Jennifer Barclay's Blog

October 25, 2025

Just a very quick post...

I recently launched my new website, www.jenniferbarclaybooks.com, but I realised that all my books direct people to this blog, which hasn't been updated for ages. Hence this little post, which will have to suffice for now.

I recently launched my new website, www.jenniferbarclaybooks.com, but I realised that all my books direct people to this blog, which hasn't been updated for ages. Hence this little post, which will have to suffice for now.I'm writing this on a calm, beautiful evening in late October, from my home on Tilos. All I can hear right now is the sea, waves crashing on the shore.

I am trying to finish a new book about life here with Lisa my dog since I moved to this house. I've booked an editor to work with me from the middle of November. I'm hoping to have it in a fit state to self-publish by early next summer.

Life has been challenging this year since I lost my dad. But this is what I love doing, and I've met so many lovely readers over the last few months who appreciate reading about island life, that it feels like a positive goal.

Thank you for your support. I wish you all health and happiness!

March 3, 2024

Delivery, Small Island-Style

A dozen years ago – can it really be? I’ve never lived in aplace for so long! – Yorgos Orfanos showed up one day at the Honey Factory todeliver all my belongings I’d shipped from England.

Now I’ve been in my own house, equally unbelievably, for fiveyears. When I bought it, I’d agreed to buy it with all the contents and I didn’twant to change too much about this authentic little island house by the sea.But my house is finally entering the twenty-first century – which feels OK nowthat it’s 2024 and all.

It started with a trip to Rhodes a few weeks ago to take thecar for its MOT (KTEO), meet my mum at the airport, and take Lisa to the vet;then since I had the car, we went for a drive out of town. I’m pretty sure lasttime I visited the IKEA in Rhodes there wasn’t much of a showroom. That mayhave been several years ago.

This time, it was rather more impressive, and I’d beenthinking a few of my old things really had to go. Maybe I was ready for a newcouch (I have two, both second-hand, or maybe third-hand). And some new outdoor furniture. And a thick rug would be nice under my feet in the winter. Oh, and some lightweight, stackable chairs. And…

The sales assistant at IKEA at first insisted they didn’t deliverto Tilos. But luckily I knew that they did. We insisted. They checked. They diddeliver to Tilos. We placed the order.

Back in Tilos a few days later, the next thing that happened wasthat another hotplate became unusable on my old cooker. This stove was also inthe house when I bought it five years ago, and already very old, but two of thehotplates and the oven still worked. Why change it…? I even painted over the rusta couple of years ago with white enamel. Really. And painted little icons to showwhich knob was for which hotplate.

But recently it seemed the oven only had two settings, off orburning. And there were no numbers left on the knobs, so only I knew how to workit. To be fair, I have considered buying a new one, but the little hotplate forthe briki, the Greek coffee pot, has been something of a sticking point – and notbecause it hasn’t been cleaned. Most new cookers don’t have them, and I didn’twant an extra appliance. I liked making my Greek coffee on my stove.

Then one night when my mum cooked dinner, one of the knobscame flying off onto the floor. An accident? I’m not sure… But I did go onlineand order a lovely new cooker.

Anyway, so, a few days ago I was in Livadia when I saw Yorgoshanging out with a group of guys I knew, and as I said hello, I mentioned thatI’d ordered some stuff, because Yorgos is still the man who transports large itemsby truck via the big ship from Rhodes to Tilos.

‘It might be here already,’ he said. ‘What is it, chairs?’

‘Yes, and other things… Call me!’ I said. I was excited; andthen as several days passed, I figured it must have been someone else’s chairsthat had arrived.

Delivery to Tilos is fairly haphazard, at the mercy of boatschedules plus mysterious other obstacles. Christmas cards from the UK arrivein February. Last year I ordered something from a company that refunded my moneybecause it took so long to arrive, even though I told them that was normal.Yesterday I received an email from another company asking me for feedback on my recentpurchase of a new bag. Don't you get tired of being asked for feedback on everything? But in any case, it hasn’t arrived yet.

This morning was Sunday morning, as peaceful as most Sundaymornings at this time of year. Lisa stayed in bed after a big walk to the monasteryyesterday, so I made myself a Greek coffee and a little breakfast. Then I noticedsomeone standing at my gate, and heard my name shouted. It wasn’t Nikos thefisherman, and didn’t seem to be one of the farmers with vegetables…

It was Yorgos, with a truckload of boxes that he said were allfor me.

‘Where d’you want it?’ he asked as he and his helper startedunloading and carrying stuff in.

I suggested they just stack most of the stuff against the outsidewall and I’d sort it out myself, but clearly the cooker at least would need to finda place in the kitchen to await the electrician.

‘If I’d known it was coming,’ I said to Yorgos, smiling, ‘ifyou’d called me, I could have made some space and cleaned…’

But Yorgos perhaps thought that most people would have theirhouse already in some kind of order and cleanliness, i.e. as a general state ofaffairs. Whenever I clean, I think how nice it looks and that I should do it moreoften. But then I go for a walk instead, or into the garden to plant some seeds.And with my front door always open, the kitchen floor seems constantly coveredin mud, dust, sand and bits of firewood.

I hurriedly moved boots, dog food, bags, socks, snorkel, sarongs,etc etc and swept a space for the cooker, and the guys carried it in.

Yorgos said, ‘Don’t stand on it,’ and grinning, pointed to theicon on the packaging on top of the cooker that did in fact show a pair of feetand an X over them.

‘Oh, I was hoping to dance on it!’

(And anyone who's been to a party in my kitchen knows that stranger things happen.)

The whole thing had taken maybe ten minutes and then they weregone, with everything piled neatly. I thought Yorgos probably doesn’t callpeople in advance because this way it all gets done quickly, or asthey say in Greek, derived from the ancient Doric I believe, ‘taka-taka.’

It was a warm, sunny morning, but somehow it felt likeChristmas. I retrieved my coffee and started opening my first package.

October 2, 2023

The Last Anemos Sunrise

‘These may be the last days ofthe taverna.’ It was a text from Minas on 10 September.

What?

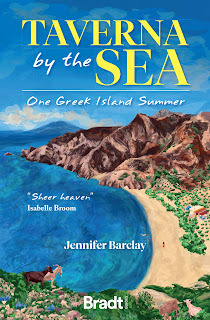

This was the taverna where Ilived in north Karpathos, helping him out for a couple of years. AnemosSunrise: anemos meaning wind; the sunrise from behind the church ofAyios Minas. I’d been there early in the summer, delivering copies of Tavernaby the Sea, and had hoped to visit again in September. When Minas explained,it came as a shock.

Since the area is protected, Minashad created the taverna from an existing agricultural building, re-making everythinginside literally from floor to ceiling, filling it with the necessary equipmentand working to ensure it met every restaurant regulation, some of them hard tobelieve. More importantly, he had also created countless memorable meals, sungcountless songs, drunk countless beers and painted countless pictures, making Anemosmagic.

But the owner of the property wantedto end the lease.

Minas said a spitaki wasfree for me to stay in since his summer helpers had left. Leaving Lisa happilyat home with two of her favourite people – it was still hot for her to be goingon adventures – I left a few days later.

Luckily, there was a same-day ferry connection via Halki, where I swam, chatted with people in shops, had a sunset beer near the thick old tamarisk tree where the fishermen sit. I had dinner, and finally lay down and closed my eyes for an hour in a hidden spot under the stars.The big ferry loomed into view shortly before 1 a.m. and was due to arrive in Diafani in the north of Karpathos just an hour and a half later. I’d told Minas I was happy to spendthe night on the beach there since he was running the taverna on his ownand needed his sleep. He said it would be windy and insisted on coming to pickme up. He set two alarms… but the phone wasn’t charged. I reverted to plan A, put on an extra layer of clothes, borrowed a cushion from a nearby cafe and manageda few hours’ sleep before voices woke me. I saw a red glow on the horizon before the sun rose fromthe flat, rippling sea.

In the bright early morning, Ihopped on the bus up to Olympos with a small contingent heading to school. Thelight on the pine forest and limestone crags as we ascended restored me, as didthe sight of Olympos, and of Sophia in her café at the entrance to the village making pites inher kitchen, slender and neat in her dark kavai dress and headscarf. Shemade me a perfect coffee with a glass of cool water.

Her husband Mike appeared, and wechatted about a mutual teacher friend who had lived in their upstairs rooms.Mike said there were now just a few students at the secondary school, and onlyone child in junior school, so it’s unlikely they will remain open much longer.He showed me a picture on the wall from the big class of 1953, when Olympos hada thousand residents; now there are no more than seventy. But I was pleased tosee Sophia and Mike healthy and smiling. As Minas arrived to pick me up. I triedto pay for my coffee and a pie from Sophia, but she refused. ‘Next time!’

Minas placed my backpack and boxof books in the cleanest part of the car and we drove away from Olympos. Hishotel there, Anemos, has now expanded to three rooms, plus staff accommodation– no need for that commute I used to do. But it was good to drive the routethat was so familiar: each bend in the road, each view of mountain slopes andthe sea far below, the smell of the pine trees at the top of the track, thespring water seeping across the dusty track, the bumps and twists…

And finally down to the valley atAyios Minas, where a young dog called Voula – sleek black coat, floppy ears andbright eyes – was very excited to see us. I’d met her in June. Minas’ uncleNick had saved her from the street in Rhodes when she was a pup. She’s the onlything keeping the wandering goats away from the olive trees, Minas said,especially in September, the driest time of year; the goats had torn the barkoff the fig trees beside the taverna, destroying them. The olive trees had been ravaged, lower branches bare.

He left again to drive to Spoa tofix a couple of refrigerators, his other profession. I walked through the parchedfield to the beach – still beautiful despite taverna signs and an island of sunbedsand umbrellas. The sea was exquisitely clear and blue. There's still a bit of me that belongs here.

I swam, then unpacked inthe spitaki and slept for a while on a comfortable soufa bed.

When I returned to the taverna after another swim, Minas made me lunch of localsausages with fried potatoes and tzatziki. An Austrian couple had walkeddown from the road and were eating a grilled fish and salad. Another couple cameup from the beach, ordered a carafe of wine and started a game of backgammon.It was very good to be back. I walked Voula and she went wild sniffing out the goatsin the valley, leaping and barking at them as I strained to keep hold of herlead and not be pulled over.

In the evening, after everyoneleft, we ate dinner and drank wine and talked about what was happening to thelease, and what it meant for Minas. He seemed sanguine, full of new ideas.Running the taverna was almost a labour of love, and he could make more moneydoing other things. But it wasn’t about that. He talked to me about some of thespecial experiences of the summer: mostly about music, friends visiting, connectionswith people.

The taverna was about Minas. Ifhe had to leave, the Anemos magic would go with him.

*

In the morning when I woke up, theonly sound was a sighing wind in the chimney; the wind was unusually loud for September,building to a crescendo as it blew through the trees, then falling again.

This little house – differentfrom the one I’d stayed in before – had a platform bed with carved woodenbalustrade, paper tablecloths serving as curtains to hide the olive-harvestingequipment underneath; brightly coloured flower patterns on the laminatedcupboards; icons and a souvenir mug from Symi; and – Minas’s addition – a huge,heavy battery for solar power.

He had driven to Pigadia forsupplies and I was alone in the valley except for Voula, her big eyes watchingme, tail wagging faster and faster as I approached. She picked up her toy andstarted pulling out the stuffing with determination.

I’d forgotten how hot it gets inthe taverna kitchen. I quickly made breakfast with some of Vasilis’ goats’cheese, then when Minas returned I walked to one of my favourite nearby beaches,a wild place, peaceful, blissful. Voula waited impatiently tied in the shade ofa tree while I swam with my mask, seeing large lionfish. On the way back, shepulled me up the hill, finding goats.

Down in the valley, the tavernalooked more like a home with its water tanks on the roof, a washing machine outthe back and stacks of bamboo from the dismantled teepees, another old Lada inthe field. In fact, it was a home when I lived there, and it still was a home.For how much longer?

When I got back, fish wasgrilling, there were a couple of tables of Czech guests, and a German couplehad bought my book, and Minas was drawing his picture of the bay in it - his special signature. I madea couple of coffees and did a little washing up – unnecessarily, but it feltodd doing nothing – then went for another swim. Minas made me a fish cake forlunch, filled with cod and whole shrimp, and seasoned with fresh parsley androasted red pepper, served with crusty bread.

By the afternoon, several tablesof good-humoured Austrians were in the taverna, some already reading andenjoying the book, buying copies for friends – what a treat for me to hear thatin the wonderful place where it all happened, and still be friends with Minas.

*

The next evening, I got a ride upto Olympos with Irene from the village. I’d realised at the last minute that Iwould freeze wearing shorts, and thankfully Minas had a clean pair of jeans andI still fit into them seven years later.

It had been a beautiful day. An Australian couple I’d met in Tilos last year had decided tovisit the taverna after reading my book and were surprised to find me there. We talked, Minas showed a video of a song he’d written andrecorded at the taverna, then he changed into his rock star attire and sang live for them.

His friend Pavlos also visited, and it was great to see him again. In the afternoon I'd taken Voula for a walk up the dry riverbed among the pine trees, the energeticdog pulling me back into memories and emotions from so many similarwalks. I tried taking a selfie with her before I left.

I was staying in the upstairs room at Anemos, and arrived in time for sunset. I was giving aninformal talk to an Italian walking group about my books and life on Tilos andKarpathos. The guide, Paola, had invited me to dinner with them at Drosia, the tavernarun by Evgenia and Sophia, Minas’ cousin and aunt. The group had walked 12kilometres and were hungry and tired; wrapped up in trousers and jackets andscarves, they shivered to see me in a sleeveless top. ‘We are Italian, notBritish, we feel the cold…’

Preparing to speak while theytucked into their salads and starters, I quipped, ‘I am British, not Italian, Ineed a glass of wine…’

Later, when the group departed, Imade my way back to the square, ducking into Parthenon for a quiet drink, torelax on my own in the corner while the local men watched football on TV. Amessage from Ian at home reassured me that Lisa was happy, walking withhim and chasing mice and eating plenty. The football match over, everyone gotup and left, and I did the same, repairing to my upstairs room at Anemos, whereI found the booklet I made to welcome guests years ago.

I woke to clouds, but sunshine was coming. After a short walk, passing Kalliopi’s traditional bakery with its wood-fired outdoor oven and waving at her working in her kitchen, I landed at Archontoula’s for coffee, and told her I’d written about her.

‘What did you write, that I’mmad?’ Archontoula in her Olympos dress ushered me to the balcony, indicated theflight of steps off the alleyway below she’d fallen down that summer. Taken tohospital in Rhodes, she’d had to spend months recuperating at her sister’s housethere and I assumed the café must have closed – but no, of course not, herhusband had kept it open. After sitting outside with her for a while, I got upto leave and tried to pay but she refused. I reminded her she’d refused paymentfor ouzos in June, and if she never took any money, how would she live? She hida smile, then allowed me to leave money on the counter for a few of the plaitedstrings she makes to pass the time.

I walked over to see Minas’ mum,who was watering her flowers. Minas had made a pergola for the bougainvillaea,which was thriving more than ever. She’d sold a few of my books and wanted topay me, but I said I’d prefer something she’d made herself. It was alsoimportant to me to buy a few crafts from the village, to show appreciation andsupport for the people who did and do the same for me. I left with a few bagsshe’d put together with bright, cleverly matched fabrics, and I realised howmuch creativity Minas inherited from his mother.

I’d intended to spend my last dayin the village and walk down to Diafani early the next morning for the boat.But Minas was coming up to the hotel to repair a bed and light fixture brokenby guests (‘I hope they had a good time…’) and could drive me back down to thebeach. The villagers would be busy all day anyway. He'd finish the repair work and wait for me at the car park.

I returned to the room formy bag, then saw my friends Georgia and Yianni at Zephyros café. Georgia,Evgenia’s sister, was now officially engaged to Yianni, a local artist, poetand film maker, and it gave me a thrill to see them together in her café. Iadmitted I’d be going back down to Ayios Minas, then leaving the next day.

‘Do you go to the island?’ asked Yiannis. ‘Or does the island come to you?’

Georgiasaid she’d managed to have a few swims that summer. She looked happy, and thecafé attractive with new tablecloths and Yiannis’ paintings.

From the square, I made my way downthe alley already brimming with visitors and received a warm welcome as alwaysfrom my other painter friend Yianni, with his wife Rigopoula. I carefullydedicated one of my books to give to them, knowing that as a former headteacher he would gently correct my Greek if I got something wrong. I bought a colourfulcotton blanket from them, and Yiannis gave me a wooden icon of Saint Gerasimosof Jordan he’d painted, telling me he’d chosen it for me as an animal loverbecause the saint removed a thorn from a lion’s paw. He had once given mea painting of Odysseus and reminded me that when the hero returned home afterso many years, the only one to recognise him was his dog.

