Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 378

November 19, 2014

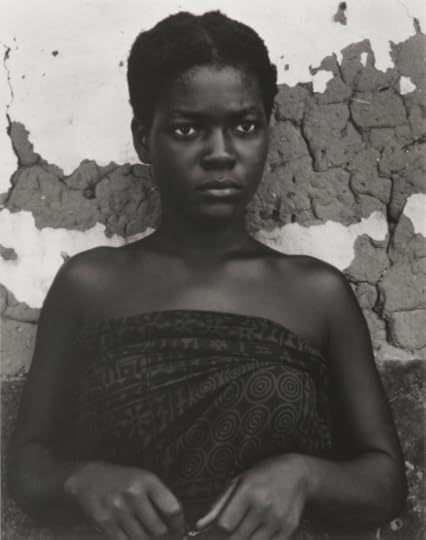

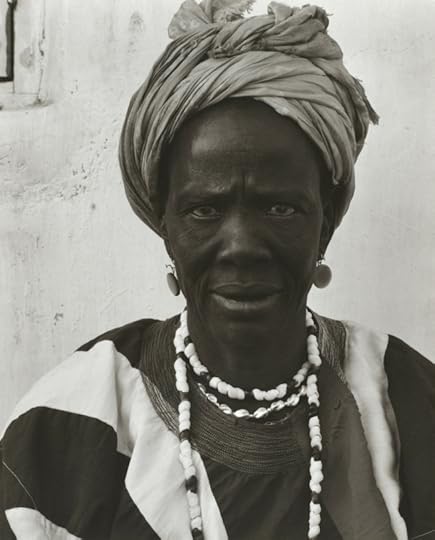

The photographer Paul Strand’s 1960’s Portrait of Ghana

“The Artist’s world is limitless,” remarked photographer Paul Strand once. “It can be found anywhere, far from where he lives or a few feet away. It is always on his doorstep.”

A photographic icon of the 20th century, Strand was a major advocate for considering photography as a serious art form. His career of more than 60 years is currently being honored at the Philadelphia Museum of Modern Art with the show Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography, which runs through January 4, 2015. Though Strand got his start taking street portraits in New York City, his later years were dedicated to capturing the character of diverse landscapes including Mexico, France, Italy, Scotland, Morocco, Egypt, Romania and Ghana.

With the support of President Kwame Nkrumah, Strand’s last major geographic portrait was of Ghana, where he took photographs over the course of roughly three months between 1963 and 1964. This body of work resulted in the publication of the book Ghana: An African Portrait, which featured a companion text by the great Africanist scholar Basil Davidson. This journey was also captured briefly in the documentary about Strand’s life, Under the Dark Cloth.

The book depicts Ghana as a new African nation of peoples poised for industrial ascension. In his illustration of this theme, Strand produced portraits of students, vibrant marketplaces and technical machinery.

Though he believed in the honesty and objectivity of the camera as an artistic tool, Strand was also well aware of the photographer’s control over their images. Thus, images of technological advancement in the book, are sometimes paired with those depicting traditional cultures and natural environments. While all the images represent the visual “truth” of what Strand’s camera documented, the manner of their juxtaposition implies Strand’s idea of “modernity” comes from a diet of increasing industrial growth and Westernization.

However, it must be said that Strand, throughout his career, took great pains to ensure his portraits of people captured their humanity and their dignity. Unlike some of his Western contemporaries taking patronizing anthropological photographs throughout the continent, Strand’s images identify his subjects by name and often mention their communities as well. The portrait of Anna Attinga Frafra for example, depicts a quiet moment, in which Ms. Frafra rests three books comfortably on her head. An image of such grace could only be taken with the trust of the model.

In the few months Strand spent in Ghana he could not possibly have captured his surroundings with the ease and nuance of Ghanaian photographic great, James Barnor or the newer generation of incredibly talented Ghanaian imagemakers such as TJ Letsela, Nana Kofi Acquah, Ofoe Amegavie and Nyani Quarmyne, yet Strand’s photographs endure nonetheless as windows through the Western lens into the optimism and dignity of post-colonial Ghana.

In Strand’s words again, this time from a 1973 interview:

“The People I photograph are very honorable members of this family of man and my concept of a portrait is the image of somebody looking at is as someone they come to know as fellow human beings with all the attributes and potentialities one can expect from all over the world.”

Afe Negble, Asenema, 1964

Asenah Wara, Leader of the Women’s Party, Wa

Mary Hammond, Winneba, Ghana

Market, Accra, Ghana

“Never Despair” Accra Bus Terminal, Ghana

Oil Refinery, Tema, Ghana

Jungle, Ashanti Region, Ghana

Final Proof that Africa is Indeed a Country

Those brilliant satirists over at SAIH are back with another take down of the never ending quest to save Africa… with a trivia game show that validates this very website’s existence:

As we noted last week, the Rusty Radiator and Golden Radiator awards are on once again. Just as many are taking up the call to save Africa this christmas time, you too can do your part. However, our call to action is for you to hold accountable the Geldof types of the world by helping to choose the winners of this year’s contest. Head on over to the awards website, where you can watch all the videos for both the Rusty and the Golden radiators, and cast your votes for the worst and best in each category.

Of course, one award has already been decided… because the lifetime achievement Rusty Radiator goes to Sir Bob! Many congratulations to you sir. You are one song away from saving Africa!

November 18, 2014

When Jezebel Wanted to make Saartjie Baartman Relevant to Millenials #EpicFail

You know how feminists worry that feminism is dead, and that young women are dismissing the possibility of fashioning powerful, self-directed, and critical subjectivities, and instead framing themselves as idiot sexpots? Because of this fear, publications and online media aimed at reigniting feminism try too hard to cater to the millennial generation, in hopes of drawing them to something better than Beyonce’s team’s ability to co-opt conveniently edited portions of the message of feminism in order to get people to buy her shit. That might explain Jezebel’s attempt to exploit Paper magazine’s cover fetishising the sexual power of Kim Kardashian’s buttocks – and the Kardashian family’s choice to use their female members’ bodies and sexualities to create lucrative careers as twenty-first century courtesans – by comparing it to the exploitation of a Khoekhoe woman who, in the 1800s, was forced to daily and nightly exhibit her buttocks to European audiences.

The article, titled “Saartjie Baartman: The Original Booty Queen”, was written by Cleuci de Oliveira.

First reactions on Twitter:

let me repeat: jezebel published a piece in which the article unironically and without critique alludes to black femininity as “savage.”

— zoe samudzi (@BabyWasu) November 16, 2014

jezebel’s take on Saartje Baartman is the worst fucking thing I’ve read in quite some time. It’s like a paean to imperial feminism. — Teej T (@Halfrican_One) November 16, 2014

Ok. So I read the first 3 paragraphs of @CMEdeOliveira‘s post over at Jezebel. Had to stop when she called Baartman an “illegal immigrant.”

— Aura Bogado (@aurabogado) November 17, 2014

Why did Twitter go nuts after this poorly-researched article was posted? Because Oliveira asserts that like “Nicki [Minaj], and Kim,” Baartman, too, “was already asserting a complicated dignity” and that she was “already demanding our respect [by] building a career with [her] assets.” She declares Baartman had agency (I can’t make this stuff up), and that although “her choice also brought her into a world of immense tragedy and humiliation,” she did choose, and her choices “took her across the world, and offered her experiences beyond her certain destiny as a household maid.” Oliveira further insists, “Baartman chose to perform…would be to continue to victimize a figure who has already suffered too much tragedy in life as well as death.” Just in case you think I’m exaggerating, here are Oliviera’s last words on the matter:

[Baartman] surely had complicated relationships she must have had with the men who oversaw her career; she surely had complex feelings towards the societal anxiety and colonial fetishism that allowed her to be famous in the first place. But what is essential to remember is that she never acquiesced to being treated as property. Within the framework she was given, she was always an agent in her own path. She viewed herself as a performer, not a tool for scientific advancement, nor an educational resource for museumgoers, nor a patrimony of the state.

Again, from Twitter, here’s more. @BlackGirlNerds:

.@JennMJack @Jezebel I’m disturbed this article implies that Saartjie was satisfied with what she was doing simply because she was paid — BlackGirlNerds (@BlackGirlNerds) November 16, 2014

Katy Alexander (@nuthinfunnytsay)

@DanielleBowler @sahistoryonline @Jezebel couldnt read the article. Gross. Saartjie was a slave and not in charge of her destiny. dumb yank.

— Katy Alexander (@nuthinfunnytsay) November 17, 2014

All this nonsense about “choice” and “agency” makes me think of my ENG 204 “Intro to Theory” students who just learnt the terms, and are dying to say that every woman – be they immigrant, Black, Latina, Chicana, undocumented meat-packing plant worker – has the ability to make choices, and if they make choices that are damaging to them (like, for instance, marrying a man for financial safety and legal papers, though he mistreats her), that is a “bad choice”. They, too, like Oliveira, don’t yet recognise the horrific decisions (not choices) people who are subjugated must make in order to survive the terrible circumstances they face within specific historical circumstances and geographical locations. Those decisions reflect, in actuality, lack of real choices, and a limited level of agency. I have faith that my sophomore students will get that by the end of the semester. But Oliviera, a full-fledged journo? I don’t know. And why didn’t Jezebel’s credentialed editors catch her terrible suppositions? Jezebel’s byline for Oliveira states that she “is a journalist based in New York City. She writes about art, culture, and Latin America.” Many blamed her status as an American, and as a “white Latina” for her ignorant suppositions and conclusions.

Jezebel is just going to rewrite history to fit its need for clicks and use a Latina to offset rage. White power is a helluva drug.

— Milky Nova Cane (@NovaeCaenes) November 16, 2014

But one’s origins and one’s current geo-political locations are hardly an excuse. After all, I’m a Sri Lankan-born, Zambian-raised, US-educated brownish woman. I still have the responsibility to do sound research on the material I intend to publish – because thousands may read it, and be informed by it. Even if one person read my erroneous assumptions positioning an exploited woman from the Cape Colony as someone who had the same level of agency as a Kardashian, I’ve done some serious damage.

And that’s what Oliveira did (and what Jezebel allowed to be published on their platform). A more historically accurate history of Baartman: she was a woman who was born in the 1770s “in the Camdeboo, or ‘Green Valley,’ some 400 miles from Cape Town,” whose “people were cattle-herding Gonaqua, a subgroup of the Khoekhoe” (Crais and Scully), who may or may not have known “what she was getting into”. Baartman was subsequently paraded out on view, and European audiences viewed themselves against the savage/colonised other’s bodily difference (expressing itself here as a fascination of savage/colonised other’s buttocks) in order to fulfill their (European) desire to amalgamate their self-view as the “norm”. Given the realities Baartman faced, positioning her as a woman who has as much “choice” in marketing her body and sexuality as commodities – à la Nicki Minaj and Kim K – is a grotesque assessment.

