Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 265

November 29, 2017

Should Africans care for Emmanuel Macron’s “Africa Speech” in Ouagadougou?

Macron.

Macron.French President Emmanuel Macron delivered his “Africa speech” at the University of Ouagadougou, in Burkina Faso. It has become a ritual for all French presidents in recent memory (Nicolas Sarkozy, Francois Hollande, etcetera) to speak to and about Africa, on African soil. These verbose speeches must always deliver an obituary of Françafrique (how France’s relationships with its former African colonies is known as), again and again. They also give the French president an opportunity to address vague questions about the future of the continent, and a new French vision for its inhabitants. This ritual is the moment for them to utter such platitudes as building a common future in Africa with Africans.

As expected, Macron repeated the same chorus as his predecessors, telling Africans “the French language is yours, too.” He even told his captive audience to “be proud of the French language.” But, of course we know better. As Achille Mbembe once said, without Africa, French would be a mere ethnic language, just like other European ethnic languages.

Like his predecessors, Macron also enumerated all the threats that Africa will be facing for the foreseeable future: terrorism, overpopulation, rapid urbanization, 450 million youth looking for work by 2050, and of course, his favorite one: “7, 8, or 9 children per women.”

Debates about this ritual have become repetitive and boring. But, unfortunately, they are agenda setters for intellectual discussions among African intellectuals and publics, at least in the French speaking parts of the continent. After Sarkozy’s infamous “discours de Dakar”, we will debate Macron’s Ouaga speech for years to come. Once again, books will be written to respond to the French president, conferences will be convened, roundtables will be held, and countless op-ed pieces will be penned. However, we will not engage in any of that here. Because that’s repetitive and boring.

What it means is that I will not comment on the fact that the government of Burkina Faso chose to shut down all schools for 2 days, in honor of Macron’s visit. I will also let others debate the fact that Macron, in the opening lines of his speech, felt the need to invoke Thomas Sankara. Mandela too got a shout out. And he also quoted the Senegalese intellectual, Felwine Sarr.

I will also leave to others the task of commenting on how Macron’s decision to create the conditions for “temporary or permanent restitution” of African artefacts that were plundered and are still kept in European museums and private collections. And he still had the nerve though to say that “we should not forget that in many instances these artifacts were saved for Africa by Europeans who took them away from African traffickers.” And he added, “We must make sure that when those artifacts are returned, they are protected and taken care of.” Also, no need to discuss here that when Macron mentioned the slave trade, it was to remind the audience that it was an African problem first, before the Europeans joined in.

What I found more interesting about this whole thing is not the speech, but the discussion between Macron and the students, in the presence of the Burkinabè president Roch Kaboré.

Visibly irritated at times with the tone and contents of the questions, Macron could not mask his exasperation and condescending professorial demeanor towards his audience, including President Kaboré himself. Questions from the students included reminding Macron that the amphitheater where he is speaking was built by Muammar Qaddafi. Macron said had he been president (Sarkozy was in charge), he would not have favored the military intervention that ousted the Libyan leader. Other questions addressed the issue of the FCA currency as a neocolonial tool of subjugation, the presence of French soldiers in the Sahel – to which Macron replied that the French soldiers deserve one thing from Africans: to be applauded.

But President Kaboré must have felt really annoyed by some of the questions addressed to Macron and related to the lack of electricity in classrooms, for how long the air conditioning will still be operable after Macron’s visit, higher eructation reforms, etc. At some point, Macron yelled to a student: “Think of the mindset that underlies your question … It is like you are speaking to me as if I was still your colonial master. But, I do not want to be dealing with electricity supply in Burkinabè universities! That’s your President’s job!” Kaboré stood up and left the room, and Macron said, pointing at him and chuckling, “Oh now he’s leaving! Stay here! Oh, he’s gone to fix the air conditioning…”

It would be a cheap shot to criticize the students for asking the wrong questions to Macron. I think we should instead ask ourselves why these students are addressing to Macron questions that clearly should have been addressed to their own local and national governments. Well, the answer is simple: African political leaders do not engage with their publics.

Has President Kaboré ever gone to the University of Ouaga and engaged in a discussion with the students? What African president holds a town hall meeting with students, street vendors, farmers, or unemployed youth? It is as if the only form of direct engagement that African publics are worthy of from their leaders is political rallies?

Think about it. A quick google search shows that in the past five years, presidents of African countries have given many talks at U.S. universities and other American think thanks. They take questions from the audience after these events. See here, here, here, here, and here. The list goes on. Now, try to find how many times any of these leaders held even a live press conference in their country to allow local journalists to ask questions.

For all the flaws of the American democracy, at least Donald Trump’s spokeswoman Sarah Huckabee Sanders stands at a podium daily and listens to questions, even if she doesn’t answer them. I’m not aware of any African country where a government’s spokesperson takes questions from the local media daily.

Therefore, it should not come as a surprise that when college students have the chance to ask questions to the French president – with their own president in the room, they take the opportunity to raise their concerns about light bulbs in their classrooms. Until the next French president returns for her/his Africa speech.

November 27, 2017

On Grace Mugabe: Coups, phalluses, and what is being defended

Grace Mugabe, left, with her husband, Robert, and their South African counterparts. Image via Government of South Africa Flickr.

Grace Mugabe, left, with her husband, Robert, and their South African counterparts. Image via Government of South Africa Flickr.Robert Mugabe, a man known for his eloquence, was brought down by a speech. It wasn’t his own. Instead, what did him in was the alarming suspicion that there was a voice which was beginning to speak on his behalf, clamoring to take over his own tremulous one. When his wife, Grace Mugabe, began her “Meet the People Tours” in 2014, rallies held with party loyalists across the country, few anticipated that they would trigger a series of events that would prompt the Zimbabwe Defense Forces to stage a coup, placing the Mugabes under house arrest. A few days later, Grace was expelled from ZANU PF and banned for life, accused of running a “cabal” intent on ruining the country. On November 21st, Mugabe resigned from the presidency after a 37 year rule.

What, some ask, is the feminist response to this moment of militarism and male ego? For many commentators, Grace seems to be the way in. Up until recently, Grace had both earned and cultivated for herself a reputation as the domesticated mistress, uninterested in politics. She met Mugabe while a secretary in the State House in the late 1980s, and both had conducted an affair while married to other partners. The two finally married in a lavish Catholic ceremony in 1996.

Given this start, she was remarkably self-conscious about her public image, monitoring press coverage and the public’s perception of her. In 2013, she told the South African media personality Dali Tambo that she had become “a soft target” in the international press after Zimbabwe’s controversial fast track land reform program. Consequently, she dismissed unfavorable stories about her extravagant shopping and temperament as part of a general smear campaign against her husband. During this period, she fashioned herself as a Mother of the Nation, wearing African print outfits adorned with her husband’s face. She grew dreadlocks, increasingly popular among Hararean women of a certain age, and colored them a fashionable but modest amber.

When she finally made her debut as a political actor in 2014, she proved herself to be a surprisingly effective public speaker. Grace’s late entry into politics was prompted by the intensifying succession battles within ZANU, as members of the party sought to take over Mugabe’s throne. Time was running out; Mugabe was now in his 90s. With his impending death, she needed to secure her vast economic interests. That urgency punctuated her speeches.

Her speeches revealed a trait that Shona speakers derisively call “kupapauka” or “kuzhandukira,” the crass presumptuousness of the unsophisticated. This quality worked to her advantage on the stage, allowing her to commandeer the bully pulpit. What she lacked in political legitimacy she made up for with her brash presence. She would pace across the stage, leveling attacks against members of the party who displeased her. When she was on a roll, she would stop to laugh — and, there is no other way to say this — wickedly, at her own jokes. Grace’s performances of displeasure often went viral on social media, bits of which Zimbabweans took to mimicking. A finger jab, a scowl, and a now iconic command, “stop it!” directed at alleged saboteurs within ZANU.

I was fascinated by how much evident pleasure she took in her own public anger. Her body, coiled up in rage, always on the verge of violent release, stood in stark contrast to the respectable, disciplined body of the typical female politician. In the middle of her speeches, Grace’s voice would rise like a pastor’s and she would begin to shake her head, almost uncontrollably, in indignance. This was a woman loosed. I imagine that these eruptions of rage were her vengeance on us for having dismissed her all these years, for assuming that she was just an inarticulate secretary turned mistress, for the “Gucci Grace” punchlines. As further retribution, to really “fix” us as we say in Zimbabwe, she received a PhD in Sociology from the University of Zimbabwe in a dubiously record two months. In a final ascension, she became the leader of the powerful ZANU Women’s League in 2014.

As her profile in ZANU rose, the slogan “munhu wese kunaAmai!” (something like: “Everyone, side with Mother!”) signaled her gradual consolidation of power. Its Oedipal undertones were, of course, gleefully explored by Zimbabweans. This has always been the underlying issue with Grace’s status as a public figure, one that she severely underestimated in her bid for power. First known as Mugabe’s mistress, her authority has always been inextricable from the erotic. Even as she tried to break away from the aging patriarch to whom she had been linked for two decades, Grace was constantly read as wantonly, irredeemably, sexual.

This is the fate of all political women, and she was no exception. Rumors of her affairs with prominent men were public chatter in Zimbabwe. She had, in the public view, an insatiable sexual appetite, one that prompted many to declare, “Iri ihure chairo!” (this one’s a true slut). Her speeches, paroxysms of anger and laughter of the type considered unbecoming of a respectable woman, only seemed to reinforce her Jezebelian image. In one viral clip, she laughed with impish delight at how easy it was for women to deceive their husbands about the paternity of their children (“You tell him the ear looks just like his!”). This was her way — she touched on, and embodied, primordial patriarchal anxieties with a daring nonchalance.

Grace’s public persona was viewed as especially uncouth in contrast to that of her predecessor, Sally Mugabe, who had been posthumously made into a saint in Zimbabwean public memory. Sally stuck to the public performances expected of a First Lady, establishing women’s co-ops and children’s homes, philanthropic work that was firmly in the realm of the domestic. While Grace allegedly dealt with the problem of being married to a very old man by maintaining a rotating cast of lovers, Sally was said to have, as she died from kidney failure in 1992, selflessly condoned Mugabe’s affair with Grace. Succeeding the Madonna, Grace was cast as the whore. Grace was aware of this binary, and consistently complained about the unfairness of the Sally comparisons. Exasperated, she declared during one speech, “I’m not Mugabe’s whore!”

To free herself from playing a part in a sexist drama, she latched onto a virulent misogyny. The women who might have been her allies became her targets. In 2015, she told Zimbabwean women, “If you walk around wearing mini-skirts displaying your thighs and inviting men to drool over you, then you want to complain when you have been raped? That is unfortunate because it will be your fault.”

If we are to understand Grace the orator, perhaps we might return to ancient Greece for a bit. In the Greek rhetorical tradition, the harlot was a symbol of the kind of seductive speech that tempts listeners away from reason, speech that is all ornament and no substance. Such speech, which could induce irrationality in men, was considered a danger to the civic good. Consequently, many teachers of rhetoric trained their students to rid their speech of all unnecessary flair. Democracy depended upon taming the tongue.

In the past few years, Grace, already branded a harlot, was considered a threat to the nation-state on the basis that she was improperly influencing Mugabe, weaponizing their pillow talk to sway a senile old man. Her speeches, nakedly ambitious, only seemed to confirm that it was she who was in power in Harare. The phallus had been deposed. That she took a special pleasure in humiliating the powerful men in ZANU only intensified the castration anxiety. It was among her favorite queenly rituals, as she summoned them up to the podium in the middle of her speeches to berate them for countless infractions, chief among them disloyalty to her and her husband.

Up there on the stage, she morphed into another archetype, The Mother Who Punishes. Grace instinctively grasped the immense power of this role, but she did not appreciate that such matriarchs are subsequently blamed for the sins of men — accused of driving husbands and sons to murder. This narrative, ahistorical and reactionary, was attached to her with ease. Sally, selfless until death, had brought out the best in Mugabe, but he had grown more ruthless and despotic since marrying Grace. The suffering of millions of Zimbabweans was laid at her feet.

After the expulsion of Vice President Emmerson Mnagagwa from ZANU in early November of 2017, which she orchestrated, it was clear that Grace meant to succeed her husband as president. In recent months, I noticed that she had moved away from her Mother of the Nation look, preferring an aesthetic I called “The Real Housewife of Zvimba” (Zvimba is where Robert Mugabe’s ancestral village is located). She had shorn her earthy, relatable, dreadlocks, and was wearing pin-straight, jet-black hair extensions. When she wasn’t clothed in the requisite party regalia for official business, she dressed in gaudy designer outfits of satin, brocade, and tweed, stilettos on her feet. A mode of power-dressing fit for what the Nigerian feminist theorist Amina Mama might term the femocrat. It seemed that she had given up on trying to convince Zimbabweans, who never liked her anyway, that she was a nurturant mother. Now that she had a taste of real power, there was no need to sartorially disguise her ambition.

Therein lies the problem. In the eyes of the ZANU old guard, her performances too eagerly displayed her newfound power, her ability to exact revenge at will. That, as they demonstrated with an unprecedented military intervention into civilian affairs, was their role. The phallocracy had to be defended from the loose woman with the loose tongue.

In her public life as an orator, Grace courted and even mocked the backlash against her. I’m just not sure that she expected it to be such a swift excision. But this is an ancient tale. As thousands took to the streets to celebrate Mugabe’s resignation on November 21, some members of the triumphant crowd chanted, “We won’t be ruled by a whore!” On this point, many Zimbabweans were in agreement with the military and the old men of ZANU. While she is not worthy of defense, certainly not from this feminist, the expulsion of Grace is a sign of what lies beneath this “new era.” We see it in the emergent cult of personality, the promises to stamp out “social and cultural decadency,” the all-male photo-ops and silent, decorative women. What is old is new again. While men continue to share the spoils of their misrule, it seems there must always be a harlot who can be brought to heel.

Grace Mugabe on coups, phalluses, and what is being defended

Image via government of South Africa Flickr.

Image via government of South Africa Flickr.Robert Mugabe, a man known for his eloquence, was brought down by a speech. It wasn’t his own. Instead, what did him in was the alarming suspicion that there was a voice which was beginning to speak on his behalf, clamoring to take over his own tremulous one. When his wife, Grace Mugabe, began her “Meet the People Tours” in 2014, rallies held with party loyalists across the country, few anticipated that they would trigger a series of events that would prompt the Zimbabwe Defense Forces to stage a coup, placing the Mugabes under house arrest. A few days later, Grace was expelled from ZANU PF and banned for life, accused of running a “cabal” intent on ruining the country. On November 21st, Mugabe resigned from the presidency after a 37 year rule.

What, some ask, is the feminist response to this moment of militarism and male ego? For many commentators, Grace seems to be the way in. Up until recently, Grace had both earned and cultivated for herself a reputation as the domesticated mistress, uninterested in politics. She met Mugabe while a secretary in the State House in the late 1980s, and both had conducted an affair while married to other partners. The two finally married in a lavish Catholic ceremony in 1996.

Given this start, she was remarkably self-conscious about her public image, monitoring press coverage and the public’s perception of her. In 2013, she told the South African media personality Dali Tambo that she had become “a soft target” in the international press after Zimbabwe’s controversial fast track land reform program. Consequently, she dismissed unfavorable stories about her extravagant shopping and temperament as part of a general smear campaign against her husband. During this period, she fashioned herself as a Mother of the Nation, wearing African print outfits adorned with her husband’s face. She grew dreadlocks, increasingly popular among Hararean women of a certain age, and colored them a fashionable but modest amber.

When she finally made her debut as a political actor in 2014, she proved herself to be a surprisingly effective public speaker. Grace’s late entry into politics was prompted by the intensifying succession battles within ZANU, as members of the party sought to take over Mugabe’s throne. Time was running out; Mugabe was now in his 90s. With his impending death, she needed to secure her vast economic interests. That urgency punctuated her speeches.

Her speeches revealed a trait that Shona speakers derisively call “kupapauka” or “kuzhandukira,” the crass presumptuousness of the unsophisticated. This quality worked to her advantage on the stage, allowing her to commandeer the bully pulpit. What she lacked in political legitimacy she made up for with her brash presence. She would pace across the stage, leveling attacks against members of the party who displeased her. When she was on a roll, she would stop to laugh—and, there is no other way to say this— wickedly, at her own jokes. Grace’s performances of displeasure often went viral on social media, bits of which Zimbabweans took to mimicking. A finger jab, a scowl, and a now iconic command, “stop it!” directed at alleged saboteurs within ZANU.

I was fascinated by how much evident pleasure she took in her own public anger. Her body, coiled up in rage, always on the verge of violent release, stood in stark contrast to the respectable, disciplined body of the typical female politician. In the middle of her speeches, Grace’s voice would rise like a pastor’s and she would begin to shake her head, almost uncontrollably, in indignance. This was a woman loosed. I imagine that these eruptions of rage were her vengeance on us for having dismissed her all these years, for assuming that she was just an inarticulate secretary turned mistress, for the “Gucci Grace” punchlines. As further retribution, to really “fix” us as we say in Zimbabwe, she received a PhD in Sociology from the University of Zimbabwe in a dubiously record two months. In a final ascension, she became the leader of the powerful ZANU Women’s League in 2014.

As her profile in ZANU rose, the slogan “munhu wese kunaAmai!” (something like: “Everyone, side with Mother!”) signaled her gradual consolidation of power. Its Oedipal undertones were, of course, gleefully explored by Zimbabweans. This has always been the underlying issue with Grace’s status as a public figure, one that she severely underestimated in her bid for power. First known as Mugabe’s mistress, her authority has always been inextricable from the erotic. Even as she tried to break away from the aging patriarch to whom she had been linked for two decades, Grace was constantly read as wantonly, irredeemably, sexual.

This is the fate of all political women, and she was no exception. Rumors of her affairs with prominent men were public chatter in Zimbabwe. She had, in the public view, an insatiable sexual appetite, one that prompted many to declare, “Iri ihure chairo!” (this one’s a true slut). Her speeches, paroxysms of anger and laughter of the type considered unbecoming of a respectable woman, only seemed to reinforce her Jezebelian image. In one viral clip, she laughed with impish delight at how easy it was for women to deceive their husbands about the paternity of their children (“You tell him the ear looks just like his!”). This was her way—she touched on, and embodied, primordial patriarchal anxieties with a daring nonchalance.

Grace’s public persona was viewed as especially uncouth in contrast to that of her predecessor, Sally Mugabe, who had been posthumously made into a saint in Zimbabwean public memory. Sally stuck to the public performances expected of a First Lady, establishing women’s co-ops and children’s homes, philanthropic work that was firmly in the realm of the domestic. While Grace allegedly dealt with the problem of being married to a very old man by maintaining a rotating cast of lovers, Sally was said to have, as she died from kidney failure in 1992, selflessly condoned Mugabe’s affair with Grace. Succeeding the Madonna, Grace was cast as the whore. Grace was aware of this binary, and consistently complained about the unfairness of the Sally comparisons. Exasperated, she declared during one speech, “I’m not Mugabe’s whore!”

To free herself from playing a part in a sexist drama, she latched onto a virulent misogyny. The women who might have been her allies became her targets. In 2015, she told Zimbabwean women, “If you walk around wearing mini-skirts displaying your thighs and inviting men to drool over you, then you want to complain when you have been raped? That is unfortunate because it will be your fault.”

If we are to understand Grace the orator, perhaps we might return to ancient Greece for a bit. In the Greek rhetorical tradition, the harlot was a symbol of the kind of seductive speech that tempts listeners away from reason, speech that is all ornament and no substance. Such speech, which could induce irrationality in men, was considered a danger to the civic good. Consequently, many teachers of rhetoric trained their students to rid their speech of all unnecessary flair. Democracy depended upon taming the tongue.

In the past few years, Grace, already branded a harlot, was considered a threat to the nation-state on the basis that she was improperly influencing Mugabe, weaponizing their pillow talk to sway a senile old man. Her speeches, nakedly ambitious, only seemed to confirm that it was she who was in power in Harare. The phallus had been deposed. That she took a special pleasure in humiliating the powerful men in ZANU only intensified the castration anxiety. It was among her favorite queenly rituals, as she summoned them up to the podium in the middle of her speeches to berate them for countless infractions, chief among them disloyalty to her and her husband.

Up there on the stage, she morphed into another archetype, The Mother Who Punishes. Grace instinctively grasped the immense power of this role, but she did not appreciate that such matriarchs are subsequently blamed for the sins of men—accused of driving husbands and sons to murder. This narrative, ahistorical and reactionary, was attached to her with ease. Sally, selfless until death, had brought out the best in Mugabe, but he had grown more ruthless and despotic since marrying Grace. The suffering of millions of Zimbabweans was laid at her feet.

After the expulsion of Vice President Emmerson Mnagagwa from ZANU in early November of 2017, which she orchestrated, it was clear that Grace meant to succeed her husband as president. In recent months, I noticed that she had moved away from her Mother of the Nation look, preferring an aesthetic I called “The Real Housewife of Zvimba” (Zvimba is where Robert Mugabe’s ancestral village is located). She had shorn her earthy, relatable, dreadlocks, and was wearing pin-straight, jet-black hair extensions. When she wasn’t clothed in the requisite party regalia for official business, she dressed in gaudy designer outfits of satin, brocade, and tweed, stilettos on her feet. A mode of power-dressing fit for what the Nigerian feminist theorist Amina Mama might term the femocrat. It seemed that she had given up on trying to convince Zimbabweans, who never liked her anyway, that she was a nurturant mother. Now that she had a taste of real power, there was no need to sartorially disguise her ambition.

Therein lies the problem. In the eyes of the ZANU old guard, her performances too eagerly displayed her newfound power, her ability to exact revenge at will. That, as they demonstrated with an unprecedented military intervention into civilian affairs, was their role. The phallocracy had to be defended from the loose woman with the loose tongue.

In her public life as an orator, Grace courted and even mocked the backlash against her. I’m just not sure that she expected it to be such a swift excision. But this is an ancient tale. As thousands took to the streets to celebrate Mugabe’s resignation on November 21, some members of the triumphant crowd chanted, “We won’t be ruled by a whore!” On this point, many Zimbabweans were in agreement with the military and the old men of ZANU. While she is not worthy of defense, certainly not from this feminist, the expulsion of Grace is a sign of what lies beneath this “new era.” We see it in the emergent cult of personality, the promises to stamp out “social and cultural decadency,” the all-male photo-ops and silent, decorative women. What is old is new again. While men continue to share the spoils of their misrule, it seems there must always be a harlot who can be brought to heel.

The slave auction in Libya

The lingering problem of racism in Libya and in the Maghreb generally is old news. Evidence of slavery in Libya was gathered by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) as early as last April. This site has published such pieces as “Algeria’s Black Fear” and “Next Time you See the Mediterranean” to highlight the dehumanizing conditions black sub-Saharan Africans face in Algeria and Libya in their journey to Europe.

CNN’s exclusive report on “People for sale: Where lives are auctioned for $400” showing Libyans selling migrant Africans have, however, brought unrivaled attention to the issue. CNN journalists, Nima Elbagir, Raja Razek, Alex Platt and Bryony Jones, traveled to Tripoli to witness and confirm the information they received from their contacts in Libya regarding modern slavery. The report explains that “inside the slave auctions it’s like we’ve stepped back in time. The only thing missing is the shackles around the migrants’ wrists and ankles.”

In amateur footage included in the report, we hear what can be assumed to be a Libyan person speaking in Tripoli dialect and saying that these migrants are for farm labor, while clapping on their shoulders. There is a sense of physical closeness. The migrants being “auctioned,” as the CNN journalist insists, are seen smiling awkwardly and talking back to the speaking person.

The ensuing torrent of outraged reactions was expected.

Upon the release of the live auction footage, the institutional calls for investigation poured in. The Government of National Accord (GNA) declared that “A high-level committee has been convened encompassing representatives from all the security apparatus to oversee this investigation.”

The African Union (AU) called for a probe into Libya “Slave Market.” The actual AU chairman, Guinean President Alpha Conde, urged for prosecutions against what he referred to as a “despicable trade … from another era.”

Protests by Africans in the diaspora took place in front of the Libyan Embassy in Paris, with participants chanting “Free our brothers!”

A similar sense of brotherhood incited the widely-shared outrage of Paul Pogba, the Manchester United and the France national team football star born to Guinean parents. He tweeted: “my prayers go to those suffering slavery in #Libya. May Allah be by your side and may this cruelty come to an end!”

Nima Elbagir, the experienced Sudanese journalist, rightly expressed her shock when declared that she “has never seen something like this.”

Here, the act of seeing is fundamental. News of the rape of refugee children and that West Africans are being “sold in Libyan slave markets” can be deemed worthy of consistent worldwide attention and support only to the extent that it materially visualizes the suffering of others. It is the same old circulation of humanitarian consumption but with a visual, social media twist.

For large numbers of black north Africans, the banalization of a racial problem permeates the social, institutional, and political strata. When the black Tunisian poet, Anis Chouchene, laments “a society afraid of difference,” he decries the social debasement of black Africans as an inferior race. Scenes of racist and discriminatory practices are central to the social and cultural hierarchy in the Maghreb. Libya is no exception.

But this racism, I think, should be understood, as Fanon puts it, as a case of “a fight against non-national Africans” and not as a modern-day slavery. Against obvious references to chattel slavery, the human trafficking of sub-Saharan Africans by north African smugglers — at play in Tripoli’s migrant “auctions” — is organized around a debt bonding and forced labor that become possible as a result of contaminated imaginary and a complex system of social debasement.

Black Libyans are called “Fezzazna”, to refer to the southern region of Fezzan where they predominately live, but also to their socially distinctive inferior cast. In Benghazi, in the eastern region, a popular local market is commonly named “slaves souk.” Same as in Tunisia, where “Zinji” or “Aswad” (close to “Blakee”) are culturally accepted terms to refer to fellow black people because they are thought to be practical forms of reference which are now devoid of any racial charge.

In the absence of a true transformative revolution, complex issues of negrophobia and xenophobia among Africans continue to exist. As Fanon summarizes, “From nationalism we have passed to ultra-nationalism, to chauvinism, and finally to racism.”

After independence in 1951, the brief existence of King Idris’ hereditary monarchy was replaced in 1969 by Muammar Gaddafi’s Jamahirya, a dictatorship which consistently violated basic human rights for Libyans and foreigners alike. In a country that endured civil war after the fall of his regime, ultra-nationalism divides the western Tripoli-based and internationally recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) and the eastern Benghazi-based Libyan National Army (LNA) led by the problematic Khalifa Haftar. This divide continues to contaminate the national and cultural imaginary in Libya, eventually descending into neocolonial racism.

During the popular uprising to topple Gaddafi and his regime, peculiar events have shaped the relationship between Libyan rebels and sub-Saharan Africans. Black African mercenaries, chiefly from amongst the Tuareg, were heavily recruited to join Gaddafi’s troops to crack down on protests. When the uprising turned into an armed conflict, black African workers and black African mercenaries faced increased hostility from Libyans and acts of revenge and killings were directed at them. A widely-shared video published in 2012 showed Libyan rebels caging black Africans, accused of being mercenaries, in a zoo and force feeding them flags. Amnesty International reported that sub-Saharan African migrants and refugees “became targets of stigma, discrimination and violence.” Where does contamination go? It goes nowhere. It rather, saturates the national imaginary and feeds into the same destructive energies at home and abroad.

In Tripoli, Misrata, Benghazi or Tobruk, the CNN report will not change much. In a nation torn by an ongoing bloody civil war, skyrocketing inflation, a failing economy and mass executions of prisoners, everyone is either in the smuggling business or the anti-smuggling business.

Although the CNN report shows a case of debt bonding, a large number of migrant auctions in Libya are related to ransom trafficking. With the closing of the Libyan route to Italy, sub-Saharan migrants find themselves often in a position where they cannot pay their smugglers to be returned to their homes. Smugglers choose to sell the migrants to the highest bidder or entity, such as a militia). The buyers force the migrants into calling their families to ask to send this ransom money. Traffickers are reported to collect ransoms ranging from 2000 to 3000 dinars per person.

Outside Libya, the report would confirm the Italian and European crackdown on the Mediterranean route. A few days before the publication of the CNN piece, the UN’s human rights chief, Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein, accused the EU policy of “aiding Libyan authorities to intercept migrants and return them to detention as being ‘inhuman.’”

Among many Libyans, news of “slave auctions” is met with bewilderment and shock. European military and political intervention and the coercion of Libya to become an ad-hoc gatekeeper of the migrant crisis has turned an already disastrous situation into an unmanageable one.

November 25, 2017

The new Old Man in Zimbabwe

Watching the unfolding events in Zimbabwe, the world media has given an impressive amount of focus on the military coup that was not a coup, and then to the drama of President Robert Mugabe’s resignation under pressure of impeachment. It was a surprisingly quick process after years of feeling that Mugabe would die in office, as he himself had predicted. The “quickness” of the process fit nicely with the attention span of the western media in particular, as events had all the requisite dramatic moments to keep it at or near the top of the newsfeed while it lasted, and media coverage wrapped up before it became uncomfortably dragged out.

Friday’s inauguration of new Zimbabwe President, Emmerson Mnangagwa, provides a convenient and predictable place for the media to leave the story behind. Just as many reporters and announcers had started to learn how to pronounce his surname (it’s muh-nahn-GAHG-wah), these news agencies will now seamlessly move on to new crises and new stories.

The ending of Mugabe’s rule was the typical African event from Western media’s perspectives — dramatic because it risked violence, and uplifting because it avoided violence while seeming to please Zimbabweans in the streets. So after the transfer of power was made official yesterday, and with many outsiders left with the feeling that a “successful transition” to something more like democracy has occurred, it is fair to assume that it is already too late for the international media to invest much time or thought into the difficult road ahead for Zimbabwe as a nation and for Mnangagwa as Mugabe’s successor.

The whole process couldn’t have been scripted better from the perspective of Mnangagwa’s Lacoste faction and his supporters and allies in the military. That script should be familiar at the moment, and has been well established by the New York Times and The Guardian for example. The script looks less Disneyesque, however, for those who have been following developments in Zimbabwe for decades.

First of all, Mnangagwa’s presidency, while ending a destructive factional competition within the ruling party, ZANU-Patriotic Front (PF), has been first and foremost a victory for the old guard. Zimbabwean ruling party politics remains more or less petrified in a male-dominated world of former liberation movement fighters and generals. Zimbabwe is not experiencing, nor is the ruling party and military leading, an “Arab Spring” sort of democratic revolution — in either a neoliberal or socialist sense — as Zimbabwe remains a nation dominated by the remaining generations of liberation war veterans who have managed to survive and keep alive the ideology of defending “our revolution” over the past week.

While many young people took to the streets to express their emotional release of having President Mugabe step down, it is very unlikely that the “new” leadership of Mnangagwa, the same man who had been Mugabe’s main aid and supporter even before 1980, will be well placed to fulfill their dreams. As the BBC reported, Mnangagwa “struck a conciliatory tone” at his inauguration yesterday, stating: “The task at hand is that of rebuilding our country,” and that, “I am required to serve our country as the president of all citizens regardless of color, creed, religion, tribe, totem or political affiliation.” But how will this rebuilding process be possible without a more inclusive concept of governance?

The authoritarian state is not only still intact, but also has been strengthened by this brief but bold intervention. A state government controlled by the ZANU-PF Central Committee has managed to maintain the semblance of separation from the military, except, of course, at those moments when the political opposition had gained enough support to legitimately challenge ZANU-PF rule. The presidential elections in the 2000s were the main examples of this.

Each time, the opposition, represented by the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), came close to winning (or, in fact, did win but had the election taken away from them by the ZANU-PF controlled state) the military would threaten the population with violent consequences for those who did not vote for the ruling party. Elections in 2000, 2002, 2005, and especially in 2008, were marred by vote rigging, violence, and threats of violence. Through all of this, the ruling party leadership coordinated with the military, the Zimbabwean Electoral Commission, and the Constitutional Court to shut down avenues for the opposition to appeal and find support against abuses by the ruling party.

Mnangagwa did not survive at the center of the ruling party during the 1980s and 1990s without knowing how to use the state and military for the benefit of the Party. The Gukurahundi period (1982-87), which witnessed extreme state violence against opposition and civilians in the Midlands and Matabeleland provinces established the architecture for similar campaigns in the 2000s. Mnangagwa’s leadership role in this earlier period has recently been documented by Hazel Cameron and Stuart Doran. This history means that he is not universally accepted by all Zimbabweans as a reformed democrat.

A party that managed to use the state so effectively to guarantee their control of power in the face of a strong opposition is not now going to forget their past after a week and a few mass rallies, especially when the opposition is much less united and popular as it was a decade ago.

Similarly, the victims and relatives of the victims of 60 years of state violence going back to the Rhodesian period are not going to easily forget or forgive. MDC-T (MDC is split into two main factions) leader Morgan Tsvangarai was quoted yesterday by the BBC, that “the ‘culture of violence’ and ‘culture of corruption’ had to be changed ‘after so many years of Zanu-PF misrule.’” But can it be changed so quickly? Already, reports are surfacing of mistreatment of those in the ZANU-PF G40 losing faction associated with Mugabe’s wife, Grace. Some of them have been mistreated in their detentions, including that of the most recent Minister of Finance, Ignatius Chombo. Chombo was reportedly admitted to hospital yesterday for injuries sustain during his detention, according to his lawyer Lovemore Madhuku. During the past few days, while the spotlight was on Zimbabwe, few in the media asked about the fate of those on the losing side in this ZANU-PF internal war.

Given this long contestation for power by the opposition against the ruling party, the veneer of optimism is quite thin for the Mnangagwa presidency from the point of view of those who have observed the past decades of ZANU-PF’s hold on power. Commenting on the prospects of a Mnangagwa Presidency, noted political scientist Eldred Masunungure, stated in a recent Reuters’ article: “There are no arguments around his [Mnangagwa’s] credentials to provide strong leadership and stability, but there are questions over whether he can also be a democrat.”

Professor Masunungure’s comment points to the quandary facing Zimbabwe. Economic conditions in Zimbabwe are increasingly difficult. There is no clear vision on the part of ZANU-PF on how to get out of the economic crisis now facing Zimbabwe. For many, with the spirit of renewal the events of the last week have produced, there is a hope of some sort of technocratic push to “normalize” relations with China, South Africa, and the West in order to help Zimbabwe get out of this current economic tailspin. Former President Mugabe had a habit of contradicting and removing his Minister of Finance when they tried to suggest that excessive spending on populist projects were killing the economy. Only last month, Mugabe had removed his Finance Minister, ZANU-PF stalwart and Mnangagwa ally Patrick Chinamasa. It would not be surprising to see Chinamasa now returned to his former position, unless Mnangagwa reaches out to the opposition to bring in Tendai Biti, who had served as Finance Minister in the former GNU and who is popular in Washington.

There is then a guarded optimism from some quarters that Mnangagwa will be able to finally bring Zimbabwe back to reality in terms of government spending and foreign investment. It certainly won’t be easy, as any serious efforts to control spending will have to be made during an election year. Attacking corruption, something that has been successfully demonstrated in Tanzania and more recently in Angola, will also be seen as positive signs of a new dispensation in Harare. To do so will require going after ZANU-PF bigwigs who have benefitted from years of collusion in combined military and mining operations in the DRC and, more recently, in Zimbabwe itself, around the contested and highly profitable diamond trade. There is a lot of goodwill from Foreign embassies toward Mnangagwa, and he has been traveling to visit London, Beijing, and Pretoria to work out the future. The problem, of course, is that what he is asked to do now will go against the cronyism and corruption of the past 17 years and earlier. Most likely those put on trial for corruption will be those who were part of the G40 faction. Such moves to attack corruption will help make Mnangagwa more popular and perhaps electable in 2018, but these acts would directly challenge the alliances and client-patron relations that allowed for him to return to Zimbabwe this week. He already showed some of his old ways during his speech at Harare airport (now Robert Mugabe International Airport), when he invoked his familiar slogan, “pasi nemhandu” (“down with the enemy”), which in the Zimbabwean political context has been a popular refrain since the liberation war. It is not the phrase used by someone wanting to promote unity and a fresh start.

Given the opening last week’s events may seem to provide, some members of the opposition may be eager to participate alongside Mnangagwa in some sort of coalition or new Government of National Unity to help move towards the scheduled 2018 elections. In all this excitement, it is perhaps worth considering a wise dose of realism, which Brian Raftopoulos is always capable of providing. Writing last week on the Solidarity Peace Trust website, Raftopoulos considers the likely costs of Mnangagwa’s presidency for the nation and for opposition politicians:

The dominant mood of seeking economic and political stability at almost any cost in Zimbabwe has provided the space for the military to legitimise their intervention in favour of Mnangagwa. The opposition political forces, deeply divided as they are, will be further weakened by these events. They may be drawn into some form of Government of National Unity in which they will have a marginal and negligible role. The new face of Zanu PF, drawing on the massive popular goodwill displayed on the 18 November march, will use this time and space to rejuvenate Zanu PF’s fortunes. As a carefully choreographed scheme, this military intervention could prove a masterly stroke by Mnangagwa and his supporters. However this will be at a high cost for future democratic alternatives in Zimbabwe.

Mnangagwa is quite experienced at methodically working toward his goals. He had patiently withstood the attacks from the G40 over the past few years and quite possibly survived an attempt on his life in terms of an alleged poisoning incident in August of this year. He has clearly done his homework in terms of diplomacy, gaining the support of regional and international powers before he and General Constantino Chiwenga moved to regain control. Mugabe’s failure to gain support from regional powers was quite noticeable in the drama of his demise. Mnangagwa and his allies will have the support of China, the UK, and the US, but he will have to move quickly to impress Zimbabwe’s many critics that this is indeed a new Zimbabwe. The sad reality is that given Zimbabwe’s relatively low strategic importance, the bar for reform will once again be set low from the perspective of the international community. As long as Chinese and British economic interests are protected — mostly in platinum mining and Chinese agricultural projects — there will be little concern for the way Mnangagwa governs. It will be interesting to see what the next few weeks and months will bring to Zimbabwe in a post-Mugabe world. But from the perspective of the past, there is little evidence to invest much hope in the “successful transition” trope still reverberating in the international media.

The New Old Man in Zimbabwe

Watching the unfolding events in Zimbabwe, the world media has given an impressive amount of focus on the military coup that was not a coup, and then to the drama of President Robert Mugabe’s resignation under pressure of impeachment. It was a surprisingly quick process after years of feeling that Mugabe would die in office, as he himself had predicted. The “quickness” of the process fit nicely with the attention span of the western media in particular, as events had all the requisite dramatic moments to keep it at or near the top of the newsfeed while it lasted, and media coverage wrapped up before it became uncomfortably dragged out.

Friday’s inauguration of new Zimbabwe President, Emmerson Mnangagwa, provides a convenient and predictable place for the media to leave the story behind. Just as many reporters and announcers had started to learn how to pronounce his surname (it’s muh-nahn-GAHG-wah), these news agencies will now seamlessly move on to new crises and new stories.

The ending of Mugabe’s rule was the typical African event from Western media’s perspectives—dramatic because it risked violence and uplifting because it avoided violence while seeming to please Zimbabweans in the streets. So after the transfer of power was made official yesterday, and with many outsiders left with the feeling that a “successful transition” to something more like democracy has occurred, it is fair to assume that it is already too late for the international media to invest much time or thought into the difficult road ahead for Zimbabwe as a nation and for Mnangagwa as Mugabe’s successor.

The whole process couldn’t have been scripted better from the perspective of Mnangagwa’s Lacoste faction and his supporters and allies in the military. That script should be familiar at the moment, and has been well established by the New York Times and The Guardian, for example. The script looks less Disneyesque, however, for those who have been following developments in Zimbabwe for decades.

First of all, Mnangagwa’s presidency, while ending a destructive factional competition within the ruling party, ZANU-Patriotic Front (PF), has been first and foremost a victory for the old guard. Zimbabwean ruling party politics remains more or less petrified in a male-dominated world of former liberation movement fighters and generals. Zimbabwe is not experiencing, nor is the ruling party and military leading, an “Arab Spring” sort of democratic revolution—in either a neo-liberal or socialist sense—as Zimbabwe remains a nation dominated by the remaining generations of liberation war veterans who have managed to survive and keep alive the ideology of defending “our revolution” over the past week.

While many young people took to the streets to express their emotional release of having President Mugabe step down, it is very unlikely that the “new” leadership of Mnangagwa, the same man who had been Mugabe’s main aid and supporter even before 1980, will be well placed to fulfill their dreams. As the BBC reported, Mnangagwa “struck a conciliatory tone” at his inauguration yesterday, stating: “The task at hand is that of rebuilding our country,” and that, “I am required to serve our country as the president of all citizens regardless of color, creed, religion, tribe, totem or political affiliation.” But how will this rebuilding process be possible without a more inclusive concept of governance?

The authoritarian state is not only still intact, but also has been strengthened by this brief but bold intervention. A state government controlled by the ZANU-PF Central Committee has managed to maintain the semblance of separation from the military, except, of course, at those moments when the political opposition had gained enough support to legitimately challenge ZANU-PF rule. The presidential elections in the 2000s were the main examples of this.

Each time, the opposition, represented by the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), came close to winning (or, in fact, did win but had the election taken away from them by the ZANU-PF controlled state) the military would threaten the population with violent consequences for those who did not vote for the ruling party. Elections in 2000, 2002, 2005, and especially in 2008, were marred by vote rigging, violence, and threats of violence. Through all of this, the ruling party leadership coordinated with the military, the Zimbabwean Electoral Commission, and the Constitutional Court to shut down avenues for the opposition to appeal and find support against abuses by the ruling party.

Mnangagwa did not survive at the center of the ruling party during the 1980s and 1990s without knowing how to use the state and military for the benefit of the Party. The Gukurahundi period (1982-87), which witnessed extreme state violence against opposition and civilians in the Midlands and Matabeleland provinces established the architecture for similar campaigns in the 2000s. Mnangagwa’s leadership role in this earlier period has recently been documented by Hazel Cameron and Stuart Doran. This history means that he is not universally accepted by all Zimbabweans as a reformed democrat.

A party that managed to use the state so effectively to guarantee their control of power in the face of a strong opposition is not now going to forget their past after a week and a few mass rallies, especially when the opposition is much less united and popular as it was a decade ago.

Similarly, the victims and relatives of the victims of 60 years of state violence going back to the Rhodesian period are not going to easily forget or forgive. MDC-T (MDC is split into two main factions) leader Morgan Tsvangarai was quoted yesterday by the BCC, that “the ‘culture of violence’ and ‘culture of corruption’ had to be changed ‘after so many years of Zanu-PF misrule.’” But can it be changed so quickly? Already, reports are surfacing of mistreatment of those in the ZANU-PF G40 losing faction associated with Mugabe’s wife, Grace. Some of them have been mistreated in their detentions, including that of the most recent Minister of Finance, Ignatius Chombo. Chombo was reportedly admitted to hospital yesterday for injuries sustain during his detention, according to his lawyer Lovemore Madhuku. During the past few days, while the spotlight was on Zimbabwe, few in the media asked about the fate of those on the losing side in this ZANU-PF internal war.

Given this long contestation for power by the opposition against the ruling party, the veneer of optimism is quite thin for the Mnangagwa presidency from the point of view of those who have observed the past decades of ZANU-PF’s hold on power. Commenting on the prospects of a Mnangagwa Presidency, noted political scientist Eldred Masunungure , stated in a recent Reuters’ article: “There are no arguments around his [Mnangagwa’s] credentials to provide strong leadership and stability, but there are questions over whether he can also be a democrat.”

Professor Masunungure’s comment points to the quandary facing Zimbabwe. Economic conditions in Zimbabwe are increasingly difficult. There is no clear vision on the part of ZANU-PF on how to get out of the economic crisis now facing Zimbabwe. For many, with the spirit of renewal the events of the last week have produced, there is a hope of some sort of technocratic push to “normalize” relations with China, South Africa, and the West in order to help Zimbabwe get out of this current economic tailspin. Former President Mugabe had a habit of contradicting and removing his Minister of Finance when they tried to suggest that excessive spending on populist projects were killing the economy. Only last month, Mugabe had removed his Finance Minister, ZANU-PF stalwart and Mnangagwa ally Patrick Chinamasa. It would not be surprising to see Chinamasa now returned to his former position, unless Mnangagwa reaches out to the opposition to bring in Tendai Biti, who had served as Finance Minister in the former GNU and who is popular in Washington.

There is then a guarded optimism from some quarters that Mnangagwa will be able to finally bring Zimbabwe back to reality in terms of government spending and foreign investment. It certainly won’t be easy, as any serious efforts to control spending will have to be made during an election year. Attacking corruption, something that has been successfully demonstrated in Tanzania and more recently in Angola, will also be seen as positive signs of a new dispensation in Harare. To do so will require going after ZANU-PF bigwigs who have benefitted from years of collusion in combined military and mining operations in the DRC and, more recently, in Zimbabwe itself, around the contested and highly profitable diamond trade. There is a lot of goodwill from Foreign embassies toward Mnangagwa, and he has been travelling to visit London, Beijing, and Pretoria to work out the future. The problem, of course, is that what he is asked to do now will go against the cronyism and corruption of the past 17 years and earlier. Most likely those put on trial for corruption will be those who were part of the G40 faction. Such moves to attack corruption will help make Mnangagwa more popular and perhaps electable in 2018, but these acts would directly challenge the alliances and client-patron relations that allowed for him to return to Zimbabwe this week. He already showed some of his old ways during his speech at Harare airport (now Robert Mugabe International Airport), when he invoked his familiar slogan, “pasi nemhandu” (“down with the enemy”), which in the Zimbabwean political context has been a popular refrain since the liberation war. It is not the phrase used by someone wanting to promote unity and a fresh start.

Given the opening last week’s events may seem to provide, some members of the opposition may be eager to participate alongside Mnangagwa in some sort of coalition or new Government of National Unity to help move towards the scheduled 2018 elections. In all this excitement, it is perhaps worth considering a wise dose of realism, which Brian Raftopoulos is always capable of providing. Writing last week on the Solidarity Peace Trust website, Raftopoulos considers the likely costs of Mnangagwa’s presidency for the nation and for opposition politicians:

The dominant mood of seeking economic and political stability at almost any cost in Zimbabwe has provided the space for the military to legitimise their intervention in favour of Mnangagwa. The opposition political forces, deeply divided as they are, will be further weakened by these events. They may be drawn into some form of Government of National Unity in which they will have a marginal and negligible role. The new face of Zanu PF, drawing on the massive popular goodwill displayed on the 18 November march, will use this time and space to rejuvenate Zanu PF’s fortunes. As a carefully choreographed scheme, this military intervention could prove a masterly stroke by Mnangagwa and his supporters. However this will be at a high cost for future democratic alternatives in Zimbabwe”

Mnangagwa is quite experienced at methodically working toward his goals. He had patiently withstood the attacks from the G40 over the past few years and quite possibly survived an attempt on his life in terms of an alleged poisoning incident in August of this year. He has clearly done his homework in terms of diplomacy, gaining the support of regional and international powers before he and General Constantino Chiwenga moved to regain control. Mugabe’s failure to gain support from regional powers was quite noticeable in the drama of his demise. Mnangagwa and his allies will have the support of China, the UK, and the US, but he will have to move quickly to impress Zimbabwe’s many critics that this is indeed a new Zimbabwe. The sad reality is that given Zimbabwe’s relatively low strategic importance, the bar for reform will once again be set low from the perspective of the international community. As long as Chinese and British economic interests are protected—mostly in platinum mining and Chinese agricultural projects—there will be little concern for the way Mnangagwa governs. It will be interesting to see what the next few weeks and months will bring to Zimbabwe in a post-Mugabe world. But from the perspective of the past, there is little evidence to invest much hope in the “successful transition” trope still reverberating in the international media.

November 24, 2017

Weekend Music Break No.112 – Zimbabwe Coup Edition

Robert Mugabe has conservative music tastes. He preferred—according to his old comrade Edgar Tekere—Cliff Richard over Bob Marley (Mugabe later referred to Rastafari as “… drunkards who are perennially high on marijuana”). He also bonded over Jim Reeves (listen to his former friend Wilf Mbanga tell a story about how they sang along to Reeves). Grace Mugabe likes gospel music. She was particularly fond of the more sober tones of local singers Fungisai Zvakavapano Mashavave and Mercy Mutsvene. (One aspect of Zimbabwe’s ruling ideology that still needs to be explored, is how spectacularly it combines Mao and Jesus.)

If you watched the inauguration of Mugabe’s successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa, he favors the Zimbabwean megastar, Jah Prayzah. Mnangagwa danced along to a performance of Jah Prayzah hit “Kutonga Kwaro” earlier today. (Mary, wife of coup organizer General Chiwenga, also danced along). Jah Prayzah likes to perform in military fatigues. The song is associated with the “Lacoste” faction (actually the name of the clothing label connects to Mnangagwa’s struggle name, “Crocodile”). The song talks about the arrival of a new hero. We suppose he meant Mnangagwa.

Here’s ten post-independence, pre-coup struggle songs that made first attempts at leadership change. And no, we’re not including Bob Marley’s “Zimbabwe.” Thanks to everyone who pitched in with suggestions or whose timelines on Twitter and Facebook we spied for inspiration. You’re thanked at the end*

A former liberation fighter, Solomon Skhuza, was popular in the late 1980s and early 1990s. He is remembered for “Love and Scandals,” a reggae-inflected song about the late 1980s Willowgate which implicated government ministers in a scandal buying imported cars at knockdown prizes and reselling them on the open market.

One of Zimbabwe’s superstars, Thomas Mapfumo, imprisoned by the Rhodesian regime and (self)-exiled into the United States in 2001, produced many songs critical of government. We have chosen “Corruption” from 1989.

Lovemore Majaivana’s “Umoya Wami” laments the lack of development in Matabeleland.

In “Mapurisa”, Andy Brown critiques police brutality. Later on, Brown, who died of AIDS in 2012, became a staunch supporter of Mugabe’s land reform polices.

From the late 1990s, Mugabe and ZANU-PF’s dominance faced a serious challenge from the Movement for Democratic Change. The MDC grew out of the trade unions and civil society, responding to Mugabe’s attempt to change the constitution and prolong his rule. Though the MDC beat Mugabe and ZANU-PF in subsequent elections, the combined might of the military, police, ZANU and state media led to its decline by the end of the 2000s. “Bhora Rembabvu” by Leonard Zhakata recalls the stiff competition (that’s what the title means) between the two parties.

In “Bvuma Wasakara”, Zimbabwe’s other superstar, Oliver Mtukudzi, sings “Admit, You Are Now Old.” Widely interpreted as a call to Mugabe to step down, it became MDC’s unofficial anthem in the early 2000s (we both happened to be in Zimbabwe when that song came out).

Trade unionist and protest musician, Raymond Majongwe, ridiculed government ministers who believed to have “discovered” rocks producing oil in Chinhoyi in 2007 in “Dhiziri KuChinhoyi”

Chiwoniso was married to Andy Brown. “Kurima”, from her 2008 “Rebel Woman” album, argues that the land reform program mainly benefited cronies.

In 2008, former MDC MP, Paul Madzore, sang that “Saddam Waenda Kwasara Bob” (“Saddam Hussein is gone, we are left with Bob”). Bob is Robert Mugabe.

In the first half of 2016, with the MDC decimated, protest mostly came from “civil society” groups. Chief amongst them was #ThisFlag, led by Pastor Evan Mawarire. A number of songs celebrated it. ”Simuka Zimbabwe,” by Privilege Gonah, implored Zimbabweans to wake up.

Asante sana! Aluta continua! The struggle continues.

*With thanks to Thembi Mutch, Henry Makiwa and Lizzy Attree for suggestions.

Empire and Ambivalence — Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Maya Jasanoff and Joseph Conrad

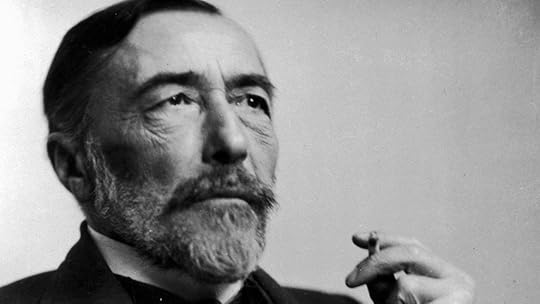

Joseph Conrad.

Joseph Conrad.“Everything is repellant to me here. Men and things, but especially men”—

Joseph Conrad, Letter to his aunt from Congo in 1890.

In August 2017, Harvard historian Maya Jasanoff wrote a travelogue about going up the Congo River with Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness as an overly literal reference point. The article was riddled with racist stereotypes that are often part and parcel of travel writing, particularly when it comes to the Global South. Jasanoff exclaimed her horror at people eating smoked monkeys, likened a boat’s crew member’s signals to the vessel’s captain to Black Power salutes and opined that Congo had probably been better off one hundred years ago. One hundred years ago, the beastly regime of Belgium’s King Leopold was in the throes of looting the region and committing large-scale atrocities.

Jasanoff’s article was widely panned on social media and also in mainstream news outlets, for obvious reasons. Imagine my shock, then, to see that none other than Ngugi wa Thiong’o, the fiercest living critic of colonialism, had published a flattering review of Jasanoff’s book, The Dawn Watch: Joseph Conrad in a Global World in The New York Times. My instinctive response was that Ngugi must not have read Jasanoff’s article from back in August, or else he would surely have recoiled from the review assignment. I assumed he was impressed by her archival work and careful reconsideration of Conrad’s relationship to empire. But, alas, as I combed through the prologue of Jasanoff’s book, all the same problems were front and center: She complained about difficulties getting a visa (try getting a Schengen or American visa as a person with an African or a South Asian passport?); she complained about the political upheaval in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (how the country, also briefly Zaire, is now known); and she reiterated that she wanted to go to Congo because it was still very much the heart of darkness.

It seems that Ngugi saw in the assignment to review Jasanoff’s book an opportunity to revisit Chinua Achebe’s controversial 1977 critique of Heart of Darkness. Achebe’s piece draws attention to the book’s many representational problems which lead to the dehumanization of Africans, from Conrad’s view of Congo’s supposedly “pre-historic” landscapes to his depiction of African people without language and African women as no more than primitive sex symbols – all of this punctuated with a delighted and frequent use of the n-word. The article has been heavily criticized for being overly political, and Achebe was taken to task for his lack of politeness and an openly angry tone. He went on to change his characterization of Conrad as a “bloody racist” to a “thoroughgoing racist.” Twenty years later, in a revived protest against Achebe’s article, The New Yorker’s David Denby’s cheap, mansplaining article “Jungle Fever” revisited it and Edward Said’s criticism of Conrad, proving that liberals reflexively rush to the defense of beloved DWEM (Dead White European Male) figures when they are proven racist or sexist. Now again, twenty years later, that The New York Times would happily publish Jasanoff’s vile travel essay is further evidence of this.

Since we are officially in the age of Trump, in which racism and sexism are openly defended – even celebrated – the tendency towards recuperating figures that progressive thinkers have painstakingly worked to pull down from their pedestals is unfortunately very much in the air. Just recently, a journal article making a case for colonialism went viral. Liberal democrats have somehow become nostalgic for former US President, George W. Bush. Identity politics and, by extension, issues of representation, have come to be seen as trite. The question being asked is: So much is going wrong right now, must we really waste our energies on identity and representation? There is a desire to return to a more innocent time when it was okay to be just a little racist, just a little sexist. This particular desire has now been (mis)articulated through the lens of urgency.

Precisely because of such a political climate, Ngugi’s defense of both Jasanoff’s openly stereotypical views of Congo and Conrad’s ambivalent stance towards empire have come as a blow. It took me by so much surprise that I went back to Jasanoff’s August article on Congo and re-read it carefully, wondering whether I had been mistaken in my initial reading; so staunch is my faith in Ngugi’s thinking. But I do believe he is wrong in this case.

Ngugi’s interest in someone like Conrad is not surprising, but his endorsement of Jasanoff in particular is what is perturbing. On top of it, the timing is mysterious. Ngugi would have had plenty of opportunities during Achebe’s lifetime to have a back and forth about the good and bad in Conrad, the way novelist Caryl Philips did back in 2003. Such a conversation would have been rich and exciting, one that would have furthered our understanding on subjects as diverse as aesthetics, narrative, empire, race and history. Ngugi’s defense has deflated Achebe’s powerful critique. In his article, Achebe is portrayed as having missed the nuance and complexity in Conrad, an argument that has been made before, and now comes from the pen of none other than the most prolific figure in anticolonial literature and theory. This is disappointing at a time when the push for decolonizing the literature curriculum seems to have gotten a bit of steam. Future conversations will be impossible without pitting one legendary postcolonial African against another.

Achebe’s essay comes with its own set of ideological and stylistic issues, and this is certainly an open arena for debate. Scholars schooled in the Western canon, but who are ideologically and methodologically anti-imperialist, often struggle with Conrad’s beautiful writing yet horribly racist views. Conrad was honest about the colonial brutalities he witnessed, but his admiration for empire is hardly hidden. Several European writers suffer such ambivalence. George Orwell’s Burmese Days, or his essay “Shooting an Elephant,” are examples: the reality of imperialism is dirty, possibly immoral, but the work must be done and empire must be defended. E. M Forster’s Passage to India and Rudyard Kipling’s Kim can also be mined for such ambiguities and complexities. But isn’t it time to stop feeling ambivalent about empire? Why are we again and again attracted to this ambivalence when the proof of empire’s destructive and dehumanizing power is all around us? I wish Ngugi who remains for me a symbol of moral and political clarity had not thrown his hat in this ring.

November 23, 2017

The Incredible Hulk

Robert Mugabe, in power for 37 years, has finally resigned. Meanwhile, on the southeastern coast of the continent, Angola’s new president, João Lourenço, tapped by now ‘emeritus’ president José Eduardo dos Santos–who ruled for 38 years–has been stirring things up. Now that Mugabe has stepped aside, maybe the international media will pay attention. Or, if we are lucky, it can hold two African countries in focus at the same time. We can always hope.

Next week, we hope to have some sharp political analysis for you on the situation in Angola. Today, we just want to give you the bullet points on what President João Lourenço, newly dubbed the “implacable exonerator,” has been up to.

Elected August 23 with 61% of the vote (vote counts are disputed, look here), Angolans and Angola-observers expected Lourenço to tow the dos Santos line. Beginning in late October, he has broken ranks. And how.

Key actions:

(1) Lourenço’s first move was to fire the governor of the National Bank of Angola eleven days after his opening speech in parliament in which he stated “we won’t rest until the country has a central bank that strictly meets and in a competent way, its role and is governed by professionals in banking.” Valter Filipe, the director removed from his position, is a lawyer by training. Angola’s financial crisis and desperate foreign exchange situation require solution.

(2) Acting to improve freedom of expression, Lourenço replaced the board of administrators and editors in chief of the state-owned media – Jornal de Angola (the state daily), Rádio Nacional de Angola (Angolan National Radio/RNA), Televisão Pública de Angola (Angolan Public Television/TPA), and Angop (the news wire).

(3) On the same day, November 9th, he cancelled the state’s contracts with Bromangol, a company owned by one of Dos Santos’s children, Filomeno “Zenú” dos Santos, who also happens to be head of the Angolan Sovereign Wealth Fund. Bromangol runs all the laboratory testing for products entering the country to see if they are fit for human consumption.

(4) Various sectors of Angolan civil society, for a long time now, have called for Isabel dos Santos’ removal as head of Sonangol, the national oil company, following her appointment by her father in June 2016. First, a number of lawyers contested the legality of her appointment. Angolans, generally, expressed displeasure and outrage. Recently, Rafael Marques, noted investigative journalist, who has written extensively on Isabel dos Santos’ assets, posted a call for her to resign “Belinha sai só.”

She didn’t need to. The “implacable exonerator” got to her first. On November 15, President Lourenço fired Isabel dos Santos. The same day, he cancelled the contracts between TPA and Semba and Westside Comunicações, communications companies owned by Welwitschia (Tchizé) and Coreon Dú dos Santos, two other dos Santos children. While this does not have the same financial implications, the symbolic force is significant.

(5) November 20, Lourenço removed Ambrósio de Lemos, head of the National Police and General António José Maria, chief of Military Intelligence, in his first move against the generals closest to dos Santos. Zé Maria, as he is commonly known, is rumored to be prowling the halls of the media with the dos Santos decree that secured his position for the next five years in hand.

While this may just be re-arranging or organizing his own system of power, the moves have been wildly popular. Along with spending the night in Cabinda after speechifying there and apparently requesting the removal of the MPLA young pioneers and the women’s group when he landed in Lubango to give a speech on independence Day, claiming he is the president of all Angolans, JLo, is making a bid to be a President who connects with Angolans. Something Zedú (dos Santos) never managed to do. But, as Rafael Marques cautions, civil society and the opposition parties need to step up of this will another government that governs without the people.

November 22, 2017

Paul Biya yesterday, today and tomorrow

Credit: US Department of State, 2014.

Credit: US Department of State, 2014.Cameroon’s President Paul Biya did not partake in any of the public events marking his thirty-fifth anniversary in power last Monday. The country’s armed forces did not parade in front of their supreme commander along Yaounde’s boulevard de 20 Mai. In the Anglophone regions, there were few ebullient spectacles of loin wearing party militants waving banners bearing Biya’s youthful image. Instead, most of this year’s celebrations led by officials of Biya’s Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM) took place indoors in small clusters in their respective regions of origin. Across the country, these “elites” mostly implored their militants to vote for Biya in next year’s elections.

At one such gathering at the Congress Hall in the city of Bamenda, the same venue where Biya launched the CPDM thirty-two years ago, Prime Minister Philemon Yang, the permanent coordinator of the party in the region (where he is also a native), drove the message home when he urged those present to “do everything possible to ensure that the National Chairman is re-elected. And, despite the deteriorating security situation in English speaking regions such as this (where separatist sentiments have blossomed after protests by teachers and lawyers were met with violence by security forces), the political barons and their acolytes (who gathered under the theme “CPDM Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow”) did not address the crisis that necessitated the heavy security presence. That security is an offshoot of the militarization that Bamenda — a bastion of opposition to Biya’s rule — has witnessed in the past year. Instead, these barons focused on matters of the party, which at this point in the party’s history are inseparable from its progenitor.

Pedigree matters

L’Institut des hautes études d’outre-mer, which was founded in 1889 during France’s Third Republic to train colonial administrators, was once located in Paris’s deuxième Avenue de l’Observatoire. In 1966, President Charles De Gaulle decreed its transformation into l’institut international d’administration publique, which in 2002 was absorbed by l’École Nationale d’Administration (ENA). But before its integration into France’s network of grande écoles, l’institut des hautes études d’outre-mer was reputed as a top-flight destination for ambitious colonial administrators from Indochina, Madagascar and its African colonies. It was perhaps this reputation that attracted the young Biya, a graduate of Paris’s l’institut d’Etudes Politiques. He would go on to earn an advanced degree in public law from the institution.

Upon his return to the recently independent East Cameroun, Biya was quickly absorbed into the higher echelons of new president Ahmadou Ahidjo’s nascent state, where he was made chargé de mission at the presidency. In the dozen years he would take to scale the walls of power, he would hold several key positions in Ahidjo’s lair including Director of the Civil Cabinet and Secretary General. Meanwhile the administration that counted him among its haute cadres was at war with remnants of the Marxist-nationalist movement that had inspired Cameroon’s drive towards independence. Though it is unclear how influential Biya was within Ahidjo’s inner circle of eclectic characters, what is certain is that he must have made enough of an impression on the wily Ahidjo for the latter to appoint him his Prime Minister in 1975.