Sujata Massey's Blog, page 7

August 15, 2022

A Showdown of Peaches

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

I consider myself tolerant of heat. Yet over the last few days, I’ll admit that the air in Baltimore, Maryland, has felt like a poison gas sauna. And it’s not just me. Even Daisy, my energetic Yorkshire terrier, refuses to take a walk.

At the same time, the early mornings of late are wonderful—warm without being oppressive, and somewhat shady in our neighborhood. I try to get to the farmers market on the weekend and have been rewarded with gorgeous produce that’s not available other times of the year. I’m getting purslane to use in salads. Tiny sweet plums, for devouring in two bites. Melons that taste like the sweetest perfume, and fragrant boughs of basil. Every color of tomato, and what I wait for each year: white and golden peaches.

Because I’m I in an end stage of editing (Perveen Mistry Book 4 almost turned in), I decided to celebrate with a relaxing hands-on activity that was far from my keyboard. I’d been thinking about a paleo peach cake recipe that my sister emailed me. Also, I’d noticed an old recipe for something called Baltimore Peach Cake was doing laps on the Internet. I thought, why not throw caution to the wind and just bake them both? Yes, on the same day. It would be a showdown of two different styles of cake.

My bet was in favor of the more historic recipe, Baltimore peach cake. I first tasted it during my early years in the city, when I’d spot $3 pieces of this bargain cake wrapped as a to-go item on the counters of casual cafes and bakeries—but only in mid- to late summer. I didn’t know then that “Baltimore Peach Cake” was an actual recipe for a simple yeast-dough cake topped with sliced peaches. And everyone in the city knew it, just as they know about sauerkraut being an important Thanksgiving dish.

The most-shared published recipe for this dessert originates with an alternative newspaper, The Baltimore City Paper, which I freelanced for toward the end of college. I didn’t come across the recipe, then, though. And truly, it goes back to Baltimore’s German community. I take this as gospel because I’ve had the fraternal twin to this cake, a yeast dough topped with plums, made by my own German mother. My mom’s pflaumenkuchen was rather sour because we were limited to California prune-plums that shipped to Minnesota; there were no plum trees in the state. Pflaumenkuchen was served with a bowl of sugar next to it, so the eater could ladle the sweeteners it sorely needed on top. I did enjoy plum cake, but it was strictly a connoisseur’s dessert.

So how did a German cake get labeled a Baltimore cake? The answer is immigration. Germans began settling in the area of the Chesapeake that became the city of Baltimore since the early 1700s. The largest waves of Germans came during the 19th century, when the Port of Baltimore was the second largest entry point for immigrants to the United States. Sections of West Baltimore were built up with elegant townhouses into a prime residential district for wealthy German Jews, civic leaders who founded long-gone department stores like Hutzler’s and the Hecht Company. Neighborhoods like Highlandtown, Federal Hill and Locust Point were full of German-descended Baltimoreans of all income levels and the Lutheran and Catholic religions. It’s easy to imagine the sound of German being spoken by neighbors sitting out on their marble rowhouse steps (we call them “stoops”) in hot summer evenings. And Mutti (or Mutti’s granddaughter) arriving with a piece of peach cake on a napkin for a friend stopping by to catch the breeze.

I believe it’s the typically hot summers in our Mid-Atlantic area that make our peaches so juicy and sweet—and also the warm temperatures in July and August that make baking this cake possible. After all, it’s a yeast dough. Once that’s coddled and stretched into a pan, you top it with straight lines of peach slices. It’s that simple. However, the time to prep and bake was about three hours for me. Not a quickie, by any means.

The second recipe on my agenda was a gluten- and refined sugar-free cake recipe from food writer Michelle Tam, whose website Nom Nom Paleo is wildly popular with people eating modified diets. The so-called “paleo diet” is not necessarily low in calories. The eating style gets its name from the word “paleolithic,” and involves meats, vegetables and some fats, and avoids beans, milk, sugar and white flour. So this paleo peach cake recipe calls for maple sugar (although I found that maple sugar is actually VERY sweet). The cake’s batter contained both almond flour, a favorite of mine, and cassava flour, which I had never tried before. I was feeling slightly daring to try it, because I’d heard the tuber plant from South America, Africa and Asia is mildly poisonous if you eat it raw. However, if the cassava plant is dried and ground, the poison isn’t there anymore, and it becomes a highly nutritious flour. The recipe’s other ingredients ranged from the ordinary—butter, vanilla, eggs, vanilla extract and baking soda—to the more unusual: ground cardamom and canned coconut milk. I am a fanatic for cardamom and had some single-origin cardamom pods from Kerala that I was eager to pulverize for the sake of this cake.

Baking takes time, so I started my day of desserts by baking the Baltimore peach cake, because it was a yeast dough. I rarely do anything with yeast, and although the packet I opened was not yet expired, the granules within refused to foam up when added to warm water. I had to microwave it 15 seconds to get any action. Furthermore, the dough refused to rise, and I had a sneaking suspicion it was because my air conditioning was too powerful. In the end, I took the bowl outside, put a plate on top to keep out the bugs, and let it rise in the good old Baltimore 90-plus degree morning.

The exposure therapy worked! After an hour, I thought the dough had grown slightly. I was able to easily stretch the dough to fit a 9×13-inch pan. Baltimore peach cake recipes aren’t usually specific about whether you need to peel the peaches. However, the paleo peach cake recipe called for getting the skins off, so I did take the skins off all the peaches by dipping them for a minute in boiling water. How pretty and promising the Baltimore peach cake looked once the peaches were laid in place!

This second recipe, for the Paleo peach cake, called for a round pan. The recipe’s author, Michelle Tam, included tips like practicing a layout of peaches on a plate before doing the real thing, and cutting out parchment liner for the pan that makes complete sense for lifting out a completed cake. Also, I only had to deal with cake batter in this recipe—not yeast-based dough. I was pleased that this cake took less than two hours, start to finish.

Even six hours after baking, my kitchen was filled with the scent of fruit and sugar. I tried both cakes warm, a few minutes out of the oven. And what a surprise—I lost my earlier bet with myself. I found the Paleo cake more moist, flavorful, and worthy of gorging. The cardamom and almond flour were fantastic. However, the Baltimore peach cake contained less sugar per square inch than the Paleo one, which makes it a great dessert for people who are avoiding super sweet foods. And a pretty decent snack to take in the car, or to have with morning coffee.

I sampled each cake right after they were baked. In the evening, I had another sliver with ice cream. The fury of heat had been swept off in a massive rainstorm. It was refreshing to go out with my cake and sit on the porch, savoring memories of past Baltimore summers, and knowing I’d spent one of the summer’s worst days like an old-time Baltimore lady.

My revised Baltimore Peach Cake Recipe (inspired by the Baltimore City Paper)

Makes at least 12 servings

¼ cup of warm water (no more than 110 degrees)

1 individual package of active dry yeast

1 cup of milk, scalded

¼ to ½ cup of sugar, depending on your taste

1 teaspoon fine salt

¼ cup of melted unsalted butter

1 egg, lightly beaten

3 cups of flour

1 teaspoon of crushed cardamom seeds taken from pods, or powdered cardamom spice

Vegetable oil for greasing bowl

4 ripe peaches, briefly immersed in boiling water to peel off the skins

4 tablespoons of peach or apricot preserves or orange marmalade for glaze (optional)

I only made one modification (a marmalade glaze) to the gluten and refined sugar-free dessert described by me as a paleo peach cake. Therefore, I’m sharing the original recipe from the Nom Nom Paleo site. Technically, it’s called Fresh Peach Cake and was created by Michelle Tam.

The post A Showdown of Peaches appeared first on Sujata Massey.

July 13, 2022

A Writing Room in Paradise

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

What makes a perfect writing room? Or better yet—an ideal writer’s house?

Because I love rooms almost as much as books, this is a question I’ve pondered for years. In my childhood in Minnesota, and during college in Baltimore, I could think of nowhere better to write than sitting up in bed with the door closed: so quiet, cozy and private.

As years passed, I found that a desk was a better place to stay focused and not drift off into a nap. I wrote happily in a series of study rooms in my homes—apartment to house—until I felt too distracted by all the notes, extra manuscript pages, and books that were rising in columns on either side of my computer. Unable to concentrate, I decide to write outside the home, where the only personal property I carried was my laptop.

This shift led to some fruitful coffeeshop writing years, followed by about a year of regularly working at a table or carrel at the Johns Hopkins University library, where I enjoyed the surreal experience of being creative in a familiar environment where I’d once spent hours taking longhand notes or drafting essays. I had to stop writing in the library during the pandemic, when it was closed to all but those enrolled or working at the University. The decision made sense, and I decided to look at writing at home in a new light. After all, I was based in the largest house I’d ever lived in and no longer had small kids running around making noise. I had my own study at the top of the house, and when that got messy, I could set up in the dining room. Or how about the sunroom, so heartening in winter? In summer, I had three porches to consider.

I’ve grown back into writing at home, and I also harbor a passion for seeing other writers’ homes, whether they are dear friends inviting me for a cup of tea, or museum-owned spaces that nurtured authors I only know through books and reputation.

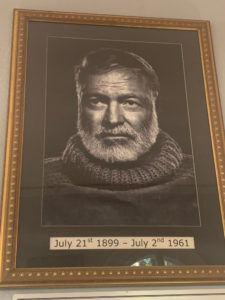

On a recent trip to Florida, I visited a writer’s home that runs on the order of truly magnificent: the 1851 French colonial house in Key West’s historic district that was the residence of Ernest Hemingway from 1931-1939, when he was in the midst of his second of four marriages. The house, and the installation of its grand swimming pool, Key West’s first, were paid for by Hemingway’s wealthy wife Pauline Pfeiffer Hemingway—although Hemingway erroneously complained that she was spending every penny that he earned. Some nerve, huh? Especially because Pauline had worked as a decorator, and for Vogue, and put her stamp on the house in many ways, including the elegant chandeliers and boldly tiled bathrooms. The house’s many long shutters are an amazing yellow color. Was it her choice?

Here’s a photograph of what the Ernest Hemingway Home and Museum looked like during the Hemingway family’s time in the 1930s:

And the museum grounds are truly lush and lovely, which is par for the course in a town that feels like paradise.

Hemingway installed a writing study on the upper floor of a cottage that connected to the main house by a catwalk. The catwalk no longer exists; but speaking of cats, they are as ubiquitous and more plentiful than the vintage typewriters in most rooms.

Ernest reportedly longed for one of the polydacytl cats popular on sailing ships because they were believed to be good mousers and also bearers of good luck. A captain friend gave him a pure white cat with six toes per front paw. This cat was named Snow White by his sons and became the ancestor of approximately seventy cats living on the property today, some of whom carry the same genetic trait. Most of the cats have been spayed, but not all of them, because the historic foundation running the house as a museum knows what a draw they continue to be. If you mention that you’re going to Hemingway’s House, the person who hears you will likely say, Oh! The place with dozens of feral cats!

Hemingway House cats are allowed free reign to all rooms and furniture. The house has no litter boxes, and the guide explained that the staff picks up after cats all day and night. A doctor visits weekly to check the health of the cats. I always imagined a house with dozens of cats would feel overrun; but these cats enjoy spending time alone, often just one to a room or hallway. They take after writers with this habit.

Most of the original furniture from Ernest’s time is gone, but the writing study is furnished as a stylish masculine adventurer writer’s room. Mission furniture, animal furs, and earth tones abound. Was this Pauline’s work, or someone else’s? I found the study attractive but doubted that every single piece dated from the thirties. The condition was simply too good, and the quality so tasteful. Yes, there were old books in the cases, but Hemingway’s writing study looked more like an idealized reception room to me.

And while the air-conditioning hummed on the day I visited, I know that it couldn’t have been running in Hemingway’s time. My guess is that the writer probably took a long siesta from April to September, spending time on his many leisure pursuits in more comfortable climates, or on the seas between the Keys and Cuba.

The post A Writing Room in Paradise appeared first on Sujata Massey.

June 29, 2022

The “Wife’s Help”: Writing about abortion in historical fiction

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

About two years ago, I started work on a new book in the Perveen Mistry historical mystery series. The beginning is a lot of fun. Searching for historical events and themes to explore is typically a magical period of big dreaming. To coax out story ideas, I reach into the messy purse that is my brain, the spot where memories and idea fragments coexist like torn candy wrappers and soiled pennies.

What I pulled out of the bag was the notion of reproductive rights. It didn’t take long for me to realize I could become passionate about writing a story that illuminated these health and freedom challenges faced by women in 1920s India. How would their choices be different than a modern woman’s? Especially if laws existed to punish those who tried not to bear children, either through contraception or abortion?

In the vintage photograph above, women of the Kurni (tilling) caste pose together for a colonial photographer. How many of the women are mothers, and how many children do this group collectively have? Surely some of them are mothers and daughters. And I wonder–do the small girls flanking the ends of the group already have husbands?

I believe that abortion is an understandable part of reproductive life—just like menstruation, childbirth and contraception and venereal disease. I haven’t shied away from writing about these aspects of women’s lives in my feminist mystery series set in 1920s Bombay. Therefore, the fourth novel in the series became the perfect entry point for my lawyer heroine, Perveen Mistry, to assist an illiterate ayah charged with the crime of abortion. Slated for publication in June 2023, tThe Mistress of Bhatia House also includes scenes with Perveen secretly reading a banned book about contraception, and deliberating over whether she should assist a contentious group of women volunteers trying to establish a maternity hospital.

Abortion law in India was created along with the arrival of the British. In the early East India Company times, criminal courts administered by British officers were set up; however, prosecutions of abortion were rare. A chief reason was that life was defined as starting at quickening: the time in pregnancy, somewhere between the fourth and fifth month, that a baby’s movements can be felt. Colonial government had greater concern about criminal prosecutions of people committing infanticide on young babies, the burning of widows, and other “easy to see” crimes. This laissez faire attitude toward abortion matched the mood of judges in Britain and the United States during the same time period, who all regarded quickening as the start of human life.

For most of India’s history, the midwife (called a dai) was the one who performed gynecological care in humble villages and bustling towns. A woman who missed a period would go to the local dai to request a herbal tea known to lead to cramping and the onset of menses. Many women regularly drank such teas, which were even nicknamed “Wife’s Help.” Women were taught that a husband’s desire had to be obeyed, even if the outcome meant too many children to care for, or physical damage to a woman’s body from unending pregnancies and deliveries. Mitra Sharif, a University of Wisconsin professor of law and an authority on the history of law in colonial India, dives deep into the medico-legal history of abortion in a lengthy, fascinating article that appeared in Modern Asian Studies.

As Dr. Sharafi learned from researching hundreds of legal documents, newspaper articles, and books, on occasion the medicinal teas were unexpectedly poisonous, causing great suffering or even death. And sometimes, dais used sticks or other crude means to disrupt a pregnancy. Varied poisons including gunpowder and arsenic were sometimes administered to pregnant women by uneducated family members—with death as a consequence. And it wasn’t only Indian women who sought to end pregnancies. British colonial women also had the same need, and when one such wife died following an illegal procedure performed by a medical doctor in the colonial system, the case went to court.

Rajasthani women in British Colonial India

Rajasthani women in British Colonial IndiaIn the second half of the nineteenth century, the British took formal control over half the subcontinent. This meant that by 1860, the Indian Penal Code was created, and it included a revised definition of the criminality of abortion (as well as homosexuality, but that’s a long story for another day).

Under the Indian Penal Code, quickening was no longer the defining factor in a baby’s viability. An attempt to end a pregnancy at any stage was considered abortion, and midwives in India were now at risk of being prosecuted as abortionists. The stress was on convicting the “perpetrators” of abortion rather than “victims”; in fact, the law was presented as protecting India’s women. In Britain and the United States, abortion was also redefined after 1860 as a more serious crime that could be prosecuted in cases where a pregnancy was terminated earlier than the fourth month.

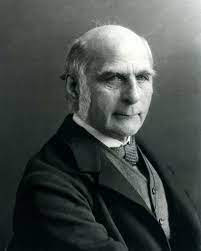

[image error]N.S. PhadkeWhy did these countries have a sudden interest in outlawing abortion?

One idea floating around elite people were becoming interested in eugenics, a pseudo-scientific theory about the genetic superiority and inferiority of various races. In the US, doctors in the all-white American Medical Association advocated for the birth of more White children to form a protective block against what was perceived as a surge of immigrant and Black births—and abortion laws meant reducing numbers of Black midwives. The notion of sterilizing members of unsavory social classes in Britain was seriously considered by government officials.

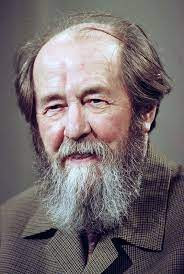

In 1920s Bombay, philosophy professor N.S. Phadke lectured and wrote about some modern contraceptive methods of Europe, such as the diaphragm, arguing that bringing contraception to India would decrease the number of poor people bearing children at young ages and allow for the dominance of wealthy, higher caste people to reproduce (and successfully gain India’s freedom!). His 1927 reproductive education book, Sex Problem in India, has an introduction by Margaret Sanger. I ordered a replica edition to be made in India from a digital scan. After reading Phadke’s provocative commentary, I decided to get it into Perveen’s hands.

Francis Galton, definer of Eugenics

Francis Galton, definer of EugenicsEugenics were about contraception and keeping birth rates down. Abortion laws in India served an adjacent purpose by making it more difficult for dais to practice. Also, the prohibition of abortion also made it a weapon for people to use against each other. For example, unscrupulous in-laws wishing to expel a widow from their home could report to the police shed had an abortion. Such immorality would disqualify her from continued support, and if she had any assets left by her late husband, the family could seize them. Other villains using abortion as a weapon were constables shaking down women’s families for bribes in exchange for not accusing them. Enough corrupt cases came to court that laws were passed making it a crime to falsely accuse someone of abortion.

But accusations are real, and they are dangerous. Right now, there’s an abortion vigilante law in Texas that offers cash bounties to anyone assisting the police with information leading to the arrest of a woman obtaining an abortion; not just in-state, where it’s illegal, but out of state as well.

The Texas nightmare arose two years after I started The Mistress of Bhatia House. However, I felt increasingly worried for women after Donald Trump was elected in 2016 with the support of many people wishing to outlaw abortion. In the past six years, many states passed laws that made it more difficult for women to obtain abortions in their states, and also for doctors and nurse practitioners to perform abortions. Thirteen states passed “trigger laws” to ban abortions entirely within 30 days of a Supreme Court decision overturning 1973’s Roe versus Wade decision establishing abortion as a constitutional right. The Supreme Court’s new appointees, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, refused to admit that they would vote to take away the right to abortion.

But last week, that’s what they did.

The post The “Wife’s Help”: Writing about abortion in historical fiction appeared first on Sujata Massey.

June 15, 2022

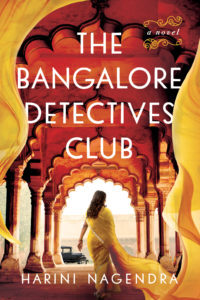

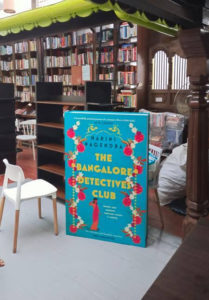

An Invitation to The Bangalore Detectives Club

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

US edition

US editionThis week, I request the pleasure of your company for tea and conversation at The Bangalore Detectives Club. This ‘club’ is a gathering of sleuths who populate Harini Nagendra‘s dynamic historical mystery set in 1920s India. If you fancy the idea of tracking a murder mystery through a colonial city of “bungalows and banyan trees, lakes and monkeys,” your membership application is already approved—trust me, you will love this book. Harini was born and raised in Bengalaru (the post-colonial name for Bangalore) and was generous to give me her insights in the place, character, and history. Pour yourself a cup of tea and listen in.

Author Harini Nagendra

Author Harini NagendraHarini, I was privileged to spend a month in Bangalore in ‘old-ish’ days—the early 1970s, when I recall quiet streets shaded by lush trees and walks in fields with tall grasses. My sisters and I got to swim at a private social club that could have been the inspiration for the Century Club. Is there such a club that you researched—can you tell us its name?

Bangalore of the 1970s was such a gorgeous city, isn’t it—with its tree-lined avenues, and open grasslands dotted with the odd large boulder, alongside lakes! The Century Club, where some of the opening events take place in the book, is a real place. My father was a member, and so was I for some years. We visited the club often, and I have woven some of the descriptions of the settings there from older memories. The history of the club which I present in the book is a true history. It was a place created by the influential Indian bureaucrat and merchant community so that they could have a space of their own to socialize, away from the other European-only clubs that excluded them.

The Century Club

The Century Club

I’ve heard you say that your protagonist Kaveri dropped into your life—she presented herself, and you tried a couple of ways of telling her story: first pre-marriage, and then married.

Sometime in 2007, I was in my mother’s home, reading up on some archival material on Bangalore for my academic research, when a young, spunky woman spoke up, made herself known and demanded I write a book about her. Being the fan of historical mysteries that I am, it seemed natural that I would write a mystery book.

Kaveri was initially not married. She was about the same age I have her at now—19 years—and I planned for her to meet her husband Ramu (they both had different names at the start) when he came to her home to give her tuitions in science and maths. But as I continued my research I realized it was highly improbable to have her be as old as 19 and yet unmarried at that time. Many young girls were married much earlier—by 12, or even sooner.

I changed things around, giving her the back-story of having been married at 16. In my mind, she was very much a young woman at the cusp of beginning adult life though, and I couldn’t have written her in that way if she had been married for three years—perhaps with a few kids—at the start of my book. Nor could I have begun a book written today, for contemporary readers, with an amateur detective who was 16. So I added another thread—while Kaveri and Ramu were married at 16, as many households did at that time, the marriage was a formality for some years. She continued to live in her parents’ home until she was 19, completing her studies as Ramu focused on his work. She then moves to Bangalore a short while before the book, starting life in another city, as a new wife, and with a fresh ‘career’ to develop as an amateur detective.

Kaveri’s in a situation with a loving, tolerant young husband, and his parents are holding power over both of them. Why did you choose this set-up, which actually gives her less freedom than if she were still unmarried? How does it intensify your messages about female empowerment and and also the mystery?

I heard my grandmother often say that women’s lives were a matter of luck. A young girl could be born in the most privileged of homes, and raised with the greatest of love and care by her parents—but if she then went into a home where she was treated badly, for the most part, her life was going to be blighted, and there was nothing much her parents could do to help her. Unfortunately this is still true of many women’s lives today, not only in India, but in many parts of the world. But the converse is also true. I know many strong women in my own family, and that of my husband, who flourished and made a strong impact in their own chosen areas, when in loving relationships with supportive husbands. For instance my mother’s grandmother, a home-maker married to a progressive bureaucrat in the late 20th century, was also an excellent herbal doctor and mid-wife.

Also, when Kaveri landed in my mind, she was always paired with Ramu—so marriage was a natural setting for me to choose. To help her sleuth in more freedom, I had to shunt her mother-in-law out of the way for much of the first book, of course. In terms of solving mysteries, pairing Ramu and Kaveri helps—while Ramu investigates the lives of men in the hospital, Kaveri talks to the women, and gets a very different perspective on events. And in doing so, she gets to explore how women in different strata of society lived, and were treated—thus helping the reader understand what an abstract concept like feminism might have meant to many different kinds of women in 20th century colonial India.

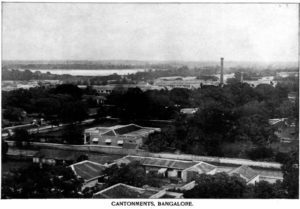

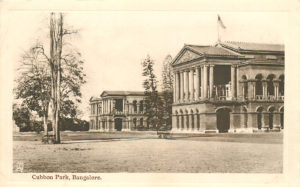

Historic View of Cubbons Park

Historic View of Cubbons ParkOne of the ways Kaveri snoops at the bi-cultural, elite Century Club is by telling the manager she’s come to ‘take a cutting’ of some plants. Tell us about your background in ecology and how that shows up this novels settings?

I have a PhD in ecology, and have been working on ecological research for 30 years now. Bangalore is one of my core focus areas, and my 2016 book Nature in the City: Bengaluru in the Past, Present and Future describes the ecological history of the city from about the 5th century CE to current times. This is a long, roundabout way of saying that I am deeply in love with, and perhaps even a little obsessive about, Bangalore’s ecology! The setting of the story, in Bangalore—city of bungalows and banyan trees, lakes and monkeys—was a very important part of my story. Through descriptions of the ecology of both parts of the city—the British colonial areas with their majestic rain trees and monkey-top buildings, and the Indian areas with their posh cottages and tiny mud lanes, with cows, monkeys and coconut trees—I hope to bring the contrast between the colonial occupiers and the native Indian residents into sharper focus. I also use ecology in places to heighten the tension, such as when a kite makes its mournful keening call while swooping down to grab a rat in its sharp talons, or when an owl, believed to be a harbinger of bad luck, hoots at night.

Writing about India under British rule is a balancing act. Rama Murthy keeps his interest in independence rather private because he’s being paid by the British government. Also, his boss, Dr. Roberts, does not fit the mold of how British colonial officers are portrayed. How do you look at colonialism and in what ways does this institution play into the mystery?

Colonialism is a background theme that has a dominant influence on the plot, setting, and characters: on every aspect of the novel indeed. It is a balancing act, and I love how you portray the collision of cultures in your Perveen Mistry series. Bangalore in the 1920s is not directly under the British rule but part of a princely state, governed by the Mysore king who is himself subject to British diktats and whims. As such the movement for Indian independence is somewhat more muted in Bangalore than it was around the same time in Calcutta or Bombay—but still strongly present, just a bit more in the shadows. There were some progressive British residents, just as there were regressive Indians—but overall, as a system, the power and control vested with the colonizers of course. Over the course of the series, as more time passes, I hope to show how the anti-colonial movement gained strength in Bangalore, and how Ramu and Kaveri’s own trajectories of growth intersect with and are shaped by these broader historical forces of change.

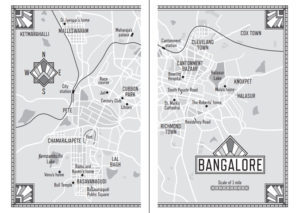

Map inside the book!

Map inside the book!Your research is impressive, from the look into the communities of cowherds, the history of prostitution, as well as the reality of one of the few mental sanatoriums in India being in Madras. Tell us how you found the documents and other materials to help with this work. My favorite source of information is an old map of Bombay with the landmarks drawn right on it that I got from a UK seller on eBay. Do you have a favorite historic material about Bangalore that was useful?

Thank you! Since so much of my day job as an academic involves research on old Bangalore, I have masses of material to draw on, including gazette records, annual administrative reports, ledgers files that record obscure bureaucratic battles over lakes and cemeteries, and other fact-laden material. As a fiction writer, I needed to flesh this out to make the dry and dusty facts come alive. For this I used old maps and photographs, diaries and letters, biographies, and old stories told by people in my own family, as well as those of others whom I spoke to—including cowherds, fishermen and fodder collectors, and others who provided a glimpse into the parts of the city which are always left out of the archives. Maps were my favorite source of material too, though—I have a number of old maps of the city, but the one I love best is an 1880s map in the Mythic Society of India’s library, that is detailed enough to show the location of individual graves in European cemeteries!

I was excited to hear you mention in an interview some female family members in past decades who did brave things, like actually swimming in a sari. I also was impressed by the realistic detail you share about the rules surrounding a young Brahmin wife living in a traditional upper class family. What are some of the small rebellions you chose for Kaveri, and what are the ways that she stays in line?

The opening scene, where Kaveri goes swimming in a traditional nine-yard cotton sari, is indeed inspired by my husband’s aunt, whom I admire tremendously. Now 96 years old, she went swimming in a sari when she was a young girl, in 1930s Madras (now Chennai). Women in upper class families were fenced in by societal expectations and restrictions that dictated what they could and couldn’t do—to transgress some of these boundaries was to invite shame on the entire family, as you also describe so vividly in your books on Bombay. Sometimes women were the worst enforcers of these expectations, but at other times they helped other women find ways to circumvent these forced obligations, often in secret.

It is in the smallest of ways that rebellions often begin—a testing of the waters, so to speak. Kaveri longs to eat mushrooms, which, though vegetarian, are forbidden to her because of caste restrictions. She asks her maid Rajamma, who is also a confidante, to bring her mushroom curry, and eats it in the back of her home, hiding under a tree to escape her mother-in-law Bhargavi’s notice. She studies mathematics in secret at home for the same reason, because Bhargavi believes that too much studying makes a woman’s brains go soft—until she gets Ramu’s support, at which point she begins to teach other women like her elderly neighbour Uma aunty to read and write as well, expanding the opportunities that older women had to access books and reading material.

On the other hand, she does have to tread carefully not to lose the support of her husband. When she meets and befriends a vulnerable prostitute in danger, Ramu is furious with her, and forbids her from offering further help. But Kaveri doesn’t take no for an answer easily. Open defiance is not in her character. Instead, she works on Ramu, plotting in secret to bring him to her side.

The title “Detectives Club” makes me think of a group working together—aka a police unit, or even the Famous Five. Why use this term, and which characters do you see as being part of Kaveri’s mystery-solving in this book and others to come?

The collective strength of women has always been deeply fascinating for me. One strand of my research started in collaboration with the Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom focuses on how community collectives work together to conserve forests, lakes and other natural resources across the world. In The Bangalore Detectives Club series, I hope to show how women can come together to lift each other up, combat crime, and change society for the better.

I also love The Famous Five! I read and re-read every one of the series when I was young, and again when I introduced my daughter to them several years back. I think of Kaveri and Ramu’s crime-solving journey very much as a Heroine’s Tale, in the Famous Five mould, rather than a classic Hero’s tale. That is, it is a tale of collaboration and cooperation, rather than chronicling the lonely adventures of a single intrepid investigator. Kaveri and Ramu, Uma aunty and Inspector Ismail are the initial members of The Bangalore Detectives Club. Over time, as book two will show, the club expands to include some of the other characters from Book 1 such as Mrs. Reddy and Mala, as well as new characters that we meet along the way.

What’s the hardest thing about writing book 2—or is it coming as easily as The Bangalore Detectives Club?

I took 13-14 years to write book 1—because I didn’t have a deadline, and also because I was figuring out how to plot and write a full-length mystery novel and had to rewrite it and change the plot at least three times. With Book 2, I was on a very tight deadline. I do my best work when I am motivated by deadlines. That comes from sheer force of habit, a consequence of writing academic papers and popular non-fiction for 30 years.

But I also had the advantage of knowing a few things about my own process of writing: for instance, how to plot, what voice I should write in (I spent many months during the first book switching between first to third-person and back again). And of course I knew my main characters very well by then!

Book 2 is with my publisher, who is editing it as we speak. I found the start very intimidating. I opened my computer and then thought of the fact that I was attempting to write an entire book from scratch, and that seemed very foolhardy. But once I shut off that part of my brain and started typing out the opening scene, it flowed easily from there. Of course I still had to go back and edit the plot and text many times, but I knew that I would be able to get to the end eventually, because I had gotten to that end once before. Does that make sense? Of course I have no idea how Book 3 is going to be—this is a process of endless learning, and I’m sure there will be many obstacles along the way to navigate. I love being transported to a different place and time though, and absolutely enjoy the process of actually writing. Editing is hard for me though. I tend to get more impatient than I should, and I am learning to gradually put that impatience behind me.

Did the editors in your different countries (USA, India, and UK) ask you to change any particular thing to suit their audience (aside from spellings, of course)? I mean, did you have to provide cultural context for some publishers, or cut it back for others? Do you have any other foreign publication deals?

My UK editor, from Little Brown’s Constable Crime series, acquired world rights for my book, and the India version is published by Hachette India, which is part of the same group—so they used the same text. The US rights were purchased by Pegasus Books. Interestingly, they used the same proofed manuscript as the UK one, with the UK spellings! The UK publishers did ask me to provide a greater cultural context to explain some aspects, such as why Kaveri is vegetarian (because she is born into a specific community and caste which is vegetarian), or to explain unfamiliar words like lathi (bamboo stick), and provide a glossary. They also asked me to cut back in some places, such as when I got carried away with providing detailed botanical descriptions! But overall, they let me retain the cultural flavor of the book. I don’t have any other foreign publication deals at this point, but would love to, if there are international publishers out there reading this…

What’s the ecology field work you are about to undertake?

My husband and I have started to collaborate on some new research involving the Krishnarajasagara Dam in Mysore, which was built in 1910, and was one of the largest dams in the world at that time. Because of the pandemic, we have spent the past two years digging into archival material, and leaving the field work for later. We plan to spend the next few months making multiple trips to the dam, an associated hydro-electric station. and the agricultural landscape around the dam, including a power station. The Mysore kings were very keen on modernization, and Bangalore was the first city to be electrified in Asia in 1905. The dam, electricity, and the spread of sugarcane cultivation after the dam had a major impact on the region, its economics, ecology and politics which are visible even today, some 110 years later. We’re really looking forward to the field work; it’s been way too long since we got out of the city.

Krishnarajasagara Dam

Krishnarajasagara DamWhen can we next read a Kaveri Murthy book, and can you give a hint to the topic?

Book 2 in the series is titled Murder Under A Red Moon, where Kaveri stumbles across a murder during the darkly inauspicious time of an eclipse. Bhargavi, Kaveri’s fractious mother-in-law whom I conveniently sent away through much of Book 1, is back in Book 2. Will the two women mend their relationship, or will it get even worse? The background themes of feminism are even stronger in this book, which explores the rise of the women’s suffrage movement in 1920s Bangalore—and of course, the rumblings of discontent against the British colonizers continue to grow in intensity. Murder Under A Red Moon will be out in March 2023, and will have more delicious recipes at the back as well.

Reading through this interview, I learned so much about nature, the path toward women’s liberation in India, as well as the writing process. What a joy that Harini Nagendra has entered the mystery world and can enrich of all of us with her work!

The post An Invitation to The Bangalore Detectives Club appeared first on Sujata Massey.

June 1, 2022

The Latest Anglo-Indian Romance

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

As a teenager, I loved to read bodice rippers. That passion faded. I explain it this way: I grew up to be a mystery writer. Romance novels don’t hold my interest because the outcome rarely varies from my guess on Page 20.

I’m sure I sounded like a sourpuss when I declined my friend’s advice to watch a popular Netflix Original series titled “Bridgerton.” Executive Producer Shonda Rhimes’ show is based on the Bridgerton romance novels written by Julia Quinn. Quinn is a Harvard-educated writer who is a career romance novelist. In an interview with Collider, Quinn said she was not in the writers’ room for the show and considers herself just like the other fans when she reacts to the program.

Eventually, curiosity overcame my resistance. Especially because I knew there would be South Asian actors playing big roles in Season 2. One quiet evening, I made tea, donned my pajamas, and logged into Netflix.

Reader, I found myself captivated. Picture a London where Black, White and Brown elites dance, play sports, and dine together under the watchful eyes of (mostly widowed) society mammas. Men are the arm candy, and women the deciders, in this re-imagined world.

Lady Mary Sheffield Sharma is a British-born lady of middle years whose mother is Anglo-Indian married to a White British Lord. We learn from gossiping members of the ‘ton’ that over twenty years earlier, Lady Mary fell in love with an Indian man with unsuitable lineage who worked as a clerk. She left Britain married to Mr. Sharma and in India, and happily raised his daughter Kathani (called Kate) from his previous marriage to a wife who’d passed away. She also gave birth to a second girl, the petite Edwina. Things were good. Mr. Sharma clerked for a maharaja, and the girls grew up with palace manners, many languages, and lessons in music, dance, and hunting. The actors playing these characters are Shelley Conn (Lady Mary), Simone Ashley (Kate Sharma) and Charitha Chandan (Edwina).

After Mr. Sharma’s premature death, Lady Mary sells all she possesses for sea tickets to England so she can take the daughters to London for the season. Her step-daughter Kate refrains from putting herself forward as a candidate, because she’s fully committed to screening every man who shows interest in Edwina for social standing, kindness, and reputation. As Edwina’s romance takes off with the handsome young Viscount Anthony Bridgerton, Kate finds herself skeptical of his motives.

Colonial official visiting an Indian court

Colonial official visiting an Indian courtBridgerton’s female-dominated marriage-brokering with an insistence on respect and love reflect 2022 values. However, the background story about Indians coming to Britain to marry actually holds truth. Starting in the 1600s, Britain’s East India Company sent ships filled with unoccupied young men to India, relative latecomers to the game of colonialism. They were following the pattern set by Portugal, Dutch, French, and Danish-Norwegian trading companies. These countries vied for the chance to claim ownership of land, and then profit from the agricultural and mineral riches.

Naturally, many of the bachelor employees paired up with local women: sometimes living with them, sometimes marrying them, and quite often fathering children. The slang phrase “Sleeping Dictionary” was sometimes used to joke about the ways these lovers taught language and cultural literacy to the colonists.

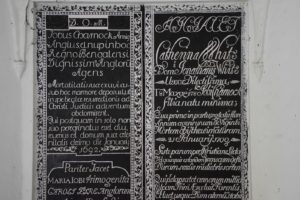

Charnock’s mausoleum includes Maria’s name

Charnock’s mausoleum includes Maria’s nameIn 1657, Job Charnock was a young East India Company administrator who’d been promoted to a position as the Factor (trader) for Patna, a town in Bihar. Legend says that Charnock went on a day trip because he wanted to witness the act of suttee: the immolation of a widow on her husband’s funeral pyre. This misogynistic rite was practiced in some regions, particularly with elite Hindu families. Rather grisly sight-seeing; but then again, hangings and floggings were a public spectacle throughout Europe.

When Charnock caught sight of a young, beautiful woman going toward her death, he made a snap decision to rescue her. Renamed Maria, Leela was brought into Charnock’s world—where he rose to great heights in the East India Company and was credited for making the deal to get three villages that became Calcutta. Job and Maria may have had four children; some accounts say they were married. Bharti Kirchner’s novel, Goddess of Fire, uses history to imagine the romance within Job and Maria’s story.

Khair-un-Nisa

Khair-un-NisaMore truth about East India Company men can be found in White Mughals by William Dalrymple. This is a deeply researched nonfiction work about the surprising number of British men who fell for Indian women and also preferred to live a luxurious Indian lifestyle. The book’s central story is of James Achilles Kirkpatrick, a British Resident in Hyderabad, who fell in love with Khair un-Nisa, a high-born Muslim lady. He married her and became part of the palace family, perhaps even working as a double agent for the palace against the East India Company. After Kirkpatrick’s early death, his two children were taken to England to live with their grandparents and denied further contact with their mother in India. They were baptized as Christians and given the English names of William and Catherine (or Kitty).

The Kirkpatrick children, while still in India

The Kirkpatrick children, while still in IndiaFrom the middle of the 19th century and beyond, Indian landowners and royals could extrapolate that the entire subcontinent was at risk of domination. Some maharajas tried to refuse the pressure to sell or gift land demanded by the East India Company’s officials. Often, a refusal to capitulate led to war, with the East India Company Army often, but not always, seizing land as their trophy.

When resistance to the East India Company’s actions became significant, Queen Victoria’s government formalized rule, sending to India a Viceroy who served in a prime minister-type role, with governors overseeing the various states, and political officers keeping a close eye on Indian royals who’d agreed to cooperate with Britain, in exchange for being allowed continued autonomy.

Now, Indian-British marriages were considered unacceptable, and people suspected of having Indian blood were often excluded from British-only hotels and social clubs. Unmarried White women from Britain sailed from India to marry the single British men working in India, and thus English families began to populate the landscape.

Yet Indians still sailed for England and Europe. A major draw was the chance for an elite education; a lesser-known reason was the loss of homeland.

Princess Victoria Gouramma

Princess Victoria GourammaConsider Princess Victoria Gouramma, who was born in 1840. Princess Gouramma’s father, the Maharaja of Coorg, fought unsuccessfully to preserve his South Indian kingdom. The East India Company won, annexing his kingdom to British India and making him a political prisoner. He eventually was released and applied for the right to take his eleven-year-old daughter for Christian schooling in England. The Maharaja’s true mission was to file a lawsuit against the East India Company for taking his kingdom by illegal means. Queen Victoria of England became Gouramma’s godmother and invited the child to live with the other royal children at Buckingham Palace. Gouramma was christened Victoria by the Archbishop of Canterbury. At 19, Gouramma married a 50-year-old British army colonel who absconded with her money and jewels by the time she was 23. She died shortly afterward of tuberculosis.

Queen Victoria also was charmed by Prince Duleep Singh, who, as a child maharaja, was coerced to give up his right to rule Punjab. Prince Duleep was separated from his Indian mother, Maharani Jind Kaur, who’d been Punjab’s regent since Duleep’s father’s death. Duleep was brought to England at the age of fifteen, where he was raised by a British official and his wife, educated and given a huge allowance. Queen Victoria also invited Duleep to stay with her, and she tried to arrange a marriage between Prince Duleep and Princess Gouramma. However, Duleep married Bamba Muller, a penniless but beautiful mixed Egyptian/German woman. They had many children at their mansion in Perthshire, and also many financial problems attributed to Duleep’s spendthrift ways. Prince Duleep’s lawsuit seeking his rights to rule to Punjab didn’t succeed, just as the Maharaja of Coorg’s legal efforts failed. But in his middle age, Duleep managed to return to India and reunite with his mother, who’d never stopped pining for him.

Prince Duleep Singh

Prince Duleep SinghNot all royal travelers came to India against their will.

Maharaja Nripendra Narayan and his wife, Maharani Suniti Devi, were excited to leave the routine of life in the princely state of Cooch Behar for extended visits to England. Nripendra and Suniti hobnobbed with nobility and indulged in extravagant fashion. Their sons over-indulged themselves in the manner of British noblemen, with several following their father, the Maharaja, with alcohol-related early deaths.

The two youngest daughters from Cooch Behar, Princess Prativa (nicknamed ‘Pretty’) and Princess Sudhira (‘Baby’), were also often on these European jaunts. The sisters married British twin brothers (Lionel and Alan Mander). In Suniti Devi’s own Autobiography of a Princess, she writes that arranging these marriages was the proper solution because they would be considered unmarriagable by other Indian royal families.

Princess Sudhira Devi

Princess Sudhira DeviAs I consider the lives of these far-flung Indian travelers, it leaves a bad taste: a bit like Champagne gone flat. Inclusion in British life meant giving up so much of themselves. Nor could they be accepted for their changed manners if they returned to India, and sometimes, they couldn’t even enter the states where they were born. In many ways, their stories are a subtle echo of the much greater losses suffered by India itself.

The post The Latest Anglo-Indian Romance appeared first on Sujata Massey.

May 4, 2022

From Solitude to Left Coast, Malice, and Edgars

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Walter Mosley, near left, lunching with us at Malice

Walter Mosley, near left, lunching with us at MaliceOne hundred years ago, only a science fiction writer could have dreamed that being a writer would involve much more than a pen, typewriter, and some paper. Bookstores would take care of selling one’s work, and there would be the occasional exciting invitation to lecture at a private club or educational institution. And of course, written correspondence with admirers.

Imagine telling Mary Roberts Rinehart and Georgette Heyer that they’d need to add on sharing photographs and short messages about their lives to FaceBook, Instagram, Twitter and TikTok. And how would they like to hear that sitting in front of an electric machine that saved your words, had a camera to focus unsparingly on your face, a microphone to pick up your ums, would become the way you shared yourself with others? And would the writers of yore have delighted at the idea of mystery conventions, or thought them an abomination?

Is that a photobomber or Ghost of Honor at Malice?

Is that a photobomber or Ghost of Honor at Malice?Although I write in a room alone, I’ve had a quarter century to slowly learn the skills needed to be a modern mystery writer. During the pandemic, I found community in booktalks sponsored by stores and libraries and bookclubs. I even got my own zoom account so I could sponsor some interviews with writers and historians. But I got zoom fatigue, like a lot of people. I didn’t want to connect with a screen in the evening. I longed for the equivalent of an outdoor porch meeting with writing friends.

This spring, I got a fourth booster shot and prepared to go out into the world to two mystery conventions and the Edgars dinner. I tested myself for Covid before and after each outing, and was blessed to remain healthy. Some of my peers did catch the virus, and I’m relieved that they are either recovered or feeling much better. In my case, the trip was worth it, and I’m sharing a few highlights.

LCC Lineup: With John Copenhaver, Susanna Calkins and Catriona Macpherson

LCC Lineup: With John Copenhaver, Susanna Calkins and Catriona Macpherson Malice Lineup: with Lori Rader-Day, Gabriel Valjan

Malice Lineup: with Lori Rader-Day, Gabriel ValjanFirstly, I was going as a nominee. I had the thrill of seeing my 2021 book, THE BOMBAY PRINCE, receiving nominations for the Best Historical Award categories at both Malice Domestic Convention in North Bethesda, MD, and Left Coast Crime in Albuquerque, NM. This meant panels to talk about the book and lots of picture taking.

The actual Agatha award (given at Malice) and Bill Gottfried Memorial award (given at LCC) went to talented and kind author friends who’d written exceptionally original and well-researched historical mystery novels.

Lori Rader-Day’s Agatha award winner, DEATH AT GREENAWAY, is a brilliantly researched mystery set at Agatha Christie’s country house during World War II, when the famed author gave up her property to the government to be a temporary home for London children who’d been sent to the countryside for their protection.

The rest of the convention was all about people for me. Malice also honored my longtime reader-friend, Dina Willner, as Fan Guest of Honor. Throughout the convention, a group of her friends wore sashes reading Fans for Dina, a big surprise for her. The Fan Guest of Honor for Malice’s 2021 convention (which wasn’t held in person) was Dru Ann Love, a wonderfully talented blogger who also came to the convention and was delightful to spend time with.This was a pattern with all the spring gatherings I attended: people who’d won while everyone was stuck at home were belatedly celebrated in person.

I also had time with friends who are longtime readers, and with my terrific literary agent, Vicky Bijur. Whether a cup of tea or conversation at lunch or dinner, or even in the car, these conversations we had built trust and understanding of how to move forward in a career and keep publishing a happy experience.

Team Blue: Frankie Y Bailey and Lori Rader-Day

Team Blue: Frankie Y Bailey and Lori Rader-Day With Dina Willner

With Dina WillnerAt Malice Domestic, some of us had time in our schedules to get to lunch with the convention’s Lifetime Guest of Honor, Walter Mosley, who cofounded the organization Crime Writers of Color with a younger writer, Kellye Garrett, whose latest book, LIKE A SISTER, is making a big splash.

Kellye Garrett and Mick Herron

Kellye Garrett and Mick HerronA week earlier, I saw Kellye take on the toastmaster role at Left Coast Crime; in the shot above, she’s giving an award to the convention’s international guest of honor, Mick Herron, whose Slough House spy thriller series is now on AppleTV with a first season, SLOW HORSES. LCC was in Albuquerque, New Mexico, this time. This convention moves locations usually around the left side of the US (although it’s once been on England’s western coast and the same for Canada).

I was delighted to reunite with my California-based writer friend Naomi Hirahara at Left Coast Crime. We both started out writing mystery series connected with Japan, and as we have added different series to our bibliographies, we’ve also become members of an advocacy group, Crime Writers of Color. It was thrilling to see so many of CWOC members win!

LCC award winners Raquel V Reyes, Wanda Morris and Naomi Hirahara

LCC award winners Raquel V Reyes, Wanda Morris and Naomi HiraharaThis was especially a banner year for Naomi, with her first historical mystery. CLARK AND DIVISION is set in a world not much explored in mystery fiction. It deals with the hardships that Japanese-American citizens faced after the War, when they couldn’t return to their homes on the West Coast, often due to the economic and real estate losses caused by their imprisonment in concentration camps. A large number of them went to Chicago to start over with entry level jobs in an unfamiliar, cold place. The mystery in Naomi’s book revolves around the supposed suicide of a young Japanese-American woman on the eve of her family’s arrival. Just as in Kellye Garrett’s book, it’s a sister who finds justice for the one who perished.

At Left Coast Crime, I made the choice to stay a block’s distance from the main hotel in a small historic place, Hotel Andaluz. I found the atmosphere of the historic, Pueblo Revival hotel fed my soul and offered me intriguing places to write—not only my spacious room with thick, stucco walls, but these little nooks behind the tiled fountain in the lobby.

I got to have a lots of nice walks, including through a residential neighborhood, to little restaurants, and The Man’s Hat Shop, where I got a marvelous new topper to protect me from the Albuquerque’s strong sun.

The hat shop dates from 1947

The hat shop dates from 1947

My last spring trip was short but especially vibrant. In late April, I went to New York City to celebrate the Edgar Awards, a gala presentation conducted by Mystery Writers of America members to honor the best books of the year, as decided by reading committees made up of authors in the organization. It was relaxing to sit near Vicky and other friends, close to the table with two fellow Soho authors with award nominations: Naomi Hirahara (winner of the Mary Higgins Clark award) and Kwei Quartey (finalist for the Sue Grafton Memorial Award).

Edgars Dinner: Frankie Bailey, Kim and Shawn Cosby, and Chris Chambers

Edgars Dinner: Frankie Bailey, Kim and Shawn Cosby, and Chris ChambersI was honored to go onstage and introduce my editor, Juliet Grames, who was receiving the Ellery Queen Award for her accomplishments as a mystery editor and an associate publisher of Soho Crime. I struggled to find the words to introduce my dear friend—because so, so much could be said. In the end, I spoke for about a minute, and I was thrilled that Juliet’s award—and a few of my words about her—made it into Publishers Weekly.

The morning after, we were all business. I went to Soho’s light-filled offices in a historic building in Chelsea and met with Juliet and my new editor, Yezanira Venecia, to discuss their thoughts on my manuscript for the fourth Perveen Mistry novel. Chiefly, we brainstormed about how to make each character’s motivation more realistic—and how to tweak events to match up better with revelations of the plot. A few lost pieces began matching up in the gigantic puzzle that will be titled THE MISTRESS OF BHATIA HOUSE (Yeza’s title idea!).

My editor, Juliet Grames, EQ award winner at Edgars

My editor, Juliet Grames, EQ award winner at EdgarsRiding home from New York on the train, I was tired but happy for the resumed connections in publishing. Yes, a writer’s life is more complex now. And mysteries are similarly more complicated, especially if they’re part of an ongoing series. Sometimes, spending time with a few more plotters is just what’s needed.

Soho staff, authors and friends

Soho staff, authors and friendsThe post From Solitude to Left Coast, Malice, and Edgars appeared first on Sujata Massey.

April 20, 2022

The Book Challengers

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

I was messing with my books today and turned them so that the spines were hidden. No titles, no idea of content. They seem like a visual representation of how powerless books are if we don’t see what they’re about.

Blank books remind me of silenced voices. The volumes make me think of the growing movement inside the United States to ban books from schools and public libraries. In 2021, almost 2000 titles were challenged by citizens, according to this recent New York Times article. Much of the banning action is in states like Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas.

The book challenges bring back memories of my own relationship with libraries. Back in my 1970s and ’80s childhood, we were regulars at the public library. My mother usually drove me and my two sisters to the Ramsey County public library once a week, sometimes twice during summer vacation. I walked to the beautiful little Carnegie Library in neighboring St. Anthony Park myself, and of course, I always got books from the school library when my class had visiting time. My father always gave us books specially chosen for our particular interests at Christmas and birthdays. He still does; and I do the same for him.

I recall vanishing into the faraway, much more charming worlds of these library books. I adored a series about a Jewish family in turn-of-the century Brooklyn (All of a Kind Family). I marveled at the hardships of pioneer children in the Midwest (the Little House books), and the fantasy landscapes in The Dark is Rising Sequence. My sisters and I also read close to one hundred Amar Chitra Katha children’s comic books that my father got for us in India. This Indian publishing house, founded in 1967, specialized in the pictorial depiction of religious stories, epics, folktales and South Asian history. The comics felt special because they told me something about the country of my heritage, when the libraries had no books about it except for those by British Colonials. As my sisters and I matured, we were attracted to reading darker themes, especially books set during World War II that detailed the Holocaust. With the other half of my personal identity rooted in Germany, I felt a dissonance between my own experiences in the country and the history emerging for me in literature.

I recall a handful of children’s books with Black characters. However, when I recently researched the books’ authors, I discovered they were all White. In my late teens, the first African-American author I read was Maya Angelou, followed by Alice Walker and Toni Morrison. As a teenager, I finally got a peek behind the curtain shielding the mysterious and alluring world of sex. My favorites were Rosemary Rodgers’ Sweet Savage Love, and an erotic essay collection by Nancy Friday, and the ultimate mind-blower, Rita Mae Brown’s tour-de-force novel about lesbianism, Rubyfruit Jungle. Not that these particular titles were carried in any of my libraries: I remember buying My Secret Garden using my weekly allowance, and getting a battered second-hand copy of Rubyfruit Jungle handed to me by one of my sisters.

Prior to 1999, most books removed from school libraries were done so due to profanity and sexual or political content. Think George Orwell’s 1984 and J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

The next area where books were attacked was in a perceived threat against Christianity. I remember back in the early 2000s, some conservative parents had success banning J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books using the argument it encouraged witchcraft.

One of the strangest recent bans is against mathematics textbooks in Florida. Its Governor, Ron DeSantis, has not named the titles of the books involved, nor the instances, but the state department of education has rejected 70 percent of math materials for K-5 students, 20 percent of math material for Grade 6-8, and 35 percent of the math materials for grades 9-12. With the hiding of book titles and any excerpts deemed offensive, it seems absolutely crazy that this recall could succeed. He’s also requiring all schools to provide a searchable list of all books in their libraries for parents, and to continue updating parents with details of every book that the school acquires.

After looking at the lists of the most banned books in the United States, I’ve come away with the impression that the challenged books are mostly be by LGBTQ authors and writers of color.

Here is a tiny sampling of some of the most often-contested books that some people are trying to keep out of libraries.

Nonfiction

Caste by Isabel Wilkerson

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

The End of Policing by Alex Vitale

Fiction

The Autobiography of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neal Hurston

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Beloved by Toni Morrison

The Color Purple by Alice Walker

The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas

Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You, by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi

All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely

Are you wondering exactly who the people are who are fearful of books about social issues?

Often, they’re parents who complain to a teacher or principal. Or library volunteers quietly snapping pictures of books that they are shelving. They could be church or political party members taking their issue with a book to a lawmaker who wants their support.

In Virginia, just south of my home state of Maryland, Glenn Youngkin ran for governor promising to prohibit teaching of course material that addresses the history of racism (in his words, critical race theory). He won the election.

Texas State Representative Matt Krause is running for re-election in a tightly contested primary. He created a list of 850 children’s and young adult titles he believes could make youth feel uneasy or uncomfortable or guilty. He sent it to the state’s school boards and asked them to let him know whether they had any of these books in the school libraries.

Censorship activism has been nicknamed by some as the Ed Scare as a reference to the 1950’s “Red Scare.” Seventy years ago, people were so afraid of losing their jobs that they signed oaths professing no connection to the Communist Party. Today, librarians might keep a book behind a counter, or teachers would think carefully about what they can share during read-aloud time. Some of the proposed bills could criminalize the teaching of a book that someone judges to be obscene.

Last week, I received an email from one of my past publishers. Jonathan Karp, the CEO of Simon and Schuster, wrote to its authors about the publisher’s intention to stand firm and keep publishing books without fear of censorship. It also included resources for readers and writers to fight book challenges.

The New York Public Library and the Brooklyn Public Library are allowing people across the country who aren’t NYPL cardholders to borrow banned books as digital downloads. It’s a generous move made to support access, but it also reveals the tragedy of how different library culture is from state-to-state. After all, the people in Texas and Florida pay taxes to support these libraries, so they can have access to what they want to read.

The post The Book Challengers appeared first on Sujata Massey.

