Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 379

November 16, 2014

Weekend Special: When we post 10 things you missed last week on FB and Twitter

Finally, there were these two music videos by some of our favorite artists Somi and M.anifest which definitely set a standard about what we expect from a music video. Step your game up

The Limits of Alternative Africas

Hard on the heels of an anti-climactic election season in the US punctuated by myopic views of the world and cataclysmic what-ifs, the resurgence of Nikolaj Cyon’s counterfactual map of Africa circulating on the web last week was a welcome relief from realpolitik run amok.

Cyon, a Swedish artist and self-proclaimed revolutionary, asks us to think back to the fourteenth century and imagine the ravages of the Black Death to have been worse than they were, a demographic catastrophe so severe that Europe’s recovery was insufficient to restore vibrant economic life, let alone generate the impetus for maritime adventures. To follow Cyon’s logic: a diminished Europe would not have produced colonial powers. How then might Africa’s history have unfolded?

I’ll admit, my first reaction to the map was more puzzled than entranced. Some of the units Cyon depicts are familiar language communities, some are historical kingdoms, others represent economic or trading relationships, while a fourth category extrapolates wildly different outcomes from historical kernels (why the fanciful Al-Magrib instead of the imagined growth of an actual Moroccan kingdom such as the Almoravid or the Sa’dian, for example?) But seeing this only as miscued scholarship limits our perspective.

As art, the map is more inviting. I don’t worry that Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon don’t really look like women. If I don’t worry about a historian’s obsession with accuracy, what can I take away from Cyon’s evocation of a Europe-free African history? The greater presence of Arabic names and Muslim-influenced political structures makes sense, as does the diversity of political forms. But would the Swahili city-states have consolidated into a single polity? Would Merina or Dahomey have been large kingdoms without the slave trade? Questions, rather than criticisms, come through and I am reminded of issues I always want my students to grapple with: today’s geopolitics were not inevitable; contingency matters in the study of history.

But there are other, difficult realizations that Cyon’s upside down Mercator projection, colored with a palette surely intended as reminiscent of historical, colonial maps, cannot banish. Our reality conditions—and limits—the alternative worlds we imagine. Even the best science fiction has to connect to elements of lived experience (Frank Jacobs at Think Big explicitly connects Cyon’s project to Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Years of Rice and Salt.) Eurocentric presumptions, and ideas deeply rooted in the production of western knowledge are part of the inescapable reality of both Cyon and his audience.

Debating whether or not Bujumbura would have been a capital without European intervention misses the mark. Eurocentrism runs much deeper. This project, although it depicts a markedly altered political landscape, sits comfortably within the norms of western geospatial understanding. Like Martin Lewis and Kären Wigen’s Myth of Continents, Cyon’s map productively disrupts conventional spatial representation. Cyon’s counterfactual vision reminds us that naming conventions—Africa, the Atlantic Ocean—are constructions and not inherent in the place. The map also shows that colonization and its aftermath were not inevitable, but it doesn’t imagine an alternative to bounded sovereign territories. Even without the Westphalian state system translocated through imperial adventure, we’re still looking at a map of contiguous states.

Given what we know about African state formation and territoriality, why presume a map that is completely filled in with claimed land? Both IMartin Lewis and Kären Wigen have painted pictures of African pasts with fluid boundaries and plenty of interstitial spaces. Granted, the Atlantic slave trade and colonization directly account for Africa’s “under-population” relative to terrain and compared to other regions, but imagining an alternative future free of those legacies might speculate about a political-economic order that did not allocate every square meter of space to an administrative unit.

Even more imaginatively, how might we visually represent polities constituted by people rather than territory? Since people, even farmers, are not permanently rooted in the ground, our mapping project begins to look very different. Both Tongchai Winichaikul and J.B. Harley reveal the pervasive cultural frameworks embedded in visual representations of space, politics, and human relationships—representations that we call maps. This visual register bounds the possibilities of communication as much as our linguistic limitations do. Cyon’s Alt-Africa map is arresting and provocative, but it can only go so far.

I can’t think or talk about Africa except through the veil of a specifically western epistemology. It’s not just that the languages in which I can converse are Indo-European. Improving my grasp of isiXhosa won’t get around the other stumbling blocks in my head, a set of assumptions about the way the world is ordered, and knowledge produced. I can’t just set that aside without unraveling the rest of the stuff in my brain.

Like everyone, I walk around with a set of cultural presumptions inherited from the community in which I was raised. A liberal arts education simultaneously helped me develop tools with which to perceive hidden transcripts and implicit power structures while also disciplining other presumptions firmly into place. I can suspend—at least for a little while—my reluctance to think about language groups, kingdoms, and trading networks as equivalent geographical spaces. I might disagree with some of Cyon’s presumptions about how a Europe-free history of Africa would have played out, but the fact that we can debate those presumptions, or together read the map he produced and come to different conclusions speaks directly to the western epistemology we share—and can’t shake. I want to push Cyon to check more of his Eurocentrism at the door, but as long as we’re both talking about Africa as a place he and I might reimagine, it’s clear that legacies of dominance rooted in histories of conquest persist.

November 15, 2014

5 Questions for a Filmmaker … Jihan El-Tahri

Legendary documentarian Jihan El-Tahri started her career as a journalist, working as a news agency correspondent and TV researcher covering Middle East politics before starting to direct and produce documentaries for French TV, the BBC, PBS and other international broadcasters. She has since directed more than a dozen films including the Emmy nominated The House of Saud, The Price of Aid, which won the European Media prize in 2004 and Cuba: An African Odyssey. Her most recent feature documentary Behind the Rainbow, which examines the transitional process in South Africa, has won various prizes since its release in 2009. She is currently finalizing a three-hour documentary provisionally titled Egypt’s Modern Pharaohs. As if this wasn’t enough, El-Tahri has also written two books, The 9 Lives of Yasser Arafat and Israel and the Arabs: the 50 Years War and is engaged in various associations and institutions working with African cinema.

What is your first film memory?

I actually remember watching Shadi Abdel Salam’s The Mummy at a hotel screening in London when my family moved there. I was around 5 and I knew I was Egyptian and the mummy terrified me but got me very curious. I remember the lighting of the film until today. It made these ancient stories so real and timeless.

Why did you decide to become a filmmaker?

I started off as a journalist because I truly believed that journalism is the first draft of history and if done properly it could actually change the world. Young and idealistic I thought I could change the world single handedly … Alas, the Gulf war of 1990 was a rough wakeup call. It is then that I realized that I needed to reassess many things, including my own identity and what stories were important for me to engage in. I finally realized that I could only tell one story at a time if I wanted to do it properly. Documentary was the obvious choice. I made numerous “observational” films but that still was not satisfying. Then one day I was hired to work with a company in the UK and they gave me their last film series to watch: Death of Yugoslavia. A 7-hour series that I stayed up all night watching. There and then I decided that that was the kind of documentary filmmaking I wanted to pursue.

Which film do you wish you had made and why?

Answer 1

In 1992 I wrote an extensive treatment for a film based on a topic I had been researching for a full year. The film was titled Allah’s Holy Warriors. It was about the brand new phenomenon of Islamic warriors returning from Afghanistan under the leadership of a then unknown commander called Osama Bin Laden. They had offices at Finsbry Park in London and I had spent weeks convincing them to allow me to film. They finally gave me the OK, I did go film a short sequence while they where in Sudan. They were due to leave and return to Afghanistan and I obtained the OK to actually film the move and spend time filming in their camps. I tried selling this idea to any TV channel but nobody was interested in an unknown Islamic fighter and his ragtag troops.

Without the backing of a channel it felt too complicated and decided to wait and do this story later …. Mistake!!

Why I think I should have done this film? It’s is not because of the high profile the story would have had later, My regret is mainly because it was a time when this totally inaccessible and incomprehensible group were willing to talk and explain their grievances, who they are and why their fervent beliefs are unshakable. I always feel that maybe if I had done that story, it would have allowed me – let alone others – to understand that whole Islamic “terrorism” phenomenon that has altered the face of my continent and the world actually.

Answer 2:

I hesitate between Sofia Lost in Translation – for the way she managed to isolate a very specific and unusual sentiment of alienation as well as using the city as her main character – and

’s documentary Taxi to the Dark Side. I am in total awe of how he managed to – coherently and uninterruptedly – turn the murder investigation of a simple unknown taxi driver in Afghanistan into a worldwide interrogation of a political system. The film is thorough, informative and scary. It is perfect proof that a film can uncover and contest a superpower efficiently and dramatically.

Name one of the films on your top-5 list and the reason why it is there.

Newton film Rage

The film tackles multiple sensitive and personally touching issues with a force and a sensitivity that I find mind blowing. It is about being of mixed race, the case of my children and many of my friends. This space of not knowing where you belong… It is about negotiating this space as an outsider. Being a bit of a nomad I so understood and identified with the main characters’ clumsy attempts to fit in and his rage when realizing that he never will. Tackling this film through music and youth urban culture made the film universal, informative as well as extremely sensitive and compassionate.

Ask yourself any question you think I should have asked and answer it.

I guess I will add the question that I always ask myself: Is it worth it? Meaning is making a film with all the pain, the heartache and the minimal returns it entails worth it?

When I am frustrated about spending 3 to 4 years of my life chiselling away at what seems to be a mountain, my answer is usually: No! But once the film survives the first year and continues to make sense, I believe that there is nothing more precious than telling a story that can talk to others and allows your voice as a person to exist. Now old and much less idealistic, I still believe that this single drop in the ocean does make a difference, if only in a single other person’s life.

* The ‘5 Questions for a Filmmaker …’ series is archived here. Image Credit: Antoine Tempé

November 14, 2014

Mexico’s Deadly Virus

The United States lives in a state of constant fear. Currently, Ebola is to blame. The U.S. fears (but maybe also hopes) to be part of a world that is, to some American minds, every day likelier to live a pandemic outbreak like the one in The Walking Dead. But they are afraid to get infected without even realizing they have already caught something: indifference towards death.

It is an indifference that already “infected” the Mexican people and that has rapidly propagated throughout the world, even if few have mentioned it. Until last October 27th, around 13,000 cases of Ebola had been reported and 4,920 people had died of the virus worldwide, creating global outrage. Meanwhile, in Mexico, 57,899 homicide cases were reported ( (link Zeta) between December 1st, 2012, and July 31st, 2014. And there was barely any international news about them.

This doesn’t mean that some deaths should be more concerning than others. Ebola has highlighted again the dismal conditions that certain parts of Africa deal with, but also how the world is vulnerable to a distant pandemic. But, for years, those 60,000 deaths in Mexico did not highlight anything.

It seems these people died in the wrong place. Had they died, instead of Iguala, Ciudad Juárez, San Fernando, Ecatepec, Tetlaya, Aguas Blancas, Acteal, etc., in, München, Lyon, or Oslo, what would have happened?

These deaths seemed to not matter, to not make any kind of impact. Mexico has deteriorated to the point that, when a mass grave with 28 bodies was found, but they didn’t correspond to the missing people the authorities were looking for… it was reported as good news.

Nonetheless, the unfortunate disappearance of 43 students (I refuse to think they are dead) in Ayotzinapa and the murder of six of them by the municipal police of Iguala, in the state of Guerrero (acting, allegedly, under government’s orders), managed to shake the indifference of Mexico’s lethargic society. However, we Mexicans are still far from reaching our goals, basically because we are not sure what they really are. We are fighting different fronts and enemies as citizens.

I saw the press conference that Jesús Murillo Karam, Mexico’s General Attorney, gave last Friday and I could only think about all the victims. When I listened to the confessions from the Guerreros Unidos members, I thought the killers were also victims here.

They are also victims of the indifference; of the cynicism, arrogance, and ineptitude displayed by Murillo Karam during the press conference; of the sumptuousness of president Enrique Peña Nieto. “EPN”, as he is known, owns a seven million dollars house and his indolence showed when he took a trip to China and Australia amid the social and political crisis that Mexico is experiencing (he didn‘t even set a foot in Iguala, where it all happened).

All of them are victims of all the impunity that protects the whole political class in Mexico. The killers, just as the students, are also victims of a political system that has turned all of us into mere objects, devoid of our humanity. While describing how they tossed the bodies into a dump where they later burned them, one of the Guerreros Unidos members said: “One of us grabbed them by the hands and another one grabbed their hind legs. We swung them and then the bodies rolled into the bottom”.

Many Mexicans have organized massive protests, both in Mexico and abroad, trying to call the attention of international media and foreign countries, in order to pressure, politically and diplomatically, those in power in Mexico. Fortunately this is happening and they are turning their eyes towards what is going on in Mexico. They also have managed to pressure Mexican government to start finding real answers to questions that it hadn‘t answered until now. But it hasn‘t been enough. We have to spread a new disease, one that raises consciousness around the world about what happens in Mexico.

What the country needs in order to start seeing results is a complete transformation. That transformation begins with the spreading of information and the abandonment of an indifference state. We are seeing this happening and these are good news. Mexican people cannot get tired at this point. We must continue our struggle against this gigantic hydra that, “allegedly” is the one getting tired.

Mexico is looking for a helping hand. With the aid of non-violent arms we believe we deserve to get out if this huge mass grave that the country has become. Help and solace are wanted. This is why we have been taking the streets: to inform people of what is going on. We want to tell this story, and show the world that this indifference is scarier than a virus. If we manage to build awareness all over the world about what is happening in Mexico, somehow, I want to think, another step towards transformation will be taken. This is why we all must be Ayotzinapa. And in the end, we are all Ayotzinapa.

When Prince Charles went to Colombia

The official visit to Colombia by Britain’s Prince Charles, and his wife, the Duchess of Cornwall, left us with many picturesque moments, but two seemingly unrelated events stand out.

The first one took place on October 30th at the Centre for Peace, Memory, and Reconciliation in Bogotá, where the couple attended an event in honor of the victims of the armed conflict in Colombia. At the end of the ceremony, Prince Charles announced his religious, moral, and political support to the peace talks that the Government of President Juan Manuel Santos has been holding with the main guerrilla group in the country, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in Havana, Cuba.

The Prince also supported the official meetings that several groups of victims have been having with Government and FARC’s representatives in Cuba, a crucial part of the peace talks’ agenda that has sparked controversy among the right wing and conservative circles in the country.

His Royal Highness invoked his own experience that day: he narrated how his uncle, Lord Mountbatten, was killed by the IRA thirty years ago in Northern Ireland. “So,” he remarked, “I feel I do understand something of the bewildering and soul-destroying anguish that so many of you have had to endure.” Prince Charles has stated elsewhere the importance of finding a different answer to these instances of violence and searching for a more positive way to react to them other than vengefulness. “As one who has himself experienced the intense despair caused by the consequences of violence,” he concluded in Bogotá “it is my fervent hope that Colombians might find the strength to continue cultivating a commitment to peace and reconciliation in their own hearts.”

The second event was much more publicized in national and international media: on November 2nd, the last day of the visit, Prince Charles and Mayor Dionisio Vélez unveiled in Cartagena a plaque dedicated to the memory of “the courage and suffering of all those who died in battle trying to take the city and Fort San Felipe under the command of Admiral Edward Vernon at Cartagena de Indias in 1741.” Cartagena, which was under Spanish rule at the time, was besieged for two months by Vernon’s troops amounting to almost 30,000 men and a flotilla of 186 ships.

Vernon himself had defeated the Spaniards two years before at Portobello, modern Panamá, with only six ships, and his forces pillaged and destroyed the settlement. Against all odds, Spanish Admiral Blas de Lezo, with men numbering ten times less than the British forces, resisted the attack to Cartagena and was able to push back Vernon’s siege, in a battle that would become the Spanish Admiral’s last glorious victory.

The plaque was met with general outrage in the country. It was a memorial to these same invaders who, in the event of their victory, would have destroyed the city of Cartagena, and raped and killed its inhabitants, like they had done elsewhere before. Citizens and public figures condemned the ostensible contradiction of a city which honors those who wanted to assault, pillage and destroy it. It was yet another example of the colonized mind-set of the country’s authorities who would go as far as reverencing plunder just to please His and Her Royal Majesties.

It was indeed appalling to see the servile and submissive attitude with which Colombian officials treated the heir to the throne and his wife. And it was disturbing to witness the artificial displaying of Black and Indian traditions with no mention whatsoever of the fact that African and Indigenous descendants are the most neglected groups of people in Colombia.

But it was noteworthy that those angry at the plaque failed to denounce the same acts of pillage, plundering, rape and murder committed by those who founded and governed the city. Most of its critics seemed to have forgotten that Cartagena was a major slave port from where the treasures of the region were transported to Europe and where African people were brought and sold as merchandise.

And yet, it is not this servile, colonized attitude what I find the most problematic about Charles’ visit, but rather the point of intersection between the two events I have described: the attitude of a royal figure, the Heir to The British Throne, who in the same visit managed to honor the lives of British colonists and assailants, and identify himself with the victims of the armed conflict in Colombia.

Prince Charles used his own experience of forgiveness to defend processes of peace and reconciliation, and this is a praiseworthy initiative. It is also praiseworthy that he himself had defended the peace process with the IRA in spite (or perhaps precisely because) of his uncle’s death. What I find unacceptable is the comparison of his experience with that of those victims present at the meeting, not only because it is a completely different political scenario, but also because the Colombian conflict has some of its roots precisely in a vision of history of exclusion, segregation, and the silencing of the claims that the victims of the privilege class try to voice. It is a vision of history that the British Monarchy has embodied (and still does), and that is represented in a ridiculous way by Prince Charles’ gesture in Cartagena.

It is because Prince Charles is incapable of understanding the absurdity of traveling to a country that has been colonized by European invaders and commemorate those same actions of murdering and plundering that the very own British Monarchy carried out throughout the world, that he is unable to see why his comparison with the victims of Colombian internal conflict misses the mark so widely, and why his support to the process is flawed from the beginning.

Among those present at the Centre for Peace, Memory, and Reconciliation in Bogotá were Gloria Luz Gómez Cortés, the head of the Association of Relatives of Detainees-Disappeared Persons (ASFADDES), and Yanette Bautista, the sister of Nydia Erika Bautista, detained, raped, and disappeared by the militaries in 1987. These two women, who still suffer today directly from the persecution by the Colombian state and its armed forces and paramilitary allies, have for 30 years led the fight for the rights of relatives of disappeared persons to know the truth and seek justice against these same forces.

Prince Charles cannot say, as he said to the victims in Bogotá, that he understands the “bewildering and soul-destroying anguish that so many of you have had to endure.” In the same gesture of unveiling the controversial plaque in Cartagena (even if it probably was not his idea, but another of the servile displays of Colombian ruling class) Charles shows that his visit to Colombia is still framed by the colonialism that the Monarchy has meant for the world for centuries. The plaque (first destroyed by an angry citizen, and then officially removed) is no longer there, but the act and his words remain untouched.

Music Revue, No.4: Moni

I remember being awe-struck by a picture I saw in on the Sunday papers somewhere around 2005. The members looked militant in their shades and flowing locks. There was a sense of urgency in the female lead’s look which stuck with me: black shades, black beret, all-black everything! They reminded me of Peter Tosh and the Dashiki Poets at once, with a hint of the Black Panthers Party to smother the masses. They were Kwani Experience, a band which had been bubbling in Johannesburg’s underground music circuit for a hot minute before being picked upon by a record label, releasing two albums, and somewhat disbanding.

Somewhat, because Kwani’s gone through many phases.

While some members have gone on to pursue other interests, there’s still a core connection which bleeds through different their various musical pursuits, be it on vocalist/percussionst Bafana Nhlapho’s two-step cross-continental wails, or multi-instrumentalist Mahlatse Riba’s explorations into the deeper elements of roots sound as one half of the house music project Sai & Ribatone.

Kwelagobe Sekele, Kwani’s emcee who now performs as the P.O. Box Project, has recently released his Maru EP which he refers to as a “digital Kwani sound” in a Mail & Guardian feature tracing the trajectory of the black band over the past decade.

Maru is the culmination of over six years’ worth of stop-and-start recordings, all the while sharpening that very concept. The initial sessions were with Ribatone, but P.O.’s focus shifted onto other projects.

Work continued in 2012, the same year he shot this video for “Moni” which was c0-directed with Justin McGee. Maru is available to stream on bandcamp. I got in touch and asked him to explain the album title’s meaning. This is what he had to say:

“The silver lining. Because clouds are ALWAYS there, even when you don’t notice them, even when they come and go. That’s my presence in this industry, during this 3-year Kwani Experience hiatus. The title is also an indirect homage to Bessie Head who wrote a book by the same title. This is my little 7 chapter book.

*You can purchase Maru on iTunes

54 Kingdoms: Apparel ‘with a Pan-Africanist sensibility’

As it stands the African Cup of Nations (AFCON) may not take place as advertised next January in Morocco anymore (UPDATE: Equatorial Guinea’s ruling family and its long list of naturalized footballers has stepped in as hosts). One thing we know for sure is there will be cool gear. This summer, while watching the World Cup around the city (in 3 of the 5 boroughs), we kept running into Kwaku A. Awuah (co-owner and President) and Nana Poku (CEO) of 54 Kingdoms, an apparel and accessory company with, in their words, a pan-Africanist sensibility. They were on their hustle, selling their Score for Unity (SFU) range, a series of 3 shirts in the colors of the African countries participating in Brazil 2014. Since then, as their Facebook and Twitter pages show,their business keep growing, including the new University of Afrika (UoA) sweater and henley range. Long after the World Cup was over, we sent them some questions. Below is the email conversation.

Can you say something about your backgrounds? How did you meet? You have a background in fashion?

We were both born in Ghana, West Africa. Nana is from the Ashanti region, and Kwaku has ties to the Ashanti and Central region. We relocated to the U.S in 1997 (Nana) and 2001 (Kwaku), respectively. We lived only a few miles from each other in Accra, Ghana, but it took us almost ten years to meet through a mutual friend, who made the introduction back in 2007.

54 Kingdoms’ roots can be traced back to 2006, when Nana developed the concept in the fall semester of his senior year at Central Connecticut State University (CCSU). “What if there was a clothing line that integrated designs and concepts from the African Diaspora to tell the Pan-African story?,” he wondered. This idea of using the Diaspora as a source of inspiration for designing Pan-African inspired fashion helped in developing the company’s name, 54 Kingdoms. The number ‘54’ symbolized the total number of countries in Africa, and the word ‘Kingdoms,’ signifies that each and every African country is a part of a larger kingdom spanning overseas to include the African Diaspora.

Although, we both didn’t go to a fashion school, it was the desire to create a conscious movement through fashion that led to the official registration and launching of 54 Kingdoms as a company in 2009. The rest as they say, is history.

Can you break down the company slogan, “It’s a Kulture, not a Brand”?

Our slogan signifies the embodiment of the 54 Kingdoms movement. While most companies or individuals focus on building a brand, we sincerely believe in cultivating a lifestyle movement. A lifestyle, that acknowledges the core Pan-African creativity in everything we do.

As we always say, “fashion shouldn’t be just about aesthetics; it should be the thread that interweaves our culture and identity, into the fabric of life that displays the pattern of our pride and self-expression.” We pride ourselves in creating pieces that have educational expressions and can create conversations.

Kwame Nkrumah spoke of a “United States of Africa.” You have decided on “54 Kingdoms”? I know it is symbolism, but monarchies don’t have the best reputation on the African continent.

As students and strong advocates for the Pan-African movement, we honor the ideologies and teachings of Dr. Kwame Nkrumah; one of the most celebrated torchbearers of Pan-Africanism and African liberation struggles.

Even Europe speaks of “continental unity,” although it has fought more wars than any other continent. For us, the question still remains, why can’t Africa speak of and pursue continental unity? The vision for a United States of Africa ignited by Nkrumah should not be mistaken for monarchical exploitation, and must be clearly understood. Nkrumah made Ghana the base for every movement that fought against colonialism, but he also knew that a strong Ghana didn’t necessarily mean a stronger Africa. Hence, at Ghana’s independence celebration on March 6, 1957, Nkrumah said, “Ghana’s independence is meaningless, unless it’s linked to the total liberation of Africa.” After all, what is the point of Ghana’s independence if the remaining African countries were still colonized? It was all about putting the continent first.

These are the same principles that govern our work here at 54 Kingdoms. We are both Ghanaians, and could have focused on telling Ghanaian stories through fashion. Instead, we are learning from diverse cultures and sharing different stories from the Diaspora. Not only is 54 Kingdoms providing education through fashion, but also connecting and bringing people together. We see this emotional and unified connection at our annual Storytellers in Fashion showcase; we always knew fashion could be much more than what people have been conditioned to accept it to be.

Talk about creative process for the Score For Unity (SFU) collection?

The creative process for our SFU collection was thought provoking and emotional, but overall, an amazing experience. It involved so many unique elements such as the designs on the apparel, the packaging, and official theme song Team Africa, recorded by Congolese-born singer, Rafiya.

We went into creative mode knowing this would be a challenging project, because it placed emphasis on African Unity – a not so popular topic for most Africans (believe it or not). We believed that creating the SFU collection would start a conversation about African Unity, and it proved us right; we ignited a #TeamAfrica movement through this collection.

Some may class you as Afropolitans. What do you think of the idea of the “Afropolitan” which has its own critics and supporters?

The idea of the “Afropolitan” is not new, but may be a more popular term used to describe today’s generation of Africans and people of African descent with a very global outlook.

As we often say, “you can’t see the picture when you are in the frame.” When Africans migrate to other places, we pick up new ideologies and different perspective on things (economics, politics, problem-solving, etc). It doesn’t make us less African, and it sure doesn’t make us better than our brothers and sisters on the continent. Through knowledge sharing, both Africans on the continent and “Afropolitans” can contribute effectively to Africa’s development.

You are Ghanaians of course. How did you make sense of the Ghanaian team’s meltdown during the World Cup? Who comes off the worse in this process? Who are the real culprits?

It is hard to defend the Black Stars’ meltdown in Brazil. There is no excuse; they let the entire continent down. Although, the embarrassment exposed the on-going corruption among top executives from the Ghana Football Association (GFA), the players looked worse in the process.

The top culprit is the GFA; they’re corruption principal, followed by poor leadership and coaching IQ exhibited by our then coach, Akwasi Appiah. We love the idea of African countries hiring African coaches, but each candidate should be examined carefully, and must go through essential trainings to acquire the necessary coaching skills needed to compete on the highest level and most importantly, win.

Finally, since I ran into you at a few places, especially Africa-specific restaurants in Brooklyn during the World Cup, from your experience where is the best place to watch either the African Nations Cup or, now, the World Cup, in the greater New York City area?

Madiba Restaurant (Brooklyn), Buka (Brooklyn), Suite 36 (Manhattan), Mataheko (Queens), Accra Restaurant (Bronx), Les Ambassades (Harlem) and Farafina (Harlem).

* More information: site, Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Image Credits: 54 Kingdoms.

Bienvenidos a Latin America is a Country

Latin America is a Country is a website against the popular idea that everything south of Texas is a huge country called Mexico where everyone eats tacos. The title is ironic, clearly. Mexico is a country, as are Puerto Rico, Ecuador or Argentina. But Latin America is not.

This is an invitation to re-think what Latin America is all about. Is Cuba part of the Caribbean or part of Latin America? Is the Caribbean–from Jamaica to Haiti, to Grenada–part of Latin America? What about Guyana or Suriname? Are all Latinos in the U.S. or Europe part of Latin America? How should Latin America be defined? How has it been defined?

Latin America is a Country is the new member of the Africa is a Country family. This is a space for all of the people tired of the same tropes about Latin America, for those who are tired of being pictured as the continent of drug gangs (we prefer to talk about the U.S. war on drugs) or authoritarian caudillos (some of them, financed by colonial powers). It’s not about Shakira, not about tequila, not about Macchu Pichu as a cool touristy destination.

This is an invitation to open a dialogue from different cultural and political perspectives about that popular concept called “Latin America”.

Pablo Medina and Camila Osorio are two Colombian journalists editing this newborn project. They are both currently studying in New York, a city that was one described as part of the Caribbean by the former novelist Gabriel García Márquez. So if you want to pitch an opinion piece to the website, or a reported story, or just send some ideas for Latin America is a Country, you can email them at .

* Also follow us on Twitter and .

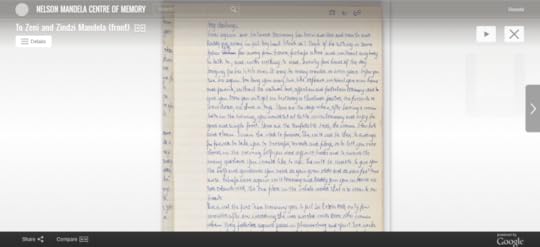

Digital Archive No. 3 – Nelson Mandela Digital Archive Project

This week’s Digital Archive is inspired by Duane Jethro’s recent post on the Mandela Ray Ban Statue in Cape Town, in which he refers to this new art installation as “vandalism of Nelson Mandela’s legacy.” This is just the most recent in a string of excellent pieces which have forced a rethinking of the construction of Madiba’s legacy. Take, for example, Benjamin Fogel’s 2013 piece for The Jacobin, in which he points to the existence of “two Mandelas”: one, “the revolutionary, the lawyer, the politician, flaws and all,” and the second, a “sanitized myth: the father of the nation, the global icon beloved by everyone from the purveyors of global humanitarian platitudes to even the erstwhile enemies of the African National Congress.” The latter Mandela, Fogel argued, “is removed of his humanity and touted as an abstract signifier of moral righteousness.”

The challenge for scholars, then, comes in finding ways to deconstruct the legacy from reality (whatever that really means). One institution which has endeavored to aid in deconstructing Madiba’s legacy is the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory. Founded in 2004, in correlation with the Nelson Mandela Foundation, this organization aimed to “create a public facility to deliver to the world an integrated and dynamic information resource on his life and times, and promote the finding of sustainable solutions to critical social issues, through memory based dialogue interventions.” These aims were furthered in 2011 when the Centre of Memory partnered with the Google Cultural Institute to launch a digital archive.

Arranged along a series of chronological snippets of Madiba’s life, each virtual exhibits presents rich textual descriptions of certain episodes in Mandela’s life, enriched by primary sources, including textual and multimedia sources, that correlate with those chronological spans. Though the site is, without a doubt, incomplete, with large gaps in content for Madiba’s early involvement with politics to his imprisonment, it is an easily navigable and digestable interface. The design is coherent through each of the various sections, allowing the primary sources to be highlighted, providing relevant content while also leaving room for the audience to explore the site more fully through the somewhat hidden digital archive.

The striking thing about the Mandela Centre of Memory is the rich digital archive that it is built on, featuring many historical documents and media that have not yet been incorporated into the storytelling component of the site. In particular, the never-before-published draft of Long Walk to Freedom is available through the archive, providing an inside look into how Mandela (and his co-writer Richard Stengel) viewed himself, especially during his presidential term which, as Fogel suggested, “is glossed over as some sort of miracle period in which he was able to unite black and white; his own political successes and failures in his one and only term go unexamined.” Similarly, the inclusion of a number of Mandela’s journals from his time in prison, some of which have been previously published in Conversations with Myself or A Prisoner in the Garden, helps to get to the core of not only what life was like for Madiba in these trying times, but also, in a way, how he viewed himself.

Getting to the sources, without having to go to the physical site, allows for deeper engagement with the “real” Mandela (or Mandelas, as may be more appropriate); a much needed intervention, if we are to understand the true vandalism of public uses of Mandela like the Ray Ban sculpture.

**This post derives a longer post on my personal blog, published in January 2014, for a course at MSU entitled “South African History in a Digital Age,” taught by Peter Alegi.**

#MyDressMyChoice

On Monday, in Nairobi, a woman walking past a taxi rank was, first, catcalled and, then, attacked and stripped. A passerby videotaped the event, posted it to jambonewspot, and then it went, if not viral, spiral. The men called the woman “Jezebel” and accused her of “tempting” them. For the crime of temptation, she was beaten.

Kenyans have roundly condemned the action. Two twitter campaigns have emerged, the larger #MyDressMyChoice and its sister #StripMeNot. The Kilimani Mums leapt into action, and have organized a protest in Uhuru Park, next Monday, November 17. Here’s their message:

“On November 7th, 2014, a woman was stripped by touts at Embassava Bus terminal.

“This morning we as Kilimani Mums met and decided that we shall hold a peaceful procession to Accra Road on Monday 17th November at 10am. We shall go and deliver a message to the touts who stripped our sister that it is wrong and a woman has a right to dress the way she wants.

“We urge you and your daughters to join and support us. We will meet on Monday at 10am at Uhuru Park and march peacefully to Embassava. This is our chance to stand together as women and deliver a message to our country that sexual violence will not be tolerated.

“All our welcome to this walk- support your sisters, daughters, mothers and wives. join us Monday at 10am!”

From individual women and men to women’s organizations to matatu owners to Deputy Inspector General of Police Grace Kaindi, people have expressed outrage and a determination to do something.

At the beginning of this year, women in Uganda launched the #SavetheMiniSkirt, in response to threats by the national government to criminalize women’s attire. Last year, women of Namibia responded to a similar `national’ urge. The year before that, the spark was a video of an assault on teenage girls wearing miniskirts, at the Noord taxi rank in Johannesburg.

This is not an “African” phenomenon. In 2012, for example, India, Kyrgyzstan, Indonesia, South Korea, Mexico, Nepal, France, and the United States engaged in State policing of women’s fashion. For example, in New York, transgender women, and especially transgender women of color, were routinely stopped, in so-called stop-and-frisk operations. Their crime? Crossdressing.

In the Netherlands, it’s the blackface season. Everywhere else, it’s business as usual, which means, from State policy to mutatu bus stops and taxi ranks to university and grade schools campuses, a war on women’s bodies, autonomy, and integrity by criminalization of attire. #SavetheMiniskirt. #StripMeNot. #MyDressMyChoice.

* Image Credit: “Maggie, Nairobi” by Carlo Alberto Danna on Flickr.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers