Sujata Massey's Blog, page 8

February 23, 2022

The Long-Buried History Inside Rishi Reddi’s PASSAGE WEST

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Rishi Reddi

Rishi ReddiI recently read an incredible novel: Passage West by Rishi Reddi. I fell hard for the small cast of sympathetic characters, Indian and Mexican immigrants in early 20th century America, and I yearned to know more from her about this mysterious part of American history. I’m sharing an interview that took place in a series of emails. Join me as I learn more about the history of Indian activism and the great sacrifices of early Punjabi immigrants to California.

Rishi, welcome to Murder is Everywhere, a blog that highlights the very best crime writing set in locations worldwide. The first thing I want to ask is about the origination of your idea to set Passage West in California’s Imperial Valley.

While taking a law school class about U.S. immigration, I learned that, during the 1920s, certain applicants’ racial classification as “white” was a pre-requisite for a path to citizenship. I grew very interested in a case called United States v. Thind. Mr. Thind was a Punjabi-born United States Army veteran who had gained his U.S. citizenship based on his military service. He was later stripped of his citizenship by the U.S. Supreme Court, which reasoned that although he was Caucasian, he was not considered “white” under popular belief and therefore his citizenship had been improperly granted. I was fascinated by the racial aspects of the court’s decision and also the fact that South Asians had immigrated to America so early—at the turn of the 20th century. I didn’t understand how much those early South Asians had contributed to American society. The population was mostly comprised of men living in bachelor-like conditions, trying to make a life for themselves in very isolating circumstances. Many who had settled in rural California found sweethearts among the Mexican population and earned reputations as very good farmers. They made friends among other immigrant groups and also earned the respect of American business associates. This was the real-life multi-cultural historical community I wanted to write about.

SS Minnesota, Seattle June 23, 1913, courtesy WA State Historical Society

SS Minnesota, Seattle June 23, 1913, courtesy WA State Historical SocietyFrom what I’ve read about the current situation in the Imperial Valley, a high number of its residents live in poverty and have limited access to health care. A few massive agri-business companies are the chief employers in this area north of Baja California, with Arizona on its eastern border. How did the location fit into the crimes you write about in your novel?

The crime is based on a true event. It is horrific but also understandable in some way. The act committed by one of the protagonists was sparked by how farming immigrants were being treated in the 1920s; how these families worked to develop agriculture in the Imperial Valley, yet were ultimately robbed of the profits of that hard work. The story is set in this specific time and place, but portrays nationwide social dynamics. I meant it to be a story about America itself.

How common was it for Asian immigrants to find themselves in “unsettled” parts of the United States?

It was very common! These “unsettled” areas allowed immigrants a certain amount of social freedom, away from the cultural constraints of mainstream, conventional American society. They were wanted and needed in areas where many privileged folks did not care to go. In Imperial Valley, many immigrants stayed through the severe heat of the summer in order to earn a livelihood, but many non-immigrant whites could leave during those months, even if they were not particularly privileged, to find work in cities and other more populated areas without the fear of being driven out through violent mobs or other ways.

Mexican gang labor in 1930s, by Dorothea Lange, courtesy Library of Congress

Mexican gang labor in 1930s, by Dorothea Lange, courtesy Library of CongressOne of the most startling things for me was the redefinition of race by the US government for Indian immigrants. What were the things they could—and could not do—because of laws based on national origin and color?

It was tricky to untangle all the ways that the Supreme Court rulings in those years defined the term “white,” and the way that the designation, while interacting with federal, state, and local laws, affected their lives. In the novel, I reference the Thind case, which established a racial classification for South Asians. Because Thind was classified as neither “white” nor “black,” he was deemed to be of a race that was ineligible for U.S. citizenship. That happened under federal law. And, under California’s state law, people who belonged to a race that was ineligible for U.S. citizenship could not own land or enter into long-term leases to farm any land. So, the federal and state laws worked together to prevent the Punjabi immigrants from farming for their livelihood, even if they had been doing so for many years. That situation provided the central plot issue for Passage West. Also, under the state miscegenation laws, people of differing races could not intermarry. This law was not uniformly enforced, which is why Karak and others were able to find wives in the United States, but technically, what he did was illegal. At that time in California, if the clerk of their county refused them a marriage license, many “inter-racial” couples would cross the state border to marry in other states.

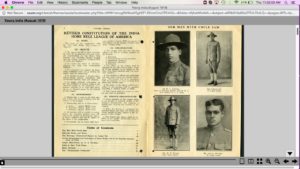

Closeup of Young India story about Indian-American soldiers in WWI

Closeup of Young India story about Indian-American soldiers in WWIWhat additional research did you do for the novel? How much of it is based on actual events?

I had not set out to write a huge novel. I was hoping for a smaller book dominated by a love triangle between an immigrant farmer named Ram Singh, a daring Mexican woman named Adela, and Ram’s devoted wife Padma, whom he was forced to leave behind in Punjab. But after I researched the topic more deeply and interviewed the descendants of early South Asian immigrants to California, I realized I had a much larger story to tell.

I got lost in the research! I discovered the South Asian men who fought for the United States in World War I, and also learned about covert US-based plots to overthrow the British in India. The vast majority of the novel is founded on actual events that I learned about from the children of that community or that I read about in newspaper articles from the 1920s or from reading modern sociological studies. The research was so fascinating that it was hard to decide which story to tell. Basically—I decided to include all of it.

I smile when you mention “covert US-based plots to overthrow the British in India” because that turns up in my 2021 novel, The Bombay Prince . Can you tell me more about the Ghadar Party?

Many Indian intellectuals, revolutionaries and laborers who were working for the overthrow of the British in India settled in the United States, a place where they could continue their organizational activities outside of British scrutiny. Despite their efforts, they attracted the attention of the United States government, which had been heavily lobbied by the British to curtail their efforts. The Indian revolutionaries drew upon the ideological roots of America, Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry among others, in their efforts to draw people to their cause. They led a movement called Ghadar, meaning ‘Revolution,’ and published a globally-distributed newspaper under the same name. Although they may have been unsuccessful in their immediate efforts, their ideology certainly pushed the Subcontinent toward independence two decades later.

What else did researching for Passage West reveal about the history of the United States?

I am fascinated by how many people were written out of the history books. My research took me to old newspaper accounts and government studies about immigrant communities in the United States in the first quarter of the 1900s. Newspaper journalism is often called “the first draft of history,” however, when we study that history in school, it is in the form of a highly edited subsequent draft that excludes so many that lived and worked in this country. Unfortunately, it is the edited draft of history that has formed our American Narrative, and it is inaccurate.

The novel’s first chapter opens with the protagonist Ram Singh, in his elder years, taking possession of a dead man’s document, and remembering something of a past crime. Ultimately, you narrate the long road toward a killing and a complicated, twist-filled murder trial. Had you thought of your novel fitting into a crime fiction genre, and would you have crime in future writing?

I did not think of this novel as fitting into the crime genre while I was writing. It was only after the book was out in the world that I read a very flattering review by Doreen Sheridan on the website “Criminal Element,” and I thought—yes—the novel could be seen in this light, too. The crime that lies at the center of the novel was based on a real multiple homicide, so I don’t know why I never thought of that angle before. And as a lawyer, I just couldn’t keep myself away from a good old-fashioned courtroom scene, where something crucial is revealed! It was certainly fun to write. If I thought in terms of genre at all, I was thinking of a classic Western…. A gun, a horse, a wind-blown landscape….

