Gary Neal Hansen's Blog, page 34

April 16, 2018

Monday Meditation — RCL Year B, 4th Sunday of Easter, John 10:11-18

CC by Walters Art Museum-SA 3.0

CC by Walters Art Museum-SA 3.0“I am the good shepherd,” says Jesus.

Among the “I Am” sayings in John, “I am the Good Shepherd” is particularly beloved. There is tenderness and love in it that appeals to both children and adults.

One of the earliest images in Christian art is that of a shepherd, gently carrying a sheep across his shoulders.

John 10:11-18

Like in many of Jesus’ speeches, in John 10:11-18 Jesus bounces between emphases, rather than laying out a logical progression. This portion of the larger passage one can see several:

Jesus is not like some hired hand who doesn’t really care about the sheep. They are his and he loves them.

There really are dangers and enemies for Jesus’ followers, like wolves that threaten sheep.

Jesus really knows us, just as the Father really knows Jesus — a sort of pre-echo of the intimacy in High Priestly Prayer of John 17.

The sheep currently in the fold are not Jesus’ only sheep. Surely they thought of this when the Risen Christ called them to be his witnesses to the ends of the earth (Acts 1:8).

The Good Shepherd Lays Down His Life

But there is one more emphasis that seems most important, if only because Jesus states it multiple tims: the good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep.

Laying down his life is the opening, the very nature of the Good Shepherd.

Laying down his life is in the middle, the answer to the problems of wolves who attack, and frightened hirelings who run away.

Laying down his life is the mysterious promise that makes possible his mission to the sheep outside the current sheepfold.

And laying down his life is not the end — it is for the sake of taking it up again, which surely accounts for this text appearing in Easter season.

The promise of Jesus to gather in other sheep and make them one united flock was, for the Reformed Christians of the sixteenth century, what we would call their sense of mission. They prayed, often, both for help to love their neighbors and for Christ to gather in the lost sheep.

Of His Own Free Will

I am struck, however, by how emphatic Jesus is here about his own choice in laying down his life. Much ink has been spilled in recent decades about apparent horrors in God the Father sending his only-begotten Son to his death. It sometimes gets portrayed as divine child abuse.

By contrast, here Jesus is quite clear: nobody forced him.

Jesus laid down his own life out of love, and that love is pleasing to his father. Or as another apostle put it, Jesus “for the sake of the joy that was set before him endured the cross,” (Hebrews 12:2).

The Orthodox, by the way, really hammer that point home. In every Liturgy the priest proclaims in prayer “…on the night in which He was delivered up, or rather when He delivered Himself up for the life of the world, He took bread in His holy, pure, and blameless hands…” The sentiment is echoed in other Orthodox hymns and prayers, always declaring the joyful self-giving of the shepherd who willingly lays down his life for the sheep.

I wonder what would make me feel more like Jesus very own sheep?

I wonder what wolves might be lurking in my world and my life?

I wonder who might be Jesus’ own sheep but aren’t yet part of his sheepfold?

I wonder if it makes a difference that Jesus freely and willingly laid down his life for us?

++++++++++++

To get my Monday Meditations and other posts and news in your own personal inbox, sign up for my weekly(ish) newsletter using the orange button in the black box below…

The post Monday Meditation — RCL Year B, 4th Sunday of Easter, John 10:11-18 appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

April 9, 2018

Monday Meditation — RCL Year B, 3rd Sunday of Easter, Luke 24:36b–48

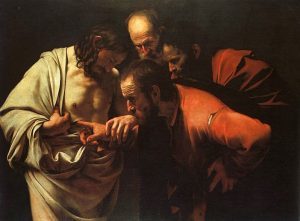

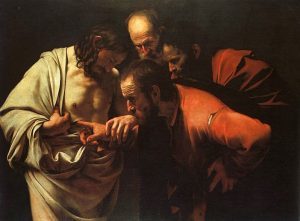

Caravaggio: The Incredulity of Thomas (public domain)

Caravaggio: The Incredulity of Thomas (public domain)The similarities between the four evangelists when recounting the the resurrection encounters can make it hard to keep the stories straight. Next Sunday’s passage of Luke (Luke 24:36b–48) bears echoes of the pair of encounters in John, first without Thomas and then with him.

Luke 24:36b–48

Once I get my bearings, I note four things, all important to my living of the faith.

First is the ending: much like in Matthew 28 and Acts 1, the risen Christ commissions his followers as witnesses. I take this as good news, since a “witness” is never called upon to do anything but tell honestly what he or she has seen and known. That’s much more manageable than being in charge of Christ’s own work and mission.

Second, to my enormous comfort, the disciples don’t actually get it. They were startled, terrified, had doubts, disbelieved, and mistook their beloved Jesus for a ghost. Oh yes, they also felt a bit of joy in verse 41. I go through most of life a bit baffled as to what God is up to, so I’m glad to know this has important precedent — even apostolic authority.

Third, Jesus went well out of his way to comfort and reassure them. He started with the message familiar from so many startling angelic visitations: “Peace be with you!” When that wasn’t quite sufficient, Jesus let them see his wounds and touch him. And when they still weren’t convinced, Jesus had them give him a snack, all so they would know he was real.

The fourth thing, I am convinced, is the most significant: Jesus did a miracle. It is easy to miss it, but it is a very big deal. It is in verse 45:

Then he opened their minds to understand the scriptures.

It is easier to notice that he spent some time teaching them, showing how the Old Testament pointed out that the Messiah was to the suffer and then rise from death—which is to be their message as witnesses.

The miracle was that he enabled them to understand this teaching.

This is the last, resurrection appearance in Luke. The miracle answers the big problem building up through those appearances.

At the tomb, the myrrh-bearing women did not see Jesus himself. The angels benevolently roll their eyes when the women don’t remember that Jesus said he must die and rise.

The male disciples didn’t get it either, deciding the women were speaking nonsense.

Then on the road to Emmaus, two disciples were bummed out about Jesus’ death and baffled by the women’s testimony. Jesus himself is there, but they don’t recognize him, even as he teaches them of the biblical testimony to his life and work.

Lest we look down on them, though, Luke tells us that they were “kept from recognizing” Jesus (v. 14). It was only when “their eyes were opened” (v. 31) that they knew who he was.

So it seems to me that in 34-48 Luke shows Jesus doing what was needed for the whole band of followers to understand the very gospel itself — Jesus really is the anointed one who (very biblically) suffered and rose for our salvation.

This is the essential miracle of faith.

I wonder…

I wonder if I need this miracle again today?

I wonder if there are places where my mind is closed, my heart hardened, my eyes kept from recognizing Jesus?

I wonder if I should pray for this same miracle for those around me who seem to struggle to believe, or who lack faith faith entirely?

++++++++++++

I’d love to send you new posts by email. You’ll find a sign-up link for my weekly(ish) newsletter in the black box below the sharing buttons and in the sidebar.

The post Monday Meditation — RCL Year B, 3rd Sunday of Easter, Luke 24:36b–48 appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

Monday Meditation — RCL Year B, 3rd Sunday of Easter Luke 24:36b–48

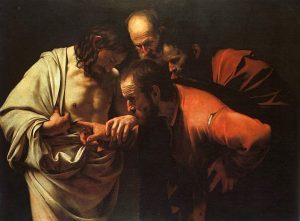

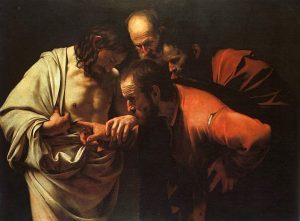

Caravaggio: The Incredulity of Thomas (public domain)

Caravaggio: The Incredulity of Thomas (public domain)The similarities between the four evangelists when recounting the the resurrection encounters can make it hard to keep the stories straight. Next Sunday’s passage of Luke (Luke 24:36b–48) bears echoes of the pair of encounters in John, first without Thomas and then with him.

Luke 24:36b–48

Once I get my bearings, I note four things, all important to my living of the faith.

First is the ending: much like in Matthew 28 and Acts 1, the risen Christ commissions his followers as witnesses. I take this as good news, since a “witness” is never called upon to do anything but tell honestly what he or she has seen and known. That’s much more manageable than being in charge of Christ’s own work and mission.

Second, to my enormous comfort, the disciples don’t actually get it. They were startled, terrified, had doubts, disbelieved, and mistook their beloved Jesus for a ghost. Oh yes, they also felt a bit of joy in verse 41. I go through most of life a bit baffled as to what God is up to, so I’m glad to know this has important precedent — even apostolic authority.

Third, Jesus went well out of his way to comfort and reassure them. He started with the message familiar from so many startling angelic visitations: “Peace be with you!” When that wasn’t quite sufficient, Jesus let them see his wounds and touch him. And when they still weren’t convinced, Jesus had them give him a snack, all so they would know he was real.

The fourth thing, I am convinced, is the most significant: Jesus did a miracle. It is easy to miss it, but it is a very big deal. It is in verse 45:

Then he opened their minds to understand the scriptures.

It is easier to notice that he spent some time teaching them, showing how the Old Testament pointed out that the Messiah was to the suffer and then rise from death—which is to be their message as witnesses.

The miracle was that he enabled them to understand this teaching.

This is the last, resurrection appearance in Luke. The miracle answers the big problem building up through those appearances.

At the tomb, the myrrh-bearing women did not see Jesus himself. The angels benevolently roll their eyes when the women don’t remember that Jesus said he must die and rise.

The male disciples didn’t get it either, deciding the women were speaking nonsense.

Then on the road to Emmaus, two disciples were bummed out about Jesus’ death and baffled by the women’s testimony. Jesus himself is there, but they don’t recognize him, even as he teaches them of the biblical testimony to his life and work.

Lest we look down on them, though, Luke tells us that they were “kept from recognizing” Jesus (v. 14). It was only when “their eyes were opened” (v. 31) that they knew who he was.

So it seems to me that in 34-48 Luke shows Jesus doing what was needed for the whole band of followers to understand the very gospel itself — Jesus really is the anointed one who (very biblically) suffered and rose for our salvation.

This is the essential miracle of faith.

I wonder…

I wonder if I need this miracle again today?

I wonder if there are places where my mind is closed, my heart hardened, my eyes kept from recognizing Jesus?

I wonder if I should pray for this same miracle for those around me who seem to struggle to believe, or who lack faith faith entirely?

++++++++++++

I’d love to send you new posts by email. You’ll find a sign-up link for my weekly(ish) newsletter in the black box below the sharing buttons and in the sidebar.

The post Monday Meditation — RCL Year B, 3rd Sunday of Easter Luke 24:36b–48 appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

April 5, 2018

Letters to a Young Pastor: The Children’s Sermon — Let the Children Come to Me

Anthony van Dyck, Suffer Little Children to Come Unto Me

Anthony van Dyck, Suffer Little Children to Come Unto MeDear ______:

You make a good observation: my letters to you on the topic of children’s sermons have not said much about what to actually say to the kids.

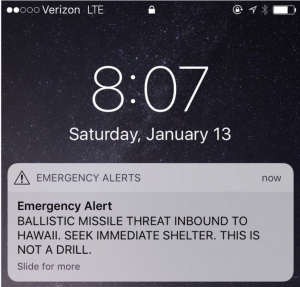

True enough. I’ve talked about taking Mr. Rogers as your role model, about not getting the grown-ups to laugh, and about not asking the kids a bunch of quiz questions.

Yes, what you actually DO say matters as much as avoiding the pitfalls. Yes, I will indeed send you some input on how to pick a topic, how to prepare, and how to make sure you are on target for kids.

But really, the fails in this department are so frequent and so epic that somehow I hope that getting a sense of the potential problems can be helpful. Think of it as warning signs for detours, accidents, and delays popping up on your GPS. You really do need to know which roads NOT to go down.

I still sense your hesitation about the whole enterprise, though. In your heart of hearts it just might be possible that you don’t think children’s sermons are a useful or appropriate idea at all.

If that is how you feel, you have a lot of good company out there. But I’m going to do my best to convince you to at least be open. And my argument will underscore the point that figuring out what to actually say in a children’s sermon is not the most important place to start.

Let’s start instead with God’s own approach to ministry.

Step One: Incarnation. Step Two: Presentation.

When God wanted to reach out and help humanity, he didn’t start with a set of talking points. God came in person.

The incarnation itself is the beginning of the gospel ministry. God showed up, and that was the message.

In our ministry we would do well to do as Jesus did. We show up. If Christ is truly in us, then being truly present is the beginning – and it embodies the message.

Then, when God was personally present in Christ, loving people actively, serving people practically, he taught them. They listened because, as the founder of Young Life used to put it, he had “earned the right to be heard.”

Jesus’ Policy: Let the Children Come to Me

Now if you want a biblical text to ponder as a justification for the children’s sermon, try Mark 10:13-15.

And they were bringing children to him that he might touch them, and the disciples rebuked them. But when Jesus saw it, he was indignant and said to them, “Let the children come to me; do not hinder them, for to such belongs the kingdom of God. Truly, I say to you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God like a child shall not enter it.” (ESV)

You’ll find parallel passages in Matthew 19:13-15 and Luke 18:15-17.

Note carefully what all three Gospel texts have in common:

First, Jesus insists that his disciples allow him to spend ministry time with little kids. Note how the first instinct of many adult disciples then and now is to shuffle the children off, out of the action.

Sometimes we think worship, or the sermon, or whatever, is going to be over their heads so we keep them away — but Jesus made sure some of his ministry was age-appropriate for them.

Sometimes we think they will be disruptive, believing worship is supposed to be peaceful and reverent — but Jesus was okay with having them near.

Second, though, Jesus showed a very Mr. Rogers sensibility. Jesus did not insist that the kids come. Jesus allowed them to come. If you let them choose the distance, you are being more like Jesus — and avoiding rarer, but more serious pitfalls.

The Danger

I once saw a visiting pastor doing a children’s sermon, and he wanted to do much as Jesus had done. He wanted to put his hand on each kid’s head and give a blessing.

Here’s the deal: instead of allowing the children to come if they wanted a blessing, he tried to go to them and touch them.

Some of the kids were fine with that.

But some of the kids didn’t want to be touched. They ducked. They backed away. One backed away, and then cut behind other kids to be out of reach.

The visiting pastor grabbed him, saying

You can run but you can’t hide. It’s a God thing.

The takeaway from that children’s sermon? In church, somehow because of God, grown-ups can touch kids whenever they want to.

Do you really know what is going on in kids’ lives? Do you know who has already been a victim of abuse? Do you know who has challenges with touch because of anxiety or autism? Even if you do know these things, follow Jesus’ advice. Give children the choice about whether they come to you or not.

As a pastor you are one of the grown-ups. And grown-ups need to protect kids from unwanted touch.

Seems simple: In ministry whether with kids or with grown ups, don’t touch anybody that doesn’t want to be touched.

Here’s your rule of thumb: Make the aim of your children’s sermon to communicate about Jesus in word and in action. Start by letting the kids decide how close to come.

Themes, contents, and planning soon!

Blessings,

Gary

————

I’d love to send you all the new posts in this series by email. You can sign up using the black box and orange button just below the sharing buttons.

To read the series from the beginning, click here.

The post Letters to a Young Pastor: The Children’s Sermon — Let the Children Come to Me appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

March 29, 2018

Letters to a Young Pastor: The Children’s Sermon — This Is Not A Test

CC by wecometolearn 2.0

CC by wecometolearn 2.0Dear ____:

Yes, you are right: it is hard not to aim for a laugh during the children’s sermon — or to enjoy it big time when it happens. As you note, it may be the inevitable result of asking children questions up front. You don’t know what they’ll say.

Though it is rarely publicly recommended as the goal for the children’s sermon, I’m convinced that many preachers make laughter their primary aim.

You’ll remember that I suggested you make your role model Mr. Rogers — who gently welcomed children and made them feel important.

Those who go for adult laughter also have their media role models: in the “Kids Say the Darndest Things” radio and television shows of past generations, Art Linkletter and Bill Cosby both had shows where they asked questions to get kids to make goofy responses.

Since the grown-ups were laughing at home and not in the kids’ faces, maybe it was okay. At least it wasn’t done in the name of teaching children what faith in Jesus is about.

What About Other Kinds of Questions?

So what about asking more sincere questions?

I think you need to be very discerning about asking questions in a children’s sermon.

There are good reasons to want to ask questions. Not least of these is that you, the pastor, want it to be a time of reciprocal engagement. It probably feels awkward, at least at first, if you DON’T make it a conversation.

But there are so many ways questioning kids in front of a crowd can go terribly wrong. Or even mildly wrong. But anyway, wrong.

As Shakespeare said, “Let me count the ways…”

As I’ve now said too many times, you might get the adults laughing, with the kids feeling like church is where they get laughed at.

You may accidentally make your question too complicated, leading to baffled looks. (And speaking in understandable ways is a skill that has to be nurtured.)

You may ask something so patently obvious that even the kids feel dumb answering it. (That’s the public version of a familiar bad Bible study guide: “What did Jesus do in verse 12?”)

More likely you may get one or more of the kids slightly missing the point of the question and going off on a tangent. Then you are out of control and have to reel them in or throw in the towel — usually leading to grown-ups laughing (see #1).

Even more likely you divide the group of kids into extroverts and introverts.

The introverts are cringing inside, afraid you will make them talk in public — and they remember church as where that embarrassment happens.

The extroverts jump right in and they talk, and talk, and talk — and again you’ve lost control, leading to laughter.

This Is Not a Test

My wife, who worked for years in special education contexts, pointed out a more serious consequence of children’t sermon questions than I would have come up with:

Think about what happens to the kids who really struggle in school. Five days a week they get asked questions, out loud and on paper, and they don’t know how to answer.

Then they come to church, where we want them to know that they are loved and accepted just as they are — and we quiz them about Bible and theology. In public. In front of their parents. In front of their friends.

Listen to the next half dozen children’s sermons you hear — maybe some of them are coming out of your own mouth. Listen to the kinds of questions that get asked.

Do they include metaphorical elements?

Do they ask kids to draw an ethical interpretation from a story?

Do they assume kids have a working knowledge of some basic Christian teaching?

Do they ask the kids to recall and recite something — whether something from a story you just read, or from previous knowledge?

Now imagine that you are somewhere in the 4 to 9 year old range. Imagine you are a kid who really struggles to read, to make sense of instructions, to succeed in school. All those kinds of questions are hard — for any kid, and especially for a kid who is struggling.

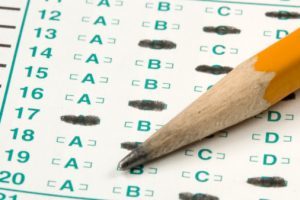

Story on NPR.org

Story on NPR.orgYou might try to put them at ease, saying “This is not a test!”

Tell that to the people of Hawaii who got the text about a supposed missile attack on January 13.

Small comfort in the follow-up saying, essentially, “Oops.”

Sometimes “Not a test” is not helpful enough.

The Need for Discernment

So what you need to do is seriously ponder the kinds of questions you are asking. Hone your skills at kid-level communication.

Make sure you don’t turn a gracious welcome in Jesus’ name into something that reinforces the sense of panic and judgment many kids endure every single day of their educational life.

Blessings,

Gary

————

This post is part of an ongoing series. Make sure you don’t miss one by subscribing to my weekly(ish) newsletter using the link just below the sharing buttons. (It’s the one where I offer you a free book.)

To read the series from the beginning, click here.

The post Letters to a Young Pastor: The Children’s Sermon — This Is Not A Test appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

March 22, 2018

Letters to a Young Pastor: The Children’s Sermon — Not a Laughing Matter

Dear ______:

Dear ______:

I’m glad to hear you got through your first “children’s sermon” all right. Whew!

(The fact that this topic is so fraught for you might be something to think about when you are looking for a field education placement. We can chat about that later if you want to.)

I am glad you took the bait and asked about my comment about laughter in children’s sermons. What I said was “Try very hard not to be funny. If the grown-ups laugh during your children’s sermon, you have very probably failed.”

So what’s wrong with laughter? In general, in much of life, nothing. Laughter seems to be a very good thing for building social relationships and for health. I’m all for it.

Humor in a Children’s Sermon?

When it comes to children’s sermons, though, I think different rules apply.

Why is that?

Well, I might come up with other, better thoughts on another day, but at a first go I’d say look at where the kids are and look at who does the laughing.

Where Are the Kids?

The kids have been called up to the front of the church. That can be frightening. It takes some kids weeks or months to be comfortable enough to go up there.

We shouldn’t be surprised. Lots of grown-ups are hesitant to do anything in front of a crowd. What happens in that space feels a lot like public performance. Public speaking? Sing a solo? Many people are frankly terrified of the idea.

Kids live their whole lives under adult scrutiny, whether from parents or teachers. Then come Sunday morning they find themselves called to the front, standing right in the middle between the pastor (adult with church authority) and their parents back in the pew (adults with family authority). It is an awkward spot.

Of course there is the potential for it to be a fantastic experience — that is if you make it a Mr. Rogers Moment. If you are gentle and welcoming, if you make them feel like they are special and they really belong in God’s house, then it is all fine.

But… what about laughter?

Who does the laughing?

So many children’s sermons prompt lots of laughter. But notice: The kids are not the ones laughing.

Where does the laughter come from? I think of three typical sources:

The pastor asks a question, and a kid makes a goofy kid-like reply — and the grown-ups laugh.

The kids get lively, talking at length or on the wrong topic, so that the pastor is out of control — and the grown-ups laugh.

The pastor says things that are actually directed at the grown-ups, not the kids — and the grown-ups laugh.

What About the Kids?

Imagine you are a kid.

Especially imagine being a sensitive kid, a shy kid, or a kid who feels inadequate.

Maybe imagine being a kid who gets bullied at school, or who gets teased — because it happens to every kid who is a bit different.

Or imagine being a kid who can barely cope because the family hides a deep dark secret of abuse.

You get called to the front and the pastor talks to you. Maybe you answer.

And then all the grown-ups burst into laughter.

I think you feel pretty rotten. You know you don’t get the joke. But you are pretty sure that the joke is about you.

So here’s the unintended takeaway of too many children’s sermons:

Church is where they laugh at me.

Not a Laughing Matter

If you have a time in the service where your job is to help kids grow in faith, then focus on that. Focus on communicating the truth about Jesus in thought, word, and deed.

That is very serious business. It is also joyful.

If you can do it in a way that gets the kids laughing happily on the topic of faith in Jesus, then fine.

But if you bring kids up to the front of the church and prompt their parents and all the other grown-ups to laugh at them then what, really, are you teaching them about Christ, and faith, and the church?

Blessings,

Gary

——

This post is part of an ongoing series on children’s sermons. To read from the beginning click here.

——

Thanks for stopping by! I’d love to send this and all my new posts straight to you via email. Sign up for my weekly(ish) newsletter using the button below the post.

The post Letters to a Young Pastor: The Children’s Sermon — Not a Laughing Matter appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

March 15, 2018

Letters to a Young Pastor: The Children’s Sermon — The Mr. Rogers Moment

Mr. Rogers (CC0 1.0)

Mr. Rogers (CC0 1.0)Dear ______:

Wow! I’ve never heard you ask for advice so urgently. I hope this reaches you in time to be helpful.

As I understand it, you’ve been asked to preach a “children’s sermon” and you are totally freaked out.

Don’t panic. Help is on the way.

The Children’s Sermon

I’ll confess: the idea of the children’s sermon used to baffle me too. In fact, before I became a pastor I told myself that if a church wanted a children’s sermon every week (or ever) I wouldn’t take the call.

When I did take a church they did want a children’s sermon. They only told me after I took the job.

Tricky.

It turns out there were several reasons behind my uppity attitude.

First, I didn’t have any kids yet, and I had no clue about how to relate to them.

Second, the great majority of children’s sermons I’d heard had been frankly awful.

Third, I really hadn’t given much thought to the incredible privilege it is to share the faith with kids.

Jesus did make a point of saying that he really, really wanted the children to come and be near him — and that the grown-up disciples were wrong to look down their noses as if kids weren’t important enough.

These days when I get to be a guest preacher I always ask if I can do the children’s sermon too!

I could actually go on about children’s sermons for a very long while, but I don’t want to overwhelm you. Since you need to be ready to roll in less than a week, and since it sounds like your blood pressure is in running dangerously high, let me start you off with one, simple, central suggestion.

It really is simple. It is at the heart of the gospel. And you would not believe how few pastors try it.

Start with the Right Role Model

Here it comes. Follow this advice and even if you botch all the rest you might just be okay:

Make Mr. Rogers your role model.

You remember when you were about four to seven years old — about the age of the kids who come up for the children’s sermon.

You turned on the TV and saw “Mr. Rogers Neighborhood.”

He came home, and put on a comfy sweater.

He sat down.

He looked out at you through the camera with a gentle smile.

Then he said he was glad you were his neighbor.

Remember how that made you feel? When you are a kid it is just wonderful to have a grown up friend. Having someone who really sees you, who actually likes you, who says you are special — and means it — makes life good.

He was a Presbyterian minister, by the way. He acted like that because it was his ministry.

Notice also what Mr. Rogers didn’t do.

He didn’t look down at you — either physically or in his attitude.

He didn’t put you on the spot with complicated questions.

He didn’t talk on and on in ways you couldn’t understand.

And he never, never laughed at you.

I don’t know if you’ve noticed but a whole lot of pastors, give children’s sermons that condescend, quiz, baffle, and make jokes about little kids.

Do you wonder why they drift away from church a couple years later?

The Mr. Rogers Moment

So what are you going to do with the kids in worship? Whatever else you do, make it a Mr. Rogers Moment.

Sit down with the kids.

Look at them with a friendly smile.

Tell them you are glad they are there.

Tell them they are special.

The children’s sermon, no matter what words you use, needs to embody the gospel. Jesus himself embodied the gospel (obviously) and when it came to time with kids, he invited them to come close and he sought to be a blessing.

Focus on those kids. Tell them they are special — because they are. Every one of them is created in the image of God.

Try very hard not to be funny. If the grown-ups laugh during your children’s sermon, you have very probably failed.

Enjoy! I’ll be praying for you.

Gary

The post Letters to a Young Pastor: The Children’s Sermon — The Mr. Rogers Moment appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

March 14, 2018

Great Compline

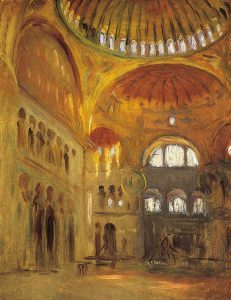

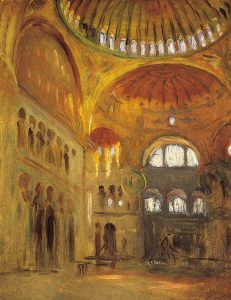

Hagia Sophia (John Sargent, public domain)

Hagia Sophia (John Sargent, public domain)One of the Lenten services I’ve experienced in the last couple of years is the Orthodox “Great Compline.”

I’ve known the Western version of Compline very well for a very long time. In the West, Compline is the last of the monastic hours, a short gentle service, maybe 20 minutes of brief prayers and Psalms, entrusting one’s self to God’s care for the night.

It is a much beloved service. I picked up a very old copy of the Monastic Diurnal that had previously belonged to a nun, and the pages of the Compline service were worn until they were smudged and virtually falling out.

It is well-loved in the Episcopal tradition as well. When I lived in Seattle, hundreds of people, many of them high school and college students, would make their way to St. Mark’s Cathedral on Sunday nights at 9:30 to listen to the beautiful singing of the men of the Compline Choir, and to pray this most-accessible form of liturgical prayer.

Great Compline

The Orthodox version is a much bigger undertaking. Nearly a dozen lengthy psalms, half a dozen very long prayers, plus the Nicene Creed and other elements familiar from Orthodox services.

At Great Compline I’m struck in particular by two of the hymns. These are not the short hymns one often encounters in Orthodox worship. These are more like litanies, biblical verses interwoven with responses.

The first is all or mostly verses from Isaiah, each of which the congregation answers

…for God is with us!

Here’s a YouTube of it. They are singing in Arabic, but the tune is what I’ve heard in the Byzantine tradition, and there are English subtitles:

The second is Psalm 150, that great call for praise using every imaginable instrument. After every verse the congregation sings the chorus,

Lord of the Powers, be with us;

for no other helper do we have in tribulations, but You.

Lord of the Powers, have mercy on us.

If you want to hear the haunting, loving, quietly beautiful melody here is a link to it on YouTube — no video, alas, but a lovely icon of the resurrection:

Both are lovely examples of a way the Orthodox encounter Scripture in worship. As well as readings, they often hear texts in music, with hymnody woven in. The hymnody is usually not repeated responses like in these two examples, but it always builds a prayerful conversational engagement with the text.

But these are both, for me, lovely Lenten meditations. When we are in the forty day long penitential slog to the Cross and the Resurrection, it helps to be reminded that “God is with us.” We don’t go through the fast or the repentance alone. We know we have turned the wrong way, again and again, but as soon as we begin to turn we find “God is with us” already.

And if the sobriety of the season has become a trial, or has reminded us of our trails and temptations, how good to be reminded that the “Lord of the powers” is our help, our only help, our always help.

The repetitious quality of the music, like in a Protestant praise chorus, gets the words deeply stuck in my head. Considering what generally gets stuck there — my obsessions about myself or about current politics — I am glad to instead have something deeply true, deeply good, and deeply beautiful going round and round in my thoughts.

As goes the music of our worship so goes our prayer life. Best to make sure we feed our prayer life solid food.

The post Great Compline appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

March 8, 2018

Forgiveness Vespers

A couple weeks ago I attended a gathering for the night before Lent began. No, this was not a Shrove Tuesday pancake supper. Nor was it a Mardi Gras carnival. This was a Sunday evening worship service.

A couple weeks ago I attended a gathering for the night before Lent began. No, this was not a Shrove Tuesday pancake supper. Nor was it a Mardi Gras carnival. This was a Sunday evening worship service.

It was an Orthodox church — and for the East Lent does not begin on a Wednesday. Orthodox Lent begins on a Monday.

Forgiveness Vespers

They call the day before Lent “Forgiveness Sunday.” The service that marks that transitional moment is called “Forgiveness Vespers.” I had heard about it for years, but I had never been able to attend.

Mostly it was a matter of scheduling, but as a Protestant I wasn’t sure if I was actually welcome. And if I showed up anyway, I didn’t know if I could participate fully. The Orthodox practice sacramental confession, and if the “forgiveness” of forgiveness Vespers was tied to confession I would be the odd man out.

This year my schedule was free. Plus the priest had told me I could participate fully. Good to go.

For the most part this was a regular Vespers service. I’ve been to many of these, so the cycle of prayers and hymns, with the smell of incense and surrounded by icons of Christ and the saints was familiar territory — beautiful, awe-inspiring, and comforting.

It wasn’t totally ordinary, though. The Orthodox spend several weeks ramping up for Lent, getting their penitential muscles in shape.

(And I do mean muscles. In this service a particular prayer that is common in the Lenten services made its first appearance. It’s called the Prayer of St. Ephrem the Syrian, and while they say it the faithful move out to the aisles and make several prostration’s. It can make worship almost aerobic.)

The Ritual of Forgiveness

The thing I actually came for, the “rite of forgiveness,” or “ceremony of mutual forgiveness,” started after the Vespers service proper. Here’s how it played out.

The priest stood at the front of the worship space, facing the congregation.

Members of the congregation formed one long line up the center aisle facing him.

As the woman at the head of the line stepped toward the priest he said,

Forgive me, a sinner,” and bowed.

Then the woman facing the priest said,

God forgives, and I forgive.” (Or words quite like that.)

Then she spoke to the priest, also saying

Forgive me, a sinner.”

And the priest answered her in the same way:

God forgives, and I forgive.”

Then she stepped her left and stood beside the priest, turning to face the same direction as him.

The second person in line approached the priest.

They each asked forgiveness.

They each granted forgiveness.

Then that second person in line moved one step to the left to stand in front of the one who had been first in line.

They each, in turn, asked forgiveness.

They each granted forgiveness.

Then this second person step to his left, turned around to stand at the end of the line that started with the priest.

This continued, for every person in the line — maybe 100 people. Only a small handful of those in attendance opted not to participate.

The line down the aisle grew shorter.

The line to the left of the priest grew longer.

Every person asked forgiveness of every other person — and granted forgiveness to each as well.

I was about in the middle of the line. I went down the row asking forgiveness and granting forgiveness to about 50 people who had gone before me.

Then from my new place at the end of the line I asked and gave forgiveness to the remaining 50 who came after.

And each exchange of forgiveness came either the kiss of peace open (the good old European way, with a kiss on each cheek — or in the air nearby), or with a gentle bow, or occasionally with full prostration.

The words were not always precisely the same, anymore than the actions that followed. As the priest graciously emphasized,

There is no wrong way to do it.”

I am sure there are Orthodox out there on the inter-webs who would say that there really is just one Right Way and many wrong ways to do this.

There might well be some, both Orthodox and Protestant, who would say that I, a Presbyterian, should not have participated.

“It is good for us to be here!”

But I think there is gospel in this parish priest’s flexibility, and the community’s openness to those were not communicants members.

I am really, really glad that I participated. As Peter said to Jesus at the Transfiguration,

Lord, it is good for us to be here!”

Perhaps you roll your eyes at the phrase “ritual of forgiveness.” Maybe you think that if it’s reduced to a ritual, it’s not really forgiveness.

But here’s the thing: what you do in ritual trains your heart, your mind, and your body for living the reality.

Asking 100 people to forgive me, one at a time, is excellent practice.

Granting forgiveness to 100 people, one at a time, is also excellent practice.

In my Protestant world I have observed that there are many in the church who are not very good at the reality of forgiveness.

Within congregations conflicts can fester.

Bitterness can brew a deadly tea.

People can worship side-by-side for years and not really be on speaking terms, much less in loving fellowship.

Congregations divide because of lack of forgiveness.

Denominations divide, and divide again because of an inability and move into reconciliation.

So this “ritual” of forgiveness is an opportunity to practice one of the most essential Christian life skills. How I wish that all the Protestants in the world would take it on as an annual practice.

Perhaps then we might begin — perhaps we might learn how — to live out forgiveness as a daily expression of our faith.

It certainly is a marvelous way to enter into the season of Lent. I love starting this holy season of repentance and renewal knowing that, at least for a moment, all is well between me and the other members of the community.

The post Forgiveness Vespers appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

February 8, 2018

Letters to a Young Pastor: “Forgive Us…As We Forgive”

CC by ElisabethMargaretha-SA 4.0

CC by ElisabethMargaretha-SA 4.0Thanks for your sympathy: I find a verified case of “Influenza A” plus pneumonia can put a serious dent in my week. Or month perhaps. So just a quick note to say thanks and continue the conversation.

Glad you looked ahead in the Lord’s Prayer to prepare yourself: the “modifiers” in the clause about forgiveness are far more bracing than those on addressing God as “Father,” asking that God’s will be done, or asking for our daily bread.

… as we forgive those who trespass against us

If you’ve ever wondered about the puzzling fact that God, all-knowing and all-powerful, asks us to pray at all, this line of the Lord’s Prayer can give you a new perspective.

It doesn’t much matter which translation of the prayer you are accustomed to: whether you say “sins,” “debts,” or “trespasses,” we step up before God and make a stunning deal:

Please, God,” we say, “don’t forgive ALL my sins. Only go as far as I have gone in forgiving others!”

On the one hand, this line of the Lord’s Prayer forces us to keep our attention on our own responsibility: we are called to do the hard work of forgiving those who do us harm.

That hard work doesn’t mean pretending we have not been harmed, denying the sins others commit. Rather it means we give up our right to condemn and punish them for their acts.

Before you point out the obvious horrible extremes, this also does not mean that by doing the hard work of forgiveness relationships with those who harm us get an easy fresh start — like a “mulligan” on the golf course.

No, forgiving others is our own hard inner work where by letting go of vengeance we ourselves can cease to suffer. It is part of our own healing.

I think C.S. Lewis described the process admirably in Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer (a book I’m not feeling quite up to go looking for right now). He tells his friend that after working daily for years to forgive someone a wrong they had done, he awoke to finally find that the forging was simply all done.

We do our part. We keep doing it. Eventually God brings healing.

We may well also need to do the hard outer work of steering clear of the one who harmed us. Or turning them over to the police if that is what is warranted.

On the other hand, though, notice how respectfully God treats you in this — as in all of prayer. You are lifted up to be a full conversation partner, a genuine player in the life created by God. Think of it as “fair trade” — like the coffee beans that pay the growers properly, but even more so.

You are not a pawn when you get to actually ask for what you need. And you are not a victim when you set rational limits on the forgiveness you ask for.

So praying the Lord’s Prayer, read through the modifiers, calls us to pray like a grown-up — indeed, to stand before God as a grown-up, taking responsibility for our lives and for growing into who we are called to be.

Blessings,

Gary

P.S. Since you still have a bit of seminary left to go, I would encourage you to see what your faculty offers on the topic of prayer. You need to take your own growth in prayer seriously as a disciple, and to be equipped as a minister. The people in your congregation will need to grow in prayer, and it is you who will be called to teach them.

If you find your school doesn’t offer much (which, I’m sorry to say, is fairly common) I’m offering a non-credit class on prayer this Lent. It is a slice of what I taught at the seminary level for years. Check it out through this link — registration is open through Ash Wednesday.

——

(This post contains an affiliate link.)

The post Letters to a Young Pastor: “Forgive Us…As We Forgive” appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.