Sujata Massey's Blog, page 3

September 25, 2024

Writing a Series: Part 2

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

My family settled in Minnesota when I was seven. You’d think the Laura Ingalls Wilder books set in the prairies around the state would be the perfect fit for a book-loving, history fanatic. I liked them because they were set in the past, but I was obsessed with books that were both set in the past and in Britain.

England, the land of my birth where I spent my first five years eating Smarties, going to Infants School, and hearing grownups grumble about Mrs. Thatcher. Then suddenly we moved stateside, first to California, then to Pennsylvania, and finally Minnesota. Life was becoming confusing and frightening, and I felt like an outsider. My parents had emigrated for a number of great reasons, but I wasn’t fitting. It was all to easy to build up the lost home in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne as superior to my everyday existence in snowy St. Paul. How grateful I was to escape to elegant London streets and wild Yorkshire moors in books by Noel Streatfield, Joan Aiken, Nina Bawden, and many more!

I kept up the reading habit, and gradually, my terrain grew. I came to take special pleasure in settings I don’t know at all, like the Singapore of Ovida Yu, the New York City Chinatown of S.J. Rozan, the Bangalore of Harini Nagendra. I got to India for the first time when I was nine, shown above at Golconda Fort—and my mind was now alight to read books about India. I like Elin Hilderbrand’s Nantucket and Alafair Burke’s Long Island. Interestingly enough, as a grown person, I’m eager to read books set in Minnesota.

When I decided to try writing a first novel, I was living in Japan: an hour south of Tokyo, is how I like to describe it, kind of the way people in New Jersey talk about their relationship to New York. Tony and I rented a typical middle-class house without central heat, but with some very interesting traditional features, like a cut out space in the floor meant for fermenting foods; a very hot bath; and tatami matted floors that required you to sleep on a futon and have no furniture with legs. Shoji screens and a lower-level entry area were other features to which I became accustomed and wove into my fictional setting. But I wasn’t home much.

Every day of the two years I lived in Japan felt like adventure. There I was, riding trains with a frieze of funny advertisements in every compartment. I walked streets that smelled of roasting sweet potatoes and mixed towering skyscrapers with tiny old shrines. Chic young ladies with Chanel bags hurried to their office jobs, passing tiny old men bicycling to the temple. Setting was easy to draw when you saw it coming to life in front of you.

When I came home two years later, the memories were rich enough for me to finish the book and write ten more after it. But it wasn’t as easy as in the beginning. I had to keep returning to Japan in order to refill my imagination tank, and I couldn’t afford to do it both financially and because of my responsibilities co-parenting two very young children.

My second series was supposed to be easier for me to manage, yet I set it even farther away, in India. What the hell was I doing?

I had been to India several times in company of my Indian father, but I’d never been a resident settled into a home and neighborhood. Yet I had so many Indian family resources—my friends, my parents and step-parents, and their generously welcoming families still living in India. So I took four years to learn more about India, including studying Hindi and reading a lot; dancing and cooking with my friends was part of it, too. With our children growing up and liking travel, it became easier to make return visits to India, sometimes with family members in tow.

In hindsight, I think I chose to set both my mystery series abroad because that’s the way my imagination comes alive. But it’s not an essential rule for everyone. People may love their homes and be able to explain them better than anyone else. The one wise thing I think a series writer should do is dive deep into one geographic setting, whether a region, town, or neighborhood. Readers do get attached—and the writer gets certain benefits.

The first is a buildup of intellectual capital. If you’ve dragged yourself through one novel, you have done lots of investigations of street names, buildings, and have put characters into cafes and police stations and homes. You will probably write even more richly about these places the second time around—because now you know them.

And that brings up the point; should a series setting be an actual village, town, or city—or is it wise to fictionalize? Do you want to write about a fictional in rural Canada or the actual U.S. city of Chicago?

A lot of writers feel emotionally more free and creative writing about a fictitious place. Obviously, there’s less of a chance of some person thinking they are being described in your novel, or you making an accidental geographic or historical error. However, if Whispering Woods (your fictional village) is entirely being built from your imagination, you probably have to work harder for story ideas, because all of it will be self-generated.

If I choose to write about Chicago, I can send characters into well-known ethnic neighborhoods, watching a basketball game at Northwestern, and eating Latin pastries at an up-and-coming restaurant in River North. Readers will love this! And ideas for plots involving the setting’s key features will bubble like seltzer from the tap.

Brilliant Laura Lippman writes books set in Baltimore and other real towns in Maryland. Laura’s said that if an actual Baltimore restaurant is good, she will mention it by name if it seems like a good place to put in a book. Yet she wouldn’t put in a real restaurant that isn’t so good and talk trash about it. Below is a hotel restaurant in India that looks like an old-fashioned Irani place in Bombay, but is actually in Fort Cochin, Kerala.

I mixed reality and fantasy in my work by using actual restaurant’s name for a fictional restaurant in The Widows of Malabar Hill, my first Perveen Mistry novel. I decided to use Yazdani’s name on a very good, fictional café of my choice on Bruce Street (now renamed Homi Modi Lane). The real Yazdani’s Bakery and Cafe lies about a block away from Homi Modi Lane. It is an adorable corner store bought by an Irani family in the 1940s, not the 1920s of my book’s setting. Still, Yazdani’s the oldest Irani café in the area with an amazingly charming elderly owner, and I imagine my readers going in might wonder if the white-haired, voluble elderly owner once was the 30-something friendly and undeniably macho restaurateur, Firoze, in my book.

There are so many challenges of trying to recreate cities as they were a hundred years ago. It can never be done perfectly; and in my case, nobody’s still living who could make that judgment.

I’ve found Mumbai and Kolkata to be goldmines of gorgeous atmosphere that I can learn about through literature, maps, photography, and best of all, in person. I’m working on a train journey for my character, and while I remember a long train journey as a child in India, I’m taking a 5-night trip in Karnataka early next year in a historically furnished train as a way to understand the experience.

Of course, there are those who have sold a lot of books set in countries where they haven’t visited. The late H.R.F. Keating, who lived in Britain, depicted India in his novels, based on his own encounters with Indian people in England, and on his reading. John LeCarre traveled to a lot of countries in his lifetime—but he didn’t go to Panama for The Tailor of Panama and perhaps some other books. LeCarre was aging and at the top of bestseller lists, but instead of traveling to Panama, he sent a researcher. Now, I liked this book—but I imagine it would have been even better if he’d laid his own eyes on the place. When a writer regards a location thinking ‘a city or country is sooo like this’ it means they are working from other writers’ opinions. That puts the writer at risk for trafficking in cliches and ethnic stereotypes—the problem with H.R.F. Keating. He eventually started a second series with a British protagonist. Yet his affection for his first character never ended and resulted in just a few more Inspector Ghote books.

H.R.F. Keating truly loved his characters and milieu. But he was living in a fictional India, because he wrote dozens of books without visiting. He finally traveled only because Air India sent him a free ticket, and his first words upon landing were about his shock at the heat. One hears that India is hot, but there’s a Dry-New-Delhi-in-July hot that’s different from Humid-Kerala-in-February hot. He was feeling that, for the first time.

And physical sensation brings a final question: how comfortable are you in it? It may seem gripping to readers for you to write about a very tough city and give your protagonist a shabby apartment on its meanest street. But if you don’t love a setting and feel comfortable staying there, it could be hard to sustain a series there. Another option is for your protagonist to be a traveler, a Jack Reacher or James Bond type, and have constant changing scenery and people. The reader experiences settings from the eye of a protagonist who doesn’t know it well…which can be an ongoing theme.

I write about Mumbai (named Bombay before independence) because I truly enjoy the people I know in the city. I have real friends here, built up over years of visiting and research. They always tell me the next place to go. I have a fondness and familiarity with a few buildings and neighborhoods that enriches my imagination. I’m writing about an era roughly 100 years ago, another reason I chose this place versus another city in India. Mumbai’s preservation laws will keep the façade of the central train station and its windows the same as before, which is crucial if I want to describe things accurately.

Finally, I feel a level of physical freedom and safety working in Mumbai that’s the same as in my home. I’m glad to come back there, in my books and in person. Traveling so regularly to India is a financial expense that eats up a lot of my book advance.

It’s ironic that the England I thought was perfect heaven in my childhood days now is an antagonistic idea to heroine of my series. How times change! And sometimes I think, maybe one day I will get away from the travels and write a book or even a series set in my neighborhood. But I suspect that I’m hard-wired to venture outside of the familiar, because I’m on the same journey that many readers are.

The post Writing a Series: Part 2 appeared first on Sujata Massey.

September 11, 2024

Writing a Series: Part 1

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

What does it take to bring an idea into book form—and then to take one book into a series?

My first mystery came out in 1997, and it turned into a series that lasted for eleven books. Then I went on to throw myself into a second series that I’m still writing. Doing a series is not only a writing choice; it’s also a commitment to community, both real and fictional.

On the outset, the idea of a series is simple: a sequence of novels with the same protagonist. Yet there are some great permutations. The books could be spearheaded by a succession of linked protagonists, such as the women lawyers in Lisa Scottoline’s Philadelphia series, or the various detectives we meet in Tana French’s police procedurals set in Dublin. In romance series like Bridgerton, a family of brothers and sisters take turns getting romantic fulfillment.

Series are popular because of readers’ deep desires to stay connected with characters they care about. Some critics say the business of writing a series is to essentially replicate the same reading experience for the readers each time—albeit with a novel plot and new supporting characters.

For me, the ‘why’ of a book series is greater than a career formula. It’s truly comforting to me to write novels that revisit the same houses and restaurants with characters that became my friends. I have so many thoughts about what makes series writing wonderful. Therefore, I’m going to make this a two-part blog post. Imagine we are having a cup of tea together and talking writing. You see—you are already a character in my series.

How it All Started

Picture me at age 27, entering the 1990s as a young bride who had left what seemed like the greatest job ever at a daily newspaper. I didn’t want to stop writing—but I had a massive geographic move from Baltimore to Yokohama-area Japan, and my writing job opportunities were limited. So why not try writing fiction? The only other writing job I’d heard about was correspondence secretary for the Officers Wives Club!

I sat in my chilly house with gloved hands in front of a brand new PC, feeling liberated and optimistic. I had no illusions of writing a publishable book. The goal was experiencing what it felt like to write long fiction. I told myself writing time in Japan would be a step in a long climb. Yet that first book I dreamed up became the ‘first in series’ of the Rei Shimura books. I really didn’t know what I was doing; but somehow, it worked.

That first protagonist I created, Rei Shimura, was a Japanese-American English teacher living in modern Tokyo. The position of being a foreign language teacher in Japan is a culturally iconic one that has lots of room for adventure. I myself worked part-time as an English teacher in Japan, not earning much money but gaining so much in terms of cultural connection, whether I was working with high schoolers, military service members or elderly people. Important memo: the more you know about the job your protagonist does, the more interesting and realistic your character will be.

Yet for a teacher-character to continue being innocently drawn into suspicious deaths, year after year, doesn’t feel true to life. I hadn’t thought about this fact when I started, because I expected I was writing a standalone novel. Now I had to twirl creativity and logic at the start of each new book to find a plausible reason for Rei’s abilities and involvement to surpass the Japanese police.

As the series progressed, I became quite annoyed with the recurring problem. Ultimately, I had a spy agency recruit Rei, so she is forthrightly directed into covert investigation—and she has a prickly relationship with her agency supervisor, too. And what a hot relationship that would violate every HR guideline, but of course, this was a magical, fictional world!

In the Rei Shimura series lifespan, the books went through three publishers: HarperCollins, followed by Severn House, and then myself. Perhaps it was because I wanted flexibility in the future that I never have outrightly declared the series is over. I feel terrible disappointing people who have invested years and money in the series. Not only are they buying books for themselves, they are gifting them to others and advocating for the books’ presence in the library system. Dear readers have not only written to me personally, they have nominated me for speaking gigs and awards—unexpected privileges and joys.

I actually was trying to wind things up, yet I still loved the series. Breakups are hard for writers and their characters. Ten books sounded like a complete number of Rei books, but I felt compelled toward writing just one more book.

The last series book, The Kizuna Coast, had Rei investigate a disappearance in the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Once the mystery resolved, we see Rei boarding a train from Tohoku toward Tokyo. Feelings are upbeat, and I hint that she might be entering a new stage in life. And I think that’s the positive feeling that helps a series end, whether or not it’s planned out.

After The Kizuna Coast, I took a deep breath. I wanted a break from the treadmill of a book a year. Self-publishing worked, but it was a lot of extra jobs for someone who wasn’t a trained web designer, marketer or publicist. A traditional publisher was interested, but I didn’t want a multi-book contract. I became a free agent and decided to pause.

My Palate-Cleanser Book

I had a nagging sense that it was time to write about India, the place that was so central to my family history. I’d been spending more time in India as an adult than in childhood. In quite interesting ways, I was getting to spend time and learn from the families of my father, my stepmother, and my stepfather. An idea drifted my way, probably because I wasn’t pushing hard to think something up. And what also was clear is I wanted to take a break from mystery. I wanted to try something I loved reading, but wasn’t sure I could pull off: a historical novel.

This straightforward wish evolved into four restless years of writing and rewriting a standalone novel about a young Bengali woman coming of age in 1930’s and ’40s India. The Sleeping Dictionary was a book that transported me—not just because of the setting, but because of the wealth of details that true history provided. Unsurprisingly, the characters grew on me in the four years that I took to write and revise the book. As it was being readied for publication, I daydreamed about making it a series. Yet as I pondered the type of follow-up this book should have, the answer was a very sober story. I knew what difficult political events marked 1950’s, ’60s and ’70s Bengal. I feared becoming emotionally depressed if I wrote about matters like the kidnapping of women post-partition and the war for Bangladesh’s independence.

This is why I ultimately decided that The Sleeping Dictionary would stay a standalone. At the same time, I realized how much I wanted to write series fiction again. The emotional ride in such books is more predictable and satisfying for me. In my approach to series mystery, the unrest and crime is on a smaller scale—and it’s fictional. Order is always solved by page 400, and the protagonist has time to recoup before the next book.

The Next Series

Second time around with series writing, I vowed to remember as many of the things I struggled with for the Rei Shimura books. My goal was to follow a route that had fewer pitfalls—and to write about a setting that had lots of story ideas.

Firstly, I was intent on giving my new sleuth a natural reason to repeatedly encounter crime and suspicious death. No women were allowed into the police until the 1970s in India, so she couldn’t be a cop. However, my years of research in 19th and 20th century India meant I had a big file cabinet, and a specific file that included the names and biographies of two early women lawyers working in British Raj India. I knew I could give my fictional heroine such a real job without bending reality. Still, writing about a female lawyer would be challenging since I was not a law school graduate—and you know how I feel about writing ‘what you know.’ I began looking for people who had studied law willing to answer my questions about the likelihood of a judge doing this, or that.

I also pored over law books published during the British Raj to make sure I had facts rights about laws about crime and punishment, inheritance, and marriage and divorce. I made my heroine a Zoroastrian because the early women lawyers of India were more likely to come from this faith community than others.

I read up a storm to get an interesting and realistic legal dilemma for The Widows of Malabar Hill. And then I returned to the facts surrounding Perveen Mistry, my lady lawyer. A young woman in her twenties is of marriageable age—especially in a country like India. But would a woman be able to practice law actively while married? Given the social constraints of the time, and the likelihood that a female sleuth’s husband could restrict her activities, I decided to make her the equivalent of a spinster; yet with a unique status that would keep her from being able to marry anyone intriguing she met within the series. And this itself became an interesting plot point.

There’s another, often subconscious, decision about protagonist power that writers make. I argue that you can roughly divide the sleuthing protagonists in two categories: superheroes, and ordinary, flawed people. The characters Sherlock Holmes and Jack Reacher are examples of the superheroes, though fans would probably argue they have flaws that make them interestingly human.

Rei, my first protagonist, was an accidental sleuth from the start and she escaped dangerous moments using different forms of soft power. Perveen is closer to a superhero; while she’s not physically powerful, she has extreme courage and social skill that comes from always having to fight for her ability to work and go about in public.

There are so many women I consider superheroes in my daily life in America and also in India. Among the Indian stars are women who have been the first: the first to finish high school in the village, the first to perform surgery at the hospital, the first to drive a taxi. More heroes: the middle-class housewives who make sure the poor kids living in shanties nearby get homework help and schoolbooks; and who don’t hesitate to find a doctor and pay the medical bills for a servant’s wife who needs surgery. These women change and often save lives.

Remembering all this beautiful strength helped me pull my ideas together. After a few months of deliberation and exploratory writing, the characteristics of my series heroine had fallen into place. Miss Perveen Mistry, Solicitor at Law, had both a personal status and practical job for a permanent series position. Yet even more decisions need to be made to build Perveen a successful series to return to, book after book. More about these ideas in the next post.

The post Writing a Series: Part 1 appeared first on Sujata Massey.

August 29, 2024

The Sweetness of Figs

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Fall is almost here, but nature is having a last hurrah. In Maryland and the states nearby, farmstands are loaded with corn and tomatoes. Peaches are ripe and a second harvest of raspberries looms. For me, the fruit that’s calling out the loudest is the simple brown fig.

Figs are said to have originated in Asia Minor, an area in Turkey’s north: a meeting place for European and Asian travelers. The fruit can be grown from a cut twig—so it was easy to propagate and spread worldwide. In Baltimore, Maryland, many Italian and Greek immigrants planted fig trees on the small patches of land outside their rowhouses and cottages. As their trees grew, they shared branches with neighbors.

This practice even continues today. On Deepdene Avenue, a small street filled with small Victorian cottages, my neighbors Prem and Anand admired a robust fig tree across the street. Their neighbor gave them a cutting. Ten years later, their own handsome fig tree towers over the roses and vegetables growing in their back yard. Hundreds of figs are produced each year: more than enough for them and the local birds. This meant that yesterday, Prem and Anand walked Deepdene with bags of figs that they dropped to ten households. They’ve made me and other friends feel welcome to come and pick figs when I want.

The average fig tree takes three to five years to start bearing fruit; and some can live as long as 200 years. In the novel by Eli Shafak, The Island of Missing Trees a beautifully sheltering fig tree is one of the story’s narrators. She is a cutting transported from Cyprus to England, where she is planted and tended by an immigrant family who holds pain of the past.

Very likely the brown Turkey fig came to India via traders or during the Mughal Empire, because you can find sweets and chutneys made from the fruit in India. However, South Asia has its own indigenous fig tree: the mighty and mystical banyan. A bright red-pink variety of figs grows in thick clusters on banyan trees (Ficus Benghalensus) that are enjoyed by birds, not humans.

The fig tree that’s now native to my neighborhood is the aforementioned brown Turkey fig, a fruit that does not require wasp pollination. Thus, these are considered “vegetarian” figs as opposed to “carnivorous” figs like Smyrna and San Pedro that have the remnants of dead wasps inside. But don’t be frightened! The insects have been almost absorbed by enzymes and are both invisible and don’t affect taste.

What to do with an over-abundance of figs? Prem freezes her figs in plastic bags and uses later for baking. Here we are together, and a closeup of Prem’s famous fig cake.

In the past I’ve frozen several small fig-almond meal cakes, and they’ve defrosted nicely. This year, I decided I wanted to make fig chutneys. It’s simple enough to wash the figs and chuck them into a pot with a small amount of onion, ginger, sugar, vinegar and spices. What emerged tasted a lot like a classic sweet mango chutney.

Two days later, Prem had more figs for me. I altered the recipe slightly to be more like hers: including half of a tart Granny Smith apple. The result was a different texture and the sweetness was cut very slightly. Either chutney is delicious on a cheese sandwich or a charcuterie board, if you’re not using it alongside grilled meat or on a plate alongside curries, rice and dal. Small amounts of chutney can be used in marinades, glazes, and dishes like chicken salad. Chutney freezes well and makes a meal taste like early Fall sweetness, no matter the time of year.

Fig Chutney (makes approximately 2 cups)

1 ½ tablespoons neutral oil such as avocado, sunflower or canola

½ tsp cumin seeds

¼ tsp fennel seeds

¼ tsp mustard seeds (yellow or brown)

½ cup finely chopped red onion or shallots

1 tablespoon grated or finely chopped gingerroot

Approximately 25 figs, washed, stemmed and cut in half

½ teaspoon garam masala powder (homemade is great, and I like the brands Frontier and Spicewalla)

¼-½ teaspoon red chili flakes*

¾ teaspoon fine salt

3 tablespoons brown sugar (I use coconut sugar or jaggery, Indian unrefined cane sugar)

½ tablespoon vinegar (apple cider, sherry or wine vinegar, or plain all work fine)

½ cup water

*Chili flakes can be omitted entirely or substituted with other items you may have on hand. Try a chopped fresh red chili, a whole dried red chili, chili crisp, or cayenne powder. In every case, start with a small amount and taste the chutney in the last 5 minutes of cooking time to see if you want to add more of a kick.

Fig-Apple Chutney Variation: To the recipe listed above, add one half-cup of small-diced Granny Smith apple, or another tart cooking apple. You can cut the figs to 20—or even less. Do as you like, because chutney is most forgiving.

Here are pictures of the chutney as it starts out in the pot, followed by chutney that is ready for bottling.

The post The Sweetness of Figs appeared first on Sujata Massey.

August 7, 2024

Attention, Voters! A Letter from Perveen Mistry

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

(Ed. note: Perveen Mistry, a female lawyer living in 1920’s Bombay, has reached across time and reality to write a frank letter to 2024 voters. As the chronicler of Perveen’s legal mysteries, I’m impressed by her forthright investigations of political issues and modern technology. Let us enjoy her ramblings and perhaps find a few kernels of timeless wisdom.)

To My Dearest Readers Abroad:

I send very best greetings from Bombay, where we are deluged by the rainy season, and I spend much time trapped inside my family home in Dadar Parsi Colony. If the newsboy can get through the flooded streets, he delivers a paper that is the highlight of my day. So, imagine my surprise when, instead of handing me the August 4, 1924, Sunday edition of Times of India, he brought me a bundle of Sunday newspapers titled The New York Times dating from August 4, 2024, as well as the previous weekend in July!

What kind of magic brought these epistles from a remote land and time? At first, I worried that the experience meant that I am suffering insanity. I’ve come to think I’m part of a very complicated, literary dream that has allowed me hours of excitement. Because of the similarities between me and Miss Kamala Harris, clearly only I could be the architect of this fantasy. But there remains a possibility that these engaging tabloids are an authentic portent—and that is why I am writing an open letter to the dear citizens of the United States in future times.

Could it be true that an election for the presidency of your country is 92 days hence? If so, the papers are saying that female voters are anticipated to be very active. In my day, very few women are allowed to vote in elections—it happened just recently in Bombay that ladies owing property and suitable income can vote in elections. Thus, my mother has a voting right, because her name appears alongside my father’s on the household deed. That privilege is not mine yet, I am a supporter of universal suffrage regardless of gender and income; I’ve enclosed a picture of Indian suffragists in London in 1911, fighting to say this.

Being unable to vote is a great frustration for me; although I must say the candidates who have come up in the Bombay for the city legislative spots are rather dull. The powerful rulers—the viceroy in charge of governing British India, and the governor of my own Bombay Presidency—are hand-picked by Britain’s prime minister; it has nothing to do with their popularity in India. Within the last few years, though, Indians have the right to run for seats in the central legislative, the council of state, and provincial assemblies. And this is a good start.

I tell myself that I can support forward-thinking politics in Bombay by attending meetings to hear these candidates. Chiefly, I’ve made donations of my own hard-earned money and inheritance to the candidates who are brave enough to speak up for dominion status or any sort of freedom from colonial rule. Take note of a treasured photograph of the esteemed Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in a peaceful procession with his supporters.

Even with my limited political experience, I beg to offer a few words to faraway citizen living in the strange new world your newspapers illustrated.

My first recommendation is to be cognizant of your own ability to cast a vote. If you voted without incident four years ago, things are likely fine; but many such voters receive a notice by mail, reminding them that they will receive a postal ballot by mail or should vote in person. If citizens have moved out of station, or only recently registered to vote, it’s prudent to check that your papers are in order to enable voting. College students who will be away from their native place in November especially need to ensure their ability to vote.

My second point is financial. It is quite common to receive solicitation for donation from various candidates and political parties. Yet we must keep an eye out for unscrupulous organizations that abuse presidential candidates’ names for their own purposes. (Ed note: I recently received a text promising to match any credit card donation to the Harris campaign by 400 percent. Highly dubious!)

Ahem—let’s return to business, shall we? My heartfelt plea is to give to others running for office: the many good people running to take places as senators and congressional representatives. These people aren’t so much in the news, and they receive scant funds in comparison to presidential candidates. Yet they are crucial, for how could a president suggest societal improvements be put into law without having a solid base of elected members of Congress to pass such laws? Please do the needful and support them!

Another of my pleas is to put pen to paper. A good letter can brighten a day and inspire a person to action. Why not send personal cards to people around the country urging them to vote in this election? There are postcard-writing parties throughout America—and I can attest that it’s a practical use of time to write letters from home during inclement weather.

Now, might I address larger types of gatherings? Here in India, large political assemblies in public are often prohibited by the government on the basis that they incite sedition. How fortunate you are to be able to dance and cheer in university stadiums for the sake of politics! I also learned that modern Americans may view films of such gatherings from their own houses, which sounds most amusing. Another curiosity I read about is something called a Zoom meeting for fundraising and political encouragement. Apparently, news spread from person to person, and audiences of thousands come together to witness the meeting whilst actually remaining in their various homes.

The Zoom business is incomprehensible, but I can discuss what it means to do political work outside the home. Motivated individuals may enroll to assist on the important day either as an elections judge or nonpartisan election observer. If people wish to campaign to the very end, they can drive to swing states to distribute materials and even help people who need transportation to polling places.

What choices you have! But this idea of “choice” is something that you will surely lose, should a small group of conservatives take control of your diverse and impressive nation. These men have publicly stated their desires to implement strict laws about childbearing and other personal behavior, and to dismantle education and censor libraries and the press. Believe it when I say your society will suffer under such laws—that’s how it is in my time.

Yours sincerely,

Perveen Mistry (Miss)

Partner, Mistry Law

Mistry House, 10 Bruce Street,

Fort, Bombay.

The post Attention, Voters! A Letter from Perveen Mistry appeared first on Sujata Massey.

July 24, 2024

A Pause Between Woods and Water

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

It’s just after six in the morning, and I’m sitting outside with my coffee watching a morning mist flowing across the top of Lake Kawaguesaga.

It seems like a spectacular illusion straight out of a movie’s computer animation department. But this is real, and I am here, spending a wonderful week in the cool misty climate of Northern Wisconsin. I’m fortunate to be staying with family members and even my dog, Daisy, with my friend Marcia Tingey at her longtime summer home—a place she and her husband built out of the ruins of a 1920s fishing camp house on a small island that they bought, part and parcel, and carefully brought back to habitable life. If this story sounds like it should be a summer beach book—perhaps the Wisconsin version of Under The Tuscan Sun—I agree.

Marcia owns Fiefied Island in Lake Kawaguesaga, one of the five lakes in a scenic chain named Minocqua that are about 26 miles north of Rhinelander. The town and lake chain’s name were possibly inspired the name of a Chippewa band chief, Noc Wib, who headed the community through the 1880s. In the 1860s, U.S. government surveyors had found the lovely area, noting its lakes and beautiful old-growth forests. Chippewa people were first discovered in the area in the 1860s, when government surveyors came and saw the magnificent chain of 5 lakes, and the beautiful old-growth wood forests. Naturally, the government could not walk away from this bonanza.

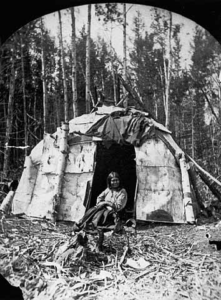

Chippewa woman, late 19th century

Chippewa woman, late 19th centuryBy the 1880s, the Indians were pushed out of the Minocqua region to the existing Flambeau reservation. And the lovely land became both a source of lumber and a haven for summer tourists, many of whom came on the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway line built in the 1880s. The original, late 1800s downtown was burned in a 1912 fire and then rebuilt for generations of tourists to come. At one time, there were hundreds of summer homes and resorts dotting the shores of the five lakes in the Minocqua chain. Today it’s still touristed, but in a low key way, with the downtown of Minocqua comprising about three blocks of souvenir shops. From a dock near downtown, Marcia can pontoon herself 8 minutes to her island home.

The island has stayed natural, with no other housing than the Tingey place, and no pavement or way of moving about except by on foot. This makes it very possible to imagine Minocqua back in the times of the Chippewa people. Pine, birch, maple, balsam and hemlock trees rise high and happy. The spongy, sandy earth is carpeted with ferns, moss and mysterious mushrooms of varying hues.

Marcia’s late husband, Jim Tingey, carved fantastical sculptures out of island wood. Jim’s mysterious beings and mushrooms are sited all over the island, along with wooden chairs placed in ideal spots for meditation and contemplation of scenery. I felt the long ago indigenous presence on the island. It’s a very special, spiritual place.

A few bald eagles live on the island; I was lucky enough to see a juvenile touch down on the path in front of me, although little Daisy regrettably barked, and the magnificent raptor flapped its wings and exited. Does nurse their fawns here before the young deer are strong enough to swim alongside their mothers to the mainland. As far as other animals go, mice, chipmunks and raccoons are present. Bears also swim. Marcia spotted a brown bear on the island four years ago, but she thinks the bear was on a walkabout and not at home. Loons have long bred and relaxed on the island’s marshy side. The waterfowl are currently absent because their protective platform broke in a storm. Marcia plans to have it rebuilt so the gorgeous waterfowl will return to their sanctuary.

My days here have been spent walking narrow trails, looking through the tall pines at the shatteringly blue and tranquil lake Kawaguesaga, whose silence is occasionally cut by jet skis power boats. But for long spells, one can sit in utter peace.

Recently I’ve longed to be more mindful: chiefly, noting what’s around me and what sensations I’m feeling. It’s been challenging for me to slow my mind and not jump off to different places. While staying here, it hit me that the practice of fiction is entirely about being in another imaginary place. Telling stories set in another time and place only escalates being inattentive to the present. It’s necessary—but it takes a toll on the writer.

Lying on the house’s deck, which was thoughtfully built to include the pre-existing tall pine growing there, I feel different. My eyes go straight up into the heart of the tree’s gorgeous crown. Or I’m sitting on the deck, watching the water’s natural slow current. After I’ve admired the lake, my eyes travel across the water to a pulsating movement in the air in front of some faraway trees. Are they a flock of thousands of insects, or hundreds of small birds? What is going on with so much energy in one place? Even Daisy, who never goes off leash, threw herself into new freedom and speed as Marcia’s dog, Blondie, showed her the way.

And that is the truth about being stuck in the woods for a week. It seems like nothing’s going on, yet the reality is you aren’t alone. Everything is alive and in some kind of growth or motion. This is the world that matters more than the noise.

The post A Pause Between Woods and Water appeared first on Sujata Massey.

July 10, 2024

Indira Gandhi, the Iron Lady

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

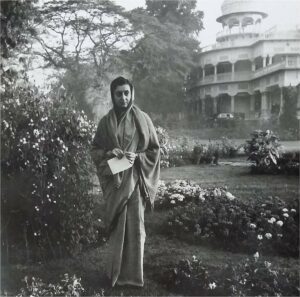

Indira Nehru Gandhi at her ancestral home

Indira Nehru Gandhi at her ancestral homeCan a woman become a successful president?

The mission was attempted just once before in the United States, with Hillary Clinton at the top of the Democratic ticket. Although Hillary won the popular vote, she didn’t win enough electoral college votes and ultimately lost the election to Donald Trump. The question simmers again in this ungodly hot summer, eight years later: could a female politician such as Gretchen Whitmer or Kamala Harris make it to the top?

An estimated 81countries, large and small, have been governed by women leaders. Even places where women’s rights are considered worse than the United States; for example, India, which elected and re-elected one of the world’s most successful and controversial female prime ministers: Indira Gandhi. Indira’s astonishing rise to power in late 1950s India lasted through 1984, and reveals how women can unexpectedly succeed in government.

Indira during adolescence

Indira during adolescenceIndira Priyadarshini Nehru was born in 1917 in Allahabad, the capitol of Uttar Pradesh, an important province in Northern India. She was the only child of Jawaharlal Nehru, a famous leader in the freedom movement, especially in the 1930s and 40s. Indira’s mother, Kamala Kaul Nehru, was chosen as Jawaharlal’s bride by his father, Motilal, a wealthy lawyer who served as president of the Congress Party for several terms. The family was close to Mohandas Gandhi, also called Gandhiji within India and Mahatma Gandhi to his growing international audience.

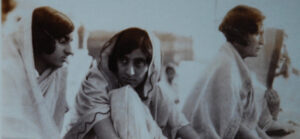

Political protest times in the 1930s

Political protest times in the 1930sBoth Jawaharlal and Kamala Nehru threw themselves into activism, participating in protests that were violently countered by the police. They were often imprisoned during Indira’s childhood, leaving her to be raised by her grandfather and a large house staff. The grand family home had a revolving door for freedom activists who dined and stayed, inadvertently educating Indira even further. At age 12, Indira started a child activist group called the Army of Monkeys that relayed messages and helped adults involved in political protest. At fifteen, when Gandhi came out of one of his hunger fasts, he requested that Indira serve him a glass of orange juice. But it was still an existence where Indira was educated at schools run by the British, even though she wore the khadi cloth that Gandhiji advocated.

After coming out of prison, Kamala was ill with tuberculosis. Like many wealthy Indians did, the Nehru family went to Europe for the healing air. The Nehrus set up residence in Geneva, Switzerland, where the climate helped Kamala, and they mingled with people of many nationalities and political beliefs. Young Indira traveled by foot and tram by herself to her international day school, another unusual activity for a girl in the 1920s. Shortly after Indira finished high school, Kamala expired from her chronic tuberculosis. Indira grew even closer to her father, who sent her for a broad education that included Shantiniketan in Bengal, and Somerville College in Oxford, England. She was there during the 1930s, when activism for Indian independence was also occurring in England. In these circles, though, Indira was always seen as a small player: when she spoke nervously in front of a group of activists in England, people joked about the squeaky, high pitch of her voice. Other times in India, her quiet nature in group settings led her to be labelled a “dumb doll.”

Marriage in 1942 to Feroze Gandhi

Marriage in 1942 to Feroze GandhiYet people took note of her, given her famous parents; especially a handsome young activist from Bombay named Feroze who met her mother in Europe, and following Kamala’s death, became closer to Indira. Born a Parsi with the original surname Ghandy, Feroze changed the spelling in the 1930s, perhaps to align with his mentor, Mahatma Gandhi. In 1942, Indira married Feroze against her father’s wishes, although he and many political power players attended the wedding, which Mahatma Gandhi had warmly endorsed. Because of her new surname, many people mistakenly believed that Indira was connected by marriage or blood to Mahatma Gandhi’s clan.

After marriage, Indira declared a desire to focus on motherhood. She gave birth to two sons, Rajiv and Sanjay, early in her marriage, and in these busy years, turned down opportunities for roles in the party. Yet in 1947, when her father was elected as the first prime minister in independent India, she faced an offer that was hard to refuse.

Jawaharlal requested her support as a political mate, asking her to leave Feroze to come to live with him in New Delhi and serve as his official hostess. By this time, Feroze was busy in Lahore running the National Herald, a newspaper founded by his father-in-law. There were also strains in the marriage caused by Feroze’s extramarital relationships.

Indira took her sons with her to her father’s place: Teen Murti Bhavan, the “three statues home,” resting on 30 acres in Delhi. She hosted visitors and accompanied her father on political missions. Within a few years’ time, Feroze became largely absent from her life. He died of a heart attack in 1960 at the age of 47, an event that Indira spoke sadly about, despite the long separation between then. She never married again.

Indira’s 1959 election as Congress Party President

Indira’s 1959 election as Congress Party PresidentIndira had gradually increased her political activities began in the 1950s, and was elected as President of the Congress Party in 1955. In this role, she assisted her prime minister father with challenges that arose nationally, including her infamous decision to disband the state of Kerala’s elected Communist government in 1959.

Jawaharlal Nehru died as prime minister in 1964 from a heart attack. The next elected prime minister was a Congress Party politician Lal Bahadur Shastri, who offered Indira a choice of appointments. She chose Minister of Information and Broadcasting, a job that wasn’t especially prominent. In January 1966, Shastri visited Tashkent and had a sudden violent heart attack, turning blue from a cause that was never discovered. The Congress Party elected Indira as the next prime minister. Yet shortly after stepping into the role, the right wing of the Congress Party challenged her. She won a narrow victory in the 1967 election and had to serve with a deputy prime minister, Moraji Desai, a politician whom she didn’t trust.

In 1971, she had a strong reelection victory, but there was no time to relax. Trouble was brewing in Eastern Pakistan, where the Bengali-Urdu speaking population wanted to become its own country. These guerrilla fighters were aided by Indian troops, at Indira’s direction. India’s invasion of Pakistan resulted in the war finishing quickly and the creation of Bangladesh. This triumph enhanced Gandhi’s image and led her New Congress Party to a landslide victory in national elections in 1972. However, India’s food shortages, price inflation and regional disputes made the next few years challenging. A rival politician with his own party argued that she’d been fraudulently elected in the 1975 election.

Indira declared a state of emergency, giving herself great powers to arrest political opponents and suspend a free press. During this time, her younger son Sanjay assumed a large role in her government and directed a mass sterilization of India’s rural poor. When Indira finally ended the emergency and agreed to hold a new election, she lost to the rival Janata Party. A trial followed in which she was convicted of corruption and briefly imprisoned. But soon thereafter, the rival party fell apart, and she ran for prime minister on the Congress party ticket in 1980, winning again. Nobody had called her a dumb doll for years. Her nickname had become Iron Lady.

Learning steps from folk dancers

Learning steps from folk dancersIndira Gandhi seemed blessed with election magic. Yet her very difficult challenge in the 1980s was the rise of Sikh separatists in the state of Punjab. India She ordered the army to storm a holy site, the Golden Temple in Amritsar, where Sikh militants were believed to be staying. The resulting carnage was not forgiven, and in 1984, one of her personal bodyguards, a Sikh who was sympathetic to the militants, shot her to death while she was taking a morning stroll through her beautiful garden.

As things stand, the incumbent president, Joe Biden, will run again on the top of the Democratic ticket. And I don’t expect any of the possible women candidates for president this year will have such a wild, and ultimately tragic, political story.

But still . . .

Note the ways that Indira Gandhi and Kamala Harris are similar. Both grew up with significant childhood independence, and they became fluent in multiple cultures, given their connections to different countries and religions. They became activists in young adulthood, and they selected husbands with different religions. And these husbands weren’t the ones who gave them assistance in their careers; father-figure politicians played a role.

Sometimes a preponderance of small advantages can add up to possibility. But in 2024, will the chance be there?

Thanks to the Indira Gandhi Memorial Trust for all photos used in this essay

The post Indira Gandhi, the Iron Lady appeared first on Sujata Massey.

June 12, 2024

Eating With My Eyes

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

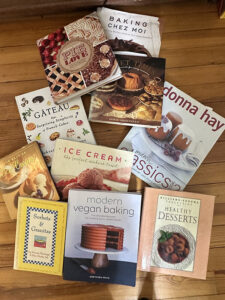

When life is stressful, resting my eyes on clear surfaces and straight lines helps me take a deep breath. Getting through the last pages of an edit is always a tough time—I’m housebound and frustrated. So during one of my stomps around the house, I caught sight of some overcrowded bookshelves and became obsessed with purging them. I expected this book cleanse would be easier work than my semi-annual clean-outs of the towering shelves in our dining room. This was a simple matter of tending to the walnut and maple-joined bookcases my husband built in our butler’s pantry twelve years ago. He’s tremendously creative, and it its a sturdy, six-foot long, granite-topped set of two sturdy shelves that can hold almost two hundred cookbooks.

I find it difficult to retire a cookbook. This is no matter whether it’s been used a lot in the past and has become threadbare or is pristine because of minimal use. I probably struggle also because I have strong feelings about cookbook authors. These writers often have professional cooking backgrounds. They test their recipes multiple times, they use science and history, and they are usually involved in the food styling and photography. My very favorite cookbook writers are also charming storytellers who mix personal tales along with teaspoons. This contingent is headed by the dearly departed M.F.K. Fisher, Laurie Colwin and Elizabeth David. Still living, and writing wonderful stories along with their recipes, are Molly Wizenberg, Amanda Hesser, Dorie Greenspan, Hannah Che, and Priya Krishna.

Until now, I hadn’t realized that so many food writing favorites are women. Is focusing on writing because of women’s exclusion from chef jobs for so many years? Or is it because cookbooks are a subgenre of “women’s books?” What about the madness of dessert cookbook reading—does reading them hit the same brain receptors as a kiss?

There still are male authors on the shelves, of course. The most favored one is the late Craig Claiborne, who was restaurant critic and food editor at The New York Times from 1957 to 1986. Claiborne doesn’t make time for stories, but he writes luscious recipes, never mind the vast amounts of butter and cream in most of them. Claiborne is known for multiple books, but our family favorite was The New York Times International Cookbook, published in 1971, the time my parents were setting up house in Minnesota. I can still picture the thick, dog-eared hardcover taking up a big part of a small shelf in the tiny hall just off the kitchen. Whenever my parents wanted to make something exotic like Greek pastitsio or Hungarian goulash, they cooked from this book. The three children in our family had the chore of cooking supper once a week; the good news was it could be anything we wished. I tended to use the cookbook’s French section, because I was enthralled with the poetic names of the soups and entrees. My sisters favored the Italian section and became adept with spaghetti and meatballs, spaghetti carbonara, and even pizza. Yes—in the 1970s, in our family, nobody ever phoned out for pizza delivery—it was made from scratch! My parents and I sometimes had a conversation about what we would cook for Mr. Claiborne if he ever came to dinner. I wanted to make Chicken Chasseur, but my parents said Indian. They were firm in their belief that this was one area of cooking in which they were accomplished, and he was an amateur.

After I went away to college in Baltimore, I was thrilled to find a first edition of The New York Times International Cookbook in a used bookshop. I used it to cook for roommates and friends. The first meal I ever cooked for my future husband, during our college days, was his French section’s Chicken with Cream and Tomatoes. I was nervous about Tony having to wait too long, so I cooked very fast—and part of the interior of the chicken breasts was a vivid pink.

The following summer, I had a New York romance and was exposed to sophisticated cooking of the moment. I became enchanted with a cookbook that may have defined the 1980s: The Silver Palate Cookbook, written by Julee Rosso and Sheila Lukins. I learned about the luscious recipes paging through the book while visiting my boyfriend’s mother’s dream kitchen—and yes, she cooked from it—and did it well. My romance fizzled, but the fabulous mother generously gave me my own copy of the cookbook. I left New York without a boyfriend, but I now had a mastery of pesto and dark chocolate cake.

After college I went to the Baltimore Evening Sun as a general assignment features reporter, and cookbooks fell into my life at a rapid pace. It all started because I offered my reviewing services to a food editor overwhelmed by dozens of books sent by publishers each week. I tried out at least one recipe from each book and wrote reviews, getting letters of thanks—and sometimes anger—from the book’s authors. In the process I filled my IKEA Billy bookcases with that spanned such topics Thanksgiving dishes, biscuits and scones, and Indian microwave cooking.

I gave away about a third of my cookbook collection before I got married and moved to Japan. At the Japanese bookstore Kinokuniya, I bought several beautifully photographed Japanese cookbooks—not quite admitting to myself that the dishes were more time-consuming than I could manage. But I still ate through those books with my eyes.

It’s the same for me now that I’m back in the United States: I have an insatiable hunger for cookbooks that is only amplified by cookbook author interviews on podcasts and cooking videos on YouTube and Instagram. Because of the plethora of food bloggers, it’s easy to find recipes for free on the internet; however, the likelihood of these recipes failing is far greater than recipes by an experienced food writer tested and cleared for publication in a book. Because of the rise of googling for recipes, I fear for the economic wellbeing of cookbook writers, and this is another reason why I rationalize my cookbook buying.

Passing the milestone of forty, health became a powerful reason to invest in new cookbooks. I find myself going through phases of various eating styles with great enthusiasm. My vegetarian period involved several books on Indian vegetarianism by Madhur Jaffrey, and American books like Mark Bittman’s 996-page doorstopper, How To Cook Everything Vegetarian. Mark Bittman also helped me through a pescatarian phase with his seminal book, Fish. During the years my kids were young, food sensitivities flew by the wayside. In the interest of time management, I turned to slow cooker books and anything that had the word “Quick” on the cover.

Late at night is still my quiet time and the perfect opportunity to turn to rereading my favorite food memoirs. My love for literary food writing began when I accidentally discovered a few M.F.K. Fisher classics that described her years living and dining in France—from glorious carefree days to severe food shortages during World War II. I devoured it all. The example of brilliant M.F.K. Fisher led me to think I could make the best of leaving the newspaper to be a trailing spouse—if it were overseas. As a newlywed—just like M.F.K.!—I would settle abroad in an unfamiliar, stimulating location where I would gamely take up a life of eating at restaurants, shopping at exotic markets, and learning to cook another cuisine.

And reading these books brings me back to that honeymoon period with Tony in Japan. Throughout our time living in Hayama, a small town an hour south of Tokyo, we explored every type of café and home dining experience. This translated to rotary sushi bars, tea ceremonies, tofu-making classes, and old-fashioned US Navy dinners where a Campbell’s Soup-based casserole might be served with fanfare. But instead of writing a food memoir about this period, I found myself drawn writing a mystery that included food. For instance, there’s a horse sashimi appetizer in The Salaryman’s Wife that is taken straight from my memory of a tense New Year’s Eve dinner in the Japanese Alps. Another book, The Pearl Diver, delves into the backstage world of a Japanese fusion restaurant. Years later, I can’t imagine writing a book without the help of restaurant experiences or cookbooks. I often turn to regional Indian cookbooks to set the tables in scenes within the Perveen Mistry series. The Widows of Malabar Hill’s paperback edition contains an easy menu of dinner recipes meant for book-club potluck meals.

So now that I’ve kissed a few cookbooks goodbye, I have good news. My brain calmed, and I finished my book edit. And I predict the eleven books I’ve left at various Little Free Libraries around the city will soon find themselves in new homes, inspiring people—whether they make a meal or not.

The post Eating With My Eyes appeared first on Sujata Massey.

April 10, 2024

My Third Act

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

My sixth birthday

My sixth birthday“I don’t want to talk about age.”

A smart, accomplished, and elegant woman friend said this to me recently. I still do not know her age and am not going to ask her again. I suspect that this lovely person believes she’d be treated differently if people knew; perhaps even rejected.

My mother also doesn’t do much chatting about her age. She’s a vibrant woman, beautiful inside and out, who raised three daughters, traveled the world enthusiastically and is now retired from business life. Speaking candidly, she says that she sometimes has a feeling of irrelevancy because she’s passed 80. In public, strangers seem to overlook her and don’t take what she says seriously.

Ageism is a word that is believed to have been coined in 1969 by the psychiatrist Robert N. Butler, when speaking to a Washington Post reporter about some people’s reaction to the housing for the elderly poor being built in their neighborhood. And while this original example is quite macro in nature, there are so many micro-aggressions and other insults. I’m learning that people being treated as “old” rather than the people they feel like inside is painful.

My first experience was ageism was brought about by myself, to myself. I was 43 years old and standing in the checkout line at Giant Foods with my toddler daughter and a babysitter. The friendly cashier asked if the 23-year-old babysitter was my daughter. I was horrified as being mistaken as someone who could have such an old child—that it meant I was likely fifty or some similarly grotesque age. And now, the irony is that I have a child who’s almost 23.

And I am actually SIXTY years old.

With dear friend Prem (over age 80 and long walks daily)

With dear friend Prem (over age 80 and long walks daily)When I was much younger, I imagined certain stages so clearly. These included transforming into a college freshman; turning into a news reporter; becoming a bride; and being able to write “mother” on a pediatrician’s form. I never let my imagination roam as far as becoming a grandma; and now, when I look at my young adult son, I ponder whether he will have a role in that someday.

Then I sternly reprimand myself. Asking my son to make me into something else isn’t a strong way to live—it harkens to the other identity milestones. It was a college admissions officer who granted me entry as a student; an editor who hired me as a reporter; a boyfriend who asked if I’d marry him; and a judge who signed the papers allowing me to be an adoptive mother.

My recent step up to becoming 60, though, is a solo accomplishment. And I’m surprised to report how good it feels to be here. I’ve heard the fifties is a very happy decade for many women in terms of professional life and personal freedom. Fitting the stereotype, this was the era that I started a new mystery series that was my most successful. I became very busy with books and the adjacent promotional responsibilities. But my longed-for decade of professional recognition was also the time in which my immune system battled two diseases and my family suffered many emotional hardships, including the loss of our daughter. I am glad to gently close the door on my fifties and embrace the Big 6-0.

And how strong I feel! I watch myself jumping on my small rebounder trampoline several times a week, light strength training, swimming and doing water-aerobics, and fast walking over hilly terrain with older women friends who are faster than me. I feel confident I’ll get even stronger this year. Someday in the far future I might shuffle and have trouble walking. But not for a long time—and its quite possible that my experience of waning strength, body and mind, won’t be catastrophic.

The crowd couldn’t stop talking!

The crowd couldn’t stop talking! Dear friends Joff and Johnie, and my Tony

Dear friends Joff and Johnie, and my TonyI asked Tony what he thought about me planning a significant 60th birthday party. He hadn’t wanted one for himself, but he liked the idea of my doing it, especially at a cozy Basque restaurant, La Cuchara, a few miles from our house. The invitations went out: not to every friend I have, but to the ones I’ve spent significant time talking about highs and lows with during recent years, as well as longtime friends from college and past jobs, and those in my family who were able to come.

With my sisters, Rekha and Claire

With my sisters, Rekha and ClaireIn the four months before my party, I read a book called The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why It Matters by Priya Parker. It’s not a regular party planning book; it’s about bringing meaningful connection to people through a host’s work. I was intrigued enough to also take Priya’s video course that aids in personalizing your own gatherings with plenty of cases to study and worksheets to dig deep into one’s true motivations for bringing people together. I took it all to heart. The invitations I sent hinted that each guest should not bring gifts, but expect to share deep conversation.

I greeted everyone at the door and handed them a paper with a random icebreaker question to ask someone they didn’t know. At the designated dinner tables, people were grouped and asked to answer a question or two of their choice. The first question asked them to talk about about a twist in their life and what personal strength they used to pull through. The second option was to share a piece of advice they wish they’d had at a younger age. As I went around the tables to make sure people were OK, a friend joked that I was being “very prescriptive,” but by party’s end she was raving about the joyous communication the table conversation had brought her. And this was my secret intention all along: I wanted people to find strength and happiness in themselves.

Cringing as Mom reads my 8th grade essay!

Cringing as Mom reads my 8th grade essay!I sat with my husband, my mom and stepdad, and three other friends. The party buzzed with conversation at the six tables where friends and family sat. During dessert, many friends spoke aloud to the whole group on their thoughts about aging as well as our shared relationships. I stood next to them and felt truly humbled by the sincere and loving tributes.

In the days since the party, I’ve mulled over that feeling of being overcome during the tributes. I recognized not being able to accept praise is the very demon that makes people feel miserable about aging. If we positively credit to others, why can’t we give ourselves credit, too? I always thought it was corny when people spoke of “loving themselves,” but now I understand it’s not only a desirable trait, but one necessary for mental survival.

My friend Betsy said that aging means living deeply. In my mind, this idea means accepting sadness and loss: feeling it, rather than pushing it away. I do that better at sixty than at twenty. I’m also trying to remember to look at all the people around me with fresh eyes, noting their vulnerability and gifts. This generally results in good feelings and can transform an encounter.

I am a woman entering the third act of life. In books and movies, that final third is where the pace really picks up and a climax approaches. Of course, there will be a dénouement; but reading the ending before its time is never a good idea.

Striding happily forward, Karin and Bharat

Striding happily forward, Karin and BharatThe post My Third Act appeared first on Sujata Massey.

March 27, 2024

When A Bridge Falls

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Like so many Baltimoreans, I spent yesterday on the phone telling friends and relatives that I was alive. No, I hadn’t been anywhere near the Francis Scott Key Bridge early Tuesday morning. But I was following the news from before sunrise, because my email carried an emergency bulletin from the city. A bridge had collapsed—not just any bridge, but one bearing the name of The Star Spangled Banner’s author—a man who had witnessed the British attack on the Baltimore Harbor during the War of 1812 and written the song in honor of the defending Americans at Fort McHenry.

One of the first matters raised in the press and private conversation was whether this shocking collision had been an attack. A falling bridge reminded me of falling towers. And ships are supposed to be protected with backup systems should power be lost—so what happened?

The Dali, a cargo ship carrying containers bound for Sri Lanka, reportedly had its lights flicker off before they came back on, leading to speculation that a generator did kick in. Still, the crew realized they could not control the ship’s propulsion and issued a May Day signal. Fortunately, the alert was received and communicated instantly by the Maryland Department of Transportation. Police closed vehicle entry to the bridge just before the Dali hit one of the bridge’s major supports.

That was too late for a small group of construction workers atop the bridge, because after the collision, the bridge collapsed in forty seconds. Two men were rescued from the water, and the Coast Guard has announced that it’s unlikely the remaining six workers could have survived the cold waters this long. Of course, some cars might have already been on the bridge when it was closed; so there may be more cars and bodies submerged in the water.

According to a colleague who knew the crew, they were immigrants from El Salvador, Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala. The workers were employed by a Baltimore County contractor who supplied labor for bridge repair and construction. Baltimore is the country’s largest point of entry for foreign cars, and overall, its third largest industrial port. And it’s one of the nation’s oldest ports, dating from the beginning of the 17th century, when tobacco was the chief imported product. The early locations were Fells Point, a beautifully preserved waterfront district, and then and Inner Harbor that edges our downtown area. The original owners of the 1897 house I live in had a saloon on Water Street near that harbor, which was a bustling, rowdy locale. As decades passed, more areas to receive cargo were built further out from the city itself. The northwest areas of the Patapsco River are the location of side of the Helen Delich Bentley Port of Baltimore, the chief industrial port.

The Dali was built by Hyundai in South Korea in 2016. After the Dali had an accident involving propulsion at the Antwerp, Belgium Harbor, its first owner sold it to a Singapore company, Grace Ocean Pte Limited. The ship’s technical state was managed by a company called Synergy that reportedly has a history of three worker deaths on their vessels since 2018. The 22 crew members of the Dali are Indian, and they are still on the boat, along with many of the 4600 20-foot containers of cargo. It seems miraculous that the whole crew survived the bridge collapse.

Civil engineers, boat experts, and veteran seafarers will be busy explaining the cause of the accident—ship company, bridge design, and perhaps something else—for months to come.

Yet I imagine that the construction workers on the bridge were in the wrong place at the wrong time only because they’d had to leave dangerous homelands. Upon arrival in Baltimore, they found jobs that ensured American comfort: raking leaves, cleaning bathrooms, digging up and repaving roads. For the Dali’s Indian crew, the motivation was likely similar. The promise of a decent paycheck sends many young Indians abroad to jobs where they work overly long hours under difficult conditions.

Until the bridge accident is cleaned up, Baltimore’s port will be closed to traffic. The cost of the lost business, and rebuilding the bridge, are huge; even if the latter is paid for by U.S. taxpayers and shipping insurance. But it’s also a very great cost to our humanity, if we forget that those most hurt by the bridge crash are the folks do the invisible work of making our life easier. And we will likely never know their names.

The post When A Bridge Falls appeared first on Sujata Massey.

March 12, 2024

The Super Bowl of Books

This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

I write this during my last few hours in the March sunshine of Arizona. How lucky I feel to have had a mystery gathering again during a very drab time of the year in Baltimore. I arrived on March 8 as a guest at the Tucson Festival of Books. This nonprofit event, run by 2000 volunteers, is said to draw 175,000 annually, making it one of largest free public book festival in the country. Yet the vast space of the University of Arizona campus kept it from feeling crowded.

The festival is operated by a private foundation (including many University of Arizona graduates) and is aided by the University, the Arizona Daily Star newspaper, Tucson Medical Center, other donors and Friends of the Festival.

Tucson’s huge success at making books into a kind of state fair on academic grounds amazes a book festival veteran who is used to much smaller venues. How exactly do these organizers gather up six National Book Award winners, the sweetly hilarious comedian Sarah Cooper, and the outstanding mystery novelist T. Jefferson Parker, Lisa See, Abraham Verghese, pictured below, and 300-plus writers of varying levels of fame? How do they inspire so many Arizonans, whether year-round or snow-birding, to sign up for tickets ahead of time, show up early to wait in long lines, and splurge on the writers with kind words and book purchases?

My guess is this 16-year-old festival has built and built word of mouth recommendations until people can’t imagine not going. For Tucson, it’s almost like having your own Super Bowl—although the tickets are free. But I suppose this analogy may work more for people who are book nuts rather than sports fans.

I came in knowing that I would have the chance to participate on three panels. A bit of work, but it felt like play. Every one of my three panel events, the moderators were well prepared and the conversation between participating authors was thoughtful, with usually a humorous person in the middle of it (thank you, Lev AC Rosen, and Catriona MacPherson). Audience members seemed an even mix of established fans and curious newcomers. An authors’ lounge and a happy hour at an off-campus bar let the writers cut loose with nerdy craft conversations around questions like “Should I be writing in close third-person?” and “How much time do you really spend writing and rewriting one book?”

Hotels throughout Tucson provided rooms for visiting authors. I was booked in at an Aloft Hotel on a busy road called Speedway. The best thing about was that it was that just by ducking behind the hotel, I had a pretty and quiet fifteen-minute stroll to the heart of the festival’s buildings on the University of Arizona’s vast campus. One day I made three round trips and was thrilled when my phone app told me I’d clocked 14,000 steps.

On the way there I goggled at the interesting fraternity and sorority buildings that were so different from those I’ve seen at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, and the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. These were all single story and fitted smoothly with the Western vernacular architecture featured throughout Tucson. I noticed fake grass installed in front of many of the Greek buildings. This made sense because of the desert environment, although the gardening fairy who lives in my brain was whispering “try native plants, please!” Most of the official University buildings had moved into this direction of minimalist native plantings. One thing I loved about the setting was a sense that the state’s premier university belonged to everyone, whether or not they were or students.

The campus itself had a mix of grand turn of the century brick buildings, brutalist mid-century shapes, and newer ecologically smart constructions. I had fun roaming the vast bookstore and then going around the campus looking for turtles in the pond. It’s great that a free streetcar system runs along the campus and into the city.

And how was the intellectual component, you ask? The panels were excellent. Everyone I spoke to, who’d been a participant, felt positive about it. My panel topics were The Wide, Wide World of Mysteries, Searching for Social Justice, and Mid-Century Murders. After we spoke, I met new readers and people who were in Arizona for a break, including my mom’s friend, Betsy, who was visiting from Minnesota. One thing I loved about the setting was a sense that the state’s premier university belonged to everyone, whether or not they were or students. This could be a positive action for other colleges and universities to try.

On Sunday morning, I got my Arizona native plant fix in Oro Valley. I met my friend Patti, a librarian in the Pima County system, at a restaurant set within Tohono Chul park, a 49-acre botanical learning center and park. Thong Chul exists because of the generosity and foresight of Richard and Jean Wilson, a couple who began purchasing small patches of desert in the Oro Valley, refusing many times to sell to developers. When the city condemned an area nearby to allow for widening a road, the Wilsons insisted that the very old and tall saguaro cacti that had grown tall over hundreds of years be carefully removed and planted at Tohono Chul. The Wilsons’ private property developed into a private park in the late 70s and was formally dedicated in 1985.

I enjoyed my delicious egg breakfast combining Mexican and Native American foods in an original hacienda house on the property, now a restaurant called the Garden Bistro. Then it was time to lather on more sunscreen and wander amidst the spectacular, healthy cacti and other desert plants. The desert landscape feels surreal for me, even though I’ve now been to Arizona two years in a row. I admire how these plants store water and nutrients and endure without trouble the blistering conditions that will arrive in a few months.

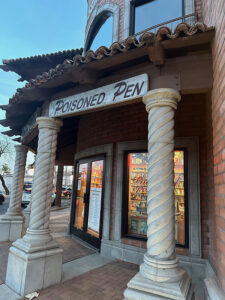

At Poisoned Pen Bookshop, two hours away in Scottsdale, a refrigerator selling COLD DRINKS stands among the bookshelves. I got water there and so much more when I visited on Monday for an event with one of my fellow Soho Press authors, Stephen Mack Jones. Stephen and I chatted about our recent books and writing mystery series in general. We were happy to meet the bookstores’ regulars: not only Arizonans, but a warm couple from Detroit, where Stephen’s books are set, and friends from Kansas City, who had also attended the Tucson Book Festival and driven out to listen and chat some more.

Maybe the wide desert spaces, towering mountains and endless blue sky bring more than visual serenity to people living here. It could be that they open space for introspection and reading. I was grateful to be in Arizona, and hope to return.

The post The Super Bowl of Books appeared first on Sujata Massey.