Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 254

June 27, 2018

The Football Griot

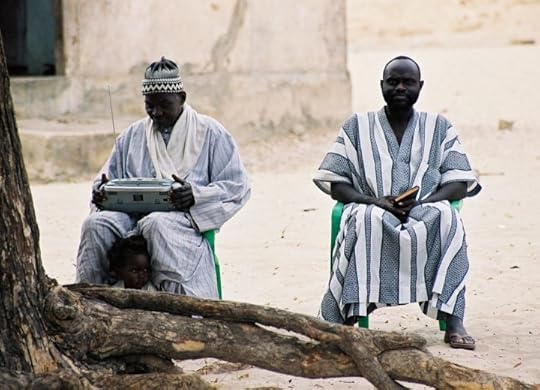

Image by Isabelle Chauvel.

In the early 1950s, a Senegalese radio announcer known as Allou developed a style of match reporting on the radio that delved deep into West African storytelling traditions. He drew on the styles of the griot���hereditary musicians who for generations have spoken the history of families and communities���to recount the exploits of these new heroes in real time. In one memorably tragic match, he recounted live as the player Iba Mar Diop scored a penalty kick at the last minute, winning the game for his team���only to collapse from a heart attack and die moments afterward. Radio journalists such as Allou gave audiences a way to experience and understand such dramatic moments by connecting them to broader cultural narratives about heroism and sacrifice.

Allou���s full name was Alassane Ndiaye. He was part of a distinguished Senegalese family. His uncle was Blaise Diagne, who had represented Senegal in the French National Assembly for decades, and was the father of the soccer star and later Senegalese national team coach Raoul Diagne. Another of his relatives, Lamine Gu��ye, was mayor of Dakar and later the first president of the Senegalese National Assembly. Ndiaye grew up on Gor��e, an island near Dakar. He attended university in Dakar and became a distinguished history teacher, and hosted a radio show about Senegalese history. Ndiaye had loved playing soccer as a child, and that is when he was given the nickname Allou, a shortened version of his first name, by his teammates.

Allou began his career as a sports commentator by accident. One day at the Parc Municipal des Sports in Dakar, he suddenly found the microphone thrust in front of him. It was just after World War II, and football was booming in Senegal. But there was only one journalist calling the games on the radio, a man named Pierre V��ran. Perhaps he was tired, or perhaps he wanted to play a trick on Ndiaye. ���I���m handing the microphone to my young colleague Allou,��� V��ran declared suddenly. As he later remembered, Allou had hesitated for a minute or two, ���as if drowning in an endless sea,��� and V��ran looked at him expectantly. Somehow, though, Allou found his voice and began to narrate the match. Unexpectedly, he had found a new calling.

From that moment on, he never stopped, and eventually became the most beloved soccer commentator of his generation in Senegal. Allou played a key role in the expanding popularity of the sport in his country. As was the case throughout the world during that period, media and soccer expanded together: the radio brought new fans, and the fans bought more radios. As historian Bocar Ly writes, Allou cut a striking figure along the side of the pitch with his microphone, always ���elegantly dressed.��� He started each match the same way: ���Thank you to the studio! Allou here, reporting from the Parc Municipal des Sports.��� Back

home, people gathered around the radio, ���ready to let themselves be seduced��� by his electrifying voice. Allou had to help listeners visualize what was happening and, like other radio announcers, developed a rich and evocative language that brought together detailed description of plays and moves with a larger, poetic celebration of the meaning of the game. Fans were ���transported into another world��� as Allou turned the narration of games into an opportunity to reflect on almost all aspects of human life. He infused his accounts of matches with rich historical, cultural, and philosophical references. There was, Ly notes, no ���lyric theme��� that he hadn���t at some point talked about in relation to soccer: ���Love, death, human destiny, nature���s charms and mysteries, the world and its abysses, grandeur, the beauty and nobility of sport, the power of God and his ineluctable decisions.��� Delving deep into Senegalese tradition, Allou created a universe of sound and reflection around each match.

Though Allou was well versed in tactical questions, Ly argues that a game of soccer for him was always much more than ���an abstract and narrow game of chess, a problem of applied tactics.��� It was an opportunity to create a work of verbal performance, a spectacle of vocal sound. He had an ���ample and easy eloquence,��� and ���an incomparable verbal richness and sumptuousness.��� He offered up a ���spontaneous profusion of images,��� and used the rhythm of his voice to communicate the drama and emotion of the match to those who could not see it. ���His voice, slow and suave when the game was calmly being played in the midfield,��� was ���amplified and fired up when the action got closer to the penalty area or when danger became imminent,��� so that those who listened on their radios felt all the emotions that ���constricted the hearts��� of those in the stadium. Allou���s live accounts of the games were ���prose poems,��� a ���poetry at once lyric and epic.��� In this, he was also teaching fans how to connect soccer to other aspects of their culture. His commentary gave fans new ways of thinking, and feeling, through a game.

���Faking��� for democracy

Alpha Conde, President of Guinea. Image by World Bank.

���Fake��� gets a bad rep these days and for good reasons. Fake news have been deployed effectively on social media–whether in Nigeria, Kenya or South Africa, as an effective strategy to undermine democracy���s very foundation. But what if�� ���fake��� not as a label of news one dislikes, but as a ���genre��� or a mode of operating on social media held the key to unlocking democratic debate, as the practice would suggest on the African continent, particularly in West Africa?

The radical transformation of the media landscape in Africa has led to the emergence of new forms of political humor as users take advantage of the possibility to generate their own content enabled by new technologies.�� One form of political satire seems to have particularly proliferated:�� political faking, and more specifically user-generated fake accounts that satirize prominent political figures, heads of state in particular, through impersonation.�� In Guinea, for instance, the ���fake��� account of president Alpha Conde, tweeting under the handle @_Prof_AlphaConde, has more than twice many followers as the actual president’s account.�� In Equatorial Guinea, 76-years-old Teodoro Obiang, who has been in power since 1979,�� does not have a Twitter account. Yet, he exists on Twitter through his satirical alter-ego, a ���fake��� account tweeting under @PresidentObiang, one of the country���s most avidly followed account.�� A ���fake��� account for Zimbabwe���s ex-ruler, 93-years-old Robert Mugabe is using satire to live out his myth of immortality and indomitable sexual appetite.�� Again, the account is widely followed.�� Whilst not unique to the African context (see Elisabetta Ferrari���s work on Italy for instance), the ���fake��� genre seems to dominate political satire on African Twitter is ways that are not seen outside of the continent.

Why has political faking taken on such vigor in countries such as Guinea or Equatorial Guinea?�� One explanation might lie in the prominence of pretense as a dominant organizing mode of political life in postcolonial contexts.�� As the Cameroonian scholar Achille Mbembe notes: ������ the postcolony is, par excellence, a hollow pretense, a regime of unreality (regime du simulacre).��� Creating a fake Twitter account may be a way of productively engaging the dominant form, turning it on its head as it were.���� The Guinean account is here an interesting example. Today, after two terms in power, Alpha Conde, the country���s first democratically elected president, is following a sadly too familiar pattern in African politics, gesturing that he will cling to power for a third term, changing the constitution to do so if need be. In this context, the president���s ���fake��� alter-ego @Prof_AlphaConde has been on a mission of late to use his/her/its scathing humor and unrelenting satire to denounce the shady maneuver.

But, what can be achieved through satire, and particularly satire that fully takes on, and invest the dominant fakeness?�� Clearly, political faking���s greatest strength is in mobilizing satire���s double-voiced-ness in order to reveal the true identity of the autocrat, as in the Guinea example.�� Faking becomes the means of calling the ���bluff;��� irony as a hallmark of sincerity.�� Still, whereas in the West, satire is typically understood as activist media and key to building a cohesive counter-discourse, in non-democratic postcolonial contexts, political satire has often been interpreted as either trivializing its message, and even as being tolerated by dictators in order to boost up their ���democratic��� credentials (���see, we are open to criticism, we even have political satirists?���) or worst, as joining in a fatalistically cynical exercise in laughing away daily oppression, with no hope for any coherent counter-public or activist movement.�� For Mbembe, for instance, all that political satire can achieve at best is to ���create potholes of indiscipline on which the commandement may stub its toe.��� Cameroon, where Mbembe is from, is governed by Paul Biya in or other form since 1975.

But Mbembe was writing that in the pre-digital era, when humor was professionally produced and centrally distributed.�� Today, digital technologies are changing the game, for both good and bad.�� Whilst, historically, vulgarity and crudeness have been humoristic devices using to ���tame��� autocratic power, social media norms, often set in the West, invite much more tame forms of humor.�� Explicit content is quickly shut down on Twitter.�� Even Mugabe���s ���fake��� account which largely plays on his image as a ���dirty old man��� exercises restraint.�� Yet, satire on social media also circulates much differently.�� And whilst most of the world still has to show it cares, ���fake��� accounts are operating outside of the confines of national conversations, a key difference with older forms of media. It is clear from talking to social media activists and humorists on the continent that part of the appeal of digital impersonation is a desire to inscribe what has tended to be a national conversation into a global movement towards democratic politics.�� And given that in digitally mediated politics, circulation is key, perhaps ���creating potholes��� is not a bad strategy after all.

June 26, 2018

Bishops, imams, sangomas, pastors and ending abuse

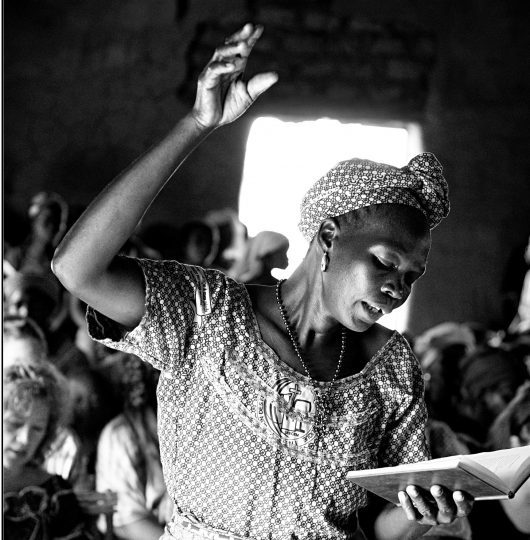

Image by Ewien van Bergeijk.

In the past decade, the role of religious leaders has been publicly challenged by human rights and international development organizations for supporting unrealistic views of gender relationships, family and societal models. Indeed, for centuries, particular interpretations of religious scriptures have been fuelling patriarchy and as a consequence sexual and gender based violence. The main question posed to these interpretations points to the fact that scriptures have been developed thousands of years ago as universal codes of conduct and morality and cannot be translated to our times without a careful reflexion. In other words, faith leaders in the twenty-first century can���t respond to sexual and gender based violence in their communities by simply reproducing perspectives from centuries ago.

Yet, in most countries of the global south ��� as well as in some of the most powerful economies the global north ��� religion and spirituality are integral parts of politics, economics and social life. On the African continent, faith doesn’t necessarily relate to religious institutions or set doctrines, but is deeply connected to day-to-day of individuals. The messages conveyed by bishops, imams, sangomas, pastors, help to shape gender roles and sexual practices, influence people���s choices on medical treatments, catalyze social conflicts and forge resilient responses to traumatic experiences of violence. According to a report from Pew Forum Research on Religion and Public Life, in 2009 an average of 86% (roughly nine in 10) people in sub-Saharan Africa declared that religion is��a very important��aspect of their lives.

For the past 6 years I���ve been studying the role of African faith leaders in contexts of social transformation and throughout the lives of those who follow them. In my recent research (2017-2019), I have been witnessing the work of African-based NGOs with gender equality aimed at faith leaders across southern African countries. This work consists in delivering workshops in which skills and knowledge on sexual and gender-based violence prevention can be replicated by faith leaders in their communities. As one would imagine, it���s not an easy job but faith leaders��� openness to the matter is greater than what most people would imagine.

Amongst faith leaders attending sexual and gender based violence prevention workshops last year, the majority recognised to have dealt with sexual and gender based violence in their communities and expressed that they would like to act to prevent or respond effectively to it. However, few admitted to speak up against this problem owing to the lack of support from their respective religious institutions, and, namely, their superiors or senior peers.

Here are some of the key findings of the research: 80% of faith leaders mentioned that they offered advice or counselling to either a victim or perpetrator of sexual and gender based violence; in 36% of these cases were about emotional abuse, 26% were related to rape and sexual assault, and 27%�� other kinds of physical violence. The average age of participants was 43 years old with 68% of participants being between 18 and 47 years old. 1% had no formal education, 6% Primary, 23% Secondary (complete or incomplete) and 70% University, college or more.

One male pastor, from a Pentecostal church in Pietermaritzburg in Kwazulu-Natal, responded on why he attended the meeting: ���We (Pastors) are quick to go to the bible to look for solutions to people���s problems, not actually knowing what really the problem is. I���ve been hearing about gender, but I didn���t know the depth of gender issues. When I saw this workshop I saw as a good opportunity to go and learn.��� Post-workshop, he added: ���We have to decolonise our messages because the messages brought to us before were about the salvation of humanity, or, that you have to pray so you don���t go to hell because you need to go to heaven. But our contexts have changed significantly and we need to watch what we preach to be relevant. How will Jesus Christ be relevant to the life of somebody that is raped and is not getting any help?���

In addition to that, male faith leaders admitted that the fear to engage in the struggle against sexual and gender based violence and equal rights is related to the fear of being ridiculed by other men or having their authority questioned. Similarly, female leaders were afraid of being labelled as ���feminists���, an expression used in derogatory way. At the same time, those who have been and speaking up against sexual and gender based violence, complain about the lack of networks of support either from religious or secular organisations. They also remarked the limited information available on how to respond and prevent such cases in their communities. This lack of information becomes even more problematic when they mention that churches are often the first place where victims look for help and try to find support and advice, coming mainly from leading figures. All this shows that we must go beyond the general notion of religion equating fundamentalism if we want to truly reach everyone in the quest for gender justice.

There have been significant advances in the last 20 years to make gender and gender inequalities visible in terms of the lives of women and girls in South Africa and across the African continent. It has also been throughout these past years that the role religious communities have been targeted as a player in the formation and entrenching of harmful social norms in the quest for gender equality. But this role can either be a force for positive social change or a barrier to the quest for gender equality and end of gender based violence and injustices. What I came to understand is that faith leaders are often looking at where their communities should go but seldom approaching their current struggles, and spend even less time looking at their own interaction with violence throughout life.

Indeed the strategy employed in the interventions that I have analysed acknowledges that some of the key drivers of gender inequalities and injustices are embedded in religious practice and thought. Yet, with evidence pointing that faith leaders are willing to make a positive contribution to current struggles of society, development agencies and human rights organizations must see religion and spirituality as collaborative agents in the quest for gender justice.

June 25, 2018

What Else Is There?

Images by Fati Abubakar.

From the day that Boko Haram decided to attack a prison gate in Maiduguri, Borno State, in North East Nigeria, there has been chaos. Boko Haram���literally meaning ���western education is forbidden������has been on a rampage for several years. This terrorist group has successfully destroyed every sector of public life in this region of Nigeria: the economy, through bomb blasts in the markets around Maiduguri; politics, through targeted killing of politicians; the education sector, through kidnappings of students and killing of teachers; and the monarchy and the dynasties, through the killing of traditional leaders. It is has attempted to erase all that it considers ���un-Islamic��� in its quest to rule.

The state is currently plagued by the turmoil and despair of this reign of terror. The narratives created for us, as a people, are death, devastation and destruction. We are stereotyped as perpetual victims. Indeed, the stories of sadness are true, but what else is out there? As a graduate student studying Public Health in Britain, I obsessively follow the news from back home. It is all the same. My hometown is on fire, literally and figuratively.

Indeed, when I returned home in 2015, Maiduguri was a town under fire but still very much going on with daily life. So, I picked up a camera, out of anger at the representation of the conflict in my community. I knew what I wanted to zoom in on: the resilience of my people. Years of mainstream media coverage had, as expected, focused on our worst times. The sadness. The dead bodies on the street. The destroyed buildings. The rape. The trauma.

But beyond the headlines, what is exactly happening? After the breaking news, what becomes of the widowed and the orphaned? How are people feeling, coping in this turmoil? I want to know. I also feel that the documentation of African stories by Africans is very important. We needed to capture present day realities of Africa from an array of African lenses.

In my case, Borno is not only losing its people but also its identity and cultures due to the mass displacement of communities. There are perils to that displacement, as we also have to preserve our heritage. I want to document and preserve social practices, festive events, daily tasks and knowledge. My way of doing so is through photography.

I documented everyday stories of my community for two years nonstop. I photographed everything from the impact of the insurgency on our town to the resilience of our people to the social groups within my community. Through visual storytelling I���m able to help people learn more about our cultures and traditions while at the same time archiving our present. Years from now, generations will want to know what happened.

But communities in Borno State are very unpredictable. There is always the threat of a suicide bomber coming to town and killing thousands. We see it happen often. The conditions in which I work are volatile and uncertain. There have cases of suicide bombers entering markets and crowded areas. We have had dozens of incidents in the past year. Despite all of this, I walk around every day photographing communities and taking portraits of people and interviewing them. It is important that people know of our stories of resilience.

I have had to suppress my own fear in order to continue this project. I am constantly being cautioned about the danger of working in a conflict zone, but I believe it is my role to help frame not only how we are perceived but also the true picture of our community. And what do I find? Fashionable youth girls dressed for Eid celebrations. Young men excited to finally start playing football games at the local stadium for the first time in eight years. A local musician singing his hit song for a group of excited graduates from the university that had never closed for a day despite being surrounded by conflict. A herder of cattle roaming across fields even as stories of theft of animals by terrorists abound. A smiling child at a camp oblivious to his surroundings. A wedding. A beautifully adorned bride being photographed as her husband���s friends insisted the photoshoot end because the bride has to be taken to her home before the curfew. A driver who takes thousands out of villages as bullets hit his car. A young man who decided to fight the insurgency.

Stories of bravery, courage, sheer strength and beauty are what I find when I see my community through the lens of resilience. The conflict is ongoing, the humanitarian crisis is daunting, our problems still exist. Yet, every day I marvel at how the human spirit is able to endure all this pain and find strength to wake up, get dressed and go to find a way to fight this insurgency or simply to just teach or to go school or to see a counsellor or to eat or to play for the local team.

Simple, everyday strength.

The lessons from Zimbabwe’s land reform for its neighbors

Harveste maize in Zimbabwe. Image by United Church.

There is a curious relationship between land, politics and elections in southern Africa. There is little doubt land, and land reform, continue to be emotive issues; this is unsurprising considering the intertwined legacies of dispossession, colonial rule, migrant labour, and white minority privilege in the region. However, for the casual observer it may seem that for post-liberation ruling parties, land reform mostly seems something best forgotten, only to be trotted out opportunistically every election cycle.

In South Africa, the removal of President Jacob Zuma (2009-2018) ahead of a 2019 general election triggered the land issue once more. In some ways, the ruling African National Congress���s willingness to discuss land reform may have to do with the challenge it faces for votes from the opposition Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF). At the end of February 2018, the EFF tabled a motion to amend the constitutional provision on land reform to allow for compulsory expropriation (i.e. without compensation). ANC MP���s then agreed to launch a review of the constitution.

The start of the process to change the country���s constitution and land has surprised many, considering the business-friendly aura of the country���s new president, Cyril Ramaphosa. Yet the term “compulsory acquisition” alone has set alarm bells ringing in some quarters that South Africa is about to embark on a land reform program to rival the one initiated by Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe.

AfriForum, a nearly 200,000-member-strong Afrikaner rights group which has emerged as the leading anti-land reform organization, recently embarked on a trip to the United States to highlight the issue of compulsory acquisition and white farming woes. Its aim was to conflate the taking of the land to an imagined agenda of white genocide. This is an issue which was present in Zimbabwe during the early 2000s, when fears of genocide and ethnic cleansing were touted by local and international media outlets.

Much of the scholarship of Zimbabwe���s land reform since 2000 has been deeply divided. On the one hand, many critics paint it as chaotic, disastrous and bloody, while claiming the social and economic plights the country has suffered subsequently, as symptomatic. On the other hand, many supporters of the reforms have tried to show the successes, the gains by small-scale farmers and the changes in people���s lives as a result of getting land.

At this early stage, there is little to suggest that South Africa will follow the same path as Zimbabwe. And, despite the largely negative press over the years, recent reports have sought to highlight some of the more positive aspects of Zimbabwe���s land reform and agricultural growth. It has been reported that 2.2 million tonnes of maize was produced in Zimbabwe in 2017, the largest crop in more than two decades. This bump in the harvest has been ascribed to the success of ���command agriculture,��� a program initiated the 2016-2017 season. Under this scheme, targeted farmers who had access to water would agree to put a minimum of 200 hectares of land under maize and commit 5 tonnes per hectare into repaying loans and input costs. In return, the farmers would receive advances and subsidised inputs to the tune of US$250,000 each. A private company, Sakunda Holdings, was awarded the tender to fund and manage this program.

The apparent gains made in maize production due to command agriculture saw the government of Zimbabwe expand the program to include tobacco, wheat, soya beans, livestock, fisheries and wildlife production earlier this year.

However, many commentators have raised concerns with funding and reportage of command agriculture. Firstly, while the estimated figures put the maize yield at over 2 million tonnes in 2017, it is hard to get officially verified figures. And these estimates seem to have become accepted as writ, even appearing on the United States Department of Agriculture data sets. Secondly, despite these apparent gains, the Zimbabwean government was still importing maize at the end of 2017, in contravention of their own ban on the importation of maize made in June 2017. Furthermore, this season���s production (2017/18) is only projected at 750,000 tonnes, in part due to poor and inconsistent rains. But the poor projections of this season, and the low figures for the 2015-2016 season (only 520 tonnes) raise concerns of the accuracy of the 2016-2017 season figures. Thirdly, the subsidy model of command agriculture is highly problematic. Under the scheme, famers were to be paid $390 per ton, more than double the price in regional markets (there is a story here too on the dual economy and ���US dollar rates��� and ���Zimbabwean dollar rates���).

The IMF and World Bank have warned Zimbabwe that command agriculture is negatively impacting domestic debt, which is growing rapidly. This has significant implications for many other sectors of the economy. Furthermore, there are concerns of abuses of the system, whereby farmers abuse the input and subsidy loans, lack of transparency in the system and Sakunda���s ties to the ruling elite and its ability to manage this program. Crucially for the veracity of the production figures, there are a number of issues here too. Millers complained that they could not afford maize at $390 per ton. So, government agreed to sell them maize at $242.40 per ton, a loss of 147.50 per ton. Reports of millers getting their allocation of maize, driving it straight to a Grain Marketing Board depot and reselling to the state are not surprising.

As agricultural ecologist Ian Scoones has observed, subsidies are always political. Throughout Zimbabwe���s history farmers have received various forms of price-support and subsidy. During the liberation war, the minority government sought to keep white farmers on the land, as a buffer to guerrilla infiltration. Similarly, the ruling party has initiated command agriculture to keep farmers on the land. This is particularly pertinent now with the change in leadership and a credible election to manage later this year. The long-term costs of this move are unclear, as are the recent production figures.

With elections at the end of July 2018, the Zimbabwean government is at pains to ensure its continued support in farming areas, which has resulted in the formation of an expensive, hard-to-police and problematic subsidy program to ensure that support remains intact. Countries in the region, like South Africa, embarking on land reform would do well to ensure similar mistakes are avoided, and focus on making agriculture work, rather than creating a new class of landowners intricately tied to the State who hold power over both the production of food and the rural votes.

Ghetto defendants

Paul Pogba.

