Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 262

December 23, 2017

INTL BLK Radio Show Episode #2

Cuban members of the Afro Razones crew. Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.

Cuban members of the Afro Razones crew. Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.INTL BLK comes back to Dublab in Los Angeles for its 2nd episode (with mic that’s a bit too hot, sorry!). This time we dive a bit into the Black Pacific, and take a deeper look at the contemporary Cuban Hip Hop scene with guest Luna Olavarria Gallegos, one of the producers of the Afro Razones project. Stream below and subscribe to the Africa Is a Radio channel on Mixcloud.

December 22, 2017

George Weah is on the brink of his biggest goal

George Weah playing for AC Milan in 1995. Image Credit Allsport via Wikimedia Commons.

George Weah playing for AC Milan in 1995. Image Credit Allsport via Wikimedia Commons.After weeks of high-drama legal scrutiny over Liberia’s first round of voting, carried out amidst a backdrop of shifting allegiances undoubtedly hammered out over cold beers on muggy nights, the end is drawing near. This coming Tuesday, just one day after celebrating Christmas with their families, Liberians will head to the polls and – finally – select their next president. It’s a watershed moment in the country’s history, though its significance has sometimes felt oddly submerged in collective uncertainty over how, or if, life will be any different in the post-Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf era.

In point of fact, a peaceful transition of power in Liberia will be an achievement that deserves no small celebration. Sirleaf’s three most recent predecessors either met their end violently, or in the case of Charles Taylor, the infamous, sharp-tongued avatar of dapper warlordism, now languishes in a British prison cell. Sirleaf herself, whatever her flaws, has earned a gilded pedestal in the history books as Africa’s first elected female leader, and will almost certainly join the pantheon of Liberian presidents who are appreciated more in their absence than they were during their reign. Darling of the West, forgiver of debt, and signer of contracts, the “Iron Lady” held the mantle of international celebrity, and her lapa will be hard to fill.

But filled it will be, either by her vice president, the septuagenarian statesman Joseph Boakai, playfully nicknamed “Sleepy Joe” by Liberians for his propensity to fall asleep during state functions, or by her political archrival George Weah, football star-turned-senator, former FIFA World Player of the Year and one of Liberia’s most improbable success stories. In an unforeseen twist, a bitter personal dispute between Sirleaf and Boakai over the past year prompted her to quietly offer her support to Weah, and her talent for cloak-and-dagger politics – along with a series of high-profile recent endorsements by prominent figures – has made it appear increasingly likely that once the votes are counted, the former AC Milan striker will become the 25th president of the Republic of Liberia.

This begs a question that, as of yet, doesn’t have a clear answer: what will a Weah administration look like, and how will he govern?

Both icons of Liberian public life, Weah and Sirleaf traversed wildly different paths towards the halls of power. Sirleaf was raised and educated in the sanctums of elite Liberian life, obtaining a Harvard education and serving as Minister of Finance in the waning days of one-party rule, nearly twenty-five years before beginning her twelve-year stint as president. Weah, on the other hand, was born in a winding maze of shacks called Clara Town, one of Monrovia’s ubiquitous working-class slums, where he rode his raw athletic talent into the impossible fantasy that so many young Liberians conjure when they close their eyes at night – fame, fortune and cosmopolitan mobility.

Where Sirleaf entered the Liberian presidency with the support of the Clintons, Tony Blair and the World Bank, her glittering resume imprinted upon the red carpet they rolled out for her, Weah will likely be assuming office with his international audience nervously fidgeting in their seats, whispering disapprovingly to one another about his limited qualifications and thick colloqua accent.

But it’s precisely this dichotomy that most excites Weah’s base of young, perennially underemployed Liberians, many of whom see his haloed rise as a precious expression of their own frustrated ambitions. For all her successes in keeping the peace, the Sirleaf era was infused with the kind of sterility that’s inherent to international development culture. Progress is measured by GDP graphs and strategy documents, delivered via powerpoint in a style that prompts applause in conferences held in Brussels, but this form of progress never really spoke to average Liberians struggling with dysfunctional services and limited economic opportunities. Weah’s perceived proximity to their plight has lent itself to an expectation that he’ll share the spoils of power more equitably than she did, and a hope that they’ll finally supplant the international community as the primary constituency of their president.

After soundly losing the 2005 election to Sirleaf – which his most dedicated supporters still resolutely claim was rigged by her friends in Europe and the United States – Weah bolstered his leadership credentials with a masters degree from DeVry University, an American for-profit college. In 2014, he won the senate seat of Monrovia and its surrounding suburbs, crushing Sirleaf’s son Robert by nearly 70 points in a campaign that served as an obvious precursor to a second run at the presidency.

By all accounts, Weah’s political success is a product of his personal style as much as his iconic status. Even supporters of his rivals describe him as warm, personable, and generous – invaluable qualities for garnering trust in a country accustomed to venality and selfishness in its elected officials. One Liberian I spoke to who campaigned for a candidate that lost in the first round of voting said Weah personally called to console him over the defeat, in contrast to the candidate he’d supported, from whom he says he’s yet to receive a word of thanks. Over the years, Weah’s developed a reputation for offering financial and moral support to people he may know only in passing, and in Liberia those kinds of stories travel fast and far.

But while Weah possesses admirably gracious personal qualities, he’s thin on concrete ideas, at least in public – which is a big reason why he’s received such lukewarm support from Liberia’s professional and educated classes, many of whom worry that his limited grasp of the policy challenges the country faces could prove dangerous. He’s liked, but thought of as an unknown quantity, and if he does become president he’ll be inheriting a tough hand.

Inflation in Liberia has skyrocketed over the past few years, partly due to a questionable economic strategy pursued by Sirleaf and backed by international experts who preached the transformative magic of foreign investment. After commodity prices tanked in recent years, most of the iron ore conglomerates that constituted the backbone of the government’s growth strategy pulled out. Neither Weah nor Boakai have proposed a convincing solution to get the economy back on track or shift course to a more just distribution of resources. The blue helmet-clad UN security blanket is packing its last suitcases, and should he win, Weah will enter office with expectations from his base that will likely prove difficult to meet.

The wildcard, as is generally the case with charismatic political figures who are relative novices to the rigours of governance, is who he chooses to surround himself with. Here there is cause for concern. While corruption is far from the most pressing structural challenge Liberia faces, it certainly doesn’t help, and some of Weah’s close confidants and supporters have a history of eyebrow-raising behavior. Alex Tyler, the former speaker of the house and a key Weah ally, has been accused by Global Witness of taking bribes from a mining company and having lucrative ties to illegal logging.

Weah’s choice of running mate, Jewel Howard-Taylor, is the ex-wife of former president and convicted war criminal Charles Taylor, who remains immensely popular in broad swaths of the country. While the international media’s breathless alarmism over the prospect of Taylor manipulating Weah from his prison cell is overblown and silly, Jewel is a force in her own right, and not necessarily for good. In recent years she’s attempted to criminalize homosexuality and have Liberia formally declared a Christian country. She is likely to be a vocal, powerful member of Weah’s circle, and while she possesses a reputation for competence, as a senator she was also known to be vindictive towards her rivals.

Weah’s most attractive personal qualities may, in the end, prove to be liabilities, as there will be intense competition for his ear and it remains to be seen whether he will be willing to be harsh towards those who abuse his favor for their own personal gain. He will also be inheriting a vibrant, critical civil society and press, and he will have to resist the temptation to silence voices that will inevitably attack his leadership. The honeymoon won’t last long, and there’s no sign that Weah has a workable plan to fix the dysfunction that seems to exist in nearly every corner of Liberian social service delivery.

Still, there is reason for cautious optimism. Despite his lack of ideological clarity, by all accounts Weah’s fondness and concern for average Liberians is genuine and rooted in shared experience. He will enter office with a rabidly supportive base – at least at first – which, should he prove skillful, will afford him the political strength to exert control over his circle and pressure his advisors to perform. For many young Weah voters, his ascendancy to the executive office will represent a joyous rejection of the notion that their leaders have to emerge from behind barriers they can’t cross, potentially marking a new era of politics – regardless of whether he’s able to live up to their lofty projections.

Whether Weah can harness his popularity to advance an agenda that improves the lives of all Liberians, rather than a fresh cadre of well-connected elites, remains to be seen. The arena he’ll step into if he wins on Tuesday isn’t one for games. But like so many times in his charmed life, it will have a crowd on its feet, cheering and praying for him to bring them victory.

December 21, 2017

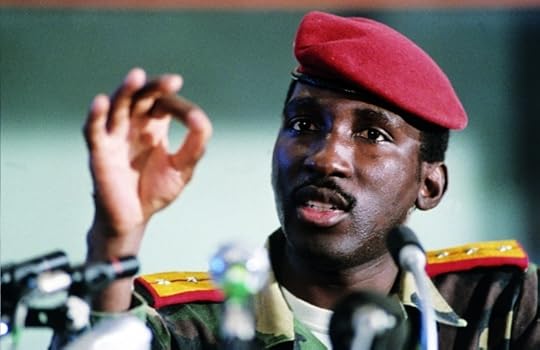

Thomas Sankara’s Star

Thomas Sankara

Thomas SankaraIn Burkina Faso, at the start of his first official visit to Africa, French President Emmanuel Macron knew how to play to his audience. Delivering a keynote Africa policy speech before hundreds of students at the University of Ouagadougou on November 28, he began by trying to placate the sceptics in the audience with a famous quote from the country’s late revolutionary leader, Thomas Sankara, urging young people to be audacious and “dare to invent the future.”

The students roundly applauded, perhaps not expecting such an explicit homage to their hero from the leader of Burkina Faso’s former colonial power — which many Burkinabè believe had a hand in the 1987 military coup that brought Sankara’s death. Macron then went on to score further points by pledging to declassify French intelligence files on Sankara’s assassination, a veil of secrecy that has hindered Burkinabè judicial investigators in delineating the external links to the dozen suspects charged in the crime, among them former president Blaise Compaoré (currently in exile in neighboring Côte d’Ivoire). Just a month before, on the anniversary of Sankara’s assassination, demonstrators had marched on the French embassy in Ouagadougou to demand just that.

In giving a nod to Sankara, Macron was simply following the lead of his Burkinabè hosts. Since Compaoré was forced to flee by a popular uprising in 2014, his successors have often routinely extolled Sankara. President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, elected at the end of 2015, has proclaimed that Sankara’s ideas “will last the ages.” Other government and ruling party officials readily throw out Sankara’s name when it seems suitable, such as the October 15 anniversary of his death or the August 4, 1983, start of his revolution, or on his December 21 birthday.

Many of those now in authority had been part of the Compaoré system and can hardly be considered followers of Sankara. Yet they face a problem: They were swept into office by an insurrectionary tide and confront a mobilized citizenry, many of whom are inspired by Sankara and remain skeptical of the current officeholders. So playing to the popular mood with a few vacuous words about the late revolutionary is useful — and costs very little.

Words and deeds

Sankara’s enduring popularity rests not only on his words, however much they resonate with today’s disenchanted and angry youth. It is also based on his deeds. Even though most Sankara admirers are very young or were not yet born when he was in power, they can often cite a long list of accomplishments from the revolutionary era. Several chapters in my new book, Burkina Faso: A History of Power, Protest and Revolution, and an earlier biography of Sankara explore these in some detail.

Although Sankara’s government lasted only a little over four years, many Burkinabè — whether they liked the revolution or not — agree that it brought more changes to the country than occurred throughout the previous quarter of a century of national independence. Not least was the change in the country’s name from Upper Volta, the old French colonial designation, to Burkina Faso: an assertion of African identity that draws on two indigenous languages to proudly signify “Land of the Upright People.”

In both foreign and domestic policy, Sankara’s National Council of the Revolution (CNR) marked a sharp rupture with the past. Although Burkina Faso continued to receive aid from the West, the CNR also established close relations with Cuba, China and the Soviet Union and angered France and the US by championing anti-imperialist movements from Palestine to Central America.

At home, the Sankara government challenged the old political and social elites by dragging hundreds before revolutionary tribunals to answer for their corrupt deeds. It adopted policies in education, health, agriculture and other spheres that heavily favoured poor, predominantly rural citizens, instead of the better-off city dwellers who previously were the main beneficiaries of state policies and resources. Most famously, Sankara took dramatic steps to promote women’s rights and environmental conservation, at a time when few other African leaders even talked about such issues.

The revolutionary process in Burkina Faso had notable flaws, however. The CNR succeeded in stimulating popular mobilization across the country, especially for community self-help projects. But when such initiative flagged or sectors of the population expressed misgivings, some of those in power responded with coercion. The most widespread abuses came from over-zealous activists of the local Committees for the Defense of the Revolution.

Sankara explicitly denounced and sought to rein in such excesses. Yet some of his comrades — most often Stalinist hard-liners — considered anyone who doubted or questioned CNR directives as a “counter-revolutionary.” Generally aligned behind Compaoré and in defiance of Sankara, they went so far as to arrest outspoken trade unionists, seriously tarnishing the revolution’s image.

From there to the murder of Sankara and a dozen of his comrades was but a short step. And while Compaoré’s new regime initially employed a veneer of communist jargon, that ideology was soon readily jettisoned to accommodate a renewed relationship with France and the wholesale adoption of neoliberal economic policies.

A hero resurrected

As president, Sankara bore ultimate responsibility for the CNR’s shortcomings. But since he himself fell victim to Compaoré’s takeover, most of his followers have been able to largely overlook those blemishes and instead highlight the revolution’s many achievements. Indeed, set against the brutality, corruption, profiteering and crass subservience to France that marked Compaoré’s rule, Sankara’s image grew only brighter over time.

Annual commemorations at Sankara’s gravesite in Ouagadougou at first drew only small crowds, given the political risks. But by the late 2000s many more assembled, sometimes many thousands. Alongside a plethora of “Sankarist” political parties, some of which elected a few deputies to the National Assembly, a variety of new youth groups hailing Sankara as their hero also emerged. One, Balai citoyen (Citizens’ Broom), led by the rapper Smockey and reggae artist Sams’K Le Jah, was especially influential.

In the months of demonstrations against Compaoré in 2013 and 2014, symbols of Sankara were virtually everywhere. Protesters carried his portrait and his recorded voice blared out over sound systems. Quotations from his speeches featured in popular chants. Even politically moderate opposition leaders often concluded with the emblematic slogan of Sankara’s revolutionary government: “La patrie ou la mort, nous vaincrons!” (Homeland or death, we will win). On October 30, 2014, at the start of the insurrection, as demonstrators marched on the National Assembly building to burn it down, they chanted “When the people stand up, imperialism trembles,” among other Sankara slogans.

After Compaoré’s flight, there was an explosion of overt adoration for Sankara: the risks of repression had largely been lifted and for most politicians the benefits were evident. During the year-long political transition (2014-15), younger and older activists suddenly wielded unusual influence in the halls of power. Most notably, Chériff Sy, a journalist and well-known Sankarist, became head of the interim parliament and then, from hiding, backed the popular resistance to a brief coup attempt by Compaoré’s former presidential guards.

From the transition onward, key Sankara anniversaries regularly drew large crowds. Plays, films and songs drew on his image and words. Publishers released various titles, including books for young adults and reminiscences by some of Sankara’s former comrades. An international committee was established to gather ideas and funds to build a major memorial to Sankara. Led by civil society figures and with government support, it will include a mausoleum for Sankara, a conference hall, multimedia center and other sites.

Paradox

While admirers of Sankara are buoyed by the fanfare, some are also aware of the paradox of the current situation. The overtly Sankarist political parties remain weak. They failed to capitalize on the momentum of the insurrection, could not field a common slate in the 2015 elections, and the largest of them won only five seats in the 127-seat National Assembly — just one more than it had in Compaoré’s last legislature. Their leaders play secondary roles, most in the coalition of parties backing the Kaboré government, a few in the opposition.

In the estimation of Ra-Sablga Seydou Ouédraogo, executive director of the Ouagadougou-based Institut Free Afrik, Sankara appears to be “everywhere, yet nowhere.” Sankara’s emphasis on building self-reliance is absent from official development policies, which continue to chase foreign aid and submit to donor dictates. Although Sankara was known for his integrity, corruption remains a “gangrene” in the executive, judiciary and legislature. Beyond its limited immediate practical influence, Ouédraogo argues, the popularity of Sankara’s ideas should above all be seen as an aspiration “to change the miserable reality, a rebellious conscience to rehabilitate humanity’s suffering, in Burkina Faso and in Africa.”

In that spirit, a number of key activists, most prominently the leaders of Balai citoyen, regard the future of the Sankarist current in broad terms, far beyond an electoral project. They do not tie themselves to the parliamentary parties, carefully guard their political independence and continue to champion popular action in the streets and workplaces.

During Macron’s visit, Gaston Olivier Somé was one of the University of Ouagadougou students able to post an online comment as part of an interactive dialogue with the French president. He put it this way: “The African youth, these thousands of Sankaras, are assuming their role. They’ve opened their eyes, to never close them again.”

December 20, 2017

The Dutch disease (and its prescription)

Zwarte Pietin 2. Image credit Gerard Stolk via Flickr.

Zwarte Pietin 2. Image credit Gerard Stolk via Flickr.Three weeks ago I, together with a group of fellow Dutch antiracist activists, planned to go to Dokkum, a city in the Friesland province of the Netherlands, to protest the Intocht, a celebration that serves as the symbolic arrival of Sinterklaas. If you’re unfamiliar with the Dutch version of Santa Claus, here he appears as an old white man on a horse, along with a blackface “helper” known as Zwarte Piet or Black Pete. Black Pete was invented more than 150 years ago and bears the racist symbolism of the bloody Dutch colonial past. The figures are acrobatic, silly and have historically spoken with a caricatured Surinamese accent (an allusion to immigrants from the former Dutch colony in South America). In the weeks between the Intocht and the Evening of the Gifts, on the 5th of December children sing songs with lyrics such as “Even if I’m black as coal I still mean well.”

On the day of the protest, we never arrived. Racists blocked the highway in order prevent us from reaching the city. The police made no effort to stop the blockade. It’s not the first time that activists were prevented from protesting during the Intocht. The resurgence of the movement against Black Pete started in 2011, when two black Dutch activists, Quinsy Gario and Jerry Afriyie, were violently dragged away and arrested at the intocht for wearing “Black Pete is Racism” t-shirts. Africa is a Country covered those first protests extensively. Ever since, protests have routinely ended in mass arrests (with one hundred arrests in Gouda in 2014 and two hundred in Rotterdam last year). The arrests are usually accompanied by brutal police violence mainly aimed at black activists.

However, this year was different. This time we were not prevented from making use of our right to demonstrate by the authorities, but by a mob of Frisian racists. It shows the geographic unevenness of progress against racism in the Netherlands: outside of the larger cities in the western part of the country, there is not yet a lot of support for change. It also points to how empowered the far-right feels to interfere with anti-racist activists.

Even in spite of this recent history of reactionary backlash, the movement against Black Pete has had some success. A poll from a television program called EenVandaag showed that 68% of Dutch people want to keep Black Pete the way he is. This is down from 89% in 2011. During this year’s Intocht in Amsterdam, only Petes with soot stripes participated, while the city of Rotterdam announced it wanted to “phase out” Black Pete altogether; this year they allowed Black Petes in blackface to make up only half of the crowd. Already a number of elementary schools, mainly in the larger cities, have banned the racist caricature at the request of parents.

This is no surprise given the base of the activists in the larger cities. At the same time it reflects how the right-wing press routinely misrepresents the arguments of antiracists, and also how there is a persistent silence on racism from the nationally organized parties on the left such as the Greens and the Socialist Party.

But, the measure of success of the struggle against Black Pete cannot be measured on this front alone. In the slipstream of this struggle the Dutch black community is becoming increasingly self-organized. Some activists have set up an archive with particular attention to the black radical tradition in the Netherlands. There is more attention to our brutal colonial history and we have seen the formation of a new antiracist party led by Sylvana Simons.

This is all done in a political climate which has rapidly shifted to the right. Our national elections last March saw the entrance of a second far-right party to the parliament: Forum voor Democratie. It’s leader, Thierry Baudet warns against the “homeopathic dilution of the Dutch people,” admires Julien Blanc, the dating coach whose dating advice for men includes using force and emotional abuse and wants a re-appraisal of Dutch colonial history.

These sentiments are not limited to parliament. So, for example, the person who organized the blockade with help of the right-wing tabloid “de Telegraaf,” Jenny Douwes, has been close to rightwing Dutch politician Geert Wilders and follows American alt-right Nazi Richard Spencer on Twitter. The far-right use Black Pete to persuade white people that “their” culture is under attack from “foreigners” and the left and that they have to “defend their traditions.”

The American socialist WEB Dubois argued during the post civil war era that the formation of racism in the US afforded white workers a psychological wage. They might be terribly exploited, but at least they could feel superior to people of color. In this way plantation owners “drove… a wedge between the white and black workers.” Dubois remarks that “there probably are not today in the world two groups of workers with practically identical interests who hate and fear each other so deeply and persistently.”

The far right tries to utilize Black Pete in a similar vein. It is no surprise that the Dutch political elite has not spoken out against Black Pete. When asked about the blockade, the prime-minister of the new right wing government Rutte responded that “children shouldn’t be confronted with angry protesters.” Evidently Rutte is just fine with exposing children to racist caricatures. (The government uses anything to distract attention from the huge tax-breaks for large corporations and attacks on labor rights and livings standards of ordinary people that the new government announced.)

Confronted with this shifting terrain, there are two things that activists should be well to heed. The first is to try to offer a perspective to all those who do want change. This year’s racist blockade and subsequent response by the authorities did win a lot of new people to the cause. The popular liberal comedian Arjen Lubach’s response, is evidence of this change. However, this broad support doesn’t yet translate itself to larger mobilizations. We also need to make visible the amount of people that do want change as a measure of security from far-right and state terror during Intochten protests. (Antiracist activists are now included in the same terrorism monitors as fascist organizations.)

Secondly, because the struggle against Black Pete cannot be won within a climate in which the far right is increasingly successful at asserting their world view in the mainstream media, antiracists should see the struggle against the far-right as a central priority. In March 2018 there will be local elections and the far-right is trying to use its momentum to build bases in different cities. This will mean even more attacks on the socially marginalized, poor and immigrants in the Netherlands.

No-one has any illusions that racism in the Netherlands will disappear with Black Pete. The caricature, which reproduces ideas of black inferiority, has grown out to be one of the main symbols of racism in this country. Overthrowing these symbols, just like the Confederate statues in the US or statues of Cecil Rhodes in South Africa, is an important step in building the movements which are able to challenge all forms of oppression and exploitation.

December 19, 2017

The Cyril Ramaphosa model

The election Monday night of Cyril Ramaphosa as president of South Africa’s ruling African National Congress (ANC) – with a razor-thin 51% majority of nearly 4,800 delegates – displaced but did not resolve a fight between two bitterly-opposed factions. On the one hand are powerful elements friendly to so-called “White Monopoly Capital” (WMC), and on the other are outgoing ANC president Jacob Zuma’s allies led by Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, his ex-wife and former African Union chairperson. The latter faction includes corrupt state “tenderpreneur” syndicates, especially the notorious Gupta brothers, and is hence typically nicknamed “Zupta.” (Zuma is still scheduled to serve as the country’s president until general elections scheduled for mid-2019.)

South Africa’s currency rose rapidly in value after Ramaphosa won, for he is celebrated by big business and the mainstream media. But he has also gained endorsements – due to quirky local political alignments – from the South Africa Communist Party, ANC-aligned trade unions and most centrists and liberals who despise the Zuptas. With this base and some nominal prosecutions of corruption, Ramaphosa will likely relegitimize the fast-fading ANC in time for a 2019 electoral victory. However, given the narrowness of his win, he probably cannot engineer Zuma’s early departure as many hoped, in the way Zuma had ousted Thabo Mbeki nine months before his term was due to end in 2009.

Moreover, Ramaphosa’s much-anticipated attempt to clear Zupta muck from the corrupt stables of several parastatal organizations and government departments will fail. Too many ANC patronage systems have become cemented. And three other leaders elected at the congress are high-profile Zuptas with corruption-riddled reputations, including secretary-general Ace Magashule and his deputy Jessie Duarte, as well as ANC deputy president David Mabuza. A new slur, “Ramazupta,” may emerge as the epithet for the coming regime.

Ramaphosa was a heroic mineworker leader during the 1980s, a crafty ANC secretary general under Nelson Mandela during the early 1990s when he led negotiations on many crucial semi-democratic deals with the outgoing apartheid regime, the main drafter of the country’s liberal constitution in 1996, and then – after losing the deputy presidency job to Mbeki in 1994 – a black-empowerment billionaire thanks to joint ventures in mining, banking and food franchises McDonalds and CocaCola. He became ANC deputy president in 2012 and in government, became the national deputy to Zuma in 2014.

By the 2000s, Ramaphosa had earned a reputation for seeking profits at any cost. The worst incident was at the Lonmin platinum mines at Marikana, two hours’ drive northwest of Johannesburg. On August 15, 2012 Ramaphosa emailed a request to police – for which he weakly apologized only a few months ago – demanding “concomitant action” against “dastardly criminals,” against whom police should “act in a more pointed way.”

He was referring to 4,000 desperately underpaid miners who had been on a wildcat strike the prior week, during which six workers, two security guards and two policemen had died in skirmishes. Neither Lonmin officials nor Ramaphosa wanted to negotiate. The day after the revealing emails, as strikers peacefully departed the strike grounds for their homes in nearby shantytowns, 34 men were shot dead by police, and 78 wounded.

Ramaphosa’s role was especially unconscionable given his struggle history. In the Emmy Award-winning film Miners Shot Down (from minute 13’), director Rehad Desai reveals the class-loyalty U-turn. In 1987 in the midst of a legendary strike, Ramaphosa accused the “liberal bourgeoisie” of using “fascistic” methods. Thirty years later he had become the main local investor in Lonmin, and within five years was a “monster,” according to local activists, playing a familiar role described by the workers’ lawyer, Dali Mpofu:

At the heart of this was the toxic collusion between the SA Police Services and Lonmin at a direct level. At a much broader level it can be called a collusion between the State and capital… in the sordid history of the mining industry in this country. Part of that history included the collaboration of so-called tribal chiefs who were corrupt and were used by those oppressive governments to turn the self-sufficient black African farmers into slave labour workers. Today we have a situation where those chiefs have been replaced by so-called Black Economic Empowerment partners of these mines and carrying on that torch of collusion.

With Ramaphosa’s rise, Lonmin’s demise

As for Lonmin, its London and Johannesburg investors are now witnessing what seems to be the firm’s certain death. Born as the London and Rhodesian Mining and Land Company Limited in 1909, it languished through the 1950s but then became one of the world’s most degenerate corporations thanks to managing director Tiny Rowland’s corrupt deals across post-colonial Africa. By 1973 even British Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath labeled Lonrho “the unpleasant and unacceptable face of capitalism.”

One reason for its demise in a takeover last week was the backlash against the Marikana Massacre which empowered the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu), a breakaway from the ANC-aligned National Union of Mineworkers, once led by Ramaphosa. Amcu became sufficiently strong to wage a five-month strike in 2014.

The Massacre also humiliated a high-profile Lonmin booster, the World Bank. Its 2007-12 poster-child treatment of so-called “Strategic Community Investment” at Marikana attracted persistent complaints from a community group, Sikhala Sonke (“We cry together”). These grassroots feminists have rebuffed several bogus Bank “dispute resolution” efforts and their stinging legal critique was deemed valid by an internal Bank ombudsman earlier this month.

Lonmin is being purchased in a fire sale by a local South African company, Sibanye. But with 38% of Lonmin’s 33,000 jobs on Sibanye’s chopping bloc, protests are threatened by Amcu’s Joseph Mathunjwa: “We are prepared to join forces with communities around Lonmin to ensure that the interests of mineworkers’ mine-affected communities are defended. We want to warn the new owners and current shareholders that we will fight and not sit quietly as our members’ future is destroyed.”

Sibanye CEO Neil Froneman warned critics to cease attacking Lonmin for repeated violations of its state-mandated Social and Labour Plan: “Communities that are unhappy, the Department of Mineral Resources that is unhappy – need to stop and allow us to complete this so that in the longer-term we can do more.”

Another Lonmin critic is the Economic Freedom Fighters party, which won a large share of the platinum belt’s vote after an ANC disciplinary committee chaired by Ramaphosa expelled its Youth League leader Julius Malema. His main crime was demanding mining nationalization, consistent with the ANC’s 1955 Freedom Charter.

The Marikana Massacre was investigated by the 2012-15 Farlam Commission set up by Zuma, but the outcome was weak and biased. Judge Ian Farlam blamed maniacal police leadership, but also recorded socio-economic failures by Ramaphosa, who not only failed to build houses with the $100 million World Bank loan. He was also implicated in a Lonmin tax avoidance scandal via his Shanduka firm’s control of the Black Empowerment partner Incwala. According to Lonmin’s lawyer, “Incwala for very many years refused to agree to the new structure” to halt a $100 million outflow to the Bermuda tax haven justified as marketing expenses. As the Paradise Papers recently , Shanduka also retained Mauritius accounts for nefarious purposes and as chair of Africa’s largest cellphone operator, MTN, Ramaphosa suffered continent-wide criticism for illicit capital flight.

So under Ramaphosa’s leadership, we can expect an amping-up of the ANC’s lowest-common-denominator ideology, neoliberal-nationalism, with the worst tendencies of both the WMC and Zupta camps on display in the party’s leadership. Aside from a #FeesMustFall breakthrough when Zuma promoted free tertiary education last Saturday for obviously opportunistic reasons just as the ANC congress began, 2018 will begin with budgetary austerity and a Value Added Tax increase. Meanwhile ANC leaders will continue to talk left (so as to) walk right, with renewed preparedness for a state of emergency if socio-economic protests continue rising.

But amidst undisguised pro-Ramaphosa media bias (e.g. the popular Daily Maverick), even his corporate backers are genuinely nervous about Monday’s “poisoned chalice.” They are now realizing, “Markets got this one wrong – and were pricing in a Cyril slate victory,” failing to comprehend new dangers within the ruling party’s fusion of the WMC and Zupta factions.

Durable liberal-bourgeois concerns about the new leader are also expressed in ascerbic critiques of the “Grand Consensus“ “nothing man” by Business Day columnist Gareth van Onselen. I debated another liberal commentator, Richard Calland a few years ago, in which he was gung-ho pro-Ramaphosa for all the wrong reasons.

Neither the ANC nor Lonmin are going to exit their respective crises in the immediate future. The notion of “crisis” has always implied both destruction and opportunity. Mining tycoons and political elites have generally (except in 2015) avoided the former and are now grabbing the latter.

As for the labor, feminist, community and student activists sure to be frustrated by a Ramazupta regime, the takeaway message is the same threat internet-based satirist “Cyrilina Ramaposer” concluded with, in her haunting Makarena on Marikana: “This shit ain’t over.”

The short life and times of Mamadou Saliou

Image credit Ndeye Seck.

Image credit Ndeye Seck.I am a teacher of English at a high school in the Sedhiou Region of Southern Senegal. In June 2016, a colleague informed me that Mamadou Saliou, one of our students had died in Libya on the way to Europe. Mamadou Saliou was only 23 years old.

I remembered Mamadou. In 2014, I had taught him in his first year of high school, known in Senegal as the fifth form scientific or “S” stream. In the S stream, mathematics, physics and natural sciences are the major disciplines. However, Mamadou Saliou had a genuine interest in English classes. And I appreciated his wit and strong character. As I learned his tragic fate, I remembered an incident from 2015 involving Mamadou. I was teaching in another class, fifth form literary stream, when Abdoulaye, one of the students proposed we commemorate Bob Marley’s death. As I agreed he hanged a banner, with Bob Marley’s picture stamped on it, on the front side of our classroom. Abdoulaye also sang “One Love” from the repertoire of Marley’s “Legend” album. His performance, his harsh, loud voice and the noise from the class drew the attention of a few students who were in the school yard. From that group, Mamadou Saliou confidently walked up to the classroom door, and with a bare smile, gave a thumb up to the performer before heading back outside.

The reason Mamadou Saliou decided to make the trip is obvious: the possibility of a better life. Mamadou tragically met death instead. I don’t know the circumstances under which he died. Was he alone, bereft when he died? Surrounded by strangers? Did he think of those he left behind? Had he been buried decently? These questions have been tormenting me since then, with no answers. I am sure though that Mamadou is one of the appalling numbers of young people who have died on their way to a better future. The International Organization for Migration estimates that 2,410 migrants died in the Mediterranean in 2017. But how many are unreported?

Over and over again, images of wrecking ships crowded with stranded figures, hungry for life and possibility come to my mind. These images, online, on TV and in newspapers, are so regular that we forget the tragedy they display. We condone the dehumanization of these so-called migrants, forgetting that they are people with motives, loves, hopes, and sorrows. In mid-November, the news coverage of slaves’ auctions in Libya sparked outrage in the whole world. Many people took to social media to denounce and express solidarity to the victims. Some African presidents expressed their concern and indignation. Alassane Ouattara, president of Cote d’Ivoire in an interview with a French radio condemned the slave auctions, insisting on how “choking, unacceptable and despicable” they were. Niger’s Mahamadou Issoufou called for action, “to attack the deep causes of this tragedy.” President Akufo Ado of Ghana declared that “the slave auctions were not only gross and scandalous abuses of human rights, but mockeries of the alleged solidarity of African Nations in the AU.” Mamadou’s own president, Macky Sall, made well-intended declarations and heartfelt condemnations. But as columnist Hamidou Anne wrote in French newspaper Le Monde: “Citizens can be outraged, as for political leaders, they have an obligation to act.”

The deplorable situation of these young Africans is another failure of our states, one too many. It further emphasizes the fatal ineptitude of our political leaders. Over the years, governments have taken over after one another and have shown their incompetence to implement relevant development policies. Poor school systems, unemployment and inefficient health services are prevailing in many sub-Saharan countries. Alongside political instability, they give way to persistent violations of human rights. Youth unemployment is pervasive and many young men and women have no faith in a better future in their home country. They go to school, or work, with no purpose nor perspective.

In many parts of Senegal for example, more often than not, populations feel isolated and abandoned by their administration. For those who can still find a way out, going abroad is the only solution to help their parents who are struggling to make ends meet.

Ends never seem to meet. Senegal is ranked 162nd in the Human Development Index report. The Senegalese National Statistics and Demography Agency (ANSD) estimated in 2015 that 56.5% of the population is subjectively poor and nearly 45% face food insecurity. In terms of health, there is one physician for 12,373 people and only 31 hospitals are available for more than 15 million people. Also, according to a report on the state of education in Senegal, published on the Ministry of National Education’s website, school dropouts accounted for 11.5% of the student population in 2015.

These rates hardly tell the dire living conditions of a majority of the population, the degradation of the health system and the deplorable situation of many schools. Three weeks ago, the Ministry of Education shared the positive results of important investments in the construction of classrooms. The Minister declared that the number of “provisory shelters” (basically huts passed off as classrooms) decreased from 8,822 in 2011 to 6,369 in 2016. Despite a literacy rate of 55.7% (UNDP estimates), the inadequacy between work supply and professional training make it difficult for the majority of young people to find a formal job. With nearly 8 million people under 65, the stakes are high for the government in terms of social policy, demographic dividend and employment policing.

That being said, the situation of the migrants is also a crisis of our citizenry. We, the people, have set the conditions for this chaos. We elect those incapable public officials that never make it a priority to give young people reasons to stay in their countries. We observe as bystanders as they loot and thieve our resources, while our youth leave and die in the Sahara and the Mediterranean. In Senegal, we have let our school systems degrade to a complete wreck. Every day, our youth witness the degradation of decent work, moral standards and values that make a citizen and forge a nation. They have no reason whatsoever to believe that hard work at home pays off, that they can go through a thousand frustrations and privations but that at the end of the day, their honest, decent job will ensure that they “provide for their families” and settle down. We don’t show them that they can stay and long for better living conditions, that they deserve better living conditions here.

That’s why they will leave, through the desert, on tiny canoes, by any possible means at the risk of enslavement, sexual exploitation and death.

December 18, 2017

The New Testament

Sandile Mantsoe is awaiting trial for the murder of his girlfriend Karabo Mokoena. Her family and friends tell harrowing tales of how he abused her over the course of their seven-month long relationship. He stands accused of escalating the abuse to its most gruesome conclusion, murdering her in his Sandton home and then burning and dumping her body in an obscure location.

In the mean-time, more than 120 individuals have come forward with allegations that Mantsoe defrauded them of thousands of rands through his currency trading company, Trillion Dollar Legacy.

Mantsoe’s pastor struggles to believe the allegations. He describes the twenty-seven year old as a young man poised to become “one of the stars this country (South Africa) has ever produced.” Mantsoe, as the pastor elaborates in a television interview, is “a great evangelist” who is warm hearted and humble.

On social media, South Africans take umbrage with the pastor’s soft description of the accused. They point out the pastor’s cognitive dissonance in the face of mounting evidence of Mantsoe’s darker side.

Not much information is publicly available about Mantsoe but the little that is shows him steeped in a culture we have come to venerate as young South Africans. It is a culture that celebrates constant self-invention. It is built on the gospel of entrepreneurship. It aspires to the casual intellectualism of the Ted Talk genius and the easy generosity of the mega philanthropist.

If you are brave enough to crawl down the Youtube rabbit hole, you soon realize that Mantsoe is part of a cohort of young men who achieve celebrity as guests on South African television programs and radio talk shows, where they are celebrated with titles that say much about our collective aspirations. The uncritical use of titles such as “Youngest Self-Made Millionaire” and “Most Celebrated Forex Trader” in media descriptions of these twenty-somethings belie a desperation for firsts and an even deeper yearning for those firsts to be in industries where black South Africans have historically been excluded.

Mantsoe plays right into these anxieties. He styles himself “The Moses of financial freedom,” leading his subscribers to liberation if only they believed in the power of the financial markets. For Mantsoe, financial markets are the next frontier and “black people are destined to be in this promised land.”

Sometimes he appears in the casual lecturing posture of the Ted Talk genius; his message a mixture of self-help and basic financial literacy. He titles one video “Trade Psychology” which he explains as “a mind to success approach to investment.” He encourages viewers to become “students of success”, to reorient their lives for success by changing any part of their lifestyle that does not reflect their new alignment.

At other times Mantsoe is a philanthropist. He adopts a style of giving one could describe as Oprah-ish in its performance. Very aware of its potential as a branding opportunity, it relies on big gestures, on making those who participate feel they are part of a movement.

As crafty as the role-playing sounds, Mantsoe and his fellow South African Forex salesman are not its originators. Theirs is an iteration of a culture that emphasizes financial success as the ultimate evidence of self-actualization. Only financial success gives a man the power to invent himself and only the man who has made himself has the fluidity of identity to tame the volatility of the modern economy.

I find traces of this reasoning beyond South Africa.

In his lectures and seminars, self-proclaimed “people’s scholar” Dr. Boyce Watkins entreats his African American audiences to “leave the corporate plantation” and seek freedom in entrepreneurship and investment in the financial markets.

Watkins owns many platforms, including the Black Business School, an online venture that offers a dizzying array of content. From financial investing information to tailor made curricula for homeschooling African American kids. He encourages self-education over formal higher education.

Watkins is part of a cohort of black public figures who preach the gospel of black financial liberation in Youtube seminars, books, DVDs and lecture tours across the country. Some of these men, including Watkins have visited or given ‘lecture tours’ in South Africa.

They see themselves as the vanguard of a “black capitalism” that prioritizes economic participation over civil rights as the definitive mark of fulfilled citizenship. They articulate the possibilities for achieving this status in language that draws together an entire spectrum of African American and black nationalist ideologies; from Pan Africanism to Afrocentriciy to Black Power.

This is an instrumentalist Ted Talk style of reading history to lend an ideational edge to a sales pitch. South Africa’s self-declared “rock star of public speaking” Vusi Thembekwayo has a similarly uncanny ability to condense history into useful lessons for financial success.

In a recent talk, Thembekwayo does what I can only describe as spectacular. He claims that the US attains the status of world’s largest economy because of a single historical event; the invention of the combustion engine. From there Thembekwayo makes this most mind-blowing statement which I must quote in full:

If you want to understand why Africa remains at the periphery of global economics you must ask yourself a single question; how many technologies has Africa produced and brought to the world that have shifted how the world and its global institutions work? Until that question is answered in the affirmative, we will continue to remain at the periphery of global economics.

It is not important to consider chattel slavery, that other shameful technology that fueled US success. Nor is it necessary to factor in generations of African exploitation. History is useful only as far as it lends legitimacy to a lesson that could be imparted in many other ways.

In another talk, Thembekwayo compares his own grandfather to Stellenbosch businessman Christo Weise and finds that the difference between the two men is a matter of mindset. Weiss “thinks big” enough to create Shoprite while Thembekwayo’s grandfather is a traditionalist whose “small business thinking” keeps him from growing his spaza shop beyond his zone of the township.

You could debunk his ahistorical account until you are blue in the face but you would still have to contend with the reality that Thembekwayo, with his huge following in business and among aspirant entrepreneurs, embodies what John Patrick Leary identifies as “the TED-talk-derived genius cult, in which wealthy audiences receive open-collared men pacing on bare stages as oracular sages telling hard and universal truths.”

Silicon Valley mogul Ben Horrowitz has been similarly criticized for misusing disciplines like anthropology and history to make claims about Silicon Valley’s innovative personality. Witness this Startup Grind Global lecture where Horrowitz extracts digestible nuggets, jam packed with lessons for success in the modern economy, from a loose and fast reading of the 1791 Haitian slave revolt:

If this guy [Touissant Louverture] could overcome being a slave for forty years and change the slave culture and defeat the French and the British and free the slaves of Haiti sixty-five years before the end of slavery in the United States, then you can change the culture in your company and make it great.

The lesson is that knowledge is malleable, it can say anything you want.

Some of Mantsoe’s peers have caught on and they have begun to make the slippery transition – mixing up God and the market to create their own brand of church where congregants believe in the transformative power of crypto-currency. Forex trader Louis Jr Tshoakene and Malawian evangelical pastor Shepherd Bushiri seem to have discovered a sweet spot. The prophet’s book Make Millions in Forex Trading: A simple guide to making millions through trading, likely ghost written by Tshoakene, is advertised on Tshakoane’s platforms, giving him access to the prophet’s multitudinous cross-continental congregants.

His own performance would straddle multiple roles but like all good evangelists, Mantsoe would have known that what matters most to believers is the manifestation of success. Not the rumors that he was in heavy debt nor reports that Trillion Dollar Legacy was a precariously tilted pyramid scheme. So long as he did not heave under the weight of his solo performance, Mantsoe could continue to manifest his destiny. This is the source of his pastor’s cognitive dissonance.

Beyond Mantsoe, the conventions, conferences and leadership seminars that proliferate in young professionals’ calendars suggest that the culture keeps finding corners to settle as South Africa’s young black professionals search for experts who will deliver the secret to self-reinvention for those who would brave the quest for self-mastery in an economy that was never built for their kind.

Remy Martin capture the spirit of the moment in their global campaign slogan: “You only get one life, live them.”

December 17, 2017

The Return of Muammar Gaddafi

Gaddafi at the 12th African Union Summit in 2009. Image credit U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jesse B. Awalt.

Gaddafi at the 12th African Union Summit in 2009. Image credit U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jesse B. Awalt.One of the unintended consequences of the angry reactions to the slave auctions in Libya, is a renewed romanticization of the supposed pan-African legacy of the late Libyan dictator, Muammar Gaddafi. At its heart, it reflects a depressing understanding of African politics which rules that a fair dictator is better than a chaotic political void.

Gaddafi ruled Libya for more than forty years since the military coup in 1969. His regime maintained a bureaucratic-authoritarian rule that criminalized political participation and dissent, legitimized a continual stability mainly through a corrupt redistribution of oil revenues in the forms of free healthcare and free education, and a pervasive cult of personality. Post-Gaddafi, Libya now has two rival parliaments and three governments. The dissolution of his autocratic rule after the 2011 uprisings has led to a state of social, financial, and political lawlessness.

The last few weeks’ outrage over the racist images of black Africans being sold in Tripoli, was accompanied by a strong criticism against the illegitimate military intervention in 2011 that led to the overthrowing of Gaddafi’s regime. These observers “questioned the role the Obama administration played in the Northern African country’s instability six years after the president ordered an intervention there.” The result was lawlessness and political violence. After the CNN’s slavery report was published, a widely-shared old tweet by Donald Trump, which dates back to 2011, was shared. It echoed the same sentiment: “As bad as Qaddafi was — what comes next in Libya will be worse — just watch.”

The argument goes that if Gaddafi was still in power, none of this would happen. Reactions on social media remythologize the legacy of the ex-dictator, “The Falcon of Africa.” A tweet insists, “whatever faults Gaddafi had, blacks were treated as equals in Libya than in most Arab countries. Another one summarizes, “Under Gaddafi, Libya had the highest life expectancy in Africa. Now, thanks to Western military intervention, Libya is one of the most dangerous nations in the world. A haven for modern slavery.” Numerous posts reflected on Libya’s progress under his regime in terms human and infrastructure development while other highlighted his positive pan-Africanism.

But Gaddafi was never a fair dictator, if the oxymoron exists.

In Libya, he was a bloody and delusional despot who committed massacres against his own people and used public resources to entertain his own cult of Jamahiriya, what Gaddafi and his supporters eventually called the regime. They murdered and tortured countless innocent civilians and journalists, financed numerous assassinations against political rivals in Libya and abroad. Gaddafi let the country’s infrastructure deteriorate while continuing to lavishly pay for his personal and political interests and that of his clan. He treacherously labelled his political opponents as a threat to the nation. As he told a group of American academics in 2006: “In the Middle East, the opposition is quite different than the opposition in advanced countries. In our countries, the opposition takes the form of explosions, assassinations, killings.” For decades, he treated the country’s wealth as his own and allowed his sons to steal vast sums of money from the country oil reserves, especially after the UN sanctions against Libya were lifted in 2003. He ruled through fear and caused Libyans to grow politically naïve.

This romanticization of African dictators reveals a problematic, yet popular, political intellectualization in Africa we thought was already expunged from our conversations: An internalization of neocolonial imaginary that only fair dictators can rule nations replete with issue of ethnic division and political rivalries. To echo the Cameroonian social theorist, Achille Mbembe’s argument: the neocolonial subjects “have internalized the authoritarian epistemology to the point where they reproduce it themselves.” For me, the neocolonial remythologization of the dictators becomes possible because the mind, and no longer the body, is now “the principal locale of the idioms and fantasies used in depicting power.”

But the African Union’s handling of the 2011 revolution, the military intervention, and the recent news of Tripoli’s slaves auction complicates this understanding. The AU’s solidarity with Gaddafi and his regime have always shaped the relationship between them. For many African leaders, the late Libyan leader was a popular figure. No less than Nelson Mandela is often quoted as saying: “Those who feel we should have no relations with Gaddafi, have no morals. Those who feel irritated by our friendship with President Gaddafi can go jump in the pool.”

This sense of friendship was built on Gaddafi’s $5 billion infrastructure fund and the AU’s overlooking of his political abuses. Before his pan-Africanism stunt and his “United States of Africa,” he complotted to overthrow numerous regimes. These included an attempted invasion of Chad in 1980, support for Idi Amin’s regime, and providing financial and military support to rebel groups in Liberia and Sierra Leone. That former South African President, Thabo Mbeki, famously clashed with Gaddafi, while his then-successor, Jacob Zuma, enjoyed better relations with him epitomizes the kind of solidarities the former Libyan dictator had with other problematic African leaders.

This is not a case of “all your favorites are problematic,” or of irrational reactions to the shocking and racist footage about the slave auction, but rather reflects a pervasive view of Gaddafi as, what Rene Girard calls, a sacrificial victim. It is interesting that Mbembe, without citing Girard, observes that what we have in the postcolony is a case of “theophagy” where “the god himself is devoured by his worshippers.”

The act of worshipping itself thrives. One of Gaddafi’s two sons, Saif al-Islam, is rumored to make a political comeback in Libya. The Guardian reports that Saif al-Islam could do well in elections scheduled for next year. This is the same Saif al-Islam, who during the 2011 uprising against his father’s regime, appeared in a notorious TV broadcast and declared, “There will be civil war in Libya… We will kill one another in the streets… All of Libya will be destroyed.” This is despite an ongoing indictment from the International Criminal Court (ICC) for alleged crimes against humanity.

December 15, 2017

Weekend Music Break No.113 — Nigerien band Anewal’s US Debut

This weekend’s Music Break will be a chance to do a deep dive on one band’s music. This past month Nigerien band Anewal made their U.S. Debut at Rockwood Music Hall in New York (organized by the World Music Institute). AIAC contributor Jacqueline Traoré conducted an interview with bandleader Alhousseini Anivolla and gives us her review of the show below. Happy weekend and enjoy the sounds!

Image credit Zach Isaac.

Image credit Zach Isaac.The Nigerien band Anewal’s sound is rooted in the Tamasheq musical tradition of ishumar. The term, a play on the French word chômeur (unemployed), characterizes a genre of songs and poems born out of the Tuaregs mass exodus to cities in southern Algeria, Mali, Niger in the 1960s and 70s. There they found limited job opportunities, and music became both a way to lament the loss of their way of life and to inflame nationalist passions.

Tinariwen, a band from Mali, was among the first to popularize the genre abroad. Describing themselves as militant musicians, the Malian band was upfront about its willingness to pick up arms to defend the creation of a Tamasheq state (which, if ever realized, would take up 60 percent of Mali). Much like their vocal neighbors, Anewal sings of a utopic and simple nomadic way of life, but unlike them, they stray away from divisive politics preferring instead to preach a message of harmony and brotherhood.

Anewal made its U.S. debut early this month at the Rockwood Music Hall in a concert organized by the World Music Institute. The trio, led by frontman, Alhousseini Anivolla, stepped on stage in bright three piece bazins, their faces wrapped in turbans, transporting the predominantly white audience straight to the Sahara desert. I suspect not many faces were familiar with the band’s repertoire — but its mesh of percussions and guitars (both electric and acoustic), charmed the crowd who awkwardly flailed their limbs and thumped their feet to the rhythm. Anivolla, pleased and perhaps overwhelmed, by their response, made a point to thank them after each song: first in English, then in Tamasheq and lastly in French.

ANEWAL-Osas It´s time by ANEWAL

In their first song of the night, Anewal sang of truth, urging us all to speak with honesty and integrity to the sound of an acoustic guitar and tinde drums. As the set progressed, the musicians picked up the pace and Anivolla traded his acoustic guitar for an electric one, scolding in his lyrics those who are easily swayed into conflict.

I met Anivolla, the band’s lead singer, at the cafe of the Edison hotel, a couple of hours before the concert and he struck me as a man of few words. Sipping on mint tea, dreadlocks hanging past the middle of his back, he explained that he picked up music early, first singing and playing the musical bow, and later on as he discovered Ali Farka Touré and Jimi Hendrix, the guitar. The name Anewal, which means wanderer, was a tribute to his grandfather and a wink to his nomadic heritage. “As soon as you forget where you’re from, you forget who you are,” he told me.

Image credit Zach Isaac.

Image credit Zach Isaac.Anivolla is convinced that much of the world’s problems lay in governments wish to police humans. Migrants drowning at sea, slave markets in Libya, all created because of lack of free movement. “If we made it easier for people to move, they would take a flight let’s say to Paris or London, spend the night, a day, realize how life is, and they would come back home,” he said. He’s been living in Berlin for the past five years and misses Niger every day. While living in Europe, he’s refused to change the way he presents himself. “I’ve been in Europe for eight years now, but I still dress like this,” he said pointing to his white cotton tunic “Why should I wear a suit and tie? I keep the way I look because it shows who I am.”

The band played for two hours when from the sidelines the manager signaled them that they were running out of time. They abruptly finished their last song, Anivolla put down his guitar and thanked the audience one last time. Thank you, Tannamert, Merci.

December 13, 2017

How not to talk about corruption in South Africa

On Tuesday, 5 December, global retail group, Steinhoff International, headquartered in South Africa, announced the resignation of its CEO, Markus Jooste. A white South African, Jooste, resigned in connection with a German accounting fraud investigation, involving significant overstatements on revenue and assets. One asset manager noted of Steinhoff that it was “as close to a corporate-structured ponzi scheme as one can get.”

What followed has been heralded as one of South Africa’s biggest ever corporate scandals; its largest corporate collapse. Steinhoff is registered in the Netherlands, its primary listing is on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange in Germany and its secondary listing on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange in South Africa.

Within three days of Jooste’s resignation, Steinhoff was downgraded by Moody’s to junk status. Its stock declined in value by 88 percent, causing contagion across the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, undermining South Africa’s economy in the process, devaluing millions of pensions, as well as threatening the jobs of 105,000 employees worldwide. South Africans are rightly appalled. As the Daily Maverick columnist Richard Poplak tweeted: “The rage streaming toward Steinhoff (and friends) has everything to do with the fact that corporate South Africa has long positioned itself as the antidote to corrupt government. The racial implications should be obvious. The bankruptcy (pun intended) of this notion even more so.”

The issues raised in the Steinhoff collapse deserve dedicated treatment. My interest though is less with Steinhoff than with South Africa’s debate about Steinhoff. Certain features of this debate illuminate the problem with South Africa’s general corruption debate.

The Steinhoff scandal has been occasioned by comparison with South Africa’s state capture crisis, the latter involving President Jacob Zuma’s outsourcing of key state decisions to unaccountable and often unknown fora outside the state – most prominently involving the infamous Guptas, an Indian immigrant family close to Zuma. While no one doubts how corrupt the Zuma faction of the ANC has become or the role of the Guptas, the way the debate has developed in South African media and in anti-corruption campaigns reinforces, or fails to adequately address, racialized and ahistorical accounts of corruption as a problem specific to black people.

White South Africans bear original responsibility for poisoning this debate. Not surprisingly, they have tied it into ancient, racist themes about black people’s abilities to govern.

In post-apartheid South Africa, whites have additionally pursued related elaborations around white status anxieties about black upward mobility. In particular, white South Africans have used claims as to corruption to reinforce racism-tainted values of merit, public interest, impartiality and legality. The response from more egalitarian tendencies — in the ruling ANC, the unions, the student movement and more broadly — has been to point towards the still largely white-controlled corporations, their role in corrupting the state, and the latter’s own internal corruption. This is a credible response, but this now decades-old exchange has come to have certain limitations.

Consider, initially, the now common statement that white-controlled corporates marched, or helped foment marches, against state capture in its own interests, but also, racistly, has no interest in dealing with white corporate corruption. The first part of this statement is trite, and incomplete. If South Africans are hoping for capital to act against its interests, they’ll be disappointed. And in any case the majority of the marchers were black, with many (in the unions for instance) opposed to the corporates and moving on their own initiative. The second part of the statement is false.

Legal rules construct markets. Those around accounting fraud, at issue here, do so by ensuring the processes of verification which generate the trust that lubricates, rendering more profitable, all market exchanges. The agents of capitalism, although undoubtedly often racist, have committed immense efforts over centuries to establishing an infrastructure to ensure this trust in exchange, bringing into being whole professions; standard processes, checked and balanced; internal and external financial and other forms of accounting and auditing; financial forensics; corporate and professional codes of conduct; tribunals; specialized regulatory agencies, enforcement agencies, courts, these often with effectively transnational jurisdiction.

The market itself is allergic to a breach of trust. When Steinhoff did so, within three days it lost almost R200 billion. Its chairperson, Christo Wiese, at the same time lost 87% of his wealth. (Incidentally, Wiese “tried to board a flight from England to Luxembourg in 2009 with two checked suitcases and one carry-on bag stuffed with a combined £674,920 — just over $1 million — in bills.”) In cleansing the system, Jooste and others have resigned. Investigations in South Africa, Germany and the Netherlands are proceeding unhindered. Jail time is a prospect. As such, people denouncing the Steinhoff executive, calling for accountability, are simply promoting the legal rules established at the behest of white capitalists, to serve the general interests of their capitalism.

Universal convergence on this point, almost entirely unnoticed, is remarkable. Everyone pursues a singular cause, marching divided so to speak, but striking united. On 9 December the Zuma-aligned Progressive Professionals Forum opened a docket of inquiry for criminal charges against responsible persons. A day earlier the pro-market Democratic Alliance had written to Dutch, South African and German authorities asking for investigations to be extended to Steinhoff’s auditor, Deloitte. On that same day, the independent, socialist union federation, SAFTU (the breakaway from the ANC-aligned COSATU), had released a statement also urging wider investigations, suggesting that the collapse was evidence of a “structurally corrupt capitalist system.” A day before this, when questioned by a centrist commentator to the effect that “South African business, big established capital, is corrupt,” the CEO of Business Leadership South Africa (the peak association of broadly white corporates — the CEO is black) responded that “it is absolutely corrupt to the core,” continuing that the association would be taking steps against its members.

It is a relatively happy alignment on an immediate, shared problem, but one unfortunately much less likely to happen when it comes to that public trust, that final guarantor of all anti-corruption, that common vehicle of socially-beneficial ends: the state. The problem here is that white South Africans set, or are allowed to set, or are imagined to set, the entire agenda. White hypocrisy is declared in not physically marching against Steinhoff. In Steinhoff’s reflection, in a narrative that finds traction at various points especially across South Africa’s left, the whole movement against state capture gets reduced to white people. Any black involvement in that movement is only, completely, a cover for white-racist tendencies.

After 23 years of post-apartheid social evolution, this discourse is clearly not intended as a serious appraisal of the current situation. Anyone who has observed state capture marches on the ground, who has paid some attention to the networks behind the scenes, who has any insight as to the wider implications of what the Zumaists are doing, would know that the situation is complex enough to make a simplistic and essentializing application of racial categories outrageous. Instead of engaging with this complexity, and while omitting to develop a more sophisticated approach on this great matter of state, many instead rest on cheap rhetorical points which have the effect of rendering other black people invisible; denying their interests, their thoughts, and their agency; excluding their contribution from legitimate participation in the body politic; reducing them to white racists for pursuing their own, quite legitimate, interests.

The discourse in question has no regard, even, for the black working class and poor for whom it often claims to speak. It elides entirely the decade-old opposition to corruption, and more recently state capture, displayed from certain quarters of the union federation COSATU and its off-shoots. It ignores the interests and expressions of the poor, many presently pressed under the boot of the ANC patronage machine. These often decry the corruption of the ward councillor, his political favoritism in the allocation of jobs, contracts, and houses; his use of these resources to co-opt insurgent popular leadership and divide incipient movements; even the assassination of popular leaders who resist incorporation. The poor generally have a better understanding of the lines up to President Zuma’s project, much better than anyone in South Africa’s myopic, middle class debate. As one member of a poor people’s movement was inclined to say, and I regrettably paraphrase: “We know that white monopoly capital is the big devil, but we need to get through Zuma to get to them.”

By centering white people, this improvident discourse marginalizes everyone but white people. To all outward appearances, barring the Zumaists themselves, no group that expresses such centering has ever defined its own interests in relation to state capture, none has attempted to accrue a broader role in societal leadership, to embark on the detailed tactical-institutional analysis needed to craft the response in accordance with own wider objectives. They have all simply ceded this ground to opponents in the moderate wing of the ANC, the Democratic Alliance, and elsewhere. On Steinhoff, these groups unthinkingly unite behind white capital, in restoring conditions of capitalist profitability, innocent of an interest in shifting broader institutions in their favor. On state capture, these divide the left internally, foregoing opportunities to leverage crisis toward shaping a more effective state: one more inclined to drive transformative public policy, one more accountable to the interests of the black working class and poor.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers