Gary Neal Hansen's Blog, page 40

October 19, 2016

Why is Christ Seated at the Right Hand of God? (Heidelberg Catechism Q50)

Why “Seated at the Right Hand of God”?

Why “Seated at the Right Hand of God”?I’ve been back to blogging on the Heidelberg Catechism of late.

Recently I worked through what these 16th-century Reformed theologians thought about the Ascension.

In their line by line commentary on the Apostles’ Creed they took each obvious and not-so obvious issue in turn:

Q46: What does Christ’s Ascension into heaven mean?

Q47: Does that mean he’s not with us?

Q48: Does that separate his humanity from his divinity?

Q49: And, from a while back, how does this idea help us as Christians?

Then the writers move on to the Creed’s next line and ask

50 Q. Why the next words: “and is seated at the right hand of God”?

Good question, even if basically nobody is asking it today.

So, now that we are on the topic, why DOES the Creed say that?

The Easy Answer: The Bible Says So

I suppose the easiest answer is “Because the Bible says so.” Remember how Stephen, as the crowd pumelled him to death with stones, looked to heaven and said that he saw Jesus sitting there?

But filled with the Holy Spirit, he gazed into heaven and saw the glory of God and Jesus standing at the right hand of God.

‘Look,’ he said, ‘I see the heavens opened and the Son of Man standing at the right hand of God!’ (Acts 7:55-56)

Okay, I guess he got tired of standing there and sat down.

Actually most of the references refer to him sitting. (Matt. 26:64, Mark 14:62 & 16:19, Luke 22:69, Col. 3:1, Heb. 1:3, 8:1, 10:12 & 12:2)

And there is another simple answer: If he bodily rose from the grave and bodily ascended to heaven, he has to be bodily somewhere.

Complication: What is the Father Doing with Hands?

But then a different problem arises: God is not physical. God, according to Scripture, is Spirit, and by Church teaching the Father is not to be portrayed in physical ways.

cc by Blake Patterson 2.0

cc by Blake Patterson 2.0You see this in the ancient Temple.

The Holy of Holies was the definitive place where God chose to be present.

It housed the Ark of the Covenant, holding the Ten Commandments.

Two golden angel figures stretched out their wings above and across and the Ark, forming a kind of seat for God.

The seat was, to all appearances, empty.

You would expect God to be sitting there on the, as it were, wing chair. But no.

And one of the commands on the tablets inside that Ark clearly forbade making any physical portrait of God.

So when the New Testament’s idea of the heavenly throne room, what is God doing with hands?

The trouble with the idea is called “anthropomorphism”: falsely attributing human characteristics to God. So there is a problem in the picture that the language of the Creed (and Scripture) creates.

(Though it does make room for the old joke about God being left-handed — since Jesus sat on God’s right hand.)

The Symbolic Answer: Christ Is Ruler of All

This word picture of God bodily occupying a physical throne room has to be symbolic language. It must point to a greater, invisible reality.

So here’s the Catechism’s take on the question:

A. Because Christ ascended to heaven

to show there that

he is head of his church,

the one through whom the Father rules all things.

Yes! The word picture of enthronement points, as a symbol, to a bigger truth. And it is an important reality:

Christ is large and in charge, the ruler of all, and especially the head of his Church — us.

This idea of Christ at God’s right hand is what you see portrayed inside the domes of countless Orthodox Churches: Christ “Pantokrator” or “Ruler of All.”

So when you say the Creed, or think about Christ after the ascension, remember that the imagery teaches us he is King of King and Lord of Lords — and let that fill you with trust and hope, whatever you are facing.

————

I’d love to hear your thoughts about Christ’s sitting at the right hand of God in the comments.

And if you enjoyed the post, please share it on Facebook or your favorite social media using the buttons below.

The post Why is Christ Seated at the Right Hand of God? (Heidelberg Catechism Q50) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

October 17, 2016

Upcoming Webinar on Lectio Divina

As I write, it is mid October. From my kids’ perspective two things stand between now and Christmas: Halloween and American Thanksgiving. (In our house we have already celebrated Canadian Thanksgiving. Multiple cultures make for extra thankfulness.)

As I write, it is mid October. From my kids’ perspective two things stand between now and Christmas: Halloween and American Thanksgiving. (In our house we have already celebrated Canadian Thanksgiving. Multiple cultures make for extra thankfulness.)

For the Church, though, there is another whole season between now and Christmas: Advent, the four week period when we prepare ourselves for the coming of Christ.

Now let’s think about it:

Does Advent usually work for you as a time of spiritual preparation?

Do you really get to deepen your engagement with God, and reflect more deeply on your life?

Does anything happen to invite you into communion with God through scripture and prayer?

I don’t know about you, but I’ve spent many a December consumed by

shopping

grading

and too many office parties.

Not to mention the endless stream of secular Christmas songs in the stores and on the radio.

I’d like to make this year’s Advent different for both of us.

And the Presbyterian Outlook would like to help.

Join Me for a Webinar on Lectio Divina

The good folks at the Presbyterian Outlook regularly host webinars. They have asked me to lead one on November 1 on the classical Christian spiritual practice of “lectio divina.”

If you are not familiar with the term, lectio divina means “divine reading.” It is an ancient way of prayerfully engaging with Scripture to move reliably into the life-changing presence of God.

In the webinar I’ll introduce the classic practice (as well as some modern versions) and get you ready to roll using lectio divina on biblical texts about the coming of Christ this Advent.

Here’s a little video intro I did for the Outlook’s registration page:

The Outlook is not the only group wanting to help you out. The generous folks at the Omaha Presbyterian Seminary Foundation are providing funds for a limited number of scholarships. So if the fee for the webinar is standing in the way, make an inquiry using the link on the registration page.

The button below will take you to the page where you can register:

The post Upcoming Webinar on Lectio Divina appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

October 13, 2016

Reading Scholarly Studies (Letters to a Young Pastor)

cc by Stewart Butterfield 2.0

cc by Stewart Butterfield 2.0Dear ______:

Sorry for the delay in writing back. What can I say? I was swamped.

I’m glad to hear your classes are also requiring you to read things that aren’t primary sources, and aren’t introductory text books.

The interesting stuff in any field is happening in the current scholarship: the monographs and articles. These are likely to be assigned only in your more advanced elective courses.

How should you read current scholarship?

In a word: Strategically.

Reading Scholarly Studies

You need to learn how scholars present their work in publications. You can use your time best by reading according to the conventions of the genre. In a sense you should (ahem.) study studies rather than simply reading them.

Of course you could approach them the first grade way: start with the first sentence, plow on, sentence by sentence, mouthing each one silently in your head, till you get to the end.

The problem with that is you’ll be bored, you’ll be lost, and you’ll miss the very interesting and useful stuff that the author slaved over for years.

A Sample Case

To highlight the need for a strategic approach, imagine the following:

Let’s pretend you have a seminar in a seminar on American Church history. This week the class will spend its three hour session discussing E. Brooks Holifield’s God’s Ambassadors: A History of the Clergy in America.

The first problem is you didn’t actually read the book. The week was a total washout.

The second problem is there are only seven people in the seminar. Your silence will be noticed.

Third problem: your class starts at 2:00. It is now 1:00.

In this scenario you would be totally sunk with the first grade reading strategy. How will you make use of that one precious hour?

Time for strategic reading, aka “academic triage”

The clock is ticking.

Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsThink back to a M.A.S.H. rerun: Suddenly overrun with wounded soldiers, Hawkeye and the gang had to think quickly about who to treat in what order and in what way.

That’s triage. They offered medical care strategically to save as many as possible.

So let’s triage your reading so you get as much learning as possible. Let’s see how much class preparation you can squeeze into your single, seemingly inadequate hour.

1:00. Read the Syllabus.

First figure out what you should be looking for in the assigned book. This book covers Protestant and Catholic clergy for about three centuries.

Your syllabus shows you two important things:

Unlike the book, the class focuses only on Protestantism.

In this part of the semester you are dealing with the late 19th century.

Discovering that took about a minute. It saved you hours. You’ll see.

Take another minute to think up questions about Protestant clergy from 1850 to 1900. What would be interesting to know? You might want to jot the questions down.

1:02. Read the Cover.

Of course you should not judge a book by its cover. But the cover of an academic book can teach you a lot.

The publisher may not have invested heavily in the picture on the front, but you can bet they worked hard on the back.

You’ll find three things on the back that are worth a few minutes of your triage time.

First you’ll find a brief author bio. That can help you put the book in context.

Is the book is by a prominent scholar with a weighty record of publications and awards?

Or is it by someone young, fresh from grad school?

Does the author work at a top university where research is the major focus?

Or is the author on the faculty of a small sectarian school that will only support a party line?

Just take it in. Know who you are dealing with.

Second you’ll find a brief summary of the book, probably by the author. One or two paragraphs will tell you about the main question that prompted the book, and give you some hints as to its main conclusions.

This may not be the stuff that lures bookstore browsers to drop $32, but for you it’s gold. Read it twice. Now you know what the book is about.

Third you will find what are technically called “endorsements” but are usually referred to as “blurbs.” The publisher will have sent advance copies to reasonably well-known scholars in exchange for a few complimentary sentences.

This too is gold for you. The blurbs tell you what smart people in the field say is good about the book.

Well those were four well-spent minutes. What’s next?

1:06. Read the Table of Contents.

Now open the book, but don’t start reading. Starting to read now would be like driving off for your vacation without either a map or a GPS. You need to know where you are going.

Head for the Table of Contents. This is your official map to the book. Take a few minutes and study the chapter titles and subtitles.

Ask yourself two questions:

First, what do you learn about how this author approached the topic at hand? The book has a structure, and the flow from chapter to chapter is intended to teach you about the subject.

Second, and most important, which chapters are relevant to you? It may all be interesting. It may amount to an integrated argument that hangs together brilliantly.

But from what you saw in the syllabus, only one chapter is clearly relevant:

5. Protestant Alternatives, 1861-1999.

Good thing you read the syllabus and the map first. You just saved yourself hours and hours.

Or rather, since those hours were gone before you started, you just figured out how best to spend the last 50 minutes before class.

1:10. Skim the Introduction.