You and I have similar family journeys from India, to Britain, and then finally the US. Do you feel viewed as a Westerner at times in India, or are you welcomed as a home comer? How did your diaspora upbringing affect research for this book when you went to Punjab?

I have always felt that I did not wholly belong to either place: India or the United States. Part of that is because when I was growing up in America in the 1970s and 1980s, India and America were very far apart culturally and politically. Years later, when I was in India for a couple of readings for my first book, Karma and Other Stories, I realized that I was being viewed essentially as a foreigner author. I had always been aware of this “foreignness” in my many childhood trips there, but it was ironic—given that the book was about trying to remain “Indian” while living in the US! It was even more interesting to go to Punjab for my research for Passage West. In Punjab, I was seen as an American, but I was also seen as Telugu, not Punjabi. I certainly don’t speak Punjabi, and the customs and culture of north and south India, where I was born, can be very different.

Was this your first novel, or is there another novel in the drawer?

I do have another novel “in the drawer” from a long time ago—don’t we all? It will never see the light of day. I managed to create a few good scenes—and I sure learned a lot writing it.

I am grateful to Rishi for honoring a community that’s been largely forgotten. Passage West, selected by the LA Times as one of The Best of California Books of 2020, is a must for anyone interested in South Asian crime fiction, historical mysteries, and immigration stories. Find out more about Rishi, including her availability for book club conversations, at her website rishireddi.com.

The post The Long-Buried History Inside Rishi Reddi’s PASSAGE WEST appeared first on Sujata Massey.

February 10, 2022

Snowstorms and Brainstorms

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

In my long-ago life as a newspaper reporter, there were a few words I wasn’t allowed to use. No profanity, of course. And the other expression I remember was THE WHITE STUFF.

White stuff was on the lips of every television weather reporter when they talked about snow. On the rare occasions that it snowed in Baltimore, the situation was considered too dire for metaphors to be used in the Baltimore Evening Sun.

I am a free agent now, and I find myself looking for varying words to express the wonder of snow. Tiny soft flakes, angularly falling snow, the snow that’s packed an inch thick on the street, the abstract craggy formations of old snow and ice everywhere.

I’ve just spent a week in St. Paul, Minnesota. Through the week, I saw snow falling three times. It carpeted the Mississippi River and the lakes, and it was packed down into a slick surface on neighborhood streets. A type of snowstorm cheerfully called a “capper” is coming down from Canada today.

I spent ten years as a child in St. Paul. A quarter century later, I returned to live with my husband and children in Minneapolis—a six-year stay. I feel at home, and not at home, here. The cities sit side-by-side and are therefore nicknamed the Twin Cities. I’d call them fraternal twins. Minneapolis is slightly more urbane, and St. Paul just a bit homier. Both have theater, colleges, culture and lively immigrant populations; the Minnesotans seen in movies are living in the ‘burbs.

And there are hard things about these Twin Cities we must be accountable for. Philandro Castile was shot to death in his own car in the St. Paul suburb where I grew up—no jail time for the officer involved. In Minneapolis, George Floyd was strangled by police officer Derek Chauvin, who was convicted. Minneapolis and Saint Paul sparkle with lakes and solid, charming old houses, but there is pain underneath, like a filthy black under-crust of hardened ice.

The first day of my trip home, I made a pilgrimage to Lake of the Isles, the body of water that filled my eyes every time I walked down to my children’s school. I stopped nearby at Birch Bark Books, the gem of a bookstore owned by the author Louise Erdrich, where an old wooden confessional booth inside the store plays a dramatic role in her brilliant new book, The Sentence.

I listened to The Sentence as an audiobook read by Louise on the long drive from Baltimore to Minnesota. I was transfixed and knew I had to buy a number of hardcover copies to share. The novel includes a tale of crime and incarceration, a love story, a ghost story, and Native American history. It was written during the pandemic and unbelievably, was released while we are still in the thick of Covid deaths. The novel digs into the heart of what happened in the Twin Cities during this momentous time, from the empty store shelves and closed businesses, the full hospitals and struggling medical people, and in the middle of all the desperation—George Floyd’s murder. This is a book which made me laugh out loud, and also weep quietly.

A few days later, I returned to Lake of the Isles on a different mission. It was a dark Saturday night and relatively warm: 26 degrees! The Luminary Loppet is an annual winter celebration that brings artists to the lake. The artists freeze water into ice sculptures that are illuminated with glowing lights. Fire dancers, musical performers, and plenty of charming dogs trained to lope along with their skiing humans made this such a happy, spectacular gathering. I walked the surface of the lake with friends, marveling at the ice sculptures and spirited entertainment, and at the strollers and skiers, some of them with dogs in tow.

A Minnesota winter also means a lot of indoor time.

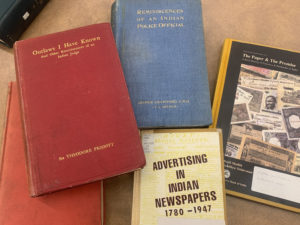

The Twin Cities is the home to the University of Minnesota’s flagship campus, which houses the extraordinary Ames Library of South Asia founded with donations from Charles Lesley Ames, a St. Paul lawyer who sailed to India in 1906 and began collecting books about India. In this special library, I’ve found memoirs and travel guides, books of folktales, government records, and other tremendous, rare books. It’s a historical novelist’s dream.

A few flakes fell as I drove a short distance to my haven, which is housed in the sub-basement of Wilson Library on the Minneapolis’s West Bank Campus. The library, which is generously open to the public, was uncrowded, as always. A couple of masked students floated through, but that was it. I was mostly alone, hearing only the buzzing of the light fixtures and an occasional opening of elevator doors in the hallway.

This time I found two memoirs by British colonials in the justice system: one a judge, the other a police chief. I paged through a beguiling volume of anthropological study of rain. I sifted through another book on the history of advertising in Indian newspapers, and one more about the introduction of paper currency. The day after my library visit, I meant to work on an outline for the proposal. But the first page of that book came like manna from heaven.

The brainstorming comes not like a blizzard, but a gentle sprinkling. The very best kind of white stuff.

[image error]

The post Snowstorms and Brainstorms appeared first on Sujata Massey.

January 26, 2022

A Dog’s Tale

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

I’ve invited a special guest writer this week. Daisy, approximately four years old by the human standard, is a Yorkshire terrier mix who has become the heart of our home. I am devoting most of my time this week to rewriting a manuscript, so Daisy kindly agreed to share her thoughts with Murder Is Everywhere readers. My apologies if she runs on too long—she’s the kind of dog who does what she wants.

Greetings, gang! It’s about time Sujata let me speak for myself. I may not write books, but I like to lie on top of them and laptop computers which have no business being on laps.

I consider it one of my jobs to remind the writer I live with about reality. In the real world, dogs need to go outside, okay? And I need Sujata to know that when I stand on the back of the sofa, barking out the window, it’s because I am preventing possible crimes by other dogs and even humans. I am doing my job as household guardian. I may only be ten pounds, but I’m faster than anyone around here.

I have lived with this family since 2018, when Pia walked into the living room with me in her arms and said to everyone that I belonged to a friend of hers and was just visiting for the afternoon. Above is a silly picture she took of me during this time. You can see how much love I feel.

Ha! I kept quiet, but the fact was, she had seen my picture on Facebook because someone wanted to sell me. I lived with two other families before the Masseys. The families were too busy to take care of me, so I didn’t learn a lot of puppy stuff—except for being friendly. But in the early months of my life, I saw people fighting. I was once thrown out of a window to show how mad someone was. I don’t like to go into the details, because it’s traumatic. Because of what happened before, it was harder for me to become housebroken. I also am frightened by raised voices, and I freak out when people raise their arms high.

My new father, Tony, is a psychiatrist. He describes me as an empath. I’m not sure what that means, but it might have something to do with the fact that I look very closely at you if you might sneeze or seem very excited about something. If someone cries, I put my paws on their shoulders and kiss them until they are back to normal.

I actually was the second dog in this house. Charlie was the only dog they expected to live with. When I met him, he was a twelve-year-old, extremely quiet beagle who had almost forgotten how to play. I was about eleven months old, so I had a lot of energy and made him play with me. I teased him a lot in the early days, but he still fell in love with me. He followed me everywhere, even though I was so much smaller than him. Even though I was the second dog, I was never second banana.

[image error]

2021 was the hardest year in my life. Just as spring was beginning, my buddy Charlie died. He was getting very sick and thin and finally went to sleep in the sunshine on the deck. I didn’t know that he was really gone forever, so that first night alone, I sat on the dining table all night, hoping he would come back through the door.

A month later, Pia died. I get confused because I sometimes see girls with very long dark hair like hers, or who wear similar kinds of sweatshirts. I will always remember her letting me go off-leash outside and run. Pia liked to rev me up and made my life very exciting. I am fortunate that her brother Neel is home from college. I can snuggle with him in his room for hours. And what a room it is—often, I will find French fries or a pizza crust. It’s better than doing book promotion with Sujata.

Still, I’ve been inside the house too much. Maybe you can relate? I sit next to Tony while he Zooms for work, and I get on Mom’s yoga mat when she gets into the play positions. I like yoga better than book promotion.

[image error]

I know that dogs are very lucky not to catch coronavirus the way cats and tigers have. However, I don’t like masks. When Sujata takes me on walks, other people walking their dogs go on the other side. And that social distancing made me even more nervous about dogs than I already am. I get frightened if a dog looks at me. I have to bark back, so nothing terrible happens.

My dog walker, Betsy, is a very nice lady. She kisses and cuddles me when she visits about twice a week. I don’t care that she wears a mask, because her eyes are always smiling. Betsy started some doggy playgroups during the pandemic. I was very scared the first time I went inside my special spot in her car which was jam-packed with four other dogs who all knew each other. They were a pack, and I was the newcomer. But nobody bit me or growled. They let me join them.

Soon I was going with them twice a week, and if I could get away with it, I’d rush to the front of the pack to lead. During these walks, I visited parks and neighborhoods all around Baltimore. Occasionally my parents left home for important reasons, and I stayed overnight with Betsy and her daughter. Sleepaway camp!

Right now, it’s the middle of winter. I believe this spring will be happier than the last one. I am already dreaming about the budding of daffodils and tulips and other lovely areas to leave some pee-mail for others. But for now, I am sitting comfortably on the radiator cover by the big window, keeping an eye out for our beloved mail carrier. I will whimper with joy when I see Tom step on our porch, and if he knows I’m here, he will wave at me.

We will have our special moment.

And at exactly four o’clock, I will jump off the couch and appear in Sujata’s study to remind her it’s time for dinner.

Love to all of you,

Daisy

The post A Dog’s Tale appeared first on Sujata Massey.

January 13, 2022

When a Book Needs a New Home

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Have you ever thought about what happens to a particular book after it’s been read? Does it settle into a gentle slumber on a shelf, or a haphazard spot on the floor? How will it continue to do its work?

I love having a house full of books; in the butler’s pantry, dining room, living room, all bedrooms, sunroom, and study. Yet even though I have space, it’s not enough, nor is it right for me to store them with limited or no future use.

Necessity forced me to shed books shortly after I’d finished college. After five happy years working at the Baltimore Evening Sun newspaper—acquiring many novels for pleasure reading—I was moving to Japan with my husband. I was thrilled. I also knew the four hundred or so books packed into my worn-out IKEA bookcases would sink the shipping allowance the Navy had provided. So, I took a deep breath and whittled down my collection. I took four boxes to Japan, and these books were a great comfort and inspiration.

My husband and I returned to the US with a few more books I’d bought in Japan. And in the three decades since coming back, we have moved house six times! And with every move, I learned to give away books, no matter how dear they were to me when I used them.

The pandemic that began in 2020 led a lot of us to clear clutter out of their homes, including books. As soon as we were in official lockdown in March, 2020, I felt called to examine the thousand plus books that had slowly crept into my home. The challenge was that it was hard to bring donations to the usual spots during the pandemic, since they were also locked down.

Hopes rose when I heard about the Maryland Book Bank. This grassroots book hub sounded like perfection: a warehouse site a few miles from my house with an open-door policy of taking all books and no-contact drop-off. That particular day I brought my books, it was raining heavily. I was anxious leaving my boxes of books beside the loading dock’s series of dumpsters that were already overwhelmed with print.

But I let those books go, and my house became a little less cluttered.

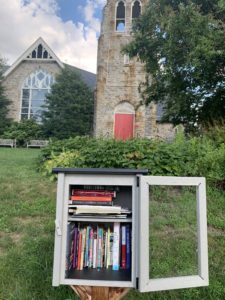

As we all know, the pandemic continued past the spring of 2020. During the early autumn of 2021, I had the energy to examine my bookcases again, and withdrew about sixty more books from hibernation. During my neighborhood walks, I had often passed some curious structures shaped like child-drawn houses on stilts. These cabinets, bearing labels that called them “Little Free Libraries,” were packed with donated books. The sign on the cabinet was inviting. “Leave a Book, Take a Book.” And I thought…maybe this is another donation solution?

Ednor Gardens neighborhood

Ednor Gardens neighborhoodI went to the website for Little Free Library and learned about the history of these intriguing cabinets, which began in 2012 when a Wisconsin man named Ted H. Bol built the first Little Free Library in honor of his late mother. The idea of “Take a Book, Give a Book,” caught on and became very popular in Wisconsin’s neighbor state, Minnesota, where the nonprofit now is headquartered. Today LFLs are common inside and outside of homes, businesses, and community centers in every state of the U.S. and more than 100 countries. And every book-box that stands is only there because of a specific person who sets it up and maintains it.

Most LFL structures have two shelves and they are not tall or wide. The LFLs can fill up fast, especially in bookish neighborhoods. I started off donating books to the LFL near a church two blocks from my home, but it was always packed to overflowing. There was no way I could pack in seventy books.

I also yearned to bring books to areas that didn’t have the same overwhelm as my neighborhood. I did more reading on the LFL website and learned that Little Free Libraries in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods didn’t get regular drop-offs. They also didn’t have many books that featured diverse people and settings. I packed up my car with works by the likes of S.A. Cosby, Kwei Quartey, Vivien Chin, Jesmyn Ward, and so many others.

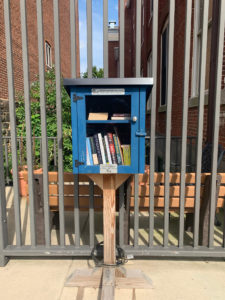

East 25th Street

East 25th Street

The first LFL I visited on East 25th Street in Baltimore was near a community center. The wooden cabinet was cheerfully painted in red and yellow and had a garden on its roof. What was missing was a clear plexiglass door to shield books from rain. That made it look vulnerable. Nothing was inside the library, except for two school supply bags and a bottle of cooking oil.

I slid in a donation of teenage and adult fiction by authors of color, or set in various parts of the world. A few months later I returned, happy to find the books I’d brought had all found takers. There was ample room for the extra books and school supplies I’d carried with me.

The Abell Open Space

The Abell Open Space North Charles Street

North Charles Street Belvedere Square

Belvedere SquareSince that first expedition, I’ve donated at many other Little Free Libraries around the Baltimore, most of them found with the help of the online mapping tool at the LFL website. And this activity of purging and sharing doesn’t mean I’m reading less. Writing historical fiction makes it essential to hunt down books that might be out of print for the sake of research. I also continue buying books to support authors who are launching or continuing careers during a time that there are few opportunities for in-person book signings.

Bellona-Gittings Neighborhood

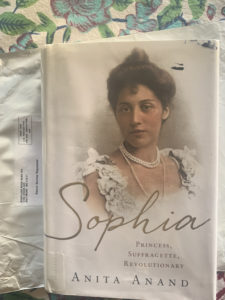

Bellona-Gittings NeighborhoodRecently, I decided to research Sophia Duleep Singh, the“suffragette princess” who was an activist in India and Britain during the Edwardian period. Sophia, a biography written by Anita Anand in 2015, was out of print. However, Amazon listed a hardcover edition as being available for mail order from a used-book seller at a very low price. Amazingly, the seller of this former library book was…

The Maryland Book Bank! Yes, the very first place I’d gone on the odyssey with my books.

The post When a Book Needs a New Home appeared first on Sujata Massey.

December 29, 2021

An Improvisational Year

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

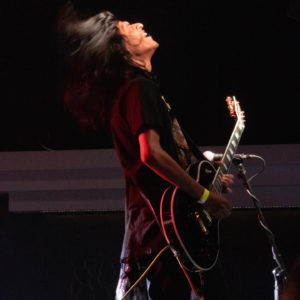

The songs are playing day and night. Some of them are tentative, while others blow the dust off the steep wooden staircase. My son is home from college for the winter holidays and nestled in his third floor bedroom with all his electric guitars—and the amplifiers. The improvisations he makes seem endless.

I felt as if I’d ridden up to the crescendo of a power rock ballad when the first dose of Moderna went into my arm. After the jab, a sweet slide of relief into feeling saved. Yet after the freedoms of late spring and early summer, the Delta variant, and now Omicron, are showing that I can’t expect the world to do what I want for it.

I could give up and live in a “what we lost” world. But there is another choice.

According to the Cambridge English Dictionary, the primary meaning of “improvisation” relates to creations of music, dance and theater. The secondary definition is described as “the act of making or doing something with whatever is available at the time.”

I have the privilege of sheltering in a home that I own during this pandemic with the company of family and the support of other good people nearby. Surely that makes it easier to think positive.

And yet, my mind turns to M.F.K. Fisher.

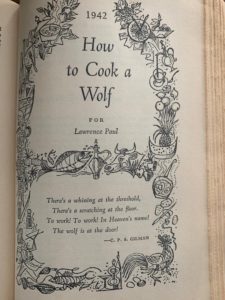

I count Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher, as she was named at birth, as one of my most important spirit guides. The barrier-breaking food writer (1908-1992), began with essays and memoirs in her 20s, when she left California to live in Europe. Fisher spent most of her life melding her literary talent with her affection for cooking and people. Her books make you want to feast and drink fine wines, but the reality is that her life was often excruciating. When her desperately ill husband died by suicide in the 1940s, she stayed in Europe, a single mother with a young child, and no obvious means of support. During this time she was always dancing on the edge of starvation, yet she found ways to feed herself and others, and wrote a hilarious book called How to Cook a Wolf with recipes for living this way that has been rediscovered and comforted yet another generation. As she writes in introduction, “War is a beastly business, it is true, but one proof that we are human is our ability to learn, even from it, how better to exist.” She goes on to say, “It is all a question of weeding out what you yourself like best to do, so that you can live most agreeably in a world full of an increasing number of disagreeable surprises.”

I live agreeably, because I am in an old house that has settled around me over like bedsheets slowly warming. It’s an 1897 cedar-shingled summer cottage within a nine-block neighborhood within North Baltimore that was developed in the mid 1890s through the 1920s. This development, Tuxedo Park, adopted the name of an elite community in New York, although my Tuxedo Park always had considerably more plebeian occupants. The plot of land on which the house stands was bought by a woman, most likely because the developers wouldn’t sell to her husband because he owned a saloon. Tuxedo Park was just a streetcar ride away from the business life of the city, including the rough-and-tumble harbor and bustling downtown.

It’s my suspicion that dreams of outdoor socialization and leisure led to our house’s grandest feature, a three-sided wrap-around porch, and two large upstairs porches and several balconies.

I’ve spent a lot of time writing on the private upstairs porches, but rarely used the wrap-around porch. In fact, I didn’t even have furniture for it.

But this spring, I decided to set up the porch like a Victorian lady might have, with plenty of settees, chairs both for dining and lounging and a a variety of tables. Most of the shopping was accomplished from online sources recommended to me by an online designer at Decorist who provided color renderings showing where everything should go—including potted palms. I followed some of her shopping links and went to the crafters at Etsy and my storage room for other pieces—and to the garden for the four old handmade Adirondack chairs.

I wanted plants on the porch, which were part of the design, but I was nervous. I am comfortable with a garden full of native plants. I’ve never kept house plants, which are often exotics, alive for very long. So the first potted plants only arrived because they were gifts from friends. And these plants didn’t need much tending; they shot up with new leaves, even with my off-and-on watering.

In midsummer, a neighbor held a moving sale, searching for new owners for the dozens of potted plants that she’d tended lovingly on her building’s fire escape. I ambled over to her building with a small wagon and she agreed to sell me everything I wanted—and tossed in a few more plants for free. Gratefully, I wheeled away mature ficus and other friends, large and small, and best of all, already planted in ceramic pots with a soil blend that they liked.

Happily, the plants accepted their new home. Feeling more confident than expected, I bought some planters, potting soil, and a variety of big plants like palms and birds of paradise and citrus. Some of the plants I watered too much, and others seemed perennially thirsty.

Yes—I still had to do actual yard work with plants that lived in the ground. I pulled Virginia creeper and English ivy and set my spouse to battle invasive mulberry and Rose of Sharon. In fall, I divided the proliferating native flowers and shrubs I’ve planted in fits and starts since 2014. Coincidentally, a friend dropped by with seedlings she had no time to plant. She was also touched by desire a not to let anything be wasted.

Now that I had an outdoor room, friends came over, singly or in pairs. Sharing some pie and a cup of tea felt as special as the multi-course candlelit dinners of the before times. I arranged a weatherproof dining table and chairs on the east side, which is so pleasant in the evening, especially under the fans. The fans and mosquito lamps were shut off in cooler weather, and the guests dwindled, although a last supper with Minnesota visitors bundled up in coats and hats, was fun. As we sipped mugs of soup and ate corn muffins, I thought maybe… this could happen again on a nice February day.

As summer’s warmth slipped away, I moved the plant family, now numbering 27 souls, from the porch into the house. I took an unused desktop computer off a kitchen table and loaded it with plants, which would get happy sun exposure all afternoon. More plants made a colony in the butler’s pantry with its west-facing windows. To make room, I had to re-home the vacuum and remember to take out the recycling bags—but all things considered, I’d rather look at plants than empty cans and crumpled newspaper.

I dove into the writings and photographs of a modern plant guru (Hilton Carter, who lives in the next neighborhood over!) and followed his directions to make cuttings from the most exuberant plants. Roots slowly grew. I also went into the basement and found old forgotten flower bulbs that had survived a few seasons in paper bags. I’ve planted the ones that I hope are tulips in the garden, and the ones that are clearly dormant amaryllis in pots indoors.

I also converted a sunroom—which had been a storage room—back into a home for plants. How ironic that the architect’s original purpose for the room would finally be restored. I wrote about how this sunny hideaway has nurtured me in a short essay for Femina Magazine. The sunroom is tiny, but it’s an utter luxury to have two walls of windows with garden views, and seasonal theater starring birds, squirrels, rabbits, and the occasional fox.

Most evenings, I hunger for an activity that was relaxing, yet doesn’t involve the printed word, or a brightly lit screen. About once a week, I settle in a comfortable chair, bringing the lamp closer, and mend. Any sweater with moth bites is fair game, seized as well as pretty pillows that had been ravaged by the dog. The hardest repair project I undertook was my early 1960s fake-fox winter coat. I’d believed its fragile satin lining was irreparable, but I knew I could never find anything like it again. What else could I do but try?

I stitched together ripped seams and patched a hugely frayed section with a colorful scrap of fabric from my last trip to India. As I sewed, I remembered several friends I knew who were sewing masks at the start of the pandemic. I think of sewing, just like baking and gardening, as being quintessential pandemic activities. And I’m unashamed that my patches don’t match the fabric. They stand out as memories of fall 2021.

The more I ponder it, the dictionary definition of improvisation seems rather limiting. I. notice that the word “improvise” shares a linguistic connection to “improve.”

When Neel makes repeated changes in his playing, he becomes more skilled. Let him be the star. I’m happy enough to have learned to sew patches and grow a plant from a single leaf.

The post An Improvisational Year appeared first on Sujata Massey.

December 15, 2021

Get Your Roasted Nuts Here!

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Throughout December, almonds, walnuts, pistachios, and pecans are always in my shopping cart. I first wrote about this peculiar passion three years ago, yet I couldn’t resist returning to the topic this year. And the nuts made me contemplate whether traditions can shift a bit and still feel comforting.

This year, not as many Christmas markets are running in Germany as before Covid. For many centuries, Germany and other German-speaking countries have held Christmas markets in town squares that are filled with wooden stalls and sparkling lights, mulled wine and celebrating people. Weihnachtsmarkts sell holiday greens, ornaments, gingerbread, and a variety of roasted nuts—straight-up smoky smelling roasted chestnuts, as well as sugared, cinnamon almonds—either way, the nuts come wrapped in twists of newspaper. I remember going mad for the almonds and lead Christmas tree ornaments at the Recklinghausen Weihnachtsmarkt during a late 1980s holiday visit to Germany with my mother and sisters.

The other nutty tradition that gets me reminiscing isn’t tied to any holidays. Roasted nuts—especially peanuts—are part of the everyday street food scene in India. Walking through Mumbai, I’ve often passed vendors shaking peanuts in a giant steel bowl set over an open fire. What aromas! And just like the practical Germans so far away, these vendors shake the nuts into newspaper cones and hand them over.

Despite my overseas romances with various forms of roasted nuts, I only began roasting nuts at home in the early 1990s.I was inspired by a set of recipes for home-made spiced nuts by Julie Sahni. Such nuts seemed less perishable and safer to mail to my relatives than cookies—though I’m not going to lie, I make a lot of cookies in December, too. But nuts are the best: not only can you eat them out of hand, but you can add them to salads, cakes, ice cream, oatmeal, and pancakes. Add some chopped dried fruit and you have a trail mix extraordinaire. My family has come to expect these nuts to arrive every year. And it seems symbolic that our bicultural identity comes together in these nuts, which marry the sweet of Germany with the spicy heat of India.

As time marches on, many of us are reducing our sugar intake. Last year, I adjusted the venerable spicy nuts recipe with coconut sugar instead of ordinary white sugar. The coconut sugar didn’t make as nice a syrup with water as refined white sugar did. It was eerie, but the healthified nuts still tasted very sweet. My own threshold for enjoying sweetness had lowered.

This year, I decided to make extra batches of nuts using a few different sweeteners and to bake them in a regular oven. Because I couldn’t locate a recipe for such that called on Indian spices, I realized this was a chance to make my own recipe. I counseled myself to be prepared for imperfect results, knowing that food professionals often test upwards of a dozen times before a winner is found.

The seasonings

The seasoningsDriving the mission was a change in sweetening from dry sugar mixed with water to an already usable syrup. The sweetener I was most hopeful about was date syrup, originally known as dibis in Iraq and other parts of the Middle East. Typical uses for dibis are drizzled over hummus, mixed into drinks, and within desserts. I would never have known about it if I hadn’t kept coming across it in healthy baking recipes this past year.

One tablespoon of date syrup has a glycemic index of 47. Putting it in context with other options, maple syrup and coconut sugar have a glycemic index of 54, honey has 58, and sugar 60. (Agave syrup is very low—just 19 on the glycemic index—but I think it tastes weird). According to nutritionists, dates are loaded with amino acids, vitamins and minerals, and antioxidants. because of the protein within nuts, my holiday guilty pleasure could turn into a life-saving holiday hero.

Step into my kitchen. Here’s what happened.

20 minutes was too long for half these nuts!

20 minutes was too long for half these nuts!The first batch I made was three cups of nuts tossed with my usual spices and one-third cup of date syrup. I quickly found that date syrup tended to caramelize faster than expected—resulted in blackened nuts that weren’t very pretty and tasted slightly burned. I also noted (belatedly) that whole almonds are double the size of the walnut and pecan halves, so a shorter cooking time for walnuts and pecans would further protect the nuts.

For Attempt Number Two, I cut the oven time from twenty minutes to twelve minutes. I also did the extra step of splitting up the nuts on two baking sheets, with the fat almonds on one sheet, and the skinny walnuts and pecans on the other. That way, it was easier to take the faster baking nuts out when they were crying for mercy, and let the almonds linger a few more minutes.

Walnuts and pecans and pistachios done right

Walnuts and pecans and pistachios done rightSo far, so good.

I found myself curious about the road still not taken—another syrup that was a candidate for sweetening.What would the nuts taste like roasted with maple syrup? Would this lighter, higher glycemic index syrup be even better?

For Attempt Number Three, I took the one-third measuring cup I’d used for previous recipes. I filled half of it with date syrup from my waning bottle and then poured maple syrup to the top. After roasting, the nuts were soft and didn’t taste like much. Impatiently, I waited for them to cool to crispness before tasting.

[image error]Maple-Date nut mixHmmm. The odd thing was that although the maple-date laced nuts were lighter in color and dried to a nice crispness, the taste wasn’t as deep and hauntingly flavorful. There was an umami in the date syrup and a nicely chewy caramelization that was no longer there. And being able to taste between the various batches made me decide that date syrup alone was the best. The ultimate nuts that I’m sharing with you.

Voila! Click here for the recipe.

Which special traditions do you enjoy that you would never change? And what have you tweaked for the better?

The post Get Your Roasted Nuts Here! appeared first on Sujata Massey.

December 1, 2021

My Holiday Movie at The Charles

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

A Thanksgiving movie is as much of a tradition for me as the cooking. When I used to return from Baltimore to St. Paul, Minnesota, in November, my sisters and mom and I always endeavored to find a special film to watch at an art house theater like the late Uptown, and still flourishing Lagoon, in Minneapolis. The theater would always be packed, and we would inevitably run across old friends in the venue and go out afterward for coffee and film discussion.

Since 2020, Thanksgiving has been different for everyone. We had only two guests this year for Thanksgiving in Baltimore—our college student son and my youngest sister. We were so grateful for both of them. When they left on Saturday, life was suddenly dead. Sunday loomed large, and I asked my husband Tony if he’d like to go to the movies.

I hustled my husband off to see the new documentary on Julia Child at The Charles Theatre, an “art house theater” that is reputedly Baltimore’s oldest—dating back to 1930, although the building’s former life was as a barn housing streetcars dating back to the 1890s. The theater, a smartly renovated brick building row with Tapas Teatro, a great small-bites restaurant, is sited one block from Baltimore’s Penn Station, where we had recently dropped our son for his trip back to Boston. Driving past The Charles on Saturday surely put the notion in my brain that I must return to the movies, fear of omicron be damned.

Late Sunday afternoon, a few people were wandering into nearby restaurants, but there was no queue for theater tickets. Inside, we found the ticket box just as we remembered it. However, the attendant surprised us by swiveling an iPad-like device to us showing a sea of green dots—dozens and dozens of available seats for Julia. Only four people other than ourselves were present. How weird! There would be no need for an aisle seat, or to worry about tall heads in front of us. The theater would be our living room. Masking was required, a precaution that I’m happy to oblige.

The Charles was once a small player in the city’s film scene. Through the 1960s, Baltimore was filled with independently owned cinemas, according to author/photographer Amy Davis, who created Flickering Treasures, a gorgeous photographic history book. I’ve been in many of them, which still functioned during my life as a student and young newspaper reporter of Baltimore. But of all my Baltimore theaters, The Charles makes my heart throb. On many nights from 1982 through 1986, I came with classmates from the Johns Hopkins University campus to see films by the directors we were hearing about from our then-writing seminars professor, Mark Crispin Miller. I saw Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and Paul Verhoeven’s The Fourth Man and so many other films that are lost in my faraway memories.

In my day and earlier, The Charles was an inelegant, wide squat structure whose architecture was dominated by its approximate 500-seat auditorium. Between 1939 and 1958, it was known as The Times Theatre and specialized in newsreel cinema only—a precursor to television news. In 1958, The Times was taken over by another owner and became immortalized as the more elegant-sounding Charles, showing a wider range of fare.

In the 1960s through the 1980s, the large room above the theater was called The Famous Ballroom and home to The Left Bank Jazz Society, which hosted musicians famous and infamous, including Dizzy Gillespie and John Coltrane. I remember taking in a show and buying delicious fried chicken, a far better refreshment the popcorn offered downstairs at the cinema.

I’m exercising my use of a capitalized “The” a bit more than usual. The Charles is that inspiring. The John Waters was a longtime friend to the theater, and reworked it to pose as an X-rated theater in his 1977 masterpiece, Polyester. Many Baltimoreans appeared in John Waters’ films, including Edith Massey—no relation—and Mink Stole, who I see at neighborhood potlucks.

Another of my Baltimore neighbors was a man named George Udel. George was a television cameraman and filmmaker who ultimately became the director of two film festivals and the Baltimore Film Forum organization. George was the fellow who could get special films from thousands of miles away to The Charles. He also became the beloved founder and host of Cinema Sundays, a one-time-only special film show with bagels, coffee, and audience discussion on Sunday mornings at The Charles.

In the late 1990s, when I had written just two novels set in Japan, George recruited me to be the discussant for an Akira Kurosawa film for Cinema Sunday at the Charles. I protested that I had no credentials or film expertise beyond a few courses I’d taken at Hopkins, but he prevailed, and I had the once-in-a-lifetime experience of standing on the big stage at The Charles and being part of the film discussion that ensued after.

George is sadly passed on from this world. He died from heart disease just few months after the theater’s grand reopening in 1999. The legendary Raoul Middleman—also deceased—painted a massive portrait of George that hangs in the theater’s hall in a forward-facing position. Nobody going into a film misses George.

As I mentioned at the start of this blogpost, only four others were present at the 4:10 PM showing for the Julia Child documentary. Julia is also being streamed, so I hope more people can see this terrific film either in the theater or outside. It includes diary entries and never-seen photographs—including a tasteful nude of Julia shot by her husband Paul! I felt so grateful that movie theaters are continuing to keep doors open, despite low numbers of attenders.

I was so warmed by my reunion on Thanksgiving weekend with The Charles that I returned alone on Monday to see The French Dispatch. This time, only two people were in the theater. By now, I wasn’t surprised by the number. My own spouse—a fellow Charles Theatre aficionado from the ’80s—wasn’t interested in this one. From the preview, it was clear that this Wes Anderson film would be long on scenery and storytelling, and short on action. A better film for someone like me to see.

[image error]

It turned out that The French Dispatch was basically a love letter to the hardworking and creative writers in the history of The New Yorker. The film was too long, but it was a charming, meandering feast for the eyes and ears. I thoroughly enjoyed laughing by myself at the best moments, which were plentiful. The film also inspired me to renew my subscription to The New Yorker after many decades’ absence.

The two shows I saw reminded me that watching a film is as private an encounter as reading a book. That was the magical experience that George Udel believed in—why he worked so hard to bring odd and far-flung films to Baltimore.

We’d see things that we never dreamed were there.

The post My Holiday Movie at The Charles appeared first on Sujata Massey.

November 17, 2021

Patricia Raybon: Secrets of 1920s Colorado

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

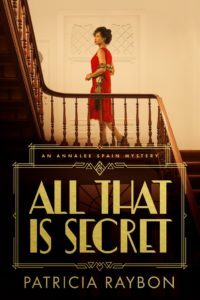

When I spotted a short review in Parade Magazine for ALL THAT IS SECRET by Patricia Raybon, I knew I wanted to read it. The mystery is set in 1920s rough-and-tumble Denver, Colorado, and the ranches nearby. The novel’s narrator is Annalee Spain, a young theologian in 1920s Chicago who has surmounted both the sexism and racism of the era to get her teaching position. After Annalee’s estranged father dies in Colorado, she receives a mysterious summons to return home to investigate in an environment where the Ku Klux Klan is gaining power.

ALL THAT IS SECRET has been showered with praise, cited in best mystery lists for 2021 by Crimereads, BookBub, Women’s World, Parade, and PBS Masterpiece Mystery.

Patricia Raybon’s earlier career as a former newspaper reporter shines on every page with clothing and architectural details and social and political history. She was kind enough to answer some of my questions about her book, her relationship with the state of Colorado, and how Annalee calls on God as her ally throughout the story.

Please tell us how the idea originated to write about 1920s Denver, Colorado, and the Ku Klux Klan corruption of that specific time and place?

First, I love “clergy” mysteries—Father Brown by G.K. Chesterton, Grantchester, Rabbi Small, and the like. My hope was to introduce a faith character in Colorado – a beautiful “sunshine” place, and my home state, but during one of its darkest times, the 1920s. Good fiction needs a threat element, even if it’s only hovering in the background. So, that’s how I used the Klan, a home-grown American hate group, in my mystery. The story’s foreground centers, however, not on the Klan, but on my lead character—a young Black theologian who’s a fan of Sherlock Holmes—whose amateur sleuthing to solve her father’s murder is impacted by the threat of the Klan. I hope it makes for good tension.

For our international readers, where is Colorado in the United States and how did the geography and location fit into your mystery?

Colorado is located in the western U.S. An extraordinary place, it’s a Mountain State known for its is vivid landscape of rocky peaks, forests, high plains, mesas, canyons, plateaus, rivers, and also desert lands. The discovery of gold in the Colorado Rockies, and later silver, drew more than 100,000 desperate settlers to the territory in the 1800s—“a great river of human life rolling toward the setting sun,” wrote one historian, all seeking riches, which few found. Colorado’s capitol town Denver—called “The Mile High City” for its altitude at one mile above sea level—became a town of corruption and scams, a contrast to the area’s beauty, sitting as it does under bright blue skies with an average of 300 days of sunshine a year. The contrast between stunning geography and beauty, and hunger for wealth and influence, makes for a compelling backdrop for a mystery. Growing up in Colorado, where I still live, I recognized that I could use that tension between “Sunshine and Scoundrels”—the unofficial motto of Denver during the period of my mystery—to good effect. The rise of the Klan during that same time frame fit into the crime vs. beauty motif, making for tension-filled tone and mood that serve the setting of a mystery in wonderfully atmospheric ways.

What about your lead character, Annalee Spain? How unusual was a female seminary professor in the 1920s in the U.S.? Especially a Black theology professor?

Her vocation wouldn’t be totally unusual for the 1920s for two reasons. Many college-educated women in the U.S. matriculated at all-female seminaries, forerunners of female colleges such as Smith or Wellesley in the U.S. Many such seminaries were offshoots of faith denominations. Their goal was to prepare young, unmarried women to be teachers. Meantime, there was a move by many denominations in the U.S. to launch colleges for “Negroes,” now known as Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). My dad, for example, graduated from Lincoln University in Missouri, founded in 1866 by African American veterans of the American Civil War. Some white schools, such as Oberlin College, had accepted Black students even earlier—at Oberlin since 1835. The African Methodist Episcopal denomination in the U.S., formed in 1816, formed two seminaries, graduating young Black theologians from the onset of those schools. While most white colleges in the U.S. weren’t integrated until far later, Annalee would’ve found a place to study and wouldn’t be “the only” young Black woman in her age cohort to earn a college degree. Her study of theology would be rare, but not impossible.

What sort of research did you do for your historical mystery novel?

I started out reading histories about Colorado’s Klan. Then, I found myself poring over old Colorado newspapers from the 1920s, the era of my book. With thanks to Denver Public Library’s extensive Western History Digital Collections, I listened to oral histories, scoured old phone books, street maps, vintage photos, church bulletins, minutes of club meetings, government documents, letters and diaries. One surprise to me was that many white residents in Colorado begrudged the Klan, a group whose influence came to consume Colorado life and politics, as one observer said, “like brush fire.” Meantime, small story details demanded attention: How much was a train ticket from Chicago to Denver in 1923? What perfumes were women wearing? Aftershave scents for men? Car models? Hit songs? Popular movies? Buttons vs. zippers on clothes? I love history, so pouring over this material never got old.

Those are exactly the kind of details that I love reading. I was wondering, because Annalee is a Sherlock Holmes fan, does that mean you are, too?

Sherlock Holmes is, for me, a pivotal fictional barometer for mystery writing. One of my most prized possessions, in fact, is The Original Illustrated Sherlock Holmes—featuring 37 short stories and a novel, The Hound of the Baskervilles, from The Strand Magazine—with all 356 original illustrations by Sidney Paget. It is a glory. As I mentioned, my other favorites are historical clergy mysteries (Father Brown, Grantchester and more), and I deeply love Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot mysteries. In particular, I love historical mysteries set in global locations including Vaseem Khan’s Baby Ganesh mysteries in India, Sujata Massey’s Perveen Mistry mysteries also in India, Harriet Steel’s Inspector de Silva mysteries in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Rhys Bowen’s Her Royal Spyness mysteries in the U.K. (and her stand-alone novels), Alexander McCall Smith’s No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency mysteries in Botswana, Shamini Flint’s Inspector Singh mysteries in Malaysia, as well as William Kent Krueger’s Cork O’Connor mysteries in the Northwest U.S. (and his excellent stand-alones).

Aw, shucks! Thanks a lot for including my 1920s series. Another thing we have in common is journalism. I was a newspaper reporter for five years, and you worked a dozen as a journalist for the Denver Post and the Rocky Mountain News. Then you joined the journalism faculty at the University of Colorado at Boulder, teaching print journalism for fifteen years. How did you end up also writing books—especially mystery books involving faith?

I was born on a church pew. (Well, almost.) I was born, that is, into a Black family of devout followers of Christ while also growing up under Jim Crow segregation and bigotry in the U.S. Thus, I always asked hard questions of God and wrestled over the answers, finding myself writing person essays and reflections—from the vantage point of a journalist—about this journey. Then, when I accepted a tenure-track faculty position in journalism at the University of Colorado, I ran headfirst into the “publish or perish” rule—meaning that to earn tenure, I also had to start writing books. Taking a chance, I first wrote not on my academic discipline, but a memoir on my spiritual struggle to make peace with White America and its history of systemic bigotry. That non-fiction book, My First White Friend: Confessions on Race, Love and Forgiveness, won several awards, including a Christopher Award with a lovely, uplifting mission—for “artistic excellence affirming the highest values of the human spirit.” From that point, I continued writing at the intersection of faith and race, including with my new mystery novel. As a woman of color, I write about faith not because I have all the answers, but because I’m compelled by the journey and its questions. Faith adds an added layer of mystery to all my writing that many readers, regardless of their faith beliefs, say they find intriguing, urgent, and honest. I love faith inquiry and I’m grateful to bring it now into my mystery writing.

Is this the beginning of a series? Where are Annalee and her love interest Jack Blake—a complex young pastor who fought in World War I—going from here?

To my wonderful surprise, the Annalee Spain Mysteries are envisioned as a series, with Annalee and Jack playing central roles. My publisher, Tyndale House, requested three books to start out. Mystery readers love a series. So, overnight, I went from writing one book to developing a mystery series. I just completed Book 2, which I loved writing. I love that the relationship between Annalee and Jack is an intentional subplot in the stories. So, to find out what happens, follow along on their next adventure. It’s due to release in Fall 2022.

Thank you so much, Patricia! I am looking forward to Annalee’s next outing and seeing you in real life, too.

The post Patricia Raybon: Secrets of 1920s Colorado appeared first on Sujata Massey.

November 3, 2021

The Last Line

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

[image error]

It’s often said that the start and end of a book are easy, but the middle is terrible. I’ve been lost in the creation of a novel for about fifteen months—and quite intensively during September and October. I wouldn’t say any part of this book has been easy. However, on a recent Monday, I polished off Perveen Mistry #4 with a final line. It reads like this: Laughing, Perveen put an arm around Sunanda; and as the skies broke open, they ran in.

Such a vague line! It’s not creatively gorgeous, descriptive, nor climactic. But that’s the way last lines play for me. I see them as the culmination of many strings tied together. These lines often show characters feeling the same expressions of release that I do, at a book’s end.

I’ve written sixteen novels to date, and the last lines typically have an upbeat feeling. I don’t obsess over them; however, the speed at which I write a last line does not mean it’s a throwaway. It’s very important for the readers’ experience.

Here are the last lines in The Widows of Malabar Hill.

“The power of women,” Perveen answered as their glasses clinked.

The Satapur Moonstone.

And she would add one more name, Perveen Mistry Esquire—to the invitation list.

The Bombay Prince.

She was ready to hear all of it.

In my twenty-five years of publishing fiction, I haven’t written last lines that could be labeled as grand revelations or shocks. I’ve read some shocking and heartbreaking last lines in books I’ve enjoyed. We need books like this, and I can’t say I won’t ever have a dark twist on the final page. The truth of a story is gradually unearthed. I write scenes that I later erase; I have characters say things that change in future drafts.

By the last line, I am saying to myself, “Here! This is what I want to suggest to readers to think about. Let’s break down some of those lines.

“The power of women,” Perveen answered as their glasses clinked.

We share the toast with Perveen and her companion after they clink glasses in sentence one. It’s an expression of emotion and gives you an idea of themes of books that will follow this opener of the series. This line was quoted in a number of book reviews, so I know it worked.

And she would add one more name, Perveen Mistry, Esquire—to the invitation list.

You know there will be a party! What could be better, especially since the book ends with a parting of people who like each other?

She was ready to hear all of it.

The third book’s last line seats you alongside Perveen, waiting for a lecture to begin. Her mind is cleared from all the trouble of the previous pages and she’s ready to focus on something outside of herself.

And that’s what’s also great about finishing books. It’s time to go on mental holiday from 1920s India; time to clean up, to cook, to garden, and best of all, to read other people’s work!

The post The Last Line appeared first on Sujata Massey.

July 28, 2021

A Breath of Fresh Air

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

What is it about wind at the shore? It’s the most soothing caress. When you add in the eternal sound of crashing waves, and an endless blue expanse of sea and sky… to me, that’s a perfect moment.

I drove a few hours with my family to Lewes, Delaware for a whole week in mid-July. We are not “downy ayshun” people, as many Marylanders are. When our children were young, we never had the funds to travel to Maine or the Eastern Shore or the myriad other places Baltimoreans visit to escape humid temperatures over 90 degrees in July and August. We were OK with it. But I always had a dream… what would it be like to spend some days in a beach town?

I came to appreciate Lewes (pronounced Lewis) when I was invited to participate in the History Book Festival held annually by the Lewes Public Library. There was the odd coincidence of my having named a British male character as Simon Lewes in my 2013 historical novel, The Sleeping Dictionary. At that point, I only knew that Lewes is a town in Sussex, the area of Britain where I was born. It struck me as particularly pleasant-looking name, and that’s all I can say for my subconscious.

As I said, a couple of visits to Lewes, thanks to the library, made me start to feel a kinship for this charming town. Since its beginnings with a failed Dutch settlement in 1631, Lewes grew into a busy 19th century fishing town. Because of the odor coming from fish canneries, it escaped tourism until the latter half of the twentieth century. This was when the canneries closed, and people from neighboring states realized the Lewes cottages were as adorable as those in Annapolis and Georgetown—and a lot less expensive, both for summering and for year-round retirement.

Through VRBO, we found a 19th century cottage painted a happy yellow on a quiet street a couple of miles from the beach. There was a mix of longtime residents and newer people on the street, and there was zero party scene. We couldn’t have better weather—hot, but not unbearable. A couple of evening storms along the cape kept the humidity low and temperatures in the 80s.

My favorite ritual was coffee in the garden, followed by an hour’s walk along the Lewes-Georgetown biking and walking trail, which was built on the path of a former railway line. Later in the daytime, I’d go with family and friends for short trips to both Lewes’s small public swimming beach, and the wilder, less crowded beach within Cape Henlopen Park. I had overpacked the fridge with food brought from home and made one visit to the Wednesday morning farmer’s market for tomatoes, peaches, and eggs. Never had to set foot in a grocery store. A few friends came to stay for one night, and after they’d gone, one of my sisters arrived from Minnesota to occupy the spare bedroom across the hall.

Perhaps the most magical spot in Lewes is the wildest: its cape. Cape Henlopen State Park encompasses the meeting point of the Delaware Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. Formerly military land, this 5,193 acre expanse was turned over to the Delaware park system, who have done a splendid job preserving habitat. An elevated trail that allows visitors to walk or ride over uninterrupted, wild habitat. Gazing down from the elevated trail near Gordon’s Pond, I was impressed by a group of large spiders with eye catching gilded backs. I learned they were belong to the species known as Argiope Aurantia, a much lovelier name than what most people call them: Black and Yellow Garden Spiders.

At Cape Henlopen, I saw faraway dolphins jumping out of the waves. Elsewhere in Lewes, black vultures swooped down from the sky to keep watch on garden activities . Cawing seagulls reminded us of the ocean, wherever we went. We looked up at the sky, with hats on our heads, but no masks.

Many times that week, I thought of my late daughter. I imagined her body surfing in the ocean, lazing in the hammock, and yelling at me to come look at the dolphins. She was beside me when I lifted from the oven her favorite summer dessert, peach cobbler. I envisioned her and her brother strolling down the boardwalk at nearby Rehoboth Beach, searching for French fries, and throwing the leftovers for the gulls. But I was also in the moment during the majority of the week at Lewes. I loved roaming the town and trails with my sister and having coffee with my husband at six in the morning in the garden. I was delighted by my son’s surprise reunion with his friend who sprang from the sand to give him a hug. Strolling by myself, I spent hours pondering the intricate color combinations on the cottages, and when I was tired, I lounged on the picture-perfect porch of our rental reading escapist novels.

I didn’t look at the news all week. Upon returning to Baltimore, it all came crowing in. I learned the Delta variant of the Covid virus was surging everywhere in the United States—even Maryland, where I live, and we have a 70 percent full vaccination rate. Even a few vaccinated friends had caught the variant. It seemed like the summer idyll was a brief respite that would be replaced with a return to social distancing.

This means, for me, it’s time for a sea change. I decided against attending the Bouchercon mystery convention in New Orleans this August. I started masking again when I visit stores and the gym.

I’m glad I went to Lewes when I did. And I can console myself that I can still have some of the rituals that became precious there, starting with coffee on the porch at six o’clock most mornings now through Labor Day.

The post A Breath of Fresh Air appeared first on Sujata Massey.