In the most well-researched and up-to-date history of Baartman, Sara Baartman and the Hottentot Venus: A Ghost Story and a Biography, authors Clifton C. Crais and Pamela Scully write:

“Baartman was on the Piccadilly stage six days a week. At night, she performed in private parties at the residences of the elite and in London’s salons. On Sundays, she rode a carriage through town, waving to the crowds like royalty. Her exhaustion soon became apparent onstage. She was cranky, and often sick.

At the very moment before she goes on the ship, and in the months before, she insists she would not go to England without Hendrik Cesars coming with her. . . . But of course, as a poor woman, and as a woman, the parameters of her being able to control her life were quite narrow.” As Baartman reportedly told Cesars’ wife before leaving Cape Town, “Who will give me anything here?”

I’ll leave you with a paragraph by Crais and Scully, one that that all Jezebel-feminists must read, meditate upon, and internalise:

Colonized people survived colonial cultures through dissemblance of their motives and hopes from settlers and slaveholders … Would Sara indeed have considered that it would be politically feasible for her to speak truth to power?

#BandAid30: Have we learned nothing?

Have we learned nothing?! Thirty years ago, the Band-Aid video showed pop stars with 1980s hair raising funds for “Africa.” But it wasn’t for Africa, even though the resulting record featured a guitar in the shape of a continent. It was Ethiopia, and the resulting “documentary” began with BBC clips of starving people lined up for food in a camp, with the usual flies swarming, hollowed eyes, and white doctors being interviewed regarding their plight. The songs, the recordings, the video — all identified all of Africa with these images of helplessness, sounding the call of the “white savior industrial complex”for a new generation. Despite the feel-good super sales of the song, controversy continues around the question of whether the effort did more material harm than good.

Fast forward to today: the just-released remix of the principal song of the 1984 Band-Aid concerts — Do they know it’s Christmas — plays to the same sentiments with many of the same stars (and some new ones, like One Direction) — and has all of the same problems. Again, have we really learned nothing??? The video opens with what was known in the 1990s as “aid pornography” (a term and debate which unfortunately has dropped from the radar screen )– [see my post on the film "When the Night Comes" and Ayesha Nibbe'spost on #KONY2012]– shots of dying people — shots that these stars would never allow of themselves. Then we see them filing into the studio one-by-one in the requisite shades, every move (but looking good, not in the throes of death) captured by paparazzi, then emotionally singing, then holding each other, giggling and smiling after they have done their good deed.

Yes, funds are needed to fight Ebola; yes, people are suffering; yes, it can be good to “do good.” But it is never good to show others’ suffering without their consent, especially when showing them stripped of dignity. And as many of our posts and those of others insist, over and over again, what we need is to target the neoliberal austerity policies that have led to the breakdown of health systems in West Africa as well as other areas of the world (including many parts of the U.S.) — see our recent post by China Scherz as well as others in our ongoing series on Ebola. Representing Africans — yet again — as helpless and without dignity while representing ourselves as knowledgeable problem-solvers (who give up nothing in our attempts to do good) IS part of the problem and NOT part of the solution. We Westerners really should have learned something by now.

*Song titles by the band U2. This post is reposted from Critical Investigations into Humanitarianism in Africa.

November 17, 2014

Books: David Goldblatt’s ‘Futebol Nation: The Story of Brazil Through Soccer’

In his book Futebol Nation, British journalist David Goldblatt explores the history of Brazilian football and how it links to the social, economical, cultural and, especially, political life of the country. As Goldblatt argues, despite its size and except for the recent surge in its economy, in the almost two centuries of its existence as an independent nation, Brazil has not managed to make a meaningful impact in the world stage. Yet, that statement would be completely false in the world of football, where Brazilian teams, players and style have dominated the imagination of international fans for decades. So football is the perfect excuse to go about analysing what it means to be Brazilian.

Futebol Nation tells the story of how football came to be not only Brazil’s favorite sport, but also how it turned into a way of building national identity in a vast disconnected country, a means of political control in an unequal, fragmented and federalist polity, and an endless resource for art, culture, hope and violence for its largely poor and disenfranchised population.

Goldblatt starts his tale chronologically, with the return, in 1894, of Charles Miller, a Brazilian son of a Scotsman, from his education in England. At his arrival at the port of Santos, in São Paulo, he carried a pair of boots, a rule book and a football. A decade later, football was already a craze in Brazil, with Miller’s passion expanding in São Paulo and other Brazilian-Europeans arriving shortly afterwards with a contagious love of the sport to Rio de Janeiro and other major Brazilian cities.

From here on, although he still works in a mostly chronological order, Goldblatt divides his book in themes which he aligns with what he considers to be distinct eras of Brazilian football: first as an amateur sport for the upper class communities of European expats and its descendants; then, as professionalization became widespread (even if not legal yet), as a sport where the poor, or non-white could become, even so briefly, part of the elite; and so on. Goldblatt’s insistence on dealing with themes, rather than describing a mere sequence of events, does a wonderful job of explaining how football is interconnected with every aspect of Brazilian life. But, for those not initiated with Brazilian history and politics, like me, it can get confusing at certain moments, with his jumps back and forward between years, governments and tournaments.

But, as a whole, the book is a well-written, thoroughly-researched and easily-explained version of Brazilian issues–its racism, its classism, its corruption, its violence, but also its drive, its ever-booming cultural production, and its never-fading obstination with its own defeats–all looked at through the glass of the national obsession that is football.