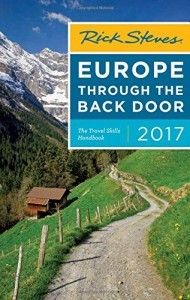

You may be tempted at this point to jump to chapter 5. Don’t. First find a tourist’s guide book.

When you plan your European vacation, you pick up a travel guide. It helps you know a bit of history, a bit of geography, famous places, good restaurants — all kinds of stuff. It helps you make good use of your vacation time.

When you plan your European vacation, you pick up a travel guide. It helps you know a bit of history, a bit of geography, famous places, good restaurants — all kinds of stuff. It helps you make good use of your vacation time.

In an academic book, the Introduction is like your travel guide. It may be dry but it is there to help you.

This is how academic books are organized, so work with me.

You don’t have time to read the whole Intro. Do a strategic skim.

Read the first paragraph. It is likely to orient you to the book and its purpose.

Then read the first sentence of each paragraph. The people who write academic studies did well in high school English. They learned that every paragraph needs to start with a topic sentence, followed by the supporting information.

So skip the supporting information. Just the topic sentences will take you through the main argument.

Eventually you will find the place where the author gives you either a sentence or a paragraph summarizing every chapter of the book. This too you should read.

Then read the last paragraph of the introduction were the author tells you why the book is worthwhile.

Those 15 minutes gave you a much richer sense of the book as a whole.

Do you see what you’ve been doing?

The cover gave you a bird’s eye view.

The Table of Contents gave you a map.

The introduction served as your tourist guide.

Every step has oriented you at a deeper level.

Now you are ready to read. Sort of.

1:25. Skim the Crucial Chapter(s).

Finally it is time to read chapter 5 — or whatever section of your actual book you now know to be most relevant to your purposes.

Don’t make the mistake of bringing out your old first grade reading strategy.

Instead, do what you just did with the Introduction. Skim.

Read the first paragraph to orient yourself to what is coming.

Then flip to the end and read the conclusion to find out what the author thinks were the chapter’s most brilliant insights.

Then go back to the beginning and read the first sentence of every paragraph of the chapter.

Look back to the questions you jotted down in minute 2, after looking at your syllabus.

Any answers emerging?

Any observations you can add?

Any questions you wish you could ask the author?

With almost half of your minutes left to go, you are already much better prepared for class than you thought you would be.

By triaging the book according to the standard form of an academic publication, you quickly got enough of what you needed to make it through class without embarrassment.

What will you do with your last 25 minutes?

1:35. Read the Crucial Portions.

Now it really is time to read. But read selectively.

Because you triaged your book so well, you know what parts of the crucial chapter are really useful, really interesting, or really confusing.

Go back to those sections. Read them line by line. Make a few summary notes. Jot down some questions you might ask your professor and your fellow students.

If time permits read the first and last sections of the other chapters.

1:50. Skim Other Interesting Bits.

Hey look! You still have ten minutes to go. What will you do?

You have now become aware of other important parts of the book. There is material on the relevant period and topic scattered in other chapters.

Go and find that stuff, and skim what you can. Just take it in, becoming aware of as much as you can.

2:00. Now go to class.

You are actually pretty well prepared. You might even be better prepared than if you’d spent the week trying to read every sentence in order.

Take your book and your page of notes to class. You’ll find that you have useful things to say when the prof calls on you. You may have some things you are really eager to share. Or you may want to ask those questions you jotted down.

And you have every right to participate. You read the assignment.

You didn’t read it by a first grade standard. You read it by a graduate school standard.

What if you still have a whole week to read the text?

Hopefully most of the time you won’t have to triage your readings at the last hour.

What will you do, though, if you have a whole week ahead of you before discussing the book in class.

Will you bring back your first grade standard and plow through line by line?

No. Please, no.

Read like a good little graduate student. Take the first hour of your study time, a week before the class, and do that very same triage you would have done if you’d put studying off to the last hour.

After triage, you will be able to spend the week studying the details — and much more effectively. If you have multiple hours to invest in preparing for class, you can spend them really well, getting to know it at a much deeper level.

Happy reading,

Gary

————

I’d love to know your thoughts on this kind of reading in the comments.

And if you found the post helpful I hope you’ll share it!

————

This post contains affiliate links.

The post Reading Scholarly Studies (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

October 12, 2016

Why Do We Have To Die? (Heidelberg Catechism Q42)

cc by Giulio Menna 2.0

cc by Giulio Menna 2.0Why do we have to die?

Most human beings have asked the question. It cuts deep when you are facing a loss, or facing your own mortality. Or when you are a kid, trying to figure out the basics.

Why do we have to die?

The Heidelberg Catechism (that globally and historically popular, but locally and currently ignored, Reformed summary of biblical Christianity that I’ve been blogging on since its 450th anniversary) asks the question directly, but with a slight theological twist.

It comes up partway through the Catechism’s explanation of the Apostles’ Creed. The Creed says Jesus died, and they explain that his death was for us, to save us from condemnation.

So at question 42 they ask,

Q. Since Christ has died for us, why do we still have to die?

Put it that way and it can sound oddly, dryly theoretical.

And the answer may seem simple: Of course we die. All creatures great and small eventually die.

So if it seems like a theoretical query, look deeper; listen to your heart instead of your noggin.

A Paradox

Any Christian who has been around a while has faced the puzzle. It comes across as a paradox really, a seeming contradiction between core teachings and personal experience.

First the teaching: Christ has conquered death.

You hear it most emphatically if you ever attend an Orthodox church in the season of Easter:

Christ is risen from the dead

Trampling down death by death

And upon those in the tombs bestowing life!

You sing it about a thousand times, actually.

Scripture is no less insistent on the point:

‘Death has been swallowed up in victory.’

‘Where, O death, is your victory?

Where, O death, is your sting?’

The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law. But thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ. (1 Cor 15:54-57 NRSV)

Second, the experience: death happens

Everyone who has lost a loved one or faces a terminal diagnosis hears that teaching and cries out,

Death stings right here. It stings a lot, actually.

It feels very much like death has had the victory.

But seeing and feeling the paradox doesn’t usually mean we have lost our faith. It means we have a puzzle to solve on our way back to stronger faith and joy.

Is Death Conquered?

The Catechism doesn’t dive into the existential crisis, the emotional black hole of death.

Maybe that’s a fault, I don’t know. Does any doctrinal statement of any denomination?

Instead our Reformed theologians of 1563, concerned as they are with how Christian teaching is helpful to us, comforting, and encouraging at every turn, keep their theological focus on the purpose of Christ’s death:

A. Our death does not pay the debt of our sins.

Rather, it puts an end to our sinning

and is our entrance into eternal life.

From the Catechism’s perspective, the ultimate problem for us all is sin.

We’ve gone the wrong way in God’s world. We need God’s forgiveness. Our death does not solve that ultimate problem.

Christ’s death did that — which opened the door to eternal life for us.

Problem solved.

But the whole world still deals with the consequences of humanity’s sin.

The consequence is, first, death itself. Death is what God said would happen if humanity made the wrong choice (Genesis 2:16-17). We all still face it.

And so we die, as part of fallen creation — and you might say we can’t actually step through the door Christ’s death opens until our own death comes.

But the second consequence of humanity’s sin is our brokenness — our deep-rooted tendency to make more bad choices.

If this life didn’t end, neither would our string of bad choices. As Christians we struggle with our lack of holiness, our continual need to ask forgiveness. Death breaks the cycle with the transformation we long for.

————

I’d love to hear your thoughts on why we have to die, or on the Catechism’s answer to the question. Please leave a comment!

And if you found the post helpful, please share it using the buttons below.

The post Why Do We Have To Die? (Heidelberg Catechism Q42) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

October 10, 2016

Between Obscurity and Fame (The Writer’s Inner Life)

When I posted about the writer’s battle with “the demon of futility” I mentioned the frustration that can come from identifying yourself as a writer.

When I posted about the writer’s battle with “the demon of futility” I mentioned the frustration that can come from identifying yourself as a writer.

People ask what you’ve written. They’ve never heard of it. They’ve never heard of you.

In a way this is perfectly natural:

A book can be a success by any reasonable standard without appearing on the New York Times bestseller’s list.

Or the USA Today bestseller’s list.

Or even without getting one of those gorgeous little orange flags on Amazon.com.

Obscurity and Fame

A lot of people have dreams of fame. Some think the way to fame is to write a book. I say

Do the math.

So, what if something you wrote did become a bestseller?

Screen Shot 2015-11-17 at 10.35.44 AM

Screen Shot 2015-11-17 at 10.35.44 AMWhat then?

Well, first of all

Woot woot!

But then after that,

What of it?

It is always a matter of fame and obscurity.

Do the Math

Say you score that big league victory. You hit the New York Times Bestseller list. That means your book sold something like 10,000 copies in that particular week.

(My little orange Amazon flag came from less than that, by the way. Way less than that.)

How well known is your work after such worldly success?

Well if there are 300,000,000 people in America, and 10,000 now own your book, you have potentially impacted 0.0033% of the population.

Odds that the person you just randomly met will know your work? Very small.

Fame or Approval?

What lurks behind the desire for fame is a desire to be praised. We are fighting our own sense of inadequacy. We don’t feel we are good enough in some deep down existential way. We want others, the world at large, to say we are worthwhile.

The Desert Fathers and Mothers of 4th century Egypt had to wrestle with their own desire for fame and accolades. They didn’t seek approval. They avoided it.

Here’s a saying from one of Benedicta Ward’s translations that I really like:

They said of Arsenius and Theodore of Pherme that they hated fame and praise more than anything.

Arsenius avoided people likely to praise him.

Theodore did not avoid them, but their words were like daggers to him.

8.3, “Nothing Done for Show”

Motives are always mixed. In some proportion, these ancient monks who fled the world wanted to impress others.

They fought that portion of their motives.

If others approved of them it was a problem. It gave the wrong kind of satisfaction. It pleased the wrong part of them.

It made them happy about something other than progress.

Whataya gonna do? Live in a way that people DON’T approve of? No.

The monks had to stay true to their calling. That calling increased qualities that lots of people admired.

And at the same time they had to avoid getting their vanity flattered.

These two chose to do that in two opposite ways. In the process they give us two (truncated) strategies.

Arsenius kept away from people to stay focused.

Arsenius chose the easy way. If he interacted with people, their praise would make him complacent. He needed to keep his eyes down and stay in his cell.

That works for the writer who just keeps writing. He hunkers down and does his art. When he gets published he doesn’t read the reviews and doesn’t give interviews. He moves on to the next project.

Better, though, to say it might work if you are very well established, or if you happen to have written a runaway bestseller, or if you don’t mind being extremely poor.

Most writers, artists of all kinds, have to interact with the world or nobody ever finds their work.

Theodore interacted with people and kept focused.

Theodore chose the harder way. Rather than relishing the praise, he kept himself aware that praise was not his goal — in fact it was a temptation. It was painful to constantly set affirmation aside and get back to his calling.

That works for the writer who knows she needs to be involved with readers. She knows that interviews lead to book sales, and finding readers is crucial.

But if she stops and feels satisfied with the attention, she slacks off. Her next book only gets her second-best effort. Maybe she doesn’t even write it.

Listening to fans and critics she has to wrestle with her motives all the more regularly.

Fame or Service?

Fame is sort of a silly goal anyway. You can’t spend it. And it would be inconvenient much of the time.

For most of us the best stuff we do is for an incalculably small audience.

I know a lot of pastors. Some of them are great preachers.

But most preachers do their best work for a group of a hundred or so people.

Week in, week out, they hone their understanding of God’s grace in Christ as found in Scripture.

Week in, week out, they shape that message to best impact the lives of a particular community.

In a modest-sized town, only a small percentage of the people will ever be there to hear even a single sermon.

But these preachers really help people: If you listen to excellent, thoughtful preaching Sunday after Sunday it can change your life.

It can seem paradoxical:

The number impacted is discouragingly small.

But the size of the impact can be incalculably great.

Like a faithful preacher, a writer has to think about making an impact on a small portion of the vast number of potential readers. I have to help whoever happens to, in the words of the angel to St. Augustine,

Take up and read.

Set your sites on fame and find yourself in futility.

Set out to help people and you might just find yourself an audience.

————

I’d love to hear your thoughts on fame in the comments. Have you seen any of your “fifteen minutes” — and what has been the result?

If you liked the post, please share it using the buttons below.

————

This post contains an affiliate link.

The post Between Obscurity and Fame (The Writer’s Inner Life) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

September 29, 2016

How to Read a Boring Textbook (Letters to a Young Pastor)

Dear ______:

Dear ______:

I have to say I’m kind of envious of envious of you. It’s officially fall. We finally have some cooler temperatures. But in college or graduate school late September is full of gifts.

You are partway into a new semester, walking with newly familiar books in your backpack across campus toward the library, under the blazing yellows reds and oranges of the leaves. It is one of the magical times.

But, once you get to the library you have to read those books. And you are quite right when you say that my most recent letter helped only with a few of your assigned readings. (I put primary sources first because they’re the most fun, and the most important.)

The Problem of Textbooks

Your backpack is burdened with fat hardbacks with glossy pages, written by reasonably famous professors. These are the books that give you the grand sweep of each subject. We call them “textbooks.”

We also, usually, call them boring — boring as hell, to be theologically precise. (Can you imagine a worse eternity than reading an endless stream of introductory textbooks?)

Trouble is, you need what’s inside those hardcovers, and you know you need it.

That’s where you’ll find a lot of the stuff that comes up on the midterm and final exams. Lectures will highlight material to help you come to grips with the whole subject matter in those books. On your own.

Map vs GPS

You want to get the best of the book in the least amount of time. I have a plan for you.

It is like when you want to find your way in an unfamiliar city. You want a GPS. You need a map.

That may seem old-fashioned. When I moved to Pittsburgh, I went into a drugstore and asked the clerk for a map. Now admittedly, he was maybe 17 years old, but he looked at me quizzically and said

A map? I didn’t know people still used those.

He had to ask the manager.

Anyway you need a map, even if you have a GPS on your phone. The map shows you what the land looks like, the big picture, so the turn by turn instructions of the GPS will make sense.

Understand the map and you can zip through the turn-by-turn with ease.

How to Read a Boring Textbook

The problem with text books is that you have to make your own map. Think of yourself like like the early explorers: they knew where most of the continents were but they weren’t quite sure about all the coastlines.

So here is my five step map-making process.

1. Figure out what you should be looking for.

Look at the syllabus, and the title of the assigned chapter, and figure out what the topic is for the week.

Pause for a moment and ask yourself what questions this information leads to. What kinds of things are you likely to need to know?

This is like looking up the address before you start the car. You gotta know where you are going.

2. Find all the BIGGEST section headings.

Major section headings might be in all capital letters on a separate line, or all boldface, or both. These tell you how the author organized the whole shebang.

Different eras of a story?

Various theories on a problem?

Several concepts that make up an issue?

Map it: Take a sheet of paper and write out those big section headings proportionally. That is, if there are three big sections put one heading at the top of the page, one a third of the way down, and one two thirds of the way down.

That leaves you lots of room for notes as you create a one page summary map of the chapter.

3. Look to see what the subheadings look like.

Subheadings might be regular type or underlined on a separate line. These are the pieces of the puzzle, people making up stories, components making up a theory, or whatever.

Map it: Go back to your note sheet and put in the subheadings in their appropriate spaces.

4. Look to see if there are sub-subheadings.

Sub-subheadings might be bold letters in the first line of a paragraph or something else to indicate small parts making a whole. These are the smaller units, whether they are people or events or cases or whatever, that make up the major pieces of the puzzle.

Depending on the field you might find primary source evidence, data tables, important battles — it all depends on how the author organized the subject at hand.

Maybe map it: You might want to make a quick note about some of this, but mostly you just want to be aware of it in your mental map.

5. Read, and Fill in the map.

Read, and map the details: Now that you have a map to show what the territory looks like, it’s time to start the journey. Read the first subsection, and write a few brief notes on your sheet about its most important points. Keep doing this, section by section, to the end of the chapter.

A Tool to Keep at Hand

Now you have a useful roadmap to this week’s reading. You could probably make some spare change selling copies to your colleagues. Or you could just bring it to class, and study it before the midterm.

Happy reading!

Gary

————

If you enjoyed the post I hope you’ll share it — especially if you know any students!

The post How to Read a Boring Textbook (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

September 28, 2016

Why Was Christ Buried? (Heidelberg Catechism Q41)

From Question 26 to Question 58, the Heidelberg Catechism explains the Apostles’ Creed line by line.

From Question 26 to Question 58, the Heidelberg Catechism explains the Apostles’ Creed line by line.

(If you are new here, the Heidelberg Catechism is a widely-used and much-loved Reformed summary of biblical Christian teaching that I’ve been blogging on since its 450th anniversary in 2013.)

Some lines get explored across a few questions. Some take just one.

For instance, after discussing the trial crucifixion and death of Jesus, following the Creed the Catechism asks,

41 Q. Why was he “buried”?

The practical answer.

The simple answer comes to mind: Because he was dead. Of course he was buried. That’s what people do with dead bodies.

But, as you may have noticed, the Catechism always expects us to find a bit more than the simple and obvious answer. The authors wanted us to find something helpful. There should be, in every doctrine of the faith, something to benefit us.

At the very least, biblical teaching is there to teach us what we need to know to find faith in Christ, then to deepen our trust in the goodness Christ’s promises toward us. That will comfort us and equip us to live the lives to which we are called.

But is there a particularly helpful message in Christ’s burial? At first glance the Catechism’s tiny answer seems to admit this is a stretch:

A. His burial testifies

that he really died.

The hint of something more is in the word at the end of the first line: it “testifies” to something. That something is Christ’s death — which was already dealt with in the previous line of the Creed.

I think the writers of the Catechism were counting on us to ask some questions of our own at this point. If you were to ask someone who knows the history of Christian controversies why the Apostles’ Creed would add this extra emphasis to Christ’s death, here’s what you would find out.

The ancient answer.

Back in the earliest centuries there were groups on the fringes of Christianity, or groups within Christianity that articulated different views of who Jesus actually was.

Some were “gnostics,” religious groups that borrowed bits and pieces from Christianity and Judaism and Paganism and Philosophy. They initiated their members into their own secret “knowledge” or “gnosis.”

Some of these were influenced by Greek philosophy that sometimes taught that there was one perfect invisible God, far removed from our physical world.

Everything in our physical world changes — and they were convinced that God cannot change.

Therefore, they thought, the Christ who comes from God cannot be really human. He merely appeared or seemed human.

Groups who held these views came to be known as “Docetists” based on the Greek verb “dokeo” which means “I seem.”

Back when the Apostles’ Creed was written, there was this ancient problem of people trying to say Jesus wasn’t really human.

Why was Christ buried? Heidelberg’s answer

So Heidelberg’s answer to the question of why Jesus was buried is to strongly affirm the practical answer and the reason behind the ancient answer.

The situation is analogous to that of the inimitable Coroner of Munchkin Land, when the house landed on the wicked witch:

As Coroner, I must confirm, I thoroughly examined her

And she’s not only merely dead,

She’s really most sincerely dead.

It wasn’t enough to say Jesus was merely dead. That would never answer the human tendency toward a gnostic denial of Jesus’ humanity.

Jesus burial testifies that he was “really most sincerely dead.”

Which means he had been most sincerely alive, most sincerely human and subject to change just like you and me.

———–

If you enjoyed the post I hope you’ll share it using the buttons below!

The post Why Was Christ Buried? (Heidelberg Catechism Q41) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

September 26, 2016

Facing Futility (The Writer’s Inner Life)

CC by Jerzy Kociatkeiewicz-SA 2.0

CC by Jerzy Kociatkeiewicz-SA 2.0One of the struggles a writer faces (or anyone else with creative projects as part of their vocation) is the sense of futility.

It is one of those temptations that comes in a kind of inner voice. Why not be old fashioned and just call it one of our demons?

The Demon of Futility

It can come in the midst of a conversation with a stranger:

So you’re a writer! What have you written that I might have seen?

Even writers who have made best-seller lists will find that most strangers have never, ever, heard of them.

Or you sit down to write and there is:

Why bother? Nobody is going to care.

Publication can be years away. Even if you publish it yourself on your blog, getting it in front of people’s eyes is really tough.

(And by the way, if you are reading these words, please know that you rock my world — and even more so if you share the post with someone on Facebook…)

The demon of futility is uber-wily. It can remind you that you need to sit down and write something, just so it can slam you down by reminding you how useless it is.

If it reminds you that you should be writing when you are in the middle of some other necessary task (like, say, your day job) then you have the double-whammy: Guilt feelings for hours until you can sit down to write, and THEN the futility.

Antony the Great

I’ve been exploring the inner life of the writer in conversation with the monks of 4th century Egypt: the famous “Desert Fathers and Mothers,” and especially their hero and role model St. Antony the Great.

There is something important in common between a writer seeking solitude to squeeze something creative out of his soul and the thousands who hid away in huts and caves for a life of prayer. Both writers and monks fight their demons to be able to do something of deep value — possibly only to themselves.

Well, Antony faced demons very like those I’m talking about.

While we are sleeping they arouse us for prayers…

Well that sounds like an angel, not a demon. If your calling is prayer, then reminding you to wake up to pray or fast sounds pretty good.

But Antony says their motives are twisted. They keep the monk too tired to pray, too hungry to cope.

They do it all to turn the monks from their goal

…. so that they might bring the simple to despair, and declare the discipline useless, and make men sick of the solitary life as something burdensome and very oppressive…

I’ve never been to Egypt, but that is totally familiar.

Facing Futility

The monk and the writer are both pursuing goals most don’t share. The important thing in both forms of life is what Antony calls “the discipline.”

The monk or writer has to stay true to a set of practices — neglecting things many people think are vital to gain something many people think is useless.

The demon will say it is futile. The demon will turn your attention back to a more familiar path.

Antony’s advice? Two parts.

1. Ignore the voices. It drives them crazy.

But if anyone should pay no attention to them, they cry out and lament as though vanquished.

And again,

Therefore let us also pay them no heed, treating them as strangers to us, and let us not obey them, even in the event that they arouse us for prayer, or talk to us about fasting.

But just ignoring a voice like that is only a short term solution.

You always know you are holding that kind of inner critic at bay. Drop your guard and it will pounce.

So the second part of the advice is most important:

2. Remember your calling.

Rather, let us devote ourselves to our own purpose in the discipline…

Nobody else has to take up this task. Nobody else can do the creative work you are called to do.

It is your own purpose as a writer you have to remember. Think of the insight you wanted to share, the people you wanted to help or to entertain.

Put your focus on what you are called to, and remember why you started in the first place. The discipline will get you there.

————

I’d love to hear how you face messages of futility. Let me know in the comments.

And if you know other people battling futility while laboring at creative projects, I hope you’ll share the posts using the buttons below!

————

Quotations are from the Paulist Press edition of The Life of Antony. This post contains affiliate links.

The post Facing Futility (The Writer’s Inner Life) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

Facing Futility (The Writer’s Inner Life)

CC by Jerzy Kociatkeiewicz-SA 2.0

CC by Jerzy Kociatkeiewicz-SA 2.0One of the struggles a writer faces (or anyone else with creative projects as part of their vocation) is the sense of futility.

It is one of those temptations that comes in a kind of inner voice. Why not be old fashioned and just call it one of our demons?

The Demon of Futility

It can come in the midst of a conversation with a stranger:

So you’re a writer! What have you written that I might have seen?

Even writers who have made best-seller lists will find that most strangers have never, ever, heard of them.

Or you sit down to write and there is:

Why bother? Nobody is going to care.

Publication can be years away. Even if you publish it yourself on your blog, getting it in front of people’s eyes is really tough.

(And by the way, if you are reading these words, please know that you rock my world — and even more so if you share the post with someone on Facebook…)

The demon of futility is uber-wily. It can remind you that you need to sit down and write something, just so it can slam you down by reminding you how useless it is.

If it reminds you that you should be writing when you are in the middle of some other necessary task (like, say, your day job) then you have the double-whammy: Guilt feelings for hours until you sit down, and THEN the futility.

Antony the Great

I’ve been exploring the inner life of the writer in conversation with the monks of the the 4th century Egypt: the famous “Desert Fathers and Mothers,” and especially their hero and role model St. Antony the Great.

There is something important in common between a writer seeking solitude to squeeze something creative out of his soul and the thousands who hid away in huts and caves for the sake of a life of prayer. Both writers and monks fight their demons to be able to do something of deep value — possibly only to themselves.

Well Antony faced demons very like those I’m talking about.

While we are sleeping they arouse us for prayers…

Well that sounds like an angel, not a demon. If your calling is prayer, then reminding you to wake up to pray or fast sounds pretty good.

But Antony says their motives are twisted. They keep the monk too tired to pray, too hungry to cope.

They do it all to turn them from their goal

…. so that they might bring the simple to despair, and declare the discipline useless, and make men sick of the solitary life as something burdensome and very oppressive…

I’ve never been to Egypt, but that is totally familiar.

Facing Futility

The monk and the writer are both pursuing goals most don’t share. The important thing in the creative life is what Antony calls “the discipline.”

The monk or writer has to stay true to a set of practices — neglect things many people think are vital to gain something many people think is useless.

The demon will say it is futile. The demon will turn your attention back to a more familiar path.

Antony’s advice? Two parts.

1. Ignore the voices. It drives them crazy.

But if anyone should pay no attention to them, they cry out and lament as though vanquished.

And again,

Therefore let us also pay them no heed, treating them as strangers to us, and let us not obey them, even in the event that they arouse us for prayer, or talk to us about fasting.

But just ignoring a voice like that is only a short term solution.

You always know you are holding that kind of inner critic at bay. Drop your guard and it will pounce.

So the second part of the advice is most important:

2. Remember your calling.

Rather, let us devote ourselves to our own purpose in the discipline…

Nobody else has to take up this task. Nobody else can do the creative work you are called to do.

It is your own purpose as a writer you have to remember. Think of the insight you wanted to share, the people you wanted to help or to entertain.

Put your focus on what you are called to, and remember why you started in the first place. The discipline will get you there.

————

I’d love to hear how you face messages of futility. Let me know in the comments.

And if you know other people battling futility while laboring at creative projects, I hope you’ll share the posts using the buttons below!

————

Quotations are from the Paulist Press edition of The Life of Antony. This post contains affiliate links.

The post Facing Futility (The Writer’s Inner Life) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

September 22, 2016

Reading Dense Theological Texts (Letters to a Young Pastor)

CC BY Tom Murphy VII-SA 3.0

CC BY Tom Murphy VII-SA 3.0Dear ______:

Ah yes, your preaching class is requiring you to read something by St. John Chrysostom. I’m so glad — when you get to know a great preacher like Chrysostom, you may end up with a mentor for life. And you might not pick him up on your own, right?

But first you have to learn how to read him.

Fourth century rhetorical Greek translated into 19th century English is challenging. Reading dense theological texts is always challenging.

Learning to Read All Over Again

This gives me a chance to explain one of the key ways you need to learn to read in seminary.

Last time I wrote I suggested you needed to master at least three separate ways of reading to do well in your assignments and not get overwhelmed.

Strategy #1: For Dense Theological Texts

The first of those ways of reading is designed for dense theological texts. You most often need it in history classes when you are reading primary sources, especially from the early Church or the Middle Ages.

You were probably hoping for a way to speed read this stuff. You are out of luck. This is one of two forms of seminary reading that is probably actually slower than your ordinary pace.

There are three challenges with much theological writing — including Chrysostom’s preaching.

The Problem:

1. The material is more dense than you are used to. The writers discuss abstract concepts and build arguments rather than aiming for simplicity.

2. The style and structure is completely unfamiliar.

Great 4th century theologians essentially wrote in an oral style. They use rhetorical tools designed for your ear, not your eye. Some people do best to read them aloud and listen.

In the high middle ages, a Scholastic theologian like Thomas Aquinas wrote with a structure designed like a conversation — until you know which part actually expresses his own views you can be completely befuddled.

3. Often the conceptual world is very different from our own. Fail to notice that Anselm is thinking in terms of Feudalism and its system of justice and you won’t track with his argument.

These factors can conspire to leave you completely lost as your eyes keep plowing forward. You have to slow yourself down and make sure you grasp the flow of the work.

There is a way, however. And it is worth it.

The Solution:

Here is my simple and succinct plan to make sense of even very difficult theology from past eras. Follow these steps and you’ll be fine.

Before you open the book…

First ask some questions.

Figure out why the text was assigned. Find out in advance what to look for once you open the book and read. Do you have to write a paper on it, or spend an hour or two discussing it? Can you tell from the syllabus what key topics you ought to be looking for?

Find out in advance what is inside the covers. If you know what the text is going to be about you are less likely to get lost. Who wrote it? When? Where? Why? Skim through the introduction to the volume in which you find the text. There might be other references to help you, like Quasten’s Patrology, for material from the first five centuries, or volumes on one author, like Augustine Through the Ages.

All of this orients you and will make it easier for you to understand the text and gain what you need from it.

When you start reading…

Then, work through paragraph by paragraph (or numbered section by numbered section). Number the lines on a sheet of paper, and have your pen ready.

Read the first paragraph. Write a one-line summary on the first line of your paper. Don’t allow yourself to say any more than that.

Read your one-line summary of the first paragraph, then read the second paragraph and write a one line summary of that one.

Read your two one-line summaries, then read the third paragraph. Now write a one-line summary of that one.

Keep going like this all the way to the end.

You never summarize more than a paragraph.

Your summary is never longer than a line.

Your sheet of notes becomes a quick summary of the argument and key issues.

Reading through your notes each time reinforces your understanding of the whole, and helps you see where each part fits in. You never feel lost.

Then when class rolls around you show up for discussion with the text and your summary notes. You’ll be able to jump in easily, and you’ll sound really smart.

Blessings,

Gary

————

I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments — and if you liked the post, please share it using the buttons below!

The post Reading Dense Theological Texts (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.