Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 382

November 3, 2014

The Politics of Postapartheid Housing

At the heart of apartheid lay the fortification of South African cities as white spaces. Above all, this meant the prevention of non-whites from entering city centers by force if necessary and cloaking this in the rhetoric of legality. A series of key developments in the 1970s and 80s, however, catalyzed a reversal. Most prominently was the repeal of the pass laws in 1986, the set of laws that required non-whites to carry pass books with them at all times and limited their entry into spaces designated as “white group areas.” In the case of Cape Town, designated a so-called “Coloured Labor Preference Area” during this period, Xhosa residents were deemed “migrants” and deported over a thousand kilometers eastward to state-created “homelands” in the Eastern Cape. The systematic underdevelopment of these rural bantustans left many so-called “African” South Africans with little choice but to return to cities in search of employment. As the apartheid state began to shy away from the 1960s and 70s model of forced relocations, by the early 1980s, black residents were able to establish squatter settlements in peri-urban locations around the country, seeking jobs in cities and having no other affordable housing options. This is not to suggest that informal settlements were not already present in urban areas—they date back to the 1890s, and above all, to the period of interwar industrialization—but they multiplied at an unprecedented rate during this latter period.

The sudden lifting of influx controls meant a rapid but delayed urbanization. These residents had been forcibly kept out of many cities since at least the 1930s, and certainly since the passage of the Group Areas Act in 1950. With the transition to democracy in 1994 and the African National Congress’ ascension to power, this immediate proliferation of shantytowns was viewed by the ANC as a threat to its own legitimacy. Mandela’s promise of a million houses within a decade was expeditiously fulfilled, with the development of a massive housing rollout plan in 1994 as part of the Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP). People in need would receive formal 40 square meter houses, called “RDP houses,” free of charge. Even after the closure of the RDP office two years later, these houses would continue to be called “RDP houses,” at least colloquially, and retain this name even today. Every person in every shack settlement in South Africa who I have encountered knows what “RDP house” means, and this is generally the term used to describe state-provisioned formal housing.

Since 1994, more than 3 million such RDP structures have been delivered. As Tokyo Sexwale, then Minister of Housing, famously remarked in 2010, “The scale of government housing delivery is second only to China”.[5] Assuming the average household size of 3.6 people, this means that nearly a quarter of the South African population has been housed under this delivery program. Yet during the same two decades since 1994, the number of informal settlements has increased more than nine-fold. Currently, between a quarter and a third of urban South Africans live in informal housing. This might take the form of informal settlements, or sometimes, as in most of Cape Town’s so-called Colored townships, it means that people erect shacks in the backyards of formal houses and pay rent to the homeowner. Thus the same period during which all of these people were formally housed saw an exponential increase in the number of people living in shacks. Despite one of the most substantial housing delivery programs in modern history, urban informality mushroomed during the two decades following apartheid.

The overwhelming bulk of this can be attributed to late and post-apartheid urban influx, driven above all by the underdevelopment of the bantustans. Frequently too, RDP house recipients illegally sell their homes for a fraction of their value in order to meet immediate needs. If accepting an RDP house frequently requires relocation to a peripherally located site, commuting costs can increase substantially. Given that no transport subsidy is provided and these houses do not come with jobs, they are often sold out of necessity, with residents returning to the same informal settlements and backyards where they were before.

More damningly of the more than 3 million RDP homes constructed between 1994 and 2010, more than 2.6 million of these are at “high risk.” Nearly 610,000 of them need to be demolished and rebuilt altogether, and this is according to the National Home Builder Registration Council’s (NHBRC)[11] own figures. Twice that number have workmanship related issues, which the NHBRC estimates will cost on average R12,000 ($1130) per house. The combined cost of remedying structural defects, minor defects, and non-compliant construction is estimated to be R58.7 billion ($5.5 billion).

The shoddy construction is largely attributable to so-called Black Economic Empowerment companies, in essence private sector startups given nepotistic contracts with no oversight or accountability in the name of some sort of progressive affirmative action. Given the extremely low profit margins in RDP housing delivery, larger construction companies tend to shy away from applying for these government construction contracts, or “tenders” as they are known in South Africa. In other words, the privatization of implementation means that costs are trimmed at the expense of providing durable structures. When the Department of Human Settlements releases a subsidy for an RDP house, the structure ultimately provided by a private contractor must meet a number of national guidelines in terms of size and quality. But with RDP home provision far from a lucrative industry, these companies have every incentive to cut corners.

What began as an attempt to resolve the post-apartheid housing crisis has now actually exacerbated it.

What began as an attempt to resolve the post-apartheid housing crisis has now actually exacerbated it. RDP delivery has reinforced the apartheid era geography of relegation by formalizing peripherally located shack settlements, rendering their far-flung locations permanent. With these houses already deteriorating and residents frequently opting to sell them off, delivery has hardly served as the antidote to proliferating urban informality. Whereas post-apartheid housing protests were initially most common among shack dwellers, cities across the country have witnessed a recent rise in protests by dissatisfied RDP recipients. In Cape Town, these protests have spread across the Cape Flats, from Scottsdene in the northeast to Pelican Park in the southwest. Increasingly RDP beneficiaries are joining the ranks of informal settlement dwellers and backyarders in organizing against the municipal state, the perceived culprit of the post-apartheid housing crisis.

When I visited one such residential RDP development in Cape Town in early June, I encountered houses much smaller than I was used to seeing—they didn’t even seem to comply with the 40 square meter requirement. This development—Pelican Park—is a flagship project for the City, providing countless photo ops for Mayor Patricia de Lille, Western Cape Premier Helen Zille, and numerous other visitors. Ten years in the making, it is the City’s first integrated housing development, meaning that RDP houses, subsidized gap units, and mortgaged housing will exist in the same development. Roughly 2000 RDP houses will exist in Pelican Park when the project is completed in 2017.

Beyond the size of each house though, it was the shoddy construction that was driving recipients of these structures to organize against the City. Residents were beginning to form various neighborhood committees to contest what they viewed as deficient housing. One recipient of a new home, Layla, took me into her new place. I met her when she was still living in an informal settlement just a few kilometers away, but after years on the waiting list, she finally secured a formal structure at the new housing development of Pelican Park just a few months ago. The internal walls were left unplastered and made of large, light gray concrete bricks. If you rubbed the bricks—and not even particularly vigorously—sandy material would fall away. One could easily rub a divot into one of these bricks in a matter of minutes.

“I must make it livable,” Layla told me, pointing to the few pictures and mirrors with Arabic script she’d hung on the walls. I noticed that the molding on the ceiling was actually just white styrofoam glued along the corners. Apparently this was from the contractor—not of Layla’s doing. It reminded me of the so-called “New Tech” houses I’d seen in Delft,[15] constructed almost entirely out of styrofoam. I asked her why the walls were left unfinished, and the floor was exposed concrete. “The company that built these houses said they ran out of money from the subsidy. It was all in the plan, and look how cheap the materials they used were, but now they say they ran out of money from the [RDP housing] subsidy, and so they couldn’t put tiles on the floors, couldn’t put plaster on the walls, couldn’t finish it really. So now we have these houses, and we must make it livable ourselves, they say. But how? We have no money. That’s why we’re in these houses in the first place!”

She took me upstairs. At the top of the staircase, there were two doors. Each led into a tiny room barely large enough for a queen-size mattress—also unfinished. Layla pointed to various cracks that had already appeared in the wall. Granted yesterday was one of the coldest days I’d experienced in Cape Town—there was even a bit of snow in Mitchell’s Plain, an exceedingly rare sight—but it was freezing in there. The walls provided little in the way of insulation, and there were generous “vents” cut through the brick all throughout the house, effectively rendering inside and outside equivalent temperatures.

We descended the staircase again. At the bottom was the living room, with a tiny kitchen in the hallway leading to the front door. There was a small bathroom—again, with very large cracks in the brick—and then another tiny room—the smallest of them all— right next to the front door.

“They have us now on high consumption,” Layla told us, referring to the electricity usage bracket in which each of the recipients is located. Everyone seemed to know the term well. “We’re supposed to be on low, but they have us on high consumption. We don’t even know how to change it. Then there’s the solar geyser they promised us. It’s in the plan—look!” She pulled out the blueprints and official plan for her home, and it was indeed there. I snapped a photo for examination in greater detail later. She also gave me a piece of paper with all of the specifications, but I couldn’t find any mention of a solar geyser there. I saved it for later. “It’s not even the City that’s not giving us the solar geyser—it’s Eskom! They are supposed to, but now they say it’s too expensive. But they have to give it to us!”

Two women were seated in Layla’s living room—one elderly and heavy-set, the other younger and a bit more middle-class in comportment (though also an RDP house recipient). The older woman took me outside. “Look over there,” she said, pointing to a house down the road. “See those men on the roof? They are putting my roof back in. It blew off yesterday, and I just moved in! Seriously, tiles blew right off. In a brand new house? Are they crazy? Go over. You must take pictures.”

Once back inside, the third woman pointed to the walls. “Look,” she said, taking us into the bathroom. “It’s not cement, but just sand pushed together to look like cement. See all these lines, these cracks? In a new house! What’s it going to look like in 20 years? It’s all falling out already!” She pulled out her phone. “I must show you these pictures of my house. Give me your number and I’ll send them on WhatsApp.” She showed me one photo where she’d removed the cover on the light switches, and in the hole behind it, the wall was stuffed with crumpled newspaper. “How is this not a fire hazard? They aren’t supposed to put paper in there, but it was cheaper than real insulation or even concrete or sand. They didn’t even fill it in!” A second photo revealed a sizable crack in the ceiling that was there when she moved in. A third showed a light fixture falling out of the ceiling. “That one they told me they’d fix. Not the crack though.” Layla chimed in: “Now Human Settlements wants to come because we’re meeting. Before they were trying to run away from me, but now they see we’re getting organized.” The older woman joked, “There they busy with my roof,” pointing in the direction of her house.

Between Layla’s house and the older woman’s was the entrance to a small informal settlement. “It’s been here for 24 years,” Layla told us. “Or rather, they were down the road, but they were moved here 2 years ago to make room for some of the first houses. They haven’t been integrated.”

“What? They weren’t included in the Pelican Park project?” Faeza asked. A backyarder herself, Faeza was visiting the project from the predominantly Colored township of Mitchell’s Plain. As the chairperson of a relatively new citywide social movement called the Housing Assembly, she was helping to organize dissatisfied residents in Pelican Park. “No,” the older woman answered. “Four of them did get houses a few months ago. But the rest they say are being moved to Delft.”

“It must be Blikkiesdorp,” Faeza responded. She was nearly moved there herself just a couple of years ago, but refused after visiting the notorious relocation site. “At the end of the day we are humans and not dogs. Did they build these houses for animals?” Layla couldn’t contain her frustration. “It’s not about quality for them, but just quantity. We gonna be hidden too because the bank houses gonna cover everything up.”

***

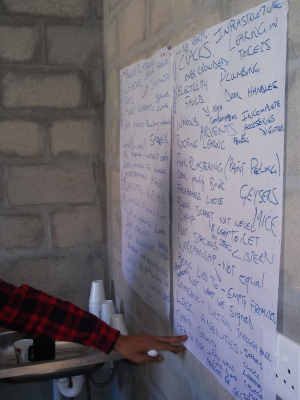

Two weeks later I returned to Pelican Park. Residents had constituted themselves into three committees. The purpose of each committee was to represent RDP recipients in their struggle with the City over the faulty homes. “This is one committee,” Layla told me, “but there are two more. Pelican Park is coming in three phases, and so that means three committees. Each will choose two people, and then there will be six on the umbrella body. That means that six will report back to the Housing Assembly. The rest of the working group is meeting tomorrow.” It was interesting to watch how representative bodies formed in the earliest part of this relocation site. The residents in Layla’s phase of Pelican Park were meeting to form a local committee, and I’d come to help facilitate an interactive workshop on the RDP housing crisis with a few members of the Housing Assembly. We were holding the workshop and meeting in an empty RDP house; the recipient had yet to move in.

Auntie Winnie, one of the women who had been moved from the same informal settlement as Layla, walked over to me. I hadn’t seen her since she lived in Zille-Raine Heights, a small land invasion not too far from Pelican Park. She was mixed about her situation: “This has to be like the happiest time of my life, but it’s like a nightmare.” She’d waited most of her adult life on the waiting list, and here she was with a defective house. She turned to me: “They said they were supposed to spend R100,000, R120,000 [about $9400 to $11,200] on this subsidy, but they didn’t spend more than R40,000 [approximately $3750]. It’s a scandal. Where is the money?”

Winnie disappeared to go make sandwiches while the meeting began. Layla gave the introductory remarks. “I’m an activist,” she emphasized. “Not ANC, not DA. I come from Zille-Raine Heights where we took land because we were gatvol of backyards, gatvol of being on the waiting list, and gatvol of paying rent.[20] They tried to move us to Happy Valley, but we refused.[21] We know that the database don’t actually work. There’s people that’s five months on the waiting list that got a house here. But others 30 years, 23 years on … the waiting list.” She was presumably referring to others in Zille-Raine Heights who did not receive houses in Pelican Park. No one was clear as to how the selection process proceeded.

A few days later, when I interviewed the City’s head of housing allocations, Alida Kotzee, she explained some of these disparities. While typically RDP houses are allocated according to time on the waiting list, “this case was political,” she told me. Then Mayor Helen Zille had personally promised the residents of Zille-Raine houses, and so they named the settlement after her. Moreover, the land these residents were occupying was owned by a nearby school, and so residents needed to be relocated. Thus while generally RDP provision proceeds according to the demand database, exceptions are made in cases of land invasions and other contingent circumstances requiring immediate attention, or else in “political” cases. Zille-Raine Heights was both political and a land invasion. No answer was provided as to why all residents weren’t relocated, but I didn’t press the matter.

Beyond the problem of the selection process though, residents remained dissatisfied with their homes, viewing them as haphazardly constructed warehouses for the poor. “They promised us free-standing, but these are not even semi-detached!” one woman inside the meeting shouted. “They showed us the plans, but these houses are 3 or 4 in a row. It’s all lies, empty promises. We’re being lied to. This is not what we signed for. It’s unhealthy here—unhygienic. It’s like a dirtbin through my house.” More complaints: no sports field or park for the children (as guaranteed in the RDP, claimed Ebrahiem); a lack of amenities—schools, clinics, churches, mosques; there’s no library; safety and security is already becoming an issue, and they weren’t provided with burglar bars.

“How can we afford burglar bars? We can’t! If we could afford them, we wouldn’t be here!” another woman interjected. “It’s a health risk, living here,” added another. “Too many people have asthma to be by these raw walls. Both of my children have asthma. It’s cold, it’s damp.” “And it’s already overcrowded, and we just moved in! I stay by my sister, and lots of families are staying with each other here already. I stay in a three-bedroom but have to sleep in the kitchen.”

These were residents who had been living in informal settlements or in backyards, many without electricity. On my last visit to Zille-Raine Heights, people were cooking over an open fire in the middle of a field, and some of the shacks I entered had dirt floors and low ceilings. These RDP recipients’ standards were not high, yet here they were, organizing a neighborhood council in order to contest the delivery of houses they alleged were substandard and in some cases, already falling apart.

This crisis of delivery in post-apartheid Cape Town is hardly an aberration, but mirrors experiences in municipalities throughout South Africa. The fact that the majority of RDP houses are substandard or pose health and safety risks only two decades after the program’s inception is obviously alarming. But even more significant is the fact that rather than mitigating the demands of the post-apartheid housing crisis, RDP delivery appears to actually accentuate them. If delivery began as a means for the ruling party to both control rapid urban influx and shore up its own legitimacy, the current delivery regime has resolved neither problem. Above all, deficient delivery only intensifies anti-state politics. Far from placated recipients removed from the rolls of the waiting list, residents remain incensed, dissatisfied, and above all, organized against municipal governments.

When analysts write about the recent spike in service delivery protests across South Africa, it is frequently presumed that delivery will conciliate residents and dissipate this “rebellion of the poor.”[24] In other words, delivery and protest are typically viewed as antithetical. Yet as the case of Pelican Park demonstrates, recipients of the ultimate service—free formal housing—are far from satisfied. Rather than the endpoint of the post-apartheid urban crisis, deficient delivery reproduces it anew, accentuating discontent in the process. Residents’ names are scratched from the waiting list and from the municipal state’s perspective, these cases are considered closed. But for relocated residents, this is simply the continuation of their struggle for access to decent housing. Removal from the waiting list without the receipt of houses that they consider tolerable is akin to dismissal and marginalization—far from the “progressive realization of the right to adequate housing” guaranteed by the post-apartheid Constitution in these residents’ book.New home recipients meet to discuss the common problems they are facing with their recently obtained housing in Pelican Park, Cape Town.

Photo Credits: Zachary Levenson.

* This piece originally appeared in The Berkeley Journal of Sociology, Volume 58. The original post includes footnotes.

WOW! Watch this little girl name the presidents of 30 countries

Some people think that Africa is a country. Some people, such as the New York Times editors, think that Ivory Coast is two countries (see below). Many people struggle to name prominent politicians in the countries where they live. Zara is not like any of these people.

She is a little girl who can name the presidents of Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Uganda, Ethiopia, Mali, Sudan, Republic of Congo, Botswana, Gambia, Tanzania, France, Angola, Kenya, Ghana, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Namibia, Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Brazil, Portugal, USA, Russia, the Philippines, China, Colombia, and Argentina. Plus Joe Biden.

She can probably also name all the people who’ve pronounced themselves president of Burkina Faso in the last three days (but for that you’d need a considerably longer video). She does name Blaise Compaore, so this was filmed before the uprising there.

Zara for president!

She’s well ahead of the New York Times, who recently abolished Liberia in favour of a second Ivory Coast.

Like the New York Times, CNN could certainly benefit from having someone like Zara on staff — she’d never have let this kind of thing past on her watch.

The reality of the conditions for farmworkers in South Africa

It seems that no music video in the history of South African music, has attracted as much controversy as the Cape Town hip hop collective Dookoom’s “Larney Jou Poes,” which loosely translates into English as “Boss, you’re a cunt”.* In the two weeks since its release, it has attracted over 50,000 views and inspired innumerable op-eds, mainly in response to the accusation made by the opportunistic far right-wing Afrikaner lobby group Afriforum, that the video was racist hate speech. The video shows Dookom frontman and OG Cape Flats rapper Isaac Mutant leading a group of angry farmworkers on a tractor, and culminates in the word “Dookoom” being burnt into the hill of a farm.

A video showing farmworkers clutching guns, farming implements and the burning of the band’s name into a hill seems rather tame in the world of hip hop. NWA made Fuck the Police in 1988, and the ante has only been upped since then in terms of violence, graphic sex and drugs.

There are innumerable hip hop tracks that contain threats of violence, boasts about cocaine sales and references to real world violence, all of which are free to see in South Africa, and that Afriforum, who most likely didn’t know what hip hop was until they saw the video, didn’t call to ban. Why, then, is there such an overreaction to Dookoom’s video?

The answer of course originates, like so many other things, in South Africa’s history of race relations. Despite the long history of the white minority screwing over blacks in South Africa since 1652, as Isaac Mutant points out in the song, there has been a carefully planned effort to re-brand us whites as the true victims of South Africa’s history – particularly Afrikaans farmers. By drawing on the imagery apocalyptic fantasies of natives rising up against the colonizer in a frenzy of bloodlust that pervades the colonial imagination, right-wing lobby groups have been able to spread a myth of an ongoing campaign of violence and genocide directed by blacks with the covert support of the ruling African National Congress against white farmers in the international media.

This campaign has seen groups, who essentially have separatist and borderline fascist politics that call for an Afrikaner homeland as a form of returning to the good old days of apartheid, go through a process of re-branding in which they disguise their racist politics in the discourse of human rights.

At one level, they have quite successfully adopted the language of “minority rights” from the domain of United States politics. This language can be quite easily used to shift the focus from the legacy of slavery, colonialism and white supremacy to giving “minorities” a seat at the table. At the next level, these groups claim that attacks on Afrikaans farmers are at a genocidal level and form part of a grand plot. In this they have adopted the genocide discourse, which has becoming increasingly popularised in international politics following the Rwandan genocide. White genocide in South Africa is mythical; the evidence suggests that the murder rate among South African whites is comparable to that found in Europe or the United States, while the country’s murder rate as a whole, despite have significantly decreased since the late 90s, is far higher than the world average stand at 32.2 per 100 000. Most murder victims are black males.

This myth is used to portray black anger, particularly directed towards the question of land reform, as essentially criminal in nature and beyond the pale in a democratic South Africa. Lobby groups such as Afriforum style themselves as a human rights group, when they simply are another obstacle to economic transformation in South Africa.

But back to Dookoom, on the 4th of November 2012 in De Doorns, a town on the outskirts of the Great Karoo desert, just off the N1 (the national highway that connects the cities of Johannesburg and Cape Town), a number of grape pickers refused to work. This set off a wave that quickly spread beyond the confines of the town across the Boland (the fruit- and wine-growing area of the Western Cape,) in which thousands of workers joined a wildcat strike demanding a new minimum wage of R150 a day. I was covering the strike as a journalist at the time.

The strike did not originate, contrary to the paranoid insinuations of the Democratic Alliance, the centre-right party that governs the Western Cape, in the machinations of an ANC determined to win back the one province not under its control. It began with a group of workers at a single farm in De Doorns, mostly women, sick of a system that is best described as an updated version of feudalism persistent in the farmlands and the “hunger loan” of R69 ($5), as workers described it to me. Workers sick of the racist paternalism of white commercial farmers, workers sick of not having money to feed their kids or send them to school, and the entire legacy of the 1913 land act – the culmination of a historical process of the dispossession of black South Africans of their land.

In a sadistic, co-ordinated response to the striking farmers – particularly in Robertson – farm owners are ensuring that their colleagues will not hire so-called problem workers who they have dismissed after the strike, saying the financial burden of the new minimum wage is coercing them into restructuring. Many workers have simply not received the new minimum wage at all as farmers desperately applied to the department of labor for an exemption from paying the new wage, relying on the lengthy nature of bureaucratic processes to buy them a window to co-ordinate a response to the strike. Other permanent workers have been fired only to be rehired as casual laborers, often through labor brokers, and farmers have increased their efforts to scour remote places such as Upington in the Northern Cape in an effort to secure cheaper and more placid workers.

The agricultural sector is notorious for being of one the most difficult sectors for unions to organize due to the seasonal nature of employment for many workers, the sheer distance between workers on different farms, and the very nature of the relations between farmers and permanent workers. Most permanent workers live on farms and many are from families who have lived there for generations. Farmers often refer to these workers as being part of what they call an extended family, despite the starvation wages that are the norm in the sector.

Farmworkers are locked into a relationship in which they are dependent on farmers not only for their accommodation, but for the necessities of life – from children’s school clothing to fuel for keeping their homes warm during the winter. While farmers often consider their support for these necessities indicative of their longstanding charity and generosity, they ignore the fact that workers are dependent on their goodwill in order to survive because wages are far below the cost of reproduction.

Workers’ dependence on farmers for accommodation and what farmers call charity is now being used as a weapon of retribution in the aftermath of the wage increases, just as it was used coercively to discourage workers from taking action before the uprising. The insidious character of the relations between farmers and workers is further underscored by the perpetuation of such abominable practices as the infamous dop system – paying workers with cheap alcohol instead of money.

Another coercive practice occurs in the form of micro-credit made available to workers through farmers, either through shops run by farmers on their properties or through small loans given to workers to help them make ends meet. These loans lock workers into a perpetual cycle of debt as they are forced to spend a significant percentage of their monthly earnings on repaying their employer. This is on top of the rent, water, and electricity workers already pay to farmers.

After the uprising, farmers retaliated against workers who participated in the strike and their families by retrenching them, justifying this move by citing the financial burden of the the new minimum wage and the workers’ participation in an ‘illegal’ or ‘unprotected’ strike. Of course, it would have been impossible for them to have participated in a protected strike, because less than 10% of workers in the sector are unionized.

Farmers then raised the rents of workers’ accommodation, often by over a 100%, and threatened to evict those who couldn’t pay. Some began to force family members who didn’t work on the farm to pay rent for the first time. Others threatened to evict dismissed workers, claiming they needed to make space for new employees. Many permanent employees have been fired and rehired on a temporary basis, forming part of an increasing casualization of the farm workforce. For example, over 60 CSAAWU (Commercial Stevedores and Agricultural Workers Union) members, many of them women and union leaders were dismissed in the aftermath of the strike. Furthermore, most of the retrenched farmworkers have been blacklisted, meaning that other farmers refuse to hire them.

The quality of the farmworkers’ houses is often disguised by a fresh coat of paint or, in some of the farms near Robertson, by solar panels. While these houses may appear comfortable, spacious, and environmentally “correct” to a casual passer-by, they in fact often house eight people in only two rooms and have no running water. The solar panels, giving the illusion of the farmers’ commitment to defence of the planet, are rarely connected, actually serving as window dressing designed to impress rather than as a source of power. Many of these houses are still covered by toxic asbestos roofs.

This paternalistic mentality resurfaces again in the responses from organizations such as Afriforum to the Dookoom video. They claim that because the video violates the tone of civility required to engage in the process of land reform, it should be removed from the public sphere. In other words, because the video presents violence against property and has some nasty words in it, it’s a threat to social cohesion, something needed for the process of land reform. In essence, these groups are attempting to remove the anger at the core of the strike from the discussion, and instead place it into the domain of racist hate speech. Removed from the discussion, of course, are the horrific work conditions that are predominant in the agricultural industry and the poverty wages that continue to be paid.

* “Poes” is a difficult word to translate into English, but essentially it is a strong swear word which means vagina, but if used as an insult, it approximates more to the word cunt and in afrikaans it is considered an insult to refer to “Jou poes” or ‘your cunt’, the ultimate form of this is to talk about “Joe ma se poes” or “your mother’s cunt”.

Latest episode of Radio Netherlands Worldwide’s ‘My Song’ series features politically engaged Senegalese rappers

Fed up with what a group of young Senegalese describe as the state of mind of their society being one of ‘defeat’, they decided to start a collective called Y’en a Marre, meaning ‘we are fed up’. Although they came from all walks of life – a mishmash of musicians, activists and journalists – they had one thing in common: to bring about change in Senegal. One way to do so was through music. So the hiphop component of the collective decided to write the song ‘Dox ak sa gox’, meaning ‘To work with your community’.

The Radio Netherlands Worldwide (RNW) series “My Song ” interviews musicians about their music. (Previous episodes are archived here). In the latest episode of the series My Song, Senegalese rappers Djily Bagdad and Thiat reflect on their song and the work of Y’en a Marre.

For a French interview with Y’en a Marre member Fou Malade, click here

* My Song, the series, is produced by Africa is a Country’s own Serginho Roosblad. It is filmed by Sandesh Bhugaloo and edited by Serginho. Sophie van Leeuwen helped out on this episode.

October 31, 2014

What next for Burkina Faso?

At the moment of writing this post – October 31, late afternoon – the leader of Burkina Faso may be Gen. Honoré Traoré, the army chief of staff, who declared himself president yesterday. It may, instead, be Lt.-Col. Isaac Zida, second-in-command of the presidential security regiment, who has just announced the closure of the borders. By the time you read this post, it is possible that retired Gen. Kwamé Lougué, who was sacked as defense minister in 2003, and whom many protestors and opposition figures appear to trust, will have emerged as leader instead – or some other character yet to be named. The power struggle clearly involves factions of the military with very different interests and degrees of intimacy with the régime of former president Blaise Compaoré, who resigned this morning and has taken refuge in Ghana, and how it will be solved – through negotiation, bloodshed, or otherwise – is the question of the hour.

On Radio Omega, the private news station in Ouagadougou whose internet feed has been invaluable for following this crisis from afar, the host and guests, right now, are engaged in a detailed but somewhat theoretical discussion of the mechanics of a political transition period that one cannot yet be sure has begun. The emphasis is on rules and constitutional arcana: what new texts must be written, who should write them, how should the process be supervised? The speakers are digging into the procedural concerns that take up so much discussion, and occult so many concrete issues, in Francophone Africa. A member of parliament is on the line, saying that as far as he is concerned, the dissolution of the national assembly, announced yesterday, is not of legal effect. Then a surprise call from a top political figure: the head of the opposition, Zéphirin Diabré, with an urgent appeal for protestors to stop looting and damaging property. The host tries to draw him out: “Are you in touch at the moment with the military?” Diabré says he can’t talk about that right now, and quickly hangs up.

As the top of the hour nears, the host asks his guests, point blank: “So who do you think is currently head of state?”

There is a beat, followed by the audible equivalent of a chorus of Gallic shrugs. “Well,” one says, “I’m guessing it’s the chief of staff, and this colonel is acting as spokesman.”

“But the wording of his communiqué makes so mention of the chief of staff, and the way he signs it, in the name of the forces of the nation, makes it sound…”

“True. Perhaps he’s taking over.”

“So would that be a takeover in constitutional terms, or in military terms?”

“Probably in military terms. No one’s talking about the constitution.”

“So it’s a coup within a coup?”

“Let’s call it a coup within an uprising.”

Everyone chuckles, and the show ends. The music break is conscious hip-hop in French, with a live balafon. After a public service announcement about keeping Ouagadougou’s streets clean, and then some ads, a reggae track comes on. Its chorus is the revolutionary slogan that Capt. Thomas Sankara installed during his three years of inspirational rule, before his friend and deputy, Compaoré, killed him in 1987: “La patrie ou la mort, nous vaincrons.” The slogan has been all over the streets of Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso these last few days of mass protest, ushering Compaoré out after 27 years of reign.

Everyone loves a good popular uprising, especially one that unseats one of Africa’s more dinosaur-like presidents, who was in office much longer than most of his people have been alive – Burkina Faso’s median age is 17 – and who wanted to cling on by forcing through a constitutional amendment that would let him contest yet another term. That classic technique doesn’t wash the way it used to. Thomas Sankara remains a hallowed pan-African figure, too, and to see people power in Burkina Faso overthrowing, at last, the Brutus figure who ended his experiment in liberation politics is a stirring image. The surprise effect can’t be overlooked either: really, it is only the Burkinabè people and a small number of outside friends and observers who had any sense of the momentousness of these protests. Distracted (and overstretched) by the Ebola outbreak and the Boko Haram crisis, very few international outlets had reporters in Ouaga for the events, and reporters trying to hurry there now are apparently having trouble getting visas.

One who was there, the Reuters photojournalist Joe Penney, has filed a series of images that not only show the massive scale of the demonstrations and the customary confrontation of protesters and riot troops, but also capture a bit of this romance. One is an instant-icon image of protesters in motley gear – military berets, button-downs, one guy bare-chested holding up a set of speakers, another giving the finger, and one in a classic Public Enemy T-shirt – posing on the set at the just-taken-over state television headquarters (see top of this post). Beyond the sheer effervescence and punk-rock energy of the scene, it’s also a brilliant pastiche of the familiar coup image, where too many soldiers crowd into the frame while one of them reads out a ponderous communiqué suspending the constitution and civil liberties in the higher interest of the nation. But a few hours later, it was precisely such a scene that unfolded at army headquarters, as the declaration naming Gen. Traoré president was read. The six hours or so between those two moments, in the afternoon of October 30, signaled – even as an #AfricanSpring hashtag began to float in social media – the Burkina Faso uprising’s inevitable tilt from romance to Realpolitik.

What happens now? By the time you read this post, the plates will have likely shifted again. But there are several classic scenarios, all of which, for now, seem to point toward a military-run transition of some kind. Constitutionally, the speaker of parliament is supposed to take over in the event of “vacancy of power,” but the constitution seems to be out the window. A high-stakes negotiation is almost certainly under way among military factions that harbor deep resentments toward one another and an opposition that will struggle to stay united. (The smart move for Diabré and company may be to let whatever is happening between Gen. Traoré and Col. Zida play out, then deal with the winner.) Compaoré, from his exile in Ghana (or wherever he goes next) may retain some indirect influence through certain military channels, and he has interests to salvage. The regional organization ECOWAS has been missing in action – to say nothing of the African Union – but it is very likely that presidents of neighboring countries such as John Dramani Mahama of Ghana and especially Alassane Ouattara of Côte d’Ivoire, whose camp has many close ties in the Burkinabè elite and military, are weighing in discreetly. The involvement of the French and American ambassadors is a given.

In the last decade, Burkina Faso has become a central node in the new security apparatus that France and the U.S. are building, separately but in coordination, in the Sahel region, to combat jihadi movements and buttress their other interests. Ouagadougou is a base for U.S. drones as well as French special forces. As fluid as the current situation may be, nothing in the power struggle under way appears to threaten Burkina Faso’s fundamental alignment with France and the U.S., and both powers are likely actively working to shape an outcome they can work with. In recent weeks, France had already signaled readiness to see Compaoré exit the scene (a letter from François Hollande promised Compaoré French support should he seek to exercise his talents in some international organization); reporter Nicolas Germain of France 24 told me today on Twitter that French diplomatic sources had commented to him that Burkina “unlike some countries, has a credible opposition.” As Germain commented: “that says everything.”

There is no need to temper the genuine joy, in Burkina Faso, that Blaise Compaoré is no longer head of state. But hope for a more radical kind of upheaval, of a progressive and pan-African nature, is likely to be dashed. And the grassroots activists of Ouaga and Bobo, who have chosen as emblems the broom and the wooden spatula used to prepare the millet dish tô, know that their chores in the national household are far from over.

(Photo by Joe Penney/Reuters. Follow him on twitter.)

Hipsters Don’t Dance Top 5 World Carnival Tunes for October 2014

The October edition of Hipster’s Don’t Dance’s monthly chart on Africa is a Country is here! Check it below, and be sure to visit the HDD blog regularly for all their great up-to-the-timeness out of London.

DJ Olu x Bance

HKN records has been quiet of late but this debut single from DJ Olu’s up coming mixtape is something special. Channeling The Invasion (Bay area production crew) this is some simple infectious party hip hop.

Sauti Sol x Sura Yako (Feat. Inyanya)

Recent MTV EMA winners Sauti Sol teams up with Inyanya on this latest single. Sauti’s win was quite impressive bearing in mind that they were not even in the original ballot.

2face Idibia x Diaspora Women (Feat. Fally Ipupa)

Where to being with this. It’s catching but looking at the lyrics for longer than 3 minutes leaves you perplexed. Is he saying it’s good or bad, we can’t really figure it out. I can say my barber loves it.

Yola Araujo x I am (Feat. Fabious)

First of all it’s not the evergreen rapper from Brooklyn. Instead this breezy and seductive kizomba jam from Angola is making waves across the continent.

Papetchulo feat. Sandokan – Você Tem Swag

Sometimes you just really mis that era when Timbaland and Danja made exciting fresh pop music and you can’t help but enjoy hearing it in new forms.

Zombie Harlem: Drummers Requiem on 125th Street

I never understood what Gil Scot Heron was talking about in his song “New York is Killing Me” (from his last studio album I’m New Here) I understand now, it means that people so loved, admired and coveted his genius that they smothered him to death. The uniqueness that is the Harlem of yore- from the Renaissance, Duke too Hip Hop; this almost magical cultural phenomena of Harlem’s past, has ironically conjured this enormous possessive fetish by the hum drum wealthy. Bringing nothing but accumulation to Harlem’s cultural table. Buying Harlem’s magic, and vicariously wallowing giddy – through this association. Thus, the smothering ensued, and Harlem bespoke, “ Rich folks are killing me (New York).”

The decade rage of upwardly (white) mobile folks, and the already up there extremely rich, include a few folks of African/Latino descent (empire has always had its partners), precipitated large displacements of former African-American/Latino residents of Harlem. Economics (Americana) translation: racial discrimination…

Generational cultural continuities were consequently disrupted. The imaginative heartbeat of the community faced by the onslaught of a HIV, crack epidemic, Police & Guliani combo, good credit, high rent, and that masquerade (aka gentrification) just disappeared. The very same group who would ensure Harlem’s position of sophistication, pushing New York’s self esteem as the cultural capital of the world stood. The present day’s Langstons, Mckays, Wrights, Blakeys, Coltranes, Cruzs, and Chano Pozas, etc. Whatever; magical the name Harlem conjures in the imagination when summoned forth by the lips of any human. Harlem is now anywhere USA, the Same.

On the now famous 125th Street strip, way before you reach the Adam Clayton Powell Jr. block, while still enmeshed in the throngs of overtly urgent New Yorkers (plus the less urgent yet overwhelming tourists),

A nation of mad people, all engaged with the I, giggling, laughing and talking to themselves.

You can hear the sound of an orchestra of drums; way before you see any drummers or drums. Soon you encounter an almost jarring displacement of ancient figures seated around the base of a statue hypnotically transfixed in the moment. Ancient might as well be! Anything past the millennium that way, is ancient history in our grand new (microwave) world of the I – pad, the I – phone and mainly I, I – infinitum ad nauseam self(fie) aggrandizement.

Oh excuse me, lest we forget, The I – watch the Kardarshians*

The master drummers, for the most part, male, are truly figures from the past in their eccentric oddity, when juxtaposed with the Starbucks paper/plastic cup wielding sea of humanity. This frenetic sea of banality, pass bye, clip- by the clip of light changes. From white to orange holding them from either going past the drummers to the nearby stores like H & M or the other way where the Grand old refurbished Apollo is smack in the middle of the block between a Starbucks at the end of the corner and the Banana Republic. The drummers, and their sounds from the djembes to the modern congas, and a variety of percussive instruments, stare down the oblivious crowds on their long march in step with “progress,” taking in the scene in a microwave Instagram momentous scan. They are plugged in and “out” on their iPhone™, talking incessantly along with the rest of the republic, at arms length and far from physical life form.

They represent in the figure a time lost to corporate likeness. A wasteland of sameness, empty (almost) and lifeless, they appear as an apparition in their almost eccentric clothing, all individual and unique, faces forlorn in this midst of this time; where there is a journey of singularity yet they symbolize collectivity in their gathering. The gray underneath the cuffes, drum the rhythms of liberation ironically sequestered at the base of the statue of Harlem’s own son of the soil Adam Clayton Powell Jr. His figure appropriately has its back toward the large concrete sterility of the federal building. Symbolically emphasizing this hostility in concrete the large grounds are hostile in their bareness of trees, shade from the Sun in the summer, or covered places in the winter.

The drummers drum and play, while Adam looks far off into the horizon, one step forward, coat tails unfurled. An almost leap into the optimism he can see in the Horizon for the future of African Americans and all humans as a result. It is as if the drummers find this spot at the base of this statue as the only plausible space to play a daily requiem to: Harlem, Black internationalism, Pan -Africanism, American citizenship. These are all lost in the storm of what is, that side of the Millennium.

The urbane art set forth too memorialize these significant figures all over Harlem do not lie, as in every good work of art it gives you a sense and the mood of their time. The statues all have in common an empowered individual symbolized in how hostile these places are too the public. More important, the figures symbolize the distinct individual with differing desires and thoughts. Unique and part of a larger whole surely endangered, as they sit overwhelmed by the constant stream of pedestrian traffic who represent a homogenized sameness.

No trees, no thought for seats or places the young and old commiserate. They remarkably are devoid of community, which was then the struggle. In a sense a place where you can chill visually and reach back to great Harlem, but without the public that peopled the struggle, and passion of say the Duke, or Adam Clayton Powell.

* Image Credit: Samater M. Also on Twitter: @canvasraw

The drummers play never looking up.

Zombie Harlem: Drummers Requiem on 125th street.

I never understood what Gil Scot Heron was talking about in his song “New York is Killing Me” (from his last studio album I’m New Here) I understand now, it means that people so loved, admired and coveted his genius that they smothered him to death. The uniqueness that is the Harlem of yore- from the Renaissance, Duke too Hip Hop; this almost magical cultural phenomena of Harlem’s past, has ironically conjured this enormous possessive fetish by the hum drum wealthy. Bringing nothing but accumulation to Harlem’s cultural table. Buying Harlem’s magic, and vicariously wallowing giddy – through this association. Thus, the smothering ensued, and Harlem bespoke, “ Rich folks are killing me (New York).”

The decade rage of upwardly (white) mobile folks, and the already up there extremely rich, include a few folks of African/Latino descent (empire has always had its partners), precipitated large displacements of former African-American/Latino residents of Harlem. Economics (Americana) translation: racial discrimination…

Generational cultural continuities were consequently disrupted. The imaginative heartbeat of the community faced by the onslaught of a HIV, crack epidemic, Police & Guliani combo, good credit, high rent, and that masquerade (aka gentrification) just disappeared. The very same group who would ensure Harlem’s position of sophistication, pushing New York’s self esteem as the cultural capital of the world stood. The present day’s Langstons, Mckays, Wrights, Blakeys, Coltranes, Cruzs, and Chano Pozas, etc. Whatever; magical the name Harlem conjures in the imagination when summoned forth by the lips of any human. Harlem is now anywhere USA, the Same.

On the now famous 125th Street strip, way before you reach the Adam Clayton Powell Jr. block, while still enmeshed in the throngs of overtly urgent New Yorkers (plus the less urgent yet overwhelming tourists),

A nation of mad people, all engaged with the I, giggling, laughing and talking to themselves.

You can hear the sound of an orchestra of drums; way before you see any drummers or drums. Soon you encounter an almost jarring displacement of ancient figures seated around the base of a statue hypnotically transfixed in the moment. Ancient might as well be! Anything past the millennium that way, is ancient history in our grand new (microwave) world of the I – pad, the I – phone and mainly I, I – infinitum ad nauseam self(fie) aggrandizement.

Oh excuse me, lest we forget, The I – watch the Kardarshians*

The master drummers, for the most part, male, are truly figures from the past in their eccentric oddity, when juxtaposed with the Starbucks paper/plastic cup wielding sea of humanity. This frenetic sea of banality, pass bye, clip- by the clip of light changes. From white to orange holding them from either going past the drummers to the nearby stores like H & M or the other way where the Grand old refurbished Apollo is smack in the middle of the block between a Starbucks at the end of the corner and the Banana Republic. The drummers, and their sounds from the djembes to the modern congas, and a variety of percussive instruments, stare down the oblivious crowds on their long march in step with “progress,” taking in the scene in a microwave Instagram momentous scan. They are plugged in and “out” on their iPhone™, talking incessantly along with the rest of the republic, at arms length and far from physical life form.

They represent in the figure a time lost to corporate likeness. A wasteland of sameness, empty (almost) and lifeless, they appear as an apparition in their almost eccentric clothing, all individual and unique, faces forlorn in this midst of this time; where there is a journey of singularity yet they symbolize collectivity in their gathering. The gray underneath the cuffs, drum the rhythms of liberation ironically sequestered at the base of the statue of Harlem’s own son of the soil Adam Clayton Powell Jr. His figure appropriately has its back toward the large concrete sterility of the federal building. Symbolically emphasizing this hostility in concrete the large grounds are hostile in their bareness of trees, shade from the Sun in the summer, or covered places in the winter.

The drummers drum and play, while Adam looks far off into the horizon, one step forward, coat tails unfurled. An almost leap into the optimism he can see in the Horizon for the future of African Americans and all humans as a result. It is as if the drummers find this spot at the base of this statue as the only plausible space to play a daily requiem to: Harlem, Black internationalism, Pan -Africanism, American citizenship. These are all lost in the storm of what is, that side of the Millennium.

The urbane art set forth too memorialize these significant figures all over Harlem do not lie, as in every good work of art it gives you a sense and the mood of their time. The statues all have in common an empowered individual symbolized in how hostile these places are too the public. More important, the figures symbolize the distinct individual with differing desires and thoughts. Unique and part of a larger whole surely endangered, as they sit overwhelmed by the constant stream of pedestrian traffic who represent a homogenized sameness.

No trees, no thought for seats or places the young and old commiserate. They remarkably are devoid of community, which was then the struggle. In a sense a place where you can chill visually and reach back to great Harlem, but without the public that peopled the struggle, and passion of say the Duke, or Adam Clayton Powell.

The drummers play never looking up.

Digital Archive No. 1–The Afrobarometer

A few weeks ago, at the North Eastern Workshop on Southern Africa in Burlington, Vermont, I got a chance to participate in a roundtable on Digital Southern African Studies with Africa Is a Country’s Sean Jacobs. Sean asked me if I would be interested in starting a weekly series on digital African projects and I (obviously!) accepted. So, every week, I’ll be discussing a digital project on an African topic, some based on the continent, some based in the United States, some based in the UK; basically, a lot of really cool projects from all around the world that are working to make more resources about Africa’s past and present available for our use!

First up is the Afrobarometer:

The Afrobarometer is a great resource for survey data from 35 African countries. This project has conducted five rounds of surveys since 1999, producing revealing findings about public opinion on issues of key interest to scholars and the general public alike. Run by a consortium of continent-based partners, including the Center for Democratic Development (Ghana), Institute for Empirical Research in Political Economy (Benin), Institute for Development Studies at the University of Nairobi (Kenya), and the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (South Africa), this project aims to conduct regular assessments of social, political and economic opinions in such a way that public attitudes can be tracked over time and provided to policy advocates, decision makers, journalists, and concerned members of the public. The best part about this site is the Online Data Analysis, which utilizes survey data in the archive to produce digital visualizations that allow for spatial and content analysis through a simple interface.

Follow Afrobarometer on Twitter @afrobarometer for their latest findings and news about the next round of surveys.

* Feel free to send me suggestions in the comments or via Twitter of sites you want us to cover.

Digital Archive No. 1 – The Afrobarometer

A few weeks ago, at the North Eastern Workshop on Southern Africa in Burlington, Vermont, I got a chance to participate in a roundtable on Digital Southern African Studies with Africa Is a Country’s Sean Jacobs. Sean asked me if I would be interested in starting a weekly series on digital African projects and I (obviously!) accepted. So, every week, I’ll be discussing a digital project on an African topic, some based on the continent, some based in the United States, some based in the UK; basically, a lot of really cool projects from all around the world that are working to make more resources about Africa’s past and present available for our use!

First up is the Afrobarometer:

The Afrobarometer is a great resource for survey data from 35 African countries. This project has conducted five rounds of surveys since 1999, producing revealing findings about public opinion on issues of key interest to scholars and the general public alike. Run by a consortium of continent-based partners, including the Center for Democratic Development (Ghana), Institute for Empirical Research in Political Economy (Benin), Institute for Development Studies at the University of Nairobi (Kenya), and the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (South Africa), this project aims to conduct regular assessments of social, political and economic opinions in such a way that public attitudes can be tracked over time and provided to policy advocates, decision makers, journalists, and concerned members of the public. The best part about this site is the Online Data Analysis, which utilizes survey data in the archive to produce digital visualizations that allow for spatial and content analysis through a simple interface.

Follow Afrobarometer on Twitter @afrobarometer for their latest findings and news about the next round of surveys.

* Feel free to send me suggestions in the comments or via Twitter of sites you want us to cover.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers