on a piece of Hohokam pottery, was reproduced by the owners of the shop for decades using mechanical casting techniques.

Swirl design earrings and pendant and maze design ring cast by White Hogan from overlay designs created by Kenneth Begay.

Swirl design earrings and pendant and maze design ring cast by White Hogan from overlay designs created by Kenneth Begay.Over the years many noted Indian silversmiths from various areas of the southwest incorporated the overlay technique into their designs, including Santiago Leo Coriz and Vidal Aragon both of Kewa (Santo Domingo) Pueblo and Joe H. Quintana of Cochiti. Willie Yazzie Sr. (Navajo) learned to make silver at Dean Kirk’s shop in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and afterwards made many pieces of overlay jewelry utilizing Navajo designs.

Overlay ram buckle by Hyson Craig (Navajo); bolo tie and mixed-metal wedding basket pin by Willie Yazzie Sr. (Navajo), all circa 1970s.

Overlay ram buckle by Hyson Craig (Navajo); bolo tie and mixed-metal wedding basket pin by Willie Yazzie Sr. (Navajo), all circa 1970s.Tohono O’odham silversmith Rick Manuel started experimenting in 1976 with the overlay technique, creating designs derived from his Southern Arizona desert home. His designs were so successful they have influenced other Tohono O’odham silversmiths, most notably James Fendenheim, who also works in the overlay technique.

Overlay jewelry made by Tohono O’odham silversmith Rick Manual.

Overlay jewelry made by Tohono O’odham silversmith Rick Manual.The best way to determine if a piece is made by a Hopi silversmith is to look for a hallmark, as Hopi overlay is always signed. From the 1950s it was signed with two marks, the artist’s personal mark and either the Hopi Guild sunface mark or the shop mark for Hopicrafts (which closed in 1983).

Overlay pieces circa early 1950s by Hopi silversmith Douglas Holmes signed with his Guild sunface mark and his personal mark of a butterfly.

Overlay pieces circa early 1950s by Hopi silversmith Douglas Holmes signed with his Guild sunface mark and his personal mark of a butterfly.But by the mid-1990s young Hopi silversmiths were learning from other sources and did not form a relationship with the Guild, so it is less likely for pieces to also display the Guild mark after that time. Navajo and Pueblo silversmiths also typically signed their work, however if no hallmark is present then the piece still might have been made by a Navajo or Pueblo silversmith in the 1950s or 1960s era, or possibly even by an Anglo silversmith (even though Anglo smiths were more likely to produce in the 1970s and often signed their work). It is nearly impossible to attribute unsigned overlay work.

It should be noted that overlay jewelry is especially easy to reproduce by various methods of mechanical casting, and sadly many pieces of Hopi and Navajo overlay have been reproduced through the years. If reproductions are made from original hand made pieces that incorporate hallmarks, those hallmarks will often appear faintly or illegibly on the back of the reproduction.