Jennifer Barclay's Blog, page 9

June 21, 2015

On the Volcano

On a windy evening I was on the island of Nisyros, standing beside a tiny, surreally perfect blue and white chapel high above the village of Nikia, surrounded by warm orange light as the sun went down. I heard a cow somewhere below on the slopes towards the sea, or in the caldera of the volcano. The wind was cool, so after I'd descended the steps and Yiannis finished taking photographs, he suggested a shot of tsipouro for the road at the restaurant where we'd parked the bike. I drank it and walked out to see a full moon, bright and yellow, against a dusky blue sky.My Greek friend Yiannis is a photographer, but he also has a day job, from which he had two weeks’ holiday. Since I get a chance to write about Greek islands a couple of times a year for a newspaper or magazine, I need to keep exploring them. I am deliriously happy to be back home on Tilos, but June is a good time to travel. We cooked up a plan to spend a few days in neighbouring Nisyros (an hour away by ferry), be back in Tilos for Yianni to open his Home Gallery on the weekend, then take a longer trip to Kastellorizo. Friends had agreed to look after Lisa; Yiannis had gently reminded me that we could take her but we wouldn’t get to do as many things - I’d told him about a disastrous time when I’d had to take her along to Crete.We rented a scooter on arrival in Nisyros that lunchtime, after dropping stuff at the hotel (Three Brothers, at the port). Twenty minutes later, up a winding road and on a bumpy, rocky, pot-holed track, I remembered I get terrified on the back of a scooter when I’m out of practice. ‘Er, do you mind if I walk?!’ I asked, feeling like an idiot. What a start to the trip. But it turned out to suit both of us, as he’d be stopping often to take photos.

On a windy evening I was on the island of Nisyros, standing beside a tiny, surreally perfect blue and white chapel high above the village of Nikia, surrounded by warm orange light as the sun went down. I heard a cow somewhere below on the slopes towards the sea, or in the caldera of the volcano. The wind was cool, so after I'd descended the steps and Yiannis finished taking photographs, he suggested a shot of tsipouro for the road at the restaurant where we'd parked the bike. I drank it and walked out to see a full moon, bright and yellow, against a dusky blue sky.My Greek friend Yiannis is a photographer, but he also has a day job, from which he had two weeks’ holiday. Since I get a chance to write about Greek islands a couple of times a year for a newspaper or magazine, I need to keep exploring them. I am deliriously happy to be back home on Tilos, but June is a good time to travel. We cooked up a plan to spend a few days in neighbouring Nisyros (an hour away by ferry), be back in Tilos for Yianni to open his Home Gallery on the weekend, then take a longer trip to Kastellorizo. Friends had agreed to look after Lisa; Yiannis had gently reminded me that we could take her but we wouldn’t get to do as many things - I’d told him about a disastrous time when I’d had to take her along to Crete.We rented a scooter on arrival in Nisyros that lunchtime, after dropping stuff at the hotel (Three Brothers, at the port). Twenty minutes later, up a winding road and on a bumpy, rocky, pot-holed track, I remembered I get terrified on the back of a scooter when I’m out of practice. ‘Er, do you mind if I walk?!’ I asked, feeling like an idiot. What a start to the trip. But it turned out to suit both of us, as he’d be stopping often to take photos.

And so, the scooter bumped along ahead and I wandered slowly and happily along a track I’d explored before, looking at spiky plants with dusty-pink flowers, poking my nose into a chapel built into the rock. As he photographed an old tree, I walked up a slope and found the remains of a house with a threshing circle and cistern and vaulted stone rooms, overlooking the centre of the volcano. Further along, I visited the little monastery of Stavros, finally descending towards the volcanic craters, reaching a white and yellow point on the path where I caught for the first time the earthy sulphur smell from the fumaroles that always makes me feel close to something mysterious and deep.

Veering off to one of the smaller craters, I spent half an hour just poking around another deserted farm with its stone walls and threshing circle. Yiannis wondered what had happened to me – there’s no phone signal within the caldera. I studied the shapes and the colours on a slope – tinges of green and orange and pink – as the wind caught the rising steam. The centre of the volcano felt peaceful and otherworldly.

Veering off to one of the smaller craters, I spent half an hour just poking around another deserted farm with its stone walls and threshing circle. Yiannis wondered what had happened to me – there’s no phone signal within the caldera. I studied the shapes and the colours on a slope – tinges of green and orange and pink – as the wind caught the rising steam. The centre of the volcano felt peaceful and otherworldly. Because it’s a unique place, though, coachloads of daytrippers can present a bit of a problem. Suddenly I heard a noise and spotted not one but two – no, three – coaches coming down the road in the distance. People would be here soon.Stephanos crater is a vast white sunken circle streaked with yellow and grey, with steep walls and a flat, cracked mud floor punctuated by a cluster of blow-holes. Around the edges of the crater, bright yellow openings release hot vapour, rising in wisps as if to inspire the oracle. I knelt close to listen to the hissing and gurgling within, and was momentarily blinded by the steam on my sunglasses.

Soon, I overheard two English women, talking about volcano experiences they’d had. Apparently at one, they cook you food over the heat. ‘Oh yes, I’ve done that,’ said the other. Why do some people travel in a way that makes them jaded? We drove away, up to the rim of the caldera and then around towards Nikia where we saw the rugged north-facing cliffs of Tilos across the sea: over there, a cloud hung above the mountain where I knew the monastery of Ayios Panteleimonas was. Here we took a little road downhill, past abandoned stone houses and wandering cows, and found ourselves at another church of Ayios Panteleimonas. Steps led down to a cove of jagged and pocked black lava. This was Avlaki; I’d seen photos of it in the volcano museum on my last trip. Somewhere in the waters below, hot springs bubbled up. A few once-genteel buildings now stood beautifully desolate around a small harbour, their plaster crumbled away and their balconies rusting, returning to the natural grey and red stone. I was mesmerised, thinking of the stories that might be unearthed of this place; maybe I'd just inhaled too much sulphur. I went for a swim off the jetty to wash off the dust of the road, while Yiannis took a photograph of water spilling over rocks. High above us at the top of the hill, the sides of buildings were lit by late afternoon sunlight. I was getting used to the scooter, and grinned as I admitted that we wouldn’t have done nearly so much without it. Later, after sunset at Nikia, we drove back up and along the caldera’s rim to the half-dilapidated village of Emborio, where cats leapt across the alley from one roof to another. Next day, we found the Roman shrine of Panayia Thermiani, and continued along the coast via Cape Katsounis to see the layers of volcanic eruptions in the cliffs: then at the end of the road we left the scooter and walked around the cliffs to Pachia Ammos, where the grey, red and white of Nisyros rock merge to form sand that looks chocolate-brown, and behind the dunes are lavender bushes and olives – perhaps once there were farms.

Nisyros felt wild and natural and abandoned. A man we met at lunchtime at the lovely meze restaurant at Loutra said, ‘In old times, people made things. Now we break them.’ But it’s a wild abandon full of beauty and colour.

Nisyros felt wild and natural and abandoned. A man we met at lunchtime at the lovely meze restaurant at Loutra said, ‘In old times, people made things. Now we break them.’ But it’s a wild abandon full of beauty and colour.

The meze restaurant at Loutra

The meze restaurant at LoutraYiannis had compiled clever itineraries to make the most of our short trip. One of the books mentioned a ruined castle at Parletia, but it wasn’t marked on the basic map we had. The lady in the restaurant kitchen at Nikia said we’d find it, and pointed us in the right direction. We walked along a rough and overgrown path, losing our way a couple of times in the scrub as it seemed to peter out, scrambling down gravelly sections, resolving a couple of times just to keep going to see what was around the next outcrop of rock. Eventually we found some broken walls on a very steep lava neck with fantastic views from the top, and decided that was it. Heading back to Nikia, I realised I was starving, and at that moment a group of piglets launched themselves down the hill, squealing. We’d been out at dawn – optimal photography hour – and now it was late afternoon were getting tired. ‘Let’s go to the sauna?’ suggested Yiannis. I’d pointed it out to him at the entrance to the village of Emborio, a tiny cave where hot steam rose up naturally out of the rock. Yiannis thought we should change into swimsuits to make the most of it. Laughing, we stuffed clothes into the bag and parked the scooter across the entrance. We sat inside on a stone bench, surrounded by green rocks, feeling around for the hottest steam vents, relaxing in the peace. I heard a coach pass by on the road outside. And then it stopped. We peered out, and the people in the coach waved. They all trooped out... Time to throw clothes on, and get back on the bike.

Published on June 21, 2015 01:49

May 11, 2015

The Place To Be

‘Are you the Octopus lady? Back from Australia?’ asks the Englishman walking down the steps in Megalo Horio. Lisa is wagging her tail as if he’s a long-lost friend until he confesses he's not really a dog person. Well, I suppose I am the Octopus Lady, though it sounds like a circus freak, in the same way that Kyria Vicky became the Elephant Lady by association with the museum.I have been reprimanded for not writing a blog since my return to Tilos, but who has time? There’s been fresh bread to bake, capers and oregano to gather and prepare, migrating birds to spot, a tan to top up... The verticality of Megalo Horio took a bit of getting used to all over again after nine months away, and I’m just getting my breath back. In fact, after so many months without my own home, I wanted to take time to enjoy the simple pleasure of moving back into my old house in the village. There’s been the bright moonlight to admire, and the lemon-yellow morning sunshine that creeps across the mountains, illuminating the lines of old terraces, and the warm afternoon sun that brings out the brilliance of yellow flowers on the hillside. Clear blue sea to dive into. The quiet at night in the village, when all you can hear is a Scops owl’s haunting call, gentle footsteps as someone passes along the alley. Mornings of soft birdsong and bees buzzing and sheeps’ bells. Lisa seemed to remember me, though she had been perfectly happy and well cared for in my absence thanks to Stelios and his parents, and house-sitters Guillaume and Natacha. But she gratifyingly made a fuss, licking me, grabbing hold of me with her front paws, rolling over for the belly-rub. And we're back to our routine of walking to the beach every day.

‘Are you the Octopus lady? Back from Australia?’ asks the Englishman walking down the steps in Megalo Horio. Lisa is wagging her tail as if he’s a long-lost friend until he confesses he's not really a dog person. Well, I suppose I am the Octopus Lady, though it sounds like a circus freak, in the same way that Kyria Vicky became the Elephant Lady by association with the museum.I have been reprimanded for not writing a blog since my return to Tilos, but who has time? There’s been fresh bread to bake, capers and oregano to gather and prepare, migrating birds to spot, a tan to top up... The verticality of Megalo Horio took a bit of getting used to all over again after nine months away, and I’m just getting my breath back. In fact, after so many months without my own home, I wanted to take time to enjoy the simple pleasure of moving back into my old house in the village. There’s been the bright moonlight to admire, and the lemon-yellow morning sunshine that creeps across the mountains, illuminating the lines of old terraces, and the warm afternoon sun that brings out the brilliance of yellow flowers on the hillside. Clear blue sea to dive into. The quiet at night in the village, when all you can hear is a Scops owl’s haunting call, gentle footsteps as someone passes along the alley. Mornings of soft birdsong and bees buzzing and sheeps’ bells. Lisa seemed to remember me, though she had been perfectly happy and well cared for in my absence thanks to Stelios and his parents, and house-sitters Guillaume and Natacha. But she gratifyingly made a fuss, licking me, grabbing hold of me with her front paws, rolling over for the belly-rub. And we're back to our routine of walking to the beach every day.

Stelios messages from his house one day to check I don’t need the car. We have an informal car-sharing scheme in place, and he has some stuff to move. A few minutes later he walks by the house carrying a fridge on his back. Lisa wants to go with him so I follow him down to the car, helping to push the seats forward so he can put it in the boot. ‘Prosekeh to jami,’ I say – mind the window. The back of the car is a different colour because the window had to be replaced after an accident last summer. ‘Etsi egineh?’ Is that how it happened, I ask, grinning, knowing how much stuff gets carried around in the car over the summer when the kantina is working.‘Kapos etsi,’ he says, grinning back. ‘Something like that.’The young kids play football outside the house in the afternoon. Itinerant salesmen advertise their wares – from flowers to live turkeys – over the loudspeaker as they stop on the road below: ‘Come ladies, we’re in your neighbourhood for a few more minutes’. I hear a voice that sounds like Grigoris calling my neighbour to do some work, and a few hours later when I’m walking Lisa to Eristos, I see them riding a tractor stacked with hay bales, and they wave hello. I’ve missed the easy friendliness and intimacy of the village, from the morning when we’re rubbing sleep out of our eyes to the warm evening when Rena and her family are sitting outside the shop.

Stelios messages from his house one day to check I don’t need the car. We have an informal car-sharing scheme in place, and he has some stuff to move. A few minutes later he walks by the house carrying a fridge on his back. Lisa wants to go with him so I follow him down to the car, helping to push the seats forward so he can put it in the boot. ‘Prosekeh to jami,’ I say – mind the window. The back of the car is a different colour because the window had to be replaced after an accident last summer. ‘Etsi egineh?’ Is that how it happened, I ask, grinning, knowing how much stuff gets carried around in the car over the summer when the kantina is working.‘Kapos etsi,’ he says, grinning back. ‘Something like that.’The young kids play football outside the house in the afternoon. Itinerant salesmen advertise their wares – from flowers to live turkeys – over the loudspeaker as they stop on the road below: ‘Come ladies, we’re in your neighbourhood for a few more minutes’. I hear a voice that sounds like Grigoris calling my neighbour to do some work, and a few hours later when I’m walking Lisa to Eristos, I see them riding a tractor stacked with hay bales, and they wave hello. I’ve missed the easy friendliness and intimacy of the village, from the morning when we’re rubbing sleep out of our eyes to the warm evening when Rena and her family are sitting outside the shop.

There have been impromptu dinners with friends old and new, too...‘Echo psaria,’ says Michalis, stopping at the gate to stroke Lisa. I have fish. He doesn’t need to say they’re fresh: some things go without saying. He invites me to come and eat in the evening at the house of Ian and Margarita, an English-Polish couple who have been living just a few doors away for a month’s holiday with their beagle Lola, and are constantly insisting I join them for dinner or just a glass of wine and some aubergine salad. Margarita, like me, has happy memories of childhood holidays in Greece, only being from Poland her family used to drive to Greece with the car loaded up with all their food, even potatoes. ‘I can’t tonight, I have work,’ I protest. But later Margarita comes by and repeats the invitation. So although I’m hardly sensible after a long day, I grab a half-empty bottle of plonk and head over, and we laugh sitting out on the terrace and are happy to be a long way from the UK election. Another evening a group of us go to Livadia to the apartment of John Ageos Daferanos, resident of Tilos since late last summer, to see his photographs. I talk to him about the images over coffee. ‘They’re my interpretation of the island, my attempt to penetrate the mystique of the place, to capture its spirit. In this isolated place there is peace and silence but also a wildness inside.’ (See the ‘Island Life’ page of this blog.)The oleander flowers are just coming out, I notice as I start to walk to Livadia. A car driving towards me slows down, and Savvas from the post office says hello. ‘Come two packets of food for Lisa,’ he says. I ordered the Friskies she likes online. He’ll deliver them soon. ‘The next time I come in Megalo Horio.’ I thank him and walk on, beaming at how much I love life on a small island. Next morning, I receive it with a hole in the top of the bag: the clever crows spotted something that looked like food on the top of Yorgos Orfanos’ truck.

There have been impromptu dinners with friends old and new, too...‘Echo psaria,’ says Michalis, stopping at the gate to stroke Lisa. I have fish. He doesn’t need to say they’re fresh: some things go without saying. He invites me to come and eat in the evening at the house of Ian and Margarita, an English-Polish couple who have been living just a few doors away for a month’s holiday with their beagle Lola, and are constantly insisting I join them for dinner or just a glass of wine and some aubergine salad. Margarita, like me, has happy memories of childhood holidays in Greece, only being from Poland her family used to drive to Greece with the car loaded up with all their food, even potatoes. ‘I can’t tonight, I have work,’ I protest. But later Margarita comes by and repeats the invitation. So although I’m hardly sensible after a long day, I grab a half-empty bottle of plonk and head over, and we laugh sitting out on the terrace and are happy to be a long way from the UK election. Another evening a group of us go to Livadia to the apartment of John Ageos Daferanos, resident of Tilos since late last summer, to see his photographs. I talk to him about the images over coffee. ‘They’re my interpretation of the island, my attempt to penetrate the mystique of the place, to capture its spirit. In this isolated place there is peace and silence but also a wildness inside.’ (See the ‘Island Life’ page of this blog.)The oleander flowers are just coming out, I notice as I start to walk to Livadia. A car driving towards me slows down, and Savvas from the post office says hello. ‘Come two packets of food for Lisa,’ he says. I ordered the Friskies she likes online. He’ll deliver them soon. ‘The next time I come in Megalo Horio.’ I thank him and walk on, beaming at how much I love life on a small island. Next morning, I receive it with a hole in the top of the bag: the clever crows spotted something that looked like food on the top of Yorgos Orfanos’ truck.

It’s almost three weeks since I got back, but people are still stopping to say hello and welcome me. They ask how long I’m staying, and I say, ‘I’m staying.’

It’s almost three weeks since I got back, but people are still stopping to say hello and welcome me. They ask how long I’m staying, and I say, ‘I’m staying.’Some who have been reading this blog since last year will want to know if I’m back here alone after following Ian to Australia. The answer is that he will stay there and continue looking after his mother, who has Alzheimer’s; I had to come back home for a while - left Australia two months ago to see family and for work - and once I got back to Greece, I knew I was staying. We didn’t have an easy time of things, having barely spent a month alone together while I was there. We decided to let go, get on with our lives separately and remain just friends for now.

I’m glad I had courage to lose sight of the shore, but now I’ve trusted and followed my heart back to Tilos, the source of so much happiness for me. Greece was still waiting. Lisa was well. I returned here at the same time of year, late April, that I first moved here four years before. My lemon tree, cut back over the winter, is already flourishing with fresh green leaves. Time to plunge into the island's deep waters and lie on its hot sands again.

Published on May 11, 2015 11:20

April 20, 2015

At Kos Town

Juicy and messy… No, not my life, just an afternoon snack of big Greek tomatoes, eaten whole. A taste I’ve missed.Now, evening. The smell of a harbour. Sound of palm leaves rustling, mopeds haring by on the road below, a high-pitched church bell clanging. Sitting on my balcony overlooking Kos harbour, I’ve already eaten handfuls of peanuts, their pink papery skins encrusted with salt, as I sip on a glass of buttery, fruity, local white wine.I’ve been gone too long from Greece, but it’s allowed me to experience everything afresh. I’m arriving at the same time of year I did four years ago, when I came to stay, that new beginning. When the cab driver from the airport today asked me if I was staying many days in Greece, I said a definitive ‘nai’, yes, and laughed.

Juicy and messy… No, not my life, just an afternoon snack of big Greek tomatoes, eaten whole. A taste I’ve missed.Now, evening. The smell of a harbour. Sound of palm leaves rustling, mopeds haring by on the road below, a high-pitched church bell clanging. Sitting on my balcony overlooking Kos harbour, I’ve already eaten handfuls of peanuts, their pink papery skins encrusted with salt, as I sip on a glass of buttery, fruity, local white wine.I’ve been gone too long from Greece, but it’s allowed me to experience everything afresh. I’m arriving at the same time of year I did four years ago, when I came to stay, that new beginning. When the cab driver from the airport today asked me if I was staying many days in Greece, I said a definitive ‘nai’, yes, and laughed.

It’s a wonderful time to arrive in the islands of the South Aegean. As we landed in Kos – that dramatic landing, veering away towards the island of Nisyros, low over the quarried pumice islet of Yiali, then swooping back low over the blue sea to land across a narrow, flat piece of the island – the land looked green. The cab driver said there had been a lot of rain but now for a week, kalokairi – summer. Tourists just started arriving this week; in two weeks’ time, he said, the island will be full. And what of the economic problems? ‘Here, we don’t bother ourselves with that,’ he said, half-joking. ‘We have tourism.’ When I ask him about Greece leaving Europe he says, ‘They won’t let us. And we shouldn’t.’ I am, by the way, chatting to him in Greek. It’s been a shaky first day, forgetting how to say things, but as always the Greeks are complimentary of any attempt to speak Greek. We passed olive groves, vineyards, all a bit ramshackle; wandering cows; bakeries. The cab driver waved hello to other drivers. It’s that familiar start-of-season, start-of-summer optimism that you get, especially on the big islands. There was warm sunshine and a breeze, green not yet burned to summer brown.I arrived too early to check in to my room, so sat with a frappe and iced water on the terrace of the grandly named Kosta Palace (where I am paying a grand total of fifteen pounds, including breakfast), taking it all in: the pale blue sparkling water, across which were the minarets and blue domes and palm trees of the town against a backdrop of mountain ridge. Pop music was blaring. The cab driver had been playing music too. I missed music.

It’s a wonderful time to arrive in the islands of the South Aegean. As we landed in Kos – that dramatic landing, veering away towards the island of Nisyros, low over the quarried pumice islet of Yiali, then swooping back low over the blue sea to land across a narrow, flat piece of the island – the land looked green. The cab driver said there had been a lot of rain but now for a week, kalokairi – summer. Tourists just started arriving this week; in two weeks’ time, he said, the island will be full. And what of the economic problems? ‘Here, we don’t bother ourselves with that,’ he said, half-joking. ‘We have tourism.’ When I ask him about Greece leaving Europe he says, ‘They won’t let us. And we shouldn’t.’ I am, by the way, chatting to him in Greek. It’s been a shaky first day, forgetting how to say things, but as always the Greeks are complimentary of any attempt to speak Greek. We passed olive groves, vineyards, all a bit ramshackle; wandering cows; bakeries. The cab driver waved hello to other drivers. It’s that familiar start-of-season, start-of-summer optimism that you get, especially on the big islands. There was warm sunshine and a breeze, green not yet burned to summer brown.I arrived too early to check in to my room, so sat with a frappe and iced water on the terrace of the grandly named Kosta Palace (where I am paying a grand total of fifteen pounds, including breakfast), taking it all in: the pale blue sparkling water, across which were the minarets and blue domes and palm trees of the town against a backdrop of mountain ridge. Pop music was blaring. The cab driver had been playing music too. I missed music.

After my coffee, I didn’t have to wander far to find a bakery with a good cheese pie, and next door was a ticket office where I bought my ticket to Tilos for tomorrow, while at the café-bar opposite, groups of young people sat around sipping coffees, enjoying the sunshine. I walked back to the harbour and watched the fishing boats with their blue trim and hand-painted names: Kapetan Tasos, Giorgos, Maria. A wiry old man a with deeply tanned, lined face, wearing rubber boots and old clothes, was telling his young helper to leave his work mending nets on the boat with the cross painted on its prow, the Panayia Kastrou, Our Lady of the Castle. Ela! As to… Many of the boats had dark blue circular talismans against the evil eye. Another young man was threading bait onto hooks, listening to music. ‘Eh Yiorgo, ti ora eineh?’ he shouted at a man who was strolling from one boat to another. An old man put a cigarette in his mouth, tossed the cellophane from the new pack over his shoulder into the water. He stood to talk to Yiorgo, gestured with his arm outstretched and his thumb and forefinger twisted in a question, lamented the state of affairs compared to the old days when he would make such-and-such ‘kathara’, take-home. Then he sat again with a mobile phone to his ear.

After my coffee, I didn’t have to wander far to find a bakery with a good cheese pie, and next door was a ticket office where I bought my ticket to Tilos for tomorrow, while at the café-bar opposite, groups of young people sat around sipping coffees, enjoying the sunshine. I walked back to the harbour and watched the fishing boats with their blue trim and hand-painted names: Kapetan Tasos, Giorgos, Maria. A wiry old man a with deeply tanned, lined face, wearing rubber boots and old clothes, was telling his young helper to leave his work mending nets on the boat with the cross painted on its prow, the Panayia Kastrou, Our Lady of the Castle. Ela! As to… Many of the boats had dark blue circular talismans against the evil eye. Another young man was threading bait onto hooks, listening to music. ‘Eh Yiorgo, ti ora eineh?’ he shouted at a man who was strolling from one boat to another. An old man put a cigarette in his mouth, tossed the cellophane from the new pack over his shoulder into the water. He stood to talk to Yiorgo, gestured with his arm outstretched and his thumb and forefinger twisted in a question, lamented the state of affairs compared to the old days when he would make such-and-such ‘kathara’, take-home. Then he sat again with a mobile phone to his ear.

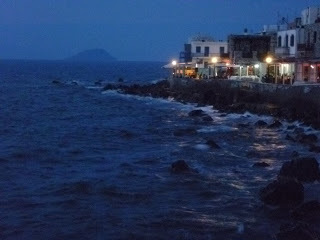

I asked another fisherman on shore about the threading of bait onto lines. He was cutting up fresh fish and threading the pieces onto lines arranged around the rim of a bowl-shaped bucket. He said it was called ‘paragadhi’, and you trail the lines behind the boat one by one.Later, I wandered around as a cool evening wind blew off the sea. I stopped to look in a cheese shop, and the man inside smiled in welcome. I passed a tiny chapel with ancient white marble revealed beneath the modern exterior. The roots of olive trees were pushing up the concrete slabs of the pavement. A man on a motorbike was laughing with some tourists standing at an ATM: ‘Money, OK! Today. Next month, maybe no money!’ There was a tantalising smell of grilling meat as I passed neighbourhood tavernas, and little houses covered in pot plants.Now it’s dusk, and a fishing boat is chugging in to shore. The sun has gone from the mountain opposite, and the water has turned pale, a few streaks of cloud tinged pink. I’ve finished my wine and eaten far too many peanuts. Lights are beginning to come on around the harbour, and the fishing boats are bobbing on rough water.

I asked another fisherman on shore about the threading of bait onto lines. He was cutting up fresh fish and threading the pieces onto lines arranged around the rim of a bowl-shaped bucket. He said it was called ‘paragadhi’, and you trail the lines behind the boat one by one.Later, I wandered around as a cool evening wind blew off the sea. I stopped to look in a cheese shop, and the man inside smiled in welcome. I passed a tiny chapel with ancient white marble revealed beneath the modern exterior. The roots of olive trees were pushing up the concrete slabs of the pavement. A man on a motorbike was laughing with some tourists standing at an ATM: ‘Money, OK! Today. Next month, maybe no money!’ There was a tantalising smell of grilling meat as I passed neighbourhood tavernas, and little houses covered in pot plants.Now it’s dusk, and a fishing boat is chugging in to shore. The sun has gone from the mountain opposite, and the water has turned pale, a few streaks of cloud tinged pink. I’ve finished my wine and eaten far too many peanuts. Lights are beginning to come on around the harbour, and the fishing boats are bobbing on rough water.I have a ticket for the ferry to Tilos leaving tomorrow lunchtime. I hope the wind dies down a little. But nothing, not the prospect of seasickness or delays, can quell my happiness at being back in Greece. It’s a year since I first went to Australia; Yiannis has to stay there for now to look after his mother. I still have the tiny bag of sand from Skafi beach that I took with me when I left, which I’ll scatter back where it belongs very soon.

Published on April 20, 2015 10:33

January 17, 2015

Water Dragons and Mr Browne

I was on the lookout for duck-billed platypus in the Wingecarribee River, but all I could see so far on the calm, mud-brown water were some duck-billed ducks, which were nice but not quite as exciting. As I looked down at the trail I spotted a shiny lizard, about as long as my hand, wriggling fast into the undergrowth - then another, and another, leaping from the rocks to hide. It was about four o’clock, and there was nobody else about, so probably they were basking in the heat from the sun on the boulders. Then a little further on I saw a couple of bigger ones, different, and as I stopped still, so did they.

I was on the lookout for duck-billed platypus in the Wingecarribee River, but all I could see so far on the calm, mud-brown water were some duck-billed ducks, which were nice but not quite as exciting. As I looked down at the trail I spotted a shiny lizard, about as long as my hand, wriggling fast into the undergrowth - then another, and another, leaping from the rocks to hide. It was about four o’clock, and there was nobody else about, so probably they were basking in the heat from the sun on the boulders. Then a little further on I saw a couple of bigger ones, different, and as I stopped still, so did they.

These were over a foot long, pale green-grey with ridged backs and black stripes across their tails. They kept their eyes glued on me for the ten minutes or so that I watched them then reached slowly in my bag for my camera. I later learned that they were water dragons, native to eastern Australia, and they must have got used to people as the trail was close to the village. I’d only continued a few more steps when I heard a splash in the river below and saw something swimming like a wiggling arrow across the surface, before pulling itself up on the rocks. Sure enough, another water dragon.

These were over a foot long, pale green-grey with ridged backs and black stripes across their tails. They kept their eyes glued on me for the ten minutes or so that I watched them then reached slowly in my bag for my camera. I later learned that they were water dragons, native to eastern Australia, and they must have got used to people as the trail was close to the village. I’d only continued a few more steps when I heard a splash in the river below and saw something swimming like a wiggling arrow across the surface, before pulling itself up on the rocks. Sure enough, another water dragon.

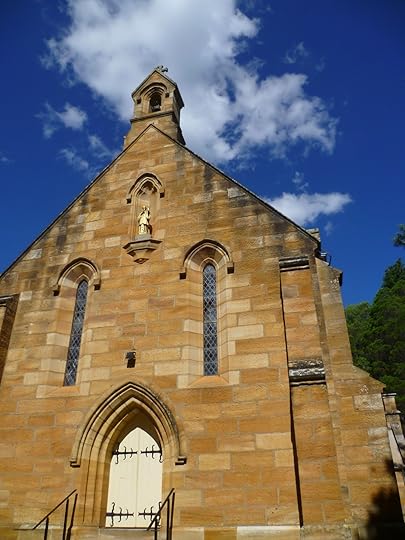

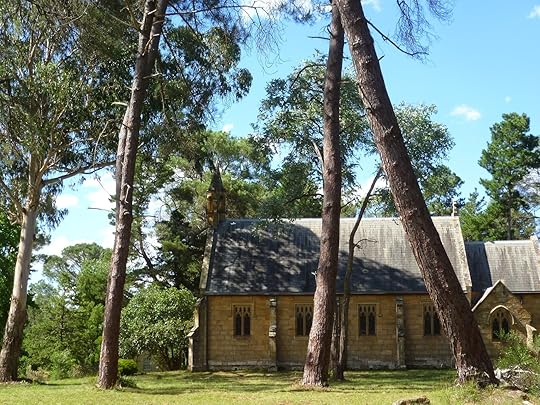

The trail was just at the back of the village, and soon I was looking at a church that made me feel I was back in Britain, except for the towering pines surrounding it. This was the Anglican church, built in a Gothic revival style from stone quarried where I'd been walking. Down at the bottom of the hill and across the bridge over the river, meanwhile, was the Catholic church with its golden statue set in the ochre stone, which – especially with the deep blue sky above, and the heady scent of more pines – reminded me of the south of France. Behind it was a loo where the management had thoughtfully placed a sign, presumably for the edification of the waiting. Father William McGinty had arrived in Australia, it said, in 1847 from Dublin, Ireland, and was appointed first pastor of Berrima district. St Francis Xavier church, designed by Augustus Pugin, opened in 1851. Then it seems McGinty deemed his mission in Berrima complete, as by the following year he was pastor of Ipswich, Queensland.

The trail was just at the back of the village, and soon I was looking at a church that made me feel I was back in Britain, except for the towering pines surrounding it. This was the Anglican church, built in a Gothic revival style from stone quarried where I'd been walking. Down at the bottom of the hill and across the bridge over the river, meanwhile, was the Catholic church with its golden statue set in the ochre stone, which – especially with the deep blue sky above, and the heady scent of more pines – reminded me of the south of France. Behind it was a loo where the management had thoughtfully placed a sign, presumably for the edification of the waiting. Father William McGinty had arrived in Australia, it said, in 1847 from Dublin, Ireland, and was appointed first pastor of Berrima district. St Francis Xavier church, designed by Augustus Pugin, opened in 1851. Then it seems McGinty deemed his mission in Berrima complete, as by the following year he was pastor of Ipswich, Queensland.

Berrima is in the heart of the lush Southern Highlands of New South Wales and today just 400 people live in the historic village in the curve of the Wingecarribee. It was rather grandly laid out in the 1830s in great confidence that it would become a county capital, and at one time had some dozen inns catering to horse-drawn traffic; there were bakeries and a market place and a military barracks. But it was by-passed, first by the railroad – the closest stop is Moss Vale, 9km away – and then by the freeway, which sadly is still audible at the quiet times of day, though hidden by dense forest.

Being by-passed was Berrima’s saving grace, for the sedate village now enjoys a status as one of Australia’s best preserved colonial pioneering settlements, strewn with pretty Georgian sandstone cottages with steep corrugated tin roofs.

Being by-passed was Berrima’s saving grace, for the sedate village now enjoys a status as one of Australia’s best preserved colonial pioneering settlements, strewn with pretty Georgian sandstone cottages with steep corrugated tin roofs. It has only one inn left, but a good one: Australia’s oldest continuously licenced inn, dating from 1834. It was first licenced to James Harper, a son of convicts who married a convict and became a police constable, set up the pub and then built himself a brick house now called Harper's Mansion, one of the most visited National Trust properties in the state. Perhaps Berrima's most famous building, though, is the gaol, completed in 1839 and still serving as a minimum-security prison. The second ever trial by judge and jury was held at the courthouse here, and the first man hanged at the gaol was the unfortunate Paddy Curran.

All of this, coupled with the fact that the Southern Highlands is a wine-making region and wineries abound nearby, makes Berrima a draw for tourists, with Sydney only an hour and a half away by car. Every other building seems to be a fancy ‘patisserie’, tea room or upmarket gift shop. The old general store has, like most, been turned into a café. My mission to buy food – since we’re lucky enough to be house-sitting here - was in vain. If we’d wanted to buy some hand-stirred jams, a wooden duck in boots or something made from alpaca wool, we’d have been all right.

All of this, coupled with the fact that the Southern Highlands is a wine-making region and wineries abound nearby, makes Berrima a draw for tourists, with Sydney only an hour and a half away by car. Every other building seems to be a fancy ‘patisserie’, tea room or upmarket gift shop. The old general store has, like most, been turned into a café. My mission to buy food – since we’re lucky enough to be house-sitting here - was in vain. If we’d wanted to buy some hand-stirred jams, a wooden duck in boots or something made from alpaca wool, we’d have been all right.

I was making my way around the park after my water dragon encounter, past the old bank and bakery (above), when I saw an ‘artist’s studio’. Through the open door I glimpsed what appeared to be a VW beetle painted with emus… I poked my head inside and was encouraged to come and look around. And thus I had my unforgettable encounter with artist Peter Browne. The paintings that covered the walls transported me out of leafy green Berrima - with its willows overhanging the lazy river - and into an outback Australia of searing heat, bare skinny gum trees and scrubland, with wooden shacks, lanky farmers, lankier horses and curious animals. The details made me laugh aloud, especially when I saw one called ‘Early Boat People’ showing a first encounter between Aboriginals and strangely dressed colonials clutching those rabbits that would go on to wreak such havoc.

I was making my way around the park after my water dragon encounter, past the old bank and bakery (above), when I saw an ‘artist’s studio’. Through the open door I glimpsed what appeared to be a VW beetle painted with emus… I poked my head inside and was encouraged to come and look around. And thus I had my unforgettable encounter with artist Peter Browne. The paintings that covered the walls transported me out of leafy green Berrima - with its willows overhanging the lazy river - and into an outback Australia of searing heat, bare skinny gum trees and scrubland, with wooden shacks, lanky farmers, lankier horses and curious animals. The details made me laugh aloud, especially when I saw one called ‘Early Boat People’ showing a first encounter between Aboriginals and strangely dressed colonials clutching those rabbits that would go on to wreak such havoc.

(c) Peter Browne Fine Art‘Well, you survived that!’ said the man at the table, who I guessed might be the artist, as I moved on from the first room into the second. We got talking, and he said some people asked him if he had any paintings of Berrima. ‘Why would I paint Berrima?’ he said. ‘It’s all English trees, English houses – what’s Australian here?’ He’d spent most of his time as an artist in the tiny settlement of Silverton, near Broken Hill out west, a place I’d tried to get a house-sit but had been thwarted by transport difficulties. I told him about the water dragons I’d seen on the trail.‘Did you see the wombat poo?’ I laughed and said no, but then I wouldn’t really know what it looked like. He Googled it for me. ‘Look! They're cubes.’ I looked. Remarkably, they were. ‘And they like to leave it in little piles on rocks. Kind of puts you off lamingtons,’ he said, referring to the cube-shaped Aussie chocolate cakes.After that, we talked about lots of things, mostly related to the sense of the absurd that shows up as detail in his paintings. He told me about the bush poet Banjo Patterson, who wrote Waltzing Matilda – ‘funny that we have a national anthem about a sheep thief’ – and how Spike Milligan lived for a while in Woy Woy and joked about his cork hat (for keeping off the flies), that ‘the bottles must have fallen off’. He told me he had noticed the news stations were excitedly reporting a shark ‘lurking’ off the coast – how do we know it was lurking? Was it loitering with intent? Maybe it was just swimming. The cute baby seal found on the steps of the opera house, though, wasn’t ‘lurking’, it was ‘basking’. Most visitors who came to the studio, said Browne, if they hadn’t come especially to see his work, were tourists who had only a few minutes to spend in each shop and were more in the market for a pot of jam. He was thinking of setting up a jam stall to cater to them too. Too many people only wanted to look at things they could buy. ‘Mall-itis,’ he called it.His banter about Australian culture, especially that of the Silverton area, was full of references that sounded to me wonderfully colourful and somewhat surreal, such as a Turkish ice cream man who shot at a train and started a war. And the wonderfully colourful and somewhat surreal, or eccentric, of outback Australia was all around me on the walls of the studio.

(c) Peter Browne Fine Art‘Well, you survived that!’ said the man at the table, who I guessed might be the artist, as I moved on from the first room into the second. We got talking, and he said some people asked him if he had any paintings of Berrima. ‘Why would I paint Berrima?’ he said. ‘It’s all English trees, English houses – what’s Australian here?’ He’d spent most of his time as an artist in the tiny settlement of Silverton, near Broken Hill out west, a place I’d tried to get a house-sit but had been thwarted by transport difficulties. I told him about the water dragons I’d seen on the trail.‘Did you see the wombat poo?’ I laughed and said no, but then I wouldn’t really know what it looked like. He Googled it for me. ‘Look! They're cubes.’ I looked. Remarkably, they were. ‘And they like to leave it in little piles on rocks. Kind of puts you off lamingtons,’ he said, referring to the cube-shaped Aussie chocolate cakes.After that, we talked about lots of things, mostly related to the sense of the absurd that shows up as detail in his paintings. He told me about the bush poet Banjo Patterson, who wrote Waltzing Matilda – ‘funny that we have a national anthem about a sheep thief’ – and how Spike Milligan lived for a while in Woy Woy and joked about his cork hat (for keeping off the flies), that ‘the bottles must have fallen off’. He told me he had noticed the news stations were excitedly reporting a shark ‘lurking’ off the coast – how do we know it was lurking? Was it loitering with intent? Maybe it was just swimming. The cute baby seal found on the steps of the opera house, though, wasn’t ‘lurking’, it was ‘basking’. Most visitors who came to the studio, said Browne, if they hadn’t come especially to see his work, were tourists who had only a few minutes to spend in each shop and were more in the market for a pot of jam. He was thinking of setting up a jam stall to cater to them too. Too many people only wanted to look at things they could buy. ‘Mall-itis,’ he called it.His banter about Australian culture, especially that of the Silverton area, was full of references that sounded to me wonderfully colourful and somewhat surreal, such as a Turkish ice cream man who shot at a train and started a war. And the wonderfully colourful and somewhat surreal, or eccentric, of outback Australia was all around me on the walls of the studio.

Published on January 17, 2015 01:01

December 24, 2014

Happy Holidays...

Bet you thought I'd be frolicking on an Australian beach and preparing to throw another shrimp on the barbie, mate. Well, so did I, but here on the south coast of New South Wales, the weather's a little patchy. Cloudy. I did go for an extremely swift swim in a very cold ocean, but I thought we'd all prefer to see some sunshine from around this time last year back in Tilos...

My heartfelt thanks to all of you for continuing to support the Octopus in my Ouzo and Falling in Honey this year. I've been using my time away to write a lot. I've also been having plenty of fun with pet-sitting adventures off the beaten track in New South Wales. I'll leave you with photos of some of the new friends I've made in the last few months.

My heartfelt thanks to all of you for continuing to support the Octopus in my Ouzo and Falling in Honey this year. I've been using my time away to write a lot. I've also been having plenty of fun with pet-sitting adventures off the beaten track in New South Wales. I'll leave you with photos of some of the new friends I've made in the last few months.

Warm wishes for the holidays, wherever you are!

My heartfelt thanks to all of you for continuing to support the Octopus in my Ouzo and Falling in Honey this year. I've been using my time away to write a lot. I've also been having plenty of fun with pet-sitting adventures off the beaten track in New South Wales. I'll leave you with photos of some of the new friends I've made in the last few months.

My heartfelt thanks to all of you for continuing to support the Octopus in my Ouzo and Falling in Honey this year. I've been using my time away to write a lot. I've also been having plenty of fun with pet-sitting adventures off the beaten track in New South Wales. I'll leave you with photos of some of the new friends I've made in the last few months. Warm wishes for the holidays, wherever you are!

Published on December 24, 2014 20:20

November 9, 2014

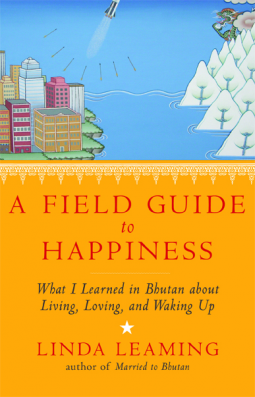

A Field Guide to Happiness

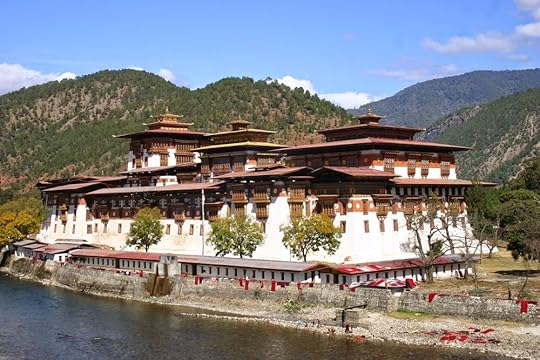

Linda Leaming has lived in the tiny Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan for much of her adult life and already published a memoir called Married to Bhutan. Her new book, A Field Guide to Happiness: What I Learned in Bhutan about Living, Loving, and Waking Up, explores how life can be happier in a remote place without all the trappings of modern life, the traffic and supermarkets and busy-ness; in a refuge relatively unpolluted by the rest of the world because of its remoteness.

Linda Leaming has lived in the tiny Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan for much of her adult life and already published a memoir called Married to Bhutan. Her new book, A Field Guide to Happiness: What I Learned in Bhutan about Living, Loving, and Waking Up, explores how life can be happier in a remote place without all the trappings of modern life, the traffic and supermarkets and busy-ness; in a refuge relatively unpolluted by the rest of the world because of its remoteness.Having moved to the tiny, isolated Greek island of Tilos to make my own life happier, I can relate. I read this book so quickly that it was almost over too fast. One of the things that makes Tilos special for me is the extreme ‘otherness’ of life there, compared to many parts of the world, which helps me to make the most of each day. I’ve given such things much thought since, through force of circumstance, I’ve spent most of this year temporarily living in Australia. Throughout Linda Leaming’s funny, interesting, thought-provoking book, I found myself saying, ‘Exactly…’

Living in Bhutan has made her think differently about pretty much everything, from time, work and money to nature, family and other people. And that isn’t because it’s been a walk in the park. Often it’s the challenges that have made her appreciate how simple happiness can be. She talks about losing your baggage, calming down and learning to breathe, illustrating each life lesson with Buddhist ideas and with smartly written, entertaining anecdotes from her life spent between Bhutan and her native Tennessee. With food, for example, the range of ingredients in Bhutan is limited; its remoteness means the shops ‘aren’t perpetually stocked’, and sometimes they have to make do. Yet they eat very well with what they have, and appreciate it. It’s satisfying, fresh, wholesome, natural. One of the things I’ve learned not to do in Tilos is to look at recipes for yummy things for which half of the ingredients will not be available. Better to buy what looks good, then make something from it; wondering what to have for dinner is not really something I need to think about, then. When I first arrived in Australia and could shop in large supermarkets again, the array of foodstuffs, rather than being exciting, left me baffled. How do you know where to start when you can have anything? The choice did not make me happier. Whereas in Tilos, the arrival of fresh vegetables after a winter storm has left us cut off for a week is a cause for celebration.

Living in Bhutan has made her think differently about pretty much everything, from time, work and money to nature, family and other people. And that isn’t because it’s been a walk in the park. Often it’s the challenges that have made her appreciate how simple happiness can be. She talks about losing your baggage, calming down and learning to breathe, illustrating each life lesson with Buddhist ideas and with smartly written, entertaining anecdotes from her life spent between Bhutan and her native Tennessee. With food, for example, the range of ingredients in Bhutan is limited; its remoteness means the shops ‘aren’t perpetually stocked’, and sometimes they have to make do. Yet they eat very well with what they have, and appreciate it. It’s satisfying, fresh, wholesome, natural. One of the things I’ve learned not to do in Tilos is to look at recipes for yummy things for which half of the ingredients will not be available. Better to buy what looks good, then make something from it; wondering what to have for dinner is not really something I need to think about, then. When I first arrived in Australia and could shop in large supermarkets again, the array of foodstuffs, rather than being exciting, left me baffled. How do you know where to start when you can have anything? The choice did not make me happier. Whereas in Tilos, the arrival of fresh vegetables after a winter storm has left us cut off for a week is a cause for celebration.

Leaming has a beautiful way of describing the simple pleasures of life. Walking in high mountains, she says, ‘slows me down mentally and diminishes the volume of my inner voice’. The simple matter of getting from A to B, with nothing to do but ‘relax in that feeling of suspension’, induces a meditative frame of mind. There’s a lovely story she tells about divorce mediation (not hers), which has absolutely nothing to do with lawyers, and which has a happy ending. There’s also a delightful story about sending her husband Namgay into town to buy a part for a washing machine, and him returning instead with a salad spinner. Although on the surface it’s an easy-to-read, funny and accessible guide to increasing your inner peace wherever you are, the book also subtly demonstrates that one country can be more conducive to happiness than others. Bhutan is famous for its Gross National Happiness, which Leaming explains was originally a whimsical comment made by the fourth king of Bhutan during an interview, but has developed into something more like a manifesto. Government policy is determined not purely by economic factors but by consideration for the environment and culture. Which brings her back to the point that for happiness, both on a large and a small scale, it’s important to decide ‘what’s important besidesmoney’. Clearly money alone doesn’t bring happiness, so why pursue it so doggedly? *

Leaming has a beautiful way of describing the simple pleasures of life. Walking in high mountains, she says, ‘slows me down mentally and diminishes the volume of my inner voice’. The simple matter of getting from A to B, with nothing to do but ‘relax in that feeling of suspension’, induces a meditative frame of mind. There’s a lovely story she tells about divorce mediation (not hers), which has absolutely nothing to do with lawyers, and which has a happy ending. There’s also a delightful story about sending her husband Namgay into town to buy a part for a washing machine, and him returning instead with a salad spinner. Although on the surface it’s an easy-to-read, funny and accessible guide to increasing your inner peace wherever you are, the book also subtly demonstrates that one country can be more conducive to happiness than others. Bhutan is famous for its Gross National Happiness, which Leaming explains was originally a whimsical comment made by the fourth king of Bhutan during an interview, but has developed into something more like a manifesto. Government policy is determined not purely by economic factors but by consideration for the environment and culture. Which brings her back to the point that for happiness, both on a large and a small scale, it’s important to decide ‘what’s important besidesmoney’. Clearly money alone doesn’t bring happiness, so why pursue it so doggedly? *

Having lived in several different countries, I find it fascinating to observe the subtle variations in the way people do things, and I’ve always tried to absorb lessons; that’s also why I love books by people who immerse themselves in different cultures and have challenging experiences. Did Leaming learn to enjoy life more by living in Bhutan? Part of it was simply her character and life happening around her, but being forced to reassess her values constantly helped put it into focus. When you’re always learning, your mind is alert to small differences. If you’re changing your whole life, it’s easier to change the way you do the small things. There are parts of the book that you may disagree with, which makes me think it’s an interesting pick for a book club. Linda and her husband, a Buddhist painter, spend part of their year in the USA, where Namgay has a weakness for buying gadgets. There was a jolt for me when she mentioned him using a leaf-blower, which strikes me as a piece of unnecessary baggage that has potential to infringe on other people’s happiness: I am happy to say my peace and quiet has never yet been torn asunder by the noise of a leaf-blower on Tilos – though it was torn asunder by plenty of other things. But one of the pleasures of this book is its idiosyncrasies and its tone; she’s not claiming to be perfectly happy or enlightened or to have all the answers. It’s a book that makes you think while it gives you pleasure, and for me that’s a five-star reading experience. Bhutan seems to inspire beautiful books; this one will go on the shelf alongside Jamie Zeppa’s Beyond the Sky and the Earth, and Britta Das’s Buttertea at Sunrise. I say ‘on the shelf’, but I mean it metaphorically as I currently don’t have any bookshelves. How’s that for getting rid of baggage? Instead I’ll keep it on my Kindle and read it again more slowly, calming down and taking time to breathe.

Having lived in several different countries, I find it fascinating to observe the subtle variations in the way people do things, and I’ve always tried to absorb lessons; that’s also why I love books by people who immerse themselves in different cultures and have challenging experiences. Did Leaming learn to enjoy life more by living in Bhutan? Part of it was simply her character and life happening around her, but being forced to reassess her values constantly helped put it into focus. When you’re always learning, your mind is alert to small differences. If you’re changing your whole life, it’s easier to change the way you do the small things. There are parts of the book that you may disagree with, which makes me think it’s an interesting pick for a book club. Linda and her husband, a Buddhist painter, spend part of their year in the USA, where Namgay has a weakness for buying gadgets. There was a jolt for me when she mentioned him using a leaf-blower, which strikes me as a piece of unnecessary baggage that has potential to infringe on other people’s happiness: I am happy to say my peace and quiet has never yet been torn asunder by the noise of a leaf-blower on Tilos – though it was torn asunder by plenty of other things. But one of the pleasures of this book is its idiosyncrasies and its tone; she’s not claiming to be perfectly happy or enlightened or to have all the answers. It’s a book that makes you think while it gives you pleasure, and for me that’s a five-star reading experience. Bhutan seems to inspire beautiful books; this one will go on the shelf alongside Jamie Zeppa’s Beyond the Sky and the Earth, and Britta Das’s Buttertea at Sunrise. I say ‘on the shelf’, but I mean it metaphorically as I currently don’t have any bookshelves. How’s that for getting rid of baggage? Instead I’ll keep it on my Kindle and read it again more slowly, calming down and taking time to breathe.

A big thank you to Hay House for the review copy. And to Linda for the use of her photos of Bhutan (that's Linda and Namgay in the photo above), and for sharing her thoughts and experiences in this book. Here's a link to her website: http://www.lindaleaming.com/

A big thank you to Hay House for the review copy. And to Linda for the use of her photos of Bhutan (that's Linda and Namgay in the photo above), and for sharing her thoughts and experiences in this book. Here's a link to her website: http://www.lindaleaming.com/(*note how I cunningly inserted a picture of a Bhutanese dog, clearly not in the slightest bit interested in pursuing money doggedly...)

Published on November 09, 2014 21:46

September 30, 2014

The Pet Project

On my last nights in Tilos back in mid-July, I slept on the terrace under the stars, and Lisa spent her nights either curled up on the comfy chair nearby, or waking me up by cracking bones with her teeth. Once she came over to where I was sleeping and nuzzled me through the mosquito net.On the final morning, waking at a few minutes to five, I took her for a morning stroll. There was a big full moon over the mountain of Profitis Ilias. Back home, I dragged my big suitcase out to the car, then came back and rubbed her belly while she gnawed on the old no-longer-stuffed toy (she took the stuffing out of it last time I left). When it was time to leave, she graciously accepted a treat to eat as I left, so I didn’t have to look at sad eyes, but a happy dog. Still, I didn’t really stop crying for her until I was halfway around the world.

On my last nights in Tilos back in mid-July, I slept on the terrace under the stars, and Lisa spent her nights either curled up on the comfy chair nearby, or waking me up by cracking bones with her teeth. Once she came over to where I was sleeping and nuzzled me through the mosquito net.On the final morning, waking at a few minutes to five, I took her for a morning stroll. There was a big full moon over the mountain of Profitis Ilias. Back home, I dragged my big suitcase out to the car, then came back and rubbed her belly while she gnawed on the old no-longer-stuffed toy (she took the stuffing out of it last time I left). When it was time to leave, she graciously accepted a treat to eat as I left, so I didn’t have to look at sad eyes, but a happy dog. Still, I didn’t really stop crying for her until I was halfway around the world.

Now, the whole point of our being in Australia, Ian and I, is to look after his mum. But that means being tied to her house, in a place on the South Coast of New South Wales that is very pretty but - a little way back from this spectacular coastline - has lots of houses and cars and not enough hills that you can get to without a car. OK, we’re pretty picky, after living in Tilos. We’re used to being free to move around a lot. We’re also used to having pets around; in my case, one demanding dog, in Ian’s case a large number of cats.I started dreaming of Tilos, and dreaming of Lisa; it didn't help that I was working on my new book and looking over old photos of her. Every day we walked up or down the coast paths, and were making friends with more dogs in the neighbourhood than people, almost. One day, walking back from the shops, I saw a dog running down the street and heard the man shout to it, ‘Katse kato!’ Are you Greek, I asked. Yes, he said, from Chios. He’d lived in Australia decades but still talked to his dog in Greek.Something needed to be done; we needed to go somewhere; we all needed a change of scene, as Ann, Ian’s mum, wasn’t happy staying at home all the time anyway. So it occurred to me that after my experience with house-sitters earlier this year when I needed someone to look after Lisa, we could do some house- and pet-sitting ourselves. I signed up to an Australian house-sitting website.It took a while to find the right assignments, but finally we started in mid-September in one of our favourite places, the Blue Mountains. Our first assignment was to look after five cats, seven chickens and a diamond python, which I thought sounded perfect. And it was. The hosts were happy for the three of us to stay. We were able to explore lots of new walks.

Now, the whole point of our being in Australia, Ian and I, is to look after his mum. But that means being tied to her house, in a place on the South Coast of New South Wales that is very pretty but - a little way back from this spectacular coastline - has lots of houses and cars and not enough hills that you can get to without a car. OK, we’re pretty picky, after living in Tilos. We’re used to being free to move around a lot. We’re also used to having pets around; in my case, one demanding dog, in Ian’s case a large number of cats.I started dreaming of Tilos, and dreaming of Lisa; it didn't help that I was working on my new book and looking over old photos of her. Every day we walked up or down the coast paths, and were making friends with more dogs in the neighbourhood than people, almost. One day, walking back from the shops, I saw a dog running down the street and heard the man shout to it, ‘Katse kato!’ Are you Greek, I asked. Yes, he said, from Chios. He’d lived in Australia decades but still talked to his dog in Greek.Something needed to be done; we needed to go somewhere; we all needed a change of scene, as Ann, Ian’s mum, wasn’t happy staying at home all the time anyway. So it occurred to me that after my experience with house-sitters earlier this year when I needed someone to look after Lisa, we could do some house- and pet-sitting ourselves. I signed up to an Australian house-sitting website.It took a while to find the right assignments, but finally we started in mid-September in one of our favourite places, the Blue Mountains. Our first assignment was to look after five cats, seven chickens and a diamond python, which I thought sounded perfect. And it was. The hosts were happy for the three of us to stay. We were able to explore lots of new walks.

I’ve just started my second assignment in the mountains, looking after a lovely dog called Major (I feel a little like Basil Fawlty calling ‘Major!’). This one I’ll do on my own, and will use the quiet time for working. On my first day, today, he enjoyed his walk around the neighbourhood but gave me that familiar sad-eye expression when I left alone to go into town. Then he only ate his own food when he was absolutely sure my own food wasn’t on the menu. Dogs!

I’ve just started my second assignment in the mountains, looking after a lovely dog called Major (I feel a little like Basil Fawlty calling ‘Major!’). This one I’ll do on my own, and will use the quiet time for working. On my first day, today, he enjoyed his walk around the neighbourhood but gave me that familiar sad-eye expression when I left alone to go into town. Then he only ate his own food when he was absolutely sure my own food wasn’t on the menu. Dogs!

We’re already booked in for two more assignments in the coming months, so we have plenty of new experiences coming up. I don’t think there will be too many dull moments.

We’re already booked in for two more assignments in the coming months, so we have plenty of new experiences coming up. I don’t think there will be too many dull moments.

I'm also posting stories also on the 'Australia' page of the blog, and photos on my Facebook page.

Published on September 30, 2014 03:02

August 24, 2014

A Walk to Plaka

Everything was packed and organised. Plaka was where I'd decided to spend 12 July, my last day in Tilos for months. I set out with Lisa in late morning. Walking by Elpida, the taverna by the sea where the road turns one way to Ayios Andonis, the other to Plaka, on impulse I stopped and bought dolmades se paketoto take to the beach for lunch. The clouds that had kept the day cool seemed to be clearing, and I might want to linger by the sea.

Everything was packed and organised. Plaka was where I'd decided to spend 12 July, my last day in Tilos for months. I set out with Lisa in late morning. Walking by Elpida, the taverna by the sea where the road turns one way to Ayios Andonis, the other to Plaka, on impulse I stopped and bought dolmades se paketoto take to the beach for lunch. The clouds that had kept the day cool seemed to be clearing, and I might want to linger by the sea.

The dolmades were warm as I wrapped them up and tucked them in my backpack. Sotiris, the taverna owner, sat down again on the terrace and asked about Yianni, when he was coming back from Australia. Not yet, I said. His mother needs him. But he wants to come back. I asked Sotiri to fill up my water bottle, needing enough for Lisa and me for the day.

The dolmades were warm as I wrapped them up and tucked them in my backpack. Sotiris, the taverna owner, sat down again on the terrace and asked about Yianni, when he was coming back from Australia. Not yet, I said. His mother needs him. But he wants to come back. I asked Sotiri to fill up my water bottle, needing enough for Lisa and me for the day.

The walk was beautiful; though it’s a road, not a footpath, there are hardly ever any cars. I kept Lisa on the lead so she couldn’t chase the goats. We passed the little monastery of Kamariani, where back at the start of the year I had arranged to meet Ian – known to locals as Yianni – for a walk to Plaka.

The walk was beautiful; though it’s a road, not a footpath, there are hardly ever any cars. I kept Lisa on the lead so she couldn’t chase the goats. We passed the little monastery of Kamariani, where back at the start of the year I had arranged to meet Ian – known to locals as Yianni – for a walk to Plaka.

After eight years in Tilos, he had to leave, he said, as his 82-year-old mum needed help. He would go at the end of January. We’d been friends since I arrived on the island but never close – strangely, as we both loved writing and books and walking. Until recently, I'd assumed the 'S' he wrote about in his blog was still his girlfriend; and on the other side of the mountain I'd been with my own S, though quietly I'd felt it wasn't to last.

After eight years in Tilos, he had to leave, he said, as his 82-year-old mum needed help. He would go at the end of January. We’d been friends since I arrived on the island but never close – strangely, as we both loved writing and books and walking. Until recently, I'd assumed the 'S' he wrote about in his blog was still his girlfriend; and on the other side of the mountain I'd been with my own S, though quietly I'd felt it wasn't to last.In the final days before he left, realising there might be something more between us, we got to know one another, walking to some of our favourite places in the hills and swimming in ice-cold sea together. And now, six months later, I was leaving Tilos too for a while. Why would anyone leave Tilos in the summer to go to Australia in the winter? For love, of course.

When Lisa and I reached the top of the track that leads down to Plaka beach, the sea looked clear and blue and perfect. I let her off the lead so she could run to the sea to cool off.

There'd been a fire at Plaka just a week before. My mum had been staying with me, and we’d seen the plume of smoke rising from the side of the mountain one day as we returned home. They’d managed to put it out quickly, dropping seawater from above, though that night we’d seen the red lights of the helipad still illuminated.

There'd been a fire at Plaka just a week before. My mum had been staying with me, and we’d seen the plume of smoke rising from the side of the mountain one day as we returned home. They’d managed to put it out quickly, dropping seawater from above, though that night we’d seen the red lights of the helipad still illuminated.

Now I made my way slowly down the rough track, surveying the fire damage. A large area of the park was charred to dark grey. The peacocks, I'd heard, had all survived. When I looked up from the beach, there was still a view of trees and green hillsides, but when I swam out into the sea, large blackened sections of ground were visible. It would probably take the winter rains to start things growing again.

Now I made my way slowly down the rough track, surveying the fire damage. A large area of the park was charred to dark grey. The peacocks, I'd heard, had all survived. When I looked up from the beach, there was still a view of trees and green hillsides, but when I swam out into the sea, large blackened sections of ground were visible. It would probably take the winter rains to start things growing again. People used fire sometimes to help things grow better, didn’t they? What can seem terrible damage one day… like what I’d done at the end of January… that was for the best, I hoped.

Along the beach was a scattering of hippyish Greek holidaymakers. I walked farther around to my favourite place, and found Lisa some shade to sleep in. I swam underwater over the posidonia, the sea grass that sustains so much sea life, as it flowed back and forth with the waves. Using Dimitris’ old mask, which his family gave me, I got up close to some of the fish: a skaros below me tilted its body a little to look up, then spotted me and shot away; a yermanos, mottled grey and white and black, had ferocious spines sticking up from its back although it was only half the length of my hand. I touched bright orange-red anemones and swam into shoals of tiny fish, and watched groups of others as pale and uniform as the Christian ichthus.

As Lisa and I walked back across the beach, peacocks stalked the sand, moving their heads back and forth under delicate tiaras. A couple of them flew up onto the crumbling gateposts as if pretending to be ornamental; then they stared at one another, and leaped down into the park.

As Lisa and I walked back across the beach, peacocks stalked the sand, moving their heads back and forth under delicate tiaras. A couple of them flew up onto the crumbling gateposts as if pretending to be ornamental; then they stared at one another, and leaped down into the park.

I considered what I love about Tilos: it’s rugged, wild, vibrantly colourful, diverse and yet empty, like living in a national park. Yet it’s small enough to get to know intimately, to see how the view changes from season to season, from morning to evening or depending on the way the wind’s blowing. It’s uninhabited enough – except for its roaming animals and underwater life – that you can believe it’s your own.

I considered what I love about Tilos: it’s rugged, wild, vibrantly colourful, diverse and yet empty, like living in a national park. Yet it’s small enough to get to know intimately, to see how the view changes from season to season, from morning to evening or depending on the way the wind’s blowing. It’s uninhabited enough – except for its roaming animals and underwater life – that you can believe it’s your own.Those last few days had been intense, with many powerful emotions coursing through me. But it was time to leave and continue getting to know the man who also loved this place in very similar ways, who loved being alone in the emptiest parts of the island and who also cried to leave it. At these times when I felt utterly in love with my surroundings, he was the only person I could really imagine walking and swimming with.

After I got back to Megalo Horio, I went to say goodbye to my landlord, Antoni, and he told me he wanted to keep the house for me when I returned, and that I should pass on his greetings to Yianni. As I walked up the hill, Vasiliki was at Kali Kardia and Lisa attacked her with love, holding her face in her front paws. Vasiliki said she’d make sure Lisa got to spend some time at their house over the summer with their dog Freddie. I couldn't take her with me, but she'd be happy at home with Stelios in Tilos.

After I got back to Megalo Horio, I went to say goodbye to my landlord, Antoni, and he told me he wanted to keep the house for me when I returned, and that I should pass on his greetings to Yianni. As I walked up the hill, Vasiliki was at Kali Kardia and Lisa attacked her with love, holding her face in her front paws. Vasiliki said she’d make sure Lisa got to spend some time at their house over the summer with their dog Freddie. I couldn't take her with me, but she'd be happy at home with Stelios in Tilos.Nikos and Rena were sitting outside the supermarket. ‘I’m leaving tomorrow,’ I said, and Nikos nodded to Rena, who went inside and came back, smiling, with the aluminium bottle that Nikos had asked me to take to Yianni. Ouzo. Nikos never tired of telling me how Yianni would hike up to the monastery in the rain or swim all the way across Ayios Andonis bay. ‘Tell him to come back sooner!’

I sat on my terrace looking out at the dark with a glass of wine, listening to the footsteps of people passing through the alley in front of the house, Lisa growling or barking at a person or a cat from time to time. I hadn't managed to see Michaelia before leaving; like so many people in Megalo Horio, she has relatives in Australia.

When Lisa and I arrived at Kali Kardia, it was busy with people from the village and for a while Maria sat down with me, pretending to be a customer so she could get off her feet. Michalis and Vasiliki invited me to join their table but understood when I said I wanted to sit alone tonight. Lisa had picked up on my mood and sat quietly, looking out over the balcony. When it was time to go, everyone wished me a good journey to Australia and sent ‘many, many greetings to Yianni’.

‘We are waiting for you!’ they shouted and waved goodbye as we walked up into the village.

So now, for a little while, ‘an octopus in my ouzo’ is based in Oz – as is that other Tilos blog, ‘when the wine is bitter’ – writing about Tilos and listening to Greek songs... I hope both will be back in Greece before too long.

Published on August 24, 2014 19:26

August 8, 2014

Courage to Lose Sight of the Shore

This may be a little hard to follow. Bear with me. In the long run, I hope things will be clearer.

My friend Fran, who once went to Crete for a holiday and stayed for ten years, wrote: ‘We must always trust and follow our hearts. It can take us to some very happy places.’

This year for me has so far been full of adventure, which is what I hoped for, after two years when – in spite of being in a place I love, living my dream life – I spent too much time having to be cautious as I fell pregnant and miscarried and then did IVF and, in spite of everything looking apparently excellent, didn’t get pregnant at all. I’d had enough of doctors and hospitals for a while.

People ask from time to time how Falling in Honey ‘ended’, and the answer is that it didn’t. The media, for whose interest I was certainly very grateful, wanted a story that ended with me ‘finally finding true love’. But my life is messier and more complex than newspaper stories (as if you didn’t know that). Most lives probably are.

There was an Epiphany on the sixth of January. There was happiness and there was sadness. Then, after saying I wasn’t going to Australia, I went to Australia for six weeks to try things out. I returned to Tilos for six weeks to pack up ready to fly back to Australia, with the plan that I’d stay until next year.

It wasn’t so easy. I almost couldn’t leave Tilos. I knew it was only temporary, but it was harder than I’d expected to cut ties for a while with the place that has been such a reliable source of happiness.

Someone wrote me a kind message about my book around that time, and wished me ‘smooth sailing’ and blessings on life’s journey. Then I saw on her website she had a quote from Andre Gide: ‘Man cannot discover new oceans unless he has the courage to lose sight of the shore.’

I booked my ticket. Greece would still be waiting when I returned. Lisa would be fine in my absence.

Michaelia asked one morning how I was, and I replied I was very well, but a little sad because I was leaving. ‘Look,’ she said. ‘If you’re just going to Australia for a holiday, then don’t go. But if you’re going for something more serious,’ which she knew I was, ‘why not?’

Knowing I’d be gone for a while intensified my feelings for Tilos, brought them into focus. For the last week, I gave up trying to work and simply made the most of every single day, walking as far as I could. I slept outside on a mattress on the terrace, under the stars. Crows woke me at dawn. I drank fresh lemonade made from the lemons that fell off the tree every day. The kitchen smelled of melon. There were beach days and taverna nights.