Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 256

March 8, 2018

Authoritarianism built into the city

Image credit Danny Hoffman.

Image credit Danny Hoffman.Children ran up and down the central stairwell as Martin led me and a small group of companions around the Liberia Broadcasting System (LBS) building on the outskirts of Liberia’s capital, Monrovia. It was the start of the rainy season. Martin lived among approximately 80 families in the ruins of the brutalist LBS, one of the largest structures in the city. Most had been in the LBS more than ten years, having fled the countryside for the relative safety of the city during Liberia’s long war.

One could clearly see how the building’s residents orchestrated their own architecture within the huge frame, carving and creating spaces as they negotiated their needs given the limits of the space. Looking down from the stair into the ground floor, pools of standing green water were a reminder of the challenges of these creative reworkings. In the torrential Liberian rains, the building’s inhabitants are violently exposed to the elements.

“A building like this should be productive,” muttered Ibrahim, a young man who had accompanied me on similar walk-throughs of heavily damaged buildings around the city. Ibrahim and I were touring the LBS in the course of researching a book on Monrovia’s modernist built environment and the urban future. In each location, he said almost exactly the same thing. It became a kind of mantra he repeated in all the city’s modernist ruins. “If you leave a building like this to the people,” he said, “it will rot and become useless.”

Ibrahim’s negative assessment of the LBS occupation represents a challenge to some of the most progressive thinking in architecture and urban design today. A good deal of the popular, scholarly, and practitioner literature on the modern city seeks to validate occupations like those of the LBS and to make it the model for new grassroots forms of architecture and urbanism. In this literature it is the work of squatters and other organic intellectuals re-imaging failed modernist architecture like Caracas’ Torre David — “the improvised home for a community of over 800 families living in an extra-legal and tenuous occupation that many called a vertical slum” — that is the most hopeful and productive for thinking about the urban future. When so much of formal urban design today is geared toward speculative real estate capital and commercial interests, a certain fetishization of the unplanned and improvisatory strategies of the urban poor has taken hold.

That romantic view of the urban future is not one shared by many Monrovians today, and certainly not one they are willing to fight for. Despite a chronic housing and land shortage, Monrovia has not seen the militant urban social movements that have emerged in cities across Latin America, North Africa, and parts of Southeast Asia. In fact, even veterans of Liberia’s war, men who continue to threaten to take up arms in the pursuit of a better future, are remarkably passive on the subject of Monrovia’s built environment. When hundreds of ex-combatants and their families were evicted from the old Ministry of Defense building, a space in which most had lived for more than a decade, they put up no real resistance. Martin said much the same of the LBS. Though they had lived there for years, and though they had few alternatives in the overcrowded city, no one wanted to claim the LBS as their own.

But if Ibrahim and others like him reject the idea of architecture without architects, there is also a disturbing element in what he proposes as an alternative. What Monrovia needs, Ibrahim argued, is someone who can forcefully impose a vision of the city and its built environment from above, rather than below. Africa’s early modernist architectural heritage was overwhelmingly state driven, but (at least rhetorically) it consisted of projects meant to symbolically unify the nation through cutting edge design and grandiose urban forms. By contrast, Ibrahim felt that the city’s infrastructure would be “productive” when it could be used as a tool for making the flow of money more efficient and the generation of profit more fluid. Ibrahim seemed to feel that the city and its built environment could only serve the nation under an authoritarian figure powerful enough to reclaim spaces like the LBS and make it part of his personalized network of political, economic, and social patronage. It is a disturbingly common sentiment in a city buffeted by years of poor administration, warfare, and, most recently, economic collapse under the scourge of the Ebola epidemic. To work as a city, according to this line of thinking, what Monrovia needs is not pubic works and infrastructure so much as a return to the crony capitalism (and accompanying state violence) of the Charles Taylor regime, Liberia between 1997 and 2003. (This perhaps makes some sense of the veiled promises of current Liberian Vice-President Jewel Howard-Taylor to restore the brutal order that characterized the rule of her former husband.)

The architectural historian Andres Lepik recently argued that what is presently missing from African architecture, and by extension from a more progressive and appropriate vision of the African city, are high quality reference buildings. There is no doubt a good deal of truth in that. But a more important absence may be a serious critical conversation about kind of city an African architecture is for.

March 7, 2018

One Percent Feminism

Christine Lagarde at the World Economic Forum in 2013. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Christine Lagarde at the World Economic Forum in 2013. Image via Wikimedia Commons.This past January’s World Economic Forum — the annual shindig of the world’s super rich and their acolytes — garnered attention for being co-chaired entirely by women for the first time in its forty-seven year history. The organizers obviously hoped this would begin to address gender inequality at a conference where women comprised only twenty-one percent of attendees. But before we celebrate, it is worth taking in critical theorist Nancy Fraser’s injunction that this sort of female representation is a superficial detraction; it “embodies a neoliberal kind of feminism which mostly benefits privileged women.”

Literary theorist Walter Benn Michaels articulated the link between one percent feminism and neoliberalism concisely:

…It’s basically OK if economic differences widen as long as the increasingly successful elites come to look like the increasingly unsuccessful non-elites. So, the model of social justice is not that the rich don’t make as much and the poor make more, the model of social justice is that the rich make whatever they make, but an appropriate percentage of them are minorities or women” [My emphasis].

Christine Lagarde, the female head of the International Monetary Fund, presided over the event. Lagarde tried to be clever: this is a “panel, not a manel,” she quipped during the introductory session.

Hillary Clinton’s loss in the US presidential elections in 2016 brought her feminist record under scrutiny. She famously remarked at a UN conference in 1995 that human rights are women’s rights and women’s rights are human rights once and for all. Yet, her support for access to birth control and abortions falls short of holistic approaches in other developed democracies that include childcare and paternity leave. In 1996, as US First Lady, Clinton supported a welfare reform bill that made daily life precarious for low-income American women. As secretary of state under Barack Obama, Clinton’s hawkish foreign policy stance aligned with neoconservatives such as Robert Kagan. She strongly supported the war in Iraq which produced grave physical and economic insecurities for a generation of Iraqi women. United States intervention in the Middle East precipitated its destabilization, and ultimately triggered the xenophobic backlash that has boosted conservatism and renewed the urgency to fight for women’s equality in the United States.

One year after the historic Women’s March in Washington, D.C., some Clinton supporters, who flooded the streets in a sea of pink knit hats, are reconsidering these objects as unserious symbols of an activism not fit for these times. In her memoir What Happened, Clinton cast blame on a disaffected young woman for failing to vote in the 2016 election. Since then, Clinton has rebuffed criticism for her close relationship with serial predator Harvey Weinstein, and for protecting a campaign advisor accused of sexual harassment, and has receded from the public eye.

Liberal feminism asserts that the duty to advance feminism calls for individuals to modify their behaviors and expectations, such as by “leaning in,” coined by Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg. Sandberg has partnered with other powerful women—former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, and Anna Maria Chavez of the Girl Scouts—to spread the message of female self-empowerment. Yet, promoting women into positions of power and on boards of directors aligns with corporate goals and enhances companies’ bottom line. On the other hand, cooperation among working class women often begins inside a workplace with no support to “lean in” to, at great personal risk.

So, who were the three co-chairs of the WEF and what are their politics?

Most prominent among the seven co-chairs, were Ginny Rometty, CEO of IBM, Prime Minister of Norway Erna Solberg, and Managing Director of the IMF, Christine Lagarde.

Ginny Rometty became the first female CEO of IBM in 2011. She has defended herself against critics for advising Trump after the disbanding of his Strategic and Policy Forum, when he blamed “both sides” of a white supremacist attack in Charlottesville, VA. Under Rometty’s leadership, IBM has seen the number of jobs offshored rise to 130,000, or one third of all IBM jobs, to India where salaries are a fraction of US salaries.

Rometty has championed IBM’s AI known as Watson, as a tool for national security, in a security culture that increasingly targets majority Muslim countries and communities within the United States. Some have drawn parallels between Trump’s previous calls for a Muslim registry with a dark moment in IBM’s past, when its first CEO, Thomas J. Watson, provided Hitler’s Nazi regime with technology to compile machine-tabulated census data in 1933.

In her role as managing director of the IMF, Christine Lagarde “looks under the skin of countries’ economies” to diagnose them. She has called upon leaders to promote women’s equality, yet the IMF has historically pursued measures that push countries to adopt austerity measures which disproportionately affect women. Feminist economists protested the imposition of austerity in Greece, where a study found it to be driving women into prostitution. Although the IMF has since examined its policies in this area, Lagarde has recently backed away from a plan to further alleviate Greece’s debt crisis.

Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg, is the second ever female Prime Minister of Norway since 2013 and leader of the center-right, Conservative Party since May 2004. Solberg’s coalition government includes the “neoliberal populist” Progress Party, which gained support for its anti-immigration stance amid the global migration crisis, and her tenure has brought policies of economic liberalism, tax reductions and promotion of public-private partnerships. Yet, whereas Hillary Clinton invoked the rhetoric of women’s empowerment as First Lady, to support the dismantling of the US welfare state, Solberg’s government continues to promote gender equality through policy initiatives and a robust safety net.

The closing plenary of the 2018 World Economic Forum highlighted the vast gulf between one percent feminists and the millions of men and women who lack basic human rights that they purport to care about. Among the panel of artists, famed British portrait photographer Platon Antoniou shared the photograph of a woman from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where rape has become a tool of warfare in resource conflicts fueled by primarily Western consumption of minerals used in product manufacture.

“I’d like you to look at Sandra. Isn’t she beautiful? Sandra was raped with extreme violence,” he began, reminding his carefully listening audience that, “we are all strangely connected to this problem.”

The role of art is critical at disjunctive times like these. Sandra, the survivor, recognizing an opportunity to have her message carried to a room in which multiple individuals possessed more wealth than the total GDP of her country in 2017, called on Antoniou specifically to deliver her message. As long as global capitalist systems, some of which may be led by all-female boards of directors, perpetuate extreme inequality, mainstream feminism will not break down the connections that built the Davos men and women. Still, the artist implored his audience: “There is a moral battle raging out there, and we have to do something about it by closing the empathy gap.”

Light applause filled the room.

March 6, 2018

Drake’s Plan

Canadian rapper Drake recently went on a giving binge in South Florida. The giving doubled as visuals for his single, “God’s Plan.” What is he trying to say? That’s when we asked around the office. The participants are Sean Jacobs, Dylan Valley, Boima Tucker, Shona Kambarami and Haythem Guesmi.

***

Sean: What did you make of this?

Drake – “God’s Plan”

Boima:

March 5, 2018

Burkina Faso and the realization that it is possible to win

Image by Eric Montfort. CC via Flickr.com

Image by Eric Montfort. CC via Flickr.comActivists most often focus on the grievances and challenges immediately in front of them. But in Burkina Faso many do so with one eye cast back, towards the historical precedents of popular action. In their speeches and writings Burkinabè debate the lessons of those prior struggles. In part, they do so in hopes of avoiding earlier blunders and shortcomings, to stand on the shoulders of the past. Yet frequently they also consciously draw inspiration from previous triumphs. Victories beget victory.

In Burkina Faso’s case, such popular successes have been significant, especially on a continent marked by so many movements that have been repressed or co-opted by entrenched elites. The most recent was a massive citizens’ insurrection that toppled the authoritarian regime of Blaise Compaoré in October 2014, a development analyzed in detail in my new book, Burkina Faso: A History of Power, Protest and Revolution (London: Zed Books, 2017).

Authoritarian rulers elsewhere in Africa have also faced widespread opposition in the streets. Sometimes such mobilizations led indirectly to a ruler’s downfall. For example, popular agitation in Niger culminated in a 2010 military coup that pushed aside an autocratic president, Mamadou Tandja, and opened the way to subsequent elections. And in 2011, street mobilizations in Senegal blocked Abdoulaye Wade’s attempts to subvert the constitution, contributing to his electoral defeat the following year.

Yet, apart from the Arab Spring uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia earlier this decade, the 2014 uprising in Burkina Faso was a rare instance in Africa of a popular movement that managed to directly topple a sitting government.

Like many of his contemporaries on the continent, Compaoré tried to follow the common playbook of adhering to the formal tenets of multi-party democracy but in reality managing a closed political system based on a mixture of electoral fraud, the patronage of a dominant party-state and repeated constitutional manipulations. By 2013 that system began to fray, as Compaoré, in office since a 1987 military coup, pushed too far by seeking to once again extend the presidential term limit. Already incensed by widespread poverty, rights abuses, and rampant corruption, people across the country reacted were outraged. Their indignation fueled months of massive protests in the streets and pushed the divided opposition parties, activist groups and labour unions to come together in a coordinated struggle that culminated in the October 2014 events.

Memories of struggle

Opposition leaders and rank-and-file activists alike cited a litany of earlier movements and uprisings. Those experiences led them to believe that “insurrection is rooted in the DNA of the Burkinabè people,” as Guy Hervé Kam, the spokesperson of the prominent activist group Balai citoyen, put it. Those struggles included a January 1966 labour-led insurrection that toppled the country’s first president and a general strike in 1975 that blocked a general’s attempt to impose a single state party.

Numerous other instances of popular opposition erupted during Compaoré’s rule. Two prolonged and intense protest waves were particularly notable. The December 1998 assassination of Norbert Zongo, an independent newspaper editor, set off such sustained protests and strikes that the Compaoré regime seemed to totter on the edge of collapse. Only significant concessions and promises of reform ensured its survival. Then throughout the first half of 2011 came a succession of student and youth demonstrations, labour marches, merchants’ protests, judges’ strikes, farmers’ boycotts, attacks on the homes of leading political figures, and widespread army and police mutinies.

Many of today’s activists drew lessons from those struggles: that popular mobilization on a significantly wide scale could weaken and de-legitimize the authorities; that segments of the political elites and security forces were themselves somewhat divided; and that joint protest campaigns are more effective than dispersed and uncoordinated actions.

Sankara’s revolution

Although some contemporary activists had their formative experiences in these protest movements, few could themselves remember the revolutionary era of President Thomas Sankara (1983-87). Many had not yet been born or were children at the time of his assassination by Compaoré’s coup-makers. Yet Sankara’s name resonated strongly during subsequent decades and reached a crescendo during the 2014 insurrection.

The Sankara government was short-lived, but its vigorous action carved a central place in Burkinabè popular lore—and indeed across West Africa. Activists cited Sankara’s massive popular self-help mobilizations, efforts to advance women’s rights, and strong advocacy of pan-Africanism and anti-imperialism, among other positions and initiatives. Burkina Faso’s very name, which means “land of the upright people” and replaced Upper Volta in 1984, has helped redefine national identity, not just for those who idolize Sankara, but across the political spectrum.

The rap artist Smockey, a central founder of Balai citoyen, explained why the activist group adopted Sankara as its symbolic patron. As an individual, Smockey told me, Sankara’s image was that of “simplicity, modesty, and integrity … a model for anyone aspiring to manage public property.” He also recalled Sankara’s political “courage and determination to build a Burkina Faso of social justice and inclusive development.”

Martyrs and victories

In annual commemorations, official holidays, the erection of monuments and other symbolic events, Burkinabè are making conscious endeavour not only to recognize past struggles, but also to educate future generations. Burkina Faso’s previous pantheon of popular heroes has now been supplemented by the “martyrs” of the October 2014 uprising and those who fell during an abortive September 2015 coup attempt by Compaoré’s former presidential guard. Plans are underway to transform the old National Assembly building, badly burned during the insurrection, into a public museum. Just down the same street in central Ouagadougou, the old Conseil de l’Entente complex where Sankara was assassinated will become part of a national commemoration to the late revolutionary.

Meanwhile, segments of Burkina Faso’s neglected anti-colonial history are also receiving attention. In November 2017, for the first time, festivities were organized to mark the widespread and prolonged armed rebellion against French colonial forces a century earlier, in 1915-16. Little known or studied until recently, that revolt in the western parts of the country was notable for its multi-ethnic character and initial military victories. It took major French reinforcements and heavy artillery fire to finally put down the resistance, at a cost of an estimated 30,000 lives.

Evocations of martyrs are emotionally powerful symbols that help solidify movement identities by fostering pride in past struggles. Simultaneously, recalling murdered heroes, such as Thomas Sankara and Norbert Zongo can underscore the inhumanity and injustice of those responsible, thus further legitimizing popular opposition.

Nothing, however, encourages people to undertake the risks of open defiance more than the realization that it is possible to win. Popular victories in other countries can also be inspiring, especially in this digital age when images of mobilized masses and fleeing dictators travel so quickly. Yet the knowledge that one’s own forebears were able to triumph is particularly empowering.

With each successive struggle, the Burkinabè people have deepened their culture of rebellion. That heritage of revolt contributed to the downfall of a detested president in 2014. In the view of a number of activists, it may also hopefully dissuade future leaders from pursuing similarly oppressive practices. As Fousseini Ouédraogo, a participant in the anti-Compaoré movement, commented, “Whenever someone threatens the people’s interests, there are always those who react and say, ‘No!’”

March 4, 2018

Weekend Special, No. 1995

The past few month have not been good for longtime African leaders who have been forced to step down, from Robert Mugabe to Hailemariam Desalegn [qualification: in the latter’s case, he is a representative of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, in control of Ethiopia’s government since 1995, but you get the picture]. An upcoming slew of elections in the first half of the year could prove problematic for many more. In Sierra Leone, for one, a new party—The National Grand Coalition—could bring down the hegemony of the Sierra Leone People’s Party, and All Peoples Congress, both of who have have essentially held power exclusively since independence. This election, surely, might become a true test for the strength of the political institutions.

Further north, the “international community” is determined to hold elections in Libya. Sometime in 2018. But in whose interest?

Across the Mediterranean, African migrants, and immigration, are having an outsized impact on the Italian elections.

Speaking of Italy, an anthropologist looks at the economic incentives behind migration of women who end up doing sex work. And how the focus must change in the narrative, is there is to be any success.

This week marked the 133rd anniversary of the Berlin Conference. From the Anglophone crisis in Cameroon to conversations around the Single African Air Transport Market, we find ourselves still coming up against those Berlin Walls erected on the continent then.

Two former US ambassadors to Kenya call for American intervention in Kenya.

“Today, more Congolese are displaced from their homes than Iraqis, Yemenis, or Rohingyas,” and as has been the case historically, external interference continues to destabilize it.

A decade after assault and attacks from the Lords Resistance Army, Ugandan women still carry the burden of trauma.

What Maya Angelou’s time in Egypt says about the Arab-Black solidarity in the 50s and 60s.

And yes; Black Panther is a little anti-Muslim.

Keorapetse Kgositsile was a feminist

I was raised blue-black by hip hop culture,

imbibing the legend of a South African poet

who christened the grandfathers of rap

with a name:

The Last Poets

We rocked Karl Kani jeans back-to-front like

Kriss Kross,

strapped Timberland boots in the scorching sun of Lebowa townships.

We crafted a way of life that was our own:

Made with our beats, our clothes and our art

a counterculture to apartheid,

which existed to clip our wings,

and stymie our very aspirations to fly.

African American culture was both exotic and familiar: here were these “others” who looked like us, dared to own themselves, and had the audacity to assert that at our best we are love.

These memories are the foundation of my career. When I started taking poetry seriously after high school, I sought that legendary poet out. I was hypnotized even then, by his name: Keorapetse Kgositsile. Who was this man with a name that rests easy on my tongue; that uncoiled ancient sounds in my ear?

In Johannesburg in the early 2000s, the lyrical, pan-African musings of former South African President, Thabo Mbeki, spawned a movement of dashiki-clad, Afro-donning Biko disciples. There we were, brandishing mutilated psyches, attempting self-medication. Like the Black Consciousness era of our collective yesteryears we resurrected an uncompromising blackness on which to tether our self-determination. Poetry was our medium, and we looked to the black archive for its sounds, rhetoric, performance, and heroism. It affirmed us: we are of unyielding strength, capability and creativity, despite the narrative of the racist fascists. In the heat of our screams interjected the resonant voice of our elder, returning from exile and transforming a harmattan of colors into areas of feeling: the legend of Kgositsile was in our midst. I heard his voice, and longed to sit at his feet.

The impetus was unrelenting. Access to Kgositsile’s poetry led me to focus my doctoral research on his life and work, which led to our first meeting in 2012. I started collecting any and all evidence of his work and mapping traces of humanity he left across the continents where he was exiled.

In five years of conducting interviews with his family, comrades, and fellow writers in both South Africa and the United States, he became a father, a mentor, a supervisor, and a gracious biography subject. He was selfless in his commitment to what became the KWK (Keorapetse William Kgositsile) project.

There is much I can draw upon to share with you of his many lives, but I will speak here of the women who shaped his radical, collectivist and material approach to culture, politics, and revolution, which he espoused to the very end.

Kgositsile spoke of his grandmother, Madikeledi, and his mother Galekgobe, as the kernel through which his quest to seek and engender community took root. He credited them for helping to develop the deep sense of custom, community, and culture evinced in his poetry. In particular, he spoke lovingly of the fact that Madikeledi insisted that they only speak Setswana in the household. He also remembered how she taught him to question the myth of nation state on the continent. Madikeledi was a victim of forced removals and dispossession, and so she pointed across the border to Botswana as home. It was in part because of these early teachings, that land, community and language became such significant preoccupations for the revolutionary poet.

When he went to America, he carried an oeuvre of Setswana classics with him across the Atlantic. These stories and their idiom were a material representation of his cultural archive; an aesthetic that would ensure he never expressed himself like a white man.

Keorapetse Kgositsile at Kelly Writer’s House. Image via Flickr.

Keorapetse Kgositsile at Kelly Writer’s House. Image via Flickr.In exile he identified the African American parlance and jazz as an extension of this rebuttal of whiteness and an affirmation of blackness. As a result, he fought with African Americans against white supremacy and American imperialism. When his contemporaries embraced their African identities by renouncing their slave names, for example LeRoi Jones to Amiri Baraka, one Detroit-based civil rights activist and poet Gloria House changed hers to Aneb Kgositsile. His socialist commitments derived from the matri-archive: a collectivist approach embedded in oral transmissions of social values and cultural imperatives from his matrilineal upbringing.

Where relationships between black South Africans and black Americans are recorded – between Es’kia Mphahlele and Langston Hughes, Solomon Plaatje and W.E.B. Du Bois, and Peter Abrahams and Richard Wright for example – the relationship between Kgositsile and Gwendolyn Brooks is striking and particularly unique. It disrupts the narrative of gender relations during the Black Power and Black Arts movement, whose legacy is plagued by charges of misogyny and overshadowing masculinity. Brooks and Kgositsile had a relationship of mutual admiration; evidenced by the fact that Brooks penned a moving introduction to his 1971 poetry collection My Name is Afrika.

In the introduction of his sophomore collection, For Melba, which pays homage to his first wife, Baleka (later the Speaker of the South Africa’s democratic parliament) and their daughter, Ipeleng, he expressed shock over the disrespectful treatment of women in his American black community. Sterling Plumpp, literary scholar and Kgositsile’s life-long friend, rightly concluded that Kgositsile’s becoming as a revolutionary writer can be studied through his poems dedicated to Ipeleng.

On his return to the continent, in Tanzania, Kgositsile nurtured a personal and revolutionary friendship with ANC activist Kate Molale at the Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College in Morogoro, during a time when he travelled with communist party stalwarts across the larger Soviet Union. He penned two tributary poems for Molale—a leading figure in third worldist feminist politics—upon her death in 1980. His sixth collection of poetry – a body of poetry dedicated to women – was published in East Germany, and conceived to raise funds for ANC’s Voices of Women, the organ for the women’s league in exile. It was through Kgositsile’s poem that I learnt of Black Consciousness poet Ilva Mackay, otherwise erased by history from that canon of literature. The project of mapping his life and work cannot be a finalized without considering the influence of women in his becoming.

On his return home to democratic South Africa, Kgositsile’s commitment to nourish and mentor a new generation of writers saw him in the company of, and at the centre of, an emerging body of poetry by black women, among them Lebogang Mashile and Phillipa yaa De Villiers, with whom he travelled the world to poetry festivals and conferences. When I pointed out his her-story with women we shared a few laughs at this cosmic joke which sent a young black South African woman to be his biographer. He found it fitting.

In our time together, Kgositsile never held anything back. As he made his final crossing, I launched a 21-poem-salute for this statesman, revolutionary, and poet extraordinaire. Pula.

March 3, 2018

Does China have the power to change governments in Africa?

The idea that China is influencing regime change in Africa, became popular in the wake of the military coup in Zimbabwe that ended Robert Mugabe’s 37-year rule there. Western media was particularly taken by this thesis. Zimbabwean Army Chief General Constantino Chiwenga, the man at the head of the coup, visited Beijing the prior week, presumably to get the approval of the Chinese Communist Party. This was presented as the smoking gun.

As the Financial Times–paper of record for the world’s corporate and government leaders–speculated at the time: if China’s interests would be affected by the Zimbabwe coup, it would adjust to the flow of political change. The lesson to other African dictators was that your opponents might “persuade China to look the other way as you are pushed out the door …,” according to an analyst quoted by the FT. For that reason, the same analyst suggested that other African dictators long supported by China might be closely watching events in Zimbabwe. The FT noted, however, that there was little indication that Beijing had direct influence on the move against Mr Mugabe and “we should not exaggerate the actual role of China.”

Despite further caution from China scholars, Western media continued to cite Chiwenga’s visit to Beijin as “evidence” to build the narrative that despite China’s professed non-intervention principle — i.e. that China is wary of doing to another what it does not want done to itself — it was intervening and influencing regime change in Africa. A recent investigation by French newspaper Le Monde — that China spied on the headquarters of the African Union, just added to the speculation.

So, is China really influencing regime change in Africa? The short answer to that complex question is no.

China has no wherewithal nor the will to influence regime change either through military means or clandestinely supporting opposition movements in African countries. The solidarity between China and Africa is founded on that understanding and a shared detest of neo-imperialism and intervention in each other’s’ internal affairs. As Li Keqiang puts it: “Like many African countries, ‘China once suffered foreign invasion and fell under colonial and semi-colonial rule. Do not do to others what you do not want done to you’ is a millennia-old idea important in Chinese civilization” and the bedrock of China-Africa relations.

Second, China has no formal or informal security cooperation arrangements with any country, regime or leader in Africa. High-level exchanges and cooperation between the Communist Party of China and political parties such as Tanzania’s ruling party, Chama Cha Mapinduzi, or Zimbabwe’s ruling ZANU-PF or military exchanges with African countries, do not constitute an undertaking by China to protect these political parties from internal threats in their own countries. For example, Mamadou Tandja, president of Niger from 1999 to 2010 was widely believed to be propped up by China despite his autocratic leadership. Then he was deposed in a military coup in 2010. China simply made a new deal with the new military regime.

In addition, strategic partnerships to strengthen cooperation between China and African countries, like Djibouti where China set-up its first military base in Africa, does not guarantee regime support from China. In fact, China’s military presence in Africa is still limited to anti-piracy, peacekeeping and protecting Chinese nationals and assets abroad. There is no significant possibility of the Chinese military strategically supporting or protecting regimes in Africa.

Even more important, China understands the limitations of its power and influence in Africa. Despite claims of regimes modeling themselves after China — Ethiopia’s government styles itself as the “China of Africa” — the Chinese do not have the capacity to change regimes or even mould current ones into its own image. As an editorial in Global Times, the tabloid version of The People’s Daily, acknowledged around the time of the Zimbabwean coup, among the three main factors that could affect events there, was the fact that regardless of what China wanted, “the attitude of the African Union and the West” mattered.

“Both [the African Union and the West] object to military takeovers, but Mugabe is one of the African leaders the West dislikes most. It seems the West is likely to turn a blind eye to this crisis,” Global Times further explained. (The other two factors, mentioned by Global Times, turned out to be crucial: whether the military and ZANU-PF could agree on how to solve the crisis and the level of popularity that Mugabe enjoyed amongst his people.)

The problem, however, is that the African Union is not even as decisive in African political and security affairs. First in line are former colonial powers – especially Britain and France. They’re followed by regional organizations such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) or the Southern African Development Community (SADC). For instance, Mali requested military assistance from France to wade off the Tuareg rebellion and a coup attempt. In Cote d’Ivoire, Alassane Outtara requested French Special Forces for assistance to oust his predecessor Laurent Gbagbo who was refusing to leave power after losing an election.

Apart from seeking Chinese diplomatic support against imposition of international sanctions, the fact that none of the deposed African leaders have requested for Chinese protection from internal political threats suggest that there is an understanding among African leaders that China will not assist beyond blocking international sanction, regardless of their relations.

As for opposition movements in African countries, rumored help to the coup plotters in Zimbabwe created an impression that China could support the opposition. It wasn’t an unreasonable expectation. In South Sudan, China engaged the Riek Machar rebels, while in Libya it recognized the National Transition Council before Gaddafi was completely ousted. Beyond those two cases, there is little to suggest China engages or supports opposition movements in Africa. China finds it more prudent to deal exclusively with ruling parties to protect its interests, which are mostly economic.

Opposition political leaders, most find the West more receptive, especially when their opponents are regarded as autocratic or are under sanctions of some sort. If not to former colonial powers, they look to regional powers, like South Africa in the case of Zimbabwe or Senegal in the case of the Gambia.

In all these cases, China’s power is not in intervening, but in having rival political opponents in African countries strive for its support. Incumbent regimes need China for its economic, diplomatic and political support. Opposition political parties often pro-West and anti-China soon realize their countries’ dependence on China as soon as they get into power. Zambia’s former president Michael Sata (2011-2014) was anti-China when he was in opposition but soon after getting into power, he sent Kenneth Kaunda, Zambia’s founding president to beg for Beijing’s forgiveness and renew relations.

Overall, China’s focus is on strengthening long term strategic relations thus it is willing to forego the temptation to engineer regime transitions in Africa. As it stands, China is confident that it can work with any kind of regime in Africa because China is increasingly becoming a dominant alternative for development finance for most African countries. There may be no need for Beijing to muddle in regime change in Africa.

Is China, changing regimes in Africa?

The idea that China is influencing regime change in Africa, became popular in the wake of the military coup in Zimbabwe that ended Robert Mugabe’s 37-year rule there. Western media was particularly taken by this thesis. Zimbabwean Army Chief General Constantino Chiwenga, the man at the head of the coup, visited Beijing the prior week, presumably to get the approval of the Chinese Communist Party. This was presented as the smoking gun.

As the Financial Times, paper of record for the world’s business and government leaders, speculated at the time: if China’s interests are affected by the Zimbabwe coup, it would adjust to the flow of political change. The lesson to other African dictators was that your opponents might “persuade China to look the other way as you are pushed out the door …,” according to an analyst quoted by the FT. For that reason, the same analyst suggested that other African dictators long supported by China might be closely watching events in Zimbabwe. The FT noted, however, that there was little indication that Beijing had direct influence on the move against Mr Mugabe and “we should not exaggerate the actual role of China.”

Despite further caution from China scholars, Western media were continued to cite Chiwenga’s visit to Beijin as “evidence” to build the narrative that contrary to China’s professed non-intervention principle — i.e. that China is wary of doing to another what it does not want done to itself — it was intervening and influencing regime change in Africa. A recent investigation by French newspaper Le Monde — that China spied on the headquarters of the African Union, just adds to the speculation. So, is China really influencing regime change in Africa?

The short answer to that complex question is no.

China has no wherewithal nor the will to influence regime change either through military means or clandestinely supporting opposition movements in African countries. The solidarity between China and Africa is founded on that understanding and a shared detest of neo-imperialism and intervention in each other’s’ internal affairs. As Li Keqiang puts it: “Like many African countries, ‘China once suffered foreign invasion and fell under colonial and semi-colonial rule. Do not do to others what you do not want done to you’ is a millennia-old idea important in Chinese civilization” and the bedrock of China-Africa relations.

Second, China has no formal or informal security cooperation arrangements with any country, regime or leader in Africa. High-level exchanges and cooperation between the Communist Party of China and political parties such as Tanzania’s ruling party, Chama Cha Mapinduzi, or Zimbabwe’s ruling ZANU-PF or military exchanges with African countries, do not constitute an undertaking by China to protect these political parties from internal threats in their own countries. For example, Mamadou Tandja, president of Niger from 1999 to 2010 was widely believed to be propped up by China despite his autocratic leadership. Then he was deposed in a military coup in 2010. China simply made a new deal with the new military regime.

In addition, strategic partnerships to strengthen cooperation between China and African countries, like Djibouti where China set-up its first military base in Africa, does not guarantee regime support from China. In fact, China’s military presence in Africa is still limited to anti-piracy, peacekeeping and protecting Chinese nationals and assets abroad. There is no significant possibility of the Chinese military strategically supporting or protecting regimes in Africa.

Even more important, China understands the limitations of its power and influence in Africa. Despite claims of regimes modeling themselves after China — Ethiopia’s government styles itself as the “China of Africa” — the Chinese do not have the capacity to change regimes or even mould current ones into its own image. As an editorial in Global Times, the tabloid version of The People’s Daily, acknowledged around the time of the Zimbabwean coup, among the three main factors that could affect events there, was the fact that regardless of what China wanted, “the attitude of the African Union and the West” mattered.

“Both [the African Union and the West] object to military takeovers, but Mugabe is one of the African leaders the West dislikes most. It seems the West is likely to turn a blind eye to this crisis,” Global Times further explained. (The other two factors, mentioned by Global Times, turned out to be crucial: whether the military and ZANU-PF could agree on how to solve the crisis and the level of popularity that Mugabe enjoyed amongst his people.)

The problem, however, is that the African Union is not even as decisive in African political and security affairs. First in line are former colonial powers – especially Britain and France. They’re followed by regional organizations such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) or the Southern African Development Community (SADC). For instance, Mali requested military assistance from France to wade off the Tuareg rebellion and a coup attempt. In Cote d’Ivoire, Alassane Outtara requested French Special Forces for assistance to oust his predecessor Laurent Gbagbo who was refusing to leave power after losing an election.

Apart from seeking Chinese diplomatic support against imposition of international sanctions, the fact that none of the deposed African leaders have requested for Chinese protection from internal political threats suggest that there is an understanding among African leaders that China will not assist beyond blocking international sanction, regardless of their relations.

As for opposition movements in African countries, rumored help to the coup plotters in Zimbabwe created an impression that China could support the opposition. It wasn’t an unreasonable expectation. In South Sudan, China engaged the Riek Machar rebels, while in Libya it recognized the National Transition Council before Gaddafi was completely ousted. Beyond those two cases, there is little to suggest China engages or supports opposition movements in Africa. China finds it more prudent to deal exclusively with ruling parties to protect its interests, which are mostly economic.

Opposition political leaders, most find the West more receptive, especially when their opponents are regarded as autocratic or are under sanctions of some sort. If not to former colonial powers, they look to regional powers, like South Africa in the case of Zimbabwe or Senegal in the case of the Gambia.

In all these cases, China’s power is not in intervening, but in having rival political opponents in African countries strive for its support. Incumbent regimes need China for its economic, diplomatic and political support. Opposition political parties often pro-West and anti-China soon realize their countries’ dependence on China as soon as they get into power. Zambia’s former president Michael Sata (2011-2014) was anti-China when he was in opposition but soon after getting into power, he sent Kenneth Kaunda, Zambia’s founding president to beg for Beijing’s forgiveness and renew relations.

Overall, China’s focus is on strengthening long term strategic relations thus it is willing to forego the temptation to engineer regime transitions in Africa. As it stands, China is confident that it can work with any kind of regime in Africa because China is increasingly becoming a dominant alternative for development finance for most African countries. There may be no need for Beijing to muddle in regime change in Africa.

March 2, 2018

Liberia’s stress test for democracy

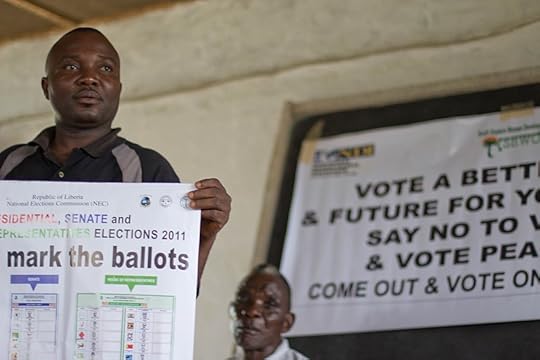

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.The recent presidential and legislative elections in Liberia and the series of court challenges that preceded it, certainly tested the country’s fragile institutions. In the end, the courts, the National Elections Board, and the candidates themselves all seem to have proved their ability to withstand pressure. It was with relief and a new confidence in their constitution and their institutions that Liberians inaugurated their new president, George Weah, at the end of January.

The October 2017 election, Liberia’s third since the 2003 peace agreement and the first to be conducted without the support of a large United Nations Peace-keeping force, was successful in peacefully and democratically transferring power from one party to another. This was the first time since 1884 that such a transition had occurred. Although effectively a single party state from 1878 to 1980, Liberian elections in the past were hotly contested and internal competition within the ruling True Whig Party was fierce. As the oldest independent republic on the continent, no one could claim that Liberians were unfamiliar with representative democracy or with the process of elections. The post-war period (2003 through the present) has seen over twenty different candidates run for president in each of the past three elections. Although the present constitution was the result of interference and manipulation by military leaders in the 1980’s, it provides the basic structure for an independent judiciary and the separation of powers between executive, legislative, and judicial branches. As documented by Liberian media scholar Carl Patrick Burrowes in his book, Power and Press Freedom in Liberia, 1830-1970, there is a long history of a vibrant and diverse press and professional standards of journalism, although sometimes operating under extreme pressure from the central government. No one needs to instruct Liberians on how democratic governance is supposed to operate; the question since the return to civilian rule has been how quickly their fragmented institutions could be rebuilt.

What is to be learned from the performance of Liberian democratic institutions in this, their third post-conflict stress test? The record is mixed, but overall, there is much to be hopeful about for the future. In the first round which took place on October 10, 2017, Liberians were presented with a field of twenty candidates, of which only three had a real chance of success. The sitting Vice President, Joseph Bokai, represented the incumbent Unity Party, led for the last twelve years by retiring President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. George Weah, a former World Soccer Player of the Year, and leader of Congress for Democratic Change, and lawyer Charles Brumskine, of the Liberty Party were both perennial challengers who had run in 2005 and 2011. A long list of other candidates, some familiar names and others new to politics, represented small parties or particular interest groups. As in the two previous elections, no candidate received a majority of the votes, leading to a run-off between the top two candidates (Bokai and Weah). Demonstrating their commitment to the process, seventy-five percent of eligible citizens turned out to vote in the first round.

Although international observers from the African Union and other bodies had judged the election to be fairly and transparently conducted, the third place finisher, Brumskine, challenged the results to the Supreme Court. Brumskine was joined in this challenge by Bokai, who had come in second despite being the “quasi-incumbent” from the ruling party. Both questioned the long wait times at some polling stations and the use of pre-printed ballots as “demonstration” tools. The second and third-place candidates appealed to the National Elections Commission, and when their complaint was rejected, the matter when to the Supreme Court. The run-off, which should have been held on November 7, was postponed while the court investigated. On December 7, the court ruled that while there had been irregularities, there was no evidence of widespread fraud, although they directed the National Elections Commission to “clean” the voter rolls to avoid duplicate registrations. The new date for the run-off was set for December 26, an inconvenient choice in a country where Christmas is widely celebrated.

Western political scientists have tended to see African courts as mistrusted by their citizens and too much under the sway of incumbents to be much use in opposing an entrenched regime. In this instance, the representative of the incumbent party, Bokai, joined the suit when he received fewer votes in the first round than he was expecting; there is some evidence that this may have cost him support in the second round, since most Liberians were dismayed that the run-off was delayed. Bokai was also undermined by his association with outgoing President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. He had served as her vice president for at least 12 years. To top it, Sirleaf was openly campaigning for Weah. The National Elections Commission, the Supreme Court, and the contesting parties all behaved according to their constitutional requirements. Although the courts, at all levels, are still seen as corrupt and too easily swayed by a powerful executive, in this case they were viewed as having upheld the fundamental will of the people as expressed in the first-round ballot. The run off was conducted peacefully on December 26 last year with a respectable turnout of 55.8%. Shortly after the result was announced, on New Year’s Day, the two men met for a courtesy visit at Boakai’s home, pledging to work together for the good of the country.

There are many challenges ahead for the new administration, but the courts, the press, and the citizenry at large can all be proud of the demonstrated health of their political institutions. We can only hope that their American counter-parts will hold up as well.

No noose or barbed wire is thick enough to hide the sun

Still from film Kalushi.

Still from film Kalushi.The 2016 feature film, Kalushi, on the life and times of one of South Africa’s most celebrated young hero-martyrs, Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu, resonates with recent youth revolt and longer, deeper movements for change. Directed and produced by Mandla Dube with stirring music by Rashid Lanie, the all-South African film stars Thabo Remetsi as Solomon, Pearl Thusi as Brenda Riviera, Gcina Mhlophe as Solomon’s mother Martha, with a bit part for Jacob Zuma (by Bhekisisa Mkhwane). It was shot on location in Tshwane, Johannesburg and Madibeng. From its opening sequences to its powerful end, the movie is South African through and through.

The story, which can be glimpsed from the film’s trailer, is well known: Solomon grows up in Mamelodi, is radicalized, joins the ANC’s military wing, Umkhonto weSizwe (MK), and returns to contribute to liberation. In June 1977 in Johannesburg, the mission runs off the rails, there are tragic shootings, he is captured, tortured and under growing white pressure, is denied justice and brutally hung on April 6, 1979, despite widespread national and international protests and efforts of legal allies such as Priscilla Jana. All this is brought out well. In the moving final scenes of the trial, he defiantly declares: “All we want is freedom… equality… I am one of many, a foot soldier. There will be many to follow… [You] can’t stop the tide of revolution.” Jana visited him on death row after the controversial ‘common purpose’ law was used to sentence him: “His face was completely deformed … There should have been a maximum five years’ imprisonment…. He told me…: ‘Tell my people that I love them. Tell them to continue the fight. My blood will nurture the tree that bears the fruits of freedom.’’’

Solomon’s legacy, and the film itself, generated controversy and debate especially in South Africa when it first came out. Mamelodi is a township in Tshwane, controlled by the Democratic Alliance, so when the city’s mayor declared his “State of the Capital Address” in honor of Mahlangu, ANC supporters vigorously objected. There were struggles to secure finance, lack of footage of Mahlangu, and a need to educate the cast. One stimulus for Dube to make the movie was how little his students at Wits University in Johannesburg (he teaches film there) knew about Mahlangu; another was to confront burning issues, such as the predicament of youth and also xenophobia, adding on the latter that “if Solomon were alive today, he would be very upset with the situation.”

Critics could not agree, as is often the case with movies. A political analyst, Xolani Dube, characterised the film as romanticizing Kalushi’s politics, whereas film critic Sihle Mthembu felt it situated Solomon in his community/family context. Another critic saw its strength as its uncompromising politics. In the end, the movie received strong reviews and awards including the Zanzibar International Film Festival Chair’s Award, best film at Luxor African Film Festival in Egypt, Best Actor for Thabo Rametsi at BRICS International Film Festival in Chengdu, China, and Best Soundtrack/South African Film at Rapid Lion in Johannesburg. It was “the struggle film we have been waiting for even though we thought we had lost our appetite for apartheid atrocities on screen,” according to local Sunday newspaper newspaper City Press.

The film subtly reflects on South African history, politics and culture. Solomon ruminates that his family were “forcefully removed from their land and thrust into poverty,” his father buried on a barren scrap of land. History lessons regurgitated to him as a schoolboy were “Not HIS story but OUR story”! There is jazz, contestation over a prized Miles Davis LP, revolution is in the air; there is Mahlangu as a hawker helping to support his mother, and with his girlfriend Brenda. Mobilisation in 1976 against Bantu Education and the June 16 bloodbath spur eventual radicalization.

Others have earlier sought to give voice to Kalushi’s sacrifice. A 1982 documentary for the by activist, poet and director Barry Feinberg, The Sun Will Rise, included interviews with Martha and parents of others on death row; it was one of those very effective mobilizing struggle videos that made the rounds. Solomon was affectionately remembered by many poets, from Dennis Brutus, Sankie Nkondo, Rebecca Matlou and ANC Kumalo (Ronnie Kasrils) to Dikobe wa Mogale (Ben Martins), also a jailed and tortured MK cadre, who imagined Kalushi’s thoughts facing the gallows:

No noose or barbed wire / is thick enough / to hide the sun

Then there is the (auto)biographical novel Solomon’s Story, a fictional account of the true story of Solomon Mahlangu, by Judy Froman. Artist Judy Seidman drew telling posters in his honor.

Much later, still another artist, Brett Murray, to take a very sharp dig at post-apartheid corruption, arousing intense controversy.

The film makes use of the heritage, the legacy of the liberation movement in a much more linear, but effective way. It is not only the moving story of Solomon, but also the story of black youth, of MK, the memorialization of a gigantic struggle encapsulated in the real life struggles of Solomon and his friends, comrades and families against powerful enemies with all their disjuncture and fateful decisions. It is national epic played out at the level of the everyday and ordinary people.

The legacy of Solomon himself has grown. The Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College was founded in 1977 at Mazimbu, near Morogoro, Tanzania, and played an important role in exile, building skills and political understanding among a new generation of fighters. The then ANC leader, Oliver Tambo, described Solomon as “towering like a colossus, unbroken and unbreakable. In his death this spirit towers over us.” Kalushi is commemorated in Solomon Mahlangu Freedom Square in his hometown Mamelodi, where on April 6 1993 his body was solemnly reinterred. In the square stands his bronze statue, erected in 2015. In Durban, South Africa’s third major city, a major arterial road honors him.

Dube took his own dramatic license, as all directors do. In my opinion the result succeeds both as movie and reasonably accurate historical narrative. There are subtle plays on debates around the effectiveness of the liberation struggle. Courtroom reconstructions work well, even if such encounters are well known from other movies. The early sections are to me some of the best: the conscientization of youth; the myriad social and cultural contradictions swirling around young people — surely appealing and realistic to any generation.

The film was released against the background of the spirited and militant student/youth “Fallist” (#FeesMustFall) protests on South African university campuses from October 2015 through 2016. Under student pressure, Wits Senate House was renamed Solomon Mahlangu House. And activists enthusiastically took up and emblemized a song about Solomon.

This was not the first song in his honour. At the University of Zimbabwe in 1988, the Zambuko/Izibuko community theatre group, which included novelist Tsitsi Dangarembga, sang a song of Solomon when staging Katshaa! The Sound of the AK: A Play in Solidarity with the Heroic Struggle of the South African Masses. They sang of Solomon’s struggle, death, and retaliation for it:

Kulukhuni sekulusizi Nxa esegwetshwa obesilwela Noma kubi siyophindisela We Qhawe, Solomoni Hamba kahle Solomon! Hamba kahle Mahlangu Sowanqoba wonke, olaluoaoa Wonk’ amabhunu Nank’umkonto uzobagwaza Lala qhawe, nsizwa yomkonto.

In summary: Despite the sadness when the our hero warrior-activist Kalushi was sentenced, go well, Solomon!, for we will grab the Spear and retaliate against the Boers: Farewell our hero!

But it was another Song of Solomon, “‘Iyho uSolomon,” which gripped the imagination of the younger generation in 2015/2016. Much earlier, In 2010, “Iyho uSolomon” had been a runaway hit at the ANC general council meeting in Durban; one journalist suggested it had overlaid Jacob Zuma’s “Awuleth’ Umshini Wami” (Bring me my machine gun) as the ANC’s new struggle song. The words go:

Iyho uSolomon!

Isotsha lo Mkhonto We Sizwe!

Wa yo bulala amabhunu eAfrika!

Translated: “Oh Solomon / The soldier of Umkhonto we Sizwe / He killed the Boers in Africa.”

The song became almost an anthem of the #FeesMustFall students. It was, mused journalists Pontsho Pilane and Kwanele Sosibo in March 2016, “a rallying cry: a link to the defiance of a bygone era”. Kalushi, as social work professor Linda Harms Smith puts it, had “become the figure that students honour.” The song appears to have complex and diverse roots.

Several MK veterans reportedly are unaware of “Iyo uSolomon.” The ANC Youth League may well be the source; former League secretary-general Sihle Zikalala says, “This is a youth league song aimed at conscientizing young people … It is not a new song or an MK song but is about our young comrades celebrating and acknowledging” Kalushi. Some comrades at the online “Communist University” pondered its origins in 2011. Dominic Tweedie, who stood vigil in Trafalgar Square on the night Kalushi was hung, then helped many others build the Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College at Mazimbu, saw Kalushi’s memory as “an important part of my political life,” yet felt “the new song adds nothing to this legacy, but only exploits Solomon Mahlangu’s memory cheaply.” Others disagreed. Overall, the film, rather than the song, gives real depth to Kalushi’s life.

Today it is highly unlikely, if not entirely improbable, that one day some soul will make a movie “celebrating” South African President Jacob Zuma or his successor Cyril Ramaphosa: young martyrs are always less problematic than ageing politicians and tycoons with blemished records. Yet questions remain about the intersections between life and myth, legend and narrative, politics and culture, past and present. At the end of the day, Solomon’s story continues to inspire, not least among the youth of today.

This contemporary political and generational resonance should in theory have guaranteed a substantial reception. But the weak domestic box office underlines limited purchasing power of many social strata, together with promotion inhibition in commercial circles, notwithstanding government and other efforts to promote the film. The shift of a substantial number of people to online viewing should nudge produces to explore wider forms of accessibility.

The obvious but powerful thing is that Solomon was a foot soldier, with no fancy suits, no compromises, untainted by corruption; and, by all accounts, a disciplined member of the liberation movement. He is shown, following the meaning of his name, as a shepherd of people. Solomon Mahlangu and his life and times will always resonate with the South African public. Critics will argue about this or that aspect, but it is good to have this film, and to talk about it.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers