Gary Neal Hansen's Blog, page 38

January 12, 2017

Are You Righteous? (Heidelberg Catechism Q59)

cc by UC Davis College of Engineering

cc by UC Davis College of EngineeringI sometimes run this experiment in theology classes — classes mostly of Reformed Protestants aiming to be ministers. You might expect they would be fluent in Reformed theology.

The experiment goes like this: I say,

Raise your hand if you are righteous.

How many hands do you think would be in the air?

Zippo.

And yet Question 59 of the Heidelberg Catechism — one of the doctrinal standards of the Reformed tradition — makes a terse little assertion:

… I am righteous …

Why don’t these Reformed Christians, budding Reformed ministers even, want to make the claim of their own Catechism?

Okay, I’m taking the tiny phrase out of its tiny context. But I did not change its meaning.

Our problem is the heavy load of baggage we bring to the issue.

If someone claims to be righteous we fill in all kinds of definitions.

We assume that being righteous comes from personal achievement of virtue, attained by personal effort.

We hear these words as a claim that someone has kept the 10 Commandments and all else that is required to be good perfectly.

We assume nobody can do that.

Our reaction is not unlike that of the high priest who heard Paul make that claim and ordered him to be slapped in the face (Acts 23:1-2).

We don’t want to get slapped in the face.

We don’t want to have to slap ourselves in the face.

This question comes just after the Heidelberg Catechism painstakingly explored every line — sometimes every word — of the Apostles’ Creed. The Creed is, in their view, the summary of biblical Christian faith. It is what any Christian should believe.

So then they ask this:

59 Q. What good does it do you, however, to believe all this?

That’s a familiar turn for the Catechism. They always work on the assumption that theology is good for you. If the Bible, and therefore the church, teaches it it must be there to help you in your journey toward God and new life.

Their answer?

A. In Christ I am righteous before God and heir to life everlasting.

I suspect that modern readers, even many Christian modern readers, politely say

Huh? These guys believe the Apostles’ Creed and so they say they are righteous?

It seems a tad absurd.

Are You righteous?

But to a 16th century Protestant, this was absolutely obvious.

In Genesis 15:6 Abraham trusted God, and God took that trust for righteousness. Paul emphasized the point in Romans 4:3.

The Apostles’ Creed tells us what we believe when we “believe God.” The good we get from that faith is that we too are righteous.

The catechism spends a few questions going more deeply into the topic, so tune back in for further explanation. But for now let it suffice to add in the little modifiers that the catechism puts around that claim.

In Christ I am righteous …

This flows from their earlier explanation of what saving faith is and does. It means to trust in Christ personally, and in God’s promise of grace embodied in Christ. That kind of trust draws us close, making us part of Christ’s own body: we are grafted into him like a branch of a grape vine or fruit tree.

What is the consequence?

On my own I’m guilty. But I’m not on my own any more.

Now I’m “in Christ.” And in Christ I am righteous.

There is another modifier too:

In Christ I am righteous before God.

The claim of righteousness is not about what you see in me.

And it is not a claim about my behavior.

It is certainly not a claim comparing myself to anyone else.

It’s a claim about my relationship with God: as I stand before God, God sees me as innocent. God sees me as part of the body of his Son Jesus.

So you can say it.

You ought to say it.

Maybe you should be discerning about who you should say it to.

But you are righteous.

When you’re down on yourself, feeling the pain of guilt and brokenness, but still listening to the promise of Christ know this: in Christ you really are righteous before God.

————

I’d love to send you a free copy of my new eBook on quirky and surprising saints. It’s called Role Models for Discipleship.

Click the button and I’ll send it along.

The post Are You Righteous? (Heidelberg Catechism Q59) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

Pastoral Timing and Faith-Sized Steps (Letters to a Young Pastor)

Dear ______:

Dear ______:

You asked a good question about my advice on being a pastor in dicey political times.

Doesn’t there come a time for being more direct? Don’t you need to speak out against such abominable sins as racism that leads to violence, xenophobia that stops people from loving their actual neighbors, and sexism that excuses abuse?

Yes, of course. My advice was really about the long game. The best time to start preaching the connections between the actions and words of Jesus to our own views on races, religions, nationalities, and genders is about ten years ago.

Once hatefulness toward other people, and whole categories of people, is socially acceptable in politics and society, it may be too late to help mere Christians get the point. This has happened in history. More than once, I’m sorry to say.

To my mind this points to two issues in pastoral life.

Faith-Sized Steps

First, once the time comes to speak directly on such issues, make sure you give the right message to the right people. Most of the time you are called to speak to your own congregation. Know them well and help them learn the way they should go.

Each person in your congregation is on their own step by step journey of discipleship.

Say you are talking to someone who is at point “A” or “G” or “M” on the ethical journey of living as a Christian in society.

Say you start preaching about how they need to be at point “X” or “Y” or “Z.”

Say you give the impression that all real Christians are at “X” or “Y” or “Z.”

Your listener is likely to hear your words as a political rant rather than helpful preaching.

What if you took another approach entirely?

Say you are talking to that same person who is at point “A” or “G” or “M” on the ethical journey of living as a Christian in society.

Say instead of “X” “Y” or “Z” you start preaching about how they need to take one small step to point “B” or “H” or “N.”

Say you give the impression that every Christian’s journey is made up of what my old pastor called “Faith-sized steps.”

Your listener is likely to hear your words as helpful preaching — and more likely to take a step in the right direction.

Pastoral Timing

The second issue that every pastor needs to work on is timing. There are lots of valuable biblical teachings that are only useful when they come up at the right time.

The “just in time” delivery model

Some issues need a “just in time” delivery system. A crisis arises, or a new turn of growth happens, and there is a new openness. That is, in life as in school, you have to be asking a question in order to have a place to fit the answer.

So you, as pastor, have to watch for the teachable moment when someone is either asking or open to input.

It happens a lot when people have their first child. Suddenly they actually want to know how to help someone (their own little cutie) grow into a life-giving faith: they are asking “evangelism” questions.

They find themselves open to the idea that having a life-giving faith of their own is crucial for this: they are asking “discipleship” questions.

And there you are meeting with them to talk about their child’s upcoming baptism. Just in time.

The “well-stocked warehouse” model

Other issues need more of a “well-stocked warehouse” model of delivery. Christians need to have the relevant teaching “in stock” well in advance, because once they face the issue they can’t hear.

Take, for example, biblical teaching on suffering. The Bible teaches in various places that suffering can be really helpful in making you grow — that suffering can, paradoxically, lead to joy.

Say the worst happens in the life of a family in your church: a child dies.

What happens if you show up and say “Hey, remember, the Bible tells us suffering leads to joy! You are gonna grow so much from this!”?

They aren’t going to be open to that message. They may never be open to your so-called biblical teaching ever again.

But what happens if in your ordinary preaching and teaching, years in advance, you explored the ways that the Bible talks about suffering, growth and joy.

You didn’t do it in a foolish easy-peasy way. You took suffering seriously. But you were a wise pastor and you helped the congregation consider ways they had seen growth in their own lives through life’s tough patches.

Then, when the worst happens, what do you do?

You cry with them. You be the presence of Christ to them.

If they ask what the Bible says about suffering, and if they aren’t supposed to be joyful, stick for now to “Weep with those who weep.” (Romans 12:15 NRSV)

You already stocked the warehouse. They’ll have that resource when they need it, if they need it.

Discernment

So the hard work of pastoring is discernment.

You have to know the person you are talking to.

You have to discern what the next single step of faith might be.

You have to discern which questions they are asking or open to.

You have to discern which topics need to be taught far away from a time of crisis.

And I’ll be rooting for you all along the way.

Blessings,

Gary

————

I’d love to send you a free copy of my new eBook on quirky and surprising saints. It’s called Role Models for Discipleship.

Click the button and I’ll send it along.

————

If you liked the post please share it using the buttons below…

The post Pastoral Timing and Faith-Sized Steps (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

January 6, 2017

How Comforting Is Everlasting Life? (Heidelberg Catechism, Q58)

So finally the Heidelberg Catechism reaches the end of the Apostles’ Creed. (That’s “finally” if you’ve been with me since 2013 when I started blogging on the Catechism, including this section.)

So finally the Heidelberg Catechism reaches the end of the Apostles’ Creed. (That’s “finally” if you’ve been with me since 2013 when I started blogging on the Catechism, including this section.)

They’ve been at it line by line, sometimes word by word, since question 26. Now it is Question 58, and they address the concluding phrase

…And the life everlasting.

In the Europe of 1563 they didn’t bother to define it. Almost everybody was at least nominally Christian. They assumed they knew what “everlasting life” meant.

Today people might reasonably wonder. Look around and you’ll find multiple opinions.

Some have a standard Christian-ish assumptions, no matter how tenuous their connections to the Bible. Think stereotypes: playing harps, lounging on clouds, turning into angels.

A few pay big bucks to have their bodies kept in the deep freeze so they can be thawed out and revived when medicine has made necessary advances.

And many envision a purely secular eternity: they hope their lives makes a big enough splash that someone, anyone, will remember them. Having their own Wikipedia page would be hitting the big time.

The question that Heidelberg does ask is distinctive. It points out their assumptions about the whole of Christian theology:

58 Q. How does the article concerning “life everlasting”

comfort you?

Christian teaching, all of it and every part, is supposed to be deeply helpful, giving us confidence in God’s care as we live out our days as people of faith.

But when it comes to everlasting life, as I said, things have changed since the Reformation.

Let’s admit that some, probably even a subset of Christians, do not find the idea of living forever comforting at all.

They may have found their life miserable — they just want it to end.

They may have lived out their most important hopes and dreams — they are simply done.

They may have a totally atheistic and materialistic worldview, and expect nothing but — well, nothing.

But most Christians do find comfort in the promise of everlasting life. Here’s how Heidelberg explains it:

A. Even as I already

now experience in my heart

the beginning of eternal joy,

so after this life

I will have perfect blessedness

such as no eye has seen,

no ear has heard,

no human heart has ever imagined:

a blessedness in which to praise God forever.

It is an issue of the “now” and the “not yet” as some like to say. The “now” is real — the kingdom of heaven has drawn near, and Christ is in our midsts. But there is more to come — just “not yet.”

How is Everlasting Life Comforting?

I suspect that this rings perfectly true for many Christians. We have tasted joy in Christ, in the midst of earthly struggles. It is wonderful to think of that joy in fullness, undiluted, unending.

The weakness of Heidelberg’s response is that it comes close to a quiet capitulation to the Western ideals of individualism and personal fulfillment. It is about me, my joy, my blessedness, even if it specifically directed to continuous praise of God.

My hope in eternal life expands when I listen to Gregory of Nyssa, the great four century theologian who shaped the East.

In his great book The Life of Moses, Gregory takes the Exodus narrative as a model for our spiritual growth.

Moses climbs up the mountain, closer to God. It led to genuine transformation — he glowed in the dark afterward.

To Gregory, our life here on earth is about growing intimacy with God so that God’s good work is done within us. The tarnished image of God is restored, and we shine with God’s glory. We actually become more like God.

But for Gregory, this process is simply not finished in this life. It continues to be the business of heaven. Like at the end of C.S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia, eternal life in heaven is not static. The children and Narnians run up to glory crying

Further up! Further in!

It is constant movement toward God, constant transformation to be more like God.

And since God is infinite, and we are finite, there will always be room for further transformation.

Further indeed. Further up! Further in! That’s what comforts me in life everlasting.

————

I’d love to hear from you in the comments. How do you (or don’t you) find the promise of life everlasting to be a comfort?

————

This post contains affiliate links.

The post How Comforting Is Everlasting Life? (Heidelberg Catechism, Q58) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

December 30, 2016

Celebrating the Birth of Jesus with His Mother

cc by Paul J Everett

cc by Paul J EverettDuring Advent I went one Wednesday night to St. George Antiochian Orthodox Cathedral in Pittsburgh. I was surprised to hear a service that was new to me: Not the ordinary Vespers, but the “Advent Paraklesis.”

As in so much of Orthodox worship, the hymns carry a huge freight of theology. As always there is much reveling in the paradoxes of salvation, especially the mystery of the Second Person of the Trinity who made heaven and earth allowing himself to dwell in the tiny space of Mary’s womb.

But in this particular service I was struck by one subset of hymns. They took a close and imaginative look at the thoughts of Mary, Jesus’ mother, upon his birth.

How many Christmas pageants have I seen in which Mary brings forth the child who will save humanity, but is given not a single line of reflection on the event?

The little girl in a costume made from a table cloth just sits in the tableau, silent.

It’s worth exploring the idea of how Mary celebrated the birth of Jesus. I’ve always thought that mothers should be the ones who to be thrown parties on their children’s birthdays. They did all the hard work.

Celebrating the Birth of Jesus with His Mother

So let’s give a listen to the centuries-old imaginings of what Mary might have been thinking, and praying, and singing as she snuggled her newborn during the 12 Days of Christmas. These are scattered amid other hymns in the last half of the service.

What is this great and strange wonder?

How do I uphold thee who upholds all the world by thy Word?

O my Son who art without beginning, thy birth is beyond all speech.

The heavenly throne is consumed in flames as it holds thee;

how is it, then, that I carry thee, my Son?

Thou dost bear the likeness of thy Father, O my Son.

How then hast thou become poor and taken upon thyself the likeness of a servant?

How shall I lay thee in a manger of beasts without reason, who dost deliver all men from unreason?

I sing the praises of thy compassion.

O sweetest Child, how shall I feed thee who givest food to all?

How shall I hold thee who holdest all things in thy power?

How shall I wrap thee in swaddling clothes, who dost wrap the whole world in clouds?

May these days of Christmas be full of reflection, praise, and prayer for you too. I pray God may give you richest blessings, and signs of the new life Christ was born to bring.

(If you want to hear some Advent and Christmas music in the Byzantine tradition, check out this CD by the choir of St. George Cathedral. Great stuff…)

————

I’d love to send you a free copy of my new eBook on quirky and surprising saints. It’s called Role Models for Discipleship.

Click the button and I’ll send it along.

————

This post contains an affiliate link.

The post Celebrating the Birth of Jesus with His Mother appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

December 29, 2016

Being a Pastor in Dicey Political Times (Letters to a Young Pastor)

John Calvin by Holbein

John Calvin by HolbeinDear ______:

Ah yes, the political question. How do you be a pastor to a congregation in dicey political times?

You are wise to consider this now, while you are in seminary. But don’t be surprised if, down the road, the dynamics life with an actual congregation prompt you to deal with it differently than you plan to.

So imagine yourself as a pastor in a hypothetical election year:

To half your congregation one candidate looks like the only way to make the country great.

To half your congregation, one candidate looks like a fascist.

And both halves are talking about the same candidate.

Speaking in public about the election would understandably feel like stepping into a mine field.

Wisdom probably comes from knowing who you are. The “Who?” of pastoring has a variety of biblical and traditional answers.

Priest

In many traditions (Orthodox, Catholic, Anglican, and sometimes Lutheran) you would be likely to view yourself as a priest. If you don’t think of “priest” as a New Testament ministry category, Martin Luther would tell you that you are joined to Christ, our High Priest, in Baptism, and so you share his priestly ministry.

And Luther, at least, thought of a priest as a kind of mediator: speaking to God on behalf of the people in prayer, and speaking to the people on behalf of God.

That responsibility to speak on behalf of God can mean many different things. For Luther it meant giving the message of God’s gracious forgiveness in Christ. For others? Another role can come into play…

Prophet

Some think of speaking for God in terms of the biblical prophets. They take Amos or Jeremiah as their ministry model, especially in preaching. They aim to “speak truth to power.” (Though most Sunday mornings they might be described as speaking about power to the choir.)

But prophetically telling your congregation who to vote for might lead people to feel that you’ve overstepped your bounds (and I suspect the IRS might think so too).

It isn’t that they don’t think their faith has to do with politics. Rather they think you are there to help them with the faith part, and they can apply it to politics for themselves.

Shepherd

Another option is “shepherd.” These days some dislike the “shepherd” metaphor for ministry. Your congregation won’t find it flattering if they find you think of them as “sheep.” But the word “pastor” itself points to shepherding.

So let’s work with it for a minute. It may be a bit old-fashioned, but it is biblical: Jesus described himself as the Good Shepherd and, as with his priesthood, we share his shepherding ministry.

If you are going to be a good shepherd you’ll need to look very carefully at your flock. You need to know them personally — by name, as Jesus said. And you will need to aim to provide them what they need, and you’ll protect them from harm. You’ll try to help them flourish.

To do that, especially in relation to political life, I recommend you consider a fourth biblical image of the pastor.

Teacher

In my denomination we recently changed the official title of our pastors. No longer “Ministers of Word and Sacrament,” we are now “Teaching Elders.”

That goes to the heart of what some of our best leaders did back in the Reformation. John Calvin thought of the Church as a school from which we always learned but never graduated.

John Chrysostom in Exile

John Chrysostom in ExileIt reflects much of the best of ministry in other traditions as well. John Chrysostom’s fourth century sermons were such remarkably useful expositions of Scripture that they have been published as Bible commentaries.

He taught them — and he really did speak truth to power, when power was actually listening, even though it led to exile.

As a teacher, you give the people nourishment from Scripture; you help them draw refreshment from the deep well of Christian teaching, and the living water of Christ himself. Then you hope they’ll be strong and wise enough to make good decisions in politics and throughout life.

A good teacher does not dictate the choices the students make outside the classroom. The good teacher informs, and equips, and nurtures skills so that the students make good choices. You help them learn the shape of the faith, and the way of Christ-like wisdom — before they face a choice or a crisis.

Being a Pastor in Dicey Political Times

You may not be able to convince someone that their favored candidate is dangerous. You might not be wise to try to do so explicitly.

But you have opportunities to teach — in the pulpit, in small groups, and one-on-one. Take the opportunities. Plan for them.

Build your members up with a solid knowledge of the Christian faith so that they will cast their votes and use their voices to support causes Jesus would love.

Show how Jesus treated women with respect, letting Mary sit and learn with the Apostles as a theologian, and treating the Woman at the Well with kindness and sending her as an evangelist — and how we should too.

Show how Jesus treated people with disabilities with respect, hearing the cries of the blind, the lepers, the paralyzed, and doing what he could to help them — and how we should too.

You can preach on how Jesus loved and served people of other ethnic and religious backgrounds. That woman at the well was a Samaritan, and so was the role model of ethical life in one of his most famous parables. He healed the daughter of the Roman Centurion and the son of a Syro-Phonecian woman. Show how he honored strangers — and how we should too.

Show how he broke down walls of division and hostility between Jew and Samaritan, Jew and Greek, male and female, slave and free — and how we should too.

You can preach on how Jesus actually fed the hungry rather than sending them off to fend for themselves as his misguided disciples recommended — and how we should too.

Surely, you can tell yourself, people who are well taught in the Christian faith would not support a candidate who would denigrate women, mock the disabled, or pledge to ban people of other nations and religions.

But if they do, then love them. Continue to teach them. You are their shepherd. That’s practicing what you preach.

Blessings,

Gary

————

I’d love to send you a free copy of my new eBook on quirky and surprising saints. It’s called Role Models for Discipleship.

Click the button and I’ll send it along.

The post Being a Pastor in Dicey Political Times (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

December 21, 2016

Lectio Divina on the Song of Simeon

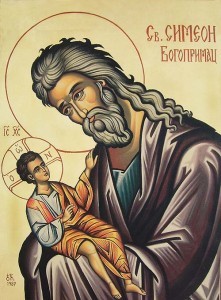

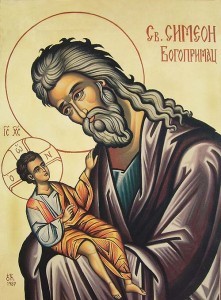

St Simeon the God Receiver on WhatDoYouDoDear?

St Simeon the God Receiver on WhatDoYouDoDear?St Simeon the God Receiver

What does it mean to receive God? What does it mean to “see” your salvation?

Those are questions that come to mind when you pray your way through “The Song of Simeon,” the old man to whom Mary introduced the Baby Jesus in the Temple.

The Orthodox call him “St. Simeon the God Receiver” — God promised him that he would see the savior, and there he was, holding God Incarnate in his arms.

Classical Lectio Divina

If you are a regular here, you may know I’m teaching an online Advent class on classical lectio divina.

I’m teaching the classical version, as practiced in the Middle Ages. It’s not a superficial reaction to a text after reading it a couple times. Back in the day lectio divina was a full-on mind/heart/spirit engagement with the Bible and a journey to the presence of God.

It is a four step journey:

“Reading,” which is shorthand for serious study.

“Meditating,” which means quietly repeating and chewing on the text in your mind and heart.

“Praying,” which isn’t separate from the Bible but grows out of what you have been discovering about yourself in the text.

“Contemplating,” which is not emptying your mind but looking toward the God you just prayed to and — waiting.

In the class this week we are practicing lectio divina on the “Song of Simeon,”

Contemplation

All this week I have found the contemplation stage deeply comforting. It is easy to drift off, yes, but it is always good to return to gazing toward God.

And waiting, watching, is something both appropriate to the season and inevitable in life. Think of St Simeon and St Anna in Luke 2, waiting all those years in the temple. And at last they saw their salvation — it was a Person.

Contemplation allows me to give in to the waiting. I gaze into the face of the One for whom I wait.

And it helps to have an icon, a holy image of the scene from which I am contemplating God in lectio divina. It brings me back to waiting and watching.

If icons trouble your Protestant sensibilities, rest assured that nobody worships them. One looks through them, as through a window, to better see the One we do worship.

————

I’d love to send you a free copy of my new eBook on quirky and surprising saints. It’s called Role Models for Discipleship.

Click the button and I’ll send it along.

The post Lectio Divina on the Song of Simeon appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

December 19, 2016

On Memory and Creative Work (The Writer’s Inner Life)

cc by Roman San 2.0

cc by Roman San 2.0These are bitter cold days in Pittsburgh where I live. At this latitude these are also short days; among the shortest of the year, with either gray gloom or low glaring winter sun.

It can be hard to simply be. Add in the busyness of the ramp-up to Christmas and it can be very hard to write.

But what really makes it hard to focus on writing? Memory.

Actually that is true in any season.

Memory and Creative Work

The Desert Fathers and Mothers had a few things to say about memory. That’s what they had: in the life of the solitary monk, there was little new stuff pressing in.

They had to find helpful ways to deal with the old, the stew of past experience and past knowledge. Living well with their memories would make the difference between failure and progress.

That’s not only for monks. It is true of anyone who does solitary work–like writing.

I find different, and highly complementary perspectives from Abba Macarius and Abba Evagrius.

Memory as Problem

Abba Macarius lived as a hermit at a high elevation in the Egyptian desert — maybe up mountainside in a cave, or on a plateau. Most of the monks lived in the plain down below.

There was a road from the elevation to the plain. Macarius saw Satan passing by. The enemy was on his way down to the lower settlements. So Macarius called out:

‘Hey mister, where are you off to?’

He said ‘I’m going to stir up the memories of the monks.’ (Visions 9, p. 188)

Their memories. All the devil needed to do was to stir the pot and there would be trouble in plenty.

In this story he brings all kinds of good food along to help the process — get their attention on the tastes of home and childhood. Soon they won’t be thinking of prayer and salvation.

In other stories monks are plagued by memories of sexy pictures they saw long ago.

You and I have our own stew of memories to distract us.

Give the pot a stir and up comes a wound from rejection.

Stir it again and up comes someone we harmed, to our own shame.

Stir again, and we find our aspirations not fulfilled — and envy at those who have gone farther.

One more stir and we find our achievements and honors — and pride at how special we are.

Just about anything in the realm of temptation, or sin, of vice, or even virtue, is capable of distracting us, taking our attention away from today’s actual calling.

That’s memory as problem. True enough — but not the whole truth.

Memory as Solution

Abba Evagrius (master of the spiritual life, though not always so hot as a doctrinal theologian) saw that memory could also be the solution.

Evagrius advises the monk to actively use his or her memory. Choose to remember, to call to mind, the big picture of our life. Remember the salvation God promises. Remember the warnings about the consequences of sin.

Heaven. Hell. The road to each destination. That kind of thing.

Remember all this. Weep and lament for the judgment of sinners, keep alert to the grief they suffer. … Rejoice and exult at the good laid up for the righteous. Aim at enjoying the one and being far from the other. Do not forget this whether you are in your cell or outside it. Keep these memories in your mind and so cast out of it the sordid thoughts that harm you. (Compunction 3, p. 13)

Evagrius’ insight is that we really don’t multitask. Our attention has a capacity of one thing at a time.

Left to the enemy, we get distractions bubbling up in front of us. But if we use the memory God gave us we can bring what is true and helpful before our minds.

Bring to mind what we remember to be true: Jesus. His grace and mercy toward us. His promise.

Then, more firmly fixed on the Rock, we turn our attention to our calling.

The prayers we are called to offer today.

The words we are called to write today.

The art we are called to create today.

The people we are called to love today.

————

I’d love to send you a free copy of my new eBook on quirky and surprising saints. It’s called Role Models for Discipleship.

Click the button and I’ll send it along.

————

This post contains an affiliate link.

The post On Memory and Creative Work (The Writer’s Inner Life) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

December 14, 2016

An Open Letter to the Electors of the Electoral College

Below you will find an open letter to the Electors of the United States Electoral College for 2016. Yesterday I sent a very slightly different version to each of the electors for my home state of Pennsylvania.

Below you will find an open letter to the Electors of the United States Electoral College for 2016. Yesterday I sent a very slightly different version to each of the electors for my home state of Pennsylvania.

It may appear off of my usual historical and theological topics, but it is not.

Theologically, this is an action I take as a Christian citizen, seeking to help righteousness prevail and justice be done in my country.

And I know I am able to do this because I know a bit of history — the Constitution, through its Bill of Rights, guarantees my rights of free speech and freedom of religion.

I sent it, and I post it here, because the risks in our country and our world are both great and grave.

I don’t want to have to tell my children that I stood by in silence.

An Open Letter to the Electors

Dear ______:

I am writing to you in your capacity as an elector for your state.

First of all, thank you for your good service to your party in a challenging election season.

Second, I urge you to fulfill your responsibility for the defense of the Constitution by casting your vote against Donald Trump. Please do so even if in your state this is an act of civil disobedience.

When the Electoral College was created, the purpose was to bring wise action if, through whatever chain of events, someone was elected who turned out to be grossly unqualified or otherwise dangerous to the Constitution.

This situation has come to pass. The oath of office for the President is, almost in its entirety, to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” Donald Trump, in his campaign, repeatedly and emphatically stated his intention to work against the explicit contents of the Constitution.

In particular please note his policies that stand against the free exercise of religion, and his threats against the free press, both of which are rights guaranteed by the Constitution.

It is also important to note that he boasted on tape of having committed sexual assault, and after he did so a significant number of women came forward to say they had been victims of his mistreatment in this way. Please do not put in office someone with whom you would not allow your daughter to be alone.

His campaign, and now his proposed appointments, have appealed to people’s basest instincts, garnering the support of groups with racist agendas. Surely you have seen and heard that threats and crimes of racial and religious hatred have gone up since his election.

Please, in the name of God, I beg you to do your duty as an elector by keeping Donald Trump from taking office.

Sincerely yours,

Gary Neal Hansen

The post An Open Letter to the Electors of the Electoral College appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

December 12, 2016

Setting Sail Into Writing Fiction (The Writer’s Inner Life)

cc by OakleyOriginals 2.0

cc by OakleyOriginals 2.0I’ve not posted often in the past month. I spent the time writing the first draft of a novel.

It was NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) — when several hundred thousand wannabe novelists around the world each set the goal of producing a 50,000 word first draft in the month of November.

I’m happy to say that I met my goal. It was really fun, even if it was exhausting. I learned a lot about myself as a writer. And I learned some entry-level lessons about writing fiction.

I do know that I’m only at the beginning of learning to write fiction. One of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers provides a cautionary tale:

Another brother spoke with the same Theodore, and he began to talk about matters of which he had no experience. Theodore said to him, ‘You’ve not yet found a ship to sail in, nor put your luggage aboard, nor put out to sea, and you’re already acting as if you were in the city which you mean to reach. If you make some attempt to do the things you are discussing, then you can talk about them with understanding.’

I wanted to make some progress as a fiction writer by writing, rather than pretending I’ve become an expert by reading about it. If I’ve never written a novel, what do I have to say to a novelist?

I’ve always found the idea of writing fiction tantalizing. I’ve written a lot of non-fiction in a variety of contexts. But I’ve only taken small forays into writing out stories of my own invention.

Until now. Writing fiction is something I’m convinced is worth doing for me. It is worth doing whether I ever even try to publish what I write or not. It is hard work, but strangely life-giving.

I had a number of goals for the project:

1. Productivity

I wanted to grow in the discipline of writing more productively. 50,000 words in 30 days would be a higher daily word count than I’ve ever reached before. That’s 1,667 words per day if you write every day. I take Sunday as a day of rest — and between school closures, international travel, and Thanksgiving there were other days I could not write. A month of reaching 2000 words every day I wrote would “win” NaNoWriMo. And it might leave me well on the way to a habit. That kind of productivity will help with every kind of writing.

2. Story telling

I wanted to become a better story teller. I know my non-fiction writing will be stronger if I tell more stories and tell them better. Too much exposition and description and telling of things makes for dull reading. Stories bring readers in and carry them along. What better way to hone the skill than to practice writing fiction? One long story made up of a whole lot of shorter stories gave me a month to work on it.

3. Marking a change

I’m in a season of vocational change. I had seventeen years as a seminary professor. Now I’m a professor gone rogue. I’m learning to work entrepreneurially at the parts of my vocation I love most. That is fun, but change is hard. I thought taking a full month to do something completely new would be a great way of marking the change of seasons within myself.

4. Breaking new ground

I thought the whole process would bring growth — growth in skills but also growth in health. How right I was. There was something healing about the whole thing. I took a daily journey through the imagined struggles of people in a made up situation. Somehow this shone light into some sad darkened corners, even though the novel had nothing explicit to do with the life I’ve recently left behind.

Learning to write by writing fiction

So to those of you who prayed for me during NaNoWriMo, many thanks.

In Abba Theodore’s terms, I’ve only found a ship. I know I have not yet arrived at the city. But the journey so far has been great. I look forward to the many miles still to come.

————

————

This post contains an affiliate link.

The post Setting Sail Into Writing Fiction (The Writer’s Inner Life) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

December 8, 2016

How to Take Notes While You Read (Letters to a Young Pastor)

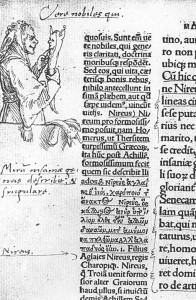

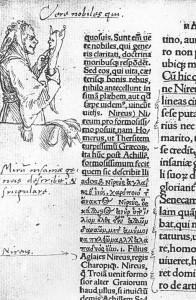

Hans Holbein the Younger, illustration for Erasmus’ In Praise of Folly

Hans Holbein the Younger, illustration for Erasmus’ In Praise of FollyDear ______:

As Sherlock would say, excellent observation, my dear Watson: My strategies for reading the texts assigned to you in your seminary classes are not always enough to make sure you learn what you need to learn.

To learn from your reading you need to do more than let your eyes pass over the words.

I think a lot of students open their book and hear the the PA announcement at the start of the Indy 500:

Ladies and Gentlemen, start your engines!

They hit the gas and zoom forward, never stopping until they reach the end — whether their minds are processing the meaning or not.

Yes, you need to read differently in the case of primary sources and other dense texts, introductory textbooks, and current scholarly monographs. But with all these you need to find ways to keep your mind actively engaged.

For one thing you need to stay awake, in conversation with the author.

And for another you need to be aware of what you have really digested and what will need another look later.

Take Notes While You Read

I have three approaches to suggest. Try them out. Adapt them. Use whatever works for you. You probably wish I’d suggested this in September. Oh well. There is another semester coming. And it is hard to apply advice until you know you face the problem.

Method One: Clean and Simple

My good friend Joe Small, with whom I taught a cohort of Doctor of Ministry students, recommends a simple kind of symbol system to make notes on the go. As you read, in the margins you leave the following trail of breadcrumbs. (Only, of course, if you own the book. Don’t do this in the library copy.)

“!” indicates something that strikes you as surprising or insightful.

“X” indicates a point with which you disagree.

“?” indicates something you don’t understand, find confusing, or otherwise needs another look.

All these marks are useful. They give you some places to study further before class.

And they make great things to bring up as initial observations or questions in seminar discussions.

Method Two: Conversational and Engaged

My own strategy for marginal notes is a little more expansive.

On the one hand I learn best from a book if I think of myself in conversation with the author. So I’ll write out a sentence or a few phrases of where a passage leads me.

Sometimes I voice my affirmation or disagreement.

Sometimes I cross reference another work.

Sometimes I ask the writer a question.

Sometimes I riff on an expansion of an idea.

Very occasionally I’ll draw a picture — though not as well as Holbein.

On the other hand I’m often trying to track a key word or idea. I’ll write that word in the margin whenever it appears so I can track back to all the references.

On the other hand (what? three hands?) I’m often looking for structure. Many authors, even influential figures like Augustine, Barth, and Calvin (the ABCs of theology?) don’t make their outline or structure clear enough to be helpful.

I mark out beginnings of sections.

I underline the phrases that telegraph subheadings (“first… second… third…” or “one the one hand… on the other hand” etc.)

Then I can take in the big picture more easily.

And hey, if you become really famous somebody may write a dissertation on your marginalia some day.

Method Three: Keeping a Record

If you want to really think ahead and learn in depth, follow the model I heard about only too late. One friend in grad school made one page of notes on every book and article he read.

Then he organized these notes so that he could find them again — whether by person or topic I don’t know. You’ll have to think about that for yourself.

If you need to study the topic, or write a paper on it, those notes will be solid gold.

But even if you never look at them again, just writing them will cause you to learn and remember the book’s contents much better than if you just read with your eyes, and stick the book back on the shelf.

Blessings,

Gary

————

I’d love to send you a free copy of my new eBook on quirky and surprising saints. It’s called Role Models for Discipleship.

Click the button and I’ll send it along.

The post How to Take Notes While You Read (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.