So far, so so: France���s journey to the World Cup was not without worry, and pre-World Cup friendlies were all but reassuring. France���s opening game against Australia was an assault on the nerves but ended in video-assisted victory. [The next game, a��1-0 victory over Peru, was equally unconvincing–Editor]. The best thing to come out of this may well be the fact that Paul Pogba���s diary has replaced in the media Antoine Griezmann���s unbelievably tone-deaf docudrama La Decisi��n, in which he wasted half an hour of life to announce that he would stay at Atl��tico Madrid. Team France lives under the sign of video: a sign of the times���constant contact has become a staple of modern sports culture and communication. Or lack thereof.

Indeed, it isn���t like Pogba had anything interesting to say in his diary. ���Tough game;��� ���tough adversaries;��� ���we did what had to be done���: Pogba practices a 21st century athletic Esperanto designed to occupy the airwaves with more air, to occupy the news cycle without offending anyone. Team France���s studied dullness is manager Didier Deschamps��� trademark and it has been devised to avoid repeating the shit show that were the early 2010s. When Deschamps became France���s manager in 2012, he infamously declared ���players can no longer make mistakes.��� Mistakes like , when France lost all three group games, decided to out-French itself by going on strike in the middle of the tournament, and eventually imploded following a locker room spat brought by French sports newspaper L���Equipe to the level of a national quarrel. The following years were equally laden with scandal: stories of locker room bullying between players, underage sex parties, sex tapes and blackmail all provided opportunities for every French politician and pundit to divine in every French player���s actions a diagnosis of the state of social relations in the Republic. Deschamps demanded the end of public mistakes, in the process drawing the spotlight away from the institutional scandal that had shaken the tenure of Laurent Blanc, his predecessor at the head of the team: 98 World champion and former PSG coach was caught on tape in 2011 discussing with representatives of France���s football authorities the possibility of creating quotas in French football to limit the number of dual citizen, and evoking the prototypically ���big, strong, powerful��� players churned out by French academies. ���What is there that is currently big, strong, powerful? The blacks. That’s the way it is. It’s a current fact. God knows that in the training centers and football schools there are loads of them,��� he added. Blanc was eventually cleared of discriminatory practices, but the row was a symptom of the toxicity of French public discourse and habits in relation to football. After 2010, politicians had demanded that heads roll, and the players singled out for public opprobrium���Evra, Rib��ry, Benz��ma, Nasri, M��nez, to name the most obvious���were systematically reduced by journalists and politicians alike to their social and racial background: these were banlieue kids, most of them of African descent, with dubious loyalty to France. These disrespectful thugs had taken over the French team���next step, the whole country. It wouldn���t be like we hadn���t been warned. Players were put on the stand, summoned to demonstrate that their existence was compatible with a vision of the team as the epitome of French virtues.

And so rather than treating the problems, Deschamps mostly cured the symptoms: no more mistakes, no more outbursts; no more denunciation of the intrinsic racism of French football authorities and organizations; no more public complaints about the manager���s choices, no more rejoinders to casual classism and racism. Deschamps��� team is squeaky clean; his players are polite and geniuses at what the French call langue de bois���wooden tongue: the political art of saying nothing well. Kylian Mbapp��, France���s 19 year-old prodigy, thus regularly collects praise from all for being modest, confident, articulate. Oh yes. Articulate���the international term of endearment for respectable negroes. This is not a commentary on Mbapp��, but rather on the evolution of media and political treatment of the French national team in France, and in order to better understand where we are now, it is������ useful to look back even further to 2006. That year, France played against Italy in what was perhaps the most dramatic World Cup final ever. If the highlights will forever boil the game down to a Panenka, a headbutt and a missed penalty, there was much more at stake in the conclusion of France���s journey. The 1998 victory had made football a respectable topic of discussion for intellectuals and polticians alike; 2006 played a central role in the liberation and normalization of a racialized discourse until then mostly confined to the far-right gutters of French political life.

This is July 7th 2006. We made it. We���re in the final. Us, France, our Bleus, our boys, Team France. In the run up to the tournament, coach Raymond Domenech and his team faced harsh criticism for their unconvincing results: commentators from newsdesks to bar counters thought them too old, too slow, too blas��, too tired. Back in 2002 France was considered the best team in the world, and they went home in shame, having scored exactly no goal. The 2006 team, built around aging heroes of 98 like Zinedine Zidane and Lilian Thuram, was washed up and would shame us worse. Like most people in 2006, I did not expect much from France. They struggled through the group stage to meet Spain, a young team among the favorites, in the round of 16. That game was perhaps the most iconic: Spain scored on a penalty kick, and Rib��ry���then, ironically, France���s great white hope, rather than the semi-pariah he���s since become���scored his first ever goal for France in stunning fashion, dribbling his way around Casillas to go fly a plane around the stadium. Watch Patrick Vieira���s giddy stomp after scoring against Spain; watch Zidane���s cocky strut after the third goal, a master class taught to all of Spain���s press and to his own Real Madrid teammates. The two games after this one���the magnificent quarter-final against Brazil, the grueling semi-final against Portugal���felt like increasingly unavoidable va te faire foutre to all, a meeting with destiny. The 98 winners had also had to face hostility from the French press; but by 2006 football was politics. The shift from the sainted 1998 team to the once cursed and now redeemed 2006 team carried portents of France���s descent into the racial crisis it now shamelessly wallows in, ten years on.

What a difference victory makes: when World Cup 2006 started, when so few in France could imagine them coming out of the group stage, some let it all out. Leading the charge, ���saying out loud what others think,�����old fascist Jean-Marie Le Pen took it upon himself to officially announce our views on the matter: according to him, France are not only playing badly, they���re playing blackly, and we cannot possibly identify with this team, ���maybe because the manager has exaggerated the proportion of colored players on the team.��� Le Pen also took the opportunity to complain again about the players not singing the national anthem. We���ve heard this before, Le Pen having said similar things in 1998 and 2002. By 2006, though, what was once the oft ridiculed cause c��l��bre of the far-right drifted into mainstream political discourse.

What Le Pen was saying out loud, former liberal philosopher turned rabid conservative pundit Alain Finkielkraut was now also saying, though in the pages of Ha���aretz. ���People say the French national team is admired by all because it is ���black-blanc-beur�����[“black-white-Arab” – a reference to the colors on France’s tricolor flag and a symbol of the multiculturalism of French society – D.M.]. Actually, the national team today is black-black-black, which arouses ridicule throughout Europe.��� For Le Pen as for Finkielkraut, the incontrovertible blackness of the 2006 French team���more than half of the players, oh my���was the real problem. In the aftermath of his ugly comment, Finkielkraut was invited on every other French news outlet to explain himself. In interview after interview he shared variations of a cute little story. We���d all completely missed the context: ���He [Finkielkraut���s father] would see the players on team France���Kissovski, Kopa, a.k.a. Kopachevski, Piantoni, etc.���and joke around: “are there any Frenchmen on this team?��� By that he meant natives of France. It was an innocent joke, harmless laughter whose echo I tried to describe in this text [the Ha���aretz interview].��� It was a joke the whole time, and really Haaretz���s fault for muddling his pristine thought. Finkielkraut���s anecdote does point to a known truth about France: the best national sides the country ever had to offer were always made of immigrants, sons of immigrants and Frenchmen of Caribbean descent. Finkielkraut named players from the 1958 France team, the first to reach a World Cup semi-final and numbering France���s first bona fida international football stars, including Real Madrid fixture Raymond Kopa. It featured the first international stars of French football: sons of Polish and Italian miners���Algerian stars Zitouni and Mekhloufi defiantly going AWOL the previous year to join the team put together by the Algerian National Liberation Front. The 1980s team, twice World Cup semi-finalists and European champions in 1984, featured the Martinican G��rard Janvion and the Guadeloupean Marius Tr��sor; Michel Platini, Bruno Bellone, Patrick Battiston, Jean-Marc Ferreri, all sons of Italian immigrants; Luis Fernandez and Manuel Amoros sons of Spaniards; Jean Tigana was born in Bamako, Mali, and Jos�� Tour�����s father Bako had played for the Malian national team. When asked to comment on the kerfuffle in an interview for the French newspaper Lib��ration, manager Raymond Domenech���himself the son of a Republican Loyalist from Catalonia who sought refuge in France after the Spanish Civil War���had this to say: “As a kid, I lived in what we would now call a bad neighborhood in Lyons. It had a loaded name: ���the United States.��� There was just one family of French origin there, just one. It was a permanent mix. No one was black there; that���s an expression I have never used. There were Congolese, Ivorians, Malians, yes, but no blacks. Others came from North Africa, or from Spain. So that���s how we played. We���d have our own little World Cups […].��� No talk of race, then, but talk of places, the places parents came from and are still attached to, the sports loyalties that remain even after all, in a country that has drawn much of its manpower from European and African immigrants for a century and a half.

In France, as in most football-playing countries outside of the US, professional players tend to have more in common socially than they do racially: football is the social elevator and has been a narrow path out of the mines, the factories, the mills. Football develops particularly in industrial areas and banlieues because these are where the working class���whether native or immigrant���lives. Football is a quintessentially working class professional prospect: it is physical labor of a rare sort in that it appears to reward excellence exponentially. Competition is ruthless, the system is crass and exploitative, but it constitutes a social ladder more concrete and radical than the meritocratic fables bandied by our rulers and teachers. This is a truth as old as professional football, which tore the sport away from public school elites and put it into the feet of the working class. At some level, because anyone can and does judge on performance whether or not players ���deserve��� their place in the sport���s elite, football seems a more honest organization than social hierarchy. The aristocrats of football earn their place there without exploiting anyone and only remain on top as long as they can maintain themselves there: though they can���t lament it out loud, this doesn���t sit well with them. Good thing they have racism to fall back on.

Neither Le Pen nor Finkielkraut had anything to say of any interest about class, economic or social inequality and hierarchies. All that mattered and still matters to them is cultural and racial difference, and opportunities to present it as the most urgent problem to face the country. Le Pen and Finkielkraut knew full well what has long been known in the US, and now become a commonplace of France���s toxic TV landscape and media sphere: you can get away with saying anything about race and culture with the right amount of conditionals and caveats, and everybody loves a polemic. World Cup 2006, then, gave them an opportunity to suggest that the minorities of 21st century France were in fact less compatible with the Republic than their 20th century predecessors, and anyone could see why. Hell: we���d all seen why.

A month before the 2002 World Cup, Le Pen had shockingly reached the second round of the presidential elections only to lose in a landslide to Jacques Chirac, the perennial mainstream right wing candidate. In October 2005, two banlieue teenagers, Zyed Benna and Bouna Traor��, died on their way home from football practice, electrocuted as they were seeking refuge from police in a power substation. Outrage over the incident was subsequently aggravated by reckless police action and by the inflammatory comments of then Minister of the Interior Nicolas Sarkozy: riots spread from their home of Clichy sous Bois to banlieues around the country, leading the government to declare a state of emergency for the first time since the Algerian war. Already campaigning for the upcoming 2007 presidential election, Sarkozy was following a classic, Thatcherite tactic in using tough talk and recycling Le Pen���s ideas while clamoring not to share his ideology. In turn, Finkielkraut couldn���t possibly admit that he agreed with the notorious anti-Semite Le Pen, but this was precisely the kind of conversation that might keep him in the spotlight, so the good philosopher went high brow: he offered that his comment were only meant to expose France���s ���post-colonial privilege.��� By that, he did not mean so-called ���Fran��afrique������the network of economic and military alliances built by de Gaulle with former French colonies in Africa in the immediate aftermath of decolonization. No, for Finkielkraut, the presence of players of African descent on the team testified to the continuation of ugly, dated colonial practices transposed to the realm of football; a sports impressment of sorts. Rather than limit themselves to French players, he wisely elaborated, French football authorities tap into the human riches of the dark continent. Of course, Finkielkraut was well aware that all members of the French team are French citizens. Some French people are less French than others.

Case in point: black people. They are not native to French lands, Finkielkraut wisely suggested, and in some cases straight up blurted out. Nothing racist there, just common sense! An understanding of Frenchness rooted in a national historical romance based on strategic forgetting and simplistic straight lines. In this grand narrative, our ancestors are the Gauls, proud moustachioed barbarians who made France by mixing with Romans in a territory supposedly defined by ���natural boundaries���: even though the current borders of continental France are arguably less than a century old. This, of course, is not to mention France���s oversea territories, which rarely if ever enter this narrative, even though the so-called ���old colonies������Martinique and Guadeloupe���have been French longer than, say, Savoie. In this vision of French history, black French people are either accidents, absent, bit players, or made virtually colorless, through the potent whitewashing magic of the Republic���s colorblindness. My high school teacher friends tell me things have changed: in my day, though, we might read the odd C��saire poem in class, but we never learned about Alexandre Dumas���s Haitian background. We certainly never learned how the Haitian Revolution impacted the French one, or how black representatives sat next to Danton and Robespierre. Blacks fit in the traditional French historical narrative only as anomalies. Athletes, of course, are acceptable since, as Fanon infamously argued, in French culture ���the Negro is only biological.��� Acceptable, that is as long as they knew their place and kept quiet.

Then came Lilian Thuram. Asked about Le Pen���s comments in the aftermath of France���s stunning round of 16 victory over Spain, the left back retorted: ���Le Pen doesn���t seem to be aware that there are French people that are black, blonde, brunette. He has been running for president for years but he does not know French history.��� More accurately, Le Pen knows a very specific version of French history, one that takes only what it wants, gleefully steps over the paradoxes at the heart of France���s national identity, and which I would argue is very much embodied in the French Revolution: an event simultaneously nationalist and cosmopolitan, stamped both by the Enlightenment���s commitment to human rights and its role in the rise of racial thinking. The grand narrative of glorious France demands willful ignorance of the complexities and shadows of France���s past. Think of the dissonance in growing up trying to reconcile France���s values with a part of history you know to be French, but which you���ve mostly known to be yours: try being French West Indian. As a child, I remember that my mother, who generally did not care one bit about football, would nevertheless stop to let us know: ���Janvion, he���s from Martinique! Tr��sor, Sonor, they���re from Guadeloupe.��� Because French West Indians are French on their own, in their little corner of the Earth, in spite of France, as it were, since their skin color so often seems to void their passport, they traditionally take West Indian presence on the national team as a point of pride, an invisible and silent revenge. Le Pen and Finkielkraut feared that the mere presence of dark natives on the team might lead the country to recognize the debt it owes its second-class citizens, in the present and in the past, for sending them out as cannon fodder on the frontlines, down in mines, and in stadiums all alike.

Thuram ended his response to Le Pen with a peculiar sentence: ���By the way, I am not black.��� This quote has followed Thuram ever since. On the face of it, and from the other side of the Atlantic, it may seem a rather callous call to respectability politics, echoing uneasily the infamous words of Langston Hughes���s poet friend who wanted ���to be a poet���not a Negro poet.��� Thuram says he is a French player, not a black player���yet contrary to Hughes���s unnamed friend (psst: Countee Cullen), no one can imagine Thuram actually ���wants to be white.��� As a player and in years since his retirement, he has been a steady and forceful voice for West Indian art, culture and history. In claiming the colorblind language of the French Republic, Thuram was rather efficiently pointing to the utter hypocrisy of the likes of Finkielkraut���whom he called out elsewhere���rather than Le Pen, those whose racism came under the guise of liberal reflection, glossed in a veneer of respectability. Finkielkraut knew it well, who resorted to schoolyard ad hominem attacks in response to Thuram���s critiques: on at least one occasion, the petty philosopher mocked Thuram ���who, now that he wears glasses, has become the master in non-thought for much of the media class, the teacher, the billionaire proctor of politically correct thinking.��� Subtle.

But maybe he was on to something: sight, by way of representation and visibility, was paramount here. In the aftermath of the 2005 riots, President Jacques Chirac had highlighted the importance of representation when he insisted that there should be more French people of color on television. This injunction that was quickly followed by the announcement a few months before the World Cup that TF1, France���s foremost TV channel, would soon have in Harry Roselmack France���s first black evening news anchorman. In this context, the supposed overrepresentation of non-whites in team France revealed nothing more than their overall invisibility in French society. What was shocking was not so much that there were so many black people on the team, but that you saw so few in every other public institution. France���s record of abuse against people of African descent might warrant some animosity; yet, hostile reactions have really been benign along the years. In fact, the most surprising may be that people of African descent might feel French at all. But here we are, watching ourselves defending France on fields around the world, like we���ve always done.

Representation���or lack thereof���remains a surface matter. Much like football itself and other forms of entertainments, it is a distraction that matters, merely the symptom of a much deeper problem. Attending to the symptom does not necessarily begin to solve its causes, but the effort is not meaningless either. Chirac understood well what could potentially be gained in such an effort, and in maintaining it as a distraction. Now that discussions of race, culture and religion are omnipresent in French media and public discourse, French players all but entirely abstain from participating in it, opting instead to avoid controversy at all costs. This goes even for Patrice Evra. The once and future king of burns, now in semi-retirement at West Ham, is these days mostly known for his ���I love this game��� Youtube videos, the latest installment of which features a cameo of his bathtub friend Ducky Ducky. Times have changed. But if the French now have regular, public discussions about race���however awkwardly or appallingly���we owe it in no small part to the loudmouth defenders that have graced the national team���s ranks.

This piece echoes in spots an article I wrote from M��lanine on the eve of the final itself in 2006, dusted up a bit. In the years since, Laurent Dubois has written eloquently about these topics in Soccer Empire: The World Cup and the Future of France.

That one time Zambia nearly qualified for the World Cup

Zambia is not at the 2018 World Cup in Russia, having finished a distant second behind group winners Nigeria in the qualifiers. In fact, the only time the country had a realistic chance of making it to the World Cup was in 1993 during the qualifiers for USA 94, when the country missed qualification by the skin of their teeth and the officiating of one Jean-Fidele Diramba.

1993 will forever be known as the year Zambia suffered her worst footballing tragedy. On April 27, 1993, the plane carrying the Zambia National team to a World Cup qualifying match against Senegal, crashed off the coast of Gabon killing all on board including players, officials and crew. Once the mourning period was over, Zambia���s rebuilding efforts had seen its new team defy odds and top its World Cup qualifying group with only one game to go.

Zambia dared dream. A fairy-tale run to the World Cup was on the cards. Surely this was Zambia���s year.

The only team standing in Zambia���s way was Morocco. And even then, Zambia had cause to be optimistic having beaten Morocco 2-1 when the sides had earlier met in Lusaka. The stage was set and hopes were high going into the decider in Morocco with Zambia only needing to avoid defeat in order to seal a maiden World Cup appearance.

Prior to Zambia taking the field, local media in Zambia had expressed concern regarding the choice of match official. They noted Jean-Fidele Diramba tasked with officiating the match was Gabonese and at the time there were all manner of conspiracy theories surrounding the plane crash that killed the Zambia National Soccer team, with relations between Zambia and Gabon strained.

But then football, as Sir Alex Ferguson once observed, can kick you in the teeth when you least expect it. Zambia lost the match, thanks to a thumping header from Abdeslam Laghrissi in the 62th minute.

Back home in Zambia however, all the talk was about the shocking officiating by Diramba. On the Tuesday following the match, thousands marched to the Football Association in Lusaka to demand that Zambia petition FIFA for a rematch, a petition that depending on who you believe was never actually delivered.

The name ���Diramba��� has since acquired pantomime villain status in Zambia. When I was in primary school, our local football referee was called ���Diramba.��� To this day there is a smattering of ���Dirambas��� officiating at various levels of the Zambian game.

Perhaps that is one of the reasons Zambians might not support Morocco at the on-going World Cup [Morocco has since between knocked out of the 2018 World Cup in Russia after losing their first two of three group matches���Ed.]. There is also the added spice that Morocco are currently managed by Herve Renard, the Frenchman who masterminded Zambia���s Africa Cup triumph in 2012, in Gabon. It clearly isn���t the first time when Zambia���s loss has been Morocco���s gain.

The only Zambian to take the field in Russia, is referee Janny Sikazwe. Here is to hoping he doesn���t turn out into a Diramba.

Uganda���a culture that puts women at risk of great violence

Still from 'Kyenvu,' a film by Kemiyondo Coutinho.

Kemiyondo Coutinho, a young Ugandan actress raised in Swaziland, began creating her own roles with ���Jabulile,��� a play which she wrote and performed in South Africa and the United States. ���Jabulile��� took on the concerns of Swazi women traders, while Coutinho���s second theatrical offering ���Kawuna: You���re it��� addressed the prevalence of HIV/AIDS among Ugandan women. Her latest work, and first short film, ���Kyenvu,��� about rape and set in Kampala, cements Kemiyondo���s interest in illuminating the experiences of African women.

When Kemiyondo returned to live in Kampala in 2016, she knew only a few people working in film locally. This did not stop her from writing, producing, directing and starring in ���Kyenvu,��� with an entirely Ugandan cast. The 20-minute short touches on issues of identity and colorism, but most importantly rape culture as it is lived in Uganda���s vibrant capital Kampala.

Kyenvu begins charmingly, with a taxi scene (a small bus or matatu) that is familiar to anyone who has traveled around Kampala via public transportation. Like the unnamed main character Kemiyondo plays, I do not speak Luganda, the main language spoken in Kampala and central Uganda, so the taxi passengers��� taunts struck me as amusing and accurate.�� ���What has she got over us? Light color? Turn her black and see what she looks like.���

Ugandan society is deeply stratified by class, and public transport remains a last bastion in which the privilege of the western-educated abaana wa���bazungu may not apply. (The latter phrase literally means ���children of white people��� but is used to refer to English-speaking, westernised, young Ugandans). When another passenger stops the taxi conductor from overcharging Kyenvu, we assume it is a love story made for contemporary Africa.

Kyenvu is initially resistant to his advances, but she is eventually won over by his daily gifts. The ubiquitous trope of a woman refusing romantic advances until she is persuaded otherwise, has done much to devalue the idea that women mean ���no��� when they say it.

The film then takes a dark and unexpected turn when the main character is raped as she is waiting to meet her taxi liaison for their first date.

In Uganda, as is the case elsewhere, sexual violence is an urgent conversation, with ���defilement��� (the unfortunate name given to the sexual assault of minors in the Penal Code) the most commonly reported crime, accounting for half of serious crime reports in 2016. Thirteen percent of Ugandan women report having experienced sexual violence in the past 12 months. Fifty-six percent of Ugandan women will experience physical violence in their lifetimes.�� These statistics from the 2016 Uganda Household Survey came into sharp relief last year when at least 27 women were found raped and strangled to death in Wakiso district, close to the Kampala metropolitan area. The police have alternatively blamed domestic violence, unemployment, drug abuse, criminal gangs and land conflict. Others have suggested witchcraft, political motives and infighting among the country���s security forces for the violence.

In a country where confidence in a corrupt, underfunded and politicized police force nears zero, rumors and conspiracy find fertile ground. It is easier for police to call the victims sex workers, and for the Minister of Internal Affairs to suggest the illuminati is responsible, than to admit that thanks to patriarchy, Ugandan women���s lives are simply worth less. Ministers who blame mini-skirts for sexual violence, parliamentary MPs like Onesmus Twinamatsiko who happily comment on television that ���as a man, you need to discipline your wife. You need to touch her a bit, you tackle her, beat her somehow to really streamline her,��� are part of a culture that puts women at risk of great violence. The message is that women are at fault for the violence visited upon them, and those who hurt women face little or no consequence for their actions. And while it is gruesome serial killings that make front page news, it is easy to forget that there is an epidemic of sexual violence against Ugandan women and girls, most frequently committed by attackers known to the victim.

In Kyenvu, the rape scene comes seemingly out of leftfield (nowhere in the film���s promotion is there a warning). It is preceded by a clothing montage in which the main character eventually selects a shirt with the word ���Feminist��� emblazoned across it, and a yellow mini skirt. In the aftermath of the rape the protagonist states ���a wardrobe choice changed my life.��� Our formerly-intrepid protagonist with her feminist t-shirt is punished for her refusal to be dictated-to by a patriarchal society. There is little meaning to be gained from her violent assault, other than the enlightenment of her hapless date who comes to find her in the shower after the rape. She goes from mocking the idea that women need to be saved in the film���s opening scenes, to wishing she had a ���Batman or Superman or anyone��� to save her. We get no counter to the victim-blaming narratives embedded in the plot. If you went into the film thinking that women should dress more modestly to avoid violence, you would find little in the narrative to dissuade you. We know that women are most likely to be assaulted by men they know, yet Kyenvu leans into the idea that rape is something that happens when a stranger jumps out of the bush.

Kemiyondo told me, via email, she was compelled to write this film in response to stories of violence and harassment around her. Following the tabling of the 2014 Anti-Pornography Bill, aka the ���Anti-Miniskirt Bill,��� men publicly assaulted women in Kampala, while some MP���s made misogynistic statements in parliament. ���I have always created art because I want to reflect society back at itself. If you are a Ugandan or not, this is your story, if you are a woman or not, this is your story. What you do with the image facing up at you is completely and totally up to you.���

Art and media are not simply a mirror on society, they tell us how and what to think. I believe that Kemiyondo knows this, which is why she has chosen to include a panel discussion following screenings of the film in Uganda. I wish that instead of simply reflecting, the narrative of Kyenvu was also used to interrogate and agitate for ending violence against women. If we are to change minds about who is at fault for Uganda���s endemic violence against women, Kyenvu is unlikely to do it.

June 22, 2018

Soul Brother Krishna

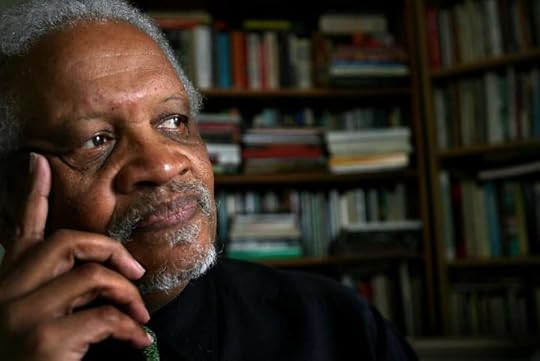

Image Credit: Mark Costantini

The Nuyorican Cafe on Manhattan���s Lower East Side has shown all the plays in Ishmael Reed���s 2009 Dalkey Archive Press collection The Plays: Savage Wilds (in 1991), Preacher and the Rapper (in 1994), The C Above C Above High C (in 1997), Hubba City (in 1996), Mother Hubbard (in 1998), and Body Parts: A Serious Comedy (in 2007). The Final Version also appeared at the Cafe (in 2014). His latest, Life Among The Aryans, is being staged there now as well.

The Poets Cafe, located, since the Seventies, in the Lower East Side, is an appropriate venue for Reed���s irreverent and penetrating works on race. The Cafe has resisted the flood of private capital and cultural dilution which have transformed the surrounding blocks into an archipelago of open-air brunch spots. It has done so with a fidelity to its original vision as a home for marginalized voices, even as New York squeezes out its Puerto Rican and African-American populations.

Life Among The Aryans, set in the near future in the southern town of Whoop-And-Holler, unfolds after the Presidency of P.P. Spanky, a reactionary reality-show host. A Jewish progressive has since been elected, and the new President announces reparations payments for all African-Americans. This outrages John Shaw, an unemployed White Supremacist (played by Frank Martin), but his ragtag outfit struggles to come up with a coherent response. First, his mentor, Leader Matthew (played by Timothy Mullins) skips town with the funds for the revolution. Then, his wife, Stella (played by Lisa Pakulski), and her friend Barbara (played by Jennifer Glassgow), undergo an experimental transracial procedure to become Black. They collect reparation monies and vacation overseas. Eventually Shaw must reconcile his racial fantasies with his isolated reality.

Reversals fill the play. John Shaw, who dreams of overthrowing the ���Zionist-occupied government,��� is Jewish. And when Doris Johnson, an African-American laborer played by Malika Iman, files for her reparations check, she is turned away. She doesn���t have the right documents.

Another twist is that the racist White Lightning Network has a South Asian anchor. The role is small���the anchor, played by Monisha Shiva, appears three times���but her narrative frames the play. She conveys, through her physical composure and exaggerated facial expressions, an intensity, that, exceeding that of the propagandist, enters the realm of the true-believer.

In his new novel, Conjugating Hindi (Dalkey Archive Press, 2018), Reed continues to explores the phenomena of South Asians on the Far-Right. The story centers around a series of debates between Professor Peter ���Boa��� Bowman, an African-American Professor of English at Woodrow Wilson Community College, and Shashi Paramara, a ���right-wing intellectual��� and Christian-Indian who makes propaganda films. [Paramara is recognizable as a send-up of filmmaker and writer Dinesh D���Souza.]

Parama and Bowman first debate the merits of chattel slavery for conservative crowds. Bowman plays the side-man. Then an international row breaks out when Siraj ud-Daulah, the firecracker Indian Prime Minister, presses Britain on allegations that Lord Mountbatten, former Viceroy of India, sexually abused Indian children in the 1940s. Global trade suffers; rumors of a looming war bloom. Indians begin to be hunted in America after the media blames India for a plane crash. At a debate, several Whites ���pummel��� Parama. Bowman tries to protect him but is thrown to the floor.

���The Fugitive Indian Law was being debated in Congress,��� Bowman says. Indians hide out in Arab shops wearing ���I am not an Indian��� shirts. Paramara tries to pass as Black to move through Oakland. He shows up at Bowman���s house, asking to be hidden. ���Shashi was doing a bad imitation of a hip-hop walk like the kind he���d seen on MTV.��� Bowman takes him in.

Bowman, an expert on the intellectual dispute between Monroe Trotter and Booker T. Washington, has been studying Hindi and reading Indian history. When, in his basement, he tries to get to the root of Paramara���s Eurocentricity, a second set of debates begin.

Bowman: ���Take Vyasa���s Mahabharata and Valmiki Muni���s Ramayana, works that were written in the eighth and twelfth centuries. Hundreds of years before Shakespeare.���

Paramara: ���Two long boring video games on paper all about royals engaged in endless warfare��� Plots that appeal to children without the sophisticated and complex plots in a play by Shakespeare or Marlowe��� Just adds to the screed of superstitions that are crippling the Indian consciousness.���

Bowman: ���Superstitions? Witches and sorcerers and soothsayers appear in Shakespeare. Hardly are his texts based on reason or enlightenment. There are enough ghosts in Shakespeare���s plays to organize their own acting company. Moreover, Shakespeare, a country boy, probably subscribed to these superstitions.���

Bowman zeroes in on the Krishna figure, whose blue skin signifies a dark color. ���That���s why your precious Lord Krishna is blacker than me. He���s a soul brother,��� he says. Krishna, whose mythology involves seduction, reappears later as the patron-saint of Bowman and Paramara���s mystical, sexual adventures.

Feminist academics come out better here than in Reed���s previous work. In particular, Kala, the dark-skinned, Hindi-speaking sister of Shashi Paramara, attracts Bowman���s attention. They become friends, and he imagines their ongoing relationship. ���They would have lengthy discussions as she explained Postcolonial theory to him. Or why India shouldn���t move away from the Devanagri script.��� He hopes she can find him a discount price for a trip to India.

Oakland, too, emerges as a character, as White gentrifiers (who Reed calls ���Ubers,��� ���Digitalites,��� and ���Streamers���) conspire to push people out using technology, dogs, and police. Reed excoriates the South Asian tech bros who collaborate with them: ���NextDoor.com, which was founded by the son of Indian immigrants, Nirav Tolia, was being used by the techie invaders to spy on Blacks, some of whom have lived in Oakland for decades.���

Reed is easier on Paramara, as he and Bowman slowly eke out a friendship: ���Even though they had fierce debates, he���d grown fond of Shashi.��� Little by little, Bowman���s housing and protecting Paramara emerges as the central metaphor in the story.

The novel falters momentarily, however, when Bowman, in his research, conflates South Asian colorism, racism and caste: ���For these Brahmins, fake and otherwise, Blacks are Dalits. Untouchables.��� In India, a country of 1.4 billion (the population of Uttar Pradesh state exceeds that of Nigeria), one finds multitudes of dark-skinned Brahmins, light-skinned Dalits, and all permutations in between. [For the last two decades, light-skinned Kashmiri students have been catching hell; soldiers from other regions, who find Kashmiris easy to identify, have begun firing shotguns indiscriminately into crowds.]

And yet Bowman, contemplating these issues from America, has a point. When the Hart-Celler Act of 1965 lifted immigrant quotas for India, it benefited those with access to infrastructural and financial support, i.e. those from the upper reaches of a highly stratified society. One leading Sri Lankan-American artist said that caste, though verbally downplayed, often revealed itself in ���associating with Whiteness, while distancing from Blackness.��� Earlier encounters between South Asians and Africans in the United States, however, had a somewhat different tenor.

Lal Lajpat Rai, independence leader (and mentor to Gandhi) visited America in 1907. He met with leading Black intellectuals at Tuskegee University, and published excerpts of W.E.B. DuBois. Vivek Bald has shown that Black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods like Harlem and Black Bottom absorbed South Asian ship workers and traveling merchants by the hundreds. [Rozonda ���Chili��� Thomas from the super-group TLC is descended from Moksad Ali, a Bengali who settled in New Orleans in 1883. Her uncle, Badu Ali, discovered Ella Fitzgerald.] According to Vijay Prashad, Huckeswar G. Mudgal, the foreign affairs editor of the Negro World Magazine (published by Marcus Garvey���s United Negro International Association) was born in India. In Black Crescent: The Experience and Legacy of African Muslims in the Americas, Michael Gomez claims W.D. Fard Muhammad was a New Zealander of Pakistani extraction. Fard ministered to Blacks in Detroit; Elijah Muhammad was his student. There are many other such examples.

Conjugating Hindi then, addresses, in a time of mono-narratives, historical amnesia, and a denuded media, the question of solidarity amongst non-Whites in America. It lives in the new, tense space between the international labor demands of Silicon Valley, rising xenophobia and nativism, and America���s schizophrenic approach to its racial past; where the Chief Executive of Microsoft, Satya Nadellin, an Indian-American, can issue a memo defending a logistics contract with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), at the same moment that ICE separates 70 South Asian asylum-seeking families at Sheridan Prison in Oregon.

���You should write a handbook for second-generation intellectuals whose parents migrated from the Indian subcontinent about how to deal with White Americans,��� Paramara says.

���Maybe I will,��� Boa says.

Director Rome Neal embraces Frank Martin at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe June 17th performance of Life Among The Aryans.

Director Rome Neal embraces Frank Martin at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe June 17th performance of Life Among The Aryans.Back at the Nuyorican, a bright-eyed young volunteer offered me some banana pudding before the show. ���How did you find out about this?��� She asked. I showed her my copy of Conjugating Hindi, and told her Reed had been first published by Langston Hughes. ���I���m more excited to see the show after what you���ve told me,��� she said. She hadn���t heard of him before.

Many younger readers are unfamiliar with Reed���s work. The literary establishment, with whom he has clashed, might prefer it that way. Many have not forgiven him for his vocal objections to the movie adaptation of The Color Purple by Alice Walker (directed by Steven Spielberg), and, more recently, his disassembling of the movie Precious, based on Push, by Sapphire (directed by Lee Daniels).

And he continues to breathe fire. Here Bowman explains to Paramara his problem with the New York literati: ���That���s the same reason they���re pushing these African writers. They���re being brought in as cultural reinforcements by these wannabe colonialists. Their role is to undermine the Black vernacular, a language of uprising, and Britishfy the Black writing scene.���

The flap copy refers to Conjugating Hindi as Reed���s ���global novel,��� a new form, which ���crosses all borders.��� At least twenty sentences written completely in Hindi appear in the manuscript. After five decades, Reed, with his deep understanding of American Media, an encyclopedic knowledge of American Letters, and a persistent curiosity, continues to produce innovative, satirical, caustic material. While Reed often writes with the (in his words) ���wrath of an Old Testament God,��� ethical concerns sit at the core of his work; Reed, even while clowning his characters, sketches out the terms by which people can learn from one another, without erasure.

Life Among The Aryans is showing Friday June 22nd, Saturday June 23rd, and Sunday June 24th at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, 236 East Third Street (between B & C Avenues).

June 21, 2018

Living for the ball

On the beach near Toubab Dialaw in Senegal, the boys meet every evening to play soccer. Image credit Jean-Marc Liotier via Flickr.

I have an interesting relationship with football. With all my passion and love for the game, I��have��only attended one local football match��during the past��30��years:��a��Nawetaan��tournament��match,��which ended in a fight.

The��Nawetaan��is a��three-month long��annual��tournament,��played between July and January��in every district of Senegal. It��coincides��with the rainy season. The movement started in the 1950s��among seasonal migrants known as��Nawetaan��and gained prominence with the development of ASCs (socio-cultural associations). It was meant to keep students busy during holidays and have them take part in community��activities��and development.��Currently, the��Nawetaan��consists of��3,500 ASCs and nearly��500,000��players. It has its own managing entity, ONCAV, with a status and procedures and has become a source of income for many people. The��Nawetaan��tournament��is the most decentralized��sporting��activity��in the country and��is��popular��beyond measure.

The��Nawetaan��is also a place of violence and unreasoned passion. Every year,��Nawetaan��supporters are��arrested,��injured and infrastructure��is��damaged.

It is��an understatement to say that football is the king of sports in Senegal. Many Senegalese consider May 31st, 2002 the most important date of our sports history.��On that day, the Lions��of��Teranga, as the national team is known,��beat the French Crows.��Forget about��Amadou��Diaba���s��1988 Olympic medal, Ami��Mbacke��Thiam���s��World Championship of 2004 and the numerous African and world��champions of karate, wrestling and��aikido.��Also, never mind the��national��basketball��teams��� (both women and men) African titles and World Cup participations.��Nothing��compares��to 2002.��Football is the king of sports in Senegal.

However, with all the fever the game��generates, authorities have missed the opportunity to��invest in sports infrastructure, sports education and security.��This,��despite the fact that��sport competitions��such as��the��Nawetaan��tournament,��are��often��a niche of entertainment for thousands of jobless, unqualified young people, a place of dumb violence and a strong base for local politicians.

The��Senegalese��Football Federation and the National��Premier League were��both��founded��at independence��in 1960. Yet,��since then��only one Senegalese stadium meets the security and technical standards��to play international matches. Last July, during a match of��the professional championship, eight��people died at��Demba��Diop��Stadium��in��Dakar��after a fight and the fall of a wall.

When there are football matches of the national team, a specific budget is always allotted��for the��preparation, and the��supporters��� association,��12eme��Gainde��(the 12th Lion),��is mobilized.��While this is all well and good for morale of the national team, it exposes an underlying problem of football administration in Senegal: The investments in football are not relevant, they follow��the dynamics of the competition and there are��no ambitions��to invest in infrastructures and professionalize��the��local championships.��Above all, football centers are rare, and in essence are only breeding players for European��club teams.��Also, the lack of organization and management makes it a place of speculation and exploitations with destitute young players ���smuggled��� into Europe and never meeting their dreams of a professional career.

It is 2018 and��Senegal��is again playing in the World Cup.��The nation��is called upon to mobilize��and hush any dissension or negative comment, bad omens.��We���ll oblige and��15 million Senegalese��which translates to��15 million supporters will cheer and back��the Lions��up.

Gainde��ca��kanam.��Go ahead Lions.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers