Sujata Massey's Blog, page 2

March 12, 2025

Where is this?

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

I traveled in India this winter. Have you been to this same place?

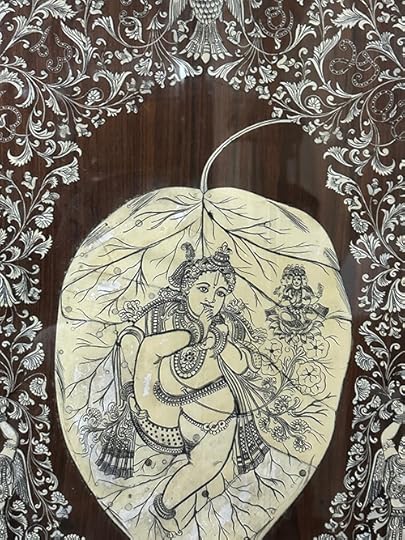

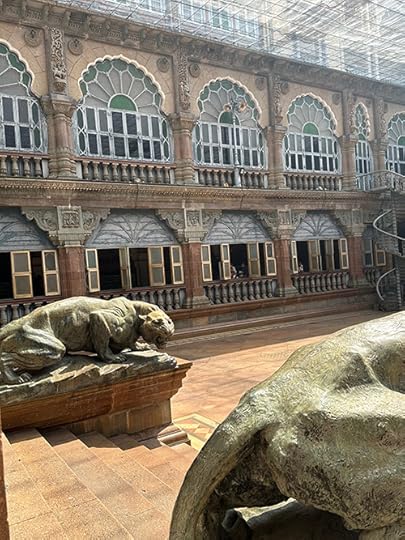

Relax! The tigers are stone

Relax! The tigers are stone Very large medallions around the lights

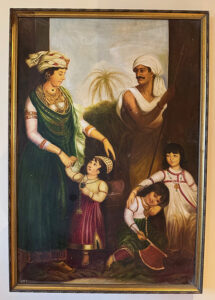

Very large medallions around the lights Sweet children, one of whom got this house

Sweet children, one of whom got this house Commemoration of British and Indian trooping celebration

Commemoration of British and Indian trooping celebration Nets over the sky keep out birds

Nets over the sky keep out birds So many grand performances happened here

So many grand performances happened here Somebody’s got to polish the throne

Somebody’s got to polish the throneSo, can you guess where I visited?

The post Where is this? appeared first on Sujata Massey.

February 26, 2025

Strolling Bengaluru, India’s City of Gardens

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Coming back from India about a month ago, I was hit with the reality of an upper respiratory virus so I laid low. And then there was all hell breaking loose in government—which continues. It took a while for me to take a deep breath and want to share the pleasant interlude of my two-week trip to Karnataka, Maharashtra and Goa. Because right now—I think we all need a vacation.

My story starts in the city of our arrival, Bengaluru. My traveling companion, the trustworthy Tony, and I arrived on New Year’s Day at 2 a.m. It took about an hour to get luggage, cash, and out the door at the airport, and then a 45-minute journey by car to the ITC Windsor Hotel, a place I had chosen because the pictures online made it look so old fashioned—the opposite of the sterile, high-tech hotels for which the city is famous. As our driver slowed to pass an old wall and gate and then up long, tree-lined driveway toward a wedding-cake-white building, my spirits rose. We passed through the usual metal-detector security to a round marble lobby with a busy front desk, where I was pleased to see clerks were present at the difficult hour of 4 a.m.

As I was handing our passports to the desk clerk, a drama was unfolding next to us between his colleague and a cluster of teenage boys, all in black T-shirts and jeans.

“I’ve booked a room. My friends are being told they can’t come up. Why’s this happening?” one boy asks, leaning over the desk, holding his American Express Gold Card like a magic wand.

The clerk, perhaps six years his senior, makes a tense reply about hotel policy limiting numbers of people in rooms to numbers of beds, but the kid won’t accept it. He’s paid for a room; he has a right to have his friends there.

Security comes, and so do more staff. The kid softens his tone and says “Look, we’ll just go into Dublin.” And although it was not said aloud—but seemed very clear—the youths would eventually leave the Irish pub and transit upstairs to the room. A number of signs—the card, the clothing, the attitude, the type of English spoken—cause me to suspect the boy came from a wealthy family, perhaps in IT.

“Very sorry about that,” the clerk murmurs after the boys are gone and we are getting our keys. A rush of late reservations meant that the hotel overbooked rooms and thus is surprise-upgrading us to the Lord Auckland Suite. Sounds fancy, I thought—and wow, it certainly was. THANK YOU!

The Windsor Hotel is built inside and out like a British colonial relic, but because it was built in 1980, it couldn’t have hosted Lord Auckland, who was Governor-General of India from 1836-1842. Opening the door, we found a 75-square-meter suite, the size of a nice one-bedroom apartment, with a large drawing-cum-dining room, and a separate bedroom with a king-sized tester bed draped in silk, and a large marble bathroom. New Year’s Eve in a hotel can be noisy, but nothing got through the walls of this room, and sleep between smooth cotton sheets on a thick mattress was paradise. Yet before I got into that bed, a mystery struck me: a plaque on the drawing room wall celebrating the room as the Duke of Cornwallis Suite. Which lord’s room was it: Auckland’s or Cornwallis’s?

I didn’t know until later that Cornwallis was the general who led the East India Company in 1790 to conquer the city and topping local ruler Tipu Sultan. For British names to linger on any kinds of marker in India is very unusual. In my mind, Britain’s 250-year exploitation of India’s resources are the reason India dropped from being one of the world’s very richest countries to among its poorest. I wondered if Bengaluru/Bangalore, which never was technically British India but stayed part of the princely state of Mysore, held less resentment about colonialism than other parts of India I’ve visited.

Just looking at the history of the Windsor Hotel—and the artworks hanging that show horses an colonial people—brings up its own story of Indians, Persians and British, Muslims and Hindus and Christians, all finding ways to make money and gain power.

The hotel stands in the place where there once was a fine Bangalore estate known as Baqarabad to some and Bedford House to others. It was built by Aga Aly Asker Shirazi, a Persian horse merchant who emigrated as a 15-year-old alongside two brothers—and their prize property, two hundred horses. The brothers brought the stable to breed and sell, an offer greeted with delight by the British military setting up a cantonment in Bangalore and also selling to the local royal family. The Askers never returned to Persia but settled in Bangalore where they found the wealthy had plenty of business offers for them—not only with horses, but also as contractors for building residences. Aga Aly Asker rose in stature and built properties for the British while buying land for himself. In late years, he bequeathed Baqarabad and its four acres to a family foundation who could monetize it as they wished. According to an article in the Bangalore Mirror, The foundation leased the property, starting in 1973, for 3100 rupees per month (about $45) to an Indian hotel company that later sold it to another company, ITC. The foundation went on to try to raise the ground rent over the ninety years of its term—but the leases were written in such a clever way that the raises have been miserly in an exclusive area of the city where apartments rent for sums comparable to New York City. I imagine that fifty years ago, the Asker family could not have imagined that there would be such a thing as a teenager with a credit card. But this is the new Bengaluru—the city that leads India for job creation, economic growth and foreign investment.

The first time I visited this city was 1973, the very year the family foundation was making its fateful decision that led a house to become a hotel. The city was still called Bangalore, the British appropriation of its name, which is still hard for me to shake. I mainly remember eating dosa for the first time and staying in a simple university apartment with friendly neighbors in the building and walking through fields nearby in the evenings with my father telling us to look out for snakes. I also remembered how calm and quiet the city was, how cool the weather, and the very tall trees with lush canopies stretching over the streets. Coming here fifty years later, I worried that all that would be gone—but to my delight, 100-year-old-plus trees still arch over streets and shade parks and gardens.

Later on New Year’s Day, we roused ourselves to go out for dinner at a cute café downtown called Toast and Tonic. I’d emailed many times and had an Instagram live conversation with Harini Nagendra, author of the Bangalore Detective Club mysteries. However, this was the first time we were meeting in person. Harini brought along her husband, Suri Venkatachalam, a biotech pioneer who’s now pursuing conservation research.

Harini’s day job is as a professor of ecology and sustainability at Azad Premji University. And between her mysteries, she’s just published a nonfiction work: Cities and Canopies, Trees in Indian Cities. Harini gave us great sightseeing recommendations for Bengaluru and Mysore and Coorg, our future destinations within the state of Karnataka. She even told us about Bookworm, a great city bookstore where she’d had events (and they promptly sat me down to sign stock). Tony and I departed back to our hotel that evening with a second wind of energy and excitement. It was undeniable that we had made a quick, but hopefully long-enduring, friendship.

During January 2 and 3, we set out with a local guide to see some of Bengaluru’s most celebrated sites. The Nandi Temple is the home of a large granite statue with an interesting history. Back in the 1500s, a farmer was frustrated that a particular bull kept eating his groundnut crop. The farmer struck the bull with a stick in the hopes it would go away. But no—instead, the bull transformed to a big granite rock. Not going anywhere!

The farmer and everyone who saw it was amazed. The stone was subsequently carved to look more bullish and a temple was built around it. Now the bull is seen as a protector. Our guide insisted that the bull has grown longer in length over the years and is still growing. It’s a phenomenon nobody can explain and that we were not about to argue with.

From there we passed on to see the modern Bangalore Legislative Assembly Building, and close to it Tipu Sultan’s summer palace.

Tipu Sultan, the son of King Hyder Ali, assumed rule after his father was killed in battle against the British. Within the state of Mysore (now named Karnataka), Bangalore has an unusually cool microclimate throughout the year. This made the perfect place for a summer palace which Hyder Ali had started, and Tipu Sultan had finished during his own reign. Walking through graceful arches into dim wooden halls of the modestly sized palace, I could only imagine the medieval sultans and their family and followers flitting through the halls. Some places have a very strong aura; this is one of them.

Just outside the palace was a Hindu temple completed in the late 17th century by a during the time Mysore was ruled by a Hindu dynasty. The Kote Venkataramana Hindu temple has many flourishes special to architecture of the Vijayanagar and Dravidian empires of medieval South India. I was struck by the grace of a Hindu temple and Muslim palace to sitting alongside each other without disturbance for so many years.

We rounded off the day with a long walk through Lalbagh Botanical Garden, a vast green space laid out by Sultan Hyder Ali in the 1700s and completed during the British colonial years. There are conservatory structures and topiaries and a stylized design very common to Indian gardens. I experienced a similar formality in the small enclosed garden on an upper storey at the Windsor Hotel. So much greenery around that place! One of the nicest experiences I had on my own was taking a short walk from the hotel past hedges of bouganvellia to Raintree, an old Art Deco villa that now housed upscale shops and a coffee shop where the lattes are dusted in edible gold.

A few weeks later, I found myself amidst the greatest concentration of trees in Bangalore. I was standing in the Kempegowda International Airport, waiting to send off my luggage, and I looked overhead to see ceiling above was filled with live shrubs. From my perspective below, it looked like several hundred of Christmas evergreens, but an airport employee proudly explained that I was seeing just a fraction of 150,000 hanging plants of various species. The terminal also had 450,000 other plants growing on walls and throughout its space. The airport also boasts a plant museum and a plant-lined walking path based on the legend of the Ramayana.

Such a combination of technical innovation and rain forest habitat is totally unexpected . . . but as I’ve learned, very Bengaluru.

The post Strolling Bengaluru, India’s City of Gardens appeared first on Sujata Massey.

February 12, 2025

What is Home in a Place Like Baltimore?

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Mural in Station North

Mural in Station NorthSometimes I like to close my eyes and just think about the various homes I’ve lived in over the course of my lifetime. While my husband and I have mostly lived in Baltimore, our marriage started off with two very unusual years in Japan. And while this blog post will be about Baltimore, it was a 1991 experience in Japan that brought me close to Baltimore’s hard history. Warning: this will be long.

We were newlyweds who thought the world would be our oyster. The search for our first marital home, though, proved that idea wrong. A few days after arriving, we left the Yokosuka Navy Base to walk into a downtown real estate office with an encouraging sign on the door promising that English was spoken. We were desperately seeking an apartment or house—one bedroom would be fine, that wasn’t fancy. I was very excited to live in Asia—but what the agent showed us was wretched.

These properties weren’t traditional tile-roofed cottages with shoji screened windows like in the books and travel magazines. Nor were they futuristic sparkling white skyscraper buildings. Instead, the realtor kept showing us laminated photo-listings of tiny, rundown apartments without heat and air-conditioning. Most places appeared to need painting and have slipshod construction. And forget about central heating: we would be expected to buy kerosene heaters for that.

The small agency’s walls also had posters showing layouts of some other apartments. Glancing behind the agent, I caught sight of a paper advertising a modern-looking 2 BR apartment. “Please, can you tell me about that apartment?” I asked, gesturing toward the wall. “It’s in our price range, and it looks nice and new.”

The realtor held the papers just in front of me but didn’t put them in my hand. Shaking his head, he said, “This apartment is for Japanese people only. No Americans.”

I was so shocked and angry that I could barely contain myself. How could property owners and real estate agents discriminate so openly? We were a polite married couple interested in staying somewhere for two years, with paperwork proving a guaranteed housing allowance would flow from the base to the property owner. Yes, we were foreigners, but we had special State Department visas for two years’ residence.

My first apartment on N. Calvert St.

My first apartment on N. Calvert St.My outrage existed because nothing like this had ever happened to me before. But it was ironic that the place I’d traveled from had the longest and most severe history of housing discrimination in the United States. I was ignorant about it because I came to Baltimore in the 1980s, the dawn of a new age when landlords only cared about your source of income and whether you had pets. The truth was that this neighborhood, the onetime Peabody Heights turned “Charles Village,” was mostly restricted to White Christians until the mid 1960’s.

Calvert Court, one of the Charles Village’s fanciest residences

Calvert Court, one of the Charles Village’s fanciest residences My apartment during my reporter years

My apartment during my reporter yearsBaltimore is the largest city in Maryland, a state that contains the Mason-Dixon line, a surveyor’s marking from the late 1700s that officially divided North and South. Maryland is one of the 13 original colonies that signed the Declaration of Independence and is tucked midway up the Eastern Seaboard. Baltimore was founded in 1729, and from the beginning slave ships used its port and sales of kidnapped Africans occurred at the Inner Harbor. Pressure from abolitionists led to Baltimore banning the importation of slaves in 1783, although slavery continued to be legal in the city and state. At the same time, a sizeable number of enslaved people escaped from states further south to live in Baltimore, and free Blacks lived here as well, working in trades and as servants, as well as teaching, law, medicine, and other professions. Banks didn’t offer mortgages to Blacks. Therefore, very few owned homes, and many more rented houses and rooms in downtown Baltimore. In the 1890s, administrators and business leaders began condemning various neighborhoods as slums and demolishing them, a process that forced Black residents into worse districts.

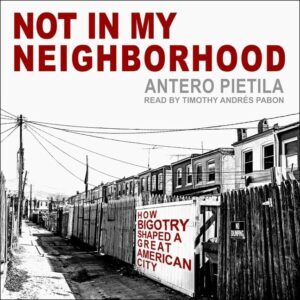

Antero Pietila, a Finland-born journalist who worked for more than thirty years at the Baltimore Sun, covered the civil rights movement and what happened afterward. Not In My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City is his 2010 book describing the long and twisted segregation of the city. His research showed that changes began in the early 20th century, when White Baltimore residents became increasingly uneasy about living nearby and began exploring ways to prevent a “Negro Invasion,” as integration was described in the Baltimore Sun.

Pietila writes about W. Ashbie Hawkins, an African American lawyer and NAACP activist who purchased a rundown house at 1834 McCulloh St from a Caucasian woman on a street that many of her neighbors were departing. After Hawkins’ purchase, more African American families came to live on the even side of McCulloh, although the houses on its odd side remained all-White. M.Z. Hammen, an angry White city resident, taunted a new Black homeowner named Hamer who bravely answered back that he had a right to live on the street and warned Hammen to move along. The outraged Hammen tried to have Hamer arrested, but a judge ruled that couldn’t be done, stating “according to the laws of the State and nation, he has all the rights and immunities of a White man.” Hammen then gathered others to campaign for a city council ordinance to make it a crime for Black people to move into a White block, and vice versa. The segregationists’ tool was an 1896 U.S. Supreme Court ruling which had seemingly established a principle of separate but equal accommodation for children attending school. The argument convinced Baltimore’s City Council, which in 1910 passed a law allowing citywide regulation of racial separation. The law was the first of its kind in the U.S., and many Southern cities quickly passed similar laws, as well as some in the West and Midwest. People charged with violating these laws were typically sent away from their homes, although there was a fine of $100 or the possibility of a year in jail.

The Baltimore law was ultimately struck down in 1913 after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against residential segregation in a segregation case in Louisville, KY. But from that point, Baltimore’s community leaders deftly shifted the weapons of segregation into the hands of developers, who made racial definition part and parcel of buying a home; and to city residents themselves who founded improvement agencies for their specific neighborhoods that specified the allowed races and religions of homebuyers.

As I’ve mentioned, Baltimore’s segregationist housing history was unknown to me when I started renting in Charles Village. I saw it as just another well-kept Baltimore row house neighborhood distinguished by architectural styles dating from the 1890s up to about 1920. Back in the 1980s, $300-$400 was the typical monthly rent for a single floor apartment in a two or three-story rowhouse. These days, sales prices for such three-story homes are now in the mid-$400K range for a single-family place, and upwards of a million for very large houses that are already broken up into multiple apartments.

Slightly south of the neighborhood and to its east side lie other small neighborhoods that have more rental housing and many more African American residents. The 32nd Street farmers’ market area on the eastern border of Charles Village was once the site of a historic all-Black school, and the streets around had been a predominantly African American village in the decades before the city line expanded northward. I came over to shop for fresh vegetables and necessary house items at Woolworth’s. One weekend afternoon, I went to a historic film theater without air conditioning and saw Purple Rain.

When I spent time getting to know people in Charles Village, I met some longtime residents who were Appalachians who’d arrived during and after World War II. Others had come from East Baltimore from the 1950s through 1970s. The neighborhood’s youngsters were mostly students and entry-level workers living on tight budgets. I loved sitting on my porch and chatting with my neighbors on their adjacent porches. As a young newspaper reporter with a $20,000 salary, I was glad to pay just $360 a month rent for a one-bedroom apartment on the second floor of a modest rowhouse with no dishwasher or washing machine or clothes dryer—and certainly no air conditioning. I had a bathroom with fluorescent-colored, peeling paint on the linoleum tub surround.

The apartment house was an investment property owned by an elegant woman from a prominent real estate family. She lived in a mansion in a neighborhood nearby and showed obvious irritation if I ever called about a problem. She seemed very different from the kindly landlords I’d had in my student days, and while it’s hard to define what exactly makes a slumlord, she did the bare minimum of maintenance. The apartment stayed “as is”—but so did my low rent for the five years I rented.

Beginning in the 1990s, the streets of Charles Village began wearing coats of many colors. One homeowner in the neighborhood painted her house in the brilliant, multiple shades of a San Francisco Victorian. She started a “Painted Lady Contest” to encourage other homeowners to paint their home’s porches and exterior woodwork creatively. The beautification of homes started on St. Paul Street, and now the candy-colored woodwork beautifies rowhouses throughout the major and side-streets.

Slightly south of Charles Village and to its east lie a number of other small neighborhoods. The 32nd Street farmers’ market area on the eastern border of Charles Village was once the site of a historic all-Black school, and the streets around had been a predominantly African American village in the decades before the city line expanded northward. Right now, merchants are doing a good job of bringing new stores and restaurants to Greenmount Avenue, and the city rebuilt its aging library branch into a great new destination. But the houses are a mix of cared-for and declining properties dominated by absentee landlords. Many in the city believe it’s a high crime area and don’t want to move there.

Another predominantly African-American neighborhood just south of Charles Village has had a different outcome. Over the last fifteen or so years, real estate agents began calling it “Station North” to advertise the walking distance of its rowhouses to Penn Station, an important stop on Amtrak’s East Coast route and also the home of almost hourly commuter trains to Washington D.C. City government and the Maryland College, Institute of Art invested in building student housing and places to enjoy film and theater. Restaurateurs arrived and made the district hot. I now traverse North Avenue—once considered highly dangerous—to engage in a Lindy Hop class in a fabulous ballroom sited in an old corner business building.

Station North residential block

Station North residential block The former Cork Factory, now housing

The former Cork Factory, now housing Copy Cat Building, now Apartments for Artists

Copy Cat Building, now Apartments for ArtistsIn Station North, tidy rowhouses and massive old brick factories have become havens to live and work in. Many homeowners have painted their homes in soft colors and some artists have painted extraordinary murals in public spaces. It’s a gorgeous sight, and it appears to be a racially mixed neighborhood with some properties still in the hands of original owners, like the one below. I’m guessing this because angel statuettes in the window are a very old Baltimore tradition.

Station North is mentioned in The Black Butterfly: the Harmful Politics of Race and Space in America, a powerful nonfiction account of the city’s history of segregation. Reading the work of its author, Lawrence T. Brown, I learned that I’ve always lived inside the majority-White spine, or L, in a city with dense African American populations spread out like wings on either side. Reading the book made me think hard about the choices I’ve made. His historical investigation reveals horrific social injustice, and also some innovative thinking for the future of Baltimore’s wellbeing.

Brown describes the Butterfly’s white-populated L shape as running from the southeast city neighborhood of Canton over to the Inner Harbor and nearby Federal Hill. The L’s long spine stretches with the streets parallel to the artery that is North Charles past downtown and Mt. Vernon through the train station area, and Charles Village to the edge of the city and its 1890s-1920s garden suburbs bearing the elegant names of Mt. Washington, Roland Park, Homeland, Guilford, Cedarcroft and Stoneleigh. These are areas with less crime and stable home ownership. He explains how African Americans were systematically moved as far from the L as possible where they had to make do with a lack of substandard housing, few work opportunities, serious health hazards and crime.

I’ve been honored to meet many wonderful people who live within or near the Black Butterfly and are working hard to improve the conditions for these deprived neighborhoods. I can understand why it would be grim to grow up here and probably have no way out. When I visit, I can’t escape seeing streets filled with mostly rundown homes, vacant lots, and graffiti. Area businesses tend to be pawn shops, dollar stores, carry-out restaurants and fast food. Only a few grocery stores exist in the Butterfly wings, and the public schools struggle to educate kids who often don’t have enough to eat and many social and environmental challenges. On every block, though, there seems to be a house with planters by the steps or a wreath on the door. People are working valiantly to make homes and rebuild the city.

Rowhomes near Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions

Rowhomes near Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions An old Hopkins medical research building

An old Hopkins medical research buildingOn the Eastern butterfly wing, about a mile from the city jail, one wealthy institution has remained. Johns Hopkins Hospital, its medical school and related buildings, have built far beyond their original 19th and early 20th century stone buildings. Streets of condemned black houses have been removed for the hospital and replaced by institutional buildings, as well as some modern rowhouses intended for mixed income levels as well as public housing projects that go back to the 1960s. Privately owned row homes are generally in good condition close to the hospital and are the homes of people studying or working there.

Just blocks away from the hospital lie hundred of houses and stores with a red diamond shape nailed to the front: the city’s marker for an unsafe, vacant property. The abandonment of houses is even worse on the butterfly’s western wings, where once-lively shopping districts are now abandoned.

Whenever I travel to old East Coast cities with well-preserved historic homes—say, Pittsburgh or Philadelphia—my knee-jerk reaction is envy. Yet Brown points out that gentrification has often displaced the poor when their landlords sell out to the new people in town—and those homeowners who stay are left with rising property taxes because of the area’s sudden changed status. In fact, Brown’s suggestion for helping distressed areas of Baltimore is for the city to bring health care, job training, and other supportive programming to people right where they are living.

Shoveling the old slate sidewalk in Wyndhurst

Shoveling the old slate sidewalk in WyndhurstFor the last twelve years I’ve lived in Wyndhurst, one of the less-fancy ‘L’ neighborhoods that is rich in trees, quirky characters and a mishmash of old houses. When we bought an 1897 house needing significant repairs In 2012, we were probably the first—or among the few—non-white families in the neighborhood. But since then many more diverse families have come to buy and rent—and we’ve never been treated as outsiders.

Part of our ongoing home restoration

Part of our ongoing home restorationWyndhurst is mostly made up of medium to small cedar shingle cottages built by middle-class merchants and tradesmen. Our home’s first owner was a married woman whose husband had a tavern at the Harbor and who was not listed on the deed. Some extra-cute little cottages in the neighborhood could have been built for some of the railway workers employed nearby. It’s all a mystery, because the neighborhood may have housed a number of journalists, but not the kind of people whose names wind up in newspapers.

The last empty lots were sold from the 1930s through the 1950s, providing additional housing styles like Colonial duplexes, Spanish, and Ranch. Several two-and three-story apartment buildings also grace the streets and our renters range from senior citizens on fixed incomes to students and young people with their first jobs to families wishing to send kids to the public school within walking distance. Wyndhurst was built so far north in Baltimore that it never had residential flight. Nor did it gentrify. Homes are often passed down in families for two or three generations, and sometimes the youngest generation doesn’t have much money to spend on repairs.

A handsome Victorian apartment house

A handsome Victorian apartment houseWhen my husband and I and our two children arrived in 2012, we might have been the first racially diverse household on our block. Nobody told us—but we looked around. As the years have passed, quite a few homes on our block and elsewhere in the neighborhood have been bought or rented by diverse families—African American, Asian, and Latino among them.

Even though my tenure in Wyndhurst is a little over 12 years, I’ve lived in North Baltimore for a total of 32 years. I’ve witnessed the blossoming of theater, restaurants, and innovations in the public schools and area colleges. I also appreciate the New Baltimore’s laissez faire attitude toward people’s nationalities and sexual identities—as opposed to other places in the country.

Whenever we have an election with city initiatives on the ballot, I vote an enthusiastic yes for bonds that will allow the city to continue restoring and sometimes removing old buildings that can’t be saved. Since the 1970s, there have been periods when the city sells abandoned houses for as little as $1 to people who commit to restoring them using professional standards. Typically, there’s a strict deadline for renovations, so the houses don’t languish as eyesores. Also, the homebuyer must commit to living in the house for a certain number of years.

When I heard that such an incentive program was up and running. I explored the requirements of the Buy Into BMore Fixed Pricing Program. The city has identified vacant houses that it bought (or could assist the buyer with obtaining) for a price of as little as $1 or as much as $3,000. A house’s upfront cost depends on how vast the vacancies are in its neighborhood and the buyer’s identity as either a prospective homeowner or a future landlord. One subcategory of the applicant pool is a program called “Charm City Roots” and is meant to serve people who have a family history connected to a particular property or street. This speaks eloquently to the possibility of displaced people coming back home.

A requirement for any BuyIntoBMore purchasers is having $90,000 on hand to spend on renovation, although the program warns the cost of rehabilitating properties is often higher. Ultimately, the buyer is taking a risk on whether others will fix up properties in the same neighborhood and make it a place they’d like to remain. Not many people in this city know about this program, and I dearly wish for them—and people living in other states and countries—to explore this affordable way to own a home and be part of rebuilding a city.

The post What is Home in a Place Like Baltimore? appeared first on Sujata Massey.

January 29, 2025

The Sun Also Rises

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Sunrise in Coorg, India

Sunrise in Coorg, IndiaI’d planned to write in detail about my travels in India, but it’s been a hard day for me to concentrate. In Washington D.C. , the new administration appears to want to shut down many of the services the Federal Government provides to the people. An erasure of historical achievements by women and people of color; an attempt to rewrite the rules of who can be a citizen. All of it too staggering to follow. I wonder if you feel the same?

So my desire to write turned into a wish to share few moments of peace and beauty that I found on my trip. I found myself close to the founts of life on earth, the sun and the water.

Greeters of the sunrise on Marine Drive, Mumbai

Greeters of the sunrise on Marine Drive, MumbaiIn a city as busy as Mumbai, hundreds of people turn out every morning to watch the sun rise over the Arabian Sea.

View from the train between Karnataka and Goa

View from the train between Karnataka and GoaThis view of agricultural fields and water, seen from the train as I traveled along the Konkan Coast, had no people around.

The train journey from Mumbai to Margao, Goa, continued with hundreds of miles of tranquil views. Watching the landscape was so mesmerizing that a 9 hour journey felt much shorter.

Every color in the rainbow melted into this melange at Benaulim Beach in South Goa. And it feels good to know that sunrise and sunset are daily events that cannot be made redundant.

The post The Sun Also Rises appeared first on Sujata Massey.

January 1, 2025

A Fashionable New Year: Carry-on Tips for India

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Happy New Year’s Day! And think of me right now, rolling along the streets of Bengalaru with my carry-on suitcase.

Hopefully, all that I’ve crammed into the hardshell for a 2-week trip will actually get worn. Packing is an acquired wisdom, and every trip I take teaches me something. The white lace blouse that summons fantasies of sweet lime drinks on the veranda never left the hanger. The flat, platinum-colored leather Taos sandals—oh, my gosh, yes, tromping everywhere from fancy restaurants to the museum and beach.

The most useful travel wardrobes are not organized at the last minute; it’s a matter of laying clothes out and writing it down, to see redundancies and omissions. A lot like editing a book, isn’t it? But the reality is that as much as I enjoy packing, I still sometimes don’t wear one or two items and yearn for something left at home. What will I really use over 14 days that when I’m in city and country, cool hill stations and hot beaches, churches and restaurants, unpaved village roads and Apollo Bunder in Mumbai?

The Bangalore Palace

The Bangalore PalaceOver the next two weeks I’ll arrive in Bengaluru, once known as Bangalore. After a couple of days’ acclimation, we will take a car ride through Karnataka to the old royal enclave of Mysore, and then climb into a misty cool hill station named Coorg.

Coorg Wilderness Resort Hotel

Coorg Wilderness Resort HotelThen it’s back in the car to the Bengaluru Airport to fly to Mumbai, where it’s two nights of research and visiting friends before taking a train to Goa for almost a week’s stay. On day 14 we fly Goa-Bengalaru-Washington DC.

The trip was originally intended for some India train research, including a 5-night ride on the Golden Chariot, a tourist train with overnight compartments. However, this plan derailed (haha!) due to a low number of reservations. Because Indian Railways was the one that cancelled, I got the deposit back and had to figure out another way to use my scheduled time in India.

Silva Heritage, a Goa 300-year-old dwelling turned hotel

Silva Heritage, a Goa 300-year-old dwelling turned hotelI’ve been reading Around India in 80 Trains, a delightful travel memoir by Monisha Rajesh. Through the many train rides Monisha describes, I got the idea of taking a regular train from Mumbai to Goa, which is a particularly scenic route. There’s an express train taking this route with a special passenger car that has all-glass walls and ceiling, for maximum viewing of the Konkan coast. So the Vistadome car will be the first train ride of this trip. I’m hoping for a few more excursions on regular trains once we reach Goa.

I try to travel to India every 10-15 months, and typically I’ve used a larger checked suitcase because I’m carrying about 10 books as gifts. This year, I didn’t have a new book to carry—so that means less weight and room to worry about. Also fueling the bring-less mindset were a few videos on YouTube about a so-called “three-day-method” and “5-4-3-2-1 method” that encourage people to really pare down their clothing choices. That’s the way I’m going: with one carry-on and a personal item. Here’s what I’m bringing in terms of tech, clothing, and extras.

TECH PLAN: Hooray! The personal item tote-bag will be a lot lighter on my shoulder because I’m not bringing a laptop. I’d like to be more unplugged and thus am bringing an iPhone and charger only (my husband will have an iPad he promises to share). My phone carrier, ATT, charges $10 a day to use my phone abroad. This might seem pricey, but I’ve had really bad experiences over the last 20 years spending hours and days trying to buy local phones in India that inevitably are very hard to use. The other thing I’ve tried was bringing one of my old cell phones and buying a SIM card at the airport that turns out to work very poorly if at all. So, I’m sticking to ATT. This will be the third time I’m using my phone this way, and I’ve found the trick to it working seamlessly is to go to settings and set the roaming feature to default to the strongest network, which for me has been JIO. if you don’t set a default, the phone will keep scanning for random networks. Be sure your number is shared with your India contacts through What’sApp, so they can call you without incurring charges.

Charging phones and tech is also tricky because of India’s 230 voltage versus USA’s 110. Supposedly Apple devices have universal plugs, but I’ve had a MacAir laptop motherboard fried and needing a full replacement in India. My husband and I have also blown out the circuits at multiple hotel rooms trying to charge laptops and iPads. If anything bad happens to your Apple tech, don’t attempt a repair without going to an Apple Store to keep your repair warranty safe. However, this process could take days, as authorized Apple retailers even in locations like Mumbai may need to get the part sent from Delhi. To avoid emergencies like this, use converter plugs meant for India’s current AND charge your power bank on these plugs, so the risk of something adverse is limited. You can safely charge your electronic items using power banks only. I’ve been OK charging my phones straight into the converter (fingers crossed, always). Finally, you might want to add a VPN app to your phone to protect your data from being swiped. Tony and I are sharing a VPN for one months’s time that covers 5 devices for just $15 total.

A favorite airy travel top from Ritu Kumar

A favorite airy travel top from Ritu KumarCLOTHING: Clothes are certainly not as complicated to plan as tech. My mantra is to always be yourself and stay comfortable. That said: unless you’re an Indian male, if you wear a backpack, a ball cap and athletic shoes on the streets, you’ll likely be identified as an American or British tourist and receive a particular kind of attention. I don’t like having an entourage, so I dress as well traveling as I would at home. For instance, I always wear loose blouses, skirts and trousers out in town, although I’m very comfortable in shorts and a bathing suit at the hotel (with a cover-up over the bathing suit when not in the water or the pool chair).

While saris have made a comeback with some fashionistas, typically Indian women wear flowing trousers with longer tops, or skirts and dresses made in India from beautiful silks, cottons, and next-level synthetic textiles. To buy something while there, look at stores like Fab India, Cottons or Ritu Kumar. Every city will have a few boutiques like this and big malls have better quality options than street stalls. Many of these garments are embroidered and stitched by textile artists in villages, so you can be fashionable and local at the same time.

salwar kameez in Kolkata years ago

salwar kameez in Kolkata years agoYears ago, I wore salwar kameez (tunic, stole and pajama trousers) outfits quite a lot in India. But street style has changed and these days, I keep traditional ensembles for important social events. I’ll always bring a beautiful long silk dupatta to work as an outfit accessory, providing extra style as well as comfort in air-conditioned places. Aside from this, my general choices are wide-legged pants, whether cotton from India or quality denim from the US; loose fitting tops that aren’t low cut, and skirts that cover the knee. I bring one pair of clean, colorful sneakers for travel, fitness walking and sightseeing, but a pair of worn-in Taos flat sandals in a metallic leather works just as well.

Please do wear jewelry in India; I’ve made the mistake of forgetting to pack any earrings and necklaces and felt like I was partly dressed in comparison to local women who always have something pretty at the neck, ears, wrist, and sometimes the nose. Jewelry and scarves are wonderful things to buy in India; I particularly recommend going to cottage industry stores representing the state you visit, and the reasonably priced modern fine jewelry chain store called Tanishq. I’ve even impulsively bought fine jewelry at the airport shops on my way out of India. You should not leave India without buying at least a little jewelry!

For the plane I’m wearing the same outfit I usually bring for a winter trip to India: my red Taos Carousel canvas sneakers, Anthropologie’s Maeve wide-leg jeans, a long sleeve red-coral-white silk blouse from Johnny Was, and a gray cashmere ruana from Quince to also serve as a blanket.

Here is the rest of my packing list. I really did get all of this into a small carry-on because I use compression cubes (hardshell carryon case and compression cubes from Quince, if you are the market for something new). Almost all the tops and bottoms can be mixed.

Loose cream straight-leg polyester pleated pantsGrey cotton capri pantsBrown tech poly jogger pantsBlack-white patterned shortsAnkle-grazing dark blue-print polyester skirtBlue and coral printed wrap skirt, knee-lengthMid-calf burgundy silk skirtCasual Blue cotton gauze dress/swimwear coverupWhite crinkle poly blouse, sleevelessWhite button-down shirt, sleevelessBlack T-shirt (borrowed from spouse)Coral cotton broadcloth button up blouse with mid-length sleevesNavy blue silk short-sleeved topNavy blue cardigan1 Bathing SuitUnderwear for 6 days (will use laundry and detergent packages)3 pairs socksFlat packing hatTwo scarves: one short chiffon square, one very long rectangular dupattaCoach Whitley Mary JanesTaos Trophy sandalToiletries galore, small sizes in a waterproof carrying case! Be sure to include mosquito repellant wipesEXTRAS SUCH AS GIFTS: If you’re going to someone’s home or meeting someone professionally, it’s very nice to bring them a gift from the U.S. Signed books by you or others are enthusiastically received. Other items I’ve liked to bring are packaged nonperishables from Trader Joe’s or similar yummy specialty stores. Warning: chocolate always seems to melt. This year I’m bringing a special American biscuit baking mix, two candles, and some specialty nuts. Just three gift books will be making the journey…and because of my packed carry-on, I’ll have to ask my husband to be responsible for them.

May the new year bring everyone happiness, and perhaps a special trip! If the packing’s done over the course of three days, the hardest part of leaving will be saying goodbye to your pet.

The post A Fashionable New Year: Carry-on Tips for India appeared first on Sujata Massey.

December 4, 2024

Happy Early (Hmong) New Year!

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Last week, I drove from Baltimore to St. Paul, Minnesota to be with family for Thanksgiving.

To my surprise, I got a bonus holiday: Hmong New Year. And what a gift it seems to live in a country where people have arrived from so many different parts of the world to share their traditional food, music, art, and other gifts. Public admission was just $12—how could I miss the party?

The traditional lunar calendar observed by Hmong people marked Saturday, Nov. 30 as the last day in 2024, and Dec. 1 as actually New Year’s Day. Hmong New Year’s beliefs are tied to ancestor remembrance and the renewal of shamanistic energy. Yet the Hmong New Year I experienced with my outsider eyes was a very jolly celebration with upwards of 40,000 people streaming into River Centre, a huge convention hall in Saint Paul, MN. I was dazzled by the colors and complex embroidery of clothing worn by women, men and kids. The jingling of thousands of silver coins and strands of pearls on people’s clothes filled my ears. I marveled at the complexity of different hats and the festive high heeled shoes many wore to set off their finery. It seemed the most popular color was pink—often accented with green and black. Brilliant!

St. Paul happens to be of the largest population bases for Hmong in the United States; Fresno, California, is the other location. The largest New Year’s celebrations are housed in these cities, and the one in St. Paul was billed as United Hmong Family Reunion, a coming together of members of many different tribes. The Hmong people have traveled far over the centuries from their original Hmong kingdom in North China to different parts of Southeast Asia, most famously Laos. Some Hmong people still do live in China—but because of past persecutions including the suppression of language, many fled to start new lives in independent agrarian tribal communities elsewhere.

A second exodus occurred in the 1970s and 1980s. During the Vietnam War, the American military enlisted thousands of Hmong men to help fight a shadow war to suppress communism in Laos. When the Americans withdrew from that unwindable war, the Hmong remaining in Laos were in mortal danger. The first groups of Hmong military families were airlifted in the 1970s, and many other Hmong families swam, floated or boated across the water to a refugee camp in Thailand, where they lived for years until refugee visas were finally issued by the United States. The first refugees were settled in a scattershot approach in several states. In the 1980s, Lutheran Social Services and Catholic Charities in Minnesota accepted government contracts to oversee resettling Hmong families here. After that, Hmong living in other parts of the US chose to relocate to be near family members and because the city of St. Paul has largely been a friendly place to settle.

In the 1980s and 1990s, I met Hmong people selling beautiful vegetables and gorgeous embroidery at Twin Cities farmers’ markets. Some very special ornaments on my Christmas tree are fabric embroidered in famous Hmong reverse applique patterns. It was exciting to see so much bright clothing for sale at the RiverCentre and to be gifted a free book about Hmong Textile Art when I stopped to chat at the Hmong Cultural Center, a group that supports traditional culture and also helps people secure citizenship. I also met young Hmong-Americans running an early childhood education program that aims to make young children feel good about their heritage, and helps the adults involved in their education learn about Hmong family life. Several tables were staffed by the St. Paul police and similar agencies looking to hire. I learned this was the 44th Hmong New Year celebration in Minnesota—and that the anniversary of Hmong resettlement in the United States is 50 years as of 2025.

The deepest current I sensed was that of playful socialization with old and new friends. People lined up to toss colorful fabric balls back and forth to each other. Turns out this is a popular game at New Year’s that’s also a way for young men and women to signify romantic interest. An American-style beauty pageant for Hmong women took place on one stage, while youth dancers in fantastic costumes and makeup performed traditional dances on another. A food hall sold Hmong favorites like sesame balls, stuffed chicken wings, pork sausage, and a vermicelli-beef noodle soup fragrant with lemongrass and mint.

I lingered outside traditional thatched bamboo Hmong house where families posed for new year’s photographs. It seemed that under this roof, a traditional way of life was proudly remembered; an experience that many of us share during the holiday season.

The post Happy Early (Hmong) New Year! appeared first on Sujata Massey.

November 20, 2024

My Morning Shift

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

A few weeks ago, I had the fun of interviewing a literary lion in Washington DC—and I received a gift that went far beyond the signed copy of a book.

Sir Alexander McCall Smith was touring the United States in support of one of his newest novels, The Great Hippopotamus Hotel, and organizers at the Hill Center, a Capitol Hill landmark building, invited me to ask him about a quarter century of writing all kinds of books.

I’ve mentioned McCall Smith’s newest novels in plural. In 2024, he’s released three other books: The Perfect Passion Company, a comic novel about matchmaking set in Edinburgh; The Conditions of Unconditional Love, the fifteenth book about philosopher Isabel Dalhousie; and The Stellar Debut of Galactica MacFee, another epistle in the Scotland Street social satire series.

The lecture room at the Hill Center was packed with almost 100 rapt fans who’d all properly reserved seats ahead of time, with some waitlist members crowding the edges while standing on foot. Everyone was all smiles. Sir Alexander is a true Scottish gentleman and an excellent joker. He’s not one to toot his own horn, but he did come forward and answer my questions about his work, including the fact he doesn’t know the total number of books he’s written: just that it’s over one hundred, and that he averages the publication of three or four books every year.

Writers who have joyful careers running at high productive speed are often asked for advice about how they manage. Alexander McCall Smith shared that he doesn’t have to revise much because his brain delivers sentences to him in a stream-of-consciousness fashion—they come to him just as they appear in print to us months later. He described being in a mild dissociative state when he works, writing about 1000 words (or four pages) per hour.

People’s eyes widened when he described beginning his workday very early—sometimes as early as three in the morning, which he described as a melancholic time also known as “the hour of the wolf.” Instead of lying in bed feeling frustrated at having the interrupted sleep, he gets up to write. And generally, he is done with all of the day’s writing before lunchtime.

I’ve been an early riser for a long time—but my habit has been to go through a lengthy morning routine before starting to write. This looks like coffee, journaling, dog feeding and walking, tidying some rooms and putting in a load of laundry, and cooking a real breakfast. Oh, and perhaps a glance at the papers and five minutes watching Stephen Colbert reruns online with my husband. You can quickly see that writing gets shifted to the end and sometimes I’m lucky to have an hour and a half for writing before heading out to lunch or an 11:30 gym class.

That was BEFORE talking with Alexander McCall Smith. In the last few weeks I’ve risen when I wake, usually between four and six am. I have the first half of my coffee in front of the fire, and then I take the cup upstairs to my study and turn on the laptop. I work for a solid hour before thinking of breakfast and anything else. And I must say: I’m writing faster and better, and I still have the interest to write more in the morning, even after breakfast and the dog walk. If I wake way too early—say 3:30 AM—I will find myself rising if I can’t return to sleep within 30 minutes. And I read or write then for an hour, and I go back to sleep. My brain is fine with this routine, as long as I give it space for a cozy afternoon nap (early afternoon, so as not to screw up falling asleep later).

I’m also reading a productivity book called Hyper-Efficient by a researcher named Mithu Storoni. Dr. Storoni has pulled together many research studies on brain performance to develop her original framework of three gears for the brain, ranging from highly focused to scattered, and also a flexible stage in which one can flip from different focus areas. You can’t change the gear your brain is in at the moment; but you can recognize what’s going on internally by planning tasks and relaxation around your own clock.

In gear theory, early morning is the time the brain can most easily sink into a creative well. For most of us, though, this prime time is spent eating, helping others start their day, and traveling to work. As the day goes on, our brains will always become fatigued—it’s not a personal fault. Yet our brains can regain focus and happy strength following 15-minute breaks with different kinds of activities. For instance, writers who’s had their eyes locked on a screen would probably recharge best by taking a short walk that brings their eyes to rest on trees and sky and nature. Someone working with very difficult information or tense, unpleasant personal interactions (say at a hospital or a tollbooth) might recover their emotional reserve taking Instagram breaks scrolling cute animal videos.

I was flat-out thrilled to have it confirmed that the most successful way to initiate intellectual activity later in the day is following a nap. Storoni found that late afternoon is the second most efficient period in the day for most brains. Because my day started at four today, and included a midmorning water aerobics session, I’d worried that I might lack the energy the to write this blog post later in the day. However, after lunch I napped for an hour, and got up to have a cup of green tea and started writing without any kind of hesitation.

I’ve been blogging for Murder is Everywhere on alternate Wednesdays for ten years. There are days I’ve regretfully missed posting because of writing deadlines and my inability to shift to a second project on the same day. I’m also very different from Alexander McCall Smith in that I haven’t got multiple publishers expecting me to write various novels and short stories in the same calendar year. I am satisfied researching, writing and revising a book every eighteen months (although the publishing cycle sometimes draws the book’s release a bit longer).

My chance encounter with a veteran novelist, and the coincidences in his working style with brain’s circadian rhythms, have been illuminating. Now I’ve got a plan of how to make use of my chronic insomnia, and I can accept that I can’t force my brain to run when it wants to rest. Taken together, all of it goes a long way to make writing more enjoyable.

The post My Morning Shift appeared first on Sujata Massey.

November 6, 2024

Cooking My Way to the Finish

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Williamsport, PA, Nov. 5

Williamsport, PA, Nov. 5So, Nov. 5 came and went. Even though I am writing this the evening of the election, I expected that not all states will have certified results by the morning after, just as it happened in 2020.

I know that delayed news is better to me than outright bad news. UPDATE: I woke up to the news that Trump won. And I’m so very disappointed.

We all have to live with anxiety and uncertainty—no matter which side of the political spectrum we are on. And I suspect a lot of us have suffered very serious uncertainty in our lives; for instance, worrying about someone in the military, or someone seriously ill. I tend to worry more about others than myself, and I don’t know whether this is a good or bad thing.

As with regard to worrying, It’s taken decades for to understand that worrying won’t stop anything from happening, good or bad.

Leading up to this election, many of us who cared did the best we could. I tend to throw myself into doing things outside the house when I’m anxious about something I can’t control. Therefore, I became a campaign volunteer on weekends. I canvassed for voters, which meant going door to door to talk with people, if they are willing, and leaving campaign literature. On Tuesday, I drove to a central Pennsylvania mountain town, Williamsport, to help with whatever they needed. Turned out it was doorknocking—in my mind, I had thought I might be a driver to polling places. This was simple and straightforward work, and I appreciated how the addresses were easy to find in this old-fashioned industrial town. I did not find many folks at home—except for children, who had the day off because of the election.

Of all the volunteer shifts I’ve had, this one was the quietest with the fewest volunteers, and I was aware it was in a county that would very likely give the majority of votes to Donald Trump. The volunteer headquarters was in an interesting old factory building that at one time manufactured more pajamas than any other place on earth. Now it is mostly space for community and artists. Just a few days earlier, strangers had come by and noticed a truck with Harris-Walz stickers parked outside the Pajama Factory. The people spray-painted obscenities about Kamala Harris on the truck and then set it ablaze. I heard it from the skeleton crew of volunteers in the building, hoping for the best. And when I traveled through the neighborhoods, seeing the number of people who hadn’t yet voted, I had a very sad feeling that they wouldn’t go.

The sun set and I put an audiobook on to play through the speakers of my car. I drove home along the small highways to Baltimore, just two-and-a-half hours to my destiny of waiting safely at home with unsafe emotions. As I mentioned, being at home has not felt relaxing lately. As a result, I haven’t cooked much and the fridge is almost bare. Recently Tony had left in the snack drawer a half-bag of kettle chips, carefully sealed with a clip. He came asking me later if I knew where the bag was, and I had to admit that I’d eaten it all.

We are often lectured that eating in times of stress is an unhealthy habit, but I think it’s a lot better than some other ways of coping with unease. We all have our strategies.

Stuffed Shells at my Baltimore House, Nov. 5

Stuffed Shells at my Baltimore House, Nov. 5I’ve had the feeling since Monday that I wanted a few casseroles in the house for emotional protection. I knew I wanted something I hadn’t made in a year or two: a rich, saucy lasagna. I pictured a large baking dish filled with a casserole of cheese, tomato, pasta and spinach. The kind my mother made. A large amount that would create leftovers that I would be able to reheat and eat to my heart’s content, yes, maybe with a little salad on the side, and maybe dessert.

I realized that nobody had the time to make this dream lasagna for me. So, on Monday, I tried to buy ingredients at my local store. Unbelievably, there were no boxes of the flat, wide strip noodles used for lasagna. It made me wonder if others are going through the same kind of cravings. I’ve always thought that ricotta-and-spinach stuffed pasta shells are practically the same. The large shell noodles, conchiglie, were on the shelf, so I grabbed them.

At home I just parboiled the noodles, filled them with a mix of lightly sauteed spinach (1 box defrosted from frozen) and enough ricotta, parmesan and provolone cheese to suit my taste. Half of the cheese mixture was suitable for me (vegan or low-lactose cheeses) and the other half was bring-it-on full fat ricotta for Tony and Neel.

I made a happy arrangement of conchiglie in an 11×9 ceramic baking pan with a little tomato sauce on the bottom. Over that I poured about 3 cups of sauce (one cup chunky homemade and two cups good quality marinara). Then I covered the casserole and put it in the fridge for election night. And when I got home from Pennsylvania a few hours ago, weary from the driving, I opened the door and smelled tomato, onion and cheese.

Having a hot dish waiting at home for me, during the difficult time I’m waiting for news, made me feel a little more comforted. And the very act of cooking good things strikes me as an act of faith. It means that I can take care of my own needs and sustain myself to go on, no matter who is in charge of the country.

The post Cooking My Way to the Finish appeared first on Sujata Massey.

October 23, 2024

LOTUS FOR POTUS: Election Canvassing in Pennsylvania

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

The air was warm, and the sky so blue. Tall trees showed off crowns of red, orange and gold leaves as I cruised along Interstate 95 last Sunday morning.

Despite it being prime leaf-peeping time, I wasn’t taking a scenic route for idle pleasure. Pennsylvania is a swing state in the coming national election; some say it’s the state that Vice President Kamala Harris must win in order for the electoral college to line up in her favor. I’d heard about a massive canvassing day in Montgomery County, an area north of Philadelphia with slightly more Democrats than conservatives. My intention was to wind my way into North Wales, a town within the county, to deliver literature and perhaps a few words to possible voters.

The last time I canvassed was in Minnesota during the 2008 election on behalf of Barack Obama. During that long-ago fall, I carried a paper list and door-knocked in the tightly knit neighborhoods of Minneapolis, and the suburb of Eden Prairie, where the distance between houses was greater. I had chatted with Democrats and Republicans alike, because sixteen years ago, people were more relaxed about speaking with strangers. And we weren’t so polarized. Would canvassing work, in this day and age? And now it was so much more complicated, involving data entry into a smartphone.

The night before my drive, I’d received a text with instructions to add a voter canvassing app called Minivan. Now, it’s one thing to double-click an app onto your iPhone, but quite another to use that app skillfully. Minivan’s video tutorial showed how a map of houses would pop up when I was on the street, and how I’d be able to key in information such as whether I made contact, dropped literature, and any details the residents voluntarily shared about their voting plans. Minivan also had a built-in geographic tracker of where the phone was, something that made me feel a little more secure about the unknown encounters ahead.

I reached the Montgomery Mall in North Wales in less than two hours, faster than Apple thought it would take. And walking into this vintage suburban mall, I realized I’d visited here twenty years earlier with friends to take our children to a Harry Potter movie. The suspenseful opening credits and thundering film score brought my daughter to tears, so we all fled the mall’s AMC theater and soothed the miserable at a candy stand, which was still there. I hoped this memory was not an omen that I’d once again back out of the mall without fulfilling a mission.

Montgomery Mall seemed to have few visitors on a Sunday morning, just like many enclosed malls around the country today. The Harris-Walz campaign had rented a storefront for its purposes. This former shop was filled with volunteers, signs and totebags. I signed in and was off to sit at a table where a kindly man was giving a hands-on Minivan tutorial. Just what I needed. I also breathed easier when another volunteer appeared and said she’d be glad to partner with me while door-knocking. My partner was a lovely woman who had Minivan down cold without needing instruction. She also was a Perveen Mistry reader. What were the chances?

My partner and me

My partner and meWell, we both had connections to India. This particular rally and canvassing effort was organized by Indian American Impact, a national organization that raises money and gathers volunteers to support South Asian American candidates up and down the ballots.

There are certainly conservative South Asian voters who support Trump, but the majority of South Asian voters lean Democratic. Kamala Harris has both Jamaican ancestry from her father, and Tamil ancestry from her late mother, who was born in India. The name Kamala is Sanskrit for lotus flower. I bought a catchy LOTUS FOR POTUS bumper sticker from Impact’s merch table, which also had wonderful tee-shirts with expressions like Desis Decide and Kamala Ke Saath (together for Kamala). How important is the South Asian vote in this campaign? Recent articles in The Washington Post and New York Times focus on the nation’s largest and most affluent immigrant population. Close to 400,000 South Asians who are eligible voters live in the swing states.

After the buses carrying volunteers from Washington DC and New York City arrived, it looked like the crowd was pushing a few hundred. The people were of all ages—from children tagging along with their parents to well-dressed gentleman in their seventies. Volunteering also was not limited to South Asians; I saw Black and Caucasian and East Asian faces in the room. Yet the vibe at the gathering was distinctly Desi—the unifying nickname for South Asia that comes from the root word “Desh,” or homeland. Being a Desi means having roots on the Subcontinent, no matter how long ago your ancestors left.

Healthy snacks included samosas and chai

Healthy snacks included samosas and chaiOn Indian American Impact’s website, I found they were endorsing 48 candidates running for political office nationwide. These people were aspiring for jobs ranging from city council positions to judgeships and Congress and the Senate. Impact does not expressly align itself with a political party, however it mentions that its core values include advocating for healthcare, climate and environmental safety, immigration, voting rights, and racial justice. They also don’t rubber stamp every politician who has South Asian ancestry. For example, Nikki Haley, a former Republican governor and a losing candidate in the Republican presidential primary, wasn’t on the list.

Among the passionate speakers at our rally was Nina Ahmad, a Bangladeshi immigrant who is both the first Muslim and first Asian-American elected to the Philadelphia City Council. Nina reminded us to tell immigrant voters leaning Republican that while in office, Trump created a de-naturalization section within the Department of Justice that enabled government to strip Americans of citizenship. Recently, Trump has spoken of weaponizing the Justice Department and actively sending away legal immigrants, starting with Haitians, through a concept called Remigration. Imagine how this tactic could be employed at will against all green card holders and naturalized citizens!

Neil Makhija and Padma Lakshmi

Neil Makhija and Padma LakshmiNeil Makhija, a vibrant young man who was elected as the first Asian-American Montgomery County commissioner (there are three), also got us fired up with a discussion of local politics. Makheja had been sued three times already by the Pennsylvania Republican party for organizing a voter registration van and ensured voting information was printed in eight languages. “They sued me for making it possible for people to vote!” he said. His New York Times editorial about the importance of voting and the ironclad security around ballots is excellent.

Washington State Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal was on hand to push us into motivation, including the now-famous chant, “We’re Not Going Back.” We heard a moving song performed live by the Broadway composer/singer Ari Afsar, backed by a talented South Asian student a cappella singing group from Penn State. Padma Lakshmi, who celebrates foods and diverse cultures on her Hulu series, “Taste the Nation,” explained why she supports Kamala Harris, and also why she thinks Donald Trump is so dangerous for the country.

A volunteer meets Pramila Jayapal

A volunteer meets Pramila Jayapal Padma Lakshmi in action

Padma Lakshmi in actionForty minutes after arrival, my new pal and I headed to her car, loaded with some election literature, and with our phones playing Minivan.

The first two households were apartments on the back of a restaurant building. Nobody answered the door, so it was a rather anticlimactic feeling. Had we even reached the correct doors? We continued on to a townhouse community. Here, on a street called Susan Circle, we had a list of 58 households. All close together, all well-numbered; excellent.

Going with a companion from door to door in the sunshine was quite a bit of fun. We saw great Halloween decorations, containers planted with fall chrysanthemums, and windows that were sometimes opened for conversation with us—or used as a way to see what we were up to. I understand that solicitors aren’t welcome on most doorsteps, including my own. Therefore, I felt very grateful for the people who were brave enough to open their doors and listen to our spiel:

“Hi, we’re here to check if you are planning to vote…that’s great, will it be early voting or on election day? Do you feel comfortable telling us who you’re planning to vote for? … That’s wonderful… And will you also support Senator Bob Casey?”

When we met people who said they hadn’t made up their minds, one of us might ask, “What issues are important to you in this election?” We’d both listen and reflect back to them what they had expressed. “That makes sense. Did you know…” We were careful not to make speeches.

In this neighborhood, we chatted with many Asian Americans, many first or second generation immigrants. We had a conversation with a white woman who said she was grateful her boss made it clear to all his employees that they could take time on a workday to vote; she was voting for Kamala, and so were most of her co-workers. We also met a young white man who opened the door and held a whispered conversation with us because of conservative people nearby. He said he was voting for Kamala because of his girlfriend, and the importance of women’s rights over their bodies. I thanked him for it, just as many of the residents thanked us for volunteering.

Those were very heartening moments. There were also some laughs. We couldn’t even begin to ask questions when an East Asian lady (probably in her eighties) opened her door, took one look at the two of us, and shouted: “No, no! I don’t want that. I’m voting Trump!”

We had another humorous encounter when we rang the doorbell on a nearby house. Eventually a second floor window was raised, and we saw the sliver of the face of a friendly boy who looked and sounded under age eleven.

Boy: “I can’t open the door because my parents aren’t home.”

Us: “No problem, we understand. Is it OK if we leave a piece of information at your door?”

Boy: “Go ahead.”

Sharp unknown adult voice: “No! Don’t leave anything!”

As we crisscrossed Susan Circle, Minivan cheered us on: “You’re 25% done!” until we completed our list. It turned out that we had made personal contacts with 26% of the households on the list, something to crow about because the Indian Impact volunteers told us that a 10 percent rate of personal contact was typical. I suspect the sight of two women made people more curious than wary. Although—as my partner pointed out—the Amazon delivery truck did roll through and help us get people to the doors during our last half hour of service.

Would I canvas again? I am signed up for next weekend, canvassing for Angela Alsobrooks, the Democratic Senate hopeful in Maryland. A slow stroll for three hours seems a small effort to make in exchange for some memorable encounters. And if these meetings will encourage a few uncommitted people to think more about making a choice—and knowing the importance of voting—I’m very satisfied.

Sujata will mail a free signed book to anyone in the US who door-knocks for Kamala Harris before November 5. Visit her website, sujatamassey.com, and email her with subject line Canvas for Kamala. In your email to me please include a selfie of you at the canvassing headquarters; your home street address; book of choice and optional personalized inscription. Thank you!

The post LOTUS FOR POTUS: Election Canvassing in Pennsylvania appeared first on Sujata Massey.

October 10, 2024

The Delaware River’s Almost-Twin Sisters: Lambertville and New Hope

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

I walked all the way from New Jersey to Pennsylvania this morning.

It was a breeze—taking just about 10 minutes to stroll across the historic 1000-foot bridge between two charming small towns: Lambertville on the Jersey side, and New Hope in Pennsylvania.

Even though I’ve always lived in cities, my heart melts when I explore small towns. I feel myself go back into the books I loved in childhood when I walk narrow streets, peering over old iron fences into pocket-sized gardens. It all tends to work when there’s money involved; when people have a profitable reason to preserve their buildings, and interesting tenants move in to serve meals, sell antiques, and display adorable items in the windows.

Not every old town gets such a chance. Very likely the special bridge linking two places was a factor. Lambertville is a little more shopping heavy, and New Hope has a few more water views and cultural meccas—but both make a wonderful day or even an outing for a few hours. And what a magnificent view for a walker from the bridge’s center!

Ten thousand years ago, this gorgeous area was home for the Lenni-Lenape Native Americans. Lambertville became a Western settlement around 1703, when agents for the council of West Jersey bought the land from the Delaware Indians. The Europeans then subdivided the land to farmers and developers. Ferries, taverns, and shops sprung up here and in the town across the water, which were then called Coryell’s Ferry. The area that I casually explored was an important outpost and crossing point for George Washington’s troops in the War for Independence.

New Hope was founded in 1710 with a land-grant from William Penn. It was the halfway point between Philadelphia and New York City and an important location for train and boat travel. Mills harnessed the strength of the Delaware River, and trains running goods from here throughout the country. Lots of 19th century buildings of brick and stucco add their own grand flourishes to the housing landscape.

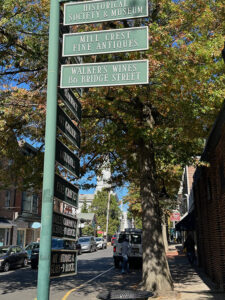

Here’s a peek at the 1840s Amwell Masonic Lodge, now shops, on Bridge Street in Lambertville.

My heart was stolen by the cute Halloween displays in this vintage business—and in at the windows of almost every Lambertville shop.

This old mill building close to the river on the Pennsylvania side made me swoon. I expected someone to emerge wearing a long dress and bonnet and carrying a pail, but at least I saw ducks.

Parryville Mansion, home of New Hope’s founder, is a place to explore.

Too many choices of charming ways to go!

There is nothing more gorgeous on an old stone building than a brilliantly edged window.

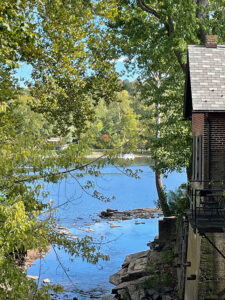

I remain at the water’s edge, contemplating the prospect of my next visit!

The post The Delaware River’s Almost-Twin Sisters: Lambertville and New Hope appeared first on Sujata Massey.