Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 377

November 22, 2014

What’s Driving the Violence Against Latin American Environmentalists?

It was three days before Christmas in 1988. Much of the world—following a blisteringly hot summer—had really begun to worry about rising global temperatures. That night, Chico Mendes stepped outside of his cottage in Xapuri, Brazil only to drop dead moments later.

Mendes, a unionist rubber tapper and environmentalist, was gunned down by a cattle rancher, presumably because Mendes posed a threat to the expansion of cow pastures in the West Amazon and, more broadly, the domination of landowners against the landless, often indigenous poor.

25 years later, and right across the border from where Mendes’ body once lay cold, four pro-poor, indigenous environmentalists have been assassinated. These activists happened to be from Peru, which is currently readying itself for hosting another UN climate summit this December in Lima.

The four individuals killed in Peru hailed from the indigenous Asháninka tribe, which had, under the leadership of Edwin Chota, been preparing to bring a case against illegal loggers to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. According to sources on the ground, it was these very loggers who made sure that Chota would never be able to do that. And rightly so—just a few years prior the Asháninka were successful at blocking a bilateral energy agreement between Peru and Brazil that would install several dams in the Ene river valley and inevitably displace thousands of Asháninka in the process.

Neither Mendes’ nor Chota’s deaths are isolated incidents, but instead represent a growing trend of the forced disappearance and/or killing of environmental activists—many of whom are from indigenous groups—throughout Latin America. Global Witness reports that, from 2002 to 2013, 908 known people from 35 countries have been killed because of their work on environmental or land-related issues, with two-thirds of the documented killings taking place in Latin America. In Peru, 57 environmentalists are known to have been killed since 2002, and over 60 percent of the murders have taken place within the last four years. Of these killings, only ten perpetrators have been tried and convicted for murder.

Approximately 300,000 indigenous people call Peru their home, but only 28 percent hold a formal title to the land they inhabit. This, coupled with a government which has yet to respond to indigenous claims to 50 million acres of land, makes indigenous people in Peru—regardless of their preference to preserve or exploit the resources they consider to be theirs—particularly vulnerable to the wills of the more powerful.

Protecting the environment for its own sake has never been an easy sell, especially when the advocating is done by those who lack the necessary social and physical capital to influence governmental decision makers. It’s an even harder sell when big agribusiness, mining and other extractive firms have set their sights on Latin American countries whose leaders continue to clamor for economic growth and increased foreign investment.

Like a number of Latin American countries in the 1990s, Peru made constitutional changes to open itself up to the global market, entering free trade agreements with numerous countries around the world, passing laws that gave foreign investors the same rights as Peruvian investors, and more recently making agribusiness in the Andean region tax free to encourage development at high altitudes. It shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that since 2000 the equivalent of 50 soccer pitches of the Amazon rainforest have been lost every minute, with the global illegal logging industry (in Peru, it’s “illegal” to log in protected natural areas) raking in a cool $30 billion USD every year.

These are the same forests on which 60 million indigenous people wholly depend to survive; these are the same people whose sovereignty Chico Mendes—and now, Edwin Chota—died trying to defend.

Unfortunately, defenses like those of Mendes and Chota seldom bear any significant fruit, as sovereignty is something we tend to recognize only when we consider another person, or group of people, to be our equal.

Appearing to exist outside of a temporal understanding of what society “looks like”, indigenous people have long captured the interest of the “civilized”, from Hernán Cortés’ conquest of La Malinche, to Disney’s pixelated princess Pocahontas, to Paul Gauguin’s sensual depiction of Tahitian women. Their perceived foreignness renders them objects of intense fascination: how is it possible that, in a world filled to the brim with consumer goods and services, they have managed to exist outside of it and forge their own alternative? Are they aware of something we aren’t, something bigger that transcends our consumption-obsessed frame of vision; or have they just not yet seen the modern, market light? Shall we reify them, or teach them?

The answer is, of course, “neither”. And yet, dichotomies like these persist and continue to shape present-day relationships with and treatment of these groups. For centuries, indigenous people around the world have altered and exploited their environments, sometimes sustainably, sometimes not. Nevertheless, people in positions of power have historically failed to recognize this, mistaking indigeneity for either primitive purity or—like a child—a lack of “development”.

For every extractive firm that tramples on indigenous land claims and autonomy, there’s another “pro-indigenous” NGO whose protectionism can be better defined as paternalism, with both the “exploiters” and “protectors” robbing indigenous people of their humanity—that is, their ability to make decisions for themselves and by themselves, good or bad—all the while.

Arguably more obsessed with a pristine, Walt Whitman-esque wilderness fantasy than they are the reality of a manmade nature, conservation groups like the World Wildlife Fund and Conservation International have been known to push the “problem” of the indigenous out of protected areas. Their thinking is presumably that, as children, indigenous people do not know how to manage or protect the environment and thus must be removed from it should the environment itself stay intact.

Indigenous people are not blind to those sentiments, either. At a meeting of the International Forum on Indigenous Mapping in 2004, the 200 delegates present signed a declaration which said that the “activities of conservation organizations now represent the single biggest threat to the integrity of indigenous lands”.

Meanwhile, land clearance and violence against pro-environment and indigenous groups—coupled with a stony silence on behalf of the state—continue in the name of bigger, more profitable goals that are only as “green” as the dollar bills on which they are printed. That’s why, the day after the Rio Earth Summit ended in 1992, environmental activists who had been campaigning to protect Rio’s fishing communities from the expansion of oil operations were abducted, only to be found dead four days later. That’s why in 2011, months after kicking out corrupt police, blocking roads that lead to illegally logged oak timber and establishing an autonomous, indigenous-governed community, Cherán, Michaocán, native Domingo Chávez Juárez’s body was found burned and decomposing on the foothills of a nearby volcano in Mexico. That’s why, mere weeks before an international climate summit is to be held in Lima, Peru, Edwin Chota is dead.

So much, and so little, has changed since Chico Mendes’ death in 1988. Global concern has shifted from the greenhouse effect to climate change writ large. Traces of Mendes-led “empates”—or human barricades to prevent bulldozers from tearing into trees—have since gone global, and are not dissimilar to events seen during September’s massive Climate March. Indigenous knowledge is becoming both valued and valorized by international organizations and investors. And, as the science behind understanding a climate-changed future becomes more sophisticated, we have begun looking more frequently to experts of the indigenous kind for lessons they have learned in the past.

Following the murder of Chico Mendes, his adviser and agronomist Gomercindo Rodriquez said: “Those who killed Chico got it wrong. They thought by killing him, the tappers’ movement would be demobilized, but they made him immortal”. The same can be said for Edwin Chota, for Chávez Juárez, and the hundreds of others whose belief in a socially just use of the environment has resulted in their death.

The Lima Climate Change Conference begins on December 1st. Let’s see what lives on there.

The Invisible Sounds: the Struggle of Afro-Colombian Music

Every September, the Colombian region of Chocó, located along the country’s Pacific coast, turns into an overwhelming party. The streets in the capital city of Quibdó are full of parades. Music takes over to celebrate the festivities of San Pacho. This festival, that reflects the history of cultural and religious colonization in Chocó, became a symbol of the region’s musical traditions.

The Invisible Sounds [Los Sonidos invisibles] is a documentary by anthropologists Ana María Arango and Gregor Vanerian that focuses in the San Pacho festival as an epicenter of music culture in Colombia. Both filmmakers present a variety of protagonists that allow us to understand the complex cultural history of Chocó and how difficult it has been for its people to fight for recognition.

In the documentary, Octavio Panesso, a musician, composer and activist who works to preserve the culture of Chocó, talks about a congregation of Catholic priests known as the Clarentian Missionaries. They created cultural spaces in this region that has been completely abandoned by the Colombian State. These were spaces where traditional music was signaled as “primitive” or “the devil’s work”.

This colonial legacy got re-appropriated and this music is music of resistance as well. The filmmakers portrayed women singing about redemption, the end of slavery, or their fear of dying in the mines. It is also music to remember the past and vindicate dancing traditions in the present.

Chocó is usually only talked about as a region with high levels of unemployment, violence and poverty. It is also where a large population of Afro-Colombian lives. Many arrived there escaping slavery during the Spanish colonial period, and many others arrived after abolition. This documentary shows, in a subtle way, their long history of resistance and their new struggles fighting the logics of the market and hegemonic cultural models today.

November 21, 2014

How not to write about Africa: Use “African Spring”

On October 30, as thousands of determined Burkinabe put an end to the 27 year rule of their Western-backed autocratic leader, Blaise Compaoré, journalist Hewete Selassie asked a question (in a tweet) that pops up whenever mass protests break out somewhere in Africa: “So is #BurkinaFaso the beginning of the African #Arabspring?”

It is one thing to wonder about the possibility of the Burkinabe revolution setting off domino-effect ripples in the region similar to the 2011 uprisings. After all, few periods in modern history have seen so much turbulence affecting so many millions of people as the early months of 2011. The “Arab Spring” has become our reference point for revolutions in this digital age. Yet, a far longer and rich history of African civil struggle is often missing in contextualizing today’s protest movements on the continent.

Tunisian fruit vendor Mohamed Bouazizi, who set himself on fire in December 2010, sparking the widespread Arab revolt, follows a long line of men and women whose self-sacrifices inspired others in action, forcing social change. For example, Mary Muthoni Nyanjiru was killed in 1922 after stripping naked and fearlessly walking into police bayonettes during a peaceful protest in Nairobi against the arrest of an activist who had campaigned against sexual exploitation of women and girls in colonial plantations in Kenya. Saal Bouzid’s determination to fly the flag of independent Algeria during a peaceful protest against French colonial rule made him one of the first victims of the 08 May 1945 Setif massacre. There’s Hector Pieterson, one of the first victims of the Soweto student uprising of 1976. The list goes on. Lest we forget, there were also extraordinarily effective acts of mass civil disobedience, such as the market women’s protests against British colonial tax in Nigeria in 1929 and 1946, the defiance campaign against Apartheid’s unfair laws in 1952 in South Africa and the 1947 railway strikes in Senegal.

Historian W.J. Berridge wrote in a column last month that, “many Sudanese intellectuals watched on with wry amusement as, in 2011, the global media announced that the popular uprisings in Egypt, Tunisia and Libya were the first civilian movements to overthrow military autocracies in the Arab world.” In fact, the temerity of the Sudanese deserves special recognition for their success in twice overthrowing military dictatorships within two decades—first in October 1964 and then in April 1985. It is worth imagining the amplified effect of the internet and social media on such popular protests from the past: would Sudan’s revolts have stirred a haboob (the name of a fierce sandstorm common in central Sudan) in neighboring countries in the region? We’ll never know, but Berridge’s book “Civil Uprisings in Modern Sudan: The ‘Khartoum Springs’ of 1964 and 1985” is an attempt to reconsider this overlooked past with the present.

Between the two Sudanese uprisings was the 1974 popular uprising that ended the reign of Ethiopia’s last Emperor, Haile Selassie. A hike in the price of fuel resulting from the Arab-Israeli conflict in January 1974 compounded simmering social problems and injustices of a decaying feudal system in the throes of modernization. A perfect political storm of protests by taxi drivers, teachers, students, trade unions, and soldiers ended in the military coup that deposed the imperial regime in September 1974. This pattern of political protest growing out of socio-economic grievances is the common thread of almost all the other popular revolutions in the last four decades in Africa. For example, during Sudan’s 1985 revolution, many of the protesters chanted slogans against the International Monetary Fund over its imposition of the removal of a bread subsidy. Austerity measures imposed by the IMF in response to the African debt crisis that began in the 1970s and deepened in the 1980s sparked much popular discontentment.

In Sub-Saharan Africa in particular, the “food riots” effectively pressured rulers from Kenya to Senegal and Benin to Zambia to end one-party regimes in favor of multiparty democracy in the early 1990s. The African rulers that refused to accept the new democratic arrangement, such as Mali’s military dictator Moussa Traoré, were rare and doomed – a popular revolution swept Traoré from power in 1991. In his book “African Struggles Today,” Peter Dwyer writes that “Africa exploded in a convulsion of pro-democracy revolts that saw eighty-six major protest movements across thirty countries in 1991 alone.” From 1990 to 1994, some “35 regimes were swept away” by protest movements and strikes. Many held elections for the first time in a generation,” Dwyer added. The impact, domino effect and geographical spread of these democratic revolutions arguably dwarf the “Arab Spring.”

More recently, between 2007 and 2010, renewed “food riots” for bread and freedom swept again across Africa (and the world), from Burkina Faso to Cameroon, and from Senegal to Mozambique. This time, they were largely brutally suppressed, but the unmet popular demands behind them contributed to popular discontent that led to the military overthrow of leaders in Madagascar in 2009 and Niger in 2010.

Every time mass protests break out somewhere in Sub-Saharan Africa, the international media is quick to use the term “African Spring,” however this catchphrase not only carries a near-sighted historical perspective of African protest movements but is also unfit for the context. According to Foreign Policy Associate Editor Joshua Keating, “the term ‘Arab Spring’ was originally used, primarily by U.S. conservative commentators, to refer to a short-lived flowering of Middle Eastern democracy movements in 2005.” It resurfaced in January 2011 in the title of an FP article by Marc Lynch before wide adoption by the Western media (and rejection by the Arab press). Going back further into history, the figurative spring as a movement of political renewal flows from the “Spring of Nations,” a wave of anti-feudal movements that began to shake Europe in February 1848.

When you consider that spring is rather an alien notion to millions of Africans living between the tropics, using a spring metaphor to describe their efforts at political renewal is inadequate. The notion of a renewal event or period, however, is universal and coded in all cultures and languages, and is often tied in the African context to the onset of seasonal rains or winds. This is why many writers in the francophone African press have, for example, attributed the sweeping change in Burkina Faso to harmattan, a hot, dry and dusty wind blowing over West Africa. Perhaps incorporating the local perspectives and culture can produce better informed headlines and analysis and prevent coloring complex events with facile catchphrases.

Music Revue, No.4: Constant Messiah

Earlier this year I attended a museum opening in which the curator admitted to being completely unaware of the existence of Burkina Faso until shortly after the artist being presented, the late Christoph Schlingensief, had relocated there. It was an innocuous enough confession — coming well before the leadership upheavals of the past two weeks — but one that made me aware of my own shortcomings re: the landlocked West African nation. I’d certainly been aware of Burkinabes for quite some time, but if asked I might not have been able to picture exactly where they were on a map without being reminded that they’d lived in a French colony called Upper Volta until 1984 (read: years after my last high school geography class). I suspect the curator, a cosmopolitan German about my age, probably had a similar excuse.

Singer Kaneng Lolang is a cosmopolitan currently living in Ouagadougou. She’s spent time in Siberia and Brooklyn, but her roots are in Nigeria, Lagos, specifically. In interviews she’s suggested that Lagos may have lost its ability to musically hypnotize her, and it’s clear that the video for “Constant Messiah” —shot earlier this year in and around Bobo Dioulassa in southwest Burkina Faso —is an attempt to retain some of the trance-like mysteries her music embraces. As a result, the minimalist bass loop seems both tribal and inviting; the violin pierces, creaks and crackles, an eerie echo to the video’s distorted images. What does it all mean? Don’t expect Lolang’s lyrics to put a fine point on it. She’s clearly opting for blurred lines.

Digital Archive No. 4 – Africa Cartoons

One of the first thing I do on Friday morning is log on to the Mail & Guardian website to see the latest from Zapiro. Jonathan Shapiro, better known as Zapiro, is a Capetonian political and social cartoonist whose work not chronicles current events in South Africa, but also provides visual critiques of political leaders, public events, and social ills. Take, for example, Zapiro’s latest contribution: a satirical representation of the return of eighty South Africans who died in Lagos during a church collapse over two months ago.

Not only does this cartoon represent a snapshot of the moment at which the bodies were finally returned to South Africa after a long two month delay, but this cartoon also allowed Zapiro to express his opinions about TB Joshua (the televangelist who owned the church which collapsed) and his laughable credibility. His work makes it clear that cartoons are not only meant to be humorous (which they absolutely are) but that cartoons hold the potential to serve as powerful historical sources that are as worthy of digitization as any “traditional” historical sources.

That’s where this week’s featured project, Africa Cartoons, comes in. Africa Cartoons is, in the words of Tejumola Olaniyan, meant to be “an educational encyclopedia of African political cartooning and cartoonists.” The site features the work of over 180 cartoonists from throughout the African continent. Though not every country is represented, it is an amazing collection that pulls together a wide range of artists, making their work more public and easily accessible. The site functions through a main interactive map, through which the user selects a country and then is taken to a page containing samples of some cartoonists from that nation. The individual pages of the cartoonists, which can also be directly accessed through the Cartoonists page, also contains some brief biographical data about the artist and relevant links. The site also includes a useful Resources page which links to more general cartooning sites, a number of pages directly related to African cartoons, and links to newspapers from throughout the continent.

Though there is more work to be done, which Dr. Olaniyan admits on the About page, this is a phenomenal collection of comics that not only brings attention to these talented artists, but also provides a way for researchers and other interested parties to explore new pathways for research through comic art. I know that just from exploring this site, I’ve added some new artists to my weekly comic roundup that previously only included Zapiro.

November 20, 2014

The Right to Grow Old: Photos of the Central American Migrant Crisis

Central American migration, and especially the migration of undocumented children from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras to the United States, blew up in the American media during the summer. It was a time when many U.S. citizens felt that their government was deporting too many of these children back to the mostly violent and poverty-stricken conditions they were trying to escape (and many others felt that not enough were being deported).

Tonight, as President Barack Obama announced a series of measurements that are intended to facilitate the path to legalization for millions of immigrants, but that will also strengthen borders policing, U.S. news outlets might pick up on this human crisis again. Maybe most of them will not discuss the reasons why so many people from Central America decide to leave their homes and embark on a dangerous journey to an unknown land. Maybe only a few will mention the role of the United States in creating violence in Central America. We’ll see.

But for now, thanks to Honduran photographer Tomás Ayuso, we can see what it is like to actually live through this voyage. Ayuso is an independent journalist and field investigator for Noria, who focuses on immigration, the drug war and US-Latin American relations. For his photo essay The Right to Grow Old: The Honduran Migrant Crisis, Ayuso himself traveled from Honduras to the United States, documenting violence in the Central American nation, the world of “death trains” and shelters for migrants throughout Mexico, and the problems of crossing the border, as well as exploring the reasons and problems behind deciding to enter the United States.

Below is a selection of Ayuso’s pictures (with his original captions).

The southernmost points of the train network start in Tenocique, Tabasco and Arriaga, Chiapas. The freight trains used by migrants, popularly known as La Bestia (the beast) and El Tren de la Muerte (the death train), are found throughout Mexico.

“On the highways, I’ve been robbed. They’ve taken my phone, my money, my shoes and my shirts too. But thank God. Like I tell God, thank you father. As long as I have life… While there is life and hope, that’s what matters.” Rolando jumps between cars, demonstrating his ability to outrun anyone who chases him.

A man pitches a hammock on the Bestia in Arriaga to make sure he won’t miss his ride. Since the crackdown began, trains have been used for migration much less. The migrant route has been pushed into the dangerous mountains and forests outside major cities along the migrant route.

In addition to the different law enforcement agencies patrolling the US-MEX border, local and national border defense militias are popping up along the river. One such militia, Free Nebraska, joined the fray after the migratory crisis began receiving daily coverage by the national media.

Isaac looks towards Mexico at one of the many blind crossings into the US through the Rio Grande. “This section right here is pretty deep and pretty wide. They get in boats, inflatable rafts. Really anything. They’ll tie anything together they can get together that floats.”

Migrants fill out forms with basic information prior to release. The numbers from the CAMR have around 32,000 deportations by air in 2014 so far. Numbers of deportees by land from Mexico and Guatemala are unavailable due to poor record keeping, however the CAMR estimates an additional 30,000 have been deported via bus.

The number on Juan’s shirt was his ID while detained in Port Isabel, TX. “The guards were racist and harassed us. One taunted me that as long as my countrymen crossed the border they’d have jobs. Another guard would always tell us our countries were shit and that we were all criminals. In those bunkers they treated us like dogs.”

A mural painted by a passing guest at the only migrant shelter in Honduras. Located in Ocotepeque, it straddles the triple border with Guatemala and El Salvador. Unlike other shelters, this one caters mostly to people who abandon the migrant route and turn back to their communities in Honduras.

Sister Lidia, of the Scalibrinian order, is one of the lead coordinators for the country’s returned migrant program. Sister Lidia, a Brazilian, is one of the most tireless human rights defenders in Honduras, fighting for the right to migrate and, what she calls the right to not have to migrate.

A group of migrants who had limbs amputated because of injuries by the Bestia, listen to testimonies during the first meeting of the congress of injured migrants. Participants from all corners of Honduras joined the weekend retreat high in the mountains surrounding Tegucigalpa. The congress held workshops and provided clinics to help migrants cope with their injuries, learn to value their place in society, and build a community among themselves.

For the whole series, go to Tomás’s website.

#SAHipHop2014: @Okmalumkoolkat has a new album

In 2010, I acquired an illegal copy of The Clonious’ Between the dots LP after hearing him play a set on Mary-Anne Hobbs’ Generation Bass programme which used to be hosted on BBC Radio 1. I instantly fell in love with his production style, a gently-grinding jazz crusade characterised by lush-sounding synth pads and a general preference for warm and all-encompassing instrumentation. During that period, I also discovered that the UK’s LV had collaborated with Okmalumkoolkat, an emcee originally from Durban whom I’d discovered a year earlier via his own blog.

Both artists have become better masters of their techniques ever since.

While most of Between the dots was space jazz-leaning, The Clonious’ production technique has expanded to include elements of Chicago footwork which, combined with Okmalumkoolkat’s Umlazi-dipped universal swank, suggest multiple pathways for which South African electronic music in general can head. Cid Rim, The Clonious’ partner in Affine records and forthright producer on his own right, shares behind-the-board duties.

Okmalumkoolkat’s rap lexicon has grown in leaps and bounds; he’s become better at injecting ancient mythology, futurism, and current pop trends into his lyrics. He shouts out Credo Mutwa and envisions phone calls by AllBlackKats to gods who came as humanoids.

If you pay enough attention, Okmalumkoolkat steadily reveals layers of himself to you. He’s not one thing, that’s for sure: “I’m eating sushi/ owusu/ no-phutu/ my hat is from Lesotho/ my bloodline is Zulu/ starsign is leopard, my spirit is kudu” he raps in “Ijusi”.

Another way to view the music is as live portraiture. Okmalukoolkat has a natural inclination to throw ideas which, at first glance, seem disconnected from each other. However, with every stroke, key details are revealed, and a fully-fledged picture is eventually formed.

Holy Oxygen’s strongest point is that the lyrics and the music merge beautifully; that nothing sounds coerced. It’s festival music, club music, sure; but it’s also get-busy-while-cooking-in-the-kitchen music; it’s what you play when navigating the mania of the innercity; and it’s what your mind can consume to get transported into distant worlds and multiple galaxies.

The way in which we consume music is changing, and it’s time to perhaps think about not only how it’s made, but also how it gets written about. My relationship with both artists begun on-line; it wasn’t facilitated by the radio; I didn’t go to a show. I experienced a telepathic connection to the sound via mp3 – that’s a new phenomenon, a new layer of relating to sound. In Holy Oxygen, Okmalumkoolkat introduces a batch of similarly new layers. Some are works in progress; some are mind-boggling. Their combination translates into a definitive body of work which is reflective of the times, and of the city in which he lives – Johannesburg.

Okmalumkoolkat is also a universal being. You can’t quite pin him down. At one point, he’s strolling up and down the hilly expanse of Umlazi hunting for the next gqom party; next, he’s in Nairobi talking digital art; or he could be either recording or on tour somewhere in Europe, and spitting venom to festival audiences which, in no time, shall grow and expand.

Towards the end of last year, Okmalumkoolkat tweeted that 2014 was his. After hearing this, one of his many victories this year, there is no second-guessing that statement.

*This article is part of Africasacountry’s series on South African Hip-Hop in 2014. You can follow the rest of the series here.

November 19, 2014

Music Video Premiere: DJ Mellow and Steloo’s “Séké”

Africa is a Country is pleased to premiere the music video for “Séké” by DJ Mellow and Steloo:

The song, whose title means “crazy” in Ga, is part of Brussels-based DJ Mellow’s A Slice of Bass EP. The collaboration between him and Accra’s Steloo came about via Max Le Daron, who I mentioned Monday was one of the participants in Akwaaba Music’s Roots of Azonto project. As Max describes, the track came about:

When I was in Ghana for the Roots of Azonto I met Steloo, who was willing to MC on my tunes. We did a few try outs then I put one draft of DJ Mellow’s tune in the studio and Steloo insisted to record on it. It clicked and Mellow finished the tune in Brussels, using samples from the Roots Of Azonto Soundbank… Et voilà!

And thus we have another great example of Azonto’s persistent impact on international dance music. However, the catchy beat, and striking production don’t really remind me of Azonto per se. To me, the beat harkens back to around 2008, the hey day of U.K. Funky, a sound that I believe was integral to the formation of Azonto, and the current wave of Afropop all over West Africa. I hear it blending perfectly with the early sounds of producers like Roska, Crazy Cousins, or Donaeo, themselves influenced by the West African and Caribbean rhythms of their parents’ homelands. Take into consideration contemporary U.K. Funky oriented and Ghana inspired producers such as The Busy Twist, and it seems like feedback loop just keeps getting louder.

The video was shot in Accra by Ghanaian photography artist Amfo Connolly, then edited in Brussels by Pierrot Delor from La Lune Urbaine collective.

Using blackface to make a point

The filmmaker Sunny Bergman’s documentary ‘Our Colonial Hangover’ will premiere in Amsterdam at the annual international documentary IDFA festival on November 27th. The film reflects Bergman’s personal search into national blackface character Zwarte Piet (Black Pete), Dutch colonial history and white privilege. Bergman herself has been active in campaigning against blackface.

A teaser from the film posted by a Dutch broadcaster (watch here) went live last week and by this afternoon had close to half a million views on Youtube. It has contributed to the buzz for the film’s premiere. The clip shows us Bergman, who is white, dressed up in blackface in a public park in London to see what people’s responses are. Generally the trailer has been well received and it is has been widely shared on social media (not least because Russell Brand makes an appearance). Even Africa is a Country tweeted it.

Some activists have, however, questioned Bergman’s strategy.

Dutch activist and writer Simone Zeefuik, for example, cautions why we should be aware of the framing deployed when it comes to films on race and the larger Dutch media context:

Dutch media is where framing goes to die. This week, it was announced that the movie Dear White People will hit Dutch cinemas. Dutch news site nu.nl bored us with the headline “Controversial racism satire in Dutch cinemas” but makes no mention of Bergman’s documentary. And what’s more satirical than calling colonialism a ‘hangover’ and implying that, from what I heard about being drunk, we are now entering an era of recovery. The digital version of Dutch newspaper NRC does mention Our Colonial Hangover and calls it “a documentary.” It mentions how Russell Brand reacts when he sees Bergman in blackface and, for reasons only clear to an editorial team that couldn’t be less productive if they were on strike, morphs his “We are scared of your tradition”-quote into “Your tradition surprises us.” In the newspapers and on their sites Bergman’s work, if mentioned at all, isn’t sullied by critical notes or sounds of disapproval masked as ‘casual adjectives’. She, contrary to non-white critics, gets the benefit of the doubt. And with ‘doubt’ I absolutely mean Whiteness.

Dressing up in blackface to tackle racism is a purposely chosen ‘tactic’. But why and on whose behalf is Bergman (supposedly) tackling racism by dressing up in blackface? The assumption here is that dressing up in blackface for a ‘cause’ or as a ‘critique’ makes it fine. Perpetuating the very racist structures that underlie Black Pete are not as important as ‘proving’ that Black Pete is racist. In the name of ‘critique’ people are unwillingly exposed to blackface just to ‘prove’ how racist blackface is. Here’s activist Ramona Sno:

This woman says she is fighting anti-black racism in blackface? I felt terrible for the black people that had to see this in London, they were confronted with racism because of her.

Such an approach is not only very unsettling it also reflects how messy (supposed) anti-racism politics are in the Netherlands. Anti-racist politics become messier the minute when it comes to the Black Pete debate and it becomes easy to forget that people speaking out today were not the first to do so. People have been protesting for a very long time against Black Pete and racism in the Netherlands (more on this topic soon), however, their histories have been carefully erased. We should therefore continue to question who is allowed to speak on these subjects and who is being heard. Even more so, we should question on whose behalf people speak and what it implicates within anti-racist work.

As many black consciousness thinkers have argued, the idea that people are helping ‘us’, or doing ‘us’ a favor and that ‘we’ should be grateful is a very problematic one. Steve Biko has described the helping white liberal (in the South African apartheid context) as someone who sees the oppression of blacks ‘as a problem that has to be solved.’ Similarly, Black Pete and racism is tackled by the progressive and critical left as something that needs to be ‘solved’ in the Netherlands, without critically engaging with eradicating whiteness and realizing it is actually bigger than Black Pete. What then does the popularity of the trailer tell us about anti-racist politics in the Netherlands? Sno explains:

The fact that the clip was actually widely well-received shows us how also black and non-black people of color are invested in this white anti-racism narrative that is not actually radical or abolishing the system of White Supremacy.

It is important to note that our critique is aimed at what the trailer of the film does. It repeats a ’tactic’ that is an old and widespread one within anti-racist work and sustains an economy of gratefulness – an idea that is very at the root of Dutch thinking about ‘self’ and ‘other’. Within the context of anti-racist work, gratefulness very much implies a constant debt towards the one who is ‘helping’ and is often confused with solidarity. However, we should really not be ‘happy’ or ‘grateful’, when in the name of anti-racism, or in the name of critique, people start using blackface to make a point.

* Image Credit: IDFA.

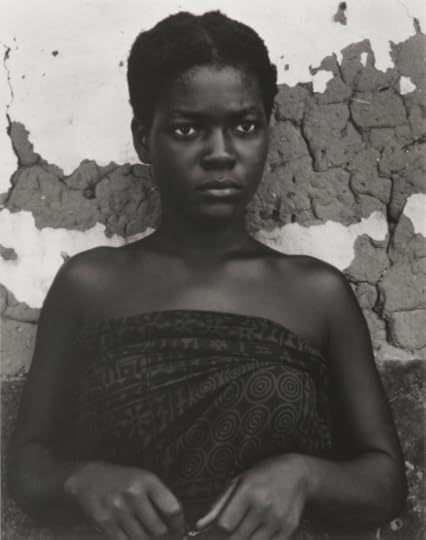

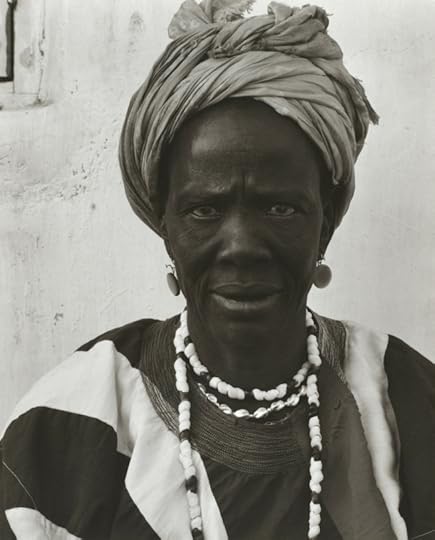

The photographer Paul Strand’s 1960’s Portrait of Ghana

“The Artist’s world is limitless,” remarked photographer Paul Strand once. “It can be found anywhere, far from where he lives or a few feet away. It is always on his doorstep.”

A photographic icon of the 20th century, Strand was a major advocate for considering photography as a serious art form. His career of more than 60 years is currently being honored at the Philadelphia Museum of Modern Art with the show Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography, which runs through January 4, 2015. Though Strand got his start taking street portraits in New York City, his later years were dedicated to capturing the character of diverse landscapes including Mexico, France, Italy, Scotland, Morocco, Egypt, Romania and Ghana.

With the support of President Kwame Nkrumah, Strand’s last major geographic portrait was of Ghana, where he took photographs over the course of roughly three months between 1963 and 1964. This body of work resulted in the publication of the book Ghana: An African Portrait, which featured a companion text by the great Africanist scholar Basil Davidson. This journey was also captured briefly in the documentary about Strand’s life, Under the Dark Cloth.

The book depicts Ghana as a new African nation of peoples poised for industrial ascension. In his illustration of this theme, Strand produced portraits of students, vibrant marketplaces and technical machinery.

Though he believed in the honesty and objectivity of the camera as an artistic tool, Strand was also well aware of the photographer’s control over their images. Thus, images of technological advancement in the book, are sometimes paired with those depicting traditional cultures and natural environments. While all the images represent the visual “truth” of what Strand’s camera documented, the manner of their juxtaposition implies Strand’s idea of “modernity” comes from a diet of increasing industrial growth and Westernization.

However, it must be said that Strand, throughout his career, took great pains to ensure his portraits of people captured their humanity and their dignity. Unlike some of his Western contemporaries taking patronizing anthropological photographs throughout the continent, Strand’s images identify his subjects by name and often mention their communities as well. The portrait of Anna Attinga Frafra for example, depicts a quiet moment, in which Ms. Frafra rests three books comfortably on her head. An image of such grace could only be taken with the trust of the model.

In the few months Strand spent in Ghana he could not possibly have captured his surroundings with the ease and nuance of Ghanaian photographic great, James Barnor or the newer generation of incredibly talented Ghanaian imagemakers such as TJ Letsela, Nana Kofi Acquah, Ofoe Amegavie and Nyani Quarmyne, yet Strand’s photographs endure nonetheless as windows through the Western lens into the optimism and dignity of post-colonial Ghana.

In Strand’s words again, this time from a 1973 interview:

“The People I photograph are very honorable members of this family of man and my concept of a portrait is the image of somebody looking at is as someone they come to know as fellow human beings with all the attributes and potentialities one can expect from all over the world.”

Afe Negble, Asenema, 1964

Asenah Wara, Leader of the Women’s Party, Wa

Mary Hammond, Winneba, Ghana

Market, Accra, Ghana

“Never Despair” Accra Bus Terminal, Ghana

Oil Refinery, Tema, Ghana

Jungle, Ashanti Region, Ghana

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers