Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 260

February 6, 2018

Paul Kagame and Benjamin Netanyahu are enablers of each other’s worst behavior

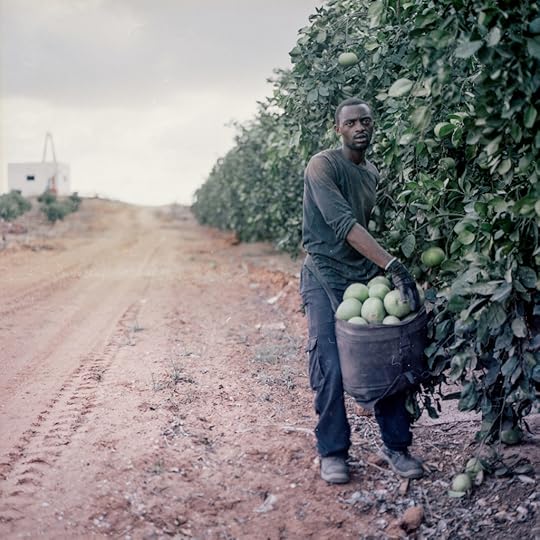

Sudanese migrant worker in Israel. Image credit @Amira_A on Flickr.

Sudanese migrant worker in Israel. Image credit @Amira_A on Flickr.On Sunday, Israel’s immigration authorities announced it had started issuing migrants letters advising them they had 60 days in which to “voluntarily” leave the country. Since many of them — Sudanese and Eritreans especially — can’t return to their countries of origin for fear of being tortured or death, it is unclear where they’ll go. One place that keeps coming up as a destination is the central African country of Rwanda.

The bilateral relationship between Rwanda and Israel has long been framed in terms of their shared experiences of genocide. At a ceremony in Rwanda’s capital, Kigali, to mark the International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust at the beginning of this month, a representative for the Rwandan government expressed that Rwanda and Israel are “united by a common vision to fight anti-Semitism, genocide ideologies and all forms of genocide denial, as we know the terrible consequences of these issues if they are not addressed.”

In the light of this profound common perspective, recent initiatives undertaken jointly by the governments of Rwanda and Israel seem particularly awkward — including reports that Rwanda would take African immigrants and refugees the Israelis refer to as “infiltrators” — if not disturbing.

Late last month, Israel supported a contentious Rwanda-led initiative “rewriting the historical narrative” of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda to declare it a genocide of the Tutsi only, sparking accusations of genocide revisionism. Thousands of Hutus and others were also murdered by Hutu fanatics. Making things worse, Israel’s support for the resolution was reportedly motivated by its desire to deport tens of thousands of African asylum seekers to Rwanda — a cruel and racist program that is opposed by a growing number of mainstream Jewish organizations around the world.

Genocide revisionism?

On January 26, 2018, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution to revise the international day of memorial to replace references to the “Genocide in Rwanda” with the “Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda.” By narrowing the language to specify the Tutsi as the targets of the genocide, the move has been interpreted as “downplaying” the deaths of Hutus and others who had been killed for refusing to join in the massacres.

This is a move long desired by Rwandan President Paul Kagame and groups like Ibuka, which represents Tutsi survivors. Rwandan Ambassador to the United Nations, Valentine Rugwabiza, told the General Assembly that the purpose of the resolution was to “correct inaccuracies” by clarifying the target of the genocide, and to fight against “Genocide denial and revisionism” — in particular against those who promote “double genocide” theories claiming that Tutsi and Hutu are equally responsible for the atrocities.

Israel the resolution, describing it as nothing more than a “proper representation of facts.” It was the only “Western” country to be a co-sponsor, but was joined by more than thirty African countries, among them South Africa, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Kenya. This support surprised the European Union, the US and Canada, who expressed deep reservations; the US argued that the new wording “does not fully capture the magnitude of the genocide and of the violence committed against other groups.” US officials had reached out to Israel months earlier for its help in persuading Rwanda to withdraw the resolution, and were shocked when Israel refused.

Netanyahu’s decision to take the side of Kagame over US President Donald Trump has raised eyebrows in Israel — especially as the vote happened in the midst of the furor over Poland’s own controversial Holocaust bill, a proposed law criminalizing accusations of Polish complicity in the mass killing of Jews in Europe during World War II. As an Israeli official told journalist Barak Ravid, “[one] line connects the Kagame revisionism about the Genocide and the Polish revisionism about the Holocaust. It is sad we are cooperating with Kagame on this.” Israeli Labour Party Chairman Avi Gabbay also criticized the resolution, accusing Netanyahu of “imitating” the Polish government’s own rewriting of history.

Deportation deal or no deal

Israel’s willingness to collude in an initiative widely seen as genocide revisionism is even more disturbing in light of admissions from officials. One of the reasons that Israel co-sponsored the resolution was as a favor in return for its “deportation deal” with Rwanda, which has agreed to accept the African asylum seekers that Israel is trying to expel.

This year Israel has dramatically intensified its long-running program which aims to deport over 34,000 Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers, who have been given three months to leave the country or face a choice of either “indefinite detention” or deportation to an undisclosed “third-party” country. In the current stage of the deportation program, Israel has begun to hand out deportation slips to men without children, who consist of between 15,000 and 20,000 of the total who are “liable for deportation.”

Netanyahu’s government has not specified the third-party countries where the deportees will be sent, but it is widely known that they include Rwanda. In November, Rwandan Foreign Affairs Minister Louise Mushikiwabo said they were prepared to accept 10,000 asylum seekers “if they are willing to come,” and media reports confirmed that Israel will pay the Rwandan government $5,000 for every asylum seeker it accepts. However, Rwandan Deputy Foreign Minister Olivier Nduhungirehe has denied the existence of an explicit deal, calling reports to the contrary “fake news,” and has insisted that Rwanda will only accept people who come voluntarily, “without any form of constraint,” and only if consistent with international law.

Rwanda’s assurances have done little to assuage the fear and anger that has been building over the impending deportations. In January, Eritrean asylum seekers held a mock “slave auction” outside of the Knesset, arguing that deportees will likely end up in Libyan slave markets. At least 4,000 asylum seekers have already been “voluntarily” deported to Rwanda from Israel between December 2013 and June 2017, and recently released testimonies present a grim warning, with stories of theft, being denied the status to work in Rwanda, and being trafficked to Uganda. “You want to die?”, one testimonial warns current asylum seekers, “then go back [to Africa]. If you don’t want to die, stay in Israel [in prison].”

Letters given to asylum seekers in Holot detention centre have tried to counter these claims by praising Rwanda, saying “the country to which you go is a country that has developed tremendously in the last decade and absorbs thousands of returning residents and immigrants from various African countries.” Netanyahu and also summarily dismissed any warnings, suggesting that Rwanda would be a good destination for refugees because “there are 180,000 refugees sitting there under the protection of the UN, so the claims that it is dangerous are a joke.” Echoing far-right conspiracy theories, Netanyahu has also claimed that the growing protests against the deportations are funded by Jewish billionaire George Soros.

The deportation plan comes after years of outright racist anti-refugee campaigning from senior Israeli politicians and religious leaders, who refer to the asylum seeker as “infiltrators.” In one notable incident in 2012, member of parliament Miri Regev (now culture minister) told an anti-refugee demonstration in Tel Aviv that African migrants were “a cancer in the body” of Israel, a sentiment which polls suggest is shared by 52% of Jewish Israelis.

Israel’s Friend in Africa

Israel’s support for Rwanda’s UNGA resolution should also be understood in the context of Israel’s “scramble for Africa,” as Netanyahu works to strengthen its poor diplomatic relations on continent. Kagame is one of Israel’s closest African allies; he has visited Israel twice in the last two years, has a consistently pro-Israel voting record at the UN, and has asserted that “Rwanda is, without question, a friend of Israel.” For his part, Netanyahu was the first Israeli Prime Minister to ever visit Rwanda, and in November 2017 he announced that Israel will be opening an embassy in the country.

Kagame has also been expanding his ties with the wider pro-Israel community. During his visit to the United States in 2017, Kagame was the first African leader to address AIPAC, and he received an award for his pro-Israel record, presented by far-right Rabbi Shmuley Boteach. Kagame has a personal relationship with Boteach, who has defended Kagame against allegations of human rights abuses.

As Kagame takes up his post as the new Chairperson for the African Union (AU), Netanyahu will be looking to secure observer status for Israel, as efforts to date have been stymied due to opposition from other African states. A Kagame-led AU may indeed open up stronger relations with both Israel and Trump; when the AU expressed “deep concern” over Trump’s declaration of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, Rwanda was one of 35 countries to abstain from a vote that would have nullified the declaration. In the aftermath of Trump’s “shithole countries” remark, a spokesperson said the AU was “frankly alarmed;” meanwhile, Kagame tweeted about his “very good bilateral meeting” with Trump at Davos.

In the end, Kagame and Netanyahu are enablers of each other’s worst behavior. Netanyahu’s support for Kagame’s motion is certainly questionable, as it at least gives the appearance of crass genocide revisionism, but ultimately it is Kagame’s collusion with Israel in its mass deportation scheme — a scheme which plainly deploys a rhetoric of ethnic cleansing — which will forever mark their legacy of rogue internationalism.

February 5, 2018

The making of a film empire

Image from Akintunde Akinleye’s “Inside Nollywood” series, via Flickr.

Image from Akintunde Akinleye’s “Inside Nollywood” series, via Flickr.Short introductions are all the rage in scholarly publishing these days, and it’s easy to see why. Relatively inexpensive and readable in a single sitting, these downsized monographs, which can easily fit in a coat pocket, purport to provide brief overviews of broad subjects. They’re certainly teachable — attractive to students for their cost and concision — but they can prove maddening to those who know their subjects especially well, and who may crave more nuance than a mere 30,000 words will allow. There are other potential pitfalls, of course. For instance, a single factual or typesetting error can spell disaster for an author unable to refine or reiterate claims in so limited a space.

Recently published by Rutgers University Press, Valérie K. Orlando’s New African Cinema — part of Rutgers’ “Quick Takes” series on film and popular culture — evinces such pitfalls: the name of the great Senegalese director Safi Faye is misspelled on multiple pages; one important date is off by a century; and Orlando offers the troubling suggestion that “homosexuality” is a form of violence. New African Cinema is otherwise rich and rewarding, but the errors loom disproportionately large in a work of its length.

Fortunately, Emily Witt’s pocket-sized Nollywood: The Making of a Film Empire, just published by Columbia Global Reports, is almost entirely free of factual errors, offering a detailed yet snappy introduction to an industry that is exceedingly difficult to condense for any readership, let alone one with no previous knowledge of African screen media. Witt, who has written for GQ and The New York Times, takes a journalistic approach to Nollywood without falling back on the bombast of most popular accounts, which tend to exoticize the industry almost beyond recognition, expressing a distinctly Western wonder at the activities of the undifferentiated African masses. In this short book, chapters contextualizing Nollywood as a popular art and commercial industry alternate with effective plot summaries of key films (including Amaka Igwe’s classic melodrama Violated, from 1996, and Daniel Oriahi’s more recent Taxi Driver: Oko Ashewo, from 2015). Witt, who researched the book in Nigeria, also provides firsthand accounts of various activities, from micro-budget filmmaking in Asaba to a splashy, star-studded movie premiere at The Palms, a mall in Lekki. Her wry humor occasionally comes through, but it never seems condescending or otherwise disrespectful. One senses that the author genuinely admires the artists and entrepreneurs with whom she spent time, and this reader, at least, can attest to the accuracy of her warm, evocative character portraits.

Witt gets into some trouble, however, when quoting industry insiders, some of whom make misleading statements that are allowed to stand uncorrected in the text. For instance, the famed producer and marketer Gabriel Okoye (also known as Gabosky) is quoted (via a Nigerian magazine interview) as saying that he released Lancelot Oduwa Imasuen’s Invasion 1937 — a film whose title is actually Invasion 1897, and that was first released not in 2016 (as Gabosky has it) but two years earlier. At one point, Witt speaks to a crew member whose claim — that he was put out of work when, in 2006, the Lagos state government outlawed billboards — the author unquestioningly reproduces, failing to mention that, at that time, the government merely attempted to crack down on illegal signage.

One of the most pleasurably eccentric aspects of Witt’s book is that its prologue is outsourced to the brilliant Femi Odugbemi, a documentary filmmaker, television producer, screenwriter, photographer, cinematographer, and emergent historian of Nigerian media. Odugbemi provides a compelling account of Nollywood’s development — a colorful précis of Witt’s own passages. This outsourcing has its drawbacks, however: for all his acumen, Odugbemi manages to perpetuate the binary opposition between colonial film units and “African cinema,” suggesting that the former were unpopular when, in fact, they were anything but. In the 1950s, Adamu Halilu and other Nigerian directors made immensely successful, widely seen educational films that featured more Black faces than spectators were likely to see in the American, Asian, and European films that, at the time, were the bread and butter of the commercial theaters. Documentaries produced under the “modernizing” auspices of colonial powers have influenced a variety of cultural forms that flourish in contemporary Nigeria, including television soap operas and Nollywood films. As Brian Larkin argues in his remarkable book Signal and Noise, colonial media “fed into postcolonial visual culture and cannot be so neatly separated off.”

Witt certainly isn’t immune to offering questionable assertions of her own. Ossie Davis’ historical epic Kongi’s Harvest (1970), for instance, is hardly a “classic,” as she calls it. Shot entirely on location in Nigeria, this Nigerian-American-Swedish co-production, with its all-Black cast, was boycotted by Lebanese theater owners, who feared its capacity to cultivate a popular appetite for African cinema, and who, at the time, enjoyed a virtual monopoly on exhibition in Nigeria, aided as they were by powerful Hollywood studios. More to the point, Kongi’s Harvest, with its rather tame, allegorical take on Nigerian political troubles, was poorly received by those who managed to see it in boxing halls, classrooms, and other nontheatrical spaces; Soyinka disowned it, and prominent academics denounced its American authorship.

Finally, I disagree with Witt’s decision use the term “Nollywood” to include Hausa-language productions from northern Nigeria, whose popular label — “Kannywood” — indexes a certain estrangement from Nollywood, rather than, as Witt has it, an allegiance to this distinctly southern Nigerian industry. But one of the pleasures of studying Nigerian media is that there is always much room for debate, and there is by no means a firm consensus on how to draw Nollywood’s cultural, geographical, and linguistic boundaries — nor, perhaps, will there ever be. My reservations about certain aspects of Witt’s book thus amount to little more than quibbles. This is an excellent, engaging introduction to an industry that deserves continued attention.

February 4, 2018

Postcards from Rwanda

All images credit Sara Terry.

All images credit Sara Terry.The translator wouldn’t ask the question.

We were sitting in the community meeting space of a “reconciliation village” near Rweru, along the southern border of Rwanda with Burundi. We’d been talking with five villagers, three Tutsi who had survived the genocide and two Hutu who had been perpetrators – and who had also been their neighbors before the 1994 killings.

I’d been in a few other reconciliation villages – all founded by Prison Fellowship Rwanda, a religious non-profit which began working in Rwanda’s prisons over a decade ago to convince genocidaires to ask for forgiveness once they were released, and to counsel them in the Bible’s teachings about it. PFR has built six villages for Hutus and Tutsis who are willing to live together again, and to work in co-ops for the benefit of the community. They hope to build a total of 15 to 20 in the next few years as more genocidaires come out of prison.

The five villagers appeared relaxed and comfortable with each other, the Tutsi women even throwing their arms around the Hutu men with an easy affection when they posed to take a picture. Forgiveness took a lot of time, and work, explained one of the women, who lost almost all 48 members of her family during the genocide. But in the end, she said, “You forgive to separate yourself from the hatred.”

After we’d talked for a while, I wanted to move the conversation in a different direction. I wanted to ask about the tens of thousands of Hutu civilians who’d been killed by the armed forces of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel group of mostly Tutsi refugees, which had stopped the genocide – and whose leader, Paul Kagame, has been president of the country since 2000, and its de facto leader since 1994.

I carefully posed the question to my translator, who works for Prison Fellowship Rwanda, which is closely aligned to the government: “Was real reconciliation possible in Rwanda if there was no punishment for the killings of Hutus, no acknowledgment of their deaths?”

He shook his head. No. He would not ask the question. “It’s political,” he said.

“It’s above their level.”

*****

It’s become one of the grimmest facts of late 20th century history: more than half a million Rwandans – mostly Tutsis and some moderate Hutus — lost their lives in just over a hundred days in 1994, while the world failed to intervene. The genocide was perpetrated by extremist Hutus, fed on a generation or more of propaganda that portrayed Tutsis as the enemy, as “cockroaches” that needed to be exterminated. Using whatever weapons were at hand – guns, knives, machetes, clubs, hoes – perpetrators killed as many as 800,000 of their countrymen, their neighbors, their relatives, their colleagues. It was an unthinkable mayhem that still frames the political, social and cultural landscape of the country today.

I didn’t come to Rwanda until the fall of 2015, some 21 years after the genocide and nearly a decade after I’d begun working on this project. It was a deliberate choice to make this the last chapter of this work. Rwanda holds different lessons than the other places I’ve been. It holds warnings, too.

I’d followed Rwanda closely, concerned by its state-mandated agenda of unity and reconciliation — a top-down, carefully-managed narrative aimed at constructing a new Rwanda, with only one ethnicity, “Rwandan.” In the other post-conflict places I’d worked on this project, including Sierra Leone and northern Uganda, I’d explored grassroots cultural efforts, community-driven work. Those endeavors seemed more genuine to me than Rwanda’s carefully-crafted national experiment, which has drawn on cultural sensibilities about truth-telling and forgiveness, but packaged them in a political mandate.

But then the scale of the killings in Rwanda was exponentially worse than the other places I’d been: An international criminal court, which closed in December 2015, after more than two decades of work at a cost of $2 billion, indicted 93 individuals; while the “gacaca” courts based on a local justice system, and called into action by Kagame, dealt with some two million cases over ten years in a flawed legal process that has drawn much criticism, from all sides.

From the beginning, a new narrative was being woven – a necessity, in so many ways, for a country that had ripped itself apart as viciously as Rwanda had. But it was being created by an elite group, led by Kagame, who also had much to gain by visioning a new story for Rwanda. Over the past twenty years, as the new version of Rwanda has been cemented, there has been a vast simplification of pre-genocide history, which now claims that Hutus and Tutsis always lived in peace until the colonial powers came; there has been the creation of a unified tale of the genocide itself, with clearly defined roles of Tutsis/moderate Hutus as victims and of all other Hutus as complicit or as perpetrators; and there has been a virtual silencing of any other version of Rwanda’s past or present through a government that has grown increasingly authoritarian, controlling the press and effectively eliminating political opposition.

*****

I’ve called this chapter of the overall project “Postcards from Rwanda,” because during the month I was there, I found what many colleagues who know the country well had warned me of to be true: it’s almost impossible to have a meaningful discussion with Rwandans about anything that counters the new narrative.

For one thing, it’s illegal to use the designations “Hutu” or “Tutsi”; for another, to question the official version of the genocide – to ask anything about the massacre of tens of thousands of Hutus by RPF forces after the genocide was officially over – is to invite criminal charges of genocide denial or revisionism. Over and over again – in the reconciliation villages I visited, in shops, taxis, in tourist locations, at genocide sites – people offered almost identical observations, “Oh, we lived in peace before the colonial powers came. We were one,”; “The previous government taught us bad propaganda, they caused the violence”: “Thanks to this government, we are able to live in peace again.”

In fact, Hutus and Tutsis had a long and complicated relationship before the colonial powers came. The two groups had evolved over time – Hutus were cultivators, agrarians, making up by far the majority of the population, about 85 percent. The minority group, which tended cattle, were pastoralists known as Tutsis, who over time they became the ruling elite. Physical characteristics tended to mark each group – Hutus were shorter, with broad noses, and Tutsis were taller and thinner. But occasional intermarriage (which continued in the twentieth century) blurred those lines. And the distinctions were blurred even further by the fact that a Hutu who acquired cattle could become a Tutsi, while a Tutsi who lost his cattle also lost his status, becoming a Hutu.

The Germans, and then the Belgians, certainly made all of this worse when they showed up – creating rigid ethnic lines and deciding among other things that Tutsis, who had more “Caucasian” features than Hutus were the more intelligent group, favoring them highly within the colonialist power structure. But Westerners didn’t invent the distinctions between Hutus and Tutsis, or the tensions between them – tensions which extremist Hutus took to unthinkable extremes during the genocide.

You wouldn’t know that in post-genocide Rwanda. Colonial powers caused all the problems. Before they showed up, everything was fine. Period.

The new narrative is enshrined at Rwanda’s single most identifying public spaces — the official memorial sites scattered around the country, where guides repeat the same truisms. Before the colonial powers came, there were no problems. There are no Hutus, no Tutsis, we are all Rwandans.

It’s a reductionist story that’s further simplified by the very design of the memorials – bones are placed in mass graves, with no attempt made to identify and individualize the remains (in fact, individual bodies which have been exhumed at massacre sites are not kept intact; remains are mixed together when they are brought to memorial sites). The scale is overwhelming, a monolithic horror – and the displays of exposed bones and stacked skulls are so raw that many survivors’ families have objected, asking for the bones to be buried.

Yet at each of the sites I visited, there was also a carefully orchestrated acknowledgment of one or two individual stories, settings of single coffins or graves marked with specific text about how the person was killed. One victim speaks for the thousands of victims who lie in adjoining mass graves. It’s a vivid punctuation point in a structured narrative that rests on a bipolar unity – one group of victims, one group of perpetrators. “They” (Hutus) did that to “them” (Tutsis).

The government is intentional in the story it’s creating with these memorials, in the public space that it’s curating and controlling for remembering the genocide. The aim is to have every victim of the genocide, or as many as can be recovered, buried at one of the sites. I ask a guide about families whose loved ones may have been killed near their homes – whose remains are easily located and identified. What if that family has already buried the victim and prefers to keep a private grave on their own property, or in their village, as a way of mourning and caring for their relative?

“Well, it’s possible,” the guide says. “But someone from the government will visit them and talk to them about the memorials. Once they are sensitized, they usually see that it’s the right thing to bring the remains here.”

*****

I made my driver uncomfortable more than a few times during the two or three weeks he took me around Kigali and beyond, pressing as delicately as possible on some of his rote answers. The day he told me, “We had a government who told us bad things, now we have a good government,” I pushed gently, asking what would happen if a bad government came back in power? Would he believe what that government said? Several Rwandans I’d met had said Oh, no, never again (“never again,” not surprisingly, is a core theme the government’s platform of unity and reconciliation), yet my driver startled me when he replied, “Well, that is the problem. We are African. We don’t like to think for ourselves. How can we change that?”

The danger, the warning bells, of a society with a unified narrative that allows for no other voices in the public space, is that people aren’t encouraged to think for themselves. In fact, it’s actually discouraged, or criminalized – or it can cost you your life (several opposition politicians forced to leave Rwanda have been murdered abroad in recent years). This doesn’t mean, of course, that there aren’t Rwandans firmly committed to building a just society, that there aren’t deep and genuine acts of reconciliation to be found, and of friendships preserved across ethnic lines. It’s just that the suppression of truth – of someone else’s narrative – makes for a shaky foundation for nation building.

Unfortunately, the West has been complicit from the beginning in allowing Kagame to create this highly selective version of Rwanda’s national identity. In October 1994, a team of UNHCR investigators filed a report claiming that the RPF had committed genocide on the civilian Hutu population, killing an estimated five to ten thousand people a month between April and August of that year. The Gersony Report, as it’s known, was buried, apparently under orders from the highest levels of the UN, and with the agreement of the US. For years, officials denied the report’s existence, until it was leaked to the press in 2010. But the damage had been done – Kagame and the RPF were never held accountable by the international community for the killings.

The first chapter in an official new narrative had begun, one that continues to the present. “It’s political,” as my translator said that day when I tried to raise the question with the villagers who’d told me about their own reconciliation. “It’s above their level.”

International donors and Kagame’s friends – including Bill Clinton and Tony Blair – were far more impressed by the rapid strides Rwanda has made under Kagame’s leadership. The country stabilized quickly and is celebrated in many circles abroad, particularly among Christian groups, as a model of reconciliation; economic growth has clocked in at around six percent a year (made possible in part by foreign aid which has accounted for 30 to 40 percent of the country’s annual budget); red tape and mid- and low-level corruption have been virtually eliminated, making Rwanda a magnet for investment; Rwandans are now guaranteed nine years of free, compulsory education; the country has the highest percentage of women parliamentarians in the world (68 percent); litter has been reduced (Kagame banned plastic bags nation-wide); and Kigali is a relatively safe, clean capital (helped in part by laws that make it illegal, for example, to run out of gas).

But twenty-one years after the genocide, after the RPF came to power, Kagame’s tightly-woven narrative is showing signs of fraying. Criticisms long made by human rights activists – about the regime’s human rights record, about repression of the media and political opposition – are starting to be echoed by others. Kagame has drawn sharp criticism from the UN for Rwanda’s role in two decades of unrest in neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo – a conflict that has taken an estimated five million lives. And his goal of turning agrarian Rwanda into a middle income society by 2020 is falling short: an estimated 85 percent of the country remains in poverty, living on $1.50 a day.

*****

So much is hidden in plain sight. So much of the past – the past that no one talks about openly – is there for the seeing. A Rwandan colleague, a fellow photographer, who now lives in the US, returned for the first time in years not long ago to visit family. He has thought of the genocide as a visual atrocity – in which people were often singled out for death based solely on their looks, on whether they had the physical traits associated with Tutsis.

He was startled to find that despite the national refrain of “We are all Rwandan,” the visual landscape – billboards, entertainment, advertising – was actually dominated by a specific physical type: the tall, slender, straight-nosed look of Tutsis. Watching the Miss Rwanda pageant in 2014, he was shocked to learn there was a height requirement for contestants. To enter, they had to be at least 1.63 cm (nearly 5’7”) tall, a restriction that all but virtually eliminated Hutu women, who are generally shorter, from the contest.

He says he needs to concentrate on the good things that are happening in Rwanda, on the committed relationships he sees between Hutus and Tutsis. It’s what gives him hope. But he remains uneasy about the future of his country. “The shadows,” he says, “are hiding lots of violence.”

Shadows. Lessons. Warnings. It’s hard to read between the lines of Kagame’s post-genocide narrative, with any surety of where that script will lead. But every time I think about the fact that it’s illegal to use the words Hutu and Tutsi in Rwanda, I can’t help thinking of my first long-term, post-conflict project, in Bosnia and Hercegovina, once part of Tito’s Yugoslavia.

When World War II came to an end, Marshall Josip Broz Tito, the Communist leader of Yugoslavia’s Partisan forces during World War II, created a second Yugoslavia, a socialist federation of six nations whose peoples were Croat, Serb and Bosniak (Catholic, Orthodox and Muslim) – and who had been on different sides of the conflict. Tito outlawed the use of those names, declaring “Unity and Brotherhood” as the guiding principle for all Yugoslavians.

It was an authoritarian regime. Tito was named president for life in 1953, although he was widely seen as a “benevolent dictator.” But his death in 1980 triggered tensions that had always been just beneath the surface – leading to the Balkan Wars of the 1990s, fueled by the nationalist identities Tito had tried to stamp out. In 1995, near the end of the war in Bosnia (and just one year after the bloodletting in Rwanda), Serb forces murdered some 8,000 Muslim men and boys in what has been called the worst genocide in Europe since World War II.

At the end of 2015, Kagame announced that he would seek a third, seven-year term in the 2017 elections – to the very vocal dismay of many in the West, including the US, who see the move as undermining Rwanda’s development as a democracy. Although Rwanda’s post-genocide constitution specifically limited the presidency to two terms in office, rumors began circulating months earlier that Kagame wanted a third term in office. The RPF-controlled Parliament had approved an initiative allowing that change, which went to a national referendum vote in early December, in which 98.3 percent of voters agreed to amend the constitution.

The change also allows the possibility of two additional five-year terms, which means that Kagame could continue to rule – continue to write Rwanda’s narrative – until 2034, forty years after the genocide.

* “Postcards from Rwanda” is from Sara Terry’s long-term project, Forgiveness and Conflict: Lessons from Africa.

February 3, 2018

Africando in Colombia

El Caribeño, new school Pico, Barranquila. Image credit Jim C. Nedd.

El Caribeño, new school Pico, Barranquila. Image credit Jim C. Nedd.This month’s INTL BLK episode takes a deep dive into the African-influenced music scene of the Colombian Caribbean coast, co-presented by Palmwine.it in celebration of their Guarapo! album. Before that we run through some of the latest tunes from the contemporary Afropop landscape with stops in Nigeria and Kenya, as well as take a stop in Brazil to celebrate Carnival. Last but not least, RIP Hugh Masekela.

February 2, 2018

AC Milan’s Moroccan problem

Former AC Milan star George Weah’s inauguration as President of Liberia represents a positive association for the club. Weah played there when he won his FIFA Player of the Year award in 1995. The same can’t be said for its involvement in Morocco, where the Italian football club is helping to normalize a decades-long occupation.

In early December 2017, AC Milan announced that “passion for football and for AC Milan has now reached the sand dunes of the Sahara desert” with the launch of a new football academy. According to a club press release, the academy is based in the city of “Laayoune, in Morocco.” But the statement from the club makes no mention of the fact that Laayoune is actually the largest city in Western Sahara, a territory that has been occupied by Morocco for decades.

Previously a Spanish colony, the majority of Western Sahara has been controlled by Morocco since a bitter war with the Polisario Front, the resistance movement of the indigenous Saharawi population, ended in a 1991 ceasefire. Saharawi control the rest of the territory in the form of the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). With the support of powerful allies such as France and the United States, Morocco has been able to successfully ignore a 1975 International Court of Justice (ICJ) opinion that denied its claim to sovereignty over the territory and prevent the holding of a long-promised referendum on self-determination. The issue attracts little international attention, and the move by AC Milan is another sign of how the status quo has become increasingly entrenched.

By opening an academy in Laayoune, and explicitly referring to it as part of Morocco, AC Milan is helping to whitewash the Moroccan occupation. The press release notes that the project was “strongly welcomed” by Laayoune’s mayor Hamdi Ould Errachid, ostensibly due to its contribution to his goal of encouraging participation in sports, particularly football. But more importantly, this is a propaganda victory for Morocco, which will no doubt be delighted at having one of world’s most well-known football clubs set up an academy in the city, lending an air of legitimacy and normality to the occupation.

AC Milan is not alone, among footballers or institutions, in legitimizing Morocco’s occupation. Diego Maradona, arguably the greatest footballer ever, is among a group of former stars that have been willing apologists for the occupation. Maradona and others including Egypt’s Mohamed Aboutrika (who has publicly called out Israel’s occupation of Palestinian land), Brazil’s Rivaldo, Ghana’s Abedi Pele, and Liberia’s Weah took part in a gala match in Laayoune in late 2016 (as well a similar match in 2015) to mark the anniversary of the so-called “Green March,” in which hundreds of thousands of Moroccans crossed into Western Sahara in 1975. The event, an occasion to celebrate for Moroccans, is for the Saharawi a painful reminder of the invasion and partial occupation of their homeland, which led to forced exile for many and the ongoing stalemate in the struggle for control of the territory.

Mohamed Mayara, a Saharawi journalist and human rights activist based in the occupied territories, expressed frustration at the move by AC Milan and the wording of its press release, noting that it contradicts international law regarding the status of Western Sahara. In addition to the ICJ opinion, Mayara also highlighted the 2002 opinion of Hans Corell, the United Nations Legal Counsel, reiterating the status of Western Sahara as a non-self-governing territory requiring self-determination, and the European Court of Justice ruling in 2016 that Western Sahara is not part of Morocco.

The launch of the academy also comes in the wake of Morocco’s decision to join the contest to host the 2026 FIFA World Cup, where it will be competing against the joint bid of Canada, Mexico, and the United States. The high-profile bid, and indeed hosting the tournament itself should Morocco be successful, offers a significant opportunity for Morocco to polish its international image. But attracting the world’s attention could also make Morocco vulnerable, providing Saharawi activists and their international supporters with the chance to highlight Moroccan human rights abuses and the ongoing denial of the Saharawi people’s right to self-determination.

Under the three-year agreement with the city of Laayoune, the AC Milan academy will provide youth from “Laayoune and…the surrounding cities” the opportunity to train with experienced coaches. Having an academy run by such a successful football club will no doubt be highly beneficial to young footballers in the area. According to Mayara, around 90 percent of the players at the academy are Moroccan, while the rest are Saharawi. Although Saharawis in Laayoune are not prevented from joining, it is impossible for Saharawis living in the SADR-controlled part of Western Sahara to do so due to the Moroccan-constructed wall that divides the territory. Furthermore, the participation of individual Saharawi in the academy does nothing to change its broader significance as a win for Morocco in the struggle for control of Western Sahara.

AC Milan could simply have opened an academy somewhere in Morocco’s internationally recognized sovereign territory. Instead it has let itself become a willing part of Morocco’s propaganda machine.

The club did not respond to a request for comment.

February 1, 2018

How did Fulani herdsmen become such bogeymen in Nigeria?

Fulani cow. Moor Plantation, Ibadan. Image credit Dr. Mary Gillham via Dr. Mary Gillham Archive Project on Flickr.

Fulani cow. Moor Plantation, Ibadan. Image credit Dr. Mary Gillham via Dr. Mary Gillham Archive Project on Flickr.In the last few months, alleged attacks on innocent civilians by herdsmen across Nigeria have been on the rise. These attacks have preoccupied commentators from across the political and religious spectrum in Nigeria. Many of these pundits have ascribed the preponderance of these attacks to a particular ethnic group noted for their pastoral life: Fulanis.

The Fulanis are a majority Muslim ethnic group whose life are heavily dependent on animal pastures. As a result, some of these pundits have ossified around the discourse of an attempt by the Fulanis to reproduce the Usman Fodio Jihad of 1804, with the intent of spreading Islam across the country. The fact that current President Muhammadu Buhari is a Fulani Muslim also adds to this speculation about the Fulanis planning to take over Nigeria. To buttress the point about a planned “Islamization” of Nigeria by these Fulani pastoralists, many of these pundits, especially those on social media often circulate pictures of herder’s wielding AK-47s while tending to their pasture. Many of these widely circulated pictures of alleged AK-47 wielding herders have been discredited as either photoshopped fakes or simply images found randomly on the Internet. More importantly, some Christian leaders such as Bishop Oyedepo of Winners Chapel recently claimed to have received a letter from herders where the herders wrote “God had given them the land.” Oyedepo’s claim of receiving a letter from herders who want to Islamize Nigeria has been proven to be false.

However, what is missing in this conversation is the question as to why and how a pastoralist community suddenly becomes a roving insurgency across the country. Several factors can be adduced for the incessant attacks on innocent farmers across the country.

Many of these factors are interrelated and intertwined. They include: the emergence of Boko Haram as a roving insurgency; the effects of climate change on herders; the spread of small arms across the Sahara Desert; and the growing ethnic and religious mistrust in Nigeria.

Before moving forward, it must be noted that many Nigerian communities always had lived in harmony with pastoralists. Many of us who grew up in rural Nigeria would remember the constant presence of Fulani herders in our community who were always welcomed with open arms. In the 1970s and 1980s many kids would welcome Fulani herders to town centers with the chant of “Baba Yaya,” signifying that the herders were the fathers of the cattle. Calling the herders Baba Yaya was not in anyway meant to discountenance the importance of fatherhood for the herders, but was in recognition of the love the herders had for their herds, as well as their kids who would also follow them around while herding cattle.

Why and how have the children of the Baba Yaya era, who are today’s pundits, suddenly become an advocate for the complete annihilation of Baba Yaya? What has changed? Unpacking these factors will help in deepening the conversation about these attacks particularly on farmers.

Recent reports indicate that the number of casualties associated with herdsmen violence is just behind that ascribed to Boko Haram in Nigeria. But there is a correlation between the dislodgement of Boko Haram from their most active sites in the Northeast and the rise in violence associated with the so-called herdsmen in many parts of Nigeria. While not disputing that there are attacks perpetrated by herdsmen, to put all attacks in one box will be tantamount to reductionism. It will be absolutely correct to assert that many of the attacks associated with herdsmen may actually be attacks carried out by remnants of Boko Haram dislodged from their most potent spaces. Thus, many of these dislodged Boko Haram militants have basically turned themselves into roving insurgents across the country. Additionally, the instability occasioned by the Boko Haram insurgency in the Northeast has also meant that many pastoralists would have had to relocate their cattle to a safer pasture.

The presence of an unusually large number of herders has resulted in a form of economic, religious and political anxiety in the South. Herders moving through areas in search for new pastures has led to large scale destruction of farmlands. This is happening in areas not used to seeing a large number of herds. So, lives and properties are destroyed, and there is greater distrust amongst the population.

The crisis is compounded by the associated problem of small arms floating within the West African corridor, particularly the Maghreb route. The preponderance of small arms in the region has also meant an increase in rebellions, especially in states such as Nigeria with a weak security apparatus. A weak security architecture, combined with social injustice, creates rebellions that are in most cases lacking in ideological clarity. The lack of clarity makes these rebels susceptible to sponsorship from different interests, whose ultimate intent could be destabilization of the state as a result of their displacement from governmental patronage networks.

The question then becomes, how are these insurgents with no clarity of purpose able to recruit members into their dysfunctional group? The answer to this question is not far-fetched. First, the effect of climate change on the rise of social inequality in many parts of the country has meant the increased susceptibility of socially vulnerable groups to recruitment. The Lake Chad basin that had for many years provided employment for many young adults in the region is drying up. Many whose livelihood depended on their ability to fish, graze or farm have had to contend with two obstacles — drying rivers as a result of climate change and insurgency by Boko Haram in the name of religion. In the absence of gainful employment, those who could not flee the insurgents are either forced into it or incentivized to join.

In this hysteria, elites in the South are pushing their states to abandon the project of animal husbandry as a large scale agricultural policy. Many governors elected, by not only indigenes of their states but all residents of the state, including Fulanis, now are awoken at night from nightmarish visions of invasion by cattle with sutured head like demons. The cattle have become the metaphor for an alleged Islamization of Southern Nigeria by those considered to be “alien” even if these same aliens are entitled to rights as Nigerians.

Many in our human rights community have abandoned the struggle for the rights of all citizens. Yesterday’s human rights activists have become today’s champions of ethno-nationalism in alliance with those they had previously despised as collaborators with military autocrats. But in idiotic shortsightedness, driven by the Southern elites bigotry to see Islamization where there is none, they are blinded to see the potentials that abound in terms of employment opportunities and fiduciary gains for the people if animal husbandry is commercialized in their states

The elite make it look as if the North has a God-given right to monopolize the animal husbandry industry. This is myopia at its worst affliction. Relying on the vituperative tantrums of religious merchants, media profiteers and ethnic irredentists, who are hell bent on causing division and ethnic hatred in furtherance of their own self serving agenda, is not the way to go. We owe a duty to ourselves to free the Nigerian state from this melancholy.

January 31, 2018

The Lame Duck President

Image credit Government of South Africa Flickr.

Image credit Government of South Africa Flickr.South Africa’s President, Jacob Zuma, is a lame duck. On December 18 2017, Cyril Ramaphosa, Zuma’s deputy, was elected president of the ruling African National Congress (ANC), placing him on a trajectory toward the state presidency. Zuma, clearly unable to threaten this eventuality, has lost support, as erstwhile allies jockey for position around his successor. Seizing the initiative, Ramaphosa has instead activated political and legal processes that will remove Zuma before the end of his term in mid-2019 and purge the more visible of his illicit networks from the state. This moment prompts reflection upon the Zuma presidency, and the prospects of Ramaphosa. It should however be recognized that though much is made of differences in personal qualities between these two figures, presidencies are defined by the possibilities of the broader political regimes that constitute them. And in this respect Ramaphosa, much like Zuma before him, finds himself in the unenviable position of presiding over a regime that is in crisis and terminal decline.

Political regimes involve obdurate commitments of ideology and interest. The ANC articulates an ongoing “national democratic revolution,” which posits black South Africans as the motive forces undoing the negative legacies of white colonialism, while establishing a liberal democratic society, reconciling through restitution with the country’s white minority.

The ideology is made material through redistribution. Policies of affirmative action and black economic empowerment augment the growth of black middle and business classes. Black workers are partners in a labor relations framework that extends significant rights to organize, bargain and strike; provides unions with an important voice in the negotiation of social and employment legislation; and ensures serviceable protections for individual employees. Social welfare and basic services are progressively extended to poorer black South Africans. Many feel, with considerable justification, that movement along all these lines has been too slow. Much of that is because the economic engine chosen to drive these advances, both enabling and severely constraining their possibilities, is contemporary capitalism, the state framing its parameters largely in accordance with the dictates of neoliberalism. Notably, in this context the ANC party machine, through politicized control over the regulatory and resource allocation powers of the state, distributed as patronage, offers an important channel of upward mobility, giving opportunities to many who are otherwise destined to suffer immense material deprivation in the prevailing political economy.

Over time, all such regimes lose programmatic vigor. Their limits are steadily revealed. Their grander promises are broken. Disappointments accumulate. Adjustments to conditions generate enduring political tensions and factionalism. All regimes cycle from ebullient emergence to despirited decline.

The ANC fought its 1994 election campaign on the prospect of a broadly social-democratic and developmentalist Reconstruction and Development Plan (known everywhere by its acronym. RDP). By 1996, then deputy president Thabo Mbeki (who was effectively the prime minister to President Mandela; running the country) imposed as non-negotiable the neoclassical orthodoxy of the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) program, which prioritized inflation targeting, financial and trade liberalization and fiscal austerity. Among other effects, this de-industrialized the economy and increased the official unemployment rate from 17% in 1995 to 27% in 2005. As Mbeki’s tenure proceeded, unity among the motive forces unraveled. His centralizing style excluded and alienated provincial and local patronage-brokers and powerful businesspersons. The ANC governed through a “Tripartite Alliance” with the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the union federation Cosatu. Mbeki’s neoliberalism invited fractures in the Alliance. Critics of GEAR in the SACP and Cosatu were denounced and often purged as the “ultra-left”. In the last five years of Mbeki’s ANC presidency, South African police recorded an average of 9,085 crowd incidents per year, perhaps half of these were protests, making around 12 protests a day against the government. In 2002, industrial action saw a low of 615,723 workdays lost, rising consistently, year-on-year, to 9,528,945 in 2007. Mbeki’s critics presented Zuma as the antidote and at the ANC’s Polokwane Conference of that year he handily defeated Mbeki. (Zuma’s deputy president for his first term was Kgalema Motlanthe, a former trade unionist; Ramaphosa – then still “deployed” by the ANC to corporate South Africa – only served as Zuma’s deputy during the latter’s second term.)

Put another way, Jacob Zuma rode to power upon a regime in crisis. His rise was at the time heralded as a pivotal rejection of Mbeki. No ideologue, Zuma was a compromise among the discontented, able to pose as a container for their divergent aspirations. Imbued with occult powers in South African political debate, he was labelled the game-master, the supreme tactician, able in arcane, rarely observed ways to leverage his position to dictate the course of political history. This characterization lingers, but Zuma’s whole incumbency bears the motif of a weak president, who notwithstanding his personal qualities, was structurally unable to marshal the formidable powers of the state presidency into significant departure from the regime that formed and ultimately contained him.

Regimes, even in crisis, are not easily discarded. Politicians who emerge from within them continue to display complex ties of affiliation to them. They continue to enact routines that reinforce their regime. They continue to see costs in discarding the still resilient commitments that have thus far ensured their own political prominence.

Zuma and his coalition, thus positioned, rejected Mbeki but failed to provide a comprehensive repudiation of Mbeki’s regime, nor the visionary formulation and legitimation of an alternative. Instead Zuma tried to reinvigorate the past by cultivating an aura of Mandelaism. He made a public show of reconciliation with Afrikaners and the white poor. He adopted the style of a unifier, a negotiator of compromise within his disparate coalition and beyond. Presidential patronage complemented this approach. Zuma’s administration was carved up into fiefdoms for powerful groups, periodically reshuffled in accordance with the vicissitudes of his favor, with otherwise limited direction and discipline rendering policy development and implementation uncoordinated and ineffective.

The keystone policy achievement of Zuma’s first term, the 2011 National Development Plan, is a 430-page tome that touches on every feature of the South African social landscape, projects to 2030, and is often inconsistent. Crucially, in economic policy it involved only tentative elaboration on Mbeki, reaffirming government’s commitment to such measures as financial liberalization and fiscal restraint, and reprising GEAR’s attempted reversal of labor’s post-1994 legislative gains. It remains to be systematically implemented.

Unions rejected it. Zwelinzima Vavi, then general secretary of Cosatu, noted that “This raft of policies generate déjà vu, it seems history is going to repeat itself.” Other reforms promised to unions, like an end to labor broking, were constrained by ANC-aligned business interests (one of Zuma’s own sons was identified as holding stakes in a labor broking firm). The resulting estrangement with Zuma first split the union movement. More Zuma-aligned elements in Cosatu had Vavi and its largest union, NUMSA, expelled. Zuma himself was always more tightly tethered to the business-oriented wing of his coalition. Such was the character, for instance, of his initial political base in Durban and the province of KwaZulu-Natal, where his network included people like Don Mkhwanazi, a controversial businessman and so-called godfather of black economic empowerment. As he lost the support of remaining unions, Zuma became isolated to such a base. Its leading figures, who like Zuma presently gained from and wished to expand the channels for upward mobility provided by the ANC party machine, prompted and framed Zuma’s second term radicalization, now a real attempt at departure from the post-Apartheid regime.

The major policy development of this turn was “radical economic transformation.” While always thin on details, this drew on 2012 ANC Conference Resolutions, where it emerged in awkward contradiction with the National Development Plan and was initially conceived as inclusive of the interests of the entire liberation movement. In 2014, when enshrined in government policy, Rob Davies, the left-leaning Minister of Trade and Industry, said it called for “radical transformation of production relations … characterised by more equitable benefit-sharing and by less inequality.” However, it increasingly emphasized more narrow concerns, particularly the promotion of black business. Illustratively, in state contracting, contrary to older National Treasury legal advice as to unconstitutionality, from April 2017 new legislation mandated set-asides, the reservation of tenders for black and other categories of disadvantaged business. Revealingly, this legislation included a new category, businesses “owned by black people living in rural or underdeveloped areas or townships”, providing legal basis for geographically-defined set-asides, giving some legal structure to a patronage system that has become intensely territorial at ward and broader levels.

Mostly this drive was not so structured. Zuma was permissive. Politicians and associated businesspersons were given relatively free reign outside of the disciplinary framework of legislation. This proceeded to a point that exposed severe financial and administrative limits to the expansion of the ANC party machine. For example, in a country facing the prospect of catastrophic water shortages, now most prominently in the Democratic Alliance (DA) run City of Cape Town, construction of a major dam in the Lesotho Highlands, intended to serve the country’s economic powerhouse of Gauteng, had its procurement process delayed for a year, as the responsible minister interfered in favor of a particular supplier. By early 2017, as the resulting scandal expanded, her Department of Water and Sanitation was reported to be “bankrupt”, R4.3 billion in the red, with senior state officials noting that “internal controls, project management and contract management have collapsed.” Reflective of a prevalent pattern, Zuma’s incumbency saw the amplification of critical pre-existing problems in basic education, public health, public transport, communications, land reform, and beyond into the whole fiscal situation of the state.

One Zuma acolyte, the powerful Minister of Mineral Resources, declared at a gathering of the Black Business Council that this sort of “radical economic transformation” justified and required that “We will take pain, business will take pain, and our people will take pain.” For now, there remains enough of a stake in the existing post-Apartheid regime for such a vision to be widely rejected. Over Zuma’s last years, a range of groups that rarely agree – established, traditionally-white business, a multi-racial cross-section of the middle class, nearly all the unions, the news media, opposition parties, many in the ANC – joined the chorus for his removal. By late 2017 this momentum was expressed in polls that suggested that Ramaphosa was massively favored over Zuma’s preferred successor, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma. Thirty-two percent of black voters suggested that a Dlamini-Zuma presidency would leave them less likely to vote for the ANC, leading ANC pollsters to note that this was a “repellent factor” unique in the history of the party, which had taken just 56% of the vote in the municipal elections of 2016, in the process losing control over the running of three large city councils, including Johannesburg and Pretoria.

Since his election as ANC President, Ramaphosa is said to have ridden, most evocatively, a “Rainbow Revolution,” inaugurating a society where “good governance, economic growth and anti-corruption may no longer be a pipe dream.” On these terms Ramaphosa has elicited a groundswell of goodwill from corporates and the middle class, even those historically outside the ANC. Tony Leon, former leader of the official opposition in Parliament, the DA, has acknowledged risks to other parties, stating that “Ramaphosa’s election has been a game changer,” then doubling down to the effect that “he should be supported 1000% when he’s right.” Certainly, constitutionalism has been strengthened, important standards as to presidential integrity have been set, and critical parts of the state may now be insulated. Ramaphosa has repudiated Zuma’s most ominous project, a multi-trillion rand nuclear construction plan, and gestured toward prosecution of Zuma himself. But this is not a revolution so much as a reassertion.

Ramaphosa has also recommitted to the National Development Plan, which he played a prominent role in drafting, and to South Africa’s 22-year-old “stable and predictable macro-economic framework.” Yet it is precisely within this framework that South Africa’s patronage politics gains a widely appreciated function. Ramaphosa’s faction in the ANC has itself always included powerful patronage-brokers and connected businesspersons. He seeks “unity” with Zuma’s erstwhile allies, no doubt cognizant of the fact that newly competitive elections leave him poorly positioned to cut the many patron-client threads that hold the ANC organization together, that fuel its electoral machine. Competitive elections also leave him with little space to alienate any other component of his coalition or the broader black majority. Fiscal and administrative crises constrain quick movement in any popular direction. And in 2012, Ramaphosa was implicated in the massacre that killed 34 mine workers at Marikana. In 2013/14 police recorded 13,575 crowd-related incidents. In 2015, students at the prestigious University of Cape Town led a wider youthful rejection of Mandelaism. The post-Apartheid regime is coming undone, but Ramaphosa seems more dependent upon it than ever.

January 30, 2018

How to subvert the Hollywood Western

Still from film Five Fingers for Marseilles

Still from film Five Fingers for MarseillesThe new film, Five Fingers for Marseilles revolves around the tale of five black men, spanning their childhoods (when they started a gang, the “Five Fingers”) and later adulthood. Their childhoods coincide with Apartheid, building up to a fateful skirmish with corrupt white policemen and then years later as some of them gets corrupted by a criminal syndicate — led by a one-eyed bandit named Ghost — who has hijacked their town. One of the original “five fingers,” Tau, who left town as a teenager following that confrontation with the police, returns to restore order. The film draws on the conventions of Hollywood Westerns as a genre. All the conventions of the western are here: a mysterious, flawed, hero; the code of the West; the cutout villains; the shootout, etcetera. But its setting in a small South African town means it is upfront about the country’s politics. Critics — whether bloggers, on social media, or mainstream critics — have been full of praise. Variety’s critic described it as “an impressively effective and engrossing cross-cultural hybrid.” The film, which has been featured at a number of festivals, including the Toronto International Film Festival, will premiere in South Africa on 7 March and go on general release in the country on 6 April. The film is scripted by Sean Drummond, who I have known for a number of years (full disclosure: he has also collaborated with another AIAC editor and film director, Dylan Valley, on films). Another South African, Michael Matthews, is director, and the film was produced by Asger Hussain and Yaron Schwartzman at Game 7 Films, along with Drummond and Matthews. We interviewed Drummond and Matthews about the film.

First, I really enjoy ed watching the film. It is a triumph. Congratulations to you, the director and the crew. The film has gotten a positive reaction all round from critics. Well deserved. Did you expect this reaction?

Thank you. I think we hoped for a strong positive reaction, but didn’t go in with any expectations. The responses both from international festival critics and audiences and the limited audiences who have seen it in South Africa have been incredible. After so many years pushing for the film – seven years by the time of shooting the film, eight by the time of the festival premieres and almost nine when it releases in April in South Africa – we had fallen in and out of love with it so many times but by the end were feeling really good about it and really proud on behalf of everyone who worked so hard on it. We may have thought there would be a level of engagement with a degree of distance – that it was at best “a South African Western, cool concept, cool film.” But we’ve been pleasantly surprised. Audiences everywhere have gotten so deep into the politics and the history and the language and the meanings of it, as well as the western-ness of it, which is just the best reaction we could have hoped for. The interviews and Q&As we’ve done have gone deep and it’s been amazing.

Can you talk about the economics of making a film like this. What does it take to produce a film like this in South Africa, with such high production values and an international profile? How long did it take to raise the funding for the film? W ho funded it? What did you learn from the process?

Well, as I said already, it took seven years. And it came together and fell apart twice during that period before finally coming together and sticking the third time. We had incredible partners early on in Asger Hussain and Yaron Schwartzman at Game 7 Films in New York, who saw the potential for a powerful and marketable film that was authentically South African, but could reach a world audience. We knew from the beginning that we’d do best to realize the film through an international network rather than in isolation in SA: One, filmmaking is a global business and too often I think South African film tends to think of itself in a bubble. Two, to reach international markets, you really need strong international networks, whether it be finance, sales, festivals or any aspect. And, three, budgets depend on sales estimates, and our balance between enough finance to make the film at the level we needed it to be and enough sales projections to justify that figure depended on world markets as well as the home market. Too often local films are produced cheaper than they should be, for local markets that don’t perform as well as hoped, so the next film is smaller, and the cycle sort of winds inwards. This was our first feature, and we obviously had big ambitions but to a degree we’re trying to break that mould. We’re in the sales process now and a release in South African cinemas – where we’re hoping to make a big impact – so we’re learning as we go whether our ideas work or not. We’ve learnt so much along the way, constantly. We’re lucky to work with great people to mentor and guide us.

We could write a book about financing the film. The long and winding road. We had a local investor who led us along and burned us very badly – twice. The first time, we actually had crew starting to work and were just weeks out of starting, before he dropped out on us. We had one of our US producers who had come out to South Africa and ready to get to work. We’ve had various financing partnerships come and go – some that ended in “well, we put up a good fight, but ultimately couldn’t make it happen together.” We explored a French co-production for almost a year before realizing it would be a financial step backwards for the project. We chased various funds in South Africa and around the world. In the end the bulk of finance came from two US-based sources: one who committed very early and stuck with the project for 6 years, and one that came in right at the very end and became one of our strongest pillars of support. We had support from the South African National Film and Video Foundation from very early and they stuck with the project for four years. We had a local partner come in with a gear and support commitment, which was invaluable, because they loved and believed in the project. The South African government Department of Trade and Industry rebate is a godsend for local filmmakers (which subsidizes a portion of the budget of local films or international co-productions), and they were a pleasure for us to work with. And we had many great people commit their time to the project for very low rates or in some cases even for free; I won’t name names, but there are very wonderful people in the South African industry who gave freely to us, some for years, and we’d give the world for in return.

In the end, I think we can safely say the production value far outweighs the actual budget we had to spend on the film, and is the product of the blood, sweat and tears of literally everyone who worked on the film, from the top billed cast to the amazing heads of departments, to the lowest of the crew. And of a town — Lady Grey in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa — that believed in us and in the project. Everyone came to the party, everyone loved it as much as Mike [the director] and I did, and we fought like hell to make it what it is.

The majority of the dialogue is in seSotho and siXhosa , two languages primarily spoken by black Sou th Africans. Are we right to assume the screenplay was written in English, translated into Sesotho and isiXhosa and then subtitled back into English? That’s seems like a fairly unusual, labor intensive creative process. Can you talk about it how it worked practically to make that happen? Can you also talk about the politics of language; that is the decision to have the characters (with the exception of a white salesman, a Chinese shopkeeper and a white policemen) speak in African languages?

The film is predominantly Sesotho, with some English, Afrikaans and then a very little Xhosa. And even in the Sotho spoken, there are different dialects: from a more colloquial small town style that most of the characters speak with occasional words and phrases from other languages thrown in, to a rich, deep old Sotho that feels almost like an equivalent of Shakespearean English, that the Sepoko (Ghost) character speaks. The area we filmed in sits on the border between the Eastern Cape in South Africa and Lesotho, so it’s a true to life cultural and language mix, and we wanted to reflect that in the film. It’s reflected in character names too. As we got closer to production, Sotho became the dominant language – we really fell in love with the poetry and lyricism of it – and we made the decision to weight the film that way.

The script was written in English, and then we worked with a Sotho writer, Mamokuena Makhema, to take the dialogue and translate it in a way that’s both true to the language and to the poetry and intention of the lines, rather than as a literal word-for-word translation, where meaning never really comes across. We went over every line in English and then over the meaning of the Sotho versions, until they were where we all wanted them to be. Then we broke down every character’s lines and gave them to them in English and Sotho and gave them the chance to tweak as they felt appropriate. Some actors, like Hamilton Dhlamini who plays Ghost, went deep-deep and you can tell, even in his delivery, that there’s symbolism and metaphor laced into everything he says, even beyond the original script. Sotho speakers who’ve seen the film have really picked up on the nuance and appreciated it – I don’t even think there are true English equivalents for some of Ghost’s lines, so in a sense there are two experiences of the film: one if you follow the subtitles, true to the original script, and another if you speak Sotho. Not all of our actors are Sotho speakers, either, so we also had to do some coaching. It’s safe to say we’ve been blown away by the levels of performance in a language not their own. And that includes the young stars of the film – none of them were comfortable Sotho speakers going in. None of them had ever worked in film, which is a story in itself. One of the joys of the film was seeing them come to life on screen.

We actually do have the white salesman Honest John, the Chinese shopkeeper Wei and the white police speaking Sotho intermixed with Afrikaans and/or English throughout. We wanted the world to feel fluid, and again, it’s true to life. Many white people in the area speak Sotho and Xhosa. Chinese people in the area do too. In the same way, Tau and other characters in town switch to English in some scenes depending who they’re talking to. Whatever made real sense in context of each scene. So authenticity was a guiding principle was – always with respect to the language and hopefully never in a gimmicky sense.

This was a big conversation from the very start with our US partners. They asked: would we do this in English? For international market purposes, doing it in local language is a very tough sell. But for the purpose of authenticity and nuance and performance and richness, there was never any doubt that we had to do it like this, and they believed in that principle too. We worked really hard to be as authentic as we could, especially being white filmmakers, to make sure there’s no gimmick in it. Audiences thus far really seem to have seen the efforts and appreciate the attention to the language and our approach, which is hugely gratifying.

In some ways, this is an archetypical western: The mysterious hero who returns and rediscovers his moral code; the cutout villains; the remot eness of the town; etcetera. But there is also no doubt that it is set in South Africa. The location. Marseilles is a white town in the Eastern Cape. It comes with a black township, Railway. The prologue makes it clear that it is Apartheid South Africa. La ter when Tau, the hero, returns, the new town is renamed “New Marseilles” after Apartheid. Can you talk about getting that balance between universalism and the particular setting right?

So many great westerns had political and social commentary sown into them. It’s such a pure expression of storytelling if you follow the film mantra that “all story is conflict.” In the western, the conflict is the story with core themes that are universal across the genre – man versus man, man versus himself, men versus the land and men versus the passage of time and history. But where most often westerns are about the conquest and the taking of land, we wanted to turn that back on itself and look at who is left behind and the legacy of that conquest. And it is very specifically true to the places we were traveling and researching in. We did 8000 km around South Africa visiting small towns meeting people, hearing stories, looking at history. And what we found in all these former colonial towns with European names is that the townships that were attached to them have become towns in their own right, which is a new frontier of its own, going through birth pains that mirror the genre’s themes. When we found Lady Grey, we fell in love and stayed there for a month initially, writing, exploring, meeting the townspeople and fitting the bones of our story to the place. And we went back yearly right up until shooting, getting deeper and finessing the project more each time. Authenticity was the most important, and not feeling like we were projecting a story onto the place. The film is a pure fiction genre piece, so nothing in the film is historically based, but the history and real stories we heard are infused into its DNA. And the town and its people were so involved in the film – either on screen in supporting roles or as extras, or in the real homes and locations we were shooting in, or in those who worked on our crew – that there’s a hopefully a level of authenticity that we couldn’t engineer.

Also speaking to authenticity, we have a trusted network of collaborators and friends who we specifically asked to call us out on anything that didn’t feel true, including our cast and crew. Films aren’t (or shouldn’t be) developed in a vacuum, and we had a whole industry watching and contributing to this project, and we were open at every step to advice and critique.

In the same way that we travelled and dug deep into the space of the film, we immersed ourselves in westerns — old and new, American and world, classic, Spaghetti, revisionist and neo –- both on screen and scripts, to make sure we knew the genre inside and out. It was so important that it didn’t play as a gimmick that the film is a western, and we sort of swung back and forth on how obviously western we wanted it to be. In the end it’s a delicate balance, I think, but one that seems it’s connected with people. We’ve had long-time western fans in the US who loved it, and we’ve gone deep into the genre in interviews with them. We screened in Austin, Texas and came out of that unscathed, haha. That’s been great. And at the same time we’ve had such strong responses to the real world portrayal and themes, both at home and from viewers from South Africa and Lesotho living in Canada, London, etcetera.

Is the film an allegory for present day South Africa and for the weight of the past?

I think the allegory is pretty clear, yes, in the idea of a town that’s in the process of escaping its fraught and damaged past and the birthing pains of its true freedom. But we’re hesitant to be overbearing with it. Audiences should be able to the enjoy the film for its story and characters without necessarily going deep into the allegory; it’s a genre film and we want people to be entertained and shocked and excited and moved by it, and if people are challenged, or inspired, or ask questions about themselves and their world afterwards, there’s nothing better that we could ask for, but if they don’t, we’re not going: “you missed the point.” Filmmakers and films have this amazing power to affect people and the world we live in, but I personally don’t think our role is to beat people over the head with messages or ideas. I prefer to pose questions and leave the rest in the viewers’ hands.