Sujata Massey's Blog, page 10

February 24, 2021

Mithan Lam, A Powerful Advocate for India’s Women

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

The barrister Mithan Jamshed Lam

True tales of women breaking barriers to forbidden places, and bettering the lives of others, are inspiring. Mithan Jamshed Lam is one of these legendary women. Recently I chatted about this illustrious lady (who passed away in 1981) with another woman who is doing important civil rights work in contemporary India, the Mumbai solicitor Parinaz Madan. In an interesting twist, Parinaz is married to Dinyar Patel, a professor and author of Naoroji: Pioneer of Indian Nationalism.

I was fortunate enough to meet Parinaz and Dinyar in real life last January at the Royal Bombay Yacht Club in Mumbai. We dined on a delicious biryani and many other dishes as we discussed the history of the city and the freedom movement. They are both Parsis and have been kind enough to also answer my questions about the minutiae of the community’s cultural life. Their assistance was key in creating realistic social situations in my forthcoming novel, The Bombay Prince.

Last year, Parinaz and Dinyar wrote an article for BBC News about Bombay’s first woman barrister, Mithan Ardeshir Tata, known after her marriage as Mithan Jamshed Lam. In 1924, Mithan became the first woman advocate permitted to argue cases at Bombay’s High Court. Mithan’s education, family background, and relentless struggle for women’s rights were influential in the development of my series protagonist, Perveen Mistry.

It was much harder for me to find scholarly material about Mithan than Cornelia Sorabji. In 2016, I bought a reprint of her autobiography, Autumn Leaves, at the K.R. Cama Oriental Institute, a center for Parsi scholarship. The autobiography is dominated by the stories of Mithan’s world travels. I wanted to know specifics about her life in India, so I’ve put some questions to Parinaz about her.

Were Mithan’s parents encouraging of her career choice as a lawyer? Were there any other events in her youth that pushed her toward the field?

Mithan’s autobiography lends the impression that her family had very progressive leanings.

She describes her father Ardeshir as a man of “liberal views” who wholeheartedly backed her academic pursuits. In fact, her father spurred his studious wife Herabai to complete her B.A. degree, by employing a number of tutors for her.

Mithan also seems to have shared a very close and almost sororal bond with her mother, which is not surprising, considering that they were separated by only seventeen years in age!

As a teenager, Mithan was clearly inspired by her mother’s social activism and commitment to securing equal voting rights for women and that likely set the stage for her active participation in the female suffragist movement subsequently. She was all of 21 when she was chosen, alongside her mother, to deliver evidence on the necessity of female suffrage in India to the British Parliament.

Mithan had a stellar academic track record even before studying law: she obtained her B.A. from Elphinstone College, Bombay and was the first woman to be awarded the Cobden Club Medal for securing the highest marks in Economics. She then went on to pursue an M.Sc. degree from the London School of Economics, while her mother was studying for a Social Service course at the same university.

Since Mithan’s childhood and early life were steeped in political and social activism, law may have seemed to be the most natural career choice for her. She probably recognised the potential of a legal career to create lasting and meaningful reform in areas that she deeply cared about, such as women and children rights, and was ably supported by her parents along the way.

Mithan, standing by her mother, Herabai, in 1919

Cornelia Sorabji is arguably the most renowned female lawyer from colonial India. Her career was divided between private practice in a firm with her brother in Allahabad, and many more years working throughout India as a legal investigator for the Indian Civil Service. She was almost 31 years older than Mithan, but was called to the Bar in Britain (i.e. admitted to practice in courts) after Mithan. Could you explain why that happened?

Yes, Cornelia was the first woman to study law at Oxford in 1889 (nearly a decade before Mithan was even born). However, she could not be called to the Bar after finishing her law exams because women were prohibited from practicing law in Britain, until the passage of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act, 1919.

This Act which opened the doors for women to be admitted to the Bar in the United Kingdom was passed only in 1919. Mithan who was fortuitously in London at the time was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn in 1920, followed by Cornelia who returned from India to Britain two years later. Mithan became the first woman to be called to the Bar at Lincoln’s Inn in January 1923 when she was 24. Cornelia was actually called to the Bar a few months later than Mithan in June, when she was 55.

Providentially, the Indian government also abolished restrictions on women to practice law in 1923: the same year that Mithan set sail to India after finishing her studies in London. This enabled her to kickstart her legal career as the first female lawyer in the Bombay High Court in 1924. I think she sums all this up quite aptly in her autobiography: “I must have been born under a lucky star, for I always found myself in the right place at the right time.”

What was Mithan’s life like when she started working as a barrister? Did you uncover any stories of success and struggles against discrimination?

Ironically, Mithan bagged her first legal case from a client who wanted to “inflict upon the opponent the humiliation of being defeated by a woman.” She recalls feeling like “a new animal at the zoo” while appearing in court, arousing the curiosity of men who peeped through its doorways to catch a glimpse of this unique species. Understandably, this made her feel extremely “self-conscious”. Such acts of discrimination notwithstanding, newspaper records reveal that Mithan practiced in court for about 15 years from her enrolment as a lawyer in 1924 in India.

Mithan was extremely outspoken on women’s rights. Tell us about some of her work in that area, and the legislation she proposed.

Apart from the female suffrage activities that Mithan is renowned for, she was a staunch advocate for amending marriage, divorce, inheritance and guardianship laws in India to make them fairer to women, often drawing upon international legislation. As a Zoroastrian herself, her legal expertise was sought in reforming the laws for marriage and divorce in the Parsi community.

One of the women’s organisations that she was most prominently associated with was the All-India Women’s Conference. As its President, she propounded a shift of focus from “sewing and cutting classes” for women to their more active participation in industries and emphasised on the need for family planning. She also encouraged women to take a more active role in civic engagement and public works in the country. After the partition of India in 1947, Mithan was tasked with being the Chairperson of a committee constituted for resettling refugee women and children in Bombay.

But her activism was not restricted to only women’s issues. She also spearheaded hunger eradication programs, anti-child labour advocacy and slum improvement projects in India. In 1928, she joined protests with the Bombay Youths League about a proposed school fee hike for secondary education in India. The Bombay Chronicle noted “The ridiculous plea that higher education should be further taxed to find funds for primary education is aptly described by Miss Tata as the policy of robbing Peter to pay Paul.” These protests may have had a hand in the government backing down on the fee hike attempt for colleges and schools eventually.

Mithan married in 1933, probably at age 35. Do you know anything about her husband Jamshed Lam’s feelings about her continued activism and legal activities?

I will let Mithan’s autobiography do the talking for this question. She describes Jamshed, a lawyer himself, as “a wonderful and loving husband” who “was proud of my achievements and helped to advance me in every way….I have been greatly lucky in my menfolk–a liberal father of very advanced views, a loving and generous husband, and a fine son of whom any parent would be very proud.”

How do you describe Mithan’s legacy for women in India?

Mithan left behind an invaluable legacy for women in the legal profession and beyond. Demolishing patriarchal stereotypes of what a woman can and cannot achieve, particularly in traditionally male-dominated fields, was the cornerstone of her career.

While Mithan was a woman of many firsts, she did not work in silos but mentored scores of other women. Prominent among them was Violet Alva who was a law student at Government Law College, Bombay when Mithan was a professor there. Violet subsequently went on to become the Deputy Home Minister of India and the first female Deputy Chair of the Rajya Sabha (the Upper House of Parliament). Examining the life stories of trailblazing women like Mithan makes us realise that a lot of rights that we, as Indian women, enjoy today, such as the right to vote or work, were achieved on the back of the unwavering efforts of such pioneers.

Parinaz Madan

As a solicitor in Bombay, you work hard as legal advisor at a prominent company, yet you make time for pro bono work. Tell us about the pro bono organization you work with.

In addition to the corporate law work I do, I am also a member of iProbono. It is a global organization which connects lawyers with non-profits and social enterprises in need of pro bono legal assistance. Over the past few years of my association with iProbono, my work has involved advising schools, innovations labs, mental health professionals and organisations working for the underprivileged on a number of education, child rights, disabilities and medical laws in India.

Law is a very potent instrument for social change and I believe that in a developing country like India, especially, there is tremendous scope for lawyers to create systems and establish precedents from the ground up.

You’ve said that India has some of the strongest child abuse laws in the world, but these laws aren’t often exercised properly. Can you give an example of how this could be changed?

In 2019, the Economist Intelligence Unit published a report evaluating the response of sixty countries, across the development spectrum, to the scourge of child abuse. Interestingly, India ranked the highest amongst all the surveyed countries in terms of the strength of its legal framework for protecting children from sexual abuse and exploitation. However, awareness of these laws remains low and their implementation remains challenging, given the high rates of child abuse in the country.

Now, child abuse is a very pervasive and complex problem and its eradication needs resolute engagement from various stakeholders, both government and private. However, one of the ways in which organisations interacting with children (like schools, children’s shelters etc.) can mitigate child abuse is by developing effective child protection policies, as an article I’ve recently written demonstrates. Such policies typically contain a blend of preventive and remedial child protection measures. In the absence of such policies, organisations often deal with child abuse incidents arbitrarily and without regard to the law, causing grave prejudice to the interests of children under their care. Through iProbono, we assist various civil society organisations in drafting and implementing child protection policies, to foster a safe and child-friendly environment.

The pandemic has many people working from home. Do you see this is an opportune time for more persons with disabilities (PWDs) to have a chance to enter the Indian workforce? What are the factors that make it difficult for PWDs to work? Is there a national law in existence for enabling disability inclusion in the workplace?

The employment rates of PWDs in the Indian corporate sector are abysmally low barring, of course, a few outliers. A study published by the Business Standard in 2019 noted that PWDs constitute less than 0.5 per cent of employees in India’s top companies. In India, the Rights of PWDs Act, 2016 is a national-level legislation that requires companies to develop equal opportunity policies and create an accessible environment for their employees, but its implementation remains patchy.

Historically, taboos associated with disabilities and low literacy levels have kept a lot of PWDs out of the workforce. Social isolation and a lack of employment opportunities, posed by the Covid-19 crisis, have hit PWDs further.

But, some disability rights activists see a silver lining to this crisis: the pandemic has impelled companies to adopt remote working policies and technologies which certain groups of PWDs have long demanded as reasonable accommodations. Needless to say, it is imperative that such technologies are designed to be accessible to PWDs, to facilitate their meaningful participation in work. In a 2020 piece I wrote for Business Standard, I’ve argued that there is a strong legal, business and moral case for disability inclusion in the Indian corporate sector, particularly in the light of the pandemic. I think the ILO’s Director-General summarizes the essence of this fittingly: “A disability-inclusive response means a better response for us all.”

The post Mithan Lam, A Powerful Advocate for India’s Women appeared first on Sujata Massey.

February 10, 2021

The Price of a Meal

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Someone who’s part of my inner circle is working on a novel. He made a richly detailed first draft and is engaged in getting feedback from a few trusted friends. Two early readers of his book commented the story had too many references to food. One even suggested that he reduce the number of group dinners in the story down to two grand banquets.

I feel for any writer having to make choices about cutting out an aspect of storytelling that they enjoyed creating. And it’s not wise to cater to everyone’s opinion.

My Dear One was asking me for advice about this. And I told him that I think food in books is important. However, the cost of not handling food correctly can be reader boredom.

Every sentence that goes into a book should advance it. And therefore, when characters sit for meals in books, they can’t just eat.

Mushroom soup has poison potential

If that sounds confusing, let me start in a backwards fashion Here’s what meals in books should not be:

Time fillers, thrown in because you are passing through the chronology of a character’s day. Such as… after finishing the interview at the police station, Joe and Jane went to a restaurant across the street and had fish and chips, two cokes, brownies for dessert. It was a tasty meal that was easy on the wallet. Then Jane checked her watch and suggested to Joe they go to the park to see if they could find what the police might have had missed.

A menu of your favorite things, just because they came to mind while writing. For instance: Angelina opened the menu and ordered French Onion Soup, followed by lo mein with chicken and shiitake mushrooms, and chocolate mousse, with a Bud Light on the side.

A way to simplistically broadcast to the reader that certain foods are eaten in certain countries. Ciao, I’m in Italy, so it’s pizza time! Or Namaste, because I’m in Delhi, I’m going to get some spicy curry!

Eggs Kejriwal is a more culturally specific dish than ‘curry’

In my Dear One’s case, he hadn’t committed these well-known faux pas. He merely wanted to share food as a means of explaining culture: the same way he offers delicious, varied international meals to family and friends. He was inviting his readers to a feast in every country the characters visited.

I shared my belief that food is one of the most tantalizing means to advancing a plot—in so many ways.

Peach salad for a health-conscious tea

Whether in homes or restaurants, aboard boats or inside tents, meals are opportunities for action and plot advancement. Meals provide meeting point for lovers, enemies, old friend and embittered relatives. Even in the case of a person dining alone, there’s a possibility for sunlight to spark off a crystal goblet and reveal an overlooked clue in a baffling mystery.

Conversations between characters over a meal also are gold. And not just words, but the ways in which people eat, and also do things like swallow hard, throw down their napkins, or play with their forks. Someone’s zest for a meal, or lack of appetite, is telling.

Also, the kind of food that’s served reveals a lot about the meal’s host, and about the diner. In The Widows of Malabar Hill, my heroine Perveen Mistry visits a British home in colonial Bombay and is offered an uncharacteristically modest afternoon tea of fruit and sandwiches. This points out the fact that the hostess, Lady Gwendolyn Hobson-Jones, is more devoted to weight watching and appearances than pleasing appetites—and also, by her menu choices, doesn’t embrace Indian food and culture. Later in the story, Gwendolyn’s daughter Alice comes to the Mistry home and is offered a typical Parsi lunch that includes a rich fish curry, eggs, meat, many vegetables, breads, rice, and sweets. Alice begs to know what every food is called and wants to make sure the usual amount of chilies weren’t spared. Alice’s enthusiastic dining endears her to Perveen’s mother and also lets the reader know that while she might appear to be an outsider, she’s a progressive woman who wants to bend herself to becoming part of India, rather than dominate it.

I not not only love eating food—I like reading recipes, cooking, and dreaming. And what I prepare, while I’m working on a book, often reflects what I’m trying to learn about. Eating poached eggs cooked atop sautéed spinach and tomatoes with green chili and ginger puts the taste of Parsi India into me. And I don’t follow any particular dietary track. I’ll pan fry crumpets one day and bottle up a fresh turmeric, salt and lime pickle the next.

Roasted vegetables can build many dishes…and plots

My unorthodox cooking habits reveal that cooking is as much a form of creative exploration for me as writing is. However, when I sit down to eat something, I don’t think about food as adventure or character or story. I’m there for the taste.

The post The Price of a Meal appeared first on Sujata Massey.

January 27, 2021

The Angst of Small Dogs

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Daisy, what do you think?

Less than 40 miles from here, some big dogs moved into a big house.

Two German Shepherds. The old one, at age 12, is a fellow named Champ, and the younger one, Major, is two. Major had been left by his previous owner at an animal shelter in Delaware. After President Joe and Dr. Jill Biden adopted him, he’s now the nation’s second dog, or perhaps vice-dog? Champ, with his years of experience, is clearly Top Dog.

Stop your kvetching. Yes, Champ and Major are show-off, macho names. However, a flower name like yours seems incongruous. What’s that? You worry they look like they’re partly wolf? There’s controversy over whether wolves were bred into the German Shepherd community in the late 19th century. It might be. But remember, all dogs, large and small, are descended from wolves.

In any case, shepherds are intelligent, loyal, and protective—just like Yorkshire terriers, but at upwards of 80 pounds. They are working dogs, often used on farms and with the military and police.

Oh, so now you’re bragging about your own working dog origins. It’s true that Yorkshire terriers were originally used to catch mice in the mills and factories of England. However, the last time that you were in the room with a live mouse, I was yelping, and you were sleeping.

I understand that the arrival of Champ and Major at the White House makes you nervous. And while I’ve met some great German Shepherds, some have been a bit more mouthy and assertive than made me comfortable. But I haven’t heard anything crazy about these dogs. I believe the Bidens can shepherd these Shepherds.

You’ll be fine, Daisy. We aren’t going on a march in D.C. to protest these newcomers. And don’t ask me for my credit card number. Move On is not taking contributions to fight for your cause.

And I promise, even if I do go to the White House someday, I won’t pet them.

The post The Angst of Small Dogs appeared first on Sujata Massey.

January 13, 2021

A Meditation on Boundaries

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

I-Screen by Dhruvi Acharya

“Breaking Boundaries” is an expression that is usually meant to show freedom—crashing through a fence that prohibits expression. But there’s another side to boundaries.

And that’s “Holding Boundaries.”

The first boundary I recall is a low brick wall that marked the edge of the front garden of my first home in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, England. At age four, I played close to the wall, and this was how I visited other children in the neighborhood: playing on the sides of the garden walls.

Once, my younger sister breached the wall to toddle after a fire engine. She was safely retrieved, yet my mother’s panicked reaction to my sister’s boundary violation is the second part of the memory.

This week, a huge fence is going up in Washington D.C., supposed protection for those participating in President-Elect Joe Biden’s inauguration. This physical barrier can deter some behaviors, but it cannot do anything to erase the danger we face.

I started feeling this way last winter, when doctors around the world pleaded for people to wear face masks. Across the country, mask adherence is spotty, and a number of people say that not wearing a mask is a defense of their personal freedom. Last week, when seditionists stormed the US Capitol, members of Congress escaped and huddled together for hours in a small, undisclosed location. Six Republican House members refused to wear masks. Three members who wore masks caught COVID-19, quite possibly from one of these people. Because the boundary wasn’t observed by everyone, it didn’t work.

“Holding boundaries” is an expression used in counseling practice and self-help books and sometimes causes an eye roll. For me, it means following my gut, rather than giving in to pressure. Holding a boundary might mean saying “Sorry, I can’t come to that party,” or “I don’t want to get involved in that argument,” or as simple “no.”

The U.S. Constitution is packed with laws, and garnished with amendments, that are meant to protect the country from corrupt government and ensure its stability and articulate the rights of citizens. However, none of it works if people don’t pay attention to it. Vice President Michael Pence knows that President Trump did all but throw him to a mob, yet he won’t exercise the Constitution’s 25th amendment, which could remove a president unfit for duty. And what of the 147 Republican lawmakers who won’t accept the certified results of the 2020 election of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris? Who won’t accept… the law?

The challenge with boundaries is that you can’t yoke people into them. We hold them because of the people we are.

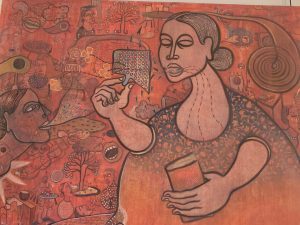

About nineteen years ago, I bought a painting called “I-Screen” by an Indian woman painter, Dhruvi Acharya, who had a one-woman show in Baltimore. I remember settling down on a bench and staring at the vast amount of huge paintings, looking for the one that spoke to me most.

It was a big red painting, 50 inches square, that called to me. In “I-Screen,” a mature woman with a peaceful expression appears to be defending herself against a stream of angry words coming from a younger woman. The screen in her hand is a simple vegetable grater.

As years passed and life tested me, I began to understand the story within the picture. The loving elder lets the words come at her, but she protects herself. She reminds me to stay true to myself.

The post A Meditation on Boundaries appeared first on Sujata Massey.

December 30, 2020

The Unraveling Myth of Johns Hopkins

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Johns Hopkins University Library

Have you heard? Another historic myth is being pulled apart like a sweater with moth holes.

Johns Hopkins, the great Baltimore businessman and founder of a university and hospital, wasn’t quite the social reformer that history told us. Recently, Hopkins historians shared news that he was a slave owner, rather than an abolitionist. And this controversy has made me reflect on my own journey to Baltimore and my relationship with Baltimore.

It started back in the 1980s, when I was a high school senior contemplating college. I knew I wanted to leave Minnesota, but I wasn’t sure where I should go. Geography was not even taught at my public school in Minnesota, so confusion was perhaps natural. When faced with a choice, I wondered: was Baltimore a Northern East Coast city, or was it a proper part of America’s South?

The Hopkins statue in front of the university

Baltimore lies south of the Mason-Dixon line, a geographic boundary from the 1700s that was later used to mark off Confederate and Union sides during the Civil War, it wasn’t entirely clear to me. The South was less appealing to me than the Northeast, but Baltimore, Maryland, was where I got the most out-of-state scholarship money. And I was desperate to leave the Midwest.

When I arrived at the Baltimore airport for the first time, I felt welcomed by a bus driver, but I could only understand a few of his words. So, it was the South! It took me at least a month to be able to translate the vowels of many locals. By the time I went home for Christmas, I didn’t hear anything strange. Furthermore, my own accent had changed to the point that one of my sisters said I sounded like a ‘snob.’ I didn’t care. By then, I was very excited about the place I’d landed: Goucher College, a historic women’s college in Towson, a suburb just north of Baltimore.

One of the first surprises at Goucher that another Indian-American student with my first name had recently graduated. It meant that “Sujata” was easily spelled and pronounced throughout the college—a big difference from Minnesota, where I was tormented for having a foreign name. Heubeck Hall, my dormitory was diverse, with women from around the world, and, like me, immigrant backgrounds in the United States. The Black students in my dorm had mostly graduated from Baltimore and Baltimore County high schools. It was easy to make friends with them as anyone else—a big difference from high school, where my name, skin color and national origin made me an outsider.

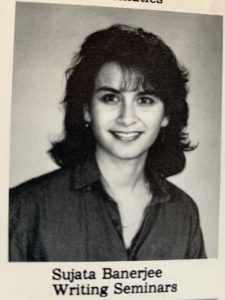

Even though I had good friends and caring professors during two years at Goucher, my career focus shifted toward a writing career, so I transferred as a junior to Johns Hopkins to study in the Writing Seminars department. At Hopkins, I was embraced into the heart of a very international, multi-racial circle who socialized in Gilman Hall. Here, every Black student I knew either came from out of state, or the African continent. This was very different from Goucher.

I regret not thinking about this discrepancy during my time at Hopkins. I thought all that battling racism meant agitating for the end of apartheid in South Africa by pressuring Johns Hopkins University to divest its stock portfolio. I didn’t think about the informal apartheid in Baltimore that sent white kids to private schools, lest they go to the “terrible” public schools. I was aware that the university was set on land that had originally been a plantation owned by wealthy Catholics, John and Harriet Carroll. The plantation house was a small museum on campus; the fact was not hidden. These days, there are markers throughout the campus pointing out more of its slave history, including where the slave cabins once lay.

Homewood House Museum

I still come to campus regularly; and when the Hopkins library is open to the public, I’m usually there weekly, writing quietly away in the place where I first dreamt dreams of writing novels and articles. My academic advisor, Bob Arellano, shaped my life trajectory by insisting I apply for an internship at the Baltimore Evening Sun. My junior year internship at the paper led to a Sunday work shift my senior year, and a full-time job after graduation. Although though the paper’s editorial workforce was majority white, I worked alongside many Black reporters, most of them University of Maryland journalism graduates. During this era, when the Baltimore Sun Company was privately owned by the Abell family, it was committed to building out a reporting force that mirrored the diversity of the city—which was 54.8 percent Black in 1980, and about 59 percent Black in 1990. The friendships I built over five years in that newsroom endure to this day—and I know that the diversity project was not just good for the city, it was joyful for me as a person. I should note that my friends did not complain to me about racist behavior toward them at college and on the job. Decades later, I was to hear some of these stories. Why didn’t they tell me then? I did not grow up marked as the descendent of slaves. I would not be able to understand, and how could I possible effect change?

My Hopkins graduation photo

Working at the paper made me feel like I was growing up. Another step toward maturity was joining a spiritual community. Going to a university built from a Quaker bequest made me want to learn more about the Religious Society of Friends, the faith community my parents had been active with during their years in England. At a Quaker Meeting House right across the street from Johns Hopkins University, I found silent worship thrilling, and the absence of a minister made me feel empowered to dig deep. As I learned about Quakers’ work for peace and social justice, I felt sure this was a group I wanted to stay connected with. Five years later, I visited a second Quaker meeting in Baltimore that felt even more of a haven, and I joined as a member. I’ve now been part of this meeting—as others might call a church—for twenty-three years. The essential tenet is that God’s presence is Light, and that Light exists in every human being. Everyone is part of the Divine, with no person closer to God than another.

Johns Hopkins was a birthright Quaker who became a member, and was later reduced to being an attender, of the Baltimore Monthly Meeting of Friends, the meeting in Baltimore that predated the two meetings I know. Which brings me back to the difficult information that’s been shared—that Johns Hopkins was never an abolitionist, as had been described previously by the University, based on a 1929 biography written by his great-niece, Helen Hopkins Thom. The fact was, he’d owned at least five slaves during his lifetime. This information was discovered by Johns Hopkins historians through old census records listing slaves, and then was fact checked and confirmed as true. The University immediately shared the information with its community and held a Town Hall a few days later that was open to the public, providing a place for people to express pain and ask more questions about the new information.

Did Helen Hopkins Thom repeat a story she accepted as true from an older relative, or did she have suspicions and want to lay them to rest? As a writer who researches history for my novel, I wonder if she accepted a story told to her from a contemporary of the times as truth. I know that I’ve done the same, when I was researching religious riots and the independence movement in 1940s Calcutta.

And then I wonder about whether anyone at the Hopkins Press felt they had to fact-check…or if anyone who read Ms. Thom’s manuscript might have known something was off about the story. Yes, Quaker abolitionists existed and had safe houses on the Underground Railroad–but they were considered a radical, dangerous minority by prosperous, big city Quakers.

Today, cynical minds (realists?) may think that Johns Hopkins gave away all his money at life’s end to buff up his image. Others might think he regretted the choices he’d made and sought to atone, by not only founding a university and hospital, but also an orphan home for children of color, and making sure his Black servants (no longer slaves) were well provided for in his will.

Johns Hopkins may remain an unknowable man, just as Baltimore can be both a Northern city, as well as part of the South. But I am here for the duration; and I give my commitment as an active alumna to Hopkins, just as I give my commitment to the city’s public schools, arts, library and the hungry.

The post The Unraveling Myth of Johns Hopkins appeared first on Sujata Massey.

December 17, 2020

When the Muse is Named Corona

This post originally appeared on .

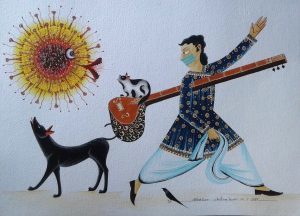

“Love in the Age of Covid,” Bhaskar Chitrakar, 2020

Once the pandemic is a memory, what image will you remember? The tired mask on a hook by the door, or it a dear friend’s face trapped behind an oxygen mask—a sight you’re only privy to because the shot was beamed into Facebook?

Coronavirus pictures have been dismal until the last week or so, when media published proof of health care workers in England getting vaccinations, and now Americans as well. As gratifying as these pictures of jubilant workers are, they are digital images with limited visibility. The next day, something else fills up the center spot on the newspaper’s home page.

And we must never forget.

The museums that recently re-opened have closed because the virus is surging. But art never sleeps; I suspect many of its makers are contemplating the coronavirus. And I’m certain that what these artists can eventually show us is different from mass perceptions.

Bhaskar Chitrakar with one of his creations

Bhaskar Chitrakar is a Kolkata artist in his early 40s who works in the Kalighat painting tradition that’s been identified with his city since the early 1800s. The painter’s surname, Chitrakar, literally means “illustrator,” and he’s the last descendent in a clan of painters who have trained father to son and grandson for generations.

The type of painting that this family and others made is an endangered art called Kalighat Patachitra. These small paintings, bought as souvenirs, were created inside a Kolkata neighborhood called Kalighat in honor of its temple celebrating the goddess Kali. The art form started with small-scale religious paintings were sold at low cost to ordinary people. As British dominance in Bengal increased, people chafed at the foreigners’ oppression and the pretentiousness of the expanding Bengali upper class who eagerly took jobs as English-speaking clerks and officials. Babu, the honorific suffix these gentlemen favored for themselves, became slang meaning a silly gentleman. Babus were mocked for wearing western men’s pumps in conjunction with the Indian dhoti, and for smoking hookahs, and making a nuisance of themselves. Babus, artists, and wealthy women became recurring protagonists in Kalighat Pachitra work.

19th century Kalighat art at the Victoria and Albert Museum

More of the V&A’s historic Kalighat Patachitra

Bhaskar Chitrakar was six when his father started to teach him painting. By thirteen, he was working full-time. While remaining respectful of the exquisitely detailed painting form, Bhaskar experimented with his own social commentary: strong women, jazz-loving cats, cell phones and taxis. To suit his his own sensibility, he continued to clothe his men and women in traditional 19th century garb—the sherwani jackets, draped dhotis, and flowing saris that light up up his paintings.

“Dance of the Coronavirus,” Bhaskar Chitrakar

Bhaskar Chitrakar’s art entered my life in the most quotidian way: a marketing email. The Khazana Gallery, a Minneapolis, Minnesota venue representing South Asian artists, created an online event called Tree of Life last July. This was an art sale designed to offer extra support to Khazana’s artists living isolated and unable to sell their work because of India’s long and strict national quarantine. The gallery decided not to charge its usual commission in order to give all the money raised from the art sale to the folk artists.

Feeling curious, I clicked into the gallery of available images. Not all of Chitrakar’s watercolors had a coronavirus theme, but I smiled the most at ones that did. “Love in the Time of Coronavirus” shows an elegant couple toasting each other from a six-foot distance, and “Have No Fear, I am Here” shows a smug, rounded corona molecule awaiting a syringe held by a flamboyant babu.

“Have No Fear, I am Here,” Bhaskar Chitrakar

I drew my husband Tony into the digital window shopping. When we choose a painting to admire or even buy, we usually see eye-to-eye.

“Leave Me Alone!” Bhaskar Chitrakar

This time was harder than usual, but we eventually chose the painting pictured above. A musician is wielding a musical instrument called a tanbura, all the while deftly balancing a cat on top of it and defiantly regarding the burning corona sun. He’s like all of us, balancing everything despite the difficulty of the situation. The man’s handsome coat is patterned with tiny corona images, and the coat’s tassel trim repeats the corona motif. I loved the grace of the musician’s movement, and the irony of his modern surgical mask against his fine clothing. Those masks made all of us look ridiculous. The picture is rounded out by a dog howling at the sun and a tiny crow. The three animals make me think of working parents with children underfoot.

After I’d placed my online order, the gallery emailed to alert me the picture we’d selected had already sold; yet Bhaskar was willing to recreate the same picture (he paints about eight works a month). I agreed, feeling glad that artists painting in a historic tradition are generous enough to recreate their visions by hand.

“Leave Me Alone!” departed India in early August and arrived in my home before that month’s end. I took it out straight away and admired it—along with six other works by different Indian artists. Art fever had infected me.

Yet despite my excitement over these purchases, I dragged my feet when it came to getting them framed. I didn’t feel especially safe going into the big box store where I usually got framing done. Working with a consultant to select the right frames and mats would take ages, and how many customers would be waiting ahead of me or breathing on the back of my neck?

In November, Covid-19 rates were rising, so I knew I had to get a move on before stores might close. I decided to try a small, socially distanced artist supply store in Towson, MD. I was the only customer at the framing desk, where a massive plexiglass shield protected staff and customers from each other. The process took about an hour, and I was glad that for three things: the framing consultant also liked the pictures, nobody got in line behind me, and I was putting some money into the pocket of a small business.

I collected my framed paintings today—just 24 hours after the first Pfizer vaccinations went into the arms of health care workers in my country. I had a place in mind on the living room wall, and when I hung the painting, it looked like it was home.

From where I sit, I can keep one eye on a blazing fire and the other on a mythical battle with an unnerving disease. In the distant future, I imagine a world that is healthier in some ways, and sicker in others.

In my imagination, a cute young child is running roughshod through my living room and clambers to stand up on an upholstered chair to better inspect “Leave Me Alone!” And then it’s time for me to answer:

Why is that funny guy’s mouth and nose covered up?

Khazana has revived its Tree of Life fundraising sale for the month of December, 2020. You can shop for available work from Bhaskar Chitrakar and four other folk artists working in India.

The post appeared first on Sujata Massey.

December 3, 2020

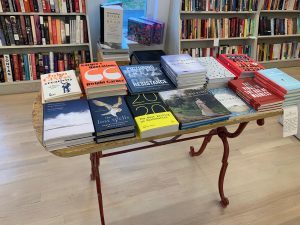

Holiday Novels for 2020

I’ve made a short list of recommended gift fiction that include some great historical and international novels.

Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia—In the 1950s, a Mexico City debutante travels visits a grand estate in the mountains and falls under a malevolent spell.

Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi—a young Ghanaian-American woman searches for religious and medical truths and family acceptance.

Murder in Old Bombay by Nev March—a mystery novel where an Anglo-Indian sleuth becomes involved with an elite Parsi family in 1890s Bombay.

Book of The Little Axe by Lauren Frances-Sharma—a historical novel set among generations of women in a family from Trinidad.

A Wish in the Dark by Christina Soontornvat—a fantasy novel recommended for readers aged 8-12 about a boy and girl who set out on a dangerous journey in a magical version of Thailand.

The post Holiday Novels for 2020 appeared first on Sujata Massey.

December 2, 2020

A Second Home

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

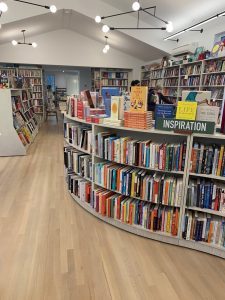

Have you ever frequented a bookstore so often it became a second home?

From the moment in childhood that my parents permitted me to walk to our neighborhood bookstore, I’ve engaged in this kind of squatting. From Micawber’s Books in St. Paul, to long-gone independents in Baltimore and Washington D.C., I’ve been an independent bookstore regular.

For the last eight years, I’ve been a homing pigeon to The Ivy Bookshop, just a few miles from my house in Baltimore. The Ivy Bookshop started in 2001 as a small, quite genteel general bookstore. I was happy to sign stock there, but there weren’t many public events. What a change the store underwent with its second owners, Ed and Ann Berlin. I met them when I returned to life in Baltimore after a brief exodus to the Midwest. I quickly learned this wonderful couple wanted excitement in the store and would do everything to make writers feel like family.

So I was no longer just sitting in a chair paging through books. It was a thrill to be part of a bookstore that aimed to make local and international writers feel welcome. The store newsletter kept me abreast of many creative activities ranging from writing workshops to book talks. The Berlins were so successful in building community that they opened Bird in Hand, a bookstore-coffee shop near Johns Hopkins, which was easily accessible to people without cars. This shop also succeeded, with a younger, diverse customer base, some of whom were mostly there for the coffee.

Ed and Ann saw retirement on the horizon but were adamant the store should not be left looking for its next buyer. That’s how bookstores often lose their footing. When Ed met Emma Snyder, the executive director of PEN-Faulkner Foundation, he learned the former Baltimorean dreamed of starting her own small business in Baltimore. He lured her in, and she became a a part owner in 2017. She became The Ivy’s sole proprietor in 2019.

I still visit with the Berlins, who live about a fifteen-minute walk from my house. Recently, Ed gifted me with what he created during retirement: ADRIFT, a memoir that’s full of art he’s collected and stories of his travels and adventures. The built the Ivy into what it was—and they continue to be an important couple in Baltimore’s cultural life.

Under Emma’s care, Bird in Hand and the Ivy Bookshop continued smoothly; but like Ed, she was always thinking ahead and trouble-shooting. Emma looked at independent bookstores around the country that had survived the expansions of Barnes & Noble and mail order behemoth that is Amazon. She deduced most secure bookstores were located in buildings they owned, so they were never subsequent to rent hikes and other problems related to tenancy.

The obvious question arose. Should the Ivy leave its tiny space in a well-known strip mall to build something larger and with more economic resilience? Would the Ivy’s customers, used to 18 years of bookshopping at a strip mall, go somewhere else?

A charming green Victorian for sale two blocks from the original Ivy Bookshop provided the answer. The former church had a high ceilinged, long and wide room perfect for browsing, plus plus multiple other rooms. The property came with almost three acres of well-groomed lawns studded by trees and shrubs—quite unusual for any bookstore. There was a meditation path, a vintage gazebo, and a vast sheltered outdoor patio. There appeared to be enough room to open a coffee shop within the store, and to even keep a small apartment for the use of writers in residence or traveling on a book-signing journey.

Emma bought the property and renovations were well underway when a virus began spreading around the world.

Not only did Coronavirus slow the new shop’s buildout, it made in person shopping at the existing old stores unsafe. The Ivy closed down for browsing entirely and pivoted to taking book orders online and having them fulfilled by drive-to-home and mail deliveries or curbside pickup.

During this time, the Bird in Hand bookstore became a drop-off point for a Baltimore city CSA farm to leave bags of produce for people, something I was grateful for. Even though customers couldn’t enter the store, the Ivy carefully set out tables holding the CSA food. They kept making coffee and serving pastries, but it was to patrons sitting outdoors at distanced tables. Online, both stores hosted online book talks to promote authors who were releasing books into a world where there were no longer in-person book signings.

Despite the pandemic, renovation did proceed to completion and in October, the Ivy re-opened, following city rules about social distancing and reduced capacity.

I went for a private browsing appointment this week and discovered a bright, roomy space that is a book-lover’s dream. During my recent visit, I saw a constant steam of solo booklovers coming to pick up book orders or browse with appointments (it’s open to limited capacity walk-ins after 2 each day). On my way out, I saw shoppers outdoors browsing in the covered patio.

It had been so long since I’ve shopped for anything except food or essential supplies. Passing by bookcases loaded with colorful titles, I felt my spirits rise. I left with four bags of books, knowing that I’ll be back many more times, and that in June, when my next book releases, I can have a garden book talk.

If you are not a person who often gives books as gifts, now is the perfect time to try it out. A small effort this month can make you part of a bookstore family’s happy ending.

Signed copies of Sujata’s books are always available by mail order from The Ivy Bookshop. She’s also holding a Zoom talk about The Sleeping Dictionary at 6:30 p.m. EST on Dec. 14, 2020. Send her an email with the subject line Sleeping Dictionary Book Talk if you’d like the link.

The post A Second Home appeared first on Sujata Massey.

November 19, 2020

Politics to Pastry: What Writers Share When They Blog

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

A novelist I greatly admire wrote her last blogpost in September. Catriona McPherson, formerly of the Femmes Fatales, declared that that with the election ahead, so much work needed to be done that she felt it useless to write about “cats and courgettes”—nor did she want to turn her blogposts into a political soapbox.

Catriona (pronounced Catrina) comes from Scotland and is one of the funniest mystery authors on the planet. She was writing with a wink, but the truth is, writers are constantly self-censoring. It occurs when we write novels—editing out lots to make them better—and when we offer up essays to the internet or print publications. We become known for one thing—and people expect us to be amusing. Typically, we keep dark, pressing worries and political opinions to ourselves.

During the months after Catriona quit blogging, her activism was substantial. She penned 240 personal handwritten letters and mailed them to voters all over the country in the Vote Forward movement, something I also participated in (with just 40 letters written). Currently, Catriona’s working on letters to voters in Georgia. All the while she did this, she launched a new novel, The Turning Tide, featuring her clever and charming Mitfordesque heroine, Dandy Gilver, who lives in 1930s Scotland.

I’m glad Catriona put her priorities the way she needed this fall. And we’ve got to credit today’s readers for their choices. Since the pandemic, reader choices are trending toward social activist and apocalyptic books. Although there’s nothing wrong with the historical novels we write, either!

You might be reading this particular blogpost because you follow Murder is Everywhere, a blog built by ten writers whose crime fiction set outside of the US. Or you’ve found my blogposts cross-posted to my website and Goodreads and my Amazon page. Some information you are learning about me—the protests I participate in for Black Lives Matter, women’s rights, post office service and voting inclusion—is probably not the reason you Googled me. Yet I am someone who writes about a female lawyer in 1920s India whose concerns are national emancipation and civil rights for women. What I care about is probably not a shock.

Writing about politics is most definitely allowed in Murder is Everywhere, and I learn a lot listening to the accounts of my fellow bloggers, especially when they draw cultural parallels with the past or in other countries. You must sample the words of my co-conspirators Annamaria Alfieri, Cara Black, Kwei Quartey, Caro Ramsey, Zoe Sharp, Jeff Sigler, Michael Stanley, and Susan Spann to get a taste of politics and pastry around the world.

I’m pleased that there are enough of us writing that I only need contribute every other week. Fourteen days are a lot of time for events to break and then recede and for my mood to change from outraged to mellow. I can almost guarantee I’ll be writing about holiday cooking within the next few weeks and post pictures of adorable dogs on the hunt for crumbs.

The cozy and the distressing, all part of the world we live in, and I thank you for being here.

The post Politics to Pastry: What Writers Share When They Blog appeared first on Sujata Massey.

November 4, 2020

What a Wednesday

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

In the early hours of Wednesday November 4, I am running on fumes and bittersweet chocolate.

I stayed awake much of Tuesday night, watching and waiting as the votes roll in for the 2020 presidential election. Where was the easy win for Biden that I expected?

I voted about a month ago, as an absentee, which in Maryland meant that I filled out a ballot the Board of Elections mailed to my home. I then carried it to a locked ballot box placed outside one of my favorite places, the Baltimore Museum of Art. Two days later, I got an email saying my ballot was received, and a few weeks after that I was notified that my vote had been counted.

My situation was pretty ideal, and I appreciate Maryland’s decision to start counting absentee ballots as they arrive, rather than waiting to open the envelopes on election night, as is happening in Pennsylvania. In Pennsylvania and other swing states, the mail has been markedly slow, and many people didn’t get absentee ballots in time, and don’t have an assurance that their board of elections has their ballot to count.

The waiting game is not new for me. As a writer, I must have patience with myself to make it through the process of writing a book… and then seeing the publisher bring it to the bookshelf. As a mother who adopted two children internationally, I had long waits that were filled with longing and worry for the babies who could not join me right away.

Currently, I am waiting for a vaccination against the coronavirus that might be on the market by springtime… or some other time.

56 years of waiting have revealed that obsessing about the worst, while waiting, doesn’t change the outcome—or the way I feel, once destiny is revealed.

What I did today, to get through the wait for election results, I spent my day going through a copy edited manuscript, doing some light cooking. Almost all day I live-streamed rousing alternative rock and funk from my favorite radio station, the Current, based in Minneapolis. I don’t usually fill my day with live radio, but this time I welcomed the distracting beat.

I kept walking my dogs. After lunch, I drove over to the polling station at Barclay Elementary School and smiled to see a line of people almost as long as the block. Someone was playing music on their phone, and there was a festive sound to people’s conversations. I drove to another larger polling place, where there was no line, making me think the staffing and organization was efficient, or more voters in that area had filed absentee ballots.

When you work as a campaign volunteer—as I have in the prior three presidential elections—you get a small, personal snapshot of what’s going on. It usually feels very optimistic, and I am good at talking myself into thinking the rest of the country is like the people I’m talking to.

But at the moment, my spirit is stressed. I suspect I’ll be at a “Count Every Vote” demonstration on the street later today. I voted for Biden-Harris, for many reasons, including Trump’s reckless endangerment of people’s lives by not mounting a serious pandemic response. I thought that the rising death toll in red states would have meant something to the people living there.

Still, nothing is set. Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania will take days to count votes. And it would be good if all votes from overseas citizens arrive by mail to be counted… and our mail is running slow.

I have to remind myself that a few extra days, or even a week, is nothing compared to the distress of the last four years, when environmental regulation collapsed, and jobs and lives were lost for no good reason.

And this is why waiting does not mean giving up.

The post What a Wednesday appeared first on Sujata Massey.