Goldblatt goes deep into the Brazilian press’s archives to show the ambivalence the country has felt towards the sport since its early days, with some commentators arguing that it could highlight and uplift the nation’s spirits, while others treating it as a mere brute endeavor, and yet others dismissing it as an out-of-place foreign fabrication. He also looks constantly at the works of art (music, films, songs, novels) being produced about football at a specific time, thus creating an image of what the sport meant for intellectuals, artists and consumers of mainstream media. Indeed, media is essential to the history of Brazilian football, from the crônicas that filled newspaper pages, to the ritual of hearing matches in the radio, to the rise of TV rights and the conversion of the sport into the globalized phenomenon which it is today.

The book is largely a tension between those in power (politicians, presidents of clubs and the heads of the Confederação Brasileira de Futebol) trying to seize football from above for their own greedy purposes, and those below (the players, the casual fans, the organized torcidas and all the hopeful prospects) trying to make sense of their position inside in a corrupt industry.

These tensions are best exemplified in the stories of Pelé and Garrincha presented in the book. Teammates in the World Cup champions squads from 1958 and 1962 and widely regarded as the best Brazilian players ever, both had very similar backgrounds, but very different fates. Garrincha was born to a working class family in the state of Rio de Janeiro, while Pelé was born in a remote, poor town of Minas Gerais. Garrincha was ostracized because of the various birth defects which flawed his body, while Pelé’s black race was a constant source of discrimination.

Yet, Garrincha would become known as “Alegria do Povo”, “The Joy of the People”: though fantastic in his gameplay, both with Brazil and Botafogo, he always remained a regular, working-class man, a man of the people, never looking for fame, or fortune, squandering what little he had earned to fund his alcoholism. Pele, in contrast, was “O Rei”, “The King”, the quintessential example of using football to “get ahead.” Years after his retirement, he still takes advantage of his image to advertise and create lucrative business opportunities, and he has not been shy in looking for political power, even becoming a cabinet minister under president Fernando Cardoso’s tenure.

Pelé knew how to work his talent for his advantage. As Goldblatt tells us about him: “After scoring [his 1000th career goal in 1969] he ran to pick the ball out of the net and in seconds he was surrounded, then engulfed, by a horde of photographers and reporters. When he finally emerged from the scrum, it was a schmaltzfest. Pelé dedicated the goal to the children of Brazil and took and endless lap of honour in a especially prepared 1,000 shirt. A senator in Congress wrote a poem to Pelé and read it out loud on the floor of the house. Everywhere else in the world the newspapers led with the Moon-landing of the Apollo 12 space mission. In Brazil, they split the front page.”

But Garrincha was clueless and disinterested in becoming a hero, which is why Brazilian media, constantly looking to create and destroy idols, promptly forgot about him, after retirement and until his death: “After another day of drinking cachaça Garrincha was taken to a sanatorium in Botafogo where he had already a number of episodes in rehab. This time he died in an alcoholic coma. Within hours hundreds were gathering at the hospital. The press, who had not written a word about him for a decade, began to publish a torrent of remembrance. a municipal fire engine, like the one that had carried him through the streets of the city with the 1958 World Cup winners, took his body to the Maracanã.”

The book also tells the story of other Brazilian greats, and their investment, or lack thereof with politics, such as Sócrates commitment to the Democracia Corinthiana, and, at the end, succeeds at explaining how football moves Brazil. Such is the case the success of the Partido dos Trabalhadores (Dilma Rousseff’s and “Lula” da Silva’s party), which is partly linked to football and the 2014 World Cup, and such was the case with the 2013 protests around Brazil which coincided with and were amplified by the Confederations Cup held in the country.

Goldblatt asks himself in a coda added in February of 2014, if the movement that sparked those protests can, in a country still plagued by corruption, polarization and inequality, bring forth positive change. But after a successful staging of a World Cup and a new victory by the PT, this yet remains an open question.

* On Wednesday, November 19th, David Goldblatt will give a free talk (open to the public) on the globalization of English football at the Theresa Lang Center (55W 13th Street, second floor) at The New School in New York City. Sign up here for the event. Or see more information here.

Making Azonto: Local Roots and International Branches

As a DJ, having the platform of Africa is a Radio to showcase the music I’m feeling from artists around the world is a lot of fun, and quite rewarding. But, providing insight into the other branch of the music industry I work in, as a producer (creator), is something I don’t do nearly enough of. Partly because the old tradition of musicians relying on journalists to write about our music for us (and paying PR people to make that happen) stubbornly persists. And also because truthfully, self-promotion in this cutthroat social media age is still a bit awkward for me. Still, I often ask myself, “why rely solely on music journalists to get the word out about your work with so many ways to directly communicate with audiences today?”

So, since this platform is a place to delve deeper into various topics, besides taking the opportunity to share the following remix, I thought it would be good to take the opportunity to provide some context behind its creation. By doing so, hopefully I’ll help provide insight, and de-mystify some of what goes into the music production process. Who knows, perhaps writing about making music will become a regular thing over here, and not only for myself but for any artists interested in sharing (hint, hint!)

So here we go:

The above remix is my take on Teleseen’s song Baalbek. The melodies and harmonies of his original were inspired by both Ethio-jazz music, and Brazilian Batucada from Rio (where he and I are both currently based.) He merges the two and takes it into territory that might be welcome on the dance floors of techno meccas like Berlin or Detroit.

For my version, I decided to strip the heavily layered song down to only a few essential instruments, and ended up focusing on one of the several saxophone melodies going throughout the original. From there I decided to concentrate on building my remix around new percussion ideas, instead of harmonic ones. After the saxophone line, the next thing I added back into the mix was the guitar line that hits on the up beat. I foregrounded it and looped the strongest parts so it was continuous throughout the track. Once that was in it reminded me of the emphasis on the up beat of azonto, especially in songs like Sarkodie & E.L.’s “U Go Kill Me.” Expanding on that moment of inspiration, I added a bunch of percussion referencing rhythms prevalent in azonto. I rounded it out by layering the kicks with pitched 808 bass samples to create a new booming bass line, and my azonto-techno remix was born.

The beat for “U Go Kill Me” and many other azonto hits was produced by Ghanian beat maker Nshona. A couple years ago, when azonto was just hitting international airwaves, Benjamin Lebrave pointed Nshona out as one of the main innovators behind the musical style that accompanied the Ghanian dance phenomenon. The mark of his productions is (mostly?) Ga traditional rhythms on digital software such as Fruity Loops. And, I think Nshona’s instrumentals could very much merit the techno signifier on their own accord — making the name azonto-techno redundant:

However, I’m not the only one inspired to take azonto’s exciting energy down a new conceptual path. While the dance itself maybe losing steam in its home base, several producers outside of Ghana are still attempting to push it in new directions. A quick Youtube search reveals several takes on the idea of azonto-techno, each of which are quite unique.

One other example that is rather close to home for me is the Rasta Azonto Riddim, an instrumental by Kush Arora that uses dark synth sounds influenced by industrial music. My label Dutty Artz released an EP of the song with two accompanying vocal versions this past month:

And, as I mentioned before on this site, there has been a noticeable influence of contemporary African Pop on the Caribbean Carnival season this last year. From February through to Labor Day, I’ve been able to witness azonto making its mark on the various Carnival-inspired celebrations around the world.

I’d also be remiss to not mention the experiments of DJ Flex in New Jersey who blends Afropop hits with U.S. East Coast Club music:

Not only interested in morphing azonto with non-Ghanian musical ideas, some folks are interested in exploring the traditions behind the music. Since writing about Nshona for The Fader, Lebrave and his Akwaaba Music label have launched Roots of Azonto, a project that entails workshops and recording sessions in various parts of Ghana — in order to explore and expand the source material for the popular music of the day. By reintroducing “real drum sounds back into the studio” he, and workshop partners like Max Le Daron, aim to expand Ghanian producers’ vocabulary, and at the same time document, and thus help preserve Ghana’s diverse music traditions:

Now for the shameless self-promotion: My remix of Baalbek is part of the Anamorph Remix EP out on Brooklyn-based indie label Feel Up Records. Kush Arora’s Rasta Azonto Riddim was released on an EP featuring versions by Jamaican vocalist Blackout JA and Zimbabwean Pops Jabu. Follow the Roots of Azonto at the Akwaaba Music website, and Nshona on Twitter. And, don’t miss any of DJ Flex’s great remixes on Soundcloud.

As far as rappers Keur Gui are concerned nothing has changed in Senegal

“You’re heading straight to jail after that song is released” is what 25 year old rapper LDP said to Keur Gui (the house in Wolof) when he heard the lyrics of the track “Diogoufi” (Nothing has Changed) the first single off their new album.

The Senegalese rap duo, Keur Gui, recently released their highly anticipated double volume CD titled Encyclopédie (Encyclopedia). For those who don’t recall, Keur Gui were founding members of the of the Senegalese youth-led protest movement, Y’en a Marre (Fed Up). Keur Gui, consisting of Kilifeu and Thiat is arguably one of the most engaged hip hop acts on the African continent today.

After being away from the scene for a few years, the duo set off a media storm in August when they dropped the single. Thiat’s verse is a somber reflection on the situation in the country. It includes lyrics like: same cats, same dogs/same electoral promises/it’s only two years and we’re already fed up. Kilifeu then enters singing the catchy lyrics to the chorus, which translates to something along the lines of: the way you wake up is the way you will go to bed … You go straight to jail if you dare speak out with the ultimate message being that nothing has changed in the country but the president.

The song addresses the economic situation, power cuts, soaring prices for basic necessities, the selling off of coastal land to international entities, and most controversial, rumors about the interference of the first lady in matters of government. They also assert that current president, Macky Sall, was pushed into power by accident and ultimately has no solutions for Senegal. The track quickly became an anthem for the population. Thiat and Kilifeu were not arrested; however it wasn’t long before they started to feel the ripple effects of their critique as sponsors slowly dropped them. Thiat and Kilifeu were not to be silenced.

Their activism started when they were just 17 years old. Their first album set to be released in 1999 was thought to be too critical of the government especially against President Abdou Diouf and Le Haut Conseil de l’audiovisue (High Audio Visual Council) required that they change four out of the six tracks. The album was in essence censored and never released. Another track directly criticized Abdoulaye Diack, the then Mayor of their hometown of Kaolack for the difficult social situation experienced by its residents. The young duo were beaten by men sent by the mayor, arrested and stripped of their clothes. This is why they go shirtless during concerts, because they say; never again will anyone have the opportunity to strip them.

Keur Gui was not discouraged; they went on to release several albums over the years that tackled a variety of social and political issues. In 2008, Keur Gui returned with Nos Connes Doléances (Our Idiots Complaints)—a French pun of “Condolences”—an album that sought to both entertain and educate. That album led to numerous awards and they became recognized continent-wide for a brand of conscious hip-hop that confronts elements of bad governance and corruption. (Check out “Coup 2 Gueule” (Lets Act on our Words) from their 2008 album.)

Even though they were widely recognized as conscious rappers, Keur Gui rose to another level of international fame as founding members of the Y’en a Marre movement that shook the Senegalese nation to its core when a collective of rappers and journalists joined forces to declare we’re fed up. Since the intensity of the protest movement died down, people wondered how Kilifeu and Thiat would interact with the new government that many imagine they helped to elect. The duo wanted to get back to the business of hip hop and went into the laboratory to concoct an al-bomb they say.

The album was recorded over a five-month period ironically at The House Studios in Washington DC. They emerged with their encyclopedia in two volumes: “Opinion Public” and “Reglement de Compte” (The reckoning). Public Opinion is a reflection on the state of Senegal, the future of the country and their take on continent-wide issues. The reckoning is a classic hip hop battle style album where they aim to quiet those who asked if they are still serious players in the Senegalese hip hop game.

They then released their second single “Nothing to Prove,” which is a classic ego trip song. On this track we see that Thiat and Kilifeau are clearly in sync as they share verses in order to argue that Keur Gui has nothing to lose, nothing to prove. They tell other rappers we fear nothing and have no equals, we never back down. We spit medicine for those in real need. We provide real solutions to problems. They further assert we’re the only hip hop crew that can give the government a deadline and are prepared to sacrifice our lives for the masses that we represent. We gave y’all a break, but now we’re back.

There are tracks for people with all types of tastes. General, a young rapper in Senegal noted, “Public Opinion is for the intellectuals but The Reckoning, wow that shows Keur Gui is the best.” One thing that’s for certain, Keur Gui has maintain their hard hitting, in your face style. The track Dankanfou (Warning) is deceptive with its serene piano and slower flow that draw the listener in. The song is a warning to Macky Sall as Kilifeu starts with, what kicked out Diouf/pulled down Wade/is warming up Macky and later, your grace period is over/life is still so hard. They warn Sall that he did not learn the lesson from the 2011-2012 protest movement but they take it further back by citing Diouf and Wade because youth were instrumental in helping to vote both out of office.

There are also songs like France a Fric that address France’s history and contemporary policies across Africa or No Comment that calls out everyone from Mugabe to Gbagbo. Personal tracks are also incorporated. In Alma Noop (Listen to Me), they speak to the next generation as Kilifeu passes on lessons to his son and Thiat to his imagined future daughter. While in Fima Diar (My History) Thiat talks about his life journey that led to meeting Kilifeu.

Keur Gui fans will be impressed by their evolution as they vary their technical flow; Thiat changes up his rhyme pattern and Kilifeu excels at his rapping/singing hybrid; have hooks in English, French, and Spanish; include a number of collaborations with DC-based musicians especially the Grammy nominated emcee Kokayi; blend hip hop and African sounds with traditional African instruments; and highlight Senegalese beat makers who are represented on 20 of the 26 tracks. Yet they remain true to their roots as they provide social commentary and give politicians and other rappers a lyrical thrashing. The album is a musical, personal, political, and ideological experience.

* The album will be available for purchase online soon. Until then, the author can be contacted about contact information for purchasing CDs. Image Credit: KeurGui Facebook Page (top) and Janette Yarwood.

Why debating and getting rid of Zwarte Piet won’t be a priority in Belgium

Why is the discussion surrounding Zwarte Piet getting far less traction in Belgium than it does in the Netherlands? For me, it boils down to one issue: racism in Belgium is endemic, and it is not taken seriously. Few are talking, and even fewer are listening.

The discussions on Zwarte Piet in the Netherlands have been well documented in foreign and national media. However, it is less known that this blackface figure is also present across the Netherlands’ borders, in Belgium, most notably in the region of Flanders. There are many reasons for the lack of debate in Belgium: the celebrations of Saint Nicholas Day are distinct in each country, and both the Belgians and the Dutch pride themselves on their cultural differences and debates as well as the ways in which their political systems are structured. However, when one acknowledges that Black Pete is just one of a myriad of symptoms demonstrating a discriminatory society, it raises red flags about how Belgium deals with racism.

In Belgium, the past few months have been littered with racism scandals: endemic racism was recently exposed within the Antwerp police corps, a national newspaper depicted Barack and Michelle Obama as chimpanzees, and then there’s Theo Francken the recently appointed minister of migration and asylum. Francken, from the right-wing Flemish-nationalist party the NV-A (the New Flemish Alliance), which dominated the last election, called into question the economic validity of the migration of African migration on his Facebook page. Immigrant groups are now calling for a national stay away on 19 December to protest his remarks. After an initial outcry, the debate about his remarks quickly died down.

What is interesting in these cases is how quickly and superficially they pass. When a leading and otherwise respectable newspaper pictures the president of the United States as a monkey, a short outburst and a quick apology cannot suffice. When that same newspaper a few months later allows one of its major football commentators to spout ignorant so-called “facts” as to why an “African team” can’t make it to the finals (I quote: “because they can’t focus on the goal for more than six weeks at a time”) it happens again, minus the apologies. In 2010 when the DRC celebrated 50 years of independence the most prominent figure on Belgian television was Jef Geeraerts, an ex-colonial administrator and writer known for anti-women and neo-colonist views.

Why are these matters laid to rest so quickly? Belgium has not had a real debate about its colonial past and most of this history is not part of the country’s collective memory. It is not properly taught to children nor adequately represented in the media.

Until recently migration from sub-Saharan countries to Belgium was mostly sporadic and short term. Since the late 1980’s larger numbers of people, predominantly from the DRC began to settle. Migrant communities have been hesitant to respond to flagrant discrimination and remain divided among themselves. As a consequence, in broader national debate, dealing with racism—especially the less overt kind—is not seen as important.

Another very important reason why you can’t mention the R-word is the development of Belgian politics. In the early nineties the popularity of the right wing and overtly racist party Vlaams Blok (VB) soured. At the time the word ‘racist’ became synonym for referring to someone who “votes VB.”

People didn’t have to look in the mirror anymore: as long as you were against VB you didn’t have to think twice about your own views or behaviour. The VB over time has all but disappeared (although many people from the party joined the NV-A) but racism has not disappeared with it.

This has left us with a difficult inheritance to deal with. Our overwhelmingly white and male political system and media have left us without a forum and discourse in which we can speak about racism. Political correctness has become a swear word and claims of racism are easily swept away as irrelevant or “not fun.” In this context debating and changing a phenomenon like Zwarte Piet will never be a priority.

The Kenya Art Fair

Over the past few years, artists like Michael Soi and Cyrus Kabiru placed Kenya on the global visual arts map. The first Kenya Art Fair is part of this move.

From November 6 – 9, 2014, the Sarit Center Exhibition Hall in Nairobi’s Westlands area was the epicentre of this vibrant art fair. Organized by Kuona Trust and sponsored by the Go Down arts centre, Pawa 254 and the Nation Media Group, the Kenya Art Fair gathered personalities from the national art scene to debate and build a stronger artistic movement through discussions and exhibitions. The exciting encounters between artists, gallery owners, collectors, art lovers and curious people has nurtured new and future collaborations.

Participants included Abdi Rashid Jibril from Arterial Network, Danda Jaroljmek from the Circle Art Agency, Elisabeth Nasubo from the Ministry of Culture and many creators like the performance artist Ato Malinda and the master cartoonist Gado. The diverse line-up of panels such as “digital art”, “the role of Kenyan government in supporting the contemporary visual arts sector”, “cartoon and comic strip”, “art and business” and “the visual artists challenge” offered visitors tantalizing choices. The talks have been a space for the exchange of ideas and debate thanks to broad audience participation.

Admission was free, and the organizers estimate that over 5,000 people visited the Fair. According to Kuona Trust director Sylvia Gichia, even the First Lady Margaret Kenyatta took a stroll through the art fair to show her support for the art world.

But Kenya still faces challenges within the arts sector despite the Fair’s evident success. Questions Kenya’s artists must grapple with include how to ensure art is not only for the elite, what distribution models can benefit artists who are not represented by agencies or galleries and how to use digital platforms to promote and sell art at a fair price. The creators of the Fair will also have to determine whether it will now become a regular occurrence, like the Dak’art in West Africa or the Joburg Art Fair in South Africa, or model itself the recent successful 2014 Kampala Art Biennale in Uganda.

Whatever the case, the Fair has made its mark. Art lovers, take heed – keep your eyes on Kenya.

* Art by Eric Muthonga (“The Westgate Attack”). Video by Sebastián Ruiz. This post is part of a partnership between Wiriko and Africa is a Country.

Soweto Punk Revolution: The Cum in your Face

Someone told me that interviewing a punk band from Soweto–an urban settlement, the country’s largest, created in the 1930s to separate blacks from whites in Johannesburg, South Africa–is a stupid idea. “Black people playing punk? Is it mixed with kwaito or what?” I tried to explain that the ever-mutating punk mind-set is apt for anyone eager to stir things up, anti-establishment, equality and free thought, a revolt against the snobbish bourgeoisie. Hence, a dirty-riffed “fuck you” couldn’t be more fitting in a society, which lets its president get away with building a tax-funded “safety pool” when a quarter of the nation is unemployed.

Hell-bent to challenge this non-believer, I set out for Johannesburg to attend Soweto Rock Revolution–Punk Fuck III. Once arrived, local thrash punk band TCIYF (short for “The Cum in your Face”) made it clear that this has nothing to do with politics at all. It was about having a mad party, and – if one can speak about “the true spirit of punk” – this came pretty close to what one would imagine the DIY-embracing, eccentricity-accepting and obedience-ignoring CBGB’s of the ‘70s to have been like.

There might have been more sun, smiles and jah at Punk Fuck III than at blood-dripping aggro mosh pits in the colder, northern hemisphere, but the spit-hurling anarchy was commonplace. Attracting skaters, stoners and spiked hair, the music at the event wasn’t always strictly Ramones and Sex Pistols, but the attitude certainly was. R15 (about $1,50) Black Label quarts flowed like they were for free; weed was sold through the speakers; fireworks went off under Dr. Martens; microphones were ripped from the stage; band members left before sets started; guitars were stolen and spray cans were brazenly used to propagate feel-good slogans. On top of that, “the fourth wall” – dividing stage from floor – was constantly broken down, creating a welcome unity of fans and performers.

The togetherness started with Matt Vend, who announced that he would play without the amplifier if we don’t mind, when – in true punk fashion – the sound encountered problems. Sing-walking in-between eager listeners, he played a muted acoustic version until a fellow musician figured out what was wrong and kindly plugged him in again. His set was followed by Amber Light Choices, who set up on the floor completely. When TCIYF played at last, there was no more distinction between crowd and band – neither in alcohol levels nor assigned space.