Minas was waiting for me at thecar, but I needed another stop to see Maria whose little house at Ayios MinasI’d used years ago. I kissed her and she slipped a piece of homemade soap in mybag. I bought a little hand-embroidered bag and she gave me a mati todeflect the evil eye.

Waving goodbye, I made one lastdash into Sophia and Mike’s café to buy some dried makarounes, the localhandmade pasta, to take home. Thinking to use up change, I asked for a slice ofdelicious-looking walnut cake – but Sophia refused to take any money. Laughing,I found the clean space in the back of Minas’ car – on top of a sack ofcharcoal – for my bag, now packed full of good things to remind me of Olympos.To remind me not only of the beautiful place, but of the hearts of the people;to be more Olympitissa.

It was an unexpected bonus toreturn to Ayios Minas: the hills so green and untouched and dramatic, the aromaof pine trees, the quiet of the valley. Voula looked with hopeful eyes. The seawas bright blue, white ripples surging across the bay. Minas was soon cookingfish and calamari, people were relaxing with wine, good music was playing, the olivetrees waving in the wind. It was hard to imagine it might not always be likethis.

I swam around the headland, layon the smooth flat pebbles for a while, and when I slid into the sea again withmy mask I saw a dozen long, thin cornetfish. A pale blue one looked up at me,its body straight, eye wide and careful, then reversed slowly, its tail like aneedle. Continuing around the rocks I saw mayiatiko with a jaunty slashacross the eye, and hundreds of little fish like electric blue dashes.

After the sun went down behindthe hill leaving the beach in shadow, I had a last swim and spotted an octopuspeering out of a pebbly nest, and a pale grouper, then three large lionfishlingering among the rocks, their colouring varied from reddish-brown to black,their tails so delicate and dotted with decoration; I dived down towards one tosee coral-pink tips of its mane-like ‘feathers’ rippling like silk in a breeze.

A walk up the hill was thwartedby gusts that threatened to knock me over, but as dusk approached the last lightwas beautiful on the friable, khaki-coloured rock flecked with dark greenmastic bush. The pale blue sky was tinged a peachy pink. A jet-black dogappeared in the gap in the field wall, looking, her ears blowing in the wind.

Minas cooked us dinner and we satdrinking wine and talking. We set our alarms for early the next morning.

And soon enough the light wastouching the tops of the hills, the wind shaking the dry olive trees, the sungradually appearing behind the chapel on the cliffs. Just another Anemos Sunrise.With my backpack and a box of goats’ cheese, soon we’d be bumping up the dustytrack, disturbing goats from where they were sitting, pine and mastic on eitherside and the breathtaking view to the clear blue sea.

Three weeks have now passed, and it’sclear that despite his best efforts, there’s no chance of extending the lease.It’s really over. It makes me sad to write that Taverna Anemos Sunrise at AyiosMinas will almost certainly close this year. But the taverna is Minas; and he’sgot a few songs still to write.

And more than ever, I'm glad I told the story of our experiences those years I lived there.

(Minas standing on the step...)

April 15, 2023

To Partheni

On my third day on Leros in late February, I was feeling drawn to the farnorth of the island. Its main settlement was Partheni: ‘Virgin’, named probablyfor an ancient cult of Artemis, or an older goddess. The whole area was one of the emptiest spaces on the Leros map, one of the most untouched parts of Leros, cutoff from the bay of Alinda by the limestone peak of Kleidi.

It was a warm day and I’d swum in the morning and worked for a while on the shady terrace, my feet in the sun, while Lisa lounged on her bed. The electricians were drilling. One shouted a question and the other responded, ‘Logika!’, meaning something like ‘probably, should be’ – it seemed a vague sort of answer to a question about electrics.

While the road to the airstripled all the way north, I decided to take a more winding route over a green hilltopped by the church of Ayios Kyrikos. We passed some new development thatseemed out of keeping with the local styles, but also donkeys and horses with coloured tassels ontheir halters. Rounding the hillside, I was stopped in my tracks by the view below:of course it hadn’t been marked on the map, but there was a huge army base. Iknew part of Partheni was a military zone. I descended on the track, checkingwith the armed young guys at the gate that I was on the right path.

The valley ended at a raisedwall, the dam of a failed reservoir project. The new, empty road curved aroundand beyond it was the airstrip, ending at the sea beside a dry dock for yachts,and more military buildings. The sea beyond – Partheni bay, protected byArchangelos islet – was completely smooth and calm, like a lake, with fish farmsand a scattering of fishing boats. The whole place felt strangely quiet, which added to the intrigue.

In fact, strange is exactly howit should feel. Leros has a fascinating modern history – an extraordinary centurythat belies its current calm and beauty. I knew a little, but over the comingweeks that I would end up spending on Leros, I realised just how steeped the wholeisland is in its remains. A café owner would say to me, ‘We are known for somany bad things… When will we be known for good things?!’

A little history is in order,then. In July 1923, at the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, Turkey gave upits claims on the Dodecanese islands, populated by Greeks for millennia; Italy had ‘liberated’ the islands fromTurkey in 1912, and in 1922 Mario Lago was appointed Governor of what were now designated the ‘Italian islands of the Aegean’. The Italians decided the port at Rhodeswas too small for its Royal Navy, and in 1923 started to build up a base aroundthe sheltered, deep bay at Lakki on Leros. Since the island garrison comprised manythousands of men, over the 1920s and 1930s they built a new model town withstraight, wide streets and Rationalist art deco architecture, much of it stillstanding, called Porto Lago.

‘Imagine,’ Takis, a businessowner in what is now called Lakki again, told me later. ‘We were five thousandpeople then, and there were thirty thousand military personnel on the island atone time. But this is not written in the Greek history books because then wewere part of Italy.’

There’s much to tell about thisphase, but crucially, little Leros had a bay suitable for re-fuelling submarines,a strategic base that would allow aircraft to reach the Middle East, and a vastnumber of Italian military personnel. So in the Second World War, when all the Dodecanesewere battlegrounds at one point or another, Leros was a critical target, and thereare military remains in every part of the island.

Someone told me: ‘The Battle of Crete – not to diminishit – lasted one week. The Battle of Leros lasted fifty-two days. Constantbombardment.’

I followed the road around to thebay of Blefouti, unprepared for its sheer loveliness: a wide sweep of pale bluesea fringed by beach, mostly backed by lush fields sweeping up to the mountain. And I seemed to have the whole place to myself, thoughalas, only a couple of hours before dusk. I spotted what looked like acrumbling Italian observation tower on the top of the far headland, and went toinvestigate. I hadn’t come to Leros to look for war remains, yet I couldn’t help being fascinated by the abandoned buildings.

The empty road gradually gave wayto dirt track and on the slope was a large, somewhat grand building with aportico of tall arches and a large Mediterranean pine outside. This was theremains of battery Pl.899, shown on a 1940s Italian map as antinavy eantiaerei – now clearly used by a farmer to shelter his goats. We saidhello as he carried a bale of hay up the hill, his dog at his heels, the sheepand goats clamouring down the hillsides to follow him.

For now, I had to head back. Wetook a shortcut to avoid some barking dogs, and I stopped to chat with a man ata closed taverna, then we walked down the wide, empty, tree-lined road, pausingat an old double chapel with beautiful icons between a cement works andbuilding materials suppliers. A car pulled up so close I thought it might hitus, then a man with a beaming smile wound down his window and said, ‘I’mlistening! First impressions of Leros!’ It took me a moment to realise he wasone of the guys from the other night at the grill house.

Further down the road, I passed ayoung guy on a motorbike leading two ponies on ropes up the road. I stopped tobuy fresh eggs and local beer from Stamatia, and told her I’d walked toPartheni. She looked at me as if I was mad, then related a long story about herboyfriend’s animals, the only part of which I really understood was aboutslitting their throats… I was loving Leros, and staggered back to the room to readmore about it.

A week or so later, I went backto Partheni, for two reasons. The first was to pick up my mum, who was arrivingon the 7 a.m. flight from Athens. I’d just arrived atthe airport and got out of the car I'd rented when I heard the roar of the little plane comingin overhead. It pulled to a halt just before Partheni bay, then trundled backto the terminus. The passengers were out within minutes, and the airport would soon be closed again for a few days.

Later, after breakfast at thebakery in Kamara, I took Mum to see lovely Blefouti. The hills behind the baywere largely unspoiled; a few houses here and there, an organic vineyard hiddenin a fold of hills with grazing cows. In a little cove, I now recognised arusted old bit of metal as some kind of artillery.

But what I really wanted to seethis time related to a later piece of modern history. We left the car at thestart of a headland and walked above the fishing harbour, and I asked a farmer feeding goats with huge, twisted horns if we were heading the right way for Ayia Kioura.

After the Second World War, Leroswas liberated and with the rest of the Dodecanese became officially part ofGreece, though the country was immediately divided by Civil War, those who hadresisted the Germans now seen as the ‘Communist’ enemy by the right-wingestablishment. Then in 1967 there was a coup by the army, starting the Regimeof the Colonels, or the Junta dictatorship. Manyleft-wing intellectuals and artists were sent into exile on little islands. Between 1967 and 1974, political prisoners were detained at the old Italianbarracks at Partheni.

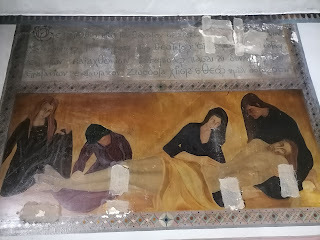

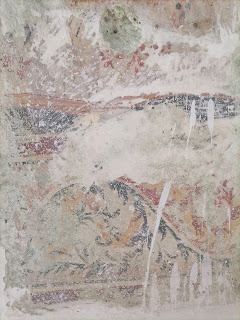

Among the ‘kratoumeni’ on Leros was Manolis Glezos, politician, author, hero, best known for taking down theNazi swastika from the Acropolis in 1941. The eighteenth-century chapel of Ayia Kioura Matrona, built on the site of an older chapel and situated a kilometre away from the camp, had fallen into ruin and Glezos organized a fewartists among the prisoners to restore it and paint new frescoes.

Work beganin 1969 with the support of the islanders. The artists used fellow prisoners asmodels. The soft, flowing, haunting figures exude a sense of peace, thelarge eyes full of emotions: true sorrow and bright hope, mourning perhaps not onlyChrist, but Greece.

The works are fifty years old, and some plaster has fallen, revealing rusting iron bars inthe ceiling; many paintings had rough patches of gauze stuck to them. Iwondered if the prisoners would not have had access to the proper materials.Then as I looked for a light switch, I noticed a sign by the door in Greek,prohibiting something odd: asvestoma. The use of lime.

I foundout later: after the regime changed, certain conservative islanders decided tolime over the unorthodox frescoes. But they’re now protected by the state as animportant monument.

Political activist and poet Yiannis Ritsos was also imprisoned on Leros at that time. One of his most famous works is 18 Little Songsof the Bitter Homeland, later set to music by Theodorakis; sixteen of them,he said, ‘were written in one day – on September 16, 1968 – in Partheni ofLeros’.

April 13, 2023

Leros at the Tail End of Winter

You may recall that back in late December,I’d had plans to go to Leros but was thwarted by ferry schedules (the only connectionswould have landed us in the port of Lakki late at night, with nowhere to stay) andwent to Symi instead. But in the last week of February, my work schedule easedup a bit, the ferries were favourable and I was feeling the call of travelagain. I was looking forward to eating some food I hadn’t cooked myself,and seeing something new.

Packing my stuff and Lisa’s, we boardeda ferry to Kos on a Monday lunchtime under darkly brooding skies, yet it was exciting to be on the move, passing the coastline of Tilos and thenNisyros. In Kos we wandered the beach and then town, gorging on delicious bakerytreats in the afternoon and mezes in the evening: oven-baked aubergine loadedwith tomato and feta, sweet potato chips, juicy meatballs and good retsina. Thenext day, the weather had cleared, and we continued our journey in brilliantsunshine, past little Pserimos (thinking I must go back) and up the wonderfullyrugged and untouched east coast of Kalymnos, the sky a deep blue, lightglittering silver on the sea.

Leros, just a stone’sthrow from the north of Kalymnos, is a similar size to Tilos but has a comparatively big population, with several villages. I’ve often heard from Greeks that it’stheir favourite island. Back in the early Noughties, I’d hopped off the ferry therein September with a bicycle, found the roads around Ayia Marina too busy forcycling, and left a few days later after getting not much further than the impressiveArchaeological Museum. Arriving with my dog and a backpack on a bright, warmlate February day, I looked forward to discovering more.

From Ayia Marina port at lunchtimewe manoeuvred through a busy section of street, then made our way in aleisurely manner for a few kilometres along a broader, quieter road heading northeastto Alinda, stopping on and off for Lisa to jump in the clear blue sea. For awhile, I sat on a little stretch of beach, laughing at how beautiful it allwas. I was on holiday, it felt as though winter might be over and it feltgreat. When you're in luck and have perfect days at the tail end of winter with nobody around, it's the best time to be on an island.

The dog-friendly accommodation I’dfound online, four rooms above a taverna, was right at the end of the road,around a few curves of headland with lovely little beaches below, at the foot ofa limestone ridge. We passed a carpenter’s workshop before arriving atVareladiko: named for the barrels the carpenter built for the wine the owner’sfather used to make. The owner, Spiros, later told me that he’d first set up amakeshift place here when it was only accessible by boat. Then the road wasextended, and in summer it got very busy, but for now I was the only guest, andSpiros and his wife were busy doing maintenance every day on the rooms to getready for opening. All around, the grass was filled with bright yellow Bermudabuttercups.

The room was beautiful, with ahuge terrace overlooking the bay, and Spiros found a foam mattress for Lisa tosleep on. As dusk began to fall, I realised the lights weren’t working, andwent downstairs to ask if there was something I was doing wrong. Spiros and hiswife sat watching TV in the closed taverna and, surprised, said they’d lookinto it. Meanwhile I walked back along the bay for twenty minutes as far as thegrill-house and ordered a mixed grill to take away for my and Lisa’s dinner,and wine to drink while I waited, chatting for a while with some local guys, banteringabout whether Leros was better than Tilos.

When I got back to the room, theelectrician and his wife were just finishing up rewiring the light fixturesinside and out, and mosquitoes were having a party in my room. In future, I’d besure to keep the terrace doors closed at dusk. My double bed creaked and the mattresssprings were prominent, and for hours the bedsprings squeaked as I got up to findand squash another buzzing intruder. Ah well, I'd get used to it... Meanwhile, I must have sortof poisoned Lisa. In Kos, I’d managed to get to the vet tobuy an anti-tick pill for her, since spring was coming. But the pill was fordogs from 25 to 40 kilos, and I put the whole thing in her food, probably a bad idea. What’s more, her dinner was some of the mixed grilltakeaway, was supposed to be a treat but I hadn’t realised that some of it was spiced with chilli. My poordog.

In the morning, however, it feltpeaceful. A few people walked or jogged to the end of the road for their morning exercise. I worked for a while at the table onthe terrace, listening to the electricians fixing the wiring in the next rooms.I hadn’t expected such a perfect beach right below, with sand and pebbles androcks to snorkel around – and not expecting swimming weather, I hadn’tbrought my mask. I swam, got ready to go out for a walk, then we got as far asthe next beach and stopped again, sitting for a while as three ducks startedquacking, marched out to the water and bobbed over a little way to see us, thenreturned complaining to the safety of their tree.

Eventually we continued to NewPalatino for lunch, where a local woman called Vayia made me a delicious Greeksalad with good vegetables and cheese and herbs. She fussed over Lisa, bringingher water and talking to me about her own dog, getting quite emotional as shesaid the only sad thing is they don’t live long. Afterwards, we continued alongthe road and veered uphill on the road leading north to an area called Kamarawith a cluster of shops. I peered in the window of an old-fashioned lookingbakery, and the woman inside started telling me all about how dogs are good andpeople aren’t, then gave Lisa a biscuit. I also saw a bedding shop, andwondered if I could surreptitiously sneak a new mattress into my room.

We followed the road a little furtherthen turned onto a lovely rocky track through green hills, andsweet-smelling yellow broom flowers, and bushes full of white cistus flowers,and more buttercups… There were wind turbines on the other side of the valleybut it was all gorgeously lush, with the sound of goat bells as we got down toAyios Nikolaos beach. A family arrived by car and the little girl asked if shecould pat Lisa.

We continued along arough track around a stunning piece of coastline, the hills looking rugged to thenorth, while to the south there were hills covered in tractor-tilled fields. Istopped mesmerised for a while to watch and listen to a shepherd whistling toround up his goats, his dog running back and forth, the only sound thewhistling and goat bells and the sea crashing in below.

In the distance, I saw a man on a motorbike leading two horses. Further on, a middle-aged man ina checked shirt waited patiently for his cows to graze on a lush patch of grass.We passed through a little settlement with fields and trees and barkingdogs, then back to the road. When I stopped at a little supermarket, the prettyyoung girl in charge introduced herself as Stamatia and told me a long storyabout how her dog went calling on another dog overnight, then insisted onfeeding a handful of dog biscuits to Lisa. I asked about local wine and learnedinstead they had Raven, a locally brewed pale ale. Wow. I might be staying onLeros a while…

‘Are you from Leros?’ I asked,intrigued by her.

She was, she said, ‘but from Partheni,far away…’

Partheni was right in the northof the island, and I decided to go there the next day.

January 7, 2023

Symi in late December: Wine, Fridges and Frescoes

There are two souvlaki houses in Symi harbour, but both turned out to be closed until the New Year. A lot of islanders went away for the holidays, and you can’t blame them after two Covid years and then a financial recovery year which was exceptionally busy. A bar had burgers and club sandwiches, but they said one restaurant was open around the harbour. I wanted a big dinner as fuel for walking the next day.

The restaurant was open, empty (it was early), didn’t have any of the oven-baked food I’d hoped for, and was quite expensive. The salad was mostly rock-hard tomatoes. But it had a nice view over the water, friendly people; gradually other customers arrived, a group of English people who had a house here, and two frozen-looking Germans who’d arrived on a boat and ordered tea and fava.

The owner came to talk to me when he wasn’t busy, and I was pleased to chat in Greek – I don’t get enough practice at home. Asked if I was staying for New Year’s Eve, I explained I’d like to but would have to find a cheaper place to stay. By the end of the evening, I was being offered a room, an extra slice of cheesecake and dinner on the house… and a waitressing job.

So I did wake next morning with a certain anxiety. How do these things happen? No matter, it could all be resolved later.

It was 28 December, and outside my windows that looked straight out onto the water, cars and scooters were zipping about. The sun briefly hit the other side of the harbour around 9 a.m., then went behind a small cloud, and everything was still damp and cool, though forecast to get warm. I made myself a Greek coffee and sat on the lovely balcony, listening to cockerels crowing somewhere back around the Kali Strata, the steps that lead up to the Horio flanked by mansions from the late 1800s.

Despite visiting Symi several times – often for its great hardware shops, I must admit, though with good walks also – I’d never been up high in the centre of the island on foot to see the old wine presses. These sunny, bright winter days were perfect for it, though I’d have to set out by mid-morning given it was getting dark soon after five.

We set out inland from the back of the harbour to reach the cemetery at Elikoni, didn’t see any markings for the path from there that was on the map, but found a way up the dry riverbed a bit and through gates, passing sheep that approached rather than ran away, until suddenly there was a beautiful old stone-paved donkey path or kalderimi that twisted back and forth up the hillside, making the going easy all the way to a church or two and small group of houses. It was a wonderful start. By then we were already in very warm sunshine – I wished I’d been able to dip Lisa in the sea before we set off – and lovely countryside.

Turning left, we followed the gradually ascending road past the Xisos turn-off and eventually to meet the main road that crosses over the top of the island and heads down again on the other side to the big monastery of Panormitis. Thankfully at this time of year there was no traffic, just the sound of sheep bells (and a jackhammer far below, of course, this also being perfect weather for construction work).

There was a nice little detour on a kalderimi again, beside a field where someone was burning olive branches, to the chapels of Ayia Katerina and Panayia tis Stylou (tempting to think of the name as a corruption of tis Tylou, ‘of Tilos’, since there was a view of our island!). After a couple of hours of ascending, it felt as though we were in the uplands, the road unexpectedly winding around cultivated valleys scattered with monasteries, and eagles and crows circling around Vigla peak just above (617m, the highest on the island), with what looked like a broken wind turbine.

I had decided to aim for the ‘Pano Krasokelia’, Upper Wine Presses, following the directions in Kritikos Sarantis’ booklet Discover Symi on Foot – copyright 2007 but bought here just a couple of years ago so hopefully it wouldn’t be too out of date – along with an also locally produced walking map. Blue and red paint dots also marked paths here and there.

Passing the padlocked monastery of Ayios Konstantinos , I continued to Ayios Nikolas as directed, but there was no sign of the path if I was reading the instructions right. There was a truck outside and washing hanging to dry, but nobody to ask. After a few attempts to find the way across rough ground with gates very tightly wired shut, I had to give up. Perhaps on my own I’d have tried harder, but it wasn’t worth making Lisa walk through fields of thistles.

Back to the road, instead I took the turn a few minutes later to Kokkimidis, following a narrow, pleasant concrete track that ran below those elusive wine presses into beautiful hilly uplands, with enclosures where again the sheep and goats seemed to approach rather than run, and there was a stone-build pond filled with water. I realised I hadn’t seen anything like the death toll of goats we have on Tilos this winter. Although the fences and gates here might be limiting, the animals were looked after, fed and watered.

The track led to a cluster of historic buildings through gorgeous countryside, and at some point, someone in authority must have thought: what a perfect place to throw the old fridges down the mountain! For there, lo and behold, was that scourge of the Greek islands, the edge of the old dump, spilling down the hillside towards the forest.

But at Ais Yiannis Tsagrias, the gate wasn’t padlocked, and the door wasn’t locked, and inside were some of the oldest frescoes on the island. They were dark, hard to make out, but showed up clearly on my phone camera and were thrilling to see. Stepping outside again, I felt blessed to have been able to come to this place and find them, surrounded by spectacular hills covered in rocks and forests, with a stellar view of our modern-day contribution, a cascade of rusted appliances.

Just beyond were the remains of an ancient hilltop fort (above: Lisa shocked that you could see the rubbish dump from here too?), perhaps repurposed once as a farm. There was a big stone water cistern, and a little further along a primitive ancient wine press, just a block of stone with a circular carving, in a padlocked enclosure for animals.

Beyond there, past some old stone terraces at the end of the road near large old trees was Kambiotissa, a monastery built like a fortress with tall walls and still seemingly guarded thus with padlocks and fences all around. I tried following the fence around to the back and glimpsed what perhaps was a more recent wine-pressing building, but it was hard to tell.

We were tired, and Lisa was keen to head back, but I decided to take one last detour uphill to the monastery of Kokkimidis, joking aloud to Lisa that this one would make our day, even as I fully expected it to be padlocked and fenced. But hallelujah! A car I’d seen earlier, perhaps the only car in hours, speeding up the road, was parked at the top of the winding track, and the gate open.

I heard voices inside, but seeing nobody, I left Lisa tied to the fence and tried the door to the church, above which was an old plaque alluding to a restoration in 1697 – and opened it to an astonishing little church, every inch of walls and ceiling painted with fascinating, beautiful scenes.

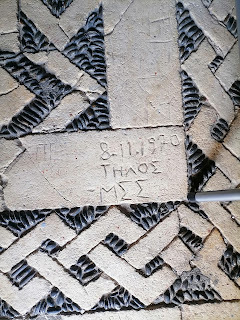

The floor was a pebble mosaic, with an interesting bit of graffiti in it: 8.11.1970, Tilos, and some initials, carved into the stone - that must have taken some dedication! Perhaps M.S.S. was the person who made the floor?

It had been a stroke of luck to find the place open; and I'd have missed that if we'd got to the wine presses. And so, we walked back down, in beautiful light, everything still and glowing, the sea glassy, Lisa determined that we should go back exactly the way we came, while I felt we should take the road as dusk was falling. We compromised by trying a bulldozed track which led to a wonderful old kalderimi, which led all the way to the Horio.

From there Lisa guided us down to the Kali Strata, down to the harbour for dinner - and a bottle of wine on special from the old supermarket. 'Kalo Pascha!' the owner with the dry sense of humour wished me, happy Easter, and I looked puzzled. 'I'm getting ahead of myself,' he said, 'can't wait for winter to be over.'

December 31, 2022

A Winter Trip

In the quiet days of winter, I love to travel to other islands. Although it’s beautiful here at home on Tilos, for a couple of months now I’ve been looking forward to going somewhere new and seeing something different. Since family and friends all left in early December, Lisa’s been bored, wondering where everyone is. So once I’d finished some pressing work, I was all set to go to Leros and do some exploring.

But Leros had other ideas. Suddenly in the post-Christmas week all the boat connections were difficult, and meant arriving late at night in a place with no affordable dog-friendly accommodation to be found online. I may have a reputation for being intrepid but even I didn’t fancy that. At last I found a lovely place – but the owner said he’d made a mistake and it wasn’t available at all. Fed up of checking Airbnb and Booking.com, I decided not to go to Leros.

Still, I fancied going somewhere. Symi was much easier, just a two-hour (or less) ferry ride away. Accommodation is usually expensive but I found something that looked decent and booked it, and suddenly was very excited about going back to Symi on my own in winter, when the weather forecast looked promising – yet it wouldn’t be too hot for walking up into the hills. I’d passed Symi often on the ferry to Rhodes over the previous months, and looked longingly at those empty hillsides.

The sun felt pretty hot as we boarded the SAOS Stavros on Tuesday lunchtime. As usual with that ferry, it felt like a private taxi with hardly anyone on the boat, and was idyllic with the view of blue sky, blue sea, blue islands, sunlight gleaming on the water, until the crew started washing the deck and we had to move around trying to find a warm dry place to sit or stand.

The SAOS takes a bit longer than the Blue Star, but it docks at the old place by the clock tower, not the ugly modern one on the other side of the harbour. It should have been a short stroll to the room – except of course, Lisa had to sniff every bit of street furniture very carefully for information about other dogs. It seemed a lot of dogs had been peeing on the artificial Christmas trees.

The room, right overlooking the harbour, was both beautiful and hilariously odd; the bathroom was reached up steep wooden steps and to get to the sink you had to duck under a wall that reached down from the ceiling to about shoulder height; I had no doubt that I’d be walking straight into it one night half-asleep.

Starving because I hadn’t had lunch, I nipped into a nearby supermarket and found all sorts of foreign delicacies: you know you’re in Symi when you can buy smoked salmon and real Roquefort… Then with a very fast turnaround we set off wandering, to make the most of the couple of hours of daylight left.

With the Kali Strata to our backs, we crossed the ‘Gefiraki’, the little stone bridge next to the old customs house, towards some of the grand public buildings, then Lisa decided we should head straight up some near-vertical steps, which twisted around houses and then emerged at a plateau with paths running between smallholdings. I found our way back to the cemetery, from where I knew the way across to Nimborio Bay, passing the big old stones of Drakounta and an ancient wine press, and following the stone track down to the water.

After Lisa had a swim, we walked around the bay to the beach at the end; I'd been this far a couple of times, and once in the heat of summer with a friend had taken the path up the hillside via the old churches and underground caverns, then over the hill and down to Toli.

I hadn’t really expected to get anywhere new on this first afternoon, but thought I’d at least look for the start of a path, following directions given on the local map by Kritikos Sarantis. The path turned out to be well marked by blue paint, leading up the side of the hill, the hillsides beyond lit up bronze. It was getting late, but I knew we could walk back along the road in the dark. Lisa didn't know that and was panicking a bit.

One thing that would be confirmed on this trip, as we found on our trip to Nisyros, is that often the paths marked on the ground aren't shown on every map. As I check the Skai/Terrain map now, which I bought on the last day when the other map was falling apart, this path isn't on it. In a way, that's part of the adventure - you never know what you'll find.

The stone path led tantalisingly up and up until at last we reached Agios Nikolaos tou Stenou on the ridge just as the light started to turn paler. Over the other side, old terraces led down to a bay.

We just got back down to Nimborio for dusk, the water still, the air warm, people fishing from boats and throwing lines from the shore, all so silent except for the call of a bird.

We took the road back, turned inland towards Harani and the dry dock, and suddenly there was a harrowing, persistent noise, which spooked Lisa. It got louder, so much so that I laughed when I saw the Karnagio café open – you’d have had to be deaf to enjoy it. It turned out to be just a couple of guys hammering and power-sanding the rusty old hull of a boat.

Beyond the clock tower in the main harbour, things were more peaceful, and all the lovely churches lit up. I stopped in at a shiny new supermarket to buy dog food, but it was eye-wateringly expensive, perhaps not surprisingly given that it’s opposite where the shiny yachts moor. I continued around to the end of the harbour and to the old supermarket hidden down a narrow alley, where the price of dog food was more reasonable and the friendly owner, whose sense of humour I’d appreciate over the coming days, wished me ‘Bon appetit!’

Having fed Lisa and unpacked a little, I decided to celebrate an excellent arrival, and although there were several cafes open, I pushed my luck by seeing if I could sit at the old men’s café without causing a stir. It was beautiful, old-school, no plastic walls or heating, no cushions or cocktails, just wooden chairs and iron-and-marble tables and a simple counter inside. Although I got a strange look from the patrons when I approached, the owner was happy to serve me a glass of wine in a sort of schooner, and I wrote up notes in peace, overhearing someone inside giving a long ouzo-fuelled diatribe punctuated by assenting murmurs from the other table.

It was a nice start to what was going to be a magical little trip.

November 6, 2022

The storm is coming

It’s Sunday morning, 6 November, and we’re preparing for a storm – though the sun is still warm and bright. For weeks we’ve woken to perfect blue skies and calm but now dark grey clouds are gathering and a restless wind blowing from the south.

A thunderstorm is always hard for Lisa so I’ve given her an extra-nice breakfast. There’s a comfortable, dry space in the woodshed for Fishbags the cat. As for the other cat - the one that shows up several times a day meowing for food, however determined I am not to have a second cat - it will fend for itself, I'm sure. That one is 'The Cat Formerly Known as Girlfriend' - the one that acted like Fishbags' girlfriend, until its anatomy developed. I'm not sure if they'll still share the space in the woodshed.

In summer I remove some of the windows to let the wind blow through the house, and replace them with wire mesh screens; yesterday seemed a good time to put the windows back on. We rearranged the kitchen furniture – my furniture is always rearranged with the seasons – to bring in a second couch from outside, an old bed piled up with cushions. I covered the big old couch outside with a tarpaulin.

There was a strange day or two of rain in August and a day in mid-October, but otherwise the ground hasn’t been soaked for many months.

The island’s roaming goats have been suffering with nothing fresh to eat; in a half hour’s walk from home we see half a dozen dead or dying.

Olives suffer from the late rain too – they like a good soaking in October. This week I gathered them in from my two trees. It seemed a little early, and others had firmly told me ‘Not before the rain!’ but Antonis, visiting with some olive oil, said they were ready for alati, salt; he meant brine, and explained how to test the saltiness of the water by seeing if a fresh egg just rises to the top. I spent an hour or two later pruning the olive trees, then decided to open the 20-litre barrel of attempted wine from this summer’s grapes. Excitingly, it smelled and tasted good! Still a little fizzy and cloudy, but certainly more like wine than vinegar.

I’ve been watering my garden every few days; I’m still picking a tomato or two every day from my plants, and there’s rocket, the spinach is coming back, and the radish seedlings are coming up. I’ve been grabbing a handful of dates from the palm every day; they have big stones, but the taste of fresh dates for free is a sweet treat. I’ve been planting, thinning out seedlings, digging new beds, heartened that gradually the garden is yielding more. The jury's still out on whether the avocado tree will survive.

Some delicious flavours of the new season came this week on Dimitris’ truck: seskoula or chard, boiled and served with a squeeze of fragrant local lemon, as well as chopped garlic and olive oil; a feast with potatoes, and salt-cured fish, and feta, and just-ripe mandarins. Dinner tasted great with retsina, but we also ordered some red wine, white wine and souma from Embona in Rhodes for the winter.

During September and into October, if you wanted to go out for dinner, it was hard to get a table in Livadia. Now, only a couple of restaurants remain open. The kafeneio in Megalo Horio closed its outdoor terrace, and has a cosier, locals’ feel; food is available but might have to wait until the card game is over. The island is quiet, with fewer cars around. The bus stops in mid-afternoon.

On the dry paths high on the hillsides we’ve seen mauve colchicums, a few mauve crocuses and a tiny delicate autumn narcissus. I’ve heard melodious birdsong while sitting at my desk with the door open to the garden. We’ve seen eagles circling in the sky, kestrels and owls taking off. The moon and stars have been very bright at night.

The sunshine at this time of year has lost the burning heat of summer and is easier to enjoy; I’ve found it impossible to stay indoors too long, when the temperature is so good for walking. The late afternoon light is radiant, golden. Walking back from a walk in the warm dusk under a bright moon, you hear the peep of the scops owl.

Though many beaches are in shadow by mid-afternoon, the sea has been clear, warm and calm, ideal for snorkelling. At Eristos, for the first time, I saw small calamari very close to the surface; I’ve watched pearly razorfish with their soft, delicate pink and green colouring, pottering around the seabed alone. A germanos, spotting me, raised all the spines along its back, its mouth an ‘o’; an octopus hid motionless in a little cave, disguised by making its head as spiky and mottled as the rock.

Off the beach near my house, thornback rays have been gliding elegantly across the seabed with their wings billowing to either side and their long, pointed tails. I’ve been close enough to see the subdued gold under the mostly greyish brown, the little point of its ‘nose’ feeling its way in the sand, the back flipper guiding. A few times I’ve seen flat little flounders crowding the ray’s tail as it forages in the sand; and a white trevally, striped with yellow, hovering directly over it, picking at it. Bizarrely, when a ray took off and sped away at a hand’s height above the seabed, the fish went in seemingly hot pursuit, hovering either above or below the ray. Funny fish behaviour.

And still once or twice in late October I’ve come back from the beach exhilarated and showered off under the hosepipe in the back garden, looking over red and pink flowers and through bright green palm leaves to the blue sea and headland beyond.

Flies and damp evenings heralded the change in the weather. Now the wind is beginning to get up again, tossing the bougainvillaea around. A crow caws. The thunder begins, and gets louder, the sky gets darker… The first drops of rain are pattering.

October 31, 2022

Walking on Nisyros - Part Two

Looking for Kateros - between a rock and a hard place

German friends who live part of the year on Nisyros had told me about an old settlement at Kateros, marked on the map; there was no path but it was just a question of picking your way around the mountain.

Gradually we were piecing together the footpaths. From the top of Mandraki just beyond the upper Temak machine where the narrow road ends we took the path leading right between fields, then turned right again up old stone steps up to join the stone path to Palaiokastro. We started up the road and veered right at the concrete water tank onto the kalderimi running below and parallel to it.

While following the kalderimi the previous evening, we’d noticed it branched off downhill to the southwest, in the direction we wanted; it turned out to be well maintained and led to a few spiladia restored in traditional fashion, with fences of natural wood. I suspected they were foreign-owned, and sure enough we met a German woman. She said the path didn’t go any further than the houses, but we continued anyway, heading towards Karaviotis mountain.

Soon we were looking over the narrow valley, thick with trees and dotted with stone ruins, that leads down from Ayios Zaharias (marked wrongly as Ayios Nikolaos on the Skai map?) to the sea. And a red-dotted trail went down into the valley and up the other side. We took it as far as a chapel to Ayia Marina; then the dots seemed to rise a little then disappear. In the absence of any obvious landmarks, we simply headed around the mountain.

Eventually we headed up where we probably should have gone down; it was hard to know on first attempt but the views were glorious.

At last we came to a hidden, rocky valley, with traces of terraces. Trying to get a sense of the lay of the land, Lisa and I enthusiastically climbed up the other side of the valley, and found ourselves on an outcrop of strange, knobbly rocks.

This we negotiated for a while but until common sense seemed to dictate a retreat. Lisa, the hero, found a relatively easy way down, which emerged at the top of the valley just below a ruined building at around 400m.

While Ian went to look for a more sensible path forward, I explored behind the building, finding cave shelters with walls on the inside, notches in the rock face and post-holes for a gate, and stone troughs; and then, to my surprise, a deep shaft leading down below the rocks, with steps cut metres below, too far to reach without a rope or ladder. It seemed mysterious; though someone had been here recently, judging by scattered cigarette filters and a frappe coffee cup.

Then I noticed writing on the rock above: ‘H Dexameni ton Pyrgon’, the reservoir of the towers. Only the next day, seeing a different map, did I learn that this area is known as Pyrgi because of its ancient towers, part of a beacon system.

Ian returned with bad news about the way forward; given the dwindling daylight, finding Kateros and the way around the mountain would have to wait. We made our way upwards instead, both of us hoping the way back would be clearer…. And lo and behold, red and blue dots appeared and guided us on carefully laid rocks and over tricky rock fields, back to the church at the road.

There was a gleam of red in the sky as we made our way back towards Mandraki, then the sun began to fall beneath the layer of cloud, bright and pale behind streaks of red, then slowly sank into the sea. Of course, it was clear that to reach our goals we needed to set out earlier, and maybe camp overnight, which we couldn’t on this trip. Others might drive part of the way, but it seemed much more fun to be exploring as much as we could on foot, finding things along the way and getting to know the routes - the journey being as important as the destination.

Back in the room later, there was moonlight on the sea.

Rain and the windmill

Quiet morning with the power and water both off, just the sound of the sea in the harbour. I walked along the coast a short way, over the rocks in their beautiful ochres and rusts, crimson and brown. When sun came through the clouds I swam and found myself surrounded by a big group of long, slender fish close to the surface - loutsos perhaps, or large zargana; there were white trevally and grouper, flounder and flathead mullet and bream. The clouds came over again and the sea turned greyish and darker. The old guy who’d been fishing off the rocks went past on his scooter holding his rod, with a paint-bucket he used as a keep-net on the back.

It rained all afternoon, but later in a pause in the downpour, we risked a walk in the hills. I’d seen a red splodge on a rock on the road above the village indicating a route to the windmill. It turned into a fascinating network of old paths that branched and branched between terraced farms for kilometres.

Each old farm had its stone buildings, its trees and cisterns and threshing circles, gently curving terraces, sheltered of a fold in the hillside; amazing that such places were abandoned. We came upon a chapel with a wick burning in a bowl of oil – but we saw only goats and sheep. Below on the coast road there was a blaring of horns from the wedding entourage – the son of the owner of a taverna was marrying the daughter of the owner of a supermarket. Rain is a good thing, so fingers crossed it was auspicious.

The path started breaking up; we found our way back along terraces to meet the road that wound down above the village, passing the football pitch. During an hour at the archaeological museum this morning, I’d learned it was when they were digging to build this in the 1980s that they started to find remains of funerary cremations dating from the eighth to the fifth centuries BC. People were buried with sophisticated pottery from around the Aegean and Phoenicia, modern Lebanon, as well as local pottery decorated with lions and sphinxes inspired by contact with the East. The dead were also left with foods to help on their journey – olive oil, wine, honey, figs, olives. Funny that they went ahead and put the football field on top of it, two and a half thousand years later.

As we reached town and descended the steps to the Old People’s Square, we passed the church with wedding tables laid out, and guests sheltering under shop awnings from the rain that was coming down again. By the sea, it was windy and cold. There would be music in the village that evening for the wedding, but – brrrrrr… I didn’t want wet feet.

Food Interlude

With walking so much, we worked up a huge appetite. But most restaurants were gradually closing for the season or had closed already. Still, less choice made things simpler.

On the seafront, Issikas was open for a few days but had wonderful chickpea fritters (known locally as pithia) and skordalia or garlic dip made with almonds, and herb-infused meatballs, which we washed down with lashings of cold red wine. Then we started going to Hochlaki, with friendly owners and similar very good food, plus local cheese, and vegetables baked in the oven. Vegos in the Old People’s Square did a fabulous salad with two different cheeses made by the owner, sakouliasti and a soft cheese, and good olives that weren’t mass-produced.

On the night of the cold and rain, I would have been happy to stay in and have raki and peanuts for dinner, but in the end we made it out as far as the first place, Aigaio, mostly a souvlaki and pizza takeaway but with a few high tables just behind the town beach. We ordered salads and souvlaki and chips and it was a feast fit for a king (who'd been walking for a week), and we drank enough cold retsina that we were soon singing along to the good old rock classics playing on the radio.

Emborio and Lakki

At midday it was breezy and sunny again, rainclouds gone. Heading up from the Temak on the footpath veering left and crossing the road, we looked for the continuing footpath. It was marked on the map so we wanted to give it another try, but as Vasilis had warned us it fizzled out fast. So we hiked up terraces again, not stopping this time but hoping to find Armas quickly and head across to the road to Evangelistria. We ended up way too high and had to scramble back down a steep slope...

From the clear signpost at Evangelistria, the beginning of the old footpath to Emborio seemed to lead over a mess of rocks through a sheep farm and there were a few unclear sections. But before long, we came to the stone-built cistern and ruin of a house built of red rock in the side of the hill, and from there on it was clear and beautiful, with some amazing lava formations towering above, and the lush valley below. The little square of Emborio on a sunny Sunday afternoon in October was packed with taverna tables.

Instead of lingering, we looked for the path down to the caldera floor, or Lakki, and found it via an alleyway not far above the square. Despite some rough sections thanks to building rubble and fallen walls and so on, it was a superb, wide, black-stone path that wound down gently to the caldera floor, with a few ruined houses and a chapel.

It continued beyond the road into farmland, but we were looking for the start of the path that would take us up between the steep hills of Boriatiko Vouno and Nyphios. This was the path I'd done four years ago from the other direction. Alas, I got the start slightly wrong, misled by an old Geopark sign which I thought indicated a walking route but actually just pointed out a geographical feature… However, we scrambled up the scree without too much trouble, knowing there was a good path on the other side of it, and followed that all the way back to Evangelistria in lovely afternoon light.

It had been a splendid afternoon of walking in sunshine, and with a little daylight left we tried our luck with a path downhill marked ‘Man’ for Mandraki. It fizzled out to nothing quite quickly. In fact, the Skai map does indicate that, but often at the end of the day there wasn’t much time or patience to study it. As we climbed down broken terraces in the dusk again, sure we'd cross one of the little paths from the previous day, monopati-fog clouded my brain. I'd lost track of what was where. But we made it down to the coast via a wired-up gate, just five minutes from home.

Big salads and souvlaki were calling again. Back at Aigaio, the owner was extremely busy but offered us a retsina on the house. He was a Nisyrian who’d spent decades in the US before taking on this business. ‘Four more years,’ he said, before he would retire and spend his days fishing.

Profitis Ilias

In the morning, in the museum I marvelled at the perfection of the Early Bronze Age (2700-2410 BC) cups found in Mandraki and a smooth clay hanging bowl from the fourth millennium BC found in Emborio. Most areas of Nisyros haven’t been excavated. It's only in recent decades that building or ploughing has revealed cemeteries spread over a wide area, spanning many centuries. After the early cremation burials came burials in pithoi jars and later by built graves with marble reliefs.

The nearby island of Yiali, now mined for pumice used in building materials, was inhabited from the fourth millennium BC, principally in the areas where obsidian was found – the black volcanic glass an important material for cutting tools. There’s evidence of stock raising, agriculture, fishing and seafaring, and crucibles for melting copper. Yiali obsidian can be identified by the white flecks it contains – as does the piece I found a piece on a hillside near my house. The smooth hard egg-shaped grindstones of black and grey andesite identified as Final Neolithic appeared similar to ones in my garden.

We’d been here just over a week and planned to leave the next day. It was time to get to the top of the island, Profitis Ilias. At lunchtime, we walked the road up to Evagelistria, then the same beautiful path up Diavatis we’d taken when we went to Nyphios, but turning right and continuing uphill. A Greek man was on his way down - the first person we'd seen on a footpath! - and reassured us it wasn’t far. It was steep but thanks to the excellent path, surprisingly easy. We reached an old chapel and a few ruined buildings with big trees and abandoned terraces, and from there markers vaguely led the way to the trig point at 698 metres.

It was a broad summit covered in once-farmed uplands, the surrounding valleys mostly hidden; but there were magnificent views to blue sea in every direction, the waves turning silver when caught by the wind and surging around little islets. Kos was clear to the north, the Knidos peninsula of Turkey to the east and Tilos to the south. The wind was cold on the peak so we hurried down again, stopping to investigate the start of an intriguing blue-dotted path leading off in another direction...

We’d made it to the top and it was a simple walk back down to Mandraki, where waves were crashing on the shore at sunset. But I still had a hankering to spend some time at Lies beach, and the weather forecast was good for tomorrow. And Ian had a hankering to explore another route to Profitis Ilias, the one we’d started on the first day. So we’d stay one more day.

Lies and Panayia Kyra

I set off just after ten, walking along the coast road with Lisa and letting her into the sea for a dip every now and then as the day was warming up. There wasn’t too much traffic and it was lovely in the sunshine, though it was a real pleasure to leave the main road and descend to peaceful Palli. Except for a handful of people from a yacht having a late breakfast, it was quiet. Cats were having a late breakfast too, eating whole fish outside the bakery. We passed the grand old Pantelidis Baths, with the Roman church of Panayia Thermiani behind it.

Up on Cape Katsounis, with Emborio gleaming on the hilltop above, I got my first glimpse of the empty stretch of coast backed by low hills.

When we reached Lies, after a couple of hours of easy walking around the coast, Lisa rolled in the dry seagrass, ecstatic – we hadn’t had much beach time this week. I found a beautiful spot, relaxed (once the flies stopped biting…), and swam with my mask to see the rising streams of pearly bubbles from breathing holes in the seabed. There were still a few rental cars around, but the sun was warm and it was blissful to lie there and read, cooling off from time to time in the water.

There was still a chance to walk another route home. From the end of the road, I found a track that came to a stop but I scrambled up the slope to another track, winding my way up to Panayia Kyra in the peace and quiet, elated by the landscape as Pachia Ammos came into view far below and I came across old buildings and paths and scanned the ground for pottery.

Ascending into that old landscape, I thought about the joys of walking on history. When I reached the monastery and the track turned into dull white concrete, with no obvious sign of the trail that was marked on the map, I instead picked my way up gentle terraces until I found an old path, overgrown in places, that took me most of the way to the road.

From there it was just a question of following the quiet road - passing a worrying new construction site, alas - until the final bend towards Emborio, were I veered up the shortcut stone path; from the village we took the path along the ridge we’d done the other day back to Evangelistria.

Losing the daylight, from there we took the road zigzagging down, but on the final curve I found the lovely footpath back around the windmill to town. We were only ten minutes behind Ian, who had also achieved his goal and found the blue-dotted trail all the way from near Stavros monastery to Profitis Ilias.

*

The wild and untouched places on these islands are precious. Once you destroy a place, once you build a road, a hotel, it will never be the same again, it's lost forever. It’s something we’ve been thinking about on Tilos, where plans are in progress to concrete the road to Skafi beach, much loved only because of the beautiful route to get there, and the feeling of remoteness. A new road to Mikro Horio has left a big concrete scar across the hillside. There are plans to concrete the lovely, winding dirt tracks to Eristos.

If only the islanders got funding to maintain the centuries-old paths instead, how valuable they would be.

We hadn’t seen anyone else at all out walking except when we went to Profitis Ilias. I also realised I hadn’t had any interesting encounters with people. It must affect the local population, receiving such a volume of day-trippers every day whom they will see for a few minutes and likely never see again.

When I flick through the book of photographs by Peter Kuhne showing Nisyros of the previous four and a half decades, it’s unrecognisable. You’re hard pushed to find a magically cluttered and quirky old shop or kafeneio these days. Though one morning when I asked around for local honey, I was pleased to be directed to the electrical goods shop. All quirkiness is not lost.

On the last morning we went to the ferry ticket office, and there were signs and leaflets for Anaema, the agrotourism organisation which organises walks; I asked about it and discovered the man at the next desk was a partner in it. And when I asked him about the blue-dotted trails that had helped us so much, he smiled and said, ‘I made some of them.’ He and a few locals were trying to revive the old paths. Perhaps we should have met him at the start of the trip... But then finding our way had been part of the fun, too.

As we waited for the ferry, Lisa seemed relieved that we were on our way home. But she'd loved her afternoons of hunting for paths, and her evenings of dinnertime treats. Perhaps she'll also be happy when we go back to explore some more.

October 25, 2022

Walking on Nisyros - Part One

October is an ideal time for walking in the Dodecanese, with the temperatures slightly cooler but the days still mostly sunny with spectacular light. Here on Tilos it’s peaceful and perfect – yet I love to explore other places and walk different routes.

And although it’s barely an hour away by ferry, the volcanic neighbouring island of Nisyros is surprisingly different in its landscape and ecosystem and architecture. After a couple of too-short visits in the past year, I’d promised myself a week in October, and was pleased that Ian felt like coming too. Mostly for his company, of course, though it helps that he’s better than me at finding footpaths and can hold Lisa’s lead when I’m struggling down a steep hillside. He had to work in the mornings but every afternoon we’d be walking.