Jennifer Barclay's Blog, page 4

January 27, 2020

The Aqueduct, Kos

It was October but still hot and summery when I walked out of Kos town towards the Asklepion.On other occasions, in other directions, I'd found too much fast traffic on the main roads, and ferocious guard dogs on the back roads scared Lisa. This time, I found that from the Casa Romana there was a pavement along the road. We followed it as far as the Jewish cemetery, a memorial to those who were taken away to their deaths in the final months of World War II. Then we detoured on a track through an olive grove into the Turkish village of Platania. There was sprayed graffiti on the old fountain. I continued uphill on a quiet road until there were cypresses growing either side. I’d had vague thoughts of re-visiting the Asklepion, the ancient hospital of Hippocrates, but neither the attendant nor the cats were very welcoming to me and Lisa. So I walked on, catching glimpses of the site through a fence. Then, a little way beyond, we came to an intriguing stone tower. Wandering off the road to investigate, I found sections of an old aqueduct.

It was October but still hot and summery when I walked out of Kos town towards the Asklepion.On other occasions, in other directions, I'd found too much fast traffic on the main roads, and ferocious guard dogs on the back roads scared Lisa. This time, I found that from the Casa Romana there was a pavement along the road. We followed it as far as the Jewish cemetery, a memorial to those who were taken away to their deaths in the final months of World War II. Then we detoured on a track through an olive grove into the Turkish village of Platania. There was sprayed graffiti on the old fountain. I continued uphill on a quiet road until there were cypresses growing either side. I’d had vague thoughts of re-visiting the Asklepion, the ancient hospital of Hippocrates, but neither the attendant nor the cats were very welcoming to me and Lisa. So I walked on, catching glimpses of the site through a fence. Then, a little way beyond, we came to an intriguing stone tower. Wandering off the road to investigate, I found sections of an old aqueduct.

I passed through a fence keeping goats in and descended into a pebbly riverbed with a stream still just about flowing although it hadn’t rained for six months. Lisa sat gratefully in a pool after the heat of the walk.

We continued until we reached a narrow waterfall over a dam, where the ruins of a watermill stood, a stone inscribed with ‘1955’. This place could have been used from ancient times until sixty years ago.

We continued until we reached a narrow waterfall over a dam, where the ruins of a watermill stood, a stone inscribed with ‘1955’. This place could have been used from ancient times until sixty years ago.

I sat on a rock with streams flowing slowly on either side, listening to the trickling water, watching blue and red dragonflies dance about, until little green frogs tentatively surfaced beside me.

Then we returned to Kos town on a slightly different route, having discovered another deserted place.

Then we returned to Kos town on a slightly different route, having discovered another deserted place.

Published on January 27, 2020 10:42

August 21, 2019

A ROPE OF VINES, PANAYIOTA AND MORE

When I lived in Athens in the early 1990s, working as a teacher of English, I spent a couple of winter weekends on the island of Ydra (Hydra). The first time, while walking around the coast I met an older Greek man with a large moustache. He turned out to be a sculptor and paid for me to change my ferry ticket so we could travel back to Athens together – which we did, playing tavli (backgammon) on deck as the sun went down.

We were friends for a year. Many a time, recovering from my latest heartache, I wanted someone to take me home and look after me; and that’s what he did, lending me his t-shirts to sleep in and making me peppermint tea in the morning. I’m sorry I lost touch with him.

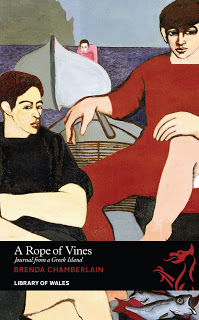

I recently read Brenda Chamberlain’s A Rope of Vines: Journal from a Greek Island, written in the early 1960s by the Welsh writer and artist. When someone first told me about the book, he said Chamberlain was always falling in love with unsuitable men, then taking herself off to a convent for a few days to recover. I was intrigued, and frankly hoping for a few tips and directions to the convent.

I was soon hooked by Chamberlain’s personality, her artistic sensibility. From the first paragraphs of her introduction we know her new friend Leonidas is serving a sentence for manslaughter of an English tourist – and that, sequestered among the nuns to contemplate life and pray for him, she can ‘take a siesta in a juniper tree’ if she feels like it.

The island was then more populated than now, with 3,000 souls. One of them must have been Leonard Cohen, who had arrived as an unknown poet in 1960. The expat community of artists and writers on the island in those years including Australian writers George Johnston and Charmian Clift, who had started out on the Dodecanese island of Kalymnos but found it too remote, and preferred Ydra for its proximity to Athens and for its literary associations; Henry Miller and Lawrence Durrell had lived there in the 1930s. In the 1950s it was a hotspot for filmmaking, drawing Sophia Loren, Melina Mercouri, Brigitte Bardot.

Chamberlain doesn’t mention any of them, although perhaps it was this too that she was escaping when she spent her days living up near the wells, with the nuns. She says:‘International travellers throw an unreal glamour over the port, but step out of the harbour and you will come upon club-footed boys, women withering with the sun’s luminosity, mal-fed children grossly fat, dwarfs with sun-smitten faces.’

It’s a clear-eyed, unsentimental journal and yet filled with beauty of the austere high places, ‘breeze, and heat, and golden promontories’, fresh-caught fish that she guts with a broken-handled knife, people harvesting wheat while others scream at one another, spiders’ webs like steel wires. She wants to be more like the nuns and live in the Spirit alone, patient and secure, but cannot.

‘I am for ocean, the tumult of Thalassa…for black-skinned seamen bearing baskets of coral…’

There is much darkness in the journal, and in the sea in her mind. She also writes of ‘fire-gleaming, passionate waters… Light-filled depths…’ Thalassa is not blue but ‘Indigo, green of jade, white, silver, black.’

The cover is a gorgeous painting by the author showing dark-eyed fishermen returning with a catch. The text is scattered with her spare, evocative line drawings. She reminds herself to hold on to the clarity of vision induced by disaster, to try to be wiser through suffering. The book was written during her first few years on the island. She died only six years after publishing it, at the age of 59, after returning to north Wales. According to online sources, it was from an overdose of sedatives.

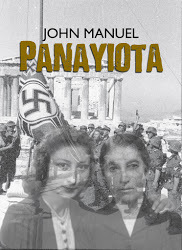

Also over this summer I received a book about Greece in a different style, Panayiota, a novel by Rhodes-based writer John Manuel. The novel is loosely based on what he learned of his wife’s family background, set against well researched real events.

It takes place partly in contemporary times in a hospice in Bath, England, and partly in wartime Athens – when 40,000 people died in the city from starvation alone, quite apart from executions and shoot-outs.

The heroine of the tale is Panayiota, born in 1925 into a family who ran a taverna in the Plaka district under the Acropolis – a merry place to grow up with the sound of traditional musical instruments played under the influence of ouzo or tsipouro or retsina. The city was still a collection of villages, and everyone had a bit of land with some oranges and olives and vegetables. Panayiota has a happy childhood; ‘we’d hear our fathers and grandfathers arguing about Italians and the refugees from Turkey and stuff, but we were more interested in having a good time’. The city was full of life.

This all changed in April 1941 when the Germans bomb Piraeus, hitting a British ship, and that is more or less where the story begins, telling of the following dramatic years with their terrors and moments of joy. Manuel gives fascinating insights into an extraordinary era.

Which reminds me: Doug Gold’s book The Note Through the Wire, already a number one bestseller in New Zealand, will be published in the UK next spring. Doug’s book is also based on his wife’s family story, and part of it gives a vivid description of the Kiwi protagonist’s experiences fighting in the ill-fated Greece campaign and escaping in the Peloponnese. Injured, he was eventually captured and taken as a prisoner-of-war to Slovenia, which is where the love story with resistance fighter Josefine begins.

Which reminds me: Doug Gold’s book The Note Through the Wire, already a number one bestseller in New Zealand, will be published in the UK next spring. Doug’s book is also based on his wife’s family story, and part of it gives a vivid description of the Kiwi protagonist’s experiences fighting in the ill-fated Greece campaign and escaping in the Peloponnese. Injured, he was eventually captured and taken as a prisoner-of-war to Slovenia, which is where the love story with resistance fighter Josefine begins.

And that reminds me about The Lost Lyra by Richard Clark, about a friendship that begins between an escaping British soldier and a resistance fighter in the mountains of Crete. Yet another gripping read.

Finally, John X. Cooper’s The Sting of the Wasp is a contemporary thriller set in Athens against the memories of the Civil War. His new book, Dead Letter , also featuring detective Panos Akritas, was launched on Kindle at the start of the summer. To enter a competition to win a copy of the Kindle edition, please share this post somewhere and let me know.

Happy reading.

Published on August 21, 2019 06:13

July 16, 2019

It seemed like the beginning of a damn good story…

An interview with John X. Cooper (born Yianni Xiros) about his new novel Dead Letter – and two excerpts from the book

The ruins of Rhamnous, the ancient city just north of Athens, where Akritas is pursued by assassins

Why did you decide to set Dead Letter in contemporary Athens?

I taught English literature at the University of British Columbia for many years and when I retired I thought I’d finally get to read all those books that I had referred to many times in lectures and my academic writing but never actually read from cover to cover. One of those books was the Bible. So, I started with Genesis, Chapter 1 and worked my way through to the final chapter of Revelations. There was an episode in Acts of the Apostles (Chapter 17: 16-34) that really caught my attention.

It was St. Paul’s visit to Athens in 51 AD, when the news of Christianity arrived in Athens. I was amused by the reaction of the pagan philosophers, Epicureans and Stoics, to Paul’s message. They dismissed it as the ramblings of a lunatic. I remember thinking that not much had change in the sceptical attitudes of Athenians in 2000 years.

But later I wondered why Paul had never written one of his famous letters to the Athenians. Why did the Corinthians, Thessalonians, Philippians, and others receive epistles from Paul but not Athens? Then it occurred to me that perhaps he had written such a letter, but it was lost, or better still, it was suppressed. What if someone in contemporary Athens found it in the National Library and then was murdered? It seemed like the beginning of a damn good story.

Raphael’s picture of St. Paul preaching to the Athenians

What is your own connection with Greece?

I was born Yianni Xiros in the Kypseli neighbourhood of Athens and lived there with my parents for the first few years of my life. My parents divorced when I was five and my mother left Greece with me in tow for Bergamo in Italy where her brother was in business. We lived there for two years until she met Norman Cooper. He was British and his sister was married to my mother’s brother. They fell in love, married in the UK, and after a two-year sojourn in his family home in Sussex, we immigrated to Montreal in Canada. In 2013 when I retired from my academic post I returned to Athens to reconnect with my roots and now I spend periods of time every year in Canada, the UK, and Athens.

The old National Library on Panepistimiou Street. The archives of the Library have now been moved to a new facility in Kallithea.

Who is Panos Akritas?

Panos is a captain in the Hellenic Police (the Astynomia Elleniki) with its headquarters in the big police building on Alexandras Avenue across from the Panathinaikos football stadium. Akritas is the family name of a medieval Greek warrior who is the subject of a well-known epic poem from the 10th century AD. The poem called Digenis Akritas Basileios tells of the heroic exploits of this warrior in defending the eastern borders of the Byzantine Empire against invaders from Central Asia. The folksongs that also tell of his exploits are called the Akritic ballads and are collected as the Akritika: Odes of the Byzantine Border-Guards. Akritas seemed like a good name for a modern day policeman, not defending the borders of an empire of course, but perhaps policing different kinds of borders. His first name came to me when I was having a coffee at the Dioscouri café in Plaka that overlooks the east side of the Agora. One of the streets nearby is called Odos Panos. When I saw the small blue street sign it was love at first sight.

A medieval depiction of Digenis Akritas in action

Are you a fan of any other crime/detective novels set in Greece?

I’ve read a couple of novels by Petros Markaris and several by the Anglo-Greek writer Anne Zouroudi. Both are very good. There are others, but I must confess I’m a big fan of the Italian crime fiction writers, the Neapolitan Maurizio de Giovanni, for example, or the Sicilian Andrea Camilleri, the British writer Michael Dibden whose crime novels are set in various cities in Italy, and the American Donna Leon who has Venice as background for her Commissario Brunetti novels.

What made you start writing crime fiction?

Some years ago my wife thought I might like Camilleri’s Montalbano novels. I did, very much and I ended up binge-reading them. But Dibden was my immediate writerly inspiration. Although he’s British he manages to convey his Italian stories and characters in a remarkably vivid way. I also liked his take on Italian society and manners. I remember thinking I could do the same thing for Athens and although I’ve spent most of my adult life elsewhere, I was actually born there.

What was the inspiration for your first novel, The Sting of the Wasp?

One of the first things that struck me when I returned to Greece in 2013 was how the Greek Civil War from 1946-1950 was still present in so many ways, small monuments, history texts, people’s memories, and political discourse. Although Sting of the Wasp is not mainly about the civil war it was what got me thinking about the plot that eventually made up the substance of the novel.

Small monument near the police headquarters on Alexandras Avenue put up by the Greek anti-Nazi partisans and communists to remember the “December days” in 1944, which was a prelude to the Civil War that broke out a year later

What do you hope readers will find in your work? What is your favourite reader comment so far?

I want to write about the real Greece, not the tourist brochure Greece. The city of Athens is a fascinating and complicated place and it seems to me that writing about its reality gives both Greeks and non-Greeks a more vivid picture of what’s it’s like. My favourite reader comment came from an American who read Sting of the Wasp and wrote to say that when he finally visited Athens my book had given him a better appreciation of the place.

Are you writing something new? If so, can you tell us anything about it?

My new Panos Akritas mystery is called Three Sisters and it involves the murder of a renowned chef who owns a two Michelin star restaurant in wealthy Kifissia and is found stabbed to death with one of his own kitchen knives. All the evidence points to his youngest daughter Zoë. But Captain Akritas has his doubts. I think, more than anything else, it's a novel about appetite. Enough said.

In Dead Letter, Panos is dreaming of his Greek island holiday. Is that something you do?

Yes, absolutely. I love the Ionian islands, Cephalonia, Zante, Corfu and so on. In the Aegean, I tend to stay away from the very touristy islands. I like Sifnos because of the food and great atmosphere. Folegrandos in the Cyclades is relaxed and not crowded. I’d love to visit Rhodes in the future and your island too, Jennifer, Tilos.

Thank you! And now for two excerpts from Dead Letter:

1: Pursued in the ruins of Rhamnous

After a few minutes he saw them. Four men in a line with MP7 type submachine guns, picking their way carefully up the slope. Here they come, he thought. He was on their left. If he stayed where he was, the point man would pass fifteen metres from his position. Too close. He needed to move. But where? Staying low, he moved at an angle further to their left. He kept the buckthorn bushes and stunted trees between him and his hunters. He found a hollow with some cover.

When the men had passed, he set off towards what he assumed were Kato Souli and Schinias. “Not sure where the fuck I’m going,”he murmured to himself. He was sweating profusely as the sun’s rays came at him like an attack of razor blades.

When he reached the church, he rested. It was past noon, so the east side gave some relief from the sun. Problem was he couldn’t spot his pursuers from there. As time passed, he lost all sense of their movements. He listened for sounds but the cicadas were putting up such a racket that he might as well be deaf. Why wouldn’t they search the vicinity of the church? Of course they would. He realised that they would not think he was in the church. Killing him would be too easy there. But would they have to check just to make sure? They’dcertainly come around to his side eventually. Before that happened, he would have to move. But where? Straight ahead and slightly to his left there was thick underbrush, large boulders and small gnarled trees. They wouldn’t give much cover but it was better than cowering by the church wall awaiting his executioners. If they were smart they’d come round both ends, hoping to trap him in the middle. He knew he had to move. Now.

He sprinted straight for the underbrush and dived in before anyone rounded the corners. He hid himself in the bushes as well as he could and watched the church wall where he’d been resting. He didn’t have long to wait. The four men split up and two suddenly appeared at each end of the wall,guns in firing position. They looked around at the surrounding shrubs and trees. One said something and the four walked carefully to the front of the church. It looked to Akritas that they entered. This was his moment to escape. He broke cover and was at least a hundred and fifty metres from the church when the four men emerged, glanced around, and waited. They hadn’t seen him. Akritas was hidden among shrubs and rocks. He let out his breath when he saw them confer and head off in a different direction, guns ready. He rose crouching and began to creep crab-like away from the church towards the east.After an hour, he came across what looked like an ancient marble wall set in the hillside. He looked around. It was obviously an archaeological site, although it was clearly not being excavated,had not been excavated for several years. “Fucking Euro crisis,” he said out loud to a stunted cypress tree nearby. The heat’s getting to me. I’m talking to the fucking trees. “Rhamnous,” he said under his breath, the acropolis of Rhamnous.

2: The bonds of friendship

The next night, Katarina, her sister, Greg and Katia, Valia and Akritas reserved a big table at Rythmos Stage, a club in Ilioupoli, a south Athens suburb. They heard a Cretan band, Chainides, play the superb and inspiring music of that ancient island with wonderfully wry political commentary by the leader, Dimitris Apostolakis, who also did duty on the Cretan lyre. They played until past two in the morning to a packed house. It was a foot-stomping good time. It was defiant, funny, sad, and the entire audience realised somewhere around one o’clock they all shared something in common. Not only a love of their country’s music, or the joyful fellowship of comrades even if it was only for a few hours, or even everyone getting tipsy together on the wine, the beer and the Cutty Sark, not only those things, but something more important. Katarina mentioned it in her thoughtful way as they drove back to the centre. They were a people and they all shared a common fate. It was the truth of what it means to be a nation. The poignancy was not lost on them after six long years of the debt crisis.

As they drove into the centre, the six friends were not ready for the evening to end. It was now about three in the morning. As it was the end of July, the night was warm and many people were still out talking, drinking and just happily walking about. Living joyfully was not yet a dead letter among the Greeks even in a dark time. Akritas suggested the St George terrace in Plateia Karytsi for a nightcap. It would be quiet there under the walls of the big church. When they arrived, the bar was closing, but the very small café next door was still open. Akritas and Greg pulled a couple of tables together so that the friends could all sit as one. The walls of the church reminded him of St Paul and his crisis of faith. That moment is one we all must face in our different ways. Even a nation must face doubt when it loses faith in itself. But perhaps only for a short time.

Dead Letter

Sting of the Wasp

Published on July 16, 2019 01:25

July 4, 2019

Onions to Arki, Watermelons to Marathi

‘Manoli?’ I ask.

‘Jennifer,’ he says. ‘The girl with the dog.’ The girl with the dog has had breakfast and is doing a bit of work and a bit of planning.

I tell Manolis, the owner of Trypas taverna where I’m staying, that I’m thinking of taking the boat to Samos tomorrow to get cash and dog food and a notebook, none of which is available here on the little island of Arki. Manolis is very laid back, a man of few words, completely belied by the way he dresses: flip-flops, board shorts, panama-style hat, scarf around his neck and a different, brightly patterned, well-pressed shirt at least once a day. I asked him earlier how many shirts he owned, and he just laughed.

I arrived on Arki in the north of the Dodecanese four days ago, with the intention of staying two or three days. I stayed a little longer to do my research, because the local people are less talkative than in some other places. But I have, truth be told, found out all I really need to know about this island with about forty permanent residents and an area of about two and a half square miles. The thing is, every time I think I might leave, I find myself sitting on a beach, mesmerised by the sea. It’s such a quiet, easy place to like, with its little stone huts around the harbour where the fishermen sit, its gently undulating hills covered in green bushes and golden yellow grasses, the sound of goat bells above the village where the fantastic local cheese is produced, which the tavernas put in their salads.

The lack of cash is not really a problem yet, as everything is on the ‘pay later’ system. Paying on the same day is generally seen as a bit over the top. As Stephanos told me last night, ‘We are Greeks. Real Greeks.’ But eventually I’ll have to settle my bill. The lack of dog food to buy has been somewhat expensive, although Lisa has been perfectly happy eating tinned ham, chicken souvlaki or meat balls. She’s made it clear that she’d rather go hungry than eat the Purina dry food I brought. If I’m sampling the good local food, so will she. The diet starts tomorrow...

The lack of cash is not really a problem yet, as everything is on the ‘pay later’ system. Paying on the same day is generally seen as a bit over the top. As Stephanos told me last night, ‘We are Greeks. Real Greeks.’ But eventually I’ll have to settle my bill. The lack of dog food to buy has been somewhat expensive, although Lisa has been perfectly happy eating tinned ham, chicken souvlaki or meat balls. She’s made it clear that she’d rather go hungry than eat the Purina dry food I brought. If I’m sampling the good local food, so will she. The diet starts tomorrow...Anyway, Manolis asks, ‘Why don’t you take the boat to Lipsi today, the Lampi? You have one hour there to do what you need to do and come back.’

I didn’t know there was a boat to Lipsi today. Another thing that doesn’t exist on Arki is a boat schedule, except by asking a local; perhaps because most people arrive by their own boat anyway. I scribbled down the surprisingly extensive schedule in the back of my notebook listening to Manolis the other day, and it didn’t feature this one. I ask him when it leaves, and it’s in twenty minutes. I thank him and dash to my room to grab my bank card, then hurry down to the port.

It’s rather confusing but there is the old harbour and the new ‘port’, a small concrete dock, which according to a sign for a taverna there is a seven-minute walk. Next to it is the lovely main beach where I swam this morning, where residents have sprayed onto a boulder, ‘No Camping’ and underneath, ‘Sorry.’ At the taverna on the port I find my new friends from Athens with their lovely dog and we get chatting. They check with the lady from the taverna if they will sell dog food on Lipsi.

‘I think so.’

‘Yes,’ I say, ‘it’s a big island.’ Then I laugh. When I stayed on Lipsi almost three decades ago, I couldn’t imagine a quieter, tinier place. Now, it feels like going to the big city. But the lady realises that I’m planning to go today.

‘The Lampi doesn’t go today – the only boat was this morning.’

There is certainly no one else waiting for it, and no sign of it coming. It seemed too good to be true. I continue chatting with the couple from Athens about this and that.

And then – a little ferry approaches fast that must be the Lampi. Great! But it goes straight past the dock and is undoubtedly heading at a fast pace for the old harbour. Confirming with the locals it is going mesa, inside to the harbour, I set off at a sprint. Lisa thinks this is a great game. I am soon out of breath – it seems that I am a little out of shape from being on a miniature island – but I have to keep running to catch it…

I arrive, panting, as some boxes are being loaded and unloaded, and Lisa and I make it onto the boat and it soon sets off. We cruise into the archipelago of tiny islets. The only other passenger, a nervous Eastern European girl with a suitcase, gets off at Marathi – I guess she is going to work at the taverna in the summer. Marathi is even smaller than Arki, with expensive yachts moored around the beach. From there on, I have a private cruise to Lipsi. We approach around the northwest of it, which seems mountainous and forbidding after Arki. I ask the young guy who is crew about the boat schedule, and he says today’s was a special service. About an hour after we set off, the town comes into view and it feels strange to see roads and street signs, and a petrol station – this must be where people from Arki get their petrol, if they need it (there are only a couple of cars).

We hop off the boat and I have one hour to do my errands. I put my plastic bottles into the famed recycling bin. I spot the Alpha Bank, one of the three branches that was almost closed down last year. I find a bakery and marvel wide-eyed over an array of products that includes wholegrain tahini and Lipsi wine and carob paximadia. I buy enough dog food to start my own specialised minimarket on Arki. Then, bags bulging, I make my way back to the boat, which is waiting with just one other passenger destined for Marathi. ‘Shall we go?’ the crew asks the captain. We are transporting a few boxes of fresh fruit and vegetables, wrapped up with tape and labelled by hand: onions for Arki, watermelons for Marathi.

Published on July 04, 2019 06:25

June 22, 2019

A Footpath to Tristomo

Anna, the proprietress of the taverna at Avlona, is wearing what looks like a flowery nightgown over her dress and bulky frame, and tells me to take off my glasses as she didn’t recognise me with them on. ‘How long have you been here? How long are you staying?’

Having lived in the north of Karpathos for a year and a half, I know people and it’s one good reason to go back. But the other reason this time was to walk from Diafani to Tristomo, in the very north of the island, then back via Avlona to Diafani. We’re carrying backpacks as I’d planned to camp, though it didn’t quite work out like that. We met some of Anna’s cousins instead. They almost made us bring a goat with us this morning, all five hundred metres up to Avlona. It was already hard enough. Greetings complete, we sit down to order drinks and food. I feel a huge sense of satisfaction after the walk.

Tristomo is a natural harbour, a long protected inlet almost cut off from the open sea (with three mouths, hence the name: treis-stoma), and was therefore always an important place when people got around mostly by boat. The area has been virtually deserted for decades, only reached by private boat or on foot, though threatened recently by the possibility of a road. I knew it would be safer not to go alone, and luckily Ian – who hadn’t been to Karpathos for years – was keen to join me and Lisa.

From the ferry, Ian agreed it looked impossible that there could be a decent path along that sheer mountain that seems to fall into the sea. We took a lazy recovery day, wary after the experience on Halki, the day after the corned beef and mosquitoes camping extravaganza; the day where the sketchy path turned into no path at all, and we ran short of water on a hot afternoon with a long way still to go, and were saved by a cistern. A story for another time, that one. In Diafani, I asked around about the condition of the path from Diafani to Tristomo, knowing that roads were severely damaged in the rains this winter. An old lady said, in a Greek variation of the Irish joke, ‘Don’t go from here, go from Avlona!’

I called Minas, and he called another Minas, who confirmed the path had been cleared and marked recently. We set out this time with vast amounts of water, drinking lots of it the night before. And we were blessed: the path was excellent, a gentle breeze mitigated the late May heat, and the landscape was magnificent, with mountains to one side and deep blue sea to the other, and pine trees for shade.

As we approached Tristomo, it was clear that this was a special place, the whole area peaceful and wildly beautiful, a piece of the world where time stopped.

Around the bay itself, a few houses have been restored by the owners, while others are crumbling into the sea. I knew this, and know some of the owners. What I didn’t expect was to be welcomed like guests and invited to eat fresh calamari by a newly married local couple called Marina and Andreas who had a house there. They gave us as much cold water as we could drink from their tank, saying they liked to help people who had walked there, offered us a place stay in a house with the waves lapping around, and regaled us with stories into the night.

Marina was consumed with laughter as she told us about a couple who came to stay once. Tristomo is a fairly rugged and remote place, needless to say, and her husband Andreas was hesitant but at last agreed. The man was a colleague of Andreas’, and he worked with him on ships. The man’s wife also worked on ships, so it came as a surprise when she got seasick during the crossing from Diafani and refused to go back by boat. It wasn’t quite clear how she expected to leave otherwise, because they also had their toddler with them. By donkey, perhaps?

The husband, meanwhile, had brought every gadget known to man – he arrived wearing an action camera strapped around his head – and was frustrated that there was no phone signal and, moreover, nowhere to charge his devices, given that Tristomo has no electricity. Their visit had got off to a good start, clearly, but it would get worse when they somehow made it back to Olympos and found the rabbit.

A huge rabbit had been making its home around their buildings for some time, and an opportunity arose for Andreas to finish it off and put it in the pot. But he needed something to use as a weapon, and he needed it fast. He asked his friend if he could use his spear gun. The guy hesitated and said he had to ask his wife for permission – but he was scared to ask because his wife was against hunting animals. So Andreas had to call the guy’s wife and ask her on behalf of his friend for permission to use the spear gun. The wife replied that he could use it, but only if her husband didn’t watch.

At this point in the story, which Andreas and Marina told very well while topping up the wine, we were all falling about giggling. Marina, in tears of laughter as she lit another cigarette, summed up the only possible cause for such uptight behaviour. ‘I think no sex. Or shitty sex.’

Andreas and Marina insisted we join them for breakfast the next day – cheese preserved in olive oil, made by his mother, and local bread rusks – then we explored the old settlement at Kilios before making our way up the mountain on a solid old stone footpath.

We’d almost reached the top when we were astonished to meet two more people: one Cypriot, one Spanish, cheerful guys carrying just a daypack between them, tripping down the path fresh as daisies. They planned to go down to Tristomo in twenty minutes or so and be back in Avlona to join their friend for a late lunch. Thinking perhaps they were extremely fit and young and that maybe we were walking excessively slowly to take photographs and notes, we wished them well.

Now, our lunch has arrived. I’m a little sad to see bottled water. But the heaped Avlona salad and artichokes with eggs go down well. There’s a rather rotund tourist letting a cat lick his plate clean, making phone calls to friends and ordering more food. As we finish and prepare to leave, the guys appear looking a little less fresh than last time, and stagger over to join their friend. Apparently Anna had told them it was only a couple of hours there and back.

‘She lied!’ whispers the Cypriot.

A few days later, we are leaving Karpathos after an extraordinary week of walks and seeing friends, and will walk from Olympos down to Diafani for the ferry. When we took the main footpath up, it had been badly damaged by the winter rain, and still had a waterfall even in late May. In any case I’d like to try the alternative path via Ayios Konstantinos, another one I’ve never done before.We get directions from friends in Olympos, but there isn’t much in the way of landmarks around here – it’s all mastic bushes and pine trees and rocks – and the day is hot and our backpacks heavy as I have stuff to take back to Tilos. However, we find a path and it’s a beautiful one through unspoiled green hills.

The chapel is lovely, and a mouse lives in a hole in the wall. In the valley, the stream still flows. It doesn’t seem a long walk. We arrive back at Diafani, aim straight for the beach and jump into the sea to cool off.

The chapel is lovely, and a mouse lives in a hole in the wall. In the valley, the stream still flows. It doesn’t seem a long walk. We arrive back at Diafani, aim straight for the beach and jump into the sea to cool off.There’s the sound of a big engine. I’ve just got out of the water when Ian shouts that the ferry is approaching. I throw my clothes on over my bikini and half-run all the way to the dock, laughing. We’re soon up on deck, passing the cliffs and wondering how there could possibly be a path to Tristomo that way.

Published on June 22, 2019 06:33

May 26, 2019

Island-Hopping on Wild Halki

The little island of Halki is a useful stopover on the way from Tilos to the north of Karpathos. It’s less than an hour on the Dodekanisos (a.k.a. ‘Spanos’) catamaran to Halki, where two days later you can pick up the big old Anek Preveli for a leisurely couple of hours’ ride to the port of Diafani, and the whole journey costs just over twenty euros. Accommodation on Halki can be expensive, however; dog-friendly accommodation is particularly tricky, but luckily I found a new apartment available on Airbnb for a good price. For the first night, however, we’re heading to Pefkia to camp for the night. Wild camping is generally acceptable as long as you’re out of sight and leave nothing behind. Beyond the harbour, Imborio, Halki has a surprising wealth of wild, deserted places.

The little island of Halki is a useful stopover on the way from Tilos to the north of Karpathos. It’s less than an hour on the Dodekanisos (a.k.a. ‘Spanos’) catamaran to Halki, where two days later you can pick up the big old Anek Preveli for a leisurely couple of hours’ ride to the port of Diafani, and the whole journey costs just over twenty euros. Accommodation on Halki can be expensive, however; dog-friendly accommodation is particularly tricky, but luckily I found a new apartment available on Airbnb for a good price. For the first night, however, we’re heading to Pefkia to camp for the night. Wild camping is generally acceptable as long as you’re out of sight and leave nothing behind. Beyond the harbour, Imborio, Halki has a surprising wealth of wild, deserted places. Pefkia is somewhere I discovered after another wild camping night last year. Waking early in my hilltop hideaway, I’d made my way across to the flat area on top of the headland and found ancient remains, which I later learned were the remains of temples dedicated to the god Apollo. I suggest it as a place to camp before setting off the next morning to see the hermits’ cells at Kelia with frescoes from the ninth and tenth centuries. Ian agrees that it sounds a good adventure, and Lisa – well, our canine companion doesn’t have much choice but to go along with the plan.

It’s a clear evening, with views across the sea to the south of Rhodes and the north of Karpathos. Along the mountainside are old terraces. Dogs bark, cocks crow, and shepherds shout as they round up animals, their bells clanking. The start to the path is unmarked and hard to find. Rough and overgrown, it follows a wall and then the terraces above an area of pine trees, then up over rocks towards an old stone shepherd’s hut and juniper bushes with green berries. There’s a cool wind and it’s rockier than I remember, so we choose a place under a wind-bent Mediterranean pine, its needles softening the ground, with a touch of shelter from the dry-stone walls around. To save on weight for hiking, I’ve left the tent behind and have just a mat and sleeping bag. The mountain of Attavyros on Rhodes is now grey, the sea pale blue, the sky changing to mauve with a streak of white cloud. By the time Ian has finished taking photographs and we’ve cleared the camp site of the worst rocks and are drinking raki, dusk is falling. Lisa’s sitting on a wall, alert for goats. We listen to the scops owls’ reedy high-pitched calls, like a short note played on a wooden recorder or whistle over and over. The picnic we’ve brought is, frankly, a bit messy. We’re used to camping on a beach where it’s easy to wash in the sea, and we have limited water supplies for the next day. The chunk of graviera cheese is delicious but oozing after being out in the heat all day. I steer clear of the sardines and olives. Ian has decided that this would be a good day to try corned beef for the first time. I help him open the can, forgetting that it too has been out in the heat, and grease spills all over my hands. He takes a mouthful of the warm meat paste, decides he hates it and that I should feed it to Lisa. It does smell a bit like pet food.Meanwhile, the wind has completely dropped, and we are plagued by a surprising number of mosquitoes considering we are up on a headland hilltop. Because of the wind and position, we didn’t bother to rig up the net and although I throw a rope over the branch above to hang it from, the positioning isn’t ideal to cover all the bases. The ‘natural’ mosquito repellent makes me feel sticky but doesn’t deter the buzzing and biting. We turn in early, at which point I find my new sleeping bag is way too hot, and Ian’s new inflatable sleeping mat makes loud noises every time he moves. I long for my tent, cannot settle and eventually move off to sleep fitfully on a sloping but smooth-ish rock which catches a bit of breeze.

It’s a clear evening, with views across the sea to the south of Rhodes and the north of Karpathos. Along the mountainside are old terraces. Dogs bark, cocks crow, and shepherds shout as they round up animals, their bells clanking. The start to the path is unmarked and hard to find. Rough and overgrown, it follows a wall and then the terraces above an area of pine trees, then up over rocks towards an old stone shepherd’s hut and juniper bushes with green berries. There’s a cool wind and it’s rockier than I remember, so we choose a place under a wind-bent Mediterranean pine, its needles softening the ground, with a touch of shelter from the dry-stone walls around. To save on weight for hiking, I’ve left the tent behind and have just a mat and sleeping bag. The mountain of Attavyros on Rhodes is now grey, the sea pale blue, the sky changing to mauve with a streak of white cloud. By the time Ian has finished taking photographs and we’ve cleared the camp site of the worst rocks and are drinking raki, dusk is falling. Lisa’s sitting on a wall, alert for goats. We listen to the scops owls’ reedy high-pitched calls, like a short note played on a wooden recorder or whistle over and over. The picnic we’ve brought is, frankly, a bit messy. We’re used to camping on a beach where it’s easy to wash in the sea, and we have limited water supplies for the next day. The chunk of graviera cheese is delicious but oozing after being out in the heat all day. I steer clear of the sardines and olives. Ian has decided that this would be a good day to try corned beef for the first time. I help him open the can, forgetting that it too has been out in the heat, and grease spills all over my hands. He takes a mouthful of the warm meat paste, decides he hates it and that I should feed it to Lisa. It does smell a bit like pet food.Meanwhile, the wind has completely dropped, and we are plagued by a surprising number of mosquitoes considering we are up on a headland hilltop. Because of the wind and position, we didn’t bother to rig up the net and although I throw a rope over the branch above to hang it from, the positioning isn’t ideal to cover all the bases. The ‘natural’ mosquito repellent makes me feel sticky but doesn’t deter the buzzing and biting. We turn in early, at which point I find my new sleeping bag is way too hot, and Ian’s new inflatable sleeping mat makes loud noises every time he moves. I long for my tent, cannot settle and eventually move off to sleep fitfully on a sloping but smooth-ish rock which catches a bit of breeze.

The morning is serene, however, with a golden light on grey walls and pines and junipers and mastic bushes, the only sounds a few goat-bells and the distant engine of a boat going out. The sky is pale blue with a few tiny clouds. None of us has slept much but I’m keen to set off while the day is fresh. From the flat field near the ancient marbles, we pass through a gap in the wall and follow what is barely a path along a hillside of rocks, bushes and scrub, with the deep blue sea far below down and views across to Symi and Turkey. There is no-one around, but plenty of signs that this steep land was once cultivated, with faint old stone terraces.

The morning is serene, however, with a golden light on grey walls and pines and junipers and mastic bushes, the only sounds a few goat-bells and the distant engine of a boat going out. The sky is pale blue with a few tiny clouds. None of us has slept much but I’m keen to set off while the day is fresh. From the flat field near the ancient marbles, we pass through a gap in the wall and follow what is barely a path along a hillside of rocks, bushes and scrub, with the deep blue sea far below down and views across to Symi and Turkey. There is no-one around, but plenty of signs that this steep land was once cultivated, with faint old stone terraces.  Round shepherd’s huts on the hillside above blend in with the stones all around, so often the only way to make them out is the black rectangle of a doorway. When we stop to examine a tiny hut or kyfi, there is silence except for waves far below and birds unseen around us, and Lisa already panting in the shade. Below, the sea is now turquoise and a flat coastal strip gradually comes into view as we progress, with very faint lines of threshing circles and walls, maybe a church. There’s no marked path, so we simply continue along the hillside. We negotiate our way around an enclosure with thorn bushes and broken rusted fencing, then cross a gully with oregano, butterflies, and euphorbia that has dried to crimson. I hope that we are descending to Kelia to see the hermits’ cells, but the stupendous sheer cliffs of the canyon soon tell me it’s Areta. We must have missed the descent we were aiming for. The spirits of the hermits didn’t want to be disturbed.

Round shepherd’s huts on the hillside above blend in with the stones all around, so often the only way to make them out is the black rectangle of a doorway. When we stop to examine a tiny hut or kyfi, there is silence except for waves far below and birds unseen around us, and Lisa already panting in the shade. Below, the sea is now turquoise and a flat coastal strip gradually comes into view as we progress, with very faint lines of threshing circles and walls, maybe a church. There’s no marked path, so we simply continue along the hillside. We negotiate our way around an enclosure with thorn bushes and broken rusted fencing, then cross a gully with oregano, butterflies, and euphorbia that has dried to crimson. I hope that we are descending to Kelia to see the hermits’ cells, but the stupendous sheer cliffs of the canyon soon tell me it’s Areta. We must have missed the descent we were aiming for. The spirits of the hermits didn’t want to be disturbed.

Published on May 26, 2019 01:30

April 30, 2019

Easter, Neighbours and Old Stone Walls

The sun set on Easter – rather spectacularly, with golds and pinks and pale blues. Greek Easter is done and dusted for another year, though it won’t be truly over until the last firecracker has resounded like a gunshot, breaking the silence that reigns during these warm, still days, and sending Lisa whimpering into the smallest room in the house.

Although it always takes a great effort of willpower to leave this house by the sea after dusk, it felt important to walk to the village on Easter Friday evening and join the quiet procession in the dark to the cemetery (the kimitirio, the place for sleeping); to be with the community as we remembered loved ones lost this year and previous years, some buried here and some laid to rest elsewhere. The sadness of the occasion was somewhat leavened as villagers quibbled over whether the priest was being thorough in his prayers for everyone’s relatives and talked loudly over his quiet chanting. Then we walked back up to the church, where the faithful pass under the flower-covered epitaphio while the mischievous set off more little bombs. I’d been reading recently about how dynamite has long been associated with rebellion against overlords and other authorities on the nearby island of Kalymnos. In theory, it’s a fine thing. In practice, I’m with Lisa on this one and took it as my cue to leave.

The traditional thing for Easter Sunday lunch is, of course, roasting a whole goat on the spit; but having witnessed the kitchen end of this at close quarters while living at the taverna at Ayios Minas, I was happy to give it a miss. This year it would be salad eaten a la swimsuit on the terrace. The days were so warm that Lisa and I gave up on the late afternoon walk to the monastery on Saturday and turned off instead to Plaka for a second swim of the day. I think this was the first afternoon this year that I’ve truly wanted to linger in the water. The sea was flat and blue as we walked home. And as the sun was going down, I was nailing new screens to the doors and windows against mosquitoes. There aren’t many here, but it only takes one...

Since this house at Ayios Antonis became mine last October, I’ve been slow at making changes, not wanting to be overly hasty in changing the spirit of the place. Certainly, since the place had been uninhabited for years, there were electrics to be updated and plumbing to be fixed or improved, all of which was completed by mid-January by local guys. With help, I’ve filled in cracks in walls where the rain actually made its way into the house, and cut back some of the overgrown forest that was the garden to reduce the actual danger of walking around it.

Since this house at Ayios Antonis became mine last October, I’ve been slow at making changes, not wanting to be overly hasty in changing the spirit of the place. Certainly, since the place had been uninhabited for years, there were electrics to be updated and plumbing to be fixed or improved, all of which was completed by mid-January by local guys. With help, I’ve filled in cracks in walls where the rain actually made its way into the house, and cut back some of the overgrown forest that was the garden to reduce the actual danger of walking around it. The next major job that needed tackling has been the fixing of the garden wall, bashed in and broken by marauding goats over the years that the property was empty, letting them tear at the trees with impunity. Last summer when I was hoping to purchase the property, since the owners were away in Athens I stopped up the gaps temporarily with anything I could find, from an old sink and rusty scaffolding to palm branches and timber, and stitching fences together using old bits of wire, all of which my neighbours Sotiris and Elpida laughed at since it wasn’t my responsibility. But there might not have been much garden left if I hadn’t done it.

It’s held up for six months, and as yet I haven’t planted much more than a tiny vegetable patch from seeds I had to hand, a flowering bush that I bought by mistake from a Cretan in a truck when I really only wanted potting soil, and an orange tree that I carried all the way from the hills of Rhodes, having bought it as a thank-you in return for some research, and which will be very lucky if it survives the salty windy off the sea. For now, I’m enjoying the abundance of poppies and other wildflowers, which the bees love, though Sotiris recommends I blast the whole thing with a farmako, chemical, in case of snakes. The fig trees have so far survived the flocks of hungry migrating birds. I’m sure the vines and the rest of the garden might start to appeal to goats again as the vegetation on the hillsides dries up over the coming summer months, and I don’t want to be invaded if I go away for a few days and take the guard-dog with me.

A few months back, a man who lives up the road offered his services in mending walls and fences, quoting a figure that seemed high but fair. But it was delayed first by his going away, then by my going away, then by my work and need to top up the bank account. And truth be told, I’ve been hesitant also because the walls that need repairing are beautiful old stone walls and I fancied having a go at restoring them without too much concrete. I’ve done a lot of staring at old walls as part of my new book project, and it would seem a terrible shame to spoil the original craftsmanship.

Besides, although figuring out what needs doing and how to get materials all seems overwhelming at times and it would be easier just to pay someone to deal with it, it’s in my character that I didn’t just want to hire someone to do the work for me; I wanted to learn about how to do it. I didn’t expect to become a master craftsman at dry-stone walls overnight, but I like to get my hands dirty. Having my own place gives me an opportunity to experiment and learn.

When I mentioned this to my Swedish neighbour Marita, who along with her husband is also a hands-on person who likes doing things in old-fashioned and eco-friendly ways, they were all for helping to rebuild a section of wall with minimal concrete. They even had a concrete mixer and could teach me how to make it. I managed to buy cement and I already had some sand, because the man who sold this place to me was a builder and never threw anything away. ‘If you’re not so religious you want to go to church,’ said Marita, ‘we’ll start on Monday.’

And so, on perhaps the hottest couple of days of the year so far, we started re-building a wall. We were rather glad none of our Greek neighbours were present to tell us what we were doing wrong. We spent a morning digging rocks out of the earth and hefting them up onto the wall. Marita and I chatted throughout, comparing Swedish and Old English, and noting that the bees are getting into holes in our houses and leaving piles of pollen. Her husband - who pretends not to speak English - took it upon himself to mend my hosepipe, making the evening watering much easier. Ian helped me to remove the debris that had been covering gaps in the rusty fence and got down on hands and knees to dig for more stones. Lisa, after some initial excitement, lay around in the shade, and occasionally inspected the wall for lizards. I thought about how in the old days, neighbours used to help one another to build what they needed, and I was profoundly grateful to have people nearby who still believed in that.

Sotiris came back from Rhodes and pronounced that our work looked all right. He spat now and then as he talked, but I don’t know whether he was deflecting the evil eye or just swallowed a fly. He told me again that I should cut down all the grass in the garden, adding that it might attract mice as well as snakes. But later another neighbour came by and agreed with me about keeping the poppies for now. She told me that when the plum trees in the garden were watered, Pantelis used to give away buckets of them to the neighbours. This garden has a history. And I have a bit of responsibility to look after those plum trees.

Published on April 30, 2019 22:48

February 10, 2019

Last Day in Astypalea

The cheese man isn’t there. Maybe because it's Saturday, although a few days ago at the café he said, ‘Any day, just come here at ten.’ The door of the kafeneio is padlocked, and on a table by the door are some remains from the night before, I guess: a glass, a bottle and a cigarette lighter.

A few evenings before, I ate a delicious saganaki here, local cheese lightly pan-fried. Panayiotis the owner, wearing leather boots, his black beard knotted under his chin, asked if I liked it and said if I wanted to buy some, he could call the man who makes it.

‘What I’d really like,’ I said, ‘is to go to where he makes it and see how it’s done. But I don’t know if that would be possible.’

The kafeneio in Maltezana was in ruins until Panayiotis decided to fix it up. Panayiotis' father was from Astypalea but like many families from the island they lived in Athens. Panayiotis grew up in the city and did building work, but there wasn't much going on with the economic crisis so ten years ago he came here and restored this kafeneio. He kept the original stone building from 1956 but added his touch of colour. The fishing and farming village has only eighty permanent residents, though plenty of tourists stay here in the summer. In February it is calm and sleepy. A guy came in for a coffee. A woman played with her phone. The dogs sniffed around, looking for food and attention. As I was finishing the salad of tomatoes and paximadia with lots of oregano and olive oil, a large man in a rain jacket walked in and sat by the wood-burning stove with a beer, and Panayiotis said, ‘This is the man who makes the cheese.’

The cheese man was talkative and full of stories, like a lot of the people I've met here. He used to work on boats, but since retiring from that he raises sheep and goats, and he makes cheese regularly from Easter onwards, though just in small quantities at this time of year when the animals need their milk to feed their young. The fresh, unaged cheese is called klori. He keeps about five hundred animals.

‘We had a big problem when it didn’t rain for the last three years.’ Without rain, there’s no grass and they have to buy feed. This year there’d been plenty of rain, and clear streams were flowing down the hillsides into the dam. ‘There are twelve and a half thousand animals on the island,’ he said. ‘They mostly belong to the church. But there are farms with animals all over the island.’ He reeled off a list of places. Astypalea is a small island with only three villages; most of these places are in the hills.

It's a beautiful day and perhaps it would be a shame to be indoors all day watching milk boil. Maybe he’s out on a fishing boat instead, catching calamari… Since the kafeneio is closed, I have a coffee at the taverna overlooking the sea instead. I can make the most of the sunshine and go for a walk and maybe a swim. Just along the coast there are fishing boats, a church with a dovecote, a path covered in mauve, purple and blue flowers, and the remains of a mosaic floor from the fifth century AD, the late Roman/early Christian era. It’s only my second trip to the island; maybe next time, I’ll catch up again with the cheese man.

Published on February 10, 2019 11:18

December 6, 2018

Bad Timing

The wind and waves pounded Ayios Antonis all night. I closed the shutters at the front of the house, and let a lively wind blow fresh air through a small high window that looks west to the vine. Winter weather seems to have come early – a rainstorm (kataigitha) with thunder and lightning last week and now a windstorm (fortuna) with winds up to 8 Beaufort, 90 mph. But it wasn’t cold under the duvet, and I enjoyed watching morning patches of sunlight glow from the back window to the east, while the occasional blue showed ahead. Thankfully Yiannis had managed to finish installing my solar-powered water heater on the roof yesterday. His work is being tested today as the fortuna blows white foam from the waves across the fields. In the harbour, someone was rescuing a submerged boat, said the other Yiannis as he arrived at the house. He, Lisa and I walked inland, enjoying a morning volta among green fields and grazing goats. We had to make a visit to the post office, borrowing Edward’s car to get the job done faster.

Sunlight dappled the hilltops as we drove across the island. Edward had asked us to put some petrol in as the venzinadiko would be closed for the next ten days, and sure enough, men were digging up the forecourt – to replace the lines, said Zafeiris – and vehicles gathering to stock up with fuel. Michalis, wearing his woolly hat as always though surprisingly with no cigarette between clamped lips, was carrying two big containers to keep his fishing boat topped up. The owner of the car in front of me was an army officer in full dress uniform. I remembered as I drove down the hill that it was the festival of St Nicholas – the patron saint of fishermen, and the saint to whom the main church in Livadia is dedicated. Eleftheria had mentioned she’d been making a cake to take to the celebration yesterday on the eve of the festival at the little church at Plaka. Sure enough, people were out and about around the square, dressed up and on their way back from church, some sitting having coffee at Yorgos’ kafeneion, some filling the tables at Roula’s. One of the port policemen crossed our path wearing a white peaked cap, and Pantelis was nattily dressed in a blue suit and a blue striped jumper. It was clearly a big day.At the post office, three parcels awaited us. Merkouris popped in to ask Savvas the postmaster to do him a favour, kissing him on the forehead cheekily. A lady from the village commented that Savvas was all neatly barbered – it had been his name day the day before. Papa Manolis, the priest of Megalo Horio, was there.Yiannis asked him, ‘How are you?’ In Greek this is literally, ‘What are you doing?’The answer came as the usual, ‘What can I do? I’m here!’ ‘It’s winter,’ Yiannis commented, eliciting mockery. ‘Are you cold?!’ There is usually good-natured banter between Yiannis and the local men, each side pretending they’ve walked a higher mountain that day. ‘How far did you swim today? How many fish did you catch?’ ‘Lots!’ The weather seems to think it’s winter, though. When Yiannis asked when the next post would come, as he was waiting for a letter, Savvas replied with his dry smile, ‘Only God knows. Only God knows when the boat will come!’Vegetable supplies at (other) Yiannis’ supermarket were dwindling, the last delivery of produce past its best. Panayiotis at the supermarket next door said he hadn’t yet prepared any octopus for me, as the weather hadn’t been calm enough to go out in his little boat, his varka. ‘I can’t go out in the big fishing boat any more, I’m seventy years old! Let the young ones fish now.’ But he would certainly be dancing later in the square for the St Nicholas celebrations.The flames of a barbecue had already been lit in the square, although it would likely be quite a few hours before the music began. It still seemed a shame to be driving back across the island – Antonis shouted out to Yianni as we drove past, ‘Come and dance!’ – but work has to be done. We’d timed our visit to Livadia wrong. Still, I love the fact that the islanders keep and enjoy their celebrations.

Chatting with Yianni the electrician as he worked on my house this week, he told me that even when he and his family returned to the island from America in the eighties, Tilos was more village-y. If they had to go to Plaka, it was quite a journey and they’d stay there while they looked after their animals or fields, not like today when it’s five minutes in the truck. If someone needed a house, all their relatives would get together and build them a house with their hands, out of stone. These are the things I’ve been researching for my next book. Not just on Tilos but across the Dodecanese, I’m looking at how life changed dramatically over the last century – even half a century – but also looking for traditions that survived. This house that’s now my home evolved over the last half-century. Pantelis and Sophia built and cared for their home and planted olives and figs and grapes in the garden. Their children moved away, and gradually they did too, and the house had been more or less abandoned for at least five years. Everything had been left as if they hoped to come back. It’s good to be caring for the house again, with friends and family helping. Just a week ago, I celebrated my birthday with a swim in the sea – just as a huge thunderstorm brought a deluge of rain, and my mum sheltered in a cave on the beach with Lisa as the water poured over the edge. We sat around the kitchen table that evening and then danced around the table in our own way. The next day, we ate fresh fish caught so close to the house that we could listen to the fishermen on the boat. Today, it’s a good day for fishermen to be safely in harbour. The gale-force winds are a good excuse for me not to be outside fixing holes in the wall, but instead running around Ayios Antonis dodging sea-foam and taking pictures…

Published on December 06, 2018 05:21

October 13, 2018

An Island Home

When I returned to Tilos in August 2017, after my short trip to Olympos in the north of Karpathos turned into a year and a half, I rented a studio near the sea where I could listen to the waves. The experience and inspiration of my time in Karpathos had been invaluable, but I needed a base. And however much I loved Karpathos, Tilos felt like my real home.

In December, I broached the subject with my parents of giving up the flat I owned in England in order to buy a place here. I’d been happy to rent for years, but it felt time to have a place of my own again. Giving up the security of property in England would be a big step, but my parents fully supported the idea. And so, in January, I put my Chichester flat on the market. I’d been told a few years earlier that it hadn’t increased much in value since I bought it over ten years ago, and I had a sizeable mortgage, but I’d see what money I could raise.

An offer came in and I nervously declined, hoping my estate agent Tom knew what he was doing, and then a better offer came in. I was on the island of Nisyros in late February, staying in a half-deserted village and going on long walks every day with my dog Lisa, when the deal was done and I celebrated with a raki. Then Lisa and I travelled to England and by the time we returned in late April, the sale was complete and I enjoyed looking at my bank account and temporarily feeling very rich.

Very busy with writing and editing work, I wasn’t able to start looking at houses properly until June. Since there’s no longer an estate agent’s office on Tilos, I decided the way to find out what was for sale was to tell everyone I know on the island. Soon, everyone was telling me about properties for sale.

I pretty much liked everything I saw, from the old houses that were cheap but needed a lot of structural work, to those that were ready to move into but more expensive. Most were old properties in Megalo Horio, up little alleyways that are picturesque but impossible to drive building materials to. A builder told me, only half-joking, that replacing a roof and repairing some walls would take two years. I wasn’t sure I wanted the frustrations and rising costs of a building project.

I’d almost decided on borrowing money to buy a beautifully restored old house in the village, though I was wary about having neighbours very close. And then one day when I stopped on the road to Eristos to buy vegetables from Michali, he said:

‘Are you still looking for a house? My relative has the keys to a nice place for not too much money at Ayios Antonis.’

It had just gone on the market, and was close to the sea in the north of the island. I got the keys and went to take a look. It was in an overgrown garden, hidden behind trees; not big, but not too small. The owners were an old couple who used to live there but had moved to Athens to be close to the children and to hospitals. I spoke to the man, Pantelis, on the phone. He had built the place himself. The house inside looked well cared for, although it had been closed up for five years. Goats had broken through the fence and eaten what they could in the garden, but the figs and grapes were good and there was bougainvillaea.

A friend in Megalo Horio gave me the number of her lawyer. I needed to check the legalities. I didn’t want to get too excited, but I loved the views of mountains and sea. The sound of the waves, the feeling of space. The lawyer and the surveyor worked on things...

A friend in Megalo Horio gave me the number of her lawyer. I needed to check the legalities. I didn’t want to get too excited, but I loved the views of mountains and sea. The sound of the waves, the feeling of space. The lawyer and the surveyor worked on things...In late summer, Michalis asked me, ‘What happened with the house that’s for sale?’

‘It’s not for sale,’ I said. Then I smiled. ‘Because I’ve bought it.’ Well, almost.

There was still paperwork to do. In September, I suddenly had to acquire a Greek bank account and transfer large sums of money. I’d hesitated, worried there would be another Greek financial crisis... At first I was told I didn’t have the necessary paperwork to open a Greek bank account. But then the lawyer, Maria, spoke to the bank and suddenly it was possible.

I was told to hurry over to Rhodes for the signing of the contract, only to find that we were still missing a piece of paper. But it wouldn’t be Greece if it went smoothly. ‘We are waiting for the bureaucracy,’ said the lawyer Maria and her assistant Maria. Everyone – the bank manager, the notary – had been exceptionally nice and helpful and down to earth.

Then last Sunday, I went over to Rhodes again, assured that everything was now in place. There was a bit of a panic at the bank. Thanks to capital controls, a suitably absurd conundrum exists whereby a large bank draft cannot be issued without a contract proving it’s for the purchase of a house; but a contract for the purchase of a house cannot be signed without the presence of said large bank draft. Everyone in the bank was very nice but they kept passing the responsibility for this problem from one to another like basketball players.

‘But other people buy houses,’ I said.

‘Not many, recently,’ said Maria. But she somehow got it done. And in the meantime we drew up a civil agreement detailing the items that would stay in the house.

I arrived at Maria's office to sign the contract on Tuesday with a box of chocolates as a gift for the two miracle-working Marias, and was humbled when she handed me a beautiful painting, the masterful work of her art class teacher.

‘A gift for your new house,’ she said.

Pantelis’ daughter was there, and the notary read the contract to us and we signed. A few days later, I am in Tilos, the owner of a house by the sea.

Published on October 13, 2018 00:17