April 6, 2022

Staying Above Water

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

It takes just two tanks of gas to get the 1,100 miles between here and Southern Louisiana—and no tolls to pay, either. I know this because last week, I drove there with my husband to see his mother and brother and the rest of the family. Sharing the driving made it relaxing, as well as our decision to stay in old hotels and inns both ways.

Louisiana is the kind of place where there’s so much to look at, taste, and feel that I inevitably become interested in something unexpected. This time, I saw the rebuilding of houses after Hurricane Ida. I casually use the expression “keeping my head above water” to express that I feel too much is going on. But in Louisiana, that phrase is literally something people worry about every fall.

Tony grew up with his older brother, Don, in Metairie, a near suburb of New Orleans. A few years after the destruction of 2005’s disastrous Hurricane Katrina, both my mother-in-law and my brother-in-law worked hard to rebuild their properties. And then they both made decisions to get farther away from the Gulf, settling in the towns of Mandeville and Covington. These neighboring towns lie on the north side of Lake Pontchartrain, a massive body of water that has a 35-mile long causeway that connects it to New Orleans and its near suburbs.

While still classified as South Louisiana, my in-laws’ new home base—part of St. Tammany Parish—is too far to be at risk from a gulf surge. However, there is that lake I just mentioned. 630 square miles.

Don’s spacious house was built on pilings 20 feet high. It lies about two blocks from Lake Pontchartrain. My mother-in-law’s nursing home in nearby Covington was built far from the lake. However, it is vulnerable to the threats of wind damage and power outages.

Tony remembers many hurricanes from his childhood in the 1960s through the early eighties. He recalls the routine of piling into the car and evacuating to a motel in Northern Lousiana whenever the evacuation orders came. After 1969’s devastating Hurricane Camille, my late father-in-law, Sam, took Tony and Don on a road trip along the coastline of Louisiana and Mississippi so they could see things like massive fishing boats run aground into the middle of shopping districts.

Katrina is the biggest hurricane on record for Louisiana. Reaching Category 5 status in the ocean, it reduced slightly to a Category 3 hurricane when it arrived in New Orleans. The water surge was so forceful that several New Orleans levees failed. Much of New Orleans flooded, with people drowning in their own houses or on the road when they tried to flee. Katrina caused 1577 deaths in the state, with smaller numbers of deaths in Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama and Florida, as well as plenty of property destruction.

When Katrina came, Tony’s family was safely evacuated to North Louisiana. However, their homes in Metairie were damaged. Don’s home had flooded; even though it was less than a foot, that was enough moisture to destroy all the walls. Part of the roof was pulled off at the house in Metairie where the boys grew up and Tony’s mother, Harriot, still lived. Harriot came to live with us in Baltimore for several months, until Don had overseen the completion of repairs to her house; his took a lot longer.

They were among the lucky ones. Other people never were able to salvage their houses and became renters. Thousands of people left New Orleans as disaster refugees, their homes and possessions destroyed, and settled in other parts of the country.

Katrina brought so much pain that Hurricane Ida arriving in 2021 seemed like a cruel cosmic joke. I’d planned to be in New Orleans in September 2021 for the Bouchercon World Mystery Convention. In late August, I reluctantly cancelled my hotel and flight because Delta was spreading exponentially in Louisiana—faster than anywhere else in the country. Enough Bouchercon participants were cancelling for this reason that the convention organizers opted to cancel that year’s convention, postponing the hotel reservation for a future year. Lo and behold, Ida announced she was coming into town that very weekend.

Ida came on Sunday, August 29, with 150-mile an hour winds and heavy rains. Evacuation had been recommended and most people, but not all, had left New Orleans. Fortunately, the redesigned levees held the water from flooding the city. The greatest damage came from the fierce winds. An estimated 92 people died due to the storm in nine states.

Tony’s mother stayed in the nursing home and all was well there, given its good location and back-up power sources. Don, his wife and youngest daughter evacuated north. It was a good thing, because their part of Mandeville was flooded, leaving two feet of mud in the open area under the house where his cars would have been parked, if he hadn’t removed them.

House elevated on pilings in Old Mandeville

House elevated on pilings in Old MandevillePeople in Louisiana are used to storms, and they clean up as fast as they can afford—and if FEMA and insurance come through for them. This time around, because of pandemic supply chain problems, construction supplies took months to arrive—and construction workers were in short supply, as they are across the country.

A neighbor’s house on temporary risers

A neighbor’s house on temporary risersAs I walked around the neighborhood filled with lush trees and tropical foliage, I noticed most houses were on pilings, and others were in the process of being raised, with blocks underneath. I gazed into the neighborhood’s ditches, a historic and simple way to assist with the diversion of overflowing lake water. These ditches are cut into the earth alongside the roads near the lake. The ditches held murky water, weeds, and occasionally, visitors from the lake. We were advised to go out walking carrying a long pole in order that an alligator might emerge and behave aggressively. During our walk, it turned out the gators had better places to be.

I paused at one house right on the lake that was vastly bigger than the others with an unusual wrap-around style. Someone had recently bought the acreage, which originally had an old, small house on it. The original house had very inexpensive flood insurance. In order to keep the same low insurance rate, the home buyer could not tear down the original residence. Instead, he built his dream home to encapsulate the old one. And yes, it’s on stilts—but because he elevated at 15 feet, rather than 20, the space below isn’t high enough to house all his vehicles.

The truck on the left just can’t make it in

The truck on the left just can’t make it inMandeville has a charming historic section nestled along another stretch of the vast lake. In “Old Mandeville,” you can eat biscuits and shrimp and grits at Café Lalou and shop for candles and vintage towels at a number of small shops. The town was developed as a summer resort community for wealthy New Orleanians to visit in the mid 1800s through the early 20th century. Most of the historic cottages in this area were built so long ago nobody thought about elevation from possible lake flooding. Many of the vintage cottages still rest on the ground, while others are getting a boost.

Classic old Mandeville cottage

Classic old Mandeville cottage A historic lake-side building in the process of rising

A historic lake-side building in the process of risingWhile we were in Louisiana, we visited Randy, my husband’s close friend since primary school days in Metairie. Sitting together in 79-degree warmth of a back yard in Covington, Randy mentioned he was part of the Cajun Navy. This informal volunteer group—which came together around Hurricane Katrina—is a term for the owners of private small boats who drive them into flooded areas to rescue people trapped in their homes.

Randy has driven his boat as far as Texas to assist in rescue missions down flooded highways. When Ida came and power was lost to many neighborhoods around Lake Pontchartrain, repairs were delayed because of giant fallen trees that blocked access to streets. Randy got in his own truck, brought some saws from the garage, and went to a neighborhood and chopped the trees apart so the neighborhood could be entered. He did this because he knew about a friend’s elderly mother living alone in this cut-off neighborhood. He got to her and brought her out to stay with him and his own family until her neighborhood’s electricity was restored.

The ongoing work of Randy and other volunteers in Louisiana reminds me of a legendary water rescue in Europe known as Operation Dynamo. In the aftermath of the Battle of Dunkirk in 1940, 338,000 British and Belgian soldiers were trapped on the beach in France. Nazi forces had control of the town. British people living along the coast sailed out to rescue them at the French beach, assisting the Royal Navy. Saving so many lives was a miracle and surely essential to the Allies ability to continue the war and ultimately defeat the Axis powers.

To drive away from the threat of surging water, leaving everything behind to uncertainty, is a fear I’ve never experienced. Just as I could not picture myself commandeering a boat on flooded highways. But with a lifetime of storms, people can gain extraordinary strength.

The post Staying Above Water appeared first on Sujata Massey.

March 23, 2022

Happy Navroze—Spring is Here!

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Farida’s extended family at 2022 Navroze in Kolkata

Farida’s extended family at 2022 Navroze in KolkataJamshedi Navroz Mubarak!

According to the old Persian calendar, March 20 or 21 is the day that the new year named Navroze, Navroz, Nawrooz, and various other spellings is welcomed. This observance mostly celebrated by Zoroastrians—the group inside known as Parsi; Bahai worshippers; and Sunni Muslims with roots in Iran.

I “crashed” Navroze when I was twenty-five and visiting India with my father.