To Partheni

On my third day on Leros in late February, I was feeling drawn to the farnorth of the island. Its main settlement was Partheni: ‘Virgin’, named probablyfor an ancient cult of Artemis, or an older goddess. The whole area was one of the emptiest spaces on the Leros map, one of the most untouched parts of Leros, cutoff from the bay of Alinda by the limestone peak of Kleidi.

It was a warm day and I’d swum in the morning and worked for a while on the shady terrace, my feet in the sun, while Lisa lounged on her bed. The electricians were drilling. One shouted a question and the other responded, ‘Logika!’, meaning something like ‘probably, should be’ – it seemed a vague sort of answer to a question about electrics.

While the road to the airstripled all the way north, I decided to take a more winding route over a green hilltopped by the church of Ayios Kyrikos. We passed some new development thatseemed out of keeping with the local styles, but also donkeys and horses with coloured tassels ontheir halters. Rounding the hillside, I was stopped in my tracks by the view below:of course it hadn’t been marked on the map, but there was a huge army base. Iknew part of Partheni was a military zone. I descended on the track, checkingwith the armed young guys at the gate that I was on the right path.

The valley ended at a raisedwall, the dam of a failed reservoir project. The new, empty road curved aroundand beyond it was the airstrip, ending at the sea beside a dry dock for yachts,and more military buildings. The sea beyond – Partheni bay, protected byArchangelos islet – was completely smooth and calm, like a lake, with fish farmsand a scattering of fishing boats. The whole place felt strangely quiet, which added to the intrigue.

In fact, strange is exactly howit should feel. Leros has a fascinating modern history – an extraordinary centurythat belies its current calm and beauty. I knew a little, but over the comingweeks that I would end up spending on Leros, I realised just how steeped the wholeisland is in its remains. A café owner would say to me, ‘We are known for somany bad things… When will we be known for good things?!’

A little history is in order,then. In July 1923, at the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, Turkey gave upits claims on the Dodecanese islands, populated by Greeks for millennia; Italy had ‘liberated’ the islands fromTurkey in 1912, and in 1922 Mario Lago was appointed Governor of what were now designated the ‘Italian islands of the Aegean’. The Italians decided the port at Rhodeswas too small for its Royal Navy, and in 1923 started to build up a base aroundthe sheltered, deep bay at Lakki on Leros. Since the island garrison comprised manythousands of men, over the 1920s and 1930s they built a new model town withstraight, wide streets and Rationalist art deco architecture, much of it stillstanding, called Porto Lago.

‘Imagine,’ Takis, a businessowner in what is now called Lakki again, told me later. ‘We were five thousandpeople then, and there were thirty thousand military personnel on the island atone time. But this is not written in the Greek history books because then wewere part of Italy.’

There’s much to tell about thisphase, but crucially, little Leros had a bay suitable for re-fuelling submarines,a strategic base that would allow aircraft to reach the Middle East, and a vastnumber of Italian military personnel. So in the Second World War, when all the Dodecanesewere battlegrounds at one point or another, Leros was a critical target, and thereare military remains in every part of the island.

Someone told me: ‘The Battle of Crete – not to diminishit – lasted one week. The Battle of Leros lasted fifty-two days. Constantbombardment.’

I followed the road around to thebay of Blefouti, unprepared for its sheer loveliness: a wide sweep of pale bluesea fringed by beach, mostly backed by lush fields sweeping up to the mountain. And I seemed to have the whole place to myself, thoughalas, only a couple of hours before dusk. I spotted what looked like acrumbling Italian observation tower on the top of the far headland, and went toinvestigate. I hadn’t come to Leros to look for war remains, yet I couldn’t help being fascinated by the abandoned buildings.

The empty road gradually gave wayto dirt track and on the slope was a large, somewhat grand building with aportico of tall arches and a large Mediterranean pine outside. This was theremains of battery Pl.899, shown on a 1940s Italian map as antinavy eantiaerei – now clearly used by a farmer to shelter his goats. We saidhello as he carried a bale of hay up the hill, his dog at his heels, the sheepand goats clamouring down the hillsides to follow him.

For now, I had to head back. Wetook a shortcut to avoid some barking dogs, and I stopped to chat with a man ata closed taverna, then we walked down the wide, empty, tree-lined road, pausingat an old double chapel with beautiful icons between a cement works andbuilding materials suppliers. A car pulled up so close I thought it might hitus, then a man with a beaming smile wound down his window and said, ‘I’mlistening! First impressions of Leros!’ It took me a moment to realise he wasone of the guys from the other night at the grill house.

Further down the road, I passed ayoung guy on a motorbike leading two ponies on ropes up the road. I stopped tobuy fresh eggs and local beer from Stamatia, and told her I’d walked toPartheni. She looked at me as if I was mad, then related a long story about herboyfriend’s animals, the only part of which I really understood was aboutslitting their throats… I was loving Leros, and staggered back to the room to readmore about it.

A week or so later, I went backto Partheni, for two reasons. The first was to pick up my mum, who was arrivingon the 7 a.m. flight from Athens. I’d just arrived atthe airport and got out of the car I'd rented when I heard the roar of the little plane comingin overhead. It pulled to a halt just before Partheni bay, then trundled backto the terminus. The passengers were out within minutes, and the airport would soon be closed again for a few days.

Later, after breakfast at thebakery in Kamara, I took Mum to see lovely Blefouti. The hills behind the baywere largely unspoiled; a few houses here and there, an organic vineyard hiddenin a fold of hills with grazing cows. In a little cove, I now recognised arusted old bit of metal as some kind of artillery.

But what I really wanted to seethis time related to a later piece of modern history. We left the car at thestart of a headland and walked above the fishing harbour, and I asked a farmer feeding goats with huge, twisted horns if we were heading the right way for Ayia Kioura.

After the Second World War, Leroswas liberated and with the rest of the Dodecanese became officially part ofGreece, though the country was immediately divided by Civil War, those who hadresisted the Germans now seen as the ‘Communist’ enemy by the right-wingestablishment. Then in 1967 there was a coup by the army, starting the Regimeof the Colonels, or the Junta dictatorship. Manyleft-wing intellectuals and artists were sent into exile on little islands. Between 1967 and 1974, political prisoners were detained at the old Italianbarracks at Partheni.

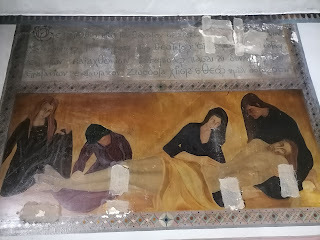

Among the ‘kratoumeni’ on Leros was Manolis Glezos, politician, author, hero, best known for taking down theNazi swastika from the Acropolis in 1941. The eighteenth-century chapel of Ayia Kioura Matrona, built on the site of an older chapel and situated a kilometre away from the camp, had fallen into ruin and Glezos organized a fewartists among the prisoners to restore it and paint new frescoes.

Work beganin 1969 with the support of the islanders. The artists used fellow prisoners asmodels. The soft, flowing, haunting figures exude a sense of peace, thelarge eyes full of emotions: true sorrow and bright hope, mourning perhaps not onlyChrist, but Greece.

The works are fifty years old, and some plaster has fallen, revealing rusting iron bars inthe ceiling; many paintings had rough patches of gauze stuck to them. Iwondered if the prisoners would not have had access to the proper materials.Then as I looked for a light switch, I noticed a sign by the door in Greek,prohibiting something odd: asvestoma. The use of lime.

I foundout later: after the regime changed, certain conservative islanders decided tolime over the unorthodox frescoes. But they’re now protected by the state as animportant monument.

Political activist and poet Yiannis Ritsos was also imprisoned on Leros at that time. One of his most famous works is 18 Little Songsof the Bitter Homeland, later set to music by Theodorakis; sixteen of them,he said, ‘were written in one day – on September 16, 1968 – in Partheni ofLeros’.