Being part of the SSS (Skate Society Soweto), band members Thula (guitar), Pule (vocals), Tox (bass), Jazz (drums) and Sthe (special vocal guest) are influenced by rock’n’roll and half-pipes, but growing up there were few local outlets for their interests. They took matters into their own hands though, and organised low-key punk and skate jams in the township. The Soweto Rock Revolution, however, only really picked up after they left their home turf to play Punk Uprising and linked up with LeftOvers bassist and manager, Clint Hattingh. He had the right contacts and was able to convince Johannesburg bands to get their asses to Soweto. A small scene, possibly as diverse as South Africa’s people, was born. Our society seems obsessed with putting people in boxes like sorting socks from underpants or crayons from felt pens, yet Punk Fuck III –attended by South Africans of all backgrounds – proved that the exact opposite exists as well.

TCIYF’s show mirrored what the movement’s purveyors have in common: courage, a thirst for rebellion and a carefree nature. The Soweto punk fuckers are loud, ballsey and unabashed. But most importantly, fun as hell. “Who is drunk?” Pule screams before they rip through their songs, so boozed up that Thula slips off the stage and continues playing while leaning against it. In the meantime, a moshing mob jumps on and off the elevated concrete, surprisingly managing to keep cables and equipment intact. It was punk fuck alright, perhaps best epitomised in the drunken band’s words: “Fuck the answers. Fuck the explanations. Fuck the fear. Fuck everything. Just go ahead and just do it.”

Similar to the statement above, our interview – which we managed to squeeze into ten minutes as all TCIYF members were extremely busy organising bands, beer and blunts – was accentuated, somewhat naively, by “fucked up”, “fuck this” and “fuck them” in regular rhythms. Short, but to the point, they made it very clear what they were about.

Unlike Johnny Rotten – who TCIYF dig – all band members agree that they simply don’t care about current affairs. Avoiding all media because it “brainwashes you”, they’re adamant not to vote (some band members don’t even have IDs). “It’s not to shock or to take away any meanings. It’s about what we think at that time. It’s about life experiences,” shouts Sthe, when I ask whether the use of Jesus symbolism in their video to “Church Wine” is just as unconcerned. Insisting that “it did happen,” Jazz adds, “We went to church, drank the wine and ate the food.” I wasn’t completely convinced and wondered if they weren’t kicked out. “No, they saw us with skate boards and said ‘Jesus loves you guys.’ None of our songs are lies, all of them are true. Like ‘Touched by a Boner’ is about touching this girl on the train.”

It shouldn’t be a big deal, but given my pre-party experience, why punk music? “We’re from Soweto but kwaito was way too slow for us, hip hop was way too monotonous… so boring! All they do is say nothing. So we just wanted to do something that was powerful,” says Thula after Sthe simply declares, “Because it’s the shit.” In fact, they see no contradiction in where they come from and the music they create. “Punk was London and New York. How fast are those cities? And how fast is Soweto as a township? It’s all according to the fucking lifestyle. If I lived in Kimberley I wouldn’t be in a band playing punk. There would be no need. I’d be farming or something.”

In punk’s early stages in the US and the UK, the raw, amateur sound was a slap in the face to the commercialisation of music. If the genre had a conscience, its liaison with a capitalising industry of dry-sucking big shots would be a sweat-drenched nightmare. So when I want to know what its future holds in South Africa, Sthe says, “Nobody cares about punk here, so I think it’s safe.” It has withstood some attacks though. According to Thula, they had a contract in front of them but sent profit-making packing when they realised the deal was just about numbers on a bank account. “We were like, ‘You don’t care about punk, you care about the money. That’s why My Chemical Romance is fucked. Even Lamb of God is fucked. Big bands are fucked. Metallica are fucked a long time ago. Everyone is just getting fucked because they are taking the money and forgetting what they are doing.”

Their bling bling-condoning mind-sets fit “the requisites” of the initial movement, which – of course – isn’t new to the African continent. Late ‘70s SA bands like National Wake, Wild Youth and The Gay Marines probably had more balls than the roughest safety-pins-and-mohawk sporting squatters in Europe. And yet – although they deserved all the recognition possible – their bold, politically-charged tunes remained largely underground until Punk in Africa dug them up in 2012. In a sad way, this is somewhat positive. Like feminism bought into smoking, subcultures get scooped up by corporate brands, only to get trivialised, lose meaning and become dishonest. Maybe South African punk’s previously clandestine and currently marginalised nature is exactly what makes it so real.

What’s certain though is that while TCIYF whip out killer riffs, master crude, in-your-face lyrics and are probably the most humble act to see live, they really don’t give a fuck. Even their album, Buddha’s Cum, due December 2014, is recorded by phone. “No overdubs, pedals, mixing and mastering” and it will be given away for free. In a time of sell-outs like Green Day where hypocrisy is a trend and clubs like The Rat turn into “classy” hotels, the priggery-defying anarchy, fearless indulgence and shameless DIY are what make the Soweto Rock Revolution parties spectacular. But what’s more, while The Sex Pistols sacked Glen Matlock because he was into The Beatles, the Soweto scene is definitely less – Johnny don’t hate me! –“exclusive”. I came home with a variety of band stickers and a satisfaction that there are still musicians who hold on to no-profit principles to simply have a blast. And finally – in the cum-fuelled words of TCIYF –“part your lips” because township punk is alive and spitting.

* Image Credits: Christine Hogg.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers