Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 263

December 13, 2017

What does the Catalan independence movement mean for African separatists?

“Pity the nation divided into fragments, each fragment deeming itself a nation.”

—Kahlil Gibran

“Africa is one continent, one people, and one nation.”

—Kwame Nkrumah

“I was Nigerian and Igbo. I think the idea of an ethnic identity being somehow mutually exclusive with a nationalist identity really doesn’t apply, at least not in my life.”

—Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

“Catalonia is not Spain.”

—slogan of Catalonian separatists

Sovereignty is a kind of riddle. Once a unitary nation-state has been established, it’s historically been quite difficult for a group within that nation to claim independence. The inherent contradictions between a state’s right to territorial sovereignty on one hand, and a people’s right to self-determination on the other, has troubled international law since the early twentieth century. Postcolonial Africa is no different. It’s perhaps not surprising that most movements for self-determination have been achieved either through violence or due to the intervention or acquiescence of an external sovereign power. On the first, think Eritrea, for example. On the second, South Sudan; though it also was involved in a violent struggle for independence against Khartoum. Whether economic and political sovereignty is easily achievable, especially within the context of decolonization, has also been a hotly debated topic amongst nationalists, as the anthropologist Yarimar Bonilla notes. Yet despite numerous efforts by political thinkers — ranging from Hannah Arendt to Senegal’s founding President, Léopold Senghor — to champion federalist, non-sovereign, and non-nationalist alternatives, the nation-state has remained the dominant political model for much of the twentieth century into today.

One can see such tensions at play in the Catalan independence movement. And while much has been made of the implications of Catalonia for European movements (like the Basque and Scottish independence campaigns), less readily acknowledged is the impact this controversy is having on independence efforts on the African continent. In fact, proponents of separatist movements in Nigeria and Cameroon are watching the situation in Europe quite closely, hoping that it might set a more wide-reaching legal and political precedent.

Viewing European and African separatist movements through a common lens, and as part of a shared predicament, invites productive comparisons. And it also holds implications for those of us committed to a leftist, internationalist politics. It forces us to consider why certain secessionist movements receive greater global attention and whether all calls for self-determination should be taken equally seriously.

Several Nigerian writers have already drawn analogies between Catalonia and Biafra. As the writer Onyedimmakachukwu Obiukwu notes, October 1st is now a date fraught with significance for both nations. On that day in 1960, Nigeria achieved independence from British rule. For many Nigerian nationalists, this marks the beginning of the country’s “non-negotiable separability.” Privileging this moment also helps to delegitimize Biafran separatists (as Igbo nationalists became known), which was brutally suppressed by the Nigerian government in a civil war that cost a million lives in the late 1960s. Coincidentally, October 1st of this year was also the date of a referendum unilaterally set by the Catalan government to ascertain popular support for secession (but perhaps more importantly, to send a message to Spain’s ruling party, Partido Popular). Voters were met by Spanish police in riot gear, who used rubber bullets and tear gas in an effort to prevent the poll from taking place.

By noting this concurrence in dates, Obiukwu is able to point to more structural similarities. Separatist conflicts are often perceived as uniquely African problems (simplistically attributed to the continent’s “arbitrary” borders or its “tribal” divisions). Yet as the case of Catalonia shows, Africa is no anomaly. Nor is the continent pathologically inclined toward conflict. Europe, moreover, should not be held up as the normative model of nationalist cohesion. All nation-states subsume certain forms of difference onto themselves, and all are predicated on the suppression of competing nationalist visions. The transition and experiments with political federalism in both Nigeria and Spain over the last few decades have failed to fully resolve such tensions.

At the same time, both European and African separatist movements refract the possibility for conflicts to be prevented through the emergence of more layered, trans-territorial forms of sovereignty. The European Union has eased tensions along many (formerly “hard”) political frontiers. The freedom of movement between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland — a status quo enshrined by the Good Friday Agreement — is now being threatened by Brexit. The potential for regional integration to enable overlapping nationalisms to coexist (and greater local autonomy to be achieved) was anticipated by a number of Pan-African thinkers. In the 1950s and 60s, African leaders — ranging from Kwame Nkrumah to Julius Nyerere — toyed with the idea of economic and political federations capable of tying African countries together and lessening the significance of colonial borders. Pan-Africanism was championed for many reasons —one of which was its potential to mitigate the threat of separatism and irredentism.

Nkrumah’s vision of a United States of Africa and Nyerere’s hope for an East African Federation never came to pass. Nor is it clear that such federalist structures are always guaranteed to resolve or even mollify separatist aspirations. (As the EU’s reaction to the recent crisis in Spain shows, such political structures can sometimes serve to further reinforce/centralize power at the state level). Nevertheless, ongoing efforts to promote continental and regional integration in Africa may very well usher in solutions to the problem of secession.

For all the parallels that one can draw between the Biafran and Catalonian cases, there are also notable differences. While both the Spanish and Nigerian governments (as Obiukwu argues) have been “heavy-handed” in their approach to the respective separatist efforts on their soil, the degree of violence meted out by Nigerian officials in recent years has far outstripped that of Spain. Moreover, while the international frontiers of European states are perhaps no more or less “arbitrary” than those of Africa, African boundaries are arguably less politically legitimate. Many African political thinkers are in favor of either dissolving or remaking the continent’s inherited colonial boundaries — though this need not necessarily be achieved through separatism.

Perhaps most importantly, separatist movements in Europe and Africa look quite different when considered within a broader analysis of the global political economy. According to Nigerian journalist, Segun Akande, many easterners in Nigeria (where the Biafran state was to be established) are “reluctant to lend their voices to the struggle” both because of the memory of “the millions who died of starvation” during the Biafran civil war and “the current economic situation in the East.” Catalonia is the wealthiest region in Spain and occupies a very different position within the world economy. It’s questionable whether a Biafran state (even one that included the oil-rich Niger Delta) could ever enjoy the same experience of sovereignty. And as Pan-African activists have long cautioned, fragmentation is likely to lead to greater economic and political vulnerability on the world stage.

Movements for secession may refract a shared global predicament, but they can have profoundly different consequences in different parts of the world. Where, then, does this leave us?

One thing that recent separatist conflicts make clear: it makes little sense to either categorically support or categorically reject calls for secession. In addition, framing conflicts as a stark choice between “separatism” and “unity” can obscure the voices of those who seek alternative paths (or those who mobilize around secession claims for rhetorical and tactical reasons). In discussing her novel Half of a Yellow Sun, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie remarked that she grew up feeling both Igbo and Nigerian. She attributes the Biafran civil war to political failures, rather than irreconcilable differences or in-born ethnic divisions. For journalist Kayode Robert Idowu, the conflict over Catalan should serve as a cautionary tale for Nigerians. According to Idowu, Nigerian federalism needs to be restructured, but not wholly abandoned.

Just as the “people” are not a homogenous body, the “left” is far from a unified entity — as evinced by recent debates amongst neo-Marxists in Spain. Additionally, separatism can be (sometimes simultaneously) driven by economically and politically progressive forces and conservative ones. Catalan undoubtedly has a right to hold a referendum without facing the threat of state violence. (Until then, it is also difficult to assess the degree of popular support for independence.) But referendums do not simply measure popular opinion; they generate types of political subjectivity. And as the case of Brexit attests, referendums do not always produce progressive results. Working solely through the legal mechanisms of the state can also foreclose more critical forms of political analysis. As Alberto Garzón suggests, it is worth asking whether “the national question” in Europe today is being “used as a populist channel for the frustration generated by the crisis of capitalism.”

In the end, neither pro-unification nor pro-separatist movements are able to solve the riddle: the dilemma of sovereignty. These include fundamental ambiguities at the heart of the nation-state, such as the kind of structural and demographic anxieties that fuel both minoritarian and majoritarian tendencies. For this reason, both pro-unity and secessionist supporters can at times be motivated by chauvinistic and xenophobic tendencies.

Which is why it’s so essential for political activists to understand the broader context in which separatist demands emerge, to consider the stakes and the alternatives, to listen to heterodox and minority voices, and perhaps most importantly, to examine the nationalisms that they themselves hold dear. However flawed and riddled with ambiguities, self-determination remains a powerful and important language for peoples the world over. But it’s also a language that needs to be carefully interrogated.

Catalonia is a Country

“Pity the nation divided into fragments, each fragment deeming itself a nation.”

—Kahlil Gibran

“Africa is one continent, one people, and one nation.”

—Kwame Nkrumah

“I was Nigerian and Igbo. I think the idea of an ethnic identity being somehow mutually exclusive with a nationalist identity really doesn’t apply, at least not in my life.”

—Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

“Catalonia is not Spain.”

—slogan of Catalonian separatists

Sovereignty is a kind of riddle. Once a unitary nation-state has been established, it’s historically been quite difficult for a group within that nation to claim independence. The inherent contradictions between a state’s right to territorial sovereignty on one hand, and a people’s right to self-determination on the other, has troubled international law since the early twentieth century. Postcolonial Africa is no different. It’s perhaps not surprising that most movements for self-determination have been achieved either through violence or due to the intervention or acquiescence of an external sovereign power. On the first, think Eritrea, for example. On the second, South Sudan; though it also was involved in a violent struggle for independence against Khartoum. Whether economic and political sovereignty is easily achievable, especially within the context of decolonization, has also been a hotly debated topic amongst nationalists, as the anthropologist Yarimar Bonilla notes. Yet despite numerous efforts by political thinkers — ranging from Hannah Arendt to Senegal’s founding President, Léopold Senghor — to champion federalist, non-sovereign, and non-nationalist alternatives, the nation-state has remained the dominant political model for much of the twentieth century into today.

One can see such tensions at play in the Catalan independence movement. And while much has been made of the implications of Catalonia for European movements (like the Basque and Scottish independence campaigns), less readily acknowledged is the impact this controversy is having on independence efforts on the African continent. In fact, proponents of separatist movements in Nigeria and Cameroon are watching the situation in Europe quite closely, hoping that it might set a more wide-reaching legal and political precedent.

Viewing European and African separatist movements through a common lens, and as part of a shared predicament, invites productive comparisons. And it also holds implications for those of us committed to a leftist, internationalist politics. It forces us to consider why certain secessionist movements receive greater global attention and whether all calls for self-determination should be taken equally seriously.

Several Nigerian writers have already drawn analogies between Catalonia and Biafra. As the writer Onyedimmakachukwu Obiukwu notes, October 1st is now a date fraught with significance for both nations. On that day in 1960, Nigeria achieved independence from British rule. For many Nigerian nationalists, this marks the beginning of the country’s “non-negotiable separability.” Privileging this moment also helps to delegitimize Biafran separatists (as Igbo nationalists became known), which was brutally suppressed by the Nigerian government in a civil war that cost a million lives in the late 1960s. Coincidentally, October 1st of this year was also the date of a referendum unilaterally set by the Catalan government to ascertain popular support for secession (but perhaps more importantly, to send a message to Spain’s ruling party, Partido Popular). Voters were met by Spanish police in riot gear, who used rubber bullets and tear gas in an effort to prevent the poll from taking place.

By noting this concurrence in dates, Obiukwu is able to point to more structural similarities. Separatist conflicts are often perceived as uniquely African problems (simplistically attributed to the continent’s “arbitrary” borders or its “tribal” divisions). Yet as the case of Catalonia shows, Africa is no anomaly. Nor is the continent pathologically inclined toward conflict. Europe, moreover, should not be held up as the normative model of nationalist cohesion. All nation-states subsume certain forms of difference onto themselves, and all are predicated on the suppression of competing nationalist visions. The transition and experiments with political federalism in both Nigeria and Spain over the last few decades have failed to fully resolve such tensions.

At the same time, both European and African separatist movements refract the possibility for conflicts to be prevented through the emergence of more layered, trans-territorial forms of sovereignty. The European Union has eased tensions along many (formerly “hard”) political frontiers. The freedom of movement between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland — a status quo enshrined by the Good Friday Agreement — is now being threatened by Brexit. The potential for regional integration to enable overlapping nationalisms to coexist (and greater local autonomy to be achieved) was anticipated by a number of Pan-African thinkers. In the 1950s and 60s, African leaders — ranging from Kwame Nkrumah to Julius Nyerere — toyed with the idea of economic and political federations capable of tying African countries together and lessening the significance of colonial borders. Pan-Africanism was championed for many reasons —one of which was its potential to mitigate the threat of separatism and irredentism.

Nkrumah’s vision of a United States of Africa and Nyerere’s hope for an East African Federation never came to pass. Nor is it clear that such federalist structures are always guaranteed to resolve or even mollify separatist aspirations. (As the EU’s reaction to the recent crisis in Spain shows, such political structures can sometimes serve to further reinforce/centralize power at the state level). Nevertheless, ongoing efforts to promote continental and regional integration in Africa may very well usher in solutions to the problem of secession.

For all the parallels that one can draw between the Biafran and Catalonian cases, there are also notable differences. While both the Spanish and Nigerian governments (as Obiukwu argues) have been “heavy-handed” in their approach to the respective separatist efforts on their soil, the degree of violence meted out by Nigerian officials in recent years has far outstripped that of Spain. Moreover, while the international frontiers of European states are perhaps no more or less “arbitrary” than those of Africa, African boundaries are arguably less politically legitimate. Many African political thinkers are in favor of either dissolving or remaking the continent’s inherited colonial boundaries — though this need not necessarily be achieved through separatism.

Perhaps most importantly, separatist movements in Europe and Africa look quite different when considered within a broader analysis of the global political economy. According to Nigerian journalist, Segun Akande, many easterners in Nigeria (where the Biafran state was to be established) are “reluctant to lend their voices to the struggle” both because of the memory of “the millions who died of starvation” during the Biafran civil war and “the current economic situation in the East.” Catalonia is the wealthiest region in Spain and occupies a very different position within the world economy. It’s questionable whether a Biafran state (even one that included the oil-rich Niger Delta) could ever enjoy the same experience of sovereignty. And as Pan-African activists have long cautioned, fragmentation is likely to lead to greater economic and political vulnerability on the world stage.

Movements for secession may refract a shared global predicament, but they can have profoundly different consequences in different parts of the world. Where, then, does this leave us?

One thing that recent separatist conflicts make clear: it makes little sense to either categorically support or categorically reject calls for secession. In addition, framing conflicts as a stark choice between “separatism” and “unity” can obscure the voices of those who seek alternative paths (or those who mobilize around secession claims for rhetorical and tactical reasons). In discussing her novel Half of a Yellow Sun, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie remarked that she grew up feeling both Igbo and Nigerian. She attributes the Biafran civil war to political failures, rather than irreconcilable differences or in-born ethnic divisions. For journalist Kayode Robert Idowu, the conflict over Catalan should serve as a cautionary tale for Nigerians. According to Idowu, Nigerian federalism needs to be restructured, but not wholly abandoned.

Just as the “people” are not a homogenous body, the “left” is far from a unified entity — as evinced by recent debates amongst neo-Marxists in Spain. Additionally, separatism can be (sometimes simultaneously) driven by economically and politically progressive forces and conservative ones. Catalan undoubtedly has a right to hold a referendum without facing the threat of state violence. (Until then, it is also difficult to assess the degree of popular support for independence.) But referendums do not simply measure popular opinion; they generate types of political subjectivity. And as the case of Brexit attests, referendums do not always produce progressive results. Working solely through the legal mechanisms of the state can also foreclose more critical forms of political analysis. As Alberto Garzón suggests, it is worth asking whether “the national question” in Europe today is being “used as a populist channel for the frustration generated by the crisis of capitalism.”

In the end, neither pro-unification nor pro-separatist movements are able to solve the riddle: the dilemma of sovereignty. These include fundamental ambiguities at the heart of the nation-state, such as the kind of structural and demographic anxieties that fuel both minoritarian and majoritarian tendencies. For this reason, both pro-unity and secessionist supporters can at times be motivated by chauvinistic and xenophobic tendencies.

Which is why it’s so essential for political activists to understand the broader context in which separatist demands emerge, to consider the stakes and the alternatives, to listen to heterodox and minority voices, and perhaps most importantly, to examine the nationalisms that they themselves hold dear. However flawed and riddled with ambiguities, self-determination remains a powerful and important language for peoples the world over. But it’s also a language that needs to be carefully interrogated.

Catalonia is a country

“Pity the nation divided into fragments, each fragment deeming itself a nation.”

—Kahlil Gibran

“Africa is one continent, one people, and one nation.”

—Kwame Nkrumah

“I was Nigerian and Igbo. I think the idea of an ethnic identity being somehow mutually exclusive with a nationalist identity really doesn’t apply, at least not in my life.”

—Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

“Catalonia is not Spain.”

—slogan of Catalonian separatists

Sovereignty is a kind of riddle. Once a unitary nation-state has been established, it’s historically been quite difficult for a group within that nation to claim independence. The inherent contradictions between a state’s right to territorial sovereignty on one hand, and a people’s right to self-determination on the other, has troubled international law since the early twentieth century. Postcolonial Africa is no different. It’s perhaps not surprising that most movements for self-determination have been achieved either through violence or due to the intervention or acquiescence of an external sovereign power. On the first, think Eritrea, for example. On the second, South Sudan; though it also was involved in a violent struggle for independence against Khartoum. Whether economic and political sovereignty is easily achievable, especially within the context of decolonization, has also been a hotly debated topic amongst nationalists, as the anthropologist Yarimar Bonilla notes. Yet despite numerous efforts by political thinkers — ranging from Hannah Arendt to Senegal’s founding President, Léopold Senghor — to champion federalist, non-sovereign, and non-nationalist alternatives, the nation-state has remained the dominant political model for much of the twentieth century into today.

One can see such tensions at play in the Catalan independence movement. And while much has been made of the implications of Catalonia for European movements (like the Basque and Scottish independence campaigns), less readily acknowledged is the impact this controversy is having on independence efforts on the African continent. In fact, proponents of separatist movements in Nigeria and Cameroon are watching the situation in Europe quite closely, hoping that it might set a more wide-reaching legal and political precedent.

Viewing European and African separatist movements through a common lens, and as part of a shared predicament, invites productive comparisons. And it also holds implications for those of us committed to a leftist, internationalist politics. It forces us to consider why certain secessionist movements receive greater global attention and whether all calls for self-determination should be taken equally seriously.

Several Nigerian writers have already drawn analogies between Catalonia and Biafra. As the writer Onyedimmakachukwu Obiukwu notes, October 1st is now a date fraught with significance for both nations. On that day in 1960, Nigeria achieved independence from British rule. For many Nigerian nationalists, this marks the beginning of the country’s “non-negotiable separability.” Privileging this moment also helps to delegitimize Biafran separatists (as Igbo nationalists became known), which was brutally suppressed by the Nigerian government in a civil war that cost a million lives in the late 1960s. Coincidentally, October 1st of this year was also the date of a referendum unilaterally set by the Catalan government to ascertain popular support for secession (but perhaps more importantly, to send a message to Spain’s ruling party, Partido Popular). Voters were met by Spanish police in riot gear, who used rubber bullets and tear gas in an effort to prevent the poll from taking place.

By noting this concurrence in dates, Obiukwu is able to point to more structural similarities. Separatist conflicts are often perceived as uniquely African problems (simplistically attributed to the continent’s “arbitrary” borders or its “tribal” divisions). Yet as the case of Catalonia shows, Africa is no anomaly. Nor is the continent pathologically inclined toward conflict. Europe, moreover, should not be held up as the normative model of nationalist cohesion. All nation-states subsume certain forms of difference onto themselves, and all are predicated on the suppression of competing nationalist visions. The transition and experiments with political federalism in both Nigeria and Spain over the last few decades have failed to fully resolve such tensions.

At the same time, both European and African separatist movements refract the possibility for conflicts to be prevented through the emergence of more layered, trans-territorial forms of sovereignty. The European Union has eased tensions along many (formerly “hard”) political frontiers. The freedom of movement between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland — a status quo enshrined by the Good Friday Agreement — is now being threatened by Brexit. The potential for regional integration to enable overlapping nationalisms to coexist (and greater local autonomy to be achieved) was anticipated by a number of Pan-African thinkers. In the 1950s and 60s, African leaders — ranging from Kwame Nkrumah to Julius Nyerere — toyed with the idea of economic and political federations capable of tying African countries together and lessening the significance of colonial borders. Pan-Africanism was championed for many reasons —one of which was its potential to mitigate the threat of separatism and irredentism.

Nkrumah’s vision of a United States of Africa and Nyerere’s hope for an East African Federation never came to pass. Nor is it clear that such federalist structures are always guaranteed to resolve or even mollify separatist aspirations. (As the EU’s reaction to the recent crisis in Spain shows, such political structures can sometimes serve to further reinforce/centralize power at the state level). Nevertheless, ongoing efforts to promote continental and regional integration in Africa may very well usher in solutions to the problem of secession.

For all the parallels that one can draw between the Biafran and Catalonian cases, there are also notable differences. While both the Spanish and Nigerian governments (as Obiukwu argues) have been “heavy-handed” in their approach to the respective separatist efforts on their soil, the degree of violence meted out by Nigerian officials in recent years has far outstripped that of Spain. Moreover, while the international frontiers of European states are perhaps no more or less “arbitrary” than those of Africa, African boundaries are arguably less politically legitimate. Many African political thinkers are in favor of either dissolving or remaking the continent’s inherited colonial boundaries — though this need not necessarily be achieved through separatism.

Perhaps most importantly, separatist movements in Europe and Africa look quite different when considered within a broader analysis of the global political economy. According to Nigerian journalist, Segun Akande, many easterners in Nigeria (where the Biafran state was to be established) are “reluctant to lend their voices to the struggle” both because of the memory of “the millions who died of starvation” during the Biafran civil war and “the current economic situation in the East.” Catalonia is the wealthiest region in Spain and occupies a very different position within the world economy. It’s questionable whether a Biafran state (even one that included the oil-rich Niger Delta) could ever enjoy the same experience of sovereignty. And as Pan-African activists have long cautioned, fragmentation is likely to lead to greater economic and political vulnerability on the world stage.

Movements for secession may refract a shared global predicament, but they can have profoundly different consequences in different parts of the world. Where, then, does this leave us?

One thing that recent separatist conflicts make clear: it makes little sense to either categorically support or categorically reject calls for secession. In addition, framing conflicts as a stark choice between “separatism” and “unity” can obscure the voices of those who seek alternative paths (or those who mobilize around secession claims for rhetorical and tactical reasons). In discussing her novel Half of a Yellow Sun, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie remarked that she grew up feeling both Igbo and Nigerian. She attributes the Biafran civil war to political failures, rather than irreconcilable differences or in-born ethnic divisions. For journalist Kayode Robert Idowu, the conflict over Catalan should serve as a cautionary tale for Nigerians. According to Idowu, Nigerian federalism needs to be restructured, but not wholly abandoned.

Just as the “people” are not a homogenous body, the “left” is far from a unified entity — as evinced by recent debates amongst neo-Marxists in Spain. Additionally, separatism can be (sometimes simultaneously) driven by economically and politically progressive forces and conservative ones. Catalan undoubtedly has a right to hold a referendum without facing the threat of state violence. (Until then, it is also difficult to assess the degree of popular support for independence.) But referendums do not simply measure popular opinion; they generate types of political subjectivity. And as the case of Brexit attests, referendums do not always produce progressive results. Working solely through the legal mechanisms of the state can also foreclose more critical forms of political analysis. As Alberto Garzón suggests, it is worth asking whether “the national question” in Europe today is being “used as a populist channel for the frustration generated by the crisis of capitalism.”

In the end, neither pro-unification nor pro-separatist movements are able to solve the riddle: the dilemma of sovereignty. These include fundamental ambiguities at the heart of the nation-state, such as the kind of structural and demographic anxieties that fuel both minoritarian and majoritarian tendencies. For this reason, both pro-unity and secessionist supporters can at times be motivated by chauvinistic and xenophobic tendencies.

Which is why it’s so essential for political activists to understand the broader context in which separatist demands emerge, to consider the stakes and the alternatives, to listen to heterodox and minority voices, and perhaps most importantly, to examine the nationalisms that they themselves hold dear. However flawed and riddled with ambiguities, self-determination remains a powerful and important language for peoples the world over. But it’s also a language that needs to be carefully interrogated.

December 12, 2017

An allegory for freedom

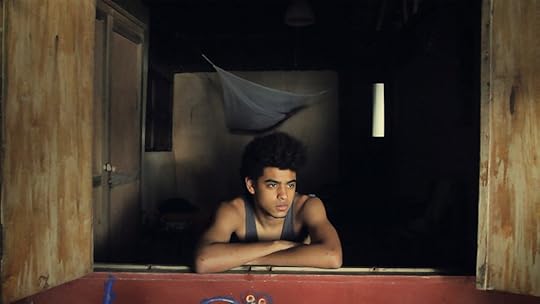

Still from Ayiti Mon Amour.

Still from Ayiti Mon Amour.Blackness is an empty canvas upon which myths of savagery, barbarism, incivility, and unequivocal tragedy are to be imposed. Blackness, like the nation of Haiti herself, is a thing to be punished for committing the crime of daring to exist and resist. Ayiti Mon Amour permits the poetics of blackness, of Haitianness, to shine through the portrayal of a normalcy that includes both strife and tranquility.

It is a depiction very rarely afforded to the black island nation, a loving presentation that could only have been offered by one of Haiti’s own. Guetty Felin’s gaze — a labor of loving truth-telling — permits a fullness of frustration, concern and affection. There is a tendency to reduce Haiti to a country set by misfortune as it is repeatedly ravaged by natural disasters. But within Felin’s world of magical realism (and within a reality where climate change is human-accelerated and global inequality is manufactured), cataclysmic meteorological forces are just one part of imperial karmic retribution continuing to penalize Haiti for endeavoring to free itself in 1791. Hostile western policies too are a material part of this punishment legacy. Whether it was France’s cruelly ironic restitutory demand for its loss of slaves in 1825 after Haiti gained its independence, Clinton-era trade policies that drowned the island in subsidized American rice and destroyed its agricultural self-sufficiency, or President Donald Trump’s all but expulsion of 60,000 Haitians in the United States, the island and its people are being continually disciplined. The film is an homage to the Haitian people: to their resilience and cultural fortitude, a dynamic negotiation of disaster, and a refusal of pornographic fixations upon tragedy and misery that drive so many illustrations of the country’s landscapes.

Ayiti Mon Amour tells the story of Orphée (Joakim Cohen), a young man who, while still mourning the loss of his father, discovers he has a magical power. He finds solace in the sacredness of his intergenerational friendship with Jaurès (Jaurès Andris), an elderly fisherman defined in almost equal part by his love for the ocean and his dedication to his ailing wife (Judith Jeudy). Jaurès and Orphée and their idiosyncrasies, uniquely represent individuals as much as they portray characteristics of the island itself. The characters represent interactions between the yearning of ambitious youths and the longings and care of elders; a desire for freedom and self-determination and the stifling conventions that cut the hamstrings of that self-actualization. The intertwinement of their stories is a skillful illustration of the interconnectedness of human fate and possibility. It shows a visceral humanity, clearly illustrated by the context of black communality in the aftermath of seemingly constant recurring trauma.

Still from Ayiti Mon Amour.

Still from Ayiti Mon Amour.One character in particular, Ama (Anisia Uzeyman), is portrayed as the human embodiment of the motherland. She is the inspiring muse of the novel of an unappreciative writer (James Noël): a spirit who is uncared for and unloved in a way that allows her to be free. Ama, like Haiti herself, grows listless and frustrated as she, a being full of life, waits patiently for the writer to compose such a story on her behalf, but to no avail. Eventually, she, like the Atlantic Ocean after Hurricane Flora, decided that she was not coming back either. She decides to tell her own story and forge her own path.

Without fetishizing black spiritualities, Felin draws upon motifs of the African diaspora — like Haitian Vodou practices, water rituals and honorifics, and the cyclical nature of life and death — to masterfully construct visual allegories about Afro metaphysics and ancestral relations. Ayiti Mon Amour, a film produced through crowdfunding and shot with a largely local cast and production team, is an important addition to the Haitian national cinema and filmmaking scene. The film’s beauty is in its thematic and aesthetic refusal of the western cinema’s ghettoized genre of “third world cinema.” It favors emotional complexity and a vibrancy of arrangements of colors and textures over essentializing tropes about black suffering. It shows the opportunities for creation within trauma. In so many wonderful and unexpected ways, it is a film – and an opportunity – that Haiti deserves.

Benjamin Netanyahu loves Africa

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu loves Africa. He says so himself, at every opportunity and to whoever will listen. But his love for Africa and Africans isn’t just talk, it’s backed up by all the hallmarks of mutually respectful, and mutually beneficial relationships between nations: weapons exports, detention centers, systematic discrimination, offers of financial compensation to get rid of asylum-seekers (for example, Israel will offer Rwanda $5,000 for every refugee in Israel they take) or “infiltrators,” as Netanyahu refers to them.

Love without frequent, well-publicized diplomatic visits is not love at all, so Netanyahu has conducted three such visits to Africa in the last 18 months, a point he was eager to highlight at the inauguration of Kenyan president, Uhuru Kenyatta.

Kenyatta was undoubtedly keen to have a Western leader bless his re-election, which was won in a highly controversial re-run amidst an opposition boycott and violence that resulted in up to 70 deaths, a Supreme Court decision that declared his initial victory invalid and his only viable opponent withdrawing from the election. In the end, he seemed to have settled on Netanyahu.

Netanyahu, of course, was not bothered by the controversy or bloodshed. His remarks were brief, but worth noting here.

Addressing Israel’s “many friends” in Africa — Israel only has diplomatic relations with 11 of the 54 states on the continent — he exclaimed that “we believe in Africa… and this is something that we translate into actual projects.” One wonders if the cash-for-asylum-seeker scheme or weapons contracts were among the projects Netanyahu had in mind here.

Halfway through the address, Netanyahu got to talking about his favorite project; trying to convince world leaders that the war on terror, which for Netanyahu encompasses settler colonialism in Palestine, is a civilizational imperative:

There is a savage disease. It rampages so many countries. Boko Haram, al Shabab, the awful jihadists in the Sinai, this is a threat to all of us. And I believe that we can cooperate with other countries, between us and with others. And if we work together, we can defeat the barbarians. Our people deserve better, we can provide it for them.

This is a central goal of Netanyahu’s diplomatic overture on the continent. Though his trip lasted less than a day, he met with ten African leaders; the presidents of Rwanda, Uganda, Togo, Namibia, and Botswana, the Prime Minister of Ethiopia, and the Vice President of Nigeria.

The Israeli government is keen to shore up support for its confrontation with Iran. It is keen to recruit allies in a never ending, perpetually expanding war on terror. It is keen to achieve observer status in the African Union, and get some of Africa’s 54 votes the next time a resolution is brought before the United Nations General Assembly condemning the colonization of Palestine. Such a resolution is passed at least once a year, always by an overwhelming majority. Israeli governments have long wanted to reverse the “automatic majority” of states in that body that oppose the occupation of Palestine.

This is a difficult task, as Israel has never had strong relations with African countries. As the latter were waging wars of liberation, Zionism was keeping the dream of European settler colonialism alive. The connection between imperialism, colonialism, and Zionism was therefore widely understood among anti-colonial leaders in Africa. This wasn’t a connection formed purely in abstraction, either; Uganda, was even briefly considered as a destination for European Jews in the early days of the Zionist movement.

When Gamal Abdel Nasser led the nationalization of the Suez Canal and subsequent victory against the Tripartite Aggressors, colonized people around the world rallied behind their Egyptian comrades. The early success of Nasser’s Third Worldism won him many African and black allies in the 1950s and 1960s, including Kwame Nkrumah, Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, Patrice Lumumba, and Julius Nyerere. Pan-Africanists found common cause with the Pan-Arab project central to Nasser’s ideology, of which Palestine was paramount. Nasser’s influence in Africa helped bring the question of Palestine firmly into the African political scene, as anti-colonial struggles were achieving victory across the continent.

Just as naturally as the Israeli state found itself in alliance with Apartheid South Africa and Rhodesia, the anti-Apartheid and Palestinian liberation struggles found common cause with each other. Mahmoud Mamdani recounted President Julius Nyerere’s address to a Palestinian delegation in Tanzania in the early 1960s, in which he observed, “We lost our independence, you lost your country.” His words are more true now than they were then; most Palestinians today live outside of historic Palestine.

In South Africa, the African National Congress continues to support the Palestinians diplomatically. Nelson Mandela was of course, a huge supporter of the Palestinians, and of the Boycott Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement, in particular. His grandson, Mandla Mandela, a South African parliamentarian, returned from a trip to Occupied Palestine last week, concluding in a press conference that “Palestinians are being subjected to the worst version of apartheid.” Archbishop Desmond Tutu has long been a supporter of BDS as well.

BDS is also gaining support in the West. People now widely understand that an artist’s choice to perform in Israel not a politically neutral act. As a result, many have preferred to cancel gigs rather than face a justified backlash.

The Palestinians have in fact, enjoyed overwhelming support at the level of international diplomacy, not just by African leaders, but in the whole of the Third World. The Israeli government, on the other hand, has been isolated for so long and so thoroughly, that supporters of the occupation commonly argue that the UN itself is “institutionally biased.”

In 2011, a raft of states has upgraded the status of diplomatic relations with the Palestinians in contradiction to the logic of the failed Oslo Peace Process, much to the dismay of the Israelis.

But things have begun to change since 2013, the Arab regimes began their successful counter offensive against the Arab revolution that has since engulfed the entire region. These, reactionary forces are now seizing upon their moment of triumph to bury the Palestinian cause — once a galvanizing oppositional sentiment across the region — alongside the grave of Arab Spring.

Opponents of Palestinian liberation maintained from the outset that the Arab Spring Uprising was completely unconnected to the Palestinian cause, demonstrating an ignorance of both. Solidarity with the Palestinians has long been a unifying force among Arab oppositional movements, particularly in Egypt. Subservience to Washington DC and Tel Aviv in the face of ongoing Israeli colonization and war has always put the nature of the Arab regimes and the will of the mass of people in sharpest relief. In 2011, it seemed that the regional political order that had ossified over the past four decades — of which the camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt was a central pillar — was coming to an end. It wasn’t until Mohamed Morsi’s tumultuous year in power that the ancien regime in Egypt, backed by its allies Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states, excluding Qatar, were able to strike back.

The Egyptian regime had been deploying anti-Palestinian rhetoric since the uprising began, in an effort to portray it as a nefarious foreign conspiracy. When 20,000 people escaped from Wadi el-Natroun prison that year, state media blamed Hamas. In fact, Morsi is actually imprisoned for his alleged role in that plot, rather than anything he did when he was president.

But the connection between Hamas and the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood is, contrary to the regime’s line, more symbolic than anything else. Hamas was until last year an offshoot of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, but the latter’s national branches have never been more than loosely affiliated with each other.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s brief tenure in power, its diplomatic support from Qatar, and loose connection with Hamas gave the Egyptian generals and other reactionaries all the raw material necessary to craft a convincing narrative which served to externalize the cause of the revolution and the deep economic crisis that came to a head under Morsi, by blaming Hamas, which they had always opposed, and Qatar, which backed anti-regime actors during the early days of the Arab Spring for its own narrow interests.

Nefarious actors across the region, from the Egyptian generals, to the Syrian regime, to the Gulf monarchies, have deployed versions of this narrative with devastating effect.

Despite the fact the Muslim Brotherhood has been badly beaten back by a resurgent authoritarianism, and that Hamas is as regionally isolated as ever, they both feature prominently in rhetoric deployed by the other Gulf states in their conflict with Qatar.

Qatar abandoned its ambition to use the Brotherhood to become a regional power years ago, and Qatari support to Hamas has never amounted to much more than diplomatic liaising, and pledges of reconstruction funding. That support has certainly not been enough to reverse Hamas’s political isolation among Arab governments or the dire humanitarian condition in the Gaza Strip.

The inclusion of the Brotherhood and Hamas in the list of grievances which justify the Gulf states’ confrontation with Qatar therefore serves no purpose other than tying Qatar and the Palestinians to the collective trauma of the Arab Spring.

With the Brotherhood vanquished, Hamas isolated, and Qatar on the defensive, the next target of the counter-revolution is the Palestinian cause at large, which has been reduced to a complication in the Saudi monarchy’s efforts to create a strong coalition with which to confront Iran. A coalition that would be incomplete without the most powerful state in the region: Israel.

While the split between the Gulf states, Egypt, and Israel on one side, and Qatar on the other is a straightforward conflict over regional influence, the split between the former and Palestinian liberation is deep and structural. As the Egyptian revolutionary Mahienour El-Massry put it in her fourth letter from the women’s prison in Al Ab’adeya, where she is held to this day, “the [Egyptian] regime that imprisons thousands of wronged citizens (be it under political or criminal charges) will surely view Palestinians as traitors; just as it views any human demanding its just rights as an agent and saboteur.”

This is just as true for the Arab regimes — all of which exist purely to perpetuate their own existence and enrich themselves at expense of the mass of people — as it is for Israel.

Against the backdrop of Trump’s declaration on Jerusalem, the coming diplomatic normalization between the Gulf states, the Saudis and Israelis, and the conflict with Qatar, anti-Palestinian rhetoric has become more and more common in Arab media outlets, many of which are state-owned. In Kuwait, a writer made headlines when he echoed the right-wing Zionist talking point that “there is no Palestine, no occupation.” The Bahraini King has openly called for diplomatic ties to be established between the Arab states and Israel and later sent a delegation to Jerusalem, something that would have been unthinkable a few years ago.

While covert normalization between Israel and the other Arab states — other than Egypt and Jordan, which have diplomatic relations with Israel — has basically been the norm for a long time, the success of the counter-revolution since 2013 is allowing these governments to be completely open about what used to be hidden for fear of public outrage.

The veneer of the Arab diplomatic and economic boycott of Israel, always thin, is finally collapsing completely.

While this may just be a formalization and acknowledgement of something that has obviously been happening for a long time anyway, the fact that these regimes are able to be so open in their betrayal is a troubling sign of growing apathy, and even outright hostility, regarding the Palestinian cause among their subjects.

For Arab monarchs and Netanyahu, this is a historic opportunity to remove the complication of the Palestinian question from their alliance against Iran. For the Israelis, this has the added benefit of further reducing a long-standing international isolation, while removing the Arab world even more completely from the question of Palestine.

This is the context for Netanyahu’s overture to African leaders. He is hoping that, with the Arab states firmly out of the way, Israel can continue its colonization of Palestine unabated, and reverse its pariah status in the international community, once and for all.

December 11, 2017

The rise, fall, and retirement of Mangosuthu Buthelezi

Mangosuthu Buthelezi (middle) with Bantu Holomisa, a former homeland leader himself, and Stone Sizani, a Robben Island prisoner and then UDF activist in the 1980s, as MP’s. Image Credit: Government of South Africa.

Mangosuthu Buthelezi (middle) with Bantu Holomisa, a former homeland leader himself, and Stone Sizani, a Robben Island prisoner and then UDF activist in the 1980s, as MP’s. Image Credit: Government of South Africa.While South Africa’s Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) is now in decline, between its founding in 1975 and the run up to the first democratic elections in 1994, it played a key, but complicated role in South African politics. For all that time, it was led by Inkosi Mangosuthu Buthelezi, who as leader of the KwaZulu bantustan at various times collaborated with the apartheid state and the African National Congress (ANC). In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the IFP became synonymous with political violence in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) and parts of what is now Gauteng province, including violently disrupting elections in April 1994. On October 30, 2017, Buthelezi — who still served as IFP President — announced his retirement from public politics in South Africa.

Few envisioned this day would come, especially in light of the splintering of his party in 2011 when the party’s national chairperson, Zanele Magwaza-Msibi, broke away to form the National Freedom Party (NFP) when Buthelezi refused to hand over the reins. Buthelezi will not stand for re-election as president at the IFP national elective general conference. In a public letter, Buthelezi expressed confidence in the IFP’s ability to thrive in his absence. “Naturally there is some sadness in seeing this particular chapter of my life draw to a close,” Buthelezi wrote, “But we have been working toward this moment for several years now, so the transition feels peaceful and right.” Velenkosini Hlabisa, current mayor of the northern KZN city of Hlabisa and current KZN Provincial Secretary for the IFP, has been chosen as the IFP national council’s choice for President. Though Inkosi Mzamo Buthelezi, a traditional leader from eMbongombongweni and a distant relative of Mangosuthu Buthelezi’s, remains in place as the Deputy President, the organization looked to Hlabisa as a more experienced leader who enjoys support from all levels of the party.

It is hard to imagine an IFP without Buthelezi; he has been synonymous with not only the party since its founding in 1975 but also the machinations of the KwaZulu bantustan and the civil war that plagued KwaZulu-Natal and the PWV region between 1985 and 1996. For this reason, it has been astounding to watch the platitudes from his fellow politicians. Bantu Holomisa, leader of the United Democratic Movement, praised Buthelezi, using the chief’s izithakazelo (praises): “His astute leadership qualities became evident. . . Shenge was very influential at the negotiating table during Codesa. His vision and commitment could not be ignored.” Mmusi Maimane, leader of the Democratic Alliance, the opposition party that has recently found strong support in former IFP strongholds in KZN, thanked Buthelezi “for the role he played in KwaZulu-Natal in the early 1990s” and appreciation “for the 1994 decision Buthelezi took to participate in the first democratic South African election after he initially refused.” The ruling ANC offered lukewarm well wishes. Notably silent on Buthelezi’s retirement? President Jacob Zuma, Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) founder Julius Malema and Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini, all of whom have engaged in public antagonism with Buthelezi throughout their political careers. Malema perhaps felt no need to comment, having made his point in 2011 when he publicly attacked Buthelezi, labeling him as “an old man who is refusing to go on retirement” because he “wants to die president of the IFP.”

This amnesia is not limited to politicians and is at least partially the product of Buthelezi’s skill in managing his image. During apartheid, he promoted himself via the Inkatha Institute and Inkatha’s 1987 purchase of the storied Ilanga lase Natal, as well as the authorized 1976 biography by Ben Temkin. He sued, or threatened to sue, for defamation just about every journalist and scholar who dared to accurately analyze his rise to power.

His staff recently wrote to the website South African History Online with a request to publish a more sanitized version of his biographical entry. Buthelezi decries all efforts to connect him to the apartheid regime or the violence that marked its demise. It is all part of a “long campaign of propaganda and vilification” promoted by the ANC. The latest manifestation of this self-positioning is the Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi Museum and Documentation Centre, which whitewashes Buthelezi’s roles in fomenting violence and facilitating apartheid in the KwaZulu-Natal region. He marketed a particular narrative of Zulu history that has proved hard to dispel. On the other hand, this amnesia persists despite solid studies of the Inkatha leader from the 1980s that have stood the test of time — academic Gerhard Maré and journalist Georgina Hamilton’s An Appetite for Power (1987) and the ANC activist Jabulani “Mzala” Nxumalo’s then-banned Gatsha Buthelezi: Chief with a Double Agenda (1988).

The naming of the museum and archive tells us much about how Buthelezi wants to be remembered — as Zulu royalty and a legitimate heir to the power he wielded for nearly five decades. Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi was born in 1928, the son of Princess Magogo, the sister of King Solomon Dinuzulu and the tenth wife of Inkosi Mathole Buthelezi. Buthelezi has long made much of this relation to the Zulu royal family — claiming his descent from the first Zulu king through Princess Magogo and the role of “prime minister” to Zulu kings for the Buthelezi with this marriage as evidence. This heritage is far less significant than Buthelezi would have us believe. Mzala has shown that others occupying similar positions in the royal family do not claim prince as title and that there is no established practice that requires Zulu kings to choose a Buthelezi as premier. While Buthelezi’s great grandfather did serve as premier to King Cetshwayo, the title is not hereditary.

Before taking up leadership positions, Buthelezi studied at Adams College (1944-1947) and Fort Hare University (1948-1950) — schools famous for producing African nationalist leaders such as Joshua Nkomo, Seretse Khama, Robert Sobukwe, Nelson Mandela, and others — but he took a very different path from those alumni. From school, he embedded himself within apartheid structures. He worked as a clerk in the Bantu Affairs Department before taking up the chieftaincy of the Buthelezi in 1953 (he was officially recognized by the apartheid state in 1957). While Buthelezi positions himself as the rightful heir due to Princess Magogo’s position as chief wife, his half-brother Mceleli also claimed this right as the first born of Mathole. Historian Jabulani Sithole marks this succession dispute as the beginning of Buthelezi’s cooption in the apartheid state’s counter-revolutionary efforts.

Buthelezi’s concern for his own position, first vis-a-vis his brother and then, the Zulu king, meant that the aspirant leader did his best to straddle the line between resistance that would endanger his standing with the apartheid regime and collaboration that would end any popular support. When his chieftaincy of the Buthelezi was in doubt due to a legal challenge from Mceleli, he refuted any idea of hostility to Bantu Authorities — the apartheid system that would give life to separate development by making every black South African a member of a “tribal authority” and stripping them of citizenship in South Africa in favor of political rights in an ethnic bantustan. When he ultimately participated in Bantu Authorities, he delayed elections in KwaZulu — the marker of the second phase of “self-government” towards faux independence — until he had sidelined several other contenders, including Prince Mcwayizeni Zulu (the regent for Goodwill Zwelithini) and then King Zwelithini himself, for control of the nascent bantustan. Buthelezi used KwaZulu to rise to the leadership of conservative black politics.

Buthelezi defended his participation in Bantu Authorities by calling upon ties to the ANC. At Adams College, he studied with one of ANC President Albert Luthuli’s sons and later consulted with the ANC leader about whether or not he should take up the chieftaincy of the Buthelezi. The ANC denounced Bantu Authorities — Luthuli had been deposed from his position as chief for his politics in 1952 — but did quietly maintain contact with rural leaders such as Buthelezi and Thembu King Sabata Dalindyebo. The ANC leadership did offer tacit approval for the formation of Inkatha, provided that it not operate on an ethnically exclusive agenda and with the idea that it could be used to mobilize rural people. Oliver Tambo would later lament not doing enough to shape Inkatha into the organization the ANC envisioned when it offered approval. This tentative connection with the ANC meant that the apartheid state was not always convinced of Buthelezi’s malleability and at times preferred an actual member of the Zulu royal family. On the other hand, it should not be forgotten that Buthelezi served as state witness against the ANC activist Dorothy Nyembe in the 1968 trial that would send her to prison for fifteen years for her work with uMkhonto weSizwe. When in 1998 Buthelezi’s speechwriter Walter Felgate turned against the leader and testified in camera at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), he revealed that Buthelezi began to receive intelligence briefings from South African agencies as early as 1973 — well before his split with the ANC. Inkatha and the ANC suffered a very public break in 1979 when Buthelezi used a meeting to promote himself as the conservative black leader dedicated to non-violence with whom South African and western leaders could work. Indeed, Buthelezi opposed international sanctions and divestment campaigns and accepted South African and American funding for rallies and to launch a conservative trade union, the United Workers Union of South Africa (UWUSA) as a counter to the Congress of South African Trade Unions, in 1986.

After Buthelezi’s break with the ANC, he increasingly saw Inkatha as the only legitimate liberation movement and began to rely upon force to mobilize support. While most bantustan leaders contributed to violence and repression in the last decade of apartheid, the journalist Mondli Makhanya, who grew up in KZN in the 1980s, got at the particular brutality of Buthelezi’s reign when he declared: “Of all the bantustan leaders who collaborated with the apartheid regime, he was the worst.” For every politician’s platitude, another South African has shared memories of the loss and pain suffered at the hand of Buthelezi and his followers. Then President P.W. Botha’s “Total Strategy” to counter an alleged “total onslaught of international communism” included a campaign of low-intensity conflict that relied upon Buthelezi and Inkatha in KwaZulu and Natal.

The rising tide of student resistance in the early 1980s and the popularity of the United Democratic Front (UDF) after its launch in 1983 challenged Inkatha — and therefore Buthelezi’s dominance in KwaZulu and Natal. Inkatha began paramilitary training for its youth at Emandleni Matleng Camp as early as 1980. In the wake of school boycotts that same year, students refused to return to class when Buthelezi called for order. He asked for Inkatha supporters to organize and protect schools; indeed, his supporters began to organize to harass, intimidate, and attack students in KwaMashu and Lamontville. After the launch of the UDF, these trained young men began forced recruitment campaigns across the Durban and Pietermaritzburg townships in efforts to protect Inkatha hegemony. Civic and youth organizations allied with the UDF set up self-defense units and the region’s violence spiraled.

Despite destruction of government documentation, the Durban lawyer Howard Varney’s submission to the TRC and documents accessed by James Sanders for his Apartheid’s Friends (2006) revealed the extent to which Buthelezi worked directly with the apartheid state from 1985 to fuel this civil war. Late that year, he met with apartheid General Tienie Groenewald to request training for a paramilitary force, perhaps after having been fed rumors that the ANC intended to assassinate him. The apartheid government approved and knew the need to cover-up such support. In what became known as Operation Marion, named to reflect the government’s vision of Buthelezi and Inkatha as its puppets, the South African Defence Force trained 200 Inkatha supporters in the Caprivi Strip in Namibia in the use of weapons and explosives as well as strategies to avoid arrest. The TRC found these Caprivians responsible for most of the deadly incidents between 1985 and 1996 while deployed as KwaZulu Police or as “security” for local Inkatha leaders, chiefs, and headmen — many of whom earned reputations as warlords.

In one of the most infamous incidents, Buthelezi called on Inkatha to resist a stay-away in support of striking Metal and Allied Workers Union (MAWU) workers at BTR-SARMCOL in Howick in KZN in 1985. The following year, Inkatha bussed in supporters to Mpophomeni where the dismissed MAWU workers lived. The Inkatha supporters attacked people and property and Caprivians murdered three MAWU shop stewards. BTR-SARMCOL replaced the striking workers with UWUSA members. At KwaMakhutha in 1987, Inkatha supporters ambushed the home of a UDF supporter and killed eight children and five adults. In December 1988, a joint Inkatha-SAP force killed eleven people at Trust Feed. Then in March 1990, more than 200 people died, and hundreds of homes were destroyed in what became known as the Seven Days War — a week of violence that began in the wake of an Inkatha rally funded by the Security Branch of the South African Police. 1990 also saw the spread of Inkatha’s destruction to the Gauteng townships where local circumstances affecting migrant laborers in the hostels shaped the unfolding of the violence. Inkatha sent the Black Cats gang, which had trained at Inkatha’s Mkhuze camp in 1990, to Wesselton and Ermelo where they were assisted by the SAP and Caprivians to assassinate individuals affiliated with the ANC. Conservative estimates suggest that 20,000 people died between 1985 and 1996 — 13,000 of those in KZN — during this civil war fueled by state cooperation with Buthelezi’s Inkatha.

Since his announcement, other transition-era figures have praised Buthelezi for ultimately participating in the first democratic elections. They selectively remember, obscuring the damage done by Buthelezi’s delay. Buthelezi announced Inkatha’s transformation into a national political party in July 1990 and, claiming different hats that many recognized as one and the same, demanded delegations for Inkatha, the KwaZulu bantustan, and the Zulu King to participate in the Convention for a Democratic South Africa. The Inkatha president consistently put up stumbling blocks while violence raged — refusing to sign the declaration of intent that outlined the principles of a new South Africa and forming an alliance of bantustan leaders that withdrew from the negotiations. Throughout these negotiations, the collaboration between Buthelezi and the state fueled violence — at Sebokeng and Boipatong, among others — that plagued the process. The need to bring Inkatha in forced the ANC to compromise, but Inkatha rejected even those proposals. The government declared a state of emergency in Natal and prepared to hold the elections without Buthelezi — when a week before, Inkatha announced its decision to contest the election. Inkatha won 10.5% of the national vote and 50% of the vote in KwaZulu-Natal, giving Buthelezi control of the province. The late decision of Inkatha to participate resulted in large irregularities in parts of KwaZulu-Natal with illegal polling stations, inadequate observation, and threats to existing observers. Even with Inkatha’s victory in the province, violence continued for two more years. Combined with the demands of Inkatha-affiliated traditional leaders, this delayed the first local elections in KwaZulu-Natal.

Since those elections, Buthelezi and Inkatha have suffered steadily declining support. Buthelezi gained perhaps more legitimacy than he deserved when Nelson Mandela and then Thabo Mbeki appointed him the Minister of Home Affairs. This is not to suggest that Buthelezi enjoyed a frictionless relationship with either president. In fact, in 1995, Buthelezi staged a walkout of Zulu delegates from the National Assembly and clashed publicly with Mandela on numerous occasions. And in 1998, acting as standing president while Mandela was travelling abroad, he launched an invasion of Lesotho to prop up Pakalitha Mosisili’s administration. In both Long Walk to Freedom and the recently published Dare Not Linger, Nelson Mandela reflects on their contentious relationship, simultaneously recognizing Buthelezi’s position as a central figure in South African politics while also pointing out the hurdles that Buthelezi presented on the path to democracy. And his biography of Thabo Mbeki, A Legacy of Liberation, the journalist Mark Gevisser summed up the Mbeki policy towards Buthelezi: “Bring him in, promise to see to his grievances once the country has made it to the other side of the rainbow and hope that the grievances recede as he busies himself with the authority and status accorded to him in the new democracy.” Mbeki would eventually drop Buthelezi as Minister of Home Affairs in 2004, marking a decline in Buthelezi’s national relevance.

The election of Jacob Zuma, the first isiZulu-speaking president of the democratic South Africa, in 2009 had a devastating effect on Buthelezi’s party. In the 2009 general elections, the IFP suffered dismal results, winning only 22% of the votes in KZN, a drop in 12% from the 2004 elections. The successful presidential campaign of Zuma allowed the ANC to gain support in areas of KwaZulu-Natal long monopolized by the IFP, especially Zuma’s home district in Nkandla. Based on these poor results, the IFP began to look for ways to change and regain their ground. With the insinuation from Buthelezi that he would not seek re-election in 2005, the party split its loyalties with the old-guard leaders advocating for former Inkatha Youth Brigade leader and general secretary Musa Zondi, the Youth Brigade and IFP-aligned South African Democratic Students Movement supporting Zanele Magwaza-Msibi, and the National Council advocating for Buthelezi to remain power to preserve unity in the party. These rifts in the party resulted in the expulsion of some in the party, particularly those loyal to Magwaza-Msibi.

This infighting in the party and the eventual split with Magwaza-Msibi in 2011 threatened Buthelezi’s hold on KZN and inspired his paranoia that the ANC was out to undermine him. In the 2011 elections, the IFP lost even more ground in KZN, losing control of 32 of the province’s 61 municipalities. After the elections, the ANC and NFP formed a coalition to co-govern 19 hung municipalities in the province, with Magwaza-Msibi becoming mayor of the Zululand District Municipality. This coalition added fuel to the rumors that the ANC had met with Magwaza-Msibi to form a plan to destroy the IFP while she was still serving in the party. This suspicion towards the ANC came to a head in a 2013 National Assembly session when Buthelezi called out Zuma publicly, shouting “Some of your ministers… referred to the fact that – repeating almost what [you] said to me – you think I should retire…” Zuma laughed off this attack, pointing out Buthelezi’s waning influence and the ineffectiveness of the coalition to see him removed from the presidency. “Certainly, I have no difficulty if the opposition join hands… some people, as parties, have difficulties to have a distinct view on issues; they must hang on others… and be very proud.” The “opposition” Zuma referred to was a coalition spearheaded by the EFF’s Julius Malema and Buthelezi who shelved their mutually antagonistic relationship (if only briefly) for the hope of bringing down Zuma in an ultimately unsuccessful vote of no confidence.

In 2014, the IFP lost its status as the official opposition in KZN at the provincial and national level, receiving only 9.8% of the vote in KZN and 2.4% nationwide, being outpaced nationally by both the DA (22.23%) and EFF (6.35%) as the main opposition to the ANC. In 2016, the IFP made a bit of a comeback, winning six KZN municipalities outright. This 2016 success, however, has to be credited in part to the IFP’s decision to join into a super-coalition with the DA, Congress of the People, the African Christian Democratic Party, Freedom Front Plus, and Holomisa’s United Democratic Movement. This tenuous foothold following the 2016 elections has been tempered by a slate of violent clashes between NFP and IFP supporters. This volatile political climate in KZN, best embodied by the spate of taxi murders in recent weeks, combined with still skyrocketing unemployment (with 47,000 jobs being lost in KZN between 2016 and 2017) and more than a third of KZN residents living below the poverty line (R318 a month), makes the forthcoming 2019 elections critical for the future of the IFP, even more so now in the face of Buthelezi’s retirement and lingering discontent with the rampant corruption of the ANC.

In addition to the political decline of the party synonymous with his leadership, the symbolic power of Buthelezi as leader of the Zulu declined over the decades as the symbolic and practical powers of King Goodwill Zwelithini rose. This was not a product of time and popular opinion, but a political miscalculation on Buthelezi’s part. Inkatha ultimately agreed to participate in the first elections once the ANC and National Party guaranteed the recognition of the Zulu monarchy. This recognition allowed King Goodwill Zwelithini to begin to move away from the Inkatha leader who had managed him as symbolic puppet in KwaZulu and into the arms of the ANC. (Other members of the Zulu royal family such as Prince Israel Mcwayizeni had earlier moved into the ANC/UDF-aligned Congress of Traditional Leaders of South Africa and allied themselves with the ANC). During the early years of his kingship, Zwelithini was reliant upon and even subordinate to Buthelezi, but by the 1990s the king had broken from the IFP stalwart, aligning himself with the ANC. In 1994, Buthelezi pushed back against King Zwelithini and his ANC supporters, passing the House of Traditional Leaders Act through the KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Assembly, an act designed to establish an advisory council of Zulu chiefs which virtually stripped the king of his authority as leader of all Zulu chiefs. The royal house issued an ultimatum that the IFP should repeal the act or face the consequences, sentiments echoed by the ANC. The IFP passed the act anyway, which was seen as a blatant attack against the king. Though it was eventually repealed by presidential intervention, the die had been cast.

Since then, King Zwelithini has rapidly outpaced Buthelezi as the public symbol and heart of the Zulu nation. Though many insist that he is nothing more than a puppet (first for the IFP and now for the ANC), the authority the king wields in KZN is undeniable. With the confirmation and expansion of his position under the Nhlapo Commission, King Zwelithini has enjoyed significant symbolic, political, and financial powers. His position as trustee of the Ingonyama Trust (a land trust designed to manage lands formerly owned by the KwaZulu government that Buthelezi claims is his “brainchild”) puts him in charge of over 30% of KwaZulu-Natal’s landmass and as beneficiary of the leases the Trust collects. King Zwelithini also receives a substantial annual salary from the KwaZulu-Natal provincial government, managed by the Department of Royal Affairs, and innumerable benefits from his participation in the male circumcision campaign for the prevention of HIV beginning in 2009. The 2016 “Zulu 200” celebrations in Durban focused not on Buthelezi’s 41 years in power, but rather King Zwelithini’s 45-year reign (the longest of any Zulu king).

Buthelezi’s role has shifted from the political firebrand to the elder statesman, attending events with King Zwelithini, delivering speeches of support and providing quick, easily digestible soundbites for news articles and television spots. In this context, perhaps the announcement of his retirement should not be surprising — his relevance had long been the result of force and apartheid support and has only waned since the end of apartheid.

December 10, 2017

Emmanuel Macron’s Twitter fingers and other Weekend Specials

First up, Macron continues his streak of African agitation. This week his target –on Twitter — was Algeria.

(2) Speaking of Algeria: December 6 was the anniversary of Frantz Fanon’s death from leukemia at the age of 36. Some thoughts on a couple new books (published here on Africa is a Country) that seek to present the philosopher to us in a new way. [A few, older pieces that are also worth revisiting on Africa is a Country about Fanon’s legacy are here, here, here and here–Ed]

(3) Regarding the ongoing migrant crisis in Libya, we must look to countries of origin, destination, and transit to bear a joint responsibility for the migrants.

(4) In fact, it is better looked as a confluence of many displacements and migration crises.

(5) Muammar Gaddafi’s son is coming back to Tripoli and could stand for next year’s Libyan elections.

(6) Has Angola had a revolution of its own? Or are the new wide-ranging reforms still in the context of a political “musical chairs”?

(7) It appears that in Soviet Russia, sorry, modern-day Nigeria, the Special Anti-Robbery Squad is extorting, assaulting and intimidating citizens. People have had enough, and there is widespread call for wider Nigerian police (ranked worst in the world) reform. #EndSARS

(8) After paying $700m for the last 10 years, in installments, the Swiss government will return the final $320m money the late Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha stashed away between 1993 and 1998.

(9) Another leader from Kano, Sanusi Lamido, puts forth another way to look at the Sahel and how West African nations and North African one can work together.

(10) Kenyan’s national elections made all the headlines. But the down-ballot votes show the success of devolution and suggest a path for addressing the ever-widening inequality.

(11) As international pressure grows on tax-dodging and financial havens, Mauritius looks to diversify its economy.

December 9, 2017

On the arrest and detention of Cameroonian writer and scholar, Patrice Nganang

The arrest of Patrice Nganang, Cameroonian writer and scholar, in Douala on Wednesday, December 6, 2017, caught many people by surprise. He was apparently on the way to Zimbabwe when security agents forced him to deplane, and then they took him away. The only explanation (or suspicion) was that he had recently published an article in Jeune Afrique, about political repression in the “Anglophone” parts of the country. As if the entire country weren’t one vast repressed ground.

Professional associations of writers and scholars like the African Literature Association, and PEN America, have issued statements condemning Nganang’s arrest and calling for his release, and the president of State University New York at Stony Brook, his institutional home, has also spoken up.

There is a Cameroonian quip which reflects the sense of political fatalism to which the population seems held in thrall with the spell of a Paul Biya presence: “Cameroon is Cameroon.” It has the pertinacity of a refrain in Dog Days (2007), Nganang’s joyously dark neighborhood novel told in the voice of a dog named Mboudjak.

The fatalistic quip contains a paradox: the apparent indestructibility of Biya in spite of the great variety of first-rate intellects coming from that country, from Fabien Eboussi-Boulaga, through Marcien Towa to Achille Mbembe and Francis Nyamjoh to Olvalde Lewat, Jean-Marie Teno, Frieda Ekotto and Nganang himself.

To all intents and purposes Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s 2013 film Le President conceives of the president of the title as an autocrat type that is generic. It is tempting to see Paul Biya, president of Cameroon since 1982 (seriously, Robert Mugabe, Yoweri Museveni, Teodoro Obiang), as the sole target of this characterization. I will yield to this temptation without remorse: Bekolo’s compatriot Simon Njami writing the screenplay makes it even more difficult to resist.

Less arresting than the quip, but more cancerous, is a myth among Cameroonians: that Biya should be tolerated because his seeming eternal presence in the national psyche ensures peace in the body-politic. The autocrat could be in France for months on end without anyone asking questions. Meanwhile residents of Douala, the country’s second major city, could go on living like zombies, as they do for long sequences in Jean-Marie Teno’s Chef! But we know from Le President tells us that “peace will go to die in war as long as there’s a head to be crowned king.” The president is an adept at political games; he’s both sovereign and superpower.